The Project Gutenberg eBook of Ducks and Geese

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Ducks and Geese

Author: Harry M. Lamon

Rob R. Slocum

Release date: June 30, 2010 [eBook #33029]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steven Giacomelli, Simon Gardner, La Monte

H.P. Yarroll and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

produced by Core Historical Literature in Agriculture

(CHLA), Cornell University)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DUCKS AND GEESE ***

Transcriber's Note

The figure captions have been retained in the same order of appearance

as the plates in the original, but moved to follow the section which

each illustrates. The list of illustrations has been adjusted accordingly.

Minor inconsistencies in spelling have been retained as in the original.

Where typographical errors have been corrected and missing references

added, these are listed at the end of this book.

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Index

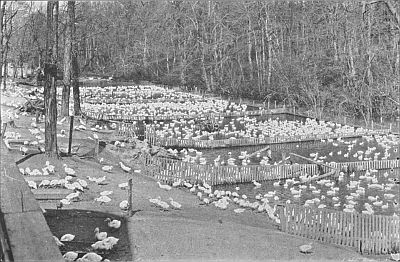

Frontispiece. General view of water yards and ducklings on a large Long Island duck farm. (Photograph

from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

DUCKS AND GEESE

BY

HARRY M. LAMON

SENIOR POULTRYMAN, BUREAU OF ANIMAL INDUSTRY, UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

AND

ROB R. SLOCUM

POULTRYMAN, BUREAU OF ANIMAL INDUSTRY, UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

Authors of

"The Mating and Breeding of Poultry"

and "Turkey Raising"

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

ORANGE JUDD PUBLISHING COMPANY

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRÜBNER & CO., LIMITED

1922

Copyright, 1922, by

Orange Judd Publishing Company

All Rights Reserved

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

[Pg v]

PREFACE

Of all lines of poultry keeping, duck raising is

unique in that it lends itself to the greatest degree

of specialization and intensification along lines

which are purely commercial. On a comparatively

small area thousands of ducklings can be reared and

marketed yearly. The call for information concerning

the methods used by these commercial duck

raisers has been considerable, and since such information

is not available in complete concise form

the present book has been prepared partly to furnish

just this information.

The methods used by successful Long Island duck

raisers differ widely in some particulars and since

in the space at command, it has been impossible to

describe all the methods used, the plan has been

adopted of detailing in the main the methods of one

successful grower. This it is believed will prove to

be more helpful and less confusing than to attempt

to give the method of several different men.

Much space has been given to the operations of

the commercial duck raisers but the fact is recognized

that the great bulk of the ducks entering into

[Pg vi]the trade of the country is the product of small

flocks kept on general farms. For this reason a

chapter has been added dealing with duck raising

on the farm, and attention is here called to the fact

that most of the information given under commercial

duck raising can be readily adapted to use in

connection with the farm flock.

Detailed, complete information on goose raising

is even more fragmentary than is the case with

ducks. Yet there is a fine opportunity to rear a few

geese at a profit on many farms, and the need and

call for information is quite general. It is for this

reason that a section of this book has been devoted

to goose raising and in that section all the good reliable

information available on the subject is given.

The special attention of the women of the farm is

directed to the opportunity which goose raising offers

to make a good profit on a small side line with

the minimum of initial investment and of labor.

The greatest care has been taken to make the information

on both duck and goose raising as complete

and clear as possible. However, the authors

appreciate the unlimited value of good illustrations

in making clear methods and operations which are

more difficult to grasp from a word description, and

have therefore assembled a set of illustrations for

this book, the completeness and excellence of which

have never before been approached in any book on

the subject. The illustrations alone are an education.

In preparing and presenting this book to the public,

the authors take pleasure in acknowledging[Pg vii]

their deep indebtedness to the following persons for

help and information furnished:

- Roy E. Pardee

- John C. Kriner

- Charles McClave

- Stanley Mason

- Dr. Balliet

- William Minnich

- George W. Hackett

- Dawson Brothers

Particular acknowledgment is due Robert A. Tuttle

for the manner in which he threw open his duck

plant to the authors and for the most generous

amount of time which he gave in furnishing information.

Special acknowledgment is likewise due Alfred

R. Lee, Poultryman, U. S. Department of Agriculture,

for information secured from his Farmers' Bulletins

on duck raising and goose raising.

[Pg ix]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Preface | ||

| List of Illustrations. | ||

| PART I—DUCKS | ||

| Chapter. | Page. | |

| I. | Extent of the Industry—Opportunities | 3 |

| Present Extent of the Industry—Different Types of Duck Raising—Opportunities for Duck Raising—Prices for Breeding Stock—Ducks for Ornamental Purposes. | ||

| II. | Breeds and Varieties—How to Mate to Produce Exhibition Specimens—Preparing Ducks for the Show—Catching and Handling | 9 |

| Breeds of Ducks—Classification of Breeds—Marking the Ducks—Nomenclature—Distinguishing the Sex—Size—Popularity of Breeds—Egg Production—Size of Duck Eggs—Color of Eggs—Broodiness—General Considerations in Making the Mating—Making the Mating—The Pekin—The Aylesbury—The Rouen—The Cayuga—The Call—The Gray Call—The White Call—The Black East India—The Muscovy—The Colored Muscovy—The White Muscovy—The Blue Swedish—The Crested White—The Buff—The Runner—The Fawn and White Runner—The White Runner—The Penciled Runner—Preparing Ducks for the Show—Catching and Handling Ducks—Packing and Shipping Hatching Eggs. | ||

| III. | Commercial Duck Farming—Location—Estimate of Equipment and Capital Necessary in Starting the Business | 42 |

| Distribution—Stock Used—Location of Plant—Making a Start in Duck Farming—Equipment, Capital, etc. Required—Lay-out or Arrangement of the Plant—Land Required—[Pg x]Number of Breeders required—Housing Required for Breeders—Incubator Capacity—Brooder Capacity—Fattening Houses or Sheds—Feed Storage—Killing and Picking House—Resident—Horse Power—Feeding Track—Electric Lights—Water Supply—Fences—Labor—Invested Capital—Working Capital—Profits. | ||

| IV. | Commercial Duck Farming—Management of the Breeding Stock | 55 |

| Age of Breeders—Distinguishing Young from Old Ducks—Selection of Breeding Ducks—Number of Females to a Drake—Securing Breeding Drakes—Houses and Yards for Breeders—Bedding and Cleaning the Breeding Houses—Cleaning the Breeding Yards—Water Yards for Breeders—Feeding the Breeders—Egg Production—Time of Marketing Breeders—Disease—Insect Pests—Dogs. | ||

| V. | Commercial Duck Farming—Incubation | 70 |

| Kinds of incubators used—Incubator Cellar—Incubator Capacity Required—Age of Hatching Eggs—Care of Hatching Eggs—Selecting the Eggs for Hatching—Temperature—Position of Thermometer—Testing—Turning the Eggs—Cooling the Eggs—Moisture—Fertility—Hatching—Selling Baby Ducks. | ||

| VI. | Commercial Duck Farming—Brooding and Rearing the Young Stock | 80 |

| Removing the Newly Hatched Ducklings to the Brooder House—Brooder Houses Required—Brooder House No. 1—Construction of House—Heating Apparatus—Pens—Equipment of the Pens—Grading and Sorting the Ducklings—Cleaning and Bedding the Pens—Ventilation—Other Types of Brooder Houses—Length of Time in Brooder House No. 1—Brooder House No. 2—Brooder House No. 3—Yard Accommodations for Ducklings—Shade—Feeding—Lights for Ducklings—Pounds of Feed to Produce a Pound of Market Duck—Water for Young Ducks—Age and Weight when Ready for Market—Cripples—Cleaning the Yards—Critical Period with [Pg xi]Young Ducks—Disease Prevention—Gapes or Pneumonia—Fits—Diarrhoea—Lameness—Sore Eyes—Feather Eating or Quilling—Rats—Cooperative Feed Association. | ||

| VII. | Commercial Duck Farming—Marketing | 102 |

| Proper Age to Market—Weights at Time of Marketing—The Last Feed for Market Ducks—Sorting Market Ducklings—Killing—Scalding—Picking—Dry Picking—Cooling—Packing—Shipping—Cooperative Marketing Association—Prices for Ducks—Shipping Ducks Alive—Saving the Feathers—Prices and Uses of Duck Feathers—Marketing Eggs. | ||

| VIII. | Duck Raising, on the Farm | 120 |

| Conditions Suitable for Duck Raising—Size of Flock—Making a Start—Selecting the Breed—Age of Breeding Stock—Size of Matings—Breeding and Laying Season—Management of Breeders—Housing—Feeding—Water—Yards—Care of Eggs for Hatching—Hatching the Eggs—Brooding and Rearing—Feeding the Ducklings—Water for Ducklings—Distinguishing the Sexes—Marketing the Ducks—Diseases and Insect Pests. | ||

| PART II—GEESE | ||

| IX. | Extent of the Industry—Opportunities | 141 |

| Nature of the Industry—Opportunities for Goose Raising—Goose Raising as a Business for Farm Women—Geese as Weed Destroyers—Objections to Geese. | ||

| X. | Breeds and Varieties—How to Mate to Produce Exhibition Specimens—Preparing Geese for the Show—Catching and Handling | 147 |

| Breeds of Geese—Nomenclature—Size—Popularity of the Breeds—Egg Production—Size of Goose Eggs—Color of Goose Eggs—Broodiness—Size of Mating—Age of Breeders—Marking Young Geese—General Considerations in Making the Mating—Making the Mating—The Toulouse—The Embden—The African—The Chinese—The Brown Chinese—The White Chinese—The Wild or Canadian—The [Pg xii]Egyptian—Preparing Geese for the Show—Catching and Handling Geese—Packing and Shipping Hatching Eggs—Prices for Breeding Stock. | ||

