The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Sky Trap

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Sky Trap

Author: Frank Belknap Long

Release date: January 3, 2008 [eBook #24151]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Alexander Bauer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SKY TRAP ***

Nothing affected it.

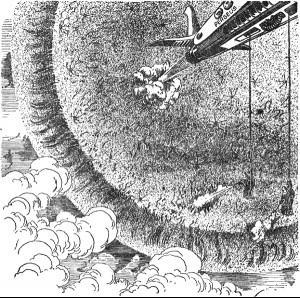

The SKY TRAP

by FRANK BELKNAP LONG

[46]Lawton enjoyed a good fight.

He stood happily trading blows

with Slashaway Tommy, his

lean-fleshed torso gleaming with

sweat. He preferred to work the

pugnacity out of himself slowly, to

savor it as it ebbed.

"Better luck next time, Slashaway,"

he said, and unlimbered a left

hook that thudded against his opponent's

jaw with such violence that

the big, hairy ape crumpled to the

resin and rolled over on his back.

Lawton brushed a lock of rust-colored

hair back from his brow and

stared down at the limp figure lying

on the descending stratoship's

slightly tilted athletic deck.

"Good work, Slashaway," he said.

"You're primitive and beetle-browed,

but you've got what it takes."

Lawton flattered himself that he

[47]

was the opposite of primitive. High

in the sky he had predicted the

weather for eight days running, with

far more accuracy than he could have

put into a punch.

They'd flash his report all over

Earth in a couple of minutes now.

From New York to London to Singapore

and back. In half an hour he'd

be donning street clothes and stepping

out feeling darned good.

He had fulfilled his weekly obligation

to society by manipulating meteorological

instruments for forty-five

minutes, high in the warm, upper

stratosphere and worked off his pugnacity

by knocking down a professional

gym slugger. He would have

a full, glorious week now to work

off all his other drives.

The stratoship's commander, Captain

Forrester, had come up, and was

staring at him reproachfully. "Dave,

I don't hold with the reforming Johnnies

who want to re-make human

nature from the ground up. But

you've got to admit our generation

knows how to keep things humming

with a minimum of stress. We don't

have world wars now because we

work off our pugnacity by sailing into

gym sluggers eight or ten times a

week. And since our romantic emotions

can be taken care of by tactile

television we're not at the mercy of

every brainless bit of fluff's calculated

ankle appeal."

Lawton turned, and regarded him

quizzically. "Don't you suppose I realize

that? You'd think I just blew

in from Mars."

"All right. We have the outlets,

the safety valves. They are supposed

to keep us civilized. But you don't

derive any benefit from them."

"The heck I don't. I exchange

blows with Slashaway every time I

board the Perseus. And as for women—well,

there's just one woman in

the world for me, and I wouldn't exchange

her for all the Turkish images

in the tactile broadcasts from Stamboul."

"Yes, I know. But you work off

your primitive emotions with too

much gusto. Even a cast-iron gym

slugger can bruise. That last blow

was—brutal. Just because Slashaway

gets thumped and thudded all over

by the medical staff twice a week

doesn't mean he can take—"

The stratoship lurched suddenly.

The deck heaved up under Lawton's

feet, hurling him against Captain

Forrester and spinning both men

around so that they seemed to be

waltzing together across the ship.

The still limp gym slugger slid downward,

colliding with a corrugated

metal bulkhead and sloshing back

and forth like a wet mackerel.

A full minute passed before Lawton

could put a stop to that. Even

while careening he had been alive to

Slashaway's peril, and had tried to

leap to his aid. But the ship's steadily

increasing gyrations had hurled him

away from the skipper and against

a massive vaulting horse, barking

the flesh from his shins and spilling

him with violence onto the deck.

He crawled now toward the prone

gym slugger on his hands and knees,

his temples thudding. The gyrations

ceased an instant before he reached

Slashaway's side. With an effort he

lifted the big man up, propped him

against the bulkhead and shook him

until his teeth rattled. "Slashaway,"

he muttered. "Slashaway, old fellow."

