The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Planet Savers

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Planet Savers

Author: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Illustrator: Irving H. Novick

Release date: March 13, 2010 [eBook #31619]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Meredith Bach, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PLANET SAVERS ***

Transcriber's Note:

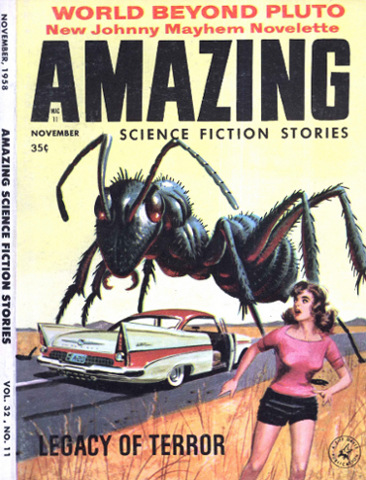

This etext was produced from Amazing Stories, November, 1958. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

| SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL |

THE

PLANET

SAVERS

By

MARION ZIMMER BRADLEY

ILLUSTRATOR NOVICK

A SHORT NOVEL

the planet savers

science fiction in print. She has been away from our

pages too long. So this story is in the nature of a triumphant

return. It could well be her best to date.

By the time I got myself all[84]

the way awake I thought I

was alone. I was lying on a

leather couch in a bare white

room with huge windows, alternate

glass-brick and clear glass.

Beyond the clear windows was a

view of snow-peaked mountains

which turned to pale shadows in

the glass-brick.

Habit and memory fitted

names to all these; the bare office,

the orange flare of the great

sun, the names of the dimming

mountains. But beyond a polished

glass desk, a man sat watching

me. And I had never seen the

man before.

He was chubby, and not

young, and had ginger-colored

eyebrows and a fringe of ginger-colored

hair around the edges of

a forehead which was otherwise

quite pink and bald. He was

wearing a white uniform coat,

and the intertwined caduceus on

the pocket and on the sleeve proclaimed

him a member of the

Medical Service attached to the

Civilian HQ of the Terran Trade

City.

I didn't stop to make all

these evaluations consciously, of

course. They were just part of

my world when I woke up and

found it taking shape around me.

The familiar mountains, the

familiar sun, the strange man.

But he spoke to me in a friendly

way, as if it were an ordinary

thing to find a perfect stranger

sprawled out taking a siesta in

here.

"Could I trouble you to tell me

your name?"[85]

That was reasonable enough.

If I found somebody making

himself at home in my office—if

I had an office—I'd ask him his

name, too. I started to swing my

legs to the floor, and had to stop[86]

and steady myself with one

hand while the room drifted in

giddy circles around me.

"I wouldn't try to sit up just

yet," he remarked, while the

floor calmed down again. Then

he repeated, politely but insistently,

"Your name?"

"Oh, yes. My name." It was—I

fumbled through layers of

what felt like gray fuzz, trying

to lay my tongue on the most

familiar of all sounds, my own

name. It was—why, it was—I

said, on a high rising note,

"This is damn silly," and swallowed.

And swallowed again.

Hard.

"Calm down," the chubby man

said soothingly. That was easier

said than done. I stared at him

in growing panic and demanded,

"But, but, have I had amnesia

or something?"

"Or something."

"What's my name?"

"Now, now, take it easy! I'm

sure you'll remember it soon

enough. You can answer other

questions, I'm sure. How old are

you?"

I answered eagerly and quickly,

"Twenty-two."

The chubby man scribbled

something on a card. "Interesting.

In-ter-est-ing. Do you know

where we are?"

I looked around the office. "In

the Terran Headquarters. From

your uniform, I'd say we were

on Floor 8—Medical."

He nodded and scribbled

again, pursing his lips. "Can

you—uh—tell me what planet we

are on?"

I had to laugh. "Darkover," I

chuckled, "I hope! And if you

want the names of the moons,

or the date of the founding of

the Trade City, or something—"

He gave in, laughing with me.

"Remember where you were

born?"

"On Samarra. I came here

when I was three years old—my

father was in Mapping and Exploring—"

I stopped short, in

shock. "He's dead!"

"Can you tell me your father's

name?"

"Same as mine. Jay—Jason—"

the flash of memory closed

down in the middle of a word.

It had been a good try, but it

hadn't quite worked. The doctor

said soothingly, "We're doing

very well."

"You haven't told me anything,"

I accused. "Who are

you? Why are you asking me all

these questions?"

He pointed to a sign on his

desk. I scowled and spelled out

the letters. "Randall ... Forth

... Director ... Department

..." and Dr. Forth made a note.

I said aloud, "It is—Doctor

Forth, isn't it?"

"Don't you know?"

I looked down at myself, and

shook my head. "Maybe I'm Doctor

Forth," I said, noticing for

the first time that I was also

wearing a white coat with the

caduceus emblem of Medical.

But it had the wrong feel, as if

I were dressed in somebody else's

clothes. I was no doctor, was I?[87]

I pushed back one sleeve slightly,

exposing a long, triangular scar

under the cuff. Dr. Forth—by

now I was sure he was Dr. Forth—followed

the direction of my

eyes.

"Where did you get the scar?"

"Knife fight. One of the bands

of those-who-may-not-enter-cities

caught us on the slopes,

and we—" the memory thinned

out again, and I said despairingly,

"It's all confused! What's the

matter? Why am I up on Medical?

Have I had an accident?

Amnesia?"

"Not exactly. I'll explain."

I got up and walked to the

window, unsteadily because my

feet wanted to walk slowly while

I felt like bursting through some

invisible net and striding there

at one bound. Once I got to the

window the room stayed put

while I gulped down great

breaths of warm sweetish air. I

said, "I could use a drink."

"Good idea. Though I don't

usually recommend it." Forth

reached into a drawer for a flat

bottle; poured tea-colored liquid

into a throwaway cup. After a

minute he poured more for himself.

"Here. And sit down, man.

You make me nervous, hovering

like that."

I didn't sit down. I strode to

the door and flung it open.

Forth's voice was low and unhurried.

"What's the matter? You can

go out, if you want to, but won't

you sit down and talk to me for

a minute? Anyway, where do

you want to go?"

The question made me uncomfortable.

I took a couple of long

breaths and came back into the

room. Forth said, "Drink this,"

and I poured it down. He refilled

the cup unasked, and I

swallowed that too and felt the

hard lump in my middle begin

to loosen up and dissolve.

Forth said, "Claustrophobia

too. Typical," and scribbled on

the card some more. I was getting

tired of that performance.

I turned on him to tell him so,

then suddenly felt amused—or

maybe it was the liquor working

in me. He seemed such a funny

little man, shutting himself up

inside an office like this and talking

about claustrophobia and

watching me as if I were a big

bug. I tossed the cup into a disposal.

"Isn't it about time for a few

of those explanations?"

"If you think you can take it.

How do you feel now?"

"Fine." I sat down on the

couch again, leaning back and

stretching out my long legs comfortably.

"What did you put in

that drink?"

He chuckled. "Trade secret.

Now; the easiest way to explain

would be to let you watch a film

we made yesterday."

"To watch—" I stopped. "It's

your time we're wasting."

He punched a button on the

desk, spoke into a mouthpiece.

"Surveillance? Give us a monitor

on—" he spoke a string of

incomprehensible numbers, while

I lounged at ease on the couch.[88]

Forth waited for an answer,

then touched another button and

steel louvers closed noiselessly

over the windows, blacking them

out. I rose in sudden panic, then

relaxed as the room went dark.

The darkness felt oddly more

normal than the light, and I

leaned back and watched the

flickers clear as one wall of the

office became a large visionscreen.

