The Project Gutenberg eBook of Mammals of the San Gabriel Mountains of California

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Mammals of the San Gabriel Mountains of California

Author: Terry A. Vaughan

Release date: January 5, 2011 [eBook #34848]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Erica Pfister-Altschul, Joseph

Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAMMALS OF THE SAN GABRIEL MOUNTAINS OF CALIFORNIA ***

Transcriber's Note

The following changes have been made to the original text:

page 531: "Virginia Opossom" changed to "Virginia Opossum"

page 551: "4600 ft. 3" changed to "4600 ft., 3"

page 555: "laural sumac" changed to "laurel sumac"

page 566: "concealed itelf" changed to "concealed itself"

page 582: "Oakshott, G. B." changed to "Oakeshott, G. B."

Instances of inconsistent hyphenation have been preserved.

In cases where tables were located in the middle of a paragraph, they have been moved to the next paragraph break. This may affect at what page number a table was originally located.

The list of University of Kansas publications was originally printed on the front and back covers. For this version of the text, the list has been combined and placed at the end of the text.

University of Kansas Publications

Museum of Natural History

Volume 7, No. 9, pp. 513-582, 4 pls., 1 fig. in text, 12 tables

November 15, 1954

Mammals of the San Gabriel Mountains

of California

BY

TERRY A. VAUGHAN

University of Kansas

Lawrence

1954

University of Kansas Publications,

Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, A. Byron Leonard,

Robert W. Wilson

Volume 7, No. 9, pp. 513-582, 4 pls., 1 fig. in text, 12 tables

Published November 15, 1954

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

PRINTED BY

FERD VOILAND, JR., STATE PRINTER

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1954

25-5184

MAMMALS OF THE SAN GABRIEL MOUNTAINS

OF CALIFORNIA

by

Terry A. Vaughan

CONTENTS

- PAGE

- Introduction

515 - Description of the Area

516 - Biotic Provinces and Ecologic Associations

518 - Coastal Sage Scrub Association

521 - Southern Oak Woodland Association

523 - Chaparral Association

524 - Yellow Pine Forest Association

526 - Pinyon-juniper Woodland Association

527 - Sagebrush Scrub Association

530 - Joshua Tree Woodland Association

530

- Coastal Sage Scrub Association

- Accounts of Species

531 - Literature Cited

581

Introduction

This paper presents the results of a study of the mammals of

the San Gabriel Mountains of southern California, and supplements

the more extensive reports on the biota of the San Bernardino Mountains

by Grinnell (1908), on the fauna of the San Jacinto Range by

Grinnell and Swarth (1913), and on the biota of the Santa Ana

Mountains by Pequegnat (1951).

The primary objectives of my study were to determine the present

mammalian fauna of the San Gabriel Mountains, to ascertain the

geographic and ecologic range of each species, and to determine

the systematic status of the mammals. In addition, certain life

history observations have been recorded.

Field work was done in the north-south cross section of the

mountains from San Gabriel Canyon on the west, to Cajon Wash

on the east; and from the gently sloping alluvium at the Pacific base

of the mountains at roughly 1000 feet elevation on the south, over

the crest of the range to the border of the Mojave Desert at an elevation

of 3500 feet on the north. Camps were established at many

points in the area with the object of collecting the mammals of each

association and each habitat. Field work was begun in the San[Pg 516]

Gabriels in November 1948, and was carried on intermittently

until March 1952. I was unable to carry on field work in any

summer.

For advice and assistance in various ways I am grateful to Drs. Willis E.

Pequegnat, Walter P. Taylor, Henry S. Fitch, E. Raymond Hall, Mr. Steven M.

Jacobs and my wife, Hazel A. Vaughan.

More than 350 mammals were prepared as study specimens; most of these are

in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. Approximately a fifth

of them are in the collection of the Department of Zoology at Pomona College,

and a few are in the University of Illinois Museum of Natural History. No

symbol is used to designate specimens in the University of Kansas Museum of

Natural History. Specimens from the Department of Zoology of Pomona College

and the University of Illinois Museum of Natural History are designated

by PC and IM, respectively.

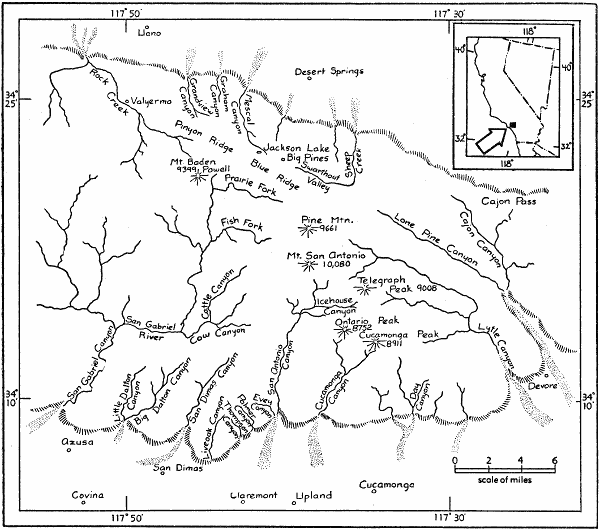

Map of the San Gabriel Mountain area showing the positions of places

mentioned in the text.

Description of the Area

The San Gabriel Mountains are approximately sixty-six miles

long, and average twenty miles wide. The main axis of the range

trends nearly east and west, and extends from longitude 117°25'[Pg 517]

to longitude 118°30'. The widest part of the range is bounded by

latitude 34°7' and latitude 34°30'.

The San Gabriel Mountains connect the Sierra Nevada with the

Peninsular Ranges of southern California and Baja California. On

the west the San Gabriels are bordered by the Tehachapi Mountains,

which stretch northeastward to meet the southern Sierra

Nevada; to the east, beyond Cajon Pass, the San Bernardino Mountains

extend eastward and then curve southward to the broad

San Gorgonio Pass, from which the San Jacinto Range stretches

southeastward to merge with the Peninsular Ranges.

The rocks comprising the major part of the San Gabriel Mountains

probably were intruded in Late Jurassic times, with severe metamorphic

activity taking place concurrently. A long period of erosion

followed after which deposition took place during much of the

Tertiary. Deformation and uplift beginning in Middle Miocene

times resulted in the formation of east-west-trending faults along

both sides of the range. By repeated movements along these faults

the Late Jurassic crystalline rocks were lifted above late Tertiary

and Quaternary sediments and elevated above the surrounding

terrain. Continued uplifts in post-Pleistocene time together with

erosion in Recent times have shaped the San Gabriel Mountains

(Oakeshott, 1937).

The alluvial slopes at the coastal base of the range give way to

the foothills at roughly 1800 feet elevation; whereas the Mojave

Desert merges with the interior foothills at elevations near 4000

feet. The crest or drainage-divide of the range varies from 6000

to 8000 feet in elevation, and many peaks are more than 8000 feet

high. San Antonio Peak, the highest peak of the range, rises to an

altitude of 10,080 feet. The mountains are characteristically steep

and the slopes are deeply carved by canyons, the larger of which

have permanent streams. The abruptness of the Pacific slope is

in many places impressive. The horizontal distance from the top

of Cucamonga Peak, at an elevation of 8911 feet, to the base of the

coastal foothills directly to the south, at 2250 feet, an elevational

difference of 6661 feet, is only 3.8 miles. From the base of Evey

Canyon, at 2250 feet, to an unnamed peak to the northwest with

an elevation of 5420 feet, the horizontal distance is 2.1 miles. Because

of the steep, rocky nature of many of the slopes and the

lack of soil on them, vegetation may be sparse even at high elevations.

There are few meadows in the mountains.

Because the San Gabriels stand approximately thirty miles from

the Pacific Ocean and are a partial barrier to Pacific air masses[Pg 518]

sweeping inland, the desert side and the coastal side of the range

differ climatically. The coastal slope receives much heavier precipitation

than the desert slope. The precipitation, for 1951, of 25.36

inches recorded at the mouth of San Antonio Canyon on the Pacific

slope contrasts with 7.17 inches recorded at Valyermo at the desert

base. Nearly all of the precipitation comes in winter. The higher

parts of the range, above approximately 5000 feet, receive much of

their mid-winter precipitation in the form of snow. Snow often

extends down the desert slope well into the Joshua Tree belt. When

there are heavy winter rains the channels of the usually dry washes

are filled with rushing, turbid water. There are striking differences

in temperature between the two sides of the range and between the

lower elevations of the mountains and the higher parts. For

example, in December 1951, the mean temperature at the base of

San Antonio Canyon (2225 feet) at the coastal foot of the range

was 55.4°F, while at Llano (3764 feet) at the desert base it was

43.7°F. In this same year the December mean for Table Mountain

(7500 feet), on the desert slope, was 33.4°F. The temperature

means for July, 1951, at San Antonio Canyon, Llano, and Table

Mountain, were 77.3°F, 82.1°F, and 69.2°F respectively. The

weather records for 1951 were used for illustration because average

temperature and average precipitation for many other years are

lacking for most of the weather stations in the area. There is an

important difference in the humidity on the two sides of the range,

but actual data are not available. At certain times, especially in

spring, fog banks moving in from the Pacific Ocean frequently

blanket the coastal base of the mountains and the foothills. On

such days the fog generally "burns off" in the morning, but may

persist into the afternoon or throughout the day. Never in my

experience has fog spilled over the main part of the range far onto

the desert slope, although the fog may push through the lower

passes to be dissipated quickly in the dry desert atmosphere. The

obvious differences in the biota on the two sides of the range are

probably due to the contrasting climates.

