The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Mississippi Saucer

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

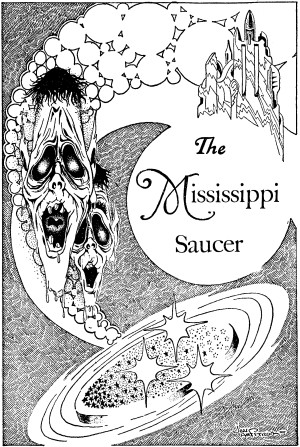

Title: The Mississippi Saucer

Author: Frank Belknap Long

Illustrator: Jon Arfstrom

Release date: November 20, 2007 [eBook #23568]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Joel Schlosberg and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MISSISSIPPI SAUCER ***

Transcriber's Note:

This eBook was produced from Weird Tales, March

1951, pp. 26-36. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

p. 26

Something of the wonder that must have come to men

seeking magic in the sky in days long vanished.

Heading by Jon Arfstrom

p. 27

Jimmy watched the Natchez Belle

draw near, a shining eagerness in his

stare. He stood on the deck of the

shantyboat, his toes sticking out of his socks,

his heart knocking against his ribs. Straight

down the river the big packet boat came,

purpling the water with its shadow, its

smokestacks belching soot.

Jimmy had a wild talent for collecting

things. He knew exactly how to infuriate

the captains without sticking out his neck.

Up and down the Father of Waters, from

the bayous of Louisiana to the Great Sandy

other little shantyboat boys envied Jimmy

and tried hard to imitate him.

But Jimmy had a very special gift, a

genius for pantomime. He'd wait until

there was a glimmer of red flame on the

river and small objects stood out with a

startling clarity. Then he'd go into his act.

Nothing upset the captains quite so much

as Jimmy's habit of holding a big, croaking

bullfrog up by its legs as the riverboats

went steaming past. It was a surefire way of

reminding the captains that men and frogs

were brothers under the skin. The puffed-out

throat of the frog told the captains

exactly what Jimmy thought of their cheek.

Jimmy refrained from making faces, or

sticking out his tongue at the grinning

roustabouts. It was the frog that did the

trick.

In the still dawn things came sailing

Jimmy's way, hurled by captains with a

twinkle of repressed merriment dancing in

eyes that were kindlier and more tolerant

than Jimmy dreamed.

Just because shantyboat folk had no right

to insult the riverboats Jimmy had collected

forty empty tobacco tins, a down-at-heels

shoe, a Sears Roebuck catalogue and—more

rolled up newspapers than Jimmy could

ever read.

Jimmy could read, of course. No matter

how badly Uncle Al needed a new pair of

shoes, Jimmy's education came first. So

Jimmy had spent six winters ashore in a

first-class grammar school, his books paid

for out of Uncle Al's "New Orleans"

money.

Uncle Al, blowing on a vinegar jug and

making sweet music, the holes in his socks

much bigger than the holes in Jimmy's

socks. Uncle Al shaking his head and saying

sadly, "Some day, young fella, I ain't

gonna sit here harmonizing. No siree! I'm

gonna buy myself a brand new store suit,

trade in this here jig jug for a big round

banjo, and hie myself off to the Mardi

Gras. Ain't too old thataway to git a little

fun out of life, young fella!"

Poor old Uncle Al. The money he'd

saved up for the Mardi Gras never seemed

to stretch far enough. There was enough

kindness in him to stretch like a rainbow

over the bayous and the river forests of

sweet, rustling pine for as far as the eye

could see. Enough kindness to wrap all of

Jimmy's life in a glow, and the life of

Jimmy's sister as well.

Jimmy's parents had died of winter

pneumonia too soon to appreciate Uncle Al.

But up and down the river everyone knew

that Uncle Al was a great man.

Enemies? Well, sure, all great men

made enemies, didn't they?

The Harmon brothers were downright

sinful about carrying their feuding meanness

right up to the doorstep of Uncle Al,

if it could be said that a man living in a

shantyboat had a doorstep.

Uncle Al made big catches and the Harmon

brothers never seemed to have any

luck. So, long before Jimmy was old

enough to understand how corrosive envy

could be the Harmon brothers had started

feuding with Uncle Al.

