The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Yacht Club; or, The Young Boat-Builder

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Yacht Club; or, The Young Boat-Builder

Author: Oliver Optic

Release date: November 6, 2007 [eBook #23351]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from scans of public domain material produced by

Microsoft for their Live Search Books site.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE YACHT CLUB; OR, THE YOUNG BOAT-BUILDER ***

|  |

Miss Nellie Patterdale and Don John. Frontispiece.

[1]

THE YACHT CLUB SERIES.

THE YACHT CLUB;

OR,

THE YOUNG BOAT-BUILDER.

BY

OLIVER OPTIC,

AUTHOR OF "YOUNG AMERICA ABROAD," "THE ARMY AND NAVY SERIES,"

"THE WOODVILLE STORIES," "THE STARRY FLAG SERIES," "THE

BOAT CLUB STORIES," "THE LAKE SHORE SERIES,"

"THE UPWARD AND ONWARD SERIES,"

ETC., ETC.

WITH THIRTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

NEW YORK:

LEE, SHEPARD AND DILLINGHAM.

[2]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873,

By WILLIAM T. ADAMS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Brown Type-Setting Machine Company.

[3]

TO

MY YOUNG FRIEND

CHARLES H. HASTINGS,

OF NEW YORK,

This Book is Affectionately Dedicated.

[4]

The Yacht Club Series.

1. LITTLE BOBTAIL; or, The Wreck of the Penobscot.

2. THE YACHT CLUB; or, The Young Boat-builder.

3. MONEY-MAKER; or, The Victory of the Basilisk.

4. THE COMING WAVE; or, The Hidden Treasure of High Rock.

5. THE DORCAS CLUB; or, Our Girls Afloat.

[5]

PREFACE.

"The Yacht Club" is the second volume of the Yacht Club

Series, to which it gives a name; and like its predecessor, is an

independent story. The hero has not before appeared, though

some of the characters of "Little Bobtail" take part in the

incidents: but each volume may be read understandingly without

any knowledge of the contents of the other. In this story,

the interest centres in Don John, the Boat-builder, who is certainly

a very enterprising young man, though his achievements

have been more than paralleled in the domain of actual life.

Like the first volume of the series, the incidents of the story

transpire on the waters of the beautiful Penobscot Bay, and on

its shores. They include several yacht races, which must be

more interesting to those who are engaged in the exciting sport

of yachting, than to others. But the principal incidents are distinct

from the aquatic narrative; and those who are not interested

in boats and boating will find that Don John and Nellie

Patterdale do not spend all their time on the water.[6]

The hero is a young man of high aims and noble purposes:

and the writer believes that it is unpardonable to awaken the

interest and sympathy of his readers for any other than high-minded

and well-meaning characters. But he is not faultless;

he makes some grave mistakes, even while he has high aims.

The most important lesson in morals to be derived from his

experience is that it is unwise and dangerous for young people

to conceal their actions from their parents and friends; and that

men and women who seek concealment "choose darkness because

their deeds are evil."

Harrison Square, Boston,

May 22, 1873.

[7]

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Don John of Belfast, and Friends | 11 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| About the Tin Box | 28 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Yacht Club at Turtle Head | 46 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| A Sad Event in the Ramsay Family | 63 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Captain Shivernock | 81 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| [8]Donald gets the Job | 99 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Laying down the Keel. | 117 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The First Regatta. | 135 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Skylark and the Sea Foam. | 153 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Launch of the Maud. | 171 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The White Cross of Denmark. | 189 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Donald answers Questions. | 207 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Moonlight on the Juno. | 226 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Captain Shivernock's Joke. | 244 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| [9]Laud Cavendish takes Care of Himself. | 264 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Saturday Cove. | 283 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Great Race. | 302 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Hasbrook Outrage, and other Matters. | 320 |

[10]

[11]

THE YACHT CLUB;

OR,

THE YOUNG BOAT-BUILDER.

CHAPTER I.

DON JOHN OF BELFAST, AND FRIENDS.

"Why, Don John, how you frightened

me!" exclaimed Miss Nellie Patterdale,

as she sprang up from her reclining position

in a lolling-chair.

It was an intensely warm day near the close

of June, and the young lady had chosen the

coolest and shadiest place she could find on the

piazza of her father's elegant mansion in Belfast.

She was as pretty as she was bright and vivacious,

and was a general favorite among the

pupils of the High School, which she attended.

She was deeply absorbed in the reading of a

story in one of the July magazines, which had[12]

just come from the post-office, when she heard

a step near her. The sound startled her, it

was so near; and, looking up, she discovered

the young man whom she had spoken to close

beside her. He was not Don John of Austria,

but Donald John Ramsay of Belfast, who had

been addressed by his companions simply as

Don, a natural abbreviation of his first name,

until he of Austria happened to be mentioned

in the history recitation in school, when the

whole class looked at Don, and smiled; some of

the girls even giggled, and got a check for it;

but the republican young gentleman became a

titular Spanish hidalgo from that moment.

Though he was the son of a boat-builder, by

trade a ship carpenter, he was a good-looking,

and gentlemanly fellow, and was treated with

kindness and consideration by most of the sons

and daughters of the wealthy men of Belfast,

who attended the High School. It was hardly

a secret that Don John regarded Miss Nellie

with especial admiration, or that, while he was

polite to all the young ladies, he was particularly

so to her. It is a fact, too, that he blushed when

she turned her startled gaze upon him on the[13]

piazza; and it is just as true that Miss Nellie

colored deeply, though it may have been only

the natural consequence of her surprise.

"I beg your pardon, Nellie; I did not mean

to frighten you," replied Donald.

"I don't suppose you did, Don John; but you

startled me just as much as though you had

meant it," added she, with a pleasant smile, so

forgiving that the young man had no fear of the

consequences. "How terribly hot it is! I am

almost melted."

"It is very warm," answered Donald, who,

somehow or other, found it very difficult to carry

on a conversation with Nellie; and his eyes seemed

to him to be twice as serviceable as his tongue.

"It is dreadful warm."

And so they went on repeating the same thing

over and over again, till there was no other known

form of expression for warm weather.

"How in the world did you get to the side of

my chair without my hearing you?" demanded

Nellie, when it was evidently impossible to say

anything more about the heat.

"I came up the front steps, and was walking

around on the piazza to your father's library. I[14]

didn't see you till you spoke," replied Donald,

reminded by this explanation that he had come

to Captain Patterdale's house for a purpose. "Is

Ned at home?"

"No; he has gone up to Searsport to stay

over Sunday with uncle Henry."

"Has he? I'm sorry. Is your father at home?"

"He is in his library, and there is some one

with him. Won't you sit down, Don John?"

"Thank you," added Donald, seating himself

in a rustic chair. "It is very warm this afternoon."

Nellie actually laughed, for she was conscious

of the difficulties of the situation—more so than

her visitor. But we must do our hero—for such

he is—the justice to say, that he did not refer to

the exhausted topic with the intention of confining

the conversation to it, but to introduce the

business which had called him to the house.

"It is intensely hot, Don John," laughed

Nellie.

"But I was going to ask you if you would

not like to take a sail," said Donald, with a

blush. "With your father, I mean," added he,

with a deeper blush, as he realized that he had[15]

actually asked a girl to go out in a boat with

him.

"I should be delighted to go, but I can't.

Mother won't let me go on the water when the sun

is out, it hurts my eyes so," answered Nellie;

and the young man was sure she was very sorry

she could not go.

"Perhaps we can go after sunset, then," suggested

Donald. "I am sorry Ned is not at home;

for his yacht is finished, and father says the paint

is dry enough to use her. We are going to have

a little trial trip in her over to Turtle Head,

and, perhaps, round by Searsport."