Forth came and sat beside

me on the leather couch, but

in the picture Forth was there,

sitting at his desk, watching another

man, a stranger, walk into

the office.

Like Forth, the newcomer

wore a white coat with the caduceus

emblems. I disliked the

man on sight. He was tall and

lean and composed, with a dour

face set in thin lines. I guessed

that he was somewhere in his

thirties. Dr.-Forth-in-the-film

said, "Sit down, Doctor," and I

drew a long breath, overwhelmed

by a curious, certain sensation.

I have been here before. I

have seen this happen before.

(And curiously formless I felt.

I sat and watched, and I knew I

was watching, and sitting. But

it was in that dreamlike fashion,

where the dreamer at once

watches his visions and participates

in them....)

"Sit down, Doctor," Forth said,

"did you bring in the reports?"

Jay Allison carefully took the

indicated seat, poised nervously

on the edge of the chair. He sat

very straight, leaning forward

only a little to hand a thick folder

of papers across the desk.

Forth took it, but didn't open it.

"What do you think, Dr. Allison?"

"There is no possible room for

doubt." Jay Allison spoke precisely,

in a rather high-pitched

and emphatic tone. "It follows

the statistical pattern for all recorded

attacks of 48-year fever

... by the way, sir, haven't we

any better name than that for

this particular disease? The

term '48-year fever' connotes a

fever of 48 years duration,

rather than a pandemic recurring

every 48 years."

"A fever that lasted 48 years

would be quite a fever," Dr.

Forth said with the shadow of a

grim smile. "Nevertheless that's

the only name we have so far.

Name it and you can have it.

Allison's disease?"

Jay Allison greeted this pleasantry

with a repressive frown.

"As I understand it, the disease

cycle seems to be connected

somehow with the once-every-48-years

conjunction of the four

moons, which explains why the

Darkovans are so superstitious

about it. The moons have remarkably

eccentric orbits—I

don't know anything about that

part, I'm quoting Dr. Moore. If

there's an animal vector to the

disease, we've never discovered

it. The pattern runs like this; a

few cases in the mountain districts,

the next month a hundred-odd

cases all over this part

of the planet. Then it skips exactly

three months without increase.

The next upswing puts[89]

the number of reported cases in

the thousands, and three months

after that, it reaches real pandemic

proportions and decimates

the entire human population of

Darkover."

"That's about it," Forth admitted.

They bent together over

the folder, Jay Allison drawing

back slightly to avoid touching

the other man.

Forth said, "We Terrans have

had a Trade compact on Darkover

for a hundred and fifty-two

years. The first outbreak of this

48-year fever killed all but a

dozen men out of three hundred.

The Darkovans were worse off

than we were. The last outbreak

wasn't quite so bad, but it was

bad enough, I've heard. It has

an 87 per cent mortality—for

humans, that is. I understand the

trailmen don't die of it."

"The Darkovans call it the

trailmen's fever, Dr. Forth, because

the trailmen are virtually

immune to it. It remains in their

midst as a mild ailment taken by

children. When it breaks out

into the virulent form every 48

years, most of the trailmen are

already immune. I took the disease

myself as a child—maybe

you heard?"

Forth nodded. "You may be

the only Terran ever to contract

the disease and survive."

"The trailmen incubate the

disease," Jay Allison said. "I

should think the logical thing

would be to drop a couple of

hydrogen bombs on the trail

cities—and wipe it out for good

and all."

(Sitting on the Sofa in Forth's

dark office, I stiffened with such

fury that he shook my shoulder

and muttered, "Easy, there,

man!")

Dr. Forth, on the screen, looked

annoyed, and Jay Allison

said, with a grimace of distaste,

"I didn't mean that literally. But

the trailmen are not human. It

wouldn't be genocide, just an exterminator's

job. A public health

measure."

Forth looked shocked as he

realized that the younger man

meant what he was saying. He

said, "Galactic center would

have to rule on whether they're

dumb animals or intelligent non-humans,

and whether they're

entitled to the status of a civilization.

All precedent on Darkover

is toward recognizing them

as men—and good God, Jay,

you'd probably be called as a witness

for the defense! How can

you say they're not human after

your experience with them?

Anyway, by the time their status

was finally decided, half of the

recognizable humans on Darkover

would be dead. We need a

better solution than that."

He pushed his chair back and

looked out the window.

"I won't go into the political

situation," he said, "you aren't

interested in Terran Empire

politics, and I'm no expert either.

But you'd have to be deaf, dumb

and blind not to know that Darkover's

been playing the immovable

object to the irresistible

force. The Darkovans are more[90]

advanced in some of the non-causative

sciences than we are,

and until now, they wouldn't admit

that Terra had a thing to

contribute. However—and this is

the big however—they do know,

and they're willing to admit, that

our medical sciences are better

than theirs."

"Theirs being practically non-existent."

"Exactly—and this could be

the first crack in the barrier.

You may not realize the significance

of this, but the Legate received

an offer from the Hasturs

themselves."

Jay Allison murmured, "I'm

to be impressed?"

"On Darkover you'd damn well

better be impressed when the

Hasturs sit up and take notice."

"I understand they're telepaths

or something—"

"Telepaths, psychokinetics,

parapsychs, just about anything

else. For all practical purposes

they're the Gods of Darkover.

And one of the Hasturs—a

rather young and unimportant

one, I'll admit, the old man's

grandson—came to the Legate's

office, in person, mind you. He

offered, if the Terran Medical

would help Darkover lick the

trailmen's fever, to coach selected

Terran men in matrix mechanics."

"Good Lord," Jay said. It was

a concession beyond Terra's

wildest dreams; for a hundred

years they had tried to beg, buy

or steal some knowledge of the

mysterious science of matrix

mechanics—that curious discipline

which could turn matter

into raw energy, and vice versa,

without any intermediate stages

and without fission by-products.

Matrix mechanics had made the

Darkovans virtually immune to

the lure of Terra's advanced

technologies.

Jay said, "Personally I think

Darkovan science is over-rated.

But I can see the propaganda

angle—"

"Not to mention the humanitarian

angle of healing—"

Jay Allison gave one of his

cold shrugs. "The real angle

seems to be this; can we cure

the 48-year fever?"

"Not yet. But we have a lead.

During the last epidemic, a Terran

scientist discovered a blood

fraction containing antibodies

against the fever—in the trailmen.

Isolated to a serum, it

might reduce the virulent 48-year

epidemic form to the mild

form again. Unfortunately, he

died himself in the epidemic,

without finishing his work, and

his notebooks were overlooked

until this year. We have 18,000

men, and their families, on Darkover

now, Jay. Frankly, if we

lose too many of them, we're going

to have to pull out of Darkover—the

big brass on Terra

will write off the loss of a garrison

of professional traders, but

not of a whole Trade City colony.

That's not even mentioning the

prestige we'll lose if our much-vaunted

Terran medical sciences

can't save Darkover from an

epidemic. We've got exactly five[91]

months. We can't synthesize a

serum in that time. We've got

to appeal to the trailmen. And

that's why I called you up here.

You know more about the trailmen

than any living Terran.

You ought to. You spent eight

years in a Nest."

(In Forth's darkened office I

sat up straighter, with a flash

of returning memory. Jay Allison,

I judged, was several years

older than I, but we had one

thing in common; this cold fish

of a man shared with myself that

experience of marvelous years

spent in an alien world!)

Jay Allison scowled, displeased.

"That was years ago. I was

hardly more than a baby. My

father crashed on a Mapping

expedition over the Hellers—God

only knows what possessed

him to try and take a light plane

over those crosswinds. I survived

the crash by the merest chance,

and lived with the trailmen—so

I'm told—until I was thirteen or

fourteen. I don't remember much

about it. Children aren't particularly

observant."

