The Project Gutenberg eBook of On The Blockade

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: On The Blockade

Author: Oliver Optic

Illustrator: L. J. Bridgman

Release date: June 18, 2006 [eBook #18617]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Louise Hope, David Garcia, Juliet Sutherland

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Kentuckiana Digital

Library)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ON THE BLOCKADE ***

The Frontispiece ("Mulgrum and the Engineer") has been placed between

the Preface and the Table of Contents.

Invisible punctuation has been silently supplied. Other typographical

errors are marked in the text with mouse-hover popups.

THE BLUE AND THE GRAY—AFLOAT

Two colors cloth Emblematic Dies Illustrated

Price per volume $1.50

TAKEN BY THE ENEMY WITHIN THE ENEMY'S LINES ON THE BLOCKADE STAND BY THE UNION FIGHTING FOR THE RIGHT A VICTORIOUS UNION |

THE BLUE AND THE GRAY—ON LAND

Two colors cloth Emblematic Dies Illustrated

Price per volume $1.50

BROTHER AGAINST BROTHER IN THE SADDLE A LIEUTENANT AT EIGHTEEN ON THE STAFF AT THE FRONT AN UNDIVIDED UNION |

* * * Any Volume Sold

Separately * * *

LEE AND SHEPARD PUBLISHERS

BOSTON

The Blue and the Gray Series

ON THE BLOCKADE

BY

OLIVER OPTIC

AUTHOR OF "THE ARMY AND NAVY SERIES" "YOUNG AMERICA ABROAD" "THE

GREAT WESTERN SERIES" "THE WOODVILLE STORIES" "THE STARRY

FLAG SERIES" "THE BOAT-CLUB STORIES" "THE ONWARD

AND UPWARD SERIES" "THE YACHT-CLUB SERIES"

"THE LAKE SHORE SERIES" "THE RIVERDALE

STORIES" "THE BOAT-BUILDER SERIES"

"TAKEN BY THE ENEMY"

"WITHIN THE ENEMY'S

LINES" ETC.

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1890, by Lee and Shepard

All rights reserved.

On the Blockade.

TO MY SON-IN-LAW,

SOL SMITH RUSSELL,

of the united states of america,

though residing in minneapolis, minnesota,

who is always

"On the Blockade" against Melancholy, "The Blues,"

and all similar maladies,

This Volume

is affectionately dedicated.

PREFACE

"On the Blockade" is the third of

"The Blue and the Gray Series." Like the first and second volumes, its

incidents are dated back to the War of the Rebellion, and located in the

midst of its most stirring scenes on the Southern coast, where the naval

operations of the United States contributed their full share to the

final result.

The writer begs to remind his readers again that he has not felt

called upon to invest his story with the dignity of history, or in all

cases to mingle fiction with actual historic occurrences. He believes

that all the scenes of the story are not only possible, but probable,

and that just such events as he has narrated really and frequently

occurred in the days of the Rebellion.

The historian is forbidden to make his work more palatable or more

interesting by the intermixture of fiction with fact, while the

story-writer, though required to be reasonably consistent with the

spirit

8

and the truth of history, may wander from veritable details, and use his

imagination in the creation of incidents upon which the grand result is

reached. It would not be allowable to make the Rebellion a success, if

the writer so desired, even on the pages of romance; and it would not be

fair or just to ignore the bravery, the self-sacrifice, and the heroic

endurance of the Southern people in a cause they believed to be holy and

patriotic, as almost universally admitted at the present time, any more

than it would be to lose sight of the magnificent spirit, the heroism,

the courage, and the persistence, of the Northern people in

accomplishing what they believed then, and still believe, was a holy and

patriotic duty in the preservation of the Union.

Incidents not inconsistent with the final result, or with the spirit

of the people on either side in the great conflict are of comparatively

little consequence. That General Lee or General Grant turned this or

that corner in reaching Appomattox may be important, but the grand

historical tableau is the Christian hero, noble in the midst of defeat,

disaster, and ruin, formally rendering his sword to the impassible but

magnanimous conqueror

9

as the crowning event of a long and bloody war. The details are

historically important, though overshadowed by the mighty result of the

great conflict.

Many of the personages of the preceding volumes have been introduced

in the present one, and the central figure remains the same. The writer

is willing to admit that his hero is an ideal character, though his

lofty tone and patriotic spirit were fully paralleled by veritable

individuals during the war; and he is not prepared to apologize for the

abundant success which attended the career of Christy Passford. Those

who really struggled as earnestly and faithfully deserved his good

fortune, though they did not always obtain it.

Dorchester, Mass., April 24, 1890.

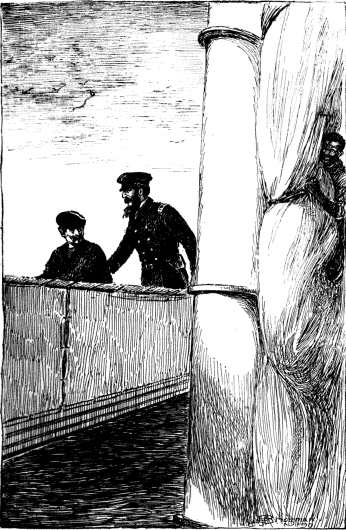

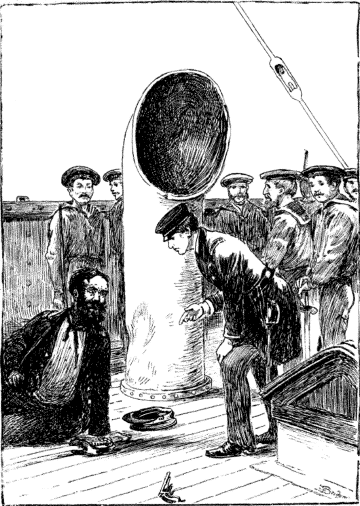

Mulgrum and the engineer

(Page 75)

CONTENTS

| page | |

CHAPTER I. | |

| The United States Steamer Bronx | 15 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| A Dinner for the Confederacy | 26 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| The Intruder at the Cabin Door | 37 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| A Deaf and Dumb Mystery | 48 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| A Confidential Steward | 59 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| A Mission up the Foremast | 70 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| An Interview on the Bridge | 81 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Important Information, if True | 92 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

12 A Volunteer Captain's Clerk | 103 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| The Unexpected Orders | 114 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| Another Reading of the Sealed Orders | 125 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| A Sail on the Starboard Bow | 136 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Steamer in the Fog | 147 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Confederate Steamer Scotian | 158 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Scotian becomes the Ocklockonee | 169 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Captain Passford's Final Orders | 180 |

CHAPTER XVII. | |

| A Couple of Astonished Conspirators | 191 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| A Triangular Action with Great Guns | 202 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

13 On the Deck of the Arran | 213 |

CHAPTER XX. | |

| The New Commander of the Bronx | 224 |

CHAPTER XXI. | |

| An Expedition in the Gulf | 235 |

CHAPTER XXII. | |

| A Night Expedition in the Boats | 246 |

CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Visit to a Shore Battery | 257 |

CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Captain Lonley of the Steamer Havana | 268 |

CHAPTER XXV. | |

| The New Engineer of the Prize Steamer | 279 |

CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| The Battle with the Soldiers | 290 |

CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| The Innocent Captain of the Garrison | 301 |

CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| The Bearer of Despatches | 312 |

CHAPTER XXIX. | |

14 The New Commander of the Vixen | 323 |

CHAPTER XXX. | |

| The Action with a Privateer Steamer | 334 |

CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| A Short Visit to Bonnydale | 345 |

ON THE BLOCKADE

CHAPTER I

THE UNITED STATES STEAMER BRONX

"She is a fine little steamer,

father, without the possibility of a doubt," said Lieutenant Passford,

who was seated at the table with his father in the captain's cabin on

board of the Bronx. "I don't feel quite at home here, and I don't quite

like the idea of being taken out of the Bellevite."

