The Project Gutenberg eBook of A Bilateral Division of the Parietal Bone in a Chimpanzee; with a Special Reference to the Oblique Sutures in the Parietal

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: A Bilateral Division of the Parietal Bone in a Chimpanzee; with a Special Reference to the Oblique Sutures in the Parietal

Author: Aleš Hrdlička

Release date: October 19, 2010 [eBook #34101]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Larry B. Harrison and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A BILATERAL DIVISION OF THE PARIETAL BONE IN A CHIMPANZEE; WITH A SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OBLIQUE SUTURES IN THE PARIETAL ***

A Bilateral Division of the Parietal Bone

in a Chimpanzee; with a Special Reference

to the Oblique Sutures in the

Parietal.

By Aleš Hrdlička

AUTHOR'S EDITION, extracted from BULLETIN

OF THE

American Museum of Natural History,

Vol. XIII, Article XXI, pp. 281–295.

New York, Dec. 31, 1900.

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

[Pg 281]

Article XXI.—A BILATERAL DIVISION OF THE

PARIETAL BONE IN A CHIMPANZEE; WITH

SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OBLIQUE SUTURES

IN THE PARIETAL.

By Aleš Hrdlička.

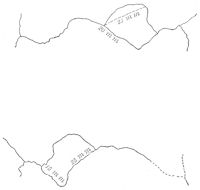

The first to describe a case of division of the parietal bone in

apes was Johannes Ranke, in 1899.

[1] The skull in question is

that of an adolescent female orang, one of 245 orang crania in

the Selenka collection in the Munich Anthropological Institute.

The abnormal suture divides the right parietal into an upper

larger and a lower smaller portion. "The suture runs nearly

parallel with the sagittal suture," but, as the illustration shows

(Fig. 1), it descends in its posterior extremity towards the temporo-parietal

suture, and terminates in this a few millimetres in

front of the lambdoid suture. The abnormal suture shows but

little serration, and the articulation of the two divisions of the

parietal bone is squamous in character, the lower portion overlapping

the upper. Below the junction of the abnormal with the

coronal suture, the latter takes a pronounced bend forward. A

similar bend in the coronal suture is present in the same specimen

on the left side. This is common among the other orang

skulls in the collection. The portions of the coronal suture below

and above the bend differ somewhat in character.

Besides the above-mentioned complete division, Ranke found

among the 245 orang skulls 13 with incomplete division of the

parietal bone. The division consisted invariably of a longer or

shorter remnant of a horizontal "parietal suture," ending in the

coronal suture at the top of the bend above referred to. A similar

anterior remnant of an abnormal parietal suture was found by

Ranke in a young chimpanzee skull; but the author questions

the word "chimpanzee," which evidently means that the identity

of the skull is somewhat doubtful.

In consequence of his finds, Ranke believes both complete

and incomplete divisions in the parietal bone to be much more

[Pg 282]

frequent in the orang than in man.

[2] He also thinks that the

bend usually present in the coronal suture in the orang signifies

that, "even where there are no traces of a parietal suture, such a

suture has actually existed in an earlier stage of development."

This implies the development of the adult parietal bone in the

orang from two original

segments, one

above the other.

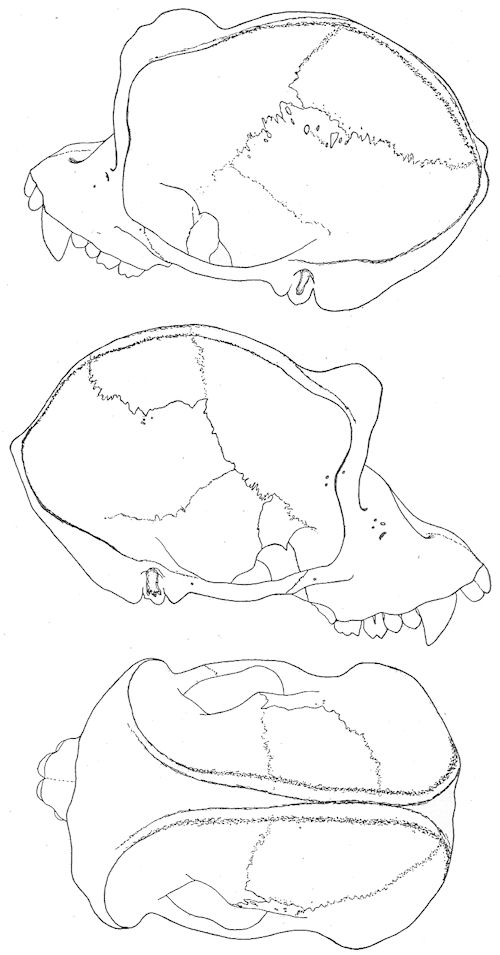

Fig. 1. Division of the Right Parietal in an Orang

(Ranke, Abh. d. k. bayer. Akad. d. Wiss., II cl., XX Bd., ii Abth.).