Biotic Provinces and Ecologic Associations

Because of the elevational extremes and attendant climatic contrasts

in the San Gabriel Mountains, there is a rather wide range of

environmental conditions. Four life-zones are represented: Lower

Sonoran, Upper Sonoran, Transition, and Canadian. Within these

zones certain ecologic communities can be recognized; these rep[Pg 519]resent

several biotic provinces. Table 1 shows the relationships

between the environmental categories recognized by the writer in

the San Gabriel Mountains. The biotic province and ecologic

community system is that developed by Munz and Keck (1949),

and the life-zone system is that of Merriam (1898).

Table 1.—Relations of the Major Environmental Categories of the

San Gabriel Mountains.

| Biotic province | Plant community | Life-zone | Slope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Californian | 1. Coastal sage scrub 2. Southern oak woodland 3. Chaparral | Lower Sonoran Upper Sonoran Upper Sonoran | Pacific Pacific Pacific |

| Sierran | 4. Yellow pine forest and limited areas of boreal flora | Transition Canadian | Pacific and Desert |

| Nevadan | 5. Sagebrush scrub | Transition Upper Sonoran | Desert |

| Southern Desert | 6. Pinyon-juniper woodland 7. Joshua tree woodland | Upper Sonoran Lower Sonoran | Desert Desert |

The Californian Biotic Province dominates the biotic aspect of

the coastal slope of the range. Thirty-nine out of the seventy-two

mammals recorded from the San Gabriels are typical of this Province.

The coastal sage-flats at the Pacific base of the mountains and

the vast tracts of chaparral of the coastal slope are included in this

Province.

Forming a hiatus between the Pacific and the desert slope is the

Sierran Biotic Province consisting of coniferous forests on the crest

of the range. The chipmunk (Eutamias speciosus speciosus) and

the introduced black bear (Ursus americanus californiensis) are

the only two mammals which can be considered typical of this

area. On the higher peaks of the range, such as Mount San Antonio

and Mount Baden Powell, the Canadian Life-zone is represented

by certain boreal plants.

At scattered points along the crest of the range and on the desert

slope, the Nevadan Biotic Province is represented by the sagebrush

scrub association. No mammals can be considered typical of this

region.

The Southern Desert Biotic Province occurs below 6000 feet elevation

on the interior slope of the range, and markedly influences[Pg 520]

the mammal fauna of this slope. Twenty-one species of mammals are

typical of this Province.

| Pinus lambertiana | Sugar Pine |

| P. monophylla | One-leaf Pinyon |

| P. ponderosa | Yellow Pine |

| P. contorta | Lodge-pole Pine |

| Pseudotsuga macrocarpa | Big-cone Spruce |

| Abies concolor | White Fir |

| Libocedrus decurrens | Incense-Cedar |

| Juniperus californica | Juniper |

| Ephedra sp. | Desert-Tea |

| Bromus sp. | Brome Grass |

| Yucca Whipplei | Spanish Bayonet |

| Y. brevifolia | Joshua Tree |

| Salix sp. | Willow |

| Alnus rhombifolia | Alder |

| Castanopsis sempervirens | Chinquapin |

| Quercus Kelloggii | California Black Oak |

| Q. agrifolia | California Live Oak |

| Q. dumosa | Scrub Oak |

| Eriogonum fasciculatum | California Buckwheat |

| Umbellularia californica | Bay, California-laurel |

| Ribes nevadense | Gooseberry |

| R. indecorum | Currant |

| R. Roezlii | Currant |

| Plantanus racemosa | Sycamore |

| Rubus vitifolius | Western Blackberry |

| Cercocarpus ledifolius | Mountain Mahogany |

| C. betuloides | Mountain Mahogany |

| Adenostoma fasciculatum | Greasewood |

| Purshia glandulosa | Antelope-brush |

| Prunus virginiana | Choke Cherry |

| P. ilicifolia | Holly-leaved Cherry |

| Larrea divaricata | Creosote Bush |

| Rhus diversiloba | Poisonoak |

| R. trilobata | Squaw Bush |

| R. laurina | Laurel Sumac |

| R. integrifolia | Lemonadeberry |

| R. ovata | Sugarbush |

| Rhamnus crocea | Buckthorn |

| Ceanothus sp. | Lilac |

| C. cordulatus | Snow-brush |

| Fremontia californica | California Slippery-elm |

| Opuntia occidentalis | Prickly-pear |

| Arctostaphylos sp. | Manzanita |

| Salvia mellifera | Black Sage |

| S. apiana | White Sage |

| Lycium Andersonii | Box-thorn |

| Haplopappus squarosus | |

| Chrysothamnus nauseosus | Rabbitbrush |

| Baccharis sp. | Mule Fat |

| Franseria dumosa | Burroweed |

| Artemisia tridentata | Basin Sagebrush |

| A. californica | Coastal Sagebrush |

| Lepidospartum squamatum | Scale-broom |

| L. latisquamatum | Scale-broom |

| Tetradymia spinosa | Cotton-thorn |

Coastal Sage Scrub Association

Artemisia californica

Salvia apiana

Salvia mellifera

Eriogonum fasciculatum

Rhus integrifolia

Opuntia occidentalis

Haploppapus squarrosus

This association is restricted to the Pacific base of the range, is

typical on the alluvium at the bases of the coastal foothills, and

usually grades into the chaparral at about 1800 feet elevation.

When seen from above, the rather level terrain of the association

is broken sharply at the mouths of canyons by dry washes, and is

limited below, to the south, by cultivated land. The coastal sagebrush

is the most characteristic plant of this association, occurring

in all undisturbed parts of the area.

There are several habitats within the coastal sage scrub association.

These differ from one another chiefly on the basis of soil

type. The soil of the rather level sageland in most places is rocky

or gravelly, or, as adjacent to washes, it is finely sandy in texture, and

supports the major plants of the association. Most of the eroded

adobe banks at the bases of the foothills support these same plants,

with white sage being the dominant species. Locally, as in damp

hollows or cleared areas, there is grassland. Jumbles of boulders,

sand, gravel, and steep cutbanks, are characteristic of the channels

of dry washes, these areas supporting sparse vegetation. The fauna

and flora of the washes are distinct from those of surrounding sage

flats. Because they are included within the geographic limits of the

coastal sage belt, however, the washes are discussed along with

this association.

The abruptness with which one habitat gives way to another in

this association causes sharp dividing lines between the local ranges

of certain mammals. For example, in trap lines transecting dry

washes and level sageland two assemblages of rodents were found.

That part of the line amid the boulders and cutbanks of the wash[Pg 522]

took mostly Peromyscus eremicus fraterculus and Neotoma lepida

intermedia, while Perognathus fallax fallax, Dipodomys agilis agilis,

and Peromyscus maniculatus gambeli were taken in the adjacent

sage flats. The steep adobe slopes of the foothills, which constitute

the upper part of the coastal sage scrub association, are commonly

inhabited by Peromyscus californicus insignis, which rarely occurs

in the level tracts of sage a few yards away. Thus, this association

is not homogeneous with regard to its rodent population; many of

these species have local and discontinuous distributions.

The following list gives the results of about 500 trap nights (a

trap night equals one trap set out for one night) in typical coastal

sage-scrub association one-half mile southwest of the mouth of San

Antonio Canyon, at 1700 feet elevation.

Table 2.—Yield of 500 Trap-nights in the Coastal Sage Scrub

Association.

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Perognathus fallax fallax | 31 | 30.7 |

| Dipodomys agilis agilis | 20 | 19.8 |

| Reithrodontomys megalotis longicaudus | 4 | 4.0 |

| Peromyscus californicus insignis | 4 | 4.0 |

| P. eremicus fraterculus | 7 | 6.9 |

| P. maniculatus gambeli | 20 | 19.8 |

| Neotoma lepida intermedia | 9 | 8.8 |

| N. fuscipes macrotis | 2 | 2.0 |

| Microtus californicus sanctidiegi | 4 | 4.0 |

The list below indicates the catch in 200 trap nights in San Antonio

Wash, at 1700 feet elevation and within the realm of the coastal

sage; all of the traps were set in rocky and sandy main channels of

the wash.

