The Project Gutenberg eBook of Life History of the Kangaroo Rat

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Life History of the Kangaroo Rat

Author: Charles Taylor Vorhies

Walter P. Taylor

Release date: March 11, 2006 [eBook #17966]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Starner, Sigal Alon and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIFE HISTORY OF THE KANGAROO RAT ***

Transcriber's Note:

One correction had been made per attached erratum. It has been marked in the

text with mouse-hover popup showing the original text.

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

BULLETIN No. 1091

Also Technical Bulletin No. 1 of the Agricultural Experiment Station

University of Arizona

| Washington, D. C. | PROFESSIONAL PAPER | September 13, 1922 |

LIFE HISTORY OF THE KANGAROO RAT

Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis Merriam

BY

CHARLES T. VORHIES, Entomologist

Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Arizona; and

WALTER P. TAYLOR, Assistant Biologist

Bureau of Biological Survey, U. S. Department

of Agriculture

CONTENTS

| Importance of Rodent Groups | 1 |

| Identification | 3 |

| Description | 5 |

| Occurrence | 7 |

| Habits | 9 |

| Food and Storage | 18 |

| Burrow Systems, or Dens | 28 |

| Commensals and Enemies | 33 |

| Abundance | 36 |

| Economic Considerations | 36 |

| Summary | 38 |

| Bibliography | 40 |

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

1922

Plate I.—Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis Merriam).

From Dipodomys merriami Mearns and subspecies, which occur over much of its range, this form is easily distinguished by its larger size and the conspicuous white brush on the tail.

[1]

| UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTUREBULLETIN No. 1091Also Technical Bulletin No. 1 of the |  |

| Washington, D. C. | PROFESSIONAL PAPER | September, 1922 |

LIFE HISTORY OF THE KANGAROO RAT,

Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis Merriam.

By Charles T. Vorhies, Entomologist, Agricultural Experiment Station, University

of Arizona; and Walter P. Taylor, Assistant Biologist, Bureau of

Biological Survey, U. S. Department of Agriculture.

CONTENTS.

| Page | |

| Importance of rodent groups | 1 |

| Investigational methods | 2 |

| Identification | 3 |

| Description | 5 |

| General characters | 5 |

| Color | 6 |

| Oil gland | 6 |

| Measurements and weights | 7 |

| Occurrence | 7 |

| General distribution | 7 |

| Habitat | 7 |

| Habits | 9 |

| Evidence of presence | 9 |

| Mounds | 9 |

| Runways and tracks | 10 |

| Signals | 11 |

| Voice | 12 |

| Daily and seasonal activity | 12 |

| Pugnacity and sociability | 13 |

| Sense developments | 14 |

| Movements and attitudes | 15 |

| Storing habits | 15 |

| Breeding habits | 16 |

| Food and storage | 18 |

| Burrow systems, or dens | 28 |

| Commensals and enemies | 33 |

| Commensals | 33 |

| Natural checks | 34 |

| Parasites | 35 |

| Abundance | 36 |

| Economic considerations | 36 |

| Control | 37 |

| Summary | 38 |

| Bibliography | 40 |

Note.—This bulletin, a joint contribution of the Bureau of Biological Survey and the

Arizona Agricultural Experiment Station, contains a summary of the results of investigations

of the relation of a subspecies of kangaroo rat to the carrying capacity of the open

ranges, being one phase of a general study of the life histories of rodent groups as they

affect agriculture, forestry, and grazing.

IMPORTANCE OF RODENT GROUPS.

As the serious character of the depredations by harmful rodents

is recognized, State, Federal, and private expenditures for their

control increase year by year. These depredations include not only

the attacks by introduced rats and mice on food materials stored in

granaries, warehouses, commercial establishments, docks, and private

houses, but also, particularly in the Western States, the ravages of

several groups of native ground squirrels and other noxious rodents

in grain and certain other field crops. Nor is this all, for it has

[2]been found that such rodents as prairie dogs, pocket gophers, marmots,

ground squirrels, and rabbits take appreciable and serious toll

of the forage on the open grazing range; in fact, that they reduce

the carrying capacity of the range to such an extent that expenditures

for control measures are amply justified. Current estimates place

the loss of goods due to rats and mice in warehouses and stores

throughout the United States at no less than $200,000,000 annually,

and damage to the carrying capacity of the open range and to cultivated

crops generally by native rodents in the Western States at

$300,000,000 additional; added together, we have an impressive total

from depredations of rodents.

The distribution and life habits of rodents and the general consideration

of their relation to agriculture, forestry, and grazing, with

special reference to the carrying capacity of stock ranges, is a subject

that has received attention for many years from the Biological Survey

of the United States Department of Agriculture. As a result

of the investigations conducted much has been learned concerning

the economic status of most of the more important groups, and the

knowledge already gained forms the basis of the extensive rodent-control

work already in progress, and in which many States are cooperating

with the bureau. If the work is to be prosecuted intelligently

and the fullest measure of success achieved, it is essential that

the consideration largely of groups as a whole be supplemented by

more exhaustive treatment of the life histories of individual species

and of their place in the biological complex. The present report is

based upon investigations, chiefly in Arizona, of the life history,

habits, and economic status of the banner-tailed kangaroo rat, Dipodomys

spectabilis spectabilis Merriam (Pl. I).

INVESTIGATIONAL METHODS.

Some 18 years ago (in 1903) a tract of land 49.2 square miles in

area on the Coronado National Forest near the Santa Rita Mountains,

Pima County, southern Arizona, was closed to grazing by arrangement

between the Forest Service and the Agricultural Experiment

Station of the University of Arizona. Since that time another small

tract of nearly a section has been inclosed (Griffiths, 1910, 7[1]). This

total area of approximately 50 square miles is known as the United

States Range Reserve, and is being devoted to a study of grazing conditions

in this section and to working out the best methods of administering

the range (Pl. II, Fig. 1).

[3]For some years an intensive study of the forage and other vegetative

conditions of this area has been made, the permanent vegetation

quadrat, as proposed by Dr. F. E. Clements (1905, 161-175), being

largely utilized. During the autumn of 1917 representatives of the

Carnegie Institution and the Arizona Agricultural Experiment Station

visited the Reserve and were impressed with the evidence of

rodent damage to the grass cover. The most conspicuous appearance

of damage was noted about the habitations of the banner-tailed

kangaroo rat (Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis Merriam), although

it was observed also that jack rabbits of two species (Lepus californicus

eremicus Allen and L. alleni alleni Mearns), which were very

abundant in some portions of the reserve, were apparently affecting

adversely the forage conditions in particular localities. Accordingly,

the Biological Survey, the Agricultural Experiment Station of the

University of Arizona, the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and

the U. S. Forest Service have undertaken a study of the relation of

the more important rodents to the forage crop of the Range Reserve

in Arizona.

The present paper is a first step in this larger investigation.[2] In

this work the authors have made no attempt to deal with the taxonomic

side of the kangaroo rat problem. It is not unlikely that

intensive studies will show that the form now known as Dipodomys

spectabilis spectabilis is made up of a number of local variants, some

of them perhaps worthy of recognition as additional subspecies. But

it is felt that the conclusions here reached will be little, if at all,

affected by such developments.

Color descriptions are based on Ridgway's Color Standards and

Color Nomenclature published in 1912.

IDENTIFICATION.

There are only three groups of mammals in the Southwest having

external cheek pouches. These are (a) the pocket gophers (Geomyidæ),

which have strong fore feet, relatively weak hind feet, and

short tail, as compared with weak fore feet, relatively strong hind

feet, and long tail in the other two; (b) the pocket mice (Perognathus),

which are considerably smaller than the kangaroo rats and[4]

lack the conspicuous white hip stripe possessed by all the latter; and

(c) the kangaroo rats (Dipodomys).

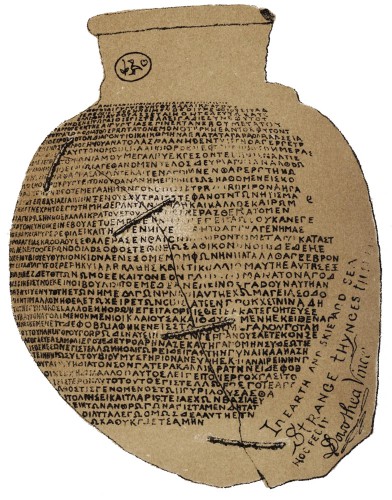

Fig. 1.—Range, east of the Colorado River, of Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis compared

with that of Dipodomys merriami. Cross hatching indicates area of overlapping

of the two forms. The range of Dipodomys deserti, not shown on the map, is west of

that of spectabilis, and so far as known the two do not overlap.

Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis Merriam requires comparison

with three other forms of kangaroo rats in the same general region,

namely, D. deserti Stephens, of approximately the same size,

and D. merriami Mearns and D. ordii Woodhouse, the last two of

decidedly smaller size. The range of deserti lies principally to the

west of that of spectabilis, and the two do not, so far as known, overlap.

On the other hand, merriami and ordii, and subspecies, occur over

a large part of the range of spectabilis, living in very close proximity

to its burrows; merriami is even suspected of pillaging the stores of

spectabilis. The range of merriami, however, is much more extensive

than that of spectabilis (Fig. 1), which argues against a definite

ecological dependence or relationship. Separation of the four forms

mentioned may be easily accomplished by the following key:

[5]Key to Species of Dipodomys in Arizona.

a1. Size much larger (hind foot and greatest length of skull more than 42

millimeters); tail tipped with white.

b1. Upper parts dark brownish buffy; tail dark brownish or blackish

with more sharply contrasted white tip; interparietal broader,

distinctly separating mastoids (range in Arizona mainly southeastern

part)Dipodomys spectabilis.

b2. Upper parts light ochraceous-buffy; tail pale brownish with less

sharply contrasted white tip; interparietal narrower, reduced to

mere spicule between mastoids (range in Arizona mainly southwestern

part)) Dipodomys deserti.

a2. Size much smaller (hind foot and greatest length of skull less than

42 millimeters); tail not tipped with white.

b1. Hind foot with four toes

Dipodomys merriami.

b2. Hind foot with five toes

Dipodomys ordii.

On account of the small size, merriami and ordii do not require

detailed color comparison with the other two. The general color of

the upperparts of spectabilis is much darker than that of deserti;

whereas spectabilis is ochraceous-buff or light ochraceous-buff grizzled

with blackish, deserti is near pale ochraceous-buff and lacks the

blackish.

The color of the upperparts alone amply suffices to distinguish

spectabilis and deserti; but the different coloration of the tail is the

most obvious diagnostic feature. The near black of the middle portion

of the tail, the conspicuous white side stripes, and the pure

white tip make the tail of spectabilis stand in rather vivid contrast

to the pale-brown and whitish tail of deserti.

The dens of the two larger species of Dipodomys—spectabilis and

deserti—can be distinguished at a glance from those of the two

smaller—merriami and ordii—by the fact that the mounds of the

former are usually of considerable size and the burrow mouths are

of greater diameter. On the Range Reserve merriami erects no

mounds, but excavates its burrows in the open or at the base of

Prosopis, Lycium, or other brush. The mounds of spectabilis are

higher than those of deserti, the entrances are larger, and they are

located in harder soil (Pl. III, Fig. 1). The dens of deserti are

usually more extensive in surface area than those of spectabilis, and

have a greater number of openings (Pl. III, Fig. 2).

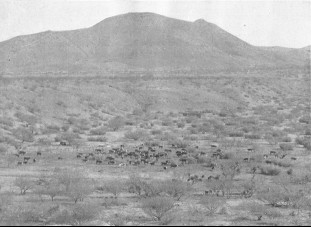

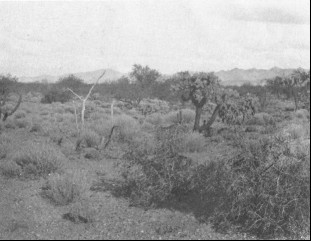

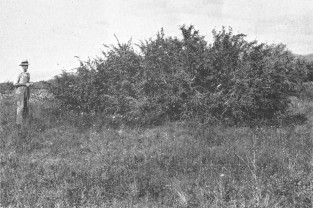

Plate II. Fig. 1.—Winter View of Area Inhabited by Kangaroo Rats.

A water-hole scene on the U. S. Range Reserve at the base of the Santa Rita Mountains, Ariz.,

where cooperative investigations are being conducted to ascertain the relation of rodents to

forage. This is typical of a large section of country occupied by Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis

and Dipodomys merriami. The brush is mesquite (Prosopis), cat's-claw (Acacia), and paloverde

(Cercidium).

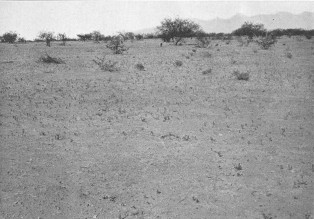

Plate II. Fig. 2.—Kangaroo Rat Country Following Summer Drought.

An area of the U. S. Range Reserve in the autumn of 1918, showing the result of failure of summer

rains. Such a condition is critical not only for the stockmen but also for kangaroo rats

and other desert rodents, and results in competition between them as to which shall benefit

by what the range has to offer.

Plate III. Fig. 1.—Kangaroo Rat Mound (Dipodomys s. spectabilis).

Typical Dipodomys s. spectabilis mound on the Range Reserve, under shelter of desert hackberry

(Celtis pallida). Most dens on the reserve are located in the shelter of brush plants,

the more important being mesquite (Prosopis velutina), cat's-claw (Acacia spp.), and the

desert hackberry. (See also Pl. VIII Fig. 2.)

Plate III. Fig. 2.—Kangaroo Rat Mound (Dipodomys deserti).

Den of Dipodomys deserti deserti, showing typical wide, low mound with numerous entrance

holes. This species excavates its den in soft, sandy soil. The tree is a species of Dalea.

DESCRIPTION.

GENERAL CHARACTERS.

Size large; ears moderate, ear from crown (taken in dry skin) 9

or 10 millimeters; eyes prominent; whiskers long and sensitive; fore

feet short and weak; hind feet long and powerful, provided with

four well-developed toes; tail very long, usually 30 to 40 per cent[6]

longer than the body. Cranium triangular, the occiput forming the

base and the point of the nose the apex of the triangle, much flattened,

auditory and particularly mastoid bullae conspicuously inflated.

COLOR.

General color above, brownish buffy, varying in some specimens

to lighter buffy tints, grizzled with black; oblique hip stripes white;

tail with dark-brown or blackish stripes above and below, running

into blackish about halfway between base and tip, and with two

lateral side stripes of white to a point about halfway back; tail

tipped with pure white for about 40 millimeters (Pl. I). Underparts

white, hairs white to bases, with some plumbeous and buffy

hairs about base of tail; fore legs and fore feet white all around;

hind legs like back, brown above, hairs with gray bases, becoming

blackish (fuscous-black or chætura-black) about ankles, hairs on

under side white to bases; hind feet white above, dark-brown or

blackish (near fuscous) below.

Color variations in a series of 12 specimens from the type locality

and points widely scattered through the range of spectabilis consist

in minor modifications of the degree of coloration, length of white

tip of tail, and length of white lateral tail stripes. In general the

color pattern and characters are remarkably uniform. Young specimens,

while exhibiting the color pattern and general color of adults,

are conspicuously less brown, and more grayish.

There appears to be little variation in color with season. In the

series at hand, most specimens taken during the fall, winter, and

spring are very slightly browner than those of summer, suggesting

that the fresh pelage following the fall molt is a little brighter than

is the pelage after being worn all winter and into the following

summer. But at most the difference is slight.

OIL GLAND.

Upon separating the hairs of the middle region of the back about

a third of the distance between the ears and the rump, one uncovers

a prominent gland, elliptical in outline, with long axis longitudinal

and about 9 millimeters in length. The gland presents a roughened

and granular appearance, and fewer hairs grow upon it than elsewhere

on the back. The hairs in the vicinity are frequently matted,

as if with a secretion. In worn stage of pelage the gland may be

visible from above without separating the hairs. Bailey has suggested

that this functions as an oil gland for dressing the fur, and

our observations bear out this view. Kangaroo rats kept in captivity

without earth or sand soon come to have a bedraggled appearance,

as if the pelage were moist. When supplied with fine,[7]

dusty sand, they soon recover their normal sleek appearance. Apparently

the former condition is due to an excess of oil, the latter

to the absorption of the excess in a dust bath. The oil is doubtless

an important adjunct to the preservation of the skin and hair amid

the dusty surroundings in which the animal lives.

MEASUREMENTS AND WEIGHTS.

External measurements include: Total length, from tip of nose

to tip of tail without hairs, measured before skinning; tail vertebræ,

length of tail from point in angle when tail is bent at right angles

to body to tip of tail without hairs; and hind foot, from heel to tip

of longest claw.

The following are measurements of a series from the U. S. Range

Reserve:

Average measurements of 30 adult specimens of both sexes:

Total length, 326.2 millimeters (349-310); tail vertebræ, 188.4 (208-180);

hind foot, 49.5 (51-47); the average weight of 29 adult specimens

of both sexes was 114.5 grams (131.9-98.0).