Slashaway opened blurred eyes,

"Phew!" he muttered. "You sure

socked me hard, sir."

"You went out like a light," explained

Lawton gently. "A minute

before the ship lurched."

"The ship lurched, sir?"

"Something's very wrong, Slashaway.

The ship isn't moving. There

are no vibrations and—Slashaway,

are you hurt? Your skull thumped

against that bulkhead so hard I was

afraid—"

"Naw, I'm okay. Whatd'ya mean,

the ship ain't moving? How could it

stop?"

Lawton said. "I don't know, Slashaway."

[48]

Helping the gym slugger to

his feet he stared apprehensively

about him. Captain Forrester was

kneeling on the resin testing his hocks

for sprains with splayed fingers, his

features twitching.

"Hurt badly, sir?"

The Commander shook his head.

"I don't think so. Dave, we are twenty

thousand feet up, so how in hell could

we be stationary in space?"

"It's all yours, skipper."

"I must say you're helpful."

Forrester got painfully to his feet

and limped toward the athletic compartment's

single quartz port—a

small circle of radiance on a level

with his eyes. As the port sloped

downward at an angle of nearly sixty

degrees all he could see was a diffuse

glimmer until he wedged his

brow in the observation visor and

stared downward.

Lawton heard him suck in his

breath sharply. "Well, sir?"

"There are thin cirrus clouds directly

beneath us. They're not moving."

Lawton gasped, the sense of being

in an impossible situation swelling

to nightmare proportions within him.

What could have happened?

Directly behind him, close to a

bulkhead chronometer, which was

clicking out the seconds with unabashed

regularity, was a misty blue

visiplate that merely had to be

switched on to bring the pilots into

view.

The Commander hobbled toward it,

and manipulated a rheostat. The two

pilots appeared side by side on the

screen, sitting amidst a spidery network

of dully gleaming pipe lines

and nichrome humidification units.

They had unbuttoned their high-altitude

coats and their stratosphere

helmets were resting on their knees.

The Jablochoff candle light which

flooded the pilot room accentuated

the haggardness of their features,

which were a sickly cadaverous hue.

The captain spoke directly into the

visiplate. "What's wrong with the

ship?" he demanded. "Why aren't we

descending? Dawson, you do the

talking!"

One of the pilots leaned tensely

forward, his shoulders jerking. "We

don't know, sir. The rotaries went

dead when the ship started gyrating.

We can't work the emergency torps

and the temperature is rising."

"But—it defies all logic," Forrester

muttered. "How could a metal ship

weighing tons be suspended in the

air like a balloon? It is stationary,

but it is not buoyant. We seem in all

respects to be frozen in."

"The explanation may be simpler

than you dream," Lawton said.

"When we've found the key."

The Captain swung toward him.

"Could you find the key, Dave?"

"I should like to try. It may be

hidden somewhere on the ship, and

then again, it may not be. But I

should like to go over the ship with

a fine-tooth comb, and then I should

like to go over outside, thoroughly.

Suppose you make me an emergency

mate and give me a carte blanche,

sir."

Lawton got his carte blanche. For

two hours he did nothing spectacular,

but he went over every inch of the

ship. He also lined up the crew and

pumped them. The men were as completely

in the dark as the pilots and

the now completely recovered Slashaway,

who was following Lawton

about like a doting seal.

"You're a right guy, sir. Another

two or three cracks and my noggin

would've split wide open."

"But not like an eggshell, Slashaway.

Pig iron develops fissures under

terrific pounding but your cranium

seems to be more like tempered

steel. Slashaway, you won't understand

this, but I've got to talk to

somebody and the Captain is too busy

to listen.

"I went over the entire ship because

I thought there might be a

hidden source of buoyancy somewhere.

It would take a lot of air

[49]

bubbles to turn this ship into a balloon,

but there are large vacuum

chambers under the multiple series

condensers in the engine room which

conceivably could have sucked in a

helium leakage from the carbon pile

valves. And there are bulkhead porosities

which could have clogged."