| XI. | Management of Breeding Geese | 164 |

| Range for Breeders—Number of Geese to the Acre—Water for Breeding Geese—Distinguishing the Sex—Purchase of Breeding Stock—Time of Laying—Housing—Yards—Feeding the Breeding Geese. | ||

| XII. | Incubation | 172 |

| Care of Eggs for Hatching—Methods of Incubation—Period of Incubation—Hatching with Chicken Hens—Hatching with Geese—Breaking Up Broody Geese—Hatching with an Incubator—Moisture for Hatching Eggs—Hatching. | ||

| XIII. | Brooding and Rearing Goslings | 178 |

| Methods of Brooding—Brooding with Hens or Geese—Length of Time Brooding is Necessary—Artificial Brooding—General Care of Growing Goslings—Feeding the Goslings—Percentage of Goslings Raised—Rapidity of Growth—Diseases. | ||

| XIV. | Fattening and Marketing Geese | 187 |

| Classes of Geese Marketed—Markets and Prices—Prejudice Against Roast Goose—Methods of Fattening Geese for Market—Pen Fattening—Noodling Geese—Methods Used on Fattening Farms—Selling Geese Alive—Killing—Picking—Packing for Shipment—Saving the Feathers—Plucking Live Geese for their Feathers. | ||

| Index | 215 |

[Pg xiii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Frontispiece. Water Yards and Ducklings. | ||

