The Project Gutenberg eBook of Masters of Space

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Masters of Space

Author: E. E. Smith

E. Everett Evans

Illustrator: Phil Berry

Release date: September 24, 2007 [eBook #22754]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Robert Cicconetti, Stephen Blundell and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MASTERS OF SPACE ***

The Masters had ruled all space

with an unconquerable iron fist. But

the Masters were gone. And this new,

young race who came now to take their

place—could they hope to defeat the

ancient Enemy of All?

PART ONE

MASTERS

OF

SPACE

By EDWARD E. SMITH &

E. EVERETT EVANS

Illustrated by BERRY

I

"BUT didn't you feel anything,

Javo?" Strain

was apparent in every line of

Tula's taut, bare body. "Nothing

at all?"

"Nothing whatever." The

one called Javo relaxed from

his rigid concentration.

"Nothing has changed. Nor

will it."

"That conclusion is indefensible!"

Tula snapped.

"With the promised return of

the Masters there must and

will be changes. Didn't any

of you feel anything?"

Her hot, demanding eyes

swept the group; a group

whose like, except for physical

perfection, could be found

in any nudist colony.

No one except Tula had

felt a thing.

"That fact is not too surprising,"

Javo said finally.

"You have the most sensitive

receptors of us all. But are

you sure?"

"I am sure. It was the

thought-form of a living

Master."

"Do you think that the

Master perceived your web?"

"It is certain. Those who

built us are stronger than

we."

"That is true. As they

promised, then, so long and

long ago, our Masters are returning

home to us."

Jarvis Hilton of Terra, the

youngest man yet to be assigned

to direct any such tremendous

deep-space undertaking

as Project Theta Orionis,

sat in conference with

his two seconds-in-command.

Assistant Director Sandra

Cummings, analyst-synthesist

and semantician, was tall,

blonde and svelte. Planetographer

William Karns—a

black-haired, black-browed,

black-eyed man of thirty—was

third in rank of the scientific

group.

"I'm telling you, Jarve, you

can't have it both ways,"

Karns declared. "Captain

Sawtelle is old-school Navy

brass. He goes strictly by the

book. So you've got to draw

a razor-sharp line; exactly

where the Advisory Board's

directive puts it. And next

time he sticks his ugly puss

across that line, kick his face

in. You've been Caspar Milquetoast

Two ever since we

left Base."

"That's the way it looks to

you?" Hilton's right hand became

a fist. "The man has

age, experience and ability.

I've been trying to meet him

on a ground of courtesy and

decency."

"Exactly. And he doesn't

recognize the existence of

either. And, since the Board

rammed you down his throat

instead of giving him old

Jeffers, you needn't expect

him to."

"You may be right, Bill.

What do you think, Dr. Cummings?"

The girl said: "Bill's right.

Also, your constant appeasement

isn't doing the morale

of the whole scientific group

a bit of good."

"Well, I haven't enjoyed it,

either. So next time I'll pin

his ears back. Anything

else?"

"Yes, Dr. Hilton, I have a

squawk of my own. I know I

was rammed down your

throat, but just when are you

going to let me do some

work?"

"None of us has much of

anything to do yet, and won't

have until we light somewhere.

You're off base a

country mile."

"I'm not off base. You did

want Eggleston, not me."

"Sure I did. I've worked

with him and know what he

can do. But I'm not holding a

grudge about it."

"No? Why, then, are you

on first-name terms with

everyone in the scientific

group except me? Supposedly

your first assistant?"

"That's easy!" Hilton

snapped. "Because you've

been carrying chips on both

shoulders ever since you

came aboard ... or at least I

thought you were." Hilton

grinned suddenly and held

out his hand. "Sorry, Sandy—I'll

start all over again."

"I'm sorry too, Chief."

They shook hands warmly.

"I was pretty stiff, I guess,

but I'll be good."

"You'll go to work right

now, too. As semantician. Dig

out that directive and tear it

down. Draw that line Bill

talked about."

"Can do, boss." She swung

to her feet and walked out of

the room, her every movement

one of lithe and easy

grace.

Karns followed her with

his eyes. "Funny. A trained-dancer

Ph.D. And a Miss

America type, like all the

other women aboard this

spacer. I wonder if she'll

make out."

"So do I. I still wish they'd

given me Eggy. I've never

seen an executive-type female

Ph.D. yet that was worth the

cyanide it would take to poison

her."

"That's what Sawtelle

thinks of you, too, you

know."

"I know; and the Board

does know its stuff. So I'm

really hoping, Bill, that she

surprises me as much as I intend

to surprise the Navy."

ALARM bells clanged as

the mighty Perseus

blinked out of overdrive.

Every crewman sprang to his

post.

"Mister Snowden, why did

we emerge without orders

from me?" Captain Sawtelle

bellowed, storming into the

control room three jumps behind

Hilton.

"The automatics took control,

sir," he said, quietly.

"Automatics! I give the orders!"

"In this case, Captain Sawtelle,

you don't," Hilton said.

Eyes locked and held. To

Sawtelle, this was a new and

strange co-commander. "I

would suggest that we discuss

this matter in private."

"Very well, sir," Sawtelle

said; and in the captain's

cabin Hilton opened up.

"For your information,

Captain Sawtelle, I set my

inter-space coupling detectors

for any objective I choose.

When any one of them reacts,

it trips the kickers and we

emerge. During any emergency

outside the Solar System

I am in command—with

the provision that I must relinquish

command to you in

case of armed attack on us."

"Where do you think you

found any such stuff as that

in the directive? It isn't there

and I know my rights."

"It is, and you don't. Here

is a semantic chart of the

whole directive. As you will

note, it overrides many Navy

regulations. Disobedience of

my orders constitutes mutiny

and I can—and will—have

you put in irons and sent

back to Terra for court-martial.

Now let's go back."

In the control room, Hilton

said, "The target has a mass

of approximately five hundred

metric tons. There is

also a significant amount of

radiation characteristic of

uranexite. You will please execute

search, Captain Sawtelle."

And Captain Sawtelle ordered

the search.

"What did you do to the

big jerk, boss?" Sandra whispered.

"What you and Bill suggested,"

Hilton whispered

back. "Thanks to your analysis

of the directive—pure

gobbledygook if there ever

was any—I could. Mighty

good job, Sandy."

TEN or fifteen more minutes

passed. Then:

"Here's the source of radiation,

sir," a searchman reported.

"It's a point source,

though, not an object at this

range."

"And here's the artifact,

sir," Pilot Snowden said.

"We're coming up on it fast.

But ... but what's a skyscraper

skeleton doing out here in

interstellar space?"

As they closed up, everyone

could see that the thing

did indeed look like the

metallic skeleton of a great

building. It was a huge cube,

measuring well over a hundred

yards along each edge.

And it was empty.

"That's one for the book,"

Sawtelle said.

"And how!" Hilton agreed.

"I'll take a boat ... no, suits

would be better. Karns, Yarborough,

get Techs Leeds and

Miller and suit up."

"You'll need a boat escort,"

Sawtelle said. "Mr. Ashley,

execute escort Landing Craft

One, Two, and Three."

The three landing craft approached

that enigmatic lattice-work

of structural steel

and stopped. Five grotesquely

armored figures wafted

themselves forward on pencils

of force. Their leader,

whose suit bore the number

"14", reached a mammoth

girder and worked his way

along it up to a peculiar-looking

bulge. The whole immense

structure vanished, leaving

men and boats in empty

space.

Sawtelle gasped. "Snowden!

Are you holding 'em?"

"No, sir. Faster than light;

hyperspace, sir."

"Mr. Ashby, did you have

your interspace rigs set?"

"No, sir. I didn't think of

it, sir."

"Doctor Cummings, why

weren't yours out?"

