The Project Gutenberg eBook of Four Young Explorers; Or, Sight-Seeing in the Tropics

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Four Young Explorers; Or, Sight-Seeing in the Tropics

Author: Oliver Optic

Illustrator: A. B. Shute

Release date: January 11, 2008 [eBook #24252]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from scans of public domain material produced by

Microsoft for their Live Search Books site.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOUR YOUNG EXPLORERS; OR, SIGHT-SEEING IN THE TROPICS ***

ALL-OVER-THE-WORLD LIBRARY

——————

Illustrated, Price per Volume $1.25

FIRST SERIES

A MISSING MILLION

Or The Adventures of Louis Belgrave

A MILLIONAIRE AT SIXTEEN

Or The Cruise of the Guardian Mother

A YOUNG KNIGHT-ERRANT

Or Cruising in the West Indies

STRANGE SIGHTS ABROAD

Or A Voyage in European Waters

SECOND SERIES

AMERICAN BOYS AFLOAT

Or Cruising in the Orient

THE YOUNG NAVIGATORS

Or The Foreign Cruise of the Maud

UP AND DOWN THE NILE

Or Young Adventurers in Africa

ASIATIC BREEZES

Or Students on the Wing

THIRD SERIES

ACROSS INDIA

Or Live Boys in the Far East

HALF ROUND THE WORLD

Or Among the Uncivilized

FOUR YOUNG EXPLORERS

Or Sight-seeing in the Tropics

OTHER VOLUMES IN PREPARATION

ANY VOLUME SOLD SEPARATELY

——————

LEE AND SHEPARD Publishers Boston

[i]

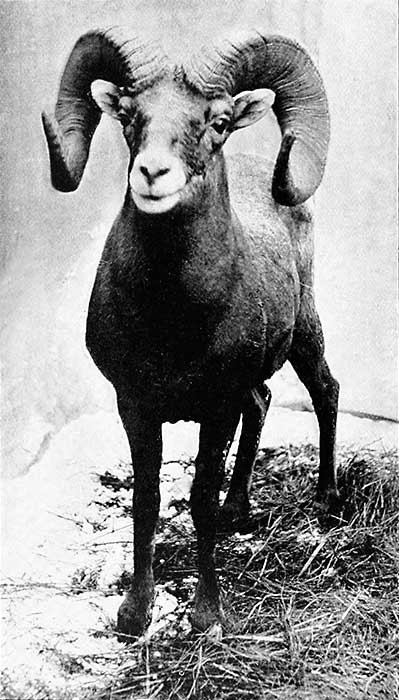

"Your first shot, Louis," said Scott.

Page 30.

[ii]

Four Young Explorers

OR

SIGHT-SEEING IN THE TROPICS

BY

OLIVER OPTIC

AUTHOR OF

"THE ARMY AND NAVY SERIES" "YOUNG AMERICA ABROAD, FIRST AND SECOND

SERIES" "THE BOAT-CLUB STORIES" "THE ONWARD AND UPWARD SERIES"

"THE GREAT WESTERN SERIES" "THE WOODVILLE STORIES" "THE

LAKE SHORE SERIES" "THE YACHT-CLUB SERIES" "THE RIVERDALE

STORIES" "THE BOAT-BUILDER SERIES" "THE BLUE AND THE GRAY

AFLOAT" "THE BLUE AND THE GRAY—ON LAND" "THE STARRY

FLAG SERIES" "ALL-OVER-THE-WORLD LIBRARY, FIRST SECOND

AND THIRD SERIES" COMPRISING "A MISSING MILLION" "A

MILLIONAIRE AT SIXTEEN" "A YOUNG KNIGHT-ERRANT"

"STRANGE SIGHTS ABROAD" "AMERICAN BOYS AFLOAT"

"THE YOUNG NAVIGATORS" "UP AND DOWN THE

NILE" "ASIATIC BREEZES" "ACROSS INDIA"

"HALF ROUND THE WORLD" ETC., ETC., ETC.

——————

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD PUBLISHERS

10 MILK STREET

1896

[iii]

Copyright, 1896, by Lee and Shepard

——————

All Rights Reserved

——————

Four Young Explorers

Typography by C. J. Peters & Son, Boston.

——————

Presswork by Berwick & Smith.

[iv]

TO

MY APPRECIATIVE AND VALUED FRIEND

FREDERICK D. RUGGLES, ESQ.

RESIDING ON A HISTORIC HILL IN

HARDWICK, MASS.

This Volume

IS RESPECTFULLY AND CORDIALLY

DEDICATED.

[v]

PREFACE

"FOUR YOUNG EXPLORERS" is the third

volume of the third series of the "All-Over-the-World

Library." When the young millionaire and

his three companions of about his own age, with a

chosen list of near and dear friends, had made the

voyage "Half Round the World," the volume with

this title left them all at Sarawak in the island

of Borneo. The four young explorers, as they became,

were permitted to spend three weeks there

hunting, fishing, and ascending some of the rivers,

while the rest of the party proceeded in the Guardian-Mother

to Siam. The younger members of

the ship's company believed they had seen enough

of temples, palaces, and fine gardens in the great

cities of the East, and desired to live a wilder life

for a brief period.

They were provided with a steam-launch, prepared

for long trips; and they ascended the Sarawak,

the Sadong, and the Simujan Rivers, and had all

the hunting, fishing, and exploring they desired.

They visited the villages of the Sea and Hill Dyaks,

and learned what they could of their manners and

customs, penetrating the island from the sea to[vi]

the mountains. They studied the flora and the

fauna of the forests, and were exceedingly interested

in their occupation for about a week, when

they came to the conclusion that "too much of a

good thing" became wearisome; and, more from the

love of adventure than for any other reason, they

decided to proceed to Bangkok, and to make the

voyage of nine hundred miles in the Blanchita, as

they had named the steam-launch, which voyage

was accomplished without accident.

After the young explorers had looked over the

capital of Siam, the Guardian-Mother and her consort

made the voyage to Saigon, the capital of

French Cochin-China, where the visit of the tourists

was a general frolic, with "lots of fun," as the

young people expressed it; and then, crossing the

China Sea, made the port of Manila, the capital of

the Philippine Islands, where they explored the

city, and made a trip up the Pasig to the Lake of

the Bay. From this city they made the voyage

to Hong-Kong, listening to a very long lecture on

the way in explanation of the history, manners, and

customs, and the peculiarities of the people of China.

They were still within the tropics, and devoted themselves

to the business of sight-seeing with the same

vigor and interest as before. But most of them

had read so much about China, as nearly every

American has, that many of the sights soon began

to seem like an old story to them.[vii]

Passing out of the Torrid Zone, the two steamers

proceeded to the north, obtaining a long view of

Formosa, and hearing a lecture about it. Their

next port of call was Shang-hai, reached by ascending

the Woo-Sung. From this port they made an

excursion up the Yang-tsze-Chiang, which was an exceedingly

interesting trip to them. The ships then

made the voyage to Tien-tsin, from which they

ascended by river in the steam-launch to a point

thirteen miles from Pekin, going from there to the

capital by the various modes of conveyance in use

in China. They visited the sights of the great city

under the guidance of a mandarin, educated at Yale

College. Some of the party made the trip to the

loop-wall, near Pekin. Returning to Tien-tsin, with

the diplomatic mandarin, who had accepted an invitation

to go to Japan in the Guardian-Mother, they

sailed for that interesting country, where the next

volume of the series will take them.

