The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Weakling

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Weakling

Author: Everett B. Cole

Illustrator: H. R. Van Dongen

Release date: April 3, 2009 [eBook #28486]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, David Wilson and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WEAKLING ***

Transcriber’s note:

This story was published in Analog Science Fact & Fiction, February 1961.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

[p 8]

THE WEAKLING

By

EVERETT B. COLE

A strong man can, of course, be dangerous,

but he doesn’t approach the vicious

deadliness of a weakling—with a weapon!

Illustrated by van Dongen

aran Makun looked

aran Makun looked

across the table at the

caravan master.

“And you couldn’t

find a trace of him?”

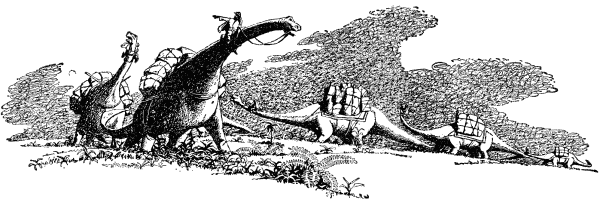

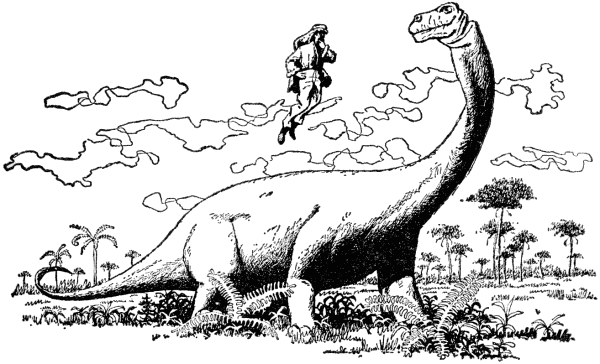

“Nothing. Not even a scrap of his

cargo or so much as the bones of a

long-neck. He just dropped out of

sight of his whole train. He went

through this big estate, you see. Then

he cut back to pick up some of his

stops on the northern swing. Well,

that was all. He didn’t get to the first

one.” The other waved a hand.

“Weird situation, too. Oh, the null

was swirling, we know that, and he

could have been caught in an arm. It

happens, but it isn’t too often that an

experienced man like your brother

gets in so deep he can’t get out somehow—or

at least leave some trace of

what happened.” The man picked up

his cup, eying it thoughtfully.

“Oh, we’ve all had close ones, sure.

We’ve all lost a long-neck or so, now

and then. Whenever the null swirls,

it can cover big territory in a big hurry

and most of that northern swing is

null area at one time or another. One

of those arms can overrun a train at

night and if a man loses his head, he’s

in big trouble.” He sipped from his cup.

“Young caravan master got caught

that way, just a while back. A friend

of mine, Dr. Zalbon, was running

the swing after the null retracted. He

found what was left.”

“Told me he ran into a herd of

carnivores. Fifteen or twenty real big

fellows. Jaws as long as a man. He

killed them off and then found they’d

been feeding on what was left of Dar

Konil’s train.”

He shook his head. “It’s not a nice

area.”

“Hold everything.” Naran leaned

forward. “You said my brother went

through this big estate. Anyone see

him come out?”

[p 11]

Dar Girdek smiled. “Oh, sure. The

Master of the Estates, Kio Barra,

himself. He saw him to the border

and watched him go on his way.”

Naran looked doubtful. “And what

kind of a character is this Barra?”

“Oh, him!” Dar Girdek waved a

hand. “Nothing there. In the first

place, he holds one of the biggest estates

in the mountain area. So what

would he want to rob a freight caravan

for?” He laughed.

“In the second place, the guy’s

practically harmless. Oh, sure, he’s

got a title. He’s Lord of the Mountain

Lake. And he wears a lot of

psionic crystalware. But he’s got about

enough punch to knock over some

varmint—if it’s not too tough. Dar

Makun might be your weak brother,

but he’d have eaten that guy for

breakfast if he’d tried to be rough.”

“Psionic weakling, you mean? But

how does he manage to be a master

Protector of an Estate?”

Dar Girdek smiled wryly. “Father

died. Brother sneaked off somewhere.

That left him. Title’s too clear for

anyone to try any funny business.”

“I see.” Naran leaned back. “Now,

what about this null?”

“Well, of course you know about

the time the pseudomen from the

Fifth managed to sneak in and lay

a mess of their destructors on Carnol?”

“I might. I was one of the guys

that saw to it they didn’t get back to

celebrate.” Naran closed his eyes for

an instant.

“Yeah. Way I heard it, you were

the guy that wrapped ’em up. Too

bad they didn’t get you on the job

sooner. Maybe we wouldn’t have this

mess on our hands now.” Dar Girdek

shrugged.

“Anyway, they vaporized the city

and a lot of area around it. That was

bad, but the aftereffect is worse.

We’ve got scholars beating their

brains cells together, but all they can

tell us is that there’s a big area up

there just as psionically dead as an

experimental chamber.” He grinned.

“I could tell ’em that much myself.

It’s a sort of cloud. Goes turbulent,

shoots out arms, then folds in again.

“We’d by-pass the whole thing,

but it’s right on the main trade route.

Only way around it is plenty of days

out of the path, clear down around

the middle sea and into the lake region.

Then you have to go all the way

back anyway, if you plan to do any

mid-continent trading. And you still

take a chance of getting caught in a

swirl arm.”

[p 12]

Naran tilted his head. “So? Suppose

you do get into a swirl? All you

need to do is wait.” He smiled.

“You know. Just sort of ignore it.

It’ll go away.”

“Uh huh. Sounds easy enough. It’s

about what we do when we have to.

But there are things living there.

They can be hard to ignore.”

“You mean the carnivores?”

“That’s right. If you meet one of

those fellow out in normal territory,

he’s no trouble at all. You hit him

with a distorter and he flops. Then

you figure out whether to reduce him

to slime or leave the carcass for his

friends and relations.” He smiled.

“From what your brother said, you

wouldn’t need the distorter.”

Naran smiled deprecatingly.

“That’s one of the things they pay me

for,” he remarked. “We run into some

pretty nasty beasties at sea.”

“Yeah. I’ve heard. Big, rough fellows.

Our varmints are smaller. But

what would you do if you ran into

twenty tons or so of pure murder,

and you with no more psionic power

than some pseudoman?”

Naran looked at him thoughtfully.

“I hadn’t thought of that,” he admitted.

“I might not like it. Jaws as longs

as a man, you said?”

The other nodded. “Longer, sometimes.

And teeth as long as your hand.

One snap and there’s nothing left.

“When they kill a long-neck, they

have a good meal and walk away

from whatever’s left. But people are

something else. They just can’t get

enough and they don’t leave any

crumbs.” He waved a hand.

“There’ve been several trains

caught by those things. A swirl arm

comes over at night, you see, and the

caravan master loses his head. He

can’t think of anything but getting

out. Oh, he can yell at his drivers.

They’ve got a language, and we all

know it. That’s easy. But did you ever

try to get a long-neck going without

psionic control?”

“I see what you mean. It could be a

little rough.”

“Yeah. It could be. Anyway, about

this time, everybody’s yelling at everybody

else. The long-necks are

squealing and bellowing. Drivers are

jerking on reins. And a herd of carnivores

hears the commotion. So,

they drop around to see the fun. See

what I mean?”

Naran nodded and Dar Girdek

went on.

“Well, that’s about it. Once in a

great while, some guy manages to get

into a cave and hide out till the null

swings away and another caravan

comes along. But usually, no one sees

anything but a little of the cargo and

some remains of long-necks. No one’s

ever come up with any part of man or

pseudoman. As I said, one snap and

there’s nothing left.”

