The Project Gutenberg eBook of Butterflies Worth Knowing

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Butterflies Worth Knowing

Author: Clarence Moores Weed

Release date: August 8, 2011 [eBook #37009]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BUTTERFLIES WORTH KNOWING ***

[Pg ii]

[Pg iii]

Nature Biographies,

Ten New England Blossoms,

The Flower Beautiful,

etc.

Thirty-two in Color

[Pg iv]

Copyright, 1917, by

All rights reserved, including that of

translation into foreign languages,

including the Scandinavian

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

[Pg v]

PREFACE

In this little book an attempt has been made to discuss

the more abundant and widely distributed butterflies of

eastern North America from the point of view of their

life histories and their relations to their surroundings. In

so doing I have of course availed myself of the written

records of a host of students of butterflies, without whose

labors no such volume would be possible. Among these

two names stand out preëminent—William H. Edwards

and Samuel H. Scudder. Each was the author of a

sumptuous work on American butterflies to which all later

students must refer, both for information and for inspiration.

Many others, however, have made notable contributions

to our literature of these ethereal creatures. Every

seeker after a knowledge of butterflies will soon find

himself indebted to the writings of such investigators

as the Comstocks, Denton, Dickerson, Dyar, Fernald,

Fiske, Fletcher, French, Hancock, Holland, Howard,

Longstaff, Newcomb, Riley, Skinner, Wright, and many

others. I am glad to express my obligations to all of these

for the assistance their records have given in the preparation

of this book.

While a vast amount of knowledge of butterflies has

already been discovered there is still more to be learned

concerning them, and throughout these pages I have

attempted to indicate the more important opportunities

[Pg vi]

awaiting investigation. The day of the field naturalist has

come again and the butterflies are well worthy of careful

observations by many interested students.

The illustrations in the book require a word of credit.

The eleven color plates of adult butterflies with wings

spread have been made direct from a set of the remarkable

transfers which Mr. Sherman F. Denton has been preparing

for the last quarter-century, this particular set

having been prepared especially for this book. Transfers

of this sort were used as insets in Mr. Denton's work on

the "Moths and Butterflies of the United States," published

in a limited edition by J. B. Millet Company,

Boston. The other plates not reproduced from photographs

are from drawings by Miss Mary E. Walker or

Mr. W. I. Beecroft. In case the photographs are not of

my own taking, credit is given beneath each. Two of my

photographs have already appeared in "Seeing Nature

First" and are here used by permission of its publishers,

J. B. Lippincott Company.

State Normal School

Lowell, Mass.

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | |

| Preface | v |

| List of Colored Illustrations | xi |

| List of Other Illustrations | xiii |

| PART I | |

| INTRODUCTION | |

| Butterfly Transformations | 5 |

| Butterflies and Moths | 13 |

| The Scents of Butterflies | 15 |

| Butterfly Migrations | 16 |

| Hibernation or Winter Lethargy | 17 |

| Aestivation or Summer Lethargy | 21 |

| Feigning Death in Butterflies | 22 |

| Coloration of Butterflies | 24 |

| Selective Color Sense in Butterflies | 32 |

| Warning Coloration and Mimicry | 33 |

| Heliotropism | 35 |

| List and Shadow Observations | 37 |

| Parasitic Enemies | 40 |

| Rearing Butterflies from Caterpillars | 43 |

| Photographing Butterflies | 47 |

| Butterfly Collections | 49 |

| PART II [Pg viii] | |

| PAGE | |

| True Butterflies—Superfamily Papilionoidea | 55 |

| Parnassians (Parnassiinae) | 56 |

| The Swallowtails (Papilionidae) Black Swallowtail; Giant Swallowtail; Blue Swallowtail; Green-clouded Swallowtail; Tiger Swallowtail; Palamedes Swallowtail; Short-tailed Papilio; Zebra Swallowtail; Synopsis of the Swallowtails | 57 |

| Whites, Orange-tips, and Yellows (Pieridae) | 82 |

The Tribe of the Whites: White or Imported Cabbage Butterfly; Gray-veined White; Checkered White; Great Southern White; Synopsis of the Whites | 83 |

The Tribe of the Orange-tips: Falcate Orange-tip; Olympian Orange-tip; Synopsis of the Orange-tips | 92 |

The Tribe of the Yellows: Brimstone or Cloudless Sulphur; Dog's-head; Clouded Sulphur; Orange Sulphur; Pink-edged Sulphur; Black-bordered Yellow; Little Sulphur; Dainty Sulphur; Synopsis of the Yellows | 97 |

| Nymphs (Nymphalidae) | 111 |

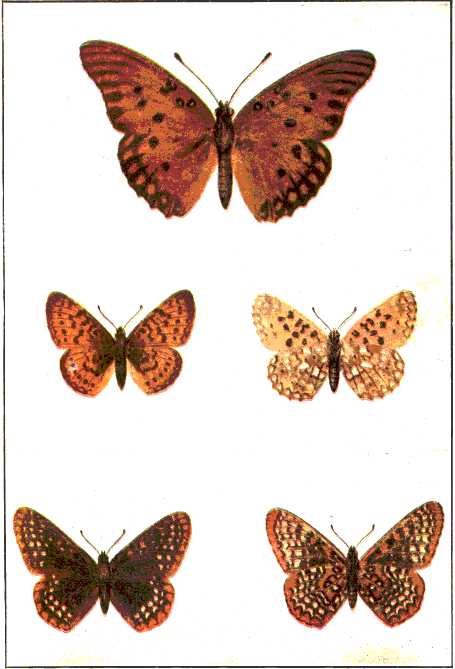

The Tribe of the [Pg ix]Fritillaries: Gulf Fritillary; Variegated Fritillary; Diana Fritillary; Regal Fritillary; Great Spangled Fritillary; Silver-spot Fritillary; Mountain Silver-spot; White Mountain Fritillary; Meadow Fritillary; Silver-bordered Fritillary; Synopsis of the Fritillaries | 115 |

The Tribe of the Crescent-spots: Baltimore Checker-spot; Harris's Checker-spot; Silver Crescent; Pearl Crescent; Synopsis of the Crescent-spots | 135 |

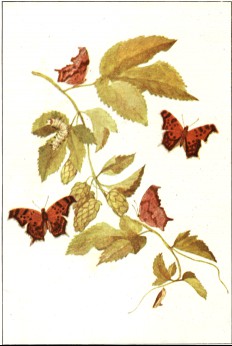

The Tribe of the Angle-wings: Violet-tip; Hop-merchant or Comma; Gray Comma; Green Comma; Red Admiral or Nettle Butterfly; Painted Beauty; Painted Lady or Cosmopolite; Mourning-cloak; American tortoise-shell; White J Butterfly or Compton Tortoise; Buckeye; Synopsis of the Angle-wings (I. Polygonias—II. Vanessids) | 150 |

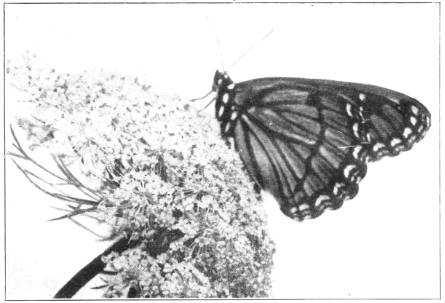

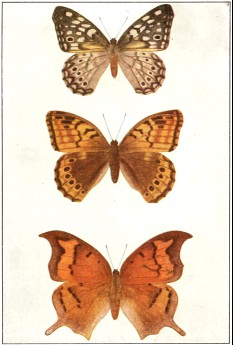

The Tribe of the Sovereigns: Viceroy; Banded Purple; Red-spotted Purple; Vicereine; Synopsis of the Sovereigns | 192 |

The Tribe of the Emperors: Goatweed Emperor; Gray Emperor; Tawny Emperor; Synopsis of the Emperors | 207 |

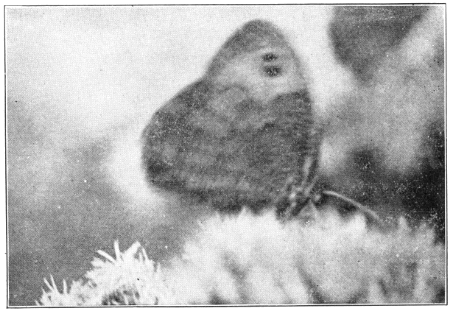

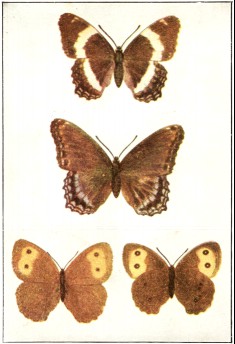

| Meadows-browns or Satyrs (Agapetidae) Common Wood Nymph or Grayling; Southern Wood Nymph; Pearly Eye; Eyed Brown; White Mountain Butterfly; Arctic Satyr; Little Wood Satyr; Other Meadow-browns; Synopsis of Meadow-browns | 214 |

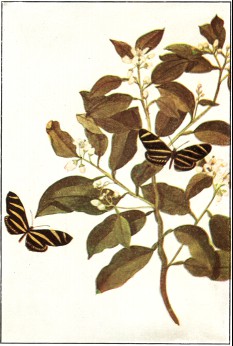

| Heliconians (Heliconidae) Zebra Butterfly | 229 |

| Milkweed Butterflies (Lymnadidae) Monarch; Queen | 232 |

| Snout Butterflies or Long-beaks (Libytheidae) Snout Butterfly | 236 |

| Metal-marks (Riodinidae) Small Metal-mark; Large Metal-mark | 239 |

| [Pg x] Gossamer-wings (Lycaenidae) | 240 |

The Tribe of the Hair-streaks: Great Purple Hair-streak; Gray Hair-streak; Banded Hair-streak; Striped Hair-streak; Acadian Hair-streak; Olive Hair-streak; Synopsis of the Hair-streaks | 242 |

The Tribe of the Coppers: Wanderer; American Copper; Synopsis of the Coppers | 252 |