It may be necessary to say that the Guardian-Mother,

now eighteen months from New York, and

half round the world, reached Tien-tsin May 25,

1893; and therefore nothing relating to the late war

between China and Japan is to be found in this

volume. Possibly the four young explorers would

have found more sights to see, and more adventures

to enjoy, if they had struck either of the belligerent

nations during the war; but the ship sailed for the

United States before hostilities were begun.[viii]

Of course the writer has been compelled to consult

many volumes in writing this book; and he takes

great pleasure in mentioning among them the very

interesting and valuable work of Mr. W. T. Hornaday,

the accomplished traveller and scientist, "Two

Years in the Jungle." This book contains all that

one need know about Borneo, to say nothing of the

writer's trip in India among the elephants. His

researches in regard to the orang-outang appear to

have exhausted the subject; though I do not believe

he has found the "missing link," if he is looking

for it. Professor Legge contributed several articles

to "Chambers's Encyclopædia," which contain the

most interesting and valuable matter about China to

be derived from any work; for he lived for years in

that country, travelled extensively, and learned the

language. I am under great obligations to these

authors.

The author is under renewed obligations to his

readers, young and old, who have been his constant

friends during more than forty years, for the favor

with which they have received a whole library of

his books, and for the kind words they have spoken

to him, both verbally and by letter.

WILLIAM T. ADAMS.

Dorchester, Mass.

[ix]

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Borneo Hunters and Explorers | 1 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| A Voyage Up the Sarawak River | 10 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| Something About Borneo and Its People | 19 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| A Speculation in Crocodiles | 29 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| A Hundred and Eight Feet of Crocodile | 39 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Voyage Up the Sadong To Simujan | 48 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| A Spirited Battle With Orang-outangs | 58 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| [x]A Performance of Very Agile Gibbons | 67 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| A Visit to a Dyak Long-House | 77 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| The Manners and Customs of the Dyaks | 87 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| Steamboating through a Great Forest | 96 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| A Formidable Obstruction removed | 106 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Captain's Astounding Proposition | 115 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Down the Simujan and up the Sarawak | 125 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| On the Voyage to Point Cambodia | 134 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| An Exciting Race in the China Sea | 143 |

CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The End of the Voyage to Bangkok | 153 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Louis's Double-Dinner Argument | 163 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

| [xi]A Hasty Glance at Bangkok | 172 |

CHAPTER XX. | |

| A View of Cochin-China and Siam | 181 |

CHAPTER XXI. | |

| On the Voyage To Saigon | 191 |

CHAPTER XXII. | |

| In the Dominions of the French | 201 |

CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| A Lively Evening at the Hotel | 211 |

CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Tonquin and Sights in Cholon | 221 |

CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Several Hilarious Frolics | 231 |

CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| The Voyage across the China Sea | 241 |

CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Some Account of the Philippines | 250 |

CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| The Description of an Earthquaky City | 260 |

CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Going on Shore in Manila | 270 |

CHAPTER XXX. | |

| [xii]Excursions on Shore and up the Pasig | 280 |

CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Half a Lecture on Chinese Subjects | 290 |

CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| The Continuation of the Lecture | 300 |

CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| The Conclusion of the Lecture | 310 |

CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Sight-seeing in Hong-Kong and Canton | 321 |

CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Shang-Hai and the Yang-tsze-Chiang | 332 |

CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| The Walls and Temples of Pekin | 342 |

[xiii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| "Your first shot, Louis," said Scott | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| "What have you got there, Mr. Belgrave?" | 41 |

| "You are near enough, Captain" | 99 |

| The boat rose gracefully on the billows | 132 |

| "But where is Felix?" demanded Mrs. Blossom, | 161 |

| She made a vigorous leap into the fore-sheets, | 267 |

| Natives preparing tobacco in Manila | 285 |

| Temple and garden in China | 329 |

[1]

FOUR YOUNG EXPLORERS

CHAPTER I

THE BORNEO HUNTERS AND EXPLORERS

The Guardian-Mother, attended by the Blanche,

had conveyed the tourists, in their voyage all over

the world, to Sarawak, the capital of a rajahship

on the north-western coast of the island of Borneo.

The town is situated on both sides of a river of the

same name, about eighteen miles from its mouths.

The steamer on which was the pleasant home of

the millionaire at eighteen, who was accompanied by

his mother and a considerable party, all of whom

have been duly presented to the reader in the former

volumes of the series, lay in the middle of the

river. The black smoke was pouring out of her

smokestack, and the hissing steam indicated that

the vessel was all ready to go down the river to the

China Sea. Her anchor had been hove up, and

the pilot was in the pilot-house waiting for the commander

to strike the gong in the engine-room to start

the screw.

Just astern of the Guardian-Mother was a very[2]

trim and beautiful steam-launch, fifty feet in length.

The most prominent persons on board of her were

the quartette of American boys, known on board of

the steamer in which they had sailed half round the

world as the "Big Four." Of this number Louis

Belgrave, the young millionaire, was the most important

individual in the estimation of his companions,

though happily not in his own.

Like a great many other young men of eighteen,

which was the age of three of them, while the fourth

was hardly sixteen, they were fond of adventure,—of

hunting, fishing, and sporting in general. They had

gone over a large portion of Europe, visited the

countries on the shores of the Mediterranean, crossed

India, and called at some of the ports of Burma, the

Malay peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Celebes, and had

reached Sarawak in their explorations.

They had visited many of the great cities of the

world, and seen the temples, monuments, palaces, and

notable structures of all kinds they contain; but

they had become tired of this description of sight-seeing.

When the island of Borneo was marked on

the map as one of the localities to be visited, the

"Big Four" had a meeting in the boudoir, as one of

the apartments of the Guardian-Mother was called,

and voted that they had had enough of temples,

monuments, and great cities for the present.

They agreed that exploring a part of Borneo, with

the incidental hunting, fishing, and study of natural

history, would suit them better. Louis Belgrave was[3]

appointed a committee of one to petition the commander

to allow them three weeks in the island for

this purpose. Captain Ringgold suggested to Louis

that it was rather selfish to leave the rest of the

party on the steamer, stuck in the mud of the Sarawak,

while they were on the rivers and in the woods

enjoying themselves.

But the representative of the "Big Four" protested

that they did not mean anything of the sort.

They did not care a straw for the temples and other

sights of Siam, Cambodia, and French Cochin-China;

and while they were exploring Borneo and shooting

orang-outangs, the Guardian-Mother should proceed

to Bangkok and Saigon, and the rest of the tourists

could enjoy themselves to the full in seeing the wonders

of Farther India.

It required a great deal of discussion to induce

the commander, and then the mothers of two of the

explorers, to assent to this plan; but the objections

were finally overcome by the logic and the eloquence

of Louis. The Blanche, the consort of the Guardian-Mother,

having on board the owner, known as General

Noury, his wife and his father-in-law, had

nothing to do with this difficult question; but the

general had a steam-launch, which he was kind

enough to grant for the use of the explorers.

The third engineer of the ship was to go with the

quartette, in charge of the engine; five of the youngest

of the seamen were selected to make the venture

safer than it might otherwise have been. Achang[4]

Bakir, a native Bornean, who had been picked up

off the Nicobar Islands, after the wreck of the dhow

of which he had been in command, was to be the

guide and interpreter.

The youngsters and their assistants had taken

their places on board of the "Blanchita," as Louis

had christened the craft, and she was to accompany

the two large steamers down the river. But the

farewells had all been spoken, the hugging and

kissing disposed of, and the tears had even been

wiped away. The mothers had become in some

degree reconciled to the separation of three weeks.

The Guardian-Mother started her screw, and began

to move very slowly down the river, amid the cheers

and salutations of the officers, soldiers, and citizens

of the town. The Blanche followed her, and both

steamers fired salutes in honor of the spectators to

their departure. The Blanchita secured a position

on the starboard of the Guardian-Mother, and for

three hours kept up a communication with their

friends by signals and shouts.

Off the mouth of the Moritabas, one of the outlets

of the stream, the steamers stopped their screws, and

the "Big Four" went alongside of the Guardian-Mother;

the adieux were repeated, and then the

ships laid the course for their destination. Both of

the latter kept up an incessant screaming with their

steam whistles, and the party on board of them

waved their handkerchiefs, to which the "Big Four,"

assisted by the sailors, responded in like manner,[5]

while the engineer gave whistle for whistle in feeble

response.

