The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Flying Girl

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Flying Girl

Author: L. Frank Baum

Illustrator: Josef Pierre Nuyttens

Release date: October 28, 2016 [eBook #53386]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mary Glenn Krause, Chris Curnow, ellinora and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images

made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FLYING GIRL ***

- Obvious typos and punctuation errors corrected, otherwise, variations in spelling

retained.

The Flying Girl

“Orissa—The Flying Girl.”

Aunt Jane’s Nieces, Aunt Jane’s Nieces Abroad, Aunt Jane’s Nieces at

Millville, Aunt Jane’s Nieces at Work, Aunt Jane’s Nieces

in Society, Aunt Jane’s Nieces and Uncle John

CONTENTS

| Chapter | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Orissa | 13 |

| II | A Disciple of Aviation | 20 |

| III | The Kane Aircraft | 32 |

| IV | Mr. Burthon is Confidential | 38 |

| V | Between Man and Man—and a Girl | 47 |

| VI | A Bucking Biplane | 55 |

| VII | Something Wrong | 62 |

| VIII | Mr. Burthon’s Proposition | 71 |

| IX | The Other Fellow | 78 |

| X | A Fresh Start | 83 |

| XI | Orissa Resigns | 89 |

| XII | The Spying of Tot Tyler | 96 |

| XIII | Sybil is Critical | 105 |

| XIV | The Flying Fever | 113 |

| XV | A Final Test | 122 |

| XVI | The Opening Gun | 132 |

| XVII | A Curious Accident | 139 |

| XVIII | The One to Blame | 144 |

| XIX | Planning the Campaign | 155 |

| XX | Uncle and Niece | 164 |

| XXI | Mr. H. Chesterton Radley-Todd | 174 |

| XXII | The Flying Girl | 184 |

| XXIII | A Battle in the Air | 192 |

| XXIV | The Criminal | 202 |

| XXV | The Real Heroine | 215 |

| XXVI | Of Course | 222 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| “Orissa—The Flying Girl” | Frontispiece |

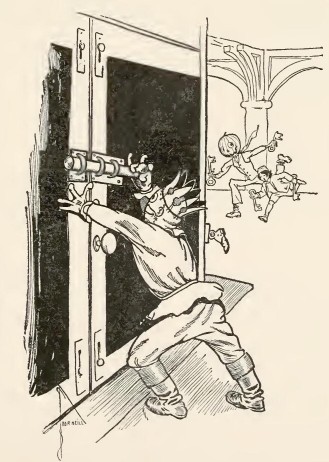

| Orissa stood with hands clasped | 64 |

| “It—interests me” | 124 |

| The rescue | 197 |

11

FOREWORD

The author wishes to acknowledge her indebtedness

to Mr. Glenn H. Curtiss and Mr. Wilbur

Wright for courtesies extended during the preparation

of this manuscript. These skillful and

clever aviators, pioneers to whom the Art of Flying

owes a colossal debt, do not laugh at any suggestion

concerning the future of the aëroplane,

for they recognize the fact that the discoveries

and inventions of the next year may surpass all

that have gone before. The world is agog with

wonder at what has been accomplished; even now

it is anticipating the time when vehicles of the

air will be more numerous than are automobiles

to-day.

The American youth has been no more interested

in the development of the science of aviation

than the American girl; she is in evidence at every

meet where aëroplanes congregate, and already

recognizes her competence to operate successfully

any aircraft that a man can manage. So the story

of Orissa Kane’s feats has little exaggeration except

in actual accomplishment, and it is possible

12her ventures may be emulated even before this

book is out of press. There are twenty women

aviators in Europe; in America are thousands of

girls ambitious to become aviators.

An apology may be due those gentlemen who

performed so many brilliant feats at the 1911 meet

at Dominguez, for having thrust them somewhat

into the shade to allow the story to exalt its heroine;

but they will understand the exigencies that

required this seeming discourtesy and will, the

author is sure, generously pardon her.

CHAPTER I

ORISSA

“May I go now, Mr. Burthon?” asked Orissa.

He looked up from his desk, stared a moment

and nodded. It is doubtful if he saw the girl, for

his eyes had an introspective expression.

Orissa went to a cabinet wardrobe and took

down her coat and hat. Turning around to put

them on she moved a chair, which squeaked on the

polished floor. The sound made Mr. Burthon shudder,

and aroused him as her speech had not done.

“Why, Miss Kane!” he exclaimed, regarding

her with surprise, “it is only four o’clock.”

“I know, sir,” said Orissa uneasily, “but the

mail is ready and all the deeds and transfers have

been made out for you to sign. I—I wanted an

extra hour, to-night, so I worked during lunch

time.”

“Oh; very well,” he said, stiffly. “But I do not

approve this irregularity, Miss Kane, and you

may as well understand it. I engage your services

14by the week, and expect you to keep regular

hours.”

“I won’t go, then,” she replied, turning to hang

up her coat.

“Yes, you will. For this afternoon I excuse

you,” he said, turning again to his papers.

Orissa did not wish to offend her employer. Indeed,

she could not afford to. This was her first

position, and because she was young and girlish in

appearance she had found it difficult to secure a

place. Perhaps it was because she had applied to

Mr. Burthon during one of his fits of abstraction

that she obtained the position at all; but she was

competent to do her work and performed it so

much better than any “secretary” the real estate

agent had before had that he would have been

as loth to lose her as she was to be dismissed.

But Orissa did not know that, and hesitated what

to do.

“Run along, Miss Kane,” said her employer,

impatiently; “I insist upon it—for to-night.”

So, being very anxious to get home early, the

girl accepted the permission and left the office,

feeling however a little guilty for having abridged

her time there.

She had a long ride before her. Leaving the

office at four o’clock meant reaching home forty

minutes later; so she hurried across the street

15and boarded a car marked “Beverly.” Los Angeles

is a big city, because it is spread from the

Pacific Ocean to the mountains—an extreme distance

of more than thirty miles. Yet it is of larger

extent than that would indicate, as country villages

for many miles in every direction are really

suburbs of the metropolis of Southern California

and the inhabitants ride daily into the city for

business or shopping.

It was toward one of these outlying districts

that Orissa Kane was now bound. They have

rapid transit in the Southwest, and the car,

headed toward the north but ultimately destined

to reach the sea by way of several villages, fairly

flew along the tracks. It was August and a glaring

sun held possession of a cloudless sky; but the

ocean breeze, which always arrives punctually the

middle of the afternoon, rendered the air balmy

and invigorating.

It was seldom that this young girl appeared

anywhere in public without attracting the attention

of any who chanced to glance into her sweet

face. Its contour was almost perfect and the

coloring exquisite. In addition she had a slender

form which she carried with exceeding grace and

a modest, winning demeanor that was more demure

and unconscious than shy.

Such a charming personality should have been

16clothed in handsome raiment; but, alas, poor Orissa’s

gown was the simplest of cheap lawns, and

of the ready-made variety the department stores

sell in their basements. It was not unbecoming,

nor was the coarse straw hat with its yard of

cotton-back ribbon; yet the case was stated to-day

very succinctly by a middle-aged gentleman

who sat with his wife in the car seat just behind

Orissa:

“If that girl was our daughter,” said he, “I’d

dress her nicely if it took half my income to do

it. Great Cæsar! hasn’t she anyone to love her,

or care for her? She seems to me like a beautiful

piece of bric-a-brac; something to set on a pedestal

and deck with jewels and laces, for all to

admire.”

“Pshaw!” returned the lady; “a girl like that

will be admired, whatever she wears.”

Orissa had plenty of love, bestowed by those

nearest and dearest to her, but circumstances had

reduced the family fortunes to a minimum and the

girl was herself to blame for a share of the

poverty the Kanes now endured.

The car let her off at a wayside station between

two villages. It was in a depression that might

properly be termed a valley, though of small extent,

and as the car rushed on and left her

standing beside a group of tall palms it at first

17appeared there were no houses at all in the

neighborhood.

