The Project Gutenberg eBook of Antarctic Penguins: A Study of Their Social Habits

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Antarctic Penguins: A Study of Their Social Habits

Author: G. Murray Levick

Release date: August 1, 2011 [eBook #36922]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jana Srna and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by

Biodiversity Heritage Library.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ANTARCTIC PENGUINS: A STUDY OF THEIR SOCIAL HABITS ***

Transcriber's Notes:

Every effort has been made to replicate

this text as faithfully as possible, including inconsistencies

in spelling and hyphenation.

Some corrections of spelling and punctuation have been made.

They are marked like

this in the text. The original text appears when hovering the cursor

over the marked text. A list of amendments is

at the end of the text.

ANTARCTIC PENGUINS

THE HEART OF THE

ANTARCTIC. Being a Story of the British

Antarctic Expedition, 1907–1909. By Sir

E. H. Shackleton, C.V.O. With Introduction by

Hugh Robert Mill, D.S.O. An Account of

the First Journey to the South Magnetic

Pole by Professor T. W. Edgworth David,

F.R.S. 2 vols., crown 4to. Illustrated with

Maps and Portraits. 36s net. Edition de

Luxe, with Autographs, Special Contributions,

Etched Plates, and Pastel Portraits. £10 10s

net. New and Revised Edition. With Coloured

Illustrations and Black and White. Crown 8vo,

6s net.

SHACKLETON IN THE

ANTARCTIC. (Hero Readers.) Crown

8vo, 1s 6d.

LOST IN THE ARCTIC. Being

the Story of the “Alabama” Expedition. By

Captain Ejnar Mickelson. Crown 4to. Illustrations

and Maps. 18s net.

IN NORTHERN MISTS. Arctic

Exploration in Early Times. By

Fridtjof Nansen. With numerous Illustrations and

Coloured Frontispieces. 2 vols., cr. 4to, 30s net.

LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

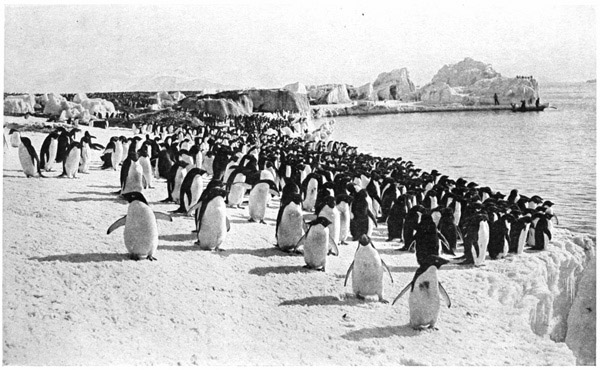

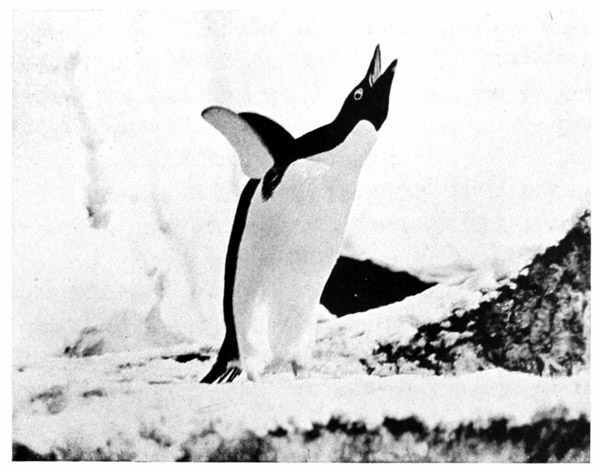

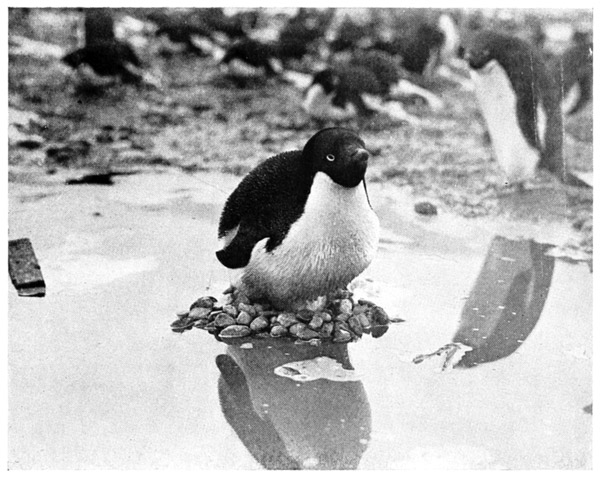

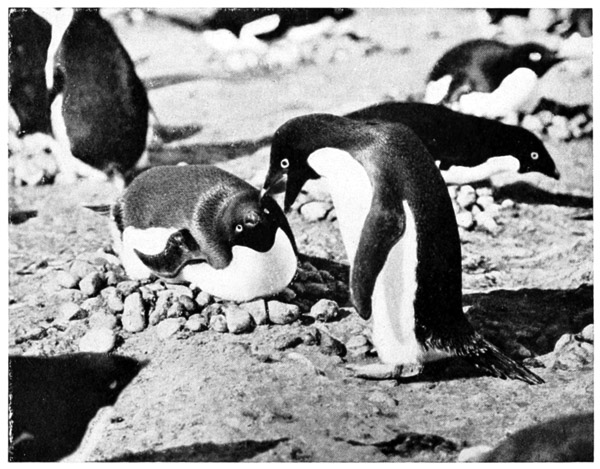

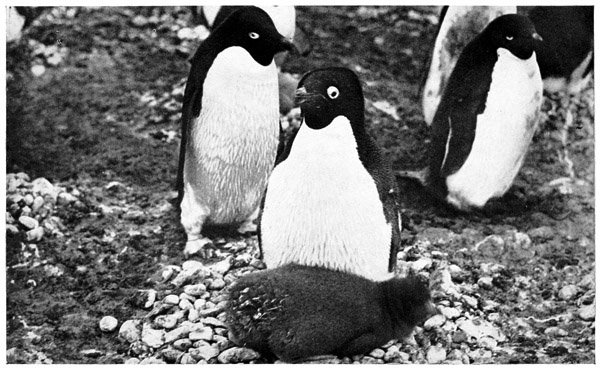

“OCCASIONALLY AN UNACCOUNTABLE ‘BROODINESS’ SEEMED TO TAKE POSSESSION OF THE PENGUINS” (Page 108)

Frontispiece

ANTARCTIC

PENGUINS

A STUDY OF THEIR SOCIAL HABITS

BY

DR. G. MURRAY LEVICK, R.N.

ZOOLOGIST TO THE BRITISH ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION

[1910–1913]

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

First Published March 1914

Second Impression May 1914

LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN 1914

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| PART I | |

| THE FASTING PERIOD | 17 |

| PART II | |

| DOMESTIC LIFE OF THE ADÉLIE PENGUIN | 51 |

| APPENDIX | 119 |

| PART III | |

| McCORMICK'S SKUA GULL | 125 |

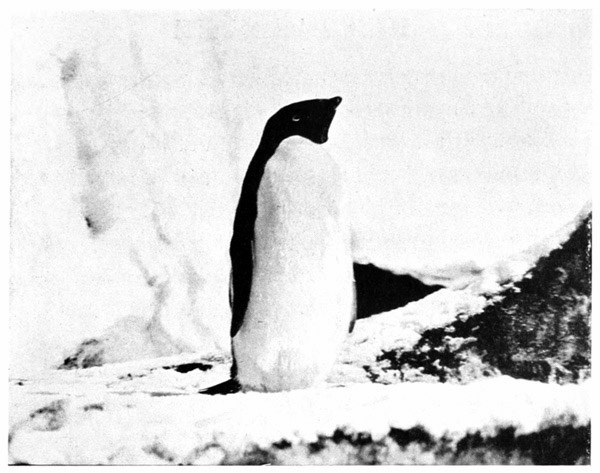

| A SHORT NOTE ON EMPEROR PENGUINS | 134 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| “Occasionally an unaccountable ‘broodiness’ seemed to take possession of the penguins” | Frontispiece |

| To face p. | |

| An angry Adélie | 2 |

| Dozing | 4 |

| Waking up, stretching, and yawning | 4 |

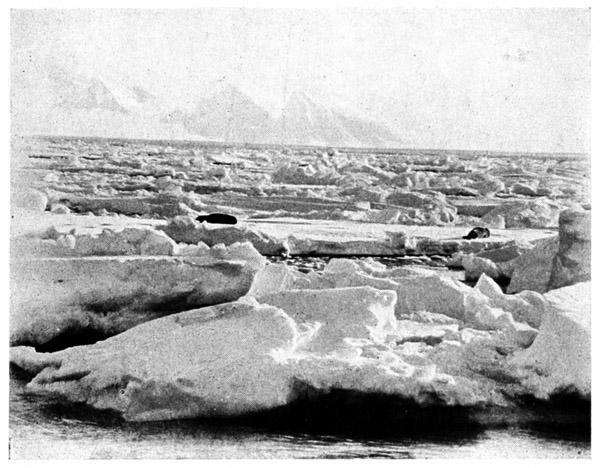

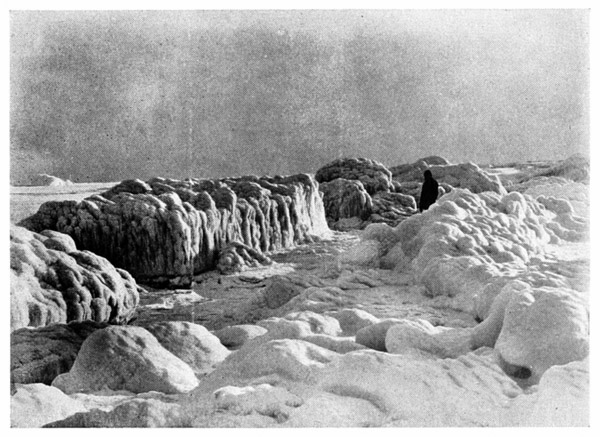

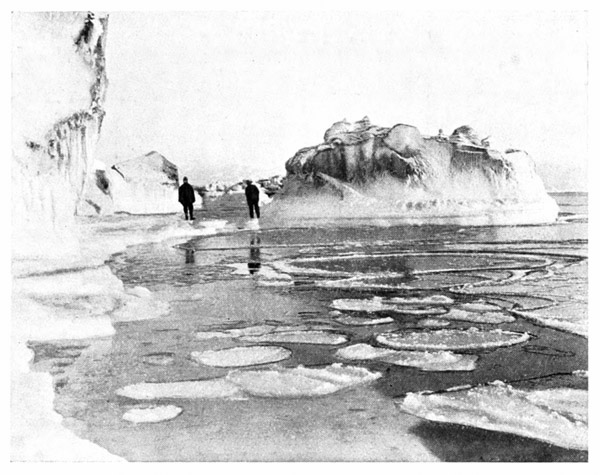

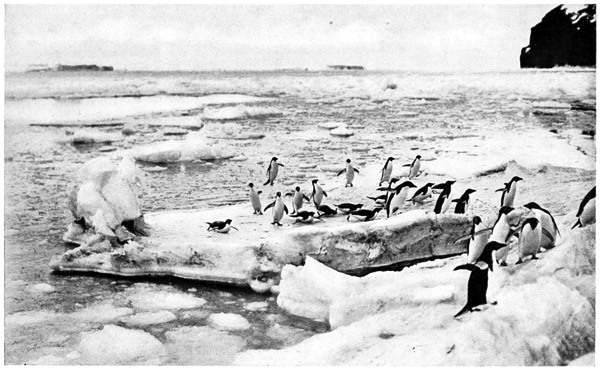

| Pack-ice | 8 |

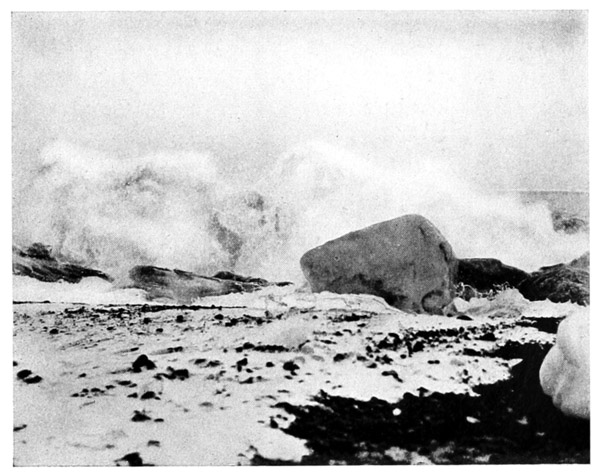

| Heavy seas in the autumn | 8 |

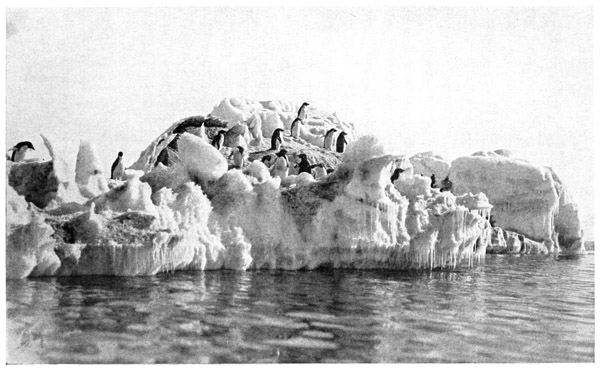

| “throw up masses of ice” | 10 |

| “which are frozen into a compact mass” | 10 |

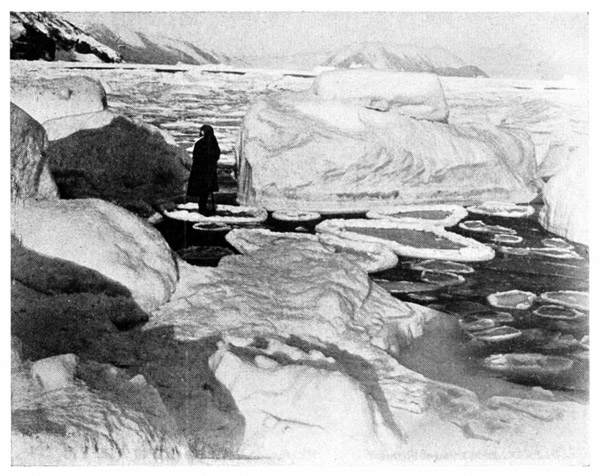

| “and later, form the beautiful terraces of the ice-foot” | 14 |

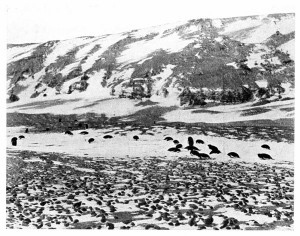

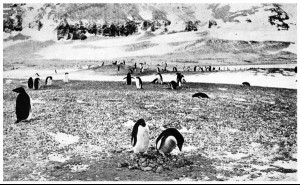

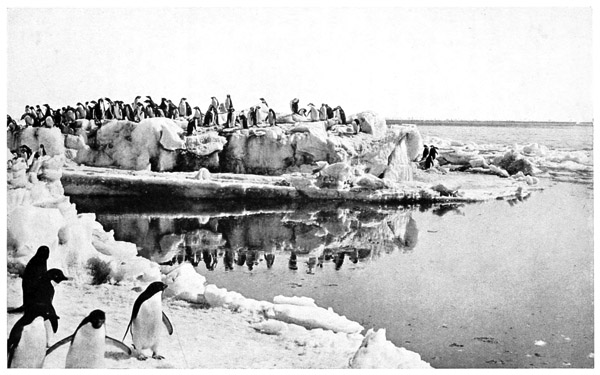

| Penguins at the rookery | 14 |

| In the foreground a mated pair have begun to build | 20 |

| The rookery beginning to fill up | 22 |

| “The hens would keep up this peck-pecking hour after hour” | 24 |

| An affectionate couple | 24 |

| “Side by side … nests of very big stones and nests of very small stones” | 26 |