When the whistles ceased, and the signals could

no longer be seen, the Blanchita came about, and

headed for the Peak of Santubong on the triangular

island formed by the two passes of the Sarawak

River. The explorers watched the ships till they

could no longer be seen, and then headed up the river.

"Faix, the bridges betune oursels and civiloization

are all broke down!" exclaimed Felix McGavonty,

who sometimes used his Milesian dialect in order,

as he put it, not to lose his mother's brogue.

"Not so bad as that, Felix; for there is considerable

civilization lying around loose in Borneo," replied

Louis Belgrave.

"Not much of it here is found," added Achang

Bakir, the Bornean.

"Is found here," interposed Morris Woolridge,

who had been giving the native lessons in English,

for he mixed with it the German idiom.

"Rajah Brooke has civilized the region which he

governs, and the Dutch have done the same in portions

of their territory. Professor Giroud gave us

the lecture on Borneo, and we shall have occasion to

review some of it," added Louis. "But I think we

had better give some attention to the organization of

our party for the trip up the Sarawak River."

"I move, Mr. Chairman, that we have the same

organization we had on board of the Maud," interposed

Felix, dropping his brogue. "That means[6]

that Mr. Scott shall be captain, and Morris mate,

while Louis and myself shall be the deck-hands."

"Mr. Chairman, I move an amendment to the motion,

to the effect that Louis shall be captain, while

I serve as deck-hand," said Scott.

"I hope the amendment will be voted down, and

that the original motion will prevail," Louis objected.

"Captain Scott, in command of the Maud,

on a voyage of two thousand miles, proved himself

to be an able and skilful commander, as well as a

prudent and successful leader in several difficult situations.

He is the right person for the position.

Question! Those in favor of the amendment of

Mr. Scott will signify it by raising the right hand."

Scott voted for his own motion, and he was the

only one.

"Contrary minded, by the same sign," continued

Louis, raising his right hand, Felix and Morris voting

the same. "The amendment is lost. The question

is now on the original motion of Felix. Those

in favor of its adoption will signify it."

Three hands appeared, the motion was carried,

and the chairman informed Scott and Morris that

they were chosen captain and mate. Scott was outvoted,

and he made no further objection. Of the

five seamen on board he appointed Pitts cook and

steward, in which capacity he had served on board

of the Maud. The starboard is the captain's watch;

though the second mate, when there is one, takes his

place for duty, and the port is the mate's watch.[7]

"I select Clingman for the first of my watch,"

continued Scott. "Your choice next, Morris."

"Wales," said the mate.

"Lane for the starboard," added Scott.

"Hobson's choice," laughed Morris, as he took

the last man. "Clinch for the port; the last, but

by no means the least."

"I fancy the watches will have an easy time of

it; for I suppose we shall not do much running up

and down these rivers, and through dark forests, in

the night," suggested Louis.

"If we lie up in the night, I shall divide them

both into quarter-watches, and have one man on

duty all the time; for we may be boarded by a huge

crocodile or a boa-constrictor if we are not on the

lookout. But Achang is a pilot for these rivers.

Isn't that so, Captain Bakir?"

"I have been up and down all the rivers in this

part of the island, though I was not shipped as a

pilot then," replied Achang, who had been the captain

of a dhow, and on board the ship he had been

called by his first name or the other with the title.

"All right; we shall use you for pilot or interpreter

as occasion may require; and I suppose you

can tell us all we want to know about the country

and the people," added the captain.

Clinch, one of the ablest seamen on board, was

steering the launch, and Scott kept the run of the

courses; but as long as the craft had three feet of

water under her, she was all right. The conversation[8]

took place in the cabin, as the explorers called the

after part of the steamer, though no such apartment

had been built there.

A frame constructed of brass rods, properly

braced, extended the entire length of the launch.

A stanchion at the bow and another at the stern,

with five on each side set in the rail, supported a rod

the whole distance around the craft. Another extended

from the bow to the stern stanchion, directly

over the keel, about six inches higher than those at

the sides. Ten rods led from the central down to

the side rods, like the rafters of a house.

Over the whole, of this structure above was extended

a single piece of painted canvas, serving as a

roof, and keeping out both sun and rain. It was

laced very taut to the rods, and had slope enough to

make the water run off. On the sides were curtains,

which could be hauled down tight. The launch had

been used by the rajah on the Ganges, and when

closed in the interior was like "a bug in a rug."

Thus closed in, the standing-room was called the

cabin. It was surrounded by wide cushioned seats,

which made very good beds at night. Between these

divans was a table where the meals of the explorers

were to be served. Under the seats were many

lockers for all sorts of articles, the bedding, and the

arms and ammunition.

Just forward of the cabin were the engine and

boiler, with bunkers on each side for the coal. In

the middle of the craft was abundant space. The[9]

forward part of the boat was provided with cushioned

divans, where passengers could sit by day or

sleep at night; and this space was appropriated to

the sailors. In the centre of it was the wheel.

Next to it was the galley, with a stove large enough

to cook for a dozen persons, and all needed utensils.

The ship's company had looked the craft over

with great interest, and all of them were well

pleased with the arrangements. The launch had

been put into the water and fitted up for use the

day before. The party from both ships had visited

her, and almost wished they were to go to the interior

of the country in her.

The Blanchita continued on her course up the

river. Pitts was at work in the galley; and as soon

as the launch was made fast off the "go-down," or

business building of the town, dinner was served to

the seamen, and later to the denizens of the cabin.

The afternoon was spent in examining the place,

and in obtaining such supplies as were needed; for

the boat was to sail on her voyage up the river early

the next morning.

With the assistance of Achang, a small sampan, a

kind of skiff, was purchased; for the Bornean declared

that it would be needed in the hunting excursions

of the party, for much of the country was

flooded with water, a foot or two in depth.[10]

CHAPTER II

A VOYAGE UP THE SARAWAK RIVER

The young hunters slept on board of the Blanchita,

and they were delighted with their accommodations.

Sarawak, or Kuching, the native name of

the town, is only about one hundred and fifty miles

north of the equator, and must therefore be a very

warm region, though away from the low land near

the sea-coast it is fairly healthy. The party slept

with the curtains raised, which left them practically

in the open air.

Achang had given them a hint on board of the

ship that mosquitoes were abundant in some localities

in Borneo. The Guardian-Mother was provided with

the material, and the ladies had made a dozen mosquito

bars for the explorers. They were canopies,

terminating in a point at the top, where they were

suspended to the cross rods on which the canvas roof

was supported. The netting was tucked in under the

cushions of the divan, and the sleepers were perfectly

protected.

Captain Scott had carried out his plan in regard

to the watches. The cook was exempted from all

duty in working the little steamer; but each of the

other seamen was required to keep a half-watch of[11]

two hours during the first night on board. Clinch

was on watch at four in the morning. He called the

engineer at this hour, and Felipe proceeded at once

to get up steam. It was still dark, for the sun rises

and sets at six o'clock on the equator.

As soon as there was a movement on board, all

hands turned out forward. There were no decks to

wash down; and, if there had been, the water was

hardly fit, in the judgment of the mate, for this purpose,

for it was murky, and looked as though it was

muddy; but it was not so bad as it appeared, for the

dark color was caused by vegetable matter from the

jungles and forest, and not from the mud, which

remained at the bottom of the stream.

"The top uv the marnin' to ye's!" shouted Felix,

as he leaped from his bed about five o'clock,—for all

hands had turned in about eight o'clock in the evening,

as the mosquitoes, attracted by the lanterns,

began to be very troublesome,—and the Milesian

could sleep no longer.

"What's the matter with you, Flix?" demanded

the captain.

