The Project Gutenberg eBook of A Book of Burlesques

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: A Book of Burlesques

Author: H. L. Mencken

Release date: July 25, 2007 [eBook #22145]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Malcolm Farmer, L. N. Yaddanapudi, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A BOOK OF BURLESQUES ***

E-text prepared by Malcolm Farmer, L. N. Yaddanapudi,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(https://www.pgdp.net)

A BOOK OF BURLESQUES

By H. L. MENCKEN

PUBLISHED AT THE BORZOI · NEW YORK · BY

ALFRED · A · KNOPF

COPYRIGHT, 1916, 1920, BY

ALFRED A. KNOPF, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER PAGE

- Death: a Philosophical Discussion 11

- From the Programme of a Concert 27

- The Wedding: a Stage Direction 51

- The Visionary 71

- The Artist: a Drama Without Words 83

- Seeing the World 105

- From the Memoirs of the Devil 135

- Litanies for the Overlooked 149

- Asepsis: a Deduction in Scherzo Form 159

- Tales of the Moral and Pathological 183

- The Jazz Webster 201

- The Old Subject 213

- Panoramas of People 223

- Homeopathics 231

- Vers Libre 237

The present edition includes some epigrams

from “A Little Book in C Major,” now out of

print. To make room for them several of the

smaller sketches in the first edition have been

omitted. Nearly the whole contents of the book

appeared originally in The Smart Set. The references

to a Europe not yet devastated by war

and an America not yet polluted by Prohibition

show that some of the pieces first saw print in

far better days than these.

H. L. M.

February 1, 1920.

I.—DEATH

I.—Death. A Philosophical

Discussion

[11]The back parlor of any average American

home. The blinds are drawn and

a single gas-jet burns feebly. A dim

suggestion of festivity: strange chairs,

the table pushed back, a decanter and glasses.

A heavy, suffocating, discordant scent of

flowers—roses, carnations, lilies, gardenias. A

general stuffiness and mugginess, as if it were

raining outside, which it isn’t.

A door leads into the front parlor. It is

open, and through it the flowers may be seen.

They are banked about a long black box with

huge nickel handles, resting upon two folding

horses. Now and then a man comes into the

front room from the street door, his shoes

squeaking hideously. Sometimes there is a

woman, usually in deep mourning. Each visitor

approaches the long black box, looks into

it with ill-concealed repugnance, snuffles softly,

and then backs of toward the door. A clock

on the mantel-piece ticks loudly. From the

[12]street come the usual noises—a wagon rattling,

the clang of a trolley car’s gong, the shrill cry

of a child.

In the back parlor six pallbearers sit upon

chairs, all of them bolt upright, with their

hands on their knees. They are in their Sunday

clothes, with stiff white shirts. Their hats

are on the floor beside their chairs. Each

wears upon his lapel the gilt badge of a fraternal

order, with a crêpe rosette. In the

gloom they are indistinguishable; all of them

talk in the same strained, throaty whisper. Between

their remarks they pause, clear their

throats, blow their noses, and shuffle in their

chairs. They are intensely uncomfortable.

Tempo: Adagio lamentoso, with occasionally a

rise to andante maesto. So:

First Pallbearer

Who woulda thought that he woulda been

the next?

Second Pallbearer

Yes; you never can tell.

Third Pallbearer

(An oldish voice, oracularly.) We’re here

to-day and gone to-morrow.

[13]Fourth Pallbearer

I seen him no longer ago than Chewsday.

He never looked no better. Nobody would

have——

Fifth Pallbearer

I seen him Wednesday. We had a glass of

beer together in the Huffbrow Kaif. He was

laughing and cutting up like he always done.

Sixth Pallbearer

You never know who it’s gonna hit next.

Him and me was pallbearers together for Hen

Jackson no more than a month ago, or say five

weeks.

First Pallbearer

Well, a man is lucky if he goes off quick.

If I had my way I wouldn’t want no better way.

Second Pallbearer

My brother John went thataway. He

dropped like a stone, settin’ there at the supper

table. They had to take his knife out of

his hand.

Third Pallbearer

I had an uncle to do the same thing, but

[14]without the knife. He had what they call appleplexy.

It runs in my family.

Fourth Pallbearer

They say it’s in his’n, too.

Fifth Pallbearer

But he never looked it.

Sixth Pallbearer

No. Nobody woulda thought he woulda

been the next.

First Pallbearer

Them are the things you never can tell anything

about.

Second Pallbearer

Ain’t it true!

Third Pallbearer

We’re here to-day and gone to-morrow.

(A pause. Feet are shuffled. Somewhere

a door bangs.)

Fourth Pallbearer[15]

(Brightly.) He looks elegant. I hear he

never suffered none.

Fifth Pallbearer

No; he went too quick. One minute he was

alive and the next minute he was dead.

Sixth Pallbearer

Think of it: dead so quick!

First Pallbearer

Gone!

Second Pallbearer

Passed away!

Third Pallbearer

Well, we all have to go some time.

Fourth Pallbearer

Yes; a man never knows but what his turn’ll

come next.

Fifth Pallbearer[16]

You can’t tell nothing by looks. Them sickly

fellows generally lives to be old.

Sixth Pallbearer

Yes; the doctors say it’s the big stout person

that goes off the soonest. They say typhord

never kills none but the healthy.

First Pallbearer

So I have heered it said. My wife’s youngest

brother weighed 240 pounds. He was as

strong as a mule. He could lift a sugar-barrel,

and then some. Once I seen him drink damn

near a whole keg of beer. Yet it finished him

in less’n three weeks—and he had it mild.

Second Pallbearer

It seems that there’s a lot of it this fall.

Third Pallbearer

Yes; I hear of people taken with it every

day. Some say it’s the water. My brother

Sam’s oldest is down with it.

Fourth Pallbearer[17]

I had it myself once. I was out of my head

for four weeks.

Fifth Pallbearer

That’s a good sign.

Sixth Pallbearer

Yes; you don’t die as long as you’re out of

your head.

First Pallbearer

It seems to me that there is a lot of sickness

around this year.

Second Pallbearer

I been to five funerals in six weeks.

Third Pallbearer

I beat you. I been to six in five weeks, not

counting this one.

Fourth Pallbearer

A body don’t hardly know what to think of

it scarcely.

Fifth Pallbearer[18]

That.rss what I always say: you can’t tell

who’ll be next.

Sixth Pallbearer

Ain’t it true! Just think of him.

First Pallbearer

Yes; nobody woulda picked him out.

Second Pallbearer

Nor my brother John, neither.

Third Pallbearer

Well, what must be must be.

Fourth Pallbearer

Yes; it don’t do no good to kick. When a

man’s time comes he’s got to go.

Fifth Pallbearer

We’re lucky if it ain’t us.

Sixth Pallbearer

So I always say. We ought to be thankful.

First Pallbearer[19]

That’s the way I always feel about it.

Second Pallbearer

It wouldn’t do him no good, no matter what

we done.

Third Pallbearer

We’re here to-day and gone to-morrow.

Fourth Pallbearer

But it’s hard all the same.

Fifth Pallbearer

It’s hard on her.

Sixth Pallbearer

Yes, it is. Why should he go?

First Pallbearer

It’s a question nobody ain’t ever answered.

Second Pallbearer

Nor never won’t.

Third Pallbearer[20]

You’re right there. I talked to a preacher

about it once, and even he couldn’t give no answer

to it.

Fourth Pallbearer

The more you think about it the less you can

make it out.

Fifth Pallbearer

When I seen him last Wednesday he had

no more ideer of it than what you had.

Sixth Pallbearer

Well, if I had my choice, that’s the way I

would always want to die.

First Pallbearer

Yes; that’s what I say. I am with you there.

Second Pallbearer

Yes; you’re right, both of you. It don’t do

no good to lay sick for months, with doctors’

bills eatin’ you up, and then have to go anyhow.

Third Pallbearer[21]

No; when a thing has to be done, the best

thing to do is to get it done and over with.

Fourth Pallbearer

That’s just what I said to my wife when I

heerd.

Fifth Pallbearer

But nobody hardly thought that he woulda

been the next.

Sixth Pallbearer

No; but that’s one of them things you can’t

tell.

First Pallbearer

You never know who’ll be the next.

Second Pallbearer

It’s lucky you don’t.

Third Pallbearer

I guess you’re right.

