The Project Gutenberg eBook of Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 2, No. 3

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 2, No. 3

Author: Various

Release date: November 21, 2009 [eBook #30511]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Anne Storer, some

images courtesy of The Internet Archive and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRDS, ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY, VOL. 2, NO. 3 ***

Transcriber’s Note:

Title page added.

BIRDS

A MONTHLY SERIAL

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY

DESIGNED TO PROMOTE

KNOWLEDGE OF BIRD-LIFE

VOLUME II.

CHICAGO

Nature Study Publishing Company

copyright, 1897

by

Nature Study Publishing Co.

chicago.

[Pg 81]

BIRDS.

Illustrated by COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY.

BIRD SONG.

How songs are made

Is a mystery,

Which studied for years

Still baffles me.

—R. H. Stoddard.

OME birds are poets and

sing all summer,” says

Thoreau. “They are the

true singers. Any man

can write verses in the

love season. We are most interested

in those birds that sing for the love of

music, and not of their mates; who

meditate their strains and amuse

themselves with singing; the birds

whose strains are of deeper sentiment.”

Thoreau does not mention by name

any of the poet-birds to which he

alludes, but we think our selections

for the present month include some of

them. The most beautiful specimen

of all, which is as rich in color and

“sun-sparkle” as the most polished

gem to which he owes his name, the

Ruby-throated Humming Bird, cannot

sing at all, uttering only a shrill

mouse-like squeak. The humming

sound made by his wings is far more

agreeable than his voice, for “when

the mild gold stars flower out” it announces

his presence. Then

“A dim shape quivers about

Some sweet rich heart of a rose.”

He hovers over all the flowers that

possess the peculiar sweetness that he

loves—the blossoms of the honeysuckle,

the red, the white, and the

yellow roses, and the morning glory.

The red clover is as sweet to him as

to the honey bee, and a pair of them

may often be seen hovering over the

blossoms for a moment, and then disappearing

with the quickness of a

flash of light, soon to return to the

same spot and repeat the performance.

Squeak, squeak! is probably their call

note.

Something of the poet is the Yellow

Warbler, though his song is not quite

as long as an epic. He repeats it a

little too often, perhaps, but there is

such a pervading cheerfulness about

it that we will not quarrel with the

author. Sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet-sweeter-sweeter!

is his frequent contribution

to the volume of nature, and

all the while he is darting about the

trees, “carrying sun-glints on his back

wherever he goes.” His song is appropriate

to every season, but it is in

the spring, when we hear it first, that

it is doubly welcome to the ear. The

grateful heart asks with Bourdillon:

“What tidings hath the Warbler heard

That bids him leave the lands of summer

For woods and fields where April yields

Bleak welcome to the blithe newcomer?”

The Mourning Dove may be called

the poet of melancholy, for its song

is, to us, without one element of cheerfulness.

Hopeless despair is in every

note, and, as the bird undoubtedly

does have cheerful moods, as indicated

by its actions, its song must be appreciated

only by its mate. Coo-o, coo-o!

suddenly thrown upon the air and

resounding near and far is something

hardly to be extolled, we should think,

and yet the beautiful and graceful

Dove possesses so many pretty ways

that every one is attracted to it, and

the tender affection of the mated pair

[Pg 82]

is so manifest, and their constancy so

conspicuous, that the name has become

a symbol of domestic concord.

The Cuckoo must utter his note in

order to be recognized, for few that

are learned in bird lore can discriminate

him save from his notes. He

proclaims himself by calling forth his

own name, so that it is impossible to

make a mistake about him. Well,

his note is an agreeable one and has

made him famous. As he loses his

song in the summer months, he is

inclined to make good use of it when

he finds it again. English boys are

so skillful in imitating the Cuckoo’s

song, which they do to an exasperating

extent, that the bird himself may

often wish for that of the Nightingale,

which is inimitable.

But the Cuckoo’s song, monotonous

as it is, is decidedly to be preferred to

that of the female House Wren, with its

Chit-chit-chit-chit, when suspicious or in

anger. The male, however, is a real

poet, let us say—and sings a merry

roulade, sudden, abruptly ended, and

frequently repeated. He sings, apparently,

for the love of music, and is

as merry and gay when his mate is

absent as when she is at his side,

proving that his singing is not solely

for her benefit.

So good an authority as Dr. Coues

vouches for the exquisite vocalization

of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet. Have

you ever heard a wire vibrating? Such

is the call note of the Ruby, thin and

metallic. But his song has a fullness,

a variety, and a melody, which, being

often heard in the spring migration,

make this feathered beauty additionally

attractive. Many of the fine

songsters are not brilliantly attired,

but this fellow has a combination of

attractions to commend him as worthy

of the bird student’s careful attention.

Of the Hermit Thrush, whose song

is celebrated, we will say only,

“Read everything you can find about him.”

He will not be discovered easily, for

even Olive Thorne Miller, who is presumed

to know all about birds, tells of

her pursuit of the Hermit in northern

New York, where it was said to be

abundant, and finding, when she

looked for him, that he had always

“been there” and was gone. But one

day in August she saw the bird and

heard the song and exclaimed:

“This only was lacking—this crowns my summer.”

The Song Sparrow can sing too, and

the Phoebe, beloved of man, and the

White-breasted Nuthatch, a little.

They do not require the long-seeking

of the Hermit Thrush, whose very

name implies that he prefers to flock

by himself, but can be seen in our

parks throughout the season. But the

Sparrow loves the companionship of

man, and has often been a solace to

him. It is stated by the biographer of

Kant, the great metaphysician, that

at the age of eighty he had become

indifferent to much that was passing

around him in which he had formerly

taken great interest. The flowers

showed their beautious hues to him in

vain; his weary vision gave little heed

to their loveliness; their perfume

came unheeded to the sense which

before had inhaled it with eagerness.

The coming on of spring, which he

had been accustomed to hail with

delight, now gave him no joy save

that it brought back a little Sparrow,

which came annually and made its

home in a tree that stood by his

window. Year after year, as one

generation went the way of all the

earth, another would return to its

birth-place to reward the tender care

of their benefactor by singing to him

their pleasant songs. And he longed

for their return in the spring with “an

eagerness and intensity of expectation.”

How many provisions nature has

for keeping us simple-hearted and

child-like! The Song Sparrow is one

of them.

—C. C. Marble.

[Pg 83]

summer yellow-bird.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 85]

THE YELLOW WARBLER.