Forth leaned over the desk,

staring. "You speak their language,

don't you?"

"I used to. I might remember

it under hypnosis, I suppose.

Why? Do you want me to translate

something?"

"Not exactly. We were thinking

of sending you on an expedition

to the trailmen themselves."

(In the darkened office, watching

Jay's startled face, I

thought; God, what an adventure!

I wonder—I wonder if

they want me to go with him?)

Forth was explaining: "It

would be a difficult trek. You

know what the Hellers are like.

Still, you used to climb mountains,

as a hobby, before you

went into Medical—"

"I outgrew the childishness of

hobbies many years ago, sir,"

Jay said stiffly.

"We'd get you the best guides

we could, Terran and Darkovan.

But they couldn't do the one

thing you can do. You know the

trailmen, Jay. You might be able

to persuade them to do the one

thing they've never done before."

"What's that?" Jay Allison

sounded suspicious.

"Come out of the mountains.

Send us volunteers—blood donors—we

might, if we had enough

blood to work on, be able to isolate

the right fraction, and

synthesize it, in time to prevent

the epidemic from really taking

hold. Jay, it's a tough mission

and it's dangerous as all hell, but

somebody's got to do it, and I'm

afraid you're the only qualified

man."

"I like my first suggestion

better. Bomb the trailmen—and

the Hellers—right off the

planet." Jay's face was set in

lines of loathing, which he controlled

after a minute, and said,

"I—I didn't mean that. Theoretically

I can see the necessity,

only—" he stopped and swallowed.

"Please say what you were going

to say."[92]

"I wonder if I am as well

qualified as you think? No—don't

interrupt—I find the natives

of Darkover distasteful,

even the humans. As for the

trailmen—"

(I was getting mad and impatient.

I whispered to Forth in

the darkness, "Shut the damn

film off! You couldn't send that

guy on an errand like that! I'd

rather—"

(Forth snapped, "Shut up and

listen!"

(I shut up and the film continued

to repeat.)

Jay Allison was not acting. He

was pained and disgusted. Forth

wouldn't let him finish his explanation

of why he had refused

even to teach in the Medical college

established for Darkovans

by the Terran empire. He interrupted,

and he sounded irritated.

"We know all that. It evidently

never occurred to you, Jay,

that it's an inconvenience to us—that

all this vital knowledge

should lie, purely by accident, in

the hands of the one man who's

too damned stubborn to use it?"

Jay didn't move an eyelash,

where I would have squirmed,

"I have always been aware of

that, Doctor."

Forth drew a long breath. "I'll

concede you're not suitable at

the moment, Jay. But what do

you know of applied psychodynamics?"

"Very little, I'm sorry to say."

Allison didn't sound sorry,

though. He sounded bored to

death with the whole conversation.

"May I be blunt—and personal?"

"Please do. I'm not at all sensitive."

"Basically, then, Doctor Allison,

a person as contained and

repressed as yourself usually has

a clearly defined subsidiary personality.

In neurotic individuals

this complex of personality traits

sometimes splits off, and we get

a syndrome known as multiple,

or alternate personality."

"I've scanned a few of the

classic cases. Wasn't there a

woman with four separate personalities?"

"Exactly. However, you aren't

neurotic, and ordinarily there

would not be the slightest chance

of your repressed alternate taking

over your personality."

"Thank you," Jay murmured

ironically, "I'd be losing sleep

over that."

"Nevertheless I presume you

do have such a subsidiary personality,

although he would

normally never manifest. This

subsidiary—let's call him Jay2—would

embody all the characteristics

which you repress. He

would be gregarious, where you

are retiring and studious; adventurous

where you are cautious;

talkative while you are

taciturn; he would perhaps enjoy

action for its own sake,

while you exercise faithfully in

the gymnasium only for your

health's sake; and he might even

remember the trailmen with

pleasure rather than dislike."[93]

"In short—a blend of all the

undesirable characteristics?"

"One could put it that way.

Certainly he would be a blend of

all the characteristics which you,

Jay1, consider undesirable. But—if

released by hypnotism and

suggestion, he might be suitable

for the job in hand."

"But how do you know I actually

have such an—alternate?"

"I don't. But it's a good guess.

Most repressed—" Forth coughed

and amended, "most disciplined

personalities possess such

a suppressed secondary personality.

Don't you occasionally—rather

rarely—find yourself doing

things which are entirely out

of character for you?"

I could almost feel Allison taking

it in, as he confessed, "Well—yes.

For instance—the other

day—although I dress conservatively

at all times—" he glanced

at his uniform coat, "I found

myself buying—" he stopped

again and his face went an unlovely

terra-cotta color as he finally

mumbled, "a flowered red

sports shirt."

Sitting in the dark I felt

vaguely sorry for the poor gawk,

disturbed by, ashamed of the

only human impulses he ever

had. On the screen Allison

frowned fiercely, "A crazy impulse."

"You could say that, or say it

was an action of the suppressed

Jay2. How about it, Allison? You

may be the only Terran on Darkover,

maybe the only human,

who could get into a trailman's

Nest without being murdered."

"Sir—as a citizen of the Empire,

I don't have any choice, do

I?"

"Jay, look," Forth said, and I

felt him trying to reach through

the barricade and touch, really

touch that cold contained young

man, "we couldn't order any man

to do anything like this. Aside

from the ordinary dangers, it

could destroy your personal balance,

maybe permanently. I'm

asking you to volunteer something

above and beyond the call

of duty. Man to man—what do

you say?"

I would have been moved by

his words. Even at secondhand

I was moved by them. Jay Allison

looked at the floor, and I saw

him twist his long well-kept

surgeon's hands and crack the

knuckles with an odd gesture.

Finally he said, "I haven't any

choice either way, Doctor. I'll

take the chance. I'll go to the

trailmen."

The screen went dark again

and Forth flicked the light on.

He said, "Well?"

I gave it back, in his own intonation,

"Well?" and was exasperated

to find that I was

twisting my own knuckles in the

nervous gesture of Allison's

painful decision. I jerked them

apart and got up.

"I suppose it didn't work,

with that cold fish, and you decided

to come to me instead?

Sure, I'll go to the trailmen for

you. Not with that Allison—I

wouldn't go anywhere with that

guy—but I speak the trailmen's[94]

language, and without hypnosis

either."

Forth was staring at me. "So

you've remembered that?"

"Hell, yes," I said, "my dad

crashed in the Hellers, and a

band of trailmen found me, half

dead. I lived there until I was

about fifteen, then their Old-One

decided I was too human for

them, and they took me out

through Dammerung Pass and

arranged to have me brought

here. Sure, it's all coming back

now. I spent five years in the

Spacemen's Orphanage, then I

went to work taking Terran

tourists on hunting parties and

so on, because I liked being

around the mountains. I—" I

stopped. Forth was staring at

me.

"You think you'd like this

job?"

"It would be tough," I said,

considering. "The People of the

Sky—" (using the trailmen's

name for themselves) "—don't

like outsiders, but they might be

persuaded. The worst part would

be getting there. The plane, or

the 'copter, isn't built that can

get through the crosswinds

around the Hellers and land inside

them. We'd have to go on

foot, all the way from Carthon.

I'd need professional climbers—mountaineers."

"Then you don't share Allison's

attitude?"

"Dammit, don't insult me!" I

discovered that I was on my feet

again, pacing the office restlessly.

Forth stared and mused

aloud, "What's personality anyway?

A mask of emotions, superimposed

on the body and the intellect.

Change the point of

view, change the emotions and

desires, and even with the same

body and the same past experiences,

you have a new man."

