The Project Gutenberg eBook of Hunting in Many Lands: The Book of the Boone and Crockett Club

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Hunting in Many Lands: The Book of the Boone and Crockett Club

Editor: Theodore Roosevelt

George Bird Grinnell

Release date: August 18, 2011 [eBook #37122]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Linda Hamilton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HUNTING IN MANY LANDS: THE BOOK OF THE BOONE AND CROCKETT CLUB ***

THE CROWN OF CHIEF MOUNTAIN FROM THE SOUTHEAST.

Hunting

In Many Lands

EDITORS

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL

NEW-YORK

FOREST AND STREAM PUBLISHING COMPANY

1895

Copyright, 1895, by

Forest and Stream Publishing Company

Forest and Stream Press,

New York, N. Y., U. S. A.

Contents

| Page | |

|---|---|

| Hunting in East Africa | 13 |

| W. A. Chanler. | |

| To the Gulf of Cortez | 55 |

| George H. Gould. | |

| A Canadian Moose Hunt | 84 |

| Madison Grant. | |

| A Hunting Trip in India | 107 |

| Elliott Roosevelt. | |

| Dog Sledging in the North | 123 |

| D. M. Barringer. | |

| Wolf-Hunting in Russia | 151 |

| Henry T. Allen. | |

| A Bear-Hunt in the Sierras | 187 |

| Alden Sampson. | |

| The Ascent of Chief Mountain | 220 |

| Henry L. Stimson. | |

| The Cougar | 238 |

| Casper W. Whitney. | |

| Big Game of Mongolia and Tibet | 255 |

| W. W. Rockhill. | |

| Hunting in the Cattle Country | 278 |

| Theodore Roosevelt. | |

| Wolf-Coursing | 318 |

| Roger D. Williams. | |

| Game Laws | 358 |

| Charles E. Whitehead. | |

| Protection of the Yellowstone National Park | 377 |

| George S. Anderson. | |

| The Yellowstone National Park Protection Act | 403 |

| George S. Anderson. | |

| Head-Measurements of the Trophies at the Madison Square Garden Sportsmen's Exposition | 424 |

| National Park Protective Act | 433 |

| Constitution of the Boone and Crockett Club | 439 |

| Officers of the Boone and Crockett Club | 442 |

| List of Members | 443 |

List of Illustrations

| Crown of Chief Mountain | Frontispiece | |

| From the southeast. One-half mile distant. Photographed by Dr. Walter B. James. | ||

| Facing Page | ||

|---|---|---|

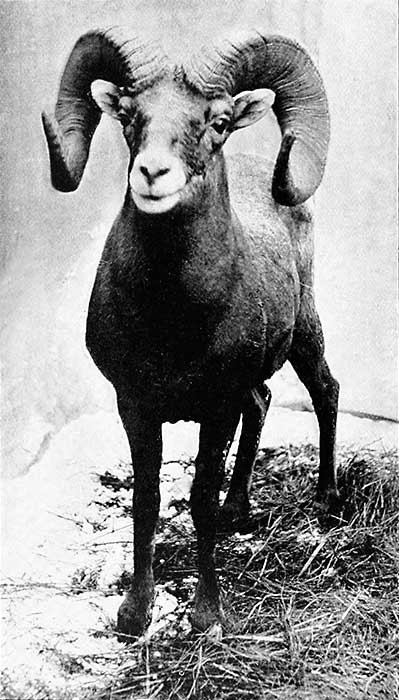

| A Mountain Sheep | 55 | |

| Photographed from Life. From Forest and Stream. | ||

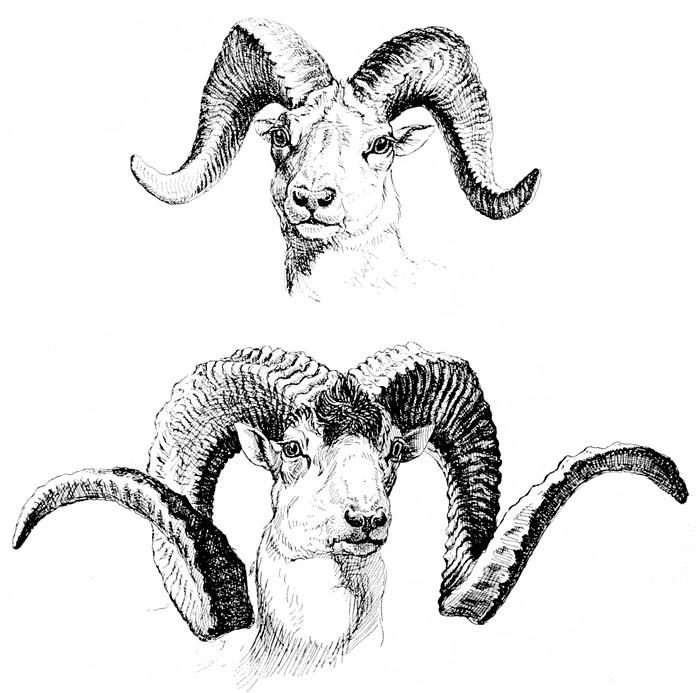

| Rocky Mountain and Polo's Sheep | 75 | |

| The figures are drawn to the same scale and show the difference in the spread of horns. From Forest and Stream. | ||

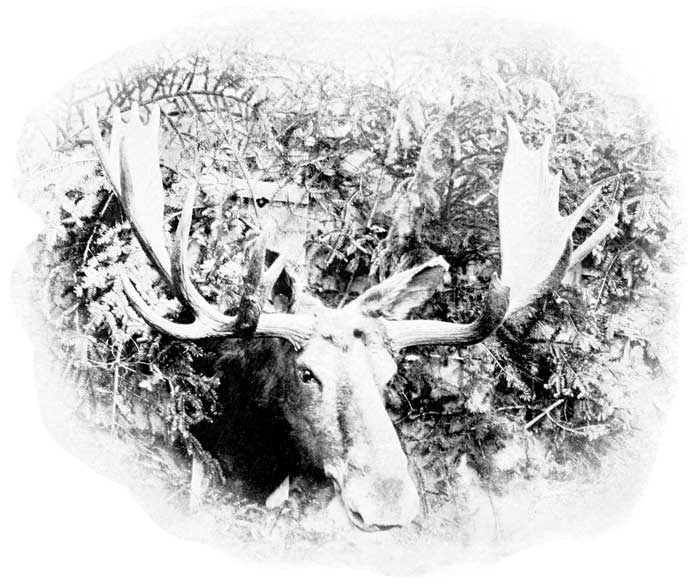

| A Moose of the Upper Ottawa | 85 | |

| Killed by Madison Grant, October 10, 1893. | ||

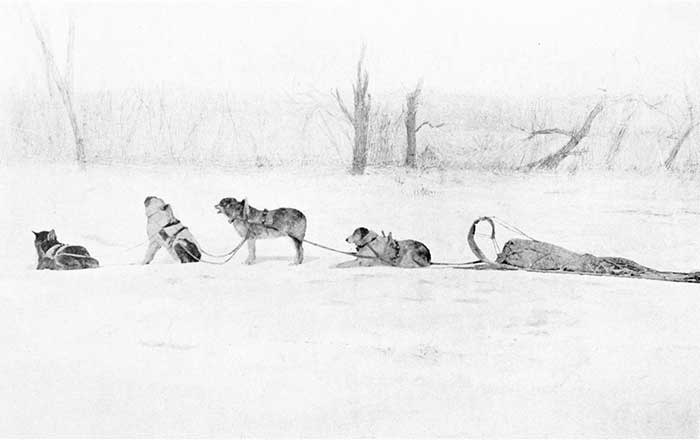

| How our Outfit was Carried | 123 | |

| Photographed by D. M. Barringer. | ||

| Outeshai, Russian Barzoi | 151 | |

| Winner of the hare-coursing prize at Colombiagi (near St. Petersburg) two years in succession. In type, however, he is faulty. | ||