"Jimmy, here comes the Natchez Belle!

Uncle Al says for you to get him a newspaper.

The newspaper you got him yesterday

he couldn't read no-ways. It was soaking

wet!"

Jimmy turned to glower at his sister. Up

and down the river Pigtail Anne was known

as a tomboy, but she wasn't—no-ways. She

p. 28

was Jimmy's little sister. That meant Jimmy

was the man in the family, and wore the

pants, and nothing Pigtail said or did could

change that for one minute.

"Don't yell at me!" Jimmy complained.

"How can I get Captain Simmons mad if

you get me mad first? Have a heart, will

you?"

But Pigtail Anne refused to budge. Even

when the Natchez Belle loomed so close to

the shantyboat that it blotted out the sky

she continued to crowd her brother, preventing

him from holding up the frog and

making Captain Simmons squirm.

But Jimmy got the newspaper anyway.

Captain Simmons had a keen insight into

tomboy psychology, and from the bridge of

the Natchez Belle he could see that Pigtail

was making life miserable for Jimmy.

True—Jimmy had no respect for packet

boats and deserved a good trouncing. But

what a scrapper the lad was! Never let it be

said that in a struggle between the sexes

the men of the river did not stand shoulder

to shoulder.

The paper came sailing over the shining

brown water like a white-bellied buffalo

cat shot from a sling.

Pigtail grabbed it before Jimmy could

give her a shove. Calmly she unwrapped it,

her chin tilted in bellicose defiance.

As the Natchez Belle dwindled around

a lazy, cypress-shadowed bend Pigtail Anne

became a superior being, wrapped in a

cosmopolitan aura. A wide-eyed little girl

on a swaying deck, the great outside world

rushing straight toward her from all directions.

Pigtail could take that world in her

stride. She liked the fashion page best, but

she was not above clicking her tongue at

everything in the paper.

"Kidnap plot linked to airliner crash

killing fifty," she read. "Red Sox blank

Yanks! Congress sits today, vowing vengeance!

Million dollar heiress elopes with

a clerk! Court lets dog pick owner! Girl of

eight kills her brother in accidental shooting!"

"I ought to push your face right down

in the mud," Jimmy muttered.

"Don't you dare! I've a right to see

what's going on in the world!"

"You said the paper was for Uncle Al!"

"It is—when I get finished with it."

Jimmy started to take hold of his sister's

wrist and pry the paper from her clasp.

Only started—for as Pigtail wriggled back

sunlight fell on a shadowed part of the

paper which drew Jimmy's gaze as sunlight

draws dew.

Exciting wasn't the word for the headline.

It seemed to blaze out of the page at

Jimmy as he stared, his chin nudging Pigtail's

shoulder.

NEW FLYING MONSTER REPORTED

BLAZING GULF STATE SKIES

Jimmy snatched the paper and backed

away from Pigtail, his eyes glued to the

headline.

He was kind to his sister, however.

He read the news item aloud, if an

account so startling could be called an item.

To Jimmy it seemed more like a dazzling

burst of light in the sky.

"A New Orleans resident reported today

that he saw a big bright object 'roundish

like a disk' flying north, against the

wind. 'It was all lighted up from inside!'

the observer stated. 'As far as I could tell

there were no signs of life aboard the thing.

It was much bigger than any of the flying

saucers previously reported!'"

"People keep seeing them!" Jimmy muttered,

after a pause. "Nobody knows where

they come from! Saucers flying through the

sky, high up at night. In the daytime, too!

Maybe we're being watched, Pigtail!"

"Watched? Jimmy, what do you mean?

What you talking about?"

Jimmy stared at his sister, the paper

jiggling in his clasp. "It's way over your

head, Pigtail!" he said sympathetically. "I'll

prove it! What's a planet?"

"A star in the sky, you dope!" Pigtail

almost screamed. "Wait'll Uncle Al hears

what a meanie you are. If I wasn't your

sister you wouldn't dare grab a paper that

doesn't belong to you."

p. 29

Jimmy refused to be enraged. "A planet's

not a star, Pigtail," he said patiently. "A

star's a big ball of fire like the sun. A

planet is small and cool, like the Earth.