| 1. | Mule Ducks and Blue Swedish Ducks | 11 |

| 2. | Mallard Ducks | 11 |

| 3. | Goose, Duck and Hen Eggs | 17 |

| 4. | Young Pekins for Breeders and Aylesbury Drake | 23 |

| 5. | Rouen Drake and Black East India Ducks | 24 |

| 6. | Rouen Drake in Summer Plumage and Rouen Duck | 25 |

| 7. | Cayuga Ducks | 27 |

| 8. | Gray Call Ducks | 28 |

| 9. | White Call Ducks | 29 |

| 10. | Colored Muscovy Drake and White Muscovy Drake | 32 |

| 11. | Crested White Drake and Young White Muscovy Showing Black on Head | 33 |

| 12. | Wing of Blue Swedish Duck | 34 |

| 13. | Pair of Buff Ducks | 36 |

| 14. | Penciled Runner Drake and White Runner Drake | 37 |

| 15. | Methods of Carrying Ducks | 40 |

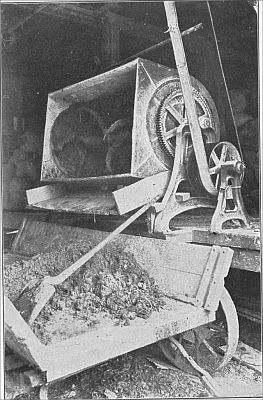

| 16. | Power Feed Mixer | 51 |

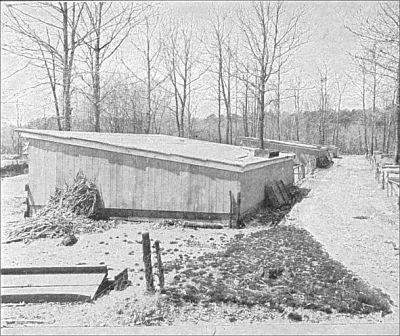

| 17. | Duck Houses | 60 |

| 18. | House for Breeding Ducks | 60 |

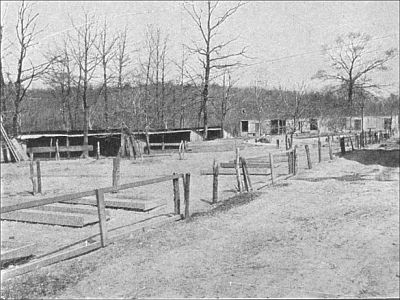

| 19. | Another Type of Breeding House | 63 |

| 20. | Feeding the Breeders | 63 |

| 21. | Interior of Breeding House | 75 |

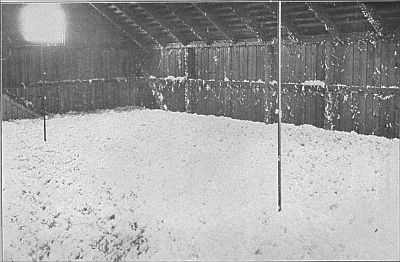

| 22. | Incubator Cellar | 75 |

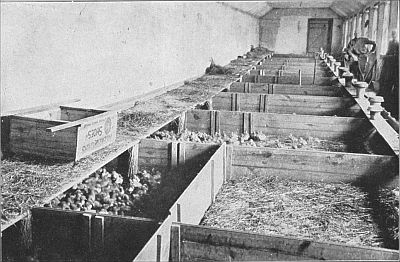

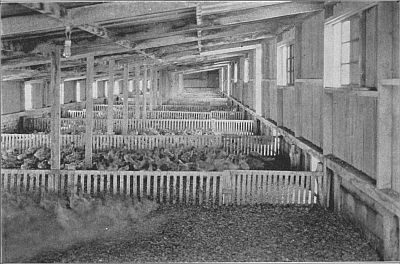

| 23. | Interior of No. 1 Brooder House | 83 |

| 24. | Watering Arrangement in Brooder Pens | 87 |

| 25. | Another Type of No. 1 Brooder House | 87 |

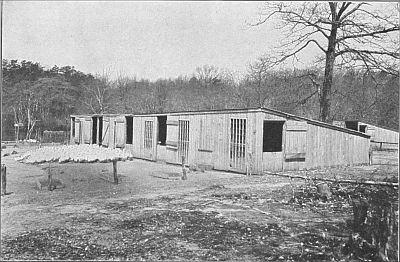

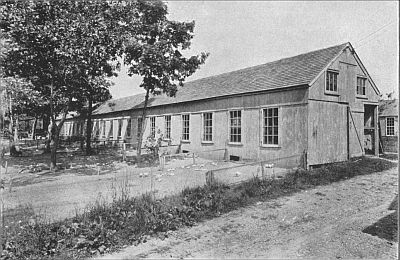

| 26. | Brooder House No. 2 | 90 |

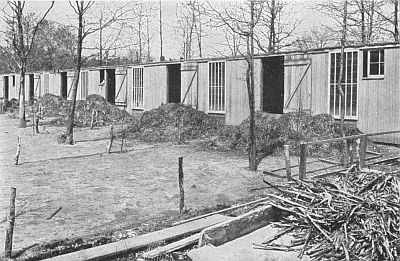

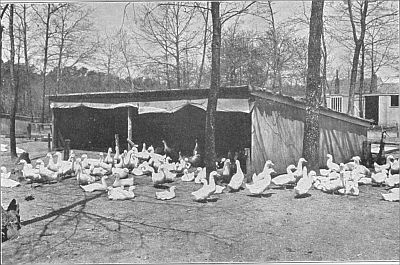

| 27. | Brooder House No. 3 | 91 |

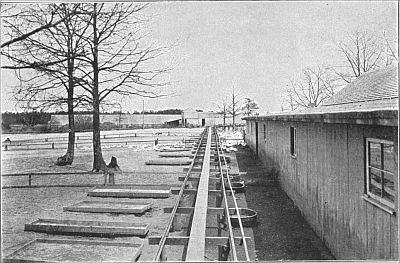

| 28. | Long Brooder House and Yards | 91 |

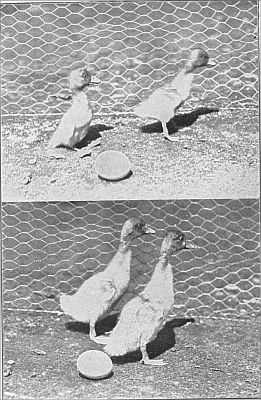

| 29. | Pekin Ducklings 3 Days and 2 Weeks Old | 91 |

| 30. | Pekin Ducklings 3 Weeks and 6 Weeks Old[Pg xiv] | 91 |

| 31. | Interior of Cold Brooder House | 91 |

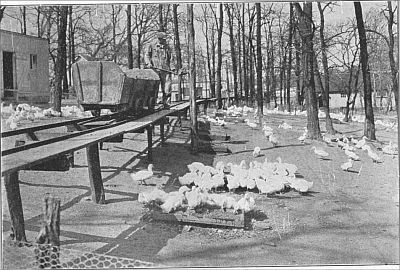

| 32. | Yard Ducks | 92 |

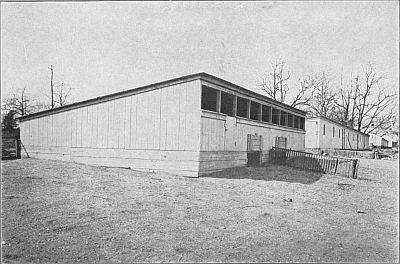

| 33. | Duck Sheds | 95 |

| 34. | Feeding and Watering Arrangements | 95 |

| 35. | Green Feed for Ducks | 96 |

| 36. | Feeding from Track | 97 |

| 37. | Yard Ducks at Rest | 98 |

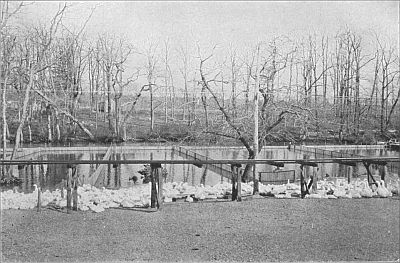

| 38. | Artificial Water Yards | 98 |

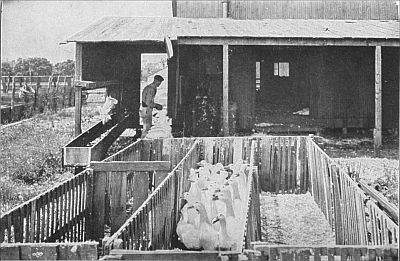

| 39. | Catching Pens for Fattening Ducklings | 104 |

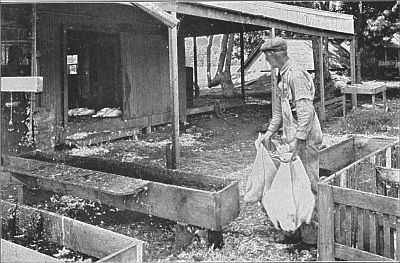

| 40. | Carrying Ducklings to Slaughter | 104 |

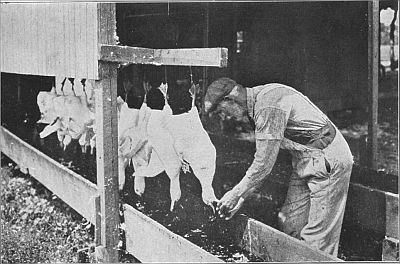

| 41. | Hanging Ducklings and Cutting Throat Veins | 105 |

| 42. | Bleeding Ducklings | 105 |

| 43. | Washing Heads | 105 |

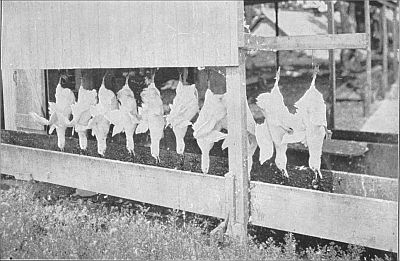

| 44. | Ducklings Ready for the Pickers | 105 |

| 45. | Scalding | 106 |

| 46. | Picking Ducks | 107 |

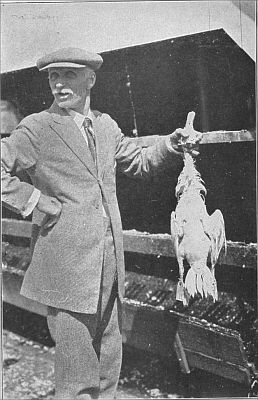

| 47. | Dressed Duckling | 109 |

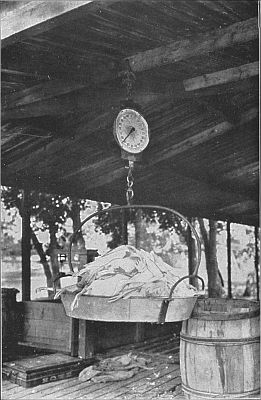

| 48. | Weighing Out Ducklings for Packing | 109 |

| 49. | Curing Duck Feathers | 118 |

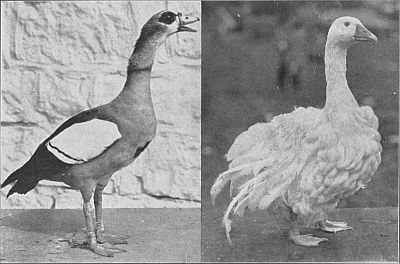

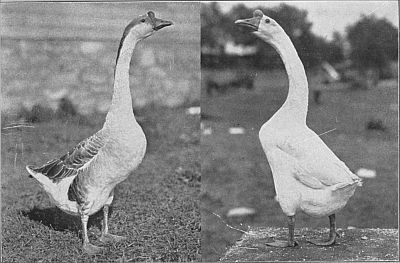

| 50. | Egyptian Gander and Sebastapol Goose | 161 |

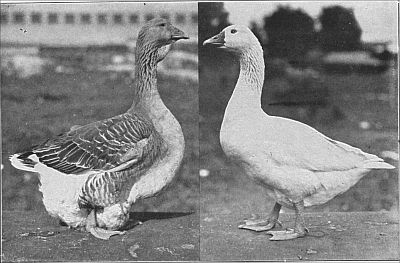

| 51. | Toulouse and Embden Ganders | 161 |

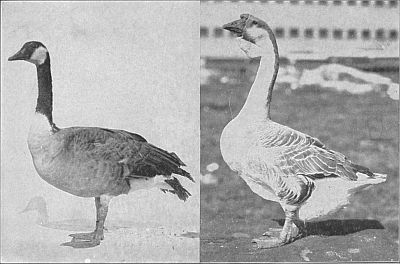

| 52. | Canadian and African Ganders | 161 |

| 53. | Brown and White Chinese Ganders | 161 |

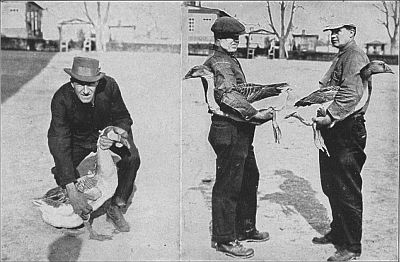

| 54. | Methods of Handling Geese | 162 |

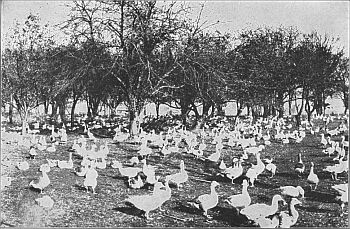

| 55. | Geese Fattening in an Orchard | 200 |

[Pg 1]

DUCKS

PART I

[Pg 3]

CHAPTER I

Present Extent of the Industry

Duck raising while representing an industry of

considerable value to the United States when considered

from a national standpoint, is one of the minor

branches of the poultry industry. According to the

1920 census there were 2,817,624 ducks in the United

States with a valuation of $3,373,966. As compared

with this the census for 1910 shows a slightly greater

number of ducks, 2,906,525, but their value was considerably

less being only $1,567,164. In the ten

years between the census of 1900 and that of 1910

there was a decrease in the number of ducks of

nearly 40%.

According to the 1920 census the more important

duck raising states arranged in their order of importance

were Iowa, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New

York, Missouri, Minnesota, Tennessee, Ohio, South

Dakota, Indiana, Nebraska and Kentucky. The number

reported for Iowa was 235,249 and for Kentucky

99,577. New England, the North Atlantic, the East

North Central, the West North Central, the Moun[Pg 4]tain

and the Pacific states showed an increase, while

the South Atlantic, East South Central and West

South Central states showed a decrease. In spite of

the existence of quite a number of large commercial

duck farms, the great bulk of ducks produced are

those which come from the general farms where

only small flocks are kept. Yet only a small proportion

of farms have ducks on them. The comparatively

small number of ducks is distributed over

practically the entire United States, being more common

in some sections than others, particularly along

the Atlantic Coast and along the Pacific Coast, with

fairly numerous flocks on the farms of the Middle

West.

Different Types of Duck Raising. The conditions

under which ducks are kept and the purpose for

which they are kept fall under four heads: First,

commercial duck raising for the production of duck

meat; second, duck raising as a by-product of the

general farm; third, duck raising for egg production;

fourth, duck breeding for pleasure, exhibition

or the sale of breeding stock.

Opportunities for Duck Raising. Undoubtedly the

greatest opportunity for profitable duck growing

lies under the first of these heads, namely, commercial

duck raising. Where the conditions of climate,

soil and land are favorable and where the location

is good with respect to market there exists an excellent

opportunity for one skilled in duck growing

to engage in that business in an intensive manner[Pg 5]

for the purpose of putting on the market spring or

green ducklings. Where these are in demand they

bring a good price and since the output per farm is

large they pay a good return even with a small margin

of profit per pound.

The second greatest opportunity undoubtedly

consists of duck raising as a by-product of the general

farm. Where conditions are suitable, that is to

say, where there is a considerable amount of pasture

land easily accessible, and particularly where there

is a stream or pond to which the ducks can have access,

a small flock of ducks, say 10 or 12 females,

can be kept to excellent advantage on the farm. The

cost of maintaining them will not be great and they

will not only provide a most acceptable variety in

the form of duck meat and duck eggs for the farmers'

table but they will also produce a surplus which

can be sold at a profit. It must be remembered,

however, that where only a small flock is kept it is

generally impracticable for the farmer to give his

ducks the attention necessary to cater to the market

for green ducklings. As a result he usually keeps

them until fall and sells them on the market at a

considerably lower price than is obtained by the

commercial duck grower.

There also exists an opportunity which has not

been developed to any great extent to keep some one

of the egg producing breeds of ducks such as the Indian

Runner for the primary purpose of egg production.

A few ventures of this sort seem to have been[Pg 6]

successful but it must be remembered that the market

for duck eggs is not nearly so broad as that for hens'

eggs and that in some quarters there exists considerable

prejudice against duck eggs for table consumption.

Before engaging in duck raising primarily

for the production of market eggs it would therefore

be necessary to investigate and consider carefully

the market conditions in the neighborhood so as to

know whether the eggs could be marketed to advantage.

While the Runner ducks are prolific layers

there is no advantage in keeping them in preference

to fowls as egg producers. The eggs are larger

in size but it takes more feed to produce them, while

they cannot as a rule be disposed of at much if any

higher price than can be secured for hens' eggs.

For baking purposes duck eggs can be readily sold

on account of their larger size.

There is always an opportunity to produce fine

stock of any kind, whether it be ducks, chickens,

turkeys or geese. Ducks are not exhibited to the

same extent as are chickens and the competition in

the shows is not as a rule so keen. Nevertheless

many persons are interested in producing and exhibiting

good stock and there exists a very definite

market for birds of quality.

There is also a probability that a good business

could be worked up by one who would pay special

attention to producing a strain of ducks of early

maturity, large size and good vigor in order to supply

breeding drakes to many of the commercial[Pg 7]

duck farms. These farms usually secure drakes for

breeding from sources outside their own flocks each

year but the usual practice is to exchange drakes

with some other commercial grower. While very

good birds are to be found on these duck farms

there is no greater opportunity to engage in any systematic

breeding, the selection of the breeding stock

being of rather a hurried nature during certain seasons

of the year when the ducks are being marketed.

Moreover, the long continued custom of exchanging

drakes with the neighboring farmers has in most

cases led to the blood being so largely confined within

one circle that no great percentage of new blood

is obtained by these exchanges. Of course, the opportunity

along breeding lines for this purpose is

limited to the Pekin duck as this is the breed which

is kept upon all the large commercial duck farms

in the United States.