| Fox-hounds of the Imperial Kennels | 177 | |

| The men and dogs formed part of the hunt described. | ||

| The Chief's Crown from the East | 229 | |

| Photographed by Dr. Walter B. James. Distance, two miles. | ||

| Yaks Grazing | 255 | |

| Photographed by Hon. W. W. Rockhill. | ||

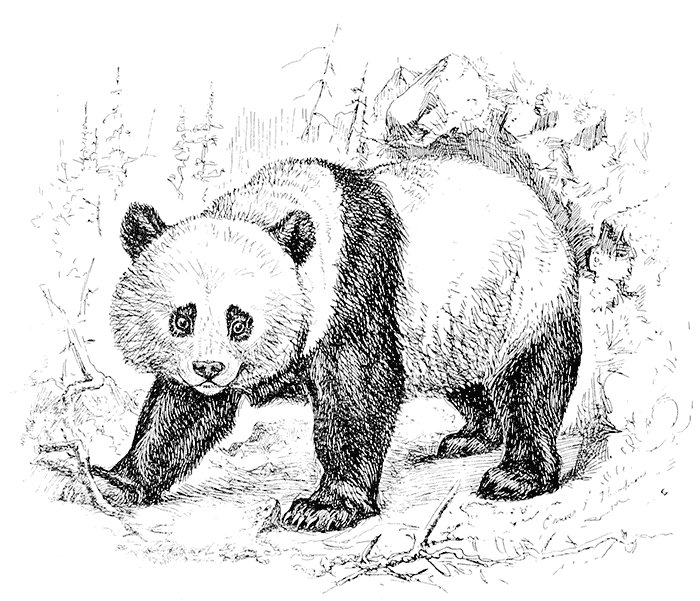

| Ailuropus Melanoleucus | 263 | |

| From Forest and Stream. | ||

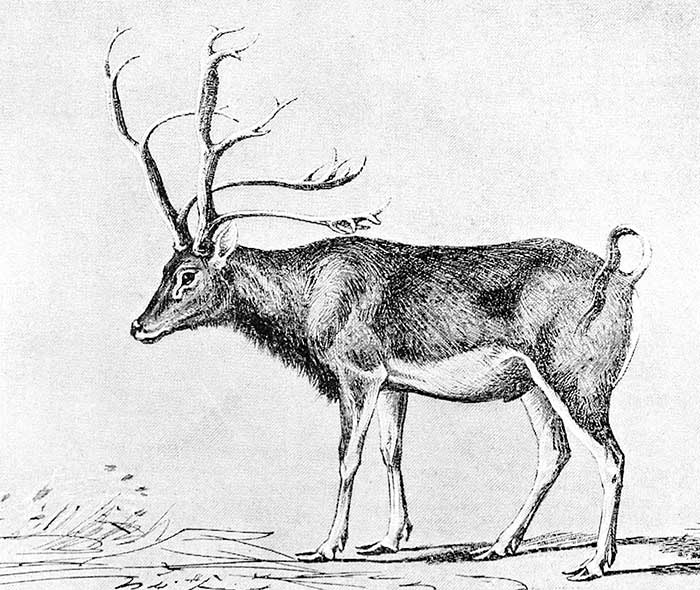

| Elaphurus Davidianus | 271 | |

| The Wolf Throwing Zlooem, the Barzoi | 319 | |

| From Leslie's Weekly. | ||

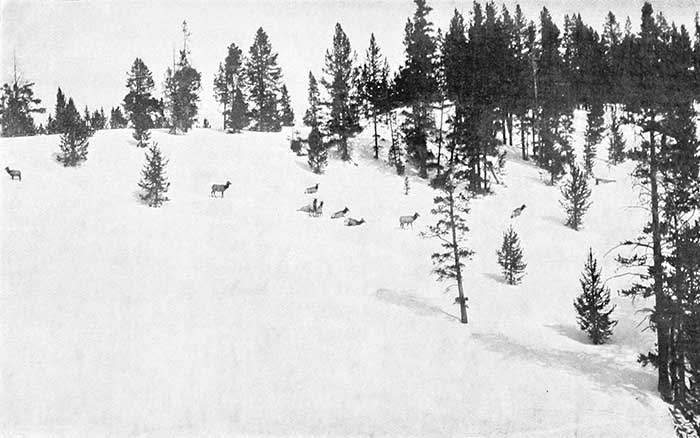

| Yellowstone Park Elk | 377 | |

| From Forest and Stream. | ||

| A Hunting Day | 395 | |

| From Forest and Stream. | ||

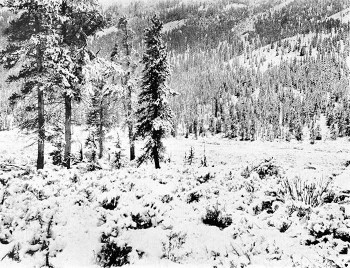

| In Yellowstone Park Snows | 413 | |

| From Forest and Stream. | ||

| On the Shore of Yellowstone Lake | 419 | |

| From Forest and Stream. | ||

Note.—The mountain sheep's head on the cover is from a photograph

of the head of the big ram killed by Mr. Gould in Lower California,

as described in the article "To the Gulf of Cortez."

Preface

The first volume published by the Boone

and Crockett Club, under the title "American

Big Game Hunting," confined itself, as its

title implied, to sport on this continent. In

presenting the second volume, a number of

sketches are included written by members who

have hunted big game in other lands. The

contributions of those whose names are so

well known in connection with explorations

in China and Tibet, and in Africa, have an

exceptional interest for men whose use of the

rifle has been confined entirely to the North

American continent.

During the two years that have elapsed

since the appearance of its last volume, the

Boone and Crockett Club has not been idle.

The activity of its members was largely instrumental

in securing at last the passage by

Congress of an act to protect the Yellowstone

National Park, and to punish crimes and offenses

within its borders, though it may be

questioned whether even their efforts would

have had any result had not the public interest

been aroused, and the Congressional conscience

pricked, by the wholesale slaughter

of buffalo which took place in the Park in

March, 1894, as elsewhere detailed by Capt.

Anderson and the editors. Besides this, the

Club has secured the passage, by the New

York Legislature, of an act incorporating the

New York Zoölogical Society, and a considerable

representation of the Club is found in the

list of its officers and managers. Other efforts,

made by Boone and Crockett members

in behalf of game and forest protection, have

been less successful, and there is still a wide

field for the Club's activities.

Public sentiment should be aroused on the

general question of forest preservation, and

especially in the matter of securing legislation

which will adequately protect the game and

the forests of the various forest reservations

already established. Special attention was

called to this point in the earlier volume published

by the Club, from which we quote:

If it was worth while to establish these reservations, it is worth

while to protect them. A general law, providing for the adequate

guarding of all such national possessions, should be enacted by Congress,

and wherever it may be necessary such Federal laws should be

supplemented by laws of the States in which the reservations lie. The

timber and the game ought to be made the absolute property of the

Government, and it should be constituted a punishable offense to

appropriate such property within the limits of the reservation. The

game and timber on a reservation should be regarded as Government

property, just as are the mules and the cordwood at an army post. If

it is a crime to take the latter, it should be a crime to plunder a forest

reservation.

In these reservations is to be found to-day every species of large

game known to the United States, and the proper protection of the

reservations means the perpetuating in full supply of all the indigenous

mammals. If this care is provided, no species of American large game

need ever become absolutely extinct; and intelligent effort for game

protection may well be directed toward securing through national

legislation the policing of forest preserves by timber and game

wardens.

A really remarkable phenomenon in American

animal life, described in the paper on the

Yellowstone Park Protection Act, is the attitude

now assumed toward mankind by the

bears, both grizzly and black, in the Yellowstone

National Park. The preservation of the

game in the Park has unexpectedly resulted in

turning a great many of the bears into scavengers

for the hotels within the Park limits.

Their tameness and familiarity are astonishing;

they act much more like hogs than beasts of

prey. Naturalists now have a chance of studying

their character from an entirely new standpoint,

and under entirely new conditions. It

would be well worth the while of any student

of nature to devote an entire season in the Park

simply to study of bear life; never before has

such an opportunity been afforded.

The incident mentioned on page 421 was

witnessed by Mr. W. Hallett Phillipps and

Col. John Hay. Since this incident occurred,

one bear has made a practice of going into the

kitchen of the Geyser Hotel, where he is fed

on pies. If given a chance, the bears will eat

the pigs that are kept in pens near the hotels;

but they have not shown any tendency to molest

the horses, or to interfere in any way with

the human beings around the hotels.

These incidents, and the confidence which

the elk, deer and other animals in the Park

have come to feel in man, are interesting, for

they show how readily wild creatures may be

taught to look upon human beings as friends.

George Bird Grinnell.

New York, August 1, 1895.

Hunting in Many Lands

Hunting in East Africa

In the month of July, 1889, I was encamped

in the Taveta forest, 250 miles from the east

coast, and at the eastern foot of Mt. Kilimanjaro.

I was accompanied by my servant,

George Galvin, an American lad seventeen

years old, and had a following of 130 Zanzibaris.

My battery consisted of the following

weapons: one 8-bore smooth, using a cartridge

loaded with 10 drams of powder and a 2-ounce

spherical ball; one .577 and one .450 Express

rifle, and one 12-bore Paradox. All these were

made by Messrs. Holland & Holland. My

servant carried an old 12-bore rifle made by

Lang (intended to shoot 4-1/2 drams of powder,

but whose cartridges he recklessly loaded with

more than 7) and a .45-90 Winchester of the

model of 1886.

