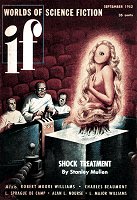

Johnson knew he was annoying the younger man, who so obviously lived

by the regulations in the Colonial Officer's Manual and lacked the

imagination to understand why he was doing this.... Evelyn E. Smith

is famous for her bitter-sweet stories of the worlds of Tomorrow.

the

most

sentimental

man

by EVELYN E. SMITH

Once these irritating farewells were over with, he

could begin to live as he wished and as he'd dreamed.

Johnson went to see the

others off at Idlewild. He

knew they'd expect him to

and, since it would be the last

conventional gesture he'd

have to make, he might as

well conform to their notions

of what was right and proper.

For the past few centuries

the climate had been getting

hotter; now, even though it

was not yet June, the day was

uncomfortably warm. The

sun's rays glinting off the

bright metal flanks of the

ship dazzled his eyes, and perspiration

made his shirt stick

to his shoulder blades beneath

the jacket that the formality

of the occasion had required.

He wished Clifford would

hurry up and get the leave-taking

over with.

But, even though Clifford

was undoubtedly even more

anxious than he to finish with

all this ceremony and take

off, he wasn't the kind of man

to let inclination influence his

actions. "Sure you won't

change your mind and come

with us?"

Johnson shook his head.

The young man looked at

him—hatred for the older

man's complication of what

should have been a simple departure

showing through the

pellicule of politeness. He was

young for, since this trip had

only slight historical importance

and none of any other

kind, the authorities had felt

a junior officer entirely sufficient.

It was clear, however,

that Clifford attributed his

commandership to his merits,

and he was very conscious of

his great responsibility.

"We have plenty of room

on the ship," he persisted.

"There weren't many left to

go. We could take you easily

enough, you know."

Johnson made a negative

sign again. The rays of the

sun beating full upon his

head made apparent the grey

that usually blended into the

still-thick blond hair. Yet,

though past youth, he was far

from being an old man. "I've

made my decision," he said,

remembering that anger now

was pointless.

"If it's—if you're just too

proud to change your mind,"

the young commander said,

less certainly, "I'm sure everyone

will understand if ...

if ..."

Johnson smiled. "No, it's

just that I want to stay—that's

all."

But the commander's clear

blue eyes were still baffled,

uneasy, as though he felt he

had not done the utmost that

duty—not duty to the service

but to humanity—required.

That was the trouble with

people, Johnson thought:

when they were most well-meaning

they became most

troublesome.

Clifford lowered his voice

to an appropriately funeral

hush, as a fresh thought obviously

struck him. "I know,

of course, that your loved

ones are buried here and perhaps

you feel it's your duty

to stay with them...?"

At this Johnson almost forgot

that anger no longer had

any validity. By "loved ones"

Clifford undoubtedly had

meant Elinor and Paul. It was

true that Johnson had had a

certain affection for his wife

and son when they were alive;

now that they were dead they

represented an episode in his

life that had not, perhaps,

been unpleasant, but was certainly

over and done with

now.

Did Clifford think that was

his reason for remaining?

Why, he must believe Johnson

to be the most sentimental

man on Earth. "And, come to

think of it," Johnson said to

himself, amused, "I am—or

soon will be—just that."

The commander was still

unconsciously pursuing the

same train of thought. "It

does seem incredible," he said

in a burst of boyish candor

that did not become him, for

he was not that young, "that

you'd want to stay alone on

a whole planet. I mean to say—entirely

alone.... There'll

never be another ship, you

know—at least not in your

lifetime."

Johnson knew what the other

man was thinking. If

there'd been a woman with

Johnson now, Clifford might

have been able to understand

a little better how the other

could stick by his decision.

Johnson wriggled, as sweat

oozed stickily down his back.

"For God's sake," he said silently,

"take your silly ship

and get the hell off my planet."

Aloud he said, "It's a

good planet, a little worn-out

but still in pretty good shape.

Pity you can't trade in an old

world like an old car, isn't

it?"

