The Project Gutenberg eBook of Neotropical Hylid Frogs, Genus Smilisca

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Neotropical Hylid Frogs, Genus Smilisca

Author: William Edward Duellman

Linda Trueb

Release date: October 22, 2011 [eBook #37823]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Tom Cosmas, Joseph Cooper and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NEOTROPICAL HYLID FROGS, GENUS SMILISCA ***

[Pg 281]

Museum of Natural History

Volume 17, No. 7, pp. 281-375, pls. 1-12, 17 figs.

July 14, 1966

Lawrence

1966

[Pg 282]

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, Henry S. Fitch, Frank B. Cross

Volume 17, No. 7, pp. 281-375, pls. 1-12, 17 figs.

Published July 14, 1966

Lawrence, Kansas

ROBERT R. (BOB) SANDERS, STATE PRINTER

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1966

31-3430

[Pg 283]

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 285 |

| Acknowledgments | 286 |

| Materials and Methods | 287 |

| Genus Smilisca Cope, 1865 | 287 |

| Key to Adults | 288 |

| Key to Tadpoles | 289 |

| Accounts of Species | 289 |

| Smilisca baudini (Duméril and Bibron) | 289 |

| Smilisca cyanosticta (Smith) | 303 |

| Smilisca phaeota (Cope) | 308 |

| Smilisca puma (Cope) | 314 |

| Smilisca sila New species | 318 |

| Smilisca sordida (Peters) | 323 |

| Analysis of Morphological Characters | 330 |

| Osteology | 330 |

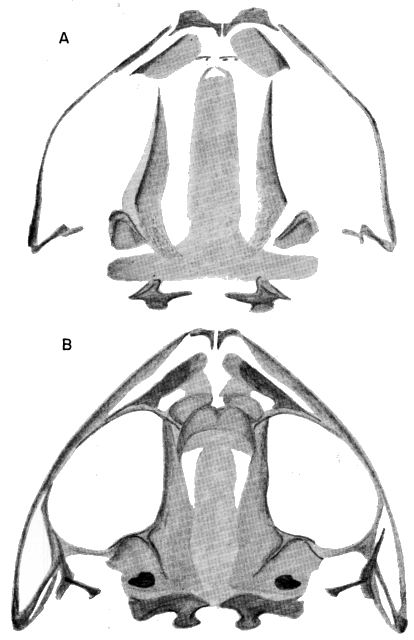

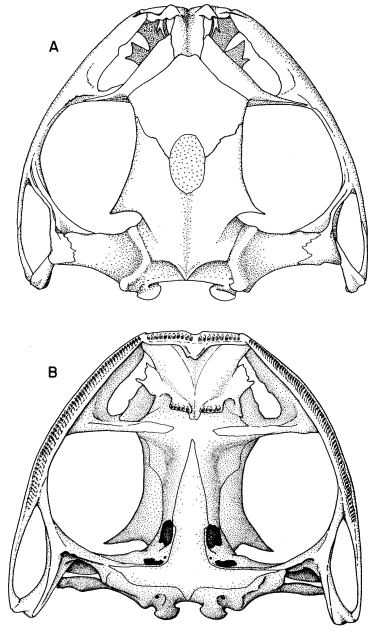

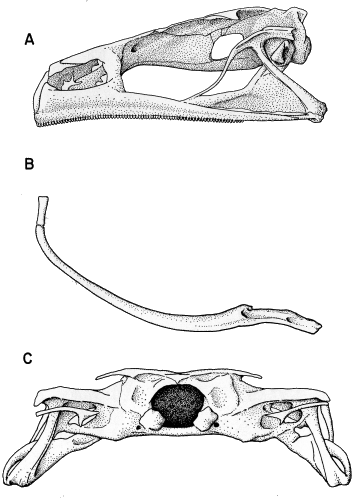

| Descriptive Osteology of Smilisca baudini | 331 |

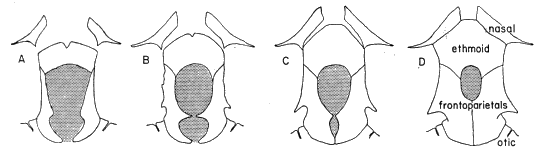

| Developmental Cranial Osteology of Smilisca baudini | 333 |

| Comparative Osteology | 336 |

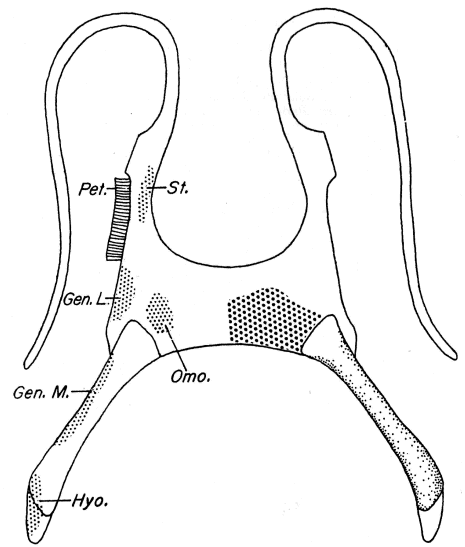

| Musculature | 341 |

| Skin | 342 |

| Structure | 342 |

| Comparative Biochemistry of Proteins | 343 |

| External Morphological Characters | 343 |

| Size and Proportions | 343 |

| Shape of Snout | 344 |

| Hands and Feet | 344 |

| Ontogenetic Changes | 344 |

| Coloration | 344 |

| Metachrosis | 345 |

| Chromosomes | 345 |

| Natural History [Pg 284] | 345 |

| Breeding | 345 |

| Time of Breeding | 345 |

| Breeding Sites | 346 |

| Breeding Behavior | 346 |

| Breeding Call | 351 |

| Eggs | 356 |

| Tadpoles | 357 |

| General Structure | 357 |

| Comparison of Species | 357 |

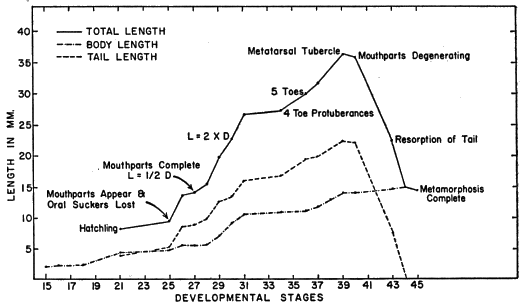

| Growth and Development | 361 |

| Behavior | 365 |

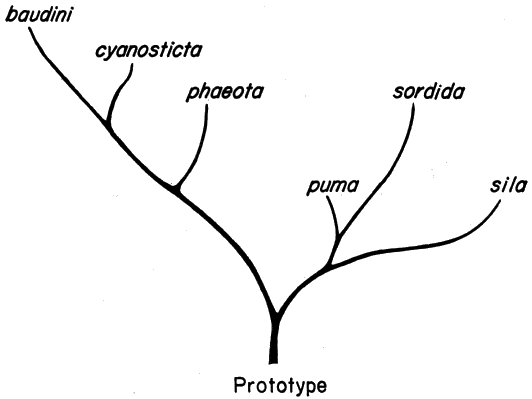

| Phylogenetic Relationships | 366 |

| Interspecific Relationships | 366 |

| Evolutionary History | 369 |

| Summary and Conclusions | 371 |

| Literature Cited | 372 |

[Pg 285]

The family Hylidae, as currently recognized, is composed of

about 34 genera and more than 400 species. Most genera (30) and

about 350 species live in the American tropics. Hyla and 10 other

genera inhabit Central America; four of those 10 genera (Gastrotheca,

Hemiphractus, Phrynohyas, and Phyllomedusa) are widely

distributed in South America. The other six genera are either restricted

to Central America or have their greatest differentiation

there. Plectrohyla and Ptychohyla inhabit streams in the highlands

of southern Mexico and northern Central America; Diaglena and

Triprion are casque-headed inhabitants of arid regions in México

and northern Central America. Anotheca is a tree-hole breeder in

cloud forests in Middle America. The genus Smilisca is the most

widespread geographically and diverse ecologically of the Central

American genera.

The definition of genera in the family Hylidae is difficult owing

to the vast array of species, most of which are poorly known as

regards their osteology, colors in life, and modes of life history.

The genera Diaglena, Triprion, Tetraprion, Osteocephalus, Trachycephalus,

Aparasphenodon, Corythomantis, Hemiphractus, Pternohyla,

and Anotheca have been recognized as distinct from one

another and from the genus Hyla on the basis of various modifications

of dermal bones of the cranium. Phyllomedusa is recognized

on the basis of a vertical pupil and opposable thumb; Plectrohyla

is characterized by the presence of a bony prepollex and the absence

of a quadratojugal. Gastrotheca is distinguished from other

hylids by the presence of a pouch in the back of females. A pair

of lateral vocal sacs behind the angles of the jaws and the well-developed

dermal glands were used by Duellman (1956) to distinguish

Phrynohyas from Hyla. He (1963a) cited the ventrolateral

glands in breeding males as diagnostic of Ptychohyla. Some species

groups within the vaguely defined genus Hyla have equally distinctive

characters. The Hyla septentrionalis group is characterized

by a casque-head, not much different from that in the genus Osteocephalus

(Trueb, MS). Males in the Hyla maxima group have a

protruding bony prepollex like that characteristically found in

Plectrohyla.

Ontogenetic development, osteology, breeding call, behavior, and

ecology are important in the recognition of species. By utilizing

[Pg 286]

the combination of many morphological and biological factors, the

genus Smilisca can be defined reasonably well as a natural, phyletic

assemblage of species. Because the wealth of data pertaining to

the morphology and biology of Smilisca is lacking for most other

tree frogs in Middle America it is not possible at present to compare

Smilisca with related groups in more than a general way.

Smilisca is an excellent example of an Autochthonous Middle

American genus. As defined by Stuart (1950) the Autochthonous

Middle American fauna originated from "hanging relicts" left in

Central America by the ancestral fauna that moved into South

America and differentiated there at a time when South America

was isolated from North and Middle America. The genus Smilisca,

as we define it, consists of six species, all of which occur in Central

America. One species ranges northward to southern Texas, and

one extends southward on the Pacific lowlands of South America

to Ecuador. We consider the genus Smilisca to be composed of

rather generalized hylids. Consequently, an understanding of the

systematics and zoogeography of the genus can be expected to be

of aid in studying more specialized members of the family.

Acknowledgments

Examination of many of the specimens used in our study was possible only

because of the cooperation of the curators of many systematic collections. For

lending specimens or providing working space in their respective institutions

we are grateful to Doris M. Cochran, Alice G. C. Grandison, Jean Guibe, Robert

F. Inger, Günther Peters, Gerald Raun, William J. Riemer, Jay M. Savage,

Hobart M. Smith, Wilmer W. Tanner, Charles F. Walker, Ernest E. Williams,

and Richard G. Zweifel.

We are indebted to Charles J. Cole and Charles W. Myers for able assistance

in the field. The cooperation of Martin H. Moynihan at Barro Colorado

Island, Charles M. Keenan of Corozal, Canal Zone, and Robert Hunter of San

José, Costa Rica, is gratefully acknowledged. Jay M. Savage turned over to

us many Costa Rican specimens and aided greatly in our work in Costa Rica.

James A. Peters helped us locate sites of collections in Ecuador and Coleman

J. Goin provided a list of localities for the genus in Colombia.

We especially thank Charles J. Cole for contributing the information on the

chromosomes, and Robert R. Patterson for preparing osteological specimens.

We thank M. J. Fouquette, Jr., who read the section on breeding calls and

offered constructive criticism.

Permits for collecting were generously provided by Ing. Rodolfo Hernandez

Corzo in México, Sr. Jorge A. Ibarra in Guatemala, and Ing. Milton Lopez in

Costa Rica. This report was made possible by support from the National

Science Foundation (Grants G-9827 and GB-1441) and the cooperation of the

Museum of Natural History at the University of Kansas. Some of the field

studies were carried out in Panamá under the auspices of a grant from the

National Institutes of Health (NIH GM-12020) in cooperation with the Gorgas

Memorial Laboratory in Panamá.

[Pg 287]

Materials and Methods

In our study we examined 4151 preserved frogs, 93 skeletal preparations,

88 lots of tadpoles and young, and six lots of eggs. We have collected specimens

in the field of all of the species. Observations on behavior and life history

were begun by the senior author in México in 1956 and completed by us

in Central America in 1964 and 1965.

Osteological data were obtained from dried skeletons and

cleaned and

stained specimens of all species, plus serial sections of the skull of Smilisca

baudini. Developmental stages to which tadpoles are assigned are in accordance

with the table of development published by Gosner (1960). Breeding

calls were recorded in the field on tape using Magnemite and Uher portable

tape recorders. Audiospectrographs were made by means of a Vibralyzer (Kay

Electric Company). External morphological features were measured in the

manner described by Duellman (1956). In the accounts of the species we

have attempted to give a complete synonymy. At the end of each species

account the localities from which specimens were examined are listed alphabetically

within each state, province, or department, which in turn are listed

alphabetically within each country. The countries are arranged from north

to south. Abbreviations for museum specimens are listed below:

| AMNH—American Museum of Natural History BMNH—British Museum (Natural History) BYU—Brigham Young University CNHM—Chicago Natural History Museum KU—University of Kansas Museum of Natural History MCZ—Museum of Comparative Zoology MNHN—Museu National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris UF—University of Florida Collections UIMNH—University of Illinois Museum of Natural History UMMZ—University of Michigan Museum of Zoology USC—University of Southern California USNM—United States National Museum TNHC—Texas Natural History Collection, University of Texas ZMB—Zoologisches Museum Berlin |

Genus Smilisca Cope, 1865

species Smilisca daulinia Cope, 1865 = Hyla baudini Duméril and Bibron,

1841]. Smith and Taylor, Bull. U. S. Natl. Mus., 194:75, June 17,

1948. Starrett, Copeia, 4:300, December 30, 1960. Goin, Ann. Carnegie

Museum, 36:15, July 14, 1961.