Fourth Pallbearer[22]

That’s what my grandfather used to say:

you never know what is coming.

Fifth Pallbearer

Yes; that’s the way it goes.

Sixth Pallbearer

First one, and then somebody else.

First Pallbearer

Who it’ll be you can’t say.

Second Pallbearer

I always say the same: we’re here to-day——

Third Pallbearer

(Cutting in jealousy and humorously.) And

to-morrow we ain’t here.

(A subdued and sinister snicker. It is followed

by sudden silence. There is a shuffling

of feet in the front room, and whispers. Necks

[23]are craned. The pallbearers straighten their

backs, hitch their coat collars and pull on their

black gloves. The clergyman has arrived.

From above comes the sound of weeping.)

[25]

II.—FROM THE PROGRAMME

OF A

CONCERT

II.—From The Programme of a

Concert

[27]

"Ruhm und Ewigkeit" (Fame and Eternity),

a symphonic poem in B flat minor, Opus

48, by Johann Sigismund Timotheus Albert

Wolfgang Kraus (1872- ).

Kraus, like his eminent compatriot,

Dr. Richard Strauss, has gone to

Friedrich Nietzsche, the laureate of

the modern German tone-art, for his

inspiration in this gigantic work. His text is

to be found in Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo, which

was not published until after the poet’s death,

but the composition really belongs to Also

sprach Zarathustra, as a glance will show:

I

Wie lange sitzest du schon

auf deinem Missgeschick?

Gieb Acht! Du brütest mir noch

ein Ei,

ein Basilisken-Ei,

aus deinem langen Jammer aus.

[28]

II

Was schleicht Zarathustra entlang dem Berge?—

III

Misstrauisch, geschwürig, düster,

ein langer Lauerer,—

aber plötzlich, ein Blitz,

hell, furchtbar, ein Schlag

gen Himmel aus dem Abgrund:

—dem Berge selber schüttelt sich

das Eingeweide....

IV

Wo Hass und Blitzstrahl

Eins ward, ein Fluch,—

auf den Bergen haust jetzt Zarathustra’s Zorn,

eine Wetterwolke schleicht er seines Wegs.

V

Verkrieche sich, wer eine letzte Decke hat!

In’s Bett mit euch, ihr Zärtlinge!

Nun rollen Donner über die Gewölbe,

nun zittert, was Gebälk und Mauer ist,

nun zucken Blitze und schwefelgelbe Wahrheiten—

Zarathustra flucht ...!

For the following faithful and graceful

translation the present commentator is indebted

to Mr. Louis Untermeyer:

[29]

I

How long brood you now

On thy disaster?

Give heed! You hatch me soon

An egg,

From your long lamentation out of.

II

Why prowls Zarathustra among the mountains?

III

Distrustful, ulcerated, dismal,

A long waiter—

But suddenly a flash,

Brilliant, fearful. A lightning stroke

Leaps to heaven from the abyss:

—The mountains shake themselves and

Their intestines....

IV

As hate and lightning-flash

Are united, a curse!

On the mountains rages now Zarathustra’s wrath,

Like a thunder cloud rolls it on its way.

V

Crawl away, ye who have a roof remaining!

To bed with you, ye tenderlings!

[30]Now thunder rolls over the great arches,

Now tremble the bastions and battlements,

Now flashes palpitate and sulphur-yellow truths—

Zarathustra swears ...!

The composition is scored for three flutes,

one piccolo, one bass piccolo, seven oboes,

one English horn, three clarinets in D flat, one

clarinet in G flat, one corno de bassetto, three

bassoons, one contra-bassoon, eleven horns,

three trumpets, eight cornets in B, four trombones,

two alto trombones, one viol da gamba,

one mandolin, two guitars, one banjo, two tubas,

glockenspiel, bell, triangle, fife, bass-drum,

cymbals, timpani, celesta, four harps, piano,

harmonium, pianola, phonograph, and the

usual strings.

At the opening a long B flat is sounded by

the cornets, clarinets and bassoons in unison,

with soft strokes upon a kettle-drum tuned to

G sharp. After eighteen measures of this,

singhiozzando, the strings enter pizzicato with

a figure based upon one of the scales of the ancient

Persians—B flat, C flat, D, E sharp, G

and A flat—which starts high among the first

violins, and then proceeds downward, through

the second violins, violas and cellos, until it is

lost in solemn and indistinct mutterings in the

double-basses. Then, the atmosphere of doom

[31]having been established, and the conductor having

found his place in the score, there is heard

the motive of brooding, or as the German commentators

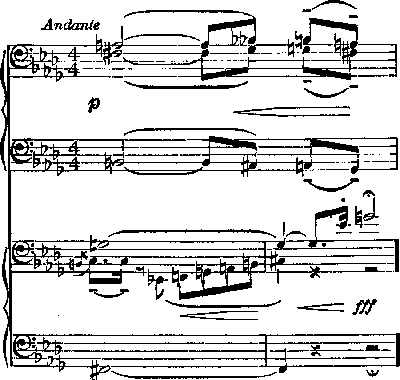

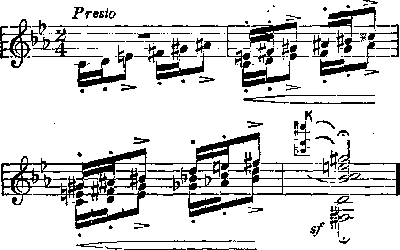

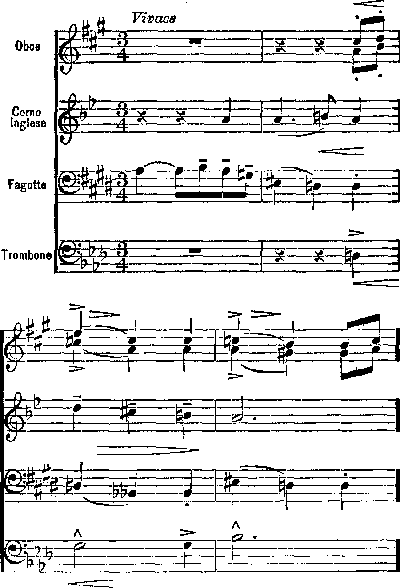

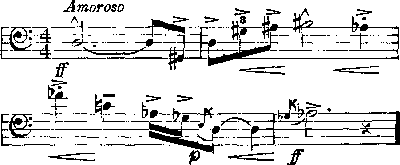

call it, the Quälerei Motiv:

The opening chord of the eleventh is sounded

by six horns, and the chords of the ninth,

which follow, are given to the woodwind. The

rapid figure in the second measure is for solo

violin, heard softly against the sustained interval

of the diminished ninth, but the final G natural

is snapped out by the whole orchestra

[32]sforzando. There follows a rapid and daring

development of the theme, with the flutes

and violoncellos leading, first harmonized with

chords of the eleventh, then with chords of the

thirteenth, and finally with chords of the fifteenth.

Meanwhile, the tonality has moved

into D minor, then into A flat major, and then

into G sharp minor, and the little arpeggio for

the solo violin has been augmented to seven, to

eleven, and in the end to twenty-three notes.

Here the influence of Claude Debussy shows itself;

the chords of the ninth proceed by the

same chromatic semitones that one finds in the

Chansons de Bilitis. But Kraus goes much further

than Debussy, for the tones of his chords

are constantly altered in a strange and extremely

beautiful manner, and, as has been noted,

he adds the eleventh, thirteenth and fifteenth.

At the end of this incomparable passage there

is a sudden drop to C major, followed by the

first statement of the Missgeschick Motiv, or

motive of disaster (misfortune, evil destiny, untoward

fate):

[33]

This graceful and ingratiating theme will

give no concern to the student of Ravel and

Schoenberg. It is, in fact, a quite elemental

succession of intervals of the second, all produced

by adding the ninth to the common

chord—thus: C, G, C, D, E—with certain enharmonic

changes. Its simplicity gives it, at a

first hearing, a placid, pastoral aspect, somewhat

disconcerting to the literalist, but the discerning

will not fail to note the mutterings beneath

the surface. It is first sounded by two

violas and the viol da gamba, and then drops

without change to the bass, where it is repeated

fortissimo by two bassoons and the contra-bassoon.