N a recent article Angus Gaines

describes so delightfully some

of the characteristics of the

Yellow Warbler, or Summer

Yellow-bird, sometimes called

the Wild Canary, that we are tempted

to make use of part of it. “Back and

forth across the garden the little yellow

birds were flitting, dodging

through currant and gooseberry

bushes, hiding in the lilacs, swaying

for an instant on swinging sprays of

grape vines, and then flashing out

across the garden beds like yellow

sunbeams. They were lithe, slender,

dainty little creatures, and were so

quick in their movements that I could

not recognize them at first, but when

one of them hopped down before me,

lifted a fallen leaf and dragged a cutworm

from beneath it, and, turning

his head, gave me a sidewise glance

with his victim still struggling in his

beak, I knew him. His gay coat was

yellow without the black cap, wings,

and tail which show in such marked

contrast to the bright canary hue of

that other yellow bird, the Gold-finch.

“Small and delicate as these birds

are, they had been on a long journey

to the southward to spend the winter,

and now on the first of May, they had

returned to their old home to find the

land at its fairest—all blossoms, buds,

balmy air, sunshine, and melody. As

they flitted about in their restless way,

they sang the soft, low, warbling trills,

which gave them their name of Yellow

Warbler.”

Mrs. Wright says these beautiful

birds come like whirling leaves, half

autumn yellow, half green of spring,

the colors blending as in the outer

petals of grass-grown daffodils.

“Lovable, cheerful little spirits, darting

about the trees, exclaiming at each

morsel that they glean. Carrying

sun glints on their backs wherever

they go, they should make the

gloomiest misanthrope feel the season’s

charm. They are so sociable and

confiding, feeling as much at home in

the trees by the house as in seclusion.”

The Yellow-bird builds in bushes,

and the nest is a wonderful example

of bird architecture. Milkweed, lint

and its strips of fine bark are glued to

twigs, and form the exterior of the

nest. Its inner lining is made of the

silky down on dandelion-balls woven

together with horse-hair. In this

dainty nest are laid four or five creamy

white eggs, speckled with lilac tints

and red-browns. The unwelcome egg

of the Cow-bird is often found in the

Yellow-bird’s nest, but this Warbler

builds a floor over the egg, repeating

the expedient, if the Cow-bird continues

her mischief, until sometimes a

third story is erected.

A pair of Summer Yellow-birds, we

are told, had built their nest in a wild

rose bush, and were rearing their

family in a wilderness of fragrant

blossoms whose tinted petals dropped

upon the dainty nest, or settled upon

the back of the brooding mother.

The birds, however, did not stay “to

have their pictures taken,” but their

nest may be seen among the roses.

The Yellow Warbler’s song is

Sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet-sweeter-sweeter:

seven times repeated.

[Pg 86]

THE HERMIT THRUSH.

N John Burroughs’ “Birds and

Poets” this master singer is

described as the most melodious

of our songsters, with the exception

of the Wood Thrush,

a bird whose strains, more than any

other’s, express harmony and serenity,

and he complains that no merited

poetic monument has yet been reared

to it. But there can be no good

reason for complaining of the

absence of appreciative prose concerning

the Hermit. One writer says:

“How pleasantly his notes greet the

ear amid the shrieking of the wind

and the driving snow, or when in a

calm and lucid interval of genial

weather we hear him sing, if possible,

more richly than before. His song

reminds us of a coming season when

the now dreary landscape will be

clothed in a blooming garb befitting

the vernal year—of the song of the

Blackbird and Lark, and hosts of other

tuneful throats which usher in that

lovely season. Should you disturb

him when singing he usually drops

down and awaits your departure,

though sometimes he merely retires to

a neighboring tree and warbles as

sweetly as before.”

In “Birdcraft” Mrs. Wright tells us,

better than any one else, the story of

the Hermit. She says: “This spring,

the first week in May, when standing

at the window about six o’clock in the

morning, I heard an unusual note, and

listened, thinking it at first a Wood

Thrush and then a Thrasher, but soon

finding that it was neither of these I

opened the window softly and looked

among the near by shrubs, with my

glass. The wonderful melody ascended

gradually in the scale as it progressed,

now trilling, now legato, the most

perfect, exalted, unrestrained, yet

withal, finished bird song that I ever

heard. At the first note I caught

sight of the singer perching among

the lower sprays of a dogwood tree.

I could see him perfectly: it was the

Hermit Thrush. In a moment he

began again. I have never heard the

Nightingale, but those who have say

that it is the surroundings and its continuous

night singing that make it even

the equal of our Hermit; for, while

the Nightingales sing in numbers in

the moonlit groves, the Hermit tunes

his lute sometimes in inaccessible solitudes,

and there is something immaterial

and immortal about the song.”

The Hermit Thrush is comparatively

common in the northeast, and in

Pennsylvania it is, with the exception

of the Robin, the commonest of the

Thrushes. In the eastern, as in many

of the middle states, it is only a

migrant. It is usually regarded as a

shy bird. It is a species of more

general distribution than any of the

small Thrushes, being found entirely

across the continent and north to the

Arctic regions. It is not quite the

same bird, however, in all parts of its

range, the Rocky Mountain region

being occupied by a larger, grayer

race, while on the Pacific coast a

dwarf race takes its place. It is

known in parts of New England as

the “Ground Swamp Robin,” and in

other localities as “Swamp Angel.”

True lovers of nature find a certain

spiritual satisfaction in the song of

this bird. “In the evening twilight

of a June day,” says one of these,

“when all nature seemed resting in

quiet, the liquid, melting, lingering

notes of the solitary bird would steal

out upon the air and move us strangely.

What was the feeling it awoke in

our hearts? Was it sorrow or joy,

fear or hope, memory or expectation?

And while we listened, we thought

the meaning of it all was coming; it

was trembling on the air, and in an

instant it would reach us. Then it

faded, it was gone, and we could not

even remember what it had been.”

[Pg 88]

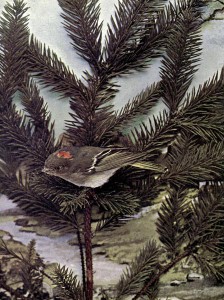

hermit thrush.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 89]

THE HERMIT THRUSH.

I am sorry, children, that I

cannot give you a specimen of

my song as an introduction to

the short story of my life. One

writer about my family says it

is like this: “O spheral, spheral!

O holy, holy! O clear away,

clear away! O clear up, clear

up!” as if I were talking to the

weather. May be my notes do

sound something like that, but

I prefer you should hear me

sing when I am alone in the

woods, and other birds are

silent. It is ever being said of

me that I am as fine a singer as

the English Nightingale. I

wish I could hear this rival of

mine, and while I have no doubt

his voice is a sweet one, and I

am not too vain of my own, I

should like to “compare notes”

with him. Why do not some of

you children ask your parents to

invite a few pairs of Nightingales

to come and settle here?

They would like our climate,

and would, I am sure, be welcomed

by all the birds with a

warmth not accorded the English

Sparrow, who has taken

possession and, in spite of my

love for secret hiding places,

will not let even me alone.

