The Project Gutenberg eBook of Fish Populations, Following a Drought, in the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes Rivers of Kansas

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Fish Populations, Following a Drought, in the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes Rivers of Kansas

Author: James E. Deacon

Release date: December 30, 2010 [eBook #34787]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FISH POPULATIONS, FOLLOWING A DROUGHT, IN THE NEOSHO AND MARAIS DES CYGNES RIVERS OF KANSAS ***

[Cover]

Museum of Natural History

Fish Populations, Following a Drought,

In the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes Rivers

of Kansas

BY

JAMES EVERETT DEACON

(Joint Contribution from the State Biological Survey and

the Forestry, Fish, and Game Commission)

University of Kansas

Lawrence

1961

[Pg 359]

Museum of Natural History

Fish Populations, Following a Drought,

In the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes Rivers

of Kansas

BY

JAMES EVERETT DEACON

(Joint Contribution from the State Biological Survey and

the Forestry, Fish, and Game Commission)

University of Kansas

Lawrence

1961

[Pg 360]

University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, Henry S. Fitch,

Robert W. Wilson

Volume 13, No. 9, pp. 359-427, pls. 26-30, 3 figs.

Published August 11, 1961

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

PRINTED IN

THE STATE PRINTING PLANT

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1961

28-7576

[Pg 361]

Fish Populations, Following a Drought,

In the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes Rivers

of Kansas

BY

JAMES EVERETT DEACON

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 363 |

| Description of Neosho River | 366 |

| Description of Marais des Cygnes River | 367 |

| Methods | 368 |

| Electrical Fishing Gear | 368 |

| Seines | 369 |

| Gill Nets | 370 |

| Sodium Cyanide | 370 |

| Rotenone | 370 |

| Dyes | 370 |

| Determination of Abundance | 371 |

| Names of Fishes | 371 |

| Annotated List of Species | 371 |

| Fish-fauna of the Upper Neosho River | 405 |

| Description of Study-areas | 405 |

| Methods | 406 |

| Changes in the Fauna at the Upper Neosho Station, 1957 through 1959 | 407 |

| Local Variability of the Fauna in Different Areas at the Upper Neosho Station, 1959 | 409 |

| Temporal Variability of Fauna in the Same Areas | 411 |

| Population-Estimation | 412 |

| Movement of Marked Fish | 416 |

| Similarity of the Fauna at the Upper Neosho Station to the Faunas of Nearby Streams | 418 |

| Comparison of the Fish-faunas of the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes Rivers | 419 |

| Faunal Changes, 1957 Through 1959 | 420 |

| Conclusions | 423 |

| Acknowledgments | 425 |

| Literature Cited | 425 |

[Pg 362]

TABLES

| PAGE | |

| 1. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second (C. F. S.), Neosho River near Council Grove, Kansas | 364 |

| 2. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second, Neosho River near Parsons, Kansas | 364 |

| 3. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second, Marais des Cygnes River near Ottawa, Kansas | 364 |

| 4. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second, Marais des Cygnes River at Trading Post, Kansas | 365 |

| 5. Numbers and sizes of long-nosed gar | 372 |

| 6. Numbers and sizes of short-nosed gar | 374 |

| 7. Length-frequency of channel catfish from the Neosho River | 388 |

| 8. Length-frequency of freshwater drum | 402 |

| 9. Average number of individuals captured per hour | 402 |

| 10. Numbers of fish seen or captured per hour | 403 |

| 11. Numbers of occurrences and numbers counted | 404 |

| 12. Percentage composition of the fish fauna at the Upper Neosho station in 1957, 1958 and 1959, as computed from results of rotenone collections | 408 |

| 13. Relative abundance of fish | 410 |

| 14. Changes in numbers of individuals | 411 |

| 15. Data used in making direct proportion population-estimations | 414 |

| 16. Data on movement of marked fish | 416 |

[Pg 363]

INTRODUCTION

This report concerns the ability of fish-populations in the Neosho

and Marais des Cygnes rivers in Kansas to readjust to continuous

stream-flow following intermittent conditions resulting from the

severest drought in the history of the State.

The variable weather in Kansas (and in other areas of the Great

Plains) markedly affects its flora and fauna. Weaver and Albertson

(1936) reported as much as 91 per cent loss in the basal prairie

vegetative cover in Kansas near the close of the drought of the

1930's. The average annual cost (in 1951 prices) of floods in

Kansas from 1926 to 1953 was $35,000,000. In the same period the

average annual loss from the droughts of the 1930's and 1950's was

$75,000,000 (in 1951 prices), excluding losses from wind- and soil-erosion.

Thus, over a period of 28 years, the average annual flood-losses

were less than one-half the average annual drought-losses

(Foley, Smrha, and Metzler, 1955:9; Anonymous, 1958:15).

Weather conditions in Kansas from 1951 to 1957 were especially

noteworthy: 1951 produced a bumper crop of climatological events

significant to the economy of the State. Notable among these were:

Wettest year since beginning of the state-wide weather records in

1887; highest river stages since settlement of the State on the

Kansas River and on most of its tributaries, as well as on the Marais

des Cygnes and on the Neosho and Cottonwood. The upper

Arkansas and a number of smaller streams in western Kansas also

experienced unprecedented flooding (Garrett, 1951:147). This

period of damaging floods was immediately followed by the driest

five-year period on record, culminating in the driest year in 1956

(Garrett, 1958:56). Water shortage became serious for many

communities. The Neosho River usually furnishes adequate quantities

of water for present demands, but in some years of drought all

flow ceases for several consecutive months. In 1956-'57, the city

of Chanute, on an emergency basis, recirculated treated sewage for

potable supply (Metzler et al., 1958). The water shortage in many

communities along the Neosho River became so serious that a joint

project to pump water from the Smoky Hill River into the upper

Neosho was considered, and preliminary investigations were made.

If the drought had continued through 1957, this program might

have been vigorously promoted. Data on stream-flow in the Neosho

and Marais des Cygnes (1951-'59) are presented in Tables 1-4.

These severe conditions provided a unique opportunity to gain

insight into the ability of several species of fish to adjust to marked

[Pg 364]

changes in their environment. For this reason, and because of a

paucity of information concerning stream-fish populations in Kansas,

the study here reported on was undertaken.

Table 1. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second, Neosho River near

Council Grove, Kansas. Drainage Area: 250 Square Miles

| Water-year[A] | Average flow | Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 498.0 | 121,000 | 3.0 |

| 1952 | 82.1 | 4,850 | .7 |

| 1953 | 5.37 | 202 | .1 |

| 1954 | 8.53 | 2,720 | .1 |

| 1955 | 31.2 | 6,480 | 0 |

| 1956 | 10.1 | 5,250 | 0 |

| 1957 | 68.5 | 12,300 | 0 |

| 1958 | 131.0 | 5,360 | .8 |

| 1959 | 114.0 | 7,250 | 8.5 |

Table 2. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second, Neosho River near

Parsons, Kansas. Drainage Area: 4905 Square Miles.

| Water-year[B] | Average flow | Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 8,290 | 410,000 | 124.0 |

| 1952 | 2,021 | 20,500 | 20.0 |

| 1953 | 173 | 4,110 | .3 |

| 1954 | 430 | 27,900 | .1 |

| 1955 | 645 | 18,600 | 0 |

| 1956 | 180 | 6,170 | 0 |

| 1957 | 1,774 | 25,000 | 0 |

| 1958 | 3,092 | 27,200 | 78.0 |

| 1959 | 1,609 | 22,600 | 139.0 |

Table 3. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second, Marais des Cygnes

River Near Ottawa, Kansas. Drainage Area: 1,250 Square Miles.

| Water-year | Average flow | Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 2,113 | 142,000 | 25.0 |

| 1952 | 542 | 12,000 | .2 |

| 1953 | 36.5 | 2,690 | .2 |

| 1954 | 73.6 | 5,660 | .5 |

| 1955 | 75.7 | 5,240 | .7 |

| 1956 | 26 | 1,590 | .7 |

| 1957 | 442 | 11,200 | .7 |

| 1958 | 775 | 9,130 | 5.6 |

[Pg 365]

Table 4. Stream-flow in Cubic Feet per Second, Marais des Cygnes

River at Trading Post, Kansas. Drainage Area: 2,880 Square Miles.

| Water-year | Average flow | Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 5,489 | 148,000 | 36.0 |

| 1952 | 1,750 | 20,400 | 3.0 |

| 1953 | 261 | 7,590 | 0 |

| 1954 | 334 | 12,500 | 0 |

| 1955 | 786 | 16,100 | .2 |

| 1956 | 202 | 10,000 | 0 |

| 1957 | 871 | 14,700 | 0 |

| 1958 | 2,453 | 20,400 | 120.0 |

| [C]1959 | 750 | 10,900 | 3.4 |

[Pg 366]

DESCRIPTION OF NEOSHO RIVER

The Neosho River, a tributary of Arkansas River, rises in the

Flint Hills of Morris and southwestern Wabaunsee counties and

flows southeast for 281 miles in Kansas, leaving the state in the

extreme southeast corner (Fig.