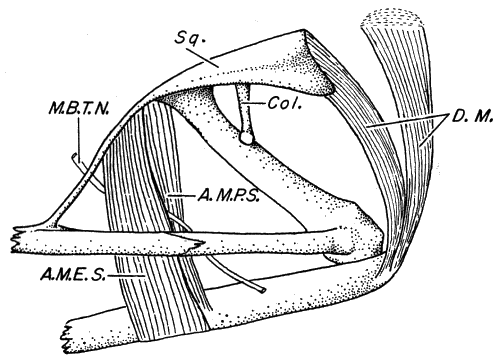

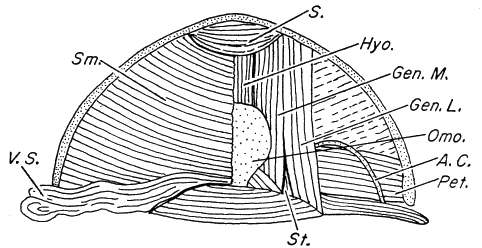

Definition.—Medium to large tree frogs having: (1) broad, well ossified

skull (consisting of a minimum amount of cartilage and/or secondarily ossified

cartilage), (2) no dermal co-ossification, (3) quadratojugal and internasal

septum present, (4) large ethmoid, (5) M. depressor mandibulae consisting

of two parts, one arising from dorsal fascia and other from posterior arm of

squamosal, (6) divided M. adductor mandibulae, (7) paired subgular vocal

sacs in males, (8) no dermal appendages, (9) pupil horizontally elliptical

(10) small amounts of amines and other active substances in skin, (11)

chromosome number of N = 12 and 2N = 24, (12) breeding call consisting of

poorly modulated, explosive notes, and (13) 2/3 tooth-rows in tadpoles.

Composition of genus.—As defined here the genus Smilisca contains six

recognizable species. An alphabetical list of the specific and subspecific names

[Pg 288]

that we consider to be applicable to species of Smilisca recognized herein is

given below.

| Names proposed | Valid names | |

| Hyla baudini Duméril and Bibron, 1841 | = S. baudini | |

| Hyla baudini dolomedes Barbour, 1923 | = S. phaeota | |

| Hyla beltrani Taylor, 1942 | = S. baudini | |

| Hyla gabbi Cope, 1876 | = S. sordida | |

| Hyla labialis Peters, 1863 | = S. phaeota | |

| Hyla manisorum Taylor, 1954 | = S. baudini | |

| Hyla muricolor Cope, 1862 | = S. baudini | |

| Hyla nigripes Cope, 1876 | = S. sordida | |

| Hyla pansosana Brocchi, 1877 | = S. baudini | |

| Hyla phaeota Cope, 1862 | = S. phaeota | |

| Hyla phaeota cyanosticta Smith, 1953 | = S. cyanosticta | |

| Hyla puma Cope, 1885 | = S. puma | |

| Hyla salvini Boulenger, 1882 | = S. sordida | |

| Hyla sordida Peters, 1863 | = S. sordida | |

| Hyla vanvlietii Baird, 1854 | = S. baudini | |

| Hyla vociferans Baird, 1859 | = S. baudini | |

| Hyla wellmanorum Taylor, 1952 | = S. puma |

Distribution of genus.—Most of lowlands of México and Central America,

in some places to elevations of nearly 2000 meters, southward from southern

Sonora and Río Grande Embayment of Texas, including such continental islands

as Isla Cozumel, México, and Isla Popa and Isla Cebaco, Panamá, to

northern South America, where known from Caribbean coastal regions and

valleys of Río Cauca and Río Magdalena in Colombia, and Pacific slopes of

Colombia and northern Ecuador.

Key to Adults

| 1. | Larger frogs ([M] to 76 mm., [F] to 90 mm.) having broad flat heads and a dark brown or black postorbital mark encompassing tympanum |

| 2 | |

| Smaller frogs ([M] to 45 mm., [F] to 64 mm.) having narrower heads and lacking a dark brown or black postorbital mark encompassing tympanum | |

| 4 | |

| 2. | Lips barred; flanks cream-colored with bold brown or black mottling in groin; posterior surfaces of thighs brown with cream-colored flecks |

| S. baudini, p. 289 | |

| Lips not barred; narrow white labial stripe present; flanks not cream-colored with bold brown or black mottling in groin; posterior surfaces of thighs variable | |

| 3 | |

| 3. | Flanks and anterior and posterior surfaces of thighs dark brown with large pale blue spots on flanks and small blue spots on thighs |

| S. cyanosticta, p. 303 | |

| Flanks cream-colored with fine black venation; posterior surfaces of thighs pale brown with or without darker flecks or small cream-colored spots | |

| S. phaeota, p. 308 | |

| 4. | Fingers having only vestige of web; diameter of tympanum two-thirds that of eye; dorsum pale yellowish tan with pair of broad dark brown stripes |

| S. puma, p. 314 | |

| Fingers about one-half webbed; diameter of tympanum about one-half that of eye; dorsum variously marked with spots or blotches | |

| 5 | |

| 5. | Snout short, truncate; vocal sacs in breeding males dark gray or brown; blue spots on flanks and posterior surfaces of thighs |

| S. sila, p. 318 | |

| Snout long, sloping, rounded; vocal sacs in breeding males white; cream-colored or pale blue flecks on flanks and posterior surfaces of thighs | |

| S. sordida, p. 323 | |

[Pg 289]

| 1. | Pond tadpoles; tail about half again as long as body; mouth anteroventral |

| 2 | |

| Stream tadpoles; tail about twice as long as body; mouth ventral | |

| 5 | |

| 2. | Labial papillae in two rows |

| 3 | |

| Labial papillae in one row | |

| 4 | |

| 3. | First upper tooth row strongly arched medially; third lower tooth row much shorter than other rows; dorsal fin deepest at about two-thirds length of tail; tail cream-colored with dense gray reticulations |

| S. puma, p. 314 | |

| First upper tooth row not arched medially; third lower tooth row nearly as long as others; dorsal fin deepest at about one-third length of tail; tail tan with brown flecks and blotches | |

| S. baudini, p. 289 | |

| 4. | Dorsal fin extending onto body |

| S. phaeota, p. 308 | |

| Dorsal fin not extending onto body | |

| S. cyanosticta, p. 303 | |

| 5. | Mouth completely bordered by two rows of papillae; inner margin of upper beak not forming continuous arch with lateral processes; red or reddish brown markings on tail |

| S. sordida, p. 323 | |

| Median part of upper lip bare; rest of mouth bordered by one row of papillae; inner margin of upper beak forming continuous arch with lateral processes; dark brown markings on tail | |

| S. sila, p. 318 | |

ACCOUNTS OF SPECIES

Smilisca baudini (Duméril and Bibron)

4798 from "Mexico;" Baudin collector]. Günther, Catalogue

Batrachia Salientia in British Museum, p. 105, 1858. Brocchi,

Mission scientifique au Mexique ..., pt. 3, sec. 2, Études sur les

batrachiens, p. 29, 1881. Boulenger, Catalogue Batrachia Salientia in

British Museum, p. 371, Feb. 1, 1882. Werner, Abhand. Zool.-Bot.

Gesell. Wien., 46:8, Sept. 30, 1896. Günther, Biologia Centrali-Americana:

Reptilia and Batrachia, p. 270, Sept. 1901. Werner, Abhand.

Konigl. Akad. Wiss. Munchen, 22:351, 1903. Cole and Barbour, Bull.

Mus. Comp. Zool., 50(5):154, Nov. 1906. Gadow, Through southern

México, p. 76, 1908. Ruthven, Zool. Jahr. 32(4):310, 1912. Decker,

Zoologica, 2:12, Oct., 1915. Stejneger and Barbour, A checklist of North

American amphibians and reptiles, p. 32, 1917. Noble, Bull. Amer. Mus.

Nat. Hist., 38(10):341, June 20, 1918. Nieden, Das Tierreich, Amphibia,

Anura I, p. 243, June, 1923. Gadow, Jorullo, p. 54, 1930. Dunn

and Emlen, Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, 84:24, March 22, 1932.

Kellogg, Bull. U. S. Natl. Mus., 160:160, March 31, 1932. Martin,

Aquarien Berlin, p. 92, 1933. Stuart, Occas. Papers Mus. Zool., Univ.

Michigan, 292:7, June 29, 1934; Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan,

29:38, Oct. 1, 1935. Gaige, Carnegie Inst. Washington, 457:293, Feb.

5, 1936. Gaige, Hartweg, and Stuart, Occas. Papers Mus. Zool. Univ.

Michigan, 360:5, Nov. 20, 1937. Smith, Occas. Papers Mus. Zool. Univ.

Michigan, 388:2, 12, Oct. 31, 1938; Ann. Carnegie Mus., 27:312, March

14, 1939. Taylor, Copeia, 2:98, July 12, 1939. Hartweg and Oliver,

Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan, 47:12, July 13, 1940. Schmidt

and Stuart, Zool. Ser. Field Mus. Nat. Hist., 24(21):238, August 30,

1941. Schmidt, Zool. Ser. Field Mus. Nat. Hist., 22(8):486, Dec. 30,

1941. Wright and Wright, Handbook of frogs and toads, Ed. 2, p. 134,

1942. Stuart, Occas. Papers Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan, 471:15, May

17, 1943. Bogert and Oliver, Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., 83(6):343,

March 30, 1945. Taylor and Smith, Proc. U. S. Natl. Mus., 95(3185): 590,

June 30, 1945. Smith, Ward's Nat. Sci. Bull., 1, p. 3, Sept., 1945. Schmidt

and Shannon, Fieldiana, Zool. Chicago Nat. Hist. Mus., 31(9):67, Feb.

[Pg 290]

20, 1947. Stuart, Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan, 69:26, June

12, 1948. Wright and Wright, Handbook of frogs and toads, Ed. 3, p.

298, 1949. Stuart, Contr. Lab. Vert. Biol. Univ. Michigan, 45:22, May,

1950. Mertens, Senckenbergiana, 33:170, June 15, 1952; Abhand.

Senckenb. Naturf. Gesell., 487:28, Dec. 1, 1952. Schmidt, A checklist

of North American amphibians and reptiles, Ed. 6, p. 69, 1953. Stuart

Contr. Lab. Vert. Biol. Univ. Michigan, 68:46, Nov. 1954. Zweifel and

Norris, Amer. Midl. Nat., 54(1):232, July 1955. Martin, Amer. Nat.,

89:356, Dec. 1955. Duellman, Copeia, 1:49, Feb. 21, 1958. Goin,

Herpetologica, 14:119, July 23, 1958. Turner, Herpetologica, 14:192,

Dec. 1, 1958. Conant, A field guide to reptiles and amphibians, p. 284,

1958. Duellman, Univ. Kansas Publ., Mus. Nat. Hist., 13(2):59, Aug.

16, 1960; Univ. Kansas Publ., Mus. Nat. Hist., 15(1): 46, Dec. 20, 1961.

Porter, Herpetologica, 18:165, Oct. 17, 1962.

1854 [Holotype.—USNM 3256 from Brownsville, Cameron County,

Texas; S. Van Vliet collector]. Baird, United States and Mexican boundary

survey, 2:29, 1859. Smith and Taylor, Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull., 33:361,

March 20, 1950. Cochran, Bull. U. S. Natl. Mus., 220:60, 1961.

1859 [nomen nudum]. Diáz de León, Indice de los batracios que se

encuentran en la República Mexicana, p. 20, June 1904.

[Holotype.—USNM 25097 from Mirador, Veracruz, México; Charles

Sartorius collector]. Smith and Taylor, Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull., 33:349,

March 20, 1950. Cochran, Bull. U. S. Natl. Mus., 220:56, 1961.

1865 [Holotype.—"skeleton in private anatomical museum of Hyrtl, Professor

of Anatomy in the University of Vienna"]. Smith and Taylor, Univ.

Kansas Sci. Bull., 33:347, March 20, 1950.

23, pt. 2:205, 1871.

Sci. Philadelphia, 8, pt. 2:107, 1876; Proc. Amer. Philos. Soc., 18:267,

August 11, 1879. Yarrow, Bull. U. S. Nat. Mus., 24:176, July 1, 1882.

Cope, Bull. U. S. Nat. Mus., 32:13, 1887; Bull. U. S. Nat. Mus., 34:379,

April 9, 1889. Dickerson, The frog book, p. 151, July, 1906. Smith and

Taylor, Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull., 33:442, March 20, 1950; Taylor, U. Kan.

Sc. Bull., 34:802, Feb. 15, 1952; Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull., 35:794, July 1,

1952. Brattstrom, Herpetologica, 8(3):59, Nov. 1, 1952. Taylor, U. Kan.

Sci. Bull., 35:1592, Sept. 10, 1953. Peters, Occas. Papers Mus. Zool.

Univ. Michigan, 554:7, June 23, 1954. Duellman, Occas. Papers Mus.