Table 3.—Yield of 200 Trap-nights in San Antonio Wash.

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Perognathus fallax fallax | 2 | 5.1 |

| Peromyscus californicus insignis | 2 | 5.1 |

| P. eremicus fraterculus | 26 | 66.7 |

| Neotoma lepida intermedia | 9 | 23.1 |

[Pg 523]

The prickly-pear cactus is of obvious importance to certain mammals

of the coastal sage belt. This cactus is most common in disturbed

areas such as sandy flats bordering washes, eroded adobe

banks, and land once cleared by man. In these areas it is often the

dominant plant with respect to area covered, usually growing in

dense patches each covering approximately 150 square feet. It

provides substitute nesting sites for Neotoma lepida in areas devoid

of rock piles, and is probably the major factor governing the distribution

of this wood rat in the sageland. Cottontails and brush

rabbits use prickly-pear cactus extensively as refuge. Their forms

and short burrows can be seen beneath many of the clumps of cactus.

This cactus serves as food for many mammals at least in the fruiting

period in the fall. Usually only the fruit is eaten, but some pads are

chewed by rabbits. The fruit or seeds of this plant are eaten by

striped skunks, gray foxes, coyotes, pocket mice, kangaroo rats,

wood rats, and probably white-footed mice.

The coyote is the dominant carnivore of the coastal sage flats.

Many individuals spend the day in the adjacent chaparral-covered

foothills and travel down into the flats at night to forage.

Alnus rhombifolia

Quercus agrifolia

Ribes indecorum

Rhus integrifolia

Rhus ovata

Rhus trilobata

This association is limited to the Pacific slope of the mountain

range, occurs in the mouths of canyons and on the floors of canyons,

and extends up the larger canyons to 4000 feet elevation or higher.

In a few areas on the flats at the coastal base of the range the oaks

replace the coastal sage.

The large oaks forming an overhead canopy and the lack of much

undergrowth give the oak woodland a shaded parklike appearance.

Few brushy or herbaceous plants grow in the mull-laden soil beneath

the oaks. Some grasses, however, are present locally.

Two habitats are found in the oak woodland: the pure oak

woodland and the riparian. Much of the oak woodland is in canyons

and therefore near streams or seepages. The larger streams

have bordering growths of alders, willows, and blackberries, inhabited

by meadow mice and shrews that are normally absent from

the adjacent oak woodland. Neotoma fuscipes macrotis and Peromyscus

californicus insignis are commonly found in the riparian

[Pg 524]

habitat, and Peromyscus boylii probably reaches peak abundance

in the stream-side thickets and tangles of plant debris.

The rather open floor of the oak woodland is relatively devoid

of mammal life. Peromyscus californicus and Peromyscus boylii,

the only ground-dwelling rodents commonly found here, usually

are taken near the limited areas of brushy growth, or the shelter

afforded by logs and fallen branches. The paucity of shelter for

small mammals seems to be an important factor limiting rodent

populations in the oak woodland.

In the foothills of the San Gabriels the gray squirrel is restricted

to the oak woodland, even though this association may be represented

by only a narrow strip of canyon bottom oak trees. The

presence or absence of "bridges" of oak woodland between mountains

which are centers of gray squirrel populations and nearby

ranges has probably been a major factor influencing the present

geographic distribution of this animal.

The raccoon is the most abundant carnivore of the oak woodland,

being especially common in the riparian habitat.

Adenostoma fasciculatum

Rhamnus crocea

Quercus dumosa

Cercocarpus betuloides

Yucca Whipplei

Prunus ilicifolia

Ceanothus sp.

Arctostaphylos sp.

Umbellularia californica

This association is characteristic of the Pacific slope of the San

Gabriels and extends from roughly 2000 feet elevation to 5000 or

6000 feet elevation. The ecotone between the chaparral and yellow

pine forest associations covers a broad elevational belt, with chaparral

following dry slopes up into coniferous forests, and conifers extending

down north slopes surrounded by chaparral.

The chaparral association is characterized by tracts of dense

brushy plants. These plants are from three to ten feet tall, their

interlacing branches often forming nearly impenetrable thickets.

Typically little herbaceous growth is present beneath the chaparral,

the ground being covered with varying amounts of mull.

The effects of fire, slope, exposure, and elevation, make the

chaparral association extremely varied with regard to habitats or

plant formations. There are nearly pure stands of greasewood on

the lower arid slopes; scrub oak, sumac, and lilac clothe less dry

[Pg 525]

exposures; scrub oak and bay trees occur commonly amid granite

talus; and locally groves of bigcone-spruce are found. Because

of the many habitats present, and the difficulty of collecting in the

chaparral, less was learned of the ecology of the mammals in this

association than of those occurring elsewhere. The distribution of

several chaparral-inhabiting mammals seems to be influenced by

the distribution of locally characteristic plants, for example oak and

bay woodland, or greasewood chaparral.

Several habitats within the chaparral community support few

species of mammals and few individuals. Possibly the compact,

rocky nature of the soil limits burrowing rodents, and the lack of

herbaceous growth limits the food supply. Steep rocky slopes in

San Antonio Canyon grown to mountain-mahogany and scrub oak

were sparsely populated by Peromyscus boylii rowleyi, Peromyscus

californicus insignis, and Neotoma fuscipes macrotis. Fifty traps

set on such a slope for one night caught only three Peromyscus.

Traps set in tracts of greasewood brush on dry south slopes at the

head of Cow Canyon produced only California mice, Peromyscus

californicus insignis Rhoads.

Following is a list of the mammals taken in the course of approximately

600 trap nights in the lower parts of the chaparral belt.

All of the traps were set on slopes in San Antonio Canyon below

4000 feet elevation. The list gives a general indication of the relative

numbers of rodents inhabiting one chaparral habitat: the arid

greasewood-covered south slopes of the lower chaparral belt.

Table 4.—Yield of 600 Trap-nights in Greasewood Chaparral.

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Perognathus californicus dispar | 4 | 10.0 |

| Dipodomys agilis agilis | 4 | 10.0 |

| Peromyscus californicus insignis | 25 | 62.5 |

| Neotoma fuscipes macrotis | 7 | 17.5 |

Heteromyids are evidently absent from the upper parts of the

chaparral association, but cricetid rodents are common there beneath

heavy clumps of lilac and in the talus beneath oaks and bay

trees. The following list gives the mammals taken in the course

of about 200 trap nights in the granite talus one half mile northwest

of the mouth of Icehouse Canyon, at 5200 feet elevation.

[Pg 526]

Table 5.—Yield of 200 Trap-nights in the Upper Part of the Chaparral Association.

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Eutamias merriami merriami | 3 | 6.3 |

| Peromyscus boylii rowleyi | 38 | 79.2 |

| Neotoma lepida intermedia | 2 | 4.2 |

| Neotoma fuscipes macrotis | 5 | 10.4 |

The gray fox is the dominant carnivore of the chaparral association

and forages widely in all habitats.

Pinus ponderosa

P. lambertiana

Libocedrus decurrens

Abies concolor

Quercus Kelloggii

Ribes nevadense

Ribes Roezlii

Arctostaphylos sp.

Ceanothus cordulatus

The crest of the range, from the upper limit of the chaparral

association at roughly 6000 feet to the limited areas of boreal flora

above 8500 feet elevation, is covered by yellow pine forests. On the

desert slope of the range the coniferous forests which extend down

to about 6000 feet represent the best development of this association,

while the coniferous forests on the coastal side of the drainage divide

are often more or less diluted by chaparral elements. For example,

yellow pines on the Pacific face of Blue Ridge at 7000 feet elevation

often grow in association with scrub oak and mountain-mahogany.

Few mammals are resident in the typical yellow pine forest as

characterized by dense coniferous timber and little herbaceous or

brushy growth. Here most of the species recorded actually find

optimal conditions in an adjacent habitat. The forest probably

harbors surplus individuals from adjacent preferred habitats, or, as in

the case of chipmunks and ground squirrels, the forest often serves

as forage ground while nearby brushy areas are utilized for breeding

and shelter. The abundance of birds in the timber contrasts strikingly

with the paucity of mammals there. The lack of a seed-producing

understory, and the open duff-covered stretches of ground on

which rodents would be extremely vulnerable to predation, probably

in part account for the scarcity of rodents.

Within the general area encompassed by the yellow pine forest

there are two major habitats, namely coniferous forest and chaparral.[Pg 527]

The species of plants comprising the chaparral of the Transition

Life-zone are different from those comprising the chaparral of the

Upper Sonoran Life-zone on the Pacific slope. In the chaparral of

the Transition Life-zone, basin sagebrush and snowbrush grow in

extensive patches in clearings in the timber. Dense thickets of choke

cherry cover many damp hollows, and these thickets harbor the

houses of Neotoma fuscipes. The food and shelter afforded by these

chaparral areas importantly influence the local distribution of

rodents: for example, Dipodomys agilis and Perognathus californicus

in the yellow pine area are found only in association with chaparral,

being completely absent from wooded areas.