"Is the Sea Foam really done?" asked Nellie,

her eyes sparkling with delight.

"Yes, she is all ready, and father will deliver

her to Ned on Monday, if everything works right

about her. I thought some of your folks, especially

Ned, would like to be in her on the first

trip."

"I should, for one; but I suppose it is no use

for me to think of it. My eyes are ever so much

better, and I hope I shall be able to sail in the

Sea Foam soon."

"I hope so, too. We expect she will beat the

Skylark; father thinks she will."[16]

"I don't care whether she does or not," laughed

Nellie.

"Do you think I could see your father just a

moment?" asked Donald. "I only want to know

whether or not he will go with us."

"I think so; I will go and speak to him. Come

in, Don John," replied Nellie, rising from her

lolling-chair, and walking around the corner of

the house to the front door.

Donald followed her. The elegant mansion was

located on a corner lot, with a broad hall through

the centre of it, on one side of which was the

large drawing-room, and on the other the sitting

and dining-rooms. At the end of the great hall

was a door opening into the library, a large apartment,

which occupied the whole of a one-story

addition to the original structure. It had also an

independent outside door, which opened upon the

piazza; and opposite to it was a flight of steps,

down to the gravel walk terminating at a gate

on the cross street. People who came to see

Captain Patterdale on business could enter at this

gate, and go to the library without passing

through the house. On the present occasion,

a horse and wagon stood at the gate, which indi[17]cated

to Miss Nellie that her father was engaged.

This team had stood there for an hour, and

Donald had watched it for half that time, waiting

for the owner to leave, though he was not at all

anxious to terminate the interview with his fair

schoolmate.

Nellie knocked at the library door, and her father

told her to come in. She passed in, while Donald

waited the pleasure of the rich man in the hall.

He was invited to enter. Captain Patterdale

was evidently bored by his visitor, and gave the

young man a cordial greeting. Donald stated his

business very briefly; but the captain did not say

whether he would or would not go upon the trial

trip of the Sea Foam. He asked a hundred questions

about the new yacht, and it was plain that

he did not care to resume the conversation with

his visitor, who walked nervously about the room,

apparently vexed at the interruption, and dissatisfied

thus far with the result of his interview

with the captain.

What would have appeared to be true to an observer

was actually so. The visitor was one Jacob

Hasbrook, from a neighboring town, and his reputation

for honesty and fair dealings was not the[18]

best in the world. Captain Patterdale held his

note, without security, for thirteen hundred and

fifty dollars. Hasbrook had property, but his

creditors were never sure of him till they were

paid. At the present interview he had astonished

Captain Patterdale by paying the note in full,

with interest, on the day it became due. But it

was soon clear enough to the rich man that the

payment was only a "blind" to induce him to

embark in a doubtful speculation with Hasbrook.

The nature and immense profits of the enterprise

had been eloquently set forth by the

visitor, and his own capacity to manage it enlarged

upon; but the nabob, who had made his

fortune by hard work, was utterly wanting in enthusiasm.

He had received the money in payment

of his note, which he had expected to lose,

or to obtain only after resorting to legal measures,

and he was fully determined to have nothing more

to do with the man. He had said all this as

mildly as he could; but Hasbrook was persistent,

and probably felt that in paying an honest

debt he had thrown away thirteen hundred and

fifty dollars.

He would not go, though Captain Patterdale[19]

gave him sufficient excuse for doing so, or even

for cutting his acquaintance. The rich man continued

to talk with Don John, to the intense disgust

of the speculator, who stood looking at a tin

box, painted green, which lay on a chair. Perhaps

he looked upon this box as the grave of his hopes;

for it contained the money he had just paid to the

captain—the wasted money, because the rich man

would not embark with him in his brilliant enterprise,

though he had taken so much pains, and

parted with so much money, to prove that he was

an honest man. He appeared to be interested in

the box, and he looked at it all the time, with

only an impatient glance occasionally at the nabob,

who appeared to be trifling with his bright hopes.

The tin chest was about nine inches each way,

and contained the private papers and other valuables

of the rich man, including, now, the thirteen

hundred and fifty dollars just received.

Captain Patterdale was president of the Twenty-first

National Bank of Belfast, which was located

a short distance from his house. The tin box was

kept in the vaults of the bank; but the owner

had taken it home to examine some documents

at his leisure, intending to return it to the bank[20]

before night. As it was in the library when Mr.

Hasbrook called, the money was deposited in it

for safe keeping over night.

"I'm afraid I can't go with you, Donald," said

Captain Patterdale, after he had asked him all the

questions he could think of about the Sea Foam.

"I am sorry, sir; for Miss Nellie wanted to go,

and I was going to ask father to wait till after

sunset on her account," added the young man.

Mr. Hasbrook began to look hopeful; for the

last remark of the nabob indicated a possible termination

of the conversation. Donald began his

retreat toward the hall of the mansion, for he

wanted to see the fair daughter again; but he had

not reached the door before the captain called him

back.

"I suppose your father wants some more money

to-night," said he, feeling in his pocket for the

key to open the tin box.

"He didn't say anything to me about it, sir,"

replied Donald; "I don't think he does."

Hasbrook looked hopeless again; for Captain

Patterdale began to calculate how much he had

paid, and how much more he was to pay, for the

yacht. While he was doing so, there was a[21]

knock at the street door, and, upon being invited

to do so, Mr. Laud Cavendish entered the library

with a bill in his hand.

Mr. Laud Cavendish was a great man in his own

estimation, and a great swell in the estimation

of everybody else. He was a clerk or salesman

in a store; but he was dressed very elegantly for

a provincial city like Belfast, and for a "counter-jumper"

on six or eight dollars a week. He was

about eighteen years old, tall, and rather slender.

His upper lip was adorned with an incipient mustache,

which had been tenderly coaxed and colored

for two years, without producing any prodigious

result, though it was the pride and glory of

the owner. Mr. Cavendish was a dreamy young

gentleman, who believed that the Fates had made

a bad mistake in his case, inasmuch as he was

the son of an honest and industrious carpenter,

instead of the son and heir of one of the nabobs

of Belfast. He believed that he was fitted to

adorn the highest circle in society, to shine

among the aristocracy of the city, and it was a

cruel shame that he should be compelled to work

in a store, weigh out tea and sugar, carry goods

to the elegant mansions where he ought to be ad[22]mitted

at the front, instead of the back, door,

collect bills, and perform whatever other service

might be required of him. The Fates had blundered

and conspired against him; but he was not

without hope that the daughter of some rich

man, who might fall in love with him and his

mustache, would redeem him from his slavery

to an occupation he hated, and lift him up to

the sphere where he belonged. Laud was "soaring

after the infinite," and so he rather neglected

the mundane and practical, and his employer did

not consider him a very desirable clerk.

Mr. Laud Cavendish came with a bill in his

hand, the footing of which was the sum due his

employer for certain necessary articles just

delivered at the kitchen door of the elegant

mansion. Captain Patterdale opened the tin box,

and took therefrom some twenty dollars to pay

the bill, which Laud receipted. Mr. Hasbrook

hoped he would go, and that Don John would go;

and perhaps they would have gone if a rather exciting

event had not occurred to detain them.

"Father! father!" exclaimed Miss Nellie, rushing

into the library.

"What's the matter, Nellie?" demanded her[23]

father, calmly; for he had long been a sea captain,

and was used to emergencies.

"Michael has just dropped down in a fit!"

gasped Nellie.

"Where is he?"

"In the yard."

Captain Patterdale, followed by his three visitors,

rushed through the hall, out at the front

door, near which the unfortunate man had fallen,

and, with the assistance of his companions, lifted

him from the ground. Michael was the hired

man who took care of the horses, and kept the

grounds around the elegant mansion in order.