The tempo then quickens and the two

themes so far heard are worked up into a brief

but tempestuous fugue. A brief extract will

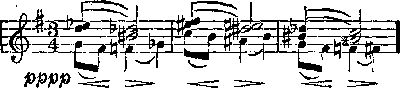

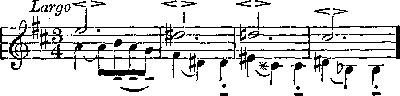

suffice to show its enormously complex nature:

[34]A pedal point on B flat is heard at the end

of this fugue, sounded fortissimo by all the

brass in unison, and then follows a grand pause,

twelve and a half measures in length. Then,

in the strings, is heard the motive of warning:

[35]Out of this motive comes the harmonic material

for much of what remains of the composition.

At each repetition of the theme, the

chord in the fourth measure is augmented by

the addition of another interval, until in the

end it includes every tone of the chromatic scale

save C sharp. This omission is significant of

Kraus’ artistry. If C sharp were included the

tonality would at once become vague, but without

it the dependence of the whole gorgeous edifice

upon C major is kept plain. At the end,

indeed, the tonic chord of C major is clearly

sounded by the wood-wind, against curious triplets,

made up of F sharp, A flat and B flat in

various combinations, in the strings; and from

it a sudden modulation is made to C minor, and

then to A flat major. This opens the way for

the entrance of the motive of lamentation, or,

as the German commentators call it, the Schreierei

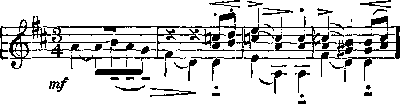

Motiv:

This simple and lovely theme is first sounded,

not by any of the usual instruments of the

grand orchestra, but by a phonograph in B flat,

with the accompaniment of a solitary trombone.

[36]When the composition was first played at the

Gewandhaus in Leipzig the innovation caused

a sensation, and there were loud cries of sacrilege

and even proposals of police action. One

indignant classicist, in token of his ire, hung

a wreath of Knackwürste around the neck of

the bust of Johann Sebastian Bach in the Thomaskirche,

and appended to it a card bearing the

legend, Schweinehund! But the exquisite beauty

of the effect soon won acceptance for the means

employed to attain it, and the phonograph has

so far made its way with German composers

that Prof. Ludwig Grossetrommel, of Göttingen,

has even proposed its employment in

opera in place of singers.

This motive of lamentation is worked out

on a grand scale, and in intimate association

with the motives of brooding and of warning.

Kraus is not content with the ordinary materials

of composition. His creative force is always

impelling him to break through the fetters

of the diatonic scale, and to find utterance

for his ideas in archaic and extremely exotic

tonalities. The pentatonic scale is a favorite

with him; he employs it as boldly as Wagner

did in Das Rheingold. But it is not enough,

for he proceeds from it into the Dorian mode

of the ancient Greeks, and then into the Phrygian,

[37]and then into two of the plagal modes.

Moreover, he constantly combines both unrelated

scales and antagonistic motives, and invests

the combinations in astounding orchestral

colors, so that the hearer, unaccustomed to

such bold experimentations, is quite lost in the

maze. Here, for example, is a characteristic

passage for solo French horn and bass piccolo:

The dotted half notes for the horn obviously

come from the motive of brooding, in

augmentation, but the bass piccolo part is new.

It soon appears, however, in various fresh aspects,

and in the end it enters into the famous

quadruple motive of “sulphur-yellow truth”—schwefelgelbe

Wahrheit, as we shall presently

see. Its first combination is with a jaunty figure

in A minor, and the two together form what

most of the commentators agree upon denominating

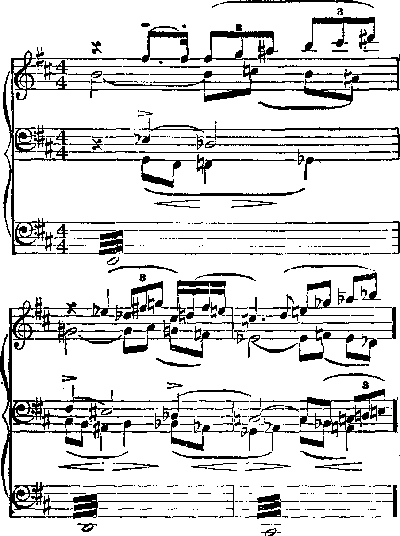

the Zarathustra motive:

[38]I call this the Zarathustra motive, following

the weight of critical opinion, but various influential

critics dissent. Thus, Dr. Ferdinand

Bierfisch, of the Hochschule für Musik at Dresden,

insists that it is the theme of “the elevated

mood produced by the spiritual isolation and

low barometric pressure of the mountains,”

while Prof. B. Moll, of Frankfurt a/M., calls

it the motive of prowling. Kraus himself,

when asked by Dr. Fritz Bratsche, of the Berlin

Volkszeitung, shrugged his shoulders and

answered in his native Hamburg dialect, “So

gehts im Leben! ’S giebt gar kein Use”—Such

is life; it gives hardly any use (to inquire?).

In much the same way Schubert made

reply to one who asked the meaning of the

opening subject of the slow movement of his

C major symphony: “Halt’s Maul, du verfluchter

Narr!”—Don’t ask such question, my

dear sir!

But whatever the truth, the novelty and originality

of the theme cannot be denied, for it is

in two distinct keys, D major and A minor,

and they preserve their identity whenever it

appears. The handling of two such diverse tonalities

at one time would present insuperable

difficulties to a composer less ingenious than

Kraus, but he manages it quite simply by founding

[39]his whole harmonic scheme upon the tonic

triad of D major, with the seventh and ninth

added. He thus achieves a chord which also

contains the tonic triad of A minor. The same

thing is now done with the dominant triads, and

half the battle is won. Moreover, the instrumentation

shows the same boldness, for the

double theme is first given to three solo violins,

and they are muted in a novel and effective

manner by stopping their F holes. The directions

in the score say mit Glaserkitt (that is,

with glazier’s putty), but the Konzertmeister

at the Gewandhaus, Herr F. Dur, substituted

ordinary pumpernickel with excellent results.

It is, in fact, now commonly used in the German

orchestras in place of putty, for it does

less injury to the varnish of the violins, and,

besides, it is edible after use. It produces a

thick, oily, mysterious, far-away effect.

At the start, as I have just said, the double

theme of Zarathustra appears in D major and

A minor, but there is quick modulation to B

flat major and C sharp minor, and then to C

major and F sharp minor. Meanwhile the

tempo gradually accelerates, and the polyphonic

texture is helped out by reminiscences of the

themes of brooding and of lamentation. A sudden

hush and the motive of warning is heard

[40]high in the wood-wind, in C flat major, against

a double organ-point—C natural and C sharp—in

the lower strings. There follows a cadenza

of no less than eighty-four measures for

four harps, tympani and a single tuba, and

then the motive of waiting is given out by the

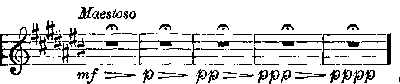

whole orchestra in unison:

This stately motive is repeated in F major,

after which some passage work for the piano

and pianola, the former tuned a quarter tone

lower than the latter and played by three performers,

leads directly into the quadruple

theme of the sulphur-yellow truth, mentioned

above. It is first given out by two oboes divided,

a single English horn, two bassoons in

unison, and four trombones in unison. It is

an extraordinarily long motive, running to

twenty-seven measures on its first appearance;

the four opening measures are given on the

next page.

With an exception yet to be noted, all of the

composer’s thematic material is now set forth,

and what follows is a stupendous development

of it, so complex that no written description

[41]could even faintly indicate its character. The

quadruple theme of the sulphur-yellow truth is

sung almost uninterruptedly, first by the wood-wind,

[42]then by the strings and then by the full

brass choir, with the glockenspiel and cymbals

added. Into it are woven all of the other

themes in inextricable whirls and whorls of

sound, and in most amazing combinations and

permutations of tonalities. Moreover, there is

a constantly rising complexity of rhythm, and

on one page of the score the time signature is

changed no less than eighteen times. Several

times it is 5-8 and 7-4; once it is 11-2; in one

place the composer, following Koechlin and

Erik Satie, abandons bar-lines altogether for

half a page of the score. And these diverse

rhythms are not always merely successive;

sometimes they are heard together. For example,

the motive of disaster, augmented to 5-8

time, is sounded clearly by the clarinets against

the motive of lamentation in 3-4 time, and

through it all one hears the steady beat of the

motive of waiting in 4-4!