The Tribe of the Blues: Spring Azure; Scudder's Blue; Tailed Blue; Silvery Blue: Synopsis of the Blues | 258 |

| PART III | |

| PAGE | |

| The Skipper Butterflies—Superfamily Hesperioidea | 266 |

| Giant Skippers (Megathymidae) Yucca-borer Skipper | 267 |

| Common Skippers (Hesperiidae) | 268 |

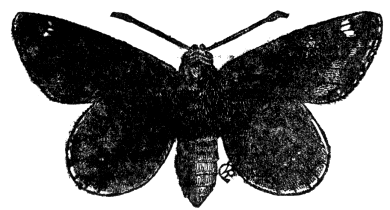

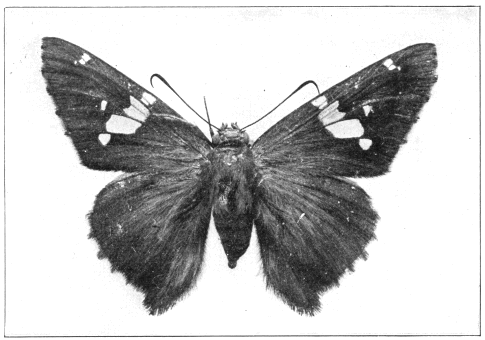

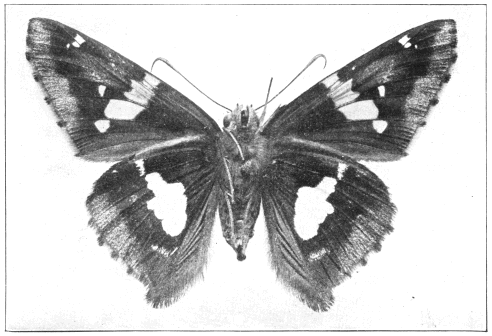

The Tribe of the Larger Skippers: Silver-spotted Skipper; Long-tailed Skipper; Juvenal's Dusky-wing; Sleepy Dusky-wing; Persius's Dusky-wing; Sooty Wing | 269 |

The Tribe of the Smaller Skippers: Tawny-edged Skipper; Roadside Skipper; Least Skipper | 278 |

[Pg xi]

LIST OF COLORED ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Viceroy Butterflies Visiting Strawberries | (On Cover) |

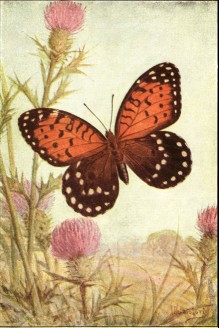

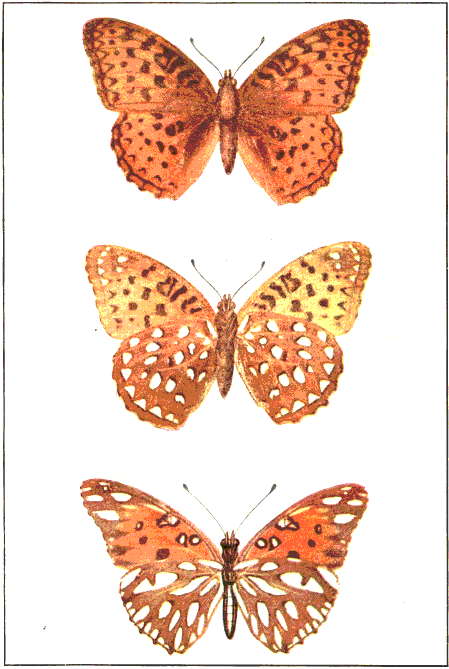

| The Regal Fritillary | Frontispiece |

| The Carolina Locust | 33 |

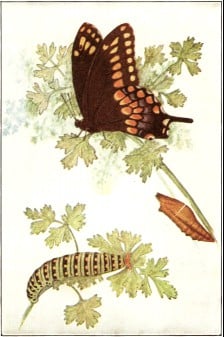

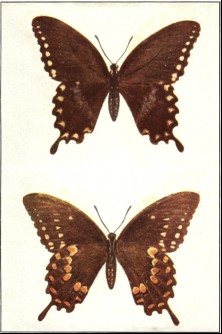

| The Black Swallowtail | 48 |

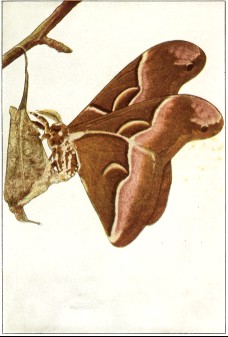

| The Cynthia Moth | 49 |

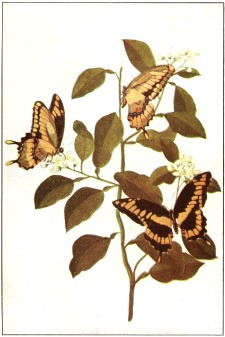

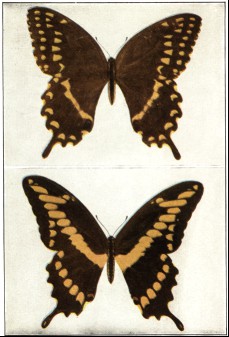

| Giant Swallowtails | 64 |

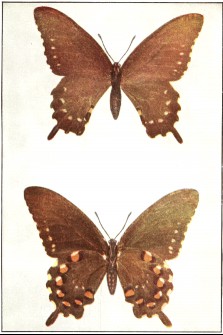

| The Blue Swallowtail | 65 |

| Two of the Swallowtails: Palamedes and Giant | 66 |

| The Green-clouded Swallowtail | 67 |

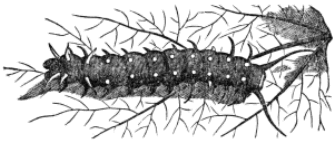

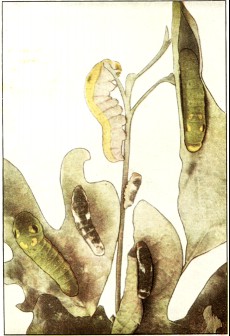

| Caterpillars of the Green-clouded Swallowtail | 80 |

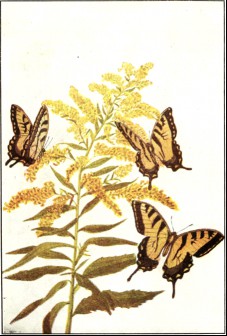

| The Tiger Swallowtail | 96 |

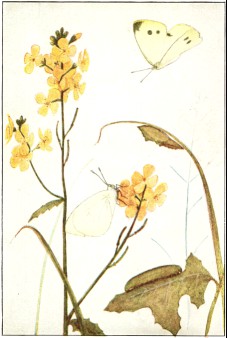

| Imported Cabbage Butterfly | 97 |

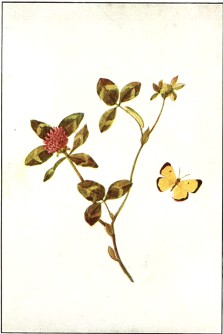

| Clouded Sulphur Butterfly | 112 |

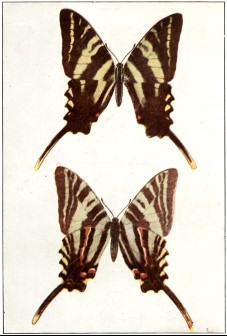

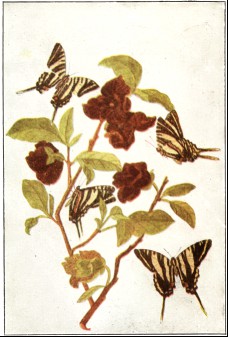

| The Zebra Swallowtail: Summer Form | 112-113 |

| The Zebra Swallowtail Visiting Papaw Blossoms | 112-113 |

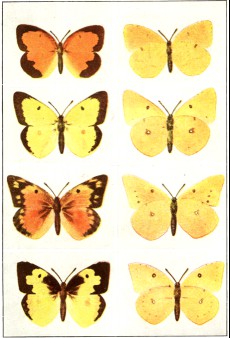

| Some of the Tribe of Yellows | 113 |

| Silver-spot Fritillary and Gulf Fritillary | 128 |

| Gulf Fritillary, Silver-bordered Fritillary, and Baltimore Checker-spot | 129 |

| The Hop Merchant | 144 |

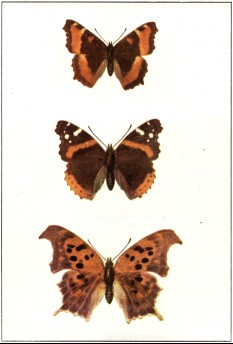

| Three Angle-wings (American Tortoise-shell, Red Admiral, Violet-tip): Upper Surface [Pg xii] | 160-161 |

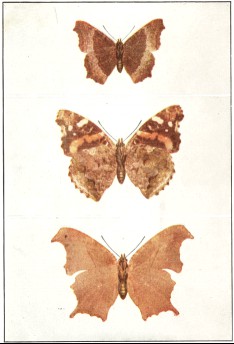

| Three Angle-wings (American Tortoise-shell, Red Admiral, Violet-tip): Lower Surface | 160-161 |

| The Painted Beauty | 161 |

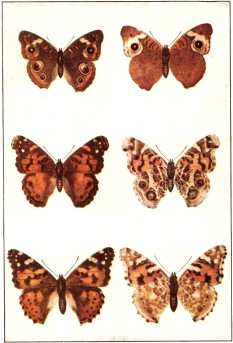

| Three More Angle-wings, Buckeye, Painted Beauty, Cosmopolite | 176 |

| The Mourning-cloak | 177 |

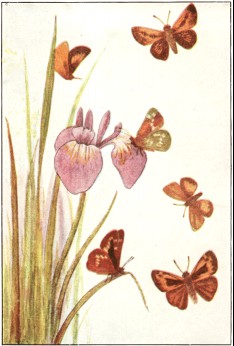

| Some Common Skippers | 192 |

| The Stages of the Viceroy | 193 |

| Banded Purple, Red-spotted Purple, and Blue-eyed Grayling | 208 |

| Three Emperor Butterflies | 209 |

| The Zebra Butterfly | 224 |

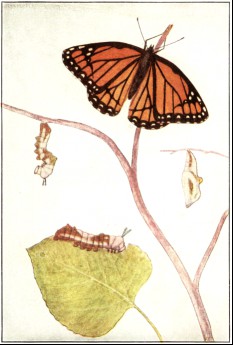

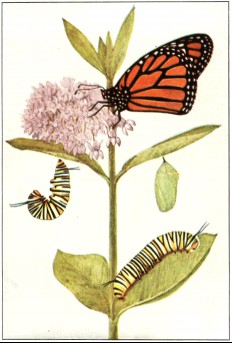

| Monarch Butterfly, Crysalis and Caterpillar | 241 |

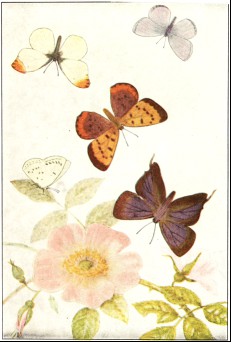

| Spring Azure, Falcate Orange-tip, Bronze Copper, and Great Purple Hair-streak | 256 |

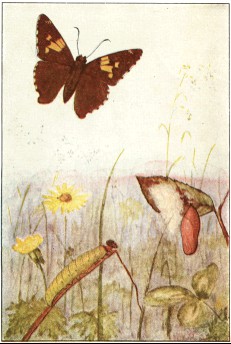

| Silver-spotted Skipper | 273 |

[Pg xiii]