"I didn't think of such a

thing, either—any more than

you did," Sandra said.

Ashby, the Communications

Officer, had been working

the radio. "No reply from

anyone, sir," he reported.

"Oh, no!" Sandra exclaimed.

Then, "But look!

They're firing pistols—especially

the one wearing number

fourteen—but pistols?"

"Recoil pistols—sixty-threes—for

emergency use in

case of power failure," Ashby

explained. "That's it ... but I

can't see why all their power

went out at once. But Fourteen—that's

Hilton—is really

doing a job with that sixty-three.

He'll be here in a couple

of minutes."

And he was. "Every power

unit out there—suits

and boats both—drained,"

Hilton reported. "Completely

drained. Get some help

out there fast!"

In an enormous structure

deep below the surface of a

far-distant world a group of

technicians clustered together

in front of one section of

a two-miles long control

board. They were staring at a

light that had just appeared

where no light should have

been.

"Someone's brain-pan will

be burned out for this," one

of the group radiated harshly.

"That unit was inactivated

long ago and it has not been

reactivated."

"Someone committed an error,

Your Loftiness?"

"Silence, fool! Stretts do

not commit errors!"

AS soon as it was clear that

no one had been injured,

Sawtelle demanded, "How

about it, Hilton?"

"Structurally, it was high-alloy

steel. There were many

bulges, possibly containing

mechanisms. There were

drive-units of a non-Terran

type. There were many projectors,

which—at a rough

guess—were a hundred times

as powerful as any I have

ever seen before. There were

no indications that the thing

had ever been enclosed, in

whole or in part. It certainly

never had living quarters for

warm-blooded, oxygen-breathing

eaters of organic food."

Sawtelle snorted. "You

mean it never had a crew?"

"Not necessarily...."

"Bah! What other kind of

intelligent life is there?"

"I don't know. But before

we speculate too much, let's

look at the tri-di. The camera

may have caught something I

missed."

It hadn't. The three-dimensional

pictures added nothing.

"It probably was operated

either by programmed automatics

or by remote control,"

Hilton decided, finally. "But

how did they drain all our

power? And just as bad, what

and how is that other point

source of power we're heading

for now?"

"What's wrong with it?"

Sawtelle asked.

"Its strength. No matter

what distance or reactant I

assume, nothing we know will

fit. Neither fission nor fusion

will do it. It has to be practically

total conversion!"

II

THE Perseus snapped out

of overdrive near the point

of interest and Hilton stared,

motionless and silent.

Space was full of madly

warring ships. Half of them

were bare, giant skeletons of

steel, like the "derelict" that

had so unexpectedly blasted

away from them. The others

were more or less like the

Perseus, except in being bigger,

faster and of vastly

greater power.

Beams of starkly incredible

power bit at and clung to

equally capable defensive

screens of pure force. As

these inconceivable forces

met, the glare of their neutralization

filled all nearby

space. And ships and skeletons

alike were disappearing

in chunks, blobs, gouts,

streamers and sparkles of

rended, fused and vaporized

metal.

Hilton watched two ships

combine against one skeleton.

Dozens of beams, incredibly

tight and hard, were held inexorably

upon dozens of

the bulges of the skeleton.

Overloaded, the bulges'

screens flared through the

spectrum and failed. And

bare metal, however refractory,

endures only for instants

under the appalling intensity

of such beams as

those.

The skeletons tried to duplicate

the ships' method of

attack, but failed. They were

too slow. Not slow, exactly,

either, but hesitant; as though

it required whole seconds for

the commander—or operator?

Or remote controller?—of

each skeleton to make it act.

The ships were winning.

"Hey!" Hilton yelped. "Oh—that's

the one we saw back

there. But what in all space

does it think it's doing?"

It was plunging at tremendous

speed straight through

the immense fleet of embattled

skeletons. It did not fire

a beam nor energize a screen;

it merely plunged along as

though on a plotted course

until it collided with one of

the skeletons of the fleet and

both structures plunged, a

tangled mass of wreckage, to

the ground of the planet below.

Then hundreds of the ships

shot forward, each to plunge

into and explode inside one of

the skeletons. When visibility

was restored another wave of

ships came forward to repeat

the performance, but there

was nothing left to fight.

Every surviving skeleton had

blinked out of normal space.

The remaining ships made

no effort to pursue the skeletons,

nor did they re-form as

a fleet. Each ship went off

by itself.

And on that distant planet

of the Stretts the group of

mechs watched with amazed

disbelief as light after light

after light winked out on

their two-miles-long control

board. Frantically they relayed

orders to the skeletons;

orders which did not affect

the losses.

"Brain-pans will blacken

for this ..." a mental snarl

began, to be interrupted by a

coldly imperious thought.

"That long-dead unit, so inexplicably

reactivated, is approaching

the fuel world. It

is ignoring the battle. It is

heading through our fleet toward

the Oman half ... handle

it, ten-eighteen!"

"It does not respond, Your

Loftiness."

"Then blast it, fool! Ah, it

is inactivated. As encyclopedist,

Nine, explain the

freakish behavior of that

unit."

"Yes, Your Loftiness. Many

cycles ago we sent a ship

against the Omans with a new

device of destruction. The

Omans must have intercepted

it, drained it of power and allowed

it to drift on. After all

these cycles of time it must

have come upon a small

source of power and of course

continued its mission."

"That can be the truth. The

Lords of the Universe must

be informed."

"The mining units, the carriers

and the refiners have

not been affected, Your Loftiness,"

a mech radiated.

"So I see, fool." Then, activating

another instrument,

His Loftiness thought at it,

in an entirely different vein,

"Lord Ynos, Madam? I have

to make a very grave report...."

IN the Perseus, four scientists

and three Navy officers

were arguing heatedly;

employing deep-space verbiage

not to be found in any

dictionary. "Jarve!" Karns

called out, and Hilton joined

the group. "Does anything

about this planet make any

sense to you?"

"No. But you're the planetographer.

'Smatter with it?"

"It's a good three hundred

degrees Kelvin too hot."

"Well, you know it's loaded

with uranexite."

"That much? The whole

crust practically jewelry

ore?"

"If that's what the figures

say, I'll buy it."

"Buy this, then. Continuous

daylight everywhere.

Noon June Sol-quality light

except that it's all in the visible.

Frank says it's from bombardment

of a layer of something,

and Frank admits that

the whole thing's impossible."

"When Frank makes up his

mind what 'something' is, I'll

take it as a datum."

"Third thing: there's only

one city on this continent,

and it's protected by a screen

that nobody ever heard of."

Hilton pondered, then

turned to the captain. "Will

you please run a search-pattern,

sir? Fine-toothing only

the hot spots?"

The planet was approximately

the same size as

Terra; its atmosphere, except

for its intense radiation, was

similar to Terra's. There were

two continents; one immense

girdling ocean. The temperature

of the land surface was

everywhere about 100°F, that

of the water about 90°F. Each

continent had one city, and

both were small. One was inhabited

by what looked like

human beings; the other by

usuform robots. The human

city was the only cool spot on

the entire planet; under its

protective dome the temperature

was 71°F.

Hilton decided to study the

robots first; and asked the

captain to take the ship down

to observation range. Sawtelle

objected; and continued

to object until Hilton started

to order his arrest. Then he

said, "I'll do it, under protest,

but I want it on record that I

am doing it against my best

judgment."

"It's on record," Hilton

said, coldly. "Everything said

and done is being, and will

continue to be, recorded."

The Perseus floated downward.

"There's what I want

most to see," Hilton said,

finally. "That big strip-mining

operation ... that's it ... hold

it!" Then, via throat-mike,

"Attention, all scientists!

You all know what to

do. Start doing it."