Naran smiled wryly. “Tough to be

popular, I guess.” He leaned forward.

“But you’ve been over the trail

several times since he disappeared.

And you said you’ve seen nothing. No

trace of the train. That right?”

The other shook his head. “Not

even a cargo sling.”

“You’re making up a train now,

aren’t you? I’d like to go along on this

[p 13]

next trip. Fact is, I’ve been thinking

some nasty thoughts. And I’m going

to be uneasy till I find out whether

I’m right or not.”

Dar Girdek rubbed his chin. “Want

to buy in, maybe?”

“No, I don’t think so. I’ll work my

way—as your lead driver.”

“Oh, no!” Dar Girdek laughed.

“You don’t put a psionic on some

long-neck. Lead driver’s pseudoman,

just like the rest.” He sobered.

“Oh, sure. You could handle the

drivers, but it just isn’t done.”

Naran smiled. “Oh, as far as the

other drivers’ll know, I’m just another

pseudoman. I’ve been a ship’s non-psi

agent, remember? We earn our

keep by dealing with the people in

non-psi areas.”

“It won’t work.” The caravan master

shook his head. “These drivers can

get pretty rough with each other.

You’d have to set two or three of

them back on their heels the first day.

It would be either that, or get a lot of

bruises and end up as camp flunky.”

“Could be,” Naran told him. “Tell

you what. You turn me loose in an

experimental chamber so I can’t

fudge. Then send your toughest driver

in and tell him to kick me out of there.

I’ll show him some tricks I learned

from the non-psi’s overseas and he’ll

be a smarter man when he wakes

up.”

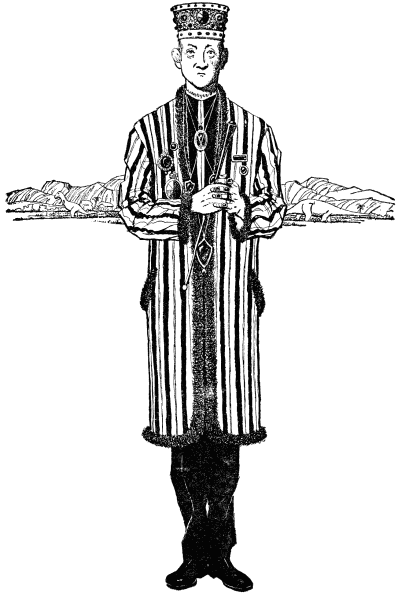

Leuwan, Kio Barra, Lord of the

Mountain Lake, Master of the Estates

Kira Barra, and Protector of the

Common Good, stood examining the

assortment of crystals in a cabinet.

He hesitated over a large, brilliantly

gleaming sphere of crystallized carbon,

then shook his head. That one

would be pretty heavy going, he was

sure. The high intensity summary

said something about problems of the

modern world, so it could be expected

to be another of those dull reports on

the welfare of the Commonwealth.

Why, he wondered, did some projection

maker waste good time and

effort by making up things like that?

And why did they waste more time

and effort by sending them around?

When a man wanted to relax, he

wanted something to relax with.

What he was looking for was something

light.

He turned his attention to other

crystals, at last selecting a small, blue

prism. He held it up, regarding it,

then nodded and placed it on the

slender black pedestal near his chair,

where he could observe without undue

effort.

He turned, examining each corner

of his empty study, then took his sapphire-tipped

golden staff from under

his arm, placing it carefully on a rack

built into his chair arm, where it

would be convenient to his hand

should the need arise.

One could never be too careful, he

thought. Of course, he could deal with

any recalcitrant slave by other means,

but the distorter was convenient and

could be depended upon to give any

degree of pressure desired. And it

was a lot less trouble to use than to

concentrate on more fatiguing efforts

such as neural pressure or selective

paralysis.

[p 14]

One must conserve one’s powers

for times when they might be really

needed.

Too, there was the remote possibility

that some lackland wanderer

might come by and find a flaw in the

protection of the Estates—even somehow

penetrate to the Residence. Barra

shuddered at that thought, then

shrugged it off. Kira Barra was well

protected, of that he had made sure.

Ever vigilant surrogates were deposited

in all the strategic spots of the

Estates—not only to allow quick observations

of the condition of the

lands, but also to give automatic

warning of the approach of anyone of

inimical turn of mind.

He eased his bulk into the chair,

twisted about for a few moments as it

adjusted to fit his body, then leaned

back with a sigh of relaxation and directed

his thoughts to the crystal before

him.

Under the impulses of his amplified

thought, the crystal glowed, appeared

to expand, then became a

three-dimensional vista.

The high intensity summary and

excerpt leader had been not too deceptive,

Barra told himself as the

story unfolded. It was a well done adventure

projection, based on the war

with the Fifth planet. Critically, he

watched the actions of a scout crew,

approving of the author’s treatment

and selection of material. He, Barra,

was something of a connoisseur of

these adventure crystals, even though

he had never found it necessary to

leave the protection of Earth’s surface.

He shrugged, taking his attention

from the projection.

The lacklanders, he told himself—entertainment

people, caravan masters,

seafarers, other wanderers of

light responsibility—were the natural

ones to be selected to go out and

deal with remote emergencies.

Like all stable, responsible men of

property and worth, he was far too

valuable to the Commonwealth to

risk himself in wild dashes to the

dead, non-psionic lands, or out into

the emptiness of space. As far as risking

himself on combat missions of

interplanetary war— He shook his

head. This was pure stupidity.

He frowned uneasily. It had been a

bit unfair, though, of the Controllers.

They had completely excused him

from service on the basis of inaptitude.

It had rankled ever since.

Of course he couldn’t be expected

to dash madly about in some two-man

scout. Even as his brother’s assistant,

he had been a person of quite

definite standing and responsibility

and such antics would have been beneath

his dignity. He had made that

quite plain to them.

There had been responsible posts

where a man of his quality and standing

could have been of positive value.

And, as he had pointed out, they

could have assigned him to one of

those.

But no! They had merely excused

him. Inapt!

As far as that went, he told himself

angrily, he, Kio Barra, could comport

himself with the best if necessity

demanded.

[p 15]

Those dashing characters in this

projection were, of course, the figments

of some unstable dreamer’s

imagination. But they showed the instability

of the usual lackland wanderers.

And what could such men do

that a solid, responsible man like

himself couldn’t do better?

He returned to the crystal, then

shook his head in disgust. It had become

full—flat—meaningless. Besides,

he had matters of real import

to take care.

He directed his attention to the

chair, which obediently swung about

until he faced his large view crystal.

“Might as well have a look at the

East Shore,” he told himself.

As he focused his attention, the

crystal expanded, then became a huge

window through which he could see

the shores of the inland sea, then the

lands to the east of the large island on

which he had caused his Residence to

be built. He looked approvingly at

the rolling, tree-clad hills as the view

progressed.

Suddenly, he frowned in annoyance.

The great northern null was in

turbulence again, thrusting its shapeless

arms down toward the borders of

Kira Barra. He growled softly.

There, he told himself, was the result

of the carelessness of those lackland

fools who had been entrusted

with the defense of the home planet.

Their loose, poorly planned defenses

had allowed the pseudomen of the

Fifth to dash in and drop their destructors

in a good many spots on the

surface. And here was one of them.

Here was a huge area which had

once been the site of a great city and

which had contained the prosperous

and productive estates of a Master

Protector, now reduced to a mere

wasteland into which slaves might

escape, to lead a brute-like existence

in idleness.