But that was not so; a well defined path led

into a thicket of evergreens and then wound

through a large orange orchard. Beyond this was

a vine covered bungalow of the type so universal

in California; artistic to view but quite inexpensive

in construction.

High hedges of privet surrounded the place,

but above this, in the space back of the house, rose

the canvas covered top of a huge shed—something

so unusual and inappropriate in a place of

this character that it would have caused a

stranger to pause and gape with astonishment.

Orissa, however, merely glanced at the tent-like

structure as she hurried along the path. She

turned in at the open door of the bungalow, tossed

hat and jacket into a chair and then went to where

a sweet-faced woman sat in a morris chair knitting.

In a moment you would guess she was Orissa’s

mother, for although the features were worn

and thin there was a striking resemblance between

them and those of the fresh young girl stooping

to kiss her. Mrs. Kane’s eyes were the same turquoise

blue as her daughter’s; but, although

bright and wide open they lacked any expression,

for they saw nothing at all in our big, beautiful

world.

18“Aren’t you early, dear?” she asked.

“A whole hour,” said Orissa. “But I promised

Steve I’d try to get home at this time, for

he wants me to help him. Can I do anything for

you first, mamma?”

“No,” was the reply; “I am quite comfortable.

Run along, if Steve wants you.” Then she added,

in a playful tone: “Will there be any supper

to-night?”

“Oh, yes, indeed! I’ll break away in good season,

never fear. Last night I got into the crush

of the ‘rush hour,’ and the car was detained, so

both Steve and I forgot all about supper. I’ll

run and change my dress now.”

“I’m afraid the boy is working too hard,” said

Mrs. Kane, sighing. “The days are not half long

enough for him, and he keeps in his workshop, or

hangar, or whatever you call it, half the night.”

“True,” returned Orissa, with a laugh; “but it

is not work for Steve, you know; it’s play. He’s

like a child with a new toy.”

“I hope it will not prove a toy, in the end,” remarked

Mrs. Kane, gravely. “So much depends

upon his success.”

“Don’t worry, dear,” said the girl, brightly.

“Steve is making our fortune, I’m sure.”

But as she discarded the lawn for a dark gingham

in her little chamber, Orissa’s face was more

19serious than her words and she wondered—as

she had wondered hundreds of times—whether

her brother’s great venture would bring them

ruin or fortune.

20

CHAPTER II

A DISCIPLE OF AVIATION

The Kanes had come to California some three

years previous because of Mr. Kane’s impaired

health. He had been the manager of an important

manufacturing company in the East, on a

large salary for many years, and his family had

lived royally and his children been given the best

education that money could procure. Orissa attended

a famous girls’ school and Stephen went to

college. But suddenly the father’s health broke

and his physicians offered no hope for his life

unless he at once migrated to a sunny clime where

he might be always in the open air. He came to

California and invested all his savings—not a

great deal—in the orange ranch. Three months

later he died, leaving his blind wife and two children

without any financial resources except what

might be gleaned from the ranch. Fortunately

the boy, Stephen, had just finished his engineering

course at Cornell and was equipped—theoretically,

at least—to begin a career with one of the

best paying professions known to modern times.

21Mechanical to his finger tips, Stephen Kane had

eagerly absorbed every bit of information placed

before him and had been graduated so well that

a fine position was offered him in New York, with

opportunity for rapid advancement.

Mr. Kane’s death prevented the young man

from accepting this desirable offer. He was

obliged to go to Los Angeles to care for his mother

and sister. It was a difficult situation for an inexperienced

boy to face, but he attacked the problem

with the same manly courage that had enabled

him to conquer Euclid and Calculus at school, and

in the end arranged his father’s affairs fairly well.

The oranges from the ranch would give them

a net income of about two thousand dollars a year,

which was far from meaning poverty, although

much less than the family expenditures had previously

been. There were other fruits on the

place, an ample vegetable garden and a flock of

chickens, so the Kanes believed they would live

very comfortably on their income. In addition to

this, Steve could earn a salary as a mechanical

engineer, or at least he believed he could.

He found, however, after many unsuccessful

attempts, that his professional field was amply

covered by experienced men, and as a temporary

makeshift he was finally driven to accept a position

in an automobile repair shop.

22“It’s an awful comedown, Ris,” he said to

Orissa, his confidant, “but I can’t afford to loaf

any longer, you know, and the pay is almost as

much as a young engineer gets to start with. So

I’ll tackle it and keep my eye open for something

better.”

While Stephen was employed in this repair

shop a famous aviator named Willard came to

town with his aëroplane and met with an accident

that badly disabled his machine. Although aviators

have marked Southern California as their

chosen field from the beginning, because one may

fly there all winter, there was not a place in the

city where a specialty was made of repairing airships.

Naturally Mr. Willard sought an automobile

repair shop as the one place most liable to

supply his needs.

The manager shook his head.

“We know nothing about biplanes,” he

confessed.

“Pardon me, sir,” said Stephen Kane, who was

present, “I know something about airships, and

I am sure I can repair Mr. Willard’s, if you will

take the job.”

The aviator turned to him gratefully.

“Thank you,” he said; “I’ll put my machine

in your hands. What experience have you had

with biplanes of this type?”

23“None at all,” was the answer; “but I am sure

you will not find an experienced airship man in

this city. I’ve studied the devices, though, ever

since Montgomery made his first flights, and as we

have all the requisite tools and machinery here

I am sure, with your assistance and direction, I

can readily put your machine into perfect

condition.”

He did, performing the work excellently. Before

long another biplane needed repairs, and

Stephen was recommended by Mr. Willard.

Later a Curtiss machine came under Steve’s

hands, and then an Antoinette monoplane. The

manager raised the young fellow’s salary, proud

that he had a man competent to repair these new-fangled

inventions which were creating such a

stir throughout the country.

Stephen Kane might have continued to follow

the calling of an expert aëroplane doctor with

marked success, had he been an ordinary young

mechanic. But the air castles he had built at college

were not all dissipated, as yet, and aside from

possessing decided talent as a workman Steve had

an inventive genius that promised great things

for his future. By the time he had taken a half

dozen different aëroplanes apart and repaired

them he had a thorough knowledge of their construction

and requirements, and the best of them

24seemed to him wholly inadequate for the purpose

for which they were planned.

“The fact is, Ris,” he said to Orissa one evening,

after he had been poring over a book on air

currents, “the airships of to-day are all experimental,

and chock full of mistakes. No two are

anywhere near alike, and each man thinks he has

the only correct mechanism.”

“But they fly,” answered the girl, who was

keenly interested in the subject of aviation and

had twice been down to the shop to examine the

aëroplanes Steve was repairing.

“So they do; they fly, after a fashion,” admitted

the young man, “which fully proves the

thing can be accomplished. But present machines

are all too complicated, and the planes seem to

have been shaped by guesswork, rather than common

sense. They fuss with motors and propellers

and ignore the sustaining mechanism, which

is the most vital principle of all. Some day we

shall see the sky full of successful aviators, and

flying will be as common as automobiling now is;

but when that time comes we shall laugh at the

crude devices they brag of to-day.”

“That may be true,” returned the girl, thoughtfully;

“but isn’t it true of every great invention,

that the first models are imperfect?”

“Quite true,” said he. “I can make a better

25biplane than any I have seen, but I admit that had

I not had the advantage of seeing any I might

have blundered as all the rest seem to have done.”

“Why don’t you make one, Steve?” asked

Orissa impulsively. “If aviation is going to become

general the man who builds the best aëroplane

will make his fortune.”

Steve flushed and rose to tramp up and down

the room before he answered. Then he stopped

before his sister and said in low, intense accents:

“I long to make one, Orissa! The idea has

taken possession of my thoughts until it has almost

driven me crazy. I can make a machine that

will fly better and be more safe and practical than

either the Wright or Curtiss machines. But the

thing is impossible. I—I haven’t the money.”