Taveta forest has been often described by

pens far abler than mine, so I will not attempt

to do this. It is inhabited by a most friendly

tribe of savages, who at the time of my visit

to them possessed sufficient food to be able to

supply the wants of my caravan. I therefore

made it a base at which I could leave the major

part of my following, and from which I could

with comfort and safety venture forth on shooting

trips, accompanied by only a few men.

The first of these excursions was made to

the shores of Lake Jipé, six hours' march from

Taveta, for the purpose of shooting hippos. I

took with me my whole battery and thirteen

men. This unlucky number perhaps influenced

my fortunes, for I returned to Taveta empty

handed and fever stricken, after a stay on the

shores of the lake lasting some days. However,

my experiences were interesting, if only

because they were in great measure the result

of ignorance. Up to this time my sporting experience

had dealt only with snipe and turkey

shooting in Florida, for on my road from the

coast, the little game seen was too wary to give

me a chance of putting a rifle to my shoulder.

The shores of Lake Jipé, where I pitched

my tent, were quite flat and separated from the

open water of the lake by a wide belt of swamp

growth. I had brought with me, for the purpose

of constructing a raft, several bundles of

the stems of a large palm growing in Taveta.

These were dry and as light as cork. In

a few hours' time my men constructed a raft,

fifteen feet in length and five feet in width.

On trial, it was found capable of supporting

two men, but even with this light load it sank

some inches below the surface of the water. I

fastened a deal box on the forward end as seat,

and instructed one of the men, who said he

understood boatman's work, to stand in the

stern and punt the craft along with a pole.

During the night my slumbers were constantly

disturbed by the deep, ominous grunting of

hippopotami, which, as if to show their contempt

for my prowess, chose a path to their

feeding grounds which led them within a few

yards of my camp. The night, though starlit,

was too dark for a shot, so I curbed my impatience

till the morning.

As most people are aware, the day begins in

the tropics as nearly as possible at 6 o'clock

and lasts twelve hours. Two hours before

dawn I was up and fortifying myself against the

damp morning air with a good breakfast of

roast chicken, rice and coffee. My men, wrapped

in their thin cotton shirts, lay about the

fires on the damp ground, seemingly unmindful

of rheumatism and fever, and only desirous to

sleep as long as possible. I awoke my crew at

a little after 5, and he, unassisted, launched the

raft. The swamp grass buoyed it up manfully,

so that it looked as if it disdained to touch the

yellow waters of the lake. When it had been

pushed along till the water was found to be two

feet deep, I had myself carried to the raft and

seated myself on the box. I was clad only in

a flannel shirt, and carried my .577 with ten

rounds of ammunition. As we slowly started

on our way, my men woke up one by one, and

shouted cheering words to us, such as, "Look

out for the crocodiles!" "If master dies, who'll

pay us!" These cries, added to the dismal

chill of the air and my boatman's only too apparent

dislike of his job, almost caused me to

turn back; but, of course, that was out of the

question.

Half an hour from the shore found me on

the edge of the open water, and, as if to endorse

my undertaking, day began to break. That

sunrise! Opposite me the rough outlines of

the Ugucno Mountains, rising several thousand

feet, lost their shadows one by one, and far to

the right towered Mt. Kilimanjaro, nearly four

miles high, its snowy rounded top roseate with

the soft light of dawn. But in Africa at least

one's higher sensibilities are dulled by the animal

side of his nature, and I fear I welcomed

the sun more for the warmth of its rays than

for the beautiful and fleeting vision it produced.

Then the hippos! While the sun was rising my

raft was not at rest, but was being propelled by

slow strong strokes toward the center of the

lake, and as the darkness lessened I saw the

surface of the lake dotted here and there by

spots, which soon resolved themselves into the

black, box-like heads of my game. They were

to all appearance motionless and appeared quite

unconscious or indifferent to the presence, in

their particular domain, of our strange craft

and its burden.

I approached them steadily, going more

slowly as the water grew deeper, and more

time was needed for the pulling out and dipping

in of the pole. When, however, I had

reached a position some 150 yards from the

nearest group, five in number, they all with a

loud snort faced me. I kept on, despite the

ardent prayer of the boatman, and when within

100 yards, and upon seeing three of the hippos

disappear beneath the surface, I took careful

aim and fired at the nearest of the remaining

two. I could see the splash of my bullet as it

skipped harmlessly along the surface of the

lake, and knew I had missed. At once all heads

in sight disappeared. There must have been

fifty in view when the sun rose. Presently,

one by one, they reappeared, and this time, as

if impelled by curiosity, came much closer than

before. I took aim at one not fifty yards away,

and could hear the thud of the bullet as it

struck. I thought, as the hippo at once disappeared,

that it was done for. I had not yet

learned that the brain of these animals is very

small, and that the only fatal shot is under

the ear.

After this shot, as after my first, all heads

vanished, but this time I had to wait much

longer ere they ventured to show themselves.

When they did reappear, however, it was too

close for comfort. One great head, blinking

its small eyes and holding its little horselike

ears at attention, was not twenty feet away,

and another was still closer on my other side.

While hesitating at which to shoot I lost my

opportunity, for they both ducked simultaneously.

I was riveted to my uncomfortable seat, and

I could hear my boatman murmuring "Allah!"

with fright, when slowly, but steadily, I felt the

raft rise under my feet. Instinctively I remembered

I had but one .577 rifle, and hastened,

my hands trembling, to fasten it with a loose

rope's end to the raft. My boatman yelled

with terror, and at that fearful cry the raft

splashed back in the water and all was again

still. One of the hippos, either with his back

or head, must have come in contact with the

bottom of the raft as he rose to the surface.

How far he would have gone had not the

negro screamed I do not know, but as it was

it seemed as if we were being held in mid air

for many minutes. I fancy the poor brute was

almost as frightened as we were, for he did

not reappear near the raft.

I now thought discretion the better part of

valor, and satisfied myself with shooting at the

animal from a somewhat greater distance. I hit

two more in the head and two—who showed

a good foot of their fat bodies above the water—in

the sides. None floated on the surface,

legs up, as I had been led to expect they would

do; but the men assured me that they never

come to the surface till sundown, no matter

what time of day they may have been shot.

This, needless to state, I afterward found, is

not true. My ammunition being exhausted,

and the sun blazing hot, I returned to camp.

I awoke the next day feeling anything but

energetic; nevertheless, I set out to see what

game the land held ready for the hunter, dissatisfied

with his experiences on water. The

country on the eastern side of Lake Jipé is

almost flat, but is dotted here and there with

low steep gneiss hills, stretching in an indefinite

line parallel to the lake and some three miles

distant from it. I made my way toward these

hills. On the way I put up some very small

antelope, which ran in such an irregular manner

that they presented no mark to my unskilled

arm.

We reached the hills, and I climbed one and

scanned the horizon with my glasses. Far to

the northwest I spied two black spots in a grassy

plain. I gave the glasses to my gun-bearer

and he at once said, "Rhinoceros!" I had

never seen these beasts except in a menagerie,

and the mention of the name brought me to my

feet eager to come to a closer acquaintance

with them. The wind blew toward me and the

game was too far for the need of caution, so I

walked rapidly in their direction. When I got

to within 250 yards, I could quite easily distinguish

the appearance of my quarry. They

were lying down and apparently oblivious to

my approach—perhaps asleep. My gun-bearer

(a Swahili) now began to show an anxiety to

turn back. This desire is, in many cases, the

distinguishing trait of this race. On we went,

but now cautiously and silently. The grass

was about two feet high, so that by crawling

on hands and knees, one could conceal most of

his body. But this position is not a pleasant

one with a blazing sun on the back, rough soil

under the knees and a thirteen-pound rifle in

the hand.

We got to within fifty yards. I looked back

for the negro with my .577. He was lying

flat on his stomach fifty yards to the rear. I

stood up to beckon him, but he did not move.

The rhinos did, and my attention was recalled

to them by hearing loud snorts, and, turning

my head, I saw the two beasts on their feet

facing me. I had never shot an 8-bore in my

life before, so it is not to be wondered at that

the shock of the recoil placed me on my back.

The animals were off before I could recover

my feet, and my second barrel was not discharged.