Zool. Univ. Michigan, 560:8, Oct. 22, 1954. Chrapliwy and Fugler,

Herpetologica, 11:122, July 15, 1955. Smith and Van Gelder, Herpetologica,

11:145, July 15, 1955. Lewis and Johnson, Herpetologica, 11:178,

Nov. 30, 1955. Martin, Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan, 101:53,

April 15, 1958. Stuart, Contr. Lab. Vert. Biol. Univ. Michigan, 75:17,

June, 1958. Minton and Smith, Herpetologica, 17:74, July 11, 1961. Nelson

and Hoyt, Herpetologica, 17:216, Oct. 9, 1961. Holman, Copeia, 2:256,

July 20, 1962. Stuart, Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan, 122:41,

April 2, 1963. Maslin, Herpetologica, 19:124, July 3, 1963. Holman

and Birkenholz, Herpetologica, 19:144, July 3, 1963. Duellman, Univ.

Kansas Publ. Mus. Nat. Hist., 15(5):228, Oct. 4, 1963. Zweifel, Copeia,

1:206, March 26, 1964. Duellman and Klaas, Copeia, 2:313, June 30,

1964. Davis and Dixon, Herpetologica, 20:225, January 25, 1965. Neill,

Bull. Florida State Mus., 9:89, April 9, 1965.

6313 from Panzós, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala; M. Bocourt collector];

Mission scientifique au Mexique ..., pt. 3, sec. 2, Études

sur les batrachiens, p. 34, 1881.

[Pg 291]

amphibians and reptiles, Ed. 3, p. 34, 1933. Wright and Wright, Handbook

of frogs and toads, p. 110, 1933. Stejneger and Barbour, A checklist

of North American amphibians and reptiles, Ed. 4, p. 39, 1939; A

checklist of North American amphibians and reptiles, Ed. 5, p. 49, 1943.

Smith and Laufe, Trans. Kansas Acad. Sci., 48(3):328, Dec. 19, 1945.

Peters, Nat. Hist. Misc., 143:7, March 28, 1955.

[Holotype.—UIMNH 25046 (formerly EHT-HMS 29563) from Tapachula,

Chiapas, México; A. Magaña collector]. Smith and Taylor, Bull.

U. S. Natl. Mus. 194:87, June 17, 1948; Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull, 33:326,

March 20, 1950. Smith, Illinois Biol. Mono., 32:23, May, 1964.

Nov. 15, 1947. Smith and Taylor, Bull. U. S. Natl. Mus., 194:75, June

17, 1948; Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull., 33:347, March 20, 1950. Brown,

Baylor Univ. Studies, p. 68, 1950. Smith, Smith, and Werler, Texas

Jour. Sci., 4(2):254, June 30, 1952. Smith and Smith, Anales Inst. Biol.,

22(2):561, Aug. 7, 1952. Smith and Darling, Herpetologica, 8(3):82,

Nov. 1, 1952. Davis and Smith, Herpetologica, 8(4):148, Jan. 30, 1953.

Neill and Allen, Publ. Res. Div. Ross Allen's Reptile Inst., 2(1):26, Nov.

10, 1959. Maslin, Univ. Colorado Studies, Biol. Series, 9:4, Feb. 1963.

Holman, Herpetologica, 20:48, April 17, 1964.

[Holotype.—KU 34927 from Batán, Limón Province, Costa Rica; Edward

H. Taylor collector]. Duellman and Berg, Univ. Kansas Publ. Mus.

Nat. Hist, 15(4):193, Oct. 26, 1962.

Diagnosis.—Size large ([M] 76 mm., [F] 90 mm.); skull noticeably wider than

long, having small frontoparietal fontanelle (roofed with bone in large individuals);

postorbital processes long, pointed, curving along posterior border of

orbit; squamosal large, contacting maxillary; tarsal fold strong, full length of

tarsus; inner metatarsal tubercle large, high, elliptical; hind limbs relatively

short, tibia length less than 55 per cent snout-vent length; lips strongly barred

with brown and creamy tan; flanks pale cream with bold brown or black

reticulations in groin; posterior surfaces of thighs brown with cream-colored

flecks; dorsal surfaces of limbs marked with dark brown transverse bands.

(Foregoing combination of characters distinguishing S. baudini from any other

species in genus.)

Description and Variation.—Considerable variation in size, and in certain

proportions and structural characters was observed; variation in some characters

seems to show geographic trends, whereas variation in other characters

apparently is random. Noticeable variation is evident in coloration, but this

will be discussed later.

In order to analyze geographic variation in size and proportions, ten adult

males from each of 14 samples from various localities throughout the range of

the species were measured. Snout-vent length, length of the tibia in relation

to snout-vent length, and relative size of the tympanum to the eye are the only

measurements and proportions that vary noticeably (Table 1). The largest

specimens are from southern Sinaloa; individuals from the Atlantic lowlands

of Alta Verapaz in Guatemala, Honduras, and Costa Rica are somewhat smaller,

and most specimens from the Pacific lowlands of Central America are slightly

smaller than those from the Atlantic lowlands. The smallest males are from

the Atlantic lowlands of México, including Tamaulipas, Veracruz, the Yucatán

Peninsula, and British Honduras.

[Pg 292]

| Table 1.—Geographic Variation in Size and Proportions in Males of Smilisca baudini. (Means in Parentheses Below Observed Ranges; Data Based on 10 Specimens From Each Locality.) | |||

| Locality | Snout-vent length | Tibia length/ snout-vent | Tympanum/ eye |

| Southern Sinaloa | 62.3-75.9 | 43.2-46.7 | 84.2-94.4 |

| (68.6) | (44.9) | (87.8 | |

| Ocotito, Guerrero | 55.6-64.0 | 46.1-51.2 | 66.7-82.8 |

| (58.7) | (47.8) | (74.6) | |

| Pochutla, Oaxaca | 56.1-65.1 | 44.7-49.4 | 73.0-84.2 |

| (60.2) | (47.5) | (77.4) | |

| San Salvador, El Salvador | 57.0-68.0 | 42.1-46.1 | 74.6-83.3 |

| (62.1) | (44.9) | (77.6) | |

| Managua, Nicaragua | 52.9-63.6 | 45.6-49.4 | 73.7-89.7 |

| (57.3) | (47.5) | (79.4) | |

| Esparta, Costa Rica | 57.6-66.0 | 44.6-49.3 | 65.5-83.6 |

| (61.3) | (47.3) | (75.2) | |

| Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas | 50.6-56.9 | 44.5-48.7 | 67.2-84.3 |

| (53.7) | (46.6) | (73.9) | |

| Córdoba, Veracruz | 53.8-63.4 | 43.9-48.4 | 66.1-75.9 |

| (57.5) | (45.6) | (70.0) | |

| Isla del Carmen, Campeche | 47.3-56.6 | 44.7-48.9 | 61.5-72.6 |

| (50.9) | (47.6) | (65.7) | |

| Chichén-Itzá, Yucatán | 49.6-57.1 | 45.2-53.4 | 62.7-80.7 |

| (53.8) | (49.5) | (72.6) | |

| British Honduras | 49.0-59.6 | 47.5-50.7 | 67.9-76.8 |

| (54.9) | (49.1) | (72.2) | |

| Chinajá, Guatemala | 56.8-67.6 | 47.0-51.0 | 70.0-82. |

| (63.2) | (49.5) | (73.6 | |

| Atlantidad, Honduras | 52.5-65.1 | 49.8-53.6 | 56.1-76.5 |

| (57.6) | (51.5) | (67.0) | |

| Limón, Costa Rica | 57.7-71.3 | 50.4-52.3 | 63.9-73.0 |

| (62.4) | (51.2) | (68.5) | |

The ratio of the tibia to the snout-vent length varies from 42.1 to 53.6 in

the 14 samples analyzed. The average ratio in samples from the Pacific lowlands

varies from 44.9 in Sinaloa and El Salvador to 47.8 in Guerrero; on the

Gulf lowlands of México the average ratio varies from 45.6 in Veracruz to 47.6

on Isla del Carmen, Campeche. Specimens from the Yucatán Peninsula and

the Caribbean lowlands have relatively longer legs; the variation in average

ratios ranges from 49.1 in British Honduras to 51.2 in Costa Rica and 51.5 in

Honduras.

Specimens from southern Sinaloa are outstanding in the large size of the

[Pg 293]

tympanum; the tympanum/eye ratio varies from 84.2 to 94.4 (average 87.8).

In most other samples the variation in average ratios ranges from 72.2 to 79.3,

but specimens from Veracruz have an average ratio of 70.0; Campeche, 65.7;

Honduras, 67.0; and Limón, Costa Rica, 68.5.

No noticeable geographic trends in size and proportions are evident. Specimens

from southern Sinaloa are extreme in their large size, relatively short

tibia, and large tympani, but in size and relative length of the tibia the Sinaloan

frogs are approached by specimens from such far-removed localities as

San Salvador, El Salvador, and Chinajá, Guatemala. Frogs from the Caribbean

lowlands of Honduras and Costa Rica are relatively large and have relatively

long tibiae and small tympani.

The inner metatarsal tubercle is large and high and its shape varies. The

tubercle is most pronounced in specimens from northwestern México, Tamaulipas,

and the Pacific lowlands of Central America. Possibly the large tubercle

is associated with drier habitats, where perhaps the frogs use the tubercles for

digging.

The ground color of Smilisca baudini is pale green to brown dorsally and

white to creamy yellow ventrally. The dorsum is variously marked with dark

brown or dark olive-green spots or blotches (Pl. 6A). In most specimens a

dark interorbital bar extends across the head to the lateral edges of the eyelid;

usually this bar is connected medially to a large dorsal blotch. There is no

tendency for the markings on the dorsum to form transverse bands or longitudinal

bars. In specimens from the southern part of the range the dorsal

dark markings are often fragmented into small spots, especially posteriorly.

The limbs are marked by dark transverse bands, usually three on the forearm,

three on the thigh, and three or four on the shank. Transverse bands also

are present on the tarsi and proximal segments of the fingers and toes. The

webbing on the hands and feet is pale grayish brown. The loreal region and

upper lip are pale green or tan; the lip usually is boldly marked with broad

vertical dark brown bars, especially evident is the bar beneath the eye. A

dark brown or black mark extends from the tympanum to a point above the

insertion of the forearm; in some specimens this black mark is narrow or indistinct,

but in most individuals it is quite evident. The flanks are pale gray

to creamy white with brown or black mottling, which sometimes forms reticulations

enclosing white spots. The anterior surfaces of the thighs usually are

creamy white with brown mottling, whereas the posterior surfaces of the thighs

usually are brown with small cream-colored flecks. A distinct creamy white

anal stripe usually is present. Usually, there are no white stripes on the outer

edges of the tarsi and forearms. In breeding males the throat is gray.

Most variation in coloration does not seem to be correlated with geography.

The lips are strongly barred in specimens from throughout the range of the

species, except that in some specimens from southern Nicaragua and Costa

Rica the lips are pale and in some specimens the vertical bars are indistinct.

Six specimens from 7.3 kilometers southwest of Matatán, Sinaloa, are distinctively

marked. The dorsum is uniformly grayish green with the only dorsal

marks being on the tarsi; canthal and post-tympanic dark marks absent. A

broad white labial stripe is present and interrupted by a single vertical dark

mark below the eye. A white stripe is present on the outer edge of the foot.

The flanks and posterior surfaces of the thighs are creamy white, boldly marked

with black. Two specimens from Alta Verapaz, Guatemala (CNHM 21006

[Pg 294]

from Cobán and UMMZ 90908 from Finca Canihor), are distinctive in having

many narrow transverse bands on the limbs and fine reticulations on the flanks.

Two specimens from Limón Province, Costa Rica (KU 34927 from Batán and

36789 from Suretka), lack a dorsal pattern; instead these specimens are nearly

uniform brown above and have only a few small dark brown spots on the back

and lack transverse bands on the limbs. The post-tympanic dark marks and

dark mottling on the flanks are absent. Specimens lacking the usual dorsal

markings are known from scattered localities on the Caribbean lowlands from

Guatemala to Costa Rica.

The coloration in life is highly variable; much of the apparent variation is

due to metachrosis, for individuals of Smilisca baudini are capable of undergoing

drastic and rapid change in coloration. When active at night the frogs

usually are pale bright green with olive-green markings, olive-green with brown

markings, or pale brown with dark brown markings. The dark markings on

the back and dorsal surfaces of the limbs are narrowly outlined by black. The

pale area below the eye and just posterior to the broad suborbital dark bar is

creamy white, pale green, or ashy gray in life. The presence of this mark is

an excellent character by which to identify juveniles of the species. The flanks

are creamy yellow, or yellow with brown or black mottling. In most individuals

the belly is white, but in specimens from southern El Petén and northern

Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, the belly is yellow, especially posteriorly. The iris

varies from golden bronze to dull bronze with black reticulations, somewhat

darker ventrally.

Natural History.—Throughout most of its range Smilisca baudini occurs in

sub-humid habitats; consequently the activity is controlled by the seasonal nature

of the rainfall and usually extends from May or June through September.