Orissa sat staring at the rug for a long time.

Finally she asked:

“How much money would it take, Steve?”

He hesitated.

“I don’t know. I’ve never figured it out.

What’s the use?”

“There is use in everything,” declared his sister,

calmly. “Get to work and figure. Find out

how much you need, and then we’ll see if we can

manage it.”

He gazed at her as if bewildered. Then he

turned and left the room without a word.

26A few evenings later he handed her an estimate.

“I think it could be done for three thousand dollars,”

he remarked. “Which means, of course,

it can’t be done at all.”

Orissa took the paper without replying and pondered

over it for several days. She was only

seventeen, but had inherited her father’s clear,

business-grasping mind, and would have been an

essentially practical girl had not her youth and

inexperience lent her some illusions that time

would dissipate.

Stephen posed as the “head of the family;”

but Orissa really directed its finances, poor Mrs.

Kane being so helpless that her children never

depended upon her for counsel but on the contrary

kept all business matters from her, lest she worry

over them. The one maid employed in the bungalow

served Mrs. Kane almost exclusively, while

Orissa always had devoted much time to her

mother, who had been stricken blind at the time of

her daughter’s birth.

One evening, when brother and sister were in

the garden together, the girl said:

“I believe I have discovered a plan that will

permit you to build your airship. What is it to

be, Steve; a biplane or a monoplane?”

“Let me hear your plan,” was the eager reply.

“Well, I’ve been to see Mr. Wentworth, and he

27will advance us fifteen hundred on our orange

crop, by discounting the price ten per cent. He

came and looked at the trees and said they were

safe to pay us at least twenty-three hundred dollars

next February.”

“But—Orissa!—how could we live, with our

income cut down that way—to a mere seven or

eight hundred dollars?”

“I’m going to work,” she said quietly. “I’m

tired of doing nothing but dig around the garden

and cook. Mamma doesn’t need me, at least during

the day, so I’m going into business.”

Steve smiled.

“You work, Orissa? What on earth could you

do?”

“I’ll find something to do. And my salary,

added to yours, will make up for the loss of the

orange money. We must economize, of course;

but when we’ve such a big deal on hand—one

that will make our fortune—we can put up with a

few temporary discomforts.”

“But fifteen hundred won’t build the thing, that

is certain,” he said, with a sigh. “I’ve got to

construct an entirely new motor—engine and all—and

some original propellers and elevators, and

the patterns and castings for these will be rather

expensive.”

“Well, by the time the fifteen hundred are

28gone,” she replied, “you will know exactly how

much more money is needed, and we will mortgage

the place for that amount.”

“Rubbish!” cried Stephen, impatiently. “I

won’t listen an instant to such a wild plan. Suppose

I fail?”

“Oh, if you’re going to fail we won’t undertake

it,” said his sister. “You claimed you could

make a better airship than the Curtiss or the

Wright—either one of which is worth a fortune—and

I believed you. If you were only joking,

Steve, we won’t talk of it any more.”

“I wasn’t joking; or bragging, either; you

know that, Orissa. I’m pretty sure of my idea;

but it’s untried. I’ve bought all the books on

aviation I can find and I’ve been reading of Professor

Montgomery’s discovery of the laws of

air currents and his theories concerning them.

They’re only primers, dear, for the science of

aviation is as yet unwritten. That is why I cannot

speak with perfect assurance; but the more I look

into the thing the more positive I am that I’ve

hit upon the right idea of aërial navigation.”

“What is your idea?” she asked.

“To simplify the construction of the craft. The

present devices are all too complicated and keep

the aviator too busy while he’s in the air.”

“In other words, he’s all up in the air while

he’s up in the air,” she remarked.

29“Precisely. Most of his time is required to

maintain a lateral balance, so as not to tip over or

lose control. I’m to have a simpler construction,

an automatic balance, and a plane only large

enough to support the machinery and the aviator.”

“If you can manage that,” said Orissa, “we’re

not taking any chances.”

He sat with furrowed brow, thinking deeply.

Finally he said in a decisive way:

“Nothing is certain until it is accomplished. I

won’t take the risk of making you and mother

paupers. Please don’t speak of the thing again,

Ris.”

Orissa didn’t; but Steve did, about a month

later. A great aviation meet had been arranged

at Dominguez Field, near Los Angeles and only

a few miles from their own home. The event,

which was destined to be an epoch in the history of

aviation, brought many famous aviators to the

city with their machines, among them a Frenchman

named Paulhan, with whom Stephen soon became

acquainted. An examination of Paulhan’s

machine, a Farman of the latest type, which had

already performed marvels, served to convince

the boy that his own ideas were not only practical

but destined soon to be discovered and applied by

someone else if he himself failed to take advantage

of the time and opportunity to utilize them.

30With that argument to calm any misgivings that

he might perhaps fail, coupled with an eagerness

to build his invention that drove him to forsake

caution, Steve went to Orissa one day and said:

“All right, dear; I’m going to undertake the

thing. Can you still get Mr. Wentworth to advance

the money?”

“I think so,” she replied.

“Then get it, and I’ll start work at once. The

drawings are already complete,” and he showed

them to her, neatly traced in comprehensive detail.

Most girls would have been bewildered by the

technicalities and passed the drawings with a

glance; but Orissa understood how important to

them all this venture was destined to be, so she

sat down and studied the designs minutely, making

her brother explain anything she found the

least puzzling. By this time the girl had made

herself familiar with the latest modern improvements

in aëroplanes and had personally examined

several of the best devices, so she was able to

catch the true value of Stephen’s idea and immediately

became as enthusiastic as he was.

The money was raised and placed by Stephen

in a bank where he could draw upon it as he

needed it. Mrs. Kane concurred mildly in the

plans when they were explained to her, being accustomed

to lean upon Orissa and Stephen and to

31accept their judgment without protest. Aviation

was all Greek to the poor woman and she did not

bother her head trying to understand why people

wanted to fly, or how they might accomplish their

desire.

32

CHAPTER III

THE KANE AIRCRAFT

Stephen set up his workshop at home, devoting

his evenings to the new aëroplane. Progress was

necessarily slow, as four or five hours out of each

twenty-four were all he could devote to his

enterprise.

The boy was still employed in this manner when

the Aviation Meet was held at Dominguez Field

and Paulhan accomplished the wonderful flights

that made him world famous. Of course, Orissa

and Stephen were present and did not miss a

single event. On the grand stand beside them

sat a young fellow Stephen had often met at the

automobile shop, a chauffeur named Arch Hoxsey.

It was the first time Hoxsey had ever seen an aëroplane,

and neither he nor Stephen could guess

that within one year this novice would become the

greatest aviator in all the world. These are days

when, comet-like, a heretofore unknown aviator

appears, accomplishes marvels and disappears,

eclipsed by some new master of the art of flying.

It is the same way with aëroplanes; the leading

33one to-day is within a brief period destined to be

surpassed by a greatly improved machine.

The enthusiasm of the Kanes rose to fever heat

in witnessing this exhibition, at the time the most

remarkable ever held in the annals of aviation.

Afterward they counseled together very seriously

and agreed that it would be better for Steve to

resign his position at the shop and devote his

whole time to his aëroplane, in which he had now

more confidence than ever.

He applied for patents on his various devices

and the complete machine, being fearful that

someone else might adopt his ideas before he could

finish his first aëroplane; yet at the same time he

observed the utmost secrecy as to the work on

which he was engaged and admitted no person except

Orissa to the garden, where he had set up

his hangar and shop.

The girl had been for some time persistently

seeking employment, for now that Steve had

ceased to be a breadwinner it was more important

than ever for her to earn money. By good fortune

she was engaged by Mr. Burthon as his

secretary the very week following her brother’s

retirement.

Steve’s expenses were growing greater, however,

and Orissa began figuring on “ways and

means.” Their life in this retired place was so

34simple that she believed her mother could do without

the maid and questioned her on the subject.