The severe winter weather in this association must force many of

the mammals into periods of inactivity. Probably during the long

periods in the winter when snow covers the ground the heteromyids

and sciurids remain below ground.

Pinus monophylla

Juniperus californica

Quercus dumosa var. turbinella

Purshia glandulosa

Fremontia californica

Cercocarpus ledifolius

Yucca Whipplei

In the San Gabriel Mountains this association is limited to the

desert slope and reaches its lower limit at the bases of the foothills

and extends up to the lower edge of the yellow pine forests. The

altitudinal extent of the pinyon-juniper association is from roughly

4000 to 6000 feet elevation.

Several habitats are evident within the pinyon-juniper belt. On

north slopes in the upper part of this association, scattered stands

of pinyon pines are found with dense patches of scrub oak intervening,

while on other such slopes a dense chaparral is present, consisting

primarily of scrub oak, mountain-mahogany, and California

slippery-elm. In this type of chaparral several hundred trap nights

yielded only two rodent species: Neotoma fuscipes simplex and

Peromyscus truei montipinoris. There are few pinyons on the south

slopes, especially in the lower parts of the association; many of these

slopes are clothed with an open growth of manzanita and yucca,

while northern exposures there support mostly scrub oak. Many

of the flats of the pinyon belt are grown to basin sagebrush.

Following is a list of the mammals taken in about 400 trap

nights at one locality in the pinyon-juniper association. The area

supported a mixed growth of pinyon, scrub oak, mountain-ma[Pg 528]hogany,

and antelope-brush, together with smaller brushy plants,

and was at the head of Grandview Canyon, at an altitude of roughly

5000 feet.

Table 6.—Yield of 400 Trap-nights in the Pinyon-juniper Association.

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Perognathus fallax pallidus | 3 | 11.5 |

| Dipodomys agilis fuscus | 9 | 34.6 |

| Peromyscus truei montipinoris | 10 | 38.5 |

| Neotoma fuscipes simplex | 4 | 15.4 |

Although Munz and Keck (1949:101) considered the pinyon-juniper

belt as one association, on the desert slope of the San

Gabriels pinyons and junipers do not generally grow on common

ground; but rather the juniper belt represents a well defined habitat

occurring between the pinyon covered slopes and the flats that support

Joshua trees. Because the mammalian populations of the

pinyon belt and the juniper belt are somewhat different, the mammals

of these areas are most conveniently taken up separately.

In the juniper belt the juniper tree is of marked ecologic significance;

the distribution of Peromyscus truei and Neotoma fuscipes

is determined here by the presence of junipers. At certain

times of year the fruit of this plant is eaten by coyotes, kangaroo

rats, and wood rats.

The list below indicates the results of approximately 500 trap

nights in the juniper belt near Mescal Canyon, between 4000 and

5000 feet elevation.

Table 7.—Yield of 500 Trap-nights in the Juniper Belt.

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Perognathus fallax pallidus | 16 | 16.7 |

| Dipodomys merriami merriami | 3 | 3.1 |

| Dipodomys panamintinus mohavensis | 36 | 37.5 |

| Peromyscus truei montipinoris | 22 | 22.9 |

| Peromyscus maniculatus sonoriensis | 12 | 12.5 |

| Neotoma lepida lepida | 2 | 2.1 |

| Neotoma fuscipes simplex | 2 | 2.1 |

| Onychomys torridus pulcher | 3 | 3.1 |

[Pg 529]

The biota of the washes that cut through the juniper belt in and

below many of the larger canyons differs from that of the surrounding

juniper-clad benches. Because the washes are in the same

geographic area as the juniper belt they are discussed together.

These washes on desert slopes are densely populated by rodents

derived from adjacent areas, and support vegetation typical of

higher floral belts in association with xerophytic, typically desert,

species. In a sense, the washes serve to mix up the mammals of adjacent

areas. For example, Onychomys torridus pulcher and Peromyscus

eremicus eremicus, which are mammals typical of the

desert, were found in Mescal Wash above their usual desert range;

and Peromyscus californicus insignis and Peromyscus boylii rowleyi,

which are chaparral inhabiting mammals, were found in the wash

far removed from their chaparral environment. Washes are evidently

effective agents in facilitating the dispersal of certain species

of mammals. It is easy to envision a species crossing hostile

habitats via dry washes to invade suitable niches in an area which

is geographically and ecologically isolated from the original home

of the species. Approximately 500 trap nights in Mescal Wash,

at 4100 feet elevation, in the lower edge of the juniper belt, yielded

the following mammals:

Table 8.—Yield of 500 Trap-nights in Mescal Wash (Desert Slope).

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Perognathus fallax pallidus | 5 | 4.5 |

| Dipodomys panamintinus mohavensis | 43 | 38.7 |

| Peromyscus californicus insignis | 3 | 2.7 |

| Peromyscus truei montipinoris | 1 | .9 |

| Peromyscus boylii rowleyi | 2 | 1.8 |

| Peromyscus eremicus eremicus | 28 | 25.0 |

| Peromyscus maniculatus sonoriensis | 23 | 20.5 |

| Onychomys torridus pulcher | 4 | 3.5 |

| Neotoma lepida lepida | 3 | 2.7 |

Dipodomys panamintinus mohavensis, Neotoma fuscipes simplex,

and Peromyscus truei montipinoris are probably the most characteristic

mammals of the pinyon-juniper association.

Bromus sp.

Artemisia tridentata

Chrysothamnus nauseosus

Purshia glandulosa

This association is found on only the crest and desert slope of the

range between 5000 and 8000 feet elevation. There it characteristically

occupies flats and clearings in the yellow pine forest and

pinyon-juniper woodland. The dominant plant of the association

is basin sagebrush, and in many places this plant forms mixed

growths with snowbrush and Haplopappus. The low brush of this

association is formed by closely spaced bushes with grasses growing

between.

Because of its limited occurrence in the San Gabriel Mountains,

this association there has relatively little effect on mammalian distribution.

Locally, nevertheless, the presence of this association

governs the distribution of certain mammals. For example, on Blue

Ridge, islands of sagebrush amid the conifers provide suitable

habitat for Dipodomys agilis perplexus and Perognathus californicus

bernardinus; and in Swarthout Valley D. a. perplexus, Reithrodontomys

megalotis longicaudus, and Lepus californicus deserticola are

seemingly restricted to the sagebrush flats.

Yucca brevifolia

Lycium Andersonii

Eriogonum fasciculatum

Tetradymia spinosa

Ephedra sp.

Larrea divaricata

This association is on the piedmont that dips toward the Mojave

Desert from the interior base of the San Gabriels. The widely

spaced Joshua trees with low bushes between, and the dry washes

breaking the level terrain below the mouths of canyons are typical

of this area. Field work was extended no farther down into the

desert than about the 3500 foot level, where this association was still

dominant.

Although the vegetation of this area is scattered and sparse, presenting

a barren and sterile aspect, the area supports a rather high

population of rodents. The soil at the bases of many large box-thorn- and

creosote-bushes is perforated by burrow systems of

Dipodomys panamintinus or Dipodomys merriami, and those burrows

abandoned by kangaroo rats are used as retreats by Onychomys

torridus and Peromyscus maniculatus. The mammals of this associ[Pg 531]ation

are all characteristic of the fauna of the Mojave Desert, with

the ranges of such species as the coyote and jack rabbit extending

well up the desert slope of the mountains.

The mammals listed below were taken in 1948 in roughly 400

trap nights in the Joshua belt, at an elevation of 3500 feet, one mile

below the mouth of Graham Canyon.

Table 9.—Yield of 400 Trap-nights in the Joshua Tree Belt.

| Number | Per cent of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Dipodomys panamintinus mohavensis | 36 | 59.0 |

| Dipodomys merriami merriami | 15 | 24.6 |

| Onychomys torridus pulcher | 4 | 6.6 |

| Peromyscus maniculatus gambeli | 6 | 9.8 |

Populations of Dipodomys merriami and D. panamintinus fluctuate

widely, possibly in response to weather cycles. In November of

1948 trapping in the Joshua belt showed that panamintinus outnumbered

merriami approximately three to one, whereas in December

of 1951, after a succession of unusually dry years, merriami was the

more numerous. Further, merriami occurred in the lower parts of

the juniper belt in 1951 where in 1948 it seemed to be absent.

Dipodomys merriami merriami and Onychomys torridus pulcher

are diagnostic of the Joshua tree woodland association in the San

Gabriel Mountains area, since few individuals of either species occur

outside of this association.