Prices for Breeding Stock. Duck breeders who

make a specialty of selling breeding stock or eggs

for hatching find a steady and quite a wide demand

for their stock. The eggs are usually sold in sittings

of 11 and bring a price of from $3 to $5 per sitting

depending on the quality of the stock. The prices

received for the birds themselves depend of course

upon their quality and may run anywhere from

about $5 to $25 per bird.

Ducks for Ornamental Purposes. On estates or in

parks where natural or artificial ponds are included

in the grounds, waterfowl are often kept for orna[Pg 8]mental

purposes. Any breeds may be used, and

often the gay colored Wood Duck and Mandarin, or

some one of the small breeds such as the Calls,

Black East Indian or the Mallards are kept for this

purpose. It is said that these small ducks will absolutely

destroy the mosquito larvae in any such ponds

or lakes.

[Pg 9]

CHAPTER II

Breeds and Varieties—How to Mate to Produce Exhibition

Specimens—Preparing Ducks for the

Show—Catching and Handling

Breeds of Ducks. There are 11 standard breeds

of ducks. All of these breeds with the exception of

the Call, Muscovy and Runner consist of a single

variety. The Call is divided into two varieties, the

Gray and the White; the Muscovy consists of two

varieties, the Colored and the White; and the Runner

consists of three varieties, the Fawn and White,

the White and the Penciled.

Duck breeders, of course, whether raising the

birds for fancy or for profit, keep one of the standard

breads or varieties. Frequently, also, the farm

flocks consist of standardbred ducks but on many

farms, probably a great majority, the flock consists

of the common or so-called "puddle" duck. In certain

parts of the South there is a duck known as the

"mule duck" which is a cross between the Muscovy

and the common duck. This is a duck of good market

quality but will not breed from which characteristic

it gets its name. Most of the common or

"puddle" ducks which are found on farms are of

rather small size, are indifferent as layers, and do[Pg 10]

not make a desirable type of market duck. They

have arisen simply from the crossing of standard

breeds with resultant carelessness and indifference

in breeding. Because of the care with which they

have been selected and bred for definite purposes,

the standard breeds are decidedly superior to the

common "puddle" ducks and should by all means

be kept in preference since they will yield better

results and greater profits.

In addition to the standard breeds and varieties

flocks of Mallards are also kept to a limited extent.

The Mallard is a common small wild duck which

has lent itself readily to domestication and which

thrives with proper care under confined conditions.

In weight, the drakes will run from 2½ pounds to 3

pounds or even a little larger. The ducks average

about 2¼ pounds with a variation of from 1 pound

12 ounces to 2 pounds 8 ounces. By selecting the

large eggs for hatching and by liberal feeding, it is

easy to increase the size of Mallards to such an extent

that they resemble small Rouens rather than

wild Mallards. The plumage of the Mallard is very

similar to that of the Rouen but of a lighter shade.

Another small wild duck known as the Wood or

Carolina duck, which is a native of North America,

has been domesticated and on account of the great

beauty of its plumage is usually to be found wherever

ornamental waterfowl are kept. The Mandarin

duck is a small duck of about the same size as

the Wood duck, is of beautiful plumage and like the[Pg 11]

Wood duck is generally kept for ornamental purposes.

This duck is said to be a native of China.

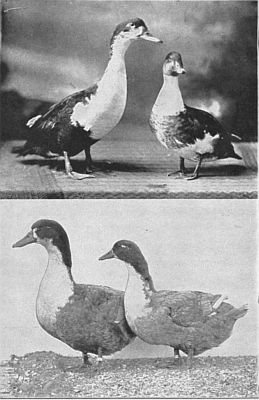

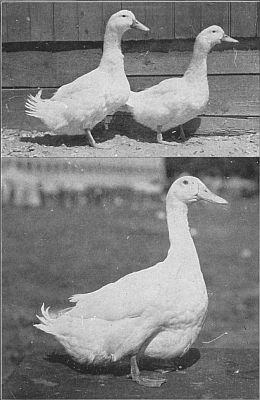

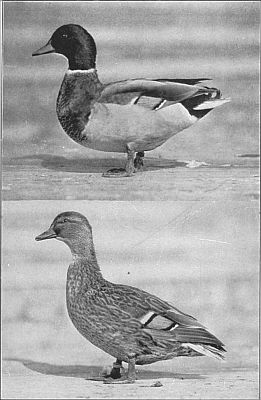

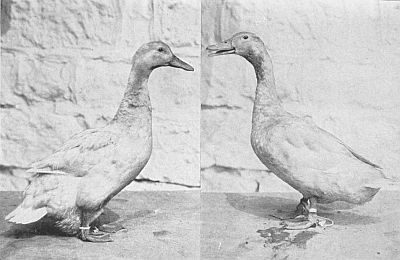

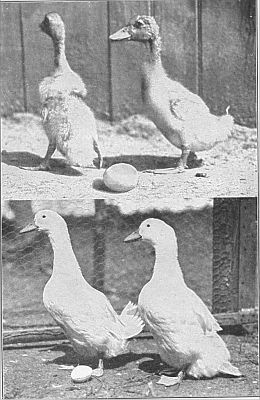

Fig. 1. Upper—Pair of Mule Ducks. Lower—Pair of Blue

Swedish Ducks. (Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S.

Department of Agriculture.)

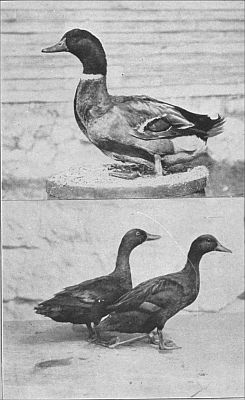

Fig. 2. Upper—Mallard Duck. Lower—Mallard Drake. The

Mallard is a wild duck which is quite easily domesticated and which has

a plumage color very similar to the Rouen. It is small in size.

(Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of

Agriculture.)

Classification of Breeds

So far as the standard breeds and varieties are

concerned they may be divided into three classes

according to the purpose for which they are kept

and for which they are best suited. First is the meat

class which consists of the Pekin, Aylesbury, Muscovy,

Rouen, Buff, Cayuga and Blue Swedish. These

breeds could well be termed general purpose ducks

for they are quite good layers in addition to producing

excellent table carcasses and are therefore well

suited for general farm use. They are, however,

kept more particularly for meat production.

The second class is known as the egg class and

consists of the three varieties of the Runner Duck,

formerly known as the Indian Runner. The Runner

Duck is much smaller in size than the birds of the

meat class, is longer in leg and more active, and is

not so well suited for the production of table ducks

but is a very prolific layer. With proper feeding

and management the Runner ducks will compare

favorably with hens as egg producers.

The third class is known as the ornamental class

and is composed of the ducks which are kept and

bred principally for ornamental purposes. This

class consists of the Call duck with its two varieties,[Pg 12]

the Black East India duck and the Crested White

duck. Both the Call and East India ducks are small

in size being really the bantams of the duck family.

While they make good table birds, their small size

handicaps them as commercial meat fowl. The

Crested White duck is of larger size, possesses a

crest and is bred mainly as an ornamental fowl.

Marking the Ducks. The duck raiser who is

breeding his ducks for exhibition quality has need

for knowledge of the breeding of the birds he may

contemplate using in his matings. In order that this

information may be available, the young ducks as

they are hatched can be marked by toe punching

them on the webs of their feet in the same manner

that baby chicks are toe punched. A different set

or combination of marks is used for each mating so

that the breeding of the different ducks can be distinguished.

Mature ducks can, if desired, be leg

banded in order to furnish a distinguishing mark.

Nomenclature

Before taking up a description of the matings of

the different standard breeds and varieties it is well

to indicate the common nomenclature which is used

in connection with these fowls and which differs

from that used for chickens. The male duck is

called drake, the female duck is termed duck, and

the young duck of either sex is termed duckling. In

giving the standard weights for the different breeds[Pg 13]

of ducks, weights are given for adult ducks and

adult drakes, and for young ducks and young

drakes. By adult duck or drake is meant a bird

which is over one year old. By young duck or drake

is meant a bird which is less than one year old. The

horny mouth parts of the duck instead of being

termed beak as in chickens are called bill, and the

separate division of the upper bill at its extremity

is termed the bean. Ducks do not show any comb

or wattles as in chickens. In England use is made of

the terms ducklet and drakerel. Ducklet is used to

signify a female during her first laying season just

as the word pullet is used in contrast to hen. Drakerel

is used to signify a young drake as contrasted

with an older drake just as the word cockerel is used

in comparison to cock in chickens.

Distinguishing the Sex. The sex of mature ducks

can be readily told by their voices and also by a difference

in the feathering. The duck gives voice to a

coarse, harsh sound which is the characteristic

"quack" usually thought of in connection with this

class of fowl. The drake on the other hand utters

a cry which is not nearly so loud or harsh but which

is more of a hissing sound. Distinction of sex by this

means can be made after the ducklings are from 4

to 6 weeks old. Before this age, both sexes make

the same peeping noise.

Mature drakes are also distinguished from the

ducks by the presence of two sex feathers at the

base of the tail. These are short feathers which[Pg 14]

curl or curve upward and forward toward the body

of the bird. In ducks these feathers are absent.

Size

An idea of the size of the different standard

breeds can best be obtained by giving the standard

weights. They are as follows:—

| Adult Drake. | Adult Duck. | Young Drake. | Young Duck. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pekin | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Aylesbury | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Rouen | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Cayuga | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Muscovy | 10 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| Blue Swedish | 8 | 7 | 6½ | 5½ |

| Crested White | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Buff | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Runner | 4½ | 4 | 4 | 3½ |

There are no standard weights for the Call duck

and for the Black East India duck but these are all

small in size, being really bantam ducks. The drakes

will weigh from 2½ to 3 pounds and the ducks from

2 to 2½ pounds.