"If it weren't so damned far

from the center of things,"

the young man replied, defensively

assuming the burden of

all civilization, "we wouldn't

abandon it. After all, we hate

leaving the world on which

we originated. But it's a long

haul to Alpha Centauri—you

know that—and a tremendously

expensive one. Keeping up

this place solely out of sentiment

would be sheer waste—the

people would never

stand for the tax burden."

"A costly museum, yes,"

Johnson agreed.

How much longer were

these dismal farewells going

to continue? How much longer

would the young man still

feel the need to justify himself?

"If only there were others

fool enough—if only there

were others with you.... But,

even if anybody else'd be willing

to cut himself off entirely

from the rest of the civilized

universe, the Earth won't support

enough of a population

to keep it running. Not according

to our present living

standards anyway.... Most of

its resources are gone, you

know—hardly any coal or oil

left, and that's not worth digging

for when there are better

and cheaper fuels in the

system."

He was virtually quoting

from the Colonial Officer's

Manual. Were there any people

left able to think for

themselves, Johnson wondered.

Had there ever been?

Had he thought for himself

in making his decision, or was

he merely clinging to a childish

dream that all men had

had and lost?

"With man gone, Earth will

replenish herself," he said

aloud. First the vegetation

would begin to grow thick.

Already it had released itself

from the restraint of cultivation;

soon it would be spreading

out over the continent,

overrunning the cities with

delicately persistent green

tendrils. Some the harsh winters

would kill, but others

would live on and would multiply.

Vines would twist themselves

about the tall buildings

and tenderly, passionately

squeeze them to death ...

eventually send them tumbling

down. And then the

trees would rear themselves

in their places.

The swamps that man had

filled in would begin to reappear

one by one, as the land

sank back to a pristine state.

The sea would go on changing

her boundaries, with no

dikes to stop her. Volcanoes

would heave up the land into

different configurations. The

heat would increase until it

grew unbearable ... only there

would be no one—no human,

anyway—to bear it.

Year after year the leaves

would wither and fall and decay.

Rock would cover them.

And some day ... billions of

years thence ... there would be

coal and oil—and nobody to

want them.

"Very likely Earth will replenish

herself," the commander

agreed, "but not in

your time or your children's

time.... That is, not in my

children's time," he added hastily.

The handful of men lined

up in a row before the airlock

shuffled their feet and

allowed their muttering to become

a few decibels louder.

Clifford looked at his wrist

chronometer. Obviously he

was no less anxious than the

crew to be off, but, for the

sake of his conscience, he

must make a last try.

"Damn your conscience,"

Johnson thought. "I hope that

for this you feel guilty as

hell, that you wake up nights

in a cold sweat remembering

that you left one man alone

on the planet you and your

kind discarded. Not that I

don't want to stay, mind you,

but that I want you to suffer

the way you're making me suffer

now—having to listen to

your platitudes."

The commander suddenly

stopped paraphrasing the

Manual. "Camping out's fun

for a week or two, you know,

but it's different when it's for

a lifetime."

Johnson's fingers curled in

his palms ... he was even angrier

now that the commander

had struck so close to home.

Camping out ... was that all he

was doing—fulfilling childhood

desires, nothing more?

Fortunately Clifford didn't

realize that he had scored, and

scuttled back to the shelter of

the Manual. "Perhaps you

don't know enough about the

new system in Alpha Centauri,"

he said, a trifle wildly.

"It has two suns surrounded

by three planets, Thalia, Aglaia,

and Euphrosyne. Each of

these planets is slightly smaller

than Earth, so that the decrease

in gravity is just great

enough to be pleasant, without

being so marked as to be

inconvenient. The atmosphere

is almost exactly like that of

Earth's, except that it contains

several beneficial elements

which are absent here—and

the climate is more temperate.

Owing to the fact that

the planets are partially

shielded from the suns by

cloud layers, the temperature—except

immediately at the

poles and the equators, where

it is slightly more extreme—is

always equable, resembling

that of Southern California...."

"Sounds charming," said

Johnson. "I too have read the

Colonial Office handouts.... I

wonder what the people who

wrote them'll do now that

there's no longer any necessity

for attracting colonists—everybody's

already up in Alpha

Centauri. Oh, well;

there'll be other systems to

conquer and colonize."

"The word conquer is hardly

correct," the commander

said stiffly, "since not one of

the three planets had any indigenous

life forms that was

intelligent."