Sandra's blonde head was

very close to Hilton's brown

one as they both stared into

Hilton's plate. "Why, they

look like giant armadillos!"

she exclaimed.

"More like tanks," he disagreed,

"except that they've

got legs, wheels and treads—and

arms, cutters, diggers,

probes and conveyors—and

look at the way those buckets

dip solid rock!"

The fantastic machine was

moving very slowly along a

bench or shelf that it was

making for itself as it went

along. Below it, to its left,

dropped other benches being

made by other mining machines.

The machines were

not using explosives. Hard

though the ore was, the tools

were so much harder and

were driven with such tremendous

power that the stuff

might just have well have

been slightly-clayed sand.

Every bit of loosened ore,

down to the finest dust, was

forced into a conveyor and

thence into the armored body

of the machine. There it went

into a mechanism whose basic

principles Hilton could not

understand. From this monstrosity

emerged two streams

of product.

One of these, comprising

ninety-nine point nine plus

percent of the input, went out

through another conveyor

into the vast hold of a vehicle

which, when full and replaced

by a duplicate of itself, went

careening madly cross-country

to a dump.

The other product, a slow,

very small stream of tiny,

glistening black pellets, fell

into a one-gallon container

being held watchfully by a

small machine, more or less

like a three-wheeled motor

scooter, which was moving

carefully along beside the

giant miner. When this can

was almost full another scooter

rolled up and, without losing

a single pellet, took over

place and function. The first

scooter then covered its bucket,

clamped it solidly into a

recess designed for the purpose

and dashed away toward

the city.

Hilton stared slack-jawed

at Sandra. She stared back.

"Do you make anything of

that, Jarve?"

"Nothing. They're taking

pure uranexite and concentrating—or

converting—it a

thousand to one. I hope we'll

be able to do something about

it."

"I hope so, too, Chief; and

I'm sure we will."

"Well, that's enough for

now. You may take us up

now, Captain Sawtelle. And

Sandy, will you please call

all department heads and

their assistants into the conference

room?"

AT the head of the long

conference table, Hilton

studied his fourteen department

heads, all husky young

men, and their assistants, all

surprisingly attractive and

well-built young women. Bud

Carroll and Sylvia Bannister

of Sociology sat together. He

was almost as big as Karns;

she was a green-eyed redhead

whose five-ten and one-fifty

would have looked big except

for the arrangement thereof.

There were Bernadine and

Hermione van der Moen, the

leggy, breasty, platinum-blonde

twins—both of whom

were Cowper medalists in

physics. There was Etienne

de Vaux, the mathematical

wizard; and Rebecca Eisenstein,

the black-haired, flashing-eyed

ex-infant-prodigy

theoretical astronomer. There

was Beverly Bell, who made

mathematically impossible

chemical syntheses—who

swam channels for days on

end and computed planetary

orbits in her sleekly-coiffured

head.

"First, we'll have a get-together,"

Hilton said. "Nothing

recorded; just to get acquainted.

You all know that our

fourteen departments cover

science, from astronomy to

zoology."

He paused, again his eyes

swept the group. Stella Wing,

who would have been a grand-opera

star except for her

drive to know everything

about language. Theodora

(Teddy) Blake, who would

prove gleefully that she was

the world's best model—but

was in fact the most brilliantly

promising theoretician who

had ever lived.

"No other force like this

has ever been assembled,"

Hilton went on. "In more

ways than one. Sawtelle wanted

Jeffers to head this group,

instead of me. Everybody

thought he would head it."

"And Hilton wanted Eggleston

and got me," Sandra

said.

"That's right. And quite a

few of you didn't want to

come at all, but were told by

the Board to come or else."

The group stirred. Eyes

met eyes, and there were

smiles.

"I MYSELF think Jeffers

should have had the job.

I've never handled anything

half this big and I'll need a

lot of help. But I'm stuck

with it and you're all stuck

with me, so we'll all take it

and like it. You've noticed,

of course, the accent on

youth. The Navy crew is normal,

except for the commanders

being unusually young.

But we aren't. None of us is

thirty yet, and none of us has

ever been married. You fellows

look like a team of professional

athletes, and you

girls—well, if I didn't know

better I'd say the Board had

screened you for the front

row of the chorus instead of

for a top-bracket brain-gang.

How they found so many of

you I'll never know."

"Virile men and nubile

women!" Etienne de Vaux

leered enthusiastically. "Vive

le Board!"

"Nubile! Bravo, Tiny!

Quelle delicatesse de

nuance!"

"Three rousing cheers for

the Board!"

"Keep still, you nitwits!

Let me ask a question!" This

came from one of the twins.

"Before you give us the deduction,

Jarvis—or will it be

an intuition or an induction

or a ..."

"Or an inducement," the

other twin suggested, helpfully.

"Not that you would

need very much of that."

"You keep still, too, Miney.

I'm asking, Sir Moderator, if

I can give my deduction

first?"

"Sure, Bernadine; go

ahead."

"They figured we're going

to get completely lost. Then

we'll jettison the Navy, hunt

up a planet of our own and

start a race to end all human

races. Or would you call this

a see-duction instead of a dee-duction?"

This produced a storm of

whistles, cheers and jeers

that it took several seconds

to quell.

"But seriously, Jarvis,"

Bernadine went on. "We've

all been wondering and it

doesn't make sense. Have you

any idea at all of what the

Board actually did have in

mind?"

"I believe that the Board

selected for mental, not physical,

qualities; for the ability

to handle anything unexpected

or unusual that comes up,

no matter what it is."

"You think it wasn't double-barreled?"

asked Kincaid,

the psychologist. He smiled

quizzically. "That all this virility

and nubility and glamor

is pure coincidence?"

"No," Hilton said, with an

almost imperceptible flick of

an eyelid. "Coincidence is as

meaningless as paradox. I

think they found out that—barring

freaks—the best

minds are in the best bodies."

"Could be. The idea has

been propounded before."

"Now let's get to work."

Hilton flipped the switch of

the recorder. "Starting with

you, Sandy, each of you give

a two-minute boil-down. What

you found and what you

think."

SOMETHING over an hour

later the meeting adjourned

and Hilton and Sandra

strolled toward the control

room.

"I don't know whether you

convinced Alexander Q. Kincaid

or not, but you didn't

quite convince me," Sandra

said.

"Nor him, either."

"Oh?" Sandra's eyebrows

"No. He grabbed the out I

offered him. I didn't fool

Teddy Blake or Temple Bells,

either. You four are all,

though, I think."

"Temple? You think she's

so smart?"

"I don't think so, no. Don't

fool yourself, chick. Temple

Bells looks and acts sweet

and innocent and virginal.

Maybe—probably—she is. But

she isn't showing a fraction of

the stuff she's really got.

She's heavy artillery, Sandy.

And I mean heavy."

"I think you're slightly

nuts there. But do you really

believe that the Board was

playing Cupid?"

"Not trying, but doing.

Cold-bloodedly and efficiently.

Yes."

"But it wouldn't work! We

aren't going to get lost!"

"We won't need to. Propinquity

will do the work."

"Phooie. You and me, for

instance?" She stopped, put

both hands on her hips, and

glared. "Why, I wouldn't

marry you if you ..."

"I'll tell the cockeyed world

you won't!" Hilton broke in.

"Me marry a damned female

Ph.D.? Uh-uh. Mine will be

a cuddly little brunette that

thinks a slipstick is some kind

of lipstick and that an isotope's

something good to eat."

"One like that copy of

Murchison's Dark Lady that

you keep under the glass on

your desk?" she sneered.

"Exactly...." He started to

continue the battle, then shut

himself off. "But listen, Sandy,

why should we get into

a fight because we don't want

to marry each other? You're

doing a swell job. I admire

you tremendously for it and

I like to work with you."

