The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Coral Island: A Tale of the Pacific Ocean

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Coral Island: A Tale of the Pacific Ocean

Author: R. M. Ballantyne

Release date: September 1, 1996 [eBook #646]

Most recently updated: September 27, 2021

Language: English

Credits: David Price

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CORAL ISLAND: A TALE OF THE PACIFIC OCEAN ***

![[Illustration]](https://img.gamelinxhub.com/images/cover.jpg)

The Coral Island:

A Tale of the Pacific Ocean

by

ROBERT MICHAEL BALLANTYNE,

author of “hudson’s bay; or, every-day life in

the wilds of north america;

”snow-flakes and sun-beams;

or, the young

fur-traders;”

“ungava: a

tale of the esquimaux,” etc., etc.

with

illustrations by dalziel.

London:

THOMAS NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW.

edinburgh; and new

york.

1884.

Preface

I was a boy when I went through the wonderful adventures

herein set down. With the memory of my boyish feelings

strong upon me, I present my book specially to boys, in the

earnest hope that they may derive valuable information, much

pleasure, great profit, and unbounded amusement from its

pages.

One word more. If there is any boy or man who loves to

be melancholy and morose, and who cannot enter with kindly

sympathy into the regions of fun, let me seriously advise him to

shut my book and put it away. It is not meant for him.

RALPH ROVER

CHAPTER I.

The beginning—My early life and character—I thirst

for adventure in foreign lands and go to sea.

Roving has always been, and still is, my ruling passion, the

joy of my heart, the very sunshine of my existence. In

childhood, in boyhood, and in man’s estate, I have been a

rover; not a mere rambler among the woody glens and upon the

hill-tops of my own native land, but an enthusiastic rover

throughout the length and breadth of the wide wide world.

It was a wild, black night of howling storm, the night in

which I was born on the foaming bosom of the broad Atlantic

Ocean. My father was a sea-captain; my grandfather was a

sea-captain; my great-grandfather had been a marine. Nobody

could tell positively what occupation his father had

followed; but my dear mother used to assert that he had been a

midshipman, whose grandfather, on the mother’s side, had

been an admiral in the royal navy. At anyrate we knew that,

as far back as our family could be traced, it had been intimately

connected with the great watery waste. Indeed this was the

case on both sides of the house; for my mother always went to sea

with my father on his long voyages, and so spent the greater part

of her life upon the water.

Thus it was, I suppose, that I came to inherit a roving

disposition. Soon after I was born, my father, being old,

retired from a seafaring life, purchased a small cottage in a

fishing village on the west coast of England, and settled down to

spend the evening of his life on the shores of that sea which had

for so many years been his home. It was not long after this

that I began to show the roving spirit that dwelt within

me. For some time past my infant legs had been gaining

strength, so that I came to be dissatisfied with rubbing the skin

off my chubby knees by walking on them, and made many attempts to

stand up and walk like a man; all of which attempts, however,

resulted in my sitting down violently and in sudden

surprise. One day I took advantage of my dear

mother’s absence to make another effort; and, to my joy, I

actually succeeded in reaching the doorstep, over which I tumbled

into a pool of muddy water that lay before my father’s

cottage door. Ah, how vividly I remember the horror of my

poor mother when she found me sweltering in the mud amongst a

group of cackling ducks, and the tenderness with which she

stripped off my dripping clothes and washed my dirty little

body! From this time forth my rambles became more frequent,

and, as I grew older, more distant, until at last I had wandered

far and near on the shore and in the woods around our humble

dwelling, and did not rest content until my father bound me

apprentice to a coasting vessel, and let me go to sea.

For some years I was happy in visiting the sea-ports, and in

coasting along the shores of my native land. My Christian

name was Ralph, and my comrades added to this the name of Rover,

in consequence of the passion which I always evinced for

travelling. Rover was not my real name, but as I never

received any other I came at last to answer to it as naturally as

to my proper name; and, as it is not a bad one, I see no good

reason why I should not introduce myself to the reader as Ralph

Rover. My shipmates were kind, good-natured fellows, and

they and I got on very well together. They did, indeed,

very frequently make game of and banter me, but not unkindly; and

I overheard them sometimes saying that Ralph Rover was a

“queer, old-fashioned fellow.” This, I must

confess, surprised me much, and I pondered the saying long, but

could come at no satisfactory conclusion as to that wherein my

old-fashionedness lay. It is true I was a quiet lad, and

seldom spoke except when spoken to. Moreover, I never could

understand the jokes of my companions even when they were

explained to me: which dulness in apprehension occasioned me much

grief; however, I tried to make up for it by smiling and looking

pleased when I observed that they were laughing at some witticism

which I had failed to detect. I was also very fond of

inquiring into the nature of things and their causes, and often

fell into fits of abstraction while thus engaged in my

mind. But in all this I saw nothing that did not seem to be

exceedingly natural, and could by no means understand why my

comrades should call me “an old-fashioned

fellow.”

Now, while engaged in the coasting trade, I fell in with many

seamen who had travelled to almost every quarter of the globe;

and I freely confess that my heart glowed ardently within me as

they recounted their wild adventures in foreign lands,—the

dreadful storms they had weathered, the appalling dangers they

had escaped, the wonderful creatures they had seen both on the

land and in the sea, and the interesting lands and strange people

they had visited. But of all the places of which they told

me, none captivated and charmed my imagination so much as the

Coral Islands of the Southern Seas. They told me of

thousands of beautiful fertile islands that had been formed by a

small creature called the coral insect, where summer reigned

nearly all the year round,—where the trees were laden with

a constant harvest of luxuriant fruit,—where the climate

was almost perpetually delightful,—yet where, strange to

say, men were wild, bloodthirsty savages, excepting in those

favoured isles to which the gospel of our Saviour had been

conveyed. These exciting accounts had so great an effect

upon my mind, that, when I reached the age of fifteen, I resolved

to make a voyage to the South Seas.

I had no little difficulty at first in prevailing on my dear

parents to let me go; but when I urged on my father that he would

never have become a great captain had he remained in the coasting

trade, he saw the truth of what I said, and gave his

consent. My dear mother, seeing that my father had made up

his mind, no longer offered opposition to my wishes.

“But oh, Ralph,” she said, on the day I bade her

adieu, “come back soon to us, my dear boy, for we are

getting old now, Ralph, and may not have many years to

live.”

I will not take up my reader’s time with a minute

account of all that occurred before I took my final leave of my

dear parents. Suffice it to say, that my father placed me

under the charge of an old mess-mate of his own, a merchant

captain, who was on the point of sailing to the South Seas in his

own ship, the Arrow. My mother gave me her blessing and a

small Bible; and her last request was, that I would never forget

to read a chapter every day, and say my prayers; which I

promised, with tears in my eyes, that I would certainly do.

Soon afterwards I went on board the Arrow, which was a fine

large ship, and set sail for the islands of the Pacific

Ocean.

CHAPTER II.

The departure—The sea—My companions—Some

account of the wonderful sights we saw on the great deep—A

dreadful storm and a frightful wreck.

It was a bright, beautiful, warm day when our ship spread her

canvass to the breeze, and sailed for the regions of the

south. Oh, how my heart bounded with delight as I listened

to the merry chorus of the sailors, while they hauled at the

ropes and got in the anchor! The captain shouted—the

men ran to obey—the noble ship bent over to the breeze, and

the shore gradually faded from my view, while I stood looking on

with a kind of feeling that the whole was a delightful dream.

The first thing that struck me as being different from

anything I had yet seen during my short career on the sea, was

the hoisting of the anchor on deck, and lashing it firmly down

with ropes, as if we had now bid adieu to the land for ever, and

would require its services no more.

“There, lass,” cried a broad-shouldered jack-tar,

giving the fluke of the anchor a hearty slap with his hand after

the housing was completed—“there, lass, take a good

nap now, for we shan’t ask you to kiss the mud again for

many a long day to come!”

And so it was. That anchor did not “kiss the

mud” for many long days afterwards; and when at last it

did, it was for the last time!