He was raking the gravel walk near the piazza

where Nellie was laboring to keep cool. As we

have hinted before, and as Nellie and Don John

had several times repeated, the day was intensely

hot. The sun where the man worked was absolutely

scorching, and the hired man had experienced

a sun-stroke. Captain Patterdale and his

visitors bore him to his room in the L, and Don

John ran for the doctor, who appeared in less than

ten minutes. The visitors all did what they

could, Mr. Laud Cavendish behaving very well.

Michael's wife and other friends soon arrived,[24]

and there was nothing more for Laud to do. He

went down stairs, and, finding Nellie in the hall,

he tried to comfort her; for she was very much

concerned for poor Michael.

"Do you think he will die, Mr. Cavendish?"

asked she, almost as much moved as though the

poor man had been her father.

"O, no! I think he will recover. These Irishmen

have thick heads, and they don't die so

easily of sun-stroke; for that's what the doctor

says it is," replied Laud, knowingly.

Nellie thought, if this was a true view of coup de

soleil, Laud would never die of it. She thought

this; but she was not so impolite as to say it. She

asked him no more questions; for she saw Don

John approaching through the dining-room.

"Good afternoon, Miss Patterdale," said Laud,

with a bow and a flourish, as he retired towards

the library, where he had left his hat.

In a few moments more, the rattle of the

wagon, with which he delivered goods to the

customers, was heard as he drove off. Don John

came into the hall, and Nellie asked him ever so

many questions about the condition of Michael,

and what the doctor said about him; all of[25]

which the young man answered to the best of his

ability.

"Do you think he will die, Don John?" she

asked.

"I am sure I can't tell," replied Donald; "I

hope not."

"Michael is real good, and I am so sorry for

him!" added Nellie.

But Michael is hardly a personage in our story,

and we do not purpose to enter into the diagnosis

of his case. He has our sympathies on the merit

of his sufferings alone, and quite as much for Nellie's

sake; for it was tender, and gentle, and kind

in her to feel so much for a poor Irish laborer.

While she and Donald were talking about the

case, Mr. Hasbrook came down stairs, and passed

through the hall into the library, where he, also,

had left his hat. In a few moments more the rattle

of his wagon was heard, as he drove off, indignant

and disgusted at the indifference of the nabob

in refusing to take an interest in his brilliant enterprise.

He was angry with himself for having

paid his note before he had enlisted the payee in

his cause.

"How is he, father?" asked Nellie, as Captain

Patterdale entered the hall.[26]

"The doctor thinks he sees some favorable

symptoms."

"Will he die?"

"The doctor thinks he will get over it. But

he wants some ice, and I must get it for him."

"I suppose you will not go in the Sea Foam

now?" asked Donald.

"No; it is impossible," replied the captain,

as he passed into the dining-room to the refrigerator.

The father was like the daughter; and though

he was a millionnaire, or a demi-millionnaire—we

don't know which, for we were never allowed

to look over his taxable valuation—though he was

a nabob, he took right hold, and worked with

his own hands for the comfort and the recovery

of the sufferer. It was creditable to his heart that

he did so, and we never grudge such a man his

"pile," especially when he has earned it by his

own labor, or made it in honorable, legitimate

business. The captain went up stairs again with

a large dish of ice, to assist the doctor in the

treatment of his patient.

Donald staid in the hall, talking with Miss Nellie,

as long as he thought it proper to do so, though[27]

not as long as he desired, and then entered the

library where he, also, had left his hat. Perhaps

it was a singular coincidence that all three of the

visitors had left their hats in that room; but then

it was not proper for them to sit with their hats

on in the presence of such a magnate as Captain

Patterdale, and no decent man would stop for a

hat when a person had fallen in a fit.

Captain Patterdale's hat was still there; and,

unluckily, there was something else belonging to

him which was not there.[28]

CHAPTER II.

ABOUT THE TIN BOX.

Captain Patterdale worked with the

doctor for a full hour upon poor Michael,

who at the end of that time opened his eyes, and

soon declared that he was "betther entirely."

He insisted upon getting up, for it was not "the

likes of himself that was to lay there and have

his honor workin' over him." But the doctor

and the nabob pacified him, and left him, much

improved, in the care of his wife.

"How is he, Dr. Wadman?" asked the sympathizing

Nellie, as they came down stairs together.

"He is decidedly better," replied the physician.

"Will he die?"

"O, no; I think not. His case looks very

hopeful now."[29]

"I thought folks always died with sun-stroke,"

said Nellie, more cheerfully.

"No; not unless their heads are very soft,"

laughed the doctor.

"Well, I shouldn't think Laud Cavendish would

dare to go out when the sun shines," added the

fair girl, with a snap of her bright eyes.

"It isn't quite safe for him to do so. Unfortunately,

such people don't know their own heads.

I will come in again after tea," said the doctor,

as he went out of the house, at the front door;

for he had not left his hat in the library.

"I am so glad Michael is better!" continued

Nellie. "When I saw him drop, I felt as cold

as ice, and I was afraid I should drop too before

I could get to the library."

"Did you see him fall, Nellie?" asked her

father.

"Yes; he gave a kind of groan, and then fell;

he was—"

"Gracious!" exclaimed Captain Patterdale, interrupting

her all of a sudden.

He turned on his heel, and walked rapidly into

the library. Nellie was startled, and was troubled

with a suspicion that her father had a coup[30]

de soleil, or coup de something-else; for he did not

often do anything by fits and starts. She followed

him into the library. It was a fact that

the captain had left his hat there; but it was not

for this article, so necessary in a hot day, that

he hastened thus abruptly into the room. Nellie

found him flying around the apartment in a high

state of excitement for him. He was looking

anxiously about, and seemed to be very much

disturbed.

"What in the world is the matter, father?"

asked Nellie.

"Where is your mother?"

"She has gone over to Mrs. Rodman's."

"Hasn't she been back?"

"No, certainly not; I was just going over to

tell her what had happened to Michael, when you

came down."

"Who has been in here, Nellie?"

"I don't know that anybody has. I haven't

seen any one. What's the matter, father? what

in the world has happened?"

"I left my tin box here when I went out to

see to Michael, and now it is gone," answered

Captain Patterdale, anxiously. "I didn't know[31]

but that your mother had come in and taken care

of it."

"The tin box gone?" exclaimed Nellie.

"Why, what can have become of it?"

"That is just what I should like to know,"

added the captain, as he renewed his search in

the room for the treasure chest.

It was not in the library, and then he looked

in the great hall and in the little hall, in the

drawing-room, the sitting-room, and the dining-room;

but it was not in any of these. He knew

he had left it on the chair near where he was sitting

when he went out of the room. Then he

examined the spring-lock on the door of the

library which led into the side street. It was

closed and securely fastened. The door shut itself

with a patent invention, and when shut it

locked itself, so that anybody could get out, but

no one could get in unless admitted.

"Where were you when I was up stairs, Nellie?"

asked Captain Patterdale, as he seated

himself in his arm-chair, to take a cool view of

the whole subject.

"I was in the hall most of the time," she replied.[32]

"Who has been in the library?"

"Let me see; Laud Cavendish came down

first, and went out through the library."

The captain rubbed his bald head, and seemed

to be asking himself whether it was possible for

Mr. Laud Cavendish to do so wicked a deed as

stealing that tin box. He did not believe the

young swell had the baseness or the daring to

commit so great a crime. It might be, but he

could not think so.

"Who else has been in here?" he inquired,

when he had hastily considered all he knew about

the moral character of Laud.

"That other man who was with you—I don't

know his name—the one that was here when I

came in with Don John."

"Mr. Hasbrook."

"He went out through the library. I thought

he looked real ugly too," added Nellie. "He

kept fidgeting about all the time I was here."

