A

MATTER

OF

PROPORTION

In order to make a man stop, you must

convince him that it's impossible to go on.

Some people, though, just can't be convinced.

BY ANNE WALKER

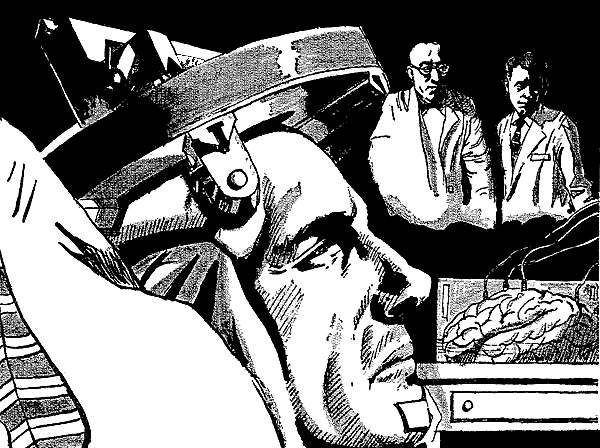

Illustrated by Bernklau

n the dark, our glider

chutes zeroed neatly

on target—only Art

Benjamin missed the

edge of the gorge.

When we were sure Invader hadn't

heard the crashing of bushes, I

climbed down after him. The climb,

and what I found, left me shaken.

A Special Corps squad leader is not

expendable—by order. Clyde Esterbrook,

my second and ICEG mate,

would have to mine the viaduct

while my nerve and glycogen stabilized.

We timed the patrols. Clyde said,

"Have to wait till a train's coming.

No time otherwise." Well, it was

his show. When the next pair of

burly-coated men came over at a

trot, he breathed, "Now!" and

ghosted out almost before they were

clear.

I switched on the ICEG—inter-cortical

encephalograph—planted in

my temporal bone. My own senses

could hear young Ferd breathing,

feel and smell the mat of pine needles

under me. Through Clyde's, I

could hear the blind whuffle of wind

in the girders, feel the crude wood of

ties and the iron-cold molding of

rails in the star-dark. I could feel,

too, an odd, lilting elation in his

mind, as if this savage universe were

a good thing to take on—spray guns,

cold, and all.

We wanted to set the mine so the

wreckage would clobber a trail below,

one like they'd built in Burma

and Japan, where you wouldn't think

a monkey could go; but it probably

carried more supplies than the viaduct

itself. So Clyde made adjustments

precisely, just as we'd figured

it with the model back at base. It was

a tricky, slow job in the bitter dark.

I began to figure: If he armed it

for this train, and ran, she'd go off

while we were on location and we'd

be drenched in searchlights and

spray guns. Already, through his

fingers, I felt the hum in the rails

that every tank-town-reared kid

knows. I turned up my ICEG. "All

right, Clyde, get back. Arm it when

she's gone past, for the next one."

I felt him grin, felt his lips form

words: "I'll do better than that,

Willie. Look, Daddy-o, no hands!"

He slid over the edge and rested

elbows and ribs on the raw tie ends.

We're all acrobats in the Corps.

But I didn't like this act one little

bit. Even if he could hang by his

hands, the heavy train would jolt

him off. But I swallowed my

thoughts.

He groped with his foot, contacted

a sloping beam, and brought his

other foot in. I felt a dull, scraping

slither under his moccasin soles.

"Frost," he thought calmly, rubbed

a clear patch with the edge of his

foot, put his weight on it, and

transferred his hands to the beam

with a twist we hadn't learned in

Corps school. My heart did a double-take;

one slip and he'd be off into

the gorge, and the frost stung, melting

under his bare fingers. He lay

in the trough of the massive H-beam,

slid down about twenty feet to where

it made an angle with an upright,

and wedged himself there. It took

all of twenty seconds, really. But I

let out a breath as if I'd been holding

it for minutes.

As he settled, searchlights began

skimming the bridge. If he'd been

running, he'd have been shot to a

sieve. As it was, they'd never see

him in the mingled glare and black.

His heart hadn't even speeded up

beyond what was required by exertion.