There were a number of boys in the ship, but two of them were

my special favourites. Jack Martin was a tall, strapping,

broad-shouldered youth of eighteen, with a handsome,

good-humoured, firm face. He had had a good education, was

clever and hearty and lion-like in his actions, but mild and

quiet in disposition. Jack was a general favourite, and had

a peculiar fondness for me. My other companion was Peterkin

Gay. He was little, quick, funny, decidedly mischievous,

and about fourteen years old. But Peterkin’s mischief

was almost always harmless, else he could not have been so much

beloved as he was.

“Hallo! youngster,” cried Jack Martin, giving me a

slap on the shoulder, the day I joined the ship, “come

below and I’ll show you your berth. You and I are to

be mess-mates, and I think we shall be good friends, for I like

the look o’ you.”

Jack was right. He and I and Peterkin afterwards became

the best and stanchest friends that ever tossed together on the

stormy waves.

I shall say little about the first part of our voyage.

We had the usual amount of rough weather and calm; also we saw

many strange fish rolling in the sea, and I was greatly delighted

one day by seeing a shoal of flying fish dart out of the water

and skim through the air about a foot above the surface.

They were pursued by dolphins, which feed on them, and one

flying-fish in its terror flew over the ship, struck on the

rigging, and fell upon the deck. Its wings were just fins

elongated, and we found that they could never fly far at a time,

and never mounted into the air like birds, but skimmed along the

surface of the sea. Jack and I had it for dinner, and found

it remarkably good.

When we approached Cape Horn, at the southern extremity of

America, the weather became very cold and stormy, and the sailors

began to tell stories about the furious gales and the dangers of

that terrible cape.

“Cape Horn,” said one, “is the most horrible

headland I ever doubled. I’ve sailed round it twice

already, and both times the ship was a’most blow’d

out o’ the water.”

“An’ I’ve been round it once,” said

another, “an’ that time the sails were split, and the

ropes frozen in the blocks, so that they wouldn’t work, and

we wos all but lost.”

“An’ I’ve been round it five times,”

cried a third, “an’ every time wos wuss than another,

the gales wos so tree-mendous!”

“And I’ve been round it no times at all,”

cried Peterkin, with an impudent wink of his eye,

“an’ that time I wos blow’d inside

out!”

Nevertheless, we passed the dreaded cape without much rough

weather, and, in the course of a few weeks afterwards, were

sailing gently, before a warm tropical breeze, over the Pacific

Ocean. Thus we proceeded on our voyage, sometimes bounding

merrily before a fair breeze, at other times floating calmly on

the glassy wave and fishing for the curious inhabitants of the

deep,—all of which, although the sailors thought little of

them, were strange, and interesting, and very wonderful to

me.

At last we came among the Coral Islands of the Pacific, and I

shall never forget the delight with which I gazed,—when we

chanced to pass one,—at the pure, white, dazzling shores,

and the verdant palm-trees, which looked bright and beautiful in

the sunshine. And often did we three long to be landed on

one, imagining that we should certainly find perfect happiness

there! Our wish was granted sooner than we expected.

One night, soon after we entered the tropics, an awful storm

burst upon our ship. The first squall of wind carried away

two of our masts; and left only the foremast standing. Even

this, however, was more than enough, for we did not dare to hoist

a rag of sail on it. For five days the tempest raged in all

its fury. Everything was swept off the decks except one

small boat. The steersman was lashed to the wheel, lest he

should be washed away, and we all gave ourselves up for

lost. The captain said that he had no idea where we were,

as we had been blown far out of our course; and we feared much

that we might get among the dangerous coral reefs which are so

numerous in the Pacific. At day-break on the sixth morning

of the gale we saw land ahead. It was an island encircled

by a reef of coral on which the waves broke in fury. There

was calm water within this reef, but we could only see one narrow

opening into it. For this opening we steered, but, ere we

reached it, a tremendous wave broke on our stern, tore the rudder

completely off, and left us at the mercy of the winds and

waves.

“It’s all over with us now, lads,” said the

captain to the men; “get the boat ready to launch; we shall

be on the rocks in less than half an hour.”

The men obeyed in gloomy silence, for they felt that there was

little hope of so small a boat living in such a sea.

“Come boys,” said Jack Martin, in a grave tone, to

me and Peterkin, as we stood on the quarterdeck awaiting our

fate;—“Come boys, we three shall stick

together. You see it is impossible that the little boat can

reach the shore, crowded with men. It will be sure to

upset, so I mean rather to trust myself to a large oar. I see

through the telescope that the ship will strike at the tail of

the reef, where the waves break into the quiet water inside; so,

if we manage to cling to the oar till it is driven over the

breakers, we may perhaps gain the shore. What say you; will

you join me?”

We gladly agreed to follow Jack, for he inspired us with

confidence, although I could perceive, by the sad tone of his

voice, that he had little hope; and, indeed, when I looked at the

white waves that lashed the reef and boiled against the rocks as

if in fury, I felt that there was but a step between us and

death. My heart sank within me; but at that moment my

thoughts turned to my beloved mother, and I remembered those

words, which were among the last that she said to

me—“Ralph, my dearest child, always remember in the

hour of danger to look to your Lord and Saviour Jesus

Christ. He alone is both able and willing to save your body

and your soul.” So I felt much comforted when I

thought thereon.

The ship was now very near the rocks. The men were ready

with the boat, and the captain beside them giving orders, when a

tremendous wave came towards us. We three ran towards the

bow to lay hold of our oar, and had barely reached it when the

wave fell on the deck with a crash like thunder. At the

same moment the ship struck, the foremast broke off close to the

deck and went over the side, carrying the boat and men along with

it. Our oar got entangled with the wreck, and Jack seized

an axe to cut it free, but, owing to the motion of the ship, he

missed the cordage and struck the axe deep into the oar.

Another wave, however, washed it clear of the wreck. We all

seized hold of it, and the next instant we were struggling in the

wild sea. The last thing I saw was the boat whirling in the

surf, and all the sailors tossed into the foaming waves.

Then I became insensible.

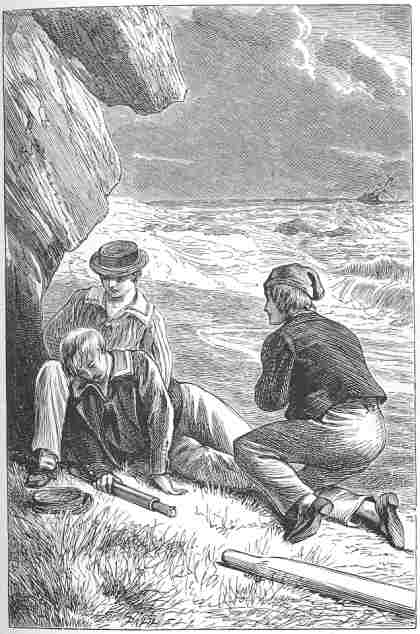

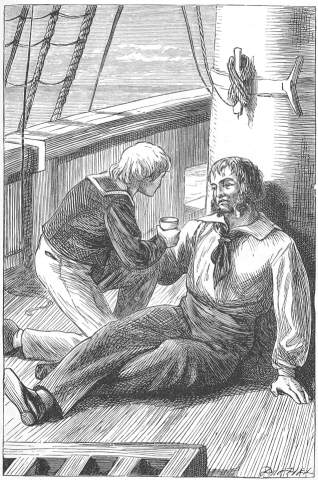

On recovering from my swoon, I found myself lying on a bank of

soft grass, under the shelter of an overhanging rock, with

Peterkin on his knees by my side, tenderly bathing my temples

with water, and endeavouring to stop the blood that flowed from a

wound in my forehead.

CHAPTER III.

The Coral Island—Our first cogitations after landing,

and the result of them—We conclude that the island is

uninhabited.

There is a strange and peculiar sensation experienced in

recovering from a state of insensibility, which is almost

indescribable; a sort of dreamy, confused consciousness; a

half-waking half-sleeping condition, accompanied with a feeling

of weariness, which, however, is by no means disagreeable.