"You are not going to sea for the fun of it, my son," replied Captain

Passford. "You are not setting out on a yachting excursion, but on the

most serious business in the world."

"I know and feel all that, father, but I have spent so many pleasant

days, hours, weeks, and months on board of the Bellevite, that I am very

sorry to leave her," added Christy Passford, who had put on his new

uniform, which was that of

16

master in the United States Navy; and he was as becoming to the uniform

as the uniform was to him.

"You cannot well help having some regrets at leaving the Bellevite;

but you must remember that your life on board of her was mostly in the

capacity of a pleasure-seeker, though you made a good use of your time

and of your opportunities for improvement; and that is the reason why

you have made such remarkable progress in your present profession."

"I shall miss my friends on board of the Bellevite. I have sailed

with all her officers, and Paul Vapoor and I have been cronies for

years," continued Christy, with a shade of gloom on his bright face.

"You will probably see them occasionally, and if your life is spared

you may again find yourself an officer of the Bellevite. But I think you

have no occasion to indulge in any regrets," said Captain Passford,

imparting a cheerful expression to his dignified countenance. "Allow me

to call your attention to the fact that you are the commander of this

fine little steamer. Here you are in your own cabin, and you are still

nothing but a boy, hardly eighteen years old."

17

"If I have not earned my rank, it is not my fault that I have it,"

answered Christy, hardly knowing whether to be glad or sorry for his

rapid advancement. "I have never asked for anything; I did not ask or

expect to be promoted. I was satisfied with my rank as a

midshipman."

"I did not ask for your promotion, though I could probably have

procured for you the rank of master when you entered the navy. I do not

like to ask favors for a member of my own family. I have wished you to

feel that you were in the service of your country because it needs you,

and not for glory or profit."

"And I have tried to feel so, father."

"I think you have felt so, my son; and I am prouder of the fact that

you are a disinterested patriot than of the rank you have nobly and

bravely won," said Captain Passford, as he took some letters from his

pocket, from which he selected one bearing an English postage stamp. "I

have a letter from one of my agents in England, which, I think, contains

valuable information. I have called the attention of the government to

these employes of mine, and they will soon pass from my service to that

of the naval department.

18

The information sent me has sometimes been very important."

"I know that myself, for the information that came from that source

enabled the Bellevite to capture the Killbright," added Christy.

"The contents of the letter in my hand have been sent to the

Secretary of the Navy; but it will do no harm for you to possess the

information given to me," continued Captain Passford, as he opened the

letter. "But I see a man at work at the foot of the companion way, and I

don't care to post the whole ship's company on this subject."

"That is Pink Mulgrum," said Christy with a smile on his face. "He is

deaf and dumb, and he cannot make any use of what you say."

"Don't be sure of anything, Christy, except your religion and your

patriotism, in these times," added Captain Passford, as he rose and

closed the door of the cabin.

"I don't think there is much danger from a deaf mute, father," said

the young commander of the Bronx laughing.

"Perhaps not; but when you have war intelligence to communicate, it

is best to believe that every person has ears, and that every door has a

19

keyhole. I learn from this letter that the Scotian sailed from Glasgow,

and the Arran from Leith. The agent is of the opinion that both these

steamers are fitted out by the same owners, who have formed a company,

apparently to furnish the South with gunboats for its navy, as well as

with needed supplies. In his letter my correspondent gives me the reason

for this belief on his part."

"Does your agent give you any description of the vessels, father?"

asked Christy, his eyes sparkling with the interest he felt in the

information.

"Not a very full description, my son, for no strangers were allowed

on board of either of them, for very obvious reasons; but they are both

of less than five hundred tons burthen, are of precisely the same model

and build, evidently constructed in the same yard. Both had been

pleasure yachts, though owned by different gentlemen. Both sailed on the

same day, the Scotian from Greenock and the Arran from Leith,

March 3."

Christy opened his pocket diary, and put his finger on the date

mentioned, counting up the days that had elapsed from that time to the

present. Captain Passford could not help smiling at

20

the interest his son manifested in the intelligence he had brought to

him. The acting commander of the Bronx went over his calculation

again.

"It is fourteen days since these vessels sailed," said he, looking at

his father. "I doubt if your information will be of any value to me, for

I suppose the steamers were selected on account of their great speed, as

is the case with all blockade runners."

"Undoubtedly they were chosen for their speed, for a slow vessel does

not amount to much in this sort of service," replied Captain Passford.

"I received my letter day before yesterday, when the two vessels had

been out twelve days."

"If they are fast steamers, they ought to be approaching the Southern

coast by this time," suggested Christy.

"This is a windy month, and a vessel bound to the westward would

encounter strong westerly gales, so that she could hardly make a quick

passage. Then these steamers will almost certainly put in at Nassau or

the Bermudas, if not for coal and supplies, at least to obtain the

latest intelligence from the blockaded coast, and to pick up a pilot for

the port to which they are bound. The

21

agent thinks it is possible that the Scotian and Arran will meet some

vessel to the southward of the Isle of Wight that will put an armament

on board of them. He had written to another of my agents at Southampton

to look up this matter. It is a quick mail from the latter city to New

York, and I may get another letter on this subject before you sail,

Christy."

"My orders may come off to me to-day," added the acting commander. "I

am all ready to sail, and I am only waiting for them."

"If these two steamers sail in company, as they are likely to do if

they are about equal in speed, and if they take on board an armament, it

will hardly be prudent for you to meddle with them," said Captain

Passford with a smile, though he had as much confidence in the prudence

as in the bravery of his son.

"What shall I do, father, run away from them?" asked Christy, opening

his eyes very wide.

"Certainly, my son. There is as much patriotism in running away from

a superior force as there is in fighting an equal, for if the government

should lose your vessel and lose you and your ship's company, it would

be a disaster of more or less consequence to your country."

22

"I hardly think I shall fall in with the Scotian and the Arran, so I

will not consider the question of running away from them," said Christy

laughing.

"You have not received your orders yet, but they will probably

require you to report at once to the flag-officer in the Gulf, and

perhaps they will not permit you to look up blockade runners on the high

seas," suggested Captain Passford. "These vessels may be fully armed and

manned, in charge of Confederate naval officers; and doubtless they will

be as glad to pick up the Bronx as you would be to pick up the Scotian

or the Arran. You don't know yet whether they will come as simple

blockade runners, or as naval vessels flying the Confederate flag.

Whatever your orders, Christy, don't allow yourself to be carried away

by any Quixotic enthusiasm."

"I don't think I have any more than half as much audacity as Captain

Breaker said I had. As I look upon it, my first duty is to deliver my

ship over to the flag-officer in the Gulf; and I suppose I shall be

instructed to pick up a Confederate cruiser or a blockade runner, if one

should cross my course."

23

"Obey your orders, Christy, whatever they may be. Now, I should like to

look over the Bronx before I go on shore," said Captain Passford. "I

think you said she was of about two hundred tons."

"That was what they said down south; but she is about three hundred

tons," replied Christy, as he proceeded to show his father the cabin in

which the conversation had taken place.

The captain's cabin was in the stern of the vessel, according to the

orthodox rule in naval vessels. Of course it was small, though it seemed

large to Christy who had spent so much of his leisure time in the cabin

of the Florence, his sailboat on the Hudson. It was substantially fitted

up, with little superfluous ornamentation; but it was a complete parlor,

as a landsman would regard it. From it, on the port side opened the

captain's state room, which was quite ample for a vessel no larger than

the Bronx. Between it and the pantry on the starboard side, was a

gangway leading from the foot of the companion way, by which the

captain's cabin and the ward room were accessible from the quarter

deck.