1). With its tributaries (including

Cottonwood and Spring rivers)

the Neosho drains 6,285

square miles in Kansas and enters

the Arkansas River near

Muskogee, Oklahoma (Schoewe,

1951:299). Upstream from its

confluence with Cottonwood

River, the Neosho River has an

average gradient of 15 feet per

mile. The gradient lessens rapidly

below the mouth of the Cottonwood,

averaging 1.35 feet

per mile downstream to the State

line (Anonymous, 1947:12). The

banks of the meandering, well-defined

channel vary from 15 to

50 feet in height and support a

deciduous fringe-forest. The

spelling of the name originally

was "Neozho," an Osage Indian word signifying "clear water"

(Mead, 1903:216).

Fig. 1. Neosho and Marais des Cygnes

drainage systems. Dots and circles indicate collecting-stations.

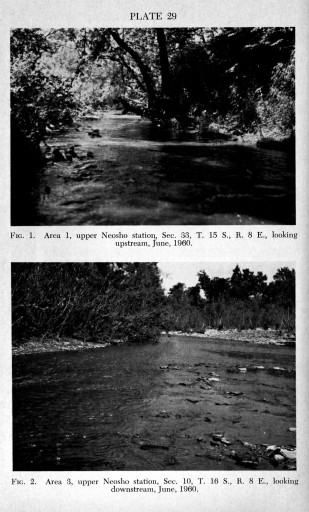

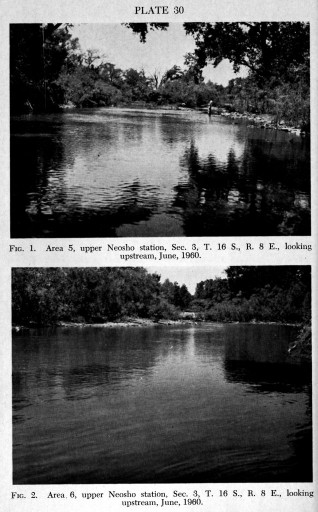

Neosho River, Upper Station.—Two miles north and two miles

west of Council Grove, Morris County, Kansas (Sec. 32 and 33, T.

15 S., R. 8 E.) (Pl. 28, Fig. 2, and Pl. 29, Fig. 1). Width 20 to 40

feet, depth to six feet, length of study-area one-half mile (one

large pool plus many small pools connected by riffles), bottom of

mud, gravel, and rubble. Muddy banks 20 to 30 feet high.

According to H. E. Bosch (landowner) this section of the river

dried completely in 1956, except for the large pool mentioned

above. This section was intermittent in 1954 and 1955; it again

became intermittent in the late summer of 1957 but not in 1958 or

1959.

A second section two miles downstream (on land owned by Herbert

White) was studied in the summer of 1959 (Sec. 3 and 10,

[Pg 367]

T. 16 S., R. 8 E.) (Pl. 29, Fig. 2 and Pl. 30, Figs. 1 and 2). This

section is 20 to 60 feet in width, to five feet in depth, one-half mile

in length (six small pools with intervening riffles bounded upstream

by a low-head dam and downstream by a long pool), having

a bottom of gravel, rubble, bedrock, and mud, and banks of

mud and rock, five to 20 feet in height.

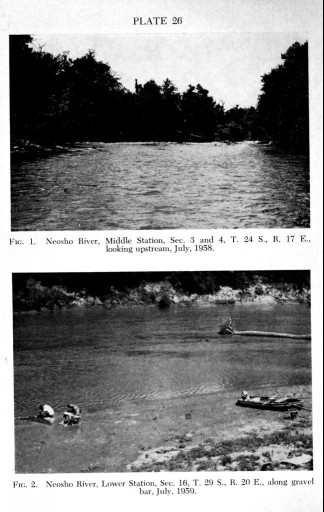

Neosho River, Middle Station.—One mile east and one and one-half

miles south of Neosho Falls, Woodson County, Kansas (Sec.

3 and 4, T. 24 S., R. 17 E.) (Pl. 26, Fig. 1). Width 60 to 70 feet,

depth to eleven feet, length of study-area two miles (four large

pools with connecting riffles), bottom of mud, gravel and rock.

Mud and rock banks 30 to 40 feet high.

According to Floyd Meats (landowner) this section of the river

was intermittent for part of the drought.

Neosho River, Lower Station.—Two and one-half miles west,

one-half mile north of Saint Paul, Neosho County, Kansas (Sec.

16, T. 29 S., R. 20 E.). Width 100 to 125 feet, depth to ten feet,

length of study-area one mile (two large pools connected by a

long rubble-gravel riffle), bottom of mud, gravel, and rock. Banks,

of mud and rock, 30 to 40 feet high (Pl. 26, Fig. 2).

This station was established after one collection of fishes was

made approximately ten miles upstream (Sec. 35, T. 28 S., R. 19 E.).

The second site, suggested by Ernest Craig, Game Protector, provided

greater accessibility and a more representative section of

stream than the original locality.

DESCRIPTION OF MARAIS DES CYGNES RIVER

The Marais des Cygnes River, a tributary of Missouri River,

rises in the Flint Hills of Wabaunsee County, Kansas, and flows

generally eastward through the southern part of Osage County

and the middle of Franklin County. The river then takes a southeasterly

course through Miami County and the northeastern part

of Linn County, leaving the state northeast of Pleasanton. With

its tributaries (Dragoon, Salt, Pottawatomie, Bull and Big Sugar

creeks) the river drains 4,360 square miles in Kansas (Anonymous,

1945:23), comprising the major part of the area between the watersheds

of the Kansas and Neosho rivers. The gradient from the

headwaters to Quenemo is more than five feet per mile, from

Quenemo to Osawatomie 1.53 feet per mile, and from Osawatomie

to the State line 1.10 feet per mile (Anonymous, 1945:24). The

total length is approximately 475 miles (150 miles in Kansas). The

[Pg 368]

river flows in a highly-meandering, well-defined channel that has

been entrenched from 50 to 250 feet (Schoewe, 1951:294). "Marais

des Cygnes" is of French origin, signifying "the marsh of the swans."

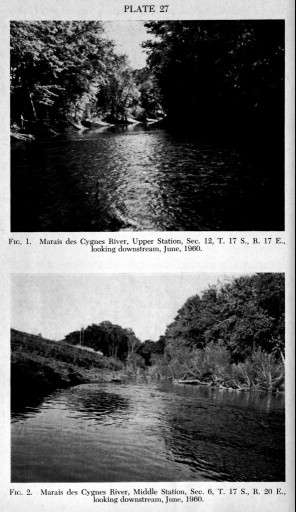

Marais des Cygnes River, Upper Station.—One mile south and

one mile west of Pomona, Franklin County, Kansas (Sec. 12, T.

17 S., R. 17 E.) (Pl. 27, Fig. 1). Width 30 to 40 feet, depth to

six feet, length of study-area one-half mile (three large pools with

short connecting riffles), bottom of mud and bedrock. Mud banks

30 to 40 feet high.

According to P. Lindsey (landowner) this section of the river

was intermittent for most of the drought. Flow was continuous

in 1957, 1958 and 1959.

There are four low-head dams between the upper and middle

Marais des Cygnes stations.

Marais des Cygnes River, Middle Station.—One mile east of

Ottawa, Franklin County, Kansas (Sec. 6, T. 17 S., R. 20 E.) (Pl.

27, Fig. 2). Width 50 to 60 feet, depth to eight feet, length of study-area

one-half mile (one large pool plus a long riffle interrupted by

several small pools), bottom of mud, gravel, and rock. Mud and

sand banks 30 to 40 feet high.

This section of the river was intermittent for much of the drought.

In the winter of 1957-'58 a bridge was constructed over this station

as a part of Interstate Highway 35. Because of this construction

many trees were removed from the stream-banks, the channel was

straightened, a gravel-bottomed riffle was rerouted, and silt was

deposited in a gravel-bottom pool.

Marais des Cygnes River, Lower Station.—At eastern edge of

Marais des Cygnes Wildlife Refuge, Linn County, Kansas (Sec.

9, T. 21 S., R. 25 E.). Width 80 to 100 feet, depth to eight feet,

length of study-area one-half mile (one large pool plus a long

riffle interrupted by several small pools), bottom of mud, gravel,

and rock. Mud banks 40 to 50 feet high.

This section of the river ceased to flow only briefly in 1956.