Throughout México and Central America the species is known to call and

breed in June, July, and August. Several records indicate that the breeding

season in Central America is more lengthy. Gaige, Hartweg, and Stuart

(1937:4) noted gravid females collected at El Recreo, Nicaragua, in August

and September. Schmidt (1941:486) reported calling males in February in

British Honduras. Stuart (1958:17) stated that tadpoles were found in mid-February,

juveniles in February and March and half-grown individuals from

mid-March to mid-May at Tikal, El Petén, Guatemala. Stuart (1961:74)

reported juveniles from Tikal in July, and that individuals were active at night

when there had been light rain in the dry season in February and March in

El Petén, Guatemala. Smilisca baudini seeks daytime retreats in bromeliads,

elephant-ear plants (Xanthosoma), and beneath bark or in holes in trees. By

far the most utilized retreat in the dry season in parts of the range is beneath

the outer sheaths of banana plants. Large numbers of these frogs were found

in banana plants at Cuautlapan, Veracruz, in March, 1956, in March and December,

1959.

Large breeding congregations of this frog are often found at the time of

the first heavy rains in the wet season. Gadow (1908:76) estimated 45,000

frogs at one breeding site in Veracruz. In the vicinity of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca,

large numbers of individuals were found around rain pools and roadside ditches

in July, 1956, and July, 1958; large concentrations were found near Chinajá,

Guatemala, in June, 1960, and near Esparta, Costa Rica in July, 1961. Usually

males call from the ground at the edge of the water or not infrequently

sit in shallow water, but sometimes males call from bushes and low trees

[Pg 295]

around the water. Stuart (1935:38) recorded individuals calling and breeding

throughout the day at La Libertad, Guatemala. Smilisca baudini usually

is absent from breeding congregations of hylids; frequently S. baudini breeds

alone in small temporary pools separated from large ponds where numerous

other species are breeding. In Guerrero and Oaxaca, México, S. baudini breeds

in the same ponds with Rhinophrynus dorsalis, Bufo marmoreus, Engystomops

pustulosus, and Diaglena reticulata, and in the vicinity of Esparta, Costa Rica,

S. baudini breeds in ponds with Bufo coccifer, Hyla staufferi, and Phrynohyas

venulosa. In nearly all instances the breeding sites of S. baudini are shallow,

temporary pools.

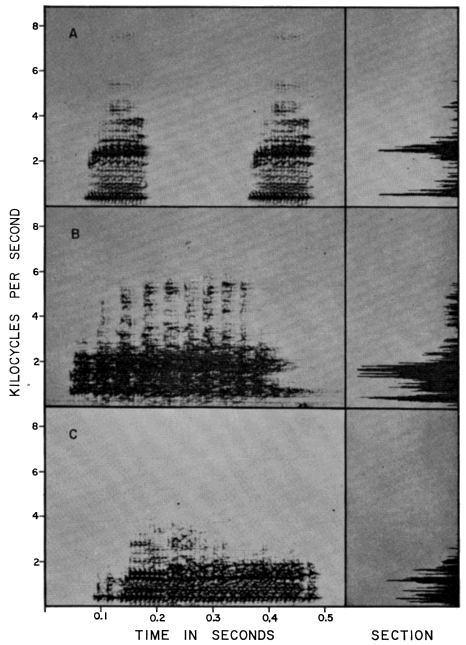

The breeding call of Smilisca baudini consists of a series of short explosive

notes. Each note has a duration of 0.09 to 0.13 seconds; two to 15 notes make

up a call group. Individual call groups are spaced from about 15 seconds to

several minutes apart. The notes are moderately high-pitched and resemble

"wonk-wonk-wonk." Little vibration is discernible in the notes, which have

140 to 195 pulses per second and a dominant frequency of 2400 to 2725 cycles

per second (Pl. 10A).

The eggs are laid as a surface film on the water in temporary pools. The

only membrane enclosing the individual eggs is the vitelline membrane. In

ten eggs (KU 62154 from San Salvador, El Salvador) the average diameter

of the embryos in first cleavage is 1.3 mm. and of the vitelline membranes,

1.5 mm. Hatchling tadpoles have body lengths of 2.6 to 2.7 mm. and total

lengths of 5.1 to 5.4 mm. The body and caudal musculature is brown; the

fins are densely flecked with brown. The gills are long and filamentous.

Growth and development of tadpoles are summarized in Table 9.

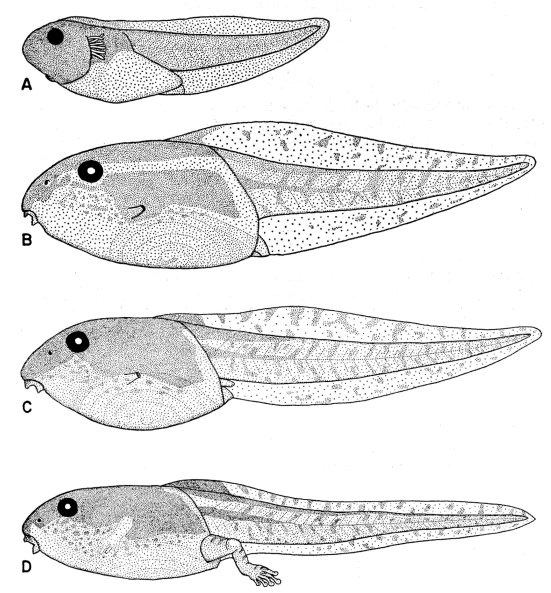

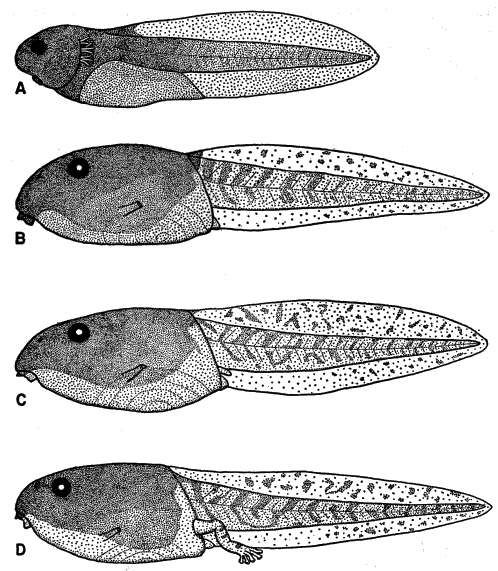

A typical tadpole in stage 30 of development (KU 60018 from Chinajá,

Alta Verapaz, Guatemala) has a body length of 8.7 mm., a tail length of

13.6 mm., and a total length of 22.3 mm.; body slightly wider than deep;

snout rounded dorsally and laterally; eyes widely separated, directed dorsolaterally;

nostril about midway between eye and tip of snout; mouth anteroventral;

spiracle sinistral, located about midway on length of body and slightly

below midline; anal tube dextral; caudal musculature slender, slightly curved

upward distally; dorsal fin extending onto body, deepest at about one-third

length of tail; depth of dorsal fin slightly more than that of ventral fin at mid-length

of tail; dorsal part of body dark brown; pale crescent-shaped mark on

posterior part of body; ventral surfaces transparent with scattered brown pigment

ventrolaterally, especially below eye; caudal musculature pale tan with

a dark brown longitudinal streak on middle of anterior one-third of tail; dorsum

of anterior one-third of tail dark brown; brown flecks and blotches on

rest of caudal musculature, on all of dorsal fin, and on posterior two-thirds of

ventral fin; iris bronze in life (Fig. 11). Mouth small; median third of upper

lip bare; rest of mouth bordered by two rows of conical papillae; lateral fold

present; tooth rows 2/3; two upper rows about equal in length; second row

broadly interrupted medially, three lower rows complete, first and second equal

in length, slightly shorter than upper rows; third lower row shortest; first upper

row sharply curved anteriorly in midline; upper beak moderately deep, forming

a board arch with slender lateral processes; lower beak more slender,

broadly V-shaped; both beaks bearing blunt serrations (Fig. 15A).

In tadpoles having fully developed mouthparts the tooth-row formula of

2/3 is invariable, but the coloration is highly variable. The color and pattern

[Pg 296]

described above is about average. Some tadpoles are much darker, such as

those from 11 kilometers north of Vista Hermosa, Oaxaca, (KU 87639-44),

3.5 kilometers east of Yokdzonot, Yucatán (KU 71720), and 4 kilometers west-southwest

Puerto Juárez, Quintana Roo, México (KU 71721), whereas others,

notably from 17 kilometers northeast of Juchatengo, Oaxaca, México (KU

87645), are much paler and lack the dark markings on the caudal musculature.

The variation in intensity of pigmentation possibly can be correlated with environmental

conditions, especially the amount of light. In general, tadpoles

that were found in open, sunlit pools are pallid by comparison with those from

shaded forest pools. These subjective comparisons were made with preserved

specimens; detailed comparative data on living tadpoles are not available.

The relative length and depth of the tail are variable; in some individuals

the greatest depth of the tail is about at mid-length of the tail, whereas in

most specimens the tail is deepest at about one-third its length. The length

of the tail relative to the total length is usually 58 to 64 per cent in tadpoles in

stages 29 and 30 of development. In some individuals the tail is about 70

per cent of the total length. On the basis of the material examined, these

variations in proportions do not show geographical trends. Probably the proportions

are a reflection of crowding of the tadpoles in the pools where they

are developing or possibly due to water currents or other environmental factors.

Stuart (1948:26) described and illustrated the tadpole of Smilisca baudini

from Finca Chejel, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. The description and figures

agree with ours, except that the first lower tooth row does not have a sharp

angle medially in Stuart's figure. He (1948:27) stated that color in tadpoles

from different localities probably varies with soil color and turbidity of water.

Maslin (1963:125) described and illustrated tadpoles of S. baudini from Pisté,

Yucatán, México. These specimens are heavily pigmented like specimens that

we have examined from the Yucatán Peninsula and from other places in the

range of the species. Maslin stated that the anal tube is median in the specimens

that he examined; we have not studied Maslin's specimens, but all tadpoles

of Smilisca that we have examined have a dextral anal tube.

Newly metamorphosed young have snout-vent lengths of 12.0 to 15.5 mm.

(average 13.4 in 23 specimens). The largest young are from La Libertad,

El Petén, Guatemala; these have snout-vent lengths of 14.0 to 15.5 mm. (average

14.5 in five specimens). Young from 11 kilometers north of Vista Hermosa,

Oaxaca, México, are the smallest and have snout-vent lengths of 12.0 to 12.5

mm. (average 12.3 in three specimens). Recently metamorphosed young

usually are dull olive green above and white below; brown transverse bands

are visible on the hind limbs. The labial markings characteristic of the adults

are represented only by a creamy white suborbital spot, which is a good diagnostic

mark for young of this species. In life the iris is pale gold.

Remarks: The considerable variation in color and the extensive geographic

distribution of Smilisca baudini have resulted in the proposal of eight specific

names for the frogs that we consider to represent one species. Duméril and

Bibron (1841:564) proposed the name Hyla baudini for a specimen (MNHN

4798) from México. Smith and Taylor (1950:347) restricted the type locality

to Córdoba, Veracruz, México, an area where the species occurs in abundance.

Baird (1854:61) named Hyla vanvlieti from Brownsville, Texas, and (1859:35)

labelled the figures of Hyla vanvlieti [= Hyla baudini] on plate 38 as Hyla

vociferans, a nomen nudum. Cope (1862:359) named Hyla muricolor from

Mirador, Veracruz, México, and (1865:194) used the name Smilisca daulinia

for a skeleton that he employed as the basis for the cranial characters diagnostic

of the genus Smilisca, as defined by him. Although we cannot be certain, Cope

apparently inadvertently used daulinia for baudini, just as he used daudinii for

baudini (1871:205). Brocchi (1877:125) named Hyla pansosana from Panzos,

Alta Verapaz, Guatemala.

young (KU 60026), snout-vent length 12.6 mm. ×23; (B) young (KU 85438),

snout-vent length 32.1 mm. ×9.

(B) Ventral. ×4.5.

(B) Dorsal view of left mandible; (C) Posterior. ×4.5.