As I slowly recovered and heard the voice of Peterkin inquiring

whether I felt better, I thought that I must have overslept

myself, and should be sent to the mast-head for being lazy; but

before I could leap up in haste, the thought seemed to vanish

suddenly away, and I fancied that I must have been ill.

Then a balmy breeze fanned my cheek, and I thought of home, and

the garden at the back of my father’s cottage, with its

luxuriant flowers, and the sweet-scented honey-suckle that my

dear mother trained so carefully upon the trellised porch.

But the roaring of the surf put these delightful thoughts to

flight, and I was back again at sea, watching the dolphins and

the flying-fish, and reefing topsails off the wild and stormy

Cape Horn. Gradually the roar of the surf became louder and

more distinct. I thought of being wrecked far far away from

my native land, and slowly opened my eyes to meet those of my

companion Jack, who, with a look of intense anxiety, was gazing

into my face.

“Speak to us, my dear Ralph,” whispered Jack,

tenderly, “are you better now?”

I smiled and looked up, saying, “Better; why, what do

you mean, Jack? I’m quite well.”

“Then what are you shamming for, and frightening us in

this way?” said Peterkin, smiling through his tears; for

the poor boy had been really under the impression that I was

dying.

I now raised myself on my elbow, and putting my hand to my

forehead, found that it had been cut pretty severely, and that I

had lost a good deal of blood.

“Come, come, Ralph,” said Jack, pressing me gently

backward, “lie down, my boy; you’re not right

yet. Wet your lips with this water, it’s cool and

clear as crystal. I got it from a spring close at

hand. There now, don’t say a word, hold your

tongue,” said he, seeing me about to speak.

“I’ll tell you all about it, but you must not utter a

syllable till you have rested well.”

“Oh! don’t stop him from speaking, Jack,”

said Peterkin, who, now that his fears for my safety were

removed, busied himself in erecting a shelter of broken branches

in order to protect me from the wind; which, however, was almost

unnecessary, for the rock beside which I had been laid completely

broke the force of the gale. “Let him speak, Jack;

it’s a comfort to hear that he’s alive, after lying

there stiff and white and sulky for a whole hour, just like an

Egyptian mummy. Never saw such a fellow as you are, Ralph;

always up to mischief. You’ve almost knocked out all

my teeth and more than half choked me, and now you go shamming

dead! It’s very wicked of you, indeed it

is.”

While Peterkin ran on in this style, my faculties became quite

clear again, and I began to understand my position.

“What do you mean by saying I half choked you,

Peterkin?” said I.

“What do I mean? Is English not your mother

tongue, or do you want me to repeat it in French, by way of

making it clearer? Don’t you

remember—”

“I remember nothing,” said I, interrupting him,

“after we were thrown into the sea.”

“Hush, Peterkin,” said Jack, “you’re

exciting Ralph with your nonsense. I’ll explain it to

you. You recollect that after the ship struck, we three

sprang over the bow into the sea; well, I noticed that the oar

struck your head and gave you that cut on the brow, which nearly

stunned you, so that you grasped Peterkin round the neck without

knowing apparently what you were about. In doing so you

pushed the telescope,—which you clung to as if it had been

your life,—against Peterkin’s mouth—”

“Pushed it against his mouth!” interrupted

Peterkin, “say crammed it down his throat. Why,

there’s a distinct mark of the brass rim on the back of my

gullet at this moment!”

“Well, well, be that as it may,” continued Jack,

“you clung to him, Ralph, till I feared you really would

choke him; but I saw that he had a good hold of the oar, so I

exerted myself to the utmost to push you towards the shore, which

we luckily reached without much trouble, for the water inside the

reef is quite calm.”

“But the captain and crew, what of them?” I

inquired anxiously.

Jack shook his head.

“Are they lost?”

“No, they are not lost, I hope, but I fear there is not

much chance of their being saved. The ship struck at the

very tail of the island on which we are cast. When the boat

was tossed into the sea it fortunately did not upset, although it

shipped a good deal of water, and all the men managed to scramble

into it; but before they could get the oars out the gale carried

them past the point and away to leeward of the island.

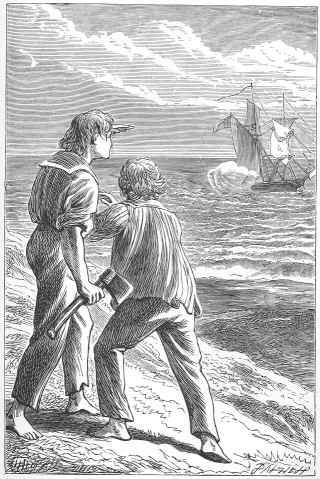

After we landed I saw them endeavouring to pull towards us, but

as they had only one pair of oars out of the eight that belong to

the boat, and as the wind was blowing right in their teeth, they

gradually lost ground. Then I saw them put about and hoist

some sort of sail,—a blanket, I fancy, for it was too small

for the boat,—and in half an hour they were out of

sight.”

“Poor fellows,” I murmured sorrowfully.

“But the more I think about it, I’ve better hope

of them,” continued Jack, in a more cheerful tone.

“You see, Ralph, I’ve read a great deal about these

South Sea Islands, and I know that in many places they are

scattered about in thousands over the sea, so they’re

almost sure to fall in with one of them before long.”

“I’m sure I hope so,” said Peterkin,

earnestly. “But what has become of the wreck,

Jack? I saw you clambering up the rocks there while I was

watching Ralph. Did you say she had gone to

pieces?”

“No, she has not gone to pieces, but she has gone to the

bottom,” replied Jack. “As I said before, she

struck on the tail of the island and stove in her bow, but the

next breaker swung her clear, and she floated away to

leeward. The poor fellows in the boat made a hard struggle

to reach her, but long before they came near her she filled and

went down. It was after she foundered that I saw them

trying to pull to the island.”

There was a long silence after Jack ceased speaking, and I

have no doubt that each was revolving in his mind our

extraordinary position. For my part I cannot say that my

reflections were very agreeable. I knew that we were on an

island, for Jack had said so, but whether it was inhabited or not

I did not know. If it should be inhabited, I felt certain,

from all I had heard of South Sea Islanders, that we should be

roasted alive and eaten. If it should turn out to be

uninhabited, I fancied that we should be starved to death.

“Oh!” thought I, “if the ship had only stuck on

the rocks we might have done pretty well, for we could have

obtained provisions from her, and tools to enable us to build a

shelter, but now—alas! alas! we are lost!”

These last words I uttered aloud in my distress.

“Lost! Ralph?” exclaimed Jack, while a smile

overspread his hearty countenance. “Saved, you should have

said. Your cogitations seem to have taken a wrong road, and

led you to a wrong conclusion.”

“Do you know what conclusion I have come

to?” said Peterkin. “I have made up my mind

that it’s capital,—first rate,—the best thing

that ever happened to us, and the most splendid prospect that

ever lay before three jolly young tars. We’ve got an

island all to ourselves. We’ll take possession in the

name of the king; we’ll go and enter the service of its

black inhabitants. Of course we’ll rise, naturally,

to the top of affairs. White men always do in savage

countries. You shall be king, Jack; Ralph, prime minister,

and I shall be—”

“The court jester,” interrupted Jack.

“No,” retorted Peterkin, “I’ll have no

title at all. I shall merely accept a highly responsible

situation under government, for you see, Jack, I’m fond of

having an enormous salary and nothing to do.”

“But suppose there are no natives?”

“Then we’ll build a charming villa, and plant a

lovely garden round it, stuck all full of the most splendiferous

tropical flowers, and we’ll farm the land, plant, sow,

reap, eat, sleep, and be merry.”

“But to be serious,” said Jack, assuming a grave

expression of countenance, which I observed always had the effect

of checking Peterkin’s disposition to make fun of

everything, “we are really in rather an uncomfortable

position. If this is a desert island, we shall have to live

very much like the wild beasts, for we have not a tool of any

kind, not even a knife.”

“Yes, we have that,” said Peterkin,

fumbling in his trousers pocket, from which he drew forth a small

penknife with only one blade, and that was broken.