"And all the time he was here himself. He

went out through the library—did he?"

"Yes, sir."

Captain Patterdale mentally overhauled the

character of Mr. Hasbrook. It was unfortunate[33]

for his late debtor that his character was not first

class, and between him and Laud Cavendish the

probabilities were altogether against Hasbrook.

He had evidently been vexed and angry because

he failed to carry his point, and his cupidity

might have been stimulated by revenge. But the

captain was a fair and just man, and in a matter of

this kind, involving the reputation of any person,

he kept his suspicions to himself.

"Who else has been in the library, Nellie?"

he asked.

"No one but Don John," replied she. And

whatever Laud or Hasbrook might have done in

wickedness, Nellie had too much regard for her

friend and schoolmate to admit for one instant the

possibility of his doing anything wrong, much less

his committing so gross a crime as the stealing

of the tin box and its valuable contents.

Captain Patterdale was hardly less confident of

the integrity of Donald. Certainly it was not

necessary to suspect him when the possibilities of

guilt included two such persons as Laud and Hasbrook.

Donald was rather distinguished, in school

and out, as a good boy, and he ought to have the

full benefit of his reputation.[34]

"You don't think Don John took the box—do

you, father?" asked Nellie, as her father was meditating

on the circumstances.

"Certainly not, Nellie," protested the captain,

warmly; "I don't know that anybody has taken

it."

"I know Don John would not do such a

thing."

"I don't believe he would."

"I know he would not."

Her father thought she was just a little more

earnest in her uncalled-for defence of the young

man than was necessary, and for the first time in

his life it occurred to him that she was more interested

in him than he wished her to be; for,

as Donald was only the son of a poor boat-builder,

such a strong friendship might be embarrassing

in the future. However, this was only the shadow

of a passing thought, which divided his attention

only for a moment. The loss of the tin box was

the question of the hour, and "society" topics

were not just then in order.

"I have no idea that Don John took the box,"

replied Captain Patterdale. "I am more willing

to believe either of the other two who were in the[35]

library took it than that he did. But he was the

last of the three who went out through this room.

He may be able to give me some information, and

I will go down and see him. He and his father

were going off in the new yacht—were they not?"

"Yes, sir."

"You need not say a word about the box to

any one, Nellie, nor even that it is lost," added

the captain. "If I do not find it, I shall employ a

skilful detective to look it up, and he may prefer

to work in the dark."

"I will not mention it, father," replied Nellie.

"What was in the box? Was it money?"

"I put thirteen hundred and fifty dollars into

it, but I took out twenty to pay the bill that Laud

brought. It contains my deeds, leases, policies

of insurance, and my notes, and these papers

are really more valuable to me than the money.

Luckily, my bonds and securities are in another

box, in the vault of the bank."

"Then you will lose over thirteen hundred

dollars if you don't find the box?"

"More than that, I am afraid, for I shall

hardly be able to collect all the money due on the

notes if I lose them," replied the captain, as he

left the house.[36]

He walked down to the boat shop of Mr. Ramsay.

It was on the shore, and near it was the

house in which the boat-builder lived. Neither

Don John nor his father was at the shop, but a

sloop yacht, half a mile out in the bay, seemed to

be the Sea Foam. She was headed towards the

shore, however, and Captain Patterdale seated

himself in the shade of the shop to await its

arrival, though he hardly expected to obtain any

information in regard to the box from Donald.

While he was sitting there, Mr. Laud Cavendish

appeared with a large basket in his hand. The

counter-jumper started when he turned the corner

of the shop, and saw the nabob seated there.

"Going a-fishing?" asked the captain.

"Yes, sir; I'm going over to Turtle Head to

camp out over Sunday," replied Laud. "How is

Michael, sir?"

"He is much better, and is doing very well."

"I'm glad of it," added Laud, as he carried

his basket down to a sail-boat which was partly

aground, and deposited it in the forward cuddy.

Captain Patterdale wanted to talk with Laud,

but he did not like to excite any suspicions on his

part. If the young man had taken the box he[37]

would not be likely to go off on an island to stay

over Sunday. Besides, it was evident from the

position of the boat, and the fact that it contained

several articles necessary for a fishing excursion,

in addition to those in the basket, that

Laud had made his arrangements for the trip before

he visited the library of the elegant mansion.

If he had taken the box, he would probably have

changed his plans. It was not likely, therefore,

that Laud was the guilty party.

"Are you going alone?" asked the captain,

walking down the beach to the boat.

"Yes, sir; I couldn't get any one to go with

me. I tried Don John, but he won't go off to stay

over Sunday," replied Laud, with a sickly grin.

"I commend his example to you. I don't

think it is a good way to spend Sunday."

"It's the only time I can get to go. I've been

trying to got off for a month."

"Saturday must be a bad time for you to

leave," suggested the captain.

"It is rather bad," added Laud, as he shoved

off the bow of the boat, for he seemed to be in

haste to get away.

"By the way, Laud, did you notice a tin box[38]

in my library when you were there this afternoon?"

asked the nabob, with as much indifference

in his manner and tone as he could command.

"A tin box?" repeated Laud, busying himself

with the jib of the sail-boat.

"Yes; it was painted green."

"I don't remember any box," answered Laud.

"Didn't you see it? I opened it to take out

the money I paid you."

"I didn't mind. I was receipting the bill

while you were getting the money ready. You

know I sat down at your desk."

"Yes; I know you did; but didn't you see the

box?"

"No, sir; I don't remember seeing any box,"

said Laud, still fussing over the sail, which certainly

did not need any attention.

"You went out through the library when you

came down from Michael's room—didn't you?"

continued the captain.

"Yes, sir; I did. I left my hat in there."

"Did you see the box then?"

"Of course I didn't. If I had, I should have

remembered it," replied Laud, with a grin. "I

just grabbed my hat, and ran, for I had been[39]

in the house some time; and I got a blessing for

being away so long when I went back to the

store."

"You didn't see the box, then?"

"If it was there, I suppose I saw it; but I

didn't take any notice of it. Why? is the box

lost?"

"I want to get another like it. Haven't you

anything of the sort in the store?"

"We have some cake and spice boxes. They

are tin, and painted on the outside."

"Those will not answer the purpose. It's a

very hot day," added the captain, as he wiped

the perspiration from his face, and walked back

to the shade of the shop.

Mr. Laud Cavendish stepped into the sail-boat,

hoisted the sails, and shoved her off into deep

water with an oar. Captain Patterdale thought,

and then he did not know what to think. Was

it possible Laud had not noticed that tin box,

which had been on a chair out in the middle of

the room? If he had not, why, then he had not;

but if he had Laud had more cunning, more self-control,

and more ingenuity than the captain had

ever given him the credit, or the discredit, of pos[40]sessing,

for there was certainly no sign of guilt in

his tone or his manner, except that he did not look

the inquirer square in the face when he answered

his questions, though some guilty people can even

do this without wincing.

Captain Patterdale watched the departing and

the approaching boats, still considering the possible

relation of Laud Cavendish to the tin box.

If the fellow had stolen it, he would not go off

on an island to stay over Sunday, leaving the box

behind to betray him; and this argument seemed

to be conclusive in his favor. The captain had

looked into the boat, and satisfied himself that

the box was not there; unless it was in the basket,

which appeared to contain so many other

things that there was no room for it. On the

whole, the captain was willing to acquit Mr.

Laud Cavendish of the act, partly, perhaps, because

this had been his first view of the matter.

It was more probable that Hasbrook, angry and

disappointed at his failure, had put the box into

his wagon, and returned to the neighboring town,

where, as before stated, his reputation was not

first class, though, perhaps, not many people believed

him capable of stealing outright, without[41]

the formality of getting up a mining company,

or making a trade of some sort. But Donald had

been the last of the trio of visitors who passed

through the library, and the captain wanted to

see him.