"Yeah," muttered Slashaway,

scratching his head. "I see what you

mean, sir."

"It was no soap. There's nothing

inside the ship that could possibly

keep us up. Therefore there must be

something outside that isn't air. We

know there is air outside. We've

stuck our heads out and sniffed it.

And we've found out a curious thing.

"Along with the oxygen there is

water vapor, but it isn't H2O. It's

HO. A molecular arrangement like

that occurs in the upper Solar atmosphere,

but nowhere on Earth.

And there's a thin sprinkling of hydrocarbon

molecules out there too.

Hydrocarbon appears ordinarily as

methane gas, but out there it rings

up as CH. Methane is CH4. And

there are also scandium oxide molecules

making unfamiliar faces at us.

And oxide of boron—with an equational

limp."

"Gee," muttered Slashaway. "We're

up against it, eh?"

Lawton was squatting on his hams

beside an emergency 'chute opening

on the deck of the Penguin's weather

observatory. He was letting down a

spliced beryllium plumb line, his

gaze riveted on the slowly turning

horizontal drum of a windlass which

contained more than two hundred

feet of gleaming metal cordage.

Suddenly as he stared the drum

stopped revolving. Lawton stiffened,

a startled expression coming into his

face. He had been playing a hunch

that had seemed as insane, rationally

considered, as his wild idea about the

bulkhead porosities. For a moment

he was stunned, unable to believe

that he had struck pay dirt. The

winch indicator stood at one hundred

and three feet, giving him a

rich, fruity yield of startlement.

One hundred feet below him the

plummet rested on something solid

that sustained it in space. Scarcely

breathing, Lawton leaned over the

windlass and stared downward. There

was nothing visible between the ship

and the fleecy clouds far below except

a tiny black dot resting on vacancy

and a thin beryllium plumb line

ascending like an interrogation point

from the dot to the 'chute opening.

"You see something down there?"

Slashaway asked.

Lawton moved back from the windlass,

his brain whirling. "Slashaway

there's a solid surface directly beneath

us, but it's completely invisible."

"You mean it's like a frozen cloud,

sir?"

"No, Slashaway. It doesn't shimmer,

or deflect light. Congealed water

vapor would sink instantly to earth."

"You think it's all around us, sir?"

Lawton stared at Slashaway aghast.

In his crude fumblings the gym slugger

had ripped a hidden fear right out

of his subconsciousness into the light.

"I don't know, Slashaway," he muttered.

"I'll get at that next."

A half hour later Lawton sat beside

the captain's desk in the control

room, his face drained of all

color. He kept his gaze averted as he

talked. A man who succeeds too well

with an unpleasant task may develop

a subconscious sense of guilt.

"Sir, we're suspended inside a hollow

sphere which resembles a huge,

floating soap bubble. Before we

ripped through it it must have had

a plastic surface. But now the tear

has apparently healed over, and the

shell all around us is as resistant as

steel. We're completely bottled up, sir.

I shot rocket leads in all directions to

make certain."

The expression on Forrester's face

sold mere amazement down the river.

He could not have looked more

startled if the nearer planets had

[50]

yielded their secrets chillingly, and

a super-race had appeared suddenly

on Earth.

"Good God, Dave. Do you suppose

something has happened to space?"

Lawton raised his eyes with a shudder.

"Not necessarily, sir. Something

has happened to us. We're floating

through the sky in a huge, invisible

bubble of some sort, but we don't

know whether it has anything to do

with space. It may be a meteorological

phenomenon."

"You say we're floating?"

"We're floating slowly westward.

The clouds beneath us have been receding

for fifteen or twenty minutes

now."

"Phew!" muttered Forrester. "That

means we've got to—"

He broke off abruptly. The Perseus'

radio operator was standing in the

doorway, distress and indecision in

his gaze. "Our reception is extremely

sporadic, sir," he announced. "We can

pick up a few of the stronger broadcasts,

but our emergency signals

haven't been answered."