Crossing the gangway at the foot of the steps,

24

Christy led the way into the ward room, where the principal officers

were accommodated. It contained four berths, with portières in

front of them, which could be drawn out so as to inclose each one in a

temporary state room. The forward berth on the starboard side was

occupied by the first lieutenant, and the after one by the second

lieutenant, according to the custom in the navy. On the port side, the

forward berth belonged to the chief engineer, and the after one to the

surgeon. Forward of this was the steerage, in which the boatswain,

gunner, carpenter, the assistant engineers, and the steward were

berthed. Each of these apartments was provided with a table upon which

the meals were served to the officers occupying it. The etiquette of a

man-of-war is even more exacting than that of a drawing room on

shore.

Captain Passford was then conducted to the deck where he found the

officers and seamen engaged in their various duties. Besides his son,

the former owner of the Bellevite was acquainted with only two persons

on board of the Bronx, Sampson, the engineer, and Flint, the acting

first lieutenant, both of whom had served on board of the steam yacht.

Christy's father gave them a

25

hearty greeting, and both were as glad to see him as he was to greet

them. Captain Passford then looked over the rest of the ship's company

with a deeper interest than he cared to manifest, for they were to some

extent bound up with the immediate future of his son. It was not such a

ship's company as that which manned the Bellevite, though composed of

much good material. The captain shook hands with his son, and went on

board of his boat. Two hours later he came on board again.

CHAPTER II

A DINNER FOR THE CONFEDERACY

Christy Passford was not a little surprised to see his father so soon

after his former visit, and he was confident that he had some good

reason for coming. He conducted him at once to his cabin, where Captain

Passford immediately seated himself at the table, and drew from his

pocket a telegram.

"I found this on my desk when I went to my office," said he, opening

a cable message, and placing it before Christy.

"'Mutton, three veal, four sea chickens,'" Christy read from the

paper placed before him, laughing all the time as he thought it was a

joke of some sort. "Signed 'Warnock.' It looks as though somebody was

going to have a dinner, father. Mutton, veal, and four sea chickens seem

to form the substantial of the feast, though I never ate any sea

chickens."

27

"Perhaps somebody will have a dinner, but I hope it will prove to be

indigestible to those for whom it is provided," added Captain Passford,

amused at the comments of his son.

"The message is signed by Warnock. I don't happen to have the

pleasure of his acquaintance, and I don't see why he has taken the

trouble to send you this bill of fare," chuckled the commander of the

Bronx.

"This bill of fare is of more importance to me, and especially to

you, than you seem to understand."

"It is all Greek to me; and I wonder why Warnock, whoever he may be,

has spent his money in sending you such a message, though I suppose you

know who is to eat this dinner."

"The expense of sending the cablegram is charged to me, though the

dinner is prepared for the Confederate States of America. Of course I

understand it, for if I could not, it would not have been sent to me,"

replied Captain Passford, assuming a very serious expression. "You know

Warnock, for he has often been at Bonnydale, though not under the name

he signs to this message. My three agents, one in the north, one in the

south,

28

and one in the west of England, have each an assumed name. They are

Otis, Barnes, and Wilson, and you know them all. They have been captains

or mates in my employ; and they know all about a vessel when they

see it."

"I know them all very well, and they are all good friends of mine,"

added Christy.

"Warnock is Captain Barnes, and this message comes from him. Captain

Otis signs himself Bixwell in his letters and cablegrams, and Mr.

Wilson, who was formerly mate of the Manhattan, uses the name of

Fleetley."

"I begin to see into your system, father; and I suppose the

government will carry out your plan."

"Very likely; for it would hardly be proper to send such information

as these men have to transmit in plain English, for there may be spies

or operators bribed by Confederate agents to suppress such matter."

"I see. I understand the system very well, father," said Christy.

"It is simple enough," added his father, as he took a paper from his

pocket-book.

"If you only understand it, it is simple enough."

29

"I can interpret the language of this message, and there is not another

person on the western continent that can do so. Now, look at the

cablegram, Christy," continued Captain Passford, as he opened the paper

he held in his hand. "What is the first word?"

"Mutton," replied the commander.

"Mutton means armed; that is to say the Scotian and the Arran took an

armament on board at some point south of England, as indicated by the

fact that the intelligence comes from Warnock. In about a week the mail

will bring me a letter from him in which he will explain how he obtained

this information."

"He must have chartered a steamer and cruised off the Isle of Wight

to pick it up," suggested Christy.

"He is instructed to do that when necessary. What is the next

word?"

"'Three,'" replied Christy.

"One means large, two medium, and three small," explained his father.

"Three what, does it say?"

"'Three veal.'"

"Veal means ship's company, or crew."

30

"Putting the pieces together, then, 'three veal' means that the Scotian

and the Arran have small crews," said Christy, intensely interested in

the information.

"Precisely so. Read the rest of the message," added Captain

Passford.

"'Four sea chickens,'" the commander read.

"'Four' means some, a few, no great number; in other words, rather

indefinite. Very likely Warnock could not obtain exact information. 'C'

stands for Confederate, and 'sea' is written instead of the letter.

'Chickens' means officers. 'Four sea chickens,' translated means 'some

Confederate officers.'"

Christy had written down on a piece of paper the solution of the

enigma, as interpreted by his father, though not the symbol words of the

cablegram. He continued to write for a little longer time, amplifying

and filling in the wanting parts of the message. Then he read what he

had written, as follows: "'The Scotian and the Arran are armed; there

are some Confederate officers on board, but their ship's companies are

small.' Is that it, father?"

"That is the substance of it," replied Captain

31

Passford, as he restored the key of the cipher to his pocket-book, and

rose from his seat. "Now you know all that can be known on this side of

the Atlantic in regard to the two steamers. The important information is

that they are armed, and even with small crews they may be able to sink

the Bronx, if you should happen to fall in with them, or if your orders

required you to be on the lookout for them. There is a knock at the

door."

Christy opened the door, and found a naval officer waiting to see

him. He handed him a formidable looking envelope, with a great seal upon

it. The young commander looked at its address, and saw that it came from

the Navy Department. With it was a letter, which he opened. It was an

order for the immediate sailing of the Bronx, the sealed orders to be

opened when she reached latitude 38° N. The messenger spoke

some pleasant words, and then took his leave. Christy returned to the

cabin, and showed the ponderous envelope to his father.

"Sealed orders, as I supposed you would have," said Captain

Passford.

"And this is my order to sail immediately on receipt of it," added

Christy.

32

"Then I must leave you, my son; and may the blessing of God go with you

wherever your duty calls you!" exclaimed the father, not a little shaken

by his paternal feelings. "Be brave, be watchful; but be prudent under

all circumstances. Bravery and Prudence ought to be twin sisters, and I

hope you will always have one of them on each side of you. I am not

afraid that you will be a poltroon, a coward; but I do fear that your

enthusiasm may carry you farther than you ought to go."

"I hope not, father; and your last words to me shall be remembered.

When I am about to engage in any important enterprise, I will recall

your admonition, and ask myself if I am heeding it."

"That satisfies me. I wish you had such a ship's company as we had on

board of the Bellevite; but you have a great deal of good material, and

I am confident that you will make the best use of it. Remember that you

are fighting for your country and the best government God ever gave to

the nations of the earth. Be brave, be prudent; but be a Christian, and

let no mean, cruel or unworthy action stain your record."

Captain Passford took the hand of his son, and though neither of them

wept, both of them were

33

under the influence of the strongest emotions. Christy accompanied his

father to the accommodation ladder, and shook hands with him again as he

embarked in his boat. His mother and his sister had been on board that

day, and the young commander had parted from them with quite as much

emotion as on the present occasion. The members of the family were

devotedly attached to each other, and in some respects the event seemed

like a funeral to all of them, and not less to Christy than to the

others, though he was entering upon a very exalted duty for one of his

years.