The train roared around a

shoulder and onto the viaduct, shaking

it like an angry hand. But as the

boxcars thunder-clattered above his

head, he was peering into the gulf

at a string of feeble lights threading

the bottom. "There's the flywalk,

Willie. They know their stuff. But

we'll get it." Then, as the caboose

careened over and the searchlights

cut off, "Well, that gives us ten minutes

before the patrol comes back."

He levered onto his side, a joint

at a time, and began to climb the

beam. Never again for me, even by

proxy! You just couldn't climb that

thing nohow! The slope was too

steep. The beam was too massive to

shinny, yet too narrow to lie inside

and elbow up. The metal was too

smooth, and scummed with frost.

His fingers were beginning to numb.

And—he was climbing!

In each fin of the beam, every foot

or so, was a round hole. He'd get one

finger into a hole and pull, inching

his body against the beam. He timed

himself to some striding music I

didn't know, not fast but no waste

motion, even the pauses rhythmic.

I tell you. I was sweating under

my leathers. Maybe I should have

switched the ICEG off, for my own

sake if not to avoid distracting

Clyde. But I was hypnotized, climbing.

In the old days, when you were

risking your neck, you were supposed

to think great solemn thoughts.

Recently, you're supposed to think

about something silly like a singing

commercial. Clyde's mind was neither

posturing in front of his mental

mirror nor running in some feverish

little circle. He faced terror as

big as the darkness from gorge bottom

to stars, and he was just simply

as big as it was—sheer life exulting

in defying the dark, the frost and

wind and the zombie grip of Invader.

I envied him.

Then his rhythm checked. Five

feet from the top, he reached confidently

for a finger hole ... No hole.

He had already reached as high

as he could without shifting his purchase

and risking a skid—and even

his wrestler's muscles wouldn't make

the climb again. My stomach quaked:

Never see sunlight in the trees

any more, just cling till dawn picked

you out like a crow's nest in a dead

tree; or drop ...

Not Clyde. His flame of life

crouched in anger. Not only the

malice of nature and the rage of

enemies, but human shiftlessness

against him too? Good! He'd take

it on.

Shoulder, thigh, knee, foot scraped

off frost. He jammed his jaw

against the wet iron. His right hand

never let go, but it crawled up the

fin of the strut like a blind animal,

while the load on his points of

purchase mounted—watchmaker co-ordination

where you'd normally

think in boilermaker terms. The

flame sank to a spark as he focused,

but it never blinked out. This was

not the anticipated, warded danger,

but the trick punch from nowhere.

This was It. A sneak squall buffeted

him. I cursed thinly. But he sensed

an extra purchase from its pressure,

and reached the last four inches with

a swift glide. The next hole was

there.

He waited five heartbeats, and

pulled. He began at the muscular

disadvantage of aligned joints. He

had to make it the first time; if you

can't do it with a dollar, you won't

do it with the change. But as elbow

and shoulder bent, the flame soared

again: Score one more for life!

A minute later, he hooked his arm

over the butt of a tie, his chin, his

other arm, and hung a moment. He

didn't throw a knee up, just rolled

and lay between the rails. Even as

he relaxed, he glanced at his watch:

three minutes to spare. Leisurely, he

armed the mine and jogged back to

me and Ferd.

As I broke ICEG contact, his

flame had sunk to an ember glow of

anticipation.

We had almost reached the cave

pricked on our map, when we heard

the slam of the mine, wee and far-off.

We were lying doggo looking

out at the snow peaks incandescent

in dawn when the first Invader patrols

trailed by below. Our equipment

was a miracle of hot food and basic

medication. Not pastimes, though;

and by the second day of hiding, I

was thinking too much. There was

Clyde, an Inca chief with a thread

of black mustache and incongruous

hazel eyes, my friend and ICEG

mate—what made him tick? Where

did he get his delight in the bright

eyes of danger? How did he gear

his daredevil valor, not to the icy

iron and obligatory killing, but to

the big music and stars over the

gorge? But in the Corps, we don't

ask questions and, above all, never

eavesdrop on ICEG.

Young Ferd wasn't so inhibited.

Benjamin's death had shaken him—losing

your ICEG mate is like losing

an eye. He began fly-fishing Clyde:

How had Clyde figured that stunt,

in the dark, with the few minutes

he'd had?