When you are older, children,

you can read all about me in

another part of Birds. I will

merely tell you here that I live

with you only from May to

October, coming and going away

in company with the other

Thrushes, though I keep pretty

well to myself while here, and

while building my nest and

bringing up my little ones I

hide myself from the face of

man, although I do not fear his

presence. That is why I am

called the Hermit.

If you wish to know in what

way I am unlike my cousin

Thrushes in appearance, turn

to pages 84

and 182, Vol. 1, of

Birds. There you will see their

pictures. I am one of the smallest

of the family, too. Some

call me “the brown bird with

the rusty tail,” and other names

have been fitted to me, as

Ground Gleaner, Tree Trapper,

and Seed Sower. But I do not

like nicknames, and am just

plain,

Hermit Thrush.

[Pg 90]

THE SONG SPARROW.

Glimmers gay the leafless thicket

Close beside my garden gate,

Where, so light, from post to wicket,

Hops the Sparrow, blithe, sedate;

Who, with meekly folded wing,

Comes to sun himself and sing.

It was there, perhaps, last year,

That his little house he built;

For he seemed to perk and peer

And to twitter, too, and tilt

The bare branches in between,

With a fond, familiar mien.

—George Parsons Lathrop.

E do not think it at all

amiss to say that this darling

among song birds

can be heard singing

nearly everywhere the whole year

round, although he is supposed to

come in March and leave us in November.

We have heard him in February,

when his little feet made tracks

in the newly fallen snow, singing as

cheerily as in April, May, and June,

when he is supposed to be in ecstacy.

Even in August, when the heat of

the dog-days and his moulting time

drive him to leafy seclusion, his liquid

notes may be listened for with certainty,

while “all through October

they sound clearly above the rustling

leaves, and some morning he comes to

the dogwood by the arbor and announces

the first frost in a song that is

more direct than that in which he

told of spring. While the chestnuts

fall from their velvet nests, he is

singing in the hedge; but when the

brush heaps burn away to fragrant

smoke in November, they veil his

song a little, but it still continues.”

While the Song Sparrow nests in

the extreme northern part of Illinois,

it is known in the more southern

portions only as a winter resident.

This is somewhat remarkable, it is

thought, since along the Atlantic

coast it is one of the most abundant

summer residents throughout Maryland

and Virginia, in the same latitudes

as southern Illinois, where it is

a winter sojourner, abundant, but

very retiring, inhabiting almost solely

the bushy swamps in the bottom

lands, and unknown as a song bird.

This is regarded as a remarkable

instance of variation in habits with

locality, since in the Atlantic states

it breeds abundantly, and is besides

one of the most familiar of the native

birds.

The location of the Song Sparrow’s

nest is variable; sometimes on the

ground, or in a low bush, but usually

in as secluded a place as its instinct of

preservation enables it to find. A

favorite spot is a deep shaded ravine

through which a rivulet ripples, where

the solitude is disturbed only by the

notes of his song, made more sweet

and clear by the prevailing silence.

[Pg 91]

song sparrow.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 93]

THE SONG SPARROW.

Dear Young Readers:

I fancy many of the little

folks who are readers of Birds

are among my acquaintances.

Though I have never spoken to

you, I have seen your eyes

brighten when my limpid little

song has been borne to you by a

passing breeze which made

known my presence. Once I

saw a pale, worn face turn to

look at me from a window, a

smile of pleasure lighting it up.

And I too was pleased to think

that I had given some one a

moment’s happiness. I have

seen bird lovers (for we have

lovers, and many of them) pause

on the highway and listen to

my pretty notes, which I know

as well as any one have a cheerful

and patient sound, and

which all the world likes, for to

be cheered and encouraged

along the pathway of life is like

a pleasant medicine to my weary

and discouraged fellow citizens.

For you must know I am a citizen,

as my friend Dr. Coues

calls me, and all my relatives.

He and Mrs. Mabel Osgood

Wright have written a book

about us called “Citizen Bird,”

and in it they have supported us

in all our rights, which even

you children are beginning to

admit we have. You are kinder

to us than you used to be. Some

of you come quickly to our

rescue from untaught and

thoughtless boys who, we think,

if they were made to know how

sensitive we are to suffering and

wrong, would turn to be our

friends and protectors instead.

One dear boy I remember well

(and he is considered a hero by

the Song Sparrows) saved a nest

of our birdies from a cruel

school boy robber. Why should

not all strong boys become our

champions? Many of them

have great, honest, sympathetic

hearts in their bosoms, and, if

we can only enlist them in our

favor, they can give us a peace

and protection which for

years we have been sighing.

Yes, sighing, because our hearts,

though little, are none the less

susceptible to all the asperities—the

terrible asperities of

human nature. Papa will tell

you what I mean: you would

not understand bird language.

Did you ever see my nest? I

build it near the ground, and

sometimes, when kind friends

prepare a little box for me, I

occupy it. My song is quite

varied, but you will always

recognize me by my call note,

Chek! Chek! Chek! Some people

say they hear me repeat “Maids,

maids, maids, hang on your

teakettle,” but I think this is

only fancy, for I can sing a real

song, admired, I am sure, by all

who love

Song Sparrow.

[Pg 94]

THE CUCKOO.

UR first introduction to the

Cuckoo was by means of

the apparition which issued

hourly from a little German

clock, such as are frequently

found in country inns. This particular

clock had but one dial hand, and

the exact time of day could not

be determined by it until the appearance

of the Cuckoo, who, in a squeaking

voice, seemed to announce that it

was just one hour later or earlier, as

the case might be, than at his last

appearance. We were puzzled, and

remember fancying that a sun dial, in

clear weather, would be far more

satisfactory as a time piece. “Coo-coo,”

the image repeated, and then retired

until the hour hand should summon

him once more.

To very few people, not students of

birds, is the Cuckoo really known.

Its evanescent voice is often recognized,

but being a solitary wanderer

even ornithologists have yet to learn

much of its life history. In their

habits the American and European

Cuckoos are so similar that whatever

of poetry and sentiment has been

written of them is applicable alike to

either. A delightful account of the

species may be found in Dixon’s Bird

Life, a book of refreshing and original

observation.

“The Cuckoo is found in the verdant

woods, in the coppice, and even on

the lonely moors. He flits from one

stunted tree to another and utters his

notes in company with the wild song

of the Ring Ousel and the harsh calls

of the Grouse and Plover. Though

his notes are monotonous, still no one

gives them this appellation. No! this

little wanderer is held too dear by us

all as the harbinger of spring for

aught but praise to be bestowed on his

mellow notes, which, though full and

soft, are powerful, and may on a calm

morning, before the everyday hum of

human toil begins, be heard a mile

away, over wood, field, and lake.