He had lost pseudomen slaves in

this very null and he knew he would

probably lose more. Despite the vigilance

of the surrogates, they kept

slipping across the river and disappearing

into that swirling nothingness.

And now, with that prominence

so close—

He had no guards he could trust to

go after the fellows, either. Such

herd guards as he had would decide

to desert their protector and take up

the idle life which their fellow pseudomen

had adopted. A few of them

had gone out and done just that.

Their memories of the protection

and privileges granted them were

short and undependable. He sighed.

“Ungrateful beasts!”

Some Master Protectors had little

trouble along that line. Others had

managed to hire the services of halfmen—weak

psionics, too weak to

govern and yet strong and able

enough to be more than mere pseudomen.

These halfmen made superb, loyal

guards and overseers—for some—but

none had remained at Kira Barra.

They had come, to be sure, but they

had stayed on for a time, then drifted

away.

And, he thought angrily, it was illegal

to restrain these halfmen in any

[p 16]

way. Some soft-headed fool had

granted their kind the rights of Commonwealth

citizenship. Halfmen had

even managed to take service with

the fleet during the war with the

Fifth Planet. Some of them had even

managed somehow to be of small value—and

now many of them held the

status of veterans of that victorious

war—a status he, one of the great

landholders, was denied.

No, he told himself, until such

time as the nulls were solved and

eliminated, such pseudomen as managed

to cross the northeastern river

were safe enough in their unknown

land. And, he thought sourly, the

scholars had made no progress in

their studies of the nulls.

Probably they were concerning

themselves with studies more likely

to give them preferment or more immediate

personal gain.

Of course, the wasteland wasn’t entirely

unknown, not to him, at least.

He had viewed the area personally.

There were hilltops on the Estates

from which ordinary eyesight would

penetrate far into the dead area, even

though the more powerful and accurate

parasight was stopped at its borders.

Yes, he had seen the affected

area.

He had noted that much of it had

regained a measure of fertility. There

was life now—some of it his own

meat lizards who had wandered across

the river and out of his control. And

he had even seen some of the escaped

pseudomen slinking through the

scrub growth and making their crudely

primitive camps.

“Savages!” he told himself. “Mere

animals. And one can’t do a thing

about them, so long as they let that

dead area persist.”

Eventually, the scholars had reported,

the dead areas would diminish

and fade from existence. He smiled

bitterly. Here was a nice evasion—a

neat excuse for avoiding study and

possible, dangerous research.

So long as those nulls remained,

they would be sources of constant loss

of the responsible Master Protectors,

and would thus threaten the very

foundations of the Commonwealth.

Possibly, he should— He shook

his head.

No, he thought, this was impractical.

Parasight was worthless beyond

the borders of the null. No surrogate

could penetrate it and no weapon

would operate within it. It would be

most unsafe for any true man to enter.

There, one would be subject to

gross, physical attack and unable to

make proper defense against it.

Certainly, the northern null was no

place for him to go. Only the pseudomen

could possibly tolerate the conditions

to be found there, and thus,

there they had found haven and were

temporarily supreme.

Besides, this matter was the responsibility

of the Council of Controllers

and the scholars they paid so

highly.

He concentrated on the crystal,

shifting the view to scan toward the

nearest village.

Suddenly, he sat forward in his

chair. A herd of saurians was slowly

[p 17]

drifting toward one of the arms the

null had thrust out. Shortly, they

would have ambled into a stream and

beyond, out of all possible control.

Perhaps they might wander for years

in the wastelands. Perhaps they and

their increase might furnish meat for

the pseudomen who lurked inside

the swirling blankness.

He snarled to himself. No herders

were in sight. No guard was in attendance.

He would have to attend

to this matter himself. He concentrated

his attention on the power crystals of

a distant surrogate, willing his entire

ego into the controls.

At last, the herd leader’s head came

up. Then the long-neck curved, snaking

around until the huge beast stared

directly at the heap of rocks which

housed the crystals of the surrogate

himself. The slow drift of the herd

slowed even more, then stopped as

the other brutes dimly recognized

that something had changed. More of

the ridiculously tiny heads swiveled

toward the surrogate.

Kio Barra squirmed in his chair.

Holding these empty minds was a

chore he had always hated.

Certainly, there was less total effort

than that required for the control

of the more highly organized pseudomen,

but the more complex minds

reacted with some speed and the effort

was soon over. There was a short,

sometimes sharp struggle, then surrender.

But this was long-term, dragging

toil—a steady pushing at a soggy, unresisting,

yet heavy mass. And full

concentration was imperative if

anything was to be accomplished. The

reptilian minds were as unstable as

they were empty and would slip away

unless firmly held. He stared motionlessly

at his crystal, willing the huge

reptiles to turn—to waddle back to

the safe grasslands of the estate, far

from the null.

At last, the herd was again in motion.

One by one, the huge brutes

swung about and galloped clumsily

toward more usual pastures, their

long necks swaying loosely with their

motion.

Switching from surrogate to surrogate,

Barra followed them, urged

them, forced them along until they

plunged into the wide swamp northeast

of Tibara village.

He signed wearily and shifted his

viewpoint to a surrogate which overlooked

the village itself. What, he

wondered, had happened to the

herdsmen—and to the guards who

should be overseeing the day’s work?

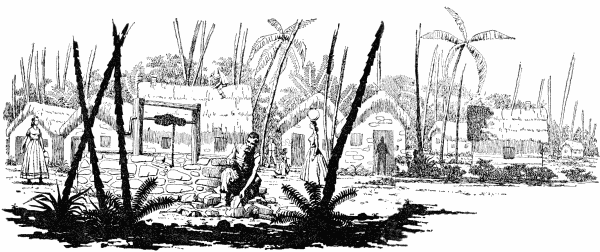

Half hidden among ferns and the

mastlike stems of trees, the rude huts

of Tibara nestled in the forest, blending

with their surroundings, until

only the knowing observer could

identify them by vague form. Barra

shifted his viewpoint to the central

village surrogate.

There were other open spaces in

the village, but this was the largest.

Here was the village well, near which

a few children played some incomprehensible

game. An old man had

collected a pile of rock and had started

work on the well curb. Now, he

sat near his work, leaning against the

[p 18]

partly torn down wall. Spots of sunlight,

coming through the fronds high

above, struck his body, leaving his

face in shadow. He dozed in the

warmth, occasionally allowing his

eyes to half open as he idly regarded

the scene before him.

Before some of the huts surrounding

the rude plaza, women squatted

on the ground, their arms swinging

monotonously up and down as they

struck their wooden pestles into

bowls of grain which they were

grinding to make the coarse meal

which was their mainstay of diet.

A few men could be seen, scratching

at small garden plots or idly repairing

tools. Others squatted near

their huts, their attention occupied by

fishing gear. Still others merely leaned

against convenient trees, looking at

each other, their mouths moving in

the grotesque way of the pseudoman

when he could find an excuse to idle

away time.

Barra listened to the meaningless

chatter of grunts and hisses, then disregarded

the sounds. They formed, he

had been told, a sort of elementary

code of communication. He coughed

disparagingly. Only some subhuman

could bring himself to study such

things.

Of course, he knew that some lacklanders

could make vocal converse

with the pseudomen and caravan

masters seemed to do it as a regular

thing, but he could see no point in

such effort. He could make his demands

known without lowering himself

by making idiotic noises.

His communicator crystals would

drive simple thoughts into even the

thick skulls of his slaves. And he

could—and did—thus get obedience

and performance from those slaves

by using normal, sensible means as

befitted one of the race of true men.