“Well, that’s better than nothing; but

come,” said Jack, rising, “we are wasting our time in

talking instead of doing. You seem well

enough to walk now, Ralph, let us see what we have got in our

pockets, and then let us climb some hill and ascertain what sort

of island we have been cast upon, for, whether good or bad, it

seems likely to be our home for some time to come.”

CHAPTER IV.

We examine into our personal property, and make a happy

discovery—Our island described—Jack proves himself to

be learned and sagacious above his fellows—Curious

discoveries—Natural lemonade!

We now seated ourselves upon a rock and began to examine into

our personal property. When we reached the shore, after

being wrecked, my companions had taken off part of their clothes

and spread them out in the sun to dry, for, although the gale was

raging fiercely, there was not a single cloud in the bright

sky. They had also stripped off most part of my wet clothes

and spread them also on the rocks. Having resumed our

garments, we now searched all our pockets with the utmost care,

and laid their contents out on a flat stone before us; and, now

that our minds were fully alive to our condition, it was with no

little anxiety that we turned our several pockets inside out, in

order that nothing might escape us. When all was collected

together we found that our worldly goods consisted of the

following articles:—

First, A small penknife with a single blade broken off about

the middle and very rusty, besides having two or three notches on

its edge. (Peterkin said of this, with his usual

pleasantry, that it would do for a saw as well as a knife, which

was a great advantage.) Second, An old German-silver

pencil-case without any lead in it. Third, A piece of

whip-cord about six yards long. Fourth, A sailmaker’s

needle of a small size. Fifth, A ship’s telescope,

which I happened to have in my hand at the time the ship struck,

and which I had clung to firmly all the time I was in the

water. Indeed it was with difficulty that Jack got it out

of my grasp when I was lying insensible on the shore. I

cannot understand why I kept such a firm hold of this

telescope. They say that a drowning man will clutch at a

straw. Perhaps it may have been some such feeling in me,

for I did not know that it was in my hand at the time we were

wrecked. However, we felt some pleasure in having it with

us now, although we did not see that it could be of much use to

us, as the glass at the small end was broken to pieces. Our

sixth article was a brass ring which Jack always wore on his

little finger. I never understood why he wore it, for Jack

was not vain of his appearance, and did not seem to care for

ornaments of any kind. Peterkin said “it was in

memory of the girl he left behind him!” But as he

never spoke of this girl to either of us, I am inclined to think

that Peterkin was either jesting or mistaken. In addition

to these articles we had a little bit of tinder, and the clothes

on our backs. These last were as follows:—

Each of us had on a pair of stout canvass trousers, and a pair

of sailors’ thick shoes. Jack wore a red flannel

shirt, a blue jacket, and a red Kilmarnock bonnet or night-cap,

besides a pair of worsted socks, and a cotton

pocket-handkerchief, with sixteen portraits of Lord Nelson

printed on it, and a union Jack in the middle. Peterkin had

on a striped flannel shirt,—which he wore outside his

trousers, and belted round his waist, after the manner of a

tunic,—and a round black straw hat. He had no jacket,

having thrown it off just before we were cast into the sea; but

this was not of much consequence, as the climate of the island

proved to be extremely mild; so much so, indeed, that Jack and I

often preferred to go about without our jackets. Peterkin

had also a pair of white cotton socks, and a blue handkerchief

with white spots all over it. My own costume consisted of a

blue flannel shirt, a blue jacket, a black cap, and a pair of

worsted socks, besides the shoes and canvass trousers already

mentioned. This was all we had, and besides these things we

had nothing else; but, when we thought of the danger from which

we had escaped, and how much worse off we might have been had the

ship struck on the reef during the night, we felt very thankful

that we were possessed of so much, although, I must confess, we

sometimes wished that we had had a little more.

While we were examining these things, and talking about them,

Jack suddenly started and exclaimed—

“The oar! we have forgotten the oar.”

“What good will that do us?” said Peterkin;

“there’s wood enough on the island to make a thousand

oars.”

“Ay, lad,” replied Jack, “but there’s

a bit of hoop iron at the end of it, and that may be of much use

to us.”

“Very true,” said I, “let us go fetch

it;” and with that we all three rose and hastened down to

the beach. I still felt a little weak from loss of blood,

so that my companions soon began to leave me behind; but Jack

perceived this, and, with his usual considerate good nature,

turned back to help me. This was now the first time that I

had looked well about me since landing, as the spot where I had

been laid was covered with thick bushes which almost hid the

country from our view. As we now emerged from among these

and walked down the sandy beach together, I cast my eyes about,

and, truly, my heart glowed within me and my spirits rose at the

beautiful prospect which I beheld on every side. The gale

had suddenly died away, just as if it had blown furiously till it

dashed our ship upon the rocks, and had nothing more to do after

accomplishing that. The island on which we stood was hilly,

and covered almost everywhere with the most beautiful and richly

coloured trees, bushes, and shrubs, none of which I knew the

names of at that time, except, indeed, the cocoa-nut palms, which

I recognised at once from the many pictures that I had seen of

them before I left home. A sandy beach of dazzling

whiteness lined this bright green shore, and upon it there fell a

gentle ripple of the sea. This last astonished me much, for

I recollected that at home the sea used to fall in huge billows

on the shore long after a storm had subsided. But on

casting my glance out to sea the cause became apparent.

About a mile distant from the shore I saw the great billows of

the ocean rolling like a green wall, and falling with a long,

loud roar, upon a low coral reef, where they were dashed into

white foam and flung up in clouds of spray. This spray

sometimes flew exceedingly high, and, every here and there, a

beautiful rainbow was formed for a moment among the falling

drops. We afterwards found that this coral reef extended

quite round the island, and formed a natural breakwater to

it. Beyond this the sea rose and tossed violently from the

effects of the storm; but between the reef and the shore it was

as calm and as smooth as a pond.

My heart was filled with more delight than I can express at

sight of so many glorious objects, and my thoughts turned

suddenly to the contemplation of the Creator of them all. I

mention this the more gladly, because at that time, I am ashamed

to say, I very seldom thought of my Creator, although I was

constantly surrounded by the most beautiful and wonderful of His

works. I observed from the expression of my

companion’s countenance that he too derived much joy from

the splendid scenery, which was all the more agreeable to us

after our long voyage on the salt sea. There, the breeze

was fresh and cold, but here it was delightfully mild; and, when

a puff blew off the land, it came laden with the most exquisite

perfume that can be imagined. While we thus gazed, we were

startled by a loud “Huzza!” from Peterkin, and, on

looking towards the edge of the sea, we saw him capering and

jumping about like a monkey, and ever and anon tugging with all

his might at something that lay upon the shore.

“What an odd fellow he is, to be sure,” said Jack,

taking me by the arm and hurrying forward; “come, let us

hasten to see what it is.”

“Here it is, boys, hurrah! come along. Just what

we want,” cried Peterkin, as we drew near, still tugging

with all his power. “First rate; just the very

ticket!”

I need scarcely say to my readers that my companion Peterkin

was in the habit of using very remarkable and peculiar

phrases. And I am free to confess that I did not well

understand the meaning of some of them,—such, for instance,

as “the very ticket;” but I think it my duty to

recount everything relating to my adventures with a strict regard

to truthfulness in as far as my memory serves me; so I write, as

nearly as possible, the exact words that my companions

spoke. I often asked Peterkin to explain what he meant by

“ticket,” but he always answered me by going into

fits of laughter. However, by observing the occasions on

which he used it, I came to understand that it meant to show that

something was remarkably good, or fortunate.

On coming up we found that Peterkin was vainly endeavouring to

pull the axe out of the oar, into which, it will be remembered,

Jack struck it while endeavouring to cut away the cordage among

which it had become entangled at the bow of the ship.

Fortunately for us the axe had remained fast in the oar, and even

now, all Peterkin’s strength could not draw it out of the

cut.

“Ah! that is capital indeed,” cried Jack, at the

same time giving the axe a wrench that plucked it out of the

tough wood. “How fortunate this is! It will be

of more value to us than a hundred knives, and the edge is quite

new and sharp.”

“I’ll answer for the toughness of the handle at

any rate,” cried Peterkin; “my arms are nearly pulled

out of the sockets. But see here, our luck is great.