Toward the summer solstice his notes

are on the wane, and when he gives

them forth we often hear him utter

them as if laboring under great difficulty,

and resembling the syllables,

“Coo-coo-coo-coo”.”

On one occasion Dixon says he

heard a Cuckoo calling in treble

notes, Cuck oo-oo, cuck-oo-oo, inexpressibly

soft and beautiful, notably

the latter one. He at first supposed

an echo was the cause of these strange

notes, the bird being then half a mile

away, but he satisfied himself that this

was not the case, as the bird came and

alighted on a noble oak a few yards

from him and repeated the notes.

The Cuckoo utters his notes as he

flies, but only, as a rule, when a few

yards from the place on which he

intends alighting.

The opinion is held by some observers

that Nature has not intended

the Cuckoo to build a nest, but influences

it to lay its eggs in the nests of

other birds, and intrust its young to

the care of those species best adapted

to bring them to maturity. But the

American species does build a nest,

and rears its young, though Audubon

gives it a bad character, saying: “It

robs smaller birds of their eggs.” It

does not deserve the censure it has

received, however, and it is useful

in many ways. Its hatred of the

worm is intense, destroying many

more than it can eat. So thoroughly

does it do its work, that orchards,

which three years ago, were almost

leafless, the trunks even being covered

by slippery webbing, are again yielding

a good crop.

In September and October the

Cuckoo is silent and suddenly disappears.

“He seldom sees the lovely

tints of autumn, and never hears the

wintry storm-winds’ voice, for, impelled

by a resistless impulse, he

wings his way afar over mountain,

stream, and sea, to a land where

northern blasts are not felt, and where

a summer sun is shining in a cloudless

sky.”

[Pg 95]

yellow-billed cuckoo.

From col. O. E. Pagin.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 97]

THE RUBY-THROATED HUMMING BIRD.

Is it a gem, half bird,

Or is it a bird, half gem?

—Edgar Fawcett.

F all animated beings this is

the most elegant in form

and the most brilliant in

colors, says the great naturalist

Buffon. The stones

and metals polished by our arts are

not comparable to this jewel of Nature.

She has it least in size of the order of

birds, maxime miranda in minimis. Her

masterpiece is the Humming bird, and

upon it she has heaped all the gifts

which the other birds may only share.

Lightness, rapidity, nimbleness, grace,

and rich apparel all belong to this

little favorite. The emerald, the ruby,

and the topaz gleam upon its dress.

It never soils them with the dust of

earth, and its aerial life scarcely

touches the turf an instant. Always

in the air, flying from flower to flower,

it has their freshness as well as their

brightness. It lives upon their nectar,

and dwells only in the climates where

they perennially bloom.

All kinds of Humming birds are

found in the hottest countries of the

New World. They are quite numerous

and seem to be confined between

the two tropics, for those which penetrate

the temperate zones in summer

stay there only a short time. They

seem to follow the sun in its advance

and retreat; and to fly on the zephyr

wing after an eternal spring.

The smaller species of the Humming birds

are less in size than the

great fly wasp, and more slender than

the drone. Their beak is a fine needle

and their tongue a slender thread.

Their little black eyes are like two

shining points, and the feathers of

their wings so delicate that they seem

transparent. Their short feet, which

they use very little, are so tiny one

can scarcely see them. They rarely

alight during the day. They have a

swift continual humming flight. The

movement of their wings is so rapid

that when pausing in the air, the bird

seems quite motionless. One sees him

stop before a blossom, then dart like a

flash to another, visiting all, plunging

his tongue into their hearts, flattening

them with his wings, never settling

anywhere, but neglecting none. He

hastens his inconstancies only to pursue

his loves more eagerly and to

multiply his innocent joys. For this

light lover of flowers lives at their

expense without ever blighting them.

He only pumps their honey, and for

this alone his tongue seems designed.

The vivacity of these small birds is

only equaled by their courage, or

rather their audacity. Sometimes

they may be seen furiously chasing birds

twenty times their size, fastening

upon their bodies, letting themselves

be carried along in their flight, while

they peck fiercely until their tiny rage

is satisfied. Sometimes they fight

each other vigorously. Impatience

seems their very essence. If they approach

a blossom and find it faded,

they mark their spite by a hasty rending

of the petals. Their only voice is

a weak cry of Screp, screp, frequent

and repeated, which they utter in the

woods from dawn until at the first rays

of the sun they all take flight and

scatter over the country.

The Ruby-throat is the only native

Humming bird of eastern North

America, where it is a common summer

resident from May to October,

breeding from Florida to Labrador.

The nest is a circle an inch and a half

in diameter, made of fern wood, plant

down, and so forth, shingled with

lichens to match the color of the

branch on which it rests. Its only

note is a shrill, mouse-like squeak.

[Pg 99]

THE HOUSE WREN.

All the children, it seems to

me, are familiar with the habits

of Johnny and Jenny Wren;

and many of them, especially

such as have had some experience

with country life, could

themselves tell a story of these

mites of birds. Mr. F. Saunders

tells one: “Perhaps you may

think the Wren is so small a

bird he cannot sing much of a

song, but he can. The way we

first began to notice him was by

seeing our pet cat jumping about

the yard, dodging first one way

and then another, then darting

up a tree; looking surprised,

and disappointingly jumping

down again.

“Pussy had found a new play-mate,

for the little Wren evidently

thought it great fun to

fly down just in front of her and

dart away before she could

reach him, leading her from one

spot to another, hovering above

her head, chattering to her all

the time, and at last flying up

far out of her reach. This he

repeated day after day, for some

time, seeming to enjoy the fun

of disappointing her so nicely

and easily. But after a while

the little fellow thought he

would like a play-mate nearer

his own size, and went off to

find one. But he came back all

alone, and perched himself on

the very tip-top of a lightning-rod

on a high barn at the back

of the yard; and there he would

sing his sweet little trilling

song, hour after hour, hardly

stopping long enough to find

food for his meals. We wondered

that he did not grow tired

of it. For about a week we

watched him closely, and one

day I came running into the

house to tell the rest of the

family with surprise and delight

that our little Wren knew what

he was about, for with his winning

song he had called a mate

to him. He led her to the tree

where he had played with pussy,

and they began building a nest;

but pussy watched then as well

as we, and meant to have her

revenge upon him yet, so she

sprang into the tree, tore the

nest to pieces, and tried to catch

Jenny. The birds rebuilt their

nest three times, and finally we

came to their rescue and placed

a box in a safe place under the

eaves of the house, and Mr.

Wren with his keen, shrewd

eyes, soon saw and appropriated

it. There they stayed and raised

a pretty family of birdies; and

I hope he taught them, as he

did me, a lesson in perseverance

I’ll never forget.”