Some of the planets may even have people

on them. Not people like us, but people

all the same. Maybe we're just frogs to

them!"

"You're crazy, Jimmy! Crazy, crazy, you

hear?"

Jimmy started to reply, then shut his

mouth tight. Big waves were nothing new

in the wake of steamboats, but the shantyboat

wasn't just riding a swell. It was swaying

and rocking like a floating barrel in

the kind of blow Shantyboaters dreaded

worse than the thought of dying.

Jimmy knew that a big blow could come

up fast. Straight down from the sky in

gusts, from all directions, banging

against the boat like a drunken roustabout,

slamming doors, tearing away mooring

planks.

The river could rise fast too. Under the

lashing of a hurricane blowing up

from the gulf the river could lift a shantyboat

right out of the water, and smash it to

smithereens against a tree.

But now the blow was coming from just

one part of the sky. A funnel of wind was

churning the river into a white froth and

raising big swells directly offshore. But the

river wasn't rising and the sun was shining

in a clear sky.

Jimmy knew a dangerous floodwater

storm when he saw one. The sky had to be

dark with rain, and you had to feel scared,

in fear of drowning.

Jimmy was scared, all right. That part of

it rang true. But a hollow, sick feeling in

his chest couldn't mean anything by itself,

he told himself fiercely.

Pigtail Anne saw the disk before Jimmy

did. She screamed and pointed skyward, her

twin braids standing straight out in the

wind like the ropes on a bale of cotton,

when smokestacks collapse and a savage

howling sends the river ghosts scurrying

for cover.

Straight down out of the sky the disk

p. 30

swooped, a huge, spinning shape as flat as

a buckwheat cake swimming in a golden

haze of butterfat.

But the disk didn't remind Jimmy of a

buckwheat cake. It made him think instead

of a slowly turning wheel in the pilot house

of a rotting old riverboat, a big, ghostly

wheel manned by a steersman a century

dead, his eye sockets filled with flickering

swamp lights.

It made Jimmy want to run and hide.

Almost it made him want to cling to his

sister, content to let her wear the pants if

only he could be spared the horror.

For there was something so chilling

about the downsweeping disk that Jimmy's

heart began leaping like a vinegar jug bobbing

about in the wake of a capsizing fishboat.

Lower and lower the disk swept, trailing

plumes of white smoke, lashing the water

with a fearful blow. Straight down over the

cypress wilderness that fringed the opposite

bank, and then out across the river with a

long-drawn whistling sound, louder than

the air-sucking death gasps of a thousand

buffalo cats.

Jimmy didn't see the disk strike the shining

broad shoulders of the Father of

Waters, for the bend around which the

Natchez Belle had steamed so proudly hid

the sky monster from view. But Jimmy did

see the waterspout, spiraling skyward like

the atom bomb explosion he'd goggled at

in the pages of an old Life magazine, all

smudged now with oily thumbprints.

Just a roaring for an instant—and a big

white mushroom shooting straight up into

the sky. Then, slowly, the mushroom decayed

and fell back, and an awful stillness

settled down over the river.

The stillness was broken by a shrill cry

from Pigtail Anne. "It was a flying

saucer! Jimmy, we've seen one! We've seen

one! We've—"

"Shut your mouth, Pigtail!"

Jimmy shaded his eyes and stared out

across the river, his chest a throbbing ache.

He was still staring when a door creaked

behind him.

Jimmy trembled. A tingling fear went

through him, for he found it hard to realize

that the disk had swept around the bend

out of sight. To his overheated imagination

it continued to fill all of the sky above

him, overshadowing the shantyboat, making

every sound a threat.

Sucking the still air deep into his lungs,

Jimmy swung about.

Uncle Al was standing on the deck in

a little pool of sunlight, his gaunt, hollow-cheeked

face set in harsh lines. Uncle Al

was shading his eyes too. But he was staring

up the river, not down.

"Trouble, young fella," he grunted.

"Sure as I'm a-standin' here. A barrelful o'

trouble—headin' straight for us!"