And what would one want of the

pseudomen other than obedience?

Would one perhaps wish to discuss

matters of abstract interest with these

beast men? He regarded the scene

with growing irritation.

Now, he remembered. It was one

of those days of rest which some

idiot in the Council had once sponsored.

And a group of soft-headed

fools had concurred, so that one now

had to tolerate periodic days of idleness.

Times had changed, he thought.

There had been a time when slaves

were slaves and a man could expect

to get work from them in return for

his protection and support.

But even with these new, soft laws,

herds must be guarded—especially

with that null expanding as it was.

Even some lackland idiot should be

able to understand that much.

He turned his attention to the

headman’s hut.

The man was there. Surrounded by

a few villagers, he squatted before his

flimsy, frond-roofed hut, his mouth in

grotesque motion. Now, he stopped

his noisemaking and poised his head.

Then he nodded, looking about the

village.

Obviously, he was taking his ease

and allowing his people to do as they

would, without supervision.

Barra started to concentrate on the

[p 19]

surrogate, to make his wishes and his

displeasure known. Then he turned

impatiently from the crystal, seizing

his staff. Efficient as the surrogates

were, there were some things better

attended to in person.

He got to his feet and strode angrily

out of the study, sending a peremptory

summons before him. As he

entered the wide hallway, an elderly

slave came toward him. Barra looked

at the man imperiously.

“My cloak,” he demanded, “and the

cap of power.”

He projected the image of his fiber

cloak and of the heavy gold headpiece

with its precisely positioned

crystals, being careful to note the red,

green and blue glow of the various

jewels. Meticulously, he filled in details

of the gracefully formed filigree

which formed mounts to support the

glowing spheres. And he indicated

the padded headpiece with its incrustation

of crystal carbon, so his

servitor could make no mistake. The

man was more sensitive than one of

the village slaves, but even so, he was

merely a pseudoman and had to have

things carefully delineated for him.

As the man walked toward a closet,

Barra looked after him unhappily.

The heavy power and control circlet

was unnecessary in the Residence,

for amplifiers installed in the building

took care of all requirements. But

outside, in the village and fields, a

portable source of power and control

was indispensable and this heavy

gold cap was the best device he had

been able to find.

Even so, he hated to wear the circlet.

The massive crystals mounted

on their supporting points weighed a

couple of pounds by themselves and

though the gold insulating supports

were designed as finely as possible,

the metal was still massive and heavy.

It was a definite strain on his neck

muscles to wear the thing and he always

got a headache from it.

For an instant, envy of the powerful

psionics crossed his mind. There

were, he knew, those who required no

control or power devices, being able

to govern and direct psionic forces

without aid. But his powers, though

effective as any, required amplification

and when he went out of the

Residence it was essential that he

have the cap with him.

Proper and forceful handling of

the things of the Estates, both animate

and inanimate, demanded considerable

psionic power and this

made the large red power crystal at

the center of his cap most necessary.

Besides, simultaneous control

problems could be difficult—sometimes

even almost impossible—without

the co-ordinating crystals which

were inset at the periphery of the

headband.

And there was the possibility that

he might meet some trespassing lacklander

who might have to be impressed

with the resources of the master

of Kira Barra. He knew of more

than one instance wherein a Master

Protector had been overcome by some

predatory lackland wanderer, who had

then managed by one means or another

to secure his own accession to

[p 20]

the estates of his victim. He smiled

grimly.

Carelessness could be costly. He

had proved that to his brother.

Kio Barra still remembered the

first time he had quarreled violently

with Boemar. He still remembered

the gentle, sympathetic smile and the

sudden, twisting agony that had shot

through him as his power crystal

overloaded. The flare of energy had

left him incapable of so much as receiving

a strongly driven thought for

many days.

He laughed. But, poor, soft fool

that he had been, Boemar had carefully

nursed his brother’s mind back

to strength again.

Yes, Boemar had been a powerful

man, but a very unwise one. And he

had forgotten the one great strength

of his weaker brother—a strength

that had grown as Leuwan aged. And

so, it was Leuwan who was Kio Barra.

But such a thing would never

again happen at Kira Barra. With his

controls and amplifiers, he was more

than a match for the most powerful of

the great psionics—so long as they

didn’t meet him with affectionate

sympathy.

He stood silently as the servitor

put the cap on his head and placed

the cloak about his shoulders. Then,

tucking his heavy duty distorter under

his arm, he turned toward the

outer door. The control jewels on his

cap burned with inner fire as he

raised himself a few inches from the

floor and floated out toward the dock.

Not far from the forest shaded village

of Tibara, logs had been lashed

together to form a pier which jutted

from the shore and provided a mooring

for the hollowed logs used by

men of the village in harvesting the

fish of the lake. Several boats nested

here, their bows pointing toward the

fender logs of the pier. More were

[p 21]

drawn up on the gravel of the shore,

where they lay, bottoms upward, that

they might dry and be cleaned.

A few villagers squatted by their

boats and near the pier. Others were

by the nets which had been spread

over the gravel to dry.

One large section of the pier was

vacant. Always, this area was reserved

for the use of the Lord of the

Mountain Lake.

As Barra’s boat sped through the

water, he concentrated his attention

on the logs of the pier, urging his

boat to increasing speed. The sharp

prow rose high in the water, a long

vee of foam extending from it, to

spread out far behind the racing

boat.

As the bow loomed almost over the

floating logs, Barra abruptly transferred

his focus of attention to his

right rear, pulling with all the power

of the boat’s drive crystals. The craft

swung violently, throwing a solid

sheet of water over pier and shore,

drenching the logs and the men

about them.

Then the bow settled and the boat

lay dead in the water, less than an

inch from the pier’s fender logs.

Barra studied the space between

boat and logs for an instant, then

nodded in satisfaction. It was an adequate

landing by anyone’s standards.

His tension somewhat relieved, he

raised himself from the boat and hovered

over the dock.

Sternly, he looked at the villagers

who were now on their feet, brushing

water from their heads and faces.

They ceased their movements, eying

him apprehensively and he motioned

imperiously toward the boat.

“Secure it!”

The jewels of his control cap

glowed briefly, amplifying and radiating

the thought.

The villagers winced, then two of

them moved to obey the command.

Barra turned his attention away and

arrowed toward the screen of trees

which partially concealed the village

proper.

As he dropped to the ground in the

clearing before the headman’s hut,

men and women looked at him, then

edged toward their homes. He ignored

them, centering his attention

on the headman himself.

The man had gotten to his feet and

was anxiously studying his master’s

face.

For a few seconds, Barra examined

the man. He was old. He had been

headman of the village under the old

Master Protector, his father—and his

brother had seen no reason for

change, allowing the aging headman

to remain in charge of the welfare of

his people.

But this was in the long ago. Both

of the older Kio Barra had been soft,

slack men, seeking no more than

average results. He, Leuwan, was different—more

exacting—more demanding

of positive returns from the

Estates.

Oh, to be sure, Kira Barra had

somehow prospered under the soft

hands of his predecessors, despite

their coddling of the subhuman pseudomen,

but there had been many laxities

which had infuriated Leuwan,

[p 22]

even when he was a mere youth. He

frowned thoughtfully.

Of course, if those two hadn’t been

so soft and tolerant, he would have

been something other than Lord of

the Mountain Lake. He would have

had to find other activities elsewhere.

He dropped the line of thought.

This was not taking care of the

situation.

He put his full attention on the

man before him, driving a demand

with full power of cap amplifier.

“Why are all your people idling

away their time? Where are your

herdsmen and guards?”

The headman’s face tensed with effort.