"Or life forms that you recognized

as intelligent," Johnson

suggested gently. Although

why should there be

such a premium placed on intelligence,

he wondered. Was

intelligence the sole criterion

on which the right to life and

to freedom should be based?

The commander frowned

and looked at his chronometer

again. "Well," he finally said,

"since you feel that way and

you're sure you've quite made

up your mind, my men are

anxious to go."

"Of course they are," Johnson

said, managing to convey

just the right amount of reproach.

Clifford flushed and started

to walk away.

"I'll stand out of the way

of your jets!" Johnson called

after him. "It would be so anticlimactic

to have me burned

to a crisp after all this. Bon

voyage!"

There was no reply.

Johnson watched the silver

vessel shoot up into the sky

and thought, "Now is the

time for me to feel a pang, or

even a twinge, but I don't at

all. I feel relieved, in fact, but

that's probably the result of

getting rid of that fool Clifford."

He crossed the field briskly,

pulling off his jacket and discarding

his tie as he went. His

ground car remained where he

had parked it—in an area

clearly marked No Parking.

They'd left him an old car

that wasn't worth shipping to

the stars. How long it would

last was anybody's guess. The

government hadn't been deliberately

illiberal in leaving

him such a shabby vehicle; if

there had been any way to ensure

a continuing supply of

fuel, they would probably

have left him a reasonably

good one. But, since only a

little could be left, allowing

him a good car would have

been simply an example of

conspicuous waste, and the

government had always preferred

its waste to be inconspicuous.

He drove slowly through

the broad boulevards of Long

Island, savoring the loneliness.

New York as a residential

area had been a ghost town

for years, since the

greater part of its citizens

had been among the first to

emigrate to the stars. However,

since it was the capital

of the world and most of the

interstellar ships—particularly

the last few—had taken off

from its spaceports, it had

been kept up as an official embarkation

center. Thus, paradoxically,

it was the last city

to be completely evacuated,

and so, although the massive

but jerry-built apartment

houses that lined the streets

were already crumbling, the

roads had been kept in fairly

good shape and were hardly

cracked at all.

Still, here and there the

green was pushing its way up

in unlikely places. A few

more of New York's tropical

summers, and Long Island

would soon become a wilderness.

The streets were empty, except

for the cats sunning

themselves on long-abandoned

doorsteps or padding about

on obscure errands of their

own. Perhaps their numbers

had not increased since humanity

had left the city to

them, but there certainly

seemed to be more—striped

and solid, black and grey and

white and tawny—accepting

their citizenship with equanimity.

They paid no attention

to Johnson—they had long

since dissociated themselves

from a humanity that had not

concerned itself greatly over

their welfare. On the other

hand, neither he nor the surface

car appeared to startle

them; the old ones had seen

such before, and to kittens the

very fact of existence is the

ultimate surprise.

The Queensborough Bridge

was deadly silent. It was completely

empty except for a

calico cat moving purposefully

toward Manhattan. The

structure needed a coat of

paint, Johnson thought vaguely,

but of course it would never

get one. Still, even uncared

for, the bridges should outlast

him—there would be no

heavy traffic to weaken them.

Just in case of unforeseeable

catastrophe, however—he

didn't want to be trapped on

an island, even Manhattan Island—he

had remembered to

provide himself with a rowboat;

a motorboat would have

been preferable, but then the

fuel difficulty would arise

again....

How empty the East River

looked without any craft on

it! It was rather a charming

little waterway in its own

right, though nothing to compare

with the stately Hudson.

The water scintillated in

the sunshine and the air was

clear and fresh, for no factories

had spewed fumes and

smoke into it for many years.

There were few gulls, for

nothing was left for the scavenger;

those remaining were

forced to make an honest living

by catching fish.

In Manhattan, where the

buildings had been more

soundly constructed, the

signs of abandonment were

less evident ... empty streets,

an occasional cracked window.

Not even an unusual

amount of dirt because, in the

past, the normal activities of

an industrial and ruggedly individual

city had provided

more grime than years of neglect

could ever hope to equal.

No, it would take Manhattan

longer to go back than Long

Island. Perhaps that too

would not happen during his

lifetime.