Popularity of Breeds

In the meat class by far the most popular duck in

this country is the Pekin. It is the breed which is[Pg 15]

used exclusively on the large commercial duck

farms. Next to the Pekin in this class probably

comes the Muscovy which is quite commonly kept in

some sections of the country, particularly in the

South. The Aylesbury duck has never proved to be

very popular in the United States perhaps due to its

white bill and skin, although it is the popular market

duck of England. The other breeds included in

the meat class are kept more or less commonly but

do not approach in popularity either the Pekin or

the Muscovy. Any of the breeds in this class will

prove to be satisfactory for a farm flock, although

the Colored breeds and varieties are at a disadvantage

when dressed due to their dark pin feathers.

In the egg class there is included only the Indian

Runner and this of course is the breed which is kept

wherever the production of duck eggs is the primary

object. The Fawn and White is the most popular

variety of this breed.

In the ornamental class there is no particular outstanding

breed, since the ducks belonging in this

class are kept very largely to satisfy the pleasure of

the owner and the selection of a breed is entirely a

matter of personal preference.

Egg Production

While the conditions under which ducks are kept

and the care they are given will affect their egg pro[Pg 16]duction

greatly, there are certain rather definite

comparisons that can be made between the different

breeds. The Pekin is a good layer and will produce

from 80 to 120 eggs. The Aylesbury and the Rouen

are about alike in laying ability, neither being quite

as good as the Pekin. The Cayuga is a good layer

ranking with the Aylesbury and Rouen or between

these and the Pekin. The Muscovy is an excellent

layer being fully as prolific as the Pekin, especially

if broken up when broody and not allowed to sit. The

Blue Swedish is about equal to the Cayuga in laying

ability. The Buff duck is an excellent layer comparing

favorably with the Pekin or even with the

Runner. The Runner ducks are the best layers of

the duck family and if given proper care and good

feed will compare favorably with hens in egg producing

ability. The Crested White duck is not a particularly

good layer. The Calls and the Black East India

ducks will lay from 20 to 60 eggs per year, approaching

the latter number if the eggs are collected

as laid and the ducks are not allowed to sit which

will induce some of them to continue to lay for quite

a portion of the year. Extremely large ducks of any

breed do not lay as well as the more medium sized

birds.

Size of Duck Eggs. The eggs of the different

meat breeds will run about the same in size with

the exception of the Muscovy whose eggs run a little

larger. Actual weights of eggs from representative

flocks show Pekin, Rouen, Aylesbury and Cayuga[Pg 17]

eggs to average about 2½ pounds per dozen although

there is a tendency for the Rouen eggs to run somewhat

larger and for Cayugas to run a little smaller.

Muscovy eggs weigh about 3 pounds per dozen with

selected large eggs weighing as high as 3¼ pounds.

Eggs of the Runner duck are smaller but are considerably

larger than average hens' eggs or about the

size of large Minorca eggs. They weigh about 2

pounds per dozen. Eggs of the bantam breeds of

ducks, the Calls and the Black East India, together

with those of the Mandarin and Wood ducks will

weigh from one pound to 1½ pounds per dozen depending

upon the size of the ducks themselves. Eggs

of the Mallard duck will run from 26 to 32 ounces

to the dozen. The size of eggs laid by ducks, especially

the bantam breeds and the Mallard can be

increased somewhat by liberal feeding. Average

hens' eggs should weigh about 1½ pounds per dozen.

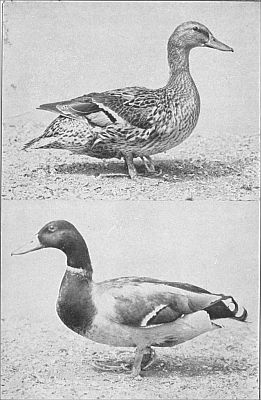

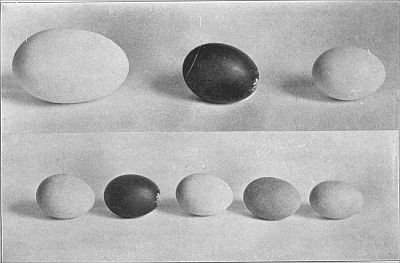

Fig. 3. Upper—Comparison of size of goose egg on the left a black egg of a Cayuga duck in the center

and a hen egg on the right. Lower—Duck eggs—At the left is a Pekin duck egg, next a black egg laid by a

Cayuga duck, third a Muscovy egg, fourth a duck egg of green color and on the extreme right the egg of

a Runner duck. (Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

Color of Eggs. The color of duck eggs ranges

from white to a polished black. Pekin eggs run

mostly white although some show a decided blue

or green tint. Aylesbury eggs run quite uniformly

white. The color of Rouen eggs varies from white

to a dark green. The Cayuga produces very few

white eggs, most of them being green or black, some

being as black as though polished. Muscovy eggs

run from a white to a greenish cream in color. The

eggs of the Blue Swedish and the Buff ducks usually

run white. The Runner duck lays white eggs as a

rule while the Crested White duck lays eggs which[Pg 18]

range in color from white to green. The eggs of the

Call ducks run from white to green while the eggs

of the Black East India, like the Cayuga, for the

most part run from green to black.

A peculiarity in regard to the egg color is that the

same female may lay eggs which are widely different

in color. It is likewise true that the color of the

shell is influenced to some extent by the feed. Ducks

on range will lay darker colored eggs than those

which are yarded. There is also a tendency for the

eggs to run darker in color when laying first begins

and for the eggs to lighten as laying proceeds. A

peculiarity in regard to duck eggs with a dark

colored shell is that a thorough washing will lighten

up the shell color decidedly.

Broodiness. The Muscovy, the Call and the Black

East India ducks are broody breeds. The ducks of

these breeds will make their nests, hatch their eggs

and are good mothers. All the other breeds are

classed as non-broody breeds. Of course, a certain

percentage of them will go broody and show a desire

to sit but they do not make reliable sitters and

mothers and are not as a rule used for this purpose.

Considerations in Making the Mating[1]

Since ducks are kept for different purposes there[Pg 19]

will of course be certain fundamental differences in

the different classes in the selection of the individuals

to make up the mating. Whatever the purpose,

however, the first consideration in selecting the

breeders must be to secure those which possess excellent

vigor and general health and which meet

insofar as possible the standard requirements for

size. Where the Call duck and the Black East India

are concerned the selection for size must be for

smallness since that is a characteristic greatly desired.

In the other breeds the selection for size must

be to see that they come up to the standard weights

for the particular breed in question. As in other

classes of fowls the condition and cleanliness of the

plumage and the general appearance and actions of

the birds are good indications of their health and

thriftiness. A bright eye is likewise a valuable indication

of good health while a watery eye is usually a

sign of weakness. It is necessary to guard against

birds which show any tendency toward crooked or

roach back, hump back, crooked tails, or twisted

wings. Since all breeds of ducks should have clean or

unfeathered legs it is likewise necessary to guard

against any breeders which show down on the

shanks or between the toes as this sometimes occurs.

[1] For a more detailed discussion of the principles of breeding

as applied to chickens and which is equally applicable to ducks,

the reader is referred to "The Mating and Breeding of Poultry"

by Harry M. Lamon and Rob R. Slocum, published by the

Orange Judd Publishing Company, New York City.

In selecting the mating for any one of the meat

breeds use birds which have good length, width and

depth of body so that they will have plenty of meat[Pg 20]

carrying capacity. For breeders of market ducks,

birds which are active, well matured and which are

not extreme in size for the breed are preferable as

the fertility is likely to run better than with the extremely

large birds. Where birds are bred for exhibition

purposes, it frequently happens that it is

desirable to use large breeders and to hold them for

breeding purposes as long as they are in good breeding

condition. Where this is the case it becomes

necessary to mate a smaller number of females to

a drake than would be the case with smaller and

younger breeders. Where old birds are used as

breeders better results will be secured by mating old

ducks to a young drake or vice versa than by mating

together old birds of both sexes. While ducks of any

of the meat breeds are kept primarily for meat production,

it is essential that the egg production be good

throughout the breeding season in order to raise as

many ducklings and secure as great a profit as possible.

Selection of the females as breeders should be

made therefore on the basis of good egg production

as well as good meat type if the conditions under

which the ducks are kept are such as to make it

possible to check this in any manner.

In selecting the mating in the Runner breed it is

necessary to keep in mind that the general type of

body is quite different from that of the meat breeds,

being much slimmer and much more upright in body

carriage. For this mating select thrifty, healthy

birds and those which are active. Some breeders[Pg 21]

trapnest their Runner ducks or have some other

means of checking up the better layers. As in

chickens, it is of course desirable to use these better

layers as breeders since the purpose in keeping this

kind of duck is primarily egg production.

In selecting the mating in the Call and East India

breeds it is necessary to use the smaller ducks since

the object here is to keep the size small. In addition,

with these breeds or with any other breeds kept

and bred primarily for fancy or exhibition purposes,

it is necessary to conform just as closely as possible

to the standard requirements[2] both insofar as size

and type are concerned, and also with respect to

color.

[2] For a complete and official description and list of disqualifications

of the standard breeds and varieties of ducks, the

reader is referred to the American Standard of Perfection published

by the American Poultry Association, and obtained by

Orange Judd Publishing Company, New York, N. Y.

Breeds of Ducks

The Pekin. While this variety wants to be of

good size and to have length, breadth and depth of

body it is somewhat more upstanding than some of

the other meat breeds, showing a definite slope of

body downward from shoulders to tail. The back

line of the Pekin should show a slight concavity

from the shoulders to the tail and the upper line of

the bill is likewise slightly concave between the

point where it joins the head and its extremity. The

[Pg 22]shoulders should be broad and any tendency toward

narrowness at this point must be avoided. While a

good depth of keel is desired, the standard does not

call for so deep a keel as in the Aylesbury. As a

matter of fact, however, the winning specimens as

seen in the shows are not as a rule as erect in carriage

as called for by the standard illustration,

there being a tendency to get them almost if not

quite as deep in keel as the Aylesbury. In fact,

some breeders seem to strive for a low down keel

approaching a condition where they are nearly as

low in front as behind but this is not desirable Pekin

type.