He waved a hand southward and

made meaningless noises. Faintly, the

thought came through to Barra.

“In south forest, with herd. Not

idle, is rest day. Few work.”

Barra looked angrily at the man.

Did this fool actually think he could

evade and lie his way out of the trouble

his obvious failure to supervise

had brought? He jabbed a thumb

northward.

“What about that herd drifting toward

the north river?” The two

green communicator crystals gleamed

with cold fire.

The headman looked confused.

“Not north,” came the blurred

thought. “No herd north. All south

forest, near swamp. One-hand boys

watch. Some guard. Is rest day.”

Unbelievingly Barra stared at the

pseudoman. He was actually persisting

in his effort to lie away his failure.

Or was he attempting some sort

of defiance? Had his father and brother

tolerated such things as this, or

was this something new, stemming

from the man’s age? Or, perhaps, he

was trying the temper of the Master

Protector, to see how far he could go

in encroaching on authority.

He would deal with this—and

now!

Abruptly, he turned away, to direct

his attention to the central surrogate.

It was equipped with a projector

crystal.

The air in the clearing glowed and

a scene formed in the open space.

Unmistakably, it was the northern

part of Kira Barra. The lake was

shown, and sufficient landmarks to

make the location obvious, even to a

pseudoman. Carefully, Barra prevented

any trace of the blank, swirling

null from intruding on the scene.

Perhaps the subhuman creature before

him knew something of its properties,

but there was no point in making

these things too obvious.

He focused the scene on the stream

and brought the approaching herd

into the picture, then he flashed in

his own face, watching. And he

brought the view down closely

enough to indicate that no human

creature was near the herd. Finally, he

turned his attention to the headman

again.

“There was the herd. Where were

your people?”

The old man shook his head incredulously,

then turned toward one

of the few men who still remained in

the clearing.

He made a series of noises and the

[p 23]

other nodded. There were more of the

growls and hisses, then the headman

waved a hand southward and the other

nodded again and turned away, to

run into the trees and disappear.

The headman faced Barra again.

“Send man,” he thought laboriously.

“Be sure herd is still south.” He

pointed toward the area where the

projection had been.

“That not herd,” he thought. “That

other herd. Never see before.”

Barra scowled furiously.

“You incapable imbecile! You dare

to call your master a liar?”

He swung about, his furious gaze

scanning the village. The pile of

stones he had noticed before caught

his attention. He focused on it.

A few stones rose into the air and

flew toward the headman.

The old man faced about, his eyes

widening in sudden fear. He dodged

one of the flying stones, then turned

to flee.

Barra flicked a second control on

him briefly and the flight was halted.

More stones flew, making thudding

sounds as they struck, then

sailing away, to gain velocity before

they curved back, to strike again.

At last, Barra turned from the litter

of rock about the formless mass on

the ground. He stared around the village,

the fury slowly ebbing within

him.

A few faces could be seen, peeping

from windows and from between

trees. He motioned.

“All villagers,” he ordered. “Here

before me. Now!” He waited

impatiently as people reluctantly came

from their huts and out of the trees,

to approach the clearing.

At last, the villagers were assembled.

Barra looked them over, identifying

each as he looked at him.

Apart from the others, one of the

younger herd guards stood close to his

woman. Barra looked at him thoughtfully.

This man, he had noted, was

obeyed by both herds and herdsmen.

He had seen him at work, as he had

seen all the villagers, and obviously,

the man was capable of quick decisions—as

quick, that was, as any pseudoman

could be. He pointed.

“This village needs a new headman,”

he thought peremptorily. “You

will take charge of it.”

The man looked toward the huddled

mass in the center of the litter of

rocks, then looked back at his woman.

A faint wave of reluctance came

to Barra, who stared sternly.

“I said you are the new headman,”

he thought imperiously. “Take

charge.” He waved a hand.

“And get this mess cleaned up. I

want a neat village from now on.”

As the man lowered his head submissively,

Barra turned away, rose

from the ground, and drifted majestically

toward the lake shore. He

could check on the progress of the

village from his view crystal back at

the Residence.

The situation had been taken care

of and there was no point in remaining

in the depressing atmosphere of

the village for too long.

Besides, there was that adventure

[p 24]

projection he hadn’t finished. Perhaps

it would be of interest now.

As the projection faded, Barra

looked around the study, then got out

of his chair and picked the crystal

from its pedestal. He stood, looking

at it approvingly for a few seconds,

then went over to the cabinet and set

it back in its case. For a time, he

looked at the rest of the assortment.

Finally, he shook his head. Some of

them, he would sell unscanned. The

others—well, they could wait.

Yes, he thought, the record crystals

had better be left alone for a while.

He hadn’t finished his inspection of

the Estates and the situation at Tibara

might not be an isolated case. It

would be well to make a really searching

inspection. He sighed.

In fact, it might be well to make

frequent searching inspections.

Shortly after his accession to the

Estates, he had seen to the defense of

Kira Barra. He smiled wryly as he

thought of the expense he had incurred

in securing all those power

and control crystals to make up his

surrogate installations. But they had

been well worth it.

He had been most thorough then,

but that had been some time ago. His

last full inspection had been almost

a year ago. Lately he had been satisfying

himself with spot inspections,

not really going over the Estates

from border to border.

Of course, the spot inspections

had been calculated to touch the potential

trouble spots and they had

been productive of results, but there

might still be hidden things he should

know about. This would have to be

looked into.

He turned and went back to his

chair, causing it to swivel around and

face the view crystal.

There was that matter of Tibara,

as far as that went. Possibly it would

be well to count that herd and identify

the animals positively.

Maybe the pasturage was getting

poor and he would have to instruct

the new headman to move to better

lands. Those strays had looked rather

thin, now that he thought of it.

Maybe some of the other long-necks

had strayed from the main herd

and he would have to have the headman

send out guards to pick them up

and bring them in.

He concentrated on the viewer,

swinging its scan over to the swamp

where he had driven that small herd.

They were still there, wallowing in

the shallow water and grazing on the

lush vegetation. He smiled. It would

be several days before their feeble

minds threw off the impression he

had forced on them that this was

their proper feeding place.

Idly, he examined the beasts, then

he leaned forward, studying them

more critically. They weren’t the

heavy, fat producers of meat normal

to the Tibara herd. Something was

wrong.

These were the same general breed

as the Tibara long-necks, to be sure,

but either their pasturage had been

unbelievably bad or they had been

recently run—long and hard. They

looked almost like draft beasts.

[p 25]

He frowned. If these were from the

Tibara herd, he’d been missing something

for quite a while.

Thoughtfully, he caused the scan to

shift. As he followed a small river, he

noted groups of the huge, greenish

gray beasts as they grazed on the tender

rock ferns. Here and there, he

noted herdsmen and chore boys either

watching or urging the great

brutes about with their noisemakers,

keeping the herd together. He examined

the scene critically, counting

and evaluating. Finally, he settled

back in his chair.

The herd was all here—even to the

chicks. And they were in good shape.

He smiled wryly.

Those brutes over in the swamp

really didn’t belong here, then. They

must have drifted into the Estates

from the null, and been on their way

back. The headman— He shrugged.

“Oh, well,” he told himself, “it was

time I got a new headman for Tibara,

anyway. And the discipline there

will be tighter from now on.”

He started to shift scan again, then

sat up. The view was pulsing.

As he watched, the scan shifted automatically,

to pick up the eastern

border of the Estates. Stretching

across the landscape was a thin line of

draft saurians, each with its driver

straddling its neck. The train had

halted and a heavily armored riding

lizard advanced toward the surrogate.