METHODS

Electrical Fishing Gear

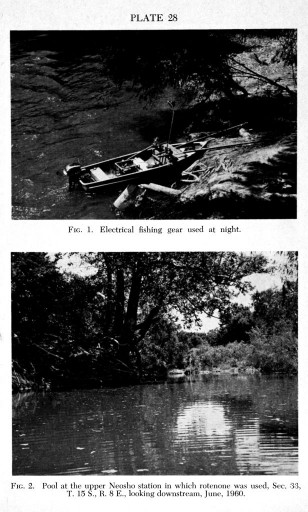

The principal collecting-device used was a portable (600-watt,

110-volt, A. C.) electric shocker carried in a 12-foot aluminum

boat. Two 2 × 2-inch wooden booms, each ten feet long,

were attached to the front of the boat in a "V" position so they

[Pg 369]

normally were two feet above the surface of the water. A

nylon rope attached to the tips of the booms held them ten feet

apart. Electrodes, six feet long, were suspended from the tip and

center of each boom, and two electrodes were suspended from the

nylon rope. The electrodes extended approximately four feet into

the water. Of various materials used for electrodes, the most satisfactory

was a neoprene-core, shielded hydraulic hose in sections

two feet long. These lengths could be screwed together, permitting

adjustment of the length of the electrodes with minimum effort. At

night, a sealed-beam automobile headlight was plugged into a six-volt

D. C. outlet in the generating unit and a Coleman lantern was

mounted on each gunwale to illuminate the area around the bow

and along the sides of the boat (Pl. 3a). In late summer, 1959, a

230-volt, 1500-watt generating unit, composed of a 115-volt, 1500-watt

Homelite generator was used. It was attached to a step-up

transformer that converted the current to 230 volts. The same

booms described above were used with the 230-volt unit, with

single electrodes at the tip of each boom.

A 5.5-horsepower motor propelled the boat, and the stunned fish

were collected by means of scap nets. Fishes seen and identified

but not captured also were recorded. On several occasions fishes

were collected by placing a 25-foot seine in the current and shocking

toward the seine from upstream.

The shocker was used in daylight at all six stations in the three

years, 1957-'59. Collections were made at night in 1958 and 1959

at the middle Neosho station and in 1959 at the lower Neosho

station.

Seines

Seines of various lengths (4, 6, 12, 15, 25 and 60 feet), with

mesh-sizes varying from bobbinet to one-half inch, were used. The

4-, 12-, and 25-foot seines were used in the estimation of relative

abundance by taking ten hauls with each seine, recording all species

captured in each haul, and making a total count of all fish captured

in two of the ten hauls. The two hauls to be counted were chosen

prior to each collection from a table of random numbers. Additional

selective seining was done to ascertain the habitats occupied

by different species.

Trap, Hoop, and Fyke Nets.—Limited use was made of unbaited

trapping devices: wire traps 2.5 feet in diameter, six feet long,

covered with one-inch-mesh chicken wire; hoop nets 1.5 feet to three[Pg 370]

feet in diameter at the first hoop with a pot-mesh of one inch; and a

fyke net three feet in diameter at the first hoop, pot-mesh of one

inch with wings three feet in length. All of these were set parallel

to the current with the mouths downstream. The use of trapping

devices was abated because data obtained were not sufficient to

justify the effort expended.

Gill Nets

Gill-netting was done mostly in 1959 at the lower Neosho station.

Use of gill nets was limited because frequent slight rises in the

river caused nets to collect excessive debris, with damage to the

nets.

Gill nets used were 125 feet long, six feet deep, with mesh sizes

of ¾ inch to 2½ inches. Nets, weighted to sink, were placed at right

angles to the current and attached at the banks with rope.

Sodium Cyanide

Pellets of sodium cyanide were used infrequently to collect fish

from a moderately fast riffle over gravel bottom that was overgrown

with willows, making seining impossible. The pellets were

dissolved in a small amount of water, a seine was held in place,

and the cyanide solution was introduced into the water a short

distance upstream from the seine, causing incapacitated fish to

drift into the seine. Most of these fish that were placed in uncontaminated

water revived.

Rotenone

Rotenone was used in a few small pools in efforts to capture

complete populations. This method was used to check the validity

of other methods, and to reduce the possibility that rare species

would go undetected. Rotenone was applied by hand, and applications

were occasionally supplemented by placing rotenone in a

container that was punctured with a small hole and suspended

over the water at the head of a riffle draining into the area being

poisoned. This maintained a toxic concentration in the pool for

sufficient time to obtain the desired kill. Rotenone acts more slowly

than cyanide, allowing more of the distressed fish to rise to the surface.

Dyes

Bismark Brown Y was used primarily at the upper Neosho station

to stain large numbers of small fish. The dye was used at a

dilution of 1:20,000. Fishes were placed in the dye-solution for[Pg 371]

three hours, then transferred to a live-box in midstream for variable

periods (ten minutes to twelve hours) before release.

Determination of Abundance

In the accounts of species that follow, the relative terms "abundant,"

"common," and "rare" are used. Assignment of one of these

terms to each species was based on analysis of data that are presented

in Tables 9-16, (pages 402, 403, 404, 405, 408, 410, 411, 414-415,

and 416). The number of fish caught per unit of effort with

the shocker (Table 10) and with seines (Table 11) constitute the

main basis for statements about the abundance of each species at all

stations except the upper Neosho station. Species listed in each Table

(10 and 11) are those that were taken consistently by the method

specified in the caption of the table; erratically, but in large numbers

at least once, by that method; and those taken by the method specified

but not the other method.

For the species listed in Table 10, the following usually applies:

abundant=more than three fish caught per hour; common=one

to three fish caught per hour; rare=less than one fish caught per

hour.

Tables 12-16 list all fish obtained at the upper Neosho station

by means of the shocker, seines, and rotenone.

Names of Fishes

Technical names of fishes are those that seem to qualify under

the International Rules of Zoological Nomenclature. Vernacular

names are those in Special Publication No. 2 (1960) of the American

Fisheries Society, with grammatical modifications required for

use in the University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural

History.

ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES

Lepisosteus osseus (Linnaeus)

Long-nosed Gar

The long-nosed gar was abundant at the lower and middle Neosho

stations and the lower Marais des Cygnes station. Numbers increased

slightly in the period of study, probably because of increased,

continuous flow. The long-nosed gar was not taken at

the upper Neosho station. At lower stations the fish occurred in

many habitats, but most commonly in pools where gar often were[Pg 372]

seen with their snouts protruding above the water in midstream.

Gar commonly lie quietly near the surface, both by day and by

night, and are therefore readily collected by means of the shocker.

Twice, at night, gar jumped into the boat after being shocked.

Young-of-the-year were taken at the middle and lower stations

on both the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes rivers, and all were near

shore in quiet water. Many young-of-the-year were seined at the

lower Neosho station on 18 June 1959, near the lower end of a

gravel-bar in a small backwater-area having a depth of one to three

inches, a muddy bottom, and a higher temperature than the mainstream.

Forty-three of these young gar averaged 2.1 inches in total

length (T.L.).

Comparison of sizes of long-nosed gar taken by means of the

shocker and gill nets at the lower and middle Neosho stations revealed

that: the average size at each station remained constant

from 1957 to 1959; the average size was greater at the lower than at

the middle station; and, with the exception of young-of-the-year,

no individual shorter than 13 inches was found at the middle station

and only one shorter than 16 inches was taken at the lower

station (Table 5).

Table 5. Numbers and Sizes of Long-nosed Gar Captured by Shocker

and Gill Nets at the Middle and Lower Neosho Stations in 1957, 1958

and 1959.

| Location | Date | Number | Average total length (inches) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Neosho | 1957 | 19 | 22.2 | 14-32 |

| Middle Neosho | 1958 | 57 | 22.2 | 14-40 |

| Middle Neosho | 1959 | 64 | 21.6 | 13-43 |

| Lower Neosho | 1957 | 14 | 29.4 | 9-45 |

| Lower Neosho | 1958 | 7 | 25.3 | 23-28 |

| Lower Neosho | 1959 | 107 | 26.2 | 16-43 |

Because collecting was intensive and several methods were used,

I think that the population of gars was sampled adequately. Wallen

(Fishes of the Verdigris River in Oklahoma, 1958:29 [mimeographed

copy of dissertation, Oklahoma State University]) took

large individuals in the mainstream of the Verdigris River in Oklahoma

and small specimens from the headwaters of some tributaries.

Because I took young-of-the-year at the lower Neosho station,

it is possible that long-nosed gar move upstream when small

and then slowly downstream to the larger parts of rivers as the fish

increase in size. This pattern of size-segregation, according to size

of river, merits further investigation.[Pg 373]

Ripe, spent, and immature long-nosed gar (38 males and 10 females)

were taken in three gill nets, set across the channel, 150

to 500 yards below a riffle, at the lower Neosho station on June 16,

17, and 18, 1959. On 23 June, 1959, 12 males and two females were

taken in gill nets set 50, 150, and 400 yards above the same riffle.

Operations with the shocker between 24 June and 10 July, 1959,

yielded 29 males and three females. The fish were taken from

many kinds of habitat in a three-mile section of the river.