The Sea Foam, with snowy sails just from the

loft, and glittering in her freshly-laid coat of

white paint, ran up to a wharf just below the boat

shop. Donald was at the helm, and he threw

her up into the wind just before she came to the

pier, so that when she forged ahead, with her sails

shaking in the wind, her head came up within

a few inches of the landing-place. Mr. Ramsay

fended her off, and went ashore with a line in

his hand, which he made fast to a ring. Captain

Patterdale walked around to the wharf, as soon as

he saw where she was to make a landing.

"Well, how do you like her, Sam?" said Donald

to a young man of his own age in the standing-room

with him.

"First rate; and I hope your father will go to

work on mine at once," replied the passenger.

"You will lay down the keel on Monday—won't

you, father?"

"What?" asked Mr. Ramsay, who had seated

himself on a log on the wharf.[42]

"You will lay down the keel of the boat for

Mr. Rodman on Monday—won't you?" repeated

Donald.

"Yes, if I am able; I don't feel very well to-day."

And the boat-builder doubled himself up,

as though he was in great pain.

The young man in the standing-room of the

Sea Foam was Samuel Rodman, a schoolmate of

Donald, whose father was a wealthy man, and

had ordered another boat like the Skylark, which

had been the model for the new yacht. He had

come down to see the craft, and had been invited

to take a sail in her; but an engagement

had prevented him from going as far as Turtle

Head, and the boat-builder and his son had returned

to land him, intending still to make the

trip. By this time Captain Patterdale had reached

the end of the wharf. He went on board of the

Sea Foam, and looked her over with a critical

eye, and was entirely satisfied with her. He was

invited to sail in her for as short a time as he

chose, but he declined.

"By the way, Donald, did you see the green

tin box when you were in my library this afternoon?"

he asked, when all the topics relating to

the yacht had been disposed of.[43]

"Yes, sir; I saw you take some money from

it," replied Donald.

"Then you remember the box?"

"Yes, sir."

"Did you notice it when you came out—I mean,

when you left the house?"

"I don't remember seeing it when I came out,"

answered Donald, wondering what these questions

meant.

"I want to get another box just like that one.

Did you take particular notice of it?"

"No, sir; I can't say I did."

"You didn't stay any time in the library after

you came down from Michael's room, did you?"

"No, sir; I only went for my hat, and didn't

stay there a minute."

"And you didn't notice the tin box?"

"No, sir; I didn't see it at all when I came

out."

"Then of course you didn't see any marks upon

it," added the captain, with a smile.

"If I didn't see the box, I shouldn't have

been likely to see the marks," laughed Donald.

"What marks were they, sir?"

"It's of no consequence, if you didn't see them.[44]

The box was in the library—wasn't it?—when you

went out."

"I don't know whether it was or not. I only

know that I don't remember noticing it," said

Donald, who thought the captain's question was

a very queer one, after those he had just answered.

The nabob was no better satisfied with Donald's

answers than he had been with those of Laud

Cavendish, except that the former looked him full

in the face when he spoke. He obtained no

information, and went home to seek it at other

sources.

"I think I won't go out again, Donald," said

Mr. Ramsay, when Captain Patterdale had left. "I

don't feel very well, and you may go alone."

"Do you feel very sick, father?" asked the son,

in tones of sympathy.

"No; but I think I will go into the house and

take some medicine. You can run over to Turtle

Head alone," added the boat-builder, as he walked

towards the house.

"Can't you go any how, Sam?" said Donald,

turning to his friend.

"No, I must go home now. I have to drive over[45]

to Searsport after my sister," replied Sam, as he

left the yacht, and walked up the wharf.

Donald hoisted the jib of the Sea Foam, shoved

off her head, and laid her course, with the wind

over the quarter, for Turtle Head—distant about

seven miles.[46]

CHAPTER III

THE YACHT CLUB AT TURTLE HEAD.

The Sea Foam was a sloop yacht, thirty feet in

length, and as handsome as a picture in an

illustrated paper, than which nothing could be

finer. It was a fact that she had cost twelve hundred

dollars; but even this sum was cheaper than

she could have been built and fitted up in Boston

or Bristol. She was provided with everything

required by a first class yacht of her size, both for

the comfort and safety of the voyager, as well

as for fast sailing. Though Mr. Ramsay, her

builder, was a ship carpenter, he was a very intelligent

and well-read man. He had made yachts a

specialty, and devoted a great deal of study to

the subject. He had examined the fastest craft in

New York and Newport, and had their lines in his

head. And he was a very ingenious man, so that

he had the tact to make the most of small spaces,[47]

and to economize every spare inch in lockers,

closets, and stow-holes for the numerous articles

required in a pleasure craft. He had learned his

trade as a ship carpenter and joiner in Scotland,

where the mechanic's education is much more

thorough than in our own country, and he was an

excellent workman.

The cabin of the Sea Foam was about twelve

feet long, with transoms on each side, which were

used both as berths and sofas. They were supplied

with cushions covered with Brussels carpet,

with a pillow of the same material at each end.

Through the middle, fore and aft, was the centre-board

casing, on each side of which was a table

on hinges, so that it could be dropped down

when not in use. The only possible objection to

this cabin, in the mind of a shoreman, would have

been its lack of height. It was necessarily "low

studded," being only five feet from floor to ceiling,

which was rather trying to the perpendicularity

of a six-footer. But it was a very comfortable

cabin for all that, though tall men were compelled

to be humble within its low limits.

It was entered from the standing-room by a

single step covered with plate brass, in which the[48]

name of the yacht was wrought with bright copper

nails. On each side of the companion-way was a

closet, one of which was for dishes, and the other

for miscellaneous stores. The trunk, which readers

away from boatable waters may need to be

informed is an elevation about a foot above the

main deck, to afford head-room in the middle of

the cabin, had three deck lights, or ports, on

each side. At one end of the casing of the centre-board

was a place for the water-jar, and a rack

for tumblers. In the middle were hooks in the

trunk-beams for the caster and the lantern. The

brass-covered step at the entrance was movable,

and when it was drawn out it left an opening into

the run under the standing-room, where a considerable

space was available for use. In the centre

of it was the ice-chest, a box two feet square,

lined with zinc, which was rigged on little

grooved wheels running on iron rods, like a

railroad car, so that the chest could be drawn

forward where the contents could be reached.

On each side of this box was a water-tank, holding

thirty gallons, which could be filled from the

standing-room. The water was drawn by a faucet

lower than the bottom of the tank in a recess at[49]

one side of the companion-way. The tanks were

connected by a pipe, so that the water was drawn

from both. At the side of the step was a gauge

to indicate the supply of fresh water on board.

Forward of the cabin, in the bow of the yacht,

was the cook-room, with a scuttle opening into it

from the forecastle. The stove, a miniature affair,

with an oven large enough to roast an eight-pound

rib of beef, and two holes on the top, was

in the fore peak. It was placed in a shallow pan

filled with sand, and the wood-work was covered

with sheet tin, to guard against fire. Behind the

stove was a fuel-bin. On each side of the cook

room was a shelf eighteen inches wide at the

bulk-head and tapering forward to nothing. Under

it were several lockers for the galley utensils

and small stores. The room was only four feet

high, and a tall cook in the Sea Foam would

have found it necessary to discount himself. On

the foremast was a seat on a hinge, which could

be dropped down, on which the "doctor" could sit

and do his work, roasting himself at the same

time he roasted his beef or fried his fish. Everything

in the cook-room and the cabin, as well as

on deck, was neat and nice. The cabin was cov[50]ered

with a handsome oil-cloth carpet, and the

wood was white with zinc paint, varnished, with

gilt moulding to ornament it. Edward Patterdale,

who was to be the nominal owner and the

real skipper of this beautiful craft, intended to

have several framed pictures on the spaces between

the deck lights, a clock in the forward end

over the cook-room door, and brass brackets for

the spy-glass in the companion-way.