Its rider was facing the hidden crystals.

As Barra focused on him, the man

nodded.

“Master Protector?”

“That is correct.” Barra activated

his communicators. “I am Kio Barra,

Master of the Estates Kira Barra.”

The other smiled. “I am Dar Makun,

independent caravan master,” he

announced. “The null turbulence

forced me off route. Lost a few carriers

and several days of time. I’d like

to request permission to pass over

your land. And perhaps you could

favor me by selling some long-necks

to fill my train again. The brutes I’ve

got left are a little overloaded.”

Barra considered. It was not an unusual

request, of course. Certain caravans

habitually came through, to do

business with the Estates. Others were

often detoured by the northern null

and forced to come through Kira

Barra.

Of course, the masters of the caravans

were lacklanders, but they had

given little trouble in the past. And

this one seemed to be a little above

the average if anything. In his own

way, he was a man of substance, for

an owner master was quite different

from someone who merely guided

another’s train for hire.

The northern null was a menace,

Barra thought, but it did have this

one advantage. The regular caravans,

of course, passed with the courtesy of

the Estates, doing business on their

way. But these others paid and their

pasturage and passage fees added to

the income of the Estates.

In this case, the sale of a few draft

saurians could be quite profitable. He

shifted the view crystals to allow two-way

vision.

[p 26]

“To be sure.” He waved a hand.

“Direct your train due west to the

second river. Cross that, then follow

it southward. I will meet you at the

first village you come to and we can

kennel your slaves there and put your

beasts to pasture under my herdsmen.

From there, it is a short distance

to the Residence.”

“Thank you.” Dar Makun nodded

again, then turned and waved an arm.

Faintly, Barra caught the command to

proceed.

He watched for a few minutes and

examined the long train as it moved

over the rolling land and lumbered

into a forest. Then he shifted his

scan to continue his inspection of the

rest of the lands. It would be several

hours before that caravan could reach

Tibara and he could scan back and

note its progress as he wished.

He relaxed in his chair, watching

the panorama as the Estates unrolled

before him. Now and then, he halted

the steady motion of the scanner, to

examine village or herd closely. Then

he nodded in satisfaction and continued

his inspection.

The Estates, he decided, were in

overall good condition. Of course,

there were a few corrections he would

have to have made in the days to

come, but these could be taken care

of after the departure of the caravan.

There was that grain field over in

the Zadabar section, for example.

That headman would have to be

straightened out. He smiled grimly.

Maybe it would be well to create a

vacancy in that village. But that could

wait for a few days.

He directed the scan back to the

eastern section, tracing the route he

had given the caravan master. At last,

the long line of saurians came into

view and he watched their deceptively

awkward gait as the alien crawled

through a forest and came out into

deep grass.

They were making far better progress

than he had thought they would

and he would have to get ready if he

planned to be in Tibara when they

arrived.

He was more careful of his dress

than usual. This time, he decided,

he’d want quite a few protective devices.

One could never be quite sure

of these caravan masters.

Of course, so long as they could

plainly see the futility of any treacherous

move, they were good company

and easy people to deal with, but it

would be most unwise to give one of

them any opening. It just might be he

would be the one who was tired of

wandering.

He waited patiently as his slave attached

his shield brooches and placed

his control cap on his head, then he

reached into the casket the man held

for him and took out a pair of paralysis

rings, slipping one on each of his

middle fingers. At last, he dismissed

the man.

He floated out of the building and

let himself down on the cushions in

the rear of his speedboat. Critically,

he examined the condition of the

craft. His yardboys had cleaned everything

up, he noted. The canopy

was down, leaving the lines of the

boat clean and sharp.

[p 27]

He turned his attention to the

power crystal and the boat drew out

of its shelter, gained speed, and cut

through the water to the distant

shoreline.

With only part of his mind concentrated

on controlling the boat, Barra

looked across the lake. It was broad in

expanse, dotted with islands, and

rich in marine life.

Perhaps he might persuade this

Dar Makun to pick up a few loads of

dried lake fish, both for his own rations

and for sale along the way to

his destination. Some of the warehouses,

he had noted, were well

stocked and he’d have to arrange for

some shipments soon.

The boat was nearing Tibara pier.

He concentrated on setting it in

close to the dock, then made his way

to the eastern edge of the village,

summoning the headman as he passed

through the village center.

His timing had been good. The

head of the long train was nearly

across the wide grassland. For a moment,

the thought crossed his mind

that he might go out and meet the

caravan master. But he discarded it.

It would be somewhat undignified

for the master of the estate to serve

as a mere caravan guide. He stood,

waiting.

He could see Dar Makun sitting

between the armor fins of his riding

lizard. The reptile was one of the

heavily armored breed he had considered

raising over in the northwest

sector.

They were, he had been told,

normally dryland creatures. Such brutes

should thrive over in the flats, where

the long-necks did poorly. He would

have to consider the acquisition of

some breeding stock.

The caravan master drew his

mount to a halt and drifted toward

the trees. Barra examined the man

closely as he approached.

He was a tall, slender man, perfectly

at ease in his plain trail clothing.

A few control jewels glinted

from his fingers and he wore a small

shield brooch, but there was no heavy

equipment. His distorter staff, Barra

noted, was a plain rod, tipped by a

small jewel. Serviceable, to be sure,

but rather short in range. Barra’s lip

curled a trifle.

This man was not of really great

substance, he decided. He probably

had his entire wealth tied up in this

one caravan and depended on his fees

and on the sale of some few goods of

his own to meet expenses.

As Dar Makun dropped to the

ground near him, Barra nodded.

“I have instructed my headman to

attend to your drivers and beasts,” he

said. “You have personal baggage?”

The other smiled. “Thank you. I’ll

have one of the boys bring my pack

while the drivers pull up and unload.

We can make our stack here, if you

don’t mind.”

As Barra nodded in agreement, Dar

Makun turned, waving. He drew a

deep breath and shouted loudly, the

sounds resembling those which Barra

had often heard from his slaves. The

Master Protector felt a twinge of

disgust.

[p 28]

Of course, several of the caravan

masters who did regular business at

Kira Barra shouted at their slaves at

times. But somehow, he had never

become used to it. He much preferred

to do business with those few

who handled their pseudomen as

they did their draft beasts—quietly,

and with the dignity befitting the

true race.

He waited till Dar Makun had finished

with his growls and hisses. One

of the caravan drivers had swung

down and was bringing a fiber cloth

bundle toward them. Barra looked at

it in annoyance.

“This,” he asked himself, “is his

baggage?” He recovered his poise

and turned to Dar Makun.

“He can put it in the boat,” he told

the man. “I’ll have one of my people

pick it up for you when we get to the

island. Now, if you’ll follow me, the

pier is over this way.” He turned and

floated toward the dock.

As they pulled out into the lake,

Dar Makun settled himself in the

cushions.

“I never realized what a big lake

this is,” he remarked. “I’ve always

made the northern swing through this

part of the continent. Oh, I’ve seen

the lake region from the hills, of

course, but—” He looked at the water

thoughtfully.

“You have quite a lot of fresh-water

fish in there?”

Barra nodded. “We get a harvest.”

Dar Makun closed his eyes, then

opened them again. “I might deal

with you for some of those,” he

commented. “People out west seem to

like fresh-water stuff.” He looked at

Barra closely.

“I’ll have to open my cargo for

you,” he went on. “Might be a few

items you’d be interested in.”

Barra nodded. “It’s possible,” he

said. “I always need something

around the place.” He speeded the

boat a little.

The boat came to the dock and

Barra guided his guest into the Residence

and on into the study, where he

activated the view crystal.