Direction of movement as recorded from gill nets shows that of

67 gar taken, 45 had moved downstream and 22 upstream into the

nets. Only ten of the above gar were taken from the nets set above

the riffle; six of the ten were captured as they moved downstream

into the nets.

On one occasion I watched minnows swimming frantically about,

jumping out of the water, and crowding against the shore, presumably

to avoid a long-nosed gar that swam slowly in and out of

view. I have observed similar activity when gar fed in aquaria.

Stomachs of a few gar from the Neosho River were examined and

found to contain minnows and some channel catfish.

Long-nosed gar have a relatively long life span (Breder, 1936).

This longevity and their ability to gulp air probably insure excellent

survival through periods of adverse conditions. The population of

long-nosed gar probably would not be drastically affected even in

the event of a nearly complete failure of one or two successive

hatches. Maturity is attained at approximately 20 inches, total

length.

Collections at the middle Neosho station in 1958 indicate that

the long-nosed gar is more susceptible to capture at night than in

daytime (Table 9, p. 402).

Lepisosteus platostomus Rafinesque

Short-nosed Gar

Only one short-nosed gar was taken in 1957, at the lower station

on the Neosho River. In 1958 this species was taken at the lower

station on the Marais des Cygnes and in 1958 and 1959 at the lower

and middle stations on the Neosho. More common in the Neosho

than the Marais des Cygnes, L. platostomus occurs mainly in large

streams and never was taken in the upper portions of either river.

Although short-nosed gar were about equally abundant at the

middle and lower stations on the Neosho, the average size was[Pg 374]

greater at the lower station (Table 6). This kind of segregation

by size is shared with long-nosed gar, and was considered in the

discussion of that species. Short-nosed gar were taken only in quiet

water. Both species were collected most efficiently by means of gill

nets and shocker. While shocking, I saw many gar only momentarily,

as they appeared at the surface, and specific identification

was impossible. The total of all gar seen while shocking indicated

that gar increased in abundance from 1957 to 1959 (see Tables 5

and 6). Judging from the gar that were identified, the increase

was more pronounced in short-nosed gar than in long-nosed gar.

At the lower Neosho station in 1959, two ripe females and one

spent female were taken in gill nets (16, 23 and 17 June, respectively)

and were moving downstream when caught. No males

were taken in the nets. Subsequently, by means of the shocker

(26 June-8 July), two spent and two ripe males were captured

in quiet water of the mainstream that closely resembled areas in

which the gill nets were set. No females were taken by means

of the shocker.

Table 6. Numbers and Sizes of Short-nosed Gar Captured by Shocker

and Gill Nets at the Middle and Lower Neosho Stations in 1958 and

1959.

| Location | Date | Number | Average total length (inches) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Neosho | 1958 | 6 | 14.9 | 13.9-15.5 |

| Middle Neosho | 1959 | 9 | 13.6 | 11.0-16.0 |

| Lower Neosho | 1958 | 3 | 21.0 | 20.3-21.6 |

| Lower Neosho | 1959 | 5 | 21.3 | 18.0-24.5 |

Dorosoma cepedianum (LeSueur)

Gizzard Shad

Gizzard shad declined in abundance from 1957 to 1959. The

largest population occurred at the middle station on the Marais des

Cygnes in 1957. Shad were mainly in quiet water; often, when the

river-level was high, I found them predominately in backwaters

or in the mouths of tributary streams. Examination of nine individuals,

ranging in size from seven inches to 13.5 inches T. L., indicated

that maturity is reached at 10 to 11 inches T. L. Spawning

probably occurred in late June in 1959 ("ripe" female caught on

26 June); young-of-the-year were first recorded in mid-July.

Cycleptus elongatus (LeSueur)

Blue Sucker

The blue sucker was taken rarely in the Neosho River and not at

all in the Marais des Cygnes in my study. Cross (personal com[Pg 375]munication)

obtained several blue suckers in collections made in

the mainstream of the Neosho River in 1952; both young and adults

occupied swift, deep riffles. The species seemingly declined in

abundance during the drought, and at the conclusion of my study

(1959) had not regained the level of abundance found in 1952.

Ictiobus cyprinella (Valenciennes)

Big-mouthed Buffalo

Big-mouthed buffalo were found in quiet water at all stations,

but were rare. A ripe female, 21.5 inches long, was taken at the

lower station on the Neosho on 16 June, 1959.

Ictiobus niger (Rafinesque)

Black Buffalo

and

Ictiobus bubalus (Rafinesque)

Small-mouthed Buffalo

Black buffalo were not taken at the upper station on the Neosho

and were rare at other stations. Small-mouthed buffalo were taken

at all stations and were common in the lower portions of the two

streams. While the shocker was being used, buffalo were often

seen only momentarily, thereby making specific identification impossible;

both species were frequently taken together, and for this

reason are discussed as a unit. Both species maintained about

the same level of abundance throughout my study.

The two species were taken most often in the deeper, swifter

currents of the mainstream, but were sometimes found in pools,

creek-mouths and backwaters. On several occasions in the summer

of 1959, buffalo were seen in shallow parts of long, rubble riffles,

with the dorsal or caudal fins protruding above the surface. Ernest

Craig, game protector, said buffalo on such riffles formerly provided

much sport for gig-fishermen. He stated that the best catches

were made at night because the fish were less "spooky" then than

in daytime. In my collections made by use of the shocker, buffalo

were taken more frequently at night (Table 9, p. 402).

On 19 June, 1959, I saw many buffalo that seemed to be feeding

as they moved slowly upstream along the bottom of a riffle. The

two species, often side by side, were readily distinguishable underwater.

Small-mouthed buffalo appeared to be paler (slate gray)

and more compressed than the darker black buffalo. To test the[Pg 376]

reliability of underwater identifications, I identified all individuals

prior to collection with a gig. Correct identification was made

of all fish collected on 19 June. The smallest individual obtained

in this manner was 18.5 inches T. L. On 26 August, 1959, 16 small-mouthed

buffalo were captured and many more were seen while

the shocker was in use in the same riffle for one hour and ten minutes.

One small-mouthed buffalo was caught while the shocker

was being used in the pool below that riffle for one hour and

fifty minutes. No black buffalo were taken on 26 August.

Spawning by buffalo was not observed but probably occurred

in spring; all mature fish in my earliest collections (mid-June of

each year) were spent. Small-mouthed buffalo reach maturity at

approximately 14 inches T. L.

Carpiodes carpio carpio (Rafinesque)

River Carpsucker

River carpsucker were abundant throughout the study at all

stations. Adults were taken most frequently in quiet water, but

depth and bottom-type varied. The greatest concentrations occurred

in mouths of creeks during times of high water; occasionally,

large numbers were taken in a shallow backwater near the head of

a riffle at the middle Neosho station. River carpsucker feed on

the bottom but seem partly pelagic in habit. They were taken readily

by means of the shocker and gill nets at all depths. The population

of C. carpio in the Neosho River probably was depleted by

drought, although many individuals survived in the larger pools.

When stream-flow was restored, carpsucker probably moved rapidly

upstream but had a scattered distribution in 1957. Trautman

(1957:239) states that in the Scioto River, Ohio, river carpsucker

moved upstream in May and downstream in late August and early

September. Numbers found at the middle and lower Neosho stations

suggest similar movements in the Neosho River in 1957. In

midsummer they were common at the middle station but rare at

the lower station; however, they became abundant at the lower

station in November. The abundance in late fall at the lower

Neosho station might have resulted either from downstream migration

or from continued upstream movement into thinly populated

areas. No indication of seasonal movement was found in 1958 or

1959.

River carpsucker reach maturity at approximately 11 inches T. L.,[Pg 377]

and spawning occurs in May or June. A ripe male was taken from

a gravel-bottomed riffle, three

feet deep, at the middle station

on the Neosho station on 10 June

1959.

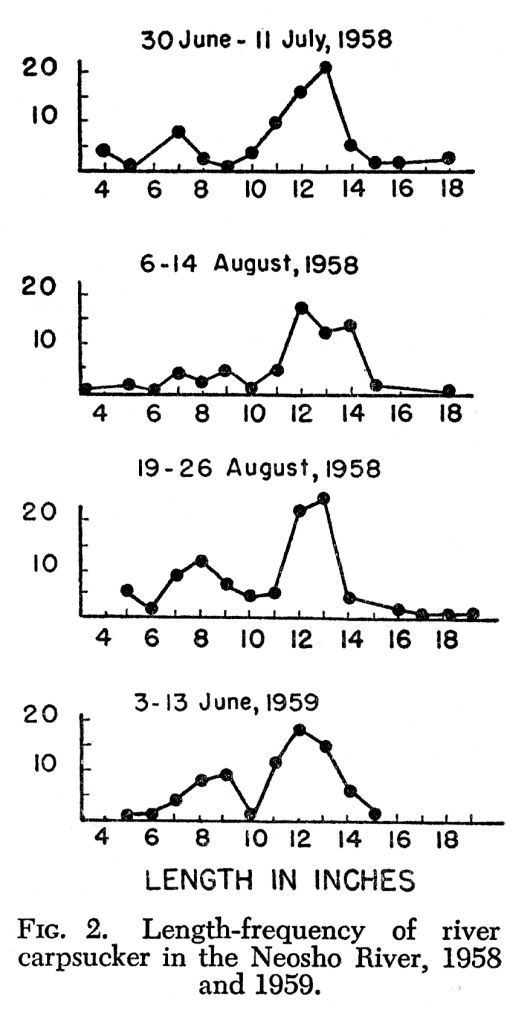

Fig. 2. Length-frequency of river

carpsucker in the Neosho River, 1958 and 1959.