Jimmy gulped and gestured wildly toward

the bend. "It came down over there,

Uncle Al!" he got out. "Pigtail saw it, too!

A big, flying—"

"The Harmons are a-comin', young

fella," Uncle Al drawled, silencing Jimmy

with a wave of his hand. "Yesterday I

rowed over a Harmon jug line without

meanin' to. Now Jed Harmon's tellin' everybody

I stole his fish!"

Very calmly Uncle Al cut himself a slice

of the strongest tobacco on the river and

packed it carefully in his pipe, wadding it

down with his thumb.

He started to put the pipe between his

teeth, then thought better of it.

"I can bone-feel the Harmon boat a-comin',

young fella," he said, using the

pipe to gesture with. "Smooth and quiet

over the river like a moccasin snake."

Jimmy turned pale. He forgot about the

disk and the mushrooming water spout.

When he shut his eyes he saw only a red

haze overhanging the river, and a shantyboat

nosing out of the cypresses, its windows

spitting death.

Jimmy knew that the Harmons had

waited a long time for an excuse. The

Harmons were law-respecting river rats

with sharp teeth. Feuding wasn't lawful,

but murder could be made lawful by whittling

down a lie until it looked as sharp

as the truth.

p. 31

The Harmon brothers would do their

whittling down with double-barreled shotguns.

It was easy enough to make murder

look like a lawful crime if you could point

to a body covered by a blanket and say,

"We caught him stealing our fish! He was

a-goin' to kill us—so we got him first."

No one would think of lifting the

blanket and asking Uncle Al about it. A

man lying stiff and still under a blanket

could no more make himself heard than a

river cat frozen in the ice.

"Git inside, young 'uns. Here they

come!"

Jimmy's heart skipped a beat. Down the

river in the sunlight a shantyboat was drifting.

Jimmy could see the Harmon brothers

crouching on the deck, their faces livid

with hate, sunlight glinting on their arm-cradled

shotguns.

The Harmon brothers were not in the

least alike. Jed Harmon was tall and gaunt,

his right cheek puckered by a knife scar, his

cruel, thin-lipped mouth snagged by his

teeth. Joe Harmon was small and stout, a

little round man with bushy eyebrows and

the flabby face of a cottonmouth snake.

"Go inside, Pigtail," Jimmy said, calmly.

"I'm a-going to stay and fight!"

Uncle Al grabbed Jimmy's arm and

swung him around. "You heard what

I said, young fella. Now git!"

"I want to stay here and fight with you,

Uncle Al," Jimmy said.

"Have you got a gun? Do you want to

be blown apart, young fella?"

"I'm not scared, Uncle Al," Jimmy

pleaded. "You might get wounded. I know

how to shoot straight, Uncle Al. If you get

hurt I'll go right on fighting!"

"No you won't, young fella! Take Pigtail

inside. You hear me? You want me to take

you across my knee and beat the livin'

stuffings out of you?"

Silence.

Deep in his uncle's face Jimmy saw an

anger he couldn't buck. Grabbing Pigtail

Anne by the arm, he propelled her across

the deck and into the dismal front room of

the shantyboat.

The instant he released her she glared

at him and stamped her foot. "If Uncle Al

gets shot it'll be your fault," she said

cruelly. Then Pigtail's anger really flared

up.

"The Harmons wouldn't dare shoot us

'cause we're children!"

For an instant brief as a dropped heartbeat

Jimmy stared at his sister with unconcealed

admiration.

"You can be right smart when you've got

nothing else on your mind, Pigtail," he said.

"If they kill me they'll hang sure as shooting!"

Jimmy was out in the sunlight again before

Pigtail could make a grab for him.

Out on the deck and running along the

deck toward Uncle Al. He was still running

when the first blast came.

It didn't sound like a shotgun blast.

The deck shook and a big swirl of smoke

floated straight toward Jimmy, half blinding

him and blotting Uncle Al from view.

When the smoke cleared Jimmy could

see the Harmon shantyboat. It was less than

thirty feet away now, drifting straight past

and rocking with the tide like a topheavy

flatbarge.