Sometimes a drake will show a rough neck, that

is, the feathers on the back of the neck will be

crossed or folded over showing a tendency to curl.

These birds should be avoided as breeders since

there is a tendency for them to produce ducks having

a crest. Sometimes a green or a greenish spotted

bill will be encountered. Since the bill should be a

clear yellow, breeders showing this defect should be

avoided particularly as they are likely to produce

birds having greenish or olive colored legs. The

shanks and toes should be a clear deep orange.

Black sometimes occurs in the bean. This may occur

in birds of either sex but is more common in the

ducks than in the drakes. In the drake black in the

bean disqualifies but while it is undesirable and a

serious defect in the duck it does not disqualify. The

color of the plumage is white or creamy white[Pg 23]

throughout. Creaminess in this variety is not a

serious defect as it is in white chickens. The use,

however, of yellow corn and of foods very rich in

oil tends to increase the creaminess of the plumage

and should not be used to excess for birds which are

to be exhibited.

Fig. 4. Upper—Young Pekins which on account of their size,

thriftiness and rapid growth were selected out of a lot about to be

killed for market and saved for breeders. Lower—Aylesbury

Drake—Notice the depth and development of the breast. (Photographs

from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of

Agriculture.)

The Aylesbury. This breed is particularly noted

for its deep keel. It differs from the Pekin in type

in that it is more nearly level in body. There is a

decided tendency for the Aylesbury to run too short

in body which has probably come about by extreme

selection for deep keel. It is well, therefore, in making

the mating to select breeders with good length

of body. Since the deep full breast and keel is characteristic

of this breed it is necessary to avoid breeders

which show any tendency toward a flat breast.

As in the case of the Pekins avoid any birds which

have green or olive colored bills. The back line of

the Aylesbury should be straight, showing no tendency

toward a slight concavity as in the Pekin.

Birds showing this shape back should be avoided.

As in the Pekin black on the bill or bean of the

drake will disqualify and in the duck is a serious defect.

The color of plumage should be white throughout

and should show no tendency toward creaminess.

The bill in this breed is flesh colored instead

of yellow as in the Pekin. The Aylesbury is not

quite as nervous a breed as the Pekin.

The Rouen. The Rouen duck is a parti-colored

breed and is therefore much more difficult to secure[Pg 24]

in perfection of color and marking than is the case

with the white breeds. Moreover, the dark pin

feathers make the ducks more difficult to dress

than in white breeds. In type these birds are very

level in body and are massive, carrying a great deal

of meat. Avoid birds showing a lack of length of

body or depth of keel or which are too flat in breast.

The back of the Rouen should have a slightly convex

or arched shape from neck to tail and it is necessary

to guard against birds which have a flat or a concave

back. The body of the Rouen should be carried

practically horizontal. The upper line of the bill

should be slightly dished or concave. The white

ring about the neck of the drake is an important

part of the marking. This should not be too wide

but should run about a quarter of an inch in width.

It should be as distinct and clean cut as possible but

should not quite come together in the rear. Any approach

to a ring in the female is a disqualification.

White in the primary or secondary wing feathers is

a serious defect since it constitutes a disqualification.

It must therefore be carefully avoided.

White feathers in the fluff of the drake is another

color defect which must be guarded against.

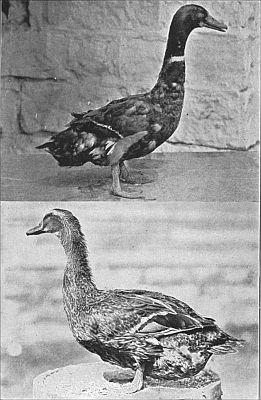

Fig. 5. Upper—Rouen Drake. Notice the low set, nearly horizontal

body, the massive appearance and the arched back. Lower—Pair

of Black East India Ducks. (Photographs from the Bureau

of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

Breast of Drake. The farther the claret color on

the breast of the drake extends down the better will

be the females secured from the mating. Drakes

which are deficient in the amount of claret on the

breast should therefore be thrown out as breeders. A

purple rump in drakes must be avoided as must black[Pg 25]

feathers over the rump as they tend to keep up too

dark a body color in the female. On the other hand

too bright or light a color in the male or exhibition

female will produce females which are too light in

color. Drakes with light olive colored bills must be

avoided as these will have a tendency to produce

offspring which show too much yellow in the females'

bills, and clear yellow bills constitute a disqualification.

In the females solid yellow bills, fawn

colored breasts and absence of penciling must be

avoided. Females which are dark or nearly black

over the rump are good breeders as they tend to

keep up the ground color of the body and tail.

The Rouen shows some tendency to fade in color.

This is evidenced first on the tips of the wings. The

fading will also show in the fluff of drakes. The

drakes of this breed and likewise of the Gray Call

and the Mallard show a peculiar behavior with respect

to the color of their plumage. About June 1

the drakes moult, losing their characteristic male

adult plumage and the new plumage is practically

that of the female. This female plumage is retained

until about October when they gradually regain their

normal winter male plumage. Young Rouens of both

sexes have female plumage until the last moult which

occurs at about four or five months of age, when the

drakes assume the adult male plumage. The sex

of the young Rouens can, however, be told by the

difference in the color of the bills.

Fig. 6. Upper—Rouen Drake showing summer plumage. At

this season the Rouen drake assumes a plumage resembling quite

closely that of the female. In the fall the drake again assumes the

normal male plumage. Lower—Rouen Duck. (Photographs from

the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

The Cayuga. The Cayuga is much like the other[Pg 26]

breeds of the meat class in general type or shape of

body showing good length, breadth and depth. It

is a very solid duck and weighs heavier than it looks.

The body carriage is slightly more upright than the

Rouen but not so much so as the Pekin. The back

line should be straight and any tendency toward an

arched back must be avoided. It is slightly smaller

than the Pekin, Aylesbury and Rouen, averaging

about a pound less.

In making the mating, size is important and

breeders should be selected which are up to standard

weights if possible. While this breed is not

kept very widely at the present time, nevertheless

it is an excellent market duck, dressing out into a

very plump yellow carcass in spite of its black plumage

which is a disadvantage in dressing. The

color should be a lustrous greenish black throughout,

being somewhat brighter in the drake than in

the duck. The duck is more likely to show a brownish

cast of plumage, particularly as she grows older.

It is hard to hold good black color with age. Moreover,

white or gray is apt to occur in the breast of females.

With age also a little white sometimes develops

on the back of the neck, around the eyes and

underneath the neck at the base of the bill. The

white which occurs in breast is more likely to come

in ducks and is not commonly found in the drakes.

In the drakes on the other hand, there is a tendency

for the white to come on the throat under the bill.

Drakes as a rule run truer in color and hold their[Pg 27]

color better than do the ducks. Where the white

mottling occurs in plumage with age one need not

hesitate to breed from these birds if they were of

good black color as young birds. The drakes of the

best color do not as a rule fade or become mottled to

any great extent with age. It is necessary to guard

against birds as breeders which have a rusty brown

lacing on the breast and under the wings, also those

which have a wing-bow laced with brown. There

is a tendency for the bill of drakes, which should

be black, to be too light or olive in color and this

tendency increases with age. Drakes with bills of

this color should be avoided as breeders. When

Cayugas are first hatched the baby ducks all show

a white breast.

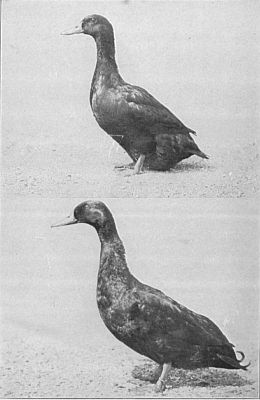

Fig. 7. Upper—Cayuga Duck. Lower—Cayuga Drake. (Photographs

from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of

Agriculture.)

The Call. The Call ducks are the bantams of the

duck race. There is always a tendency for them to

grow too large and this is especially true when they

have an opportunity to eat all they want as for example

when they are fed with the larger ducks.

They should not be fed too liberally and should be

given wheat or some other solid grain rather than

any mash. If there is a good pond of water to which

the Call ducks can have access they do not need to

be fed much of anything.

In breeding, the smallest individuals which are

suitable in other respects for breeders, should be

selected in order to keep down the size and offset

the tendency to breed larger in successive generations.

In type the Calls are practically miniature[Pg 28]

Pekins except that they should have a very short,

rather broad head and bill. The broad flat and

short bill and the round short head give the head an

appearance which is often described by the term

"button headed". In this breed avoid birds which

show arched backs. The body should have what is

known as a flatiron shape, that is, should be broad

at the shoulders and taper toward the tail. Too

deep keels and narrow shoulders should be avoided

as should also too long bills. Call ducks, together

with East Indias and Mallards should have their

wings clipped or be pinioned, that is, have the first

joint of one wing cut off, to prevent them from flying

away.

The Gray Call. The plumage of the Gray Call is

practically that of the Rouen although they are not

quite as good in color as a breed. There is more of

a tendency for some of the birds to run to dark and

others, especially the males, to run too light in color.

While they are likely to be well penciled the shade

of color is apt to be wrong. White in the flights and

under the wings must be guarded against as must

also absence of ribbon or wing bar in females. The

color of the plumage is likely to fade with age but

after the birds moult and secure their new plumage,

the color is usually higher again. In general the same

color characteristics hold true as with the Rouen

and the same defects must be guarded against.