Mrs. Kane declared she preferred to be alone, if

Orissa felt she could prepare the breakfasts and

dinners unaided. Luncheons at home were very

plain affairs and Steve readily agreed to come

into the house at noon and get a bite for himself

and his mother. So the maid was dismissed and

a considerable expense eliminated.

During the summer construction of the airship

progressed more rapidly and, after the motors

were completed and tested and found to be

nearly perfect, Steve began to model the planes

and perfect his automatic balance.

It was hard work sometimes for Orissa to sit in

the office and keep her mind on her work when

she knew her brother was completing or testing

some important detail of the aëroplane, but she

held herself in rigid restraint and succeeded in

giving satisfaction to her employer.

On the August afternoon on which our story

opens Stephen Kane was to begin the final assembling

of the parts of his machine, after which

he could test it in real flight. He needed Orissa’s

assistance to help him handle some of the huge

ribbed planes, and so she had promised to come

home early.

It was not long before she entered the hangar,

35arrayed in her old gingham, which allowed her

to move freely. The two became so interested

that Mrs. Kane almost missed her dinner in spite

of the girl’s promise; but Orissa did manage to

tear herself away from the fascinating task long

enough to prepare the meal and serve it. Steve

came in and tried to eat, for he was at a point

where he could do nothing without his sister’s

help; but neither of them was able to swallow

more than a morsel, and as quickly as possible

hurried back to their work.

Mrs. Kane, although totally blind, knew her

way about the house perfectly and was able to

take care of herself in nearly all ways; so when

bedtime came she abandoned her monotonous

knitting, played a few pieces on the pianoforte—one

of her few amusements—and then calmly retired

for the night. She never worried over the

“children,” believing they were competent to care

for themselves.

It was long past midnight before Steve got to

a point where he could continue without Orissa.

“In about three days more,” he said, as they

washed up and prepared to adjourn to the house,

“I will be able to make my first flight. Shall

we wait till Sunday, Ris, or will you take a day

off?”

“Oh, not Sunday,” she replied. However eager

36her brother might be she had never yet allowed

him to work a moment on a Sunday, and Steve deferred

to her wishes in this regard. “We’re

pretty busy at the office and Mr. Burthon was inclined

to be a little cranky to-day; but I’ll manage

it somehow, just as soon as you are ready.”

“What sort of a fellow is Burthon?” asked her

brother, somewhat curiously.

“Why, he stands well in the business world, I’m

told, and is very successful in handling large tracts

of real estate,” she replied. “Also, he seems a

gentleman by birth and breeding, yet a queerer

man I never met. His chief peculiarity is in being

very absent-minded, but he does other odd

things. Yesterday he refused to sell a piece of

land to a customer because he did not like him,

and he told the man so with rude frankness. One

day I discovered he had cheated another man out

of six hundred dollars. I called his attention to

what I described as a ‘mistake,’ and he said he

robbed the man on purpose, because he had been

snobbish and overbearing. He gave the six hundred

dollars to a poor woman to build her a house

with, saying to me that he had once committed a

serious crime for which this was in part penance,

and soon after he platted a lot of swamp land

down near San Pedro and advertised it as ‘desirable

residence property.’ Really, Steve, I can’t

quite make out Mr. Burthon.”

37“He seems to have good and bad points, from

what you say,” observed her brother, “and I

judge the two qualities are about evenly mixed.

Is he nice to you, Ris?”

“He is always polite and respectful, but most

of the time he doesn’t know I’m in existence.

When he gets one of his absorbed fits his eyes

look right through me, as if I wasn’t there.”

“Perhaps he is thinking out some big schemes.

Is he a rich man?”

“He is said to be quite wealthy. But he is an

old bachelor, and the girl across the hall says he

lives at a club, goes to the theater every night and

drinks more than is good for him. I hardly believe

that last, Steve, for Mr. Burthon doesn’t

look a bit like a drinking man.”

“Perhaps he’s a morphine fiend. That would

make him absent-minded, you know.”

“No; when he’s aroused his head is clear as a

bell and he drives a shrewd bargain. Do you

know, Steve, I’m inclined to think that speech of

his was in earnest, although he laughed harshly

at the time, and that—that—”

“That what?”

“That at some time or other he has committed

some crime that worries him.”

38

CHAPTER IV

MR. BURTHON IS CONFIDENTIAL

Orissa was tired next day and she blundered

several times in copying deeds and attending to

the routine of the private office, where she alone

was closeted with the proprietor. But Mr. Burthon

would not have noticed had she set fire to

the place, so intent was he upon a bundle of papers

he had brought in with him and to which he

devoted his exclusive attention.

The girl left him at his desk when she went to

lunch and found him there, still occupied with the

papers, when she returned. Several people

wanted to see him personally, but he told Orissa

to state he was engaged and could admit no one.

She gave the message to the young man in charge

of the outer office, where several clerks were employed,

and they knew better than to allow anyone

to invade Mr. Burthon’s private sanctum.

At about three o’clock, while she was busy at

her desk, the secretary heard her name spoken

and looked up. From his chair Mr. Burthon was

39eyeing her observantly. His gaze was clear and

intelligent; the abstracted mood had passed.

“Come here, please, Miss Kane,” he said.

She brought her writing pad and sat down beside

his desk, as she did when he dictated his letters;

but he shook his head.

“We’ll not mind the mail to-day,” he said.

“I want to talk with you; to advise with you.

Queerly enough, Miss Kane, there isn’t a soul

on earth in whom I can confide when occasion

arises. In other words, I haven’t an intimate

friend I can trust, or one who is sincerely interested

in me.”

That embarrassed Orissa a little. Since she

had been working at the office this was the first

time he had addressed a remark to her not connected

with the business. Indeed, the man was

now regarding her much as he would a curiosity,

as if he had just discovered her. She was amazed

to hear him speak so confidentially and made no

reply because she had nothing to say.

After a pause he continued:

“You haven’t much business experience, my

child, but you have a keen intellect and decided

opinions.” Orissa wondered how he knew that.

“Therefore I am going to ask your advice in a

matter where business is blended with sentiment.

Will you be good enough to give me your candid

opinion?”

40“If you wish me to, sir,” she said, after some

hesitation.

“Thank you, Miss Kane. The case is this:

With four others I purchased some time ago a

gold mine in Arizona known as the ‘Queen of

Hearts.’ It cost me about all I am worth—some

two hundred thousand dollars.”

Orissa gasped. It seemed an enormous sum.

But he continued, speaking calmly and clearly:

“I thought at the time the mine was surely

worth a million. I went to see it and found the

ore exceedingly rich. The others, who purchased

the Queen of Hearts with me, were equally deceived,

for just recently we have discovered that

the rich vein was either very narrow or was placed

there by those we purchased from, with the intention

of defrauding us. In either case, please understand

that the mine is not worth a cotton hat.

We are a stock company, and our stock is listed

on the exchange and commands a high premium,

for no one except the owners knows the truth

about it. The general idea is that the mine is

still producing largely—and it is—for, to protect

ourselves until we can unload it on to others, we

have secretly purchased rich ore elsewhere,

dumped it into the mine, and then taken it out

again.”

He paused, drumming absently on the desk with

his fingers, and Orissa asked:

41“What is the object of that deception, sir?”

“To maintain the public delusion until we can

sell out. And now I come to the point of my story,

Miss Kane. Gold mines, even as rich as the Queen

of Hearts is reputed to be, are not easy to sell. I

have exhausted all my resources in keeping up

this deception and the time has come when I must

sell or become bankrupt. The other stockholders

have smaller interests and are wealthier men, but

each one is striving hard to secure a customer. I

have found one.”

He looked up and smiled at her; then he

frowned.

“The man is my brother-in-law,” he added.

Orissa was getting nervous, but waited for him

to continue.