LIST OF OTHER PLATES

| PAGE | |

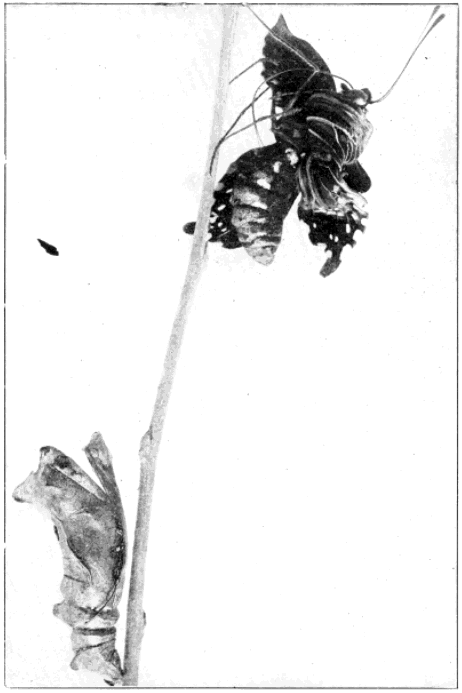

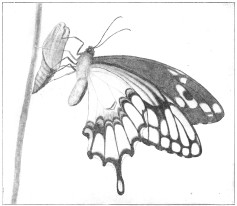

| Swallowtail Butterfly Just Out of Chrysalis | 16 |

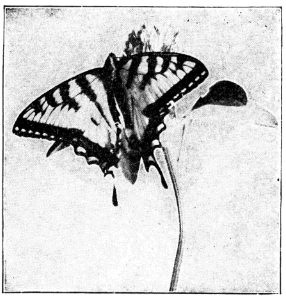

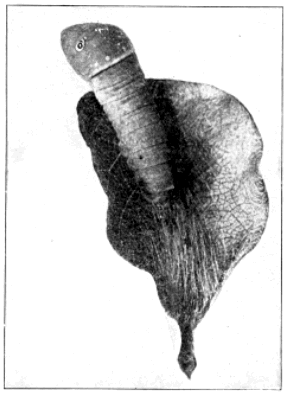

| Tiger Swallowtail; Hammock Caterpillar | 17 |

| Butterfly Feigning Death; Butterfly in Hibernating Position | 32 |

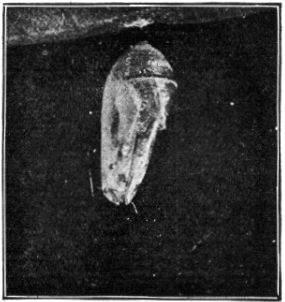

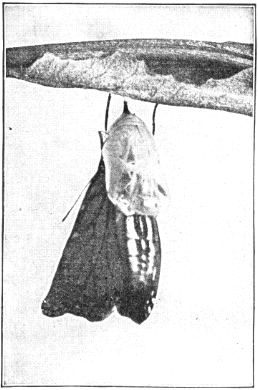

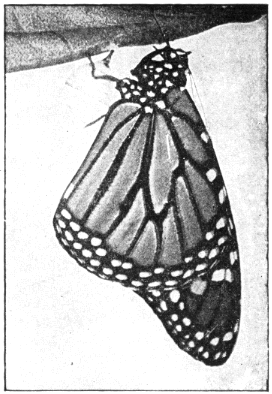

| Monarch Butterfly: Change from Caterpillar to Chrysalis | 32-33 |

| Monarch Butterfly: Change from Chrysalis to Adult | 32-33 |

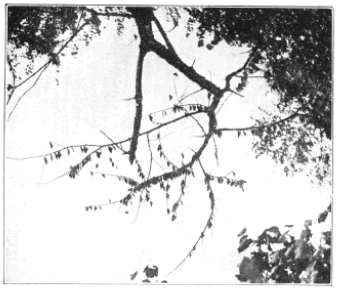

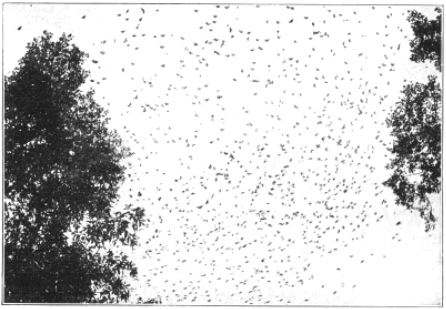

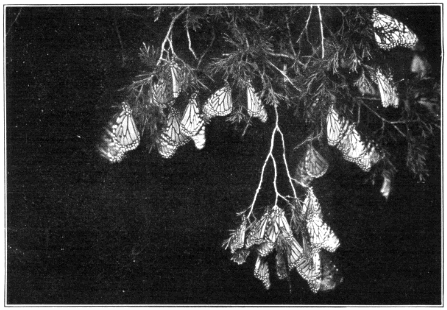

| Migration of Monarch Butterflies | 48-49 |

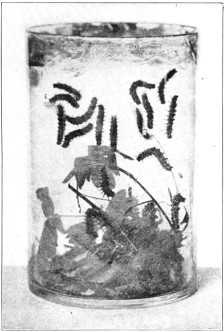

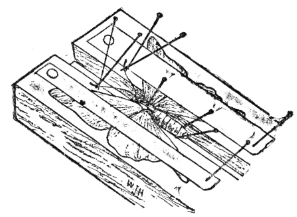

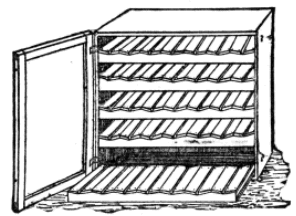

| The Improved Open Vivarium | 48-49 |

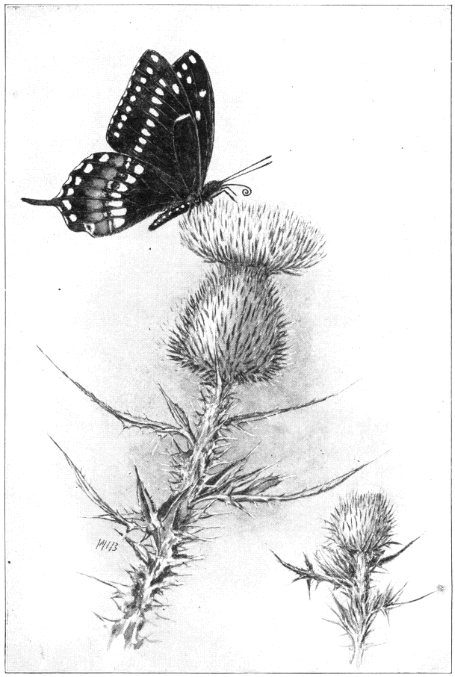

| Black Swallowtail Visiting Thistle | 64-65 |

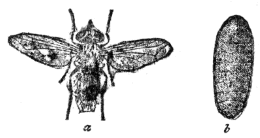

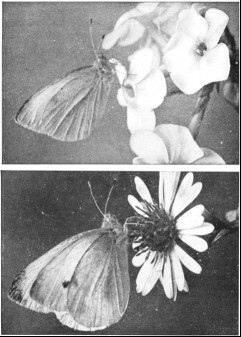

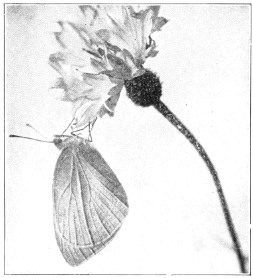

| Imported Cabbage Butterfly, Magnified | 64-65 |

| Imported Cabbage Butterfly; Blue-eyed Grayling | 81 |

| Four-footed Butterflies: Viceroy and Mourning-cloak | 145 |

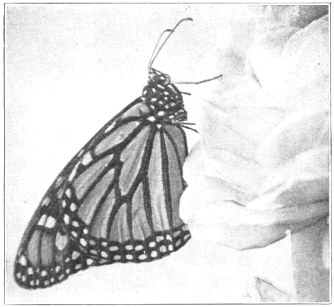

| Monarch Butterfly Resting; Flashlight Photograph of Monarchs in Migration | 160 |

| Photographs of a Pet Monarch Butterfly | 225 |

| The Snout Butterfly; the Giant Swallowtail | 240 |

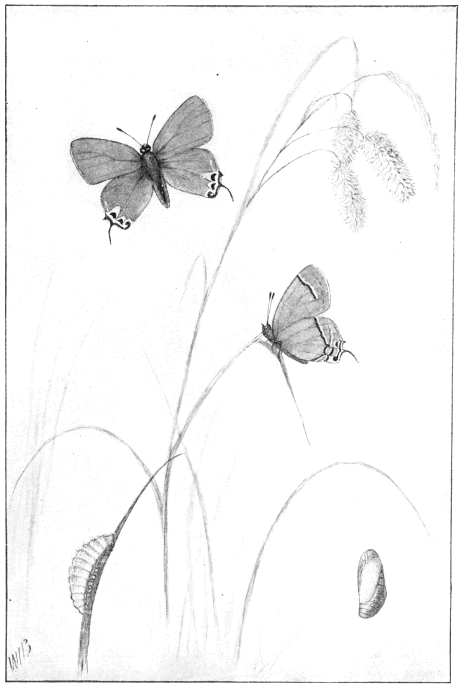

| Stages of the Gray Hair-streak | 257 |

| The Silver-spotted Skipper | 272 |

[Pg xiv]

[Pg 1]

[Pg 2]

[Pg 3]

[↑ TOC]

INTRODUCTION

In popular esteem the butterflies among the insects are

what the birds are among the higher animals—the most

attractive and beautiful members of the great group to

which they belong. They are primarily day fliers and are

remarkable for the delicacy and beauty of their membranous

wings, covered with myriads of tiny scales that overlap

one another like the shingles on a house and show an infinite

variety of hue through the coloring of the scales and

their arrangement upon the translucent membrane running

between the wing veins. It is this characteristic

structure of the wings that gives to the great order of

butterflies and moths its name Lepidoptera, meaning scale-winged.

In the general structure of the body, the butterflies resemble

other insects. There are three chief divisions:

head, thorax, and abdomen. The head bears the principal

sense organs; the thorax, the organs of locomotion; and the

abdomen, the organs of reproduction.