I ran after them, but the pace of a

rhino is much faster than it looks, and I soon

found pursuit useless. I returned to the place

where they had lain, and on looking about

found traces of fresh blood. My gun-bearer,

as an explanation for his behavior, said that

rhinos were devils, and were not to be approached

closely. He said I must be possessed

of miraculous power, or they would have charged

and slain me. The next day, fever laid me

low, and, though the attack was slight, some

days elapsed before I could muster strength to

take me back to Taveta.

After a few days' rest in camp—strengthened

by good food and spurred to fresh exertion by

the barren result of my first effort—I set out

again, accompanied by more men and in a different

direction.

My faith in myself received a pleasant encouragement

the day before my departure.

My head man came to me and said trade was

at a standstill, and that the natives could not

be induced to bring food to sell. On asking

him why, I learned that the Taveta people

had found three dead hippos in Lake Jipé and

one rhino near its shores. Meat—a rare treat

to them, even when not quite fresh—filled their

minds and bodies, and they were proof even

against the most tempting beads and the brightest

cloths. I cannot say that I shared my

head man's anxiety. The fact that I had not

labored altogether in vain, even though others

reaped the benefit of my efforts, filled me with

a certain satisfaction.

A day's march from Taveta brought me to

the banks of an almost stagnant brook, where I

made camp. The country round about was a

plain studded with low hills, here thinly thatched

with short grass, and there shrouded with

thick bush, above which every now and then

rose a giant acacia. The morning after my

arrival, I set out from camp with my 8-bore in

my hands and hope in my heart. Not 200

yards from my tent, I was startled by a snort

and then by the sight of two rhinos dashing

across my path some fifty yards away. This

time I did not succumb to my gun's recoil, but

had the doubtful satisfaction of seeing, from a

standing position, the animals disappear in the

bush. I made after them and found, to my

delight, a clear trail of fresh blood. Eagerly

pressing on, I was somewhat suddenly checked

in my career by almost stumbling over a rhino

apparently asleep on its side, with its head

toward me. Bang! went the 8-bore and down

I went. I was the only creature disturbed by

the shot, as the rhino had been dead some

minutes—slain by my first shot; and my satisfaction

was complete when I found the hole

made by my bullet. My men shouted and sang

over this, the first fruits of my expedition,

and even at this late day I forgive myself for

the feeling of pride I then experienced. I

have a table at home made of a piece of this

animal's hide, and supported in part by one of

its horns.

The next day I made an early start and

worked till 4 o'clock P. M., with no result.

Then, being some eight miles from camp, I

turned my face toward home. I had not gone

far, and had reached the outskirts of an almost

treeless savanna, when my gun-bearer brought

me to a halt by the word mbogo. This I knew

meant buffalo. I adjusted my glass and followed

the direction of my man's finger. There,

500 yards away, I saw a solitary buffalo feeding

slowly along toward two low bushes, but on

the further side of them. I did not think what

rifle I held (it was a .450), but dashed forward

at once. My gun-bearer was more thoughtful

and brought with him my .577. We actually

ran. When within eighty or ninety yards of

the two bushes behind which the beast was

now hidden. I slackened pace and approached

more cautiously. My heart was beating and

my hands trembling with the exertion of running

when I reached the nearest bush, and my

nerves were not exactly steadied by meeting

the vicious gaze of a large buffalo, who stood

not thirty feet on the other side. My gun-bearer

in an instant forced the .577 into my

hands, and I took aim at the shoulder of the

brute and fired, without knowing exactly what

I was doing. The smoke cleared, and there,

almost in his tracks, lay my first buffalo. His

ignorance of my noisy and careless approach

was apparently accounted for by his great age.

His hide was almost hairless and his horns

worn blunt with many encounters. He must

have been quite deaf and almost blind, or his

behavior cannot be accounted for. The noise

made by our approach, even with the favorable

wind, was sufficient to frighten any animal, or

at least put it on its guard.

My men, who were dreadfully afraid of big

game of all sorts, when they saw the buffalo

lying dead, danced with joy and exultation.

They kicked the dead body and shouted curses

at it. Camp was distant a good two hours'

march, and the day was drawing to a close.

The hungry howl of the hyenas warned me

that my prize would soon be taken from me

were it left unguarded. So piles of firewood

were made and the carcass surrounded by a

low wall of flames. I left three men in charge

and set out for camp. There was but little

light and my way lay through bits of forest

and much bush. Our progress was slow, and

my watch read 10:30 P. M. before I reached

my tent and bed.

The following day I set out for a shooting

ground distant two days' march from where I

had been camped. Several rivers lay in my

path and two tribes of natives. These natives

inhabit thick forest and are in terror of strangers,

as they are continually harassed by their

neighbors. When they saw the smallness of

my force, however, they endeavored to turn me

aside, but without success. Quiet and determination

generally win with these people. The

rivers gave me more trouble, as they were deep

and swift of current, and my friends, the natives,

had removed all bridges. But none of the

streams exceeded thirty feet in width, and an

hour's hard work with our axes always provided

us with a bridge.

The second day from my former camp

brought me to the outskirts of the forest and

the beginning of open country. I had hardly

made camp before three Swahili traders came

to me, and after the usual greetings began to

weep in chorus. Their story was a common one.

They had set out from Mombasa with twelve

others to trade for slaves and ivory with the

natives who inhabit the slopes of Kilimanjaro.

Fortune had favored them, and after

four months they were on their way homeward

with eighteen slaves and five good sized tusks.

The first day's journey was just over when they

were attacked by natives, three of their number

slain and all their property stolen. In

the darkness they could not distinguish what

natives attacked them; but their suspicions

rested on the very tribe among whom they had

spent the four months, and from whom they

had purchased the ivory and slaves. I gave

them a little cloth and some food, and a note

to my people at Taveta to help them on their

way. Of course, they were slave traders, and

as such ought possibly to have been beaten

from my camp. But it is undoubtedly a fact

that Mahomedans look on slave trading as a

perfectly legitimate occupation; and if people

are not breaking their own laws, I cannot see

that a stranger should treat them as brigands

and refuse them the least aid when in distress.

I know that my point of view in this matter

has few supporters in civilization.

The next day, after a short march, I pitched

my tent on the banks of a small stream, and

then set out to prospect for game. I found

nothing, but that night my slumbers were disturbed

by the splashing and grunting of a

herd of buffalo drinking.

These sounds kept me awake, so that I was

enabled to make a very early start—setting out

with four men at 4:45. The natives had assured

me that the buffalo came to drink about

midnight, and then fed slowly back to their

favorite sleeping-places in the thick bush,

reaching there just about sunrise. By making

such an early start I hoped to come up with my

quarry in the open places on the edge of the

thick bush just before dawn, when the light is

sufficiently bright to enable one to see the foresight

of a rifle. Dew falls like rain in this part

of the world, and we had not gone fifty paces

in the long grass before we were soaking wet,

and dismally cold to boot. My guide, cheered

by the prospect of a good present, led us confidently

along the most intricate paths and

through the thickest bush. The moon overhead,

which was in its fifteenth day, gave excellent

light. Every now and then some creature

would dash across our path, or stand snorting

fearfully till we had passed. These were probably

waterbuck and bushbuck. Toward half

past five the light of the moon paled before

the first glow of dawn, and we found ourselves

on the outskirts of a treeless prairie, dotted

here and there with bushes and covered with

short dry grass. Across this plain lay the bush

where my guide assured me the buffalo slept

during the day, and according to him at that

moment somewhere between me and this bush

wandered at least 100 buffalo. There was little

wind, and what there was came in gentle puffs

against our right cheeks. I made a sharp

detour to the left, walking quickly for some

twenty minutes. Then, believing ourselves to

be below the line of the buffalo, and therefore

free to advance in their direction, we did so.

Just as the sun rose we had traversed the

plain and stood at the edge of what my men

called the nyumba ya mbogo (the buffalo's home).

We were too late. Fresh signs everywhere

showed that my guide had spoken the truth.

Now I questioned him as to the bush; how

thick it was, etc. At that my men fidgeted uneasily

and murmured "Mr. Dawnay." This

young Englishman had been killed by buffalo

in the bush but four months before. However,

two of my men volunteered to follow me, so I

set out on the track of the herd.

This bush in which the buffalo live is not

more than ten feet high, is composed of a network

of branches and is covered with shiny

green leaves; it has no thorns. Here and

there one will meet with a stunted acacia,

which, as if to show its spite against its more

attractive neighbors, is clothed with nothing

but the sharpest thorns. The buffalo, from

constant wandering among the bush, have

formed a perfect maze of paths. These trails

are wide enough under foot, but meet just over

one's shoulders, so that it is impossible to

maintain an upright position. The paths run

in all directions, and therefore one cannot see

far ahead. Were it not for the fact that here

and there—often 200 feet apart, however—are

small open patches, it would be almost

useless to enter such a fastness. These open

places lure one on, as from their edges it is

often possible to get a good shot. Once

started, we took up the path which showed

the most and freshest spoor, and, stooping low,

pressed on as swiftly and noiselessly as possible.