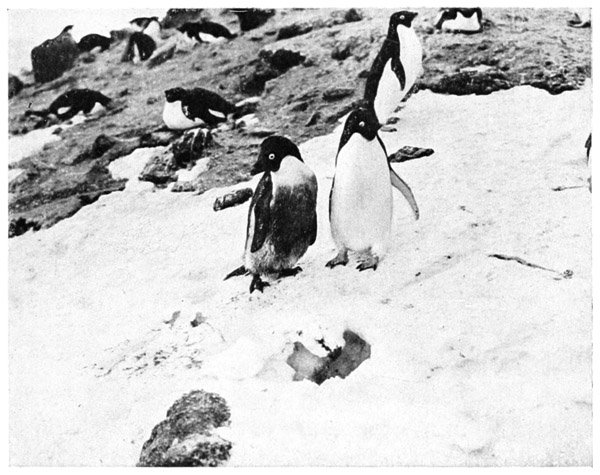

| On the march to the rookery | 28 |

| Part of the line of approaching birds, several miles in length | 30 |

| Arriving at the rookery | 32, 34 |

| Adélies arriving | 36 |

| A cock carrying a stone to his nest | 36 |

| Several interesting things are taking place here | 38 |

| Three cocks in rivalry | 40 |

| Two of the cocks squaring up for battle | 40 |

| Hard at it | 42 |

| The end of the battle | 42 |

| The proposal | 44 |

| Cocks fighting for hens | 46, 48 |

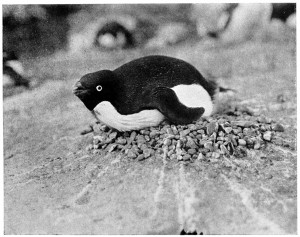

| Penguin on nest | 48 |

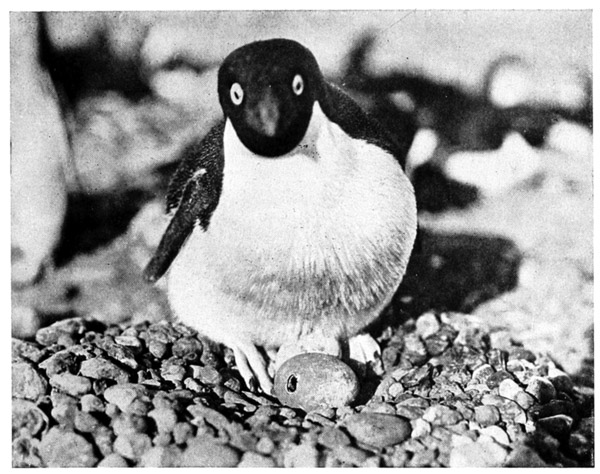

| Showing the position of the two eggs | 50 |

| An Adélie in “ecstatic” attitude | 50 |

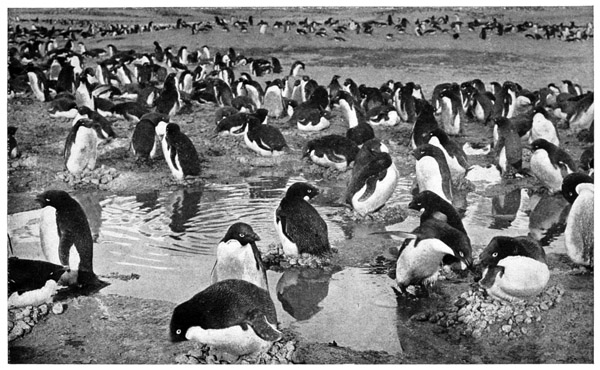

| Floods | 52 |

| Flooded | 54 |

| A nest with stones of mixed sizes | 54 |

| “Hour after hour … they fought again and again” | 56 |

| A nest on a rock | 58 |

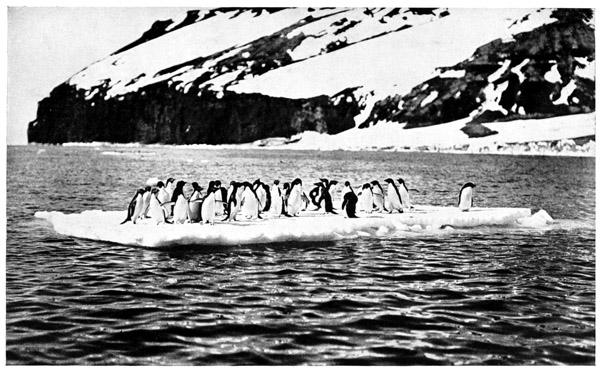

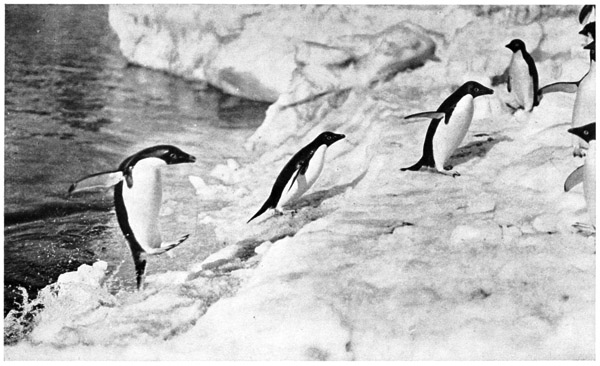

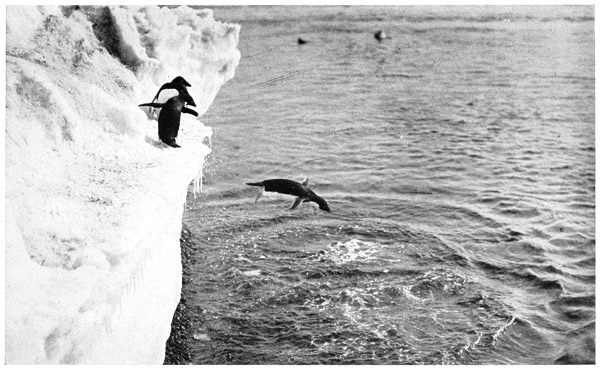

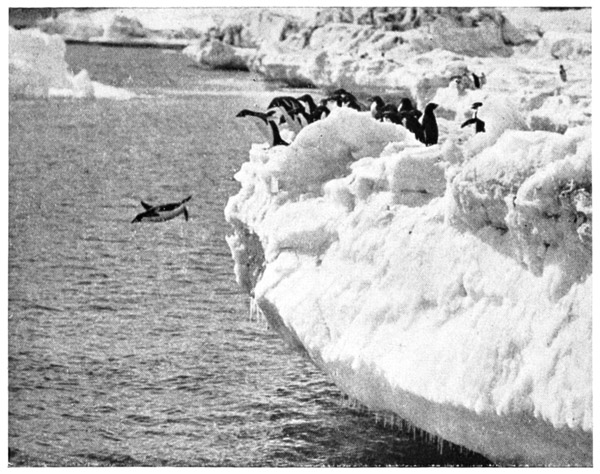

| “One after another, the rest of the party followed him” | 58 |

| A joy ride | 60 |

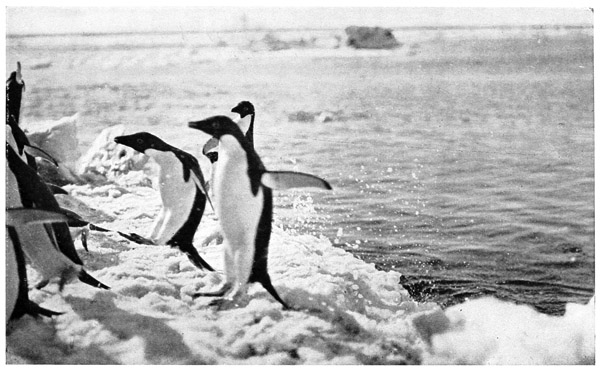

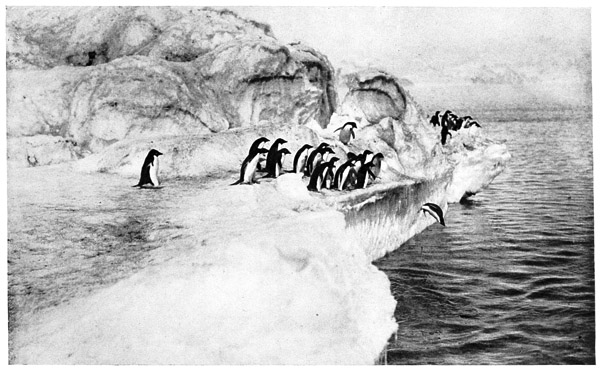

| A knot of penguins on the ice-foot | 62 |

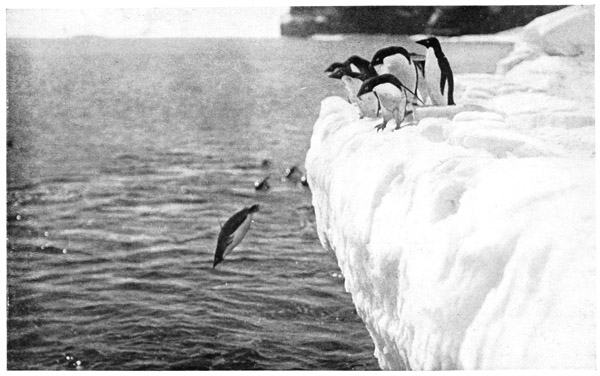

| An Adélie leaping from the water | 64 |

| An Adélie leaping four feet high and ten feet long | 66 |

| Jumping on to slippery ice | 68 |

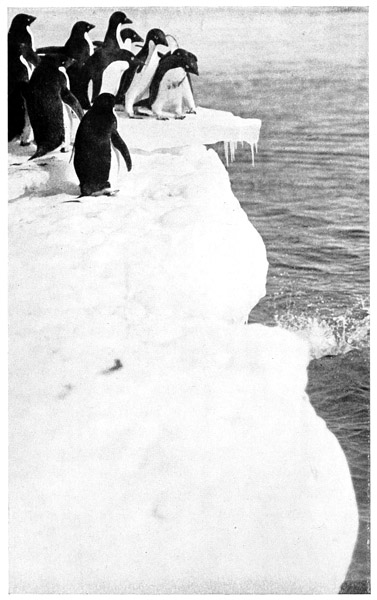

| “When they succeeded in pushing one of their number over, all would crane their necks over the edge” | 70 |