I swung round in mid-step. A

new and terrible suspicion, too

monstrous to name, was creeping

up on me. Forth touched a

button and the face of Jay Allison,

immobile, appeared on the

visionscreen. Forth put a mirror

in my hand. He said, "Jason Allison,

look at yourself."

I looked.

"No," I said. And again, "No.

No. No."

Forth didn't argue. He pointed,

with a stubby finger. "Look—"

he moved the finger as he

spoke, "height of forehead. Set

of cheekbones. Your eyebrows

look different, and your mouth,

because the expression is different.

But bony structure—the

nose, the chin—"

I heard myself make a queer

sound; dashed the mirror to the

floor. He grabbed my forearm.

"Steady, man!"

I found a scrap of my voice.

It didn't sound like Allison's.

"Then I'm—Jay2? Jay Allison

with amnesia?"

"Not exactly." Forth mopped

his forehead with an immaculate

sleeve and it came away damp

with sweat, "No—not Jay Allison

as I know him!" He drew a

long breath. "And sit down.

Whoever you are, sit down!"

I sat. Gingerly. Not sure.[95]

"But the man Jay might have

been, given a different temperamental

bias. I'd say—the man

Jay Allison started out to be.

The man he refused to be. Within

his subconscious, he built up

barriers against a whole series

of memories, and the subliminal

threshold—"

"Doc, I don't understand the

psycho talk."

Forth stared. "And you do remember

the trailmen's language.

I thought so. Allison's

personality is suppressed in you,

as yours was in him."

"One thing, Doc. I don't

know a thing about blood fractions

or epidemics. My half of

the personality didn't study

medicine." I took up the mirror

again and broodingly studied

the face there. The high thin

cheeks, high forehead shaded by

coarse dark hair which Jay Allison

had slicked down now heavily

rumpled. I still didn't think I

looked anything like the doctor.

Our voices were nothing alike

either; his had been pitched

rather high, falsetto. My own,

as nearly as I could judge, was a

full octave deeper, and more

resonant. Yet they issued from

the same vocal chords, unless

Forth was having a reasonless,

macabre joke.

"Did I honest-to-God study

medicine? It's the last thing I'd

think about. It's an honest trade,

I guess, but I've never been that

intellectual."

"You—or rather, Jay Allison

is a specialist in Darkovan parasitology,

as well as a very competent

surgeon." Forth was sitting

with his chin in his hands,

watching me intently. He scowled

and said, "If anything, the

physical change is more startling

than the other. I wouldn't have

recognized you."

"That tallies with me. I don't

recognize myself." I added, "—and

the queer thing is, I didn't

even like Jay Allison, to put it

mildly. If he—I can't say he,

can I?"

"I don't know why not.

You're no more Jay Allison than

I am. For one thing, you're

younger. Ten years younger. I

doubt if any of his friends—if

he had any—would recognize

you. You—it's ridiculous to go

on calling you Jay2. What should

I call you?"

"Why should I care? Call me

Jason."

"Suits you," Forth said enigmatically.

"Look, then, Jason.

I'd like to give you a few days

to readjust to your new personality,

but we are really pressed

for time. Can you fly to Carthon

tonight? I've hand-picked a good

crew for you, and sent them on

ahead. You'll meet them there.

You'll find them competent."

I stared at him. Suddenly the

room oppressed me and I found

it hard to breathe. I said in

wonder, "You were pretty sure

of yourself, weren't you?"

Forth just looked at me, for

what seemed a long time. Then

he said, in a very quiet voice,

"No. I wasn't sure at all. But if

you didn't turn up, and I couldn't[96]

talk Jay into it, I'd have had to

try it myself."

Jason Allison, Junior, was

listed on the directory of the

Terran HQ as "Suite 1214, Medical

Residence Corridor." I found

the rooms without any trouble,

though an elderly doctor stared

at me rather curiously as I barged

along the quiet hallway. The

suite—bedroom, minuscule sitting-room,

compact bath—depressed

me; clean, closed-in and

neutral as the man who owned

them, I rummaged them restlessly,

trying to find some scrap of

familiarity to indicate that I had

lived here for the past eleven

years.

Jay Allison was thirty-four

years old. I had given my age,

without hesitation, as 22. There

were no obvious blanks in my

memory; from the moment Jay

Allison had spoken of the trailmen,

my past had rushed back

and stood, complete to yesterday's

supper (only had I eaten

that supper twelve years ago)?

I remembered my father, a

lined silent man who had liked

to fly solitary, taking photograph

after photograph from his plane

for the meticulous work of Mapping

and Exploration. He'd liked

to have me fly with him and I'd

flown over virtually every inch

of the planet. No one else had

ever dared fly over the Hellers,

except the big commercial spacecraft

that kept to a safe altitude.

I vaguely remembered the crash

and the strange hands pulling

me out of the wreckage and the

weeks I'd spent, broken-bodied

and delirious, gently tended by

one of the red-eyed, twittering

women of the trailmen. In all I

had spent eight years in the

Nest, which was not a nest at

all but a vast sprawling city

built in the branches of enormous

trees. With the small and

delicate humanoids who had

been my playfellows, I had gathered

the nuts and buds and

trapped the small arboreal animals

they used for food, taken

my share at weaving clothing

from the fibres of parasite plants

cultivated on the stems, and in

all those eight years I had set

foot on the ground less than a

dozen times, even though I had

travelled for miles through the

tree-roads high above the forest

floor.

Then the Old-One's painful decision

that I was too alien for

them, and the difficult and dangerous

journey my trailmen foster-parents

and foster-brothers

had undertaken, to help me out

of the Hellers and arrange for

me to be taken to the Trade

City. After two years of physically

painful and mentally

rebellious readjustment to daytime

living, the owl-eyed trailmen

saw best, and lived largely,

by moonlight, I had found a

niche for myself, and settled

down. But all of the later years

(after Jay Allison had taken

over, I supposed, from a basic

pattern of memory common to

both of us) had vanished into the

limbo of the subconscious.

A bookrack was crammed[97]

with large microcards; I slipped

one into the viewer, with a queer

sense of spying, and found myself

listening apprehensively to

hear that measured step and Jay

Allison's falsetto voice demanding

what the hell I was doing,

meddling with his possessions.

Eye to the viewer, I read briefly

at random, something about

the management of compound

fracture, then realized I had understood

exactly three words in

a paragraph. I put my fist

against my forehead and heard

the words echoing there emptily;

"laceration ... primary efflusion

... serum and lymph ...

granulation tissue...." I presumed

that the words meant

something and that I once had

known what. But if I had a medical

education, I didn't recall a

syllable of it. I didn't know a

fracture from a fraction.

In a sudden frenzy of impatience

I stripped off the white

coat and put on the first shirt I

came to, a crimson thing that

hung in the line of white coats

like an exotic bird in snow country.

I went back to rummaging

the drawers and bureaus. Carelessly

shoved in a pigeonhole I

found another microcard that

looked familiar; and when I

slipped it mechanically into the

viewer it turned out to be a book

on mountaineering which, oddly

enough, I remembered buying as

a youngster. It dispelled my last,

lingering doubts. Evidently I

had bought it before the personalities

had forked so sharply

apart and separated, Jason from

Jay. I was beginning to believe.

Not to accept. Just to believe it

had happened. The book looked

well-thumbed, and had been

handled so much I had to baby

it into the slot of the viewer.

Under a folded pile of clean

underwear I found a flat half-empty

bottle of whiskey. I remembered

Forth's words that

he'd never seen Jay Allison

drink, and suddenly I thought,

"The fool!" I fixed myself a

drink and sat down, idly scanning

over the mountaineering

book.