On deck the Sea Foam was as well appointed

as she was below. Her bowsprit had a gentle

downward curve, her mast was a beautiful spar,

and her topmast was elegantly tapered and set

up in good shape. Unlike most of the regular

highflyer yachts, her jib and mainsail were

not unreasonably large. Mr. Ramsay did not intend

that it should be necessary to reef when it

blew a twelve-knot breeze, and, like the Skylark,

she was expected to carry all sail in anything

short of a full gale. But she was provided with

an abundance of "kites," including an immense

gaff-topsail, which extended on poles far above

the topmast head, and far beyond the peak, a

balloon-jib, a jib-topsail, and a three-cornered

studding-sail. The balloon-jib, or the jib-topsail,[51]

was bent on with snap-hooks when it was needed,

for only one was used at the same time. These

extra sails were to be required only in races, and

they were kept on shore. One stout hand could

manage her very well, though two made it easier

work, and six were allowed in a race.

Donald seated himself in the standing-room,

with the tiller in his right hand. As soon as he had

run out a little way, his attention was excited by

discovering three other sloop yachts coming down

the bay. In one of them he recognized the Skylark,

and in another the Christabel, while the third

was a stranger to him, though he had heard of the

arrival that day of a new yacht from Newport,

and concluded this was she. He let off his sheet,

and ran up to meet the little fleet.

"Sloop, ahoy!" shouted Robert Montague, from

the Skylark, as Donald came within hailing distance.

"On board the Skylark!" replied the skipper

of the Sea Foam.

"Is that you, Don John?"

"Ay, ay."

"What sloop is that?" demanded Robert.

"The Sea Foam."[52]

"Where bound?"

"Over to Turtle Head."

"We are bound there; come with us."

"Ay ay."

"Hold on a minute, Don John," shouted some

one from the Christabel.

Each of the yachts had a tender towing astern,

and that from the Christabel, with five boys in it,

immediately put off, and pulled to the Sea Foam.

"Will you take us on board, Don John?"

asked Gus Barker, as the tender came alongside.

"Certainly; I'm glad to have your company,"

replied Donald, who had thrown the yacht up

into the wind.

Three of the party in the tender jumped upon

the deck of the Sea Foam, and the boat returned

to the Christabel. Each of the yachts appeared

to have half a dozen or more on board of her, so

that there was quite a party on the way to Turtle

Head. The sloops filled away again, the Skylark

and the new arrival having taken the lead, while

the other two were delayed.

"What sloop is that with the Skylark?" asked

Donald.

"That's the Phantom. She got here from New[53]port

this forenoon. Joe Guilford's father bought

her for him. She is the twin sister of the Skylark,

and they seem to make an even thing of it in sailing,"

replied Gus Barker.

"You have quite a fleet now," added Donald.

"Yes; and we are going to form a Yacht Club.

We intend to have a meeting over at Turtle Head.

Will you join, Don John?"

"I haven't any boat."

"Nor I, either. All the members can't be skippers,"

laughed Gus. "I am to be mate of the Sea

Foam, and that's the reason I wanted to come on

board of her."

"And I am to be one of her crew," added

Dick Adams.

"And I the steward," laughed Ben Johnson.

"I am going down into the cook-room to see

how things look there."

"You will join—won't you, Don?"

"Well, I don't know. I can't afford to run

with you fellows with rich fathers."

"O, get out! That don't make any difference,"

puffed Gus. "The owner of the yacht has to foot

the bills. Besides, we want you, Don John, for

you know more about a boat than all the rest of

the fellows put together."[54]

"Well, I shall be very glad to do anything I

can to help the thing along; but there are plenty

of fellows that can sail a boat better than I can."

"But you know all about a boat, and they want

you for measurer. We have the printed constitution

of a Yacht Club, which Bob Montague got in

Boston, and according to that the measurer is entitled

to ten cents a foot for measuring a yacht;

so you may make something out of your office."

"I don't want to make any money out of it,"

protested Donald.

"You can make enough to pay your dues, for

we have to raise some money for prizes in the

regattas; and we talk of having a club house

over on Turtle Head," rattled Gus, whose tongue

seemed to be hung on a pivot in his enthusiasm

over the club. "Every fellow must be voted in,

and pay five dollars a year for membership. We

shall have some big times.—We are gaining on

the Skylark, as true as you live!"

"I think we are; but I guess Bob isn't driving

her," added Donald.

"She carries the same sail as the Sea Foam. I

would give anything to beat her. Make her do

her best, Don John."[55]

"I will," laughed the skipper, who had kept

one eye on the Skylark all the time.

He trimmed the sails a little, and began to be

somewhat excited over the prospect of a race.

The Christabel was three feet longer than the

other yachts, and it was soon evident that in a

light wind she was more than a match for them,

for she ran ahead of the Sea Foam. Her jib and

mainsail were much larger in proportion to her

size than those of the other sloops, but she was

not an able boat, not a heavy-weather craft, like

them. The Sea Foam continued to gain on the

Skylark, till she was abreast of her, while the

Phantom kept about even with her. But then

Robert Montague was busy all the time talking

with his companions about the Yacht Club, and

did not pay particular attention to the sailing of

his boat. The Sea Foam began to walk ahead

of him, and then, for the first time, it dawned

upon him that the reputation of the Skylark was

at stake. He had his crew of five with him, and

he placed them in position to improve the sailing

of his craft. He ordered one of his hands to give a

small pull on the jib-sheet, another to let off the

main sheet a little, and a third to haul up the[56]

centre-board a little more, as she was going

free.

The effect of this attention on the part of the

skipper of the Skylark was to lessen the distance

between her and the Sea Foam; they were abeam

of each other, with the Phantom in the same line.

The Christabel was about a cable's length ahead

of them.

"She's game yet," said Gus Barker, his disappointment

evident in the tones of his voice, as

the Skylark came up to the Sea Foam.

"This is a new boat, and I haven't got the

hang of her yet," Donald explained. "Haul up

that fin a little, Dick."

"What fin?"

"The centre-board."

"Ay, ay," replied Dick, as he obeyed the order.

"Steady! that's enough," continued Donald,

who now narrowly watched the sailing of the

Sea Foam, to assure himself that she did not make

too much leeway.

"That was what she wanted!" exclaimed Gus,

when the yacht began to gain again, and in a few

minutes was half a length ahead.

The Start. Page 51.

"But not quite so much of it," replied Donald,[57]

when he saw that his craft was sliding off a very

little. "Give her just three inches more fin,

Dick."

The centre-board was dropped this distance, and

the tendency to make leeway thus corrected.

"She is gaining still!" cried Gus, delighted.

"Not much; it is a pretty even thing," added

Donald.

"No matter; we beat her, and I don't care if

it's only half an inch in a mile."

"But the Christabel is leading us all. She is

sure of all the first prizes."

"Not a bit of it. She has to reef when there's

a capful of wind. In a calm she will beat us, but

when it blows we shall wax her all to pieces."

"Hallo!" shouted Mr. Laud Cavendish, whose

small sail-boat was overhauled about half way

over to Turtle Head. "Is that you, Don John?"

"I believe so," replied Donald.

"Where you going?"

"Over to Turtle Head. Want us to give you

a tow?"

"No; you needn't brag about your old tub.

She don't belong to you; and I'm going to have

a boat that will beat that one all to splinters,"

replied Laud.[58]

"All right; fetch her along."