We had not gone far before we came upon

a small opening, from the center of which rose

an acacia not more than eight inches in thickness

of trunk and perhaps eighteen feet high.

It was forked at the height of a man's shoulder.

I carried the 8-bore, and was glad of an opportunity

to rest it in the convenient fork before

me. I had just done so, when crash! snort!

bellow! came several animals (presumably buffalo)

in our direction. One gun-bearer literally

flew up the tree against which I rested my rifle;

the other, regardless of consequences, hurled

his naked skin against another but smaller tree,

also thorny; both dropped their rifles. I stood

sheltered behind eight inches of acacia wood,

with my rifle pointed in front of me and still

resting in the fork of the tree. The noise of

the herd approached nearer and nearer, and my

nerves did not assume that steelly quality I had

imagined always resulted from a sudden danger.

Fly I could not, and the only tree climbable

was already occupied; so I stood still.

Just as I looked for the appearance of the

beasts in the little opening in which I stood, the

crashing noise separated in two portions—each

passing under cover on either side of the opening.

I could see nothing, but my ears were

filled with the noise. The uproar ceased, and

I asked the negro in the tree what had happened.

He said, when he first climbed the tree

he could see the bushes in our front move like

the waves of the sea, and then, Ham del illah—praise

be to God—the buffalo turned on either

side and left our little opening safe. Had they

not turned, but charged straight at us, I fancy

I should have had a disagreeable moment. As

it was, I began to understand why buffalo shooting

in the bush has been always considered unsafe,

and began to regret that the road back to

the open plain was not a shorter one. We

reached it in safety, however, and, after a short

rest, set out up wind.

I got a hartbeest and an mpallah before

noon, and then, satisfied with my day, returned

to camp. By 4 P. M. my men had brought in

all the meat, and soon the little camp was filled

with strips of fresh meat hanging on ropes of

twisted bark. The next day we exchanged the

meat for flour, beans, pumpkins and Indian

corn. I remained in this camp three more days

and then returned to Taveta. Each one of

these days I attempted to get a shot at buffalo,

but never managed it. On one occasion I

caught a glimpse of two of these animals in

the open, but they were too wary to allow me

to approach them.

When I reached Taveta, I found a capital

camp had been built during my absence, and

that a food supply had been laid in sufficient

for several weeks. Shortly after my arrival I

was startled by the reports of many rifles, and

soon was delighted to grasp the hands of two

compatriots—Dr. Abbott and Mr. Stevens.

They had just returned from a shooting journey

in Masai land, and reported game plenty

and natives not troublesome. My intention

was then formed to circumnavigate Mt. Kilimanjaro,

pass over the yet untried shooting

grounds and then to return to the coast.

I left five men in camp at Taveta in charge

of most of my goods, and, taking 118 men with

me, set out into Masai land. Even at this

late date (1895) the Masai are reckoned dangerous

customers. Up to 1889 but five European

caravans had entered their territory, and all

but the last—that of Dr. Abbott—had reported

difficulties with the natives. My head man, a

capital fellow, had had no experience with these

people, and did not look forward with pleasure

to making their acquaintance; but he received

orders to prepare for a start with apparent

cheerfulness. We carried with us one ton of

beans and dried bananas as food supply. This

was sufficient for a few weeks, but laid me

under the necessity of doing some successful

shooting, should I carry out my plan of campaign.

Just on the borders of Masai land live

the Useri people, who inhabit the northeast

slopes of Kilimanjaro. We stopped a day or

two with them to increase our food supply, and

while the trading was going on I descended to

the plain in search of sport.

I left camp at dawn and it was not till noon

that I saw game. Then I discovered three

rhinos; two together lying down, and one solitary,

nearly 500 yards away from the others.

The two lying down were nearest me, but were

apparently unapproachable, owing to absolute

lack of cover. The little plain they had chosen

for their nap was as flat as a billiard table and

quite bare of grass. The wind blew steadily

from them and whispered me to try my luck, so

I crawled cautiously toward them. When I got

to within 150 yards, one of the beasts rose and

sniffed anxiously about and then lay down again.

The rhinoceros is nearly blind when in the bright

sun—at night it can see like an owl. I kept on,

and when within 100 yards rose to my knees

and fired one barrel of my .577. The rhinos

leapt to their feet and charged straight at me.

"Shall I load the other barrel or trust to only

one?" This thought ran through my mind,

but the speed of the animals' approach gave

me no time to reply to it. My gun-bearer was

making excellent time across the plain toward

a group of trees, so I could make no use of the

8-bore. The beasts came on side by side, increasing

their speed and snorting like steam

engines as they ran. They were disagreeably

close when I fired my second barrel and rose

to my feet to bolt to one side. As I rose they

swerved to the left and passed not twenty feet

from me, apparently blind to my whereabouts.

I must have hit one with my second shot, for

they were too close to permit a miss. Perhaps

that shot turned them. Be that as it may, I

felt that I had had a narrow escape.

When these rhinos had quite disappeared,

my faithful gun-bearer returned, and smilingly

congratulated me on what he considered my

good fortune. He then called my attention to

the fact that rhinoceros number three was still

in sight, and apparently undisturbed by what

had happened to his friends. Between the

beast and me, stretched an open plain for some

350 yards, then came three or four small trees,

and then from these trees rose a semi-circular

hill or rather ridge, on the crest of which stood

the rhino. I made for the trees, and, distrusting

my gun-bearer, took from him the .577 and

placed it near one of them. Then, telling him

to retire to a comfortable spot, I advanced with

my 8-bore up the hill toward my game. The

soil was soft as powder, so my footsteps made

no noise. Cover, with the exception of a small

skeleton bush, but fifty yards below the rhino,

there was none. I reached the bush and knelt

down behind it. The rhino was standing broadside

on, motionless and apparently asleep. I

rose and fired, and saw that I had aimed true,

when the animal wheeled round and round in

his track. I fired again, and he then stood still,

facing me. I had one cartridge in my pocket

and slipped it in the gun. As I raised the

weapon to my shoulder, down the hill came my

enemy. His pace was slow and I could see

that he limped. The impetus given him by

the descent kept him going, and his speed

seemed to increase. I fired straight at him and

then dropped behind the bush. He still came

on and in my direction; so I leapt to my feet,

and, losing my head, ran straight away in front

of him. I should have run to one side and

then up the hill. What was my horror, when

pounding away at a good gait, not more than

fifty feet in front of the snorting rhino, to find

myself hurled to the ground, having twisted

my ankle. I thought all was over, when I had

the instinct to roll to one side and then scramble

to my feet. The beast passed on. When

he reached the bottom of the hill his pace

slackened to a walk, and I returned to where I

had left my .577 and killed him at my leisure.

I found the 8-bore bullet had shattered his off

hind leg, and that my second shot had penetrated

his lungs. I had left the few men I had

brought with me on a neighboring hill when I

had first caught sight of the rhinos, and now

sent for them. Not liking to waste the meat,

I sent to camp for twenty porters to carry it

back. I reached camp that night at 12:30 A. M.,

feeling quite worn out.

After a day's rest we marched to Tok-i-Tok,

the frontier of Masai land. This place is at

certain seasons of the year the pasture ground

of one of the worst bands of Masai. I found

it nearly deserted. The Masai I met said their

brethren were all gone on a war raid, and that

this was the only reason why I was permitted

to enter the country. I told them that I had

come for the purpose of sport, and hoped to

kill much game in their country. This, however,

did not appear to interest them, as the

Masai never eat the flesh of game. Nor do

they hunt any, with the exception of buffalo,

whose hide they use for shields. I told them

I was their friend and hoped for peace; but,

on the other hand, was prepared for war

should they attack me.

From Tok-i-Tok we marched in a leisurely

manner to a place whose name means in English

"guinea fowl camp." In this case it was

a misnomer, for we were not so fortunate as

to see one of these birds during our stay of

several days. At this place we were visited by

some fifty Masai warriors, who on the receipt

of a small present danced and went away. The

water at guinea fowl camp consisted of a spring

which rises from the sandy soil and flows a few

hundred yards, and then disappears into the

earth. This is the only drinking-place for several

miles, so it is frequented by large numbers

and many varieties of game. At one time

I have seen hartbeest, wildbeest, grantii, mpallah,

Thomson's oryx, giraffes and rhinoceros.

We supported the caravan on meat. I used

only the .450 Express; but my servant, George

Galvin, who used the Winchester, did better

execution with his weapon than I with mine.