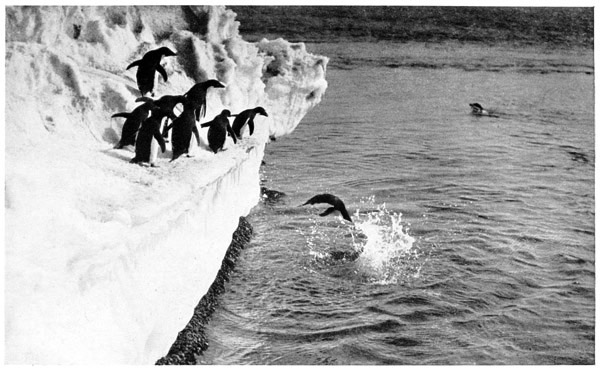

| Diving flat into shallow water | 72, 74, 76, 78 |

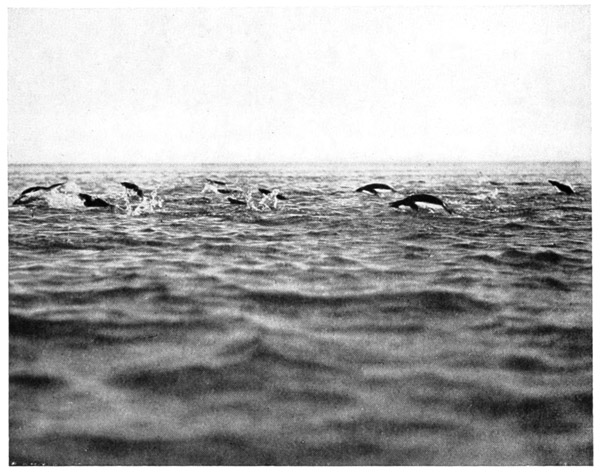

| Adélies “porpoising” | 78 |

| A perfect dive into deep water | 80 |

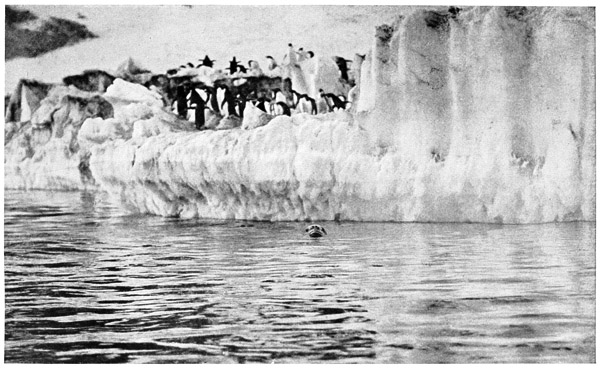

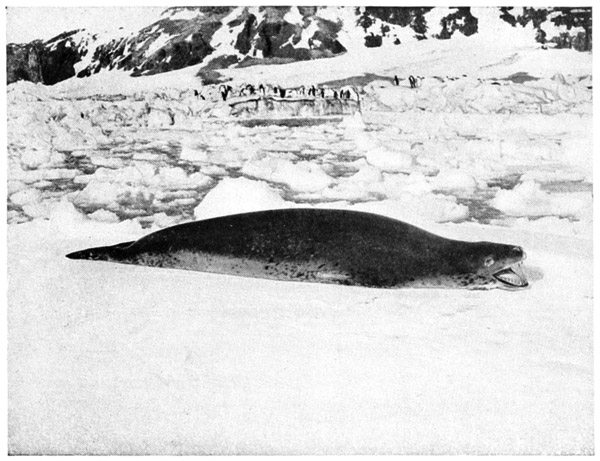

| Sea-leopards “lurk beneath the overhanging ledges” | 82 |

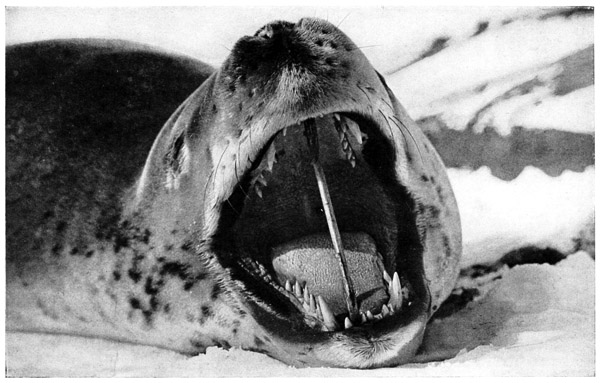

| A sea-leopard's head | 84 |

| A sea-leopard 10 ft. 6½ in. long | 86 |

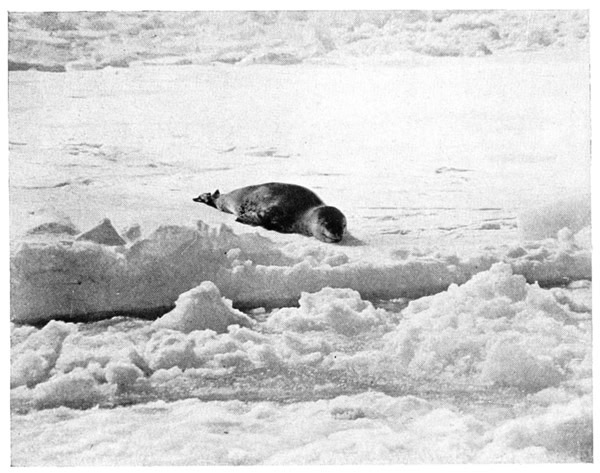

| A young sea-leopard on sea-ice | 86 |

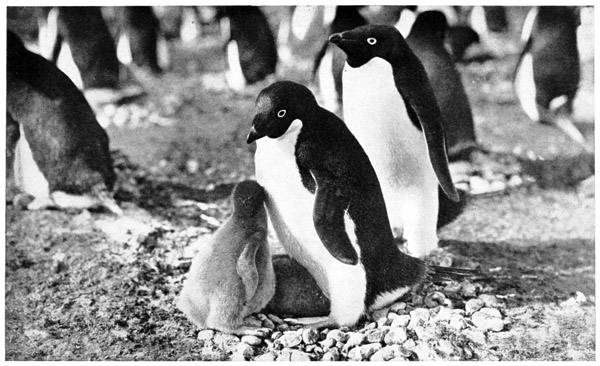

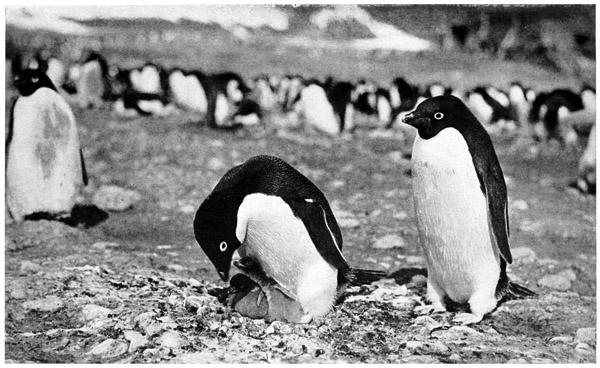

| “With graceful arching of his neck, appeared to assure her of his readiness to take charge” | 88 |

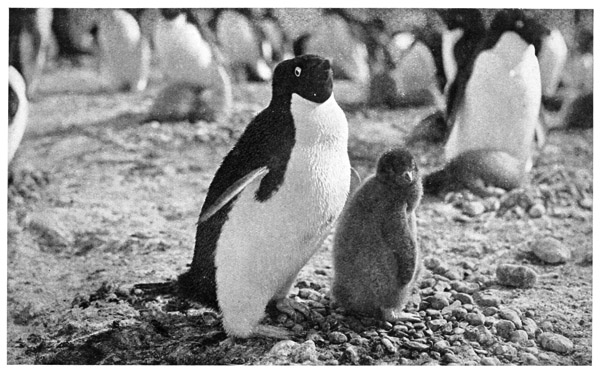

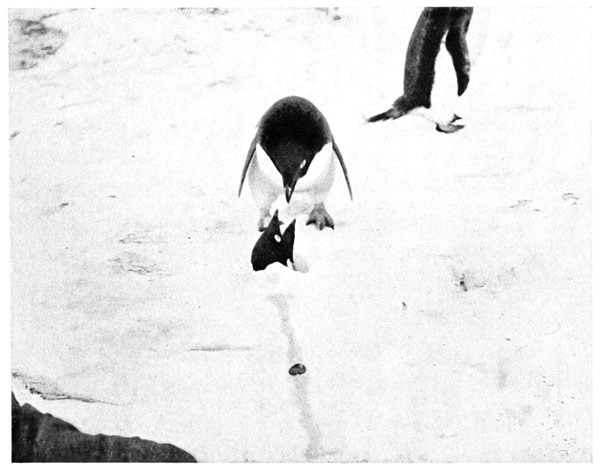

| “The chicks began to appear” | 90 |

| An Adélie being sick | 90 |

| Method of feeding the young | 92 |

| Profile of an Adélie chick | 94 |

| A task becoming impossible | 96 |

| Adélie with chick twelve days old | 98 |

| A couple with their chicks | 100 |

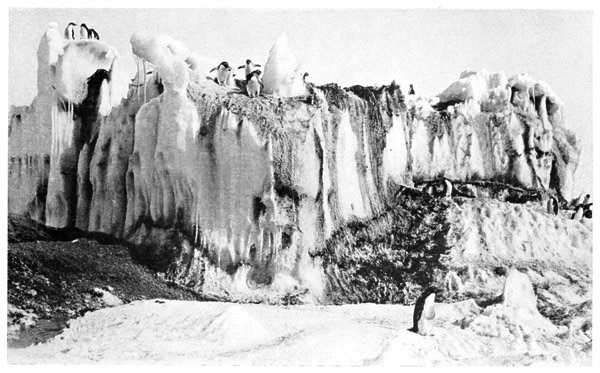

| Adélie penguins have a strong love of climbing for its own sake | 102 |

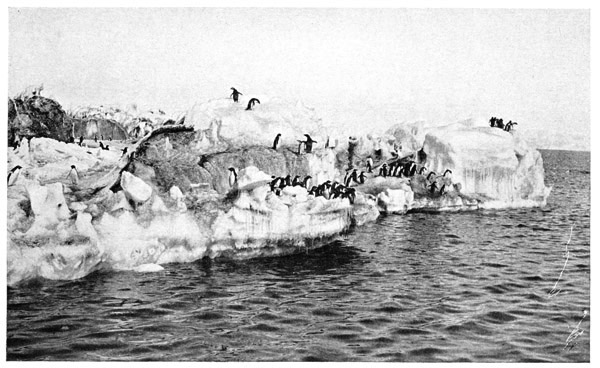

| Adélies on the ice-foot | 104, 106, 108 |

| “An imprisoned hen was poking her head up” | 110 |

| “Her mate appeared to be very angry with her” | 110 |

| “When she broke out, they became reconciled” | 112 |

| Adélie nests on top of Cape Adare | 112 |

| “Leapt at one another into the air” | 130 |

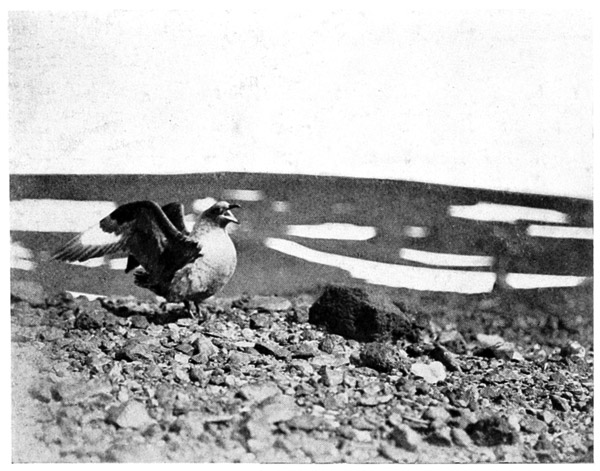

| A Skua by its chick | 130 |

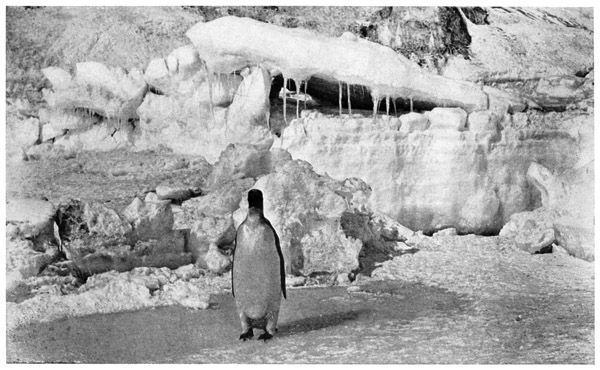

| An Emperor Penguin | 134 |

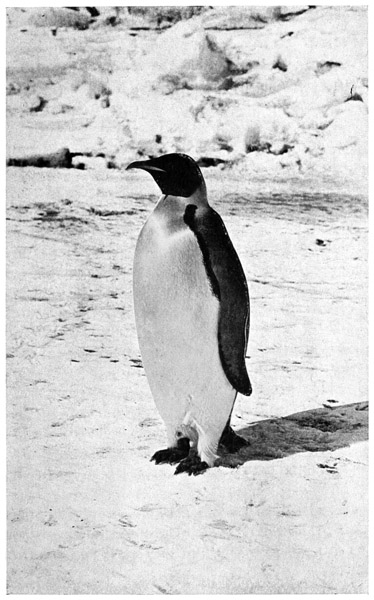

| Profile of an Emperor | 136 |

ADÉLIE PENGUINS(1)

INTRODUCTION

The penguins of the Antarctic regions very rightly

have been termed the true inhabitants of that

country. The species is of great antiquity, fossil

remains of their ancestors having been found,

which showed that they flourished as far back as the

eocene epoch. To a degree far in advance of any

other bird, the penguin has adapted itself to the sea

as a means of livelihood, so that it rivals the very

fishes. This proficiency in the water has been

gained at the expense of its power of flight, but

this is a matter of small moment, as it happens.

In few other regions could such an animal as

the penguin rear its young, for when on land

its short legs offer small advantage as a means

of getting about, and as it cannot fly, it would

become an easy prey to any of the carnivora which

abound in other parts of the globe. Here, however,

there are none of the bears and foxes which inhabit

the North Polar regions, and once ashore the penguin

is safe.

The reason for this state of things is that there is

no food of any description to be had inland. Ages

back, a different state of things existed: tropical

forests abounded, and at one time, the seals ran

about on shore like dogs. As conditions changed,

these latter had to take to the sea for food, with the

result that their four legs, in course of time, gave

place to wide paddles or “flippers,” as the penguins'

wings have done, so that at length they became

true inhabitants of the sea.

Were the Sea-Leopards(2) (the Adélies' worst

enemy) to take to the land again, there would be a

speedy end to all the southern penguin rookeries.

As these, however, are inhabited only during four

and a half months of the year, the advantage to

the seals in growing legs again would not be great

enough to influence evolution in that direction. At

the same time, I wonder very much that the sea-leopards,

who can squirm along at a fair pace

on land, have not crawled up the few yards of ice-foot

intervening between the water and some of

the rookeries, as, even if they could not catch

the old birds, they would reap a rich harvest among

the chicks when these are hatched. Fortunately

however they never do this.

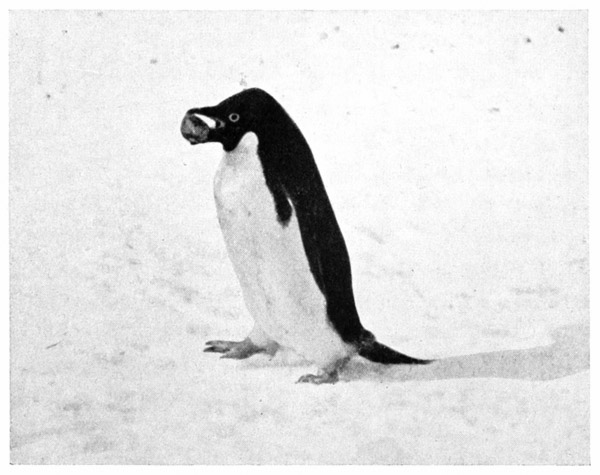

Fig. 1. AN ANGRY ADÉLIE

(Page 3)

When seen for the first time, the Adélie penguin

gives you the impression of a very smart little man

in an evening dress suit, so absolutely immaculate is

he, with his shimmering white front and black back

and shoulders. He stands about two feet five inches

in height, walking very upright on his little legs.

His carriage is confident as he approaches you over

the snow, curiosity in his every movement. When

within a yard or two of you, as you stand silently

watching him, he halts, poking his head forward

with little jerky movements, first to one side, then

to the other, using his right and left eye alternately

during his inspection. He seems to prefer using

one eye at a time when viewing any near object,

but when looking far ahead, or walking along,

he looks straight ahead of him, using both eyes.

He does this, too, when his anger is aroused,

holding his head very high, and appearing to squint

at you along his beak, as in Figure 1.

After a careful inspection, he may suddenly lose

all interest in you, and ruffling up his feathers sink

into a doze. Stand still for a minute till he has

settled himself to sleep, then make sound enough

to wake him without startling him, and he opens

his eyes, stretching himself, yawns, then finally walks

off, caring no more about you. (Figs. 2 and 3.)