The divisions which

I am about to describe

occur, one in

each parietal, in the

skull of a nine-year-old

male chimpanzee,

which was captured,

when young, in West

Africa. Later on he

was one of the attractions

of the Barnum

and Bailey Circus,

and was familiarly

known as Chico. The

chimpanzee died in 1894, since when his skin and bones have

been preserved in the American Museum of Natural History,

New York City. Prof. J. A. Allen, the curator of the Zoölogical

Department of the Museum, has kindly given me permission to

describe the skeletal parts for publication.

[3]

The most interesting part of Chico is unquestionably the skull.

The divisions of the parietal bones which the specimen presents

are not only the first complete divisions of the parietal observed

in a chimpanzee, but are also unique in character, no divisions of

the same nature having been observed before, either in man,

in apes, or in monkeys. The position and extent of the divisions

in this skull will throw considerable light on the question of the

[Pg 283]

aberrant, complete divisions of the parietal bone, by which term

may be designated divisions differing from the typical horizontal

ones.

The skull under consideration shows in general a good development

and an almost perfect symmetry. The capacity of the

brain cavity, measured according to Flower's method, is 390 c.c.

The masculine features of this skull, and particularly the

temporal ridges, are not quite as marked as those of another

skull of an adolescent male chimpanzee in the Museum. The

temporal ridges are slightly prominent, and in their middle third,

over part of the frontal and the parietal bones, not more pronounced

than in some human crania. They are, however, situated

very high. Their upper lines or boundaries touch each other

over a part of the sagittal suture, a little back of the bregma;

while the lower lines approach to within 6 mm. of the sagittal

suture. The supraorbital ridges are not very massive, although

prominent to such a degree that, when the skull rests on

the occipital condyles and on the teeth, the plane of the orbits is

almost vertical. The sagittal crest is insignificant; the occipital

crest is high, but not very massive. The zygomatic arches are less

strong than they are in an average white male; and the mastoids

are small, even smaller than in an average adult white female.

The second dentition is incomplete; the third molars have not

reached the level of the opening of their sockets. The condition

of the sutures, so far as their patency is concerned, does not

bear the same relation to the stage of dentition as it does in

man: all the sutures of this skull are more or less obliterated.

There are no signs on any part of the skull that point to the

closure of any of the sutures as premature. In detail, the condition

of the sutures is as follows: The spheno-maxillary articulation

is completely closed, but still plainly traceable. Of the

various facial sutures, only remnants are open; the suture in the

zygomatic arch, however, is almost fully patent on both sides.

The spheno-frontal articulation is completely obliterated on the

left, but traces of it remain on the right side. The left temporo-sphenoidal

and squamo-frontal sutures (the squama of the temporal

articulates with the frontal bone) are, with the exception of

the basal part of the former, which remains open, quite obliterated,

but on the right side both are open. The temporo-parietal

[Pg 284]

sutures, with the exception of 8 mm. of the anterior end of

the suture on the right side, are both entirely closed and hardly

traceable. The coronal suture is partly open on the left, and

wholly open on the right, up to a point a little below the middle

of the anterior border of the parietal bone. At this point on each

side, the lower portion of the coronal suture bends backward

and continues as the anomalous suture; the upper portion of

the coronal, particularly on the right, is completely obliterated,

though still traceable. There are no signs left of the sagittal

and lambdoid sutures, and only the basal portions of the temporo-occipital

articulation remain. The palatine sutures, also, are

entirely obliterated.

The skull shows no important anomalies besides the division

of the parietals.

The divisions of the parietal bones begin on the left 32 mm.,

on the right 28 mm. (measured with a tape), above the point of

junction of the coronal and temporo-parietal sutures. From the

point where the anomalous sutures leave the coronal suture, to

the bregma, the distance on the left is 44 mm., on the right

42 mm. The excess of size of the left over the right parietal

bone along the coronal suture (6 mm.) compensates the greater

height of that portion of the right temporal squama which articulates

with the frontal bone. Measured across their middle from

the temporo-parietal suture, the two parietals appear to be almost

of equal size (left 82 mm., right 80 mm.). In an antero-posterior

direction, from the beginning of the division to the middle of the

parietal portion of the occipital crest, both bones measure the

same, namely 75 mm.