"There's always a way, Ferd, if

you're fighting for what you really

want."

"Well, I want to throw out Invader,

all right, but—"

"That's the start, of course, but

beyond that—" He changed the subject:

perhaps only I knew of his

dream about a stronghold for rebels

far in these mountains. He smiled.

"I guess you get used to calculated

risks. Except for imagination, you're

as safe walking a ledge twenty

stories up, as down on the sidewalk."

"Not if you trip."

"That's the calculated risk. If you

climb, you get used to it."

"Well, how did you get used to

it? Were you a mountaineer or an

acrobat?"

"In a way, both." Clyde smiled

again, a trifle bitterly and switched

the topic. "Anyway, I've been in

action for the duration except some

time in hospital."

Ferd was onto that boner like an

infielder. To get into SC you have

to be not only championship fit, but

have no history of injury that could

crop up to haywire you in a pinch.

So, "Hospital? You sure don't show

it now."

Clyde was certainly below par. To

cover his slip he backed into a bigger,

if less obvious, one. "Oh,

I was in that Operation Armada

at Golden Gate. Had to be patched

up."

He must have figured, Ferd had

been a kid then, and I hadn't been

too old. Odds were, we'd recall the

episode, and no more. Unfortunately,

I'd been a ham operator and

I'd been in the corps that beamed

those fireships onto the Invader supply

fleet in the dense fog. The whole

episode was burned into my brain.

It had been kamikaze stuff, though

there'd been a theoretical chance of

the thirty men escaping, to justify

sending them out. Actually, one

escape boat did get back with three

men.

I'd learned about those men, out

of morbid, conscience-scalded curiosity.

Their leader was Edwin Scott,

a medical student. At the very start

he'd been shot through the lower

spine. So, his companions put him

in the escape boat while they clinched

their prey. But as the escape boat

sheered off, the blast of enemy fire

killed three and disabled two.

Scott must have been some boy.

He'd already doctored himself with

hemostatics and local anaesthetics

but, from the hips down, he was

dead as salt pork, and his visceral

reflexes must have been reacting like

a worm cut with a hoe. Yet somehow,

he doctored the two others and

got that boat home.

The other two had died, but Scott

lived as sole survivor of Operation

Armada. And he hadn't been a big,

bronze, Latin-Indian with incongruous

hazel eyes, but a snub-nosed redhead.

And he'd been wheel-chaired

for life. They'd patched him up,

decorated him, sent him to a base

hospital in Wisconsin where he

could live in whatever comfort was

available. So, he dropped out of

sight. And now, this!

Clyde was lying, of course. He'd

picked the episode at random. Except

that so much else about him didn't

square. Including his name compared

to his physique, now I thought

about it.

I tabled it during our odyssey

home. But during post-mission leave,

it kept bothering me. I checked, and

came up with what I'd already

known: Scott had been sole survivor,

and the others were certified dead.

But about Scott, I got a runaround.

He'd apparently vanished. Oh,

they'd check for me, but that could

take years. Which didn't lull my

curiosity any. Into Clyde's past I

was sworn not to pry.

We were training for our next assignment,

when word came through

of the surrender at Kelowna. It was

a flare of sunlight through a black

sky. The end was suddenly close.

Clyde and I were in Victoria, British

Columbia. Not subscribing to

the folkway that prescribes seasick

intoxication as an expression of joy,

we did the town with discrimination.

At midnight we found ourselves

strolling along the waterfront in that

fine, Vancouver-Island mist, with

just enough drink taken to be moving

through a dream. At one point,

we leaned on a rail to watch the

mainland lights twinkling dimly like

the hope of a new world—blackout

being lifted.

Suddenly, Clyde said, "What's

fraying you recently, Will? When

we were taking our ICEG reconditioning,

it came through strong as

garlic, though you wouldn't notice

it normally."

Why be coy about an opening like

that? "Clyde, what do you know

about Edwin Scott?" That let him

spin any yarn he chose—if he chose.

He did the cigarette-lighting routine,

and said quietly, "Well, I was

Edwin Scott, Will." Then, as I waited,

"Yes, really me, the real me

talking to you. This," he held out a

powerful, coppery hand, "once belonged

to a man called Marco da

Sanhao ... You've heard of transplanting

limbs?"