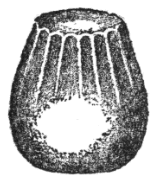

Butterfly Antennae, magnified. (From Holland)

By examining a butterfly's head through a lens it is easy

to see the principal appendages which it bears. Projecting

forward from the middle of the top is a pair of long feelers

or antennae. Each of these consists of short joints which

[Pg 4]

in general may be divided into three groups: first, a few

large joints at the base connecting the feeler with the head;

second, many rather small joints which make up the principal

length; third, several larger joints which make up the

outer part or "club" of the antennæ. In the case of the

Skippers, there are in addition a number of small joints

coming to a sharp point at the end of the club. Just below

the insertion of the antennae on each side of the head

are the large compound

eyes, which are

almost hemispherical.

With a powerful glass,

one can see the honeycomb-like

facets, of

which there are thousands,

making up

each eye. Just below

the eyes there are two hairy projections, called the palpi,

between which is the coiled tongue or sucking tube. (See

plate, page 64-65.)

Anatomically the thorax is divided into three parts—the

prothorax, the mesathorax, and the metathorax; but

the lines of division between these parts are not easily

seen without denuding the skin of its hairy covering. The

prothorax bears the first pair of legs. The mesathorax

bears the front pair of wings and the second pair of legs.

The metathorax bears the hind pair of wings and the

third pair of legs. In many butterflies, the first pair of legs

are so reduced in size that they are not used in walking.

The abdomen is composed of eight or nine distinct rings

or segments, most of which have two spiracles or breathing

pores, one on each side. It also bears upon the end of the

[Pg 5]

body the ovipositor of the female or the clasping organs of

the male.

Butterfly Transformations

The butterflies furnish the best known examples of insect

transformations. The change from the egg to the

caterpillar or larva, from the caterpillar to the pupa or

chrysalis, and from the chrysalis to the butterfly or imago

is doubtless the most generally known fact

concerning the life histories of insects. It

is a typical example of what are called complete

transformations as distinguished from

the manner of growth of grasshoppers,

crickets, and many other insects in which

the young that hatches from the egg bears

a general resemblance to the adult and in

which there is no quiet chrysalis stage

when the little creature is unable to eat or to move

about.

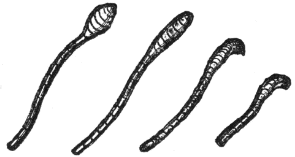

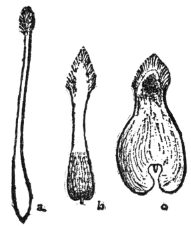

Egg of Baltimore Butterfly, much magnified.

(From Holland)

Caterpillars are like snakes in at least one respect: in

order to provide for their increase in size they shed their

skins. When a caterpillar hatches from the egg it is a

tiny creature with a soft skin over most of its body but

with rather a firm covering for its head. While we might

fancy that there could be a considerable increase in size

provided for by the stretching of the soft skin it is easy to

see that the hard covering of the head will not admit of

this. So the story of the growth of a caterpillar may be

told in this way:

A butterfly lays an egg upon a leaf. Some days later

[Pg 6]

the egg hatches into a larva, which is the technical

name for the second stage of an insect's life. In the case

of the butterfly we call this larva a caterpillar. The little

caterpillar is likely to take its first meal by eating the

empty egg shell. This is a curious habit, and a really

satisfactory explanation of it seems not to have been made.

Its next meal is likely to be taken from the green tissues of

the leaf, commonly the green outer surface only being

eaten at this time. The future meals are also taken from

the leaf, more and more being eaten as the larva gets

older.

After a few days of this feeding upon the leaf tissues the

little caterpillar becomes so crowded within the skin with

which it was born that it is necessary to have a larger one.

So a new skin begins to form beneath the first one. Consequently

the latter splits open in a straight line part way

down the middle of the back just behind the head. Then

the new head covering is withdrawn from the old one and

the caterpillar wriggles its way out of the split skin and

finds itself clothed in a new one. At first all of the tissues

of the new skin are soft and pliable and they easily take on

a larger size as the body of the caterpillar expands. A

little later these tissues become hardened and no further

expansion is possible.

This process of skin-shedding is called moulting. The

cast skin is often called the exuviae. The period of the

caterpillar's life between the hatching from the egg and

this moult is often called a stage or instar—that is, the

caterpillar up to the time of this moult is living in the first

caterpillar stage or instar.

During the actual moulting the caterpillar is quite

[Pg 7]

active in freeing itself from the exuviae. But as soon as it

is free it is likely to rest quietly for some hours while the

tissues of the new skin are hardening. Then it begins

feeding upon the leaf again and continues taking its meals

at more or less regular intervals for several days. By that

time it will again have reached its limit of growth within

this second skin and the process of moulting must be repeated.

It takes place in the same way as before and the

caterpillar enters upon the third instar of its larval life.

This process of feeding and moulting is continued for

several weeks, the number of moults being usually four.

During the later stages the increase in size is more marked

each time the skin is shed, until the caterpillar finally

reaches its full growth as a larva and is ready for the wonderful

change to the quiet chrysalis in which all its caterpillar

organs are to be transformed into the very different

organs of the butterfly.

In the case of butterfly larvae one of the most interesting

features of the growth of the caterpillar is that of the remarkable

changes in colors and patterns of marking which

the caterpillar undergoes. One who had not followed

these changes would often be at a loss to recognize caterpillars

of slightly differing sizes as belonging to the same

species. These changes commonly show a remarkable

adaptation to the conditions of life, and generally tend to

the concealment of the caterpillar upon its food plant.

The stages of growth of the green-clouded swallowtail caterpillar

are illustrated on plate opposite page 80.

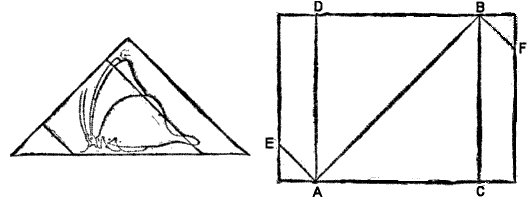

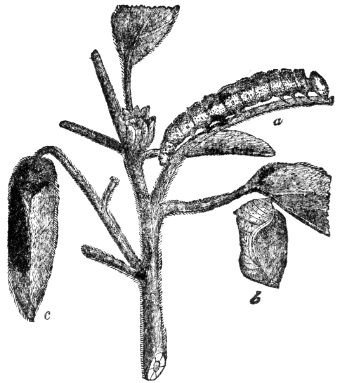

Before each moult the caterpillar is likely to spin a

silken web upon the leaf surface. It then entangles its

claws in the web to hold itself in place while the skin is

cast. (See plate, page 17.)

[Pg 8]

(See plate, pages 32-33.)

A week or ten days after the last moult of its caterpillar

growth the larva commonly becomes full fed and ready to

change to the chrysalis state. The details of the way in

which this is accomplished vary greatly with different

butterflies, as will be noted in the stories of many species

later in this book. In general, however, the caterpillar

provides a web of silk which it spins against some surface

where the chrysalis will be secure and in this web it entangles

its hind legs.

Sometimes there is the

additional protection

of a loop of silk over

the front end of the

body. After the legs

have become entangled

the caterpillar hangs

downward until the

skin splits open along

the median line of the back and gradually shrinks upward

until it is almost free, showing as it comes off a curious

creature which has some of the characteristic features of a

chrysalis. It is seldom at this stage of the same shape

as the chrysalis. When the caterpillar's skin is nearly

off this chrysalis-like object usually wriggles its body

quickly in a manner to entangle a curious set of hooks

attached to the upper end in the web of silken thread.

This hook-like projection is called the cremaster, and it

serves a very important purpose in holding the chrysalis

in position.

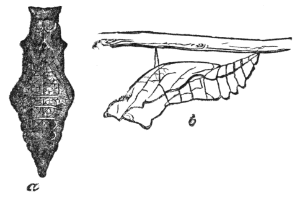

Swallowtail Chrysalis, showing (b) the

loop of silk over thorax. (After Riley)

As soon as the cremaster is entangled in the web the cast

[Pg 9]

skin usually falls off and for a very short period the creature

hanging seems to be neither caterpillar nor chrysalis.

It is in fact in a transition stage between the two, and it

very soon shortens up and takes on the definite form of the

chrysalis, the outer tissues hardening into the characteristic

chrysalis skin.

From the fact that this chrysalis skin shows many of the

characteristic features of the future butterfly it is evident

that the change from the caterpillar to the butterfly really

began during the life of the larva. The nature of the

process by which this change takes place has long been a

puzzle to scientists. For the making of a butterfly is one

of the most wonderful phenomena in the outer world, and

it has challenged the attention of many acute observers.

Some two centuries ago the great Dutch naturalist, Swammerdam,

studied very carefully the development of many

insects, especially the butterfly. He found that if he

placed in boiling water a caterpillar that was ready to

pupate or become a chrysalis, the outer skin could easily be

removed, revealing beneath the immature butterfly with

well-developed legs and antennae. From these observations

he was led to believe that the process of growth was

simply a process of unfolding; that is, as Professor Packard

has expressed it, "That the form of the larva, pupa, and

imago preëxisted in the egg and even in the ovary; and that

the insects in these stages were distinct animals, contained

one inside the other, like a nest of boxes or a series of envelopes

one within the other." This was called the incasement

theory and it was held to be correct by naturalists

for nearly a century. It was discredited, however,

about a hundred years ago, but not until another fifty

[Pg 10]

years had passed was it definitely replaced by another and

much more convincing theory propounded by Weismann.

According to Weismann's theory, which is now well-established,

the process of development internally is a

much more continuous one than the external changes

would indicate. So far as the latter are concerned we

simply say that a caterpillar changes to a chrysalis and a

chrysalis to a butterfly, the transition in each case requiring

but a very short time. Internally, however, it has

been going on almost continuously from the early life of

the caterpillar. The various organs of the butterfly arise

from certain germinal disks or "imaginal" buds, the word

"imaginal" in this case being an adjective form of imago,

so that the imaginal buds are really simply buds for the

starting of growth of the various organs of the imago or

adult. As the caterpillars approach the chrysalis period

these imaginal buds rapidly develop into the various organs

of the butterfly. This process is helped along by the

breaking down of many of the tissues of the larva, this

broken-down tissue being then utilized for the production

of the new organs. About the time the chrysalis is formed

this breaking-down process becomes very general, so that

the newly formed chrysalis seems largely a mass of creamy

material which is soon used to build up the various parts

of the butterfly through the growth of the imaginal buds.

(See plate, pages 32-33.)

There is probably no phenomenon in the world of living

creatures which has attracted more attention than the

change of the chrysalis into the butterfly. It is not

strange that this is so. We see upon a tree or shrub or wall

[Pg 11]

an inert, apparently lifeless object, having no definite form

with which we can compare it with other things, having

neither eyes nor ears nor wings nor legs—an object apparently

of as little interest as a lifeless piece of rock. A

few minutes later we behold it again and note with astonishment

that this apparently inanimate being has been

suddenly transformed into the most ethereal of the creatures

of earth, with an exquisite beauty that cannot fail

to attract admiration, with wings of most delicate structure

for flying through the air, with eyes of a thousand

facets, with organs of smell that baffle the ingenuity of man

to explain, with vibrant antennae, and a slender tongue

adapted to feeding upon the nectar of flowers—the most

ambrosial of natural food. So it is not strange that this

emergence of a butterfly has long been the theme both of

poets and theologians and that it attracts the admiring

attention of childhood, youth, and age.