The wings of Adélies, like those of the other

penguins, have taken the form of paddles, and are

covered with very fine scale-like feathers. Their

legs being very short, they walk slowly, with a

waddling gait, but can travel at a fair pace over

snow or ice by falling forward on to their breasts,

and propelling themselves with all four limbs.

To continue the sketch, I quote two other

writers:

M. Racovitza, of the “Belgica” expedition, well

describes them as follows:

“Imagine a little man, standing erect, provided

with two broad paddles instead of arms, with head

small in comparison with the plump stout body;

imagine this creature with his back covered with a

black coat … tapering behind to a pointed tail

that drags on the ground, and adorned in front

with a glossy white breast-plate. Have this creature

walk on his two feet, and give him at the same

time a droll little waddle, and a pert movement

of the head; you have before you something

irresistibly attractive and comical.”

Fig. 2. Dozing

Fig. 3. Waking up, Stretching, and Yawning

(Page 3)

Dr. Louis Gain, of the French Antarctic expedition,

gives us the following description:

“The Adélie penguin is a brave animal, and

rarely flees from danger. If it happens to be

tormented, it faces its aggressor and ruffles the

black feathers which cover its back. Then it takes

a stand for combat, the body straight, the animal

erect, the beak in the air, the wings extended, not

losing sight of its enemy.

“It then makes a sort of purring, a muffled

grumbling, to show that it is not satisfied, and has

not lost a bit of its firm resolution to defend itself.

In this guarded position it stays on the spot; sometimes

it retreats, and lying flat on the ground,

pushes itself along with all the force of its claws and

wings. Should it be overtaken, instead of trying

to increase its speed, it stops, backs up again to

face anew the peril, and returns to its position

of combat. Sometimes it takes the offensive,

throws itself upon its aggressor, whom it punishes

with blows of its beak and wings.”

The Adélie penguin is excessively curious, taking

great pains to inspect any strange object he may

see. When we were waiting for the ship to fetch

us home, some of us lived in little tents which we

pitched on the snow about fifty yards from the edge

of the sea. Parties of penguins from Cape Royds

rookery frequently landed here, and almost invariably

the first thing they did on seeing our tents,

was at once to walk up the slope and inspect these,

walking all round them, and often staying to doze by

them for hours. Some of them, indeed, seemed to

enjoy our companionship. When you pass on the

sea-ice anywhere near a party of penguins, these

generally come up to look at you, and we had great

trouble to keep them away from the sledge dogs

when these were tethered in rows near the hut at

Cape Evans. The dogs killed large numbers of

them in consequence, in spite of all we could do to

prevent this.

The Adélies, as will be seen in these pages, are

extremely brave, and though panic occasionally

overtakes them, I have seen a bird return time after

time to attack a seaman who was brutally sending

it flying by kicks from his sea-boot, before I arrived

to interfere. An exact description of the plumage

of the Adélie penguins will be found in the Appendix,

as it is more especially of their habits that I intend

to treat in this work.

Before describing these, and with a view to making

them more intelligible to the general reader, I will

proceed to a short explanation.

The Adélie penguins spend their summer and

bring forth their young in the far South. Nesting

on the shores of the Antarctic continent, and on the

islands of the Antarctic seas, they are always close

to the water, being dependent on the sea for their

food, as are all Antarctic fauna; the frozen regions

inland, for all practical purposes, being barren of

both animal and vegetable life.

Their requirements are few: they seek no shelter

from the terrible Antarctic gales, their rookeries in

most cases being in open wind-swept spots. In fact,

three of the four rookeries I visited were possibly in

the three most windy regions of the Antarctic. The

reason for this is that only wind-swept places are so

kept bare of snow that solid ground and pebbles

for making nests are to be found.

When the chicks are hatched and fully fledged,

they are taught to swim, and when this is accomplished

and they can catch food for themselves, both

young and old leave the Southern limits of the sea,

and make their way to the pack-ice out to the

northward, thus escaping the rigors and darkness

of the Antarctic winter, and keeping where they

will find the open water which they need. For in

the winter the seas where they nest are completely

covered by a thick sheet of ice which does not

break out until early in the following summer.

Much of this ice is then borne northward by tide

and wind, and accumulates to form the vast rafts

of what is called “pack-ice,” many hundreds of

miles in extent, which lie upon the surface of the

Antarctic seas. (Fig. 4.)

It is to this mass of floating sea-ice that the

Adélie penguins make their way in the autumn,

but as their further movements here are at present

something of a mystery, the question will be

discussed at greater length presently.

When young and old leave the rookery at the

end of the breeding season, the new ice has not yet

been formed, and their long journey to the pack

has to be made by water, but they are wonderful

swimmers and seem to cover the hundreds of miles

quite easily.

Arrived on the pack, the first year's birds remain

there for two winters. It is not until after their

first moult, the autumn following their departure

from the rookery, that they grow the distinguishing

mark of the adult, black feathers replacing the

white plumage which has hitherto covered the

throat.

The spring following this, and probably every

spring for the rest of their lives, they return South

to breed, performing their journey, very often, not

only by water, but on foot across many miles

of frozen sea.

Fig. 4. Pack Ice (on which the Adélies winter)

Two Weddell Seals are seen on a Floe

Fig. 5. Heavy Seas in the Autumn

(Page 10)

For those birds who nest in the southernmost

rookeries, such as Cape Crozier, this journey must

mean for them a journey of at least four hundred

miles by water, and an unknown but considerable

distance on foot over ice.

As I am about to describe the manners and

customs of Adélie penguins at the Cape Adare

rookery, I will give a short description of that spot.

Cape Adare is situated in lat. 71° 14′ S. long.

170° 10′ E., and is a neck of land jutting out from

the sheer and ice-bound foot-hills of South Victoria

Land northwards for a distance of some twenty

miles.

For its whole length, the sides of this Cape

rise sheer out of the sea, affording no foothold

except at the extreme end, where a low beach

has been formed, nestling against the steep side of

the cliff which here rises almost perpendicularly to

a height of over 1000 feet.

Hurricanes frequently sweep this beach, so that

snow never settles there for long, and as it is composed

of basaltic material freely strewn with

rounded pebbles, it forms a convenient nesting site,

and it was on this spot that I made the observations

set forth in the following pages.

Viewed before the penguins' arrival in the spring,

and after recent winds had swept the last snowfalls

away, the rookery is seen to be composed of a

series of undulations and mounds, or “knolls,”

while several sheets of ice, varying in size up to some

hundreds of yards in length and one hundred yards

in width, cover lower lying ground where lakes

of thaw water form in the summer. Though

doubtless the ridges and knolls of the rookery

owe their origin mainly to geological phenomena,

their contour has been much added to as, year

by year, the penguins have chosen the higher

eminences for their nests; because their guano,

which thickly covers the higher ground, has

protected this from weathering and the denuding

effect of the hurricanes which pass over it at

certain seasons and tend to carry away the small

fragments of ground that have been split up by the

frost.

The shores of this beach are protected by a

barrier of ice-floes which are stranded there by the

sea in the autumn. These floes become welded

together and form the “ice-foot” frequently referred

to in these pages, and photographs showing

how this is done are seen on Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8.

At the back of the rookery, nesting sites are

to be seen stretching up the steep cliff to a height

of over 1000 feet, some of them being almost

inaccessible, so difficult is the climb which the

penguins have made to reach them.

Fig. 6. “… Throw up Masses of Ice,

Fig. 7. “… Which are Frozen into a Compact Mass as

Winter approaches”

(Page 10)

On Duke of York Island, some twenty miles

south of the Cape Adare rookery, another breeding-place

has been made. This is a small colony only,

as might be expected. Indeed it is difficult to see

why the penguins chose this place at all whilst room

still exists at the bigger rookery, because Duke of

York Island, until late in the season, is cut off from

open water by many miles of sea-ice, so that with

the exception of an occasional tide crack, or seals'

blow holes, the birds of that rookery have no means

of getting food except by making a long journey on

foot. When the arrivals were streaming up to Cape

Adare many were seen to pass by, making in a

straight line for Duke of York Island, and so adding

another twenty miles on foot to the journey they

had already accomplished.

When the time arrived for the birds to feed, some

open leads had formed about half way across the

bay, and those of the Duke of York colony were to

be seen streaming over the ice for many miles on

their way between the water and their nests. They

seem to think nothing of long journeys, however,

as in the early season, when unbroken sea-ice intervened

between the two rookeries, parties of

penguins from Cape Adare actually used to march

out and meet their Duke of York friends half way

over, presumably for the pleasure of a chat.

To realize what this meant, we must remember that

an Adélie penguin's eyes being only about twelve

inches above the ground when on the march, his

horizon is only one mile distant. Thus from Cape

Adare he could just see the top of the mountain on

Duke of York Island peeping above the horizon on

the clearest day. In anything like thick weather he

could not see it at all, and probably he had never

been there. So in the first place, what was it that

impelled him to go on this long journey to meet his

friends, and when so impelled, what instinct pointed

out the way? This of course merely brings us to

the old question of migratory instinct, but in the

case of the penguin, its horizon is so very short that

it is quite evident he possesses a special sense of

direction, in addition to the special sense which

urged him to go and meet the Duke of York Island

contingent, and I may here remark that when we

were returning to New Zealand in the summer of

1913, we passed troops of penguins swimming in the

open sea far out of sight of land,—an unanswerable

reply to those naturalists who still maintain that

migrating birds must rely upon their eyes for

guidance, and this remark applies equally to the

penguins we found on the northern limits of the

pack-ice, some five hundred miles from the rookeries

to which they would repair the following year.

| Mean date | Northern limit of pack | Miles from C. Adare | Southern limit of pack | Miles of pack N. and S. | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb. 3, 1839 | 68° S. | 190 | ? | ? | Balleny |

| Jan. 1, 1841 | 66° 30′ | 280 | 69° | 150 | Ross |

| Feb. 1, 1895 | 66° 15′ | 300 | 69° 45′ | 210 | Kristensen |

| Feb. 8, 1899 | 66° 0′ | 315 | 69° 0′ | 180 | Borchgravink |

| Feb. 27, 1904 | ? | 70° 30′ | ? | Scott | |

| Feb. 15, 1910 | nil | nil | Terra Nova | ||

| Mar. 13, 1912 | nil | nil | Terra Nova | ||

| Jan. 30, 1913 | nil | nil | Terra Nova |

Note.—Ross, Kristensen, Scott, Shackleton and Pennell all, however, found pack late

in the season while trying to work west along the coast when only some forty-five to

seventy-five miles north of Cape Adare, and all were turned by this pack.

According to Pennell, it appears probable that there is a great hang of pack in the

sea west of Cape Adare and south of the Balleny Islands, and most likely it is here that

the Adélies repair when they leave Cape Adare rookery in the autumn. I think, however,

it is safe to assume that they seek the northernmost limits of the pack during the winter,

as these would offer the most favourable conditions.

| Date | Longitude | Northern limit | Extends N. and S. Miles | Minutes of latitude Northern limit is N. of Cape Adare |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. 12, 1840 | 166° E. | 64° 30′ | — | 400 (Wilkes) |

| Jan. 3, 1902 | 178° E. | 67° S. | 140 | 250 (Discovery) |

| Dec. 31, 1902 | 180° E. | 66° 30′ | 60 | 280 (Morning) |

| Second belt | 69° | 30 | 130 (Morning) | |

| Dec. 20, 1908 | 178° W. | 66° 30′ | 60 | 270 (Nimrod) |

| Dec. 9, 1910 | 178° W. | 64° 45′ | 300 | 390 (Terra Nova) |

| Dec. 27, 1911 | 177° W. | 65° 20′ | 160 | 360 (Terra Nova) |

| Mar. 8, 1911 | 162° E. | 64° 30′ | 270 | 400 (Terra Nova) |

Fig. 8. “… And later, form the Beautiful Terraces of

the Ice-foot”