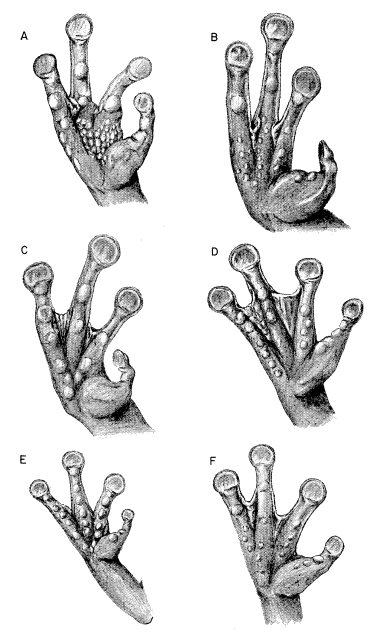

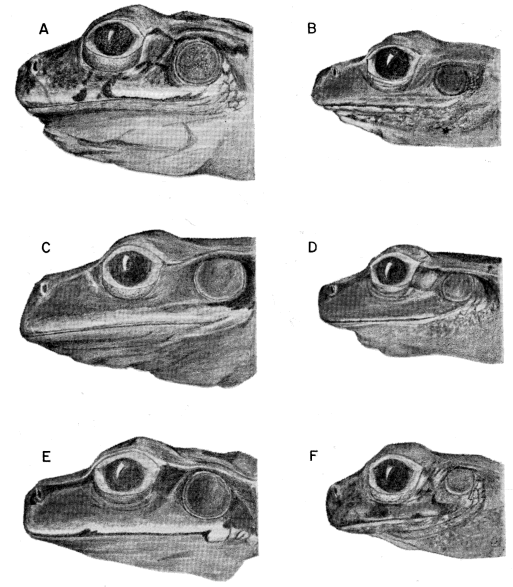

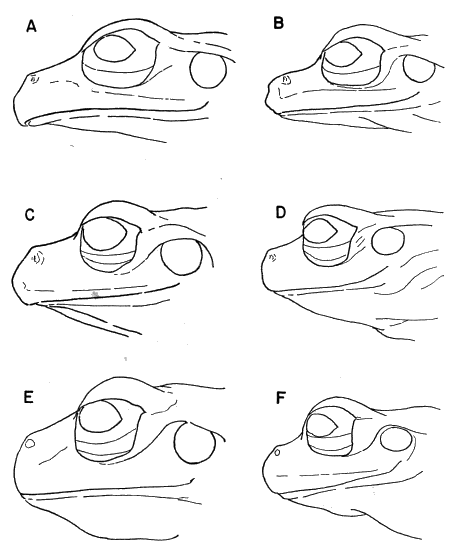

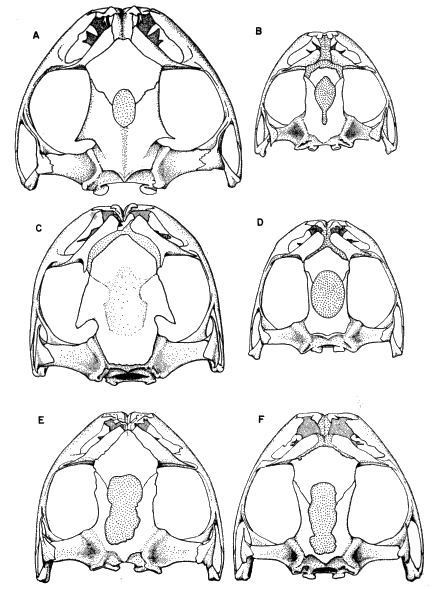

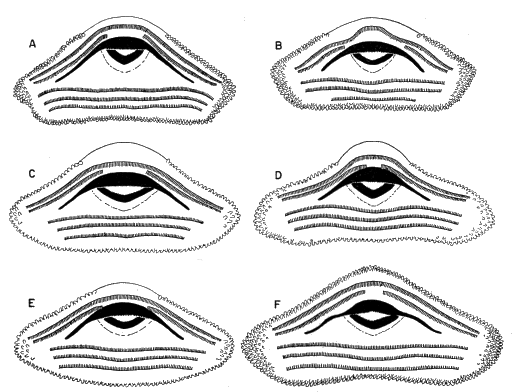

87177); (B) S. phaeota (KU 64276); (C) S. cyanosticta (KU

87199); (D) S. sordida (KU 91761); (E) S. puma (KU 91716),

and (F) S. sila (KU 77408). ×3.

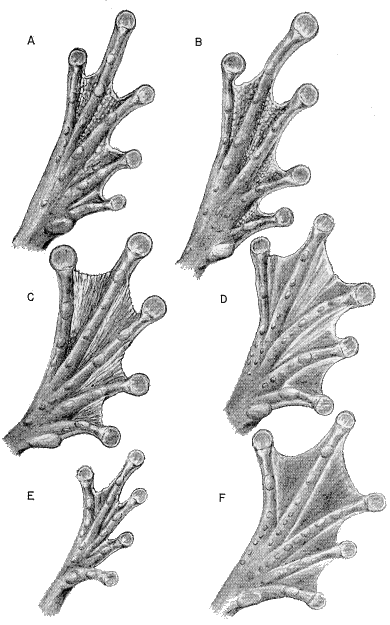

S. phaeota (KU 64276); (C) S. cyanosticta (KU 87199); (D) S. sordida

(KU 91761); (E) S. puma (KU 91716), and (F) S. sila (KU 77408). ×3.

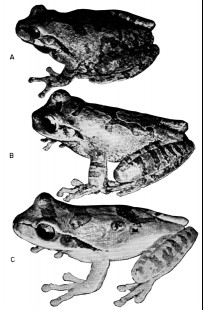

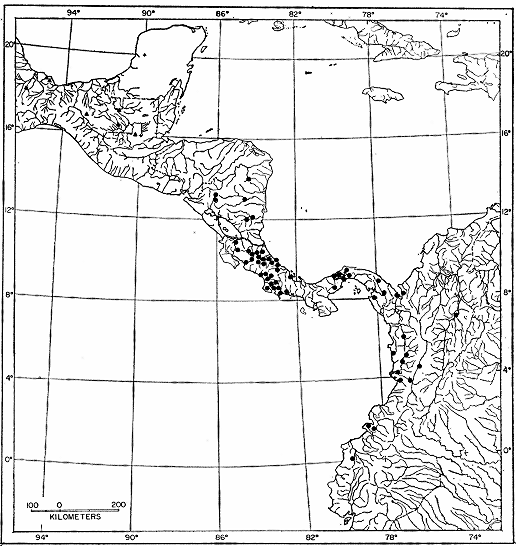

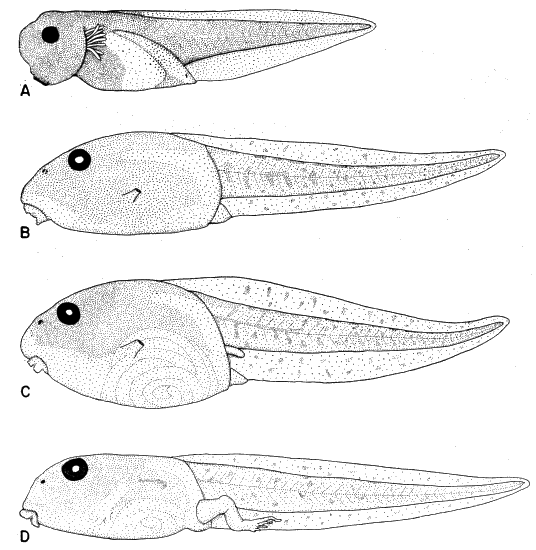

Xicotencatl, Tamaulipas, México; (B) S. cyanosticta (UMMZ 118163)

from Volcán San Martín, Veracruz, México; (C) S. phaeota (KU 64282)

from Barranca del Río Sarapiquí, Heredia Prov., Costa Rica. All approx.

nat. size.

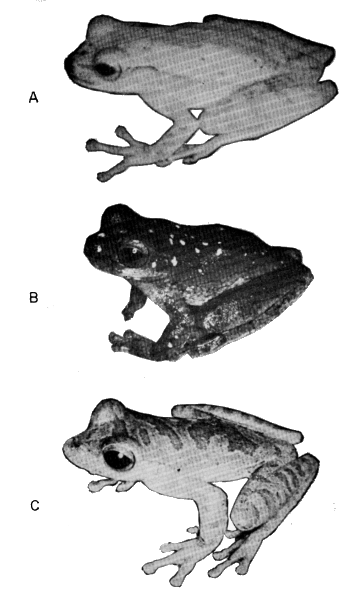

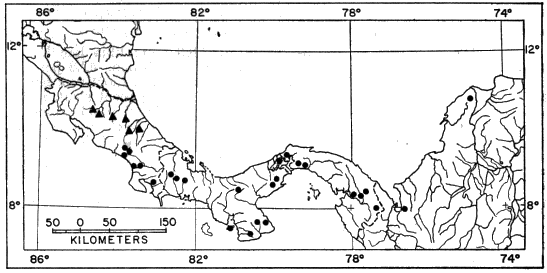

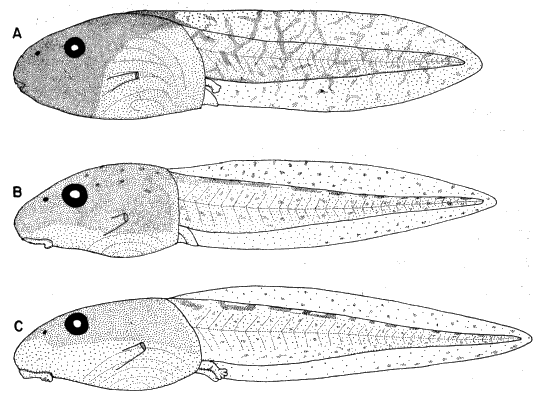

W. Puerto Viejo, Heredia Prov., Costa Rica; (B) S.

sila (KU 77407) from Finca Palosanto, 6 km. WNW El

Volcán, Chiriquí, Panamá; (C) S. sordida (KU 64257)

from 20 km. WSW San Isidro el General, San José

Prov., Costa Rica. All approx. nat. size.

Prov., Costa Rica.

Rica.

Prov., Costa Rica.

Norte, Puntarenas Prov., Costa Rica.

(KU Tape No. 74); (B) S. cyanosticta (KU Tape No. 373); (C) S. phaeota

(KU Tape No. 79).

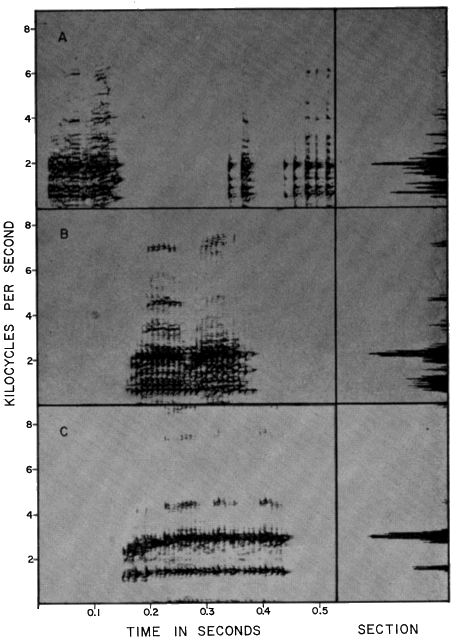

(KU Tape No. 382); (B) S. sila (KU Tape No. 385); (C) S. sordida

(KU Tape No. 398).

S. sordida (KU 91765); (C) S. phaeota (KU 64276); (D) S. puma (KU

91716); (E) S. cyanosticta (KU 87199); (F) S. sila (KU 77408). ×3.2.

[Pg 297]

Aside from the skeleton referred to as Smilisca daulinia by Cope (1865:194),

we have examined each of the types of the species synonymized with S.

baudini. All unquestionably are representatives of S. baudini.

Taylor (1942:306) named Hyla beltrani from Tapachula, Chiapas. This

specimen (UIMNH 25046) is a small female (snout-vent length, 44 mm.) of

S. baudini. Taylor (1954:630) named Hyla manisorum from Batán, Limón,

Costa Rica. The type (KU 34927) is a large female (snout-vent length,

75.3 mm.) S. baudini. In this specimen and a male from Suretka, Costa Rica,

the usual dorsal color pattern is absent, but the distinctive curved supraorbital

processes, together with other structural features, show that the two specimens

are S. baudini.

Hyla baudini dolomedes Barbour (1923:11), as shown by Dunn (1931a:413),

was based on a specimen of Smilisca phaeota from Río Esnápe, Darién,

Panamá.

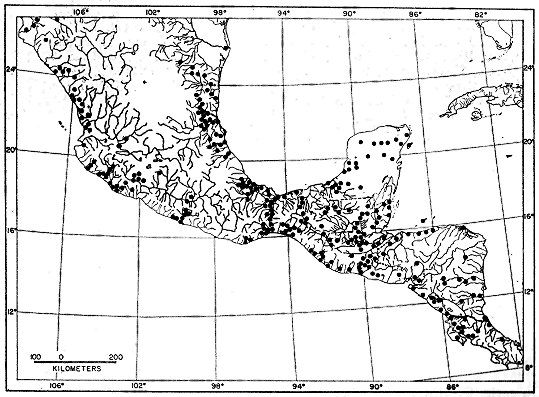

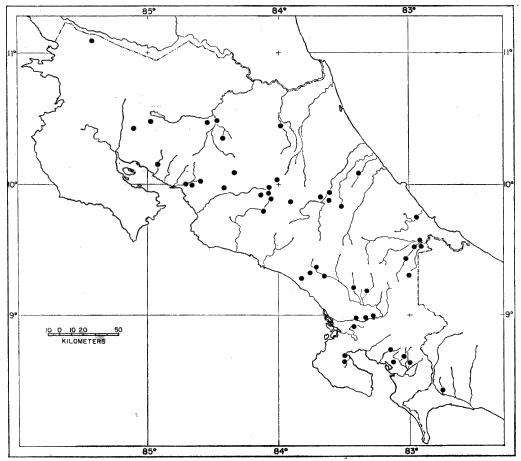

showing locality records for Smilisca baudini.

Distribution.—Smilisca baudini inhabits lowlands and foothills usually covered

by xerophytic vegetation or savannas, but in the southern part of its

range baudini inhabits tropical evergreen forest. The species ranges throughout

the Pacific and Atlantic lowlands of México from southern Sonora and the

Río Grande embayment of Texas southward to Costa Rica, where on the

Pacific lowlands the range terminates at the southern limits of the arid tropical

forest in the vicinity of Esparta; on the Caribbean lowlands the distribution

[Pg 298]

seems to be discontinuous southward to Suretka (Fig. 1). Most localities

where the species has been collected are at elevations of less than 1000 meters.

Three localities are notably higher; calling males were found at small temporary

ponds in pine-oak forest at Linda Vista, 2 kilometers northwest of

Pueblo Nuevo Solistahuacán, Chiapas, elevation 1675 meters, and 10 kilometers

northwest of Comitán, Chiapas, at an elevation of 1925 meters. Tadpoles and

metamorphosing young were obtained from a pond in arid scrub forest, 17

kilometers northeast of Juchatengo, Oaxaca, elevation 1600 meters. Stuart

(1954:46) recorded the species at elevations up to 1400 meters in the south-eastern

highlands of Guatemala.