The size-distribution of individuals

taken at the middle Neosho

station is presented in Fig.

2. The collection in early July

of 1958 indicates that one size-group

(probably the 1957 year-class)

had a median length of

approximately seven inches. The

modal length of this group was

nine inches in June, 1959. A

second, predominant size-group

(Fig. 2) seemed to maintain almost

the same median size

throughout all the collection periods,

although specimens taken

in the spring of 1959 were

slightly smaller than those obtained

in 1958. This apparent

stability in size may have been

due to an influx of the faster-growing

individuals from a

smaller size-group, coupled with mortality of most individuals more

than 14 inches in length.

Young-of-the-year were taken at every station. Extensive seining

along a gravel bar at the lower Neosho station indicated that the

young are highly selective for quiet, shallow water with mud bottom.

In these areas, young-of-the-year carpsucker were often

the most abundant fish.

River carpsucker were collected more readily by use of the

shocker after dark than in daylight (Table 9, p. 402).

Carpiodes velifer (Rafinesque)

High-finned Carpsucker

A specimen of Carpiodes velifer taken at the lower station on the

Neosho in 1958 provided the only record of the species in Kansas

since 1924. Many specimens, now in the University of Kansas[Pg 378]

Museum of Natural History, were taken from the Neosho River

system by personnel of the State Biological Survey prior to 1912.

The species has declined greatly in abundance in the past 50 years.

Moxostoma aureolum pisolabrum Trautman

Short-headed Redhorse

The short-headed redhorse occurred at all stations. It was

common at the middle and lower stations on the Neosho, rare at

the upper station on the Neosho, abundant at the upper station on

the Marais des Cygnes in 1957, and rare thereafter at all stations

on the Marais des Cygnes. Short-headed redhorse typically occur

in riffles, most commonly at the uppermost end where the water

flows swiftly and is about two feet deep. An unusually large concentration

was seen on 13 June, 1959, in shallow (six inches), fast

water over gravel bottom at the middle station on the Neosho River.

Thirty-nine individuals were marked by clipping fins at the

middle Neosho station in 1959. Four were recovered from one to

48 days later: two at the site of original capture (one 48 days

after marking), one less than one-half mile downstream, and one

about one mile downstream from the original site of capture.

At the middle Neosho station in 1958, this species was taken more

readily by use of the shocker at night than by day (Table 9, p. 402).

Moxostoma erythrurum (Rafinesque)

Golden Redhorse

The golden redhorse was abundant at the upper Neosho station,

rare at the middle Neosho station, and did not occur in collections

at other stations. This species was taken most frequently over

gravel- or rubble-bottoms in small pools below riffles, and was

especially susceptible to collection by means of the shocker.

Twenty-nine golden redhorse of the 1957 year-class, taken at

the upper Neosho station on 9 September 1958, were 6.2 to 8.6

inches in total length (average 7.4 inches); 26 individuals of the

same year-class caught on 21 August 1959 were 9.3 to 13.5 inches in

total length (average 10.9 inches).

Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus

Carp

The carp decreased in abundance from 1957 to 1959 at the upper

and middle Marais des Cygnes station and at the middle and lower

Neosho stations. Carp were more abundant in the Marais des[Pg 379]

Cygnes than in the Neosho, although the largest number in any

single collection was found in one pool at the upper Neosho station

in 1958.

Carp were taken most commonly in quiet water near brush or

other cover. At the middle Neosho station, collecting was most

effective between the hours of 6:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. and

least effective between 12:30 p.m. and 6:30 p.m. (Table 9, p. 402).

Ripe males were taken as early as 19 April (16.1 inches, 19.4 inches

T. L.) and as late as 30 July (16 inches T. L.) at the middle Neosho

station. Ripe females were taken as early as 19 April at the middle

Neosho station (19.2 inches T. L.) and as late as 7 July at the

lower Neosho station (16 inches T. L.). Young-of-the-year were

taken first at the middle Marais des Cygnes on 8 July 1957. They

were recorded on later dates at the upper Marais des Cygnes and

at the lower and middle Neosho stations.

Notemigonus crysoleucas (Mitchill)

Golden Shiner

The golden shiner was taken rarely at the upper Marais des

Cygnes station in 1958 and 1959 and at the middle Marais des

Cygnes station in 1957 and 1958. At the middle Neosho station

Notemigonus was seined from a pond that is flooded frequently

by the river, but never was taken in the mainstream.

Semotilus atromaculatus (Mitchill)

Creek Chub

The creek chub was taken only at the upper stations on both

rivers. It increased in abundance at the upper Neosho station from

1957 to 1959, and was not taken in the upper Marais des Cygnes

until 1959.

Hybopsis storeriana (Kirtland)

Silver Chub

A single specimen from the lower Marais des Cygnes station

provides the only record of the species from the Marais des Cygnes

system in Kansas, and is the only silver chub that I found in either

river in 1957-1959. The species is taken often in the Kansas and

Arkansas rivers.[Pg 380]

Hybopsis x-punctata Hubbs and Crowe

Gravel Chub

The gravel chub, present only at the lower and middle Neosho

stations, occupied moderate currents over clean (free of silt) gravel

bottom. The gravel chub was not taken in 1957, was rare at both

Neosho stations in 1958, became common at the lower Neosho

station in part of 1959, but was never numerous at the middle

Neosho station. Dr. F. B. Cross recorded the species as "rare"

in 1952 at a collection site near my middle Neosho station, but larger

numbers were taken then than in any of my collections at that

station. The population was probably reduced by drought, and

recovery was comparatively slow following restoration of flow.

Young-of-the-year and adults were common in collections from

riffles at the lower Neosho station from 1 July through 8 July, 1959.

I obtained only one specimen in intensive collections in the same

area on 25, 26, and 27 August. Seemingly the species had moved

off shallow riffles into areas not sampled effectively by seining.

Phenacobius mirabilis (Girard)

Sucker-mouthed Minnow

The sucker-mouthed minnow was common at the middle Marais

des Cygnes station but was not taken at the upper and lower stations

until 1959, when it was rare. At the middle and lower Neosho

stations this fish increased in abundance from 1957 to 1959; at the

upper station, sucker-mouthed minnows were not taken until 1959

when collections were made on the White farm. There, the species

was common immediately below a low-head dam, but was not

taken in extensive collections on the Bosch Farm in 1959.

The species was most common immediately below riffles, or in

other areas having clean gravel bottom in the current. On 5 June,

1959, many individuals were taken at night (11:30 p.m.) on a

shallow gravel riffle (four inches in depth) where none had been

found in a collection at 5:00 p.m. on the same date.

Young-of-the-year were taken at the lower Neosho station on 24

June, 1959, and commonly thereafter in the summer.

Notropis rubellus (Agassiz)

Rosy-faced Shiner

In 1958, the rosy-faced shiner was taken rarely at the lower stations

on both streams. This species is common in smaller streams

tributary to the lower portions of the two rivers, and probably[Pg 381]

occurs in the mainstream only as "overflow" from tributaries. Possibly,

during drought, rosy-faced shiners found suitable habitat in

the mainstream of Neosho and Marais des Cygnes rivers, but re-occupied

tributary streams as their flow increased with favorable

precipitation, leaving diminishing populations in the mainstream.

Notropis umbratilis (Girard)

Red-finned Shiner

The red-finned shiner, most abundant at the upper Neosho station,

occurred at all stations except the upper Marais des Cygnes.

This fish seems to prefer small streams, not highly turbid, having

clean, hard bottoms. It is a pool-dwelling, pelagic species.

Notropis camurus (Jordan and Meek)

Blunt-faced Shiner

The blunt-faced shiner was taken only in 1957, at the middle

Neosho station, where it was rare. This species, abundant in clear

streams tributary to the Neosho River (field data, State Biological

Survey) may have used the mainstream as a refugium during

drought. The few specimens obtained in 1957 possibly represent a

relict population that remained in the mainstream after flow in

tributaries was restored by increased rainfall.

Notropis lutrensis (Baird and Girard)

Red Shiner

The red shiner, abundant in 1952 (early stage of drought), was

consistently the most abundant fish in my collections in the Marais

des Cygnes and at the lower and middle Neosho stations. However,

the abundance declined from 1957 to 1959 at the two Neosho

stations. At the upper Neosho station the species was fourth in

abundance in 1957, and third in 1958 and 1959 (Table 12).