Not till I'd entered medical

school, I suspected, did the two

halves of me fork so strongly

apart ... so strongly that there

had been days and weeks and, I

suspected, years where Jay Allison

had kept me prisoner. I tried

to juggle dates in my mind, looked

at a calendar, and got such a

mental jolt that I put it face-down

to think about when I was

a little drunker.

I wondered if my detailed

memories of my teens and early

twenties were the same memories

Jay Allison looked back on.

I didn't think so. People forget

and remember selectively. Week

by week, then, and year by year,

the dominant personality of Jay

had crowded me out; so that the

young rowdy, more than half

Darkovan, loving the mountains,

half-homesick for a non-human

world, had been drowned in the

chilly, austere young medical

student who lost himself in his

work. But I, Jason—I had al[98]ways

been the watcher behind,

the person Jay Allison dared not

be? Why was he past thirty—and

I just 22?

A ringing shattered the silence;

I had to hunt for the intercom

on the bedroom wall. I

said, "Who is it?" and an unfamiliar

voice demanded, "Dr. Allison?"

I said automatically, "Nobody

here by that name," and started

to put back the mouthpiece.

Then I stopped and gulped and

asked, "Is that you, Dr. Forth?"

It was, and I breathed again.

I didn't even want to think

about what I'd say if somebody

else had demanded to know why

in the devil I was answering Dr.

Allison's private telephone.

When Forth had finished, I went

to the mirror, and stared, trying

to see behind my face the sharp

features of that stranger, Doctor

Jason Allison. I delayed, even

while I was wondering what few

things I should pack for a trip

into the mountains and the habit

of hunting parties was making

mental lists about heat-socks and

windbreakers. The face that

looked at me was a young face,

unlined and faintly freckled, the

same face as always except that

I'd lost my suntan; Jay Allison

had kept me indoors too long.

Suddenly I struck the mirror

lightly with my fist.

"The hell with you, Dr. Allison,"

I said, and went to see if

he had kept any clothes fit to

pack.

Dr. Forth was waiting for me

in the small skyport on the roof,

and so was a small 'copter, one

of the fairly old ones assigned

to Medical Service when they

were too beat-up for services

with higher priority. Forth took

one startled stare at my crimson

shirt, but all he said was, "Hello,

Jason. Here's something we've

got to decide right away; do we

tell the crew who you really

are?"

I shook my head emphatically.

"I'm not Jay Allison; I don't

want his name or his reputation.

Unless there are men on the

crew who know Allison by

sight—"

"Some of them do, but I don't

think they'd recognize you."

"Tell them I'm his twin brother,"

I said humorlessly.

"That wouldn't be necessary.

There's not enough resemblance."

Forth raised his head

and beckoned to a man who was

doing something near the 'copter.

He said under his breath,

"You'll see what I mean," as the

man approached.

He wore the uniform of Spaceforce—black

leather with a little

rainbow of stars on his sleeve

meaning he'd seen service on a

dozen different planets, a different

colored star for each one. He

wasn't a young man, but on the

wrong side of fifty, seamed and

burly and huge, with a split lip

and weathered face. I liked his

looks. We shook hands and Forth

said, "This is our man, Kendricks.

He's called Jason, and

he's an expert on the trailmen.

Jason, this is Buck Kendricks."[99]

"Glad to know you, Jason." I

thought Kendricks looked at me

half a second more than necessary.

"The 'copter's ready. Climb

in, Doc—you're going as far as

Carthon, aren't you?"

We put on zippered windbreaks

and the 'copter soared

noiselessly into the pale crimson

sky. I sat beside Forth, looking

down through pale lilac clouds

at the pattern of Darkover

spread below me.

"Kendricks was giving me a

funny eye, Doc. What's biting

him?"

"He has known Jay Allison for

eight years," Forth said quietly,

"and he hasn't recognized you

yet."

But we let it ride at that, to

my great relief, and didn't talk

any more about me at all. As we

flew under silent whirring

blades, turning our backs on the

settled country which lay near

the Trade City, we talked about

Darkover itself. Forth told me

about the trailmen's fever and

managed to give me some idea

about what the blood fraction

was, and why it was necessary

to persuade fifty or sixty of the

humanoids to return with me, to

donate blood from which the

antibody could be, first isolated,

then synthesised.

It would be a totally unheard-of

thing, if I could accomplish

it. Most of the trailmen never

touched ground in their entire

lives, except when crossing the

passes above the snow line. Not

a dozen of them, including my

foster-parents who had so painfully

brought me out across

Dammerung, had ever crossed

the ring of encircling mountains

that walled them away from the

rest of the planet. Humans

sometimes penetrated the lower

forests in search of the trailmen.

It was one-way traffic. The trailmen

never came in search of

them.

We talked, too, about some of

those humans who had crossed

the mountains into trailmen

country—those mountains profanely

dubbed the Hellers by the

first Terrans who had tried to

fly over them in anything lower

or slower than a spaceship. (The

Darkovan name for the Hellers

was even more explicit, and even

in translation, unrepeatable.)

"What about this crew you

picked? They're not Terrans?"

Forth shook his head. "It

would be murder to send anyone

recognizably Terran into the

Hellers. You know how the trailmen

feel about outsiders getting

into their country." I knew.

Forth continued, "Just the same,

there will be two Terrans with

you."

"They don't know Jay Allison?"

I didn't want to be burdened

with anyone—not anyone—who

would know me, or expect

me to behave like my forgotten

other self.

"Kendricks knows you," Forth

said, "but I'm going to be perfectly

truthful. I never knew Jay

Allison well, except in line of

work. I know a lot of things—from

the past couple of days[100]—which

came out during the hypnotic

sessions, which he'd never

have dreamed of telling me, or

anyone else, consciously. And

that comes under the heading of

a professional confidence—even

from you. And for that reason,

I'm sending Kendricks along—and

you're going to have to take

the chance he'll recognize you.

Isn't that Carthon down there?"

Carthon lay nestled under the

outlying foothills of the Hellers,

ancient and sprawling and squatty,

and burned brown with the

dust of five thousand years.

Children ran out to stare at the

'copter as we landed near the

city; few planes ever flew low

enough to be seen, this near the

Hellers.

Forth had sent his crew ahead

and parked them in an abandoned

huge place at the edge of

the city which might once have

been a warehouse or a ruined

palace. Inside there were a couple

of trucks, stripped down to

framework and flatbed like all

machinery shipped through

space from Terra. There were

pack animals, dark shapes in the

gloom. Crates were stacked up

in an orderly untidiness, and at

the far end a fire was burning

and five or six men in Darkovan

clothing—loose sleeved shirts,

tight wrapped breeches, low

boots—were squatting around it,

talking. They got up as Forth

and Kendricks and I walked toward

them, and Forth greeted

them clumsily, in bad accented

Darkovan, then switched to Terran

Standard, letting one of

the men translate for him.

Forth introduced me simply as

"Jason," after the Darkovan custom,

and I looked the men over,

one by one. Back when I'd climbed

for fun, I'd liked to pick my

own men; but whoever had picked

this crew must have known

his business.

Three were mountain Darkovans,

lean swart men enough

alike to be brothers; I learned

after a while that they actually

were brothers, Hjalmar, Garin

and Vardo. All three were well

over six feet, and Hjalmar stood

head and shoulders over his

brothers, whom I never learned

to tell apart. The fourth man, a

redhead, was dressed rather better

than the others and introduced

as Lerrys Ridenow—the

double name indicating high

Darkovan aristocracy. He looked

muscular and agile enough, but

his hands were suspiciously well-kept

for a mountain man, and I

wondered how much experience

he'd had.