Specimens examined.—3006, as follows: United States: Texas: Cameron

County, Brownsville, CNHM 5412-3, 6869, UMMZ 54036, USNM 3256.

Mexico: Campeche: Balchacaj, CNHM 102285, 102288, 102291, 102311,

UIMNH 30709-22, 30726; Champotón, UMMZ 73172 (2), 73176, 73180; 16

km. E Champotón, UMMZ 73181; 5 km. S Champotón, KU 71369-75; 9 km.

S Champotón, KU 71367-8; 10.5 km. S Champotón, KU 71365-6, 71722 (tadpoles),

71723 (yg.); 24 km. S Champotón, UMMZ 73177 (2); Chuina, KU 75101-3;

Ciudad del Carmen, UIMNH 30703-8; Dzibalchén, KU 75413-31; Encarnación,

CNHM 102282, 102289, 102294-5, 102300, 102306-8, 102312, 102314,

102316-7, 102319, 102322, UIMNH 30727-40, 30836-7; 1 km. W Escárcega,

KU 71391-6; 6 km. W Escárcega, KU 71397-403; 7.5 km. W Escárcega, KU

71376-89; 14 km. W Escárcega, KU 71390; 13 km. W, 1 km. N Escárcega,

KU 71404; 3 km. N Hopelchén, KU 75410-11; 2 km. NE Hopelchén, KU

75412; Matamoras, CNHM 36573; Pitál, UIMNH 30741; 1 km. SW Puerto

Real, Isla del Carmen, KU 71345-64; San José Carpizo, UMMZ 99879; Tres

Brazos, CNHM 102284, UIMNH 30723-5; Tuxpeña Camp, UMMZ 73239.

Chiapas: Acacoyagua, USNM 114487-92; 2 km. W Acacoyagua, USNM

114493-4; 5 km. E Arroyo Minas, UIMNH 9533-7; Berriozabal, UMMZ

119186 (7); Chiapa de Corzo, UMMZ 119185 (2); Cintalapa, UIMNH 50077;

Colonia Soconusco, USNM 114495-9; 5 km. W Colonia Soconusco, UMMZ

87885 (7); Comitán, UMMZ 94438; 10 km. NW Comitán, KU 57185; El

Suspiro, UMMZ 118819 (11); Escuintla, UMMZ 88271 (7), 88278, 88327,

109233; 6 km. NE Escuintla, UMMZ 87856 (26); 3 km. E Finca Juárez,

UIMNH 9538; Finca Prussia, UMMZ 95167; Honduras, UMMZ 94434-7;

La Grada, UMMZ 87862; 21 km. S La Trinitaria, UIMNH 9540-1; 14.4 km.

SW Las Cruces, KU 64239-44; Palenque, UIMNH 49286, USNM 114473-84;

2 km. NW Pueblo Nuevo Solistahuacán, KU 57182-4, UMMZ 119948 (8),

121514; 1.3 km. N Puerto Madero, KU 57186-9; 4 km. N Puerto Madero,

KU 57190-1; 8 km. N Puerto Madero, UMMZ 118379 (2); 12 km. N Puerto

Madero, KU 57192; 17.6 km. N Puerto Madero, UMMZ 118378; Rancho

Monserrata, UIMNH 9531-2, UMMZ 102266-7; Region Soconusco, UIMNH

33542-56; San Bartola, UIMNH 9519-30; San Gerónimo, UIMNH 30804;

San Juanito, USNM 114485-6; San Ricardo, CNHM 102406; Solosuchiapa,

KU 75432-3; Tapachula, CNHM 102208, 102219, 102239, 102405, UIMNH

25046, 30802-3; Tonolá, AMNH 531, CNHM 102232, 102416, UIMNH

30805-9, USNM 46760; Tuina, KU 41593 (skeleton); Tuxtla Gutierrez, CNHM

102231, 102248; 6 km. E Tuxtla Gutierrez, UIMNH 9539; 10 km. E Tuxtla

Gutierrez, UMMZ 119949.

Chihuahua: 2.4 km. SW Toquina, KU 47226-7; Riito, KU 47228.

Coahuila: mountain near Saltillo, UIMNH 30833-4.

Colima: No specific locality, CNHM 1632; Colima, AMNH 510-11; Hacienda

Albarradito, UMMZ 80029 (2); Hacienda del Colomo, AMNH 6208; Los

Mezcales, UMMZ 80028; Manzanillo, AMNH 6207, 6209; Paso del Río,

CNHM 102207, 102229-30, UIMNH 30819-21, UMMZ 110875 (3); Periquillo,

UMMZ 80025 (3), 80026 (14); 1.6 km. SW Pueblo Juárez, UMMZ 115564;

Queseria, CNHM 102204, 102216-7, 102224, UIMNH 30816-8, UMMZ 80023

(7), 80024 (7); Santiago, UMMZ 80027; 7.2 km. SW Tecolapa, UMMZ 115184.

[Pg 299]

Guerrero: Acahuizotla, UF 1338 (2), 1339-40, UMMZ 119182 (2), 119184;

3 km. S Acahuizotla, KU 87183-7; Acapulco, AMNH 55276, UMMZ 121879

(4), USNM 47909; 3 km. N Acapulco, UMMZ 110127; 8 km. NW Acapulco,

UF 11203 (7); 27 km. NE Acapulco, UIMNH 26597-610; Agua del Obispo,

CNHM 102214, 102290, 102293, 102310, 102413, KU 60413, 87180-2, UIMNH

30764-6; Atoyca, KU 87175-8; Buena Vista, CNHM 102279, 102304, 102313,

102315, UIMNH 30774; Caculutla, KU 87179; 20 km. S Chilpancingo, CNHM

102242, 102401, 102410-1, 102415; Colonia Buenas Aires, UMMZ 119189;

El Limoncito, CNHM 102292, 102303, 102321, 102414; El Treinte, CNHM

102212, 102221, 102237, 102240-1, UIMNH 30783-5, USNM 114508-10;

Laguna Coyuca, UMMZ 80960 (2); 3 km. N Mazatlán, UIMNH 30777-9; 9 km.

S Mazatlán, CNHM 102209, 102215, 102234, 102246, UIMNH 30781-2;

Mexcala, CNHM 102399, 102403, 102409, 106539-40, UIMNH 30775-6;

Ocotito, KU 60414-23; 5.4 km. N Ocotito, UMMZ 119181 (4); 1.6 km. N

Organos, UIMNH 30752-63; Palo Blanco, CNHM 102283, 102286, 102305,

102320, 102404, UIMNH 30767-70; Pie de la Cuesta, AMNH 55275, 59202-5;

Puerto Marquéz, AMNH 59200-1 (13); 5.6 km. S San Andreas de la Cruz,

KU 87173-4; San Vincente, KU 87172; Zaculapán, UMMZ 119183.

Hidalgo: Below Tianguistengo, CNHM 102318.

Jalisco: Atenqueque, KU 91435-6; 5 km. NE Autlán, UIMNH 30810; 5

km. E Barro de Navidad, UMMZ 110900; Charco Hondo, UMMZ 95247;

Puerto Vallarta, UIMNH 41346; between La Huerta and Tecomates, KU

91437; 3 km. SE La Resolana, KU 27619, 27620 (skeleton); 11 km. S, 1.6 km.

E Yahualica, KU 29039; Zapotilitic, CNHM 102238.

Michoacán: Aguililla, UMMZ 119179 (5); Apatzingán, CNHM 38766-90,

KU 69101 (skeleton); 7 km. E Apatzingán, UMMZ 112843; 11 km. E Apatzingán,

UMMZ 112841 (3); 27 km. S Apatzingán, KU 37621-3; 1.6 km. N

Arteaga, UMMZ 119180; Charapendo, UMMZ 112840; Coahuayana, UMMZ

104458; El Sabino, CNHM 102205-6, 102210-1, 102220, 102228, 102233,

UIMNH 30822-3; La Placita, UMMZ 104456; La Playa, UMMZ 105163; 30

km. E Nueva Italia, UMMZ 120255 (2); 4 km. S Nueva Italia, UMMZ 112842;

Ostula, UMMZ 104457 (4); Salitre de Estopilas, UMMZ 104459; San José de la

Montaña, UMMZ 104461 (2); 11 km. S Tumbiscatio, KU 37626; 12 km. S

Tzitzio, UMMZ 119178.

Morelos: 3.5 km. W Cuautlixco, KU 87188-90; 1 km. NE Puente de Ixtla,

KU 60393-4; 20 km. S Puente de Ixtla, CNHM 102400, UIMNH 30832;

Tequesquitengo, AMNH 52036-9.

Nayarit: 3 km. S Acaponeta, UMMZ 123030 (4); 56 km. S Esquinapa

(Sinaloa), KU 73909; Jesús María, AMNH 58239; San Blas, KU 28087, 37624,

62360-2, USNM 51408; 8.6 km. E San Blas, UMMZ 115185; Tepic, UIMNH

30812-5; 4 km. E Tuxpan, KU 67786; 11 km. SE Tuxpan, UIMNH 7329-31,

7335-59.

Nuevo León: Galeana, CNHM 34389; Salto de Cola de Caballo, CNHM

30628-31, 30632 (40), 30633-7, 34454-67.

Oaxaca: 11 km. S Candelaria, UIMNH 9515-8; Cerro San Pedro, 24 km.

SW Tehuantepec, UMMZ 82156; Chachalapa, KU 38199; 8 km. S Chiltepec,

KU 87191; 12 km. S Chivela, UMMZ 115182; Coyul, USNM 114512; Garza

Mora, UIMNH 40967-8; Juchatengo, KU 87193; 17 km. NE Juchatengo, KU

87645 (tadpoles), 87646 (young); Juchitán, USNM 70400; Lagartero, UIMNH

9514; Matías Romero, AMNH 52143-5; 25 km. N Matías Romero, KU 33822-8;

7 km. S Matías Romero, UIMNH 42703; Mirador, AMNH 6277, 13832-9,

13842-55; Mira León, 1.6 km. N Huatulco, UIMNH 9503-4; Mixtequillo,

AMNH 13924; Pochutla, KU 57167-81, UIMNH 9505-13; Quiengola, AMNH

51817, 52146; Río del Corte, UIMNH 48677; Río Mono Blanco, UIMNH

36831; Río Sarabia, 5 km. N Sarabia, UMMZ 115180 (4); 2.5 km. N Salina

Cruz, KU 57165-6; San Antonio, UIMNH 37286; 5 km. NNW San Gabriel

Mixtepec, KU 87192; San Pedro del Istmo, UIMNH 37197; Santo Domingo,

USNM 47120-2; 3.7 km. N Sarabia, UMMZ 115181 (3); Tapanatepec, KU

37793 (skeleton), 37794, UIMNH 9542, UMMZ 115183; between Tapanatepec

[Pg 300]

and Zanatepec, UIMNH 42704-25; Tecuane, UMMZ 82163 (3); Tehuantepec,

AMNH 52625, 52639, 53470, UMMZ 82157-8, 82159 (9), 82160 (4), 82161

(8), 82162 (12), 112844-5, 118703, USNM 10016, 30171-4, 30188; 4.5 km. W

Tehuantepec, KU 59801-12 (skeletons), 69102-3 (skeletons); 10 km. S Tehuantepec,

KU 57163-4; Temazcal, USC 8243 (3); 3 km. S Tolocita, KU 39666-9;

Tolosa, AMNH 53605; Tuxtepec, UMMZ 122098 (2); 2 km. S Valle Nacional,

KU 87194-5; 11 km. N Vista Hermosa, KU 87196, 87639-41 (tadpoles), 87642-3

(young), 87644 (tadpoles); Yetla, KU 87197.

Puebla: 16 km. SW Mecatepec (Veracruz), UIMNH 3657-8; San Diego,

AMNH 57714, USNM 114511; Vegas de Suchil, AMNH 57712; Villa Juárez,

UF 11205.

Quintana Roo: Cóba, CNHM 26937; Esmeralda, UMMZ 113551; 4 km.

NNE Felipe Carrillo Puerto, KU 71417-8; Pueblo Nuevo X-Can, KU 71405;

10 km. ENE Pueblo Nuevo X-Can, KU 71406; 4 km. WSW Puerto Juárez,

KU 71407-11, 71721 (tadpoles); 12 km. W Puerto Juárez, KU 71412-6; San

Miguel, Isla de Cozumel, UMMZ 78542 (6), 78543 (10), 78544 (2); 3.5 km. N

San Miguel, Isla de Cozumel, KU 71419-22; 10 km. E San Miguel, Isla de

Cozumel, UMMZ 78541; Telantunich, CNHM 26950.

San Luis Potosí: Ciudad Valles, AMNH 57776-81 (12), CNHM 37193,

102297, KU 23705; 21 km. N Ciudad Valles, UMMZ 118377; 6 km. E Ciudad

Valles, UF 3524; 24 km. E Ciudad Valles, UF 7340 (2); 5 km. S Ciudad Valles,

UIMNH 30751; 16 km. S Ciudad Valles, AMNH 52953; 30 km. S Ciudad

Valles, CNHM 102394, 102402, 102412, UIMNH 30749-50; 63 km. S Ciudad

Valles, UIMNH 19247-58; Pujal, UMMZ 99872 (2); Río Axtla, near Axtla,

AMNH 53211-5, 59516, KU 23706; Tamazunchale, AMNH 52675, CNHM

39621-2, 102226, 102281, UF 7615 (2), UIMNH 26596, UMMZ 99506 (9),

118701 (2), USNM 114468; 17 km. N Tamazunchale, UIMNH 3659; 2.4 km. S

Tamazunchale, AMNH 57743; 17 km. E Tamuin, UF 11202 (2); Xilitla,

UIMNH 19259-60.