The red shiner is pelagic in habit and occurs primarily in pools,

though it frequently inhabits adjacent riffles. Collections by seining

along a gravel bar at the lower station showed this fish to be most

abundant in shallow, quiet water over mud bottom, or at the head

of a gravel bar in relatively quiet water. At the lower end of the

gravel bar in water one to four feet deep, with a shallow layer of silt

over gravel bottom and a slight eddy-current, red shiners were

replaced by ghost shiners or river carpsucker young-of-the-year as

the dominant fish.

Fifty-nine dyed individuals were released in an eddy at the lower[Pg 382]

end of a gravel bar at the middle Neosho station on 5 June, 1959.

Some of these fish still were present in this area when a collection

was made 30 hours later. No colored fish were taken in collections

from quiet water at the upper end of the gravel bar. A swift riffle

intervening between the latter area and the area of release may

have impeded their movement. Forty-six individuals, released at

the head of the same gravel bar on 10 June, 1959, immediately

swam slowly upstream through quiet water and were soon joined

by other minnows. These fish did not form a well-organized school,

but moved about independently, with individuals or groups variously

dropping out or rejoining the aggregation until all colored

fish disappeared about 50 feet upstream from the point of release.

Evidence of inshore movement at night was obtained on 8 June,

1959, in a shallow backwater, having gravel bottom, at the head

of a gravel bar at the middle Neosho station. A collection made in

the afternoon contained no red shiners, but they were abundant

in the same area after dark.

In Kansas, red shiners breed in May, June, and July. Minckley

(1959:421-422) described behavior that apparently was associated

with spawning. Because of its abundance, the red shiner is one

of the most important forage fishes in Kansas streams, and frequently

is used as a bait minnow.

Notropis volucellus (Cope)

Mimic Shiner

The mimic shiner was taken only rarely at the two lower Neosho

stations. This species, like N. camurus, is normally more common

in clear tributaries than in the Neosho River, and probably frequents

the mainstream only during drought.

Notropis buchanani Meek

Ghost Shiner

Field records of the State Biological Survey indicate that the

ghost shiner was common in the mainstream of the lower Neosho

River during drought. In 1957, the species was abundant at the

lower and middle stations on the Neosho River and at the lower

Marais des Cygnes station.

Collections at all stations show that the species has a definite

preference for eddies—relatively quiet water, but adjacent to the

strong current of the mainstream rather than in backwater remote[Pg 383]

from the channel. The bottom-type over which the ghost shiner

was found varied from mud to gravel or rubble.

Notropis stramineus (Cope)

Sand Shiner

The sand shiner was taken rarely in the Neosho and commonly

in the Marais des Cygnes in 1952. In my study the species occurred

at all stations, but not until 1959 at the upper and lower Neosho

stations. Sand shiners were found with equal frequency in pools

and riffles. Spawning takes place in June and July.

Pimephales tenellus tenellus (Girard)

Mountain Minnow

The mountain minnow was common at the lower and middle

Neosho stations throughout the period of study, and increased

in abundance from 1957 to 1959. It was taken only in 1959 at the

upper Neosho station, where it was rare. This species does not

occur in the Marais des Cygnes River. The largest numbers were

found in 1959 at the lower Neosho station, where this fish occurred

most commonly in moderate current over clean gravel bottom.

The mountain minnow, like Hybopsis x-punctata, was common in

late June and early July but few were found in late August, 1959.

The near-absence of this species in collections made in late August is

responsible for the apparent slight decline in abundance from 1957

to 1959, as shown in Table 11. Metcalf (1959) found mountain

minnows most commonly in streams of intermediate size in Chautauqua,

Cowley and Elk counties, Kansas. The predilection of this

species for permanent waters resulted in an increase in abundance

during my study. With continued flow, this species possibly will

decrease in abundance in the lower mainstream of the Neosho

River. I suspect that the species is, or will be (with continued

stream-flow), abundant in tributaries of intermediate size in the

Neosho River Basin.

Pimephales vigilax perspicuus (Girard)

Parrot Minnow

The parrot minnow was not taken in the Marais des Cygnes

River and was absent at the upper Neosho station until 1959.

This species was common at the lower and middle Neosho stations

throughout the period of study and increased in abundance from

1957 to 1959.[Pg 384]

At the lower Neosho station, this fish preferred slow eddy-current

over silt bottom, along the downstream portion of a gravel bar.

The parrot minnow was taken less abundantly in the latter part

of the summer, 1959, than in early summer, but the decline was

less than occurred in the mountain minnow.

Pimephales notatus (Rafinesque)

Blunt-nosed Minnow

The blunt-nosed minnow was common, and increased in abundance

in both rivers from 1957 to 1959. The largest numbers were

found at the upper Neosho station in 1959, and a large population

also was present at the lower Neosho station in 1959.

Pools having rubble bottom, bedrock, and small areas of mud

were preferred at the upper Neosho station. At the lower Neosho

station the fish was most common in quiet water at the lower end

of a gravel bar. The parrot minnow also was common in this

general area; nevertheless, these two species were seldom numerous

in the same seine-haul, indicating segregation of the two. The

blunt-nosed minnow was taken frequently in moderate current over

clean gravel bottom, especially in late summer, 1959, when P. notatus

increased in abundance as the mountain minnow decreased.

Pimephales promelas Rafinesque

Fat-headed Minnow

The fat-headed minnow was taken at all stations except at the

lower one on the Marais des Cygnes, and was most abundant at

the upper Neosho station. Intensive seining at the lower Neosho

station indicated that this species preferred quiet water and firm

mud bottom.

In the Neosho River in 1957 to 1959, habitats of the species of

Pimephales seemed to be as follows: Pimephales tenellus (mountain

minnow) occurred primarily in moderately flowing gravel

riffles in the downstream portions of the river. Pimephales vigilax

(parrot minnow) was mostly in the quiet areas having mud bottom

at the downstream end of gravel bars, and less commonly on adjacent

riffles, at the lower station. Pimephales notatus (blunt-nosed

minnow) had a wider range of habitats, occurring in quiet areas

and moderate currents both upstream and downstream. Pimephales

promelas (fat-headed minnow) occurred throughout both rivers

but was most abundant in the quiet water at the uppermost stations.[Pg 385]

Campostoma anomalum (Rafinesque)

Stoneroller

The stoneroller was most abundant at the upper Neosho station

and was not taken at the lower Marais des Cygnes station. This

fish increased in abundance from 1957 to 1959, but was never

common at the middle Marais des Cygnes or the middle and lower

Neosho stations.

The stoneroller prefers fast, relatively clear water over rubble

or gravel-bottom.

Ictalurus punctatus (Rafinesque)

Channel Catfish

The abundance of channel catfish was greatly reduced as a result

of the drought of 1952-1956. With the resumption of normal stream-flow

in 1957, the small numbers of adult channel catfish present in

the stream produced unusually large numbers of young. These

young of the 1957 year-class, which reached an average size of

about nine inches by September 1959, will provide an abundant

adult population for several years.

The reduction in number of channel catfish in streams can be

related to the changed environment in the drought. When stream

levels were low in 1953 (Tables 1-4), fish-populations were crowded

into a greatly reduced area. An example of these crowded conditions

was observed by Roy Schoonover, Biologist of the Kansas

Forestry, Fish and Game Commission, in October, 1953, when he

was called to rescue fish near Iola, Kansas. The Neosho River

had ceased to flow and a pool (less than one acre) below the city

overflow dam was pumped dry. Schoonover (personal communication)

estimated that 40,000 fish of all kinds were present in the

pool. About 30,000 of these were channel catfish, two inches to

14 inches long, with a few larger ones. Fish were removed in the

belief that sustained intermittency in the winter of 1953-1954

would result in severe winterkill. These conditions almost certainly

were prevalent throughout the basin.

In addition to winterkill, crowding probably resulted in a reduced

rate of reproduction by channel catfish, and by other species

as well. This kind of density-dependent reduction of fecundity is

known for many species of animals (Lack, 1954, ch. 7). In fish, it

is probably expressed by complete failure of many individuals to

spawn, coupled with scant survival of young produced by the adults

that do spawn. Reproductive failure of channel catfish in farm[Pg 386]

ponds, especially in clear ponds, is well known, and is often attributed

to a paucity of suitable nest-sites (Marzolf, 1957:22; Davis,

1959:10).

In the Neosho and Marais des Cygnes rivers, the intermittent

conditions prevalent in the drought resulted in reduced turbidity

in the remaining pools. Many spawning sites normally used by

channel catfish were exposed, and others were rendered unsuitable

because of the increased clarity of the water. In addition, predation

on young channel catfish is increased in clear water (Marzolf;

Davis, loc. cit.), and would of course be especially pronounced in

crowded conditions. The population was thereby reduced to correspond

to the carrying capacity of each pool in the stream bed.