The division in the left parietal begins at a V-shaped cleft,

which is filled with a process of the frontal bone. There are

slightly distinct markings on the bone and a number of insular

ossicles, which make it probable that the cleft had been originally

much greater and was largely filled by a Wormian or, rather, a

fontanel bone, the lower border of which has subsequently united

with the parietal.

For 30 mm. from its beginning the abnormal suture proceeds

directly backward, and to this extent shows but little obliteration.

The original cleft has, it seems, extended up to this point.

From here the suture takes a slight bend upwards, and proceeds

[Pg 285]

[Pg 286]

almost directly upwards and backwards, becoming gradually obliterated,

until it disappears at the temporal ridge, 16 mm. from

the median line. Originally the suture must have terminated on

the posterior border of the parietal bone, not far from the

lambda. The whole suture shows fairly good serration. The

coronal suture on this side, below the division, shows serration

about equal to that of the abnormal suture; the obliterated portion

above this was, so far as can be seen, more simple.

Figs. 2–4. Skull of an Adolescent Male Chimpanzee.

On the right side the division of the parietal may also have

begun with a cleft in the anterior border of the bone, but, owing

to the advanced state of obliteration of the upper portion of the

coronal suture on this side, the existence of the cleft cannot be

fully ascertained. Here also the abnormal suture, at first wholly

open, runs for the first 26 mm. directly backwards; at this point

the suture, still quite patent, takes a turn somewhat sharper

than that on the left, and proceeds for 16 mm. backwards and upwards;

here it takes a second turn, and proceeds almost directly

upwards towards the sagittal suture. This last portion of the

abnormal suture is considerably obliterated, and on and beyond

the temporal ridge is scarcely traceable. The point at which the

division has reached the sagittal suture is situated a little behind

the middle of the latter. The abnormal as well as the open

part of the coronal suture on this side shows a simpler serration

than the corresponding sutures on the left side.

In this specimen there is on neither side any encroachment of

the lower portion of the parietal bone upon the frontal, such as

Ranke lays stress on in the case of his orangs. A second skull of

an adolescent male chimpanzee, in the Museum of Natural History,

has a decided bend in the coronal suture, not unlike that

which Ranke describes, and which, as he thinks, generally indicates

an old parietal division; but in this case the bend is situated

between the inferior and superior boundaries of the prominent

temporal ridge, and apparently owes its origin to the latter (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

The main interest in the case just described centres in the

direction of the abnormal sutures, and in the clearness with which

the two divisions appear as equivalent and of the same origin,

although one divides the parietal completely, while the other is

restricted to one of its angles.

[Pg 287]

As to the course of the abnormal suture in the parietal bone,

in all the cases thus far reported, the division runs in a horizontal

direction (cases of Tarin, Soemmering, Gruber, Hyrtl, Welcker,

Turner, Putnam, Dorsey, Ranke, and others); or it runs obliquely

from or near the middle of the lambdoid suture to some

part of the temporo-parietal suture, the sphenoidal angle, or the

lower portion of the coronal suture (cases of Curnow, Ekmark,

Gruber, Hyrtl, Lucae, Welcker, Putnam, Traquair, Ranke); in

a case of Simia silenus described by Gruber and in an Egyptian

cranium described by Smith, the divisions run to the lambda

and begin respectively slightly above the pterion and at it. In

Boyd's and in two of Hyrtl's cases, the abnormal suture begins

at or below the bregma on the coronal margin of the parietal

bone, and ends at or near its mastoid angle; finally, in Blumenbach's

(cited by Welcker), Bianchi's, Fusari's, and Coraini's cases

(those of Coraini include two monkeys) the division is vertical,

passing between the temporo-parietal and sagittal sutures. The

left division in our chimpanzee approaches those in Gruber's

Simia silenus and Smith's cases; but it originates much higher

anteriorly, and terminates slightly below the lambda on the occipital

border of the parietal. The division in the right parietal of

the chimpanzee, beginning slightly below the middle of the anterior

border of the bone, and ending slightly back of the middle

of its sagittal border, has no analogy among the cases previously

described.