Averages for 17 adult females: Total length, 326.4 millimeters

(349-310); tail vertebræ, 188.8 (208-179); weight (16 individuals),

113.7 (131.9-98.0); excluding pregnant females, 13 individuals

averaged 112.9 grams (131.9-98.0).

Averages for 13 adult males: Total length, 326 millimeters (345-311);

tail vertebræ, 187.8 (202-168); weight, 116.8 grams (129-100).

There appears to be no significant difference in the measurements

and weights of males and females, with the possible exception of the

comparison of adult males and adult nonpregnant females.

OCCURRENCE.

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION.

Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis is found in southeastern Arizona,

in northwestern, central, and southern New Mexico, in extreme

western Texas, in northern Sonora, and in northern and

central Chihuahua (Fig. 1). A subspecies, D. s. cratodon Merriam,

has been described from Chicalote, Aguas Calientes, Mexico, the

geographic range of which lies in central Mexico in portions of the

States of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosi, and Aguas Calientes.

HABITAT.

In the Tucson region spectabilis is typically a resident of the Lower

Sonoran Zone. This is perhaps the principal zone inhabited over

its entire range, but the animal is often found in the Upper Sonoran

also, and in the Gallina Mountains of New Mexico Hollister found it[8]

invading the yellow pine Transition where the soil was dry and sandy

and the pine woods of open character. The same observer found it

common in grassy and weed-grown parks among the large junipers,

pinyons, and scattering yellow pines of the Bear Spring Mountains,

N. Mex. Bailey calls attention to the fact that the animal apparently

does not inhabit the lower half of the Lower Sonoran Zone, as it extends

neither into the Rio Grande Valley of Texas nor the Gila

Valley of Arizona. In extreme western Texas it is common at the

upper edge of the arid Lower Sonoran Zone, and in this region does

not enter the Upper Sonoran to any extent.

In July, 1914, Goldman found this kangaroo rat common on the

plain at 4,600 feet altitude, near Bonita, Graham County, Ariz., and

noted a few as high as 5,000 feet altitude on the warm southwestern

slopes of the Graham Mountains, near Fort Grant. Apparently

spectabilis reaches its upper altitude limit in the Burro Mountains,

N. Mex., where Bailey has found it sparingly on warm slopes up to

5,700 feet, and at the western base of the Sandia Mountains, east of

Albuquerque, N. Mex., where dens occur at approximately 6,000

feet.

About Tucson it is undoubtedly more common in the somewhat

higher portions of the Lower Sonoran Zone, above the Covillea association,

than elsewhere (Pl. IV, Figs. 1 and 2). A few scattered

dens are to be seen in the Covillea belt, but as one rises to altitudes

of 3,500 to 4,000 feet, and the Covillea is replaced by the cat's-claws

(Acacia sp. and Mimosa sp.) and scattered mesquite (Prosopis), with

the Opuntia becoming less abundant, kangaroo rat mounds come more

and more in evidence. Here is to be found the principal grass growth

supporting the grazing industry, and the presence of a more luxuriant

grass flora is probably an important factor in the greater abundance

of kangaroo rats, both spectabilis and merriami. In this generally

preferred environment the desert hackberry (Celtis pallida) is one of

the most conspicuous shrubs; clumps of this species are commonly

accompanied by kangaroo rat mounds.

In order to ascertain whether the banner-tailed kangaroo rat has

any marked preference for building its mounds under Celtis or some

other particular plant, all the observable mounds were counted in a

strip about 20 rods wide and approximately 4 miles long, an area

of approximately 160 acres, particular note being taken of the kind

of shrub under which each mound was located. Of 300 mounds in

this area, 96 were under Prosopis, 95 under Acacia, 65 under Celtis,

11 under Lycium, 31 in the open, 1 about a "cholla" cactus (Opuntia

spinosior), and 1 about a prickly pear (Opuntia sp.). There is apparently

no strongly marked preference for any single species of

plant. While both desert hackberry and the cat's-claws afford a better[9]

protection than mesquite—since cattle more often seek shade under

the latter, and in so doing frequently trample the mounds severely—it

appears that the general protection of a tree or shrub of some sort

is sought by kangaroo rats, rather than the specific protection of the

thickest or thorniest species.

The following records indicate particular habitat preferences of

spectabilis as noted at different points in its range:

Occurs on open bare knolls exposed to winds, also on gravelly places at

lower edge of foothills (Franklin Mountains, Tex., Gaut); here and there

over the barest and hardest of the gravelly mesas (Bailey, Tex., 1905, 147);

on open creosote-bush and giant-cactus desert (Tucson, Ariz., Vorhies and

Taylor); on firm, gravelly, or even rocky soil on the grassy bajada land along

the northwest base of the mountains, either in the open or under Celtis, Prosopis,

Lycium, Acacia greggii, or other brush (Santa Rita Mountains, Ariz.,

Vorhies and Taylor); mounds usually thrown up around a bunch of cactus or

mesquite brush (Magdalena, Sonora, Bailey); in heavy soil (Ajo, Ariz., A. B.

Howell); loamy soil (Gunsight, Ariz., A. B. Howell); in mesa where not too

stony (Magdalena, Sonora, Bailey); grassy plain (Gallego, Chihuahua, Nelson);

in open valley and high open plains (Santa Rosa, N. Mex., Bailey); in grassy

and weed-grown parks among the larger junipers, pinyons, and scattering

yellow pines (Bear Spring Mountains, N. Mex., Hollister); on sand-dune strip

(east side of Pecos River, 15 miles northeast of Roswell, N. Mex., Bailey);

among Ephedra patches (San Juan Valley, N. Mex., Birdseye); in open sandy

soil along dry wash (Rio Alamosa, N. Mex., Goldman); on sides and crests

of bare, stony hills (Mesa Jumanes, N. Mex., Gaut); in open, arid part of the

valley and stony mesas (Carlsbad and Pecos Valley, N. Mex., Bailey); about

the edges of the plains of San Augustine and the foothills of the Datil and

Gallina Mountains, and in the Transition Zone yellow-pine forest of the Gallina

Mountains (Datil region, N. Mex., Hollister); on hard limy ridges (Monahans,

Tex., Cary).

A. Brazier Howell notes that spectabilis occurs in harder soil than

does deserti. This observation is confirmed by others, and seems to

afford a conspicuous habitat difference between the two, for deserti

is typically an animal of the shifting aeolian sands.

Usually, as on the Range Reserve, the rodents are widely distributed

over a considerable area. Occasionally, as in the vicinity of Rio

Alamosa, N. Mex., as reported by Goldman, they occur only in small

colonies.

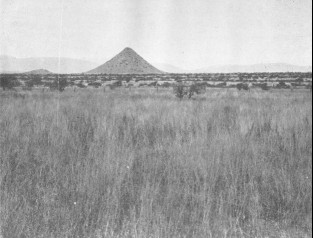

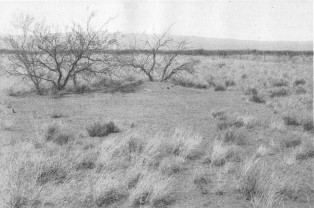

Plate IV. Fig. 1.—Range Conditions Favoring Kangaroo Rats.

View on higher portion of Range Reserve, showing type of country where Dipodomys s. spectabilis

is most abundant. Good growth of grama and needle grasses in October, following summer

growth and before grazing off by cattle and rodents.

Plate IV. Fig. 2.—Range Conditions Less Favorable to Kangaroo Rats.

View on lower portion of Range Reserve, where Dipodomys s. spectabilis is less abundant. Vegetation

consists principally of Lycium, mesquite, rabbit brush, and cactus, there being very

little grass.

HABITS.

EVIDENCE OF PRESENCE.

Mounds.

One traveling over territory thickly occupied by the banner-tailed

kangaroo rat is certain to note the numerous and conspicuous mounds

so characteristic of the species, particularly if the region is of the

savannah type, grassy rather than brushy. These low, rounded

mounds occupy an area of several feet in diameter, and rise to varying[10]

heights above the general surface of the surrounding soil, the

height depending rather more upon the character of the soil and the

location of the mound as to exposure or protection than upon the

area occupied by the burrow system which lies within and is the

reason for the mound.

A den in sandy soil in the open may be of maximum size in area

occupied and yet scarcely present the appearance of a mound in any

sense, due probably both to the fact that the sandy soil will not heap

up to such a height over a honeycomb of tunnels as will a firmer or

rocky soil, and also to its greater exposure to the leveling action of

rains and the trampling of animals. These mounds are in themselves

large enough to attract some attention, but their conspicuousness is

enhanced by the fact that they are more or less completely denuded

of vegetation and are the centers of cleared areas often as much as

30 feet in diameter (Pl. V, Fig. 1); and further that from 3 to 12

large dark openings loom up in every mound. The larger openings

are of such size as to suggest the presence of a much larger animal

than actually inhabits the mound. Add to the above the fact that

the traveler by day never sees the mound builder, and we have the

chief reasons why curiosity is so often aroused by these habitations.