[Pg 100]

ruby-throated humming birds.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 101]

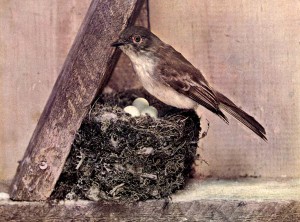

house wren.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 103]

THE RUBY-THROATED HUMMING BIRD.

Dear Young Folks:

I fancy you think I cannot

stop long enough to tell you a

story, even about myself. It is

true, I am always busy with the

flowers, drinking their honey

with my long bill, as you must

be busy with your books, if you

would learn what they teach.

I always select for my food the

sweetest flowers that grow in

the garden.

Do you think you would be

vain if you had my beautiful

colors to wear? Of course, you

would not, but so many of my

brothers and sisters have been

destroyed to adorn the bonnets

and headdresses of the thoughtless

that the children cannot be

too early taught to love us too

well to do us harm. Have you

ever seen a ruby? It is one of

the most valued of gems. It is

the color of my throat, and from

its rare and brilliant beauty I

get a part of my name. The

ruby is worn by great ladies

and, with the emerald and topaz,

whose bright colors I also wear,

is much esteemed as an ornament.

If you will come into the

garden in the late afternoon,

between six and seven o’clock,

when I am taking my supper,

and when the sun is beginning

to close his great eye, you will

see his rays shoot sidewise and

show all the splendor of my

plumage. You will see me, too,

if your eyes are sharp enough,

draw up my tiny claws, pause in

front of a rose, and remain

seemingly motionless. But

listen, and you will hear the

reason for my name—a tense

humming sound. Some call me

a Hummer indeed.

I spend only half the year in

the garden, coming in May and

saying farewell in October.

After my mate and I are gone

you may find our nest. But

your eyes will be sharp indeed

if they detect it when the leaves

are on the trees, it is so small

and blends with the branches.

We use fern-wool and soft down

to build it, and shingle it with

lichens to match the branch it

nests upon. You should see the

tiny eggs of pure white. But

we, our nest and our eggs, are

so dainty and delicate that they

should never be touched. We

are only to be looked at and

admired.

Farewell. Look for me when

you go a-Maying.

Ruby.

[Pg 104]

THE HOUSE WREN.

“It was a merry time

When Jenny Wren was young,

When prettily she looked,

And sweetly, too, she sung.”

N looking over an old memorandum

book the other day,”

says Col. S. T. Walker, of

Florida, “I came across the

following notes concerning

the nesting of the House Wren. I

was sick at the time, and watched the

whole proceeding, from the laying of

the first stick to the conclusion. The

nest was placed in one of the pigeonholes

of my desk, and the birds

effected an entrance to the room

through sundry cracks in the log

cabin.”

| Nest begun | April 15th. | |

| Nest completed and first egg laid | April 27th. | |

| Last egg laid | May 3rd. | |

| Began sitting | May 4th. | |

| Hatching completed | May 18th. | |

| Young began to fly | May 27th. | |

| Young left the nest | June 1st. | |

| Total time occupied | 47 days. |

Such is the usual time required for

bringing forth a brood of this species

of Wren, which is the best known of

the family. In the Atlantic states it

is more numerous than in the far west,

where wooded localities are its chosen

haunts, and where it is equally at

home in the cottonwoods of the river

valleys, and on the aspens just below

the timber line on lofty mountains.

Mrs. Osgood Wright says very

quaintly that the House Wren is a

bird who has allowed the word male

to be obliterated from its social constitution

at least: that we always speak

of Jenny Wren: always refer to the

Wren as she as we do of a ship. That

it is Johnny Wren who sings and disports

himself generally, but it is Jenny,

who, by dint of much scolding and

fussing, keeps herself well to the front.

She chooses the building-site and

settles all the little domestic details.

If Johnny does not like her choice, he

may go away and stay away; she will

remain where she has taken up her

abode and make a second matrimonial

venture.

The House Wren’s song is a merry

one, sudden, abruptly ended, and frequently

repeated. It is heard from the

middle of April to October, and upon

the bird’s arrival it at once sets about

preparing its nest, a loose heap of sticks

with a soft lining, in holes, boxes, and

the like. From six to ten tiny, cream-colored

eggs are laid, so thickly spotted

with brown that the whole egg is

tinged.

The House Wren is not only one

of our most interesting and familiar

neighbors, but it is useful as an

exterminator of insects, upon which it

feeds. Frequently it seizes small butterflies

when on the wing. We have

in mind a sick child whose convalescence

was hastened and cheered by

the near-by presence of the merry

House Wren, which sings its sweet

little trilling song, hour after hour,

hardly stopping long enough to find

food for its meals.

[Pg 106]

phoebe.

From col. J. G. Parker. Jr.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 107]

THE PHOEBE.

Oft the Phoebe’s cheery notes

Wake the laboring swain;

“Come, come!” say the merry throats,

“Morn is here again.”

Phoebe, Phoebe! let them sing for aye,

Calling him to labor at the break of day.

—C. C. M.

EARLY everywhere in the

United States we find this

cheerful bird, known as

Pewee, Barn Pewee,

Bridge Pewee, or Phoebe, or Pewit

Flycatcher. “It is one of that charming

coterie of the feathered tribe who

cheer the abode of man with their

presence.” There are few farmyards

without a pair of Pewees, who do the

farmer much service by lessening the

number of flies about the barn, and by

calling him to his work in the morning

by their cheery notes.

Dr. Brewer says that this species is

attracted both to the vicinity of water

and to the neighborhood of dwellings,

probably for the same reason—the

abundance of insects in either situation.

They are a familiar, confiding, and

gentle bird, attached to localities, and

returning to them year after year.

Their nests are found in sheltered

situations, as under a bridge, a projecting

rock, in the porches of houses,

etc. They have been known to build

on a small shelf in the porch of a

dwelling, against the wall of a railroad

station, within reach of the passengers,

and under a projecting window-sill, in

full view of the family, entirely

unmoved by the presence of the latter

at meal time.

Like all the flycatcher family the

Phoebe takes its food mostly flying.

Mrs. Wright says that the Pewee in

his primitive state haunts dim woods

and running water, and that when

domesticated he is a great bather, and

may be seen in the half-light dashing

in and out of the water as he makes

trips to and from the nest. After the

young are hatched both old and young

disport themselves about the water

until moulting time. She advises:

“Do not let the Phoebes build under

the hoods of your windows, for their

spongy nests harbor innumerable bird-lice,

and under such circumstances

your fly-screens will become infested

and the house invaded.”

In its native woods the nest is of

moss, mud, and grass placed on a rock,

near and over running water; but in

the vicinity of settlements and villages

it is built on a horizontal bridge beam,

or on timber supporting a porch or

shed. The eggs are pure white, somewhat

spotted. The notes, to some

ears, are Phoebe, phoebe, pewit, phoebe!

to others, of somewhat duller sense of

hearing, perhaps, Pewee, pewee, pewee!