This gigantic development of materials is

carried to a thrilling climax, with the whole

orchestra proclaiming the Zarathustra motive

fortissimo. Then follows a series of arpeggios

for the harps, made of the motive of warning,

and out of them there gradually steals the tonic

triad of D minor, sung by three oboes. This

chord constitutes the backbone of all that follows.

[43]The three oboes are presently joined by

a fourth. Against this curtain of tone the flutes

and piccolos repeat the theme of brooding in

F major, and then join the oboes in the D minor

chord. The horns and bassoons follow with

the motive of disaster and then do likewise.

Now come the violins with the motive of lamentation,

but instead of ending with the D

minor tonic triad, they sound a chord of the

seventh erected on C sharp as seventh of D

minor. Every tone of the scale of D minor

is now being sounded, and as instrument after

instrument joins in the effect is indescribably

sonorous and imposing. Meanwhile, there is

a steady crescendo, ending after three minutes

of truly tremendous music with ten sharp blasts

of the double chord. A moment of silence and

a single trombone gives out a theme hitherto

not heard. It is the theme of tenderness, or,

as the German commentators call it, the Biermad’l

Motiv: Thus:

[44]Again silence. Then a single piccolo plays

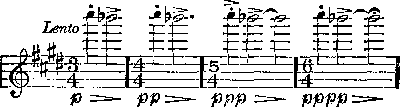

the closing cadence of the composition:

Ruhm und Ewigkeit presents enormous difficulties

to the performers, and taxes the generalship

of the most skillful conductor. When

it was in preparation at the Gewandhaus the

first performance was postponed twelve times

in order to extend the rehearsals. It was reported

in the German papers at the time that

ten members of the orchestra, including the first

flutist, Ewald Löwenhals, resigned during the

rehearsals, and that the intervention of the

King of Saxony was necessary to make them

reconsider their resignations. One of the second

violins, Hugo Zehndaumen, resorted to

stimulants in anticipation of the opening performance,

and while on his way to the hall was

run over by a taxicab. The conductor was

Nikisch. A performance at Munich followed,

and on May 1, 1913, the work reached Berlin.

At the public rehearsal there was a riot led by

members of the Bach Gesellschaft, and the hall

was stormed by the mounted police. Many arrests

[45]were made, and five of the rioters were

taken to hospital with serious injuries. The

work was put into rehearsal by the Boston Symphony

Orchestra in 1914. The rehearsals have

been proceeding ever since. A piano transcription

for sixteen hands has been published.

Kraus was born at Hamburg on January

14, 1872. At the age of three he performed

creditably on the zither, cornet and trombone,

and by 1877 he had already appeared in concert

at Danzig. His family was very poor, and

his early years were full of difficulties. It is

said that, at the age of nine, he copied the

whole score of Wagner’s Ring, the scores of

the nine Beethoven symphonies and the complete

works of Mozart. His regular teacher,

in those days, was Stadtpfeifer Schmidt, who

instructed him in piano and thorough-bass. In

1884, desiring to have lessons in counterpoint

from Prof. Kalbsbraten, of Mainz, he walked

to that city from Hamburg once a week—a distance

for the round trip of 316 miles. In 1887

he went to Berlin and became fourth cornetist

of the Philharmonic Orchestra and valet to

Dr. Schweinsrippen, the conductor. In Berlin

he studied violin and second violin under the

Polish virtuoso, Pbyschbrweski, and also had

[46]lessons in composition from Wilhelm Geigenheimer,

formerly third triangle and assistant

librarian at Bayreuth.

His first composition, a march for cornet,

violin and piano, was performed on July 18,

1888, at the annual ball of the Arbeiter Liedertafel

in Berlin. It attracted little attention,

but six months later the young composer made

musical Berlin talk about him by producing a

composition called Adenoids, for twelve tenors,

a cappella, to words by Otto Julius Bierbaum.

This was first heard at an open air concert

given in the Tiergarten by the Sozialist Liederkranz.

It was soon after repeated by the choir

of the Gottesgelehrheitsakademie, and Kraus

found himself a famous young man. His string

quartet in G sharp minor, first played early in

1889 by the quartet led by Prof. Rudolph

Wurst, added to his growing celebrity, and

when his first tone poem for orchestra, Fuchs,

Du Hast die Gans Gestohlen, was done by the

Philharmonic in the autumn of 1889, under Dr.

Lachschinken, it was hailed with acclaim.

Kraus has since written twelve symphonies

(two choral), nine tone-poems, a suite for brass

and tympani, a trio for harp, tuba and glockenspiel,

ten string quartettes, a serenade for flute

[47]and contra-bassoon, four concert overtures, a

cornet concerto, and many songs and piano

pieces. His best-known work, perhaps, is his

symphony in F flat major, in eight movements.

But Kraus himself is said to regard this huge

work as trivial. His own favorite, according

to his biographer, Dr. Linsensuppe, is Ruhm

und Ewigkeit, though he is also fond of the

tone-poem which immediately preceded it,

Rinderbrust und Meerrettig. He has written

a choral for sixty trombones, dedicated to Field

Marshal von Hindenburg, and is said to be

at work on a military mass for four orchestras,

seven brass bands and ten choirs, with the usual

soloists and clergy. Among his principal

works are Der Ewigen Wiederkunft (a ten

part fugue for full orchestra), Biergemütlichkeit,

his Oberkellner and Uebermensch concert

overtures, and his setting (for mixed chorus)

of the old German hymn:

Saufst—stirbst!

Saufst net—stirbst a!

Also, saufst!

Kraus is now a resident of Munich, where

he conducts the orchestra at the Löwenbräuhaus.

He has been married eight times and

is at present the fifth husband of Tilly Heintz,

[48]the opera singer. He has been decorated by

the Kaiser, by the King of Sweden and by the

Sultan of Turkey, and is a member of the German

Odd Fellows.

[49]

III.—THE WEDDING

III.—The Wedding. A Stage

Direction

[51]The scene is a church in an American

city of about half a million population,

and the time is about eleven

o’clock of a fine morning in early

spring. The neighborhood is well-to-do, but

not quite fashionable. That is to say, most of

the families of the vicinage keep two servants

(alas, more or less intermittently!), and eat

dinner at half-past six, and about one in every

four boasts a colored butler (who attends to

the fires, washes windows and helps with the

sweeping), and a last year’s automobile. The

heads of these families are merchandise brokers;

jobbers in notions, hardware and drugs;

manufacturers of candy, hats, badges, office furniture,

blank books, picture frames, wire goods

and patent medicines; managers of steamboat

lines; district agents of insurance companies;

owners of commercial printing offices, and other

such business men of substance—and the prosperous

lawyers and popular family doctors who

[52]keep them out of trouble. In one block live

a Congressman and two college professors, one

of whom has written an unimportant textbook

and got himself into “Who’s Who in America.”

In the block above lives a man who once ran

for Mayor of the city, and came near being

elected.

The wives of these householders wear good

clothes and have a liking for a reasonable gayety,

but very few of them can pretend to what

is vaguely called social standing, and, to do

them justice, not many of them waste any time

lamenting it. They have, taking one with another,

about three children apiece, and are good

mothers. A few of them belong to women’s

clubs or flirt with the suffragettes, but the majority

can get all of the intellectual stimulation

they crave in the Ladies’ Home Journal and the

Saturday Evening Post, with Vogue added for

its fashions. Most of them, deep down in their

hearts, suspect their husbands of secret frivolity,

and about ten per cent. have the proofs, but

it is rare for them to make rows about it, and

the divorce rate among them is thus very low.

Themselves indifferent cooks, they are unable

to teach their servants the art, and so the food

they set before their husbands and children is

often such as would make a Frenchman cut

[53]his throat. But they are diligent housewives

otherwise; they see to it that the windows are

washed, that no one tracks mud into the hall,

that the servants do not waste coal, sugar, soap

and gas, and that the family buttons are always

sewed on. In religion these estimable wives

are pious in habit but somewhat nebulous in

faith. That is to say, they regard any person

who specifically refuses to go to church as a

heathen, but they themselves are by no means

regular in attendance, and not one in ten of

them could tell you whether transubstantiation

is a Roman Catholic or a Dunkard doctrine.

About two per cent. have dallied more or less

gingerly with Christian Science, their average

period of belief being one year.