“This brother-in-law is a man I detest. He

married my only sister and did not treat her well.

He is a notorious gambler and confidence man,

although perhaps he would not admit that is his

profession. At all events he had the assurance to

sneer at me and abuse my sister, and I was powerless

at the time to interfere. Fortunately the

poor woman died several years ago. Since then

I have not seen much of Cumberford, for he lives

in the East. He came out here last month on

some small business matter and has gone crazy

over the Queen of Hearts mine. He hunted me up

42and asked if I’d sell part of my stock. I told him

I would sell all or none. So he has been getting

his money together and has raised two hundred

and fifty thousand dollars—the sum I demanded.”

Orissa was looking at him wonderingly. The

story seemed incredible. Perhaps Mr. Burthon

saw the dismay and reproach in her eyes, for he

asked:

“What do you think of this deal, Miss Kane?

Am I not fortunate?”

“But—would you really sell a worthless property

to this man—your own brother-in-law—and—and

steal a fortune from him?” she inquired.

The man flushed and shifted uneasily in his

seat.

“He abused my sister,” he said, as if defending

himself.

“The property is worthless,” she persisted.

“He can hustle around and sell it again, as I

am doing.”

“Suppose he fails? Suppose he refuses to do

such a wicked thing?”

Mr. Burthon stared at her a moment. Then

he laughed harshly.

“Cumberford would delight in such a ‘wicked’

game,” he replied. “And, if he failed to sell,

the scoundrel would be ruined, for I believe this

two hundred and fifty thousand is about all he’s

worth.”

43“It’s dreadful!” exclaimed the girl, really

shocked.

“It is done every day in a business way,” he

rejoined.

“Then why did you ask my advice?” demanded

the girl, quickly. Before answering he waited to

drum on the desk with his fingers again.

“Because,” said he, speaking slowly, “I dislike

this man so passionately that I have wondered if

the hatred blinds my judgment. He may be dangerous,

too, yet I think he is too much of a fool to

be able to injure me in retaliation. I don’t know

him very well. I’ve not seen him before for

years.” He paused, taking note of the horror

spreading over the girl’s face. Then he smiled

and added in a gentler voice: “Perhaps my chief

reason, however, for seeking your advice is that

I find I have still a conscience. Yes, yes; a troublesome

conscience. I have been suppressing it

for years, yet like Banquo’s ghost it will not down.

My business judgment determines me to unload

this worthless stock and save myself from the loss

of my entire fortune. I must do it. It is like a

man taking unawares a counterfeit coin, and then,

discovering it is spurious, passing it on to some innocent

victim. You might do that yourself, Miss

Kane.”

“I do not believe I would.”

44“Well, most people would, and think it no crime.

In this case I’m merely passing a counterfeit,

that I received innocently, on to another innocent.

If the fact is ever known my business friends will

applaud me. But that obstinate conscience of

mine keeps asking the question: ‘Is it safe?’ It

asserts that I am filled with glee because I am selling

to a man I hate—a man who has indirectly injured

me. I am to get revenge as well as save

my money. Safe? Of course it’s safe. Yet my—er—conscience—the

still small voice—keeps

digging at me to be careful. It doesn’t seem to

like the idea of dealing with Cumberford, and has

been annoying me for several days. So I thought

I would put the case to a young, pure-minded girl

who has a clear head and is honest. I imagined

you would tell me to go ahead. Then I could afford

to laugh at cautious Mr. Conscience.”

“No,” said Orissa, gravely, “the conscience is

right. But you misunderstand its warning. It

doesn’t mean that the act is not safe from a

worldly point of view, but from a moral standpoint.

You could not respect yourself, Mr.

Burthon, if you did this thing.”

He sighed and turned to his papers. Orissa

hesitated. Then, impulsively, she asked:

“You won’t do it, sir; will you?”

“Yes, Miss Kane; I think I shall.”

45His tone had changed. It was now hard and

cold.

“Mr. Cumberford will call here to-morrow

morning at nine, to consummate the deal,” he

continued. “See that we are not disturbed, Miss

Kane.”

“But, sir—”

He turned upon her almost fiercely, but at sight

of her distressed, downcast face a kindlier look

came to his eyes.

“Remember that the alternative would be ruin,”

he said gently. “I would be obliged to give up

my business—these offices—and begin life anew.

You would lose your position, and—”

“Oh, I won’t mind that!” she exclaimed.

“Don’t you care for it, then?”

“Yes; for I need the money I earn. But to do

right will not ruin either of us, sir.”

“Perhaps not; but I’m not going to do right—as

you see it. I shall follow my business

judgment.”

Orissa was indignant.

“I shall save you from yourself, then,” she

cried, standing before him like an accusing angel.

“I warn you now, Mr. Burthon, that when Mr.

Cumberford calls I shall tell him the truth about

your mine, and then he will not buy it.”

He looked at her curiously, reflectively, for a

46long time, as if he beheld for the first time some

rare and admirable thing. The man was not angered.

He seemed not even annoyed by her

threat. But after that period of disconcerting

study he turned again to his desk.

“Thank you, Miss Kane. That is all.”

She went back to her post, trembling nervously

from the excitement of the interview, and tried to

put her mind on her work. Mr. Burthon was

wholly unemotional and seemed to have forgotten

her presence. But, a half hour later, when he

thrust the papers into his pocket, locked his desk

and took his hat to go, he paused beside his secretary,

gazed earnestly into her face a moment and

then abruptly turned away.

“Good night, Miss Kane,” he said, and his voice

seemed to dwell tenderly on her name.

47

CHAPTER V

BETWEEN MAN AND MAN—AND A GIRL

That night Orissa confided the whole story to

Steve. Her brother listened thoughtfully and

then inquired:

“Will you really warn Mr. Cumberford, Ris?”

“I—I ought to,” she faltered.

“Then do,” he returned. “To my notion Burthon

is playing a mean trick on the fellow, and no

good business man would either applaud or respect

him for it. Your employer is shifty, Orissa; I’m

sure of it; if I were you I’d put a stop to his game

no matter what came of it.”

“Very well, Steve; I’ll do it. But I don’t believe

Mr. Burthon means to be a bad man. His

plea about his conscience proves that. But—but—”

“It’s worse for a man to realize he’s doing

wrong, and then do it, than if he were too hardened

to have any conscience at all,” asserted Steve

oracularly.

“And if I let him do this wrong act I would be

as guilty as he,” she added.

48“That’s true, Ris. You’ll lose your job, sure

enough, but there will be another somewhere just

as good.”

So, when Mr. Burthon’s secretary went to the

office next morning she was keyed up to do the

most heroic deed that had ever come to her hand.

Whatever the consequences might be, the girl was

determined to waylay Mr. Cumberford when he

arrived and tell him the truth about the Queen of

Hearts.

But he did not come to the office at nine o’clock.

Neither had Mr. Burthon arrived at that time.

Orissa, her heart beating with trepidation but

strong in resolve, watched the clock nearing the

hour, passing it, and steadily ticking on in the

silence of the office. The outer room was busy

this morning, and in the broker’s absence his secretary

was called upon to perform many minor

tasks; but her mind was more upon the clock than

upon her work.

Ten o’clock came. Eleven. At half past eleven

the door swung open and Mr. Burthon ushered in

a strange gentleman whom Orissa at once decided

was Mr. Cumberford. He was extremely tall and

thin and stooped somewhat as he walked. He had

a long, grizzled mustache, wore gold-rimmed eyeglasses

and carried a gold-headed cane. From

his patent leather shoes to his chamois gloves he

49was as neat and sleek as if about to attend a

reception.

Observing the presence of a young lady the

stranger at once removed his hat, showing his

head to be perfectly bald.

“Sit down, Cumberford,” said Mr. Burthon,

carelessly.

As he obeyed, Orissa, her face flaming red, advanced

to a position before him and exclaimed in

a pleading voice:

“Oh, sir, do not buy Mr. Burthon’s mine, I beg

of you!”