Fortunately, this change from chrysalis to butterfly may

readily be observed by any one who will take a little

trouble to rear the caterpillars or to watch chrysalids

found outdoors. The precise method of eclosion, as we

call this new kind of "hatching," varies somewhat with

different species but in general the process is similar

in all.

Those chrysalids which have a light colored outer skin

are especially desirable if we would watch this process.

One can see through the semi-transparent membrane the

developing butterfly within, until finally, just before it is

ready to break out, the markings of the wings and body

show distinctly. If at this time the chrysalis is placed in

the sunshine it is likely to come out at once, so that you can

observe it readily. It usually breaks apart over the head

[Pg 12]

and the newly released legs quickly grasp hold of the empty

skin as well as of the support to which it is attached. It

then hangs downward with a very large abdomen and

with the wings more or less crumpled up, but decidedly

larger than when they were confined within the chrysalis.

The wings, however, soon begin to lengthen as they are

stretched out, probably through the filling of the space by

the body juices. Commonly, the hind pair of wings become

full size before the front ones. In a short time the

wings attain their full size, the abdomen becomes smaller,

through the discharge of a liquid called meconium, and the

butterfly is likely to walk a few steps to a better position

where it will rest quietly for an hour or two while body and

wing tissues harden. After this it is likely to fly away to

lead the free life of a butterfly. (See plate, page 16.)

These changes from larva to chrysalis and from chrysalis

to adult in the case of the Monarch Butterfly are illustrated

on the plates opposite pages 32-33. A little

study of these photographs from life will help greatly to an

understanding of the process.

Some very interesting observations have been made by

Mr. J. Alston Moffat upon the method of the expansion

of the wings. In summarizing his investigations he

writes:

"When a wing is fully expanded, and for an hour or two

after, the membranes can be easily separated. Entrance

for a pin-point between them is to be found at the base of

the wing where the subcostal and median nervures come

close together. The membranes are united at the costal

and inner edges, which have to be cut to get them apart;

but they are free at the outer angle. At that time the

nervures are in two parts, half in one membrane and half

[Pg 13]

in the other, and open in the centre. The fluid which has

been stored up in the pupa enters the winglet at the opening

referred to, expanding the membranes as it passes along

between them, and the nervures at the same time, and when

it has extended to every portion of the wing, then it is fully

expanded. The expanding fluid is of a gummy consistency,

and as it dries, cements the membranes together, also the

edges of the half-nervures, and produces the hollow tubes

with which we are so familiar."

Butterflies and Moths

(From Holland)

The butterflies and moths both belong to the great order

of scale-winged insects—the Lepidoptera. They are distinguished,

however, by certain general characteristics,

which hold true for the most part in both groups. The

butterflies fly by day; the

moths fly by night. All of

the higher butterflies go into

the chrysalis state without

making a silken cocoon,

while most of the higher

moths make such a cocoon.

The bodies of the butterflies

are usually slender, while

those of the larger moths are

stout. The antennae of the

butterflies are generally

slender and commonly enlarged

at the tip into a miniature club. The antennae of

the larger moths are commonly feathery or are long and

slender, tapering gradually toward the tip.

The characteristic features that distinguish a moth from

[Pg 14]

a butterfly are well illustrated in the plate opposite page

49, which shows one of the largest and most beautiful

moths in the world. It is the Cynthia moth. As may

be seen, the newly emerged moth is resting upon the silken

cocoon in which it spent its period as a pupa or chrysalis.

This cocoon was attached by the caterpillar to the twig

from which it hangs at the time it spun the cocoon. The

feathered antennae, the hairy legs, the thick thorax, and

large abdomen—all show very clearly in this side view of

the moth. As will be seen, the wings are large and very

suggestive of those of a butterfly and have the characteristic

eye-spots toward the tip and the crescent marks in the

middle, which are so often found on the wings of the larger

moths.

Some of these large moths on cloudy days occasionally

fly during daylight and, by the uninitiated, they are often

mistaken for large butterflies. One who will notice their

structure, however, will readily see the characteristic

features of the moth.

In the caterpillar stage, there are no hard and fast differences

between the larvae of butterflies and those of the

higher moths. In each case, the insect consists of a worm-like

body, having a small head provided with biting jaws

and simple eyes or ocelli. Back of the head are the three

rings of the thorax, each of which bears a pair of jointed

legs. Back of these three rings there are a considerable

number of other body rings making up the abdomen, on

the middle of which there are commonly four or five pairs

of fleshy prolegs, not jointed but furnished at the tip with

fine claws. At the hind end of the body there is another

pair of prolegs similar in structure.

[Pg 15]

The Scents of Butterflies

Many students of American butterflies have occasionally

mentioned the fact that certain species seem to give off a

distinct scent which has frequently been spoken of as a

pleasing fragrance, suggesting sandalwood or some other

aromatic odor. The general subject as exemplified by

butterflies of other lands has been studied for many years

by Fritz Müller; and certain English entomologists have

paid considerable attention to it. A translation of the

Müller publications and an excellent summary of our present

knowledge of the subject is published in Dr. Longstaff's

book on butterfly hunting.

The odors given off by butterflies are divided into two

principal kinds, namely: first, those which are repulsive to

the senses of man, and evidently for the purpose of protecting

the butterflies from birds and other vertebrate

enemies—these are found in both

sexes; second, those which are

evidently for the purpose of sexual

attraction and confined to the male

butterflies—these scents are usually

attractive to the senses of man.

The aromatic scents of the second

group are generally produced by

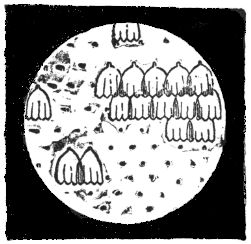

means of certain scales or hairs of

many curious forms, which are

scattered over the surface of the

wings or are placed within certain

special pockets, generally near the borders of the wings.

These scales or hairs are called androconia. Some of them

much magnified are represented in the picture above.

Our knowledge of the scents given off by American

[Pg 16]

butterflies is very fragmentary, and it is highly desirable

that many more observations should be made upon the

subject. If collectors generally would make careful notes,

both in the field and upon the freshly killed butterflies at

home, we ought soon to be able greatly to extend our

knowledge. By holding the butterfly with a pair of forceps,

one can often determine whether the fragrance is

emitted. It is often helpful also to brush the hairs or

tufts where the androconia are attached, using a small, dry

camel's hair brush for the purpose.

Butterfly Migrations

Migration seems to be a general instinct in the animal

world, developed when a species becomes enormously

abundant. At such times this instinct apparently overcomes

all others and the creatures move on regardless of

obstacles and conditions that may mean certain death to

the vast majority. Such migrations among mammals

have often been recorded, one of the most notable examples

being that of the little lemmings which migrate at

periodical intervals in a way which has often been described.

Among the insects such migrations have been

frequently noticed, and the phenomenon has apparently

been observed oftener among the butterflies than in any

other group. Entomological literature during the last

hundred years contains a great many records of enormous

flights of butterflies over long distances, extending even

from Africa into Europe or from one part of America to

another far remote. As such migration is likely to happen

whenever a species becomes extremely abundant it probably

is Nature's way of providing for an extended food

supply for the succeeding generations. That it results in

the death of the great majority of the migrants is doubtless

true, but it must lead to vast experiments in extending

the geographic area inhabited by these species. Numerous

examples of such migrating swarms will be found in the

pages of this little book. (See plates, pages 17, 48-49, 160.)

THE CHRYSALIS SKIN BELOW

The migrations thus considered are only exceptional

[Pg 17]

occurrences. There is, however, a regularly recurring

annual migration on the part of some butterflies which is

also a phenomenon of extraordinary interest. The most

notable example is that of the Monarch which apparently

follows the birds southward every autumn and comes northward

again in spring. There is much evidence to indicate

that in some slight degree other butterflies have a

similar habit, although the present observations are inadequate

to determine to what extent this habit has become

fixed in most of these species.

Hibernation or Winter Lethargy

The ways in which butterflies spend the winter are always

of peculiar interest to the naturalist. Here are

creatures with four distinct stages of existence, each of

which has the possibility of carrying the species through

the season of cold. It is necessary to learn for each insect

which stage has been chosen for the purpose, and if

possible to find the reasons for the choice.

As a rule the related members of a group are likely to

hibernate in a similar stage. Thus most of the Swallowtails

pass the winter as chrysalids while practically all the

Angle-wings pass the winter as adults. This rule, however,

[Pg 18]

has many exceptions, for one will often find closely

related species which differ in the stage of hibernation.

As one would expect, the conditions of hibernation vary

greatly with the latitude. In the severe climate of the far

north the conditions are likely to be more uniform than

in the South where the milder climate permits greater variation

to the insect. In some cases where a butterfly

hibernates in only one stage in Canada it may pass the

winter in two or more stages in Alabama or Florida.

In many other orders of insects the egg is a favorite stage

for hibernation. Even in the closely related moths it is

often chosen by many species, but comparatively few butterflies

pass the winter in the egg stage. The little Bronze

Copper may serve as one example of this limited group.

The conditions as to hibernation by the larvae of butterflies

are very different from those of the egg. It has been

estimated that probably half of all our species pass the

winter in some stage of caterpillar growth. This varies all

the way from the newly hatched caterpillar which hibernates

without tasting food to the fully grown caterpillar

which hibernates full fed and changes to a chrysalis in

spring without eating anything at that time. A large proportion,

however, feed both in fall and spring, going

through the winter when approximately half grown.

The Graylings and the Fritillaries are typical examples

of butterflies which hibernate as newly hatched larvae.

The eggs are laid in autumn upon or near the food plants

and the caterpillars gnaw their way out of the shells and

seek seclusion at once, finding such shelter as they may

in the materials on the soil surface. In spring they begin

to feed as soon as the weather permits and complete their

growth from then on.

The half-grown caterpillars may hibernate either as free

[Pg 19]

creatures under boards, stones, or in the turfy grass, or

they may be protected by special shelters which they have

provided for themselves in their earlier life. In the case

of the latter each may have a shelter of its own or there

may be a common shelter for a colony of caterpillars.