The return of normal flow in 1957 left large areas unoccupied

by fish and the processes described above were reversed. The

expanded habitat favored spawning by nearly the entire adult

population, and conditions for survival of young were excellent.

As a result, a large hatch occurred in the summer of 1957. (Several

hundred small channel catfish were sometimes taken by use of the

shocker a short distance upstream from a 25-foot seine, set in a

riffle). Subsequent survival of the 1957 year-class has been good.

By 1959, few of the catfish spawned in 1957 had grown large enough

to contribute to the sport fishery, but they are expected to do so in

1960 and 1961.

The 1957 year-class was probably the first strong year-class of

channel catfish since 1952. Davis (1959:15) found that channel

catfish in Kansas seldom live longer than seven years. The 1952

year-class reached age seven in 1959. The extreme environmental

conditions to which these fish were subjected in drought caused a

higher mortality than would occur in normal times. The adult

population in the two rivers probably was progressively reduced

throughout the drought, and the reduction will continue until the

strong 1957 year-class replenishes it. For these reasons, fishing

success was poor in 1957-1959.

Juvenile channel catfish were more abundant in the Neosho than

in the Marais des Cygnes in 1958 and 1959, although both streams

supported sizable populations. In the Marais des Cygnes the upper

station had fewer channel catfish than the middle and lower stations.

In the Neosho, populations were equally abundant both upstream

and downstream. The habitat of channel catfish in streams

has been discussed by Bailey and Harrison (1948).

I found adults in various habitats throughout the stream, but[Pg 387]

most abundantly in moderately fast water at the lower and middle

Neosho stations. At the upper Neosho station where riffles are

shallow, yearlings and two-year-olds were numerous in many of

the small pools over rubble-gravel bottom. Cover was utilized

where present, but large numbers were taken in pools devoid of

cover. Young-of-the-year were nearly always taken from rubble- or

gravel-riffles having moderate to fast current at both upstream

and downstream stations.

Collections showed that young of 1957 were abundant on riffles

throughout the summer and until 17 November, 1957. Subsequent

collections were not made until 11 May, 1958, at which time 1957-class

fish still were abundant on riffles at the lower Neosho station;

on that date, the larger individuals were in deeper parts of the

riffles than were smaller representatives of the same year-class.

In a later collection (2 June, 1958), numbers present on the

riffles were greatly reduced and the larger individuals were almost

entirely missing. Some of the smaller individuals were still present

in the shallower riffle areas. Table 7 compares sizes of the individuals

obtained on 2 June with sizes collected from deep riffles

at the middle Neosho station on 7 June, 1958. The larger size of

the group present in deep riffles is readily apparent. The yearlings

almost completely disappeared from subsequent collections on

riffles.

A bimodal size-distribution of young-of-the-year was noted also

in 1958 and 1959; but, no segregation of the two sizes occurred

on riffles in summer. Marzolf (1957:25) recorded two peaks in

spawning activity in Missouri ponds. Two spawning periods may

account for the bimodal size distribution of young-of-the-year

observed in my study.

In 1959, young-of-the-year began to appear in the latter part of

June and became abundant by the first part of July. Individuals

as small as one inch T. L. were taken in gravel-bottomed riffles

on 1 July, 1959.

Yearling individuals at the lower and middle Neosho stations

showed a pronounced tendency to move into shallow, moderately

fast water over rubble or gravel bottom at night, where they were

nearly ten times more abundant than in daytime (Table 9). Adults

probably have the same pattern of daily movement as yearlings,

except that at night the adults move to deeper riffles. Bailey and

Harrison (1948:135-136) demonstrated that channel catfish feed

most actively from sundown to midnight.[Pg 388]

Channel catfish (especially two-year-olds and adults) were abundant

on a rubble-riffle during the day in some collections at the

lower Neosho station in 1959.

Table 7. Length-frequency of Channel Catfish from the Neosho River,

1957, 1958 and 1959. (Numbers in Vertical Columns Indicate the

Number of Individuals of a Certain Size Collected on That Date.)

| Length in inches | Nov. 2 1957 | June 2 1958 (shallow riffle) | June 7 1958 (deep riffle) | Sept. 9 1958 | Sept. 11 1959 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 1 | ||||

| 2.0 | 3 | ||||

| 2.5 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 3.0 | 4 | 11 | 3 | 4 | |

| 3.5 | 3 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 14 |

| 4.0 | 11 | 12 | 9 | ||

| 4.5 | 4 | 10 | 1 | ||

| 5.0 | 2 | 11 | 2 | ||

| 5.5 | 1 | 7 | 26 | ||

| 6.0 | 58 | 2 | |||

| 6.5 | 1 | 32 | 5 | ||

| 7.0 | 16 | 5 | |||

| 7.5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 8.0 | 22 | ||||

| 8.5 | 45 | ||||

| 9.0 | 81 | ||||

| 9.5 | 41 | ||||

| 10.0 | 21 | ||||

| 10.5 | 8 | ||||

| 11.0 | 4 | ||||

| 11.5 | 1 | ||||

| 12.0 | 3 | ||||

| 12.5 | 1 | ||||

| 13.0 | 1 |

Near the end of the spawning season in 1959, I found spawning

catfish at the lower Neosho station. Ripe females were taken between

9 June and 30 June, 1959; and, on 19 June I found a channel

catfish nest with eggs (water temp. 79° F.). The nest-site was a

hole in the base of a clay bank; the floor was clean gravel with a

small mound of gravel at the entrance. The nest-opening, five to

six inches in diameter, widened almost immediately into a chamber

about two and one-half feet long and one foot wide. Normally

the water was about six inches deep in the mainstream as it ran

over a riffle adjacent to the catfish nest. When I put my hand into

the opening the fish bit vigorously, but became quiescent when

I stroked its belly. I then felt the rounded gelatinous mass of eggs

on the bottom of the nest. On June 22 (water temp. 86° F.) the

fish was removed, struggling, from the nest, and returned to the

stream. The next day (23 June 1959, water temp. 84° F.) the eggs

had hatched and the young were in a swarm in the nest. The[Pg 389]

adult did not attempt to bite but left as soon as I put my hand into

the hole.

Marzolf (1957:25) reports that young remain in the nest from

seven to eight days after hatching. My seining records show a

marked increase in abundance of small young-of-the-year on the

first of July. Probably the time of hatching of the nest described

above correlated well with hatches of other nests.

One and sometimes two channel catfish were found in other

holes in the stream-bank or bottom. The fish occasionally attacked

my hand vigorously, but at other times remained quiet or left without

attacking. No other channel catfish eggs were found, although

one hole under a rock in the middle of the river had one or two

individuals in it each time it was checked until 11 July, 1959. A

local fisherman informed me of his belief that these holes are occupied

only in the spawning season.

Observations that I made in a pond owned by Dr. E. C. Bryan

of Erie indicated that channel catfish, when disturbed in the early

stages of guarding the eggs, either eat the eggs and abandon the

nest or leave the nest exposed to predation by other animals. In

the later stages of nesting, the fish, if removed, will return to guard

the nest. After the eggs hatch the guarding response probably

diminishes and the fish leaves the nest readily.

At the lower Neosho station, several "artificial" holes were dug

into the clay bank and two pieces of six-inch pipe were forced into

the bank. Nearly all these holes were occupied by catfish for a

short period in June; many of the holes were enlarged, either by

the current or by fish. I suspect that fish enlarged some holes, because

in the spawning season several males were observed that had

large abrasions atop their heads, around their lips, and to a lesser

extent on their sides. These could have been caused by butting

and scraping the sides, roof and floor of a hole. I found it possible

to enlarge the holes by rapidly moving my hand while it was inside

a hole.

The growth-rate of channel catfish in the Neosho was approximately

the same at all stations, and the large 1957 year-class grew

to an average size of about nine inches by mid-September, 1959

(Table 7). Channel catfish mature at a total length of 12 to 15

inches. Thus, most individuals of the 1957 year-class in the Neosho

River probably will mature in their fourth or fifth summer (1960

or 1961 spawning season).

The sizes attained by young-of-the-year in 1957 differed in the[Pg 390]

two rivers. Six hundred and thirty-three young taken in the Marais

des Cygnes River attained an average size of 4.7 inches (range

two to six inches) by mid-September. (Age was determined by

length-frequency and verified by examining cross-sections of fin-spines

from the larger individuals). One hundred and fifty young

from the Neosho River averaged 3.0 inches (range 2 to 3.7 inches)

on 2 November. Gross examination of the riffle-insect faunas indicated

a larger standing crop in the Neosho than in the Marais des

Cygnes River. Thus, the slower growth of young channel catfish

in the Neosho seemed not to be correlated with food supply. Bailey

and Harrison (1948:125-130) found that young channel catfish in

the Des Moines River, Iowa, fed almost exclusively on aquatic

insect larvae. My observations indicate that this is true in the

Neosho and Marais des Cygnes rivers also.