Yet, after all, when he

reached Fifth Avenue he

found that Central Park had

burst its boundaries. Fifty-ninth

Street was already half

jungle, and the lush growth

spilled down the avenues and

spread raggedly out into the

side streets, pushing its way

up through the cracks it had

made in the surface of the

roads. Although the Plaza

fountain had not flowed for

centuries, water had collected

in the leaf-choked basin from

the last rain, and a group of

grey squirrels were gathered

around it, shrilly disputing

possession with some starlings.

Except for the occasional

cry of a cat in the distance,

these voices were all that he

heard ... the only sound. Not

even the sudden blast of a jet

regaining power ... he would

never hear that again; never

hear the stridor of a human

voice piercing with anger;

the cacophony of a hundred

television sets, each playing a

different program; the hoot

of a horn; off-key singing;

the thin, uncertain notes of an

amateur musician ... these

would never be heard on

Earth again.

He sent the car gliding

slowly ... no more traffic

rules ... down Fifth Avenue.

The buildings here also were

well-built; they were many

centuries old and would probably

last as many more. The

shop windows were empty,

except for tangles of dust ... an

occasional broken, discarded

mannequin.... In some instances

the glass had already

cracked or fallen out. Since

there were no children to

throw stones, however, others

might last indefinitely, carefully

glassing in nothingness.

Doors stood open and he

could see rows of empty

counters and barren shelves

fuzzed high with the dust of

the years since a customer

had approached them.

Cats sedately walked up

and down the avenue or sat

genteelly with tails tucked in

on the steps of the cathedral—as

if the place had been

theirs all along.

Dusk was falling. Tonight,

for the first time in centuries,

the street lamps would not go

on. Undoubtedly when it

grew dark he would see

ghosts, but they would be the

ghosts of the past and he had

made his peace with the past

long since; it was the present

and the future with which he

had not come to terms. And

now there would be no present,

no past, no future—but

all merged into one and he

was the only one.

At Forty-second Street pigeons

fluttered thickly

around the public library, fat

as ever, their numbers greater,

their appetites grosser. The

ancient library, he knew, had

changed little inside: stacks

and shelves would still be

packed thick with reading

matter. Books are bulky, so

only the rare editions had

been taken beyond the stars;

the rest had been microfilmed

and their originals left to

Johnson and decay. It was his

library now, and he had all

the time in the world to read

all the books in the world—for

there were more than he

could possibly read in the

years that, even at the most

generous estimate, were left

to him.

He had been wondering

where to make his permanent

residence for, with the whole

world his, he would be a fool

to confine himself to some

modest dwelling. Now he fancied

it might be a good idea

to move right into the library.

Very few places in Manhattan

could boast a garden of their

own.

He stopped the car to stare

thoughtfully at the little park

behind the grimy monument

to Neoclassicism. Like Central

Park, Bryant had already

slipped its boundaries and encroached

upon Sixth Avenue—Avenue

of the World, the

street signs said now, and before

that it had been Avenue

of the Nations and Avenue of

the Americas, but to the public

it had always been Sixth

Avenue and to Johnson, the

last man on Earth, it was

Sixth Avenue.

He'd live in the library,

while he stayed in New York,

that was—he'd thought that

in a few weeks, when it got

really hot, he might strike

north. He had always meant

to spend a summer in Canada.

His surface car would probably

never last the trip, but

the Museum of Ancient Vehicles

had been glad to bestow

half a dozen of the bicycles

from their exhibits upon him.

After all, he was, in effect, a

museum piece himself and so

as worth preserving as the

bicycles; moreover, bicycles

are difficult to pack for an

interstellar trip. With reasonable

care, these might last

him his lifetime....

But he had to have a permanent

residence somewhere,

and the library was an elegant

and commodious dwelling,

centrally located. New York

would have to be his headquarters,

for all the possessions

he had carefully

amassed and collected and

begged and—since money

would do him no good any

more—bought, were here. And

there were by far too many of

them to be transported to any

really distant location. He

loved to own things.

He was by no means an advocate

of Rousseau's complete

return to nature; whatever

civilization had left that he

could use without compromise,

he would—and thankfully.