Among the examples of those hibernating in miscellaneous

situations without special protection the caterpillars of

the Tawny Emperor, the Gray Emperor, the Pearl Crescent,

and some of the Graylings are examples. Among

those which hibernate in individual shelters the Sovereigns,

among which our common Viceroy is most familiar,

are good examples. Among those which hibernate in

a tent woven by the whole colony for the whole colony

the Baltimore or Phaeton butterfly is perhaps the best

example.

The caterpillars that hibernate when full grown may be

grouped in a way somewhat similar to those which are half

grown. Many species simply find such shelter as they

may at or near the soil surface. The Clouded Sulphur is a

good example of these. Others pass the winter in individual

shelters made from a leaf or blade. Several of

the larger Skippers are good examples of this condition.

So far as I know none of our species pass the winter in

colonial shelters when full grown.

It would be natural to suppose that the great majority

of butterflies would be likely to hibernate in the chrysalis

state. Here is a quiet stage in which the insect is unable

to move about or to take any food, in which it seems entirely

dormant and as a rule is fairly well hidden from the

view of enemies. We find, however, that only a rather

small proportion of our butterflies has chosen this stage

for survival through the winter. The most conspicuous

[Pg 20]

examples are the Swallowtails, nearly all of which hibernate

in the chrysalis stage. Other examples are the various

Whites, the Orange-tips, and isolated species like

the Wanderer, and the Spring Azure and the American

Copper. Practically all the butterflies that pass the

winter as chrysalids have a silken loop running around near

the middle of the body which helps to hold them securely

through the long winter months. Apparently none of

those chrysalids which hang straight downward are able to

survive the winter.

An adult butterfly seems a fragile creature to endure the

long cold months of arctic regions. Yet many of our most

beautiful species habitually hibernate as adults, finding

shelter in such situations as hollow trees, the crevices in

rocks, the openings beneath loose bark or even the outer

bark on the under side of a large branch. It is significant

that most of the adult-wintering Angle-wings are northern

rather than southern species, some of them being found in

arctic regions practically around the world. One of the

few southern forms that hibernates as an adult is the Goatweed

Emperor.

These examples are all cases of true hibernation in a

lethargic condition. There are certain butterflies, however,

which pass the winter as adults that remain active

during this period. Obviously this is impossible in latitudes

where the winter is severe, and it involves migration

to a warmer climate. The one notable illustration of this

is the Monarch butterfly which apparently flies southward

to the Gulf states at least and there remains until spring,

when individuals come north again. The southward migration

may be begun in Canada when the butterflies

gather together in enormous flocks that remind one of the

[Pg 21]

gathering of the clans with the migrating birds. This is

one of the least understood of insect activities but it has

been observed so often and over so long a period of years

that there seems to be no questioning the general habit.

Like everything else in relation to living things there are

numerous variations in the prevailing modes of hibernation.

In the case of many species one can find combinations

of two or more stages in which the winter is passed.

Probably if we could observe with sufficient care we might

be able to find somewhere examples of almost any conceivable

double combination—as egg with larva or chrysalis

or adult—the insect hibernating in two of these stages.

Many examples are known in which both chrysalis and

adult of the same species pass the winter and also of those

in which young and well-grown larvae pass the winter.

As one would expect, the conditions as to such combinations

are likely to be more variable in southern than in

northern regions.

Notwithstanding all the attention which has been paid

to butterfly life-histories there is still some uncertainty in

regard to the hibernation of many of our species. One of

the most interesting series of observations which a young

naturalist could undertake would be to learn positively

how each species of butterfly in his locality passes the

winter.

Aestivation or Summer Lethargy

In some species of butterflies there is a special adaptation

to passing through the hottest part of the summer season

in a state of lethargy which is suggestive of the torpor of

the hibernating period. This phase of butterfly existence

[Pg 22]

has not been extensively studied and there are indications

that it exists more generally than has been commonly supposed.

It has been noticed even in northern New England

that some of the Angle-wings seek shelter and become

lethargic during August. Apparently this is an adaptation

to single broodedness, helping to carry the species through

the year without the exhaustion incident to the continued

activity of the butterfly.

In more southern regions, especially in the hot, dry

climates where vegetation withers in midsummer, it is well

known that some caterpillars become lethargic, remaining

inactive until the fall rains start vegetation into

growth. The Orange-sulphur butterfly is a good example

of this.

This summer lethargy offers excellent opportunity for

careful study. Any observer who finds a butterfly hidden

away in summer under boards, the bark of a tree, or in a

stone pile should look carefully to see what species it is and

how the butterfly behaves. Such observations should be

sent to the entomological journals in order that our knowledge

of the subject may be increased.

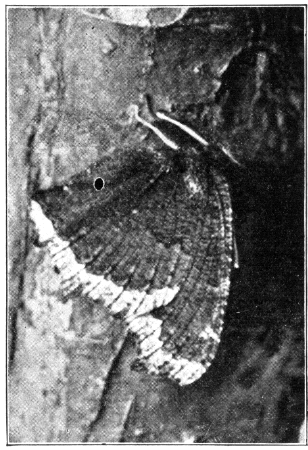

Feigning Death

The fact has long been noticed that various butterflies

have the habit at times of feigning death and dropping to

the ground where they may lie motionless for a considerable

period. This habit is most easily observed in some of

the Angle-wings, especially those which hibernate as

adults. Those species have the under surfaces of their

wings colored in various bark-picturing patterns and apparently

live through the winter to some extent, resting

[Pg 23]

beneath the bark of large branches or upon the trunks of

trees. Many of them also secrete themselves in hollow

trees or beneath loose bark or in board piles or stone walls.

It is probable, however, that during the long ages when

these insects were adapting themselves to their life conditions,

before man interfered with the natural order and

furnished various more or less artificial places for hibernation,

these butterflies rested more generally upon the under

side of branches than they do now.

Even in warm weather when one of these butterflies is

suddenly disturbed it is likely to fold its legs upon its body

and drop to the ground, allowing itself to be handled without

showing any signs of life. This habit is doubtless of

value, especially during hibernation or possibly during the

summer lethargy or aestivation, the latter a habit which

may be more general among these butterflies than is now

supposed. As the insect lies motionless upon the ground

it is very likely to blend so thoroughly with its surroundings

that it becomes concealed, and any bird which had

startled it from the branch above would have difficulty in

finding it.

Some very interesting observations have been made

upon the death-feigning instincts of various other insects,

especially the beetles. But no one so far as I know has yet

made an extended study of the subject in relation to our

American butterflies. It is an excellent field for investigation

and offers unusual opportunities for photographic

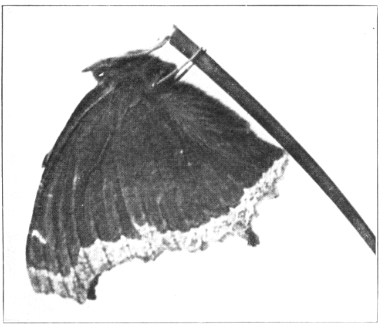

records. One of the pictures opposite page 32 shows a

photograph which I took of a Mourning Cloak as it was

thus playing 'possum. This species exhibits the instinct

to a marked degree.

[Pg 24]

Coloration

The caterpillars of butterflies and moths form a large

part of the food of insect-eating birds. These caterpillars

are especially adapted for such a purpose and in the economy

of nature they play a very important part in keeping

alive the feathered tribes. During the long ages through

which both birds and insects have been developing side by

side, there have been many remarkable inter-relations established

which tend on the one hand to prevent the birds

from exterminating the insects and on the other to prevent

the insects from causing the birds to starve. The most

important of these, so far as the caterpillars are concerned,

are the various devices by which these insects protect

themselves from attack, by hiding away where birds are

not likely to find them, by clothing their bodies with

spiny hairs, by other methods of rendering themselves distasteful,

or by various phases of concealing coloration.

On the whole, the examples of the latter are not so numerous

or so easily found in the case of the larvae of butterflies

as in those of moths.

Perhaps the basal principle of concealing coloration is

the law of counter-shading, first partially announced by

Prof. E. B. Poulton, and later much more elaborately

worked out by Mr. Abbott H. Thayer, and discussed at

length by Mr. Gerald H. Thayer in his remarkable volume,

"Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom." The

law of counter-shading is tersely stated in these words:

"Animals are painted by nature darkest on those parts

which tend to be most lighted by the sky's light and vice

versa." As this law works out on most animals that live

on or near the ground, the upper part of the body exposed

[Pg 25]

to the direct light from above is dark; and the under part,

shut off from the upper light and receiving only the small

reflection from below, is enough lighter to make the appearance

of the creature in its natural environment of a

uniform tone from back to breast.

Nearly all caterpillars illustrate this law of counter-shading.

If they are in the habit of feeding or resting with

their feet downward the back will be darker and the under

side lighter, but if they are in the habit of feeding or

resting in the opposite position these color tones will be

reversed. One can find examples of such conditions almost

any summer's day by a little searching of trees or

shrubs.

This law of counter-shading, however, is really only the

basis for the coloration of caterpillars or other animals. It

tends, chiefly, to make the creature appear as a flat plane

when seen from the side, and may be said in a way to prepare

the canvas upon which Nature paints her more distinctive

pictures. A great many examples of color markings

that tend to conceal the caterpillar amid its natural

surroundings may be found by any one who will study the

subject and it offers one of the most interesting fields for

investigation. The chapter on caterpillars in the above-mentioned

book by Mr. Thayer should serve as a starting

point for any one taking up the subject.

Butterflies differ from caterpillars and from most other

animals in the fact that their coloring is chiefly shown upon

the flat surfaces of the wings. Consequently, there is less

opportunity for the various phases of counter-shading

which is so commonly shown in the larger caterpillars.

The bodies of nearly all butterflies do exhibit this phenomenon,

but these bodies are relatively so small that counter-shading

[Pg 26]

plays but a little part in the general display.

Upon the outstretched membranes of the butterflies'

wings Nature through the long ages of development has

painted a great variety of pictures. Those which tend to

protect the insect by concealment amid its surroundings are

most commonly spread on the under surface of the wings.

Especially is this true in the case of those species which

pass the winter as adults or which have the habit of resting

upon the bark of trees, the sides of rocks, or the surface of

the ground. We here find some of the most interesting

examples of obliterative coloring that occur in nature.

Some butterflies have taken on the look of tree bark,

others the sombre appearance of weathered rocks, while

still others are painted with the images of flowerets and

their stems.

Many of the butterflies, especially the Angle-wings,

which are marked on the under surface in various protective

colors, are admirable examples of that phase of

animal coloring which is spoken of as dazzling coloration.

This is apparently one of the most important protective

devices to be found in Nature and the validity of it is now

generally conceded by naturalists. One phase of it, which

may be called eclipsing coloration, seems to have been first

definitely formulated by the late Lord Walsingham, a

famous English entomologist who enunciated it in an address

as president of the Entomological Society of London.