"I say, Don John, I'm going to stop over

Sunday on Turtle Head. Won't you stay with

me?"

"No, I thank you. I must go home to-night,"

answered Donald.

Mr. Laud Cavendish knew very well that Donald

would not spend Sunday in boating and fishing;

and he did not ask because he wanted him.

Besides, for more reasons than one, he did not

desire his company. The Sea Foam ran out of

talking distance of the sail-boat in a moment.

Robert Montague was doing his best to keep up

the reputation of the Skylark; but when the fleet

came up to Turtle Head, she was more than a

length behind. The jib was hauled down, the

yachts came up into the wind, and the anchors

were let go.

"Beat you," shouted Gus Barker.

"Not much," replied Robert. "We will try

that over again some time."

"We are willing," added Donald.

The mainsails were lowered, and the young

yachtmen embarked in the tenders for the shore.

Turtle Head is a rocky point at the northern[59]

extremity of Long Island, in Penobscot Bay.

There were a few trees near the shore, and under

these the party purposed to hold their meeting.

Though the weather was intensely hot on shore,

it was comfortably cool at the Head, where the

wind came over five or six miles of salt water

cool from the ocean. The boys leaped ashore,

and hauled up their boats where the rising tide

could not float them off. There were over twenty

of them, all members of the High School.

"The Sea Foam sails well," said Robert Montague,

as he walked over to the little grove with

Donald.

"Very well, indeed. This is the first time she

has been out, and I find she works first rate,"

replied Donald.

"I want to try it with her some day, when

everything is right."

"Wasn't everything right to-day?" asked Donald,

smiling, for he was well aware that every

boatman has a good excuse for the shortcomings

of his craft.

"No; my tender is twice as heavy as yours,"

added Robert. "I must get your father to build

me one like that of the Sea Foam."[60]

"We will try it without any tenders, which we

don't want in a race."

"Of course I don't know but the Sea Foam

can beat me; but I haven't seen the boat of her

inches before that could show her stern to the

Skylark," said Robert; and it was plain that he

was a little nettled at the slight advantage which

the new yacht had gained.

"I should like to sail her when you try it, for

I have great hopes of the Sea Foam. If my

father has built a boat that will beat the Skylark

in all weathers, he has done a big thing, and it

will make business good for him."

"For his sake I might be almost willing to be

whipped," replied Robert, good-naturedly, as

they halted in the grove.

Charley Armstrong was the oldest member of

the party, and he was to call the meeting to

order, which he did with a brief speech, explaining

the object of the gathering, though everybody

present knew it perfectly well. Charles was then

chosen chairman, and Dick Adams secretary. It

was voted to form a club, and the secretary was

called upon to read the constitution of the "Dorchester

Yacht Club." The name was changed to[61]

Belfast, and the document was adopted as the

constitution of the Belfast Yacht Club. The second

article declared that the officers should

consist of a "Commodore, Vice-Commodore,

Captain of the Fleet, Secretary, Treasurer, Measurer,

a Board of Trustees, and a Regatta Committee;"

and the next business was to elect them,

which had to be done by written or printed ballots.

As the first three officers were required to

be owners in whole, or in part, of yachts enrolled

in the club, there was found to be an alarming

scarcity of yachts. The Skylark, Sea Foam,

Phantom, and Christabel were on hand. Edward

Patterdale and Samuel Rodman had signified

their intention to join, though they were unable

to be present at the first meeting. The Maud, as

Samuel Rodman's new yacht was to be called,

was to be built at once: she was duly enrolled,

thus making a total of five, from whom the first

three officers must be chosen.

The secretary had come supplied with stationery,

and a slip was handed to each member,

after the constitution had been signed. A ballot

was taken for commodore; Robert B. Montague

had twenty votes, and Charles Armstrong one.[62]

Robert accepted the office in a "neat little

speech," and took the chair, which was a sharp

rock. Edward Patterdale was elected vice-commodore,

and Joseph Guilford captain of the fleet.

Donald was chosen measurer, and the other

offices filled to the satisfaction of those elected,

if not of the others. It was then agreed to have a

review and excursion on the following Saturday,

to which the ladies were to be invited.

The important business of the day was happily

finished, and the fleet sailed for Belfast. Having

secured the Sea Foam at her mooring, Donald

hastened home. As he approached the cottage,

he saw a doctor's sulky at the door, and the neighbors

going in and out. His heart rose into his

throat, for there was not one living beneath that

humble roof whom he did not love better than

himself.[63]

CHAPTER IV.

A SAD EVENT IN THE RAMSAY FAMILY.

Donald's heart beat violently as he hastened

towards the cottage. Before he could

reach it, another doctor drew up at the door,

and it was painfully certain that one of the family

was very sick—dangerously so, or two physicians

would not have been summoned. It might be his

father, his mother, or his sister Barbara; and

whichever it was, it was terrible to think of.

His legs almost gave away under him, when he

staggered up to the cottage. As he did so, he

recalled the fact that his father had been ailing

when he went away in the Sea Foam. It must be

his father, therefore, who was now so desperately

ill as to require the attendance of two doctors.

The cottage was a small affair, with a pretty

flower garden in front of it, and a whitewashed

fence around it. But small as it was, it was not[64]

owned by the boat-builder, who, though not in

debt, had hardly anything of this world's goods—possibly

a hundred dollars in the savings' bank,

and the furniture in the cottage. Though he was

as prudent and thrifty as Scotchmen generally

are, and was not beset by their "often infirmity,"

he had not been very prosperous. The business

of ship-building had been almost entirely suspended,

and for several years only a few small

vessels had been built in the city. Ramsay had

always obtained work; but he lived well, and

gave his daughter and his son an excellent education.

Alexander Ramsay's specialty was the building

of yachts and boats, and he determined to make a

better use of his skill than selling it with his labor

for day wages. He went into business for himself

as a boat-builder. When he established himself,

he had several hundred dollars, with which he

purchased stock and tools. He had built several

sail-boats, but the Sea Foam was the largest job

he had obtained. Doubtless with life and health

he would have done a good business. Donald

had always been interested in boats, and he knew

the name and shape of every timber and plank in[65]

the hull of a vessel, as well as every spar and

rope. Though only sixteen, he was an excellent

mechanic himself. His father had taken great

pains to instruct him in the use of tools, and in

draughting and modelling boats and larger craft.

He not only studied the art in theory, but he

worked with his own hands. In the parlor of the

little cottage was a full-rigged brig, made entirely

by him. The hull was not a log, shaped and

dug out, but regularly constructed, with timbers

and planking. When he finished it, only a few

months before his introduction to the reader, he

felt competent to build a yacht like the Sea

Foam, without any assistance; but boys are generally

over-confident, and possibly he overrated

his ability.

With his heart rising up into his throat, Donald

walked towards the cottage. As he passed the

whitewashed gate, one of the neighbors came out

at the front door. She was an elderly woman,

and she looked very sad as she glanced at the

boy.

"I'm glad you have come, Donald; but I'm

afraid he'll never speak to you again," said she.

"Is it my father?" gasped the poor fellow.[66]

"It is; and he's very sick indeed."

"What ails him?"

"That's more than the doctors can tell yet,"

added the woman. "They say it's very like the

cholera; and I suppose it's cholera-morbus. He

has been ailing for several days, and he didn't

take care of himself. But go in, Donald, and see

him while you may."

The young man entered the cottage. The doctors,

his mother and sister, were all doing what

they could for the sufferer, who was enduring,

with what patience he could, the most agonizing

pain. Donald went into the chamber where his

father lay writhing upon the bed. The physicians

were at work upon him; but he saw his son

as he entered the room and held out his hand to

him. The boy took it in his own. It was cold

and convulsed.