The man stared at her with faded gray eyes

which were enlarged by the lenses of his spectacles.

Mr. Burthon smiled, seemed interested,

and watched the scene with evident amusement.

“Why not, my child?” asked Mr. Cumberford.

“Because it is worthless—absolutely worthless!”

she declared.

He turned to the other man.

“Eh, Burthon?” he muttered, inquiringly.

“Miss Kane believes she is speaking the truth,”

said the broker jauntily.

“Oh, she does. And you, Burthon?”

“I? Why, I’m of the same opinion.”

Mr. Cumberford took out his handkerchief, removed

his glasses and polished the lenses with

a thoughtful air. Orissa was trembling with

nervousness.

50“Don’t buy the Queen of Hearts, sir; it would

ruin you,” she repeated earnestly.

He breathed upon the glasses and wiped them

carefully.

“You interest me,” he remarked. “But, the

fact is, I—er—I’ve bought it.”

“Already!”

“At nine o’clock, according to agreement. Burthon

sent word he’d come to my hotel instead of

meeting me at his office, as first planned.”

“Oh, I see!” cried Orissa, much disappointed.

“He knew I would prevent the crime.”

“Crime, miss?”

“Is it not a crime to rob you of two hundred and

fifty thousand dollars?”

“It would be, of course. I should dislike to lose

so much money.”

“You have lost it!” declared the girl. “That

mine has no gold in it at all—except what has been

bought elsewhere and placed in it to deceive a

purchaser.”

Mr. Cumberford replaced his glasses, adjusting

them carefully upon his nose. Then he stared at

Orissa again.

“You’re an honest young woman,” he said

calmly. “I’m much obliged. You interest me.

But—ahem!—Burthon has my money, you see.”

Mr. Burthon’s expression had changed. He was

51now regarding his brother-in-law with a curious

and puzzled gaze.

“You’re not angry, Cumberford?” he asked.

“No, Burthon.”

“You’re not even annoyed, I take it?” This

with something of a sneer.

“No, Burthon.”

Both Orissa and her employer were amazed.

Looking from one to another, Mr. Cumberford’s

waxen features relaxed into a smile.

“I’ve placed my Queen of Hearts stock in a

safety deposit vault,” he remarked blandly.

“I have deposited your money in my bank,”

retorted Mr. Burthon, triumphantly.

“Excellent!” said the other. “The thing interests

me—indeed it does. You couldn’t purchase

that stock from me at this moment, Burthon, for

twice the sum I paid you.”

“No? And why not?”

“I’ll tell you. I had not intended to refer to

the matter just yet, but this young woman’s exposé

of your attempted trickery induces me to explain

matters. You have always taken me for a

fool, Burthon.”

“I’ve tried to place a proper value on your intellect,

Cumberford.”

“You have little talent in that line, believe me.

Before I came out here I had heard such glowing

52reports of the Queen of Hearts that I stopped off

in Arizona to see the wonderful mine. The manager

was very polite and showed me about, but

somehow I got a notion that all was not square and

aboveboard. I’ve always been interested in

mines; they fascinate me; and if this mine was as

rich as reported I wanted some of the stock. But

I imagined things looked a little queer, so I sent a

confidential agent—fellow named Brewster, who

has been with me for years—to hire out as a miner

and keep his eyes open. He soon discovered the

truth—that the mine was being ‘salted’ or fed with

outside gold ore in precisely the way this girl has

stated.”

He turned to Orissa with a profound bow, then

looked toward Burthon again. “The thing interested

me. I wondered why, and wired my man

to stay on a little longer, till I had time to think

it over. I—er—think very slowly. Very. In a

few days Brewster telegraphed me the startling

intelligence that the mine had actually struck a

new lead, with ore far richer than the first showing,

although that had made the Queen of Hearts

famous. My man had been sent to the telegraph

office with messages from the manager to Mr.

Burthon and the four other stockholders; but poor

Brewster’s memory is bad, and he forgot to send

a telegram to anyone but me. Of course the great

53strike—er—interested me. I instructed Brewster

over the telegraph wire. At a cost of five thousand

dollars we bribed the manager to keep the

valuable strike secret for ten days. He’s an

honest man, and I shall retain him in the office.

The ten days expire to-night. Meantime, I’ve

purchased the stock.”

Mr. Burthon sprang to his feet, white with

anger.

“You scoundrel!” he shouted.

“Don’t get excited, Burthon. This is a mere

business incident, between man and man—and a

girl.” Another bow toward Orissa. “You tried

to rob me, sir, and sneered when you thought you

had succeeded. I haven’t robbed you, for I paid

your price; but I’ve made a very neat investment.

My stock is worth a million at this moment. Interesting,

isn’t it?”

Mr. Burthon recovered himself with an effort

and sat down again.

“Very well,” he said a little thickly. “As you

say, it’s all in the way of business. Good day,

Cumberford.”

The other man arose and faced Orissa, who

stood by wholly bewildered by this unexpected

development.

“Thank you again, my child. Your name?

Orissa Kane. I’ll remember it. You tried to do

me a kindness. Interesting—very!”

54Without another glance at Mr. Burthon he put

on his hat, walked out and closed the door softly

behind him.

Orissa looked up and found the broker’s eyes

regarding her intently.

“I—I’m sorry, sir,” she stammered; “but I

had to do it, to satisfy my conscience. I suppose I

am dismissed?”

“No, indeed, Miss Kane,” he returned in kindly

tones. “An honest secretary is too rare an acquisition

to be dismissed without just cause. Having

told you what I did, I could expect you to act

in no other way.”

“And, after all, sir,” she said, brightening at

the thought, “you did not rob him! Yet you saved

your fortune.”

He made a slight grimace, and then laughed

frankly.

“Had I taken your advice,” he rejoined, “I

should now be worth a million.”

55

CHAPTER VI

A BUCKING BIPLANE

Stephen Kane had scarcely slept a wink for

three nights. When Orissa came home Thursday

evening he met her at the car with the news that

his aëroplane was complete.

“I’ve been adjusting it and testing the working

parts all the afternoon,” he said, his voice

tense with effort to restrain his excitement, “and

I’m ready for the trial whenever you say.”

“All right, Steve,” she replied briskly; “it begins

to be daylight at about half past four, this

time of year; shall we make the trial at that hour

to-morrow morning?”

“I couldn’t wait longer than that,” he admitted,

pressing her arm as they walked along.

“My idea is to take it into old Marston’s

pasture.”

“Isn’t the bull there?” she inquired.

“Not now. Marston has kept the bull shut up

the past few days. And it’s the best place for the

trial, for there’s lots of room.”

56“Let’s take a look at it, Steve!” she said,

hastening her steps.

In the big, canvas covered shed reposed the

aëroplane, its spreading white sails filling the

place almost to the very edges. It was neither a

monoplane nor a biplane, according to accepted

ideas of such machines, but was what Steve called

“a story-and-a-half flyer.”

“That is, I hope it’s a flyer,” he amended,

while Orissa stared with admiring eyes, although

she already knew every stick and stitch by heart.

“Of course it’s a flyer!” she exclaimed. “I

wouldn’t be afraid to mount to the moon in that

airship.”

“All that witches need is a broomstick,” he

said playfully. “But perhaps you’re not that

sort of a witch, little sister.”

“What shall we call it, Steve?” she asked, seriously.

“Of course it’s a biplane, because there

are really two planes, one being above the other;

but it is not in the same class with other biplanes.

We must have a distinctive name for it.”

“I’ve thought of calling it the ‘Kane Aircraft,’”

he answered. “How does that strike

you?”

“It has an original sound,” Orissa said.

“Oh, Steve! couldn’t we try it to-night? It’s

moonlight.”

57He shook his head quickly, smiling at her

enthusiasm.

“I’m afraid not. You’re tired, and have the

dinner to get and the day’s dishes to wash and

put away. As for me, I’m so dead for sleep I can

hardly keep my eyes open. I must rest, so as to

have a clear head for to-morrow’s flight.”