Sinaloa: 8 km. N. Carrizalejo, KU 78133; 4 km. NE Concordia, KU 73914;

5 km. SW Concordia, KU 75438-9; 6 km. E Cosalá, KU 73910; Costa Rica,

16 km. S. Culiacán, UIMNH 34887-9; 51 km. SSE Culiacán, KU 37792; El

Dorado, KU 60392; 1.6 km. NE El Fuerte, CNHM 71468; Isla Palmito del

Verde, middle, KU 73916-7; 21 km. NNE Los Mochis, UIMNH 40536-7;

Matatán, KU 73913; 7.3 km. SW Matatán, KU 78464, 78466-70; Mazatlán,

AMNH 12562, UMMZ 115197 (3); 57 km. N Mazatlán, UIMNH 38364;

Plomosas, USNM 47439-40; Presidio, UIMNH 30811, USNM 14082; Rosario,

KU 73911-2; 5 km. E Rosario, UIMNH 7360-76; 8 km. SSE Rosario, KU 37625;

5 km. SW San Ignacio, KU 78465; 1.6 km. ENE San Lorenzo, KU 47917-24;

Teacapán, Isla Palmito del Verde, KU 73915; 9.6 km. NNW Teacapán, KU

91410; Villa Unión, KU 78471; 9 km. NE Villa Unión, KU 75434-7; 1 km.

W Villa Unión, AMNH 59284.

Sonora: Guiracoba, AMNH 51225-38 (25).

Tabasco: 4 km. NE Comalcalco, AMNH 60313; Teapa, UMMZ 119943;

5 km. N Teapa, UMMZ 119940, 119944, 122997 (2); 10 km. N Teapa, UMMZ

119187, 119188 (2); 13 km. N Teapa, UMMZ 119941 (2), 119945 (3), 120254

(2); 21 km. N Teapa, UMMZ 119942, 119947; 29 km. N Teapa, UMMZ 119946

(11); Tenosique, USNM 114505-7.

Tamaulipas: Acuña, UMMZ 99864; 5 km. S Acuña, UMMZ 101180; 13

km. N Antiguo Morelos, UIMNH 40532-5; 3 km. S Antiguo Morelos, UF

11204; 3 km. NE Chamal, UMMZ 102867; 1.6 km. E Chamal, UMMZ 110734;

Ciudad Mante, UMMZ 80957, 80958 (3), 106400 (3); 16 km. N Ciudad Victoria,

CNHM 102408; 34 km. NE Ciudad Victoria, KU 60395-411; 8.8 km. S Ciudad

Victoria, UIMNH 19261-3; 11 km. W Ciudad Victoria, UIMNH 30924; 16

km. W Ciudad Victoria, UIMNH 30825; 3 km. W El Carizo, UMMZ 111279;

Gómez Farías, UMMZ 110837-8; 8 km. NE Gómez Farías, UMMZ 102265,

102916 (4), 102917, 104110 (5), 105493, 110836 (2), 111274-7; 8 km. NW

Gómez Farías, UMMZ 101178 (7), 101179 (3), 101362-3, 101364 (2), 108799

(2), 110129, 111278, 111280; 8 km. W Gómez Farías, UMMZ 102859 (2); 16

km. W Gonzales, KU 37795-6; Jiménez, KU 60412; La Clementina, 6 km.

[Pg 301]

W Forlan, USNM 106244; Limón, UIMNH 30831; Llera, USNM 140137-40;

3 km. E Llera, UIMNH 16858; 21 km. S Llera, UIMNH 30828-9; 23 km.

S Llera, UIMNH 30830; 11 km. SW Ocampo, UMMZ 118956; 22 km. W, 5 km.

S Piedra, KU 37568-71; Rio Sabinas, UMMZ 97976; 5 km. W San Gerardo,

UMMZ 110733 (2); Santa Barbara, UMMZ 111272-3; Villagrán, CNHM 102280,

102287, 102299, 102309, UIMNH 30826-7; 1.7 km. W Xicotencatl, UMMZ

115179.

Veracruz: 1.6 km. NW Acayucan, UMMZ 115189; 28.5 km. SE Alvarado,

UMMZ 119933; 2.4 km. SSW Amatitlán, UMMZ 115195; Barranca Metlac,

UIMNH 38365; Boca del Río, UIMNH 26619-30, UMMZ 74954 (9); 16 km.

S Boca del Río, UIMNH 26631; between Boca del Río and Anton Lizardo,

UIMNH 42701; Canadá, CNHM 102397; Catemaco, UMMZ 118702 (4);

Ciudad Alemán, UMMZ 119608 (3); Córdoba, CNHM 38665-7, USNM 30410-3;

5.2 km. ESE Córdoba, KU 71423-35, 89924 (skeleton); 7 km. ESE Córdoba,

UMMZ 115176 (4); Cosamaloapan, UMMZ 115193 (2); Coyame, UIMNH

36853-6, 38366, UMMZ 111461 (3), 111462-3; 1 km. SE Coyame, UMMZ

121202 (3); Cuatotolapam, UMMZ 41625-39; Cuautlapan, CNHM 38664,

70591-600, 102218, 102398, KU 26300, 26302, 26309, 26312-3, 26315-6, 26321,

26336, 26339, 26347 (skeleton), 26354, 55614-21 (skeletons), UIMNH 11236-67,

11269-71, 11273, 26611-8, 30792-5, UMMZ 85466 (6), 115173 (25), 115175

(7), USNM 114433-57; Dos Ríos, CNHM 39623; 5 km. ENE El Jobo, KU

23843, 23845, 23847; 6.2 km. E Encero, UIMNH 30835; Escamilo, CNHM

102298, UIMNH 30788; 1 km. N Fortín, UF 11201; 4 km. SW Huatusco,

UMMZ 115177; 1 km. SW Huatusco, UMMZ 123119; 10 km. SE Hueyapan,

UMMZ 115190; 20 km. S Jesús Carranza, KU 23844, 23846, 27399; 38 km.

SE Jesús Carranza, KU 23417; Laguna Catemaco, UMMZ 119932 (62); 1.6

km. N La Laja, UIMNH 3651; La Oaxaqueña, AMNH 43930-1; 17 km. E

Martínez de la Torre, UIMNH 36630-2; 6.2 km. W Martínez de la Torre,

UIMNH 3652-4; Minatitlán, AMNH 52141-2; Mirador, USNM 25097-8,

115178; 6 km. S Monte Blanco, UF 11200 (4); 21 km. E Nanchital, UMMZ

123004; 2 km. S Naranja, UMMZ 115188 (3); 1.6 km. NE Novillero, UMMZ

115194 (2); 3 km. NE Novillero, UMMZ 115196; 5.2 km. NE Novillero,

UMMZ 115192 (4); 6 km. NE Novillero, UMMZ 115191; 5 km. N Nuevo

Colonia, UMMZ 105066; Orizaba, USNM 16563-6; 4 km. NE Orizaba, UMMZ

120251 (2); Panuco, UMMZ 118922; Paraje Nuevo, UMMZ 85465 (2), 85467

(35), 85468 (36); Paso del Macho, UIMNH 49281; Paso de Talaya, Jicaltepec,

USNM 32365, 84420; Pérez, CNHM 1686 (5); 20 km. N Piedras Negras, Río

Blanco, KU 23708; Plan del Río, KU 26310, 26333-5, 26345, 26354, UMMZ

102069, 102070 (5); Potrero, UIMNH 49282-5, UMMZ 88799, 88805, 88806

(2), USNM 32391-5; Potrero Viejo, CNHM 102296, KU 26301, 26304-5,

26307-8, 26311, 26317-20, 26323-25, 26326-8 (skeletons), 26329-31, 26332

(skeleton), 26337-8, 26340-4, 26346, 26348, 26351, 26353, 27400-12, UIMNH

30800, UMMZ 88800 (2), 88802 (15), 88803 (9), 88804, USNM 114458-67; 5

km. S Potrero Viejo, KU 26303, 26314, 26322; Puente Nacional, UIMNH

21783-8; 3 km. N Rinconada, UMMZ 122099 (5); Río de las Playas, USNM

118635-6; Río Seco, UMMZ 88801 (9); Rodriguez Clara, CNHM 102225; San

Andrés Tuxtla, CNHM 102213, 102222, 102227, 102247, UIMNH 30789-91;

10 km. NW San Andrés Tuxtla, UMMZ 119935; 13.4 km. NW San Andrés

Tuxtla, UMMZ 119939 (2); 19.8 km. NW San Andrés Tuxtla, UMMZ 119938;

27.2 km. NW San Andrés Tuxtla, UMMZ 119936 (6); 48 km. NW San Andrés

Tuxtla, UMMZ 119937; 4 km. W San Andrés Tuxtla, UMMZ 115187; 37.4

km. S San Andrés Tuxtla, UMMZ 119934 (12); 15 km. ESE San Juan de la

Punta, KU 23707; San Lorenzo, USNM 123508-12; 3 km. SW San Marcias

KU 23841; 1.5 km. S Santa Rosa, UIMNH 42702; 2 km. S Santiago Tuxtla,

UMMZ 121201 (4); Sauzel, UMMZ 121239; 14 km. E Suchil, UIMNH 46880;

15 km. S Tampico (Tamaulipas), UMMZ 103322 (4); 4 km. N Tapalapan,

UMMZ 115186 (2); Tecolutla, UIMNH 42677-700; 16 km. NW Tehuatlán,

UIMNH 3660-3; 5 km. S Tehuatlán, KU 23842; Teocelo, KU 26306; Tierra

Colorado, CNHM 102393, 102395-6, UIMNH 30789-91; Veracruz, AMNH

6301-4, 59398-402, UIMNH 30801, UMMZ 115174, 122060 (2); 24 km. W

Veracruz, CNHM 104570-2.

[Pg 302]

Yucatán: No specific locality, CNHM 548, 49067, USNM 32298; Chichén-Itzá,

CNHM 20636, 26938-49, 36559-62, UIMNH 30742-6, UMMZ 73173

(6), 73174 (14), 73175 (14), 73178-9, 76171, 83107 (2), 83108, 83109 (2), 83915

(30), USNM 72744; 9 km. E Chichén-Itzá, KU 71438-9; 12 km. E Chichén-Itzá,

KU 71440; Mérida, CNHM 40659-66, UIMNH 30747-8, UMMZ 73182;

6 km. S Mérida, KU 75194; 8.8 km. SE Ticul, UMMZ 114296; Valladolid,

CNHM 26934-6; Xcalah-op, CNHM 53906-14; 3.5 km. E Yokdzonot, KU

71441-3, 71720 (tadpoles).

British Honduras: Belize, CNHM 4153, 4384-5, 4387, UMMZ 75310,

USNM 26065; Bokowina, CNHM 49064-5; Cocquercote, UMMZ 75331 (2);

Cohune Ridge, UMMZ 80738 (15); Double Falls, CNHM 49066; El Cayo,

UMMZ 75311; 6 km. S El Cayo, MCZ 37856; Gallon Jug, MCZ 37848-55;

Manatee, CNHM 4264-7; Mountain Pine Ridge, MCZ 37857-8; San Augustin,

UMMZ 80739; San Pedro, Columbia, MCZ 37860-2; Valentin, UMMZ 80735

(4), 80736 (2), 80737 (2); 5 km. S Waha Loaf Creek, MCZ 37859.

Guatemala: Alta Verapaz: 5.1 km. NE Campur, KU 68464 (tadpoles),

67465 (young); 28.3 km. NE Campur, KU 64203-22, 68183-4 (skeletons);

Chamá, MCZ 15792-3, UMMZ 90895 (7), 90896 (5), 90897 (29), 90898 (12),

90899; Chinajá, KU 55939-41, 57193-8, 60018-20 (tadpoles), 60021 (eggs),

60022 (tadpoles); Cobán, CNHM 21006; Cubilquitz, UMMZ 90902 (10); Finca

Canihor, UMMZ 90908; Finca Chicoyou, KU 57246-8, 60026 (young), 64202,

68466-7 (tadpoles); Finca Los Alpes, KU 64197-201, 68463 (tadpoles); Finca

Los Pinales, UMMZ 90903 (2); Finca Tinajas, BYU 16031; Finca Volcán,

UMMZ 90905 (4), 90906-7; Panzos, MNHN 6313, UMMZ 90904; Samac,

UMMZ 90900; Samanzana, UMMZ 90901 (6).

Baja Verapaz: Chejel, UMMZ 90909 (7), 90910 (3); San Gerónimo, UMMZ

84076 (16).

Chiquimula: 1.6 km. SE Chiquimula, UMMZ 98112; Esquipulas, UMMZ

106793 (28).

El Petén: 20 km. NNW Chinajá (Alta Verapaz), KU 57199-240; Flores,

UMMZ 117985; La Libertad, KU 60024 (young), UMMZ 75313-20, 75323

(2), 75324 (7), 75325 (13), 75326 (2), 75327 (11), 75328 (12), 75329 (2); 3 km.