"Pass the word for Mr. Flint," said Christy, after he had watched the

receding boat that bore away his father for a few minutes.

"On duty, Captain Passford," said the first lieutenant, touching his

cap to him a few minutes later.

"Heave short the anchor, and make ready to get under way," added the

commander.

"Heave short, sir," replied Mr. Flint, as he touched his cap and

retired. "Pass the word for Mr. Giblock."

Mr. Giblock was the boatswain of the ship,

34

though he had only the rank of a boatswain's mate. He was an old sailor,

as salt as a barrel of pickled pork, and knew his duty from keel to

truck. In a few moments his pipe was heard, and the seamen began to walk

around the capstan.

"Cable up and down, sir," said the boatswain, reporting to the second

lieutenant on the forecastle.

Mr. Lillyworth was the acting second lieutenant, though he was not to

be attached to the Bronx after she reached her destination in the Gulf.

He repeated the report from the boatswain to the first lieutenant. The

steamer was rigged as a topsail schooner; but the wind was contrary, and

no sail was set before getting under way. The capstan was manned again,

and as soon as the report came from the second lieutenant that the

anchor was aweigh, the first lieutenant gave the order to strike one

bell, which meant that the steamer was to go "ahead slow."

The Bronx had actually started on her mission, and the heart of

Christy swelled in his bosom as he looked over the vessel, and realized

that he was in command, though not for more than a week or two. All the

courtesies and ceremonies were duly

35

attended to, and the steamer, as soon as the anchor had been catted and

fished, at the stroke of four bells, went ahead at full speed, though,

as the fires had been banked in the furnaces, the engine was not working

up to its capacity. In a couple of hours more she was outside of Sandy

Hook, and on the broad ocean. The ship's company had been drilled to

their duties, and everything worked to the entire satisfaction of the

young commander.

The wind was ahead and light. All hands had been stationed, and at

four in the afternoon, the first dog watch was on duty, and there was

not much that could be called work for any one to do. Mr. Lillyworth,

the second lieutenant, had the deck, and Christy had retired to his

cabin to think over the events of the day, especially those relating to

the Scotian and the Arran. He had not yet read his orders, and he could

not decide what he should do, even if he discovered the two steamers in

his track. He sat in his arm chair with the door of the cabin open, and

when he saw the first lieutenant on his way to the ward room, he called

him in.

"Well, Mr. Flint, what do you think of our crew?" asked the captain,

after he had seated his guest.

36

"I have hardly seen enough of the men to be able to form an opinion,"

replied Flint. "I am afraid we have some hard material on board, though

there are a good many first-class fellows among them."

"Of course we can not expect to get such a crew as we had in the

Bellevite. How do you like Mr. Lillyworth?" asked the commander, looking

sharply into the eye of his subordinate.

"I don't like him," replied Flint, bluntly. "You and I have been in

some tight places together, and it is best to speak our minds

squarely."

"That's right, Mr. Flint. We will talk of him another time. I have

another matter on my mind just now," added Christy.

He proceeded to tell the first lieutenant something about the two

steamers.

CHAPTER III

THE INTRUDER AT THE CABIN DOOR

Before he said anything about the Scotian and the Arran, Christy,

mindful of the injunction of his father, had closed the cabin door, the

portière remaining drawn as it was before. When he had taken this

precaution, he related some of the particulars which had been given to

him earlier in the day.

"It is hardly worth while to talk about the matter yet awhile," added

Christy. "I have my sealed orders, and I can not open the envelope until

we are in latitude 38, and that will be sometime to-morrow

forenoon."

"I don't think that Captain Folkner, who expected to be in command of

the Teaser, as she was called before we put our hands upon her,

overestimated her speed," replied Lieutenant Flint, consulting his

watch. "We are making fifteen knots an hour just now, and Mr. Sampson is

not

38

hurrying her. I have been watching her very closely since we left Sandy

Hook, and I really believe she will make eighteen knots with a little

crowding."

"What makes you think so, Flint?" asked Christy, much interested in

the statement of the first lieutenant.

"I suppose it is natural for a sailor to fall in love with his ship,

and that is my condition in regard to the Bronx," replied Flint, with a

smile which was intended as a mild apology for his weakness. "I used to

be in love with the coasting schooner I owned and commanded, and I

almost cried when I had to sell her."

"I don't think you need to be ashamed of this sentiment, or that an

inanimate structure should call it into being," said the young

commander. "I am sure I have not ceased to love the Bellevite; and in my

eyes she is handsomer than any young lady I ever saw. I have not been

able to transfer my affections to the Bronx as yet, and she will have to

do something very remarkable before I do so. But about the speed of our

ship?"

"I have noticed particularly how easily and

39

gracefully she makes her way through the water when she is going fifteen

knots. Why that is faster than most of the ocean passenger steamers

travel."

"Very true; but like many of these blockade runners and other vessels

which the Confederate government and rich men at the South have

purchased in the United Kingdom, she was doubtless built on the Clyde.

Not a few of them have been constructed for private yachts, and I have

no doubt, from what I have seen, that the Bronx is one of the number.

The Scotian and the Arran belonged to wealthy Britishers; and of course

they were built in the very best manner, and were intended to attain the

very highest rate of speed."

"I shall count on eighteen knots at least on the part of the Bronx

when the situation shall require her to do her best. By the way, Captain

Passford, don't you think that a rather queer name has been given to our

steamer? Bronx! I am willing to confess that I don't know what the word

means, or whether it is fish, flesh or fowl," continued Flint.

"It is not fish, flesh or fowl," replied Christy, laughing. "My

father suggested the name to

40

the Department, and it was adopted. He talked with me about a name, as

he thought I had some interest in her, for the reason that I had done

something in picking her up."

"Done something? I should say that you had done it all," added

Flint.

"I did my share. The vessels of the navy have generally been named

after a system, though it has often been varied. Besides the names of

states and cities, the names of rivers have been given to vessels. The

Bronx is the name of a small stream, hardly more than a brook, in West

Chester County, New York. When I was a small boy, my father had a

country place on its banks, and I did my first paddling in the water in

the Bronx. I liked the name, and my father recommended it."

"I don't object to the name, though somehow it makes me think of a

walnut cracked in your teeth when I hear it pronounced," added Flint.

"Now that I know what it is and what it means, I shall take more kindly

to it, though I am afraid we shall get to calling her the Bronxy before

we have done with her, especially if she gets to be a pet, for the name

seems to need another syllable."

41

"Young men fall in love with girls without regard to their names."

"That's so. A friend of mine in our town in Maine fell in love with a

young lady by the name of Leatherbee; but she was a very pretty girl and

her name was all the objection I had to her," said Flint, chuckling.

"But that was an objection which your friend evidently intended to

remove at no very distant day," suggested Christy.

"Very true; and he did remove it some years ago. What was that

noise?" asked the first lieutenant, suddenly rising from his seat.

Christy heard the sounds at the same moment. He and his companion in

the cabin had been talking about the Scotian and the Arran, and what his

father had said to him about prudence in speaking of his movements came

to his mind. The noise was continued, and he hastened to the door of his

state room, and threw it open. In the room he found Dave hard at work on

the furniture; he had taken out the berth sack, and was brushing out the

inside of the berth. The noise had been made by the shaking of the slats

on which the mattress rested. Davis Talbot, the cabin steward

42

of the Bronx, had been captured in the vessel when she was run out of

Pensacola Bay some months before. As he was a very intelligent colored

man, or rather mulatto, though they were all the same at the South, the

young commander had selected him for his present service; and he never

had occasion to regret the choice. Dave had passed his time since the

Teaser arrived at New York at Bonnydale, and he had become a great

favorite, not only with Christy, but with all the members of the

family.