The church we are in is like the neighborhood

and its people: well-to-do but not fashionable.

It is Protestant in faith and probably

Episcopalian. The pews are of thick, yellow-brown

oak, severe in pattern and hideous in

color. In each there is a long, removable cushion

of a dark, purplish, dirty hue, with here and

there some of its hair stuffing showing. The

stained-glass windows, which were all bought

ready-made and depict scenes from the New

Testament, commemorate the virtues of departed

worthies of the neighborhood, whose

[54]names appear, in illegible black letters, in the

lower panels. The floor is covered with a carpet

of some tough, fibrous material, apparently

a sort of grass, and along the center aisle it is

much worn. The normal smell of the place is

rather less unpleasant than that of most other

halls, for on the one day when it is regularly

crowded practically all of the persons gathered

together have been very recently bathed.

On this fine morning, however, it is full of

heavy, mortuary perfumes, for a couple of florist’s

men have just finished decorating the chancel

with flowers and potted palms. Just behind

the chancel rail, facing the center aisle,

there is a prie-dieu, and to either side of it are

great banks of lilies, carnations, gardenias and

roses. Three or four feet behind the prie-dieu

and completely concealing the high altar, there

is a dense jungle of palms. Those in the front

rank are authentically growing in pots, but behind

them the florist’s men have artfully placed

some more durable, and hence more profitable,

sophistications. Anon the rev. clergyman,

emerging from the vestry-room to the right,

will pass along the front of this jungle to the

prie-dieu, and so, framed in flowers, face the

congregation with his saponaceous smile.

The florist’s men, having completed their labors,

[55]are preparing to depart. The older of

the two, a man in the fifties, shows the ease

of an experienced hand by taking out a large

plug of tobacco and gnawing off a substantial

chew. The desire to spit seizing him shortly,

he proceeds to gratify it by a trick long practised

by gasfitters, musicians, caterer’s helpers,

piano movers and other such alien invaders of

the domestic hearth. That is to say, he hunts

for a place where the carpet is loose along the

chancel rail, finds it where two lengths join,

deftly turns up a flap, spits upon the bare floor,

and then lets the flap fall back, finally giving

it a pat with the sole of his foot. This done,

he and his assistant leave the church to the

sexton, who has been sweeping the vestibule,

and, after passing the time of day with the two

men who are putting up a striped awning from

the door to the curb, disappear into a nearby

speak-easy, there to wait and refresh themselves

until the wedding is over, and it is time to take

away their lilies, their carnations and their synthetic

palms.

It is now a quarter past eleven, and two flappers

of the neighborhood, giggling and arm-in-arm,

approach the sexton and inquire of him

if they may enter. He asks them if they have

tickets and when they say they haven’t, he tells

[56]them that he ain’t got no right to let them in,

and don’t know nothing about what the rule is

going to be. At some weddings, he goes on,

hardly nobody ain’t allowed in, but then again,

sometimes they don’t scarcely look at the tickets

at all. The two flappers retire abashed, and as

the sexton finishes his sweeping, there enters the

organist.

The organist is a tall, thin man of melancholy,

uræmic aspect, wearing a black slouch hat

with a wide brim and a yellow overcoat that

barely reaches to his knees. A pupil, in his

youth, of a man who had once studied (irregularly

and briefly) with Charles-Marie Widor,

he acquired thereby the artistic temperament,

and with it a vast fondness for malt liquor.

His mood this morning is acidulous and depressed,

for he spent yesterday evening in a

Pilsner ausschank with two former members

of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and it was

3 A. M. before they finally agreed that Johann

Sebastian Bach, all things considered, was a

greater man than Beethoven, and so parted

amicably. Sourness is the precise sensation

that wells within him. He feels vinegary; his

blood runs cold; he wishes he could immerse

himself in bicarbonate of soda. But the call

of his art is more potent than the protest of

[57]his poisoned and quaking liver, and so he manfully

climbs the spiral stairway to his organ-loft.

Once there, he takes off his hat and overcoat,

stoops down to blow the dust off the organ keys,

throws the electrical switch which sets the bellows

going, and then proceeds to take off his

shoes. This done, he takes his seat, reaches

for the pedals with his stockinged feet, tries an

experimental 32-foot CCC, and then wanders

gently into a Bach toccata. It is his limbering-up

piece: he always plays it as a prelude to a

wedding job. It thus goes very smoothly and

even brilliantly, but when he comes to the end

of it and tackles the ensuing fugue he is quickly

in difficulties, and after four or five stumbling

repetitions of the subject he hurriedly improvises

a crude coda and has done. Peering down

into the church to see if his flounderings have

had an audience, he sees two old maids enter,

the one very tall and thin and the other somewhat

brisk and bunchy.

They constitute the vanguard of the nuptial

throng, and as they proceed hesitatingly up the

center aisle, eager for good seats but afraid to

go too far, the organist wipes his palms upon

his trousers legs, squares his shoulders, and

plunges into the program that he has played at

[58]all weddings for fifteen years past. It begins

with Mendelssohn’s Spring Song, pianissimo.

Then comes Rubinstein’s Melody in F, with a

touch of forte toward the close, and then

Nevin’s “Oh, That We Two Were Maying”

and then the Chopin waltz in A flat, Opus 69,

No. 1, and then the Spring Song again, and

then a free fantasia upon “The Rosary” and

then a Moszkowski mazurka, and then the

Dvorák Humoresque (with its heart-rending

cry in the middle), and then some vague and

turbulent thing (apparently the disjecta membra

of another fugue), and then Tschaikowsky’s

“Autumn,” and then Elgar’s “Salut d’Amour,”

and then the Spring Song a third

time, and then something or other from one

of the Peer Gynt suites, and then an hurrah or

two from the Hallelujah chorus, and then

Chopin again, and Nevin, and Elgar, and——

But meanwhile, there is a growing activity

below. First comes a closed automobile bearing

the six ushers and soon after it another automobile

bearing the bridegroom and his best

man. The bridegroom and the best man disembark

before the side entrance of the church

and make their way into the vestry room, where

they remove their hats and coats, and proceed

to struggle with their cravats and collars before

[59]a mirror which hangs on the wall. The

room is very dingy. A baize-covered table is

in the center of it, and around the table stand

six or eight chairs of assorted designs. One

wall is completely covered by a bookcase,

through the glass doors of which one may discern

piles of cheap Bibles, hymn-books and

back numbers of the parish magazine. In one

corner is a small washstand. The best man

takes a flat flask of whiskey from his pocket,

looks about him for a glass, finds it on the

washstand, rinses it at the tap, fills it with a policeman’s

drink, and hands it to the bridegroom.

The latter downs it at a gulp. Then the best

man pours out one for himself.

The ushers, reaching the vestibule of the

church, have handed their silk hats to the sexton,

and entered the sacred edifice. There

was a rehearsal of the wedding last night, but

after it was over the bride ordered certain incomprehensible

changes in the plan, and the

ushers are now completely at sea. All they

know clearly is that the relatives of the bride

are to be seated on one side and the relatives

of the bridegroom on the other. But which

side for one and which for the other? They

discuss it heatedly for three minutes and then

find that they stand three for putting the bride’s

[60]relatives on the left side and three for putting

them on the right side. The debate, though instructive,

is interrupted by the sudden entrance

of seven women in a group. They are headed

by a truculent old battleship, possibly an aunt

or something of the sort, who fixes the nearest

usher with a knowing, suspicious glance, and

motions to him to show her the way.

He offers her his right arm and they start

up the center aisle, with the six other women

following in irregular order, and the five other

ushers scattered among the women. The leading

usher is tortured damnably by doubts as

to where the party should go. If they are

aunts, to which house do they belong, and on

which side are the members of that house to be

seated? What if they are not aunts, but merely

neighbors? Or perhaps an association of

former cooks, parlor maids, nurse girls? Or

strangers? The sufferings of the usher are

relieved by the battleship, who halts majestically

about twenty feet from the altar, and

motions her followers into a pew to the left.

They file in silently and she seats herself next

the aisle. All seven settle back and wriggle

for room. It is a tight fit.

(Who, in point of fact, are these ladies?