“Shall we say anything to mother about it?”

“Why need we? It would only worry the dear

woman unnecessarily. Whether I succeed or fail

in this trial, it will be time enough to break the

news to her afterward.”

Orissa agreed with this. Mrs. Kane knew the

airship was nearing completion but was not especially

interested in the venture. It seemed wonderful

to her that mankind had at last learned how

to fly, and still more wonderful that her own son

was inventing and building an improved appliance

for this purpose; but so many marvelous things

had happened since she became blind that her mind

was to an extent inured to astonishment and she

had learned to accept with calm complacency anything

she could not comprehend.

Brother and sister at last tore themselves away

from the fascinating creation and returned to

the house, where Steve, thoroughly exhausted, fell

asleep in his chair while Orissa was preparing

dinner. He went to bed almost immediately after

58he had eaten and his sister also retired when her

mother did, which was at an early hour.

But Orissa could not sleep. She lay and

dreamed of the great triumph before them; of the

plaudits of enraptured spectators; of Stephen’s

name on every tongue in the civilized world; and,

not least by any means, of the money that would

come to them. No longer would the Kanes have

to worry over debts and duebills; the good things

of the world would be theirs, all won by her

brother’s cleverness.

If she slept at all before the gray dawn stole

into the sky the girl was not aware of it. By

half past four she had smoking hot coffee ready

for Steve and herself and after hastily drinking

it they rushed to the hangar.

Steve was bright and alert this morning and declared

he had “slept like a log.” He slid the

curtains away from the front of the shed and solemnly

the boy and girl wheeled the big aëroplane

out into the garden. By careful manipulation they

steered it between the trees and away to the fence

of Marston’s pasture, which adjoined their own

premises at the rear. To get it past the fence had

been Steve’s problem, and he had arranged to take

out a section of the fencing big enough to admit his

machine. This was now but a few minutes’ work,

and presently the aëroplane was on the smooth

turf of the pasture.

59They were all alone. There were no near neighbors,

and it was early for any to be astir.

“One of the most important improvements I

have made is my starting device,” said Steve, as

he began a last careful examination of his aircraft.

“All others have a lot of trouble in getting

started. The Wright people erect a tower and

windlass, and nearly every other machine uses a

track.”

“I know,” replied Orissa. “I have seen several

men holding the thing back until the motors got

well started and the propellers were whirling at

full speed.”

“That always struck me as a crude arrangement,”

observed her brother. “Now, in this machine

I start the motor whirling an eccentric of

the same resisting power as the propeller, yet it

doesn’t affect the stability of the aëroplane.

When I’m ready to start I throw in a clutch that

instantly transfers the power from the eccentric

to the propeller—and away I go like a rocket.”

As he spoke he kissed his sister and climbed

to the seat.

“Are you afraid, Steve?” she whispered, her

beautiful face flushed and her eyes bright with

excitement.

“Afraid! Of my own machine? Of course

not.”

60“Don’t go very high, dear.”

“We’ll see. I want to give it a thorough test.

All right, Ris; I’m off!”

The motors whirred, steadily accelerating

speed while the aëroplane trembled as if eager to

dart away. Steve threw in the clutch; the machine

leaped forward and ran on its wheels across

the pasture like a deer, but did not rise.

He managed to stop at the opposite fence and

when Orissa came running up, panting, her

brother sat in his place staring stupidly ahead.

“What’s wrong, Steve?”

He rubbed his head and woke up.

“The forward elevator, I guess. But I’m sure

I had it adjusted properly.”

He got down and examined the rudder, giving

it another upward tilt.

“Now I’ll try again,” he said cheerfully.

They turned the aircraft around and he made

another start. This time Orissa was really terrified,

for the thing acted just like a bucking broncho.

It rose to a height of six feet, dove to the

ground, rose again to plunge its nose into the turf

and performed such absurd, unexpected antics

that Steve had to cling on for dear life. When he

finally managed to bring it to a halt the rudder

was smashed and two ribs of the lower plane

splintered.

61They looked at the invention with dismay, both

silent for a time.

“Of course,” said Steve, struggling to restrain

his disappointment, “we couldn’t expect it to be

perfect at the first trial.”

“No,” agreed Orissa, faintly.

“But it ought to fly, you know.”

“Being a flying machine, it ought to,” she said.

“Can you mend it, Steve?”

“To be sure; but it will take me a little time.

To-morrow morning we will try again.”

With grave faces they wheeled it back into the

garden and the boy replaced the fence. Then

back to the hangar, where Steve put the Kane

Aircraft in its old place and drew the curtains—much

as one does at a funeral.

“I’m sure to discover what’s wrong,” he told

Orissa, regaining courage as they walked toward

the house. “And, if I’ve made a blunder, this is

the time to rectify it. To-morrow it will be sure

to fly. Have faith in me, Ris.”

“I have,” she replied simply. “I’ll go in and

get breakfast now.”

62

CHAPTER VII

SOMETHING WRONG

All that day Orissa was in a state of great depression.

Even Mr. Burthon noticed her woebegone

face and inquired if she were ill. The girl

had staked everything on Steve’s success and until

now had not permitted a doubt to creep into

her mind. But the behavior of the aircraft was

certainly not reassuring and for the first time she

faced the problem of what would happen if it

proved a failure. They would be ruined financially;

the place would have to be sold; worst of

all, her brother’s chagrin and disappointment

might destroy his youthful ambition and leave him

a wreck.

Somehow the girl managed to accomplish her

work that day and at evening, weary and despondent,

returned to her home. When she left

the car her step was slow and dragging until

Steve came running to meet her. His face was

beaming as he exclaimed:

“I’ve found the trouble, Ris! It was all my

stupidity. I put a pin in the front elevator while

63I was working at it, and forgot to take it out

again. No wonder it wouldn’t rise—it just

couldn’t!”

Orissa felt as if a great weight had been lifted

from her shoulders.

“Are you sure it will work now?” she asked

breathlessly.

“It’s bound to work. I’ve planned all right;

that I know; and having built the aircraft to do

certain things it can’t fail to do them. Provided,”

he added, more soberly, “I haven’t overlooked

something else.”

“Are the repairs completed, Steve?”

“All is in apple-pie order for to-morrow morning’s

test.”

It was a dreadfully long evening for them both,

but after going to bed Orissa was so tired and relieved

in spirit that she fell into a deep sleep that

lasted until Steve knocked at her door at early

dawn.

“Saturday morning,” he remarked, as together

they went out to the hangar. “Do you suppose

yesterday being Friday had anything to do with

our hard luck?”

“No; it was only that forgotten pin,” she

declared.

Again they wheeled the aircraft out to Marston’s

pasture, and once more the girl’s heart beat

high with hope and excitement.

64Steve took a final look at every part, although

he had already inspected his work with great care.

Then he sprang into the seat and said:

“All right, little sister. Wish me luck!”

The motor whirred—faster and faster—the

clutch gripped the propeller, and away darted

the aircraft. It rolled half way across the pasture,

then lifted and began mounting into the air.

Orissa stood with her hands clasped over her

bosom, straining her eyes to watch every detail of

the flight.

Straight away soared the aircraft, swift as a

bird, until it was a mere speck in the gray sky.

The girl could not see the turn, for the circle made

was scarcely noticeable at that distance, but suddenly

she was aware that Steve was returning.

The speck became larger, the sails visible. The

young aviator passed over the pasture at a height

of a hundred feet from the ground, circled over

their own garden and then began to descend. As

he did so the aircraft assumed a rocking motion,

side to side, which increased so dangerously that

Orissa screamed without knowing that she did so.

Down came the aëroplane, reaching the earth

on a side tilt that crushed the light planes into

kindling wood and a mass of crumpled canvas.

Steve rolled out, stretched his length upon the

ground, and lay still.