There would be no electricity,

of course, but he had

provided himself with flashlights

and bulbs and batteries—not

too many of the last, of

course, because they'd grow

stale. However, he'd also laid

in plenty of candles and a

vast supply of matches.... Tins

of food and concentrates

and synthetics, packages of

seed should he grow tired of

all these and want to try

growing his own—fruit, he

knew, would be growing wild

soon enough.... Vitamins and

medicines—of course, were he

to get really ill or get hurt

in some way, it might be the

end ... but that was something

he wouldn't think of—something

that couldn't possibly

happen to him....

For his relaxation he had

an antique hand-wound phonograph,

together with thousands

of old-fashioned records.

And then, of course, he had

the whole planet, the whole

world to amuse him.

He even had provided himself

with a heat-ray gun and

a substantial supply of ammunition,

although he

couldn't imagine himself ever

killing an animal for food. It

was squeamishness that stood

in his way rather than any

ethical considerations, although

he did indeed believe

that every creature had the

right to live. Nonetheless,

there was the possibility that

the craving for fresh meat

might change his mind for

him. Besides, although hostile

animals had long been gone

from this part of the world—the

only animals would be

birds and squirrels and, farther

up the Hudson, rabbits

and chipmunks and deer ...

perhaps an occasional bear in

the mountains—who knew

what harmless life form might

become a threat now that its

development would be left unchecked?

A cat sitting atop one of

the stately stone lions outside

the library met his eye with

such a steady gaze of understanding,

though not of sympathy,

that he found himself

needing to repeat the by-now

almost magic phrase to himself:

"Not in my lifetime anyway."

Would some intelligent

life form develop to supplant

man? Or would the planet revert

to a primeval state of

mindless innocence? He

would never know and he

didn't really care ... no point

in speculating over unanswerable

questions.

He settled back luxuriously

on the worn cushions of

his car. Even so little as

twenty years before, it would

have been impossible for him—for

anyone—to stop his vehicle

in the middle of Forty-second

Street and Fifth Avenue

purely to meditate. But

it was his domain now. He

could go in the wrong direction

on one-way streets, stop

wherever he pleased, drive as

fast or as slowly as he would

(and could, of course). If he

wanted to do anything as vulgar

as spit in the street, he

could (but they were his

streets now, not to be sullied)

... cross the roads without

waiting for the lights to

change (it would be a long,

long wait if he did) ... go to

sleep when he wanted, eat as

many meals as he wanted

whenever he chose.... He

could go naked in hot weather

and there'd be no one to raise

an eyebrow, deface public

buildings (except that they

were private buildings now,

his buildings), idle without

the guilty feeling that there

was always something better

he could and should be doing

... even if there were not.

There would be no more guilty

feelings; without people

and their knowledge there

was no more guilt.

A flash of movement in the

bushes behind the library

caught his eye. Surely that

couldn't be a fawn in Bryant

Park? So soon?... He'd

thought it would be another

ten years at least before the

wild animals came sniffing

timidly along the Hudson,

venturing a little further each

time they saw no sign of their

age-old enemy.

But probably the deer was

only his imagination. He

would investigate further after

he had moved into the library.

Perhaps a higher building

than the library.... But then

he would have to climb too

many flights of stairs. The

elevators wouldn't be working

... silly of him to forget

that. There were a lot of

steps outside the library too—it

would be a chore to get

his bicycles up those steps.

Then he smiled to himself.

Robinson Crusoe would have

been glad to have had bicycles

and steps and such relatively

harmless animals as bears to

worry about. No, Robinson

Crusoe never had it so good

as he, Johnson, would have,

and what more could he

want?

For, whoever before in history

had had his dreams—and

what was wrong with dreams,

after all?—so completely

gratified? What child, envisioning

a desert island all his

own could imagine that his

island would be the whole

world? Together Johnson and

the Earth would grow young

again.

No, the stars were for others.

Johnson was not the first

man in history who had wanted

the Earth, but he had been

the first man—and probably

the last—who had actually

been given it. And he was

well content with his bargain.

There was plenty of room

for the bears too.

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Fantastic Universe August 1957.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.

copyright on this publication was renewed. Minor spelling and

typographical errors have been corrected without note.

Comments on "The Most Sentimental Man" :