We confess to a fancy that the latter

is the better imitation.

[Pg 108]

THE RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET.

ASKETT says that the

Kinglets come at a certain

early spring date before

the leaves are fully expanded,

and flutter upward,

while they take something from

beneath the budding leaf or twig. It

is a peculiar motion, which with their

restless ways, olive-green color, and

small size, readily distinguishes them.

It is rare that one is still. “But the

ruby-crowned sometimes favors me

with a song, and as it is a little long,

he usually is quiet till done. It is

one of the sweetest little lullaby-like

strains. One day I saw him in the

rose bush just near voluntarily expand

the plumage of his crown and show

the brilliant golden-ruby feathers

beneath. Usually they are mostly

concealed. It was a rare treat, and

visible to me only because of my

rather exalted view. He generally

reserves this display for his mate, but

he was here among some Snow-birds

and Tree Sparrows, and seemed to be

trying to make these plain folks

envious of the pretty feathers in his

hat.”

These wonderfully dainty little

birds are of great value to the farmer

and the fruit grower, doing good work

among all classes of fruit trees by

killing grubs and larvae. In spite of

their value in this respect, they have

been, in common with many other

attractive birds, recklessly killed for

millinery purposes.

It is curious to see these busy

wanderers, who are always cheery and

sociable, come prying and peering

about the fruit trees, examining every

little nook of possible concealment

with the greatest interest. They do

not stay long after November, and

return again in April.

The nest of this Kinglet is rarely

seen. It is of matted hair, feathers,

moss, etc., bulky, round, and partly

hanging. Until recently the eggs

were unknown. They are of a dirty

cream-white, deepening at larger end

to form a ring, some specimens being

spotted.

Mr. Nehrling, who has heard this

Kinglet sing in central Wisconsin and

northern Illinois, speaks of the “power,

purity, and volume of the notes, their

faultless modulation and long continuance,”

and Dr. Elliott Coues says

of it: “The Kinglet’s exquisite vocalization

defies description.” Dr. Brewer

says that its song is clear, resonant,

and high, a prolonged series, varying

from the lowest tones to the highest,

and terminating with the latter. It

may be heard at quite a distance, and

in some respects bears more resemblance

to the song of the English

Sky-lark than to that of the Canary,

to which Mr. Audubon compares it.

[Pg 110]

ruby-crowned kinglet.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 111]

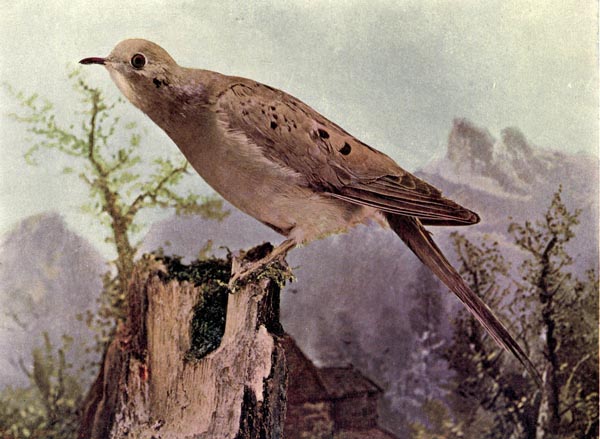

THE MOURNING DOVE.

Dear Young Bird Lovers:

Most every person thinks that,

while my actions are very pretty

and attractive, and speak much

in my favor, I can only really

say, Coo-o, Coo-o, which they also

think does not mean anything at

all. Well, I just thought I

would undeceive them by writing

you a letter. Many grown

up people fancy that we birds

cannot express ourselves because

we don’t know very much.

Of course, there is a good reason

why they have this poor opinion

of us. They are so busy with

their own private concerns that

they forget that there are little

creatures like ourselves in the

world who, if they would take a

little time to become acquainted

with them, would fill their few

hours of leisure with a sweeter

recreation than they find in

many of their chosen outings.

A great English poet, whose

writings you will read when you

get older, said you should look

through Nature up to Nature’s

God. What did he mean? I

think he had us birds in his

mind, for it is through a study

of our habits, more perhaps than

that of the voiceless trees or the

dumb four-footed creatures that

roam the fields, that your hearts

are opened to see and admire

real beauty. We birds are the

true teachers of faith, hope, and

charity,—faith, because we trust

one another; hope, because,

even when our mother Nature

seems unkind, sending the drifting

snow and the bitter blasts

of winter, we sing a song of

summer time; and charity, because

we are never fault finders.

I believe, without knowing it,

I have been telling you about

myself and my mate. We

Doves are very sincere, and

every one says we are constant.

If you live in the country,

children, you must often hear

our voices. We are so tender

and fond of each other that we

are looked upon as models for

children, and even grown-up

folks. My mate does not build

a very nice nest—only uses a

few sticks to keep the eggs from

falling out—but she is a good

mother and nurses the little

ones very tenderly. Some people

are so kind that they build

for us a dove cote, supply us

with wheat and corn, and make

our lives as free from care and

danger as they can. Come and

see us some day, and then you

can tell whether my picture is a

good one. The artist thinks it

is and he certainly took lots of

pains with it.

Now, if you will be kind to

all birds, you will find me, in

name only,

Mourning Dove.

[Pg 113]

mourning dove.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 115]

HOW THE BIRDS SECURED THEIR RIGHTS.

Deuteronomy xxxii 6-7.—“If a bird’s nest chance to be before thee

in the way, in any tree, or on the ground, young ones or eggs, and

the dam sitting upon the young, or upon the eggs, thou shalt not

take the dam with the young. But thou shalt in anywise let the dam

go, that it may be well with thee, and that thou may prolong thy

days.”

T is said that the following petition

was instrumental in securing

the adoption in Massachusetts

of a law prohibiting the

wearing of song and insectivorous

birds on women’s hats. It is

stated that the interesting document

was prepared by United States Senator

Hoar. The foregoing verse of Scripture

might have been quoted by the

petitioning birds to strengthen their

position before the lawmakers:

“To the Great and General

Court of the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts: We, the song birds

of Massachusetts and their playfellows,

make this our humble petition. We

know more about you than you think

we do. We know how good you are.

We have hopped about the roofs and

looked in at the windows of the houses

you have built for poor and sick and

hungry people, and little lame and

deaf and blind children. We have

built our nests in the trees and sung

many a song as we flew about the

gardens and parks you have made so

beautiful for your children, especially

your poor children, to play in. Every

year we fly a great way over the

country, keeping all the time where

the sun is bright and warm. And we

know that whenever you do anything

the other people all over this great

land between the seas and the great

lakes find it out, and pretty soon will

try to do the same. We know. We

know.