The fifth man shook hands

with me, speaking to Kendricks

and Forth as if they were old

friends. "Don't I know you from

someplace, Jason?"

He looked Darkovan, and wore

Darkovan clothes, but Forth had

forewarned me, and attack seemed

the best defense. "Aren't you

Terran?"

"My father was," he said, and

I understood; a situation not exactly

uncommon, but ticklish on

a planet like Darkover. I said

carelessly, "I may have seen you[101]

around the HQ. I can't place you,

though."

"My name's Rafe Scott. I

thought I knew most of the professional

guides on Darkover,

but I admit I don't get into the

Hellers much," he confessed.

"Which route are we going to

take?"

I found myself drawn into the

middle of the group of men, accepting

one of the small sweetish

Darkovan cigarettes, looking

over the plan somebody had

scribbled down on the top of a

packing case. I borrowed a pencil

from Rafe and bent over the

case, sketching out a rough map

of the terrain I remembered so

well from boyhood. I might be

bewildered about blood fractions,

but when it came to climbing I

knew what I was doing. Rafe

and Lerrys and the Darkovan

brothers crowded behind me to

look over the sketch, and Lerrys

put a long fingernail on the

route I'd indicated.

"Your elevation's pretty bad

here," he said diffidently, "and

on the 'Narr campaign the trailmen

attacked us here, and it was

bad fighting along those ledges."

I looked at him with new respect;

dainty hands or not, he

evidently knew the country.

Kendricks patted the blaster on

his hip and said grimly, "But

this isn't the 'Narr campaign.

I'd like to see any trailmen attack

us while I have this."

"But you're not going to have

it," said a voice behind us, a

crisp authoritative voice. "Take

off that gun, man!"

Kendricks and I whirled together,

to see the speaker; a tall

young Darkovan, still standing

in the shadows. The newcomer

spoke to me directly:

"I'm told you are Terran, but

that you understand the trailmen.

Surely you don't intend to

carry fission or fusion weapons

against them?"

And I suddenly realized that

we were in Darkovan territory

now, and that we must reckon

with the Darkovan horror of

guns or of any weapon which

reaches beyond the arm's-length

of the man who wields it. A simple

heat-gun, to the Darkovan

ethical code, is as reprehensible

as a super-cobalt planetbuster.

Kendricks protested, "We

can't travel unarmed through

trailmen country! We're apt to

meet hostile bands of the creatures—and

they're nasty with

those long knives they carry!"

The stranger said calmly,

"I've no objection to you, or

anyone else, carrying a knife for

self-defense."

"A knife?" Kendricks drew

breath to roar. "Listen, you bug-eyed

son-of-a—who do you

think you are, anyway?"

The Darkovans muttered. The

man in the shadows said, "Regis

Hastur."

Kendricks stared pop-eyed. My

own eyes could have popped, but

I decided it was time for me to

take charge, if I were ever going

to. I rapped, "All right, this

is my show. Buck, give me the

gun."[102]

He looked wrathfully at me

for a space of seconds, while I

wondered what I'd do if he

didn't. Then, slowly, he unbuckled

the straps and handed it to

me, butt first.

I'd never realized quite how

undressed a Spaceforce man

looked without his blaster. I balanced

it on my palm for a minute

while Regis Hastur came out

of the shadows. He was tall, and

had the reddish hair and fair

skin of Darkovan aristocracy,

and on his face was some indefinable

stamp—arrogance, perhaps,

or the consciousness that

the Hasturs had ruled this world

for centuries long before the

Terrans brought ships and trade

and the universe to their doors.

He was looking at me as if he

approved of me, and that was

one step worse than the former

situation.

So, using the respectful Darkovan

idiom of speaking to a

superior (which he was) but

keeping my voice hard, I said,

"There's just one leader on any

trek, Lord Hastur. On this one,

I'm it. If you want to discuss

whether or not we carry guns, I

suggest you discuss it with me

in private—and let me give the

orders."

One of the Darkovans gasped.

I knew I could have been mobbed.

But with a mixed bag of

men, I had to grab leadership

quick or be relegated to nowhere.

I didn't give Regis Hastur

a chance to answer that,

either; I said, "Come back here.

I want to talk to you anyway."

He came, and I remembered to

breathe. I led the way to a fairly

deserted corner of the immense

place, faced him and demanded,

"As for you—what are you doing

here? You're not intending

to cross the mountains with

us?"

He met my scowl levelly. "I

certainly am."

I groaned. "Why? You're the

Regent's grandson. Important

people don't take on this kind of

dangerous work. If anything

happens to you, it will be my

responsibility!" I was going to

have enough trouble, I was

thinking, without shepherding

along one of the most revered

Personages on the whole damned

planet! I didn't want anyone

around who had to be fawned

on, or deferred to, or even listened

to.

He frowned slightly, and I had

the unpleasant impression that

he knew what I was thinking.

"In the first place—it will mean

something to the trailmen, won't

it—to have a Hastur with you,

suing for this favor?"

It certainly would. The trailmen

paid little enough heed to

the ordinary humans, except for

considering them fair game for

plundering when they came uninvited

into trailman country.

But they, with all Darkover,

revered the Hasturs, and it was

a fine point of diplomacy—if the

Darkovans sent their most important

leader, they might listen

to him.

"In the second place," Regis[103]

Hastur continued, "the Darkovans

are my people, and it's my

business to negotiate for them.

In the third place, I know the

trailmen's dialect—not well, but

I can speak it a little. And in the

fourth, I've climbed mountains

all my life. Purely as an amateur,

but I can assure you I

won't be in the way."

There was little enough I

could say to that. He seemed to

have covered every point—or

every point but one, and he

added, shrewdly, after a minute,

"Don't worry; I'm perfectly willing

to have you take charge. I

won't claim—privilege."

I had to be satisfied with that.

Darkover is a civilized planet

with a fairly high standard of

living, but it is not a mechanized

or a technological culture. The

people don't do much mining, or

build factories, and the few

which were founded by Terran

enterprise never were very successful;

outside the Terran

Trade City, machinery or modern

transportation is almost unknown.

While the other men checked

and loaded supplies and Rafe

Scott went out to contact some

friends of his and arrange for

last-minute details, I sat down

with Forth to memorize the

medical details I must put so

clearly to the trailmen.

"If we could only have kept

your medical knowledge!"

"Trouble is, being a doctor

doesn't suit my personality," I

said. I felt absurdly light-hearted.

Where I sat, I could raise my

head and study the panorama of

blackish-green foothills which

lay beyond Carthon, and search

out the stone roadways, like a

tiny white ribbon, which we

could follow for the first stage

of the trip. Forth evidently did

not share my enthusiasm.

"You know, Jason, there is one

real danger—"

"Do you think I care about

danger? Or are you afraid I'll

turn—foolhardy?"

"Not exactly. It's not a physical

danger, Jason. It's an emotional—or

rather an intellectual

danger."

"Hell, don't you know any language

but that psycho double-talk?"

"Let me finish, Jason. Jay

Allison may have been repressed,

overcontrolled, but you are seriously

impulsive. You lack a

balance-wheel, if I could put it

that way. And if you run too

many risks, your buried alter-ego

may come to the surface and

take over in sheer self-preservation."

"In other words," I said,

laughing loudly, "if I scare that

Allison stuffed-shirt he may

start stirring in his grave?"

Forth coughed and smothered

a laugh and said that was one

way of putting it. I clapped him

reassuringly on the shoulder and

said, "Forget it, sir. I promise

to be godly, sober and industrious—but

is there any law

against enjoying what I'm doing?"