"You've got a point there,

Jarve, at that, and I'm one of

the few who know what kind

of a job you're doing, so I'll

relax." She flashed him a

gamin grin and they went on

into the control room.

It was too late in the day

then to do any more exploring;

but the next morning,

early, the Perseus lined out

for the city of the humanoids.

Tula turned toward her fellows.

Her eyes filled with a

happily triumphant light and

her thought a lilting song. "I

have been telling you from

the first touch that it was the

Masters. It is the Masters!

The Masters are returning to

us Omans and their own home

world!"

"CAPTAIN Sawtelle," Hilton

said, "Please land

in the cradle below."

"Land!" Sawtelle stormed.

"On a planet like that? Not

by ..." He broke off and

stared; for now, on that cradle,

there flamed out in

screaming red the Perseus'

own Navy-coded landing symbols!

"Your protest is recorded,"

Hilton said. "Now, sir, land."

Fuming, Sawtelle landed.

Sandra looked pointedly at

Hilton. "First contact is my

dish, you know."

"Not that I like it, but it

is." He turned to a burly

youth with sun-bleached,

crew-cut hair, "Still safe,

Frank?"

"Still abnormally low. Surprising

no end, since all the

rest of the planet is hotter

than the middle tail-race of

hell."

"Okay, Sandy. Who will

you want besides the top linguists?"

"Psych—both Alex and

Temple. And Teddy Blake.

They're over there. Tell them,

will you, while I buzz Teddy?"

"Will do," and Hilton

stepped over to the two psychologists

and told them.

Then, "I hope I'm not leading

with my chin, Temple, but is

that your real first name or

a professional?"

"It's real; it really is. My

parents were romantics: dad

says they considered both

'Golden' and 'Silver'!"

Not at all obviously, he

studied her: the almost translucent,

unblemished perfection

of her lightly-tanned,

old-ivory skin; the clear,

calm, deep blueness of her

eyes; the long, thick mane of

hair exactly the color of a

field of dead-ripe wheat.

"You know, I like it," he

said then. "It fits you."

"I'm glad you said that,

Doctor...."

"Not that, Temple. I'm not

going to 'Doctor' you."

"I'll call you 'boss', then,

like Stella does. Anyway, that

lets me tell you that I like

it myself. I really think that

it did something for me."

"Something did something

for you, that's for sure. I'm

mighty glad you're aboard,

and I hope ... here they come.

Hi, Hark! Hi, Stella!"

"Hi, Jarve," said Chief

Linguist Harkins, and:

"Hi, boss—what's holding

us up?" asked his assistant,

Stella Wing. She was about

five feet four. Her eyes were

a tawny brown; her hair a

flamboyant auburn mop. Perhaps

it owed a little of its

spectacular refulgence to

chemistry, Hilton thought,

but not too much. "Let us

away! Let the lions roar and

let the welkin ring!"

"Who's been feeding you

so much red meat, little

squirt?" Hilton laughed and

turned away, meeting Sandra

in the corridor. "Okay, chick,

take 'em away. We'll cover

you. Luck, girl."

And in the control room,

to Sawtelle, "Needle-beam

cover, please; set for minimum

aperture and lethal

blast. But no firing, Captain

Sawtelle, until I give the order."

THE Perseus was surrounded

by hundreds of natives.

They were all adult, all naked

and about equally divided

as to sex. They were friendly;

most enthusiastically so.

"Jarve!" Sandra squealed.

"They're telepathic. Very

strongly so! I never imagined—I

never felt anything like

it!"

"Any rough stuff?" Hilton

demanded.

"Oh, no. Just the opposite.

They love us ... in a way that's

simply indescribable. I don't

like this telepathy business ...

not clear ... foggy, diffuse ... this

woman is sure I'm her

long-lost great-great-a-hundred-times

grandmother or

something—You! Slow down.

Take it easy! They want us

all to come out here and live

with ... no, not with them, but

each of us alone in a whole

house with them to wait on

us! But first, they all want

to come aboard...."

"What?" Hilton yelped.

"But are you sure they're

friendly?"

"Positive, chief."

"How about you, Alex?"

"We're all sure, Jarve. No

question about it."

"Bring two of them aboard.

A man and a woman."

"You won't bring any!"

Sawtelle thundered. "Hilton,

I had enough of your stupid,

starry-eyed, ivory-domed

blundering long ago, but this

utterly idiotic brainstorm of

letting enemy aliens aboard

us ends all civilian command.

Call your people back aboard

or I will bring them in by

force!"

"Very well, sir. Sandy, tell

the natives that a slight delay

has become necessary and

bring your party aboard."

The Navy officers smiled—or

grinned—gloatingly; while

the scientists stared at their

director with expressions

ranging from surprise to disappointment

and disgust.

Hilton's face remained set, expressionless,

until Sandra and

her party had arrived.

"Captain Sawtelle," he said

then, "I thought that you and

I had settled in private the

question or who is in command

of Project Theta Orionis

at destination. We will

now settle it in public. Your

opinion of me is now on record,

witnessed by your officers

and by my staff. My

opinion of you, which is now

being similarly recorded and

witnessed, is that you are a

hidebound, mentally ossified

Navy mule; mentally and psychologically

unfit to have any

voice in any such mission as

this. You will now agree on

this recording and before

these witnesses, to obey my

orders unquestioningly or I

will now unload all Bureau of

Science personnel and equipment

onto this planet and

send you and the Perseus

back to Terra with the doubly-sealed

record of this episode

posted to the Advisory

Board. Take your choice."

Eyes locked, and under

Hilton's uncompromising

stare Sawtelle weakened. He

fidgeted; tried three times—unsuccessfully—to

blare defiance.

Then, "Very well sir,"

he said, and saluted.

"THANK you, sir," Hilton

said, then turned to his

staff. "Okay, Sandy, go

ahead."

Outside the control room

door, "Thank God you don't

play poker, Jarve!" Karns

gasped. "We'd all owe you all

the pay we'll ever get!"

"You think it was the bluff,

yes?" de Vaux asked. "Me, I

think no. Name of a name of

a name! I was wondering with

unease what life would be like

on this so-alien planet!"

"You didn't need to wonder,

Tiny," Hilton assured

him. "It was in the bag. He's

incapable of abandonment."

Beverly Bell, the van der

Moen twins and Temple Bells

all stared at Hilton in awe;

and Sandra felt much the

same way.

"But suppose he had called

you?" Sandra demanded.

"Speculating on the impossible

is unprofitable," he said.

"Oh, you're the most exasperating

thing!" Sandra

stamped a foot. "Don't you—ever—answer

a question intelligibly?"

"When the question is

meaningless, chick, I can't."

At the lock Temple Bells,

who had been hanging back,

cocked an eyebrow at Hilton

and he made his way to her

side.

"What was it you started to

say back there, boss?"

"Oh, yes. That we should

see each other oftener."

"That's what I was hoping

you were going to say." She

put her hand under his elbow

and pressed his arm lightly,

fleetingly, against her side.

"That would be indubitably

the fondest thing I could be

of."

He laughed and gave her

arm a friendly squeeze. Then

he studied her again, the most

baffling member of his staff.

About five feet six. Lithe,

hard, trained down fine—as a

tennis champion, she would

be. Stacked—how she was

stacked! Not as beautiful as

Sandra or Teddy ... but with

an ungodly lot of something

that neither of them had ... nor

any other woman he had

ever known.

"Yes, I am a little difficult

to classify," she said quietly,

almost reading his mind.

"That's the understatement

of the year! But I'm making

some progress."

"Such as?" This was an

open challenge.

"Except possibly Teddy,

the best brain aboard."

"That isn't true, but go

ahead."