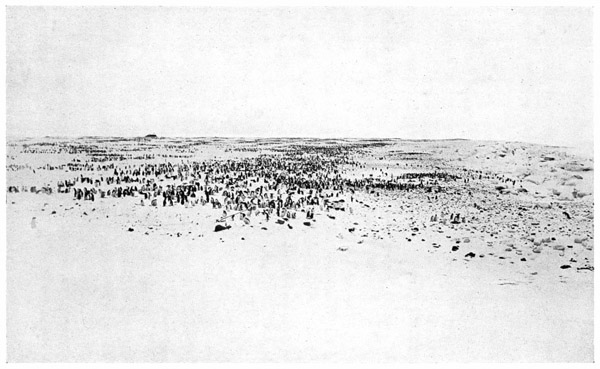

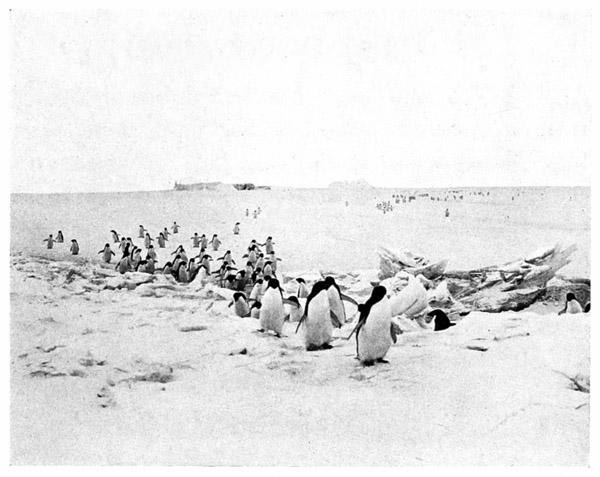

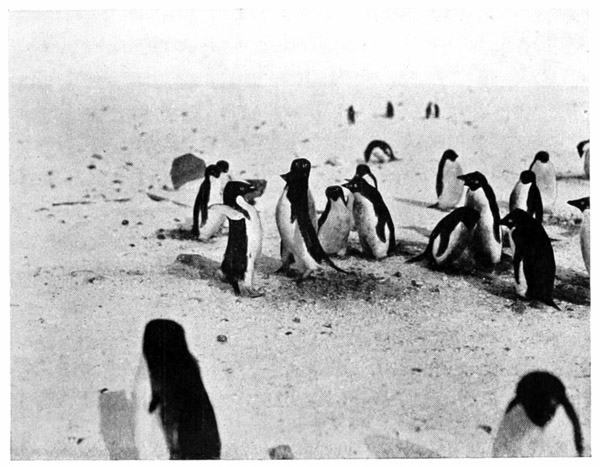

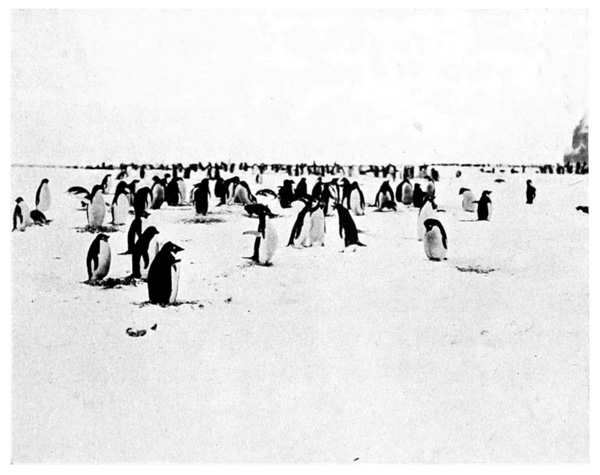

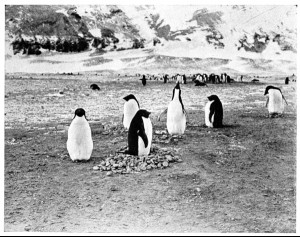

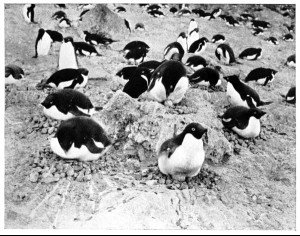

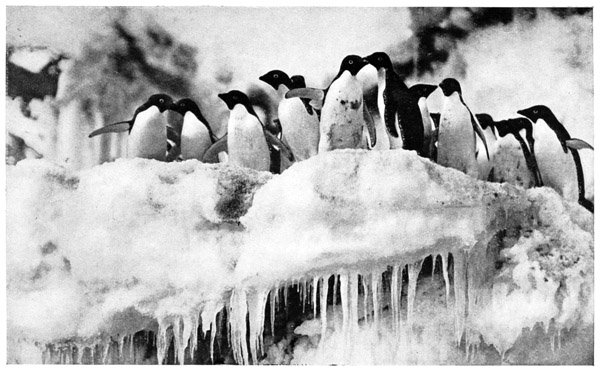

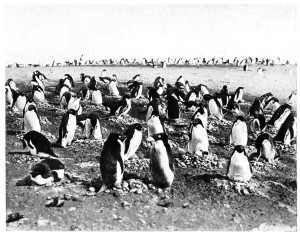

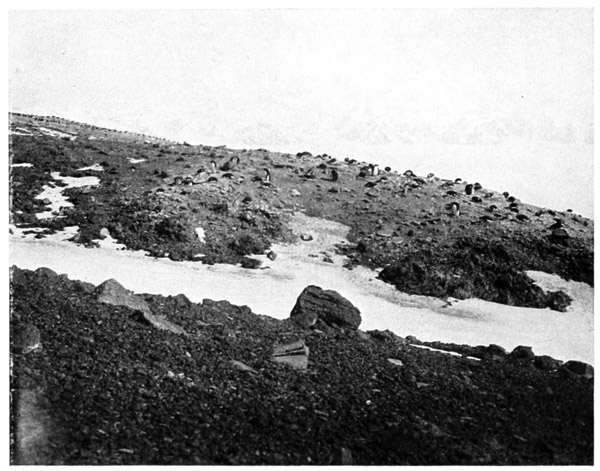

Fig. 9. Penguins at the Rookery

(Page 18)

The exact whereabouts of the Adélie penguins

during the winter months has been much discussed

by different writers. It is agreed that they repair

to the pack-ice, but our knowledge of the movements

of this pack is very vague at the present

time, and so unfortunately I can give but a rough

idea of the subject.

I have collected and noted down the latest

evidence for the benefit of the zoologists of future

expeditions who may wish to investigate the matter

further, and I am indebted for nearly the whole of

it to Commander Harry L. Pennell, R.N., commander

of the Terra Nova from 1910 to 1913,

who kindly drew up for me Tables A and B (see

pp. 13 and 14).

Probably the information which more nearly concerns

the penguins of Cape Adare rookery will be

found in Table A. The birds from Cape Crozier

and Cape Royds rookeries must have some four

hundred miles further to travel when they go North

in the autumn than those at Cape Adare.

PART I

THE FASTING PERIOD

Diary from October 13 to November 3, describing the

arrival of the Adélie penguins at the rookery, and

habits during the periods of mating and building.

The first Adélie penguins arrived at the Ridley

Beach rookery, Cape Adare, on October 13. A

blizzard came on then, with thick drift which

prevented any observations being made. The

next day, when this subsided, there were no penguins

to be seen.

On October 15 two of them were loitering about

the beach. During the forenoon they were separate,

but in the afternoon they kept company, and

walked over to the south-east corner of the rookery

under the cliff of Cape Adare, where they were

sheltered from the cold breeze.

On October 16 at 11 A.M. there were about

twenty penguins arrived. Several came singly,

and one little party of three came up together.

On arrival they wandered about by themselves,

and stood or walked about the beach, giving one

the impression of simply hanging about, waiting

for something to “turn up.”

By 4 P.M. there must have been close on a

hundred penguins at the rookery. It was a calm

day and misty, so that I could not see far out

across the sea-ice, but so far it was evident that

the birds were not arriving in batches, but just

dribbling in. They were then for the most part

squatting about the rookery, well scattered, some

solitary, others in groups, and facing in all directions.

(Fig. 9.) They were not on the prominences

where the nesting sites are, but in the

hollows and on the snow of the frozen lakes.

There was no sign of love-making or any activity

whatever. All were in fine plumage and condition.

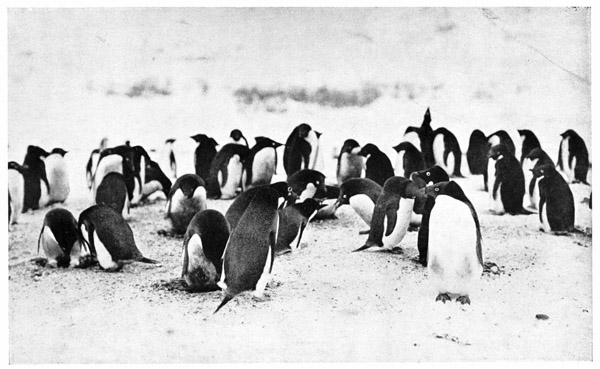

During the night of October 16 the number of

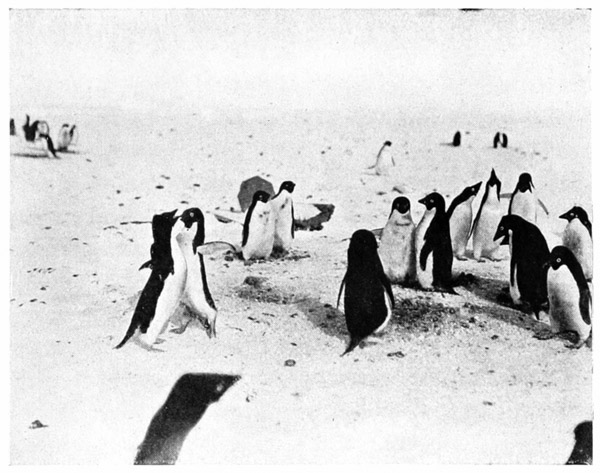

penguins increased greatly, and on the morning of

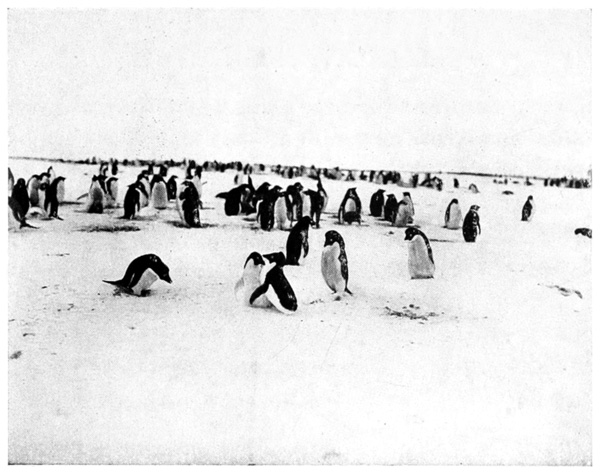

the 17th there was a thin sprinkling scattered over

the rookery. (Fig. 11.) A few were in pairs or

threes, but more in groups of a dozen or more, and

all the birds were very phlegmatic, many of them

lying on their breasts, with beaks outstretched,

apparently asleep, and nearly all, as yesterday, in

the hollows, though there was no wind, and away

from the nesting sites. They were very quiet.

Probably they were fatigued after their journey;

perhaps also they were waiting the stimulation of a

greater crowd before starting their breeding operations.

As the guano-covered ridges, on which the

old nests are, were fairly soft and the pebbles

loose, they were not waiting for higher temperatures

in order to get to work.

During October 17 the arrivals became gradually

more frequent. They were dribbling up from the

sea-ice at the north-end of the beach, and soon

made a well-worn track up the ice-foot, whilst a

long line of birds approaching in single file, with

some gaps, extended to the horizon in a northerly

direction.

During the day I noticed some penguins taking

possession of old nests on the ridges. These mostly

squatted in the nests without any attempt at

repairing them or rearrangement of any sort.

Afterwards I found that they were unmated hens

waiting for mates to come to them, and that this

was a very common custom among them. (Fig. 10.)

If two occupied nests within reach of one another

they would stretch out their necks and peck at

each other. Their endeavour seemed to be to peck

each other's tongue, and this they frequently did,

but generally struck the soft parts round the margin

of the bills, which often became a good deal swollen

in consequence. Often also their beaks would

become interlocked. They would keep up this

peck-pecking hour after hour in a most relentless

fashion. (Fig. 12.) On one occasion I saw a hen

succeed in driving another off one of the old nests

which she occupied. The vanquished one squatted

on the ground a few yards away, with rumpled

feathers and “huffy” appearance, whilst the other

walked on to the nest and assumed the “ecstatic”

attitude (page 46). Nothing but animosity could

have induced this act, as thousands of old unoccupied

nests lay all around.

About 9 P.M. a light snowstorm came on,

and those few birds who had taken possession

of nests, left them, and all now lay in the hollows,

nestling into the fine drift which soon covered the

ground to the extent of a few inches. A group of

about a dozen penguins which arrived near the ice-foot

in the morning, halted on the sea-ice without

ascending the little slope leading to the rookery,

and stayed there all day.

With the few exceptions I have noted above, all

the birds that had arrived so far either were

much fatigued, or else they realized that they had

come a little too soon and were waiting for some

psychological moment to arrive, for they were all

strangely quiet and inactive.

Fig. 10. IN THE FOREGROUND A MATED PAIR HAVE BEGUN TO BUILD. BEHIND AND TO THE RIGHT TWO UNMATED HENS LIE IN THEIR SCOOPS

(Page 19)

On October 18 the weather cleared and a

fair number of penguins started to build their

nests. The great majority however, apparently

resting, still sat about. Those that built took

their stones from old nests, as at present so many

of these lay unoccupied. They made quite large

nests, some inches high at the sides, with a comfortable

hollow in the middle to sit in. The stone

carrying (Fig. 20) was done by the male birds, the

hens keeping continual guard over the nest, as

otherwise the pair would have been robbed of the

fruits of their labours as fast as they were acquired.

As I strolled through the rookery, most of

the birds took little or no notice of me. Some,

however, swore at me very savagely, and one

infuriated penguin rushed at me from a distance of

some ten yards, seizing the leg of my wind-proof

trousers. In the morning quite a large number lay

down on the sea-ice, a few yards short of the

rookery, content apparently to have got so far.

They lay there all day, motionless on their breasts,

with their chins outstretched on the snow.

By the evening of October 18 most of the

penguins had gathered in little groups on the nest-covered

eminences, but there was at that time

ample room for all, there being only about three

or four thousand arrived. Although there were

several open water holes against bergs frozen into

the sea-ice some half mile or so away, not a single

bird attempted to get food.

At 6 P.M. the whole rookery appeared to

sleep, and the ceaseless chattering of the past

hours gave place to a dead and impressive silence,

though here and there an industrious little bird

might be seen busily fetching stone after stone

to his nest.

At that date it was deeply dusk at midnight,

though the sun was very quickly rising in altitude,

and continuous daylight would soon overtake us.

Fig. 11. THE ROOKERY BEGINNING TO FILL UP

(Page 18)

By the morning of October 19 there had been

a good many more arrivals, but the rookery was

not yet more than one-twentieth part full. All

the birds were fasting absolutely. Nest building

was now in full swing, and the whole place waking

up to activity. Most of the pebbles for the new

nests were being taken from old nests, but a great

deal of robbery went on nevertheless. Depredators

when caught were driven furiously away, and

occasionally chased for some distance, and it was

curious to see the difference in the appearance

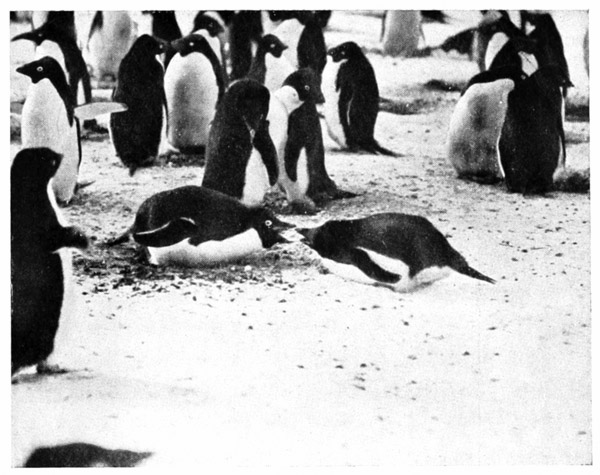

between the fleeing thief and his pursuer. As the

former raced and ducked about among the nests,

doubling on his tracks, and trying by every means

to get lost in the crowd and so rid himself of

his pursuer, his feathers lay close back on his

skin, giving him a sleek look which made him

appear half the size of the irate nest-holder who

sought to catch him, with feathers ruffled in indignation.

This at first led me to think that the hens

were larger than the cocks, as it was generally the

hen who was at home, and the cock who was after

the stones, but later I found that sex makes

absolutely no difference in the size of the birds,

or indeed in their appearance at all, as seen by the

human eye. After mating, their behaviour as well

as various outward signs serve to distinguish male

from female. Besides this certain differences in

their habits, which I will describe in another

place, are to be noted.