SE La Libertad, KU 57243-4; 13 km. S La Libertad, MCZ 21458 (2); Pacomon,

USNM 71334; Piedras Negras, USNM 114469-71; Poptún, UMMZ 120475;

Poza de la Jicotea, USNM 114672; Ramate-Yaxha trail, UMMZ 75321; Río de

la Pasión between Sayaxché and Subín, KU 57151; Río San Román, 16 km.

NNW Chinajá (Alta Verapaz), KU 55942-6; Sacluc, USNM 25131; Sayaxché,

KU 57144-5; Tikal, UMMZ 117983 (7), 117984 (5), 117993 (5), 120474 (5);

Toocog, KU 57241-2, 60023 (young), 60025 (young); Uaxactún, UMMZ

70401-3; Yaxha, UMMZ 75322; 19 km. E Yaxha, UMMZ 75330 (4).

El Quiché: Finca Tesoro, UMMZ 89166 (3), 90549 (tadpoles).

Escuintla: Río Guacalate, Masagua, USNM 125239; Tiquisate, UMMZ

98262 (7).

Guatemala: 16 km. NE Guatemala, KU 43545-53.

Huehuetenango: Finca San Rafael, 16 km. SE Barillas, CNHM 40912-6;

45 km. WNW Huehuetenango, KU 64223-4; Jacaltenango, UMMZ 120080

(6), 120081 (14), 120082 (13).

Izabál: 2 km. SW Puerto Matías de Gálvez, KU 60027-8 (tadpoles); Quiriguá,

CNHM 20587, UMMZ 70060.

Jalapa: Jalapa, UMMZ 98109, 106792 (11).

Jutiapa: Finca La Trinidad, UMMZ 107728 (10); Jutiapa, UMMZ 106789;

1.6 km. SE Mongoy, KU 43069; Santa Catarina Mita, UMMZ 106790.

Progreso: Finca Los Leones, UMMZ 106791.

Quetzaltenango: Coatepeque, AMNH 62204.

Retalhueleu: Casa Blanca, UMMZ 107725 (18); Champerico, UMMZ

107726 (3).

San Marcos: Talisman Bridge, USNM 128056-7.

[Pg 303]

Santa Rosa: Finca La Guardiana, UMMZ 107727 (6); Finca La Gloria,

UMMZ 107724 (6); 1.6 km. WSW El Molino, KU 43065-8.

El Salvador: La Libertad: 16 km. NW Santa Tecla, KU 43542-4.

Morazán: Divisadero, USNM 73284. San Salvador: San Salvador, CNHM

65087-99, KU 61955-88, 62138-9 (skeletons), 62154 (eggs), 62155-60 (tadpoles),

68462 (tadpoles), UMMZ 117586 (3), 118380 (3), USNM 140278.

Honduras: State unknown: Guaimas, UMMZ 58391. Atlantidad: Isla de

Roatán, CNHM 34551-4; La Ceiba, USNM 64985, 117589-91; Lancetilla,

MCZ 16207-11; Tela, MCZ 15774-5, 28080, UMMZ 58418, USNM 82173-4.

Choluteca: 1.5 km. NW Choluteca, KU 64228-32; 10 km. NW Choluteca, KU

64233; 10 km. E Choluteca, KU 64226-7; 12 km. E Choluteca, KU 64225; 5

km. S Choluteca, USC 2700 (2). Colón: Bambú, UF 320; Belfate, AMNH

45692-5; Patuca, USNM 20261. Comayagua: La Misión, 3.5 leagues N

Siguatepeque, MCZ 26424-5. Copán: Copán, UMMZ 83026 (2). Cortés:

Cofradía, AMNH 45345-6; Hacienda Santa Ana, CNHM 4724-31; Lago de

Yojoa, MCZ 26410-1; Río Lindo, AMNH 54972. El Paraiso: El Volcán, MCZ

26436. Francisco Morazán: Tegucigalapa, BYU 18301-4, 18837-41, MCZ

26395-7, USNM 60499. Gracias A Dios: Río Segovia, MCZ 24543. Santa

Barbara: Santa Barbara, USNM 128062-5.

Nicaragua: Chinandega: 4 km. N, 2 km. W Chichigalpa, KU 85385;

Chinandega, MCZ 2632; Río Tama, USNM 40022; San Antonio, KU 84944-9

(skeletons), 85386-403. Chontales: 1 km. NE Acoyapa, KU 64234. Estelí:

Finca Daraili, 5 km. N, 15 km. E Condega, KU 85404-8; Finca Venecia, 7

km. N, 16 km. E Condega, KU 85409. León: 1.6 km. ENE Poneloya, KU

43084-5. Managua: Managua, USNM 79989-90; 8 km. NW Managua, KU

43094-110; 20 km. NE Managua, KU 85412; 21 km. NE Managua, KU

85413-4; 5 km. SW Managua, KU 43086-93; 2 km. N Sabana Grande, KU

85411; 3 km. N Sabana Grande, KU 43070-8; 20 km. S, 0.5 km. W Tipitapa,

KU 85410. Matagalpa: Guasqualie, UMMZ 116493; Matagalpa, UMMZ

116492; 19 km. N Matagalpa, UMMZ 116494. Río San Juan: Greytown,

USNM 19585-6, 19767-8. Rivas: Javillo, UMMZ 123001; Moyogalpa, Isla

Ometepe, KU 85428-37, 87706 (tadpoles); Peñas Blancas, KU 85417; Río

Javillo, 3 km. N, 4 km. W Sapoá, KU 85418-20, 85438 (skeleton); 13.1 km.

SE Rivas, KU 85415; 14.8 km. SE Rivas, KU 85421-3; 11 km. S, 3 km. E

Rivas, KU 85416; 16 km. S Rivas, MCZ 29009-10; 7.7 km. NE San Juan del

Sur, KU 85426-7; 16.5 km. NE San Juan del Sur, KU 85424-5, 87705 (young);

5 km. SE San Pablo, KU 43079-83. Zelaya: Cooley, AMNM 7063-8, 8019-20,

8022, 8034-5; Cukra, AMNH 8016-7; Musahuas, Río Huaspuc, AMNH 58428-31;

11 km. NW Rama, Río Siquia, UMMZ 79708, 79709 (5), 79710 (2); Río

Escondido, USNM 19766, 20701; Río Siquia at Río Mico, UMMZ 79707 (10);

Sioux Plantation, AMNH 7058-61, 8023-33.

Costa Rica: Alajuela: Los Chiles, AMNH 54639; Orotina, MCZ 7960-1;

San Carlos, USNM 29991. Guanacaste: La Cruz, USC 8232 (3); 4.3 km. NE

La Cruz, UMMZ 123002; 18.4 km. S La Cruz, USC 8136; 23.5 km. S La Cruz,

USC 8094 (4); 3 km. W La Cruz, USC 8233 (4); 2 km. NE Las Cañas, KU

64235-7; Las Huecas, UMMZ 71212-3; Liberia, KU 36787, USC 8161; 11.5

km. N Liberia, USC 8149; 13 km. N Liberia, USC 8139; 22.4 km. N Liberia,

USC 8126; 8 km. NNW Liberia, KU 64238; 8.6 km. ESE Playa del Coco,

USC 8137; 21.8 km. ESE Playa del Coco, USC 8138; Río Piedra, 1.6 km. W

Bagaces, USC 7027; Río Bebedero, 5 km. S Bebedero, KU 64158; 5 km. NE

Tilarán, KU 36782-6. Heredia: 13 km. SW Puerto Viejo, KU 64142-6.

Limón: Batán, KU 34927; Guacimo, USC 621; Pandora, USC 505 (3); Suretka,

KU 36788-9; Tortugero, UF 7697, 10540-2. Puntarenas: Barranca, CNHM

35254-6; 15 km. WNW Barranca, KU 64155-7, UMMZ 118381; 18 km. WNW

Barranca, UMMZ 118382 (4); 4 km. WNW Esparta, KU 64159-96, 68178-82

(skeletons); 19 km. NW Esparta, KU 64147-54.

Smilisca cyanosticta (Smith), new combination

Taylor and Smith, Proc. U. S. Natl. Mus., 95(3185):589, June 30, 1945.

[Pg 304]

111147 from Piedras Negras, El Petén, Guatemala; Hobart

M. Smith collector]. Shannon and Werler, Trans. Kansas Acad. Sci.,

58:386, Sept. 24, 1955. Poglayen and Smith, Herpetologica, 14:11, April

25, 1958. Cochran, Bull. U. S. Natl. Mus., 220:57, 1961. Smith, Illinois

Biol. Mono., 32:25, May, 1964.

122:42, April 2, 1963. Duellman, Univ. Kansas Publ. Mus. Nat. Hist.,

15(5):229, Oct. 4, 1963.

Diagnosis.—Size moderately large ([M] 56.0 mm., [F] 70.0 mm.); skull as

long as wide; frontoparietal fontanelle large; narrow supraorbital flanges having

irregular margins anteriorly; large squamosal not in contact with maxillary;

tarsal fold moderately wide, full length of tarsus; inner metatarsal tubercle

moderately large, low, flat, elliptical; hind limbs relatively long; tibia usually

more than 52 per cent of snout-vent length; labial stripe silvery-white; lips

lacking vertical bars; loreal region pale green; pale bronze-colored stripe from

nostril along edge of eyelid to point above tympanum narrow, bordered below

by narrow dark brown stripe from nostril to eye, and broad dark brown

postorbital mark encompassing tympanum and terminating above insertion of

arm; flanks, dark brown with large pale blue spots; anterior and posterior

surfaces of thighs dark brown with small pale blue spots on thighs. (Foregoing

combination of characters distinguishing S. cyanosticta from any other species

in genus.)

Description and Variation.—The largest males are from Piedras Negras, El

Petén, Guatemala, and they average 52.5 mm. in snout-vent length whereas

males from Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, average 50.6 mm. and those from northern

Oaxaca 50.3 mm. The smallest breeding male has a snout-vent length of 44.6

mm. The average ratio of tibia length to snout-vent length is 54.8 per cent

in males from Piedras Negras, and 56.4 and 56.3 per cent in males from Los

Tuxtlas and Oaxaca, respectively. The only other character showing noticeable

geographic variation is the size of the tympanum. The average ratio of the

diameter of the tympanum to the diameter of the eye is 76.3 per cent in males

from Piedras Negras, 71.8 from Oaxaca, and 66.9 from Los Tuxtlas.

The dorsal ground color of Smilisca cyanosticta is pale green to tan and

the venter is creamy white. The dorsum is variously marked with dark olive-green

or dark brown spots or blotches (Pl. 6B). An interorbital dark bar

usually is present. The most extensive dark area is a V-shaped mark in the

occipital region with the anterior branches not reaching the eyelids; this mark

is continuous, by means of a narrow mid-dorsal mark, with an inverted V-shaped

mark in the sacral region. In many specimens this dorsal marking is

interrupted, resulting in irregular spots. In some specimens the dorsum is

nearly uniform pale green or tan with a few small, dark spots. The hind limbs

are marked by dark transverse bands, usually three or four each on the thigh

and shank, and two or three on the tarsus. The webbing on the feet is brown.

The loreal region is pale green, bordered above by a narrow, dark brown

canthal stripe extending from the nostril to the orbit, which is bordered above

by a narrow, bronze-colored stripe extending from the nostril along the edge

of the eyelid to a point above the tympanum. The upper lip is white. A

broad dark brown mark extends posteriorly from the orbit and encompasses the

tympanum to a point above the insertion of the forelimb. The flanks are dark

brown with many pale blue, rounded spots, giving the impression of a pale

[Pg 305]

blue ground color with dark brown mottling enclosing spots. The anterior

and posterior surfaces of the thighs are dark brown with many small pale

blue spots. The inner surfaces of the shank and tarsus are colored like the

posterior surfaces of the thighs. Pale blue spots are usually present on the

proximal segments of the second and third toes. A distinct white stripe is

present on the outer edge of the tarsus and fifth toe; on the tarsus the white

stripe is bordered below by dark brown. A white stripe also is present on the

outer edge of the forearm and fourth finger. The anal region is dark brown,

bordered above by a narrow transverse white stripe. The throat in breeding

males is dark, grayish brown with white flecks.

No geographic variation in the dorsal coloration is evident. Specimens from

the eastern part of the range (Piedras Negras and Chinajá, Guatemala) have

bold, dark reticulations on the flanks enclosing large pale blue or pale green

spots, which fade to tan in preservative. Specimens from Oaxaca and Veracruz

characteristically have finer dark reticulations on the flanks enclosing smaller

blue spots; in many of these specimens the ventrolateral spots are smallest and

are white.

All living adults are easily recognized by the presence of pale, usually blue,

spots on the flanks and thighs. Individuals under cover by day have a tan

dorsum with dark brown markings. A hiding individual at Chinajá, Alta

Verapaz, Guatemala (KU 55936), had a pale tan dorsum when found; later

the dorsal color changed to chocolate brown. A pale green patch was present

below the eye; the spots on the posterior surfaces of the thighs were pale blue,

and those on the flanks were yellowish green. A calling male obtained 10

kilometers north-northwest of Chinajá (KU 55934) was reddish brown when

found at night; later the dorsal color changed to pale tan. A green patch below

the eye was persistent. Usually these frogs are green at night. The coloration

of an adult male (KU 87201) from 11 kilometers north of Vista Hermosa,

Oaxaca, México, was typical: "When calling dorsum pale green; later changed