I had. But this man was no transplant

job. And if a spinal cord is

cut, transplanting legs from Ippalovsky,

the primo ballerino, is worthless.

I said, "What about it?"

"I was the first—successful—brain

transplant in man."

For a moment, it queered me, but

only a moment. Hell, you read in

fairy tales and fantasy magazines

about one man's mind in another

man's body, and it's marvelous, not

horrible. But—

By curiosity, I know a bit about

such things. A big surgery journal,

back in the '40s, had published a

visionary article on grafting a whole

limb, with colored plates as if for

a real procedure[A]. Then they'd developed

techniques for acclimating a

graft to the host's serum, so it would

not react as a foreign body. First,

they'd transplanted hunks of ear and

such; then, in the '60s, fingers, feet,

and whole arms in fact.

But a brain is another story. A

cut nerve can grow together; every

fiber has an insulating sheath which

survives the cut and guides growing

stumps back to their stations. In the

brain and spinal cord, no sheaths;

growing fibers have about the chance

of restoring contact that you'd have

of traversing the Amazon jungle on

foot without a map. I said so.

"I know," he said, "I learned all

I could, and as near as I can put it,

it's like this: When you cut your

finger, it can heal in two ways. Usually

it bleeds, scabs, and skin grows

under the scab, taking a week or so.

But if you align the edges exactly,

at once, they may join almost immediately

healing by First Intent.

Likewise in the brain, if they line up

cut nerve fibers before the cut-off

bit degenerates, it'll join up with

the stump. So, take a serum-conditioned

brain and fit it to the stem of

another brain so that the big fiber

bundles are properly fitted together,

fast enough, and you can get better

than ninety per cent recovery."

"Sure," I said, parading my own

knowledge, "but what about injury

to the masses of nerve cells? And

you'd have to shear off the nerves

growing out of the brain."

"There's always a way, Willie.

There's a place in the brain stem

called the isthmus, no cell masses,

just bundles of fibers running up and

down. Almost all the nerves come

off below that point; and the few

that don't can be spliced together,

except the smell nerves and optic

nerve. Ever notice I can't smell,

Willie? And they transplanted my

eyes with the brain—biggest trick

of the whole job."

It figured. But, "I'd still hate to

go through with it."

"What could I lose? Some paraplegics

seem to live a fuller life than

ever. Me, I was going mad. And I'd

seen the dogs this research team at

my hospital was working on—old

dogs' brains in whelps' bodies, spry

as natural.

"Then came the chance. Da Sanhao

was a Brazilian wrestler stranded

here by the war. Not his war, he

said; but he did have the decency to

volunteer as medical orderly. But he

got conscripted by a bomb that took

a corner off the hospital and one

off his head. They got him into

chemical stasis quicker than it'd ever

been done before, but he was dead

as a human being—no brain worth

salvaging above the isthmus. So, the

big guns at the hospital saw a chance

to try their game on human material,

superb body and lower nervous

system in ideal condition, waiting for

a brain. Only, whose?

"Naturally, some big-shot's near

the end of his rope and willing to

gamble. But I decided it would be a

forgotten little-shot, name of Edwin

Scott. I already knew the surgeons

from being a guinea pig on ICEG.

Of course, when I sounded them out,

they gave me a kindly brush-off: The

matter was out of the their hands.

However, I knew whose hands it was

in. And I waited for my chance—a

big job that needed somebody expendable.

Then I'd make a deal, writing

my own ticket because they'd

figure I'd never collect. Did you

hear about Operation Seed-corn?"

That was the underground railway

that ran thousands of farmers out of

occupied territory. Manpower was

what finally broke Invader, improbable

as it seems. Epidemics, desertions,

over-extended lines, thinned

that overwhelming combat strength;

and every farmer spirited out of

their hands equalled ten casualties. I

nodded.

"Well, I planned that with myself

as director. And sold it to Filipson."

I contemplated him: just a big

man in a trench coat and droop-brimmed

hat silhouetted against the

lamp-lit mist. I said, "You directed

Seed-corn out of a wheel chair in

enemy territory, and came back to

get transplanted into another body?