"Sure, if ye's mane to git under way afore night,

it's toime to turn out," replied Felix. "Don't ye's

hear the schtaym sizzlin' in the froy'n pan?"

"But it isn't light yet," protested Scott.

"Bekase the lanthern in the cab'n bloinds your

two oyes, and makes the darkness shoine broighter

nor the loight," said Felix, as he looked at his

watch. "Sure, it's tin minutes afther foive in the[12]

marnin'. These beds are altogidther too foine,

Captain."

"How's that, Flix?" asked Scott, as he opened the

netting and leaped out of bed.

"They're too comfor-ta-ble, bad 'cess to 'em, and

a b'y cud slape till sundown in 'em till the broke o'

noight."

"Dry up, Flix, or else speak English," called Louis,

as he left his bed. "There is no end of 'paddies'

along this river, and I'm sure they cannot understand

your lingo."

"Is it paddies in this haythen oisland?" demanded

Felix, suspending the operation of dressing himself,

and staring at his fellow deck-hand. "I don't belayve

a wurrud of ut!"

"Are there no paddies up this river, Achang?"

said Louis, appealing to the Bornean.

"Plenty of paddies on all the streams about here,"

replied the native.

"And they can't oondershtand Kilkenny Greek!

They're moighty quare paddies, thin."

"They are; and I am very sure they won't answer

you when you speak to them with that brogue,"

added Louis.

"We will let that discussion rest till we come to

the paddies," interposed the captain, as he completed

his toilet, and left the cabin.

By this time all the party had left their beds and

dressed themselves; for their toilet was not at all

elaborate, consisting mainly of a woollen shirt, a pair[13]

of trousers, and a pair of heavy shoes, without socks.

Felipe had steam enough on to move the boat; and

the seamen had wiped the moisture from all the

wood and brass work, and had put everything in

good order.

"Are you a pilot for this river, Achang?" asked

Scott, as the party came together in the waist, the

space forward of the engine.

"I am; but there is not much piloting to be done,

for all you have to do is to keep in the middle of the

stream," replied the Bornean. "I went up and down

all the rivers of Sarawak in a sampan with an English

gentleman who was crocodiles, monkeys, mias,

snakes, and birds picking up."

"Wrong!" exclaimed Morris. "You know better

than that, Achang."

The native repeated the reply, putting the verb

where it ought to be.

"He was a naturalist," added Louis.

"Yes; that was what they called him in the

town."

"I think we all know the animals of which you

speak, Achang, except one," said Louis. "I never

heard of a mias."

"That is what Borneo people call the orang-outang,"

replied the native.

"Orang means a man, and outang a jungle, and

the whole of it is a jungle man," Louis explained,

for the benefit of his companions; for he was better

read in natural history than any of them, as he had[14]

read all the books on that subject in the library of

the ship. "In Professor Hornaday's book, 'Two

Years in the Jungle,' which was exceedingly interesting

to me, he calls this animal the 'orang-utan,'

which is only another way of spelling the second

word."

"Excuse me, Louis, but I think we will get under

way, and hear your explanations at another time,"

interposed Captain Scott.

"I have finished all I had to say."

"Take the wheel, Achang," continued the captain.

The sampan was sent ashore to cast off the fasts.

The river at the town is over four hundred feet

wide, and deep enough in almost any part for the

Blanchita. As soon as the lines were hauled in, the

captain rang one bell, and Felipe started the engine.

The helmsman headed the boat for the middle of the

stream, and the captain rang the speed-bell. When

hurried, the Blanchita was good for ten knots an

hour, but her ordinary speed was eight.

On the side of the river opposite Kuching, or Sarawak,

was the kampon of the Malays and other natives;

and the term means a division or district of

a town. Many of the natives of this village had

visited the Blanchita,—some for trade, some for employment,

and some from mere curiosity. None of

them were allowed to go on board of the launch; for,

while the Dyaks are remarkably honest people, the

Malays and Chinese will steal without any very

heavy temptation.[15]

Achang headed the boat up the river. For five

miles the banks were low, with no signs of cultivation,

and bordered with mangroves. At this point

the captain called Lane to the wheel, with orders to

keep in the middle of the river. The "Big Four"

had taken possession of the bow divans, the better

to see the shores. They were more elevated, which

simply means higher above the water.

"When shall we come across the paddies, Achang?"

asked Felix; "for I am very anxious to meet them,

and maybe we shall have a Kilkenny fight with

them."

"No, you won't, for you speak English," replied

Louis.

"The paddies are here on both sides of the river,"

added Achang.

"I don't see a man of any sort, not even a Hottentot,

and I am sure there is not a Paddy in sight."

"Your education has been neglected, Flix, and you

did not read all the books in the ship's library," said

Louis. "I only told you the paddies would not answer

you if you spoke to them with a brogue. You

can try them now if you wish."

"But I don't see a single Paddy to try it on."

"Here is one on your left."

"I don't see anything but a field of rice."

"That's a paddy in this island."

"A field of rice!"

"Achang will tell you that is what they call them

in Borneo."[16]

"Bad luck to such Paddies as they are! But it

looks as though there might be some Paddies here,

for the houses are very neat and nice, just as you see

in old Ireland."

"Certainly they are; but I never saw any such in

Ireland," added Louis. "You remember the old

woman on the road from Killarney to the lakes who

told us she lived in the Irish castle, to which she

pointed; and it looked like a pig-sty."

"Of course it didn't have the bananas and the

cocoanut-palms around it."

"I admit that we saw many fine places in Ireland,

and very likely your mother lived in one of them.

But, Achang, is there any game in the woods we see

beyond the paddies?"

"Sometimes there is plenty of it; at others there

is scarcely any. You can get squirrels here and

some birds."

"Any orang-outangs?"

"We found none when we came up the river, for

this is not the best place for them. If we run up

the Sadong and Samujan Rivers, you will find

some," replied the Bornean. "I don't think it will

pay to go very far up the Sarawak, if it is game you

want; but you can see the country. There is quite

a village on the right."

The party were very much interested in examining

the houses they saw on the borders of the

stream. Like those they had seen in Java and in

Sumatra, they were all set up on stilts. A Malay or[17]

Dyak will not build his home on dry land, as they

noticed in coming up the lower part of the river,

though there was plenty of elevated ground near.

The dwellings were all built on the soft mud.

The village ten miles up-stream was constructed on

the same plan. The houses were placed just out of

the reach of the water when it was higher than usual.

The material was something like bamboo, as in India,

with roofs of kadjang leaves, which abound in

the low lands. In front of every one of them was a

flat boat—sampan; and one was seen which was

large enough to have a roof of the same material as

the house. The boats were made fast to a pole set in

the mud.

"There is a bear on the shore!" shouted Morris,

with no little excitement in his manner, as he pointed

to the woods on the shore opposite the houses, to

which the attention of all the rest of the party had

been directed.

At the same time he seized his repeating rifle, and

all the others followed his example. The animal

was fully three feet high, and at a second glance it

did not look much like a bear. Whatever it was, it

took to its heels when the sound of the steamer's

screw reached its ear. But Morris fired before the

boat started, and the others did the same.

"That is not a bear, Mr. Morris," interposed

Achang, laughing as he spoke.

"What is it, then?" demanded Morris.

"A pig."[18]

"A pig three feet high!" exclaimed the hunters

with one voice.

"A wild pig," added the Bornean.

"Is he good for anything?" inquired Scott.

"He is good to eat if you like pork."

"He dropped in the bushes when we fired. Can't

we get him?" asked Morris.

Under the direction of the captain the steamer

was run up to the shore; and the bank in this place

was high enough to enable the party to land without

using the sampan. All hands, including the seamen,

rushed in the direction of the spot where the pig

had been seen. The game was readily found. The

animal was something like a Kentucky hog, often

called a "racer," because he is so tall and lank.