On the deck Jed Harmon was crouching

down, his gaunt face split in a triumphant

smirk. Beside him Joe Harmon stood quivering

like a mound of jelly, a stick of dynamite

in his hand, his flabby face looking

almost gentle in the slanting sunlight.

There was a little square box at Jed Harmon's

feet. As Joe pitched Jed reached into

the box for another dynamite stick. Jed was

passing the sticks along to his brother, depending

on wad dynamite to silence Uncle

Al forever.

Wildly Jimmy told himself that the guns

had been just a trick to mix Uncle Al up,

and keep him from shooting until they had

him where they wanted him.

Uncle Al was shooting now, his face as

grim as death. His big heavy gun was leaping

about like mad, almost hurling him to

the deck.

Jimmy saw the second dynamite stick

spinning through the air, but he never saw

p. 32

it come down. All he could see was the

smoke and the shantyboat rocking, and another

terrible splintering crash as he went

plunging into the river from the end of a

rising plank, a sob strangling in his throat.

Jimmy struggled up from the river with

the long leg-thrusts of a terrified bullfrog,

his head a throbbing ache. As he swam

shoreward he could see the cypresses on the

opposite bank, dark against the sun, and

something that looked like the roof of a

house with water washing over it.

Then, with mud sucking at his heels,

Jimmy was clinging to a slippery bank and

staring out across the river, shading his

eyes against the glare.

Jimmy thought, "I'm dreaming! I'll wake

up and see Uncle Joe blowing on a vinegar

jug. I'll see Pigtail, too. Uncle Al will be

sitting on the deck, taking it easy!"

But Uncle Al wasn't sitting on the deck.

There was no deck for Uncle Al to sit upon.

Just the top of the shantyboat, sinking

lower and lower, and Uncle Al swimming.

Uncle Al had his arm around Pigtail,

and Jimmy could see Pigtail's white face

bobbing up and down as Uncle Al breasted

the tide with his strong right arm.

Closer to the bend was the Harmon

shantyboat. The Harmons were using their

shotguns now, blasting fiercely away at

Uncle Al and Pigtail. Jimmy could see the

smoke curling up from the leaping guns

and the water jumping up and down in

little spurts all about Uncle Al.

There was an awful hollow agony in

Jimmy's chest as he stared, a fear that was

partly a soundless screaming and partly a

vision of Uncle Al sinking down through

the dark water and turning it red.

It was strange, though. Something was

happening to Jimmy, nibbling away at the

outer edges of the fear like a big, hungry

river cat. Making the fear seem less swollen

and awful, shredding it away in little

flakes.

There was a white core of anger in

Jimmy which seemed suddenly to blaze up.

He shut his eyes tight.

In his mind's gaze Jimmy saw himself

holding the Harmon brothers up by

their long, mottled legs. The Harmon

brothers were frogs. Not friendly, good

natured frogs like Uncle Al, but snake

frogs. Cottonmouth frogs.

All flannel red were their mouths, and

they had long evil fangs which dripped

poison in the sunlight. But Jimmy wasn't

afraid of them no-ways. Not any more. He

had too firm a grip on their legs.

"Don't let anything happen to Uncle Al

and Pigtail!" Jimmy whispered, as though

he were talking to himself. No—not exactly

to himself. To someone like himself,

only larger. Very close to Jimmy, but larger,

more powerful.

"Catch them before they harm Uncle Al!

Hurry! Hurry!"

There was a strange lifting sensation in

Jimmy's chest now. As though he could

shake the river if he tried hard enough, tilt

it, send it swirling in great thunderous

white surges clear down to Lake Pontchartrain.

But Jimmy didn't want to tilt the river.

Not with Uncle Al on it and Pigtail,

and all those people in New Orleans who

would disappear right off the streets. They

were frogs too, maybe, but good frogs. Not

like the Harmon brothers.

Jimmy had a funny picture of himself

much younger than he was. Jimmy saw himself

as a great husky baby, standing in the

middle of the river and blowing on it with

all his might. The waves rose and rose, and

Jimmy's cheeks swelled out and the river

kept getting angrier.

No—he must fight that.

"Save Uncle Al!" he whispered fiercely.

"Just save him—and Pigtail!"