"Keep trying," Forrester ordered.

"Aye, aye, sir."

The captain turned to Lawton.

"Suppose we call it a bubble. Why are

we suspended like this, immovably?

Your rocket leads shot up, and the

plumb line dropped one hundred feet.

Why should the ship itself remain

stationary?"

Lawton said: "The bubble must

possess sufficient internal equilibrium

to keep a big, heavy body suspended

at its core. In other words, we must

be suspended at the hub of converging

energy lines."

"You mean we're surrounded by an

electromagnetic field?"

Lawton frowned. "Not necessarily,

sir. I'm simply pointing out that

there must be an energy tug of some

sort involved. Otherwise the ship

would be resting on the inner surface

of the bubble."

Forrester nodded grimly. "We

should be thankful, I suppose, that we

can move about inside the ship. Dave,

do you think a man could descend to

the inner surface?"

"I've no doubt that a man could, sir.

Shall I let myself down?"

"Absolutely not. Damn it, Dave, I

need your energies inside the ship. I

could wish for a less impulsive first

officer, but a man in my predicament

can't be choosy."

"Then what are your orders, sir?"

"Orders? Do I have to order you to

think? Is working something out for

yourself such a strain? We're drifting

straight toward the Atlantic

Ocean. What do you propose to do

about that?"

"I expect I'll have to do my best,

sir."

Lawton's "best" conflicted dynamically

with the captain's orders. Ten

minutes later he was descending,

hand over hand, on a swaying emergency

ladder.

"Tough-fibered Davie goes down to

look around," he grumbled.

He was conscious that he was flirting

with danger. The air outside was

breathable, but would the diffuse, unorthodox

gases injure his lungs? He

didn't know, couldn't be sure. But he

had to admit that he felt all right so

far. He was seventy feet below the

ship and not at all dizzy. When he

looked down he could see the purple

domed summits of mountains between

gaps in the fleecy cloud blanket.

He couldn't see the Atlantic Ocean—yet.

He descended the last thirty

feet with mounting confidence. At the

end of the ladder he braced himself

and let go.

He fell about six feet, landing on

his rump on a spongy surface that

bounced him back and forth. He was

vaguely incredulous when he found

himself sitting in the sky staring

through his spread legs at clouds and

mountains.

He took a deep breath. It struck

him that the sensation of falling could

be present without movement downward

through space. He was beginning

to experience such a sensation.

[51]

His stomach twisted and his brain

spun.

He was suddenly sorry he had tried

this. It was so damnably unnerving he

was afraid of losing all emotional control.

He stared up, his eyes squinting

against the sun. Far above him the

gleaming, wedge-shaped bulk of the

Perseus loomed colossally, blocking

out a fifth of the sky.

Lowering his right hand he ran his

fingers over the invisible surface beneath

him. The surface felt rubbery,

moist.

He got swayingly to his feet and

made a perilous attempt to walk

through the sky. Beneath his feet the

mysterious surface crackled, and

little sparks flew up about his legs.

Abruptly he sat down again, his face

ashen.

From the emergency 'chute opening

far above a massive head appeared.

"You all right, sir," Slashaway

called, his voice vibrant with

concern.

"Well, I—"

"You'd better come right up, sir.

Captain's orders."

"All right," Lawton shouted. "Let

the ladder down another ten feet."

Lawton ascended rapidly, resentment

smouldering within him. What

right had the skipper to interfere? He

had passed the buck, hadn't he?

Lawton got another bad jolt the

instant he emerged through the

'chute opening. Captain Forrester

was leaning against a parachute rack

gasping for breath, his face a livid

hue.

Slashaway looked equally bad. His

jaw muscles were twitching and he

was tugging at the collar of his gym

suit.

Forrester gasped: "Dave, I tried

to move the ship. I didn't know you

were outside."

"Good God, you didn't know—"

"The rotaries backfired and used

up all the oxygen in the engine room.

Worse, there's been a carbonic oxide

seepage. The air is contaminated

throughout the ship. We'll have to

open the ventilation valves immediately.