Here, for the first and last time in my African

experiences, we had a drive. Our camp

was pitched on a low escarpment, at the bottom

of which, and some 300 feet away, lay the

water. The escarpment ran east and west, and

extended beyond the camp some 500 yards,

where it ended abruptly in a cliff forty or fifty

feet high. Some of my men, who were at the

end of the escarpment gathering wood, came

running into camp and said that great numbers

of game were coming toward the water.

I took my servant and we ran to the end of

the escarpment, where a sight thrilling indeed

to the sportsman met our eyes. First came

two or three hundred wildbeest in a solid

mass; then four or five smaller herds, numbering

perhaps forty each, of hartbeest; then

two herds, one of mpallah and one of grantii.

There must have been 500 head in the lot.

They were approaching in a slow, hesitating

manner, as these antelope always do approach

water, especially when going down wind.

Our cover was perfect and the wind blowing

steadily in our direction. I decided, knowing

that they were making for the water, and to

reach it must pass close under where we lay

concealed, to allow a certain number of them to

pass before we opened fire. This plan worked

perfectly. The animals in front slackened

pace when they came to within fifty yards of

us, and those behind pressed on and mingled

with those in front. The effect to the eye was

charming. The bright tan-colored skins of the

hartbeest shone out in pleasing contrast to the

dark gray wildbeest. Had I not been so

young, and filled with youth's thirst for blood,

I should have been a harmless spectator of this

beautiful procession. But this was not to be.

On catching sight of the water, the animals

quickened their pace, and in a moment nearly

half of the mass had passed our hiding-place.

A silent signal, and the .450 and the Winchester,

fired in quick succession, changed this

peaceful scene into one of consternation and

slaughter. Startled out of their senses, the

beasts at first halted in their tracks, and then

wheeling, as if at word of command, they

dashed rapidly up wind—those in the rear receiving

a second volley as they galloped by.

When the dust cleared away, we saw lying

on the ground below us four animals—two

hartbeest and two wildbeest. I am afraid that

many of those who escaped carried away with

them proofs of their temerity and our bad

marksmanship.

Ngiri, our next camp, is a large swamp, surrounded

first by masses of tall cane and then

by a beautiful though narrow strip of forest

composed of tall acacias. It was at this place,

in the thick bush which stretches from the

swamp almost to the base of Kilimanjaro, that

the Hon. Guy Dawnay, an English sportsman,

had met his death by the horns of a buffalo

but four months before. My tent was pitched

within twenty paces of his grave and just under

a large acacia, which serves as his monument,

upon whose bark is cut in deep characters

the name of the victim and the date of his

mishap.

Here we made a strong zariba of thorns, as

we had heard we should meet a large force of

Masai in this neighborhood. I stopped ten

days at Ngiri, and, with the exception of one

adventure hardly worth relating, had no difficulty

with the Masai. Undoubtedly I was

very fortunate in finding the large majority of

the Masai warriors, inhabiting the country

through which I passed, absent from their

homes. But at the same time I venture to

think that the ferocity of these people has been

much overrated, especially in regard to Europeans;

for the force at my disposal was not

numerous enough to overawe them had they

been evilly disposed.

One morning, after I had been some days at

Ngiri, I set out with twenty men to procure

meat for the camp. The sun had not yet risen,

and I was pursuing my way close to the belt of

reeds which surrounds the swamp, when I saw

in the dim light a black object standing close

to the reeds. My men said it was a hippo, but

as I drew nearer I could distinguish the outlines

of a gigantic buffalo, broadside on and

facing from the swamp. When I got to within

what I afterwards found by pacing it off to

be 103 paces, I raised my .577 to my shoulder,

and, taking careful aim at the brute's shoulder,

fired. When the smoke cleared away there

was nothing in sight. Knowing the danger of

approaching these animals when wounded, I

waited until the sun rose, and then cautiously

approached the spot. The early rays of the

sun witnessed the last breathings of one of the

biggest buffaloes ever shot in Africa. Its head

is now in the Smithsonian Institute at Washington,

and, according to the measurement

made by Mr. Rowland Ward, Piccadilly, London,

it ranks among the first five heads ever

set up by him.

After sending the head, skin and meat back

to camp, I continued my way along the shore

of the swamp. The day had begun well and

I hardly hoped for any further sport, but I was

pleasantly disappointed.

Toward 11 o'clock I entered a tall acacia

forest, and had not proceeded far in it before

my steps were arrested by the sight of three

elephants, lying down not 100 yards from me.

They got our wind at once, and were up and

off before I could get a shot. I left all my men

but one gun-bearer on the outskirts of the forest

and followed upon the trail of the elephant.

I had not gone fifteen minutes before I had

traversed the forest, and entered the thick and

almost impenetrable bush beyond it. And

hardly had I forced my way a few paces into

this bush, when a sight met my eyes which

made me stop and think. Sixty yards away,

his head towering above the surrounding bush,

stood a monstrous tusker. His trunk was

curled over his back in the act of sprinkling

dust over his shoulders. His tusks gleamed

white and beautiful. He lowered his head,

and I could but just see the outline of his

skull and the tips of his ears. This time my

gun-bearer did not run. The sight of the ivory

stirred in him a feeling, which, in a Swahili,

often conquers fear—cupidity. I raised some

dust in my hand and threw it in the air, to see

which way the wind blew. It was favorable.

Then beckoning my gun-bearer, I moved forward

at a slight angle, so as to come opposite

the brute's shoulder. I had gone but a few

steps when the bush opened and I got a good

sight of his head and shoulder. He was apparently

unconscious of our presence and was

lazily flapping his ears against his sides. Each

time he did this, a cloud of dust arose, and a

sound like the tap of a bass drum broke the

stillness. I fired my .577 at the outer edge of

his ear while it was lying for an instant against

his side. A crash of bush, then silence, and no

elephant in sight. I began to think that I had

been successful, but the sharper senses of the

negro enabled him to know the contrary. His

teeth chattered, and for a moment he was motionless

with terror. Then he pointed silently

to his left. I stooped and looked under the

bush. Not twenty feet away was a sight which

made me share the feelings of my gun-bearer.

The elephant was the picture of rage; his forelegs

stretched out in front of him, his trunk

curled high in the air, and his ears lying back

along his neck. I seized my 8-bore and took

aim at his foreward knee, but before I could

fire, he was at us. I jumped to one side and

gave him a two-ounce ball in the shoulder,

which apparently decided him on retreat. The

bush was so thick that in a moment he was out

of sight. I followed him for some time, but

saw no more of him. His trail mingled with

that of a large herd, which, after remaining together

for some time, apparently separated in

several directions. The day was blazing hot,

and I was in the midst of a pathless bush, far

away from my twenty men.

By 2 P. M., I had come up with them again

and turned my face toward camp. On the way

thither, I killed two zebras, a waterbuck and a

Thomsonii. By the time the meat was cut up

and packed on my men's heads the sun had set.

The moon was magnificently bright and served

to light our road. For one mile our way led

across a perfectly level plain. This plain was

covered with a kind of salt as white as snow,

and with the bright moon every object was

as easily distinguished as by day. The fresh

meat proved an awkward load for my men, and

we frequently were forced to stop while one

or the other re-arranged the mass he carried.

They were very cheery about it, however, and

kept shouting to one another how much they

would enjoy the morrow's feast. Their shouts

were answered by the mocking wails of many

hyenas, who hovered on our flanks and rear

like a pursuing enemy. I shot two of these

beasts, which kept their friends busy for a while,

and enabled us to pursue our way in peace.

This white plain reaches nearly to the shores

of Ngiri Swamp on the north, and to the

east it is bounded by a wall of densely thick

bush. We had approached to within 400

yards of the point where the line of bush joins

the swamp, when I noticed a small herd of

wildbeest walking slowly toward us, coming

from the edge of the swamp. A few moments

later, a cry escaped from my gun-bearer, who

grasped my arm and whispered eagerly, simba.

This means lion. He pointed to the wall of

bush, and near it, crawling on its belly toward

the wildbeest, was the form of a lion. I

knelt down and raised the night sight of my

.450, and fired at the moving form. The white

soil and the bright moon actually enabled me

to distinguish the yellow color of its skin. A

loud growl answered the report of my rifle, and

I could see the white salt of the plain fly as

the lion ran round and round in a circle, like a

kitten after its tail. I fired my second barrel

and the lion disappeared. The wildbeest had

made off at the first shot. I tried, in the

eagerness of youth, to follow the lion in the

bush; but soon common sense came to my

rescue, and warned me that in this dark growth

the chances were decidedly in favor of the

lion's getting me, and so gave up the chase.