"What are you about, Dave?" demanded Christy, not a little astonished

to find the steward in his room.

"I am putting the room in order for the captain, sir," replied Dave

with a cheerful smile, such as he always wore in the presence of his

superiors. "I found something in this berth I did not like to see about

a bed in which a gentleman is to sleep, and I have been through it with

poison and a feather; and I will give you the whole southern Confederacy

if you find a single redback in the berth after this."

"I am very glad you have attended to this matter at once, Dave."

43

"Yes, sir; Captain Folkner never let me attend to it properly, for he

was afraid I would read some of his papers on the desk. He was willing

to sleep six in a bed with redbacks," chuckled Dave.

"Well, I am not, or even two in a bed with such companions. How long

have you been in my room, Dave?" added Christy.

"More than two hours, I think; and I have been mighty

busy too."

"Did you hear me when I came into the cabin?"

"No, sir, I did not; but I heard you talking with somebody a

while ago."

"What did I say to the other person?"

"I don't know, sir; I could not make out a word, and I didn't stop in

my work to listen. I have been very busy, Captain Passford," answered

Dave, beginning to think he had been doing something that was not

altogether regular.

"Don't you know what we were talking about, Dave?"

"No, sir; I did not make out a single word you said," protested the

steward, really troubled to find that he had done something wrong,

though he had not the least idea what it was. "I did not mean to do

anything out of the way, Captain Passford."

44

"I have no fault to find this time, Dave."

"I should hope not, sir," added Dave, looking as solemn as a sleepy

owl. "I would jump overboard before I would offend you, Massa

Christy."

"You need not jump overboard just yet," replied the captain, with a

pleasant smile, intended to remove the fears of the steward. "But I want

to make a new rule for you, Dave."

"Thank you, sir; if you sit up nights to make rules for me, I will

obey all of them; and I would give you the whole State of Florida before

I would break one of them on purpose, Massa Christy."

"Massa Christy!" exclaimed the captain, laughing.

"Massa Captain Passford!" shouted Dave, hastening to correct his

over-familiarity.

"I don't object to your calling me Christy when we are alone, for I

look upon you as my friend, and I have tried to treat you as a

gentleman, though you are a subordinate. But are you going to be a

nigger again, and call white men 'Massa?' I told you not to use that

word."

"I done forget it when I got excited because I was afraid I had

offended you," pleaded the steward.

45

"Your education is vastly superior to most people of your class, and you

should not belittle yourself. This is my cabin; and I shall sometimes

have occasion to talk confidentially with my officers. Do you understand

what I mean, Dave?"

"Perfectly, Captain Passford: I know what it is to talk confidently

and what it is to talk confidentially, and you do both, sir," replied

the steward.

"But I am sometimes more confidential than confident. Now you must do

all your work in my state room when I am not in the cabin, and this is

the new rule," said Christy, as he went out of the room. "I know that I

can trust you, Dave; but when I tell a secret I want to know to how many

persons I am telling it. You may finish your work now;" and he closed

the door.

Christy could not have explained why he did so if it had been

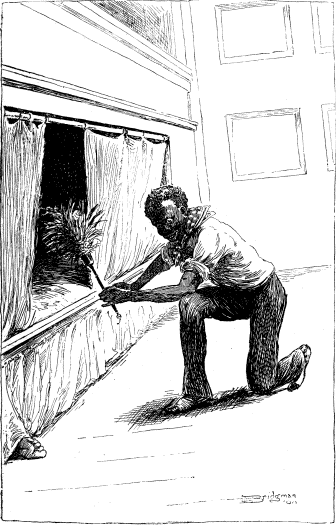

required of him, but he went directly to the door leading out into the

companion way, and suddenly threw it wide open, drawing the

portière aside at the same time. Not a little to his surprise,

for he had not expected it, he found a man there; and the intruder was

down

46

on his knees, as if in position to place his ear at the keyhole. This

time the young commander was indignant, and without stopping to consider

as long as the precepts of his father required, he seized the man by the

collar, and dragged him into the cabin.

"What are you doing there?" demanded Christy in the heat of his

indignation.

The intruder, who was a rather stout man, began to shake his head

with all his might, and to put the fore finger of his right hand on his

mouth and one of his ears. He was big enough to have given the young

commander a deal of trouble if he had chosen to resist the force used

upon him; but he appeared to be tame and submissive. He did not speak,

but he seemed to be exerting himself to the utmost to make himself

understood. Flint had resumed his seat at the table, facing the door,

and in spite of himself, apparently, he began to laugh.

"That is Pink Mulgrum, Captain Passford," said he, evidently to

prevent his superior from misinterpreting the lightness of his conduct.

"As you are aware, he is deaf and dumb."

Mulgrum at the captain's door.

"I see who he is now," replied Christy, who

47

had just identified the man. "He may be deaf and dumb, but he seems to

have a great deal of business at the door of my cabin."

"I have no doubt he is as deaf as the keel of the ship, and I have

not yet heard him speak a word," added the first lieutenant. "But he is

a stout fellow, very patriotic, and willing to work."

"All that may be, but I have found him once before hanging around

that door to-day."

At this moment Mulgrum took from his pocket a tablet of paper and a

pencil, and wrote upon it, "I am a deaf mute, and I don't know what you

are talking about." Christy read it, and then wrote, "What were you

doing at the door?" He replied that he had been sent by Mr. Lillyworth

to clean the brasses on the door. He was then dismissed.

CHAPTER IV

A DEAF AND DUMB MYSTERY

As he dismissed Mulgrum, Christy tore off the leaf from the tablet on

which both of them had written before he handed it back to the owner.

For a few moments, he said nothing, and had his attention fixed on the

paper in his hand, which he seemed to be studying for some reason of

his own.

"That man writes a very good hand for one in his position," said he,

looking at the first lieutenant.

"I had noticed that before," replied Flint, as the commander handed

him the paper, which he looked over with interest. "I had some talk with

him on his tablet the day he came on board. He strikes me as a very

intelligent and well-educated man."

"Was he born a deaf mute?" asked Christy.

"I did not think to ask him that question; but I judged from the

language he used and his rapid

49

writing that he was well educated. There is character in his handwriting

too; and that is hardly to be expected from a deaf mute," replied

Flint.

"Being a deaf mute, he can not have been shipped as a seaman, or even

as an ordinary steward," suggested the captain.

"Of course not; he was employed as a sort of scullion to be worked

wherever he could make himself useful. Mr. Nawood engaged him on the

recommendation of Mr. Lillyworth," added Flint, with something like a

frown on his brow, as though he had just sounded a new idea.

"Have you asked Mr. Lillyworth anything about him?"

"I have not; for somehow Mr. Lillyworth and I don't seem to be very

affectionate towards each other, though we get along very well together.

But Mulgrum wrote out for me that he was born in Cherryfield, Maine, and

obtained his education as a deaf mute in Hartford. I learned the deaf

and dumb alphabet when I was a schoolmaster, as a pastime, and I had

some practice with it in the house where I boarded."

"Then you can talk in that way with Mulgrum."

50

"Not a bit of it; he knows nothing at all about the deaf and dumb

alphabet, and could not spell out a single word I gave him."

"That is very odd," added the captain musing.

"So I thought; but he explained it by saying that at the school they

were changing this method of communication for that of actually speaking

and understanding what was said by observing the vocal organs. He had

not remained long enough to master this method; in fact he had done all

his talking with his tablets."

"It is a little strange that he should not have learned either method

of communication."