Somebody burst out of the[104]

warehouse-palace place, and

shouted at me. "Jason? The

guide is here," and I stood up,

giving Forth a final grin. "Don't

you worry. Jay Allison's good

riddance," I said, and went back

to meet the other guide they had

chosen.

And I almost backed out when

I saw the guide. For the guide

was a woman.

She was small for a Darkovan

girl, and narrowly built, the sort

of body that could have been

called boyish or coltish but certainly

not, at first glance, feminine.

Close-cut curls, blue-black

and wispy, cast the faintest of

shadows over a squarish sunburnt

face, and her eyes were so

thickly rimmed with heavy dark

lashes that I could not guess

their color. Her nose was snubbed

and might have looked

whimsical and was instead oddly

arrogant. Her mouth was wide,

and her chin round, and altogether

I dismissed her as not at

all a pretty woman.

She held up her palm and said

rather sullenly, "Kyla-Raineach,

free Amazon, licensed guide."

I acknowledged the gesture

with a nod, scowling. The guild

of free Amazons entered virtually

every masculine field, but that

of mountain guide seemed somewhat

bizarre even for an Amazon.

She seemed wiry and agile

enough, her body, under the

heavy blanket-like clothing, almost

as lean of hip and flat of

breast as my own; only the slender

long legs were unequivocally

feminine.

The other men were checking

and loading supplies; I noted

from the corner of my eye that

Regis Hastur was taking his

turn heaving bundles with the

rest. I sat down on some still-undisturbed

sacks, and motioned

her to sit.

"You've had trail experience?

We're going into the Hellers

through Dammerung, and that's

rough going even for professionals."

She said in a flat expressionless

voice, "I was with the Terran

Mapping expedition to the

South Polar ridge last year."

"Ever been in the Hellers? If

anything happened to me, could

you lead the expedition safely

back to Carthon?"

She looked down at her stubby

fingers. "I'm sure I could,"

she said finally, and started to

rise. "Is that all?"

"One thing more—" I gestured

to her to stay put. "Kyla,

you'll be one woman among

eight men—"

The snubbed nose wrinkled

up; "I don't expect you to crawl

into my blankets, if that's what

you mean. It's not in my contract—I

hope!"

I felt my face burning. Damn

the girl! "It's not in mine, anyway,"

I snapped, "but I can't

answer for seven other men,

most of them mountain roughnecks!"

Even as I said it I wondered

why I bothered; certainly

a free Amazon could defend her

own virtue, or not, if she wanted

to, without any help from me. I[105]

had to excuse myself by adding,

"In either case you'll be a disturbing

element—I don't want

fights, either!"

She made a little low-pitched

sound of amusement. "There's

safety in numbers, and—are you

familiar with the physiological

effect of high altitudes on men

acclimated to low ones?" Suddenly

she threw back her head

and the hidden sound became

free and merry laughter. "Jason,

I'm a free Amazon, and that

means—no, I'm not neutered,

though some of us are. But you

have my word, I won't create

any trouble of any recognizably

female variety." She stood up.

"Now, if you don't mind, I'd like

to check the mountain equipment."

Her eyes were still laughing

at me, but curiously I didn't

mind at all. There was a refreshing

element in her manner.

We started that night, a

curiously lopsided little caravan.

The pack animals were loaded

into one truck and didn't like it.

We had another stripped-down

truck which carried supplies.

The ancient stone roads, rutted

and gullied here and there with

the flood-waters and silt of

decades, had not been planned

for any travel other than the

feet of men or beasts. We passed

tiny villages and isolated country

estates, and a few of the

solitary towers where the matrix

mechanics worked alone with the

secret sciences of Darkover, towers

of glareless stone which

sometimes shone like blue beacons

in the dark.

Kendricks drove the truck

which carried the animals, and

was amused by it. Rafe and I

took turns driving the other

truck, sharing the wide front

seat with Regis Hastur and the

girl Kyla, while the other men

found seats between crates and

sacks in the back. Once while

Rafe was at the wheel and the

girl dozing with her coat over

her face to shut out the fierce

sun, Regis asked me, "What are

the trailcities like?"

I tried to tell him, but I've

never been good at boiling things

down into descriptions, and

when he found I was not disposed

to talk, he fell silent and

I was free to drowse over what

I knew of the trailmen and their

world.

Nature seems to have a sameness

on all inhabited worlds,

tending toward the economy and

simplicity of the human form.

The upright carriage, freeing

the hands, the opposable thumb,

the color-sensitivity of retinal

rods and cones, the development

of language and of lengthy parental

nurture—these things

seem to be indispensable to the

growth of civilization, and in the

end they spell human. Except for

minor variations depending on

climate or foodstuff, the inhabitant

of Megaera or Darkover is

indistinguishable from the Terran

or Sirian; differences are

mainly cultural, and sometimes

an isolated culture will mutate

in a strange direction or remain,[106]

atavists, somewhere halfway to

the summit of the ladder of evolution—which,

at least on the

known planets, still reckons

homo sapiens as the most complex

of nature's forms.

The trailmen were a pausing-place

which had proved tenacious.

When the mainstream of

evolution on Darkover left the

trees to struggle for existence

on the ground, a few remained

behind. Evolution did not cease

for them, but evolved homo arborens;

nocturnal, nystalopic

humanoids who lived out their

lives in the extensive forests.

The truck bumped over the

bad, rutted roads. The wind was

chilly—the truck, a mere conveyance

for hauling, had no such

refinements of luxury as windows.

I jolted awake—what nonsense

had I been thinking?

Vague ideas about evolution

swirled in my brain like burst

bubbles—the trailmen? They

were just the trailmen, who

could explain them? Jay Allison,

maybe? Rafe turned his head

and asked, "Where do we pull

up for the night? It's getting

dark, and we have all this gear

to sort!" I roused myself, and

took over the business of the expedition

again.

But when the trucks had been

parked and a tent pitched and

the pack animals unloaded and

hobbled, and a start made at getting

the gear together—when all

this had been done I lay awake,

listening to Kendricks' heavy

snoring, but myself afraid to

sleep. Dozing in the truck, an

odd lapse of consciousness had

come over me ... myself yet not

myself, drowsing over thoughts

I did not recognize as my own.

If I slept, who would I be when

I woke?

We had made our camp in the

bend of an enormous river, wide

and shallow and unbridged; the

river Kadarin, traditionally a

point of no return for humans

on Darkover. The river is fed by

ocean tides and we would have

to wait for low water to cross.

Beyond the river lay thick forests,

and beyond the forests the

slopes of the Hellers, rising upward

and upward; and their

every fold and every valley was

filled to the brim with forest,

and in the forests lived the trailmen.

But though all this country

was thickly populated with outlying

colonies and nests, it

would be no use to bargain with

any of them; we must deal with

the Old One of the North Nest,

where I had spent so many of

my boyhood years.

From time immemorial, the

trailmen—usually inoffensive—had

kept strict boundaries marked

between their lands and the

lands of ground-dwelling men.

They never came beyond the

Kadarin. On the other hand, almost

any human who ventured

into their territory became, by

that act, fair game for attack.

A few of the Darkovan mountain

people had trade treaties

with the trailmen; they traded

clothing, forged metals, small[107]

implements, in return for nuts,

bark for dyestuffs and certain

leaves and mosses for drugs. In

return, the trailmen permitted

them to hunt in the forest lands

without being molested. But

other humans, venturing into

trailman territory, ran the risk

of merciless raiding; the trailmen

were not bloodthirsty, and

did not kill for the sake of killing,

but they attacked in packs

of two or three dozen, and their

prey would be stripped and plundered

of everything portable.

Travelling through their country

would be dangerous....