Don’t ask the question! The ushers never

[61]find out. No one ever finds out. They

remain a joint mystery for all time. In

the end they become a sort of tradition, and

years hence, when two of the ushers meet, they

will cackle over old dreadnaught and her six

cruisers. The bride, grown old and fat, will

tell the tale to her daughter, and then to her

granddaughter. It will grow more and more

strange, marvelous, incredible. Variorum versions

will spring up. It will be adapted to

other weddings. The dreadnaught will become

an apparition, a witch, the Devil in skirts.

And as the years pass, the date of the episode

will be pushed back. By 2017 it will be dated

1150. By 2475 it will take on a sort of sacred

character, and there will be a footnote referring

to it in the latest Revised Version of the

New Testament.)

It is now a quarter to twelve, and of a sudden

the vestibule fills with wedding guests.

Nine-tenths of them, perhaps even nineteen-twentieths,

are women, and most of them are

beyond thirty-five. Scattered among them,

hanging on to their skirts, are about a dozen

little girls—one of them a youngster of eight

or thereabout, with spindle shanks and shining

morning face, entranced by her first wedding.

Here and there lurks a man. Usually he wears

[62]a hurried, unwilling, protesting look. He has

been dragged from his office on a busy morning,

forced to rush home and get into his cut-away

coat, and then marched to the church by

his wife. One of these men, much hustled,

has forgotten to have his shoes shined. He

is intensely conscious of them, and tries to

hide them behind his wife’s skirt as they walk

up the aisle. Accidentally he steps upon it,

and gets a look over the shoulder which lifts

his diaphragm an inch and turns his liver to

water. This man will be courtmartialed when

he reaches home, and he knows it. He wishes

that some foreign power would invade the

United States and burn down all the churches

in the country, and that the bride, the bridegroom

and all the other persons interested in

the present wedding were dead and in hell.

The ushers do their best to seat these wedding

guests in some sort of order, but after

a few minutes the crowd at the doors becomes

so large that they have to give it up, and thereafter

all they can do is to hold out their right

arms ingratiatingly and trust to luck. One of

them steps on a fat woman’s skirt, tearing it

very badly, and she has to be helped back to

the vestibule. There she seeks refuge in a

corner, under a stairway leading up to the steeple,

[63]and essays to repair the damage with pins

produced from various nooks and crevices of

her person. Meanwhile the guilty usher stands

in front of her, mumbling apologies and trying

to look helpful. When she finishes her

work and emerges from her improvised dry-dock,

he again offers her his arm, but she

sweeps past him without noticing him, and proceeds

grandly to a seat far forward. She is

a cousin to the bride’s mother, and will make

a report to every branch of the family that all

six ushers disgraced the ceremony by appearing

at it far gone in liquor.

Fifteen minutes are consumed by such episodes

and divertisements. By the time the

clock in the steeple strikes twelve the church

is well filled. The music of the organist, who

has now reached Mendelssohn’s Spring Song

for the third and last time, is accompanied by

a huge buzz of whispers, and there is much

craning of necks and long-distance nodding and

smiling. Here and there an unusually gorgeous

hat is the target of many converging

glances, and of as many more or less satirical

criticisms. To the damp funeral smell of the

flowers at the altar, there has been added the

cacodorous scents of forty or fifty different

brands of talcum and rice powder. It begins

[64]to grow warm in the church, and a number of

women open their vanity bags and duck down

for stealthy dabs at their noses. Others, more

reverent, suffer the agony of augmenting shines.

One, a trickster, has concealed powder in her

pocket handkerchief, and applies it dexterously

while pretending to blow her nose.

The bridegroom in the vestry-room, entering

upon the second year (or is it the third?)

of his long and ghastly wait, grows increasingly

nervous, and when he hears the organist

pass from the Spring Song into some more

sonorous and stately thing he mistakes it for

the wedding march from “Lohengrin,” and is

hot for marching upon the altar at once. The

best man, an old hand, restrains him gently,

and administers another sedative from the bottle.

The bridegroom’s thoughts turn to gloomy

things. He remembers sadly that he will never

be able to laugh at benedicts again; that his

days of low, rabelaisian wit and care-free scoffing

are over; that he is now the very thing

he mocked so gaily but yesteryear. Like a

drowning man, he passes his whole life in review—not,

however, that part which is past,

but that part which is to come. Odd fancies

throng upon him. He wonders what his honeymoon

will cost him, what there will be to drink

[65]at the wedding breakfast, what a certain girl

in Chicago will say when she hears of his marriage.

Will there be any children? He rather

hopes not, for all those he knows appear so

greasy and noisy, but he decides that he might

conceivably compromise on a boy. But how

is he going to make sure that it will not be a

girl? The thing, as yet, is a medical impossibility—but

medicine is making rapid strides.

Why not wait until the secret is discovered?

This sapient compromise pleases the bridegroom,

and he proceeds to a consideration of

various problems of finance. And then, of a

sudden, the organist swings unmistakably into

“Lohengrin” and the best man grabs him by

the arm.

There is now great excitement in the church.

The bride’s mother, two sisters, three brothers

and three sisters-in-law have just marched up

the center aisle and taken seats in the front

pew, and all the women in the place are craning

their necks toward the door. The usual

electrical delay ensues. There is something the

matter with the bride’s train, and the two

bridesmaids have a deuce of a time fixing it.

Meanwhile the bride’s father, in tight pantaloons

and tighter gloves, fidgets and fumes in

the vestibule, the six ushers crowd about him

[66]inanely, and the sexton rushes to and fro like

a rat in a trap. Finally, all being ready, with

the ushers formed two abreast, the sexton

pushes a button, a small buzzer sounds in the

organ loft, and the organist, as has been said,

plunges magnificently into the fanfare of the

"Lohengrin" march. Simultaneously the sexton

opens the door at the bottom of the main

aisle, and the wedding procession gets under

weigh.

The bride and her father march first. Their

step is so slow (about one beat to two measures)

that the father has some difficulty in

maintaining his equilibrium, but the bride herself

moves steadily and erectly, almost seeming

to float. Her face is thickly encrusted with

talcum in its various forms, so that she is almost

a dead white. She keeps her eyelids lowered

modestly, but is still acutely aware of

every glance fastened upon her—not in the

mass, but every glance individually. For example,

she sees clearly, even through her eyelids,

the still, cold smile of a girl in Pew 8 R—a

girl who once made an unwomanly attempt

upon the bridegroom’s affections, and was routed

and put to flight by superior strategy. And

her ears are open, too: she hears every “How

sweet!” and “Oh, lovely!” and “Ain’t she

[67]pale!” from the latitude of the last pew to the

very glacis of the altar of God.

While she has thus made her progress up

the hymeneal chute, the bridegroom and his

best man have emerged from the vestryroom

and begun the short march to the prie-dieu.

They walk haltingly, clumsily, uncertainly,

stealing occasional glances at the advancing

bridal party. The bridegroom feels of his

lower right-hand waistcoat pocket; the ring

is still there. The best man wriggles his cuffs.

No one, however, pays any heed to them. They

are not even seen, indeed, until the bride and

her father reach the open space in front of the

altar. There the bride and the bridegroom

find themselves standing side by side, but not a

word is exchanged between them, nor even a

look of recognition. They stand motionless,

contemplating the ornate cushion at their feet,

until the bride’s father and the bridesmaids file

to the left of the bride and the ushers, now

wholly disorganized and imbecile, drape themselves

in an irregular file along the altar rail.

Then, the music having died down to a faint

murmur and a hush having fallen upon the assemblage,

they look up.

Before them, framed by foliage, stands the

reverend gentleman of God who will presently

[68]link them in indissoluble chains—the estimable

rector of the parish. He has got there just in

time; it was, indeed, a close shave. But no

trace of haste or of anything else of a disturbing

character is now visible upon his smooth,

glistening, somewhat feverish face. That face

is wholly occupied by his official smile, a thing

of oil and honey all compact, a balmy, unctuous

illumination—the secret of his success in life.

Slowly his cheeks puff out, gleaming like soap-bubbles.

Slowly he lifts his prayer-book from

the prie-dieu and holds it droopingly. Slowly

his soft caressing eyes engage it. There is an

almost imperceptible stiffening of his frame.

His mouth opens with a faint click. He begins

to read.

The Ceremony of Marriage has begun.

[69]

IV.—THE VISIONARY

IV.—The Visionary

[71]“Yes,” said Cheops, helping his guest

over a ticklish place, “I daresay this

pile of rocks will last. It has cost me

a pretty penny, believe me. I made

up my mind at the start that it would be built

of honest stone, or not at all. No cheap and

shoddy brickwork for me! Look at Babylon.