"I thought so myself, and said as much to him; but he told me that he

had inherited considerable property at the death of his father, and he

was not inclined to learn new tricks," said Flint. "He is intensely

patriotic, and said that he was willing to give himself and all his

property for the salvation of his country. He had endeavored to obtain a

position as captain's clerk, or something of that sort, in the navy; but

failing of this, he had been willing to go to the war as a scullion. He

says he shall fight, whatever his situation, when he has the

opportunity; and that is all I know about him."

51

Christy looked on the floor, and seemed to be considering the facts he

had just learned. He had twice discovered Mulgrum at the door of his

cabin, though his presence there had been satisfactorily explained; or

at least a reason had been given. This man had been brought on board by

the influence of Mr. Lillyworth, who had been ordered to the Gulf for

duty, and was on board as a substitute for Mr. Flint, who was acting in

Christy's place, as the latter was in that of Mr. Blowitt, who outranked

them all. Flint had not been favorably impressed with the acting second

lieutenant, and he had not hesitated to speak his mind in regard to him

to the captain. Though Christy had been more reserved in speech, he had

the feeling that Mr. Lillyworth must establish a reputation for

patriotism and fidelity to the government before he could trust him as

he did the first lieutenant, though he was determined to manifest

nothing like suspicion in regard to him.

At this stage of the war, that is to say in the earlier years of it,

the government was obliged to accept such men as it could obtain for

officers, for the number in demand greatly exceeded the supply of

regularly educated naval officers. There were

52

a great many applicants for positions, and candidates were examined in

regard to their professional qualifications rather than their motives

for entering the service. If a man desired to enter the army or the

navy, the simple wish was regarded as a sufficient guaranty of his

patriotism, especially in connection with his oath of allegiance. With

the deaf mute's leaf in his hand Christy was thinking over this matter

of the motives of officers. He was not satisfied in regard to either

Lillyworth or Mulgrum, and besides the regular quota of officers and

seamen permanently attached to the Bronx, there were eighteen seamen and

petty officers berthed forward, who were really passengers, though they

were doing duty.

"Where did you say this man Mulgrum was born, Mr. Flint?" asked the

captain, after he had mused for quite a time.

"In Cherryfield, Maine," replied the first lieutenant; and he could

not help feeling that the commander had not been silent so long for

nothing.

"You are a Maine man, Flint: were you ever in this town?"

"I have been; I taught school there for six

53

months; and it was the last place I filled before I went to sea."

"I am glad to hear it, for it will save me from looking any further

for the man I want just now. If this deaf mute was born and brought up

in Cherryfield, he must know something about the place," added Christy

as he touched a bell on his table, to which Dave instantly

responded.

"Do you know Mulgrum, Dave?" asked the captain.

"No, sir; never heard of him before," replied the steward.

"You don't know him! The man who has been cleaning the brass work on

the doors?" exclaimed Christy.

"Oh! Pink, we all call him," said the steward.

"His name is Pinkney Mulgrum," Flint explained.

"Yes, sir; I know him, though we never had any long talks together,"

added Dave with a rich smile on his face.

"Go on deck, and tell Mulgrum to come into my cabin," said

Christy.

"If I tell him that, he won't hear me," suggested Dave.

54

"Show him this paper," interposed the first lieutenant, handing him a

card on which he had written the order.

Dave left the cabin to deliver the message, and the captain

immediately instructed Flint to question the man in regard to the

localities and other matters in Cherryfield, suggesting that he should

conduct his examination so as not to excite any suspicion. Pink Mulgrum

appeared promptly, and was placed at the table where both of the

officers could observe his expression. Then Flint began to write on a

sheet of paper, and passed his first question to the man. It was: "Don't

you remember me?" Mulgrum wrote that he did not. Then the inquisitor

asked when he had left Cherryfield to attend the school at Hartford; and

the date he gave placed him there at the very time when Flint had been

the master of the school for four months. On the question of locality,

he could place the church, the schoolhouse and the hotel; and he seemed

to have no further knowledge of the town. When asked where his father

lived, he described a white house next to the church; but Flint knew

that this had been owned and occupied by the minister for many

years.

55

"This man is a humbug," was the next sentence the first lieutenant

wrote, but he passed it to the captain. Christy wrote under it: "Tell

him that we are perfectly satisfied with his replies, and thank him for

his attendance;" which was done at once, and the captain smiled upon him

as though he had conducted himself with distinguished ability.

"Mulgrum has been in Cherryfield; but he could not have remained

there more than a day or two," said Flint, when the door had closed

behind the deaf mute.

The captain made a gesture to impose silence upon his companion.

"Mulgrum is all right in every respect," said he in a loud tone, so

that if the subject of the examination had stopped at the keyhole of the

door, he would not be made any the wiser for what he heard there.

"He knows Cherryfield as well as he knows the deck of the Bronx, and

as you say, Captain Passford, he is all right in every respect," added

the first lieutenant in the same loud tone. "Mulgrum is a well educated

man, captain, and you will have a great deal of writing to do: I suggest

that you

56

bring him into your cabin, and make him your clerk."

"That is a capital idea, Mr. Flint, and I shall consider it,"

returned the commander, making sure that the man at the door should hear

him, if Mulgrum lingered there. "I have a number of letters sent over

from England relating to blockade runners that I wish to have copied for

the use of any naval officers with whom I may fall in; and I have not

the time to do it myself."

"Mulgrum writes a very handsome hand, and no one could do the work

any better than he."

Christy thought enough had been said to satisfy the curiosity of

Mulgrum if he was still active in seeking information, and both of the

officers were silent. The captain had enough to think of to last him a

long while. The result of the inquiry into the auditory and vocal powers

of the scullion, as Flint called him, had convinced him that the deaf

mute was a fraud. He had no doubt that he could both speak and hear as

well as the rest of the ship's company. But the puzzling question was in

relation to the reason why he pretended to be deaf and dumb. If he was

desirous of serving his country in the navy, and especially in the

57

Bronx, it was not necessary to pretend to be deaf and dumb in order to

obtain a fighting berth on board of her. It looked like a first class

mystery to the young commander, but he was satisfied that the presence

of Mulgrum meant mischief. He could not determine at once what it was

best to do to solve the mystery; but he decided that the most extreme

watchfulness was required of him and his first lieutenant. This was all

he could do, and he touched his bell again.

"Dave," said he when the cabin steward presented himself before him,

"go on deck and ask Mr. Lillyworth to report to me the log and the

weather."

"The log and the weather, sir," replied Dave, as he hastened out of

the cabin.

Christy watched him closely as he went out at the door, and he was

satisfied that Mulgrum was not in the passage, if he had stopped there

at all. His present purpose was to disarm all the suspicions of the

subject of the mystery, but he would have been glad to know whether or

not the man had lingered at the door to hear what was said in regard to

him. He was not anxious in regard to the weather, or even the log, and

he sent Dave on

58

his errand in order to make sure that Mulgrum was not still doing duty

as a listener.

"Wind south south west, log last time fifteen knots and a half,"

reported Dave, as he came in after knocking at the door.

"I can not imagine why that man pretended to be deaf and dumb in

order to get a position on board of the Bronx. He is plainly a fraud,"

said the captain when Dave had gone back to his work in the state

room.

"I don't believe he pretended to be a deaf mute in order to get a

place on board, for that would ordinarily be enough to prevent him from

getting it. I should put it that he had obtained his place in spite of

being deaf and dumb. But the mystery exists just the same."

The captain went on deck, and the first lieutenant to the ward

room.

CHAPTER V

A CONFIDENTIAL STEWARD

The wind still came from the southward, and it was very light. The

sea was comparatively smooth, and the Bronx continued on her course. At

the last bi-hourly heaving of the log, she was making sixteen knots an

hour. The captain went into the engine room, where he found Mr. Gawl,

one of the chief's two assistants, on duty. This officer informed him

that no effort had been made to increase the speed of the steamer, and

that she was under no strain whatever. The engine had been thoroughly

overhauled, as well as every other part of the vessel, and every

improvement that talent and experience suggested had been made. It now

appeared that the engine had been greatly benefited by whatever changes

had been made. These improvements had been explained to the commander by

Mr. Sampson the day before; but Christy had not given much attention

60

to the matter, for he preferred to let the speed of the vessel speak for

itself; and this was what it appeared to be doing at the present

time.