There is iron on the blade.” He pointed to a piece of

hoop iron, as he spoke, which had been nailed round the blade of

the oar to prevent it from splitting.

This also was a fortunate discovery. Jack went down on

his knees, and with the edge of the axe began carefully to force

out the nails. But as they were firmly fixed in, and the

operation blunted our axe, we carried the oar up with us to the

place where we had left the rest of our things, intending to burn

the wood away from the iron at a more convenient time.

“Now, lads,” said Jack, after we had laid it on

the stone which contained our little all, “I propose that

we should go to the tail of the island, where the ship struck,

which is only a quarter of a mile off, and see if anything else

has been thrown ashore. I don’t expect anything, but

it is well to see. When we get back here it will be time to

have our supper and prepare our beds.”

“Agreed!” cried Peterkin and I together, as,

indeed, we would have agreed to any proposal that Jack made; for,

besides his being older and much stronger and taller than either

of us, he was a very clever fellow, and I think would have

induced people much older than himself to choose him for their

leader, especially if they required to be led on a bold

enterprise.

Now, as we hastened along the white beach, which shone so

brightly in the rays of the setting sun that our eyes were quite

dazzled by its glare, it suddenly came into Peterkin’s head

that we had nothing to eat except the wild berries which grew in

profusion at our feet.

“What shall we do, Jack?” said he, with a rueful

look; “perhaps they may be poisonous!”

“No fear,” replied Jack, confidently; “I

have observed that a few of them are not unlike some of the

berries that grow wild on our own native hills. Besides, I

saw one or two strange birds eating them just a few minutes ago,

and what won’t kill the birds won’t kill us.

But look up there, Peterkin,” continued Jack, pointing to

the branched head of a cocoa-nut palm. “There are

nuts for us in all stages.”

“So there are!” cried Peterkin, who being of a

very unobservant nature had been too much taken up with other

things to notice anything so high above his head as the fruit of

a palm tree. But, whatever faults my young comrade had, he

could not be blamed for want of activity or animal spirits.

Indeed, the nuts had scarcely been pointed out to him when he

bounded up the tall stem of the tree like a squirrel, and, in a

few minutes, returned with three nuts, each as large as a

man’s fist.

“You had better keep them till we return,” said

Jack. “Let us finish our work before

eating.”

“So be it, captain, go ahead,” cried Peterkin,

thrusting the nuts into his trousers pocket. “In fact

I don’t want to eat just now, but I would give a good deal

for a drink. Oh that I could find a spring! but I

don’t see the smallest sign of one hereabouts. I say,

Jack, how does it happen that you seem to be up to

everything? You have told us the names of half-a-dozen

trees already, and yet you say that you were never in the South

Seas before.”

“I’m not up to everything, Peterkin, as

you’ll find out ere long,” replied Jack, with a

smile; “but I have been a great reader of books of travel

and adventure all my life, and that has put me up to a good many

things that you are, perhaps, not acquainted with.”

“Oh, Jack, that’s all humbug. If you begin

to lay everything to the credit of books, I’ll quite lose

my opinion of you,” cried Peterkin, with a look of

contempt. “I’ve seen a lot o’ fellows

that were always poring over books, and when they came to

try to do anything, they were no better than

baboons!”

“You are quite right,” retorted Jack; “and I

have seen a lot of fellows who never looked into books at all,

who knew nothing about anything except the things they had

actually seen, and very little they knew even about these.

Indeed, some were so ignorant that they did not know that

cocoa-nuts grew on cocoa-nut trees!”

I could not refrain from laughing at this rebuke, for there

was much truth in it, as to Peterkin’s ignorance.

“Humph! maybe you’re right,” answered

Peterkin; “but I would not give tuppence for a man

of books, if he had nothing else in him.”

“Neither would I,” said Jack; “but

that’s no reason why you should run books down, or think

less of me for having read them. Suppose, now, Peterkin,

that you wanted to build a ship, and I were to give you a long

and particular account of the way to do it, would not that be

very useful?”

“No doubt of it,” said Peterkin, laughing.

“And suppose I were to write the account in a letter

instead of telling you in words, would that be less

useful?”

“Well—no, perhaps not.”

“Well, suppose I were to print it, and send it to you in

the form of a book, would it not be as good and useful as

ever?”

“Oh, bother! Jack, you’re a philosopher, and

that’s worse than anything!” cried Peterkin, with a

look of pretended horror.

“Very well, Peterkin, we shall see,” returned

Jack, halting under the shade of a cocoa-nut tree.

“You said you were thirsty just a minute ago; now, jump up

that tree and bring down a nut,—not a ripe one, bring a

green, unripe one.”

Peterkin looked surprised, but, seeing that Jack was in

earnest, he obeyed.

“Now, cut a hole in it with your penknife, and clap it

to your mouth, old fellow,” said Jack.

Peterkin did as he was directed, and we both burst into

uncontrollable laughter at the changes that instantly passed over

his expressive countenance. No sooner had he put the nut to

his mouth, and thrown back his head in order to catch what came

out of it, than his eyes opened to twice their ordinary size with

astonishment, while his throat moved vigorously in the act of

swallowing. Then a smile and look of intense delight

overspread his face, except, indeed, the mouth, which, being

firmly fixed to the hole in the nut, could not take part in the

expression; but he endeavoured to make up for this by winking at

us excessively with his right eye. At length he stopped,

and, drawing a long breath, exclaimed—

“Nectar! perfect nectar! I say, Jack, you’re

a Briton—the best fellow I ever met in my life. Only

taste that!” said he, turning to me and holding the nut to

my mouth. I immediately drank, and certainly I was much

surprised at the delightful liquid that flowed copiously down my

throat. It was extremely cool, and had a sweet taste,

mingled with acid; in fact, it was the likest thing to lemonade I

ever tasted, and was most grateful and refreshing. I handed

the nut to Jack, who, after tasting it, said, “Now,

Peterkin, you unbeliever, I never saw or tasted a cocoa nut in my

life before, except those sold in shops at home; but I once read

that the green nuts contain that stuff, and you see it is

true!”

“And pray,” asked Peterkin, “what sort of

‘stuff’ does the ripe nut contain?”

“A hollow kernel,” answered Jack, “with a

liquid like milk in it; but it does not satisfy thirst so well as

hunger. It is very wholesome food I believe.”

“Meat and drink on the same tree!” cried Peterkin;

“washing in the sea, lodging on the ground,—and all

for nothing! My dear boys, we’re set up for life; it

must be the ancient Paradise,—hurrah!” and Peterkin

tossed his straw hat in the air, and ran along the beach

hallooing like a madman with delight.

We afterwards found, however, that these lovely islands were

very unlike Paradise in many things. But more of this in

its proper place.

We had now come to the point of rocks on which the ship had

struck, but did not find a single article, although we searched

carefully among the coral rocks, which at this place jutted out

so far as nearly to join the reef that encircled the

island. Just as we were about to return, however, we saw

something black floating in a little cove that had escaped our

observation. Running forward, we drew it from the water,

and found it to be a long thick leather boot, such as fishermen

at home wear; and a few paces farther on we picked up its

fellow. We at once recognised these as having belonged to

our captain, for he had worn them during the whole of the storm,

in order to guard his legs from the waves and spray that

constantly washed over our decks. My first thought on

seeing them was that our dear captain had been drowned; but Jack

soon put my mind more at rest on that point, by saying that if

the captain had been drowned with the boots on, he would

certainly have been washed ashore along with them, and that he

had no doubt whatever he had kicked them off while in the sea,

that he might swim more easily.

Peterkin immediately put them on, but they were so large that,

as Jack said, they would have done for boots, trousers, and vest

too. I also tried them, but, although I was long enough in

the legs for them, they were much too large in the feet for me;

so we handed them to Jack, who was anxious to make me keep them,

but as they fitted his large limbs and feet as if they had been

made for him, I would not hear of it, so he consented at last to

use them. I may remark, however, that Jack did not use them

often, as they were extremely heavy.