The most significant paragraphs in that address were these:

"My attention was lately drawn to a passage in Herbert

Spencer's 'Essay on the Morals of Trade.' He writes:

'As when tasting different foods or wines the palate is disabled

[Pg 27]

by something strongly flavored from appreciating

the more delicate flavor of another thing afterward taken,

so with the other organs of sense a temporary disability

follows an excessive stimulation. This holds not only

with the eyes in judging of colors, but also with the fingers

in judging of texture.'

"Here, I think, we have an explanation of the principle

on which protection is undoubtedly afforded to certain insects

by the possession of bright coloring on such parts of

their wings or bodies as can be instantly covered and concealed

at will. It is an undoubted fact, and one which

must have been observed by nearly all collectors of insects

abroad, and perhaps also in our own country, that it

is more easy to follow with the eye the rapid movements of

a more conspicuous insect soberly and uniformly colored

than those of an insect capable of changing in an instant the

appearance it presents. The eye, having once fixed itself

upon an object of a certain form and color, conveys to the

mind a corresponding impression, and, if that impression

is suddenly found to be unreliable, the instruction which

the mind conveys to the eye becomes also unreliable, and

the rapidity with which the impression and consequent

instruction can be changed cannot always compete successfully

with the rapid transformation effected by the insect

in its effort to escape."

Lord Walsingham then goes on to suggest that this intermittent

play of bright colors probably has as confusing

effect upon birds and other predaceous vertebrates as upon

man; and that on this hypothesis such colors can be

accounted for more satisfactorily than upon any other yet

suggested. Since then the significance of this theory has

been repeatedly pointed out by Professor Poulton, Mr.

[Pg 28]

Abbott H. Thayer, and various other authorities upon

animal coloring. The terms dazzling and eclipsing have

been applied to the phenomenon.

Shortly after Lord Walsingham propounded this theory

I called attention[A] to its fitness in explaining some of the

most interesting color phases shown by American insects,

notably the moths and locusts which have brilliantly

colored under wings and protectively colored upper wings.

[A]

Popular Science Monthly, 1898, "A Game of Hide and Seek." Reprinted

in the Insect World, 1899.

The animals of the north show numberless color phases

of interest. One of the most curious of these is exhibited

by several families of insects in which the outer wings are

protectively colored in dull hues and the under wings

brightly colored. For example, there are many species of

moths belonging to the genus Catocala found throughout

the United States. These are insects of good size,

the larger ones measuring three inches in expanse of

wings, and the majority of them being at least two thirds

that size. Most of them live during the day on the bark of

trees, with their front wings folded together over the back.

The colors and markings of these wings, as well as of the

rest of the exposed portions of the body, are such as to

assimilate closely with the bark of the tree upon which the

insect rests. In such a situation it requires a sharp eye to

detect the presence of the moth, which, unless disturbed,

flies only at night, remaining all day exposed to the attacks

of many enemies. Probably the most important of these

are the birds, especially species like the woodpeckers,

which are constantly exploring all portions of the trunks of

trees.

The chief beauty of these Catocalas, as they are seen

[Pg 29]

spread out in the museum cabinet, lies in the fact that the

hind wings, which, when the moth is at rest in life, are concealed

by the front ones, are brightly colored in contrasting

hues of black, red, and white in various brilliant combinations.

These colors, in connection with the soft and

blended tones of the front wings, make a very handsome

insect.

It is easy to see that when one of these Underwing

Moths is driven to flight by a woodpecker or other bark-searching

bird it would show during its rapid, irregular

flight the bright colors of the under wings which would be

instantly hidden upon alighting and the very different

coloring of the upper wings blending with the bark would

be substituted. Consequently, the bird would be very

likely to be baffled in its pursuit.

On the rocky hills and sandy plains of New England

there are several species of grasshoppers or locusts that

also illustrate these principles. If you walk along a strip

of sandy land in summer, you start to flight certain locusts

which soon alight, and when searched for will be found

closely to assimilate in color the sand upon which they

rest. On a neighboring granite-ribbed hill you will find

few if any of this species of locust, but instead there occur

two or three quite different species, which when at rest

closely resemble the lichen-covered rocks. This resemblance

is very striking, and is found in all stages of the insect's

existence. If now you go to a lowland meadow, still

another color phase will be found to prevail—the green

grass is swarming with the so-called "long-horned" grasshoppers,

[Pg 30]

which are green throughout with linear bodies,

and long, slender legs and antennae.

Each of these three groups of insects is adapted to its

particular habitat. All are constantly persecuted by

birds, and have been so persecuted for unnumbered ages in

the past. In every generation the individuals have

varied, some toward closer resemblance to environment,

others in an opposite direction. The more conspicuous

insects have been constantly taken, and the least conspicuous

as constantly left to reproduce. Were the three

groups to change places to-day, the green grasshoppers

from the meadows going to sandy surfaces, the sand-colored

locusts going to rocky hills, and the "mossbacks"

from the hills to the lowland meadows, each would become

conspicuous, and the birds would have such a feast

as is seldom spread before them.

The species living on sand and rocks are often "flushed"

by birds. Those which flew but a few feet would be

likely to be captured by the pursuing bird; those which

flew farther would stand a better chance of escaping.

Similarly, those which flew slowly and in a straight line

would be more likely to be caught than those which flew

rapidly and took a zigzag course. As a consequence of the

selection thus brought about through the elimination of

those which flew slowly along the straight and narrow way

that led to death, you will find that most locusts living in

exposed situations when startled fly some distance in a

rapid, zigzag manner.

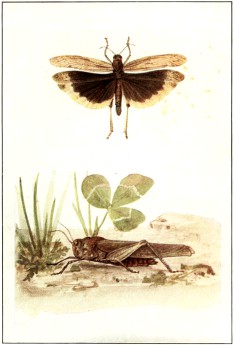

But still another element of safety has been introduced

by some species of these locusts through the adoption of

the color tactics of the Catocala moths. The under wings

of the common Carolina locust—the species most abundant

[Pg 31]

along the highway—are black, bordered with yellowish

white. The base of the hind wings of a related species

living on the Western plains is bluish, while in the large

coral-winged locust of the Eastern states the hind wings

are red, bordered with black. In nearly all of the species

of these locusts frequenting open localities where they are

liable to disturbance by birds or other animals, the hind

wings exhibit contrasting colors in flight. Most of them

also fly in a zigzag line, and alight in a most erratic manner.

Many times I have had difficulty in determining the

exact landfall of one of these peculiar creatures, and I believe

Lord Walsingham's suggestion is well exemplified in

them. (See page 33.)

The most famous example of a combination of this

dazzling coloring of the upper wing surface with a definite

protective coloring of the under wing surface is the Kallima

butterfly which is illustrated in almost every book dealing

with animal coloration. The under wing surface bears a

striking resemblance to a leaf and the hind wings project

to form a tail which looks like the petiole of the leaf, and

there is also a mark running across the wings which

mimics the midrib. When the butterfly is flying the

brilliant colors of the upper surface are visible, but when it

alights these are instantly replaced by the sombre tone

of the under surface, so that apparently the insect completely

disappears and in its place there is only a leaf

attached to a branch in a most natural position. In Dr.

Longstaff's book there is an illustration of another tropical

butterfly, Eronia cleodora, which resembles on its under

surface a yellow disease-stricken leaf but on its upper

surface gives a brilliant combination of black and white.

This insect alights upon the leaves which it resembles

[Pg 32]

and is a striking example of both dazzling and mimicking

coloration.

Many of our own butterflies, notably the Angle-wings,

are excellent examples of a similar combination. In flight

they reveal conspicuous colors which are instantly hidden

upon alighting and then one only sees the bark-like or dead

leaf-like under surface as may be seen in the plate opposite

pages 160-161. The iridescence upon the upper wing surface

of many butterflies, whose under wing surface is colored in

concealing tones, is doubtless also of great use to the insect

in a similar way. There is a splendid opportunity here for

some observer to study this phase of butterfly activity and

to get photographs of the insects amid their natural surroundings.

In their book upon "Concealing Coloration" the Messrs.

Thayer have called attention to many interesting phases

of dazzling coloration. They show that bright marks like

the eye-spots or ocelli, which form so prominent a feature

on the wing surfaces of many butterflies, really helped to

conceal the insect amid its natural surroundings, by drawing

the eye away from the outlines of wings and body so

that the latter tend to disappear. Their discussion of this

subject opens up another vast field for outdoor observations

of absorbing interest, in which there is great need for

many active workers.

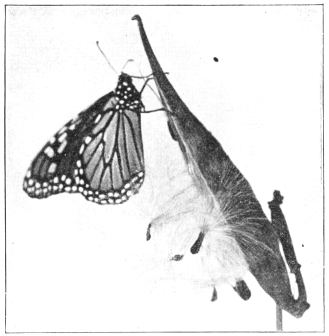

BUTTERFLY FEIGNING DEATH, HANGING

TO BARK BY ONE FOOT

BUTTERFLY IN HIBERNATING POSITION

|  |

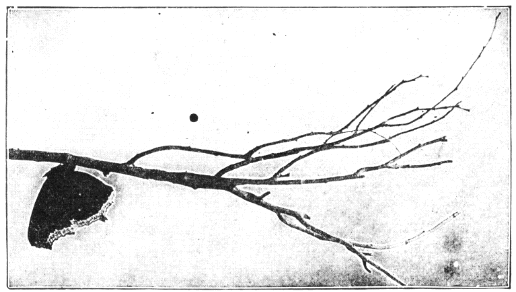

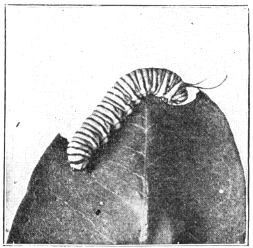

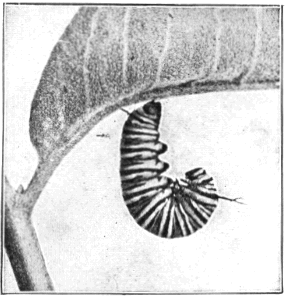

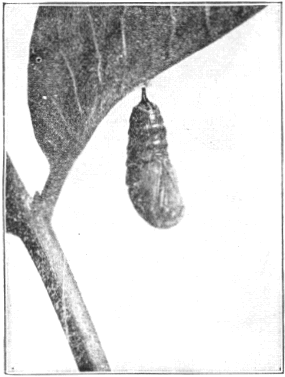

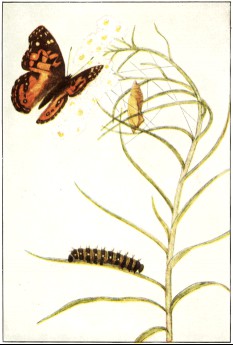

| Caterpillar feeding upon leaf of milkweed | Caterpillar hung up for the change to the chrysalis |

|  |

| The transition stage | The Chrysalis |

Photographs from life. See pages 8-10, 233 THE MONARCH BUTTERFLY: CHANGE FROM CATERPILLAR TO CHRYSALIS. | |