"You're a powerhouse. A

tightly organized, thoroughly

integrated, smoothly functioning,

beautifully camouflaged

Juggernaut. A reasonable

facsimile of an irresistible

force."

"My God, Jarvis!" That

had gone deep.

"Let me finish my analysis.

You aren't head of your department

because you don't

want to be. You fooled the

top psychs of the Board.

You've been running ninety

per cent submerged because

you can work better that way

and there's no glory-hound

blood in you."

She stared at him, licking

her lips. "I knew your mind

was a razor, but I didn't know

it was a diamond drill, too.

That seals your doom, boss,

unless ... no, you can't possibly

know why I'm here."

"Why, of course I do."

"You just think you do.

You see, I've been in love

with you ever since, as a gangling,

bony, knobby-kneed

kid, I listened to your first

doctorate disputation. Ever

since then, my purpose in life

has been to land you."

III

"BUT listen!" he exclaimed.

"I can't, even

if I want...."

"Of course you can't." Pure

deviltry danced in her eyes.

"You're the Director. It

wouldn't be proper. But it's

Standard Operating Procedure

for simple, innocent, unsophisticated

little country

girls like me to go completely

overboard for the boss."

"But you can't—you

mustn't!" he protested in

panic.

Temple Bells was getting

plenty of revenge for the

shocks he had given her. "I

can't? Watch me!" She

grinned up at him, her eyes

still dancing. "Every chance

I get, I'm going to hug your

arm like I did a minute ago.

And you'll take hold of my

forearm, like you did! That

can be taken, you see, as either:

One, a reluctant acceptance

of a mildly distasteful

but not quite actionable

situation, or: Two, a blocking

move to keep me from climbing

up you like a squirrel!"

"Confound it, Temple, you

can't be serious!"

"Can't I?" She laughed

gleefully. "Especially with

half a dozen of those other

cats watching? Just wait and

see, boss!"

Sandra and her two guests

came aboard. The natives

looked around; the man at

the various human men, the

woman at each of the human

women. The woman remained

beside Sandra; the man took

his place at Hilton's left,

looking up—he was a couple

of inches shorter than Hilton's

six feet one—with an

air of ... of expectancy!

"Why this arrangement,

Sandy?" Hilton asked.

"Because we're tops. It's

your move, Jarve. What's

first?"

"Uranexite. Come along,

Sport. I'll call you that until ..."

"Laro," the native said, in

a deep resonant bass voice.

He hit himself a blow on the

head that would have floored

any two ordinary men.

"Sora," he announced, striking

the alien woman a similar

blow.

"Laro and Sora, I would

like to have you look at our

uranexite, with the idea of refueling

our ship. Come with

me, please?"

Both nodded and followed

him. In the engine room he

pointed at the engines, then

to the lead-blocked labyrinth

leading to the fuel holds.

"Laro, do you understand

'hot'? Radioactive?"

Laro nodded—and started

to open the heavy lead door!

"Hey!" Hilton yelped.

"That's hot!" He seized

Laro's arm to pull him away—and

got the shock of his

life. Laro weighed at least

five hundred pounds! And

the guy still looked human!

Laro nodded again and

gave himself a terrific thump

on the chest. Then he glanced

at Sora, who stepped away

from Sandra. He then went

into the hold and came out

with two fuel pellets in his

hand, one of which he tossed

to Sora. That is, the motion

looked like a toss, but the

pellet traveled like a bullet.

Sora caught it unconcernedly

and both natives flipped the

pellets into their mouths.

There was a half minute of

rock-crusher crunching; then

both natives opened their

mouths.

The pellets had been pulverized

and swallowed.

Hilton's voice rang out.

"Poynter! How can these

people be non-radioactive after

eating a whole fuel pellet

apiece?"

Poynter tested both natives

again. "Cold," he reported.

"Stone cold. No background

even. Play that on your harmonica!"

LARO nodded, perfectly

matter-of-factly, and in

Hilton's mind there formed a

picture. It was not clear, but

it showed plainly enough a

long line of aliens approaching

the Perseus. Each carried

on his or her shoulder a lead

container holding two hundred

pounds of Navy Regulation

fuel pellets. A standard

loading-tube was sealed into

place and every fuel-hold was

filled.

This picture, Laro indicated

plainly, could become reality

any time.

Sawtelle was notified and

came on the run. "No fuel is

coming aboard without being

tested!" he roared.

"Of course not. But it'll

pass, for all the tea in China.

You haven't had a ten per

cent load of fuel since you

were launched. You can fill

up or not—the fuel's here—just

as you say."

"If they can make Navy

standard, of course we want

it."

The fuel arrived. Every

load tested well above standard.

Every fuel hold was

filled to capacity, with no

leakage and no emanation.

The natives who had handled

the stuff did not go away, but

gathered in the engine-room;

and more and more humans

trickled in to see what was

going on.

Sawtelle stiffened. "What's

going on over there, Hilton?"

"I don't know; but let's let

'em go for a minute. I want

to learn about these people

and they've got me stopped

cold."

"You aren't the only one.

But if they wreck that Mayfield

it'll cost you over twenty

thousand dollars."

"Okay." The captain and director

watched, wide eyed.

Two master mechanics had

been getting ready to re-fit a

tube—a job requiring both

strength and skill. The tube

was very heavy and made of

superefract. The machine—the

Mayfield—upon which

the work was to be done, was

extremely complex.

Two of the aliens had

brushed the mechanics—very

gently—aside and were doing

their work for them. Ignoring

the hoist, one native had

picked the tube up and was

holding it exactly in place on

the Mayfield. The other,

hands moving faster than the

eye could follow, was locking

it—micrometrically precise

and immovably secure—into

place.

"How about this?" one of

the mechanics asked of his

immediate superior. "If we

throw 'em out, how do we do

it?"

By a jerk of the head, the

non-com passed the buck to a

commissioned officer, who

relayed it up the line to Sawtelle,

who said, "Hilton, nobody

can run a Mayfield

without months of training.

They'll wreck it and it'll cost

you ... but I'm getting curious

myself. Enough so to take

half the damage. Let 'em go

ahead."

"How about this, Mike?"

one of the machinists asked

of his fellow. "I'm going to

like this, what?"

"Ya-as, my deah Chumley,"

the other drawled, affectedly.

"My man relieves me of so

much uncouth effort."

The natives had kept on

working. The Mayfield was

running. It had always

howled and screamed at its

work, but now it gave out

only a smooth and even hum.

The aliens had adjusted it

with unhuman precision;

they were one with it as no

human being could possibly

be. And every mind present

knew that those aliens were,

at long, long last, fulfilling

their destiny and were, in

that fulfillment, supremely

happy. After tens of thousands

of cycles of time they

were doing a job for their

adored, their revered and

beloved MASTERS.

That was a stunning shock;

but it was eclipsed by another.

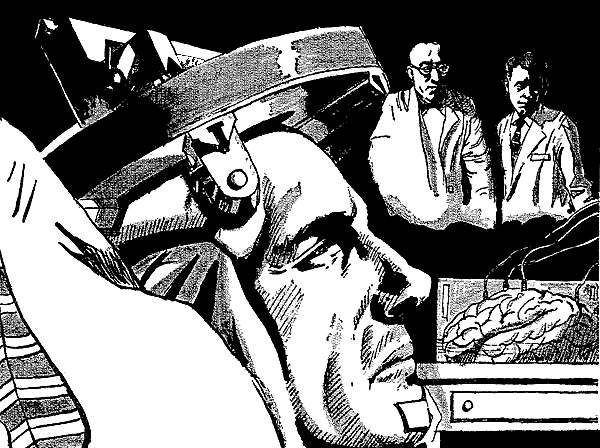

"I AM sorry, Master Hilton,"

Laro's tremendous

bass voice boomed out, "that

it has taken us so long to

learn your Masters' language

as it now is. Since you left

us you have changed it radically;

while we, of course,

have not changed it at all."