I've been waiting to see if—if

you could breathe down there. You're

all right, aren't you? The air is

breathable?"

Lawton's face was dark with fury.

"I was an experimental rat in the sky,

eh?"

"Look, Dave, we're all in danger.

Don't stand there glaring at me.

Naturally I waited. I have my crew to

think of."

"Well, think of them. Get those

valves open before we all have convulsions."

A half hour later charcoal gas was

mingling with oxygen outside the

ship, and the crew was breathing it

in again gratefully. Thinly dispersed,

and mixed with oxygen it seemed all

right. But Lawton had misgivings. No

matter how attenuated a lethal gas is

it is never entirely harmless. To make

matters worse, they were over the Atlantic

Ocean.

Far beneath them was an emerald

turbulence, half obscured by eastward

moving cloud masses. The bubble

was holding, but the morale of the

crew was beginning to sag.

Lawton paced the control room.

Deep within him unsuspected energies

surged. "We'll last until the oxygen

is breathed up," he exclaimed.

"We'll have four or five days, at most.

But we seem to be traveling faster

than an ocean liner. With luck, we'll

be in Europe before we become carbon

dioxide breathers."

"Will that help matters, Dave?"

said the captain wearily.

"If we can blast our way out, it

will."

The Captain's sagging body jackknifed

erect. "Blast our way out?

What do you mean, Dave?"

"I've clamped expulsor disks on the

cosmic ray absorbers and trained

them downward. A thin stream of

accidental neutrons directed against

the bottom of the bubble may disrupt

its energies—wear it thin. It's a long

[52]

gamble, but worth taking. We're staking

nothing, remember?"

Forrester sputtered: "Nothing but

our lives! If you blast a hole in the

bubble you'll destroy its energy balance.

Did that occur to you? Inside a

lopsided bubble we may careen dangerously

or fall into the sea before we

can get the rotaries started."

"I thought of that. The pilots are

standing by to start the rotaries the

instant we lurch. If we succeed in

making a rent in the bubble we'll

break out the helicoptic vanes and

descend vertically. The rotaries won't

backfire again. I've had their burnt-out

cylinder heads replaced."

An agitated voice came from the

visiplate on the captain's desk: "Tuning

in, sir."

Lawton stopped pacing abruptly.

He swung about and grasped the desk

edge with both hands, his head touching

Forrester's as the two men stared

down at the horizontal face of petty

officer James Caldwell.

Caldwell wasn't more than twenty-two

or three, but the screen's opalescence

silvered his hair and misted

the outlines of his jaw, giving him an

aspect of senility.

"Well, young man," Forrester

growled. "What is it? What do you

want?"

The irritation in the captain's voice

seemed to increase Caldwell's agitation.

Lawton had to say: "All right,

lad, let's have it," before the information

which he had seemed bursting to

impart could be wrenched out of him.

It came in erratic spurts. "The

bubble is all blooming, sir. All around

inside there are big yellow and purple

growths. It started up above, and—and

spread around. First there was

just a clouding over of the sky, sir,

and then—stalks shot out."

For a moment Lawton felt as

though all sanity had been squeezed

from his brain. Twice he started to

ask a question and thought better

of it.

Pumpings were superfluous when

he could confirm Caldwell's statement

in half a minute for himself. If Caldwell

had cracked up—

Caldwell hadn't cracked. When

Lawton walked to the quartz port and

stared down all the blood drained

from his face.

The vegetation was luxuriant, and

unearthly. Floating in the sky were

serpentine tendrils as thick as a man's

wrist, purplish flowers and ropy fungus

growths. They twisted and

writhed and shot out in all directions,

creating a tangle immediately beneath

him and curving up toward the

ship amidst a welter of seed pods.

He could see the seeds dropping—dropping

from pods which reminded

him of the darkly horned skate egg

sheaths which he had collected in his

boyhood from sea beaches at ebb tide.