“We are Americans just the same as

you are. Some of us, like some of

you, came across the great sea. But

most of the birds like us have lived

here a long while; and the birds like

us welcomed your fathers when they

came here many, many years ago. Our

fathers and mothers have always done

their best to please your fathers and

mothers.

“Now we have a sad story to tell

you. Thoughtless or bad people are

trying to destroy us. They kill us

because our feathers are beautiful.

Even pretty and sweet girls, who we

should think would be our best friends,

kill our brothers and children so that

they may wear our plumage on their

hats. Sometimes people kill us for

mere wantonness. Cruel boys destroy

our nests and steal our eggs and our

young ones. People with guns and

snares lie in wait to kill us; as if the

place for a bird were not in the sky,

alive, but in a shop window or in a

glass case. If this goes on much

longer all our song birds will be gone.

Already we are told in some other

countries that used to be full of birds

they are now almost gone. Even the

Nightingales are being killed in Italy.

“Now we humbly pray that you

will stop all this and will save us from

this sad fate. You have already made

a law that no one shall kill a harmless

song bird or destroy our nests or

our eggs. Will you please make another

one that no one shall wear our

feathers, so that no one shall kill us to

get them? We want them all ourselves.

Your pretty girls are pretty

enough without them. We are told

that it is as easy for you to do it as for

a blackbird to whistle.

“If you will, we know how to pay

you a hundred times over. We will

teach your children to keep themselves

clean and neat. We will show

them how to live together in peace

and love and to agree as we do in our

nests. We will build pretty houses

which you will like to see. We will

[Pg 116]

play about your garden and flowerbeds—ourselves

like flowers on wings—without

any cost to you. We will

destroy the wicked insects and worms

that spoil your cherries and currants

and plums and apples and roses. We

will give you our best songs, and make

the spring more beautiful and the

summer sweeter to you. Every June

morning when you go out into the

field, Oriole and Bluebird and Blackbird

and Bobolink will fly after you,

and make the day more delightful to

you. And when you go home tired after

sundown Vesper Sparrow will tell you

how grateful we are. When you sit

down on your porch after dark, Fifebird

and Hermit Thrush and Wood Thrush

will sing to you; and even Whip-poor-will

will cheer you up a little. We

know where we are safe. In a little

while all the birds will come to live

in Massachusetts again, and everybody

who loves music will like to make a

summer home with you.”

The singers are:

| Brown Thrasher, | King Bird, | |

| Robert o’Lincoln, | Swallow, | |

| Vesper Sparrow, | Cedar Bird, | |

| Hermit Thrush, | Cow-bird, | |

| Robin Redbreast, | Martin, | |

| Song Sparrow, | Veery, | |

| Scarlet Tanager, | Vireo, | |

| Summer Redbird, | Oriole, | |

| Blue Heron, | Blackbird, | |

| Humming Bird, | Fifebird, | |

| Yellow-bird, | Wren, | |

| Whip-poor-will, | Linnet, | |

| Water Wagtail, | Pewee, | |

| Woodpecker, | Phoebe, | |

| Pigeon Woodpecker, | Yoke Bird, | |

| Indigo Bird, | Lark, | |

| Yellow Throat, | Sandpiper, | |

| Wilson’s Thrush, | Chewink. | |

| Chickadee, |

THE CAPTIVE’S ESCAPE.

I saw such a sorrowful sight, my dears,

Such a sad and sorrowful sight,

As I lingered under the swaying vines,

In the silvery morning light.

The skies were so blue and the day was so fair

With beautiful things untold,

You would think no sad and sorrowful thing

Could enter its heart of gold.

A fairy-like cage was hanging there,

So gay with turret and dome.

You’d be sure a birdie would gladly make

Such a beautiful place its home.

But a wee little yellow-bird sadly chirped

As it fluttered to and fro;

I know it was longing with all its heart

To its wild-wood home to go.

I heard a whir of swift-rushing wings,

And an answering gladsome note;

As close to its nestlings’ prison bars,

I saw the poor mother bird float.

I saw her flutter and strive in vain

To open the prison door.

Then sadly cling with drooping wing

As if all her hopes were o’er.

But ere I could reach the prison house

And let its sweet captive free,

She was gone like a yellow flash of light,

To her home in a distant tree.

“Poor birdie,” I thought, “you shall surely go,

When mamma comes back again;”

For it hurt me so that so small a thing

Should suffer so much of pain.

And back in a moment she came again

And close to her darling’s side

With a bitter-sweet drop of honey dew,

Which she dropped in its mouth so wide.

Then away, with a strange wild mournful note

Of sorrow, which seemed to say

“Goodbye, my darling, my birdie dear,

Goodbye for many a day.”

A quick wild flutter of tiny wings,

A faint low chirp of pain,

A throb of the little aching heart

And birdie was free again.

Oh sorrowful anguished mother-heart,

’Twas all that she could do,

She had set it free from a captive’s life

In the only way she knew.

Poor little birdie! it never will fly

On tiny and tireless wing.

Through the pearly blue of the summer sky,

Or sing the sweet songs of spring.

And I think, little dears, if you had seen

The same sad sorrowful sight,

You never would cage a free wild bird

To suffer a captive’s plight.

—Mary Morrison.

[Pg 118]

white-breasted nuthatch.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

Copyrighted by

Nature Study Pub. Co., 1897, Chicago.

[Pg 119]

THE WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH.

EARLY every one readily

recognizes this species as it

runs up and down and

around the branches

and trunks of trees in

search of insect food, now and then

uttering its curious Quauk, quauk, quauk.

The White-breasted Nuthatch is often

improperly called “Sapsucker,” a

name commonly applied to the Downy

Woodpecker and others. It is a common

breeding bird and usually begins

nesting early in April, and two broods

are frequently reared in a season. For

its nesting place it usually selects the

decayed trunk of a tree or stub, ranging

all the way from two to sixty feet

above the ground. The entrance may

be a knot hole, a small opening, or a

small round hole with a larger cavity

at the end of it. Often the old excavation

of the Downy Woodpecker is

made use of. Chicken feathers, hair,

and a few dry leaves loosely thrown

together compose the nest.

This Nuthatch is abundant throughout

the State of Illinois, and is a

permanent resident everywhere except

perhaps of the extreme northern

counties. It seems to migrate in

spring and return in autumn, but, in

reality, as is well known, only retreats

to the woodlands to breed, emerging

again when the food supply grows

scant in the autumn.

The Nuthatches associate familiarly

with the Kinglets and Titmice, and

often travel with them. Though

regarded as shy birds they are not

really so. Their habits of restlessness

render them difficult of examination.

“Tree-mice” is the local name given

them by the farmers, and would be

very appropriate could they sometimes

remain as motionless as that diminutive

animal.