He was a long-legged specimen; and Achang said

that was because they hunted through swamps and

shallow water in search of food, and much use had

made their legs long. He added that they were a

nuisance because they rooted up the rice, and farmers

had to fence their fields.

He was carried on board by the sailors, and Pitts

cut out some of the nicer parts of the pig. They

had roast pork for dinner, but it was not so good as

civilized hogs produce.[19]

CHAPTER III

SOMETHING ABOUT BORNEO AND ITS PEOPLE

"I don't think we know much of anything about

Borneo," said Scott, as the Blanchita continued on

her course up the Sarawak, after the dinner of roast

pork.

"We all heard the lecture of Professor Giroud on

board the ship," replied Louis.

"I should like to hear it over again, now that we

are on the ground," added the captain.

"Sure, we're not on the ground, but on the

wather," suggested Felix.

As the reader did not hear the lecture, or see it

in print, it becomes necessary to repeat it for the

benefit of "whom it may concern." The professor,

after being duly presented to his audience in Conference

Hall, proceeded as follows:—

"Australia is undoubtedly the largest island in

the world, and some geographers class it with the

continents; but Chambers makes Borneo the third

in size, while most authorities rate it as the second,

making Papua, or New Guinea, the second in extent.

Lippincott says Papua disputes with Borneo the

claim to the second place among the great islands of

the world; and I do not propose to settle the question.[20]

Chambers gives the area of Borneo at 284,000

square miles, the population in the neighborhood of

200,000, and the dimensions as 800 by 700 miles.

"It has a coast-line of about 3,000 miles, nearly

the whole of which is low and marshy land. A

large portion of the island is mountainous, as you

may see by looking at the map before you;" and

the professor indicated the several ranges with the

pointer. "One chain extends nearly the whole

length of the island, dividing in the middle of it

into two branches, both of which almost reach the

sea on the south. Near the centre of the island

are two cross ranges, one extending to the east, and

the other to the south-west. It would be useless to

mention the Malay names of these ranges, for you

could not remember them over night. The general

idea I have given you is quite enough to retain.

"The interior of Borneo is but little known; and

when Mr. Gaskette makes another map of the island

twenty or thirty years hence, it will probably differ

considerably from the one before you. In the extreme

north is the peak of Kini Balu, the height of

which is set down at 13,698 feet, with an interrogation

point after it. Other mountains are estimated

to be from 4,000 to 8,000 feet high. There are no

active volcanoes.

"In the low lands on the coast, it is hot, damp, and

unhealthy for those who are not acclimated; but in

the high lands among the mountains, the temperature

is moderate, from 81° to 91° at noon, and it is sometimes[21]

worse than that in New York. From November

to May, which is the rainy season, violent storms

of wind with thunder-showers prevail on the west

coast. In hot weather the sea-breezes extend a considerable

distance inland. Vegetation is remarkably

luxuriant, as our young hunters will find in their

explorations. The forests produce all the woods of

the Indian Archipelago, of which you know the

names by this time. Bruneï, on the north-west

coast, produces the best camphor in Asia, which is

about the same as saying in the world."

"What is camphor, Professor?" asked Mrs. Belgrave.

"I have used it all my life, but I have not

the least idea what it is."

"Camphor is an oil found in certain plants, mostly

from the camphor laurel. This oil is separated from

the plant, and then undergoes the process of refining.

It is mixed with water, and then boiled in a sort of

retort. It makes steam, which is allowed to escape

through a small aperture, which is then closed, and

the camphor becomes solid in the upper part of the

vessel. This is the article which is sent to market.

"All the spices and fruits of the Torrid Zone are

produced in Borneo, with cotton and sugar-cane in

certain parts. The animals of the island are about

the same as in other parts of the Archipelago. The

monkey tribe is the most abundant, including the

simia, the gibbon, the orang-outang, found in no

other island, except very rarely in Sumatra, where

our hunters did not find even one; tapirs"[22]—

"What are they?" asked Uncle Moses.

"They are a sort of cross between an elephant and

a hog. They are found all over South American

tropical regions and in this part of Asia. The animal

is more like a hog than like an elephant, though

it has the same kind of a skin as the latter. It is

about the size of the average donkey. It has a snout

which is prehensile, like the trunk of an elephant,

but on a very small scale.

"What does that mean?" asked Mrs. Blossom.

"Capable of taking hold of anything, as the elephant

does with his proboscis. The tapir is one of

the gentler animals, and may be easily tamed; though

it will fight and bite hard when attacked, or harried

by dogs. They take to the water readily, though the

American swims, while the Asiatic only walk on the

bottom. One book I consulted calls the tapir a kind

of tiger, to which he bears hardly any resemblance.

"The other animals are small Malay bears, wild

swine, horned cattle, and puny deer. The elephant

and rhinoceros are found, few in number, in the

north. The birds are the eagle, vulture, argus-pheasant,—a

singular and beautiful bird,—peacocks,

flamingoes, and swifts."

"What in the world are swifts?" inquired Mrs.

Woolridge.

"They are a kind of swallow, of which you may

have seen some as we came down from Rangoon.

They make the edible birds'-nests which are so great

a delicacy among the Chinese when made into soup.[23]

The rivers, lakes, and swamps swarm with crocodiles,

the real man-eaters. Leeches are a nuisance when

you bathe in the rivers and ponds, and various kinds

of snakes abound. There are plenty of fish in the

sea, lakes, and rivers. Diamonds, gold, coal, copper,

are mined in the island.

"All of New England and the Middle States, with

Maryland, could be set down in Borneo, still leaving

a considerable border of swamp and jungle all around

them. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and

Ireland could be slapped down upon it like a flapjack,

and there would still be more than space for

another United Kingdom, without covering up all the

mud of Borneo. We do not see how big it is when

we look on the map.

"The larger portion of the island is included in

the Dutch possessions. Banjermassin, of which

something was said as we passed the mouth of the

Barito River, on which it is located, contains 30,000

inhabitants, and is the most important in the island.

Borneo proper is in the north-west, and is under the

government of the Sultan of Bruneï. He lost nearly

one-half of his territory, taken by the North Borneo

Company, and that in the west, which is now Sarawak,

of which I shall have something more to say

later. The island of Labuan lies six miles west of

the northern portion of Bruneï. It was ceded to

the English by the sultan, and is principally valuable

as a coaling-station, though it has a considerable

trade.[24]

"Sabah is the country of the North Borneo Company.

An American obtained the right to this

territory in 1865, and transferred it to the present

company. It has an area somewhat larger than the

State of Maine. No doubt they will develop and

improve the country.

"Sarawak has a territory nearly as large as that

of the State of Pennsylvania, and larger than the

State of Ohio. Its history is involved in the life

of Sir James Brooke, who was originally created the

rajah, or governor of the country, by the Sultan of

Bruneï, and retained the title till his death in 1868.

He was born in Benares in 1803, and educated at

Norwich, England. In 1819 he entered the East

Indian army, and was severely wounded in the Burmese

war. He returned to England; and his furlough

lapsed before he could rejoin his regiment,

and with it his appointment. He left the service.

He next conceived a plan for putting down piracy

in the Indian Archipelago, and of civilizing the savage

inhabitants of these islands, a grand and noble

scheme to be carried out by a single individual on

his own responsibility.

"He bought a small vessel, and made a voyage

to China, probably with the intention of improving

his finances for the work he had in view. In 1835

he inherited $150,000 at the death of his father.

After a cruise in the Mediterranean, he sailed in a

schooner-yacht from London for Sarawak, where he

arrived in 1839. The uncle of the sultan was engaged[25]

in a war with some tribes of rebels, and

Brooke rendered him important assistance. He

returned to Kuching with the title of rajah, his

predecessor, a native, having been compelled to

resign.