On the Range Reserve the mounds are usually rendered conspicuous

by the absence of small vegetation, but Nelson writes that in the

vicinity of Gallego, Chihuahua, they can be readily distinguished at

a distance because of a growth of weeds and small bushes over their

summits, which overtop the grass. In the vicinity of Albuquerque,

N. Mex., Bailey reports (and this was recently confirmed by Vorhies)

that the mounds about the holes of spectabilis are often hardly

noticeable. Hollister writes that in the yellow-pine forests of the

Gallina Mountains the burrows are usually under the trunk of some

fallen pine, both sides of it in some cases being taken up with holes,

there being some eight or ten entrances along each side, the burrows

extending into the ground beneath the log. In the vicinity of

Blanco, N. Mex., Birdseye says that occasionally spectabilis makes

typical dens but more often lives in old prairie-dog holes (Cynomys),

or in holes which look more like those of D. ordii.

Runways and Tracks.

Still other features add to the interest in the dwelling places of

spectabilis. Radiating in various directions from some of the openings

of the mounds well-used runways are to be seen, some of them

fading out in the surrounding vegetation, but others extending 30,

40, or even 50 or more yards to neighboring burrows or mounds (Pl. V, Fig. 2;

Pl. VI, Fig. 1). These runways and the entrances to the

mounds are well worn, showing that the inhabitants are at home and[11]

are at some time of day very active. The worn paths become

most conspicuous in the autumnal harvest season, when they stand

out in strong contrast to surrounding grass. One usually finds not

far distant from the main habitation one or more smaller burrows,

each with from one to three typical openings, connected by the trail

or runway system with the central den, and these we have called

"subsidiary burrows" (Pl. VI, Fig. 2). These will be again

referred to in discussing the detailed plan of the entire shelter

system.

Examination of the runways and of the denuded area about a

mound discloses an abundance of almost indecipherable tracks. The

dust or sand is ordinarily much too dry and shifting to record clear

footprints, and there are no opportunities to see footprints of this

species recorded in good impressionable soil. Very characteristic

traces of kangaroo rats may be readily observed in the dust about the

mounds, however, and these are long, narrow, sometimes curving,

furrows made by the long tails as the animals whisk about their work

or play.

Plate V. Fig. 1.—Clearing About a Mound.

A typical clearing about a mound of Dipodomys s. spectabilis, showing the autumnal denudation

of the mound and surrounding areas. In this instance about 30 feet in diameter.

Plate V. Fig. 2.—Mound and Runways.

A small mound of Dipodomys s. spectabilis in early autumn, showing runways radiating from

the den. Evidences of activity may be noted in and about the surface of the mound.

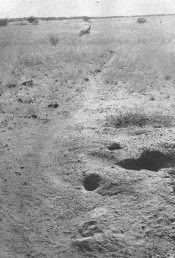

Plate VI. Fig. 1.—Runway of Dipodomys s. spectabilis.

Well-traveled path leading from the main den, in the foreground,

to a subsidiary burrow (see Fig. 2, below), about 30 feet distant,

at apparent end of runway.

Plate VI. Fig. 2.—Subsidiary Burrow of Dipodomys s. spectabilis.

Located at the end of the 30-foot runway shown in Figure 1, above. This has three openings, two

in the foreground and the third a little to the rear and indicated by an arrow.

Signals.

If a scratching or tapping sound be made at the mouth of a burrow,

even in the daytime, one is likely to hear a muffled tapping in

response, and this may at times be heard while one is engaged in

excavating a mound. It has a chirring or fluttering quality, described

by Fisher as resembling the noise of a quail flying. Bailey

(1905, 148) is of the opinion that it is used as a signal of alarm, call

note, or challenge, a view which the present authors believe to be correct.

During the winter of 1920-21, however, both Bailey and

Vorhies discovered that this sound, or a very similar one, is made

by the rapid action of the forefeet in digging. On one occasion

in the laboratory the sound was given by one of a pair and was

responded to at once by the other, the two being in separate but contiguous

cages. This observation, however, could not be repeated.

(Vorhies MS.)

One evening, while working in the vicinity of the Burro Mountains,

N. Mex., Goldman heard a kangaroo rat near camp making

this thumping noise. Taking a lantern, he approached the den, very

cautiously, until within 10 feet. The kangaroo rat was just outside

the entrance of one of its burrows, and though moving about more or

less restlessly at first showed little fear, and kept up the thumping

or drumming at intervals. When making the noise the animal was

standing with the forefeet on the ground and the tail lying extended.

The noise seemed to be made with the hind feet only, and the vibration

of the feet could be seen. The tapping was kept up for a second

or two at a time, the sounds coming close together and being repeated[12]

rhythmically after a very short interval, suggesting the distant galloping

of a horse. After continuing in this way for a short time, the

animal turned quickly about, with its head in the opposite direction,

and began tapping. It appeared to pay little attention to the light,

but finally gave a sudden bound and entered one of its holes about 4

feet from the one in front of which it had been standing.

Vorhies has repeatedly noted when watching for the appearance

of a kangaroo rat at night that this sound invariably precedes the

rodent's first emergence into the open, and often its appearance after

an alarm, though when the storage season has begun and the kangaroo

rat is carrying loads of grass heads or other material into its den,

it regularly comes out without preliminary signaling. Vorhies has

also observed it making the sound while on top of the mound, and

certainly not digging, but was unable to see how it was made.

Voice.

No data concerning any call notes or sounds other than those described

above are at hand, with the following exception: Price (in

Allen, 1895, 213), who studied the habits of the animal in the moonlight,

at Willcox, Ariz., says that a low chuckle was uttered at intervals;

and Vorhies has had one captive female that would repeatedly

utter a similar chuckle in a peevish manner when disturbed by day,

and one captive male which, when teased into a state of anger and

excitement, would squeal much like a cornered house rat. Vorhies

has spent many moonlight hours observing kangaroo rats, but without

ever hearing a vocal sound uttered by free individuals.

DAILY AND SEASONAL ACTIVITY.

The kangaroo rat is strictly nocturnal. An observer watching

patiently by a den in the evening for the animal's first appearance

is not rewarded until darkness has fallen completely, and unless the

moon is shining the animal can hardly be seen. Were it not for the

white tail-brush of spectabilis and its white belly when upright on

the hind legs and tail, one could not as a rule see the animal at all

when it makes its first evening appearance. With the first streak of

dawn activity usually ceases completely and much more abruptly

than it began with the coming of darkness, but on a recent occasion

Vorhies observed that a kangaroo rat which did not appear until

near morning remained above ground until quite light, but not fully

daylight. On removal of the plug from the mouth of a kangaroo rat

burrow, one may sometimes see a fresh mass of earth and refuse shoved

into the opening from within. As often as not, however, even this

unwelcome attention does not elicit any response by day, the great

majority of the burrow openings of this species, as observed by the

authors, remaining permanently open.

[13]The ordinary activities of the kangaroo rat in southern Arizona

can scarcely be said to show any true seasonal variation. The animals

are active all the year in this region, there being neither hibernation

nor estivation, both perhaps being rendered unnecessary by

the storage habit, to be discussed in full later (pp. 15-16), and by the

mildness of the winter climate. On any particular night that the

weather is rainy, or the ground too wet and cold, activity is confined

to the interior of the burrow system, and for this reason one has no

opportunity to see a perfect imprint of the foot in freshly wet soil or

in snow. On two or three of the comparatively rare occasions on

which there was a light fall of snow on the Range Reserve a search was

made for tracks in the snow. At these times, however, as on rainy

nights, the only signs of activity were the pushing or throwing out

of fresh earth and food refuse from within the burrow. This is so

common a sight as to be complete evidence that the animals are

active within their dens during stormy weather but do not venture

outside. Trapping has again and again proved to be useless on rainy

nights, unless the rain is scant and a part of the night favorable, in

which case occasional individuals are taken. These statements apply

to the Range Reserve particularly; the facts may be quite different

where the animals experience more winter, as at Albuquerque,

N. Mex., although in November, 1921, Vorhies noted no indications

of lessened activity in that region.

PUGNACITY AND SOCIABILITY.

So far as their reactions toward man are concerned, kangaroo

rats are gentle and make confiding and interesting pets; this is

especially the case with merriami. This characteristic is the more

surprising in view of the fact that they will fight each other so

readily and so viciously, and yet probably it is explained in part by

their method of fighting. They do not appear to use their teeth

toward each other, but fight by leaping in the air and striking with

the powerful hind feet, reminding one most forcibly of a pair of

game cocks, facing each other and guarding in the same manner.