The consciousness of guilt, however, always

makes a penguin smooth his feathers and look

small, whilst indignation has the opposite effect.

Often when observing a knoll crowded with

nesting penguins, I have seen an apparently under-sized

individual slipping quietly along among the

nests, and always by his subsequent proceedings he

has turned out to be a robber on the hunt for

his neighbours' stones. The others, too, seemed to

know it, and would have a peck at him as he passed

them.

At last he would find a hen seated unwarily

on her nest, slide up behind her, deftly and silently

grab a stone, and run off triumphantly with it

to his mate who was busily arranging her own

home. Time after time he would return to the

same spot, the poor depredated nest-holder being

quite oblivious of the fact that the side of her nest

which lay behind her was slowly but surely vanishing

stone by stone.

Here could be seen how much individual character

makes for success or failure in the efforts of the

penguins to produce and rear their offspring.

There are vigilant birds, always alert, who seem

never to get robbed or molested in any way: these

have big high nests, made with piles of stones.

Others are unwary and get huffed as a result.

There are a few even who, from weakness of

character, actually allow stronger natured and

more aggressive neighbours to rob them under

their very eyes.

Fig. 12. “The Hens would keep up this Peck-pecking

hour after Hour”

Fig. 13. An Affectionate Couple

(Page 26)

In speaking of the robbery which is such a

feature of the rookery during nest building, special

note must be made of the fact that violence is

never under any circumstances resorted to by the

thieves. When detected, these invariably beat a

retreat, and offer not the least resistance to the

drastic punishment they receive if they are caught

by their indignant pursuers. The only disputes

that ever take place over the question of property

are on the rare occasions when a bona-fide misunderstanding

arises over the possession of a nest.

These must be very rare indeed, as only on one

occasion have I seen such a quarrel take place.

The original nesting sites being, as I will show,

chosen by the hens, it is the lady, in every case,

who is the cause of the battle, and when she is

won her scoop goes with her to the victor.

As I grew to know these birds from continued

observation, it was surprising and interesting to

note how much they differed in character, though

the weaker-minded who would actually allow themselves

to be robbed, were few and far between, as

might be expected. Few, if any, of these ever

could succeed in hatching their young and winning

them through to the feathered stage.

When starting to make her nest, the usual procedure

is for the hen to squat on the ground for

some time, probably to thaw it, then working with

her claws to scratch away at the material beneath

her, shooting out the rubble behind her. As she

does this she shifts her position in a circular direction

until she has scraped out a round hollow.

Then the cock brings stones, performing journey

after journey, returning each time with one pebble

in his beak which he deposits in front of the hen

who places it in position.

Sometimes the hollow is lined with a neat pavement

of stones placed side by side, one layer deep,

on which the hen squats, afterwards building up

the sides around her. At other times the scoop

would be filled up indiscriminately by a heap of

pebbles on which the hen then sat, working herself

down into a hollow in the middle.

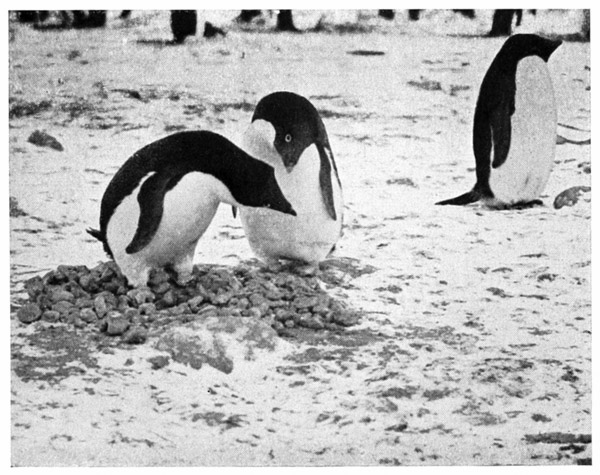

Individuals differ, not only in their building

methods, but also in the size of the stones they

select. Side by side may be seen a nest composed

wholly of very big stones, so large that it is a

matter for wonder how the birds can carry them,

and another nest of quite small stones. (Fig. 14.)

Different couples seem to vary much in character

or mood. Some can be seen quarrelling violently,

whilst others appear most affectionate, and the

tender politeness of some of these latter toward

one another is very pretty to see. (Fig. 13.)

Fig. 14. “SIDE BY SIDE … NESTS OF VERY BIG STONES AND NESTS OF VERY SMALL STONES”

(Page 26)

I may here mention that the temperatures were

rising considerably by October 19, ranging about

zero F.

During October 20 the stream of arrivals was

incessant. Some mingled at once with the crowd,

others lay in batches on the sea-ice a few yards

short of the rookery, content to have got so far,

and evidently feeling the need for rest after their

long journey from the pack. The greater part of

this journey was doubtless performed by swimming,

as they crossed open water, but I think that much

of it must have been done on foot over many miles

of sea-ice, to account for the fatigue of many of them.

Their swimming I will describe later. On the

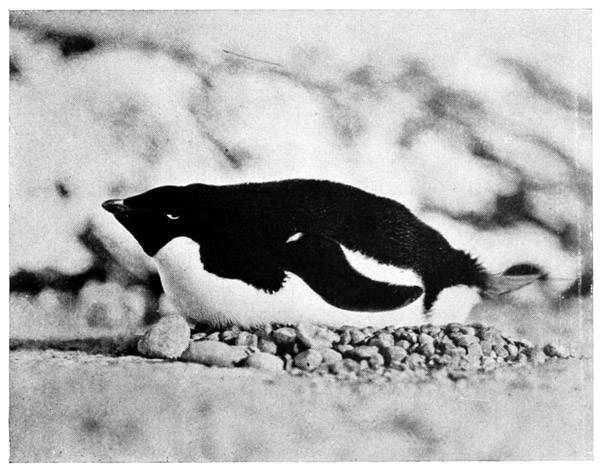

ice they have two modes of progression. The first

is simple walking. Their legs being very short,

their stride amounts at most to four inches.

Their rate of stepping averages about one hundred

and twenty steps per minute when on the march.

Their second mode of progression is “tobogganing.”

When wearied by walking or when the

surface is particularly suitable, they fall forward on

to their white breasts, smooth and shimmering with

a beautiful metallic lustre in the sunlight, and push

themselves along by alternate powerful little strokes

of their legs behind them.

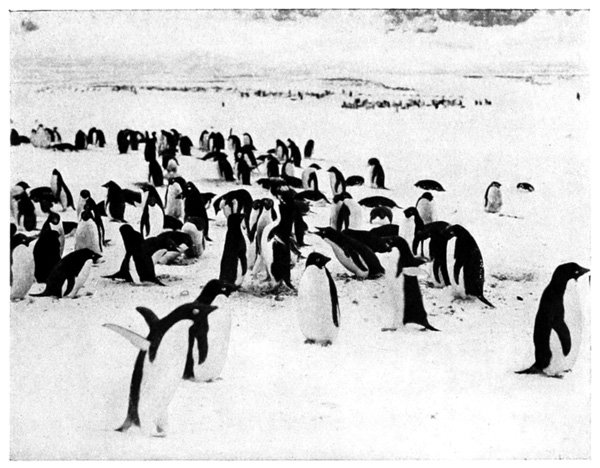

When quietly on the march, both walking and

tobogganing produce the same rate of progression,

so that the string of arriving birds, tailing out in a

long line as far as the horizon, appears as a well-ordered

procession. I walked out a mile or so

along this line, standing for some time watching it

tail past me and taking the photographs with which

I have illustrated the scene. Most of the little

creatures seemed much out of breath, their wheezy

respiration being distinctly heard.

First would pass a string of them walking, then

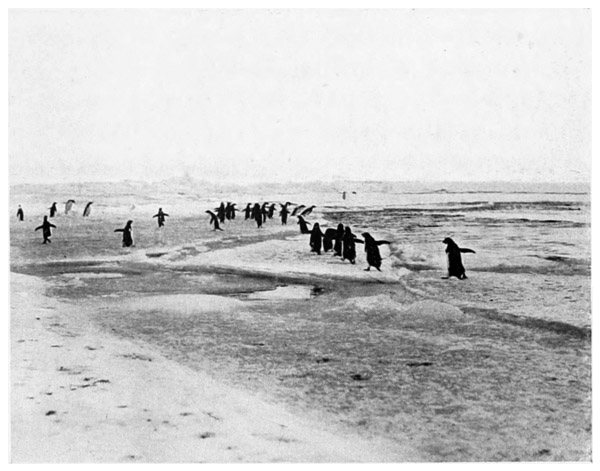

a dozen or so tobogganing. (Fig. 15.) Suddenly

those that walked would flop on to their breasts

and start tobogganing, and conversely strings of

tobogganers would as suddenly pop up on to their

feet and start walking. In this way they relieved

the monotony of their march, and gave periodical

rest to different groups of muscles and nerve-centres.

The surface of the snow on the sea-ice varied

continually, and over any very smooth patches the

pedestrians almost invariably started to toboggan,

whilst over “bad going” they all had perforce to

walk.

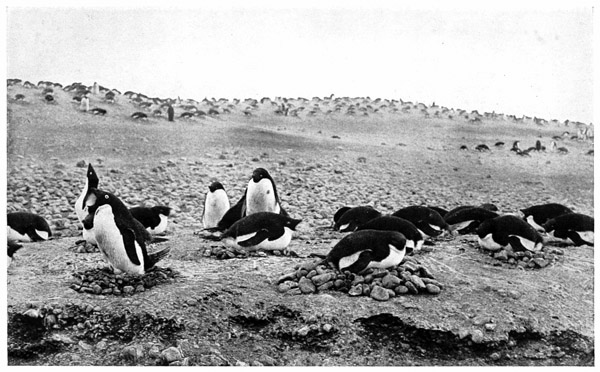

Figs. 16, 17, 18 and 19 present some idea of

the procession of these thousands on thousands of

penguins as day after day they passed into the

rookery.

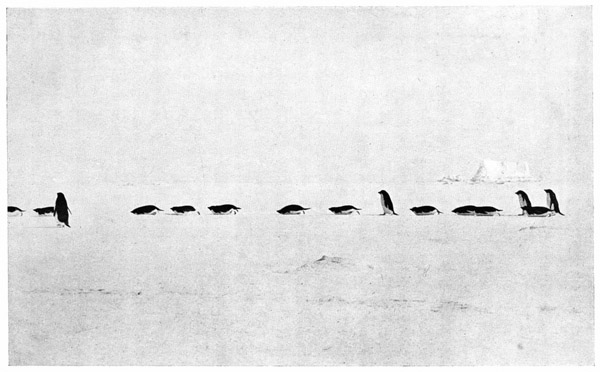

Fig. 15. ON THE MARCH TO THE ROOKERY OVER THE SEA-ICE.

SOME ARE WALKING AND SOME “TOBOGGANING”

(Page 28)

When tobogganing, turning to one side or the

other is done with one or more strokes of the

opposite flipper. When fleeing or chasing, both

flippers as well as both feet are used in propulsion,

and over most surfaces tobogganing is thus their

fastest mode of progression, but when going at full

tilt it is also the most exhausting, and after a short

spurt in this way they invariably return to the

walking position.

By October 20 many of the nests were complete,

and the hens sat in them, though no eggs were to

be seen yet. In the middle of one of the frozen

lakes rose a little island, well suited for nesting

except for the fact that later in the season, probably

about the time when the young chicks were

hatched, the lake would be thawed and the approach

to the island only to be accomplished through

about six inches or more of dirty water and ooze.

Until then, however, the surface of the lake would

remain frozen, and was at this time covered with

snow.

Not a penguin attempted to build its nest on

this island, though many passed it or walked over

it in crossing the lake. How did they realize that

later on they would get dirty every time they

journeyed to or from the spot?

Not far from this island another mound rose

from the lake, but this was connected with the

“mainland” by a narrow neck of guano-covered

pebbles. This mound was covered with nests,

showing that the birds understood this place could

always be reached over dry land. Surely this was

well worth remarking.

There was a part of the ice-foot on the south

side of the rookery where a track worn by many

ascending penguins could be seen, leading from the

sea-ice on to the beach. The place was steep and

the ice slippery, and, in fact, the track led straight

up a most difficult ascent. Not ten yards from

this well-worn track a perfectly easy slope led up

from the sea-ice to the rookery. The tracks in the

freshly fallen snow showed that only one penguin

had gone up this way. Presumably the first

arrival in that place had taken the difficult path,

and all subsequent arrivals blindly followed in his

tracks, whilst only one had had the good luck or

independence to choose the easier way.

On October 21 many thousands of penguins

arrived from the northerly direction, and poured

on to the beach in a continuous stream, the snaky

line of arrivals extending unbroken across the sea-ice

as far as the eye could see.

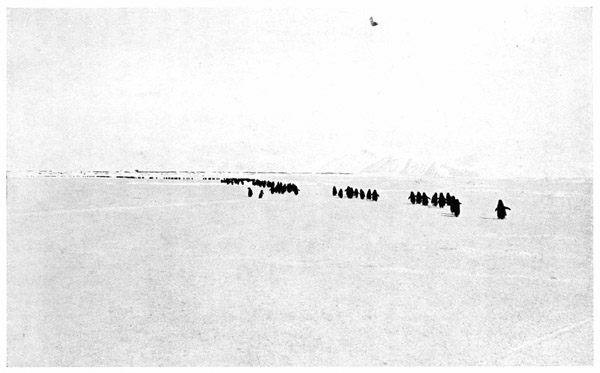

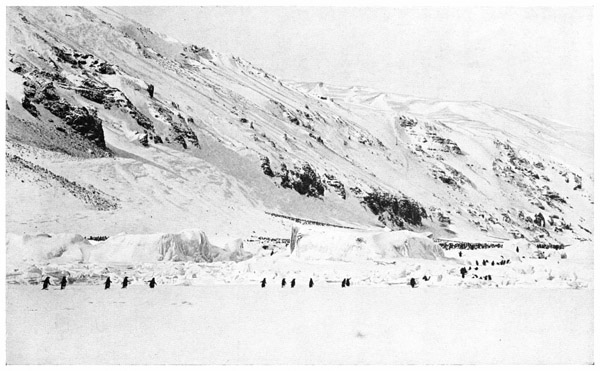

Fig. 16. PART OF THE LINE OF APPROACHING BIRDS, SEVERAL MILES IN LENGTH

(Page 28)

A great many now started to climb the heights

up the precipitous side of Cape Adare and to build

their nests as far as the summit, a height of some

1000 feet, although there was still room for many

thousand more down below. What could be their

object, considering the wearisome journeys they

would have to make to feed their young, it is

impossible to say. It might be the result of the

same spirit which made them spread out in little

scattered groups over the rookery when only a few

had arrived, and that they prefer wider room, only

putting up with the greater crowding which ensues

later as a necessary evil. There is, however, another

explanation which I will discuss in another place.