It began to happen the instant Jimmy

opened his eyes. Around the bend in the

sunlight came a great spinning disk,

wrapped in a fiery glow.

Straight toward the Harmon shantyboat

the disk swept, water spurting up all about

it, its bottom fifty feet wide. There was no

collision. Only a brightness for one awful

instant where the shantyboat was twisting

and turning in the current, a brightness that

outshone the rising sun.

p. 33

Just like a camera flashbulb going off,

but bigger, brighter. So big and bright that

Jimmy could see the faces of the Harmon

brothers fifty times as large as life, shriveling

and disappearing in a magnifying burst

of flame high above the cypress trees. Just

as though a giant in the sky had trained a

big burning glass on the Harmon brothers

and whipped it back quick.

Whipped it straight up, so that the faces

would grow huge before dissolving as a

warning to all snakes. There was an evil

anguish in the dissolving faces which made

Jimmy's blood run cold. Then the disk was

alone in the middle of the river, spinning

around and around, the shantyboat swallowed

up.

And Uncle Al was still swimming, fearfully

close to it.

The net came swirling out of the disk

over Uncle Al like a great, dew-drenched

gossamer web. It enmeshed him as he swam,

so gently that he hardly seemed to struggle

or even to be aware of what was happening

to him.

Pigtail didn't resist, either. She simply

stopped thrashing in Uncle Al's arms, as

though a great wonder had come upon her.

Slowly Uncle Al and Pigtail were drawn

into the disk. Jimmy could see Uncle Al

reclining in the web, with Pigtail in the

crook of his arm, his long, angular body as

quiet as a butterfly in its deep winter sleep

inside a swaying glass cocoon.

Uncle Al and Pigtail, being drawn together

into the disk as Jimmy stared, a dull

pounding in his chest. After a moment the

pounding subsided and a silence settled

down over the river.

Jimmy sucked in his breath. The voices

began quietly, as though they had been

waiting for a long time to speak to Jimmy

deep inside his head, and didn't want to

frighten him in any way.

"Take it easy, Jimmy! Stay where you

are. We're just going to have a friendly

little talk with Uncle Al."

"A t-talk?" Jimmy heard himself stammering.

"We knew we'd find you where life flows

p. 34

simply and serenely, Jimmy. Your parents

took care of that before they left you with

Uncle Al.

"You see, Jimmy, we wanted you to study

the Earth people on a great, wide flowing

river, far from the cruel, twisted places. To

grow up with them, Jimmy—and to understand

them. Especially the Uncle Als. For

Uncle Al is unspoiled, Jimmy. If there's

any hope at all for Earth as we guide and

watch it, that hope burns most brightly in

the Uncle Als!"

The voice paused, then went on quickly.

"You see, Jimmy, you're not human in the

same way that your sister is human—or

Uncle Al. But you're still young enough

to feel human, and we want you to feel

human, Jimmy."

"W—Who are you?" Jimmy gasped.

"We are the Shining Ones, Jimmy! For

wide wastes of years we have cruised

Earth's skies, almost unnoticed by the

Earth people. When darkness wraps the

Earth in a great, spinning shroud we hide

our ships close to the cities, and glide

through the silent streets in search of our

young. You see, Jimmy, we must watch

and protect the young of our race until

sturdiness comes upon them, and they are

ready for the Great Change."

For an instant there was a strange, humming

sound deep inside Jimmy's head,

like the drowsy murmur of bees in a dew-drenched

clover patch. Then the voice

droned on. "The Earth people are frightened

by our ships now, for their cruel wars

have put a great fear of death in their

hearts. They watch the skies with sharper

eyes, and their minds have groped closer to

the truth.

"To the Earth people our ships are no

longer the fireballs of mysterious legend,

haunted will-o'-the-wisps, marsh flickerings

and the even more illusive distortions of

the sick in mind. It is a long bold step from

fireballs to flying saucers, Jimmy. A day

will come when the Earth people will be

wise enough to put aside fear. Then we

can show ourselves to them as we really

are, and help them openly."

The voice seemed to take more complete

possession of Jimmy's thoughts then, growing

louder and more eager, echoing through

his mind with the persuasiveness of muted

chimes.