Sometimes they carry on a sparring match with their fore feet.

Biting, if done at all, is only a secondary means of combat. When

taken in hand, even for the first time, they will use their teeth only

in the event that they are wounded. The jaws are not powerful, and

though the animals may lay hold of a bare finger, with the apparent

intention of biting, usually they do not succeed in drawing blood.

As Bailey says (1905, 148), they are gentle and timid, and, like rabbits,

depend upon flight and their burrows for protection.

The well-traveled trails elsewhere described (p. 10) indicate a degree

of sociability difficult to explain in connection with their pugnacity[14]

toward each other. While three or four individuals may

sometimes be trapped at a single mound, more than two are seldom

so caught, and most often only one in one night. Trapping on successive

nights at one mound often yields the larger number, yet in

some cases the number is explained by the fact that two or three

nearly mature young are taken, and the capture of several individuals

at a single mound can not be taken to indicate that all are from

the one den. Our investigations tend strongly to the conclusion that

only one adult occupies a mound, except during the period when the

young are in the parental (or maternal) den. In the gassing and

excavating of 25 or more mounds we have never found more than one

animal in a den, except in one instance, and then the two present

were obviously young animals.

SENSE DEVELOPMENTS.

Without making special investigations through a study of behavior

or other special methods, one can speak in only general terms regarding

what appear to be the special sense developments of kangaroo

rats. The eyes are large, as is very often the case in nocturnal animals,

and when brought out into the bright light of day the rats

perhaps do not see well. Yet, if an animal leaves a den which is in

process of excavation, and follows one runway, even in bright sunlight,

it makes excellent speed to the next opening, often a distance of

several yards. Whether this is accomplished chiefly by the aid of

sight or in large measure by a maze-following ability, such as experiments

have shown some rodents to have, can not be stated without

precise experimentation. Marked ability to follow a maze would

not be at all surprising in view of the labyrinthine character of the

underground passages which make up the normal habitation.

When watching beside a mound by moonlight one is impressed with

the fact that the rats possess either a very keen sense of hearing or

of sight, probably both. The very slightest movement or noise on

the part of the observer results, with a timid individual, in an instantaneous

leap for safety, a disappearance into the burrow so

sudden as to be almost startling. All attempts to obtain flashlight

photographs at the mounds were failures, the animal either having

gotten completely out of the field before the light flashed following

the pull of the trigger, or leaving merely an indistinguishable blur

on the plate as it went, and this in spite of carefully hiding the trigger

chain behind a screen. A slight noise accompanying the trigger

action gave the alarm in one case, and in another the length of time

of the flash was sufficient for the get-away. The marvelous quickness

of the animal clearly indicates a remarkably short reaction time.[15]

Occasionally a bold individual is found, as in the case of one which

came out repeatedly, even after being flashed twice in the same night.

Certain peculiar physical characteristics suggest a relationship to

sense reactions. On these, however, the authors are not prepared to do

more than offer suggestions for future work. The extremely large

mastoids found in kangaroo rats suggest a connection in some way

with special developments of the sense of hearing or of balance. It

may be noted that an intermediate condition between the kangaroo

rats and the majority of rodents in respect to this character is to

be found in the pocket mice (Perognathus), which belong to the

same family. Herein lies a field for some interesting experimentation

and discovery.

The small, pointed nose might suggest a not overkeen sense of

smell, and there appears no reason to believe that this sense is particularly

well developed. However, the turbinals are very complex.

The vibrissæ are long and sensitive, and may indicate a special development

of the sense of touch as an adaptation to nocturnal habits

and to life in an underground labyrinth. The long, well-haired tail

doubtless serves as an important tactile organ as well as a balance.

MOVEMENTS AND ATTITUDES.

Movements and attitudes are characteristic. As a kangaroo rat

emerges from the burrow a reason for the relatively large size of the

opening is seen in the fact that, kangaroolike, the animal maintains

a partially upright position. Its ordinary mode of progression is

hopping along on the large hind legs, or, when in the open and going

at speed, leaping. When moving slowly about over the mound, as

if searching for food, it uses the fore legs in a kind of creeping movement.

It appears to be creeping when pocketing grain strewn about,

but close observation shows that the fore feet are then used for sweeping

material into the pockets, reminding one somewhat of a vacuum

cleaner. When it assumes a partially upright position the fore limbs

are usually drawn up so closely that they can be seen only by looking

upward from a somewhat lower level than that occupied by the

animal. The slower movements of searching or playing about the

mound are occasionally interrupted by a sudden leap directly upward

to a height of 1-1/2 to 2 feet, often with no apparent reason other than

play. This is, however, a fighting or guarding movement, though

indulged in for play. The play instinct seems to be well developed,

and in evidence on any moonlight night when actual harvesting operations

are not going on.

STORING HABITS.

Probably no instinct is of greater importance to the kangaroo rat

than that of storing food supplies. When a crop of desirable seeds[16]

is maturing the animal's activities appear to be concentrated on this

work. During September, 1919, when a good crop of grass seed was

ripening following the summer rains, a kangaroo rat under observation

made repeated round trips to the harvest field of grass heads.

Each outward trip occupied from 1 to 1-1/2 minutes, while the unloading

trip into the burrow took only 15 to 20 seconds.

One individual in a laboratory cage, which had not yet been given

a nest box, busied itself in broad daylight in carrying its grain supply

into the darkest corner of the cage. When a nest box is supplied the

individual will retreat into its dark shelter, and will only come forth

after darkness has fallen unless forcibly ejected, but will store the

food supplied.

In another case an animal escaped while being handled, and sought

refuge behind a built-in laboratory table, where it could not be recovered

without tearing out the table. For four days and nights it

had the run of the laboratory. On the first night of its freedom it

found and entered a burlap bag of grass seed that had been taken

from a mound. A trail of seed and chaff next morning showed that

it had been busily engaged in making its new quarters comfortable

with bedding and food. After four nights of freedom it was captured

alive in a trap, and later it was found that it had moved from

the corner behind the table to the space beneath a near-by drawer,

where it had stored about 2 quarts of the grass seed and a handful of

the oatmeal used for trap bait.

BREEDING HABITS.

Observations on breeding habits have consisted mainly in taking

records from the females trapped at all seasons of the year throughout

the course of the investigation, and from examinations made during

poisoning operations, and yet from this source the number of

pregnant females taken or of young discovered is disappointingly

small. The records indicate a breeding period of considerable length,

extending from January to August, inclusive. It is possible that the

length of the period may be increased by a second litter from the

earliest breeding females in summer, but the large percentage of

nonpregnant or nonbreeding animals which occurs throughout the

season would indicate a wide variation in the time of breeding of

different individuals.

Trapping in February and March for the purpose of securing

greater numbers of female specimens, begun with the idea that these

months were most likely to be the breeding months, has invariably

yielded an unsatisfactory number of nonbreeding specimens and

males. Unfortunately, the numbers of females secured in some

months were not sufficient to be significant if worked out in percentages[17]

of breeding and nonbreeding individuals, and this, coupled

with the fact that the importance of recording carefully all nonbreeders

was not at first recognized, makes it impossible to tabulate

such information reliably. The total of females taken in April, for

example, is only 3, of which 1 was breeding; while in June, during

the course of poisoning operations, 45 females were examined, of

which 21 were breeding.

Five breeding females were taken in January, all during the last

three days of the month. One of these was a suckling female, the

young of which were secured alive and were probably at least a week

old when taken. This must have been exceptionally early for young,

since of a number of adult kangaroo rats taken during the first week

of January none have been found to be breeding. Two records from

Vernon Bailey are as follows: May 19-June 8, 1903, young specimen

in nest (Santa Rosa, N. Mex.); June 12, 1889, one female, two embryos

(Oracle, Ariz.).

The considerable proportion (which we believe to be more than 50

per cent) of nonbreeding females taken during all those months in

which breeding has been found to occur may also indicate an extended

period of breeding, with a small percentage breeding at any

one time. This period also furnishes ample time for the rearing of

two litters a year by some females, but we have no evidence as to the

occurrence of two litters. Young of the year, practically grown, are

taken during and after the month of April.

The mammae are arranged in three pairs, pectoral, 1/1; inguinal, 2/2.

Kangaroo rats are among those rodents in which the vagina becomes

plugged with a rather solid material, translucent, and of the

consistency of a stiff gelatine, after copulation. This must occur

very soon after coitus, since in those individuals taken in this condition

no definite evidence of the beginning of development of embryos

could be detected by examination.