It’s all brick, and it’s always tumbling down.

My ambassador there tells me that it costs a

million a year to keep up the walls alone—mind

you, the walls alone! What must it cost

to keep up the palace, with all that fancy work!

“Yes, I grant you that brickwork looks good.

But what of it? So does a cheap cotton night-shirt—you

know the gaudy things those Theban

peddlers sell to my sand-hogs down on the

river bank. But does it last? Of course it

doesn’t. Well, I am putting up this pyramid

to stay put, and I don’t give a damn for its

looks. I hear all sorts of funny cracks about

it. My barber is a sharp nigger and keeps his

ears open: he brings me all the gossip. But I

[72]let it go. This is my pyramid. I am putting

up the money for it, and I have got to be mortared

up in it when I die. So I am trying to

make a good, substantial job of it, and letting

the mere beauty of it go hang.

“Anyhow, there are plenty of uglier things

in Egypt. Look at some of those fifth-rate

pyramids up the river. When it comes to shape

they are pretty much the same as this one, and

when it comes to size, they look like warts beside

it. And look at the Sphinx. There is

something that cost four millions if it cost a

copper—and what is it now? A burlesque! A

caricature! An architectural cripple! So long

as it was new, good enough! It was a showy

piece of work. People came all the way from

Sicyonia and Tyre to gape at it. Everybody

said it was one of the sights no one could afford

to miss. But by and by a piece began to

peel off here and another piece there, and then

the nose cracked, and then an ear dropped off,

and then one of the eyes began to get mushy

and watery looking, and finally it was a mere

smudge, a false-face, a scarecrow. My father

spent a lot of money trying to fix it up, but

what good did it do? By the time he had the

nose cobbled the ears were loose again, and

so on. In the end he gave it up as a bad job.

[73]

“Yes; this pyramid has kept me on the jump,

but I’m going to stick to it if it breaks me.

Some say I ought to have built it across the

river, where the quarries are. Such gabble

makes me sick. Do I look like a man who

would go looking around for such child’s-play?

I hope not. A one-legged man could have done

that. Even a Babylonian could have done it.

It would have been as easy as milking a cow.

What I wanted was something that would keep

me on the jump—something that would put a

strain on me. So I decided to haul the whole

business across the river—six million tons of

rock. And when the engineers said that it

couldn’t be done, I gave them two days to get

out of Egypt, and then tackled it myself. It

was something new and hard. It was a job

I could get my teeth into.

“Well, I suppose you know what a time I

had of it at the start. First I tried a pontoon

bridge, but the stones for the bottom course

were so heavy that they sank the pontoons, and

I lost a couple of hundred niggers before I

saw that it couldn’t be done. Then I tried a

big raft, but in order to get her to float with

the stones I had to use such big logs that she

was unwieldy, and before I knew what had

struck me I had lost six big dressed stones and

[74]another hundred niggers. I got the laugh,

of course. Every numskull in Egypt wagged

his beard over it; I could hear the chatter myself.

But I kept quiet and stuck to the problem,

and by and by I solved it.

“I suppose you know how I did it. In a

general way? Well, the details are simple.

First I made a new raft, a good deal lighter

than the old one, and then I got a thousand

water-tight goat-skins and had them blown up

until they were as tight as drums. Then I got

together a thousand niggers who were good

swimmers, and gave each of them one of the

blown-up goat-skins. On each goat-skin there

was a leather thong, and on the bottom of the

raft, spread over it evenly, there were a thousand

hooks. Do you get the idea? Yes; that’s

it exactly. The niggers dived overboard with

the goat-skins, swam under the raft, and tied

the thongs to the hooks. And when all of them

were tied on, the raft floated like a bladder.

You simply couldn’t sink it.

“Naturally enough, the thing took time, and

there were accidents and setbacks. For instance,

some of the niggers were so light in

weight that they couldn’t hold their goat-skins

under water long enough to get them under the

raft. I had to weight those fellows by having

[75]rocks tied around their middles. And when

they had fastened their goat-skins and tried to

swim back, some of them were carried down

by the rocks. I never made any exact count,

but I suppose that two or three hundred of

them were drowned in that way. Besides, a

couple of hundred were drowned because they

couldn’t hold their breaths long enough to swim

under the raft and back. But what of it? I

wasn’t trying to hoard up niggers, but to make

a raft that would float. And I did it.

“Well, once I showed how it could be done,

all the wiseacres caught the idea, and after that

I put a big gang to work making more rafts,

and by and by I had sixteen of them in operation,

and was hauling more stone than the masons

could set. But I won’t go into all that.

Here is the pyramid; it speaks for itself. One

year more and I’ll have the top course laid and

begin on the surfacing. I am going to make

it plain marble, with no fancy work. I could

bring in a gang of Theban stonecutters and

have it carved all over with lions’ heads and

tiger claws and all that sort of gim-crackery,

but why waste time and money? This isn’t a

menagerie, but a pyramid. My idea was to

make it the boss pyramid of the world. The

[76]king who tries to beat it will have to get up

pretty early in the morning.

“But what troubles I have had! Believe me,

there has been nothing but trouble, trouble,

trouble from the start. I set aside the engineering

difficulties. They were hard for the

engineers, but easy for me, once I put my mind

on them. But the way these niggers have carried

on has been something terrible. At the

beginning I had only a thousand or two, and

they all came from one tribe; so they got along

fairly well. During the whole first year I

doubt that more than twenty or thirty were

killed in fights. But then I began to get fresh

batches from up the river, and after that it

was nothing but one fight after another. For

two weeks running not a stroke of work was

done. I really thought, at one time, that I’d

have to give up. But finally the army put down

the row, and after a couple of hundred of the

ringleaders had been thrown into the river

peace was restored. But it cost me, first and

last, fully three thousand niggers, and set me

back at least six months.

“Then came the so-called labor unions, and

the strikes, and more trouble. These labor

unions were started by a couple of smart, yellow

niggers from Chaldea, one of them a sort

[77]of lay preacher, a fellow with a lot of gab.

Before I got wind of them, they had gone so

far it was almost impossible to squelch them.

First I tried conciliation, but it didn’t work a

bit. They made the craziest demands you ever

heard of—a holiday every six days, meat every

day, no night work and regular houses to live

in. Some of them even had the effrontery to

ask for money! Think of it! Niggers asking

for money! Finally, I had to order out the

army again and let some blood. But every

time one was knocked over, I had to get another

one to take his place, and that meant

sending the army up the river, and more expense,

and more devilish worry and nuisance.

“In my grandfather’s time niggers were honest

and faithful workmen. You could take one

fresh from the bush, teach him to handle a

shovel or pull a rope in a year or so, and after

that he was worth almost as much as he could

eat. But the nigger of to-day isn’t worth a

damn. He never does an honest day’s work if

he can help it, and he is forever wanting something.

Take these fellows I have now—mainly

young bucks from around the First Cataract.

Here are niggers who never saw baker’s bread

or butcher’s meat until my men grabbed them.

They lived there in the bush like so many hyenas.

[78]They were ten days’ march from a

lemon. Well, now they get first-class beef

twice a week, good bread and all the fish they

can catch. They don’t have to begin work until

broad daylight, and they lay off at dark.

There is hardly one of them that hasn’t got a

psaltery, or a harp, or some other musical instrument.

If they want to dress up and make

believe they are Egyptians, I give them clothes.

If one of them is killed on the work, or by a

stray lion, or in a fight, I have him embalmed

by my own embalmers and plant him like a

man. If one of them breaks a leg or loses an

arm or gets too old to work, I turn him loose

without complaining, and he is free to go home

if he wants to.

“But are they contented? Do they show

any gratitude? Not at all. Scarcely a day

passes that I don’t hear of some fresh soldiering.

And, what is worse, they have stirred

up some of my own people—the carpenters,

stone-cutters, gang bosses and so on. Every

now and then my inspectors find some rotten

libel cut on a stone—something to the effect

that I am overworking them, and knocking

them about, and holding them against their

will, and generally mistreating them. I haven’t

the slightest doubt that some of these inscriptions

[79]have actually gone into the pyramid: it’s

impossible to watch every stone. Well, in the

years to come, they will be dug out and read

by strangers, and I will get a black eye. People

will think of Cheops as a heartless old

rapscallion—me, mind you! Can you beat it?”