Young produced in 1958 in the Neosho River attained an average

total length of three inches by 26 August, and young produced in

1959 attained an average size of 3.5 inches by 11 September. Both

groups probably continued growth until October, and may have

averaged four inches total length at that time.

The 1958 and 1959 year-classes were much less abundant than

were the 1957 young. Therefore, it seems likely that the growth

of the 1957 young in the Neosho River was depressed because of

crowding. The 1959 year-class was larger than the small 1958

year-class, thus conforming to a general expectation that strong

year-classes will be followed by weak year-classes.

Reproduction by channel catfish in 1957 seemed greater in the

Neosho River than in the Marais des Cygnes River (Table 10); this

coincided with a greater change in volume of flow in the Neosho

River than in the Marais des Cygnes River (Tables 1-4). The

1957 year-class seemed more crowded, and grew more slowly, in the

Neosho than in the Marais des Cygnes River.

Ictalurus natalis (LeSueur)

Yellow Bullhead

Yellow bullhead were taken only at the middle station on the

Marais des Cygnes and upper station on the Neosho. The yellow

bullhead is more restricted to streams than is the black bullhead.

Both species decreased in abundance during a period of continuous

flow (1957 to 1959) following drought at the upper Neosho station.

Collections in 1958-'59 indicated an increase in average size.

Of four individuals marked and released at the upper Neosho sta[Pg 391]tion

in 1959, one was recaptured about three hours after being released.

It had not moved from the area of release.

Ictalurus melas (Rafinesque)

Black Bullhead

The black bullhead was abundant at the upper stations on each

river, especially in backwaters having mud-bottom. The species

was not taken in the mainstream of the lower and middle Neosho

stations, but was taken at the middle Neosho station in a pond

that is often flooded by the river. Although the fish was common

or abundant in nearly all pools at the upper Neosho station, it was

most abundant in one pool that had a bottom predominately of mud.

At the middle Marais des Cygnes station, 109 individuals were

collected and fin-clipped on 8, 9 and 24 July 1957. Three of the

19 marked on 8 July were recaptured in the same area on 9 July.

The area was poisoned on 13 September, 1957, and 130 black

bullhead were taken, none of which had been marked.

In 1959, 96 black bullhead were taken at the upper Neosho station

(five in Area 1 and 91 at the White Farm). In these collections,

25 were marked (fin-clipped or dyed) and six were recaptured.

Four of the six had not left the area of capture one and two

days after being released. The fifth fish recaptured was one of

five individuals that had been displaced one pool downstream.

When recaptured seven days later, this fish had moved upstream

over two steep riffles (two to three inches deep, 75 feet and 166

feet long) past the site of original capture to the next pool. The

sixth fish, marked at the same time but returned to the original

pool, was recaptured nine days after original capture and had

moved upstream over a long riffle (two to three inches deep, 166

feet long) and a short riffle into the second pool above the original

site of its capture.

Rotenone was applied to a small (.04 acre-feet) backwater ditch

having a soft mud bottom at the upper Marais des Cygnes station

on 25 July, 1957; 1526 black bullhead, one green sunfish and one

white crappie were collected. A sample of 60 bullhead averaged

4.6 inches T.L. (range 3.5 to 6.6 inches) and 540 individuals averaged

.7 ounce each. These fish probably represented the 1956 year-class.

The upper Neosho station had a large population of black bullhead,

strongly dominated by fish less than four inches T. L. (range

1.5 to 3.8 inches), in the spring of 1957. Most were approximately[Pg 392]

two inches T. L. and probably represented the 1956 year-class.

Growth, according to length-frequency, following restoration of

stream-flow, shows a regular increase in length of this dominant

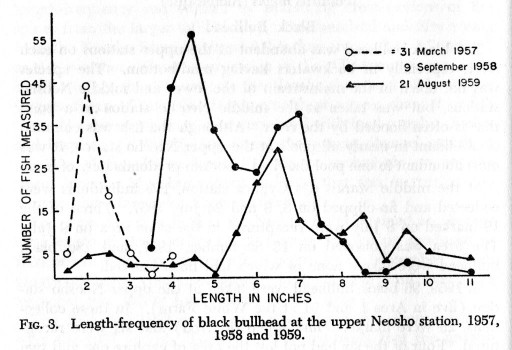

1956 year-class (Fig. 3). A scarcity of young, especially in 1958

and 1959, is apparent in Fig. 3. This may be due to the fact that

a strong year-class usually is followed by one or several weak

year-classes. However, it more probably reflects the fact that

black bullhead are characteristically pond fish, and as such are

not so well adapted to reproduction in flowing streams as are many

other species. Metcalf (1959) found this species most abundantly

in the intermittent headwaters of Walnut River and Grouse Creek

in Cowley County, Kansas.

Fig. 3. Length-frequency of black bullhead at the upper Neosho station, 1957,

1958 and 1959.

Pylodictis olivaris (Rafinesque)

Flat-headed Catfish

The flathead is the largest sport-fish occurring in Kansas. Several

weighing more than 40 pounds are caught from streams each year,

and the species reportedly attains sizes in excess of one hundred

pounds. Several aspects of the biology of the flathead in Kansas

have been discussed by Minckley and Deacon (1959).

The abundance of flathead declined slightly from 1957 through

1959, counting fish of all sizes. This trend is attributable to a

large hatch in 1957; the 1957 year-class strongly dominated the[Pg 393]

population throughout my study. Natural mortality in that year-class

was compensated by increased average size of the individuals

(to six inches in autumn, 1958, and 11 inches in autumn, 1959).

The numbers of flathead caught at the upper stations on the

Neosho and Marais des Cygnes rivers differed from the general

trend in that the species was rare in 1957 and increased slightly

by 1959. Flathead are most numerous in large streams, and in the

drought they probably were almost extirpated from the headwaters.

After 1957, continuous flow and increased volume of flow

were accompanied by a gradual increase in numbers of flathead

in the upstream parts of the two rivers. The species was most

abundant at the middle and lower Neosho stations, where 10.5

per cent of all fish shocked in 1957 and 1958 were P. olivaris.

The habitat of the flathead varied with size of the individuals.

Young-of-the-year inhabited swift riffles having rubble bottom;

individuals four to 12 inches in total length were distributed

throughout the stream; those more than 12 inches in total length

were most commonly in pools in association with cover (rocks, or

drifts of fallen timber).

Male flathead mature at 15 to 18 inches total length, females at

18 to 20 inches. The spawning season in 1959 probably began

in early June and extended to mid-July. I attempted to find spawning

fish on 19 June and for one month thereafter. On 19 June

nine holes were dug into a 75-yard section of a clay bank adjacent

to a long, shallow, rubble riffle. A flathead was first found in one

of these holes on 22 June, and others were frequently found in

this and one other hole until mid-July. Although channel catfish

were often found in nearby holes, that species was never present

in the two holes used by flatheads. The holes occupied by flathead

(as well as those used by channel catfish) characteristically had

silt-free gravel bottoms and a ridge of clean gravel across the entrance.

A nest containing a flathead and eggs was located on 11 July.

In checking the hole I first put my foot into the entrance, then slowly

advanced my hand into the hole, feeling along the bottom with

my fingers until they entered the open mouth of a large catfish.

I backed off slowly and then felt beneath the fish. The fish was

directly above the egg-mass, seemingly touching the eggs with its

belly. As I touched the front of the egg-mass the fish struck

viciously, taking my entire fist into its mouth. It continued striking

until I removed my hand from the hole after obtaining a small[Pg 394]

sample of eggs, which proved to be in an early stage of development

(no vascularization evident).

When the nest was checked again on 13 July the eggs and fish

were gone. As in the case of channel catfish, I suspect that disturbance

of a flathead in the early stages of guarding the nest

results in destruction of the nest either by the guardian fish or by

predation resulting from its absence.

The hole occupied by the above fish was one that I had dug

seven to nine inches in diameter and extending two and one-half to

three feet into the bank. At the time this fish occupied the hole

its depth was approximately the same as originally, but the entrance

had been enlarged to 14 inches in diameter, and the chamber

widened to 32 inches. The holes were checked later in the summer

and all were heavily silted or had been undercut by action of the

current.

The number of flathead of catchable size was not reduced as

severely during my study as was the number of large channel catfish.

Flathead have a longer life-span than channel catfish; therefore,

it is not surprising that, of flathead and channel catfish that

survived the drought, a higher proportion of flathead persisted

throughout the next three years, in which my study was made. In

drought, when fish were concentrated in residual pools, the piscivorous

(fish eating) habit of flatheads may have favored their

survival.

The growth rate of flathead taken from the Neosho River in

1957 and 1958 was reported by Minckley and Deacon (1959:351-352).

Individuals hatched in 1955 and 1956 and collected in 1957

had attained average sizes of 9.5 inches and 4.8 inches, respectively,

by the end of the 1956 growing-season.