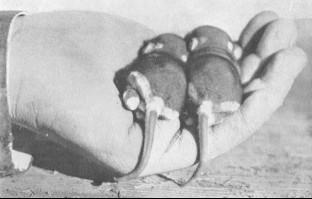

The length of the gestation period of spectabilis is unknown. The

young are born naked, a fact inferred by failure to find any fetus

showing noticeable hair development, and from the conditions observed

in such young as have been seen. A suckling female was

taken by Vorhies, January 31, 1920, and her den immediately excavated

in the hope of securing the young. Two juveniles were found

in a special nest chamber (see p. 30). These were estimated to be

perhaps two weeks old. A serious effort was made to raise the little

animals by feeding milk with a pipette and keeping them warm with

a hot water bottle, but they survived only 10 days, without the eyes

having opened. The uneven temperature as well as the character of

the food was probably responsible for their deaths. On February 3

they were measured and weighed, with the following results:

[18]

| Weight (in grams). | Measurements (in millimetres). | |||

| Total length. | Tail vertebrae. | Hind foot. | ||

| No. 1 | 13.3 | 90 | 38 | 24 |

| No. 2 | 12.6 | 93 | 38 | 24 |

At this stage the young were partially clothed with a coat of fine

velvety fur, more especially on the bodies, the tails being still nearly

naked. The body color was dark plumbeous, just the color of the

dark underfur of the adult, or a shade darker, while the characteristic

white markings of the adult stood out sharply as pinkish-white

areas against the dark background (see Pl. IX, Fig. 2, at

p. 32). The proportions were much as in the adult, except that

the tails were relatively much shorter and the feet relatively longer.

Only one other record of young is at hand, that by Bailey, who

secured the young after capture of a suckling female at Santa Rosa,

N. Mex. In this case the litter contained only one. This was squeaking

when found, but was not large enough to crawl away. Its eyes

and ears were closed, and its soft, naked skin was distinctly marked

with the pattern of the adult, the colors being as given for the other

two. This juvenile lived only a week. Young less than half grown were

not trapped or noted in our poisoning operations outside the dens.

Kangaroo rats, if spectabilis be representative, reproduce at a

slow rate as compared with many other small rodents. We have

records of 67 females with embryos or scars showing the number

produced, and of the two litters of young described above. Of the

69 females thus recorded, 15, or 21.7 per cent, had but one offspring

each; 52, or 75.3 per cent, but two each; while only 2 individuals,

or 2.9 per cent, had three. Three young is the maximum litter recorded.

This, taken in connection with the protracted breeding season

and lack of sure evidence of the production of two broods a year,

gives a surprisingly low rate of reproduction, indicating relative

freedom from inimical factors.

Our breeding records for merriami are fewer than for spectabilis,

but are very similar in every way so far as they go, both as to the

time of year and number of young.

FOOD AND STORAGE.

Dipodomys s. spectabilis does not hibernate, so must prepare for

unfavorable seasons by extensive storage of food materials. There

are two seasons of the year, in southeastern Arizona at least, when

storage of food takes place, namely, in spring, during April or May,

and in fall, from September to November, the latter being the more

important. For the periods between, the animal must rely largely[19]

on stored materials. Not infrequently a season of severe drought precludes

the possibility of any storage. The summer and fall of 1918

was such a season on the Range Reserve (Pl. II, Fig. 2). If food

stores are inadequate at such a time the kangaroo rats must perish

in considerable numbers. Fisher found many deserted mounds in

the vicinity of Dos Cabezos, Ariz., in June, 1894, which may be

accounted for in this way. In 1921 Vorhies found all mounds within

4 or 5 miles of Albuquerque, N. Mex., deserted by spectabilis, resulting

probably from overgrazing by sheep and goats during a succession

of dry years. In the arid Southwest natural selection probably

favors the animals with the largest food stores, and it is not surprising

that the storing habit has been developed to a remarkable degree.

Some stored material is likely to be found at any time of year in

any mound examined, the largest quantity usually in fall and winter,

the smallest in July or August (Table 1, dens 1, 2, 14, and 24).

Amounts found by different observers vary from a few ounces to

several quarts or pecks, and stored materials taken from 22 mounds

on the Range Reserve vary in weight from 5 to 4,127 grams

(more than 9 pounds). This is exceeded by one lot from New

Mexico, which totaled 5,750 grams (12.67 pounds). It is fairly

evident that in seasons of scanty forage for stock the appropriation

of such quantities of grass seeds and crowns and other grazing materials

by numerous kangaroo rats may appreciably reduce the carrying

capacity of the range. Studies of cheek-pouch contents and food

stores taken from dens show that the natural food of spectabilis

consists principally of various seeds and fruits, particularly the seeds

of certain grasses. The study of burrow contents has been especially

illuminating and valuable.

All of the stored material from 22 dens on the Range Reserve

and from 2 near Albuquerque, N. Mex., has been saved and analyzed

as to species as carefully as the conditions of storage would

permit. Within the mound the food stored is usually more or less

segregated by plant species, though the stores of material of any

one kind may be found in several places through the mound, and

often the material is mixed. In the latter case the quantities of

the various species can only be estimated, but in the former the

species may be kept separate by the use of several bags for

collecting the seeds, and a fairly accurate laboratory weighing can

be made later. Very frequently, the explanation of this separation

of species lies in the different seasons of ripening, but sometimes

where two species are ripe at the same time near the mound, one

is worked upon for a time to the exclusion of the other. The one

kind is often packed in tightly against the other, but with a very

abrupt change in the character of the material.

[20]A number of the more interesting and representative results of

the weighing and analyses of burrow contents are presented herewith

in tabular form. The data for each den, or lot, shows in grams

the quantity of stored material removed and the best estimate it was

possible to make of the percentages or weights of the various species.

When the weight was less than 5 grams, the mere trace of the species

frequently is indicated in the following tables by the abbreviation

"Tr."

Table 1.—Analyses of plants stored by Dipodomys spectabilis spectabilis Merriam,

obtained from examination of representative dens (all except Den 24

from U. S. Range Reserve, near the Santa Rita Mountains, Ariz.).

Den 1.

February 7, 1918. Burrow typical, located on bank of wash in partially

denuded grass-land, Bouteloua rothrockii and weed type; soil sandy; burrow

photographed in section (Pl. VII, Fig. 1).

| Species stored. | Grams. |

| Bouteloua rothrockii | 2,205 |

| Bouteloua aristidoides (B. eriopoda and B. rothrockii, Tr.) | 1,445 |

| Plantago ignota | 442 |

| Eriogonum polycladon | 35 |

| Total | 4,127 |

Four species of plants represented in burrow contents (Pl. VII, Fig. 2).

Maximum quantity for single burrow in series of 22 from Range Reserve.

Den 2.

March 9, 1918. Surroundings overgrazed and partially restored by complete

protection. Red soil, with much coarse rough gravel and stone.

| Species stored. | Grams. | |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (nearly pure) | 1,460 | |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (mixed with Aristida spp.) | 945 | |

| Boerhaavia wrightii | 660 | |

| Bouteloua rothrockii | } | 525 |

| Bouteloua aristidoides | ||

| Aristida divaricata | ||

| Aristida bromoides | ||

| Kallstroemia laetevirens | Tr. | |

| Heterotheca subaxillaris | Tr. | |

| Plantago ignota | 15 | |

| Fleshy fungi | 10 | |

| Total | 3,615 |

Eight species of plants represented by seeds. One species of fleshy fungus

in addition.

[21]

Den 4.

September 20, 1918. In Calliandra type. Stony or gravelly soil, red, nearly

denuded of grass.

| Species stored. | Grams. | ||

| Prosopis velutina | 190 | ||

| Mollugo verticillata (pure) | 90 | ||

| Anisolotus trispermus (mixed, but mostly of this genus) | 50 | ||

| Solanum elaeagnifolium (12 fruits) | 2 | ||

| Per cent. | |||

| Mollugo verticillata (inseparable) | 50 | } | 400 |

| Bouteloua rothrockii | 1 | ||

| Bouteloua aristidoides | 10 | ||

| Lepidium lasiocarpum | Tr. | ||

| Polygala puberula | Tr. | ||

| Ayenia microphylla | 2 | ||

| Portulaca suffrutescens | 1 | ||

| Aplopappus gracilis | Tr. | ||

| Alternanthera repens | 1 | ||

| Tridens pulchella | 1 | ||

| Plantago ignota | 33 | ||

| Panicum hallii | Tr. | ||

| Fleshy fungi (puffballs) | 2 | ||

| Total | 734 |

Fifteen species represented in addition to the fleshy fungi. No perceptible

grass growth from the summer rains here, therefore dependent on a wide variety

of scattering plants.