Christy walked the deck for some time, observing everything that

presented itself, and taking especial notice of the working of the

vessel. Though he made no claims to any superior skill, he was really an

expert, and the many days and months he had passed in the companionship

of Paul Vapoor in studying the movements of engines and hulls had made

him wiser and more skilful than it had even been suspected that he was.

He was fully competent for the position he was temporarily filling; but

he had made himself so by years of study and practice.

Christy had not yet obtained all the experience he required as a

naval officer, and he was fully aware that this was what he needed to

enable him to discharge his duty in the best manner. He was in command

of a small steamer, a position of responsibility which he had not

coveted in this early stage of his career, though it was only for a week

or less, as the present speed of the Bronx indicated. He had ambition

enough to hope that he should be able to distinguish himself in this

61

brief period, for it might be years before he again obtained such an

opportunity. His youth was against him, and he was aware that he had

been selected to take the steamer to the Gulf because there was a

scarcity of officers of the proper grade, and his rank gave him the

position.

The motion of the Bronx exactly suited him, and he judged that in a

heavy sea she would behave very well. He had made one voyage in her from

the Gulf to New York, and the steamer had done very well, though she had

been greatly improved at the navy yard. Certainly her motion was better,

and the connection between the engine and the inert material of which

the steamer was constructed, seemed to be made without any straining or

jerking. There was very little shaking and trembling as the powerful

machinery drove her ahead over the quiet sea. There had been no very

severe weather during his first cruise in the Bronx, and she had not

been tested in a storm under his management, though she had doubtless

encountered severe gales in crossing the Atlantic in a breezy season of

the year.

While Christy was planking the deck, four bells were struck on the

ship's great bell on the

62

top-gallant forecastle. It was the beginning of the second dog watch, or

six o'clock in the afternoon, and the watch which had been on duty since

four o'clock was relieved. Mr. Flint ascended the bridge, and took the

place of Mr. Lillyworth, the second lieutenant. Under this bridge was

the pilot-house, and in spite of her small size, the steamer was steered

by steam. The ship had been at sea but a few hours, and the crew were

not inclined to leave the deck. The number of men on board was nearly

doubled by the addition of those sent down to fill vacancies in other

vessels on the blockade. Christy went on the bridge soon after, more to

take a survey inboard than for any other purpose.

Mr. Lillyworth had gone aft, but when he met Mulgrum coming up from

the galley, he stopped and looked around him. With the exception of

himself nearly the whole ship's company were forward. The commander

watched him with interest when he stopped in the vicinity of the deaf

mute, who also halted in the presence of the second lieutenant. Then

they walked together towards the companion way, and disappeared behind

the mainmast. Christy had not before

63

noticed any intercourse between the lieutenant and the scullion, though

he thought it a little odd that the officer should set the man at work

cleaning the brasses about the door of the captain's cabin, a matter

that belonged to the steward's department. He had learned from Flint

that Mulgrum had been recommended to the chief steward by Lillyworth, so

that it was evident enough that they had been acquainted before either

of them came on board. But he could not see them behind the mast, and he

desired very much to know what they were doing.

Flint had taken his supper before he went on duty on the bridge, and

the table was waiting for the other ward room officers who had just been

relieved. It was time for Lillyworth to go to the meal, but he did not

go, and he seemed to be otherwise engaged. After a while, Christy looked

at his watch, and found that a quarter of an hour had elapsed since the

second lieutenant had left the bridge, and he had spent nearly all this

time abaft the mainmast with the scullion. The commander had become

absolutely absorbed in his efforts to fathom the deaf and dumb mystery,

and fortunately there was nothing else to occupy his

64

attention, for Flint had drilled the crew, including the men for other

vessels, and had billeted and stationed them during the several days he

had been on board. Everything was working as though the Bronx had been

at sea a month instead of less than half a day.

Christy was exceedingly anxious to ascertain what, if anything, was

passing between Lillyworth and Mulgrum; but he could see no way to

obtain any information on the subject. He had no doubt he was watched as

closely as he was watching the second lieutenant. If he went aft, that

would at once end the conference, if one was in progress. He could not

call upon a seaman to report on such a delicate question without

betraying himself, and he had not yet learned whom to trust in such a

matter, and it was hardly proper to call upon a foremast hand to watch

one of his officers.

The only person on board besides the first lieutenant in whom he felt

that he could repose entire confidence was Dave. He knew him thoroughly,

and his color was almost enough to guarantee his loyalty to the country

and his officers, and especially to himself, for the steward possessed a

rather extravagant admiration for the one who

65

had "brought him out of bondage," as he expressed it, and had treated

him like a gentleman from first to last. He could trust Dave even on the

most delicate mission; but Dave was attending to the table in the ward

room, and he did not care to call him from his duty.

At the end of another five minutes, Christy saw Mulgrum come from

abaft the mainmast, and descend the ladder to the galley. He saw no more

of Lillyworth, and he concluded that, keeping himself in the shadow of

the mast, he had gone below. He remained on the bridge a while longer

considering what he should do. He said nothing to Flint, for he did not

like to take up the attention of any officer on duty. The commander

thought that Dave could render him the assistance he required better

than any other person on board, for being only a steward and a colored

man at that, less notice would be taken of him than of one in a higher

position. He was about to descend from the bridge when Flint spoke to

him in regard to the weather, though he could have guessed to a point

what the captain was thinking about, perhaps because the same subject

occupied his own thoughts.

66

"I think we shall have a change of weather before morning, Captain

Passford. The wind is drawing a little more to the southward, and we are

likely to have wind and rain," said the first lieutenant.

"Wind and rain will not trouble us, and I am more afraid that we

shall be bothered with fog on this cruise," added Christy as he

descended the ladder to the main deck.

He walked about the deck for a few minutes, observing the various

occupations of the men, who were generally engaged in amusing

themselves, or in "reeling off sea yarns." Then he went below. At the

foot of the stairs in the companion way, the door of the ward room was

open, and he saw that Lillyworth was seated at the table. He sat at the

foot of it, the head being the place of the first lieutenant, and the

captain could see only his back. He was slightly bald at the apex of his

head, for he was an older man than either the captain or the first

lieutenant, but inferior to them in rank, though all of them were

masters, and seniority depended upon the date of the commissions; and

even a single day settled the degree in these days of multiplied

appointments. Christy

67

went into his cabin, where the table was set for his own supper.

The commander looked at his barometer, and his reading of it assured

him that Flint was correct in regard to his prognostics of the weather.

But the young officer had faced the winter gales of the Atlantic, and

the approach of any ordinary storm did not disturb him in the least

degree. On the contrary he rather liked a lively sea, for it was less

monotonous than a calm. He did not brood over a storm, therefore, but

continued to consider the subject which had so deeply interested him

since he discovered Mulgrum on his knees at the door, with a rag and a

saucer of rottenstone in his hands. He had a curiosity to examine the

brass knob of his door at that moment, and it did not appear to have

been very severely rubbed.

"Quarter of seven, sir," said Dave, presenting himself at the door

while Christy was still musing over the incidents already detailed.

"All right, Dave; I will have my supper now," replied Christy,

indifferently, for though he was generally blessed with a good appetite

the mystery was too absorbing to permit the necessary duty of eating to

drive it out of his mind.