The difference in extent and terminations of the two abnormal

sutures in the chimpanzee is of particular interest in connection

with the problem of the significance and origin of those divisions

of the parietal bone that involve more or less only one of its

angles.

Since the observations of Toldt,

[4] and more recently of Ranke,

[5]

on the development of the parietal bone in the human embryo, it

appears, though it cannot as yet be said whether the fact is or is

not general, that the bone originates from two centres of ossification.

These centres appear in most cases one directly above the

other, but, as Ranke himself shows,

[6] and as can hardly be otherwise,

these primitive components of the parietal do not always

[Pg 288]

show the same relations in size or position. The centres blend

together, ordinarily, at the end of the third or during the first

half of the fourth month of fœtal life. On this account, the

typical, complete, horizontal division of the human parietal bone,

when met with at any time after the fourth month of fœtal life,

is generally interpreted to-day as a retardation of the union, or a

persistence of separation, of the two original segments of the

bone. Opinion, however, is still unsettled as to the significance

of the more atypical, oblique divisions of the parietal, particularly

of those where the separation is limited to one angle. Up to the

recent contribution on the subject by Ranke, the weight of opinion

on the point, although rather briefly expressed, seems to have been

in favor of attributing to these smaller, oblique divisions, the

same significance as was given to the more typical, horizontal

ones. Gruber,

[7] in reporting a new case of a bilateral oblique

suture in the parietal bone, calls the separated mastoid angles

"the secondary posterior parietals." Hyrtl and Welcker advance

no definite theories on this point, though the latter expresses an

opinion

[8] that in both the horizontal division and the separation

of the mastoid angle of the parietal bone the development of the

condition may be identical. In 1883 Prof. F. W. Putnam, in

describing one of his Tennessee skulls with an abnormal oblique

suture in each parietal,

[9] referred the development of the separated

mastoid angle on the right side, as well as the larger oblique

inferior portion of the parietal on the left side, to a "separate

centre" of ossification. Ranke

[10] opposes both Gruber's and

Putnam's opinion, and presents instead a theory somewhat vague

and not satisfactorily demonstrated, by which he accounts for

the origin of oblique sutures from partial horizontal sutures in

the parietal bone through "half-pathological processes." In his

words, "the oblique parietal suture is allied to the half-pathological

conditions of the skull; it is wholly unjustifiable to

speak, as W. Gruber has done, of a separate Parietale secundarium

posterius, severed by the suture, as of a typical, in a certain sense

normal, formation. The oblique parietal suture is nothing more

[Pg 289]

than an incomplete (posterior), true, i. e., typical, parietal suture

with a sagittal course, modified by certain half-pathological conditions."

These half-pathological conditions are produced, the

author explains on the preceding page, "durch Einknickung der

nach Herrn G. H. Meyer 'plastisch' aufwärts gebogenen hinteren

Scheitelbeinränder."

This opinion of Ranke calls for a few words about the incomplete

horizontal parietal sutures. These sutures are apparently

very rare in human adults, only five instances being on record

(4 Ranke's, 1 Turner's). They are more frequent in orangs

(Ranke), and quite common (as Ranke shows, and as I found

independently before Ranke's publication of his observations)

in the human embryos near term and in new-born or very young

infants. In the human family, these partial divisions of the

parietal generally begin in the posterior part, and run sagittally

to the posterior border of the bone, ending in this border at or

near its middle. In orangs the incomplete horizontal divisions

seem to begin, as a rule, in the anterior part, and end at or

near the middle of the anterior border of the parietal. The

length of these divisions varies from a few millimetres to several

centimetres, and they even reach up to the centre of the parietal

bone.

[11] These divisions are, without doubt, the remains of the

original anterior and posterior clefts, or, if we go a step further,

of the original intervening antero-posterior space between the

original inferior and superior segments of the parietal. From

the very first contact of the growing centres, the median extremity

of these clefts is bounded both below and above by a

mass of bone; and when the anterior or posterior border of the

parietal comes finally in contact with the frontal or occipital

bone, the anterior and posterior sagittal clefts, if they still exist,

lie between two well-developed, firm portions of the bone. Under

these circumstances it is quite impossible to imagine any

disturbance, mechanical or pathological, that could affect solely

or mainly the median portion of the cleft, and cause a deflection

downward in this portion of the division, or cause its extension

to the inferior border or even the anterior-inferior angle of the

parietal.