Den 6.

October 17, 1918. Mixed type, partially denuded, no growth from summer

rains. Sandy soil.

| Species stored. | Grams. |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (crowns) (heads 1 to 2 per cent) | 1,435 |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (heads and crowns, about 50 per cent of each) | 325 |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (with small percentage of crowns) | 315 |

| Boerhaavia wrightii (with a few grass crowns) | 150 |

| Prosopis velutina | 90 |

| Solanum elaeagnifolium (3 fruits) | Tr. |

| Total | 2,315 |

Four species represented. Count of 100 grams of stored Bouteloua crowns

gives 1,700, or 17 crowns per gram. At this rate there were at least 27,000

crowns stored in this burrow. If a density of 250 plants to the square yard be

assumed (a high estimate) these crowns represent the total B. rothrockii on 104

square yards of range surface. Further examination of the vicinity of this den

showed that the surrounding area was not completely cleared, but was devoid of

B. rothrockii, while still having B. eriopoda with crowns undisturbed.

Den 11.

April 9, 1919. In partially denuded land where good spring growth of

Eschscholtzia was in bloom at time of excavation. Stomach of spectabilis killed[22]

in this burrow contained a mass of fresh but finely comminuted green material,

probably poppy leaves, strongly colored with yellow from blossoms. No summer

growth here in 1918.

| Species stored. | Grams. | |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (crowns) (miscellaneous chaff, etc.) | 107 | |

| Eschscholtzia mexicana (buds and flowers) | } | 10 |

| Anisolotus trispermus (leaves and pods) | ||

| Gaertneria tenuifolia (leaves) | ||

| Lupinus sparsiflorus (flowers) | ||

| Solanum elaeagnifolium (2 fruits) | Tr. | |

| Total | 117 |

Six species represented, some only by leaves or flowers and not by seeds.

Such storage is never in large quantity. The fresh storage material was

weighed after becoming air dry. This illustrates a late spring condition, storage

running low.

Den 14.

August 8, 1919. Excellent summer growth all over range. This burrow in

mixed growth, grasses and weeds.

| Species stored. | Grams. |

| Miscellaneous portions of green plants of mixed species, no seeds | 5 |

Representing minimum for any one of the 22 burrows studied. Active storage

does not begin until September.

Den 16.

October 17, 1919. In good grass, but mound overrun by a large Apodanthera

vine.

| Species stored. | Per cent. | Grams. | |

| Aristida divaricata | 90 to 95 | } | 58 |

| Chamaecrista leptadenia | 10 to 5 | ||

| Bouteloua rothrockii | Tr. | ||

| Prosopis velutina | 200 | ||

| Apodanthera undulata | 55 | ||

| Total | 313 |

Five species represented. Two species, Apodanthera, and Chamaecrista leptadenia,

new to storage records. Several whole fruits of Apodanthera, about 2

inches in diameter, stored in addition to seeds alone; seeds of this form not

previously noted in burrows, but very abundant in this one, indicating importance

of the factor of accessibility in storage.

Den 19.

October 31, November 1, 1919. In good grass. Entire burrow system mapped

(Fig. 2, p. 29).

| Species stored. | Per cent. | Grams. | |

| Aristida spp. (probably mostly divaricata) | 98 | } | 1,813 |

| Eriogonum sp | Tr. | ||

| Bouteloua rothrockii | 1 | ||

| Bouteloua aristidoides | 1 | ||

| Panicum sp | Tr. | ||

| Prosopis velutina | 1,213 | ||

| Total | 3,026 |

[23]Five species represented, in addition to those of Aristida. Largest storage

of Prosopis found. Mound was near a good-sized mesquite tree. No storage in

subsidiary burrows.

Den 21.

January 31, 1920. Male trapped here night of January 29, and suckling female

trapped at same place and same opening of mound, night of January 30.

Burrow excavated to secure young, which were found in special nest chamber.

| Species stored. | Grams. |

| Aristida spp. (intimate mixture of undetermined species) | 1,115 |

| Eschscholtzia mexicana (from spring of 1919) | 48 |

| Opuntia (prickly pear, seeds only, no fruits) | 10 |

| Total | 1,173 |

Three species represented. Prickly pear hitherto found as fruits only.

Den 22.

January 1, 1921. Rather good grass growth here in summer of 1920. Burrow

typical, sandy soil. Two skulls of former residents unearthed.

| Species stored. | Grams. |

| Aplopappus gracilis (some B. rothrockii) | 1,030 |

| Astragalus nuttallianus | 630 |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (some A. gracilis) | 530 |

| Sida diffusa | 30 |

| Solanum elaeagnifolium (282 fruits) | 53 |

| Loeflingia pusilla | Tr. |

| Bouteloua aristidoides | Tr. |

| Plantago ignota | Tr. |

| Lupinus sparsiflorus | Tr. |

| Old storage (mostly Bouteloua aristidoides with traces of B. rothrockii and Aristida divaricata) | 60 |

| Total | 2,333 |

Eleven species represented. First instance of quantity storage of Aplopappus

gracilis. First occurrence of Loeflingia pusilla and Astragalus nuttallianus.

Den 24.

November 8, 1921. On mesa northeast of Albuquerque, N. Mex., near base

of Sandia Mountains. Fair grass growth here during preceding summer.

| Species stored. | Grams. |

| Sporobolus cryptandrus strictus | 5,455 |

| Salsola pestifer | 295 |

| Total | 5,750 |

Two species represented. The heads of Sporobolus cryptandrus strictus are

retained to a great extent within the leaf sheaths. This necessitates the cutting

of the stems into suitable lengths for carrying, and the stored material appears to

be merely cut sections of the stems. Close examination, however, discloses the

heads within, and shows that as in other instances seed storage is the end

sought. These pieces are packed beautifully parallel like so many matches,[24]

and vary from a minimum length of 20 to a maximum of 37 millimeters, averaging

about 30. Count of 2 grams of the above Sporobolus material shows

that there are 125 separate cut sections per gram, or a total of approximately

680,000 pieces in this one lot of storage, indicating a remarkable activity on

the part of the individual rat (Pl. VIII, Fig. 1).

Plate VII. Fig. 1.—Den Excavated on Range Reserve.

Vertical section through Den No. 1, of Table 1 (p. 20), showing the complex system of burrows,

some of them plugged with closely packed storage (outlined in white), the depth of the

den, and the widened chambers centrally located.

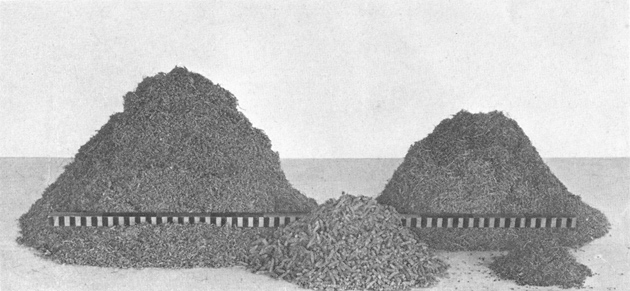

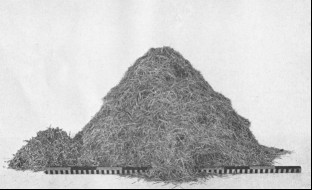

Plate VII. Fig. 2.—Content of Excavated Den.

Storage content of Den No. 1 (Fig. 1, above), showing the separate species of plants listed in

Table 1. The rod is 1 meter long. The large pile on the left is composed of seed-laden

heads of crowfoot grama (Bouteloua rothrockii), the large pile on the right consists of heads of

six-weeks grama (Bouteloua aristidoides), the pile of heads in the center is desert plantain

(Plantago ignota), and the smallest heap is composed of buckwheat-bush seeds (Eriogonum

polycladon).

The number of lots of storage (24) studied in detail, extending

as it does over a period of three years with seasons of varying growth

conditions, is not sufficient to permit the construction of a curve

showing increase and decrease in quantity of stored material with

growing seasons and intervals between; but the results indicate a

very decided increase during the autumn storing season, and continuing

large well into the winter, since some outside material can

still be obtained until midwinter. From about February to April a

decrease may be noted, followed, if the spring growth of annuals be

good, by a slight increase; and we can very nearly predict the general

character of the increases and decreases by the precipitation and

consequent growth conditions.