The sun was high before we

struck the camp. While the others

were packing up the last

oddments, ready for the saddle,

I gave the girl Kyla the task of

readying the rucksacks we'd

carry after the trails got too bad

even for the pack animals, and

went to stand at the water's

edge, checking the depth of the

ford and glancing up at the

smoke-hazed rifts between peak

and peak.

The men were packing up the

small tent we'd use in the forests,

moving around with a good

deal of horseplay and a certain

brisk bustle. They were a good

crew, I'd already discovered.

Rafe and Lerrys and the three

Darkovan brothers were tireless,

cheerful and mountain-hardened.

Kendricks, obviously out of his

element, could be implicitly relied

on to follow orders, and I

felt that I could fall back on

him. Strange as it seemed, the

very fact that he was a Terran

was vaguely comforting, where

I'd anticipated it would be a

nuisance.

The girl Kyla was still something

of an unknown quantity.

She was too taut and quiet,

working her share but seldom

contributing a word—we were

not yet in mountain country. So

far she was quiet and touchy

with me, although she seemed

natural enough with the Darkovans,

and I let her alone.

"Hi, Jason, get a move on,"

someone shouted, and I walked

back toward the clearing squinting

in the sun. It hurt, and I

touched my face gingerly, suddenly

realizing what had happened.

Yesterday, riding in the

uncovered truck, and this morning,

un-used to the fierce sun of

these latitudes, I had neglected

to take the proper precautions

against exposure and my face

was reddening with sunburn. I

walked toward Kyla, who was

cinching a final load on one of

the pack-animals, which she did

efficiently enough.

She didn't wait for me to ask,

but sized up the situation with

one amused glance at my face.

"Sunburn? Put some of this on

it." She produced a tube of

white stuff; I twisted at the top

inexpertly, and she took it from

me, squeezed the stuff out in her

palm and said, "Stand still and

bend down your head."

She smeared the mixture efficiently

across my forehead and

cheeks. It felt cold and good. I

started to thank her, then broke[108]

off as she burst out laughing.

"What's the matter?"

"You should see yourself!"

she gurgled.

I wasn't amused. No doubt I

presented a grotesque appearance,

and no doubt she had the

right to laugh at it, but I scowled.

It hurt. Intending to put

things back on the proper footing,

I demanded, "Did you make

up the climbing loads?"

"All except bedding. I wasn't

sure how much to allow," she

said. "Jason, have you eyeshades

for when you get on snow?" I

nodded, and she instructed me

severely, "Don't forget them.

Snowblindness—I give you my

word—is even more unpleasant

than sunburn—and very painful!"

"Damn it, girl, I'm not stupid!"

I exploded.

She said, in her expressionless

monotone again, "Then you

ought to have known better than

to get sunburnt. Here, put this

in your pocket," she handed me

the tube of sunburn cream,

"maybe I'd better check up on

some of the others and make

sure they haven't forgotten."

She went off without another

word, leaving me with an unpleasant

feeling that she'd come

off best, that she considered me

an irresponsible scamp.

Forth had said almost the

same thing....

I told off the Darkovan brothers

to urge the pack animals

across the narrowest part of the

ford, and gestured to Corus and

Kyla to ride one on either side

of Kendricks, who might not be

aware of the swirling, treacherous

currents of a mountain river.

Rafe could not urge his edgy

horse into the water; he finally

dismounted, took off his boots,

and led the creature across the

slippery rocks. I crossed last, riding

close to Regis Hastur, alert

for dangers and thinking resentfully

that anyone so important

to Darkover's policies should not

be risked on such a mission.

Why, if the Terran Legate had

(unthinkably!) come with us, he

would be surrounded by bodyguards,

secret service men and

dozens of precautions against

accident, assassination or misadventure.

All that day we rode upward,

encamping at the furthest point

we could travel with pack animals

or mounted. The next day's

climb would enter the dangerous

trails we must travel afoot. We

pitched a comfortable camp, but

I admit I slept badly. Kendricks

and Lerrys and Rafe had blinding

headaches from the sun and

the thinness of the air; I was

more used to these conditions,

but I felt a sense of unpleasant

pressure, and my ears rang.

Regis arrogantly denied any discomfort,

but he moaned and

cried out continuously in his

sleep until Lerrys kicked him,

after which he was silent and,

I feared, sleepless. Kyla seemed

the least affected of any; probably

she had been at higher altitudes

more continuously than

any of us. But there were dark

circles beneath her eyes.[109]

However, no one complained as

we readied ourselves for the final

last long climb upward. If

we were fortunate, we could

cross Dammerung before nightfall;

at the very least, we

should bivouac tonight very

near the pass. Our camp had

been made at the last level spot;

we partially hobbled the pack

animals so they would not stray

too far, and left ample food for

them, and cached all but the most

necessary of light trail gear. As

we prepared to start upward on

the steep, narrow track—hardly

more than a rabbit-run—I

glanced at Kyla and stated,

"We'll work on rope from the

first stretch. Starting now."

One of the Darkovan brothers

stared at me with contempt.

"Call yourself a mountain man,

Jason? Why, my little daughter

could scramble up that track

without so much as a push on

her behind!"

I set my chin and glared at

him. "The rocks aren't easy, and

some of these men aren't used

to working on rope at all. We

might as well get used to it, because

when we start working

along the ledges, I don't want

anybody who doesn't know

how."

They still didn't like it, but

nobody protested further until I

directed the huge Kendricks to

the center of the second rope. He

glared viciously at the light nylon

line and demanded in some

apprehension, "Hadn't I better go

last until I know what I'm doing?

Hemmed in between the

two of you, I'm apt to do something

damned dumb!"

Hjalmar roared with laughter

and informed him that the center

place on a 3-man rope was

always reserved for weaklings,

novices and amateurs. I expected

Kendricks' temper to flare up:

the burly Spaceforce man and

the Darkovan giant glared at

one another, then Kendricks only

shrugged and knotted the line

through his belt. Kyla warned

Kendricks and Lerrys about

looking down from ledges, and

we started.

The first stretch was almost

too simple, a clear track winding

higher and higher for a couple

of miles. Pausing to rest for a

moment, we could turn and see

the entire valley outspread below

us. Gradually the trail grew

steeper, in spots pitched almost

at a 50-degree angle, and was

scattered with gravel, loose rock

and shale, so that we placed our

feet carefully, leaning forward

to catch at handholds and steady

ourselves against rocks. I tested

each boulder carefully, since any

weight placed against an unsteady

rock might dislodge it on

somebody below. One of the

Darkovan brothers—Vardo, I

thought—was behind me, separated

by ten or twelve feet of

slack rope, and twice when his

feet slipped on gravel he stumbled

and gave me an unpleasant

jerk. What he muttered was perfectly

true; on slopes like this,

where a fall wasn't dangerous

anyhow, it was better to work

unroped; then a slip bothered no[110]

one but the slipper. But I was

finding out what I wanted to

know—what kind of climbers I

had to lead through the Hellers.

Along a cliff face the trail narrowed

horizontally, leading

across a foot-wide ledge overhanging

a sheer drop of fifty

feet and covered with loose

shale and scrub plants. Nothing,

of course, to an experienced

climber—a foot-wide ledge

might as well be a four-lane superhighway.

Kendricks made a

nervous joke about a tightrope

walker, but when his turn came

he picked his way securely, without

losing balance. The amateurs—Lerrys

Ridenow, Regis, Rafe—came

across without hesitation,

but I wondered how well

they would have done at a less

secure altitude; to a real mountaineer,

a footpath is a footpath,

whether in a meadow, above a

two-foot drop, a thirty-foot

ledge, or a sheer mountain face

three miles above the first level

spot.

After crossing the ledge the

going was harder. A steeper