It was beginning to grow dark when we returned to our

encampment; so we put off our visit to the top of a hill till

next day, and employed the light that yet remained to us in

cutting down a quantity of boughs and the broad leaves of a tree,

of which none of us knew the name. With these we erected a

sort of rustic bower, in which we meant to pass the night.

There was no absolute necessity for this, because the air of our

island was so genial and balmy that we could have slept quite

well without any shelter; but we were so little used to sleeping

in the open air, that we did not quite relish the idea of lying

down without any covering over us: besides, our bower would

shelter us from the night dews or rain, if any should happen to

fall. Having strewed the floor with leaves and dry grass,

we bethought ourselves of supper.

But it now occurred to us, for the first time, that we had no

means of making a fire.

“Now, there’s a fix!—what shall we

do?” said Peterkin, while we both turned our eyes to Jack,

to whom we always looked in our difficulties. Jack seemed

not a little perplexed.

“There are flints enough, no doubt, on the beach,”

said he, “but they are of no use at all without a

steel. However, we must try.” So saying, he

went to the beach, and soon returned with two flints. On

one of these he placed the tinder, and endeavoured to ignite it;

but it was with great difficulty that a very small spark was

struck out of the flints, and the tinder, being a bad, hard

piece, would not catch. He then tried the bit of hoop iron,

which would not strike fire at all; and after that the back of

the axe, with no better success. During all these trials

Peterkin sat with his hands in his pockets, gazing with a most

melancholy visage at our comrade, his face growing longer and

more miserable at each successive failure.

“Oh dear!” he sighed, “I would not care a

button for the cooking of our victuals,—perhaps they

don’t need it,—but it’s so dismal to eat

one’s supper in the dark, and we have had such a capital

day, that it’s a pity to finish off in this glum

style. Oh, I have it!” he cried, starting up;

“the spy-glass,—the big glass at the end is a

burning-glass!”

“You forget that we have no sun,” said I.

Peterkin was silent. In his sudden recollection of the

telescope he had quite overlooked the absence of the sun.

“Ah, boys, I’ve got it now!” exclaimed Jack,

rising and cutting a branch from a neighbouring bush, which be

stripped of its leaves. “I recollect seeing this done

once at home. Hand me the bit of whip-cord.”

With the cord and branch Jack soon formed a bow. Then he

cut a piece, about three inches long, off the end of a dead

branch, which he pointed at the two ends. Round this he

passed the cord of the bow, and placed one end against his chest,

which was protected from its point by a chip of wood; the other

point he placed against the bit of tinder, and then began to saw

vigorously with the bow, just as a blacksmith does with his drill

while boring a hole in a piece of iron. In a few seconds

the tinder began to smoke; in less than a minute it caught fire;

and in less than a quarter of an hour we were drinking our

lemonade and eating cocoa nuts round a fire that would have

roasted an entire sheep, while the smoke, flames, and sparks,

flew up among the broad leaves of the overhanging palm trees, and

cast a warm glow upon our leafy bower.

That night the starry sky looked down through the gently

rustling trees upon our slumbers, and the distant roaring of the

surf upon the coral reef was our lullaby.

CHAPTER V.

Morning, and cogitations connected therewith—We

luxuriate in the sea, try our diving powers, and make enchanting

excursions among the coral groves at the bottom of the

ocean—The wonders of the deep enlarged upon.

What a joyful thing it is to awaken, on a fresh glorious

morning, and find the rising sun staring into your face with

dazzling brilliancy!—to see the birds twittering in the

bushes, and to hear the murmuring of a rill, or the soft hissing

ripples as they fall upon the sea-shore! At any time and in

any place such sights and sounds are most charming, but more

especially are they so when one awakens to them, for the first

time, in a novel and romantic situation, with the soft sweet air

of a tropical climate mingling with the fresh smell of the sea,

and stirring the strange leaves that flutter overhead and around

one, or ruffling the plumage of the stranger birds that fly

inquiringly around, as if to demand what business we have to

intrude uninvited on their domains. When I awoke on the

morning after the shipwreck, I found myself in this most

delightful condition; and, as I lay on my back upon my bed of

leaves, gazing up through the branches of the cocoa-nut trees

into the clear blue sky, and watched the few fleecy clouds that

passed slowly across it, my heart expanded more and more with an

exulting gladness, the like of which I had never felt

before. While I meditated, my thoughts again turned to the

great and kind Creator of this beautiful world, as they had done

on the previous day, when I first beheld the sea and the coral

reef, with the mighty waves dashing over it into the calm waters

of the lagoon.

While thus meditating, I naturally bethought me of my Bible,

for I had faithfully kept the promise, which I gave at parting to

my beloved mother, that I would read it every morning; and it was

with a feeling of dismay that I remembered I had left it in the

ship. I was much troubled about this. However, I

consoled myself with reflecting that I could keep the second part

of my promise to her, namely, that I should never omit to say my

prayers. So I rose quietly, lest I should disturb my

companions, who were still asleep, and stepped aside into the

bushes for this purpose.

On my return I found them still slumbering, so I again lay

down to think over our situation. Just at that moment I was

attracted by the sight of a very small parrot, which Jack

afterwards told me was called a paroquet. It was seated on

a twig that overhung Peterkin’s head, and I was speedily

lost in admiration of its bright green plumage, which was mingled

with other gay colours. While I looked I observed that the

bird turned its head slowly from side to side and looked

downwards, first with the one eye, and then with the other.

On glancing downwards I observed that Peterkin’s mouth was

wide open, and that this remarkable bird was looking into

it. Peterkin used to say that I had not an atom of fun in

my composition, and that I never could understand a joke.

In regard to the latter, perhaps he was right; yet I think that,

when they were explained to me, I understood jokes as well as

most people: but in regard to the former he must certainly have

been wrong, for this bird seemed to me to be extremely funny; and

I could not help thinking that, if it should happen to faint, or

slip its foot, and fall off the twig into Peterkin’s mouth,

he would perhaps think it funny too! Suddenly the paroquet

bent down its head and uttered a loud scream in his face.

This awoke him, and, with a cry of surprise, he started up, while

the foolish bird flew precipitately away.

“Oh you monster!” cried Peterkin, shaking his fist

at the bird. Then he yawned and rubbed his eyes, and asked

what o’clock it was.

I smiled at this question, and answered that, as our watches

were at the bottom of the sea, I could not tell, but it was a

little past sunrise.

Peterkin now began to remember where we were. As he

looked up into the bright sky, and snuffed the scented air, his

eyes glistened with delight, and he uttered a faint

“hurrah!” and yawned again. Then he gazed

slowly round, till, observing the calm sea through an opening in

the bushes, he started suddenly up as if he had received an

electric shock, uttered a vehement shout, flung off his garments,

and, rushing over the white sands, plunged into the water.

The cry awoke Jack, who rose on his elbow with a look of grave

surprise; but this was followed by a quiet smile of intelligence

on seeing Peterkin in the water. With an energy that he

only gave way to in moments of excitement, Jack bounded to his

feet, threw off his clothes, shook back his hair, and with a

lion-like spring, dashed over the sands and plunged into the sea

with such force as quite to envelop Peterkin in a shower of

spray. Jack was a remarkably good swimmer and diver, so

that after his plunge we saw no sign of him for nearly a minute;

after which he suddenly emerged, with a cry of joy, a good many

yards out from the shore. My spirits were so much raised by

seeing all this that I, too, hastily threw off my garments and

endeavoured to imitate Jack’s vigorous bound; but I was so

awkward that my foot caught on a stump, and I fell to the ground;

then I slipped on a stone while running over the mud, and nearly

fell again, much to the amusement of Peterkin, who laughed

heartily, and called me a “slow coach,” while Jack

cried out, “Come along, Ralph, and I’ll help

you.” However, when I got into the water I managed

very well, for I was really a good swimmer, and diver too.

I could not, indeed, equal Jack, who was superior to any

Englishman I ever saw, but I infinitely surpassed Peterkin, who

could only swim a little, and could not dive at all.