"The new governor immediately went to work

very vigorously to establish a better government,

introducing free trade, and framing a new code of

laws. At this time the atrocious custom of head-hunting

prevailed in the island. Enemies killed in

battle were decapitated simply for the sake of the

head, and the Dyak who obtained the greatest

number of them was esteemed the most valiant

warrior.

"A Dyak girl would not accept the addresses of

a young man who had not obtained a head, in the

earlier time; and murders were often committed for

the sole purpose of obtaining the head of the victim,

either to conciliate some dusky maiden, or as a

trophy for the head-house, of which there is one

in every village. The heads were 'cooked,' as they

called it, though the operation was merely drying

and cleaning the skull. Rajah Brooke made the

penalty of this kind of murder death, without regard

to the customs and antecedents of the natives; and

he soon abolished head-hunting in his dominion.

"The sultan, either directly or by 'winking at it,'

encouraged piracy; and the crime was as common as

in the vicinity of the Malay states fifty years ago.

Sir James Brooke resolutely attacked the pirates,[26]

and with the means at his command soon vanquished

and drove them from the sea and the land. The

Dyaks, in spite of their head-hunting propensities,

were rather a simple people; while the Malays of

the island were cunning, dishonest, treacherous, and

cruel. The simple Dyaks were no match for them,

and were cheated and abused in every possible way.

There was no such thing as justice in the land. The

new rajah corrected all these abuses.

"Having established his government on the basis

of right and justice to all, Brooke went to England

in 1847. He was invited to Windsor by the Queen,

and created a K. C. B. (Knight Commander of the

Bath), a distinguished honor in Great Britain. The

next year he was made governor of Labuan. He

was charged in the House of Commons with receiving

head-money for pirates killed; but the charge

was disproved.

"Brooke continued to hold his position as Rajah of

Sarawak while at Labuan; but in 1857 he was superseded

at the latter, and returned to his government.

The Chinese, of whom there are a great many in

Borneo, became incensed against him because he prevented

the smuggling of opium into his territory. A

large body of them attacked his house in the night,

and destroyed a great amount of his property.

"But the rajah was not a man to submit quietly

to such an outrage. He immediately collected a

force of Dyaks and Malays, and attacked the Celestials.

He razed a fort they had constructed, and[27]

thoroughly defeated them in several successive battles.

He was very prompt and decided in action,

and to see an abuse was to remedy it without unnecessary

delay. He established and maintained a

model government, and the country prospered greatly

under his mild but decisive rule.

"He found a town with 1,000 inhabitants, and left

it with 25,000. He died in 1868, and was succeeded

by his nephew, Sir C. T. Brooke, who extended his

territory, and ten years ago placed it under the protection

of the United Kingdom. This is the history

of a noble man and a model colony."

"But what are Dyaks, Professor?" inquired Mrs.

Belgrave.

"They are natives of Borneo, though all the people

are not known by this name. They are divided

into Hill Dyaks and Sea Dyaks. At the present

time they are a high-toned class of savages; for they

do not steal or rob, and they have many social virtues

which might be copied by the people of enlightened

nations. Head-hunting and piracy are known

among them no more. They are the farmers and

producers of the island. There is much that is very

interesting about them. They build peculiar houses,

some of them occupied by a dozen or more families,

though they always live in peace, and do not quarrel

with their neighbors. The young women select their

own husbands, and a head is no longer necessary to

open the way to an engagement.

"If any of the party wish to learn more of the[28]

Dyaks, their manners and customs, present and past,

you will find a work in two volumes, by the Rev.

J. G. Wood, entitled, 'The Uncivilized Races of

Men;' and you will find that the author often

quotes from Rajah Brooke."[29]

CHAPTER IV

A SPECULATION IN CROCODILES

The Blanchita continued on her course up the

river with Clingman at the wheel. There was no

table in the fore cabin; and the dinner of the six

men, including the engineer, was served astern after

the "Big Four" had taken the meal. Louis attended

to the engine while Felipe was at his meals

and occasionally at other times. A table is not a

necessity for the crew of a ship, and one is not used

on board a merchant vessel; but Louis insisted that

all hands should fare equally well on board of the

little steamer.

The dinner was disposed of, and Wales was at the

wheel. The men had nothing to do, and a couple of

them had assisted Pitts in washing the dishes and

putting the after cabin in order. It was an idle

time, and the "Big Four" were anxious to have

something more exciting than merely sailing along

the river, the novelty of which had worn off; and

they had not long to wait for it.

"A crocodile ahead, Captain, on the port bow,

sir!" exclaimed Wales, the wheelman, whose duty

required him to keep a sharp lookout for any obstructions

in the stream.[30]

All of the party had their weapons within reach,

including the three seamen who were disengaged;

but the latter were not expected to use the rifles

till they were ordered to do so by the captain or

any one of the hunters. The occupants of the fore

cabin, the principal personages on board, had the

exclusive use of the forward part of the boat, though

the hands were at liberty to use the seats when they

were not required by any of the "Big Four." No

order to this effect had been given; but the men,

under the influence of the discipline on board of

the ship, had involuntarily adopted the system.

"Slow her down, Wales," said Scott, after he had

observed the situation of the saurian.

The wheelman rang the jingle-bell, and the boat

soon came down to half-speed. The five hunters,

including Achang, had their rifles ready for use,

though they still retained their seats. The reptile

was not asleep; and he appeared to have some

notions of his own, for he was not disposed to wait

for the coming of the boat. He settled down in the

dark water so that he could not be seen, but the

surface was disturbed by his movements.

"Port the helm, Wales," said the captain quietly.

"He is going across the river."

Presently he came to the surface again, and was

swimming towards the opposite shore. He kept his

head and a small portion of his back next to it above

the surface of the water, as the young hunters had

seen in Sumatra before.[31]

"Full speed; give her a spurt, Wales," said the

captain.

The wheelman rang the speed-bell, and then spoke

through the tube to the engineer. The boat suddenly

darted ahead under this instruction, and was

soon abreast of the reptile, who was not at first

disposed to change his tactics. He evidently realized

that he was pursued, and it seemed to make

him angry.

"The rascal has put his helm to port," said Wales.

"Look out there, in the waist!" shouted Scott to

the seamen, a couple of whom were seated on the

rail, with their legs dangling over the side of the

boat. "Never sit in that way, men, unless you

want to be carried to the hospital with a leg bitten

off."

"Will they bite, Captain?" asked Clinch.

"Bite? They are regular man-eaters on these

rivers."

"I used to go in swimming with the alligators on

the Alabama River; but they all kept their distance,"

added the seaman.

The two men drew in their legs and moved inboard.

Alligators, which are generally considered harmless

in the rivers of the Southern States, will bite at anything

hanging in the water. As Wales had suggested,

the crocodile had changed his course, and was now

headed directly for the Blanchita. He seemed to

have concluded that there was no safety for him in

flight, and he had decided to fight.[32]

"Your first shot, Louis," said Scott, who had not

even taken up his rifle, as if he thought there would

be no chance for him after the millionaire had fired.

Louis waited a minute or more till he could distinctly

see the eye of the crocodile, and then he fired.

As has so often been said before, he had been thoroughly

trained in a shooting-gallery, and was a dead

shot, as he had often proved during the voyage.

The bullet had evidently gone to his brain, for the

reptile floundered about for an instant, and then

moved no more. As Felix put it, he was "very

dead," though the word hardly admits of an intensifier.

"What are you going to do with him now?" asked

the Milesian.

"I don't think we want anything more of him;

but, like a poison snake, he is a nuisance that ought

to be abated," replied the captain. "I dare say the

rajah will be much obliged to us for making the

number of them even one less."

"How long is he?" Achang inquired, as he returned

his rifle to its resting-place.

"About ten feet," replied Louis.

"More than that," the captain thought. "I should

say twelve feet."

"Then he is worth eighteen shillings to you," added

the native.

"What is he good for, Achang?" asked Morris.