It was the unwholesomeness of the

vegetation which chiefly unnerved

him. It looked dank, malarial. There

were decaying patches on the fungus

growths and a miasmal mist was descending

from it toward the ship.

The control room was completely

still when he turned from the quartz

port to meet Forrester's startled gaze.

"Dave, what does it mean?" The

question burst explosively from the

captain's lips.

"It means—life has appeared and

evolved and grown rotten ripe inside

the bubble, sir. All in the space of an

hour or so."

"But that's—impossible."

Lawton shook his head. "It isn't at

all, sir. We've had it drummed into

us that evolution proceeds at a snailish

pace, but what proof have we that

it can't mutate with lightning-like rapidity?

I've told you there are gases

outside we can't even make in a

chemical laboratory, molecular arrangements

that are alien to earth."

"But plants derive nourishment

from the soil," interpolated Forrester.

"I know. But if there are alien

gases in the air the surface of the

bubble must be reeking with unheard

of chemicals. There may be compounds

inside the bubble which have

[53]

so sped up organic processes that a

hundred million year cycle of mutations

has been telescoped into an

hour."

Lawton was pacing the floor again.

"It would be simpler to assume that

seeds of existing plants became somehow

caught up and imprisoned in the

bubble. But the plants around us

never existed on earth. I'm no botanist,

but I know what the Congo has

on tap, and the great rain forests of

the Amazon."

"Dave, if the growth continues it

will fill the bubble. It will choke off all

our air."

"Don't you suppose I realize that?

We've got to destroy that growth before

it destroys us."

It was pitiful to watch the crew's

morale sag. The miasmal taint of the

ominously proliferating vegetation

was soon pervading the ship, spreading

demoralization everywhere.

It was particularly awful straight

down. Above a ropy tangle of livid

vines and creepers a kingly stench

weed towered, purplish and bloated

and weighted down with seed pods.

It seemed sentient, somehow. It

was growing so fast that the evil odor

which poured from it could be correlated

with the increase of tension inside

the ship. From that particular

plant, minute by slow minute, there

surged a continuously mounting offensiveness,

like nothing Lawton had

ever smelt before.

The bubble had become a blooming

horror sailing slowly westward above

the storm-tossed Atlantic. And all the

chemical agents which Lawton

sprayed through the ventilation

valves failed to impede the growth or

destroy a single seed pod.

It was difficult to kill plant life

with chemicals which were not harmful

to man. Lawton took dangerous

risks, increasing the unwholesomeness

of their rapidly dwindling air

supply by spraying out a thin diffusion

of problematically poisonous

acids.

It was no sale. The growths increased

by leaps and bounds, as

though determined to show their resentment

of the measures taken

against them by marshalling all their

forces in a demoralizing plantkrieg.

Thwarted, desperate, Lawton

played his last card. He sent five

members of the crew, equipped with

blow guns. They returned screaming.

Lawton had to fortify himself with a

double whiskey soda before he could

face the look of reproach in their eyes

long enough to get all of the prickles

out of them.

From then on pandemonium

reigned. Blue funk seized the petty

officers while some of the crew ran

amuck. One member of the engine

watch attacked four of his companions

with a wrench; another went

into the ship's kitchen and slashed

himself with a paring knife. The assistant

engineer leapt through a

'chute opening, after avowing that he

preferred impalement to suffocation.

He was impaled. It was horrible.

Looking down Lawton could see his

twisted body dangling on a crimson-stippled

thornlike growth forty feet

in height.

Slashaway was standing at his elbow

in that Waterloo moment, his

rough-hewn features twitching. "I

can't stand it, sir. It's driving me

squirrelly."

"I know, Slashaway. There's something

worse than marijuana weed

down there."

Slashaway swallowed hard. "That

poor guy down there did the wise

thing."

Lawton husked: "Stamp on that

idea, Slashaway—kill it. We're

stronger than he was. There isn't an

ounce of weakness in us. We've got

what it takes."

"A guy can stand just so much."

"Bosh. There's no limit to what a

man can stand."