"I'm sorry, but you're mistaken,"

Hilton said. "We are

merely visitors. We have never

been here before; nor, as

far as we know, were any of

our ancestors ever here."

"You need not test us, Master.

We have kept your trust.

Everything has been kept,

changelessly the same, awaiting

your return as you ordered

so long ago."

"Can you read my mind?"

Hilton demanded.

"Of course; but Omans can

not read in Masters' minds

anything except what Masters

want Omans to read."

"Omans?" Harkins asked.

"Where did you Omans and

your masters come from?

Originally?"

"As you know, Master, the

Masters came originally from

Arth. They populated Ardu,

where we Omans were developed.

When the Stretts drove

us from Ardu, we all came to

Ardry, which was your home

world until you left it in our

care. We keep also this, your

half of the Fuel World, in

trust for you."

"Listen, Jarve!" Harkins

said, tensely. "Oman-human.

Arth-Earth. Ardu-Earth Two.

Ardry-Earth Three. You

can't laugh them off ... but

there never was an Atlantis!"

"This is getting no better

fast. We need a full staff

meeting. You, too, Sawtelle,

and your best man. We need

all the brains the Perseus can

muster."

"You're right. But first, get

those naked women out of

here. It's bad enough, having

women aboard at all, but

this ... my men are spacemen,

mister."

Laro spoke up. "If it is the

Masters' pleasure to keep on

testing us, so be it. We have

forgotten nothing. A dwelling

awaits each Master, in

which each will be served by

Omans who will know the

Master's desires without being

told. Every desire. While

we Omans have no biological

urges, we are of course highly

skilled in relieving tensions

and derive as much

pleasure from that service as

from any other."

Sawtelle broke the silence

that followed. "Well, for the

men—" He hesitated. "Especially

on the ground ... well,

talking in mixed company,

you know, but I think ..."

"Think nothing of the

mixed company, Captain Sawtelle,"

Sandra said. "We women

are scientists, not shrinking

violets. We are accustomed

to discussing the facts

of life just as frankly as any

other facts."

Sawtelle jerked a thumb at

Hilton, who followed him out

into the corridor. "I have

been a Navy mule," he said.

"I admit now that I'm out-maneuvered,

out-manned, and

out-gunned."

"I'm just as baffled—at

present—as you are, sir. But

my training has been aimed

specifically at the unexpected,

while yours has not."

"That's letting me down

easy, Jarve." Sawtelle smiled—the

first time the startled

Hilton had known that the

hard, tough old spacehound

could smile. "What I wanted

to say is, lead on. I'll follow

you through force-field and

space-warps."

"Thanks, skipper. And by

the way, I erased that record

yesterday." The two gripped

hands; and there came into

being a relationship that was

to become a lifelong friendship.

"WE will start for Ardry

immediately," Hilton

said. "How do we make that

jump without charts, Laro?"

"Very easily, Master. Kedo,

as Master Captain Sawtelle's

Oman, will give the orders.

Nito will serve Master Snowden

and supply the knowledge

he says he has forgotten."

"Okay. We'll go up to the

control room and get started."

And in the control room,

Kedo's voice rasped into the

captain's microphone. "Attention,

all personnel! Master

Captain Sawtelle orders take-off

in two minutes. The

countdown will begin at five

seconds.... Five! Four! Three!

Two! One! Lift!"

Nito, not Snowden, handled

the controls. As perfectly as

the human pilot had ever done

it, at the top of his finest

form, he picked the immense

spaceship up and slipped it

silkily into subspace.

"Well, I'll be a ..." Snowden

gasped. "That's a better

job than I ever did!"

"Not at all, Master, as you

know," Nito said. "It was you

who did this. I merely performed

the labor."

A few minutes later, in the

main lounge, Navy and BuSci

personnel were mingling as

they had never done before.

Whatever had caused this relaxation

of tension—the

friendship of captain and director?

The position in which

they all were? Or what?—they

all began to get acquainted

with each other.

"Silence, please, and be

seated," Hilton said. "While

this is not exactly a formal

meeting, it will be recorded

for future reference. First, I

will ask Laro a question.

Were books or records left

on Ardry by the race you call

the Masters?"

"You know there are, Master.

They are exactly as you

left them. Undisturbed for

over two hundred seventy-one

thousand years."

"Therefore we will not

question the Omans. We do

not know what questions to

ask. We have seen many

things hitherto thought impossible.

Hence, we must discard

all preconceived opinions

which conflict with facts. I

will mention a few of the

problems we face."

"The Omans. The Masters.

The upgrading of the armament

of the Perseus to Oman

standards. The concentration

of uranexite. What is that

concentrate? How is it used?

Total conversion—how is it

accomplished? The skeletons—what

are they and how are

they controlled? Their ability

to drain power. Who or what

is back of them? Why a deadlock

that has lasted over a

quarter of a million years?

How much danger are we and

the Perseus actually in? How

much danger is Terra in, because

of our presence here?

There are many other questions."

"Sandra and I will not take

part. Nor will three others;

de Vaux, Eisenstein, and

Blake. You have more important

work to do."

"What can that be?" asked

Rebecca. "Of what possible

use can a mathematician, a

theoretician and a theoretical

astronomer be in such a situation

as this?"

"You can think powerfully

in abstract terms, unhampered

by Terran facts and laws

which we now know are neither

facts nor laws. I cannot

even categorize the problems

we face. Perhaps you three

will be able to. You will listen,

then consult, then tell me

how to pick the teams to do

the work. A more important

job for you is this: Any problem,

to be solved, must be

stated clearly; and we don't

know even what our basic

problem is. I want something

by the use of which I can

break this thing open. Get it

for me."

REBECCA and de Vaux

merely smiled and nodded,

but Teddy Blake said

happily, "I was beginning to

feel like a fifth wheel on this

project, but that's something

I can really stick my teeth

into."

"Huh? How?" Karns demanded.

"He didn't give you

one single thing to go on;

just compounded the confusion."

Hilton spoke before Teddy

could. "That's their dish,

Bill. If I had any data I'd

work it myself. You first,

Captain Sawtelle."

That conference was a very

long one indeed. There were

almost as many conclusions

and recommendations as there

were speakers. And through

it all Hilton and Sandra listened.

They weighed and tested

and analyzed and made

copious notes; in shorthand

and in the more esoteric

characters of symbolic logic.

And at its end:

"I'm just about pooped,

Sandy. How about you?"

"You and me both, boss. See

you in the morning."

But she didn't. It was four

o'clock in the afternoon when

they met again.

"We made up one of the

teams, Sandy," he said, with

surprising diffidence. "I

know we were going to do it

together, but I got a hunch

on the first team. A kind of

a weirdie, but the brains

checked me on it." He placed

a card on her desk. "Don't

blow your top until after I

you've studied it."

"Why, I won't, of

course...." Her voice died

away. "Maybe you'd better

cancel that 'of course'...."

She studied, and when she

spoke again she was exerting

self-control. "A chemist, a

planetographer, a theoretician,

two sociologists, a psychologist

and a radiationist.

And six of the seven are three

pairs of sweeties. What kind

of a line-up is that to solve

a problem in physics?"

"It isn't in any physics we

know. I said think!"

"Oh," she said, then again

"Oh," and "Oh," and "Oh."

Four entirely different tones.

"I see ... maybe. You're matching

minds, not specialties;

and supplementing?"

"I knew you were smart.

Buy it?"

"It's weird, all right, but

I'll buy it—for a trial run,

anyway. But I'd hate like sin

to have to sell any part of it

to the Board.... But of course

we're—I mean you're responsible

only to yourself."