There are only two factors that can possibly affect and modify

[Pg 290]

the course of the incomplete parietal suture, and both of these

would show their influence mainly or entirely on the distal

portion of the same. These two factors are, first, an abnormal

development, either defective or excessive, of one of the original

parietal segments; and, secondly, influences that would interfere

with the freedom of full growth of the anterior or posterior

border of the parietal.

In the first case, as can easily be imagined or even artificially

demonstrated, there would be possible only a lower or higher

situation or an obliquity affecting mostly the marginal portion of

the division. The results would be low or high sagittal sutures,

and curved or oblique sutures diverging from the parietal eminence,—effects

entirely different from the actually observed

oblique sutures that sever the lower portion of the parietal, or its

mastoid angle.

Influences interfering with the free development of the anterior

or posterior border of the parietal bone could only deflect upwards

or downwards the marginal end of an incomplete parietal

suture, or, at most, in a case of a short suture, render it oblique

or curved in its entirety. No pathological condition, unless it were

accompanied by a fracture, could extend even a deflected antero-posterior

incomplete division to any of the borders of the bone.

There are, it seems to me, only three possible ways in which an

oblique suture, extending between any two borders of the parietal

bone, can be produced.

In the first case the oblique suture, or rather a suture-like formation,

may be the effect of an early fracture. A fracture produced

in adult life is generally recognizable as such; but a

fracture dating from earlier stages of life, produced before the

growth of the bone has ceased, may, if not entirely obliterated,

present more or less the characteristics of a suture. I have seen

several skulls where a division in the parietal bone or the temporal

squama presented at the same time features of a fracture

and suture; in one or two of these cases so much so, that it was

and still is impossible for me to decide exactly which of the two

conditions I had before me. Gruber describes one such case

[12]

as an instance of an oblique parietal suture, while Hyrtl and

Ranke both consider this case as one with an acquired division.

[Pg 291]

To differentiate a congenital real oblique suture from a division

which is the result of a fracture, we must be guided largely by

the situation, form, and serration of the division, and the condition

of the surrounding bones, especially that of the opposite

parietal. A straight course, ending with one extremity in or

near the middle of the anterior or posterior border of the parietal,

a complex serration, no continuity of the division on the neighboring

bones, and particularly a co-existence of an allied or

similar division on the opposite parietal,—all favor the conclusion

that the division under consideration is a real congenital

suture, and not the result of a fracture.

In the second case there are reasons for believing that an

oblique suture of the parietal bone can originate in the same

way as the horizontal one, namely, through a persistence of the

original separation between the two centres from which the bone

is developed, and a co-existent difference in the relative position

or the relative growth of the two centres. It is in this connection

that the above-described division in the parietals of the chimpanzee

will prove of value.

The occasional persistence of the separation between the two

original segments of the parietal bone is sufficiently demonstrated

by the presence of the complete horizontal parietal suture. Differences

in the relative position of these segments can be observed

in a limited degree in Ranke's illustrations of embryos,

before referred to; it can be deduced from such cases as the two

of Hyrtl,

[13] in which the division of the parietal was directed from

the upper portion of the anterior to the lower portion of the posterior

border of the bone. The most pronounced change in the

position of these centres may be witnessed in cases where the

parietal bone shows a perfect vertical instead of a horizontal suture.

Such cases have been referred to before, and I presented

at the meeting of the Association of American Anatomists, in

1899, several such examples, found by me in skulls of monkeys

in Professor Huntington's anatomical collection in the Medical

Department of Columbia University. One of these specimens is

shown in the accompanying illustration (Fig. 5).

A difference in the relative growth of the two centres of the

[Pg 292]

parietal bone is well shown in the difference of size between the

inferior and superior portions of the parietal in cases of the complete

horizontal suture in the same. In the majority of such

cases on record the superior portion is larger, particularly anteriorly,

than the inferior; so

much so, that that condition

seems to be the typical one.

The difference in the size of

the two portions of the parietal,

and in their relative anterior

and posterior height, is most

pronounced in one of Gruber's

cases,

[14] where the "parietal suture"

begins only 10 mm. above

the pterion, and ends 40 mm.

above the asterion. In Dorsey's

case

[15] the lower portion

of the divided parietal is 12

mm. higher than the upper.