At 9 P.M. it was getting dusk, and the rookery

comparatively silent, although on some of the

knolls two or three birds might be seen still busily

working, toddling to and fro fetching stones. The

other thousands lay at rest, their white breasts flat

on the ground, and only their black beaks and

heads visible as they lay with their chins stretched

forward on the ground, whilst in place of the

massed discord of clamour heard during the day,

the separate voices of some of the busy ones

were distinct. A fine powdering of snow was

falling.

It would be difficult to estimate the number

of penguins that poured into the rookery during

the following day. There was no evidence that any

pairing had taken place on or before the march, and

the birds all had the appearance of being quite

independent.

Far away from the beach the line had become

thicker, and was no longer in single file, the

progress of the birds being slow and steady, but

when within half a mile or so from the beach,

excitement seemed to take possession of them, and

they would break into a run, hastening over the remaining

distance, the line now being a thin one,

with slight curves in it, each bird running, with

wide gait, and outstretched flippers working away

in unison with its little legs. In fact, the whole

air of the line at this time was that of a school-treat

arrived in sight of its playing-fields, and

breaking into a run in its eagerness to get there.

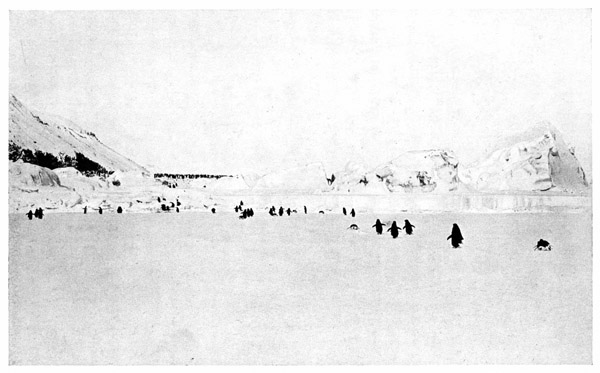

Fig. 17. ARRIVING AT THE ROOKERY

(Page 28)

Arrived at the rookery, and plunged suddenly

amidst the din of that squalling, fighting, struggling

crowd, the contrast with the dead silence and

loneliness of the pack-ice they had so recently left,

was as great a one as can well be imagined; yet

once there, the birds seemed collected and at home.

This was a matter of surprise to me then, but I

remember now my own sensations on arriving home

after my life in the Antarctic, and that I felt only

slightly the sudden return to the bustle of civilization.

Our presence among them made little or no

difference to the penguins. When we passed them

closely they would bridle up and swear or even

run at us and peck at our legs or batter them with

their flippers, but unless their nesting operations

were interfered with this attack was short-lived,

and the next moment the birds would seem to

forget our very existence. If I walked by the side

of a long, nest-covered ridge, a low growl arose

from every bird as I passed it, and the massed

sound, gathering in front and dying away behind

as I advanced, reminded me forcibly of the sound

of the crowds on the towing-path at the 'Varsity

boatrace as the crews pass up the river.

Walking actually among the nests, your temper

is tried sorely, as every bird within reach has

a peck at your legs, and occasionally a cock

attacks you bravely, battering you with his little

flippers in a manner ludicrous at first but aggravating

after a time, as the operation is painful and

severe enough to leave bruises behind it, and

naturally this begins to pall. The courage of

these little birds is most remarkable and admirable.

Our hut, being built on the rookery, could only

be approached through crowds of penguins. Those

that nested near us seemed quickly to become used

to us and to take less notice of us than those

farther off. One thing, however, terrified them

pitiably. We had to fetch ice for our water

from some stranded floes on the ice-foot, and

this we did in a little sledge. As we hauled

this rattling over the pebbly rookery it made

a good deal of noise, and in its path nests were

deserted, the occupants fleeing in the greatest confusion,

a clear road being left for the sledge, whilst

on either side a line of penguins was seen retreating

in the utmost terror. After about a minute,

they returned to their places and seemed to

forget the incident, but we were very sorry to

frighten them in this way, as we endeavoured to

live at peace with them and to molest them as little

as possible, and we feared that later on eggs might

be spilt from the nests and broken. As time went

on, those on the route of the sledge became

accustomed even to this, and we were able to

choose a course which cleared their nests.

Fig. 18. ARRIVING AT THE ROOKERY. IN THE BACKGROUND IS THE CLIFF UP WHICH MANY OF THE BIRDS CLIMB TO MAKE THEIR NESTS AT THE SUMMIT

(Page 28)

Although squabbles and encounters had been

frequent since their arrival in any numbers, it now

became manifest that there were two very different

types of battle; first, the ordinary quarrelling consequent

on disputes over nests and the robbery of

stones from these, and secondly, the battles between

cocks who fought for the hens. These last were

more earnest and severe, and were carried to a

finish, whereas the first named rarely proceeded to

extremes.

In regard to the mating of the birds, the following

most interesting customs seemed to be prevalent.

The hen would establish herself on an old nest, or

in some cases scoop out a hollow in the ground and

sit in or by this, waiting for a mate to propose

himself. (Fig. 26.) She would not attempt to

build while she remained unmated. During the

first week of the nesting season, when plenty of

fresh arrivals were continually pouring into the

rookery, she did not have long to wait as a rule.

Later, when the rookery was getting filled up,

and only a few birds remained unmated in that

vast crowd of some three-quarters of a million, her

chances were not so good.

For example, on November 16 on a knoll thickly

populated by mated birds, many of which already

had eggs, a hen was observed to have scooped a

little hollow in the ground and to be sitting in this.

Day after day she sat on looking thinner and

sadder as time passed and making no attempt to

build her nest. At last, on November 27, she had

her reward, for I found that a cock had joined her,

and she was busily building her nest in the little

scoop she had made so long before, her husband

steadily working away to provide her with the

necessary pebbles. Her forlorn appearance of the

past ten days had entirely given place to an air of

occupation and happiness.

As time went on I became certain that invariably

pairing took place after arrival at the

rookery. On October 23 I went to the place where

the stream of arrivals was coming up the beach, and

presently followed a single bird, which I afterwards

found to be a cock, to see what it was going to do.

He threaded his way through nearly the whole

length of the rookery by himself, avoiding the

tenanted knolls where the nests were, by keeping

to the emptier hollows. About every hundred yards

or so he stopped, ruffled up his feathers, closed his

eyes for a moment, then “smoothed himself out”

and went on again, thus evidently struggling against

desire for sleep after his journey. As he progressed

he frequently poked his little head forward and from

side to side, peering up at the knolls, evidently in

search of something.

Fig. 19. Adélies arriving at the Rookery

Fig. 20. A Cock carrying a Stone to his Nest

(Page 21)

Arrived at length at the south end of the

rookery, he appeared suddenly to make up his

mind, and boldly ascending a knoll which was well

tenanted and covered with nests, walked straight

up to one of these on which a hen sat. There was

a cock standing at her side, but my little friend

either did not see him or wished to ignore him

altogether. He stuck his beak into the frozen

ground in front of the nest, lifted up his head and

made as if to place an imaginary stone in front of

the hen, a most obvious piece of dumb show. The

hen took not the slightest notice nor did her mate.

My friend then turned and walked up to another

nest, a yard or so off, where another cock and hen

were. The cock flew at him immediately, and

after a short fight, in which each used his flippers

savagely, he was driven clean down the side of the

knoll away from the nests, the victorious cock

returning to his hen. The newcomer, with the

persistence which characterises his kind, came

straight back to the same nest and stood close by

it, soon ruffling his feathers and evidently settling

himself for a doze, but, I suppose, because he made

no further overtures the others took no notice of

him at all, as, overcome by sheer weariness, he

went to sleep and remained so until I was too cold

to await further developments. On my way back

to our hut I followed another cock for about thirty

yards, when he walked up to another couple at a

nest and gave battle to the cock. He, too, was

driven off after a short and decisive fight. Soon

there were many cocks on the war-path. Little

knots of them were to be seen about the rookery,

the lust of battle in them, watching and fighting

each other with desperate jealousy, and the later

the season advanced the more “bersac” they

became.

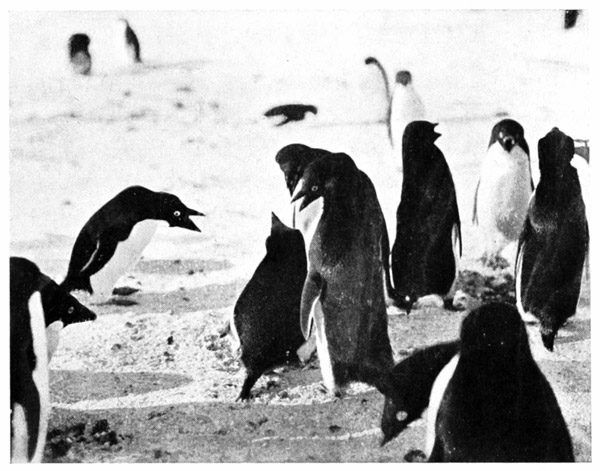

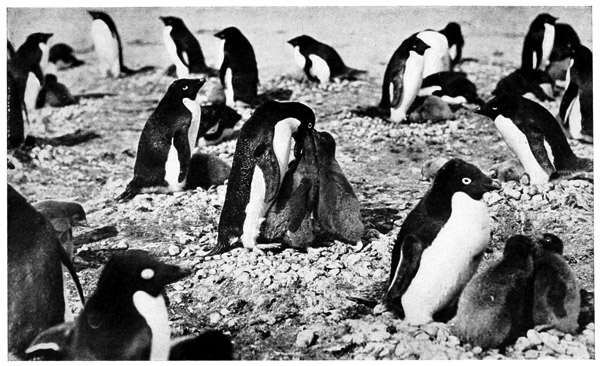

A typical scene I find described in my notes for

October 25 when I was out with my camera, and

I mention it as a type of the hundreds that were

proceeding simultaneously over the whole rockery,

and also because I was able to photograph different

stages of the proceedings as follows:

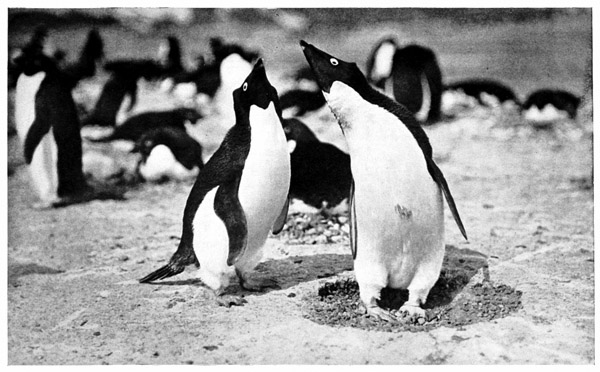

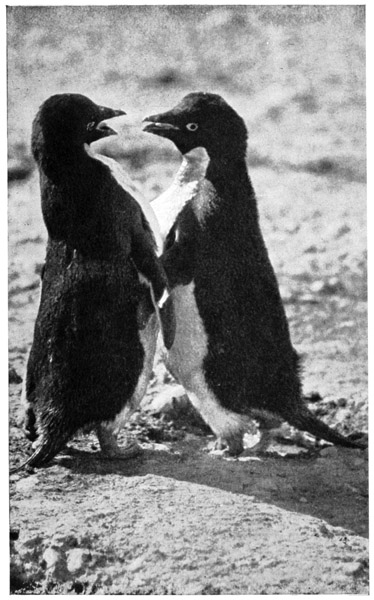

Fig. 22 shows a group of three cocks engaged

in bitter rivalry round a hen who is cowering in

her scoop in which she had been waiting as is their

custom. She appeared to be bewildered and

agitated by the desperate behaviour of the cocks.

Fig. 21. SEVERAL INTERESTING THINGS ARE TAKING PLACE HERE

(Page 43)

On Fig. 23 a further development is depicted,

and two of the cocks are seen to be squaring up for

battle. Close behind and to the right of them are

seen (from left to right) the hen and the third cock,

who are watching to see the result of the contest,

and another hen cowering for protection against a

cock with whom she has become established.

Fig. 24 shows the two combatants hard at it,

using their weight as they lean their breasts against

one another, and rain in the blows with their powerful

flippers.

Fig. 25 shows the end of the fight, the victor

having rushed the vanquished cock before him out

of the crowd and on to a patch of snow on which,

as he was too brave to turn and run, he knocked

him down and gave him a terrible hammering.

When his conqueror left him at length, he lay for

some two minutes or so on the ground, his heaving

breast alone showing that he was alive, so completely

exhausted was he, but recovering himself at

length he arose and crawled away, a damaged flipper

hanging limply by his side, and he took no further

part in the proceedings. The victorious bird rushed

back up the side of the knoll, and immediately fought

the remaining cock, who had not moved from his

original position, putting him to flight, and chasing

him in and out of the crowd, the fugitive doubling

and twisting amongst it in a frantic endeavour to get

away, and I quickly lost sight of them.

Scenes of this kind became so common all over

the rookery, that the roar of battle and thuds of

blows could be heard continuously, and of the

hundreds of such fights, all plainly had their cause

in rivalry for the hens.

When starting to fight, the cocks sometimes peck

at each other with their beaks, but always they very

soon start to use their flippers, standing up to one another

and raining in the blows with such rapidity as

to make a sound which, in the words of Dr. Wilson,

resembles that of a boy running and dragging his

hoop-stick along an iron paling. Soon they start

“in-fighting,” in which position one bird fights right-handed,

the other left-handed; that is to say, one

leans his left breast against his opponent, swinging

in his blows with his right flippers, the other presenting

his right breast and using his left flipper. My

photographs of cocks fighting all show this plainly.

It is interesting to note that these birds, though

fighting with one flipper only, are ambidextrous.

Whilst battering one another with might and main

they use their weight at the same time, and as one

outlasts the other, he drives his vanquished opponent

before him over the ground, as a trained boxing

man, when “in-fighting” drives his exhausted

opponent round the ring.

Fig. 22. Three Cocks in Rivalry

(See page 38)

Fig. 23. Two of the Cocks squaring up for Battle

(See page 38)

Desperate as these encounters are, I don't think

one penguin ever kills another. In many cases

blood is drawn. I saw one with an eye put out,

and that side of its beak (the right side) clotted

with blood, whilst the crimson print of a blood-stained

flipper across a white breast was no uncommon

sight.