Man, you didn't tell Ferd a word

of a lie when you said you were used

to walking up to death." (But there

was more: Besides that dour Scot's

fortitude, where did he come by that

high-hearted valor?)

He shrugged. "You do what you

can with what you've got. Those

weren't the big adventures I was

thinking about when I said that.

I had a team behind me in

those—"

I could only josh. "I'd sure like

to hear the capperoo then."

He toed out his cigarette. "You're

the only person who's equipped for

it. Maybe you'd get it, Willie."

"How do you mean?"

"I kept an ICEG record. Not that

I knew it was going to happen, just

wanted proof if they gave me a

deal and I pulled it off. Filipson

wouldn't renege, but generals were

expendable. No one knew I had that

transmitter in my temporal bone, and

I rigged it to get a tape on my home

receiver. Like to hear it?"

I said what anyone would, and

steered him back to quarters before

he'd think better of it. This would

be something!

On the way, he filled in background.

Scott had been living out

of hospital in a small apartment, enjoying

as much liberty as he could

manage. He had equipment so he

could stump around, and an antique

car specially equipped. He wasn't

complimentary about them. Orthopedic

products had to be: unreliable,

hard to service, unsightly, intricate,

and uncomfortable. If they also

squeaked and cut your clothes, fine!

Having to plan every move with

an eye on weather and a dozen other

factors, he developed in uncanny

foresight. Yet he had to improvise at

a moment's notice. With life a continuous

high-wire act, he trained

every surviving fiber to precision,

dexterity, and tenacity. Finally, he

avoided help. Not pride, self-preservation;

the compulsively helpful

have rarely the wit to ask before

rushing in to knock you on your

face, so he learned to bide his time

till the horizon was clear of beaming

simpletons. Also, he found an interest

in how far he could go.

These qualities, and the time

he had for thinking, begot Seed-corn.

When he had it convincing, he

applied to see General Filipson, head

of Regional Intelligence, a man with

both insight and authority to make

the deal—but also as tough as his

post demanded. Scott got an appointment

two weeks ahead.

That put it early in April, which

decreased the weather hazard—a

major consideration in even a trip

to the Supermarket. What was Scott's

grim consternation, then, when he

woke on D-day to find his windows

plastered with snow under a driving

wind—not mentioned in last night's

forecast of course.

He could concoct a plausible excuse

for postponement—which Filipson

was just the man to see

through; or call help to get him to

HQ—and have Filipson bark, "Man,

you can't even make it across town

on your own power because of a

little snow." No, come hell or blizzard,

he'd have to go solo. Besides,

when he faced the inevitable unexpected

behind Invader lines, he

couldn't afford a precedent of having

flinched now.

He dressed and breakfasted with

all the petty foresights that can mean

the shaving of clearance in a tight

squeeze, and got off with all the

margin of time he could muster. In

the apartment court, he had a parking

space by the basement exit and,

for a wonder, no free-wheeling nincompoop

had done him out of it

last night. Even so, getting to the

car door illustrated the ordeal ahead;

the snow was the damp, heavy stuff

that packs and glares. The streets

were nasty, but he had the advantage

of having learned restraint and foresight.

HQ had been the post office, a

ponderous red-stone building filling

a whole block. He had scouted it

thoroughly in advance, outside and

in, and scheduled his route to the

general's office, allowing for minor

hazards. Now, he had half an hour

extra for the unscheduled major

hazard.

But on arriving, he could hardly

believe his luck. No car was yet

parked in front of the building, and

the walk was scraped clean and salted

to kill the still falling flakes. No

problems. He parked and began to

unload himself quickly, to forestall

the elderly MP who hurried towards

him. But, as Scott prepared to thank

him off, the man said, "Sorry, Mac,

no one can park there this morning."

Scott felt the chill of nemesis.

Knowing it was useless, he protested

his identity and mission.

But, "Sorry, major. But you'll

have to park around back. They're

bringing in the big computer. General

himself can't park here. Them's

orders."

He could ask the sergeant to park

the car. But the man couldn't leave

his post, would make a to-do calling

someone—and that was Filipson's

suite overlooking the scene. No dice.

Go see what might be possible.