The same condition as is found

in Gruber's case, here mentioned,

exists in the almost

identical left division of the second case of Putnam, of

which I have a photograph in my hands. A somewhat similar

excess of the posterior over the anterior part of the lower severed

portion of the parietal can also be seen in the illustrations of the

cases of Tarin, Lucae, and Turner (Admiralty Islands skull). In

Calori's interesting case

[16] there is a decided excess of the lower

portion of the divided parietal in its posterior portion on the left

and in its anterior portion on the right side.

Fig. 5. Macacus rhesus (Medical Department,

Columbia University), showing a Complete Division of the Right Parietal Bone in

a Vertical Direction.

In case the upper segment was not vertically above the lower

one, but in a position a little more forward or backward of it;

and, furthermore, if the relative growth of the two segments

differed, and their separation remained permanent,—the separation

of any portion of the parietal bone in almost any form and

to almost any extent might result. Such coincidence of anomalous

[Pg 293]

conditions, although necessarily rare, cannot, from what

we know on the subject in parietal and other bones, be declared

improbable. All cases where oblique suture on one side

co-exists with more or less horizontal suture on the other

side in the parietal bone, as in the second of Putnam's cases,

would of course point directly to a similar origin of the anomaly

on both sides of the cranium. That such cases have not been

more frequently observed is largely due, I think, to the rarity of

bilateral parietal divisions.

A third mode of development of the oblique suture in the

parietal bone suggests itself where the severed portion of the

bone is small, and that is the possible existence of a supernumerary,

third centre of ossification. I am by no means ready

to defend this theory, yet there are cases in which it would afford

the easiest explanation. I have a Peruvian skull at hand, in

which there is a bilateral, quite symmetrical quadrangular separate

piece of bone, encroaching on the mastoid process of the parietal.

The surface of the left parietal bone in this skull measures across

its middle in antero-posterior direction 120 mm., in infero-superior

direction 130 mm.; similar measures of the right parietal are respectively

117 and 130 mm. The separate bone on the left

measures across its middle in

antero-posterior direction 20

mm., in infero-superior

direction 12 to 21 mm.; the

same portion on the right

measures respectively 25 and

11 to 15 mm. Both pieces are

joined to the parietal bone by

a squamous suture (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 (99/3550). Quadrilateral Fontanel Bones

in a Peruvian Male Skull, encroaching upon the

Mastoid Angle of the Parietals.

It is apparent that the separate

pieces of bone in this

case are too small to be easily

taken for representatives of

one of the regular centres of

ossification of the parietal

bone; but the same pieces are somewhat too large, and

especially too singularly outlined and joined to the parietal, to be

without difficulty diagnosed as simple Wormian or fontanel

[Pg 294]

bones. One of Ranke's cases,

[17] though the separation of the

mastoid angle is oblong instead of quadrangular, as in the Peruvian

skull, seems to me to present a similar difficulty in properly

diagnosing the nature of the severed portion. This group of

cases needs further observation, particularly on the bones of infants

and embryos. I have two monkey skulls at hand which

actually show a multiplicity of the original segments of the parietal.

These specimens will be described in a future publication.

So much as to the formation of the oblique sutures in the parietal.

It should not be forgotten that such sutures can be simulated

by those which divide true Wormian or fontanel bones from

the parietal. The distinction between the real oblique parietal

and these extra-parietal sutures must depend largely on the extent

of the division and form of the separate piece of bone.

We may now return to the skull of our chimpanzee. In considering

the nature of the divisions in the parietal bones of this

skull, we can at once and absolutely discard the idea of the

divisions being due to fractures, or being boundaries of

Wormian or fontanel bones, and thus really extra-parietal in

their nature. There is nothing about the sutures, or the divided

pieces, or the neighboring bones, that would even suggest such

an explanation; and in our records on Wormian and fontanel

bones we find no analogies either in man, or apes, or lower animals,

to the conditions here observed. The necessary conclusion

from this can only be that we have before us two examples of

real parietal division.

The division on the left side, had it existed alone, would be

readily acceptable as an instance of the "parietal suture." The

anterior extremity and more than the anterior third of the course

of the division correspond exactly to the same features of a

typical, horizontal "parietal suture;" while the elevation of the

posterior extremity of the division, though unusual, can readily

be explained as due to an excess in growth of the inferior original

centre of the bone, which may, in addition, have been situated

slightly posterior to the upper centre.