Now, if I had only waited till the great cat

had got one of the wildbeest, I feel pretty

sure I should have been able to dispose of it

at my leisure. When I returned to camp, I

ungratefully lost sight of the good luck I had

had, and gnashed my teeth at the thought

that I had missed bringing home a lion and

an elephant. I was not destined to see a lion

again on this journey, but my annoyance at

my ill fortune was often whetted by hearing

them roar.

However, by good luck and by George's

help, I succeeded in securing one elephant.

The story of how this happened shall be the

last hunting adventure recorded in this article.

We had left Ngiri and were camped at the

next water, some ten miles to the west. I had

been out after giraffes and had not been unsuccessful,

and therefore had reached camp in

high good humor, when George came to me

and said things were going badly in camp—that

the men had decided to desert me should

I try to push further on into the country; and

that both head men seemed to think further

progress was useless with the men in such

temper. I was puzzled what to do, but wasted

no time about making up my mind to do something.

I went into the tent and called the

two head men to me. After a little delay, they

came, greeted me solemnly and at a motion

from me crouched on their hams. There is

but little use in allowing a negro to state a

grievance, particularly if you know it is an

imaginary one. The mere act of putting their

fancied wrongs into words magnifies them in

their own minds, and renders them less likely

to listen to reason. My knowledge of Swahili

at this time did not permit me to address them

in their own language, so I spoke to them in

English, knowing that they understood at least

a few words of that tongue. I told them that

I was determined to push on; that I knew

that porters were like sheep and were perfectly

under the control of the head men; consequently,

should anything happen, I would

know on whom to fix the blame. I repeated

this several times, and emphasized it with

dreadful threats, then motioned for them to

leave the tent. I cannot say that I passed a

comfortable night. Instead of songs and

laughter, an ominous stillness reigned in the

camp, and, though my words had been brave,

I knew that I was entirely at the mercy of

the men.

Before dawn we were under way, keeping a

strict watch for any signs of mutiny. But,

though the men were sullen, they showed no

signs of turning back. Our road lay over a

wide plain, everywhere covered thickly with

lava, the aspect of which was arid in the

extreme.

No more green buffalo bush, no more acacias,

tall and beautiful, but in their place rose

columns of dust, whirled hither and thither by

the vagrant wind. Two of my men had been

over this part of the road before, but they professed

to be ignorant of the whereabouts of

the next water place. Any hesitation on my

part would have been the signal for a general

retreat, so there was nothing for it but to assume

a look of the utmost indifference, and to

assure them calmly that we should find water.

At noon the appearance of the country had

not changed. My men, who had incautiously

neglected to fill their water bottles in the

morning, were beginning to show signs of

distress.

Suddenly my gun-bearer, pointing to the

left, showed me two herds of elephants approaching

us. The larger herd, composed

principally of bulls, was nearer to us, and

probably got our wind; for they at once

turned sharply to their right and increased

their pace. The other herd moved on undisturbed.

I halted the caravan, told the men

to sit down and went forward to meet the elephants,

with my servant and two gun-bearers.

I carried a .577, my servant carried the old

12-bore by Lang, his cartridges crammed to

the muzzle with powder. We were careful

to avoid giving the elephants our wind, so we

advanced parallel to them, but in a direction

opposite to that in which they were going. As

they passed us we crouched, and they seemed

unconscious of our presence. They went about

400 yards past us, and then halted at right

angles to the route they had been pursuing.

There were five elephants in this herd—four

large, and one small one, bringing up the rear.

Some 60 yards on their right flank was a small

skeleton bush, and, making a slight detour, we

directed our course toward that. The leading

animal was the largest, so I decided to devote

our attention to that one. I told George to

fire at the leg and I would try for the heart.

We fired simultaneously, George missing and

my shot taking effect altogether too high.

Two things resulted from the discharge of

our rifles: the gun-bearers bolted with their

weapons and the elephants charged toward us

in line of battle. As far as I can calculate, an

elephant at full speed moves 100 yards in

about ten seconds, so my readers can judge

how much time elapsed before the elephants

were upon us. We fired again. My shot did

no execution, but George, who had remained

in a kneeling position, broke the off foreleg of

the leading animal at the knee. It fell, and

the others at once stopped. We then made

off, and watched from a little distance a most

interesting sight.

The condition of the wounded elephant

seemed to be known to the others, for they

crowded about her and apparently offered her

assistance. She placed her trunk on the back

of one standing in front of her and raised herself

to her feet, assisted by those standing

around. They actually moved her for some

distance, but soon got tired of their kindly

efforts. We fired several shots at them, which

only had the effect of making two of the band

charge in our direction and then return to

their stricken comrade. Cover there was none,

and with our bad marksmanship it would have

been (to say the least) brutal to blaze away

at the gallant little herd. Besides, cries of

"water!" "water!" were heard coming from my

thirsty caravan. So there was nothing for it

but to leave the elephant, take the people to

water, if we could find it, and then return and

put the wounded animal out of its misery.

An hour and a half later we reached water,

beautiful and clear, welling up from the side

of a small hill. This is called Masimani. On

reaching the water, all signs of discontent

among my people vanished, and those among

them who were not Mahomedans, and therefore

had no scruples about eating elephant

meat, raised a cheerful cry of tembo tamu—elephant

is sweet. I did not need a second

hint, but returned, and, finding the poor elephant

deserted by its companions, put it out of

its misery. It was a cow with a fine pair of

tusks. The sun was setting, and my men,

knowing that activity was the only means of

saving their beloved elephant meat from

hyenas, attacked the body with fury—some

with axes, others with knives and one or two

with sword bayonets. It was a terrible sight,

and I was glad to leave them at it and return

to camp, well satisfied with my day's work.

From Masimani, for the next four days, the

road had never been trodden by even an Arab

caravan. I had no idea of the whereabouts

of water, nor had my men; but, having made a

success of the first day's march, the men followed

me cheerfully, believing me possessed

of magic power and certain to lead them over

a well-watered path. A kind providence did

actually bring us to water each night. The

country was so dry that it was absolutely

deserted by the inhabitants, the Masai, and

great was the surprise of the Kibonoto people

when we reached there on the fourth day.

They thought that we had dropped from the

clouds, and said there could not have been

any water over the road we had just come.

These Kibonoto people had never been visited

by an European, but received us kindly. The

people of Kibonoto are the westernmost inhabitants

on the slopes of Kilimanjaro.

From there to Taveta our road was an easy

one, lying through friendly peoples. After a

brief rest at Taveta, I returned to the coast,

reaching Zanzibar a little over six months

after I had set out from it.

Perhaps a word about the climate of the

part of the country through which I passed

will not be amiss. Both my servant and myself

suffered from fever, but not to any serious

extent. If a sedentary life is avoided—and

this is an easy matter while on a journey—if

one avoids morning dews and evening damps,

and protects his head and the back of his neck

from the sun, I do not think the climate of

East Africa would be hurtful to any ordinarily

healthy person. For my part, I do not think

either my servant or myself have suffered any

permanent ill effects from our venture; and

yet the ages of twenty-one and seventeen are

not those best suited for travels in the tropics.

W. A. Chanler.

A MOUNTAIN SHEEP.

To the Gulf of Cortez

About a year ago, my brother, who is a

very sagacious physician, advised me to take

the fresh liver of a mountain sheep for certain

nervous symptoms which were troublesome.

None of the local druggists could fill the prescription,

and so it was decided that I should

seek the materials in person. With me went

my friend J. B., the pearl of companions, and

we began the campaign by outfitting at San

Diego, with a view to exploring the resources

of the sister republic in the peninsula of

Lower California. Lower California is very

different from Southern California. The latter

is—well, a paradise, or something of that

kind, if you believe the inhabitants, of whom

I am an humble fraction. The former is what

you may please to think.

At San Diego we got a man, a wagon, four

mules and the needed provisions and kitchen—all

hired at reasonable rates, except the

provisions and kitchen, which we bought.

Then we tried to get a decent map, but

were foiled. The Mexican explorer will find

the maps of that country a source of curious

interest. Many of them are large and elaborately

mounted on cloth, spreading to a great

distance when unfolded. The political divisions

are marked with a tropical profusion of

bright colors, which is very fit. A similar

sense of fitness and beauty leads the designer

to insert mountain ranges, rivers and towns

where they best please the eye, and I have

had occasion to consult a map which showed

purely ideal rivers flowing across a region

where nature had put the divide of the highest

range in the State.

My furniture contained a hundred cartridges,

a belt I always carry, given by a friend, with a

bear's head on the buckle (a belt which has

held, before I got it, more fatal bullets than

any other west of the Rockies), and my usual

rifle. J. B. prepared himself in a similar way,

except the belt.