"Jimmy, close your eyes tight. We're

going to take you across wide gulfs of space

to the bright and shining land of your

birth."

Jimmy obeyed.

It was a city, and yet it wasn't like New

York or Chicago or any of the other cities

Jimmy had seen illustrations of in the

newspapers and picture magazines.

The buildings were white and domed and

shining, and they seemed to tower straight

up into the sky. There were streets, too,

weaving in and out between the domes like

rainbow-colored spider webs in a forest of

mushrooms.

There were no people in the city, but

down the aerial streets shining objects

swirled with the swift easy gliding of flat

stones skimming an edge of running water.

Then as Jimmy stared into the depths of

the strange glow behind his eyelids the city

dwindled and fell away, and he saw a huge

circular disk looming in a wilderness of

shadows. Straight toward the disk a shining

object moved, bearing aloft on filaments of

flame a much smaller object that struggled

and mewed and reached out little white

arms.

Closer and closer the shining object came,

until Jimmy could see that it was carrying

a human infant that stared straight at

Jimmy out of wide, dark eyes. But before

he could get a really good look at the shining

object it pierced the shadows and

passed into the disk.

There was a sudden, blinding burst of

light, and the disk was gone.

Jimmy opened his eyes.

"You were once like that baby, Jimmy!"

the voice said. "You were carried by your

parents into a waiting ship, and then out

across wide gulfs of space to Earth.

"You see, Jimmy, our race was once entirely

human. But as we grew to maturity

we left the warm little worlds where our

p. 35

infancy was spent, and boldly sought the

stars, shedding our humanness as sunlight

sheds the dew, or a bright, soaring moth of

the night its ugly pupa case.

"We grew great and wise, Jimmy, but

not quite wise enough to shed our human

heritage of love and joy and heartbreak.

In our childhood we must return to the

scenes of our past, to take root again in

familiar soil, to grow in power and wisdom

slowly and sturdily, like a seed dropped

back into the loam which nourished the

great flowering mother plant.

"Or like the eel of Earth's seas, Jimmy,

that must be spawned in the depths of the

great cold ocean, and swim slowly back to

the bright highlands and the shining rivers

of Earth. Young eels do not resemble their

parents, Jimmy. They're white and thin and

transparent and have to struggle hard to

survive and grow up.

"Jimmy, you were planted here by your

parents to grow wise and strong. Deep in

your mind you knew that we had come to

seek you out, for we are all born human,

and are bound one to another by that knowledge,

and that secret trust.

"You knew that we would watch over

you and see that no harm would come to

you. You called out to us, Jimmy, with all

the strength of your mind and heart. Your

Uncle Al was in danger and you sensed our

nearness.

"It was partly your knowledge that saved

him, Jimmy. But it took courage too, and

a willingness to believe that you were more

than human, and armed with the great

proud strength and wisdom of the Shining

Ones."

The voice grew suddenly gentle, like a

caressing wind.

"You're not old enough yet to go home,

Jimmy! Or wise enough. We'll take you

home when the time comes. Now we just

want to have a talk with Uncle Al, to find

out how you're getting along."

Jimmy looked down into the river and

then up into the sky. Deep down under

the dark, swirling water he could see life

taking shape in a thousand forms. Caddis

flies building bright, shining new nests, and

dragonfly nymphs crawling up toward the

sunlight, and pollywogs growing sturdy

hindlimbs to conquer the land.

But there were cottonmouths down there

too, with death behind their fangs, and no

love for the life that was crawling upward.

When Jimmy looked up into the sky he

could see all the blazing stars of space, with

cottonmouths on every planet of every sun.

Uncle Al was like a bright caddis fly

building a fine new nest, thatched with

kindness, denying himself bright little

Mardi Gras pleasures so that Jimmy could

go to school and grow wiser than Uncle

Al.

"That's right, Jimmy. You're growing

up—we can see that! Uncle Al says he told

you to bide from the cottonmouths. But

you were ready to give your life for your

sister and Uncle Al."

p. 36

"Shucks, it was nothing!" Jimmy heard

himself protesting.

"Uncle Al doesn't think so. And neither

do we!"