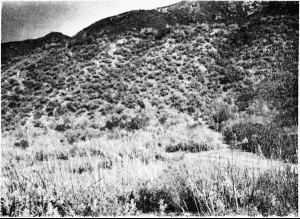

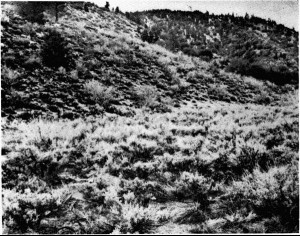

white sage, and coastal sagebrush. The adobe banks beyond are

grown mainly to white sage. Small mammals are abundant in this association,

with Dipodomys agilis, Perognathus fallax, and Sylvilagus audubonii being

characteristic of the area. Photo March 25, 1952, at mouth of San Antonio

Canyon, 1800 feet elevation.

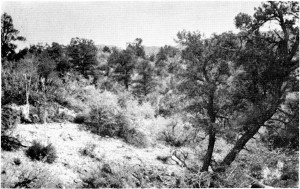

wash is a distinct habitat in the coastal sage scrub association, and is the

preferred habitat of Peromyscus eremicus fraterculus and Neotoma lepida

intermedia. These rodents find shelter in the piles of boulders. Photo February

2, 1952, in San Antonio Wash, at 1700 feet elevation.

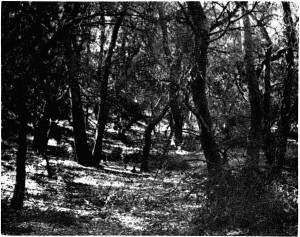

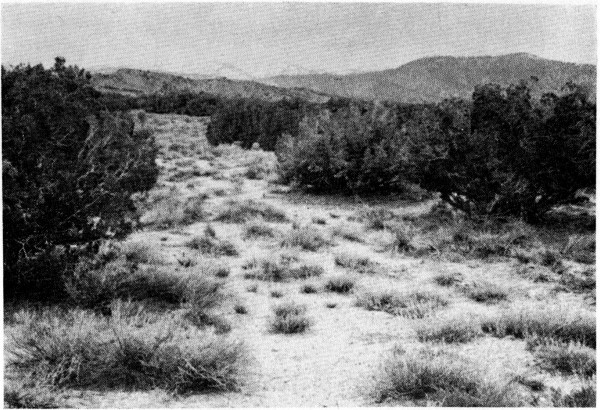

the woodland lacks shelter for ground-dwelling rodents and the population of

rodents is small. Peromyscus boylii rowleyi is the commonest rodent. Photo

March 10, 1952, in Evey Canyon, 2700 feet elevation.

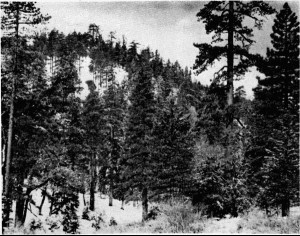

white fir, and black oak. Photo April 27, 1952, at Big Pines, 6800 ft. elevation.

stand of basin sagebrush. Dipodomys agilis perplexus and Reithrodontomys

megalotis longicaudus occur in this association, and Peromyscus truei montipinoris

is present where this association merges with the pinyon-juniper association.

Photo April 27, 1952, in Swarthout Valley, 6200 feet elevation.

upper part of the pinyon-juniper association, and is the habitat of Neotoma

fuscipes simplex, Peromyscus truei montipinoris, and Eutamias merriami

merriami. Photo April 27, 1952, in Sheep Creek Canyon, 5500 feet elevation.

pinyon-juniper association. Perognathus fallax pallidus, Dipodomys panamintinus

mohavensis, and Peromyscus truei montipinoris are typical of this

area. Photo April 27, 1952, at Desert Springs, 4300 feet elevation.

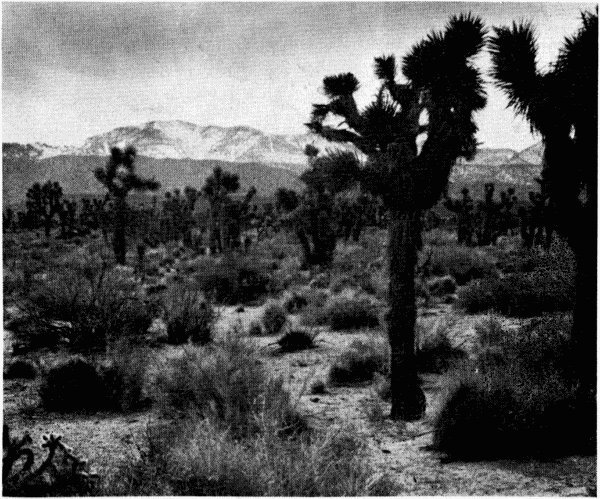

Dipodomys panamintinus mohavensis, D. merriami merriami, and Onychomys

torridus pulcher. Photo January 4, 1952, 6 miles east and 2 miles south Llano,

3600 feet elevation.

Accounts of Species

The opossum is common in and near small towns and cultivated

areas at the Pacific base of the mountain range and does not thrive

away from human habitation; extensive trapping in the coastal sage

and chaparral belts produced no specimens except immediately adjacent

to citrus groves. Pequegnat (1951:47) mentions that opossums

in the Santa Ana Mountains of southern California are in the

lower parts of the larger canyons, especially near human habitation.

Specimens examined.—Los Angeles County: Claremont, 1600 ft.,

2 (PC).

Workings of moles were found on the Pacific slope of the mountains

from 1600 feet at Claremont up to 7500 feet on Blue Ridge,

and on the Pacific slope beneath basin sagebrush in Cajon Canyon

one mile from desert slope Joshua-tree flats, but not on the desert

slope, although moles probably occur on that slope in some of the

places where there is suitable habitat.

Near Camp Baldy in the sandy soil beneath groves of alders

moles seemed to be especially abundant. Although common on the

coastal face of the range, moles shunned compact, dry, or rocky

soils. In the greasewood chaparral one-half mile west of the mouth

of Palmer Canyon, where the soil was hard and rocky, mole tunnels

were in soft soil that had accumulated at the edge of a fire road beneath

a steep road cut. The assumption is that this accumulation

contained insects attractive, as food, to the moles.

Specimens examined, 2: Los Angeles County: Camp Baldy, 4200 ft.,

1(PC); Claremont, 1600 ft., 1(PC).

Jackson (1928:124) recorded a specimen from Camp Baldy,

4200 feet, San Antonio Canyon.

Both of my specimens were taken amid riparian growth on the

Pacific slope of the range.

Specimens examined, 2: Los Angeles County: San Antonio Canyon, 3500

ft., 1; Cobal Canyon, 5 mi. N Claremont, 1800 ft., 1 (PC).

One was taken in 1946 beneath a woodpile on the campus of

Norton School, two miles northeast of Claremont, and examined

by Dr. W. E. Pequegnat.

A female was taken in lower San Antonio Canyon, 2800 feet elevation,

on September 27, 1951.

This species was observed and collected at several stations ranging

from 2800 feet elevation in San Antonio Canyon, to Blue Ridge

at 8200 feet, and down the desert slope to 6000 feet at Jackson Lake.

This distribution encompasses most of the chaparral and yellow

pine forest associations. Within these areas, however, this bat

shows marked habitat preferences.

Woodland habitats seem to be preferred by evotis. At several

ponds in lower San Antonio Canyon this bat was observed repeatedly

as it foraged over the water and coursed low between rows of

alders and Baccharis. At Blue Ridge in September, 1951, these

bats foraged approximately six feet above the ground beneath the

canopy of coniferous foliage and between the trunks of the trees.

Most of the bats were taken by stretching fine wires above the

surface of a pond as outlined by Borell (1937:478). Collecting was

generally carried on until at least 11:00 p. m., and the time at which

each bat was taken at the pond was recorded, thereby making possible

a rough estimate of the pre-midnight forage period of each

bat commonly collected at the ponds. Usually bats taken at the

start of their supposed forage period had empty or nearly empty

stomachs, whereas those taken towards the end of their forage

period had full or nearly full stomachs. M. evotis usually first appeared

just at dark, well after the pipistrelles and California myotis

had begun foraging. The forage period of evotis seemed to begin

approximately 30 minutes after sunset and to end approximately

two and one-quarter hours later.

Individuals of this species were taken from May 4, to October

14, 1951. A female taken on May 19, 1951, in San Antonio Canyon,

carried one minute embryo, and one taken in the same locality on

June 8, had one embryo four millimeters in length.

Specimens examined.—Total, 12, distributed as follows: Los Angeles

County: San Antonio Canyon, 2800 ft., 11; Claremont, 1100 ft., 1 (P.C.).

Although seldom found to be plentiful, this bat was recorded

from many points on both the coastal and desert slopes of the

mountains. Specimens were taken in the chaparral association in

San Antonio Canyon, near Jackson Lake among yellow pines, and

in Mescal Canyon at the upper limit of the Joshua tree woodland.