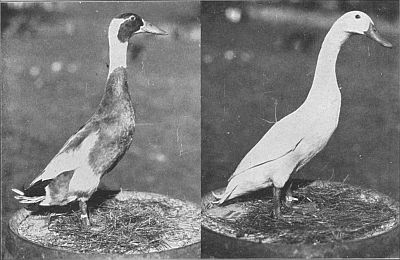

Fig. 8. Upper—Gray Call Drake. Lower—Gray Call Duck.

(Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department

of Agriculture.)

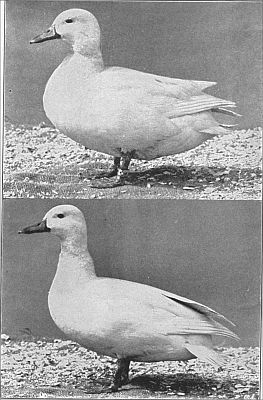

The White Call. This variety is, both in type

and color, practically a miniature Pekin except for[Pg 29]

the short, rather broad head and bill. They breed

very true in color and should be free from creaminess.

The same general defects must be watched

for and avoided as in the Pekin.

Fig. 9. Upper—White Call Duck. Lower—White Call Drake.

(Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department

of Agriculture.)

The Black East India. This is a black breed

which is small in size being a bantam duck like the

Call. As a matter of fact it is a miniature Cayuga.

The color should be black throughout and the same

color characteristics hold true as in the case of the

Cayuga. The same color defects must therefore be

guarded against, the worst one being white in the

breast of females especially. Avoid breeding from

a drake with a black bill as in this respect the breed

differs from the Cayuga since the bill of the duck

should be black but that of the drake should be very

dark green. Purple barring must be carefully selected

against.

The Muscovy. This breed differs in certain respects

very markedly from the other standard

breeds of ducks. They are long and broad in body

which is carried in a horizontal position but are not

so deep in keel as the Pekin, Aylesbury or Rouen.

The longest bodied young ducks will make the largest

individuals. The head should have feathers on

the top which can be elevated at will to form a

crest. Guard against breeders having smooth

heads, or in other words, lacking a crest.

The face is covered with corrugations or caruncles

and should be red in color. At the base of the upper

bill there is a sort of knob-like formation in the[Pg 30]

drake which serves as one of the distinguishing

characteristics between the duck and drake of this

breed. The more prominent the knob and the more

wrinkled or corrugated the face the better is the

specimen in this respect. The wings are long and

strong and these birds fly very well. They will

also climb fences. The drakes are quite pugnacious

and fight one another badly at times. They are especially

pugnacious when they have young.

This breed of ducks will often roost on roosts like

chickens or in the trees or on the barn. They do not

quack like other ducks and unlike other domesticated

breeds which moult two or three times a year, they

moult only once, taking longer to do so, usually

about 90 days, although the female may complete

her moult a little sooner. The period of incubation

for Muscovy eggs is longer, being from 33 to

35 days as compared to 28 days for other

breeds. In size the male and female differ

considerably as will be seen from the standard

weights given (See Page 14), the male being considerably

larger. These ducks lay well, the fertility

runs good, the eggs hatch well, and the little ducks

are hardy and easily raised. They are a broody

breed. The ducks will make their nests and hatch

out their eggs if allowed to do so and are excellent

mothers. Sometimes they will fly up and make their

nests in a hollow tree. A Muscovy duck can cover

properly about 20 eggs. In spite of the fact that

they fly well they are easily domesticated. It takes[Pg 31]

about two years for the males of this breed to fully

mature although the ducks get their full size when

one year of age. The Muscovy is perhaps the best

general purpose breed for a farm flock.

The extent and intensity of the red of the face increases

up to maturity and the redder the face the

better. The plumage of the Muscovy is not as downy

or oily as other breeds, the feathers being harder.

For this reason the birds are more apt to become

water soaked and to drown as a result when they

have not been accustomed to water in which to

swim. This is especially true of the drakes on account

of their large size and long wing feathers.

Muscovy ducks dress well, having a rich yellow skin,

and therefore make a good market duck, although

the difference in size of the duck and drake and the

dark pin feathers of the Colored variety are disadvantages

from a market standpoint. Select against

breeders which run small in size as there is more or

less of a tendency for this breed to decrease in size.

The Muscovy is long lived, specimens having been

known to breed until they were eight or ten years

of age.

The Colored Muscovy. Although the standard

calls for more or less white in different sections of

this variety, as a matter of fact breeders desire to

get the birds as dark as possible except for a very

small patch of white on the breast and a small patch

of white on the center of the wing. Indeed, birds

without the white on the breast and with very little on[Pg 32]

the wing are valuable breeders since there is a tendency

for too much white to occur in the plumage.

Occasionally all black birds occur and these can be

used to advantage in breeding when there is a tendency

toward too much white in plumage. Plumage

more than half white is a disqualification. The dark

plumage birds such as are wanted are very likely to

show considerable black or gypsy color in the face

which should be a good red. This must be selected

against insofar as possible. The nearly black or the

darkest birds are quite likely to show some white or

grizzling on the head. Grizzled or brownish penciled

feathers sometimes occur in various parts of

the plumage and must of course be guarded against

as the markings should be distinctly black and

white. The baby ducks of this variety are quite apt

to show considerable white although the best of

them come yellowish black. This variety tends to

run a little larger in size than the white variety

although the standard weights are the same for

both. Dun or chocolate colored ducks sometimes

come from Colored Muscovies while Blue Muscovies

can be produced by crossing the Colored and the

white varieties.

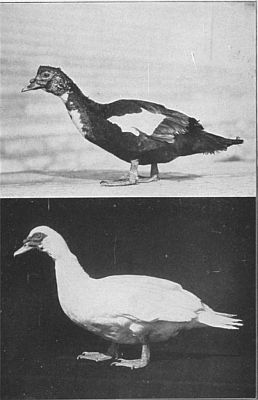

Fig. 10. Upper—Colored Muscovy Drake. Notice the partly

erect crest feather on top of the head. Lower—White Muscovy

Drake. Notice the long, horizontal body and the rough or carunculated

face. (Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry,

U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

The White Muscovy. This variety should have

pure white plumage throughout. Young Muscovies

of both sexes often have a patch of black on top of

the head up to the time they moult at maturity.

Since black disqualifies it is impossible to show

young ducks in this condition but these black feath[Pg 33]ers

usually come in white after the moult and such

birds need not therefore be discarded as breeders.

When it is desired to show young White Muscovies

which have black on the head it is customary to

pluck these black feathers a sufficient time before

the show so that the white feathers which come in

their place will have time to grow out. There is

little or no trouble with black or gypsy face in this

variety.

Fig. 11. Upper—Crested White Drake. Lower—Young White

Muscovy duck showing black on top of the head. This is not an

unusual occurrence and the black is lost when the bird gets its

mature plumage in the fall. (Photographs from the Bureau of

Animal Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

The Blue Swedish. In type and size this breed is

about the same as the Cayuga although perhaps

slightly more upstanding. In selecting the mating

it is important to use birds which are close to standard

weight as there is somewhat of a tendency for

the size to be too small. As its name indicates the

color is largely blue except for a white heart-shaped

patch or bib which should be present on the breast.

Sometimes this white extends along the underside

of the body from the under-bill almost to the vent.

Such birds are undesirable as breeders since they

show too much white. On the other hand birds lacking

a prominent white bib must also be avoided. Two

of the flight feathers should be white and birds

lacking these must be avoided. Guard against any

red, gray or black in any part of the plumage. Sometimes,

however, birds having more or less black

throughout the plumage are used as breeders for the

purpose of strengthening the blue color. Avoid any

tendency toward a ribbon on the wing-bow and also

birds that are too light, ashy or washed out in the

blue color.[Pg 34]

Sometimes birds show lines of white feathers

around the eyes and over the head and these should

be selected against as breeders as they are likely to

cause white splashing in the plumage. Yellow or

greenish bills must likewise be avoided since the first

of these is a disqualification. In general this variety

in breeding behaves insofar as color is concerned,

very much like the Blue Andalusian chicken.[3] The

young ducks when hatched are yellow or creamy

blue and from blue matings there are also produced

black and white ducklings. As in other colored

breeds and varieties, the dark pin feathers are somewhat

of a disadvantage from a market standpoint.

[3] For a detailed discussion of the behaviour of the Blue Andalusian

in breeding, the reader is referred to "The Mating

and Breeding of Poultry" by Harry M. Lamon and Rob R.

Slocum, published by the Orange Judd Publishing Company,

New York City.

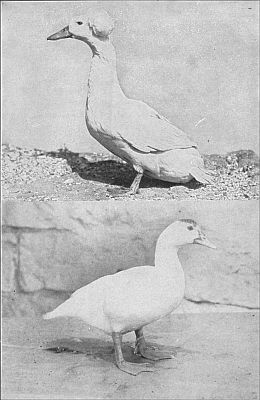

Fig. 12. Blue Swedish duck showing white flight feathers. The Standard calls for only two white

flights, but there is a decided tendency as shown here for more flights to be white. (Photograph from the

Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

The Crested White. Although not so large, this

breed is much like the Pekin but with body carried

more nearly horizontal and with a crest on the head.

The type varies considerably however, the principal

selection practiced having been for crest. The plumage

is white in color throughout. What is desired

in the crest is to have as large a one as possible,

round and perfect in form, and set squarely on the

head. Not infrequently crooked crests occur and

also double or split crests, that is to say, where the

crest is parted or divided. In some cases the crests

may even come treble, that is, split into three parts.

Entire absence of crest is by no means uncommon.[Pg 35]

In fact, it is considered a pretty good proportion if

one half of the ducks hatched have crests although

the matings vary considerably in this, occasionally

one producing practically 100% of the offspring

with crests. Avoid as breeders birds with small

crests, lopped crests, split crests or showing an absence

of crest. Avoid also breeders showing mottled

or green bills in females and black bean in the

bill of drakes.