68

Dave retired, and soon brought in a tray from the galley, the dishes

from which he arranged on the table. It was an excellent supper, though

he had not given any especial orders in regard to its preparation. He

seated himself and began to eat in a rather mechanical manner, and no

one who saw him would have mistaken him for an epicure. Dave stationed

himself in front of the commander, so that he was between the table and

the door. He watched Christy, keeping his eyes fixed on him without

intermitting his gaze for a single instant. Once in a while he tendered

a dish to him at the table, but there was but one object in existence

for Christy at that moment.

"Dave," said the captain, after he had disposed of a portion of his

supper.

"Here, sir, on duty," replied the steward.

"Open the door behind you, quick!"

Dave obeyed instantly, and threw the door back so that it was wide

open, though he seemed to be amazed at the strangeness of the order.

"All right, Dave; close it," added Christy, when he saw there was no

one in the passage; and he concluded that Mulgrum was not likely to be

practising his vocation when there was no one in the cabin but himself

and the steward.

69

Dave obeyed the order like a machine, and then renewed his gaze at the

commander.

"Are you a Freemason, Dave?" asked Christy.

"No, sir," replied the steward with a magnificent smile.

"A Knight of Pythias, of Pythagoras, or anything of that sort?"

"No, sir; nothing of the sort."

"Then you can't keep a secret?"

"Yes, sir, I can. If I have a secret to keep, I will give the whole

Alabama River to any one that can get it out of me."

Christy felt sure of his man without this protestation.

CHAPTER VI

A MISSION UP THE FOREMAST

Christy spent some time in delivering a lecture on naval etiquette to

his single auditor. Probably he was not the highest authority on the

subject of his discourse; but he was sufficiently learned to meet the

requirements of the present occasion.

"You say you can keep a secret, Dave?" continued the commander.

"I don't take any secrets to keep from everybody, Captain Passford;

and I don't much like to carry them about with me," replied the steward,

looking a little more grave than usual, though he still wore a cheerful

smile.

"Then you don't wish me to confide a secret to you?"

"I don't say that, Captain Passford. I don't want any man's secrets,

and I don't run after them, except for the good of the service. I was a

slave once, but I know what I am working for

71

now. If you have a secret I ought to know, Captain Passford, I will take

it in and bury it away down at the bottom of my bosom; and I will give

the whole state of Louisiana to any one that will dig it out

of me."

"That's enough, Dave; and I am willing to trust you without any oath

on the Bible, and without even a Quaker's affirmation. I believe you

will be prudent, discreet, and silent for my sake."

"Certainly I will be all that, Captain Passford, for I think you are

a bigger man than Jeff Davis," protested Dave.

"That is because you do not know the President of the Confederate

States, and you do know me; but Mr. Davis is a man of transcendent

ability, and I am only sorry that he is engaged in a bad cause, though

he believes with all his heart and soul that it is a good cause."

"He never treated me like a gentleman, as you have, sir."

"And he never treated you unkindly, I am very sure."

"He never treated me any way, for I never saw him; and I would not

walk a hundred miles barefooted

72

to see him, either. I am no gentleman or anything of that sort,

Massa— Captain Passford, but if I ever go back on you by the

breadth of a hair, then the Alabama River will run up hill."

"I am satisfied with you, Dave; and here is my hand," added Christy,

extending it to the steward, who shook it warmly, displaying a good deal

of emotion as he did so. "Now, Dave, you know Mulgrum, or Pink, as you

call him?"

"Well, sir, I know him as I do the rest of the people on board; but

we are not sworn friends yet," replied Dave, rather puzzled to know what

duty was required of him in connection with the scullion.

"You know him; that is enough. What do you think of him?"

"I haven't had any long talks with him, sir, and I don't know what to

think of him."

"You know that he is dumb?"

"I expect he is, sir; but he never said anything to me about it,"

replied Dave. "He never told me he couldn't speak, and I never heard him

speak to any one on board."

"Did you ever speak to him?"

"Yes, sir; I spoke to him when he first came

73

on board; but he didn't answer me, or take any notice of me when I spoke

to him, and I got tired of it."

"Open that door quickly, Dave," said the captain suddenly.

The steward promptly obeyed the order, and Christy saw that there was

no one in the passage. He told his companion to close the door, and Dave

was puzzled to know what this movement could mean.

"I beg your pardon, Captain Passford, and I have no right to ask any

question; but I should like to know why you make me open that door two

or three times for nothing," said Dave, in the humblest of tones.

"I told you to open it so that I could see if there was anybody at

the door. This is my secret, Dave. I have twice found Mulgrum at that

door while I was talking to the first lieutenant. He pretended to be

cleaning the brass work."

"What was he there for? When a man is as deaf as the foremast of the

ship what would he be doing at the door?"

"He was down on his knees, and his ear was not a great way from the

keyhole of the door."

74

"But he could not hear anything."

"I don't know: that is what I want to find out. The mission I have

for you, Dave, is to watch Mulgrum. In a word, I have my doubts in

regard to his deafness and his dumbness."

"You don't believe he is deaf and dumb, Captain Passford!" exclaimed

the steward, opening his eyes very wide, and looking as though an

earthquake had just shaken him up.

"I don't say that, my man. I am in doubt. He may be a deaf mute, as

he represents himself to be. I wish you to ascertain whether or not he

can speak and hear. You are a shrewd fellow, Dave, I discovered some

time ago; in fact the first time I ever saw you. You may do this job in

any manner you please; but remember that your mission is my secret, and

you must not betray it to Mulgrum, or to any other person."

"Be sure I won't do that, Captain Passford."

"If you obtain any satisfactory information, convey it to me

immediately. You must be very careful not to let any one suspect that

you are watching him, and least of all to let Mulgrum know it. Do you

understand me perfectly, Dave?"

75

"Yes, sir; perfectly. Nobody takes any notice of me but you, and it

won't be a hard job. I think I can manage it without any trouble. I am

nothing but a nigger, and of no account."

"I have chosen you for this mission because you can do it better than

any other person, Dave. Don't call yourself a nigger; I don't like the

word, and you are ninety degrees in the shade above the lower class of

negroes in the South."

"Thank you, sir," replied the steward with an expansive smile.

"There is one thing I wish you to understand particularly, Dave. I

have not set you to watch any officer of the ship," said Christy

impressively.

"No, sir; I reckon Pink Mulgrum is not an officer any more than

I am."

"But you may discover, if you find that Mulgrum can speak and hear,

that he is talking to an officer," added the captain in a low tone.

"What officer, Captain Passford?" asked the steward, opening his eyes

to their utmost capacity, and looking as bewildered as an owl in the

gaslight.

"I repeat that I do not set you to watch an officer; and I leave it

to you to ascertain with

76

whom Mulgrum has any talk, if with any one. Now I warn you that, if you

accomplish anything in this mission, you will do it at night and not in

the daytime. That is all that need be said at the present time, Dave,

and you will attend to your duty as usual. If you lose much sleep, you

may make it up in the forenoon watch."

"I don't care for the sleep, Captain Passford, and I can keep awake

all night."

"One thing more, Dave; between eight bells and eight bells to-night,

during the first watch, you may get at something, but you must keep out

of sight as much as you can," added Christy, as he rose from his

armchair, and went into his state room.

Dave busied himself in clearing the table, but he was in a very

thoughtful mood all the time. Loading up his tray with dishes, he

carried them through the steerage to the galley, where he found Mulgrum

engaged in washing those from the ward room, which he had brought out

some time before. The steward looked at the deaf mute with more interest

than he had regarded him before. He was a supernumerary on board, and

any one who had anything to do called Pink to do it.

77

Another waiter was greatly needed, and Mr. Nawood, the chief steward,

had engaged one, but he had failed to come on board before the steamer

sailed. Pink had been pressed into service for the steerage; but he was

of little use, and the work seemed very distasteful, if not disgusting,