A long silence while the river mists

seemed to weave a bright cocoon of

radiance about Jimmy clinging to the bank,

and the great circular disk that had swallowed

up Uncle Al.

Then the voices began again. "No reason

why Uncle Al shouldn't have a little

fun out of life, Jimmy. Gold's easy to make

and we'll make some right now. A big

lump of gold in Uncle Al's hand won't

hurt him in any way."

"Whenever he gets any spending money

he gives it away!" Jimmy gulped.

"I know, Jimmy. But he'll listen to you.

Tell him you want to go to New Orleans,

too!"

Jimmy looked up quickly then. In his

heart was something of the wonder he'd

felt when he'd seen his first riverboat and

waited for he knew not what. Something of

the wonder that must have come to men

seeking magic in the sky, the rainmakers

of ancient tribes and of days long vanished.

Only to Jimmy the wonder came now

with a white burst of remembrance and

recognition.

It was as though he could sense something

of himself in the two towering

spheres that rose straight up out of the

water behind the disk. Still and white and

beautiful they were, like bubbles floating

on a rainbow sea with all the stars of space

behind them.

Staring at them, Jimmy saw himself as

he would be, and knew himself for what

he was. It was not a glory to be long endured.

"Now you must forget again, Jimmy!

Forget as Uncle Al will forget—until we

come for you. Be a little shantyboat boy!

You are safe on the wide bosom of the

Father of Waters. Your parents planted

you in a rich and kindly loam, and in all

the finite universes you will find no cosier

nook, for life flows here with a diversity

that is infinite and—Pigtail! She gets on

your nerves at times, doesn't she, Jimmy?"

"She sure does," Jimmy admitted.

"Be patient with her, Jimmy. She's the

only human sister you'll ever have on

Earth."

"I—I'll try!" Jimmy muttered.

Uncle Al and Pigtail came out of the

disk in an amazingly simple way. They

just seemed to float out, in the glimmering

web. Then, suddenly, there wasn't any disk

on the river at all—just a dull flickering

where the sky had opened like a great,

blazing furnace to swallow it up.

"I was just swimmin' along with Pigtail,

not worryin' too much, 'cause there's no

sense in worryin' when death is starin' you

in the face," Uncle Al muttered, a few

minutes later.

Uncle Al sat on the riverbank beside

Jimmy, staring down at his palm, his vision

misted a little by a furious blinking.

"It's gold, Uncle Al!" Pigtail shrilled.

"A big lump of solid gold—"

"I just felt my hand get heavy and there

it was, young fella, nestling there in my

palm!"

Jimmy didn't seem to be able to say anything.

"High school books don't cost no more

than grammar school books, young fella,"

Uncle Al said, his face a sudden shining.

"Next winter you'll be a-goin' to high

school, sure as I'm a-sittin' here!"

For a moment the sunlight seemed to

blaze so brightly about Uncle Al that Jimmy

couldn't even see the holes in his socks.

Then Uncle Al made a wry face. "Someday,

young fella, when your books are all

paid for, I'm gonna buy myself a brand

new store suit, and hie myself off to the

Mardi Gras. Ain't too old thataway to git

a little fun out of life, young fella!"

Featured Books

Young Robin Hood

George Manville Fenn

lid black; /* a thin black line border.. */ padding: 6px; /* ..spaced a bit out from the gr...

Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 2, No. 5

Various

ct in my memory as if it hadoccurred this very day, I have thoughtthousands of times since, and will...

The Amphibians and Reptiles of Michoacán, México

William Edward Duellman

mphibians in México. Some partsof the country, because of their accessibility, soon became relative...

The Winds of the World

Talbot Mundy

lid black; /* a thin black line border.. */ padding: 6px; /* ..spaced a bit out from the gr...

The Ancient Allan

H. Rider Haggard

e surewhether it is better to be alive or dead. The religious plump for the latter,though I have nev...

The Golden Dream: Adventures in the Far West

R. M. Ballantyne

ball at the end of it, which, strange to say, was transparent, and permitted a bright flame within t...

Pursuit

Lester Del Rey

his head around theroom. There was nothing there.Sweat was beading his forehead, and he could feel ...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "The Mississippi Saucer" :