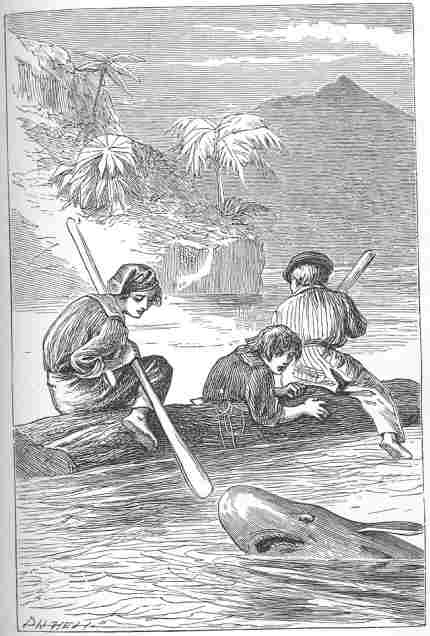

While Peterkin enjoyed himself in the shallow water and in

running along the beach, Jack and I swam out into the deep water,

and occasionally dived for stones. I shall never forget my

surprise and delight on first beholding the bottom of the

sea. As I have before stated, the water within the reef was

as calm as a pond; and, as there was no wind, it was quite clear,

from the surface to the bottom, so that we could see down easily

even at a depth of twenty or thirty yards. When Jack and I

dived in shallower water, we expected to have found sand and

stones, instead of which we found ourselves in what appeared

really to be an enchanted garden. The whole of the bottom

of the lagoon, as we called the calm water within the reef, was

covered with coral of every shape, size, and hue. Some

portions were formed like large mushrooms; others appeared like

the brain of a man, having stalks or necks attached to them; but

the most common kind was a species of branching coral, and some

portions were of a lovely pale pink colour, others pure

white. Among this there grew large quantities of sea-weed

of the richest hues imaginable, and of the most graceful forms;

while innumerable fishes—blue, red, yellow, green, and

striped—sported in and out amongst the flower-beds of this

submarine garden, and did not appear to be at all afraid of our

approaching them.

On darting to the surface for breath, after our first dive,

Jack and I rose close to each other.

“Did you ever in your life, Ralph, see anything so

lovely?” said Jack, as he flung the spray from his

hair.

“Never,” I replied. “It appears to me

like fairy realms. I can scarcely believe that we are not

dreaming.”

“Dreaming!” cried Jack, “do you know, Ralph,

I’m half tempted to think that we really are

dreaming. But if so, I am resolved to make the most of it,

and dream another dive; so here goes,—down again, my

boy!”

We took the second dive together, and kept beside each other

while under water; and I was greatly surprised to find that we

could keep down much longer than I ever recollect having done in

our own seas at home. I believe that this was owing to the

heat of the water, which was so warm that we afterwards found we

could remain in it for two and three hours at a time without

feeling any unpleasant effects such as we used to experience in

the sea at home. When Jack reached the bottom, he grasped

the coral stems, and crept along on his hands and knees, peeping

under the sea-weed and among the rocks. I observed him also

pick up one or two large oysters, and retain them in his grasp,

as if he meant to take them up with him, so I also gathered a

few. Suddenly he made a grasp at a fish with blue and

yellow stripes on its back, and actually touched its tail, but

did not catch it. At this he turned towards me and

attempted to smile; but no sooner had he done so than he sprang

like an arrow to the surface, where, on following him, I found

him gasping and coughing, and spitting water from his

mouth. In a few minutes he recovered, and we both turned to

swim ashore.

“I declare, Ralph,” said he, “that I

actually tried to laugh under water.”

“So I saw,” I replied; “and I observed that

you very nearly caught that fish by the tail. It would have

done capitally for breakfast if you had.”

“Breakfast enough here,” said he, holding up the

oysters, as we landed and ran up the beach.

“Hallo! Peterkin, here you are, boy. Split open

these fellows while Ralph and I put on our clothes.

They’ll agree with the cocoa nuts excellently, I have no

doubt.”

Peterkin, who was already dressed, took the oysters, and

opened them with the edge of our axe, exclaiming, “Now,

that is capital. There’s nothing I’m so

fond of.”

“Ah! that’s lucky,” remarked Jack.

“I’ll be able to keep you in good order now, Master

Peterkin. You know you can’t dive any better than a

cat. So, sir, whenever you behave ill, you shall have no

oysters for breakfast.”

“I’m very glad that our prospect of breakfast is

so good,” said I, “for I’m very

hungry.”

“Here, then, stop your mouth with that, Ralph,”

said Peterkin, holding a large oyster to my lips. I opened

my mouth and swallowed it in silence, and really it was

remarkably good.

We now set ourselves earnestly about our preparations for

spending the day. We had no difficulty with the fire this

morning, as our burning-glass was an admirable one; and while we

roasted a few oysters and ate our cocoa nuts, we held a long,

animated conversation about our plans for the future. What

those plans were, and how we carried them into effect, the reader

shall see hereafter.

CHAPTER VI.

An excursion into the interior, in which we make many valuable

and interesting discoveries—We get a dreadful

fright—The bread-fruit tree—Wonderful peculiarity of

some of the fruit trees—Signs of former inhabitants.

Our first care, after breakfast, was to place the few articles

we possessed in the crevice of a rock at the farther end of a

small cave which we discovered near our encampment. This

cave, we hoped, might be useful to us afterwards as a

store-house. Then we cut two large clubs off a species of

very hard tree which grew near at hand. One of these was

given to Peterkin, the other to me, and Jack armed himself with

the axe. We took these precautions because we purposed to

make an excursion to the top of the mountains of the interior, in

order to obtain a better view of our island. Of course we

knew not what dangers might befall us by the way, so thought it

best to be prepared.

Having completed our arrangements and carefully extinguished

our fire, we sallied forth and walked a short distance along the

sea-beach, till we came to the entrance of a valley, through

which flowed the rivulet before mentioned. Here we turned

our backs on the sea and struck into the interior.

The prospect that burst upon our view on entering the valley

was truly splendid. On either side of us there was a gentle

rise in the land, which thus formed two ridges about a mile apart

on each side of the valley. These ridges,—which, as

well as the low grounds between them, were covered with trees and

shrubs of the most luxuriant kind—continued to recede

inland for about two miles, when they joined the foot of a small

mountain. This hill rose rather abruptly from the head of

the valley, and was likewise entirely covered even to the top

with trees, except on one particular spot near the left shoulder,

where was a bare and rocky place of a broken and savage

character. Beyond this hill we could not see, and we

therefore directed our course up the banks of the rivulet towards

the foot of it, intending to climb to the top, should that be

possible, as, indeed, we had no doubt it was.

Jack, being the wisest and boldest among us, took the lead,

carrying the axe on his shoulder. Peterkin, with his

enormous club, came second, as he said he should like to be in a

position to defend me if any danger should threaten. I

brought up the rear, but, having been more taken up with the

wonderful and curious things I saw at starting than with thoughts

of possible danger, I had very foolishly left my club behind

me. Although, as I have said the trees and bushes were very

luxuriant, they were not so thickly crowded together as to hinder

our progress among them. We were able to wind in and out,

and to follow the banks of the stream quite easily, although, it

is true, the height and thickness of the foliage prevented us

from seeing far ahead. But sometimes a jutting-out rock on

the hill sides afforded us a position whence we could enjoy the

romantic view and mark our progress towards the foot of the

hill. I was particularly struck, during the walk, with the

richness of the undergrowth in most places, and recognised many

berries and plants that resembled those of my native land,

especially a tall, elegantly-formed fern, which emitted an

agreeable perfume. There were several kinds of flowers,

too, but I did not see so many of these as I should have expected

in such a climate. We also saw a great variety of small

birds of bright plumage, and many paroquets similar to the one

that awoke Peterkin so rudely in the morning.

Thus we advanced to the foot of the hill without encountering

anything to alarm us, except, indeed, once, when we were passing

close under a part of the hill which was hidden from our view by

the broad leaves of the banana trees, which grew in great

luxuriance in that part. Jack was just preparing to force

his way through this thicket, when we were startled and arrested

by a strange pattering or rumbling sound, which appeared to us

quite different from any of the sounds we had heard during the

previous part of our walk.