[81]

V.—THE ARTIST

V.—The Artist. A Drama

Without Words

[83]

Characters:

- A Great Pianist

- A Janitor

- Six Musical Critics

- A Married Woman

- A Virgin

- Sixteen Hundred and Forty-three Other Women

- Six Other Men

Place—A City of the United States.

Time—A December afternoon.

(During the action of the play not a word

is uttered aloud. All of the speeches of the

characters are supposed to be unspoken meditations

only.)

A large, gloomy hall, with many rows of

uncushioned, uncomfortable seats, designed, it

[84]would seem, by some one misinformed as to

the average width of the normal human pelvis.

A number of busts of celebrated composers,

once white, but now a dirty gray, stand in

niches along the walls. At one end of the

hall there is a bare, uncarpeted stage, with

nothing on it save a grand piano and a chair.

It is raining outside, and, as hundreds of people

come crowding in, the air is laden with the

mingled scents of umbrellas, raincoats, goloshes,

cosmetics, perfumery and wet hair.

At eight minutes past four, The Janitor,

after smoothing his hair with his hands and

putting on a pair of detachable cuffs, emerges

from the wings and crosses the stage, his shoes

squeaking hideously at each step. Arriving at

the piano, he opens it with solemn slowness.

The job seems so absurdly trivial, even to so

mean an understanding, that he can’t refrain

from glorifying it with a bit of hocus-pocus.

This takes the form of a careful adjustment

of a mysterious something within the instrument.

He reaches in, pauses a moment as if

in doubt, reaches in again, and then permits a

faint smile of conscious sapience and efficiency

to illuminate his face. All of this accomplished,

he tiptoes back to the wings, his shoes again

squeaking.

[85]

The Janitor

Now all of them people think I’m the professor’s

tuner. (The thought gives him such

delight that, for the moment, his brain is

numbed. Then he proceeds.) I guess them

tuners make pretty good money. I wish I could

get the hang of the trick. It looks easy. (By

this time he has disappeared in the wings and

the stage is again a desert. Two or three

women, far back in the hall, start a halfhearted

handclapping. It dies out at once.

The noise of rustling programs and shuffling

feet succeeds it.)

Four Hundred of the Women

Oh, I do certainly hope he plays that lovely

Valse Poupée as an encore! They say he does

it better than Bloomfield-Zeisler.

One of the Critics

I hope the animal doesn’t pull any encore

numbers that I don’t recognize. All of these

people will buy the paper to-morrow morning

just to find out what they have heard. It’s infernally

embarrassing to have to ask the manager.

[86]The public expects a musical critic to

be a sort of walking thematic catalogue. The

public is an ass.

The Six Other Men

Oh, Lord! What a way to spend an afternoon!

A Hundred of the Women

I wonder if he’s as handsome as Paderewski.

Another Hundred of the Women

I wonder if he’s as gentlemanly as Josef

Hofmann.

Still Another Hundred Women

I wonder if he’s as fascinating as De Pachmann.

Yet Other Hundreds

I wonder if he has dark eyes. You never

can tell by those awful photographs in the

newspapers.

Half a Dozen Women

I wonder if he can really play the piano.

[87]

The Critic Aforesaid

What a hell of a wait! These rotten piano-thumping

immigrants deserve a hard call-down.

But what’s the use? The piano manufacturers

bring them over here to wallop their pianos—and

the piano manufacturers are not afraid

to advertise. If you knock them too hard you

have a nasty business-office row on your hands.

One of the Men

If they allowed smoking, it wouldn’t be so

bad.

Another Man

I wonder if that woman across the aisle——

(The Great Pianist bounces upon the

stage so suddenly that he is bowing in the center

before any one thinks to applaud. He makes

three stiff bows. At the second the applause

begins, swelling at once to a roar. He steps

up to the piano, bows three times more, and

then sits down. He hunches his shoulders,

reaches for the pedals with his feet, spreads

out his hands and waits for the clapper-clawing

to cease. He is an undersized, paunchy East

German, with hair the color of wet hay, and an

[88]extremely pallid complexion. Talcum powder

hides the fact that his nose is shiny and somewhat

pink. His eyebrows are carefully penciled

and there are artificial shadows under his

eyes. His face is absolutely expressionless.)

The Virgin

Oh!

The Married Women

Oh!

The Other Women

Oh! How dreadfully handsome!

The Virgin

Oh, such eyes, such depth! How he must

have suffered! I’d like to hear him play the

Prélude in D flat major. It would drive you

crazy!

A Hundred Other Women

I certainly do hope he plays some Schumann.

Other Women

What beautiful hands! I could kiss them!

(The Great Pianist, throwing back his

head, strikes the massive opening chords of a

[89]Beethoven sonata. There is a sudden hush and

each note is heard clearly. The tempo of the

first movement, which begins after a grand

pause, is allegro con brio, and the first subject

is given out in a sparkling cascade of sound.

But, despite the buoyancy of the music, there

is an unmistakable undercurrent of melancholy

in the playing. The audience doesn’t fail to

notice it.)

The Virgin

Oh, perfect! I could love him! Paderewski

played it like a fox trot. What poetry he puts

into it! I can see a soldier lover marching

off to war.

One of the Critics

The ass is dragging it. Doesn’t con brio

mean—well, what the devil does it mean? I

forget. I must look it up before I write the

notice. Somehow, brio suggests cheese. Anyhow,

Pachmann plays it a damn sight faster.

It’s safe to say that, at all events.

The Married Woman

Oh, I could listen to that sonata all day!

The poetry he puts into it—even into the

[90]allegro! Just think what the andante will be!

I like music to be sad.

Another Woman

What a sob he gets into it!

Many Other Women

How exquisite!

The Great Pianist

(Gathering himself together for the difficult

development section.) That American beer

will be the death of me! I wonder what they

put in it to give it its gassy taste. And the so-called

German beer they sell over here—du

heiliger Herr Jesu! Even Bremen would be

ashamed of it. In München the police would

take a hand.

(Aiming for the first and second C’s above

the staff, he accidentally strikes the C sharps

instead and has to transpose three measures to

get back into the key. The effect is harrowing,

and he gives his audience a swift glance

of apprehension.)

Two Hundred and Fifty Women

What new beauties he gets out of it!

[91]

A Man

He can tickle the ivories, all right, all right!

A Critic

Well, at any rate, he doesn’t try to imitate

Paderewski.

The Great Pianist

(Relieved by the non-appearance of the

hisses he expected.) Well, it’s lucky for me

that I’m not in Leipzig to-day! But in Leipzig

an artist runs no risks: the beer is pure. The

authorities see to that. The worse enemy of

technic is biliousness, and biliousness is sure

to follow bad beer. (He gets to the coda at

last and takes it at a somewhat livelier pace.)

The Virgin

How I envy the woman he loves! How it

would thrill me to feel his arms about me—to

be drawn closer, closer, closer! I would give

up the whole world! What are conventions,

prejudices, legal forms, morality, after all?

Vanities! Love is beyond and above them all—and

art is love! I think I must be a pagan.

[92]

The Great Pianist

And the herring! Good God, what herring!

These barbarous Americans——

The Virgin

Really, I am quite indecent! I should blush,

I suppose. But love is never ashamed—How

people misunderstand me!

The Married Woman

I wonder if he’s faithful. The chances are

against it. I never heard of a man who was.

(An agreeable melancholy overcomes her and

she gives herself up to the mood without

thought.)

The Great Pianist

I wonder whatever became of that girl in

Dresden. Every time I think of her, she suggests

pleasant thoughts—good beer, a fine

band, Gemütlichkeit. I must have been in love

with her—not much, of course, but just enough

to make things pleasant. And not a single letter

from her! I suppose she thinks I’m starving

to death over here—or tuning pianos.

[93]Well, when I get back with the money there’ll

be a shock for her. A shock—but not a

Pfennig!

The Married Woman

(Her emotional coma ended.) Still, you can

hardly blame him. There must be a good deal

of temptation for a great artist. All of these

frumps here would——

The Virgin

Ah, how dolorous, how exquisite is love!

How small the world would seem if——

The Married Woman

Of course you could hardly call such old

scarecrows temptations. But still——

(The Great Pianist comes to the last