“There’s still light enough for you

to get a look at some of the herds,” he

told Dar Makun. “I believe you said

you might need some more draft

beasts.”

Makun watched as the hills of Kira

Barra spread out in the air before

him.

“It’s a good way to locate the herds

and make a few rough notes,” he admitted.

“Of course, I’ll have to get

close to the brutes in order to really

choose, though.”

“Oh?”

“Fact. You see, these big lizards

aren’t all alike. Some of ’em are really

good. Some of ’em just don’t handle.

A few of ’em just lie down when you

drop the first sling on ’em.” Makun

nodded toward the projection.

“That big fellow over there, for instance,”

he went on. “Of course, he

might slim down and make a good

carrier. But usually, if they look like

a big pile of meat, that’s all they’re

good for. A lot of ’em can’t even

stand the weight of a man on their

necks. Breaks ’em right down.”

[p 29]

“A good carrier can handle a dozen

tons without too much trouble, but

some of these things have it tough to

handle their own weight on dry land

and you have to look ’em over pretty

closely to be sure which is which.

Can’t really judge by a projection.”

Barra looked at the man with

slightly increased respect. At least, he

knew something about his business.

He shifted the viewer to the swamp.

Of course, he thought, there were

draft animals over in the western sector.

But this small herd was convenient.

“Well,” he said, “I’ve got this little

herd over here. They got away some

time ago and lost a lot of weight before

I rounded them up again.”

Makun examined the projection

with increased interest.

“Yeah,” he remarked. “I’d like to

[p 30]

get out there in the morning and

look those fellows over. I just might

get the five I need right out there.

Might even pick up a spare or two.”

The swamp was a backwater of the

lake, accessible by a narrow channel.

Barra slowed the boat, easing it along

through the still water. Here, the

channel was clear, he knew, and it

would soon widen. But there were

some gravel bars a little farther along

that could be troublesome if one

were careless. And his attention was

divided. He glanced at his companion.

Makun leaned against the cushions,

looking at the thick foliage far overhead.

Then he turned his attention to

the banks of the channel. A long,

greenish shape was sliding out of the

water. He pointed.

“Have many of those around

here?”

“Those vermin?” Barra looked at

the amphibian. “Not too many, but I

could do with less of them.”

He picked up his distorter from

the rack beside him and pointed it

ahead of the boat. The sapphire

glowed.

There was a sudden, violent

thrashing in the foliage on the bank.

The slender creature reared into the

air, tooth-studded jaws gaping wide.

It rose above the foliage, emitting

a hissing bellow. Then it curled into a

ball and hung suspended in the air

for an instant before it dropped back

into the shrubbery with a wet plop.

Barra put the jewel-tipped rod

back in its hanger.

“I don’t like those nuisances,” he

explained. “They can kill a slave if he

gets careless. And they annoy the

stock.” He tilted his head forward.

“There’s the herd,” he went on,

“at the other end of this open water.

I’ll run up close and you can look

them over if you wish.”

Makun looked around, then

shrugged. “Not necessary. I’ll go

ahead from here. Won’t take me too

long.”

He lifted himself into the air and

darted toward one of the huge saurians.

Barra watched as he slowed

and drifted close to the brute’s head,

then hovered.

A faint impression of satisfaction

radiated from his mind as he drifted

along the length of the creature. He

went to another, then to another.

At last, he returned to the boat.

“Funny thing,” he commented. “A

couple of my own carriers seem to

have wandered clear through that

null and mixed with your herd.” He

smiled.

“Stroke of luck. Too bad the rest

didn’t manage to stay with ’em, but

you can’t have everything. I’ll pay

you trespass fees on those two, of

course, then I’d like to bargain with

you for about four more to go with

’em. Got them all picked out and I

can cut ’em out and drive them over

to the train soon’s we settle the arrangements.”

Barra frowned.

“Now, wait a minute,” he protested.

“Of course, I’ll bargain with

you for any or all of this herd. But

I’m in the breeding and raising business,

[p 31]

remember. I certainly can’t give

away a couple of perfectly good

beasts on someone’s simple say-so.

I’d like a little proof that those two

belong to your train before I just

hand them over.”

“Well, now, if it comes to that, I

could prove ownership. Legally, too.

After all, I’ve worked those critters

quite a while and any competent

psionic could—” Makun looked at

Barra thoughtfully.

“You know, I’m not just sure I like

having my word questioned this way.

I’m not sure I like this whole rig-out.

Seems to me there’s a little explaining

in order about now—and kind of

an apology, too. Then maybe we can

go ahead and talk business.”

“I don’t see any need for me to explain

anything. And I certainly don’t

intend to make a apology of any

kind. Not to you. I merely made a reasonable

request. After all, these

brutes are on my land and in my

herd. I can find no mark of identification

on them, of any kind.” Barra

shrugged.

“As a matter of fact, I don’t even

know yet which two you are trying to

claim. All I ask is indication of which

ones you say are yours and some reasonable

proof that they actually came

from your train. Certainly, a mere

claim of recognition is … well,

you’ll have to admit, it’s a little thin.”

Makun looked at him angrily.

“Now, you pay attention to me.

And pay attention good. I’m not

stupid and I’m not blind. I can see

all those jewels you’re loaded down

with and I know why you’re wearing

them. They tell me a lot about you,

you can be sure of that. Don’t think I

haven’t noticed that patronizing air

of yours, and don’t think I’ve liked it.

I haven’t and I don’t.

“I know you’re scared. I know

you’re worried to death for fear I’m

going to pull something on you. I

spotted that the first time I talked to

you.” He paused.

“Oh, I’ve been trying to ignore it

and be decent, but I’ve had about

enough. I’ve been in this caravan

business for a long time. I’ve dealt

square and I’m used to square dealing.

Now, you’ve been putting out a

lot of side thoughts about thievery

and I don’t appreciate being treated

like some sneak thief. I’m not about

to get used to the idea, either.

“Now, you’d better get the air

cleared around here and then we can

talk business. Otherwise, there’s going

to be a lot of trouble.”

Barra felt a surge of fury rising

above his fear. This lacklander clown

actually dared to try to establish

domination over a member of the

ruling class? He breathed deeply.

“I don’t have—”

“All right, listen to me, you termite.

You’ve come way too far out of

your hole. Now, you just better crawl

back in there fast, before I turn on the

lights and burn your hide off.”

The surge of mental power blazing

at Barra was almost a physical force.

He cringed away from it, his face

wrinkling in an agony of fright.

Makun looked at him contemptuously.

[p 32]

“All right. Now, I’ll tell you—”

Smoothly, Barra’s hand went to the

haft of his distorter. The jewel

seemed to rise of its own accord as it

blazed coldly.

For an infinitesimal time, Makun’s

face reflected horrified comprehension

before it melted into shapelessness.

Barra put the distorter back in its

rack, looking disgustedly at the mess

on the cushions. There was nothing

for it, he thought. He’d have to destroy

those, too. Cleaning was out of

the question. He shook his head.

Like all these strong types, this

Makun had neglected a simple principle.

With fear as his constant companion,

Barra had been forced to

learn to live with it.

Extreme mental pressure was

merely another form of fright. It

could paralyze a braver soul—and often

did. It merely made Barra miserably

uncomfortable without disturbing

his control. And the hatred that was

always in him was unimpaired—even

amplified by the pounding terror.

The more thoroughly Barra was

frightened, the more effectively he

attacked.

He leaned back in his seat, letting

the drumming of his heart subside.

Eventually, he would recover enough

to guide the boat out of the swamp

and back to the Residence.