Table 2.—Quantity of storage per den correlated with time of year and growth

conditions of preceding season (chiefly from United States Range Reserve

near the Santa Rita Mountains, Ariz.).

| Den No. | Date. | Quantity. | Preceding season. |

| 1918. | Grams. | ||

| 1 | Feb. 7 | 4,127 | Good. |

| 2 | Mar. 9 | 3,615 | Do. |

| 3 | July 25 | 401 | Poor. |

| 4 | Sept. 20 | 734 | Do. |

| 5 | Sept. 21 | 2,520 | Do. |

| 6 | Oct. 17 | 2,315 | Do. |

| 7 | Dec. 20 | 1,247 | Do. |

| 1919. | |||

| 8 | Feb. 7 | 1,600 | Do. |

| 9 | Mar. 13 | 370 | Do. |

| 10 | Apr. 7 | 180 | Do.[3] |

| 11 | Apr. 9 | 117 | Good.[3] |

| 12 | May 7 | 298 | Do.[3] |

| 13 | May 11 | 1,590 | Do. |

| 14 | Aug. 8 | 5 | Good. |

| 15 | Sept. 4 | 151 | Do. |

| 16 | Oct. 17 | 313 | Do. |

| 17 | Oct. 18 | 583 | Do. |

| 18 | Oct. 25 | 3,410 | Do. |

| 19 | Nov. 1 | 3,026 | Do. |

| 20 | Dec. 13 | 2,816 | Do. |

| 1920. | |||

| 21 | Jan. 31 | 1,173 | Do. |

| 1921. | |||

| 22 | Jan. 1 | 2,333 | Fair. |

| 23[4] | Nov. 7 | 1,685 | Good. |

| 24[4] | Nov. 8 | 5,750 | Do. |

In presenting Table 2, showing quantity of storage per burrow correlated

with the time of year and the character of the preceding

growing season, the fact may be emphasized that the growing seasons

in southern Arizona are two in number—early spring and midsummer.

The spring season is the less important, the plants consisting

chiefly of a variety of small annuals, while the important range

grasses make their chief growth and head out almost exclusively in

the July-August rainy season. It may be noted also that the actual[25]

increases in storage appear somewhat after the growth period proper,

since storing does not get well under way until the seed crop is

mature. The banner-tailed kangaroo rat shows a marked adaptability

to different foods available in the neighborhood of its burrows.

It must, perforce, adapt itself and its storage program to the

food that it can get, and this varies enormously with the climatic

conditions of successive seasons. The large numbers present in suitable

localities clearly indicate that the animal is successful in meeting

the changing and sometimes extremely adverse conditions of its

environment.

Plate VIII. Fig. 1.—Content of Den Excavated in New Mexico.

Storage content of Den No. 24, of Table 1, from Sandia Mountains, N. Mex. This is the largest

lot of storage taken in the course of the investigations. The larger pile consists wholly of a

valuable grass, Sporobolus cryptandrus strictus: the smaller of Russian thistle (Salsola pestifer.)

Plate VIII. Fig. 2.—Growth Following Elimination of Kangaroo Rats.

The same mound as shown in Plate III, Figure 1, after three years of protection, the rodents

having been killed out. Nearly as good grass recovery following poisoning operations occurred

in the single excellent season of 1921.

At times, more especially in the seasons of active growth, some of

the green and succulent portions of plants are eaten. This was very

noticeable in the spring of 1919, when a most luxuriant growth of

Mexican poppy (Eschscholtzia mexicana) occurred. Stomachs at this

time were filled with the yellow and green mixture undoubtedly produced

by the grinding up of the buds and flowers of this plant.

Small caches of about a tablespoonful of these buds were also found

in the burrows at this time. Occasionally in spring one may find a

few green leaves of various plants, Gaertneria very commonly,

tucked away in small pockets along the underground tunnels, indicating

that such materials are used to some extent. As has been

shown in detail, however (Table 1), the chief storage, and undoubtedly

the chief food, consists of air-dry seeds.

The character of the storage, the absence of rain for months at a

time in some years, and the consequent failure of green succulents

show that without doubt spectabilis possesses remarkable power, as

to its water requirements, of existing largely if not wholly upon the

water derived from air-dry starchy foods, i.e., metabolic water serves

it in lieu of drink (Nelson, 1918, 400), this being formed in considerable

quantities by oxidation of carbohydrates and fats (Babcock,

1912, 159, 170). During the long dry periods characteristic

of southern Arizona, no evidence that the animal seeks a supply of

succulent food, as cactus, is found; and if it may go for two, three,

or six months without water or succulent food, it is reasonable to

suppose that it may do so indefinitely. In the laboratory spectabilis

ordinarily does not drink, but rather shows a dislike for getting its

nose wet. During the periods of drought the attacks upon the

cactuses by other rodents of the same region, as Lepus, Sylvilagus,

Neotoma, and Ammospermophilus, become increasingly evident.

The list of plant species thus far found represented in the storage

materials of spectabilis on the Range Reserve is shown in Table 3.

[26]

Table 3.—List of all plant species found in 22 dens of Dipodomys spectabilis

on the United States Range Reserve, near the Santa Rita Mountains, Ariz.,

with approximate total weights.

| Grasses. | |

| Grams. | |

| Aristida bromoides (six-weeks needlegrass) | 536 |

| Aristida divaricata (Humboldt needlegrass) | 9,412 |

| Aristida scabra (rough needlegrass) | 344 |

| Bouteloua aristidoides (six-weeks grama) | 3,093 |

| Bouteloua radicosa (grama) | 1,269 |

| Bouteloua eriopoda (black grama) | Tr. |

| Bouteloua rothrockii (seeds, 8,495; crowns, 3,517 grams) (crowfoot grama) | 12,012 |

| Festuca octoflora (fescue grass) | 70 |

| Panicum arizonicum (Arizona panic-grass) | 11 |

| Panicum hallii (Hall panic-grass) | Tr. |

| Pappaphorum wrightii | Tr. |

| Tridens pulchella | Tr. |

| Valota saccharata | Tr. |

| Other Plants. | |

| Alternanthera repens | Tr. |

| Anisolotus trispermus (bird's-foot trefoil) | 186 |

| Aplopappus gracilis | 1,030 |

| Apodanthera undulata (melon loco) | 55 |

| Astragalus nuttallianus (milk vetch) | 630 |

| Ayenia microphylla | Tr. |

| Boerhaavia wrightii | 885 |

| Chamaecrista leptadenia (partridge pea) | 5 |

| Echinocactus wislizeni (visnaga) | 5 |

| Eriogonum polycladon | 35 |

| Eschscholtzia mexicana (Mexican poppy) | 250 |

| Gaertneria tenuifolia (franseria) | Tr. |

| Collomia gracilis (false gilia) | Tr. |

| Heterotheca subaxillaris | Tr. |

| Kallstroemia laetevirens | Tr. |

| Lupinus sparsiflorus (lupine) | Tr. |

| Martynia altheaefolia (small devil's-horns) | 12 |

| Mollugo verticillata (carpetweed) | 324 |

| Oenothera primiverus (evening primrose) | 15 |

| Opuntia discata (prickly pear) | 15 |

| Loeflingia pusilla | Tr. |

| Lepidium lasiocarpum (peppergrass) | Tr. |

| Plantago ignota (plantain) | 818 |

| Polygala puberula (milkwort) | Tr. |

| Portulaca suffrutescens (purslane) | Tr. |

| Prosopis velutina (mesquite) | 1,570 |

| Sida diffusa (spreading sida) | 30 |

| Solanum elaeagnifolium (742 fruits) (trompillo, prickly solanum) | 156 |

| Puffballs and fleshy fungi (undetermined) | 12 |

Total species, exclusive of fungi, 41.

[27]It will be seen from Table 3 that while a large number of

species of plants are represented in the totals from so many dens,

a majority of them are of very minor importance, and that the

seeds of grasses are the principal storage and probably therefore

the principal food material. Six of the most important species

of grasses (disregarding species furnishing less than 5 grams) comprise

85.6 per cent of the total weight of storage from 22 dens.

Crowfoot grama (Bouteloua rothrockii) stands first in quantity in

the total, forming 39.4 per cent of all stored material, 46 per cent

of the six important grasses, and 45 per cent of all grasses. The

largest amount of storage of any one species of grass in any one

den on the Range Reserve also is of this species, 2,205 grams[5]

(Table 1, den 1, p. 20, and Pl. VII, Fig. 2). This is exceeded by

a dropseed grass, Sporobolus cryptandrus strictus, which amounted to

5,455 grams in a lot from Albuquerque, N. Mex. (Table 1, den 24, and

Pl. VIII, Fig. 1).

Of the species other than grasses found stored in these dens,

mesquite beans (Prosopis velutina) are most important both by

weight and number of dens containing them. The total for the 22

Range Reserve dens is 1,570 grams, or 35.9 per cent of the seeds

other than grasses, but only 5.1 per cent of the total storage. In

bulk mesquite beans do not loom up large, as they are probably

the heaviest material stored. Sections of pods which must have