Bats, probably volans, were noted over sage flats at 8000 feet elevation

on Blue Ridge. The only place where these bats appeared to

be numerous was Jackson Lake on the interior slope; there, on September

19, 1951, volans appeared with the pipistrelles, and was the

most common bat before dark.

An individual of this species taken on October 28, 1951, in a

short mine-shaft in the pinyon belt at the head of Grandview

Canyon was slow in its movements and felt as cold as the walls

of the tunnel. It was late afternoon and the temperature outside the

cave was below 40°F. The floor of the tunnel was covered with

the hind wings of large moths of the genus Catocala; volans probably

hung in the cave while eating them.

The series of volans from the San Gabriels shows that the two

color phases of this bat both occur in the area. Two specimens from

Jackson Lake contrast sharply with the rest of the series in their

dark coloration. Benson (1949:50) states that color variation in a

series of volans from a given locality may be striking.

This bat was collected in San Antonio Canyon from 50 minutes

after sundown to two hours and 40 minutes after sundown. In this

area these bats did not visit the ponds in large numbers as they

seemed to do on the desert slope.

A female taken on May 29, 1951, contained one embryo nearly

at term.

Specimens examined.—Total, 9, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

Mescal Canyon, 8 mi. E and 5 mi. S Llano, 4900 ft., 1; 3 mi. W Big Pines,

Swarthout Valley, 6000 ft., 3; San Antonio Canyon, 2800 ft., 5.

On the Pacific face of the mountain range this bat was recorded

commonly below approximately 5000 feet elevation, where it seemed

to be most common in the oak woodland of canyons. On the desert

slope it was collected at Jackson Lake in yellow pine woodland, in

Mescal Canyon in the juniper belt, and bats presumably of this[Pg 535]

species were observed at several points in the pinyon-juniper

woodland.

Individuals of this species were often observed foraging from

five to ten feet above the ground around the alders and Baccharis

near San Antonio Creek, but they did not fly so low or so near the

vegetation as did Myotis evotis. Here they were taken from 18

minutes to 55 minutes after sunset; this indicates an early and short

forage period.

This bat may be active even in winter. On February 8, 1952, in

lower San Antonio Canyon, a bat, probably of this species, was noted

foraging; and collecting in early November, 1951, yielded specimens.

On May 22, 1951, a female obtained in San Antonio Canyon had

one five-millimeter embryo, and subsequently all the females examined

had embryos until June 12, when collecting was discontinued.

Specimens examined.—Total, 16, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

Mescal Canyon, 4800 ft., 2; Jackson Lake, 6000 ft., 1 (PC); San Antonio

Canyon, 3900 ft., 1; San Antonio Canyon, 2800 ft., 12.

This is the most obvious if not the most common bat of the lower

coastal slopes of the San Gabriels. In the spring and fall of 1951

individuals were noted from 1700 feet in the coastal sage scrub association

to the white fir forests on Blue Ridge at 8200 feet elevation

and were commonest in the rocky canyons of the lower Pacific slope

below 4000 feet, and usually foraged near the steep canyon sides

high above the canyon bottoms.

Pipistrelles were generally the first bats to appear in the evening,

although the times of their appearance were irregular. In April

and May, in lower San Antonio Canyon, they appeared from 28

minutes before sunset to 30 minutes after sunset, with the average

time of appearance eight and one-half minutes after sunset. Like

Myotis californicus this pipistrelle seemed to have a short and early

foraging period. No pipistrelles were recorded at ponds later than

one hour and five minutes after sunset, and usually they were not

seen later than 40 minutes after sunset. Most of the specimens taken

later than one half hour after sunset had full stomachs. More

than 50 pipistrelles were captured at the ponds in San Antonio

Canyon; six were kept for specimens. This species is probably

present in the area throughout the winter. Pipistrelles were active[Pg 536]

in early April in Evey Canyon, were observed in early November

in San Antonio Canyon, and on January 26, 1952, an individual was

noted foraging near the mouth of Palmer Canyon. They are probably

not active in winter on the colder desert slope of the mountains.

Pipistrelles often foraged in loose flocks of about half a dozen

individuals. On many occasions these groups were first seen foraging

high up above the canyon bottom, then, as it grew darker, they

descended and foraged within 50 or 100 feet of the floor of the

canyon. Immediately before dark these groups seemed to have

forage beats; one minute several pipistrelles would be overhead,

and the next minute none would be in sight.

A female taken in San Antonio Canyon on June 8, 1951, contained

two five-millimeter embryos.

Specimens examined.—Total, 6, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

San Antonio Canyon, 2800 ft., 5; Evey Canyon, 2400 ft., 1.

This species was common in the spring and autumn of 1951 from

the lower edge of the yellow pine forest down into the belt of Joshua

trees. In early April on the desert slope at 4800 feet in Mescal

Canyon, pipistrelles foraged on evenings when it was windy but

not cold. On cold evenings (when the temperature was below

roughly 45°F) none was seen. On windy nights the pipistrelles

often forsook their usual high forage habits and foraged 15 feet

or so above the ground where the vegetation and outcrops of rock

broke the force of the wind. In 1951 no pipistrelles were noted on

the desert slope later than October 15.

Specimens examined.—Los Angeles County: Mescal Canyon, 4800 ft., 4.

This bat was on the coastal slope from the sage scrub association

at 1100 feet, up to 8000 feet on Blue Ridge, and on the desert slope

down to the upper edge of the Joshua tree belt at 4800 feet in

Mescal Canyon. It was the most common bat at the ponds in San

Antonio Canyon in May and June of 1951, but in September and

October of the same year none was obtained there.

On the Pacific slope of the San Gabriels the big brown bats segregate

according to sex in the spring, the males occupying the foothills

and mountains and the females the level valley floor at the coastal[Pg 537]

base of the range. Of 70 big brown bats captured in May and

June of 1951, at the ponds in San Antonio Canyon, only one was a

female. A large colony of more than 200 individuals in a barn near

Covina, in the citrus belt, was composed of only females.

Times of capture of this bat at the ponds in San Antonio Canyon

ranged from ten minutes after sunset to two hours and thirty minutes

after sunset. Generally these bats came to the ponds in groups

of several individuals, and often more than a dozen were captured

in the course of an evening's collecting.

Specimens examined.—Total, 7, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

Mescal Canyon, 4800 ft., 1; San Antonio Canyon, 2800 ft., 2; Covina, 1100 ft.,

4 (2PC).

One female was taken on September 30, 1951, in San Antonio

Canyon, at 2800 feet elevation. The descriptions which the citrus

growers of the Claremont and Glendora vicinity give of the bats

they find occasionally hanging in their citrus trees accurately describe

this species. Its seasonal occurrence there is unknown.

Specimens were collected in spring in 1951 at elevations of 2800

and 3200 feet in San Antonio Canyon, on the coastal slope, and in

Mescal Canyon at 4900 feet, on the desert slope. Large, fast flying

bats, probably of this species, were seen at Jackson Lake, 6000 feet

elevation, on October 15, 1951.

Hoary bats are present in the San Gabriels in the fall, winter, and

spring. In 1951 the last spring specimen was taken on June 11,

in Mescal Canyon; then collecting was discontinued until late September

when the first hoary bat was taken on the thirtieth of that

month. From this date on into the winter hoary bats were recorded

regularly. They seemed to be as common in early June as in most

of April and May; possibly some remain in the San Gabriels throughout

the summer.

In spring these bats seem to segregate by sex; of twelve kept as

specimens and at least an equal number captured and released only

one was a female. All were captured above 2800 feet.

Hoary bats seem to have a long pre-midnight forage period, having

been captured at ponds from 21 minutes after sunset, to three hours

and 26 minutes after sunset. Generally those taken early had empty[Pg 538]

stomachs and those taken later had full stomachs. On the night of

May 24, 1951, a hoary bat captured two hours and five minutes

after sunset had only a partially full stomach.

On May 25, 1951, an unusual concentration of hoary bats was

observed at a pond at about 3200 feet elevation, in San Antonio

Canyon (Vaughan, 1953). The day had been clear and warm, one

of the first summerlike days of spring. Beginning at 30 minutes

after sundown hoary bats were collected until two hours and 35

minutes after sundown; in this period 22 were caught and at least

as many more observed. Many were released after being examined,

whereupon they hung on the foliage of nearby alders to rest and

dry themselves. This concentration of hoary bats may have been

due to a sudden beginning of migration with a resultant concentration

of bats at certain altitudinal belts. The warm weather might

have set off the migration. On evenings that followed subsequent

hot days no such concentration of hoary bats was seen. B. P. Bole

(Hall 1946:156) observed a concentration of hoary bats on August

28, 1932, in Esmeralda County, Nevada.

Several captive Myotis californicus in a jar next to a pond in San

Antonio Canyon set up a squeaking which seemed to attract a hoary

bat. Repeatedly the large bat swooped over the jar.