Tomorrow? Well, he would have

to inventory the freight the man had

carried. He would have to check

those draft beasts. Perhaps he could

discern the hidden identification

Makun had mentioned.

And he would have to make disposition

of some twenty slaves. He

summoned up a smile.

Now that he thought of it, this

affair could be turned to profit. After

all, Dar Makun had been diverted

from his route and he had lost some

of his train. And caravans had been

known to disappear in the vicinity

of turbulent nulls.

All he had to do was deny knowledge

of the fate of Dar Makun’s caravan

if there were any inquiry. Oh,

certainly, he could tell any inquirer,

Dar Makun had arrived. He had

stayed overnight and then taken his

departure, saying something about

cutting around the null and back to

his normal, northern swing.

He was feeling better now. He

turned his attention to the control

crystal and the boat swung about, to

make its way back toward the lake.

It took longer than he had thought

it would. It was evening of the day

after the death of Dar Makun when

Barra turned in his seat and raised

his hand, then waved it in a wide

circle.

A quickly directed thought halted

his mount and he looked about once

more, at the thick forest.

This clearing was as close to the

village of Celdalo as he wanted to

come. The villagers never came into

this heavy screen of trees, but beyond

the forest, there might be some

who would watch and wonder. He

smiled grimly.

Of course, it didn’t make too much

difference what slaves might think—if

[p 33]

they could think at all, but there

was no reason to leave unnecessary

traces of the day’s work.

He swung about in his cushions

and looked back at the line of draft

beasts. They were swinging out of

line now, to form a semicircle, facing

the trees ahead.

He impressed an order on his

mount to stand, then lifted himself

out of the cushioned seat between

the armor fins. For a few seconds, he

hovered, looking down at the beast

he had been riding.

Yes, he thought, he would do well

to raise a few of these creatures.

They were tractable and comfortable

to ride. A good many caravan masters

might be persuaded to get rid

of their less comfortable mounts in

exchange for one of these, once they

had tried a day’s march.

One by one, the big saurians came

to the forest edge and entered the

clearing, then crouched, to let their

drivers swing to the ground. Barra

looked at the lead driver.

“Make your cargo stack over here,”

he ordered, “at this side of the clearing.

You will wait here for your

master.”

The man looked confused. A

vague, questioning thought came

from him. It wasn’t really a coherent

thought, but just an impression of

doubt—uncertainty. Barra frowned

impatiently.

It had been much the same when

he had ordered this man to load up

back at Tibara. Perhaps it was no

wonder Dar Makun had been forced

to learn vocalization if this was the

best slave he could find to develop

into his headman.

Carefully, he formed a projection.

It showed the carriers gathering in

their unloading circles. He made one

of the projections turn and drop its

head over another’s back. The wide

mouth opened and stubby, peg teeth

gripped the handling loop of a cargo

sling. Then the long-neck swiveled

back, to repeat the performance.

Barra watched as the man before

him nodded in obedient understanding.

He shot out a sharp, peremptory

order.

“Do it, then! Do it as shown.”

The man made noises, then turned,

shouting at the other drivers.

Barra watched as the stack of cargo

grew. At last, the final sling was positioned

and a heavy cloth cover was

dropped over the great piles. Barra

looked at the headman.

“Bring your drivers close,” he ordered.

“I have something for them

to see.”

Again, there was the moment of

confusion, but this time the man had

gathered the main sense of the command.

He turned again, shouting.

The drivers looked at each other

questioningly, then moved slowly

forward, to form a tight group before

Barra, who watched until they were

in satisfactory position.

He concentrated on the group for

a few seconds, starting the formation

of a projection to his left.

As the air glowed and started to

show form, the eyes of the drivers

swung toward it. Barra smiled tightly

and swung his distorter up. The

[p 34]

crystal flamed as he swept it across

the group of slaves.

He kept the power on, sweeping

the distorter back and forth until all

that remained was a large pool of

slime which thinned, then oozed into

the humus. At last, he tucked the rod

back under his arm and examined the

scene.

There was the pile of goods. There

were the carrier beasts. But no man

or pseudoman remained of the caravan.

His smile broadened.

Once he had sorted this cargo and

moved it to the Residence and to

various warehouses about the Estates,

all traces of Dar Makun and

his train would be gone.

To be sure, a few villages would

find that their herds had increased,

but this was nothing to worry about.

He sighed.

It had been a hard day and it

would be a hard night’s work. He

would have to forget his dignity for

the time and do real labor. But this

was necessity. And there was plenty

of profit in it as well.

So far as the rest of the world

might know, Dar Makun and his

caravan had left Kira Barra to cut

back to the northern swing. And the

turbulent null had swallowed them

without trace.

He turned away. He would have

to bring work boats in to the nearby

beach. Their surrogates were already

attuned and ready, and one of them

had been equipped with an auxiliary

power crystal. He would need that.

As the boats arrived at village

piers, the various headmen would

merely follow instructions as given

by the boat’s surrogates. He would

be done with this operation in a few

hours.

The days went on, became weeks,

then hands of weeks. Little by little,

Barra changed his attitude toward

caravan masters. Once, he had been

cautious about dealing with them,

allowing only a chosen few to do

business within his borders.

Now, however, he had found a

whole, new source of income. And a

new sense of power had come to

him. Caravans were more than welcome

at Kira Barra.

He leaned back on his new chair,

enjoying the complete ease with

which it instantly shaped to fit his

body. It was precisely like hovering

a short distance above the floor, yet

there was no strain of concentration

on some control unit. He allowed

himself to relax completely and

turned his attention to the viewer

crystal.

It was new, too. The old one of his

father’s which he had brought to the

new Residence had seemed quite inadequate

when the Residence was

redone. This new viewer had been

designed for professional use. It was

a full two feet in diameter and could

fill thousands of cubic feet with solid

projection.

Animals, trees, pseudomen, all

could be brought before him as

though physically present in the

study. Too, it was simpler than the

old one and much more accurate in

its control. He sighed.

[p 35]

The Estates had prospered. Of

course, he had been cautious. Many

caravans had come to Kira Barra and

left again, their masters highly

pleased with the fair dealings of the

Estates. Several had returned, time

and time again.

There had been others who had

come through during times when the

null was in turbulence and it was

from these that he had taken his harvest.

He had been particular in his

choices, making careful evaluation

before taking any action.

By this time, his operation was

faultless—a smooth routine which

admitted of no error. He smiled as he

remembered his fumbling efforts

with the first caravan and his halting

improvements when he had dealt

with the next. What were those fellows’

names?

He shrugged. He could remember

that first fellow practically begging

him to take action and he could remember

his own frightened evaluation

of the situation after the first

step. He had gone over a whole, long

line of alternative choices, rejecting

them one by one until the inevitable,

ideal method of operation had come

out. He smiled.

When he had finally settled on his

general method, it had been elegantly

simple. But it had been very nearly

perfect. Basically, he was still using

the same plan.

Now, of course, it was smoother

and even more simplified. There

were two general routines involved.

Most caravan masters were treated

with the greatest of consideration.

They were allowed to pass through

the Estates with only nominal fees

and invited to avail themselves of the

courtesy of the Estates at any time in

the future. If trades with the Estates

were involved, the fees were waived,

of course. And many of them had returned,

bringing goods and information,

as well as taking away the

produce of the Estates.

Then, there were those caravans

which came during turbulences in

the null and which seemed worthwhile

to the now practiced eyes of

Kio Barra. These were the ones ripe

for harvest. Their owners had been

offered the courtesy of the Estates—and

more.

They had been taken for sightseeing

tours—perhaps of the lake—perhaps