"I'm glad you've come, Donald," groaned he,

uttering the words with great difficulty. "Be a

good boy always, and take care of your mother

and sister."

"I will, father," sobbed Donald, pressing the

cold hand he held.

"I was afraid I might never see you again,"

gasped Mr. Ramsay.[67]

"O, don't give up, my man," said Dr. Wadman.

"You may be all right in a few hours."

The sick man said no more. He was in too

much pain to speak again, and Dr. Wadman sent

Donald to the kitchen for some hot water. When

he returned with it he was directed to go to the

apothecary's for an ounce of chloroform, which

the doctors were using internally and externally,

and had exhausted their supply. Donald ran all

the way as though the life of his father depended

upon his speed. He was absent only a few minutes,

but when he came back there was weeping

and wailing in the little cottage by the sea-side.

His father had breathed his last, even while the

doctors were hopefully working to save him.

"O, Donald, Donald!" cried Mrs. Ramsay, as

she threw her arms around his neck. "Your poor

father is gone!"

The boy could not speak; he could not even

weep, though his grief was not less intense than

that of his mother and sister. They groaned, and

sobbed, and sighed together, till kind neighbors

led them from the chamber of death, vainly endeavoring

to comfort them. It was hours before

they were even tolerably calm; but they could[68]

speak of nothing, think of nothing, but him who

was gone. The neighbors did all that it was necessary

to do, and spent the night with the

afflicted ones, who could not separate to seek

their beds. The rising sun of the Sabbath found

them still up, and still weeping—those who could

weep. It was a long, long Sunday to them, and

every moment of it was given to him who had

been a devoted husband and a tender father.

On Monday, all too soon, was the funeral; and

all that was mortal of Alexander Ramsay was laid

in the silent grave, never more to be looked upon

by those who had loved him, and whom he had

loved.

The little cottage was like a casket robbed of

its single jewel to those who were left. Earth

and life seemed like a terrible blank to them.

They could not accustom themselves to the empty

chair at the window where he sat when his day's

work was done; to the vacant place at the table,

where he had always invoked the blessing of God

on the frugal fare before them; and to the silent

and deserted shop on the other side of the street,

from which the noise of his hammer and the clip of

his adze had come to them. A week wore away[69]

and nothing was done but the most necessary

offices of the household. The neighbors came

frequently to beguile their grief, and the minister

made several visits, bearing to them the consolations

of the gospel, and the tender message of a

genuine sympathy.

But it is not for poor people long to waste

themselves in idle lamentations. The problem

of the future was forced upon Mrs. Ramsay for

solution. If they had been able only to live

comfortably on the earnings of the dead husband,

what should they do now when the strong arm that

delved for them was silent in the cold embrace of

death? They must all work now; but even then

the poor woman could hardly see how she could

keep her family together. Barbara was eighteen,

but she had never done anything except to assist

her mother, whose health was not very good,

about the house. She was a graduate of the High

School, and competent, so far as education was

concerned, to teach a school if she could obtain

a situation. Mrs. Ramsay might obtain work to

be done at home, but it was only a pittance she

could earn besides doing her housework. She

wished to have Donald finish his education at the[70]

High School, but she was afraid this was impossible.

Donald, still mourning for his father, who had

so constantly been his companion in the cottage

and in the shop, that he could not reconcile himself

to the loss, hardly thought of the future, till

his mother spoke to him about it. He had often,

since that bitter Saturday night, recalled the last

words his father had ever spoken to him, in which

he had told him to be a good boy always and take

care of his mother and sister; but they had not

much real significance to him till his mother

spoke to him. Then he understood them; then

he saw that his father was conscious of the near

approach of death, and had given his mother and

his sister into his keeping. Then, with the memory

of him who was gone lingering near and dear

in his heart, a mighty resolution was born in his

soul, though it did not at once take a practical

form.

"Don't worry about the future, mother," said

he, after he had listened to her rather hopeless

statement of her views.

"I don't worry about it, Donald, for while we

have our health and strength, we can work and[71]

make a living. I want to keep you in school till

the end of the year, but I—"

"Of course I can't go to school any more,

mother. I am ready to go to work," interposed

Donald.

"I know you are, my boy; but I want you to

finish your school course very much."

"I haven't thought a great deal about the matter

yet, mother, but I think I shall be able to do

what father told me."

"Your father did not expect you to take care

of us till you had grown up, I'm sure," added

Mrs. Ramsay, who had heard the dying injunction

of her husband to their son.

"I don't know that he did; but I shall do the

best I can."

"Poor father! He never thought of anything

but us," sighed Mrs. Ramsay; and her woman's

tears flowed freely again, so freely that there was

no power of utterance left to her.

Donald wept, too, as he thought of him who

was not only his father, but his loving companion

in study, in work, and in play. He left the

house and walked over to the shop. For the first

time since the sad event, he unlocked the door[72]

and entered. The tears trickled down his cheeks

as he glanced at the bench where his father had

done his last day's work. The planes and a few

other tools were neatly arranged upon it, and his

apron was spread over them. On the walls were

models of boats and yachts, and in one corner

were the "moulds." Donald seated himself on

the tool-chest, and looked around at every familiar

object in the shop. He was thinking of something,

but his thought had not yet taken definite

form. While he was considering the present and

the future, Samuel Rodman entered the shop.

"Do you suppose I can get the model of the

Sea Foam, Don John?" inquired he, after something

had been said about the deceased boat-builder.

"I think you can. The model and the drawings

are all here," replied Donald.

"We intend to build the Maud this season, and

I want her to be as near like the Sea Foam as possible."

"Who is going to build her?" asked Donald,

his interest suddenly kindled by the question.

"I don't know; we haven't spoken to any one

about it yet," replied Samuel. "There isn't any[73]body

in these parts that can build her as your

father would."

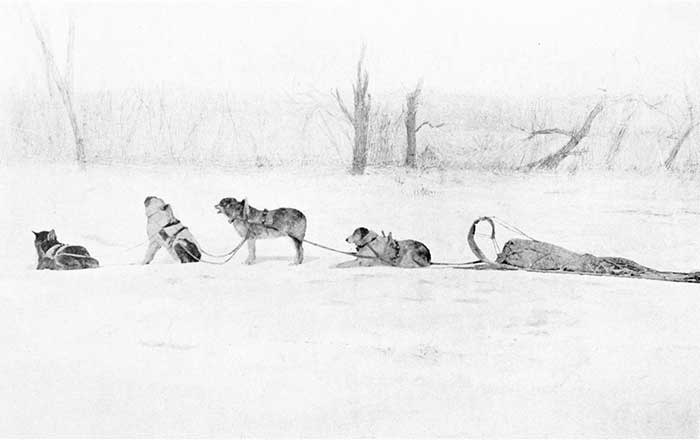

Don John wants a Job. Page 73.

"Sam, can't I do this job for you?" said

Donald.

"You?"

"Yes, I. You know I used to work with my

father, and I understand his way of doing things."

"Well, I hadn't thought that you could do it;

but I will talk with my father about it," answered

Samuel, who appeared to have some doubts

about the ability of his friend to do so large a

job.

"I don't mean to do it all myself, Sam. I will

hire one or two first-rate ship carpenters," added

Donald. "She shall be just like the Sea Foam,

except a little alteration, which my father explained

to me, in the bow and run."

"Do you think you could do the job, Don

John?" asked Samuel, with an incredulous smile.

"I know I could," said Donald, earnestly.

"If I had time enough I could build her all

alone."

"We want her as soon as we can get her."

"She shall be finished as quick as my father

could have done her."[74]

"I will see my father about it to-night, Don

John, and let you know to-morrow. I came

down to see about the model."

Samuel Rodman left the shop and walked down

the beach to the sail-boat in which he had come.