From the visiplate behind them

came an urgent voice: "Radio room

tuning in, sir."

Lawton swung about. On the flickering

[54]

screen the foggy outlines of a

face appeared and coalesced into

sharpness.

The Perseus radio operator was

breathless with excitement. "Our reception

is improving, sir. European

short waves are coming in strong.

The static is terrific, but we're getting

every station on the continent,

and most of the American stations."

Lawton's eyes narrowed to exultant

slits. He spat on the deck, a slow tremor

shaking him.

"Slashaway, did you hear that?

We've done it. We've won against

hell and high water."

"We done what, sir?"

"The bubble, you ape—it must be

wearing thin. Hell's bells, do you

have to stand there gaping like a moronic

ninepin? I tell you, we've got

it licked."

"I can't stand it, sir. I'm going

nuts."

"No you're not. You're slugging the

thing inside you that wants to quit.

Slashaway, I'm going to give the crew

a first-class pep talk. There'll be no

stampeding while I'm in command

here."

He turned to the radio operator.

"Tune in the control room. Tell the

captain I want every member of the

crew lined up on this screen immediately."

The face in the visiplate paled. "I

can't do that, sir. Ship's regulations—"

Lawton transfixed the operator

with an irate stare. "The captain told

you to report directly to me, didn't

he?"

"Yes sir, but—"

"If you don't want to be cashiered,

snap into it."

"Yes—yessir."

The captain's startled face preceded

the duty-muster visiview by a full

minute, seeming to project outward

from the screen. The veins on his neck

were thick blue cords.

"Dave," he croaked. "Are you out

of your mind? What good will talking

do now?"

"Are the men lined up?" Lawton

rapped, impatiently.

Forrester nodded. "They're all in

the engine room, Dave."

"Good. Block them in."

The captain's face receded, and a

scene of tragic horror filled the opalescent

visiplate. The men were not

standing at attention at all. They

were slumping against the Perseus'

central charging plant in attitudes of

abject despair.

Madness burned in the eyes of

three or four of them. Others had torn

open their shirts, and raked their

flesh with their nails. Petty officer

Caldwell was standing as straight

as a totem pole, clenching and unclenching

his hands. The second assistant

engineer was sticking out his

tongue. His face was deadpan, which

made what was obviously a terror reflex

look like an idiot's grimace.

Lawton moistened his lips. "Men,

listen to me. There is some sort of

plant outside that is giving off deliriant

fumes. A few of us seem to be

immune to it.

"I'm not immune, but I'm fighting

it, and all of you boys can fight it too.

I want you to fight it to the top of

your courage. You can fight anything

when you know that just around the

corner is freedom from a beastliness

that deserves to be licked—even if it's

only a plant.

"Men, we're blasting our way free.

The bubble's wearing thin. Any minute

now the plants beneath us may

fall with a soggy plop into the Atlantic

Ocean.

"I want every man jack aboard this

ship to stand at his post and obey orders.

Right this minute you look like

something the cat dragged in. But

most men who cover themselves with

glory start off looking even worse

than you do."

He smiled wryly.

"I guess that's all. I've never had

to make a speech in my life, and I'd

hate like hell to start now."

It was petty officer Caldwell who

[55]

started the chant. He started it, and

the men took it up until it was coming

from all of them in a full-throated

roar.

I'm a tough, true-hearted skyman,

Careless and all that, d'ye see?

Never at fate a railer,

What is time or tide to me?

All must die when fate shall will it,

I can never die but once,

I'm a tough, true-hearted skyman;

He who fears death is a dunce.

Lawton squared his shoulders.

With a crew like that nothing could

stop him! Ah, his energies were surging

high. The deliriant weed held no

terrors for him now. They were stout-hearted

lads and he'd go to hell with

them cheerfully, if need be.

It wasn't easy to wait. The next

half hour was filled with a steadily

mounting tension as Lawton moved

like a young tornado about the ship,

issuing orders and seeing that each

man was at his post.