The Buff. In type this breed is similar to the

Swedish. As will be seen from the standard weights

it is one of the medium sized breeds and makes a

very nice market bird as it dresses out into a nice

round fat carcass and is a good layer. In color the

birds of both sexes should be as uniform a buff as

possible except that the head and upper part of the

neck in the drake should be seal brown when in full

plumage. Color defects which are likely to be encountered

and which should be avoided are the

tendency for the head of the drake to run to a chestnut

color and for his neck to be too light or faded

out in color. Sometimes the head of the drake runs

too dark in color approaching a greenish black like

the head of the Rouen. This is of course undesirable.

The wings of both sexes are apt to run to light

or even in some cases, pure white flights. Blue wing

bars are sometimes shown and these must be carefully

avoided. Penciling such as is found in the

Fawn and White Runner sometimes occurs and since

it is a serious defect must be rigidly guarded against.[Pg 36]

Any tendency toward a white bib or a white ring

around the neck of both sexes must likewise be

avoided. Greenish or mottled bills must be avoided

in ducks which are to be used as breeders. Not much

trouble is experienced in the bill of drakes which as

a rule comes good. Any blue cast in the feathers on

the rump and back of both sexes must be selected

against. As a rule the females of this breed tend to

be better colored than the males. At certain periods

of the moult the head coloring of the drakes becomes

a good buff color and later when the moult is

complete, it changes to a copper color. When

hatched the ducklings are a creamy yellow.

Fig. 13. Pair of Buff Ducks—Drake on the right (Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry,

U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

The Runner. The type of this breed is quite different

from that of the other breed of ducks and

type is very important. The Runner wants to be decidedly

upstanding and to be very reachy. It should

have very slim slender lines. The neck should be

straight and the head should be carried at right

angles to the neck. The bill should be perfectly

straight on top and on a line with the skull showing

absolutely no tendency to be dished. The legs of

this breed are longer than those of other ducks and

this accounts for the fact that they run rather than

waddle when they move about. It is from this fact

that they get their name. They are very active and

are troublesome about crawling through fences.

They are good layers and non-sitters and they have

often been called the Leghorns of the duck family.

It must be remembered, however, that while they[Pg 37]

have the inherent ability to lay as well as hens they

will do this only when they receive proper feed and

care. It is quite useless to expect a high egg yield

from them when they are carelessly fed and improperly

housed and cared for. Avoid as breeders ducks

of both sexes that are too heavy behind, or in other

words, are too heavy-bottomed. Avoid birds which

are too short in legs. Avoid crooked or sharp backs.

Round heads must likewise be avoided.

The Fawn and White Runner. In this variety the

markings must be very distinct and definite. There

is a tendency which must be avoided for the head

to run to black instead of chestnut, especially in

males. It is likewise necessary to avoid females

which tend to show penciling on the sides of the

breast or on the wing-bows. These defects are apt

to be associated with colored flight feathers which

is also a defect to be avoided. Guard against too

much fawn extending up the neck from the body to

the head as the neck should be white in color. Too

dark tail coverts approaching a greenish black

sometimes occur and are undesirable. In type this

variety will not average quite as good as the White.

The White Runner. This variety is best in type

and it likewise runs good in color which should be

white throughout. Sometimes foreign color will be

shown in the back of females and this of course must

be avoided. Also avoid birds as breeders with green

or mottled bills.

Fig. 14. Penciled Runner Drake on left and White Runner Drake on right. (Photographs from the

Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.)

The Penciled Runner. In type this variety runs[Pg 38]

about the same as the Fawn and White. The color

combination is rather difficult to breed as it is hard

to get the good penciling desired in the female together

with the white markings. In general, in

breeding this variety there is a tendency to pay

more attention to type than to color. The penciling

is like that of the Rouen but lighter in color consisting

of a brown penciling on a fawn colored ground.

Avoid any grayish stippling on the breast of the

drake and also on the wing-bows. These defects

are likely to be associated with colored flights which

are undesirable. The colored portion of the head of

the drake is darker than that of the duck in this

variety. Avoid lack of white on the neck in both

sexes and avoid females which are lacking in penciling.

Preparing Ducks for the Show. Aside from selecting

the individuals which most nearly approach

the standard requirements there is very little which

can be done in the way of preparing the birds for

the show as these fowls are practically self-prepared.

For a period of at least a week or ten days

before they are shipped to the show those intended

for exhibition should be given access to a grass

range and also if possible to running water. The

grass range will keep them in good condition and

the running water will allow them to clean themselves.

Any broken feathers should be plucked at

least six weeks before the birds are to be shown in

order to allow the feathers time enough to grow out[Pg 39]

again. It must be remembered that most ducks

after getting in a good condition of flesh do not tend

to hold this for a very long period but soon grow

thinner again and will not take on fat the second

time for some little period.

Often there will be a difference in weight as high

as 3 pounds when a duck is in good condition and

after it has thinned. In order to have the ducks in

top form, therefore, it is necessary to bring them up

to flesh at the proper time. In order to bring ducks

which are to be exhibited up to standard weight,

they should be fed twice daily, for at least 10 days

before shipping, a grain mixture consisting of one

part corn and two parts oats. Give them all they

will eat of this mixture. With Runners and the small

breeds of ducks there is a danger of their putting on

too much weight if corn is used in the ration and it

is therefore best to give them oats alone. When

the birds are shipped to the show they are quite

likely to get their plumage soiled during the journey.

When this occurs fill a barrel about half full

of water. Then as the ducks are taken out of the

shipping coops take three of them at a time, put

them in the barrel and cover it over, leaving them

for a few minutes. When they are taken out they

will usually be clean.

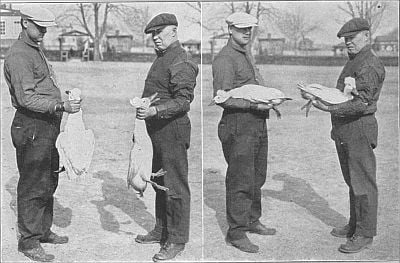

Catching and Handling Ducks

Ducks should never be caught by the legs which

are short and weak and are very likely to be injured.[Pg 40]

For the same reason they should never be carried by

the legs. Ducks should be caught by the neck,

grasping them just below the head. They can be

carried short distances without injury in this way

but it is not advisable to carry fat ducks by the neck

for any considerable distance. The best way to handle

them is to catch them by the neck, then carry

them on the arm with the legs in the hand just as

one would carry a chicken. See Fig. 15. A scoop net

about 18 inches in diameter and with a six foot handle

can also be used to excellent advantage in catching

ducks.

Fig. 15. Two methods of carrying ducks. (Photographs from the Bureau of Animal Industry, U. S.

Department of Agriculture.)

Packing and Shipping Hatching Eggs

Eggs for hatching must be shipped when they are

fresh as duck eggs tend to deteriorate in quality

quite rapidly. They may be shipped fairly long distances.

Shipment may be made either by express or

by Parcel Post. In order to prevent breakage and

to lessen the effects of the jar to which the eggs are

subjected during shipment, they must be carefully

packed. One of the best methods is to use an ordinary

market basket. Line the basket well on the

bottom and sides with excelsior. Wrap each egg in

paper and then wrap in excelsior so that there will

be a good thick cushion of excelsior between the

eggs and they will not be allowed to come in contact

with one another. Pack the eggs in the basket securely

standing them on end so that they cannot[Pg 41]

move or shift around. Cover the top of the eggs

with a thick layer of excelsior using enough so that

it runs up well above the sides of the basket. Over

the top sew a piece of strong cotton cloth. Instead

of sewing the cloth it can be pushed up under the

outside rim of the basket with a case knife, this

being quicker and equally as effective as sewing.

[Pg 42]

CHAPTER III

Commercial Duck Farming—Location—Estimate of

Equipment and Capital Necessary in Starting

the Business

Distribution. Commercial Duck farming is confined

very largely to the sections within easy shipping

distance of the larger cities. A great majority

of these farms are located about New York

City, particularly on Long Island. Some duck farms

are located on the Pacific Coast and a few commercial

plants are scattered about here and there

throughout the country. The size of these farms

ranges all the way from plants with an output of

5,000 or 10,000 ducklings up to those with an output

around 100,000 yearly.

Stock Used. The stock used on the commercial

duck plants of the United States consists exclusively

of the Pekin. The reasons for the use of this particular

breed are the fact that it has white plumage

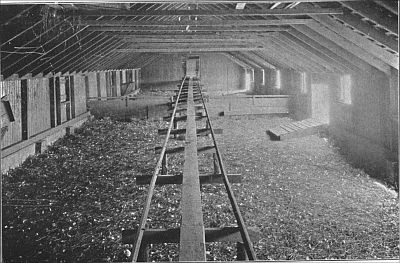

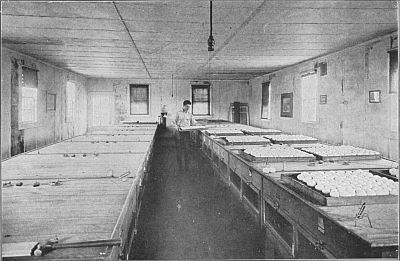

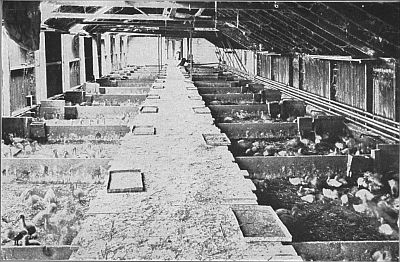

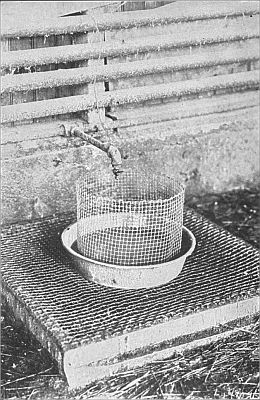

and therefore dresses out well, that it is of good