"He is good for nothing," replied the Bornean.

"The crocodile here eats men and women. Some are[33]

killed every year, and the government pays one and

sixpence apiece for the heads."

"That looks like a war of extermination upon

them," said Morris.

"I don't know what that is; but they want to kill

them all off," replied Achang, who had improved his

language so that his tutor seldom had to correct it.

"That is the same thing. They pay by the foot

for crocodiles here."

"The bigger they are, the more dangerous," suggested

Louis. "Let us haul him alongside, and see

how long he is."

The boat had stopped her screw before Louis

fired; and the captain directed Wales to lay her

alongside the saurian, which was done in a few

minutes. Ropes were passed under his head and

tail; and with a couple of purchases made fast to

the horizontal rods over the rail, close to the stanchions,

the carcass was hoisted partly out of the

water. The measure was taken with a line first, to

which Lane, who was a carpenter's assistant, applied

his rule, which gave twelve feet and two inches as

the length of the crocodile.

"That makes him worth eighteen shillings," said

Achang.

"About four dollars and a half," added Morris.

"We could make something hunting crocodiles. If

we could kill ten of them like that fellow it would

give us forty-five dollars."

Louis and Scott laughed heartily at this calculation,[34]

and thought the idea was derogatory to the

character of true sport, though they did not object

to turning their victims of this kind into money.

"Must we carry the carcass of this beast down

to Kuching in order to get the reward, Achang?"

asked Morris.

"The head will be enough; and they can tell how

long he is by the size of it."

"How shall we saw the head off? Can you do it,

Lane?"

"I can do that," interposed the Bornean, as he

went to a bundle of implements he had procured in

the town and from the natives.

He drew from it a very heavy sword, from which

he took off the covering of dry leaves, and applied

his thumb to the edge of the weapon. Then he

picked out a straw from some packing, and dropped

it off in pieces, as one tries his razor on a hair. It

appeared to be as sharp as the shaving-tool, and he

was satisfied. All hands watched his movements

with deep interest. He secured a position with one

foot on the side of the boat, and the other on the

back of the crocodile. With two or three blows of

his sword, he severed the head from the body, and

a seaman secured it with a boathook.

All hands applauded when the deed was done, as

the Bornean washed his keen blade. The operation

excited the admiration of all the lookers-on, it was

so quickly and skilfully done. Louis wished to examine

the weapon, and it was handed to him. It[35]

was heavy enough to require a strong arm to handle

it; and it was sharp enough for a giant's razor, if

giants ever shave, for most of them are pictured

with full beards.

"I suppose this is a native's sword," said Louis,

as he passed it to the captain.

"Dyak parong latok; parong same thing, not so

long," Achang explained.

"I suppose that is what the Dyaks used when

they went head-hunting," said Felix.

"No head-hunting now; used to use it, the Hill

Dyaks. Used in battle too; split head open with it,

or cut head off."

"What other weapons did the fighting men use?"

asked Louis.

"They carried a shield, and used a spear with

the parong latok; no other weapons. Two kinds of

Dyaks, the Sea and the Hill."

While the native was talking, the seamen, by order

of the captain, had hoisted the head of the saurian

into the sampan towing astern, placing it on a piece

of tarpaulin. The carcass was cast loose, and probably

was soon devoured by others of its own kind.

"We might find some eggs in the crocodile," said

Achang, as the body floated past the boat.

"We don't want the eggs," replied the captain,

turning up his nose.

"Good to eat, Captain. My naturalist used to

eat them. Very nice, like turtles' eggs, which Englishmen

always put in the soup."[36]

"None in my soup!" exclaimed Scott, with a wry

face, to express his disgust.

"I suppose they would be all right if we only got

used to them," suggested Louis.

"As the man's horse did when he fed him on shavings,"

sneered Scott.

"I did not take very kindly to turtles' eggs when

we were in the West Indies; but I got used to them,

and then liked them," added Louis. "In Africa the

natives eat boa-constrictors, and think they are a

choice morsel. Some of our Indians eat clay, and

I suppose they like it."

"Something up in the trees yonder, Captain,"

said Wales, as the boat approached some higher

ground, which was not overflown with water, as

most of the shore below had been.

"Monkeys," added Achang, not at all excited.

"I don't think I care to shoot monkeys unless it

is for the purpose of examining them," said Louis.

"They are too small game, and they are harmless

creatures."

"Strange monkeys in here," continued Achang.

"Not these," he added when he had obtained a sight

of one of them. "These no good."

All eyes were directed to the tree; and at least a

dozen common monkeys were there, such as they

had seen in the museums at home. The steamer

continued on her course, and a couple of miles farther

on the forest was inundated. Some of the trees

appeared to be inhabited.[37]

"Plenty of elephant monkeys in here," said

Achang.

"Elephant monkeys!" exclaimed Louis. "I never

heard of any such animals. Are they called so because

they are so large?"

"No, sir," said Achang; "because they have such

long noses."

"There are a dozen monkeys in that tree, and

they look very queer," said Louis, as he elevated

his double-barrelled fowling-piece, loaded with large

shot, and fired.

One of them dropped, and another when he discharged

the second barrel. The boat was run in the

direction of the tree till it grounded in the mud.

The captain proposed to go for them in the sampan,

when Clingman volunteered to wade to the tree for

the game, and soon returned with the two victims of

the millionaire's unerring aim. They were placed in

the waist, and all were curious to see them. The

rest of the tribe scampered away over the tops of the

trees, crying, "honk, honk, kehonk!"

"They are proboscis monkeys, and old males at

that; for they have very long noses, which is the

reason for the name, and why Achang calls them

elephant monkeys," said Louis, as he turned the

creatures over. "The noses of these two reach

down below the chin. They stand about three feet

high, but are rather lank, like the tall pigs."

While the party were examining them, the captain

gave the order to back the boat, and then to go[38]

ahead. She was moored for the night soon after.

The next morning, by the advice of Achang, the

Blanchita was headed down the river, for the native

declared that they would find no different game on

the banks of the Sarawak.[39]

CHAPTER V

A HUNDRED AND EIGHT FEET OF CROCODILE

The party were stirring as soon as it was daylight;

for in the tropics the early hours are the pleasantest,

and they had fallen into the habit of early rising in

India. The trees were alive with monkeys of several

kinds, though the proboscis tribe seemed to be in the

majority. Felix came out of the cabin with his gun

in his hand, and began to regard the denizens of

the tree-tops with interest.

"What are you going to do, Flix?" asked Louis,

who was sitting on the rail, busily cutting out a notch

in the end of a long piece of board.

"Don't you see there is plenty of game here, my

darling?" demanded Felix, pointing up into the

trees.

"Game!" exclaimed Louis contemptuously.

"Monkeys!"

"Didn't you shoot a couple of them yesterday

afternoon, Louis?"

"I did; but I wanted them in order to study the

creature. Now every fellow knows what a proboscis

monkey is, as he did not before except by name. I

got my books out, and read him up with the animal

before me. I am glad I did; for the picture of him[40]

I had seen was nothing like him in his nasal appendage,

which gives him his name."

"What is the reason of that?"

"The portrait was taken from a young one, before

his nose had attained its full growth. But I don't

believe in shooting monkeys for the fun of it. Our

party are not inclined to eat them."

"I'd as soon eat a cat as a monkey," added Felix.

"Then, don't shoot those long-nosed fellows, for

we have all the specimens of them we need," said

Louis.

"What are you going to do with them, my darling?

You can't keep them much longer, and you will have

to throw them overboard, for they won't smell sweet

by to-morrow."

"Achang learned something about taxidermy from

the naturalist he travelled with, and he has promised

to skin and mount one of them for me."

"But what's that you are making, Louis?" asked

Felix, who had been trying to take the measure of

the implement the young Crœsus was fashioning.