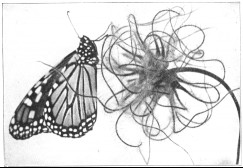

|  |

| Chrysalis showing butterfly ready to emerge | The empty chrysalis |

|  |

| Butterfly just out of chrysalis | Side view a little later |

Photographs from life. See pages 10-13, 235 THE MONARCH BUTTERFLY: THE CHANGE FROM CHRYSALIS TO ADULT. | |

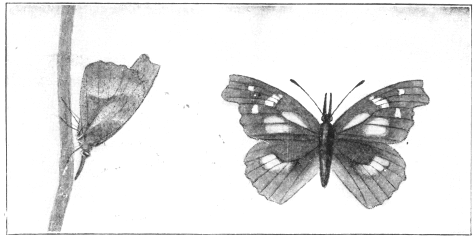

THE CAROLINA LOCUST

Above, with wings expanded as in flight

[Pg 33]

Selective Color Sense

One who collects the Underwing moths soon discovers

that the light colored species which resemble the bark of

birch trees are likely to be found upon the trunks of those

trees, and that the dark colored kinds which resemble the

bark of maple trees are likely to be found upon the trunks

of these. Obviously, were this not true the protective

coloring would avail but little and it is evident that these

moths are able to select a background which is of advantage

in helping to conceal them.

There is much evidence to show that in a similar way the

butterflies are able by means of a well-developed color

sense to select the places where they alight. One of the

most notable examples is that of a South American species,

Peridromia feronia. This is a silvery gray butterfly which

alights head downward upon the bark of certain palm trees

that have silvery gray stems and remains there with its

wings fully expanded so that it utilizes the background in

much the same way that the Underwing moths do.

"When disturbed they will return to the same tree again

and again."

One who will observe the habits of our Angle-wings and

other butterflies which have obliterative coloring of the

under wing surface can easily learn that these insects

select rather carefully the places where they alight. It

will be found that as a rule each species utilizes a background

that blends with its own coloring. It is probable

that this habit is much more common in other groups of butterflies

than has been realized. Much evidence of this sort

has been collected regarding the butterflies of Europe and

other countries, as well as near our own borders in America.

Warning Coloration and Mimicry

The colors of a great many animals, including a considerable

percentage of American butterflies and their

larvae, have been commonly explained by the theory of

warning colors. According to this theory animals which

[Pg 34]

were for any reason not edible by birds and mammals have

developed various striking combinations of color such as

black and yellow, red and black, or black and white, in

order to advertise to their foes their inedible qualities.

This theory has been very generally accepted by naturalists

and will be found expounded at length in many books published

during the last quarter century.

The whole subject of the validity of warning coloration

has recently been brought up for reconsideration by the illuminating

investigations of Mr. Abbott H. Thayer and

discussed at length in the book upon "Concealing Coloration"

already mentioned. In an appendix to this book

dated 1908 Mr. Thayer states that he no longer holds the

belief that "there must somewhere be warning colors."

He has convincingly shown that a large proportion of the

animals which were supposed to be examples of this theory

are really illustrations of concealing coloration. But there

yet remain various facts which have been conclusively

proven that apparently require the theory of warning

colors to explain them. Here is another field in which

there is a real need for much careful investigation under

conditions that are rigidly scientific.

Along with the theory of warning coloration the theory

of mimicry has been propounded. According to this if a

butterfly in a given region shows warning coloration,

having developed such coloration because it is distasteful

to birds and mammals, it may be mimicked by another

butterfly in the same region belonging to another group,

the latter butterfly being edible, but benefiting by its resemblance

to the distasteful species, because birds or

mammals mistake it for the latter and do not attempt to

catch it. The most notable example of such mimicry in

[Pg 35]

North America is that of the Monarch butterfly, which is

supposed to be the distasteful species, and the Viceroy

butterfly, which is supposed to mimic it. Several other

instances of mimicry are found among our own butterflies,

while in South America, Africa, and Asia there are numberless

examples.

Heliotropism

It has long been known that the green surfaces of plants

respond to the stimulus of the sun's rays in a most remarkable

manner. This response has commonly been called

heliotropism and it has been carefully studied by botanists

all over the habitable world. More recently, the fact has

been observed that many animals respond in certain definite

ways to the stimulus of direct sunshine and the same

term has been applied in this case. Very little attention

has been given to the subject of heliotropism until within a

few recent years. But the observations which have been

made by Parker, Longstaff, Dixey, and others open up a

most interesting field for further observation. An admirable

summary of our present knowledge of the subject

has been published by Dr. Longstaff in his book "Butterfly

Hunting in Many Lands."

One of the earliest observations upon this subject was

that published in my book "Nature Biographies" which appeared

in June, 1901, concerning the habit in the Mourning

Cloak: "On a spring-like day early in November (the 8th)

I came across one of these butterflies basking in the sunshine

upon the ties of a railway track. It rested with its

wings wide open. On being disturbed, it would fly a short

distance and then alight, and I was interested to notice

[Pg 36]

that after alighting it would always turn about until the

hind end of its body pointed in the direction of the sun, so

that the sun's rays struck its wings and body nearly at

right angles. I repeatedly observed this habit of getting

into the position in which the most benefit from the sunshine

was received, and it is of interest as showing the extreme

delicacy of perception toward the warmth of sunshine

which these creatures possess."

A little later, some very elaborate observations were

made upon this habit of the Mourning Cloak by Prof.

G. H. Parker of Harvard University. Professor Parker

noticed that during the warm spells in winter the butterflies

came out of their hiding places and after alighting, always

placed themselves with their heads away from the direction

of the sun and their bodies lying nearly at right

angles to the sun's rays. By experiment, he found that

they adjusted themselves to this position as soon as they

were fully exposed to direct sunshine, even if at the time of

alighting they were in a shadow. He found that this

movement was a reflex action through the eyes, for when

the eyes were blinded no such adjustment took place. He

called it negative heliotropism.

Dr. Longstaff uses the term orientation for this adjustment

of the butterfly to the sun's rays and he finds it is a

very general habit, especially with the Angle-wings, for the

butterfly thus to orient itself after alighting, in such a way

that the hind end of the body points toward the sun. This

occurs not only with those species which keep their wings

spread open when they alight but also with those in which

the wings are closed together and held in a vertical position

on alighting.

Various explanations of this phenomenon have been

[Pg 37]

offered but apparently none of them are yet generally

accepted. Were the habit confined to butterflies like the

Mourning Cloak, it would seem easy to prove that a main

advantage was found in the benefit derived from the heat

rays of the sun. Were it confined to those species which

always fold their wings on alighting, it would seem easy to

believe that it was a device for reducing the shadow cast by

the insect to its lowest terms. It has also been suggested

that the habit is for the purpose of revealing to the fullest

extent the markings of the butterfly. Evidently there is

here an ample field for further investigation before definite

conclusions are reached.

List and Shadow Observations

Another field for most interesting studies upon the

habits of living butterflies has been opened up by the very

interesting discussion of list and shadow in Colonel G. B.

Longstaff's fascinating book, "Butterfly Hunting in Many

Lands." He there summarizes his numerous observations

upon butterflies in various localities which he has seen to

lean over at a decided angle when they alight. He defines

"List" as "an attitude resulting from the rotation

of the insect about its longitudinal axis, as heliotropism results

from a rotation about an imaginary vertical axis at

right angles to this." The name is adapted from the

sailors' term applied to a vessel leaning to one side or another

in a storm.

Apparently this interesting habit was first called to the

attention of European entomologists by an observation of

Colonel C. T. Bingham made in 1878, but not published

[Pg 38]

until long afterward. The observation was this:

"The Melanitis was there among dead leaves, its wings

folded and looking for all the world a dead, dry leaf itself.

With regard to Melanitis, I have not seen it recorded anywhere

that the species of this genus when disturbed fly

a little way, drop suddenly into the undergrowth with

closed wings, and invariably lie a little askew and slanting,

which still more increases their likeness to a dead leaf casually

fallen to the ground."

Long before this was printed, however, a similar habit

had been observed by Scudder in the case of our White

Mountain butterfly (Oenis semidea). But this species is

so exceptional in its habitat that the habit seems to have

been considered a special adaptation to the wind-swept

mountain top. The possibility of its being at all general

among the butterflies in lowlands seems to have been overlooked.

The observations recorded by Longstaff relate chiefly to

various members of the Satyrid group. For example, a

common Grayling, Satyrus semele, was watched many

times as it settled on the ground. As a rule three motions

are gone through in regular sequence: the wings are

brought together over the back; the forewings are drawn

between the hind wings; the whole is thrown over to right

or left to the extent of thirty, forty, or even fifty degrees.

This habit, of course, is of advantage to the insect. It

seems possible that the advantage might be explained in

either of two ways: first, the leaning over on the ground

among grasses and fallen leaves might help to render

the disguising coloration of the insect more effective, the

large ocelli serving to draw the eye away from the outline

of body and wing; second, the listing of the butterfly toward

[Pg 39]

the sun tends to reduce the shadow and to hide it beneath

the wings. There is no doubt that when a Grayling

butterfly lights upon the ground in strong sunshine the

shadow it casts is more conspicuous than the insect itself

and the hiding of this might be of distinct advantage in

helping it to escape observation. It is significant that in

England the butterflies observed appear to lean over more

frequently in sunshine than in shade. An observation of

Mr. E. G. Waddilove, reported by Colonel Longstaff, is

interesting in this connection:

"A Grayling settled on a patch of bare black peat earth,

shut up its wings vertically, and crawled at once some two

yards to the edge of the patch to where some fir-needles, a

cone or two, and a few brittle twigs were lying, and then becoming

stationary threw itself over at an angle of some

forty-five degrees square to the sun. It thus became quite

indistinguishable from its surroundings."

Apparently, some of the Angle-wings may have the same

habit, for in Barrett's "Lepidoptera of the British Islands,"

there is a note in regard to Grapta C-album to the effect

that it is fond of sunning itself in roads, on warm walls, or

on the ground upon dead leaves in sheltered valleys.

"Here, if the sun becomes overclouded, it will sometimes

close its wings and almost lie down, in such a manner that

to distinguish its brown and green marbled under side from

the dead leaves is almost impossible."

Here is a most fascinating opportunity for American

observers to determine definitely the facts in regard to our