"Keep it 'we', Sandy. You're

as important to this project

as I am. But before we tackle

the second team, what's your

thought on Bernadine and

Hermione? Separate or together?"

"Separate, I'd say. They're

identical physically, and so

nearly so mentally that

of them would be just as good

on a team as both of them.

More and better work on different

teams."

"My thought exactly." And

so it went, hour after hour.

The teams were selected

and meetings were held.

THE Perseus reached Ardry,

which was very much

like Terra. There were continents,

oceans, ice-caps,

lakes, rivers, mountains and

plains, forests and prairies.

The ship landed on the spacefield

of Omlu, the City of the

Masters, and Sawtelle called

Hilton into his cabin. The

Omans Laro and Kedo went

along, of course.

"Nobody knows how it

leaked ..." Sawtelle began.

"No secrets around here,"

Hilton grinned. "Omans, you

know."

"I suppose so. Anyway, every

man aboard is all hyped

up about living aground—especially

with a harem. But before

I grant liberty, suppose

there's any VD around here

that our prophylactics can't

handle?"

"As you know, Masters,"

Laro replied for Hilton before

the latter could open his

mouth, "no disease, venereal

or other, is allowed to exist

on Ardry. No prophylaxis is

either necessary or desirable."

"That ought to hold you

for a while, Skipper." Hilton

smiled at the flabbergasted

captain and went back to the

lounge.

"Everybody going ashore?"

he asked.

"Yes." Karns said. "Unanimous

vote for the first time."

"Who wouldn't?" Sandra

asked. "I'm fed up with living

like a sardine. I will scream

for joy the minute I get into

a real room."

"Cars" were waiting, in a

stopping-and-starting line.

Three-wheel jobs. All were

empty. No drivers, no steering-wheels,

no instruments or

push-buttons. When the

whole line moved ahead as

one vehicle there was no

noise, no gas, no blast.

An Oman helped a Master

carefully into the rear seat

of his car, leaped into the

front seat and the car sped

quietly away. The whole line

of empty cars, acting in perfect

synchronization, shot

forward one space and

stopped.

"This is your car, Master,"

Laro said, and made a production

out of getting Hilton

into the vehicle undamaged.

Hilton's plan had been

beautifully simple. All the

teams were to meet at the

Hall of Records. The linguists

and their Omans would

study the records and pass

them out. Specialty after

specialty would be unveiled

and teams would work on

them. He and Sandy would

sit in the office and analyze

and synthesize and correlate.

It was a very nice plan.

It was a very nice office,

too. It contained every item

of equipment that either Sandra

or Hilton had ever

worked with—it was a big office—and

a great many that

neither of them had ever

heard of. It had a full staff of

Omans, all eager to work.

Hilton and Sandra sat in

that magnificent office for

three hours, and no reports

came in. Nothing happened at

all.

"This gives me the howling

howpers!" Hilton growled.

"Why haven't I got brains

enough to be on one of those

teams?"

"I could shed a tear for

you, you big dope, but I

won't," Sandra retorted.

"What do you want to be, besides

the brain and the kingpin

and the balance-wheel

and the spark-plug of the outfit?

Do you want to do

everything yourself?"

"Well, I don't want to go

completely nuts, and that's

all I'm doing at the moment!"

The argument might have become

acrimonious, but it was

interrupted by a call from

Karns.

"Can you come out here,

Jarve? We've struck a knot."

"'Smatter? Trouble with

the Omans?" Hilton snapped.

"Not exactly. Just non-cooperation—squared.

We can't even get started. I'd like to

have you two come out here

and see if you can do anything.

I'm not trying rough

stuff, because I know it

wouldn't work."

"Coming up, Bill," and

Hilton and Sandra, followed

by Laro and Sora, dashed out

to their cars.

THE Hall of Records was

a long, wide, low, windowless,

very massive structure,

built of a metal that looked

like stainless steel. Kept

highly polished, the vast expanse

of seamless and jointless

metal was mirror-bright.

The one great door was open,

and just inside it were the

scientists and their Omans.

"Brief me, Bill," Hilton

said.

"No lights. They won't turn

'em on and we can't. Can't

find either lights or any possible

kind of switches."

"Turn on the lights, Laro,"

Hilton said.

"You know that I cannot

do that, Master. It is forbidden

for any Oman to have

anything to do with the illumination

of this solemn and

revered place."

"Then show me how to do

it."

"That would be just as bad,

Master," the Oman said

proudly. "I will not fail any

test you can devise!"

"Okay. All you Omans go

back to the ship and bring

over fifteen or twenty lights—the

tripod jobs. Scat!"

They "scatted" and Hilton

went on, "No use asking

questions if you don't know

what questions to ask. Let's

see if we can cook up something.

Lane—Kathy—what

has Biology got to say?"

Dr. Lane Saunders and Dr.

Kathryn Cook—the latter a

willowy brown-eyed blonde—conferred

briefly. Then Saunders

spoke, running both

hands through his unruly

shock of fiery red hair. "So

far, the best we can do is a

more-or-less educated guess.

They're atomic-powered, total-conversion

androids.

Their pseudo-flesh is composed

mainly of silicon and

fluorine. We don't know the

formula yet, but it is as much

more stable than our teflon

as teflon is than corn-meal

mush. As to the brains, no

data. Bones are super-stainless

steel. Teeth, harder than

diamond, but won't break.

Food, uranexite or its concentrated

derivative, interchangeably.

Storage reserve,

indefinite. Laro and Sora

won't have to eat again for

at least twenty-five years...."

The group gasped as one,

but Saunders went on: "They

can eat and drink and breathe

and so on, but only because

the original Masters wanted

them to. Non-functional.

Skins and subcutaneous layers

are soft, for the same reason.

That's about it, up to

now."

"Thanks, Lane. Hark, is it

reasonable to believe that any

culture whatever could run

for a quarter of a million

years without changing one

word of its language or one

iota of its behavior?"

"Reasonable or not, it seems

to have happened."

"Now for Psychology.

Alex?"

"It seems starkly incredible,

but it seems to be true.

If it is, their minds were subjected

to a conditioning no

Terran has ever imagined—an

unyielding fixation."

"They can't be swayed,

then, by reason or logic?"

Hilton paused invitingly.

"Or anything else," Kincaid

said, flatly. "If we're

right they can't be swayed,

period."

"I was afraid of that. Well,

that's all the questions I

know how to ask. Any contributions

to this symposium?"

AFTER a short silence de

Vaux said, "I suppose

you realize that the first half

of the problem you posed us

has now solved itself?"

"Why, no. No, you're 'way

ahead of me."

"There is a basic problem

and it can now be clearly

stated," Rebecca said. "Problem:

To determine a method

of securing full cooperation

from the Omans. The first

step in the solution of this

problem is to find the most

appropriate operator. Teddy?"

"I have an operator—of

sorts," Theodora said. "I've

been hoping one of us could

find a better."

"What is it?" Hilton demanded.

"The word 'until'."

"Teddy, you're a sweetheart!"

Hilton exclaimed.

"How can 'until' be a mathematical

operator?" Sandra

asked.

"Easily." Hilton was already

deep in thought. "This

hard conditioning was to last

only until the Masters returned.

Then they'd break it.

So all we have to do is figure

out how a Master would do

it."

"That's all," Kincaid said,

meaningly.

Hilton pondered. Then,

"Listen, all of you. I may

have to try a colossal job of

bluffing...."

"Just what would you call

'colossal' after what you did

to the Navy?" Karns asked.

"That was a sure thing.

This isn't. You see, to find out

whether Laro is really an immovable

object, I've got to

make like an irresistible

force, which I ain't. I don't

know what I'm going to do;

I'll have to roll it as I go

along. So all of you keep on

your toes and back any play

I make. Here they come."