Its use was not at all evident. A triangular piece

had been sawed out of the end of a strip of board four

inches wide, and the rest of it had been cut down and

rounded off, and the thing looked more like a pitchfork

than anything else.

"Is it to pitch hay with?" persisted Felix.

"What have you got there, Mr. Belgrave?"

"No, it is not; when you see me use it, you will

know what it is for. You must wait till that time

before you know," replied Louis, who appeared to[41]

have finished the implement just as the other brought

his gun to his shoulder.

"That's the handsomest schnake I iver saw since

me modther, long life to her, left ould Ireland before

I was bahrn."

"Don't shoot him, Flix!" protested Louis vigorously.

"Where is he?"

"Jist forninst the bow of the boat. Sure, Oi'm

the schnake-killer of the party, and he's moi game."

"I don't want him killed yet," replied Louis, as he

moved forward from the waist with the forked stick

in his hand. "He is handsome, as you say, Flix."

Creeping very cautiously till he could see over the

bow, he discovered the serpent, which was nearly six

feet long, working slowly down a dead log towards

the water. Springing to his feet on the bow, he

struck down with his weapon, directing the fork at

the neck of the reptile. The outside of the log was

nothing but punk, or the operation would have been

a failure. As it was, the two points of the implement

sunk into the wood, and the snake was pinned in the

opening at the end of the stick.

"What have you got there, Mr. Belgrave?" asked

Achang, hurrying to the side of the operator.

"A snake; do you know him?" demanded Louis,

as the reptile struggled to escape.

"I saw one like it years ago;" and he gave a long

Dyak name to it which the others did not understand.

"Wait a minute or two, and I will bring him on

board for you."[42]

"I don't know that we want him on board," added

Louis.

"He is not poison, and he won't hurt you," said

the Bornean, as he made a slip-noose at the end of a

piece of cord.

Hanging over the bow, he passed the noose over

the head of the snake, and hauled it taut, and then

made the end he held fast to the boat. Louis lifted

his implement from the neck of the snake, and he

squirmed and wriggled as though he "meant business."

Achang leaped to the shore, and seizing the

serpent by the tail, tossed him into the boat. He

struck on one of the cushions, and the cord prevented

him from going any farther.

Scott and Morris had just reached the fore cabin at

this moment, and they started back as though they

had been bitten by the snake. His head, tail, and

belly were bright red, with white stripes upon a dark

ground along his back and sides. No one but Achang

had ever seen such a serpent, even in a museum. His

snakeship was disposed to make himself comfortable

on the cushion, and the Bornean loosed the cord

around his neck.

"I saw a small snake, not more than two feet long,

swimming near the shore of Lake Cobbosseecontee, in

Maine, that had nearly all the colors of the rainbow

in his skin," said Morris. "I tried to knock him

over with my fishing-rod, and catch him; but I

failed. I told the people where we boarded about

him, but no one had ever seen a snake like him."[43]

"There are plenty of such snakes in South America,

some that are not poisonous, which the native

women tame and wear as necklaces," added Louis.

"Well, what are you going to do with him?"

asked Captain Scott. "I think you had better kill

him, and throw him into the river, pretty as he is.

He isn't a very desirable fellow to have as a companion

on board."

"What is the use of killing him? He would only

be food for the crocodiles," protested Louis.

"Do what you like with him, Louis," added the

captain.

"I certainly will not have him killed. If Achang

never saw but one of the kind, there cannot be a

great many of them in this part of the island. Put

him ashore, Achang," said the humane young gentleman.

The Bornean complied with this request; and the

handsome snake skurried off in the woods, none the

worse for his adventure. But the others were not

quite satisfied with the policy of the young millionaire.

They wanted to shoot whatever they could

see in the nature of game, including monkeys, and

he was opposed to this destructive action. Of course

they could kill whatever they pleased, but the moral

influence of the real leader prevailed over them.

"Steam enough!" shouted Felipe from the engine.

"Take the wheel, Clingman, back her out and go

ahead," said the captain; and in a few moments they

were steaming down the river.[44]

"I suppose you haven't any tenderness for crocodiles,

have you, Louis?" inquired Scott, with a smile.

"You seem to believe that I am as chicken-hearted

as a girl; but I believe in killing all harmful animals,

including poisonous snakes; but I do not like

to see these innocent monkeys shot down for the fun

of it," replied Louis. "You can kill them if you

choose, but I will not."

"The rest of us will not, if you are opposed to it,"

added Scott.

"Crocodile on the port hand!" exclaimed Clingman.

"He is swimming across the river, about

three boats' lengths from us."

"Stop her!" said the captain.

"I shot the last one, and I will not fire at this

one," added Louis, who was not disposed to monopolize

the fun.

"All right; then I will be number two, Morris

three, Flix four, and Achang five; and if you are all

satisfied, we will fire in this order hereafter," continued

Scott, as he took aim at the saurian.

He missed the eye of the reptile, and the bullet

from the rifle glanced off and dropped into the

water.

"How many shots is a fellow to have before he

loses his chance?" asked the captain, as he aimed

again.

"I suggest three," said Louis. "Those in favor of

three say ay."

They all voted "ay," and Scott fired twice more.[45]

"Your turn, Morris;" and he appeared to be very

much chagrined at his ill luck. "I could hardly see

the eye of the varmint."

Morris fired his three shots with no better success.

Felix took a different position from the others, placing

himself on the stem. He fired, and the saurian

still kept on his course. He did better the second

time; and the reptile floundered for a moment, and

then turned over dead. The boat was run up alongside,

and Achang was required to bring out his parong

latok, with which he decapitated the game at a

single blow this time; but the creature was only nine

feet long.

Pitts called the cabin party to breakfast at this

time. The Blanchita went ahead again, and the

repeating rifles were left on the cushions. At

Louis's suggestion the captain gave the four men off

duty permission to use the arms on crocodiles, but

not on monkeys.

Ham and eggs, with hot biscuit and coffee, was the

bill of fare; and the young men had sharpened their

appetites in the sports of the morning. Before they

were half done they heard the crack of a rifle. They

listened for the second shot, but none followed it.

"Who fired that shot, Pitts?" asked the captain,

as the steward brought in another plate of biscuit.

"Clinch, sir," replied the man. "He knocked the

crocodile over at the first shot, sir."

"Then he is a better shot than I am," said Scott,

laughing.[46]

"Or any of the rest of us who had their turns,"

added Felix. "Louis is the only fellow that brings

'em down the first time trying."

"The rest of you would have done better if the

sun had not reflected on the water, and shaken your

aim," said Louis.

Before the meal was finished, another shot was

heard, followed by two more. When the party went

forward they found that the little steamer had gone

around a bend so that the forest shaded the surface

of the water. Wales had fired the last three times

at a crocodile still in sight; but he declared that he

could not hit the side of a barn twenty feet from him,

and did not care to fire again. The men went to

breakfast, and the cabin party picked up the rifles.

It was Achang's turn; and he missed twice, but killed

the game at the third shot.

"I can see four more of them. We seem to have

come to a nest of them, and the family are out for

a morning airing," said Louis, as he picked up his

rifle, while Felix was filling the other chambers with

cartridges. "They have all started to go across the

river."

"That must be the father of the family at the

head of the procession," added the captain. "It is

your turn now, Louis."

"Go ahead a little, Pitts," said the next one in

turn; for the cook had taken the wheel while Clingman

went to his morning meal. "I can't see his eye

yet."[47]

"That will do; stop her. I can see his eye now,

and there is no reflection on the water."

As soon as the boat lost her headway, Louis fired.

The saurian leaped nearly out of the water, and came

down wrong side up. There were three dead reptiles

lying on the water. It was the captain's next

shot, and when he placed the yacht in a position to

suit him he fired. The crocodile lifted his head out

of the water, and did not move again.

"Bravo, Captain!" cried Louis. "You did not

have a fair chance last time, and you have redeemed