Specimens examined.—Total, 12, distributed as follows: Los Angeles

County: Mescal Canyon, 4900 ft., 2; San Antonio Canyon, 3200 ft., 2; San

Antonio Canyon, 2800 ft., 8.

The pallid bat is probably the most common and characteristic

bat of the citrus belt at the Pacific base of the mountains. Only

once, on May 4, 1951, was this bat taken in the mountains. On

that night two individuals were collected at 2800 feet in San Antonio

Canyon. All of the other specimens and observations were from

colonies in old barns and outbuildings in the citrus belt where these

bats are found in spring, summer, and fall.

The impression gained by examining many mixed colonies of

Antrozous and Tadarida was that the former greatly outnumbered

the latter. For example, a small colony of bats in an old barn near

San Dimas Wash consisted of about thirty pallid bats and five freetails.

Large numbers of wings of moths of the family Sphingidae, and

legs and parts of the heads of Jerusalem crickets (Stenopelmatus

fuscus)[Pg 539]

were beneath an Antrozous night-roosting place in a barn

near Upland.

Pallid bats were collected in 1951, from April 16 to October 17

but probably were active in the area into November.

Each of two pregnant females taken two miles northeast of San

Dimas on April 20, 1951, carried two embryos 4 millimeters long.

Specimens examined.—Total, 6, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

2 mi. NE San Dimas, 1200 ft., 2 (1PC); Ontario, 1100 ft., 4 (3PC).

This bat, regularly met with in the citrus belt at the coastal base of

the range, occurred in small numbers with colonies of Antrozous,

and was once found with a colony of Eptesicus near Covina. None

of the females taken in April 1951 was pregnant.

Specimens examined.—Los Angeles County: 2 mi. NE San Dimas, 1200

ft., 4.

H. W. Grinnell (1918:373) mentioned individuals collected at

Sierra Madre (at the coastal base of the San Gabriels west of the

study area), and Sanborn (1932:351) reported specimens from

Covina and Azusa. Probably this bat occurs locally all along the

coastal base of the range.

This species was found in the coastal sage belt from Cajon Wash

west to San Gabriel Canyon and was most plentiful in thin stands

of sagebrush, and in and around citrus groves. Because of their

preference for semi-open country, jack rabbits are absent from

much of the coastal belt of sagebrush where the brush is fairly

continuous, and they never were observed in the chaparral association.

Coyotes catch many jack rabbits and regularly forage around the

foothill borders of the citrus groves for cottontails and jack rabbits.

A female examined on February 19, 1951, was pregnant, and one

taken on March 15, 1951, carried three small embryos.

Specimens examined.—San Bernardino County: 2 mi. NW Upland, 1600

ft., 3 (PC).

There was sign of jack rabbits along the desert slope of the San

Gabriels up to about 6700 feet, one-half mile west of Big Pines.

They were fairly common in the Joshua tree belt, occurred less

commonly in the juniper belt, and were present locally in small

numbers in the pinyon-juniper association.

The population seemed to be at a low ebb from 1948 to 1952,

when field work was done on the desert slope. I often hiked for

an hour or more on the desert or juniper-covered benches without

seeing a jack rabbit. The species was commoner in washes where

as many as eleven were noted in two hours' hiking.

In December, 1951, below Graham Canyon, the leaves on large

areas of many nearly recumbent Joshua trees had been gnawed down

to their bases, and jack rabbit feces covered the ground next to these

gnawings. Probably the Joshua tree is an emergency food used by

the rabbits only when other food is scarce.

In years when the population of jack rabbits is not low they serve

as a major food for coyotes. In the Joshua tree belt below Mescal

Canyon, jack rabbit remains were fairly common in coyote feces,

and tracks repeatedly showed where some coyote had pursued a

jack rabbit for a short distance. A large male bobcat trapped in

the juniper belt in Graham Canyon had deer hair and jack rabbit

remains in its stomach.

Specimens examined.—Total, 7, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

6 mi. E and 1 mi. S Llano, 3500 ft., 4; Mescal Canyon, 4800 ft., 3.

Cottontails are common in the coastal sage scrub association and in

and around citrus groves, but generally penetrate the mountains

no farther than the lower limit of the chaparral association. They

are everywhere on coastal alluvial slopes, except in the barren

washes, and prefer patches of prickly-pear and often are loathe to

leave its protection. After completely destroying a large patch of

prickly-pear in the course of examining a wood rat house in the

center of the cactus, I found hiding, in the main nest chamber of the

house, a cottontail that dashed from its hiding place only when

poked forceably with the handle of a hoe.

Cottontails are seldom above the sage belt in the chaparral associations,

although along firebreaks and roads they occasionally

occur there. Habitually cottontails escape predators in partly open[Pg 541]

terrain offering retreats such as low, thick brush, rock piles, and

cactus patches; but on open ground beneath dense chaparral, cottontails

may be vulnerable to predation.

Examinations of feces and stomach contents of the coyote reveals

that it preys more heavily on cottontails than on any other wild

species. Remains of several cottontails eaten by raptors were found

in the sage belt.

In April, 1951, many young cottontails were found dead on roads

in the sage belt, and a newly born cottontail was in the stomach of

a coyote trapped four miles north of Claremont, on February 7, 1952.

Specimens examined.—Total, 3, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

mouth of San Antonio Canyon, 2000 ft., 1 (PC). San Bernardino County:

2 mi. NW Upland, 1600 ft., 2 (PC).

This subspecies was recorded on the interior slope from 5200 feet

elevation, as at the head of Grandview Canyon, down into the

desert, and was common in the sagebrush flats of the upper pinyon-juniper

association. Piles of feces under thick oak and mountain-mahogany

chaparral indicated that the rabbits often sought shelter

there. Adequate cover is a requirement for this rabbit on the

desert slope of the San Gabriels; in the juniper and Joshua tree

belts the species occurs in washes where there is fairly heavy

brush, and only occasionally elsewhere. In the foothills, when

frightened from cover in one small wash cottontails often run up

over an adjacent low ridge and seek cover in the brush of the next

wash. In the wash below Graham Canyon tracks and observations

showed that cottontails were taking refuge in deserted burrows of

kit foxes.

In the pinyon-juniper association cottontails and jack rabbits probably

occur in roughly equal numbers, but in the Joshua tree belt

cottontails seem far less numerous than jack rabbits. In the course

of a two hour hike in lower Mescal Wash, at about 3500 feet, eleven

jack rabbits and two cottontails were noted.

Specimens examined.—Total, 2, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

6 mi. E and 1 mi. S Llano, 3500 ft., 1; Mescal Canyon, 4800 ft., 1.

Brush rabbits inhabit the Pacific slope of the mountains from

about 1200 feet in the coastal sagebrush belt up to at least 4500

feet in the chaparral, and are the only lagomorphs found commonly

[Pg 542]

above the lower edge of the chaparral association. Here they were

often on steep slopes beneath extensive and nearly impenetrable

tracts of chaparral.

The ecologic niche of the brush rabbit is in brush where the

plants form continuous thickets with little open ground. In the

coastal sagebrush flats, areas supporting only scattered bushes are

uninhabited by brush rabbits, while areas grown to extensive tracts

of brush harbor them. When the brush rabbit's mode of escape

from its enemies is considered, the reason for their habitat preference

becomes more clear. Almost invariably these rabbits seek

escape by running through the densest portions of the brush, never

appearing in the open; in this way they travel quickly away from

the source of danger without being observed. Because they avoid

being seen in the open, and do not seek safety largely through

running ability, they need continuous stretches of brush for escape.

While hunting in the coastal sagebrush belt I have repeatedly seen

frightened brush rabbits turn and dart beneath the bushes a few

feet from a human being rather than be driven into the open.

A great horned owl shot in March, 1951, in the sage belt, had

in its stomach the remains of a freshly killed adult brush rabbit.

Although coyotes and brush rabbits often occur in the same general

sections of the sage flats, remains of these rabbits have been notably

scarce in coyote feces from these areas. This is probably because

the coyote hunts along clearings and in open brushland, precisely

the type of habitat avoided by brush rabbits.

Gray squirrels were on both slopes of the San Gabriels in oak

woodland. A gray squirrel was observed in April of 1948, as it

climbed a telephone pole adjacent to an orange grove near Cucamonga.

This, and one noted bounding up a slope of greasewood

chaparral near Cattle Canyon, were the only gray squirrels seen

in areas which were not grown to oaks or adjacent to oak woodland.

In the lower foothills gray squirrels were invariably found in association

with valley oak, this plant forming limited woodland areas

in canyon bottoms. In the upper chaparral association the squirrels

frequented the large scrub oaks growing on talus slopes and canyon

sides. In the yellow pine woodland, gray squirrels are restricted

to black oaks, often where they formed mixed stands with the coni[Pg 543]fers.