The division in the right parietal of the chimpanzee begins at

its anterior end, and runs for the first third of its course in the

same way as that on the left side; its posterior end, however,

[Pg 295]

does not reach the lambdoid, but turns up and ends in the sagittal

border. Should this formation have existed alone, I should

be inclined to consider it either as the result of an accessory

centre of the parietal, or, possibly, as a persistence of the anterior

portion of the divided superior centre of the bone, the posterior

portion of the same being united with the lower segment of the

parietal in the usual way. With the division of the left parietal

in the same skull before me, everything points to a similar origin

of the division on both sides, and to the right as well as the left

division being a true "parietal suture," deflected less on the

left and more on the right side by a disproportion in growth of

the two original, regular segments of each of the bones.

The disproportion of growth of the two original segments of

the parietal bone will, I believe, be found more common as attention

is directed to this subject. It can be well explained,

though there may at times be other factors present, by a difference

in the blood-supply to the two centres. This of course may

occur not only in different skulls, but also on the two sides of

the same cranium.

Footnotes

[1] Die überzähligen Hautknochen des menschlichen Schädeldachs, Abh. d. k. bayer. Akad.

d. Wiss., II Cl., XX Bd., II Abth., pp. 36 et seq., Fig. 17.

[2] L. c., p. 41. Among 3000 Bavarian crania, Ranke found but one with complete and three

with incomplete parietal sutures; basing his conclusion on this observation, he says, "Bei den

Orangutanschädeln ist die Häufigkeit der Scheitelbeinnäthe circa 40 mal grösser als bei

dem erwachsenen Menschen."

[3] Since finding the abnormal sutures on this skull, I have been able to present the same at a

meeting of the Association of American Anatomists (1899) and before the Ethnological Society

of New York City (1900).

[4] Toldt, C., in Maska's Hdb. d. gerichtl. Med., 1882, v. III, p. 515; the same in his U.

d. Entwick. d. Scheitelbeins d. Menschen, Zeitschr. f. Heilkunde, 1883, v. IV, pp. 83–86.

[5] L. c., pp. 324–330.

[6] L. c., pp. 327–330, Figs. 29–32.

[7] Gruber, W., Beobacht. a. d. menschl. u. vergl. Anat., Berlin, 1879, II Heft, pp. 12–15.

[8] Welcker, H., Untersuch. ü. d. Wachsthum u. Bau d. menschl. Schädels, Leipzig, 1862,

p. 109.

[9] Putnam, F. W., Abnormal Human Skulls from Stone Graves in Tennessee (Proc. A.

A. A. S., XXXII, 1884, p. 391).

[10] L. c., p. 309.

[11] Ranke's Fig. 25, p. 318.

[12] Virchow's Archiv, 1870, v. 50, p. 113.

[13] Hyrtl, J., Die doppelten Schläfenlinien d. Menschenschädel, etc. (Denkschr. d. math. naturw.

Classe d. k. Akad. d. Wiss. zu Wien, 1871, v. XXXII, pp. 39–50).

[14] Gruber, W., Beobacht. a. d. menschl. u. vergl. Anat., Berlin, 1879, II Heft, p. 15.

[15] Dorsey, G. A., Chicago Med. Recorder, v. XII, Feb., 1897.

[16] Calori, Luigi, Sut. soprannum. d. Cranio Umano (Mem. d. Accad. d. Sc. d. Ist. d. Bologna,

1867, pp. 327 et seq., Fig. 4).

[17] L. c., p. 303, Fig. 13.

PUBLICATIONS

OF THE

American Museum of Natural History

The publications of the American Museum of Natural History consist of

the 'Bulletin,' in octavo, of which one volume, consisting of about 400 pages,

and about 25 plates, with numerous text figures, is published annually; and

the 'Memoirs,' in quarto, published in parts at irregular intervals.

The matter in the 'Bulletin' consists of about twenty-four articles per

volume, which relate about equally to Geology, Palæontology, Mammalogy,

Ornithology, Entomology, and (in the recent volumes) Anthropology.

Each Part of the 'Memoirs,' forms a separate and complete monograph,

with numerous plates.

MEMOIRS.

Vol. I (not yet completed).

Part I.—Republication of Descriptions of Lower Carboniferous Crinoidea

from the Hall Collection now in the American Museum of Natural History,

with Illustrations of the Original Type Specimens not heretofore

Figured. By R. P. Whitfield. Pp. 1–37, pll. i-iii. September 15, 1893.

Price, $2.00.