Orissa Stood with Hands Clasped.

65The sun was just beginning to rise over the

orange grove. The deathly silence that succeeded

the wreck of the aircraft was only broken by the

irregular, spasmodic whirr of the motors, which

were still going. Orissa, white and cold, crept in

among the debris and shut down the engines.

Then, slowly and reluctantly, she approached the

motionless form of her brother.

To be alone at such a time and place was dreadful.

A few steps from Steve she halted; then

turned and fled toward the garden in sudden

panic. Away from the horrid scene her courage

and presence of mind speedily returned. She

caught up a bucket of water that stood in the shed

and lugged it back to the pasture.

Was Steve dead? She leaned over him, dreading

to place her hand upon his heart, gazing piteously

into his set, unresponsive face.

Pat—pat—patter!

A rush across the springing turf.

What was it?

Orissa straightened up, yelled like an Indian

and made a run for the fence that did full credit

to her athletic training.

For Marston’s big bull was coming—a huge,

tawny creature with a temper that would shame

tobasco. He swerved as if to follow the fleeing

girl, but then the draggled planes of the aircraft

66defied him and he changed his mind to charge this

new and unknown enemy—perhaps with the same

disposition that Don Quixote attacked the

windmill.

Orissa shrieked again, for the enormous beast

bounded directly over Steve’s prostrate body and

with bowed head and tail straight as a pointer

dog’s rushed at the aëroplane. The sails shivered,

collapsed, rolled in billows like the waves of

the ocean, and amid them the struggling bull went

down, tangled himself in the wires and became a

helpless prisoner.

The girl, who was sobbing hysterically, heard

herself laugh aloud and was inexpressibly

shocked. The bull bellowed with rage but was so

wound around with guy-wires that this was the

extent of his power. Turning her eyes from the

beast to Steve she gave a shout of joy, for her

brother was sitting up and rubbing his leg with

one hand and his head with the other, while he

stared bewildered at the wreck of his aëroplane,

from which the head of the bull protruded.

Orissa ran up, wringing her hands, and asked:

“Are you much hurt, dear?”

“I—I’ve gone crazy!” he answered, despairingly.

“Seems as if the aircraft was transformed

into the mummy of a—a—brute beast! Don’t

laugh, Ris. Wh—what’s wrong with me—with

my eyes? Tell me!”

67She threw herself down upon the grass and

laughed until she cried, Steve’s reproachful

glances having no particle of effect in restraining

her. When at last she could control herself she

sat up and wiped her eyes, saying:

“Forgive me, dear, it’s—it’s so funny! But,”

suddenly grave and anxious, “are you badly hurt?

Is anything—broken?”

“Nothing but my heart,” he replied dolefully.

“Oh; that!” she said, relieved.

“Just look at that mess!” he wailed, pointing

to the aircraft. “What has happened to it?”

“The bull,” she answered. “But don’t be discouraged,

dear; the thing flew beautifully.”

“The bull?”

“No; the aircraft. But as for the bull, I’m

bound to say he did his best. How in the world

shall we get him out of there, Steve?”

“I—I think I’m dazed, Ris,” he murmured,

feeling his head again. “Can’t you help me to—understand?”

So she told him the whole story, Stephen sighing

and shaking his head as he glared at the bull

and the bull glared at him. Afterward the boy

made an effort to rise, and Orissa leaned down

and assisted him. When he got to his feet she held

him until he grew stronger and could stand alone.

“I’m so grateful you were not killed,” his sister

68whispered. “Nothing else matters since you

have so miraculously escaped.”

“Killed?” said Steve; “why, it was only a

tumble, Ris. But the bull is a more serious complication.

I suppose the aircraft was badly damaged,

from what you say, before the bull got it;

but now it’s a hopeless mess.”

“Oh, no,” she returned, encouragingly. “If he

hasn’t smashed the motor we won’t mind the rest

of the damage. Do you think we can untangle

him?”

They approached the animal, who by this time

was fully subdued and whined apologetically to

be released. Steve got his nippers and cut wire

after wire until suddenly the animal staggered to

his feet, gave a terrified bellow and dashed down

the field with a dozen yards of plane cloth wound

around his neck.

“Good riddance!” cried Orissa. “I don’t

think he’ll ever bother us again.”

Steve was examining the wreck. He tested the

motors and found that neither the fall nor the bull

had damaged them in the least. But there was

breakage enough, aside from this, to make him

groan disconsolately.

“The flight was wonderful,” commented his

sister, watching his face anxiously. “Nothing

could work more perfectly than the Kane Aircraft

69did until—until—the final descent. What caused

the rocking, Steve?”

“A fault of the lateral balance. My automatic

device refused to work, and before I knew it I had

lost control.”

She stood gazing thoughtfully down at the

wreck. Her brother had really invented a flying

machine, of that there was no doubt. She had

seen it fly—seen it soar miles through the air—and

knew that a certain degree of success had been

obtained. There was something wrong, to be sure;

there usually is with new inventions; but wrongs

can be righted.

“I’ve succeeded in a lot of things,” her brother

was saying, reflectively. “The engines, the propeller

and elevator are all good, and decided improvements

on the old kinds. The starting device

works beautifully and will soon be applied to

every airship made. Only the automatic balance

failed me, and I believe I know how to remedy

that fault.”

“Do you suppose the machine can be rebuilt?”

she asked.

“Assuredly. And the automatic balance perfected.

The trouble is, Orissa, it will take a lot

more money to do it, and we’ve already spent the

last cent we could raise. It’s hard luck. Here

is a certain fortune within our grasp, if we could

70perfect the thing, and our only stumbling block is

the lack of a few dollars.”

Having reviewed in her mind all the circumstances

of Steve’s successful flight the girl knew

that he spoke truly. Comparing the aircraft with

other machines she had seen and studied at the

aviation meet she believed her brother’s invention

was many strides in advance of them all.

“The question of securing the money is something

we must seriously consider,” she said. “In

some way it will be raised, of course. But just

now our chief problem is how to get this ruin back

to the hangar.”

“That will be my job,” declared Steve, his courage

returning. “There are few very big pieces

left to remove, and by taking things apart I shall

be able to get it all into the shed. The day’s doings

are over, Ris. Get breakfast and then go to

your work. After I’ve stored this rubbish I’ll

take a run into town myself, and look for a job.

The aviation jig is up—for the present, at least.”

“Don’t do anything hurriedly, Steve,” protested

the girl. “Work on the aircraft for a day

or two, just as if we had money to go ahead with.

That will give me time to think. To-night, when

I come home, we will talk of this again.”

71

CHAPTER VIII

MR. BURTHON’S PROPOSITION

Saturday was a busy day at the office. They did

not close early, but rather later than on other

days, and Orissa found plenty of work to occupy

her. But always there remained in her thoughts

the problem of how to obtain money for Steve,

and she racked her brain to find some practical

solution.

Mr. Burthon was in a mellow mood to-day.

Since the sale of his mining stock he had been less

abstracted and moody than before, and during the

afternoon, having just handed Orissa several

deeds of land to copy, he noticed her pale, drawn

face and said:

“You look tired, Miss Kane.”

She gave him one of her sweet, bright smiles in

payment for the kindly tone.

“I am tired,” she returned. “For two mornings

I have been up at four o’clock.”

“Anyone ill at home?” he asked quickly.

“No, sir.”

Suddenly it occurred to her that he might assist

72in unraveling the problem. She turned to him

and said:

“Can you spare me a few minutes, Mr. Burthon?

I—I want to ask your advice.”

He glanced at her curiously and sat down in a

chair facing her.

“Tell me all about it,” he said encouragingly.

“Not long ago it was I asking for advice, and you

were good enough to favor me. Now it is logically

your turn.”

“My brother,” said she, “has invented an

airship.”

He gave a little start of surprise and an eager

look spread over his face. Then he smiled at her

tolerantly.

“All the world has gone crazy over aviation,”