“Hallo!” cried Peterkin, stopping short and

grasping his club with both hands, “what’s

that?”

Neither of us replied; but Jack seized his axe in his right

hand, while with the other he pushed aside the broad leaves and

endeavoured to peer amongst them.

“I can see nothing,” he said, after a short

pause.

“I think it—”

Again the rumbling sound came, louder than before, and we all

sprang back and stood on the defensive. For myself, having

forgotten my club, and not having taken the precaution to cut

another, I buttoned my jacket, doubled my fists, and threw myself

into a boxing attitude. I must say, however, that I felt

somewhat uneasy; and my companions afterwards confessed that

their thoughts at this moment had been instantly filled with all

they had ever heard or read of wild beasts and savages,

torturings at the stake, roastings alive, and such like horrible

things. Suddenly the pattering noise increased with tenfold

violence. It was followed by a fearful crash among the

bushes, which was rapidly repeated, as if some gigantic animal

were bounding towards us. In another moment an enormous

rock came crashing through the shrubbery, followed by a cloud of

dust and small stones, flew close past the spot where we stood,

carrying bushes and young trees along with it.

“Pooh! is that all?” exclaimed Peterkin, wiping

the perspiration off his forehead. “Why, I thought it

was all the wild men and beasts in the South Sea Islands

galloping on in one grand charge to sweep us off the face of the

earth, instead of a mere stone tumbling down the mountain

side.”

“Nevertheless,” remarked Jack, “if that same

stone had hit any of us, it would have rendered the charge you

speak of quite unnecessary, Peterkin.”

This was true, and I felt very thankful for our escape.

On examining the spot more narrowly, we found that it lay close

to the foot of a very rugged precipice, from which stones of

various sizes were always tumbling at intervals. Indeed,

the numerous fragments lying scattered all around might have

suggested the cause of the sound, had we not been too suddenly

alarmed to think of anything.

We now resumed our journey, resolving that, in our future

excursions into the interior, we would be careful to avoid this

dangerous precipice.

Soon afterwards we arrived at the foot of the hill and

prepared to ascend it. Here Jack made a discovery which

caused us all very great joy. This was a tree of a

remarkably beautiful appearance, which Jack confidently declared

to be the celebrated bread-fruit tree.

“Is it celebrated?” inquired Peterkin, with a look

of great simplicity.

“It is,” replied Jack

“That’s odd, now,” rejoined Peterkin;

“never heard of it before.”

“Then it’s not so celebrated as I thought it

was,” returned Jack, quietly squeezing Peterkin’s hat

over his eyes; “but listen, you ignorant boobie! and hear

of it now.”

Peterkin re-adjusted his hat, and was soon listening with as

much interest as myself, while Jack told us that this tree is one

of the most valuable in the islands of the south; that it bears

two, sometimes three, crops of fruit in the year; that the fruit

is very like wheaten bread in appearance, and that it constitutes

the principal food of many of the islanders.

“So,” said Peterkin, “we seem to have

everything ready prepared to our hands in this wonderful

island,—lemonade ready bottled in nuts, and loaf-bread

growing on the trees!”

Peterkin, as usual, was jesting; nevertheless, it is a curious

fact that he spoke almost the literal truth.

“Moreover,” continued Jack, “the bread-fruit

tree affords a capital gum, which serves the natives for pitching

their canoes; the bark of the young branches is made by them into

cloth; and of the wood, which is durable and of a good colour,

they build their houses. So you see, lads, that we have no

lack of material here to make us comfortable, if we are only

clever enough to use it.”

“But are you sure that that’s it?” asked

Peterkin.

“Quite sure,” replied Jack; “for I was

particularly interested in the account I once read of it, and I

remember the description well. I am sorry, however, that I

have forgotten the descriptions of many other trees which I am

sure we have seen to-day, if we could but recognise them.

So you see, Peterkin, I’m not up to everything

yet.”

“Never mind, Jack,” said Peterkin, with a grave,

patronizing expression of countenance, patting his tall companion

on the shoulder,—“never mind, Jack; you know a good

deal for your age. You’re a clever boy, sir,—a

promising young man; and if you only go on as you have begun,

sir, you will—”

The end of this speech was suddenly cut short by Jack tripping

up Peterkin’s heels and tumbling him into a mass of thick

shrubs, where, finding himself comfortable, he lay still basking

in the sunshine, while Jack and I examined the bread-tree.

We were much struck with the deep, rich green colour of its

broad leaves, which were twelve or eighteen inches long, deeply

indented, and of a glossy smoothness, like the laurel. The

fruit, with which it was loaded, was nearly round, and appeared

to be about six inches in diameter, with a rough rind, marked

with lozenge-shaped divisions. It was of various colours,

from light pea-green to brown and rich yellow. Jack said

that the yellow was the ripe fruit. We afterwards found

that most of the fruit-trees on the island were evergreens, and

that we might, when we wished, pluck the blossom and the ripe

fruit from the same tree. Such a wonderful difference from

the trees of our own country surprised us not a little. The

bark of the tree was rough and light-coloured; the trunk was

about two feet in diameter, and it appeared to be twenty feet

high, being quite destitute of branches up to that height, where

it branched off into a beautiful and umbrageous head. We

noticed that the fruit hung in clusters of twos and threes on the

branches; but as we were anxious to get to the top of the hill,

we refrained from attempting to pluck any at that time.

Our hearts were now very much cheered by our good fortune, and

it was with light and active steps that we clambered up the steep

sides of the hill. On reaching the summit, a new, and if

possible a grander, prospect met our gaze. We found that

this was not the highest part of the island, but that another

hill lay beyond, with a wide valley between it and the one on

which we stood. This valley, like the first, was also full

of rich trees, some dark and some light green, some heavy and

thick in foliage, and others light, feathery, and graceful, while

the beautiful blossoms on many of them threw a sort of rainbow

tint over all, and gave to the valley the appearance of a garden

of flowers. Among these we recognised many of the

bread-fruit trees, laden with yellow fruit, and also a great many

cocoa-nut palms. After gazing our fill we pushed down the

hill side, crossed the valley, and soon began to ascend the

second mountain. It was clothed with trees nearly to the

top, but the summit was bare, and in some places broken.

While on our way up we came to an object which filled us with

much interest. This was the stump of a tree that had

evidently been cut down with an axe! So, then, we were not

the first who had viewed this beautiful isle. The hand of

man had been at work there before us. It now began to recur

to us again that perhaps the island was inhabited, although we

had not seen any traces of man until now; but a second glance at

the stump convinced us that we had not more reason to think so

now than formerly; for the surface of the wood was quite decayed,

and partly covered with fungus and green matter, so that it must

have been cut many years ago.

“Perhaps,” said Peterkin, “some ship or

other has touched here long ago for wood, and only taken one

tree.”

We did not think this likely, however, because, in such

circumstances, the crew of a ship would cut wood of small size,

and near the shore, whereas this was a large tree and stood near

the top of the mountain. In fact it was the highest large

tree on the mountain, all above it being wood of very recent

growth.

“I can’t understand it,” said Jack,

scratching the surface of the stump with his axe. “I

can only suppose that the savages have been here and cut it for

some purpose known only to themselves. But, hallo! what

have we here?”

As he spoke, Jack began carefully to scrape away the moss and

fungus from the stump, and soon laid bare three distinct traces

of marks, as if some inscription or initials had been cut

thereon. But although the traces were distinct, beyond all

doubt, the exact form of the letters could not be made out.

Jack thought they looked like J. S. but we could not be

certain. They had apparently been carelessly cut, and long

exposure to the weather had so broken them up that we could not

make out what they were. We were exceedingly perplexed at

this discovery, and stayed a long time at the place conjecturing

what these marks could have been, but without avail; so, as the

day was advancing, we left it and quickly reached the top of the

mountain.

We found this to be the highest point of the island, and from

it we saw our kingdom lying, as it were, like a map around

us. As I have always thought it impossible to get a thing

properly into one’s understanding without comprehending it,

I shall beg the reader’s patience for a little while I

describe our island, thus, shortly:—