Part II.—Republication of Descriptions of Fossils from the Hall Collection in

the American Museum of Natural History, from the report of Progress for

1861 of the Geological Survey of Wisconsin, by James Hall, with Illustrations

from the Original Type Specimens not heretofore Figured. By

R. P. Whitfield. Pp. 39–74, pll. iv-xii. August 10, 1895. Price, $2.00.

Part III.—The Extinct Rhinoceroses. By Henry Fairfield Osborn. Part I.

Pp. 75–164, pll. xiia-xx. April 22, 1898. Price, $4.20.

Part IV.—A complete Mosasaur Skeleton. By Henry Fairfield Osborn. Pp.

165–188, pll. xxi-xxiii, with 15 text figures. October 25, 1899.

Part V.—A Skeleton of Diplodocus. By Henry Fairfield Osborn. Pp.

189–214, pll. xxiv-xxviii, with 15 text figures. October 25, 1899. Price

of Parts IV and V, issued under one cover, $2.00.

Vol. II. Anthropology (not yet completed).

The Jesup North Pacific Expedition.

Part I.—Facial Paintings of the Indians of Northern British Columbia. By

Franz Boas. Pp. 1–24, pll. i-vi. June 16, 1898. Price, $2.00.

Part II.—The Mythology of the Bella Coola Indians. By Franz Boas. Pp.

25–127, pll. vii-xii. November, 1898. Price, $2.00.

Part III.—The Archæology of Lytton, British Columbia. By Harlan I.

Smith. Pp. 129–161, pl. xiii, with 117 text figures. May, 1899. Price, $2.00.

Part IV.—The Thompson Indians of British Columbia. By James Teit.

Edited by Franz Boas. Pp. 163–392, pll. xiv-xx, with 198 text figures.

April, 1900. Price, $5.00.

Part V.—Basketry Designs of the Salish Indians. By Livingstone Farrand.

Pp. 393–399, pll. xxi-xxiii, with 15 text figures. April, 1900. Price, 75 cts.

Vol. III. Anthropology (not yet completed).

Part I.—Symbolism of the Huichol Indians. By Carl Lumholtz. Pp. 1–228,

pll. i-iv, with 291 text figures. May, 1900. Price, $5.00.

BULLETIN.

| Volume | I, 1881–86 | Price, $5.50 |

| " | II, 1887–90 | " 4.75 |

| " | III, 1890–91 | " 4.00 |

| " | IV, 1892 | " 4.00 |

| " | V, 1893 | " 4.00 |

| " | VI, 1894 | " 4.00 |

| " | VII, 1895 | " 4.00 |

| " | VIII, 1896 | " 4.00 |

| " | IX, 1897 | " 4.75 |

| " | X, 1898 | " 4.75 |

| " | XI, Part I, 1898 | " 1.25 |

| " | II, 1899 | " 2.00 |

| " | XII, 1899 | " 4.00 |

For sale by G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London;

J. B. Baillière et Fils, Paris; R. Friedländer & Sohn, Berlin;

and at the Museum.

Transcriber's Note

- Footnotes have been moved to the end of the article.

Featured Books

Wieland; Or, The Transformation: An American Tale

Charles Brockden Brown

not disapprove of the manner in which appearances are solved, but that the solution will b...

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

L. Frank Baum

ne of another strange adventure.There were many requests from my little correspondents for "more abo...

ABC of Fox Hunting

Sir John Dean Paul

turned my Lord over.U. was the Upland, where we viewed the Fox in.V. was the very last field—just ...

Maiwa's Revenge; Or, The War of the Little Hand

H. Rider Haggard

about two thousand acres of shooting round the place he had bought inYorkshire, over a hundred of w...

Rupert of Hentzau: From The Memoirs of Fritz Von Tarlenheim

Anthony Hope

R OUR LOVE AND HER HONOR CHAPTER XX. THE DECISION OF HEAVEN CHAPTER XXI. T...

The Head of Kay's

P. G. Wodehouse

I — MAINLY ABOUT FENN "When we get licked tomorrow by half-a-dozen wickets," sai...

The Devil's Dictionary

Ambrose Bierce

ime, too, some of the enterprising humorists of the country had helped themselves to such parts...

Stories by English Authors: The Orient (Selected by Scribners)

ll complete. But, to-day, I greatly fear that my King is dead, and if I want a crown I mus...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "A Bilateral Division of the Parietal Bone in a Chimpanzee; with a Special Reference to the Oblique Sutures in the Parietal" :