On the interior slope these squirrels were found only at the

lower edge of the yellow pine woodland where black oaks are

common. There, in the vicinity of Big Pines, they were present

between roughly 5800 and 7000 feet, while on the Pacific slope they

inhabited oak woodland from 1600 feet to about 7000 feet elevation.

In Live Oak Canyon in December of 1950, tracks indicated that

a bobcat had killed a gray squirrel in a small draw beneath the oaks.

In Evey Canyon on March 6, 1951, while watching for bats at late

twilight, I observed a gray squirrel traveling through the branches

of a nearby oak. A great horned owl glided into the oak in an

attempt to catch the squirrel, which leaped quickly into a dense

mass of foliage and escaped. For roughly ten minutes the owl

perched in the oak watching its intended prey, then flew off down

the canyon amid frantic scolding by the squirrel.

On March 17, 1951, a female gray squirrel taken at about 3500 feet

elevation in San Antonio Canyon contained two embryos, each

roughly 40 millimeters long.

From the coastal sage belt, into the yellow pine forest of the

Pacific slope, this species is common on land cleared by man or

disturbed in the course of construction, or on severely eroded

slopes where the original climax vegetation is partly or completely

absent. Thus in the sage belt, ground squirrels live along dirt roads

through the brush, on the heavily eroded banks often found in

the foothills, on land grazed closely by sheep, and in those parts

of major washes such as San Antonio and Cucamonga washes

where scatterings of huge boulders offer prominent vantage points.

In San Antonio Canyon Spermophilus was restricted to the vicinity

of roads and firebreaks, and an especially large colony of at least

forty individuals lived at a dump one mile southwest of Camp Baldy

at about 4500 feet elevation. Ground squirrels used burned stems

of large laurel sumac as observation posts. Because of a preference

for open areas offering unobstructed outlooks, ground squirrels

originally probably did not penetrate the main belt of heavy chaparral

on the Pacific slope of the range except in some of the large

washes.

In the spring of 1951 and the preceding summer there was a

marked increase in the ground squirrel population near Padua Hills[Pg 544]

as a result of sheep grazing on approximately one-half square mile

of sage land. Grasses and smaller shrubs were eaten down to the

ground, and in some places coastal sagebrush and Haplopappus

were killed by browsing and trampling. The area formerly had a

sparse growth of bushes with intervening growths of tall grasses

and one colony of perhaps 20 ground squirrels; but after the sheep

grazing the area was open brushland with large clear spaces on

which the herbage was trimmed to the ground, and had at least four

colonies of ground squirrels as large as the first. Also there were

other ground squirrels established in various parts of the area.

Probably the dry weather in the winter of 1950-51 with consequent

retardation of the vegetation aided the spread of the squirrels in

this area.

In the sage belt, most ground squirrels are dormant by December.

In 1951, after a mild winter, squirrels were noted on January 25

near Padua Hills. On February 8, 1951, males in breeding condition

were collected, and on March 16, a female taken near San Antonio

Wash carried three small embryos. In early March of 1951, ground

squirrels were active at 4500 feet elevation in San Antonio Canyon.

Specimen examined.—Los Angeles County: 1 mi. S and 2 mi. E Big Pines,

8000 ft., 1.

This ground squirrel inhabited the desert slope of the mountains

up to 5000 feet elevation, and was most common in the juniper belt;

burrows often were made under large junipers. In May, 1949,

ground squirrels were common in the rocks adjacent to Mescal Wash

at an elevation of 4500 feet. In an apple orchard near Valyermo,

squirrels fed on the fallen fruit in early November of 1951.

No squirrel was seen in December, January, and February, indicating

that all were below ground in winter.

Specimen examined.—San Bernardino County: Desert Springs, 4000 ft., 1

(PC).

Antelope ground squirrels were common in the Joshua tree

woodland where they were noted up to 4500 feet elevation in

Graham Canyon. None was found on the pinyon slopes, possibly

because of the competition offered there by Eutamias merriami,

or because the rocky nature of the soil there rendered burrowing

difficult.

[Pg 545]

Although observed less often in winter than in summer, this

species is active all year. On February 6, 1949, in Mescal Wash,

an antelope ground squirrel was foraging over the snow which

was at least six inches deep. These squirrels were attracted to the

carcasses of rodents used as bait for carnivore sets, and caused a

good deal of trouble by disturbing the traps.

Antelope ground squirrels used the topmost twigs of box-thorn

bushes extensively as lookout posts, and many of their burrows were

at the bases of these thorny bushes. This habit of regularly using

observation posts is well developed in each species of ground

squirrel found in the San Gabriels.

Specimens examined.—Los Angeles County: 6 mi. E and 1 mi. S Llano,

3500 ft., 2.

This chipmunk was characteristic of the most boreal parts of the

San Gabriel Mountains. It was recorded from 6800 feet elevation at

Big Pines, to an altitude of approximately 9800 feet near Mt. San

Antonio, and was common where coniferous timber was interspersed

with snowbrush chaparral. In upper Icehouse Canyon and near

Telegraph Peak these chipmunks were associated with lodgepole

pines and chinquapin, and one mile east of Mt. San Antonio individuals

were often observed in thickets of manzanita. This chipmunk

usually shunned pure stands of coniferous timber except as

temporary forage ground.

On Blue Ridge these chipmunks used the uppermost stems of

snowbrush as vantage points, and when disturbed ran nimbly over

thorny surfaces of the brush in seeking refuge in the tangled growth.

In early November of 1951, these animals were not yet in hibernation

on Blue Ridge. They were noted on November 6, after the

season's first snows had melted; on November 13, however, a cold

wind with drifting fog kept most of them under cover, and only two

were noted in the course of the day.

Specimen examined.—Los Angeles County: 1 mi. S and 2 mi. E Big Pines,

8100 ft., 1.

The lower limit of the range of this species, on the coastal face of

the range, is roughly coincident with that of manzanita—that is to

say, it begins in the main belt of chaparral above the lower foothills.[Pg 546]

E. merriami seems to reach maximum abundance amid the granite

talus, and scrub oak and Pseudotsuga growth at the upper edge of

the chaparral association. It was absent, however, from all but the

lower fringe of the yellow pine forest association.

On the desert slope merriami was partial to rocky areas in the

pinyon-juniper association but was also in the black oak woods on

the Ball Flat fire road near Jackson Lake. Nowhere was Eutamias

merriami and E. speciosus observed on common ground.

Specimens examined.—Los Angeles County: San Antonio Canyon, 5500 ft.,

2 (1 PC).

No specimens of this species were taken in the field work in

the San Gabriels, nor did I find any rangers or residents of the

mountains who had seen flying squirrels in the area. Nevertheless

sign found in the white fir forests in the Big Pines area indicated

that flying squirrels may occur there. On a number of occasions

dissected pine cones were noted on the horizontal limbs and bent

trunks of white firs. These cones were too large to have been

carried there by chipmunks, and gray squirrels were often completely

absent from the areas. I suspect that extensive trapping in

the coniferous forests of the higher parts of the mountains would

produce specimens of flying squirrels. Willett (1944:19) mentions

that flying squirrels probably occur in the San Gabriel Mountains.

This gopher was found below about 5000 feet elevation in disturbed

or open areas from Cajon Wash at Devore westward all

along the coastal base of the San Gabriel Range. In the lower

part of the chaparral belt the gopher evidently was absent from

the chaparral-covered slopes, but was common along roads and

on fire trails.

Burt (1932) and von Bloeker (1932) discuss the distribution

of the three subspecies of this species, pallescens, neglecta, and

mohavensis, which are in the San Gabriel Mountains area, and

Burt indicates that pallescens grades toward mohavensis in the

southern part of Antelope Valley.

In the forests of yellow pine and white fir of the higher parts of

the San Gabriel Mountains the workings of this gopher were common,

and sign of its presence was found above 4500 feet on both

slopes of the mountain range. The rocky character of the coastal

slope seems to limit the occurrence of gophers, for they are not

continuously distributed there. On the desert slope they occur locally

down into the pinyon-juniper belt.

In the vicinity of Big Pines, on the interior slope, these gophers

preferred broken forest where snow brush or other brush occurred;

their workings, however, were also found beneath groves of conifers

and black oaks. The abundance of earth cores resting on the duff

indicated that this species is active in the snow in winter.

Specimens examined.—Total, 5, distributed as follows: Los Angeles County:

2 mi. E Valyermo, 4600 ft., 2; 3 mi. W Big Pines, 6000 ft., 1; 1 mi. S and 2 mi.

E Big Pines, 8000 ft., 2.

One specimen of this subspecies was taken on December 31, 1951,

in the Joshua tree belt, eight miles east of Llano, 3700 feet elevation.

This pocket mouse is restricted to the coastal sage scrub association,

and was recorded from Cajon Wash west to Live Oak Canyon.

The mouse does not inhabit even the lower edge of the chaparral

belt, but in the coastal sage flats is usually the most abundant rodent.