Hard as they can hit with their flippers, however,

they are also well protected by their feathers, and

being marvellously tough and enduring the end

of a hard fight merely finds the vanquished bird

prostrate with exhaustion and with most of the

breath beaten out of his little body. The victor is

invariably satisfied with this, and does not seek to

dispatch him with his beak.

It was very usual to see a little group of cocks

gathered together in the middle of one of the

knolls squabbling noisily. Sometimes half a dozen

would be lifting their raucous voices at one particular

bird, then they would separate into pairs,

squaring up to one another and emphasizing their

remarks from time to time by a few quick blows

from their flippers. It seemed that each was indignant

with the others for coming and spoiling his

chances with a coveted hen, and trying to get them

to depart before he went to her.

It was useless for either to attempt overtures

whilst the others were there, for the instant he did

so, he would be set upon and a desperate fight

begin. Usually, as in the case I described above,

one of the little crowd would suddenly “see red”

and sail into an opponent with desperate energy,

invariably driving him in the first rush down the

side of the knoll to the open space surrounding it,

where the fight would be fought out, the victor returning

to the others, until by his prowess and force

of character, he would rid himself of them all. Then

came his overtures to the hen. He would, as a

rule, pick up a stone and lay it in front of her if she

were sitting in her “scoop,” or if she were standing

by it he might himself squat in it. She might take

to him kindly, or, as often happened, peck him

furiously. To this he would submit tamely, hunching

up his feathers and shutting his eyes while she

pecked him cruelly. Generally after a little of this

she would become appeased. He would rise to his

feet, and in the prettiest manner edge up to her,

gracefully arch his neck, and with soft guttural

sounds pacify her and make love to her.

Fig. 24. “Hard at it”

(See page 39)

Fig. 25. The End of the Battle

(Page 39)

Both perhaps would then assume the “ecstatic”

attitude, rocking their necks from side to side as

they faced one another (Fig. 26), and after this a

perfect understanding would seem to grow up

between them, and the solemn compact was made.

It is difficult to convey in words the daintiness

of this pretty little scene. I saw it enacted many

dozens of times, and it was wonderful to watch one

of these hardy little cocks pacifying a fractious hen

by the perfect grace of his manners.

Fig. 21 is particularly instructive. In the centre

of the picture a group of cocks are quarrelling, and

on the left-hand side three unmated hens can

be seen sitting in their scoops, whilst two of them

(the two in front) are receiving overtures from two

of the cocks who are making the most of their time

whilst the others are fighting. On the right-hand

side another cock is seen proposing himself to a

fourth hen who seems to be meeting his overtures

with the usual show of reluctance.

Although for the later arrivals a good deal

of fighting was necessary before a mate could

be secured, it seemed that some got the matter

fixed up without any difficulty at all, especially

during the earlier days when only a few birds were

scattered widely over the rookery. Later, the

cocks seemed to watch one another jealously, and

to hunt in little batches in consequence. (Figs.

27, 28, and 29.)

From the particulars I have just given it is also

evident that a wife and home once obtained could

only be kept by dint of further battling and

constant vigilance during the first stages of

domesticity, when thousands of lusty cocks were

pouring into the rookery, and it was not unusual to

see a strange cock paying court to a mated hen

in the absence of her husband until he returned

to drive away the interloper, but I do not think

that this ever occurred after the eggs had come and

the regular family life begun, couples after this

being perfectly faithful to one another.

The instance I have given of a newly arrived

cock by dumb show pretending to take a stone

and place it before a mated hen, is typical of

the sort of first overture one sees, though more

frequently an actual stone was tendered. While on

this subject I had better mention a most interesting

thing which occurred to one of my companions.

One day as he was sitting quietly on some shingle

near the ice-foot, a penguin approached him,

and after eyeing him for a little, walked right up

to him and nibbled gently at one of the legs of

his wind-proof trousers. Then it walked away,

picked up a pebble, and came back with it, dropping

it on the ground by his side. The only explanation

of this occurrence seems to be that the tendering of

the stone was meant as an overture of friendship.

Fig. 26. THE PROPOSAL. (NOTE THE HEN IN HER SCOOP)

(Pages 35 and 43)

On October 26 there was no abatement in the

stream of arrivals. The cock-fighting continued,

and many of them, temporarily disabled, were to

be seen moping about the rookery, smeared with

blood and guano. Often a hen would join in when

two cocks were fighting, occasionally going first for

one and then the other, but I never to my knowledge

saw a cock retaliate on a hen.

Once I saw two cocks fighting, and a hen taking

the part of one of the cocks, the pair of them gave

the other a fearful hammering, the hen using

her bill savagely as well as her flippers. Completely

knocked out and gasping for breath he got away at

last, only to meet another cock who fought him

and easily beat him. When this one had gone

a third came, and the poor victim with a courage

truly noble was squaring himself up with his

last spark of energy, when I interfered and drove

away his enemy.

The nests on most of the knolls soon became so

crowded that their occupants, by stretching out

their necks, could reach their neighbours without

getting up. As every hen appeared to hate her

neighbour they would peck-peck at one another

hour after hour, in the manner seen in my

photograph,(3) till their mouths and heads became

terribly sore. Occasionally they would desist, shake

their heads apparently from pain, then at it again.

In various places through the course of these

pages, reference is made to the “ecstatic” attitude

of the penguins. This antic is gone through by

both sexes and at various times, though much more

frequently during the actual breeding season. The

bird rears its body upward and stretching up its

neck in a perpendicular line, discharges a volley

of guttural sounds straight at the unresponding

heavens. At the same time the clonic movements

of its syrinx or “sound box” distinctly can be seen

going on in its throat. Why it does this I have

never been able to make out, but it appears to be

thrown into this ecstasy when it is pleased; in fact,

the zoologist of the “Pourquoi Pas” expedition

termed it the “Chant de satisfaction.” I suppose

it may be likened to the crowing of a cock or the

braying of an ass. When one bird of a pair starts

to perform in this way, the other usually starts at

once to pacify it. Very many times I saw this

scene enacted when nesting was in progress. The

two might be squatting by the nest when one would

arise to assume the “ecstatic” attitude and make

the guttural sounds in its syrinx. Immediately

the other would get close up to it and make the

following noise in a soft soothing tone:

A-ah

Always and immediately this caused the musician

to subside and settle itself down again.

Fig. 27. Cocks fighting for Hens

Fig. 28. Cocks fighting for Hens

(Page 44)

The King penguin at the Zoological Gardens,

whose sex is unknown, throws itself into the

ecstatic attitude and sings a sort of song when its

keeper strokes its neck. The blackfooted penguins

never do it, though they breed several times a year.

Figs. 26 and 32 show Adélies in ecstatic attitude.

To-day about a dozen skua gulls (Megalestris

Makormiki) appeared for the first time. They did

not start to nest, but sat on the sea-ice with a

group of penguins, in apparent amity. A few

occasionally flew about over the rookery.

On October 27 though the stream of arrivals

continued there were wide gaps in it. It appeared

to be thinning. For an hour in the forenoon it

stopped altogether, and at the end of this time a

storm of wind from the south struck us and continued

for another hour with thick drift. Probably

clear of Cape Adare the wind had been blowing

before it reached us, and had stopped the birds'

progress across the ice.

During the storm the rookery was completely

silenced, most of the birds lying with their heads to

the wind. A good many skuas arrived that day.

Some chips of white, glistening quartz had been

thrown down by our hut door recently, and later I

found two of these chips in a nest about thirty

yards away, showing up brightly against the black

basalt of which all the pebbles on the rookery were

composed.

As a rule the penguins were careful to select

rounded stones for their nests, but these fragments

of quartz were jagged and uncomfortable, and most

unsuitable for nest building. Thus it was evidently

the brightness of the stones which attracted them.

Whilst I looked on, the owners of the pieces of

quartz were wrangling with their neighbours, and

a penguin in a nest behind shot out its beak and

stole one of the pieces, placing it in its own nest.

I had brought Campbell out to show him the pieces

of quartz, and he witnessed the last incident

with me.

Fig. 29. Cocks fighting for Hens

(Page 44)

Fig. 30. Penguin on Nest

I may here mention an experiment I tried some

days later. I painted some pebbles a bright red

and had others covered with bright green cotton

material as I had no other coloured paint. Mixing

a handful of these coloured stones together I placed

them in a little heap amongst natural black ones

near a nest-covered knoll. Returning in a few

hours I found nearly all the red stones and one or

two of the green ones gone, and later found them

in nests. Later still, all the red ones had disappeared,

and last of all the green ones. I traced

nearly all these to nests, and found a few days later

that, like the pieces of white quartz, they were

being stolen from nest to nest and thus slowly

being distributed in different directions. At other

times I saw pieces of tin, pieces of glass, half a

stick of chocolate, and the head of a bright metal

teaspoon in different nests near our hut, the articles

evidently having been taken from our scrap-heap.

Thus it is evident that penguins like bright colours

and prefer red to green, as instanced by the selection

of the coloured pebbles. I am sorry that I

did not carry these colour tests further.

During October 29 the stream of arrivals was

undiminished, but the next day it slackened considerably,

and during the next two days stopped

altogether, all the rising ground of the rookery now

being literally crammed full with nests, several

thousands of them being scattered up the slopes of

Cape Adare to a height of a thousand feet.

Fig. 31. Showing the Position of the Two Eggs

Fig. 32. An Adélie in “Ecstatic” Attitude

(Page 47)

PART II

DOMESTIC LIFE OF THE ADÉLIE PENGUIN

Laying and incubation of the eggs : The Adélies'

habits in the water : Their games : Care of the young :

The later development of their social system.

On November 3 several eggs were found, and on

the 4th these were beginning to be plentiful in

places, though many of the colonies had not yet

started to lay.

Let me here call attention to the fact that up to

now not a single bird out of all those thousands

had left the rookery once it had entered it. Consequently

not a single bird had taken food of any

description during all the most strenuous part of

the breeding season, and as they did not start to

feed till November 8 thousands had to my knowledge

fasted for no fewer than twenty-seven days.

Now of all the days of the year these twenty-seven

are certainly the most trying during the life of the

Adélie.

With the exception, in some cases, of a few

hours immediately after arrival (and I believe the

later arrivals could not afford themselves even this

short respite) constant vigilance had been maintained;

battle after battle had been fought; some

had been nearly killed in savage encounters, recovered,

fought again and again with varying

fortune. They had mated at last, built their nests,

procreated their species, and, in short, met the

severest trials that Nature can inflict upon mind

and body, and at the end of it, though in many

cases blood-stained and in all caked and bedraggled

with mire, they were as active and as brave as ever.

When one egg had been laid the hen still sat on

the nest. The egg had to be continually warmed,

and as the temperature was well below freezing-point,

exposure would mean the death of the

embryo.

In order to determine the period between the

laying of the two eggs, I numbered seven nests

with wooden pegs, writing on the pegs the date on

which each egg was laid. The result obtained is

shown on page 53.

The average interval in the four cases where two

eggs were laid being 3·5 days.

Fig. 33. Floods

(Page 66)

No. 7 nest was that of the hen which I mentioned

as having waited for so long for a mate,

and the lateness of the date on which the first

egg appeared may have resulted in there being

no other.

| Date of appearance of first egg | Date of appearance of second egg | Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. 1 nest | Nov. 14 | — | Only 1 laid |

| No. 2 nest | Nov. 13 | Nov. 16 | 3 days |

| No. 3 nest | Nov. 14 | Nov. 17 | 3 days |

| No. 4 nest | |||

| No. 5 nest | Nov. 12 | Nov. 16 | 4 days |

| No. 6 nest | Nov. 8 | Nov. 12 | 4 days |

| No. 7 nest | Nov. 24 | — | Only 1 laid |

The only notes I have on the incubation period

are that the first chick appeared in No. 5 nest on

December 19 (incubation period thirty-seven days)

and in No. 7 nest on December 28 (incubation

period thirty-four days).

The skuas had increased considerably in numbers

by November 4, and frequently came to the scrap-heap

outside our hut. Here were many frozen

carcasses of penguins which we had thrown there

after the breasts had been removed for food during

the past winter. The skuas picked the bones quite

clean of flesh, so that the skeletons lay white under

the skins, and it was remarkable to what distances

they sometimes carried the carcasses, which weighed

considerably more than the skuas themselves. I

found some of these bodies over five hundred yards

away.

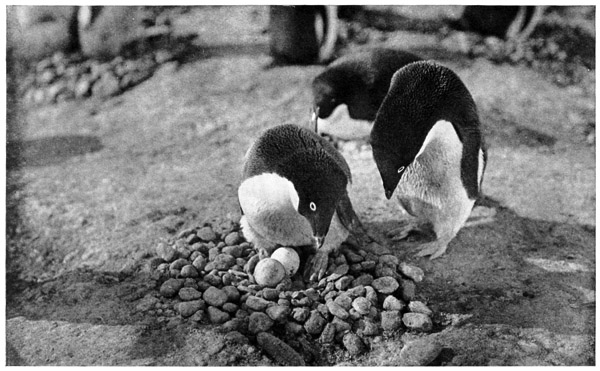

A perpetual feud was carried on between the

penguins and the skuas. The latter birds come to

the south in the summer, and make their nests

close to, and in some cases actually among, those of

the penguins, and during the breeding time live

almost entirely on the eggs, and later, on the chicks.

They never attack the adult penguins, who run at

them and drive them away when they light within

reach, but as the skuas can take to the wing and

the penguins cannot, no pursuit is possible.

Fig. 34. Flooded

Fig. 35. A Nest with Stones of Mixed Sizes

The skuas fly about over the rookery, keeping only

a few yards from the ground, and should one of them

see a nest vacated and the eggs exposed, if only for

a few seconds, it swoops at this, and with scarcely

a pause in its flight, picks up an egg in its beak

and carries it to an open space on the ground, there

to devour the contents. Here then was another

need for constant vigilance, and so daring did the

skuas become, that often when a penguin sat on

a nest carelessly, so as to leave one of the eggs

protruding from under it, a lightning dash from a

skua would result in the egg being borne triumphantly

away.

The bitterness of the penguins' hatred of the skuas

was well shown in the neighbourhood of our scrap-heap.

None of the food thrown out on to this heap

was of the least use to the penguins, but we noticed

after a time that almost always there were one or

more penguins there, keeping guard against the

skuas, and doing their utmost to prevent them from

getting the food, and never allowing them to light

on the heap for more than a few seconds at a time.

In fact, a constant feature of this heap was the

sentry penguin, darting hither and thither, aiming

savage pecks at the skuas, which would then rise a