Careful observation has disclosed

that the Nuthatches do not suck the

sap from trees, but that they knock

off bits of decayed or loose bark with

the beak to obtain the grubs or larvae

beneath. They are beneficial to vegetation.

Ignorance is responsible for

the misapplied names given to many

of our well disposed and useful birds,

and it would be well if teachers were

to discourage the use of inappropriate

names and familiarize the children

with those recognized by the best

authorities.

Referring to the Nuthatches Mr.

Baskett says: “They are little bluish

gray birds, with white undervests—sometimes

a little soiled. Their tails

are ridiculously short, and never touch

the tree; neither does the body, unless

they are suddenly affrighted, when

they crouch and look, with their beaks

extended, much like a knot with a

broken twig on it. I have sometimes

put the bird into this attitude by

clapping my hands loudly near the

window. It is an impulse that seems

to come to the bird before flight,

especially if the head should be downward.

His arrival is sudden, and

seems often to be distinguished by

turning a somersault before alighting,

head downward, on the tree trunk, as

if he had changed his mind so suddenly

about alighting that it unbalanced

him.

“I once saw two Nuthatches at what

I then supposed was a new habit. One

spring day some gnats were engaged

in their little crazy love waltzes in the

air, forming small whirling clouds,

and the birds left off bark-probing and

began capturing insects on the wing.

They were awkward about it with

their short wings, and had to alight

frequently to rest. I went out to

them, and so absorbed were they that

they allowed me to approach within

a yard of a limb that they came to rest

upon, where they would sit and

pant till they caught their breath,

when they went at it again. They

seemed fairly to revel in a new diet

and a new exercise.”

[Pg 120]

SUMMARY

Page 83.

YELLOW WARBLER.—Dendroica æstiva.

Other names: “Summer Yellow-bird,” “Wild Canary,”

“Yellow-poll Warbler.”

Range—The whole of North America; breeding

throughout its range. In winter, the whole

of middle America and northern South America.

Nest—Built in an apple tree, cup-shaped,

neat and compact, composed of plant fibres,

bark, etc.

Eggs—Four or five; greenish-white, spotted.

Page 88.

HERMIT THRUSH.—Turdus aonalaschkæ

pallasii. Other names: “Swamp Angel,”

“Ground Swamp Robin.”

Range—Eastern North America, breeding

from northern United States northward; wintering

from about latitude 40° to the Gulf coast.

Nest—On the ground, in some low, secluded

spot, beneath shelter of deep shrubbery. Bulky

and loosely made of leaves, bark, grasses,

mosses, lined with similar finer material.

Eggs—Three or four; of greenish blue,

unspotted.

Page 91.

SONG SPARROW.—Melospiza fasciata.

Range—Eastern United States and British

Provinces, west to the Plains, breeding chiefly

north of 40°, except east of the Alleghenies.

Nest—On the ground, or in low bushes, of

grasses, weeds, and leaves, lined with fine grass

stems, roots, and, in some cases, hair.

Eggs—Four to seven; varying in color from

greenish or pinkish white to light bluish green,

spotted with dark reddish brown.

Page 95.

YELLOW-BILLED CUCKOO.—Coccyzus

americanus. Other names: “Rain Crow,”

“Rain Dove,” and “Chow-Chow.”

Range—Eastern North America to British

Provinces, west to Great Plains, south in winter,

West Indies and Costa Rica.

Nest—In low tree or bush, of dried sticks,

bark strips and catkins.

Eggs—Two to four; of glaucous green which

fades on exposure to the light.

Page 100.

RUBY-THROATED HUMMING BIRD.—Trochilus

colubris.

Range—Eastern North America to the Plains

north to the fur countries, and south in winter

to Cuba and Veragua.

Nest—A circle an inch and a half in diameter,

made of fern wool, etc., shingled with

lichens to match the color of the branch on

which it is saddled.

Eggs—Two; pure white, the size of soup beans.

Page 101.

HOUSE WREN.—Troglodytes aedon.

Range—Eastern United States and southern

Canada, west to the Mississippi Valley; winters

in southern portions.

Nest—Miscellaneous rubbish, sticks, grasses,

hay, and the like.

Eggs—Usually seven; white, dotted with

reddish brown.

Page 106.

PHOEBE.—Sayornis phœbe. Other names:

“Pewit,” “Pewee.”

Range—Eastern North America; in winter

south to Mexico and Cuba.

Nest—Compactly and neatly made of mud

and vegetable substances, with lining of grass

and feathers.

Eggs—Four or five; pure white, sometimes

sparsely spotted with reddish brown dots at

larger end.

Page 110.

RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET.—Regulus calendula.

Range—Entire North America, wintering in

the South and in northern Central America.

Nest—Very rare, only six known; of hair,

feathers, moss, etc., bulky, globular, and

partly pensile.

Eggs—Five to nine; dull whitish or pale

puffy, speckled.

Page 113.

MOURNING DOVE.—Zenaidura macrura.

Other names: “Carolina Dove,” “Turtle Dove.”

Range—Whole of temperate North America,

south to Panama and the West Indies.

Nest—Rim of twigs sufficient to retain the

eggs.

Eggs—Usually two; white.

Page 118.

WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH.—Sitta

carolinensis. Other name: “Sapsucker,”

improperly called.

Range—Eastern United States and British

Provinces.

Nest—Decayed trunk of tree or stub, from

two to six feet from ground, composed of chicken

feathers, hair, and dry leaves.

Eggs—Five to eight; white with a roseate

tinge, speckled with reddish brown and a slight

tinge of purple.

Featured Books

The Patchwork Girl of Oz

L. Frank Baum

s Dorothy by wireless telegraph, whichwould enable her to communicate to the Historian whatever happ...

Two New Pocket Gophers from Wyoming and Colorado

E. Raymond Hall and H. Gordon Montague

ng accumulated in thepast two seasons of field work in Wyoming were examined byHall. A result of the...

Ecological Observations on the Woodrat, Neotoma floridana

Dennis G. Rainey and Henry S. Fitch

r period, from February, 1948, to February, 1956, theseeffects have changed greatly as the populatio...

A Synopsis of the North American Lagomorpha

E. Raymond Hall

ge for the publications of learned societiesand institutions, universities and libraries. For exchan...

Wild Animals at Home

Ernest Thompson Seton

ntain haven of wild life.Whenever travellers penetrate into remote regionswhere human hunters are un...

Sue, A Little Heroine

L. T. Meade

written, dealing largely withquestions of home life, are: David's Little Lad; Great St.Benedict's; A...

The Brass Bottle

F. Anstey

er, he made his thoughts travel back to a certain gloriousmorning in August which now seemed so remo...

Stories by Foreign Authors: Scandinavian

lid black; /* a thin black line border.. */ padding: 6px; /* ..spaced a bit out from the gr...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 2, No. 3" :