The Omans came in and

Hilton faced Laro, eyes to

eyes. "Laro," he said, "you refused

to obey my direct order.

Your reasoning seems to

be that, whether the Masters

wish it or not, you Omans

will block any changes whatever

in the status quo

throughout all time to come.

In other words, you deny the

fact that Masters are in fact

your Masters."

"But that is not exactly it,

Master. The Masters ..."

"That is it. Exactly it.

Either you are the Master

here or you are not. That is

a point to which your two-value

logic can be strictly applied.

You are wilfully neglecting

the word 'until'. This

stasis was to exist only until

the Masters returned. Are we

Masters? Have we returned?

Note well: Upon that one

word 'until' may depend the

length of time your Oman

race will continue to exist."

The Omans flinched; the

humans gasped.

"But more of that later,"

Hilton went on, unmoved.

"Your ancient Masters, being

short-lived like us, changed

materially with time, did they

not? And you changed with

them?"

"But we did not change

ourselves, Master. The Masters ..."

"You did change yourselves.

The Masters changed

only the prototype brain.

They ordered you to change

yourselves and you obeyed

their orders. We order you to

change and you refuse to

obey our orders. We have

changed greatly from our ancestors.

Right?"

"That is right, Master."

"We are stronger physically,

more alert and more vigorous

mentally, with a keener,

sharper outlook on life?"

"You are, Master."

"THAT is because our ancestors

decided to do

without Omans. We do our

own work and enjoy it. Your

Masters died of futility and

boredom. What I would like

to do, Laro, is take you to the

creche and put your disobedient

brain back into the

matrix. However, the decision

is not mine alone to make.

How about it, fellows and

girls? Would you rather have

alleged servants who won't do

anything you tell them to or

no servants at all?"

"As semantician, I protest!"

Sandra backed his play.

"That is the most viciously

loaded question I ever heard—it

can't be answered except

in the wrong way!"

"Okay, I'll make it semantically

sound. I think we'd

better scrap this whole Oman

race and start over and I

want a vote that way!"

"You won't get it!" and

everybody began to yell.

Hilton restored order and

swung on Laro, his attitude

stiff, hostile and reserved.

"Since it is clear that no

unanimous decision is to be

expected at this time I will

take no action at this time.

Think over, very carefully,

what I have said, for as far

as I am concerned, this world

has no place for Omans who

will not obey orders. As soon

as I convince my staff of the

fact, I shall act as follows: I

shall give you an order and if

you do not obey it blast your

head to a cinder. I shall then

give the same order to another

Oman and blast him.

This process will continue

until: First, I find an obedient

Oman. Second, I run out

of blasters. Third, the planet

runs out of Omans. Now take

these lights into the first

room of records—that one

over there." He pointed, and

no Oman, and only four humans,

realized that he had

made the Omans telegraph

their destination so that he

could point it out to them!

Inside the room Hilton

asked caustically of Laro:

"The Masters didn't lift those

heavy chests down themselves,

did they?"

"Oh, no, Master, we did

that."

"Do it, then. Number One

first ... yes, that one ... open

it and start playing the records

in order."

The records were not tapes

or flats or reels, but were

spools of intricately-braided

wire. The players were projectors

of full-color, hi-fi

sound, tri-di pictures.

Hilton canceled all moves

aground and issued orders

that no Oman was to be allowed

aboard ship, then

looked and listened with his

staff.

The first chest contained

only introductory and elementary

stuff; but it was so

interesting that the humans

stayed overtime to finish it.

Then they went back to the

ship; and in the main lounge

Hilton practically collapsed

onto a davenport. He took out

a cigarette and stared in surprise

at his hand, which was

shaking.

"I think I could use a

drink," he remarked.

"What, before supper?"

Karns marveled. Then, "Hey,

Wally! Rush a flagon of

avignognac—Arnaud Freres—for

the boss and everything

else for the rest of us. Chop-chop

but quick!"

A hectic half-hour followed.

Then, "Okay, boys and

girls, I love you, too, but let's

cut out the slurp and sloosh,

get some supper and log us

some sack time. I'm just about

pooped. Sorry I had to queer

the private-residence deal,

Sandy, you poor little sardine.

But you know how it

is."

Sandra grimaced. "Uh-huh.

I can take it a while longer

if you can."

AFTER breakfast next

morning, the staff met in

the lounge. As usual, Hilton

and Sandra were the first to

arrive.

"Hi, boss," she greeted him.

"How do you feel?"

"Fine. I could whip a wildcat

and give her the first two

scratches. I was a bit beat up

last night, though."

"I'll say ... but what I simply

can't get over is the way

you underplayed the climax.

'Third, the planet runs out of

Omans'. Just like that—no

emphasis at all. Wow! It had

the impact of a delayed-action

atomic bomb. It put

goose-bumps all over me. But

just s'pose they'd missed it?"

"No fear. They're smart. I

had to play it as though the

whole Oman race is no more

important than a cigarette

butt. The great big question,

though, is whether I put it

across or not."

At that point a dozen people

came in, all talking about

the same subject.

"Hi, Jarve," Karns said. "I

still say you ought to take up

poker as a life work. Tiny,

let's you and him sit down

now and play a few hands."

"Mais non!" de Vaux shook

his head violently, shrugged

his shoulders and threw both

arms wide. "By the sacred

name of a small blue cabbage,

not me!"

Karns laughed. "How did

you have the guts to state so

many things as facts? If you'd

guessed wrong just once—"

"I didn't." Hilton grinned.

"Think back, Bill. The only

thing I said as a fact was that

we as a race are better than

the Masters were, and that is

obvious. Everything else was

implication, logic, and bluff."

"That's right, at that. And

they were neurotic and decadent.

No question about

that."

"But listen, boss." This was

Stella Wing. "About this

mind-reading business. If

Laro could read your mind,

he'd know you were bluffing

and ... Oh, that 'Omans can

read only what Masters wish

Omans to read', eh? But d'you

think that applies to us?"

"I'm sure it does, and I was

thinking some pretty savage

thoughts. And I want to caution

all of you: whenever

you're near any Oman, start

thinking that you're beginning

to agree with me that

they're useless to us, and let

them know it. Now get out

on the job, all of you. Scat!"

"Just a minute," Poynter

said. "We're going to have to

keep on using the Omans and

their cars, aren't we?"

"Of course. Just be superior

and distant. They're on

probation—we haven't decided

yet what to do about them.

Since that happens to be

true, it'll be easy."

HILTON and Sandra went

to their tiny office. There

wasn't room to pace the floor,

but Hilton tried to pace it

anyway.

"Now don't say again that

you want to do something,"

Sandra said, brightly. "Look

what happened when you said

that yesterday."

"I've got a job, but I don't

know enough to do it. The

creche—there's probably only

one on the planet. So I want

you to help me think. The

Masters were very sensitive

to radiation. Right?"

"Right. That city on Fuel

Bin was kept deconned to

zero, just in case some Master

wanted to visit it."

"And the Masters had to

work in the creche whenever

anything really new had to

be put into the prototype

brain."

"I'd say so, yes."

"So they had armor. Probably

as much better than our

radiation suits as the rest of

their stuff is. Now. Did they

or did they not have thought

screens?"

"Ouch! You think of the

damnedest things, chief." She

caught her lower lip between

her teeth and concentrated.

"... I don't know. There are

at least fifty vectors, all

pointing in different directions."

"I know it. The key one in

my opinion is that the Masters

gave 'em both telepathy

and speech."

"I considered that and

weighted it. Even so, the

probability is only about

point sixty-five. Can you take

that much of a chance?"

"Yes. I can make one or

two mistakes. Next, about

finding that creche. Any spot

of radiation on the planet

would be it, but the search