Starting south from San Diego, we crossed

the line at Tia Juana, and spent an unhappy

day waiting on the custom house officials.

They, however, did their duty in a courteous

manner, and we, with a bundle of stamped

papers, went on. The only duties we paid

were those levied on our provisions. The

team and wagon were entered free under a

prospector's license for thirty days, and an

obliging stableman signed the necessary bond.

The main difficulty in traveling in Lower

California lies in the fact that you can get

no feed for your animals. From Tia Juana

east to Tecate, where you find half a dozen

hovels, there is hardly a house and not a

spear of grass for thirty miles. At Tecate

there is a little nibbling. Thence south for

twenty-five miles we went to the Agua Hechicera,

or witching water; thence east twenty-five

miles more to Juarez, always without

grass; thence south to the ranch house of the

Hansen ranch, at El Rayo, twenty-five miles

more. There, at last, was a little grass, but

after passing that point we camped at Agua

Blanca, and were again without grass for

thirty miles to the Trinidad Valley, which

once had a little grass, now eaten clean.

Fortunately we were able to buy hay at

Tia Juana, and took some grain. Fortunately,

also, we found some corn for sale at

Juarez. So, with constant graining, a little

hay and a supply of grass, either absent or

contemptible, we managed to pull the stock

through.

Besides our four hired mules there was another,

belonging to our man, Oscar, which we

towed behind to pack later. The animal was

small in size, but pulled back from 200 pounds

to a ton at every step. Its sex was female, but

its name was Lazarus, for the overwhelming

necessity of naming animals of the ass tribe

either Lazarus or Balaam tramples on all distinctions

of mere sex. We started, prepared

for a possible, though improbable, season of

rain; but we did not count on extreme cold,

yet the first night out the water in our bucket

froze, and almost every night it froze from a

mere skin to several inches thick. To give an

idea of the country, I will transcribe from a

brief diary a few descriptions. Starting from

Tia Juana, we drove or packed for nearly 200

miles in a southeasterly direction, until we

finally sighted the Gulf and the mountains of

Sonora in the distance. At first our road lay

through low mountains, in valleys abounding

in cholla cactus. From Tecate southward,

the country was rolling and clotted with

brushwood, until you reach Juarez. Juarez

is an abandoned, or almost abandoned, placer

camp. Here, amid the countless pits of the

miners, the piñons begin, and then, after a

short distance, the pine barrens stretch for

forty miles. Beyond again you pass into hills

of low brush, and plains covered with sage and

buckweed, until finally you cross a divide into

the broad basin of the Trinidad Valley. This

is a depression some twenty miles long and

perhaps five miles wide on the average, with a

hot spring and a house at the southwestern

end, walled on the southeast by the grim

frowning rampart of the San Pedro Martir

range, and on the other sides by mountains of

lesser height, but equal desolation.

We had intended at first to strike for the

Cocopah range, near the mouth of the Colorado

River, and there do our hunting. Several

reasons induced us to change our plan and

make for the Hansen ranch, where deer were

said to be plenty and sheep not distant; so we

turned from Tecate southward, made one dry

camp and one camp near Juarez, and on the

fifth day of our journeying reached a long

meadow, called the Bajio Largo, on the Hansen

ranch. We turned from the road and followed

the narrow park-like opening for four

miles, camping in high pines, with water near,

and enough remnants of grass to amuse the

animals. This region of pine barrens occurs

at quite an elevation, and the nights were

cold. The granite core of the country crops

out all along in low broken hills, the intervening

mesas consisting of granite sand and

gravel, and bearing beside the pines a good

deal of brush. Thickets of manzanita twisted

their blood-colored trunks over the ground,

and the tawny stems of the red-shank covered

the country for miles. The red-shank is a lovely

shrub, growing about six or eight feet high,

with broom-like foliage of a yellowish green,

possessing great fragrance. If you simply

smell the uncrushed shoots, they give a faint

perfume, somewhat suggestive of violets; and

if you crush the leaves you get a more pungent

odor, sweet and a little smoky. Also,

the gnarled roots of the red-shank make an

excellent cooking fire, if you can wait a few

hours to have them burn to coals. All things

considered, the pine barren country is very

attractive, and if there were grass, water and

game, it would be a fine place for a hunter.

From our camp at Bajio Largo, J. B. and I

went hunting for deer, which were said to be

plentiful. We hunted from early morning till

noon, seeing only one little fellow, about the

size of a jack rabbit, scuttle off in the brush.

Then we decided to go home. This, however,

turned out to be a large business. The lofty

trees prevented our getting any extended

view, and the stony gulches resembled each

other to an annoying degree. At last even

the water seemed to flow the wrong way. So

we gave up the attempt to identify landmarks,

and, following our sense of direction and taking

our course from the sun, we finally came again

to the long meadow, and, traveling down that,

we came to camp. Here we violated all rules

by shooting at a mark—our excuse was that

we had decided to leave the vicinity without

further hunting; and, at all events, we spoiled

a sardine box, to Oscar's great admiration.

In order to get a fair day's journey out of a

fair day, we had to rise at 4 or 5 o'clock.

Oscar once or twice borrowed my watch to

wake by, but the result was only that I had to

borrow J. B.'s watch to wake Oscar by; so I

afterwards retained the timepiece, and got up

early enough to start Oscar well on his duties.

The question of fresh meat had now become

important. We left Bajio Largo and drove to

Hansen's Laguna, a shallow pond over a mile

long, much haunted by ducks. Here we made

a bad mistake, driving six or eight miles into

the mountains, only to reach nowhere and be

forced to retrace our steps. Night, however,

found us at El Rayo, the Hansen ranch house,

and, as it turned out, the real base of our

hunting campaign. The Hansen ranch is an

extensive tract, named after an old Swede, who

brought a few cattle into the country years

ago. The cattle multiplied exceedingly, to the

number, indeed, of several thousand, and can

be seen at long range by the passer-by. They

are very wild and gaunt at present, and will

prance off among the rocks at a surprising

rate before a man can get within 200 yards of

them. Ex-Governor Ryerson now owns these

cattle, and his major-domo, Don Manuel Murillo,

a fine gray-haired veteran, learning that I

had known the Governor, gave me much

friendly advice, and sent his son to guide us

well on the road to the Trinidad Valley and

the sheep land. He also provided us with

potatoes and fresh meat, so that we lived

fatly thenceforth.

Our track lay past an abandoned saw-mill,

built by the International Company. Thence

we were to go to Agua Blanca, the last water

to be had on the road; for the next thirty

miles are dry. The saw-mill was built to

supply timber to the mining town of Alamo,

some twenty-five miles south. The camp is

now in an expiring state and needs no timber,

but is said to shelter some rough and violent

men. The road from the mill was deep

in sand, and our pace was slow. The darkness

was coming cold and fast when we finally

drove on to the water and halted to camp.

Two men were there before us, with a saddle-horse

each, and no other apparent equipment.

When we arrived, the men were watering

their animals, and at once turned their

backs, so as not to be recognized. Then they

retired to the brush. We supped and staked

out the mules, and then sent Oscar to look up

our neighbors. Oscar went and shouted, but

got no answer, and could find no men. We

thought that our mules were in some danger,

and J. B., who is a yachtsman, proposed to

keep anchor watch. So Oscar remained awake

till midnight, when he awoke me and retired

freezing, saying that he had seen the enemy

prowling around. I took my gun and visited

the mules in rotation till 2:30. Then J. B.

awoke, chattering with cold, but determined,

and kept faithful guard until 5, when we began

our day with a water-bucket frozen solid.

All our property remained safe, and a distant

fire twinkling in the brush showed that

our neighbors were still there. After breakfast

Oscar again sought the hostile camp, and

finally found a scared and innocent Frenchman,

who cried out, on recognizing his visitor:

"Holy Mary! I took you for American

robbers from the line, and I have lain awake

all night, watching my horses."

From Agua Blanca we drove across the

Santa Catarina ranch, for the most part plain

and mesa, covered with greasewood and buckbrush.

This latter shrub looks much like sage,

except that its leaves are of a yellow-green

instead of a blue-green. It is said to furnish

the chief nutrition for stock on several great

ranches. Certainly there was no visible grass,

but buckbrush can hardly be fattening. Toward

night, we crossed the pass into the Trinidad

Valley and drove down a grade not steep

only, but sidelong, where the wagons both

went tobogganing down and slid rapidly toward

the gulch. The mules held well, however,

and before dark we were camped near

the hot spring at the house of Alvarez.

Our friend, Don Manuel Murillo, had recommended