But side and back parking were

jammed with refugees from the computer,

and so was the other side. And

he came around to the front again.

Five minutes wasted. He thought

searchingly.

He could drive to a taxi lot, park

there, and be driven back by taxi,

disembark on the clean walk, and

there you were. Of course, he could

hear Filipson's "Thought you drove

your own car, ha?" and his own

damaging excuses. But even Out

Yonder, you'd cut corners in emergency.

It was all such a comfortable

Out, he relaxed. And, relaxing, saw

his alternative.

He was driving around the block

again, and noted the back entrance.

This was not ground level, because

of the slope of ground; it faced a

broad landing, reached by a double

flight of steps. These began on each

side at right-angles to the building

and then turned up to the landing

along the face of the wall. Normally,

they were negotiable; but now, even

had he found parking near them, he

hadn't the chance of the celluloid

cat in hell of even crossing the ten

feet of uncleaned sidewalk. You

might as well climb an eighty-degree,

fifty-foot wall of rotten ice. But there

was always a way, and he saw it.

The unpassable walk itself was an

avenue of approach. He swung his

car onto it at the corner, and drove

along it to the steps to park in the

angle between steps and wall—and

discovered a new shut-out. He'd expected

the steps to be a mean job

in the raw wind that favored this

face of the building; but a wartime

janitor had swept them sketchily

only down the middle, far from the

balustrades he must use. By the balustrades,

early feet had packed a

semi-ice far more treacherous than

the untouched snow; and, the two

bottom steps curved out beyond the

balustrade. So ... a sufficiently reckless

alpinist might assay a cliff in a

sleet storm and gale, but he couldn't

even try if it began with an overhang.

Still time for the taxi. And so,

again Scott saw the way that was

always there: Set the car so he could

use its hood to heft up those first

steps.

Suddenly, his thinking metamorphosed:

He faced, not a miserable,

unwarranted forlorn hope, but the

universe as it was. Titanic pressure

suit against the hurricanes of Jupiter,

and against a gutter freshet, life

was always outclassed—and always

fought back. Proportions didn't matter,

only mood.

He switched on his ICEG to record

what might happen. I auditioned

it, but I can't disentangle it from

what he told me. For example, in his

words: Multiply distances by five,

heights by ten, and slickness by

twenty. And in the playback: Thirty

chin-high ledges loaded with soft

lard, and only finger holds and toe

holds. And you did it on stilts that

began, not at your heels, at your

hips. Add the hazard of Helpful

Hosea: "Here, lemme giveya hand,

Mac!", grabbing the key arm, and

crashing down the precipice on top of

you.

Switching on the ICEG took his

mind back to the snug apartment

where its receiver stood, the armchair,

books, desk of diverting work. It

looked awful good, but ... life

fought back, and always it found a

way.

He shucked his windbreaker because

it would be more encumbrance

than help in the showdown. He

checked, shoelaces, and strapped on

the cleats he had made for what they

were worth. He vetoed the bag of

sand and salt he kept for minor difficulties—far

too slow. He got out of

the car.

This could be the last job he'd

have to do incognito—Seed-corn,

he'd get credit for. Therefore, he

cherished it: triumph for its own

sake. Alternatively, he'd end at the

bottom in a burlesque clutter of

chrom-alum splints and sticks, with

maybe a broken bone to clinch the

decision. For some men, death is

literally more tolerable than defeat in

humiliation.

Eighteen shallow steps to the turn,

twelve to the top. Once, he'd have

cleared it in three heartbeats. Now,

he had to make it to a twenty-minute

deadline, without rope or alpenstock,

a Moon-man adapted to a fraction of

Earth gravity.

With the help of the car hood, the

first two pitches were easy. For the

next four or five, wind had swept

the top of the balustrade, providing

damp, gritty handhold. Before the

going got tougher, he developed a

technic, a rhythm and system of

thrusts proportioned to heights and

widths, a way of scraping holds

where ice was not malignantly welded

to stone, an appreciation of snow

texture and depth, an economy of

effort.