"Steady, Jimmy. The way to fight a

deliriant is to keep your mind on a

set task. Keep sweating, lad."

"Harry, that winch needs tightening.

We can't afford to miss a trick."

"Yeah, it will come suddenly. We've

got to get the rotaries started the instant

the bottom drops out."

He was with the captain and Slashaway

in the control room when it

came. There was a sudden, grinding

jolt, and the captain's desk started

moving toward the quartz port, carrying

Lawton with it.

"Holy Jiminy cricket," exclaimed

Slashaway.

The deck tilted sharply; then righted

itself. A sudden gush of clear, cold

air came through the ventilation

valves as the triple rotaries started

up with a roar.

Lawton and the captain reached the

quartz port simultaneously. Shoulder

to shoulder they stood staring down

at the storm-tossed Atlantic, electrified

by what they saw.

Floating on the waves far beneath

them was an undulating mass of vegetation,

its surface flecked with glinting

foam. As it rose and fell in waning

sunlight a tainted seepage spread

about it, defiling the clean surface of

the sea.

But it wasn't the floating mass

which drew a gasp from Forrester,

and caused Lawton's scalp to prickle.

Crawling slowly across that Sargasso-like

island of noxious vegetation

was a huge, elongated shape which

bore a nauseous resemblance to a

mottled garden slug.

Forrester was trembling visibly

when he turned from the quartz port.

"God, Dave, that would have been

the last straw. Animal life. Dave, I—I

can't realize we're actually out of

it."

"We're out, all right," Lawton said,

hoarsely. "Just in time, too. Skipper,

you'd better issue grog all around.

The men will be needing it. I'm taking

mine straight. You've accused me of

being primitive. Wait till you see me

an hour from now."

Dr. Stephen Halday stood in the

door of his Appalachian mountain

laboratory staring out into the pine-scented

dusk, a worried expression

on his bland, small-featured face. It

had happened again. A portion of his

experiment had soared skyward, in a

very loose group of highly energized

wavicles. He wondered if it wouldn't

form a sort of sub-electronic macrocosm

high in the stratosphere, altering

even the air and dust particles

which had spurted up with it, its uncharged

atomic particles combining

with hydrogen and creating new

molecular arrangements.

If such were the case there would

be eight of them now. His bubbles,

floating through the sky. They

couldn't possibly harm anything—way

up there in the stratosphere. But

he felt a little uneasy about it all the

same. He'd have to be more careful

in the future, he told himself. Much

more careful. He didn't want the

Controllers to turn back the clock of

civilization a century by stopping all

atom-smashing experiments.

Transcriber's Note:

This e-text was produced from Comet July 1941. Extensive

research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright

on this publication was renewed.

Featured Books

Extensions of Known Ranges of Mexican Bats

Sydney Anderson

extend the known geographic ranges to the northwardon either the east or the west coast of Mexico. C...

In New England Fields and Woods

Rowland Evans Robinson

now and hereaftercan only be memories, though they are yetnear him and he may still hear their voice...

![Birds Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 3, No. 2 [February, 1898]](https://img.gamelinxhub.com/images/pg34294.cover.small.jpg)

Birds Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 3, No. 2 [February, 1898]

Various

,thought him fitter to meet occasionallyin the open air than as a guest attable and fireside. There ...

Wild Animals at Home

Ernest Thompson Seton

ntain haven of wild life.Whenever travellers penetrate into remote regionswhere human hunters are un...

The Castaways

Mayne Reid

ance. The countenance so marked is unmistakably of Milesian type. So it should be, as its owner is a...

The Boy Hunters

Mayne Reid

ver, about a mile below the village. I say it stood there many years ago; but it is very likely that...

The Lock and Key Library: Classic Mystery and Detective Stories: Modern English

� The Red-Headed League Egerton Castle The Baron's Quarry Stanley J. Weym...

A Journey in Other Worlds: A Romance of the Future

John Jacob Astor

ture whose existence we as yet little morethan suspect. How much more interesting it would be if, i...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "The Sky Trap" :