He was enjoying a premature

elation when, on the twelfth step,

a cleat strap gave. Luckily, he was

able to take his lurch with a firm

grip on the balustrade; but he felt

depth yawning behind him. Dourly,

he took thirty seconds to retrieve the

cleat; stitching had been sawed

through by a metal edge—just as

he'd told the cocksure workman it

would be. Oh, to have a world where

imbecility wasn't entrenched! Well—he

was fighting here and now for the

resources to found one. He resumed

the escalade, his rhythm knocked

cockeyed.

Things even out. Years back, an

Invader bomber had scored a near

miss on the building, and minor damage

to stonework was unrepaired.

Crevices gave fingerhold, chipped-out

hollows gave barely perceptible

purchase to the heel of his hand. Salutes

to the random effects of unlikely

causes!

He reached the turn, considered

swiftly. His fresh strength was

blunted; his muscles, especially in his

thumbs, were stiffening with chill.

Now: He could continue up the left

side, by the building, which was

tougher and hazardous with frozen

drippings, or by the outside, right-hand

rail, which was easier but meant

crossing the open, half-swept wide

step and recrossing the landing up

top. Damn! Why hadn't he foreseen

that? Oh, you can't think of everything.

Get going, left side.

The wall of the building was

rough-hewn and ornamented with

surplus carvings. Cheers for the

1890s architect!

Qualified cheers. The first three

lifts were easy, with handholds in a

frieze of lotus. For the next, he had

to heft with his side-jaw against a

boss of stone. A window ledge made

the next three facile. The final five

stared, an open gap without recourse.

He made two by grace of the janitor's

having swabbed his broom a

little closer to the wall. His muscles

began to wobble and waver: in his

proportions, he'd made two-hundred

feet of almost vertical ascent.

But, climbing a real ice-fall, you'd

unleash the last convulsive effort because

you had to. Here, when you

came down to it, you could always

sit and bump yourself down to the

car which was, in that context, a

mere safe forty feet away. So he went

on because he had to.

He got the rubber tip off one stick.

The bare metal tube would bore into

the snow pack. It might hold, if he

bore down just right, and swung his

weight just so, and got just the right

sliding purchase on the wall, and the

snow didn't give underfoot or undercane.

And if it didn't work—it didn't

work.

Beyond the landing, westwards,

the sky had broken into April blue,

far away over Iowa and Kansas, over

Operation Seed-corn, over the refuge

for rebels that lay at the end of all

his roads....

He got set ... and lifted. A thousand

miles nearer the refuge! Got

set ... and lifted, balanced over

plunging gulfs. His reach found a

round pilaster at the top, a perfect

grip for a hand. He drew himself up,

and this time his cleated foot cut

through snow to stone, and slipped,

but his hold was too good. And there

he was.

No salutes, no cheers, only one

more victory for life.

Even in victory, unlife gave you

no respite. The doorstep was three

feet wide, hollowed by eighty years

of traffic, and filled with frozen drippings

from its pseudo-Norman arch.

He had to tilt across it and catch the

brass knob—like snatching a ring in

a high dive.

No danger now, except sitting

down in a growing puddle till

someone came along to hoist him

under the armpits, and then arriving

at the general's late, with his seat

black-wet.... You unhorse your foeman,

curvet up to the royal box to

receive the victor's chaplet, swing

from your saddle, and fall flat on

your face.

But, he cogitated on the bench inside,

getting his other cleat off and

the tip back on his stick, things do

even out. No hearty helper had intervened,

no snot-nosed, gaping child

had twitched his attention, nobody's

secretary—pretty of course—had

scurried to helpfully knock him down

with the door. They were all out

front superintending arrival of the

computer.

The general said only, if tartly,

"Oh yes, major, come in. You're late,

a'n't you?"

"It's still icy," said Ed Scott. "Had

to drive carefully, you know."

In fact, he had lost minutes that

way, enough to have saved his exact

deadline. And that excuse, being in

proportion to Filipson's standard dimension,

was fair game.

I wondered what dimension Clyde

would go on to, now that the challenge

of war was past. To his rebels

refuge at last maybe? Does it matter?

Whatever it is, life will be outclassed,

and Scott-Esterbrook's brand of life

will fight back.

THE END

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Astounding Science Fiction August

1959. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.

copyright on this publication was renewed. Minor spelling and

typographical errors have been corrected without note.

Comments on "A Matter of Proportion" :