The Project Gutenberg eBook of In the Court of King Arthur

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: In the Court of King Arthur

Author: Samuel E. Lowe

Release date: September 1, 2004 [eBook #6582]

Most recently updated: March 20, 2013

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Alan Millar and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN THE COURT OF KING ARTHUR ***

|

In The Court of King Arthur

by Samuel E. Lowe

Illustrations by Neil O'Keeffe

1918

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter

I. Allan Finds A Champion

II. Allan Goes Forth

III. A Combat

IV. Allan Meets The Knights

V. Merlin's Message

VI. Yosalinde

VII. The Tournament

VIII. Sir Tristram's Prowess

IX. The Kitchen Boy

X. Pentecost

XI. Allan Meets A Stranger

XII. The Stranger And Sir Launcelot

XIII. The Party Divides

XIV. King Mark's Foul Plan

XV. The Weasel's Nest

XVI. To The Rescue

XVII. In King Mark's Castle

XVIII. The Kitchen Boy Again

XIX. On Adventure's Way

XX. Gareth Battles Sir Brian

XXI. Knight Of The Red Lawns

XXII. Sir Galahad

XXIII. The Beginning Of The Quest

XXIV. In Normandy

XXV. Sir Galahad Offers Help

XXVI. Lady Jeanne's Story

XXVII. Sir Launcelot Arrives

XXVIII. A Rescue

XXIX. Facing The East

XXX. Homeward

XXXI. The Beggar And The Grail

|

WHO WAS KING ARTHUR?

King Arthur, who held sway in Camelot with his Knights of the

Round Table, was supposedly a king of Britain hundreds of years

ago. Most of the stories about him are probably not historically

true, but there was perhaps a real king named Arthur, or with a

name very much like Arthur, who ruled somewhere in the island of

Britain about the sixth century.

Among the romantic spires and towers of Camelot, King Arthur

held court with his queen, Guinevere. According to tradition, he

received mortal wounds in battling with the invading Saxons, and

was carried magically to fairyland to be brought back to health and

life. Excalibur was the name of King Arthur's sword--in fact, it

was the name of two of his swords. One of these tremendous weapons

Arthur pulled from the stone in which it was imbedded, after all

other knights had failed. This showed that Arthur was the proper

king. The other Excalibur was given to Arthur by the Lady of the

Lake--she reached her hand above the water, as told in the story,

and gave the sword to the king. When Arthur was dying, he sent one

of his Knights of the Round Table, Sir Bedivere, to throw the sword

back into the lake from which he had received it.

The Knights of the Round Table were so called because they

customarily sat about a huge marble table, circular in shape. Some

say that thirteen knights could sit around that table; others say

that as many as a hundred and fifty could find places there. There

sat Sir Galahad, who would one day see the Holy Grail. Sir Gawain

was there, nephew of King Arthur. Sir Percivale, too, was to see

the Holy Grail. Sir Lancelot--Lancelot of the Lake, who was raised

by that same Lady of the Lake who gave Arthur his sword--was the

most famous of the Knights of the Round Table. He loved Queen

Guinevere.

All the knights were sworn to uphold the laws of chivalry--to go

to the aid of anyone in distress, to protect women and children, to

fight honorably, to be pious and loyal to their king.

|

CHAPTER ONE

Allan Finds A Champion

"I cannot carry your message, Sir Knight."

Quiet-spoken was the lad, though his heart held a moment's fear

as, scowling and menacing, the knight who sat so easily the large

horse, flamed fury at his refusal.

"And why can you not? It is no idle play, boy, to flaunt Sir

Pellimore. Brave knights have found the truth of this at bitter

cost."

"Nevertheless, Sir Knight, you must needs find another message

bearer. I am page to Sir Percival and he would deem it no service

to him should I bear a strange knights message."

"Then, by my faith, you shall learn your lesson. Since you are

but a youth it would prove but poor sport to thrust my sword

through your worthless body. Yet shall I find Sir Percival and make

him pay for the boorishness of his page. In the meantime, take you

this."

With a sweep the speaker brought the flat side of his sword

down. But, if perchance, he thought that the boy would await the

blow he found surprise for that worthy skillfully evaded the

weapon's downward thrust.

Now then was Sir Pellimore doubly wroth.

"Od's zounds, and you need a trouncing. And so shall I give it

you, else my dignity would not hold its place." Suiting action to

word the knight reared his horse, prepared to bring the boy to

earth.

It might hare gone ill with Allan but for the appearance at the

turn of the road of another figure--also on horseback. The new

knight perceiving trouble, rode forward.

"What do we see here?" he questioned. "Sir Knight, whose name I

do not know, it seems to me that you are in poor business to

quarrel with so youthful a foe. What say you?"

"As to with whom I quarrel is no concern of anyone but myself. I

can, however, to suit the purpose, change my foe. Such trouncing as

I wish to give this lad I can easily give to you, Sir Knight, and

you wish it?"

"You can do no more than try. It may not be so easy as your

boasting would seeming indicate. Lad," and the newcomer turned to

the boy, "why does this arrogant knight wish you harm?"

"He would have me carry a message, a challenge to Sir Kay, and

that I cannot do, for even now I bear a message from Sir Percival,

whose page I am but yesterday become. And I must hold true to my

own lord and liege."

"True words and well spoken. And so for you, Sir Knight of the

arrogant tongue, I hope your weapon speaks equally well. Prepare

you, sir."

Sir Pellimore laughed loudly and disdainfully.

"I call this great fortune which brings me battle with you, sir,

who are unknown but who I hope, none the less, are a true and brave

knight."

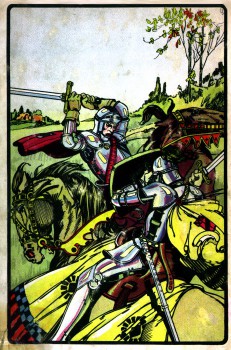

The next second the two horses crashed together. Sir Pellimore

soon proved his skill. The Unknown, equally at ease, contented

himself with meeting onslaught after onslaught, parrying clever

thrusts and wicked blows. So they battled for many an hour.

Allan, the boy, with eyes glistening, waited to see the outcome

of the brave fight. The Unknown, his champion, perhaps would need

his aid through some dire misfortune and he was prepared.

Now the Unknown changed his method from one of defense to one of

offense. But Sir Pellimore was none the less skillful. The third

charge of his foe he met so skillfully that both horses crashed to

the ground. On foot, the two men then fought--well and long. Until,

through inadvertence, the Unknown's foot slipped and the next

moment found his shield splintered and sword broken.

"Now then, by my guardian saint, you are truly vanquished," Sir

Pellimore exclaimed exultantly. "Say you so?"

But the Unknown had already hurled himself, weaponless, upon the

seeming victor and seizing him about the waist with mighty

strength, hurled him to the ground. And even as the fallen knight,

much shaken, prepared to arise, lo, Merlin the Wizard appeared and

cast him into a deep sleep.

"Sire," the Wizard declared, "do you indeed run many dangers

that thy station should not warrant. And yet, I know not whether

we, your loyal subjects, would have it otherwise."

Now Allan, the boy, realized he was in the presence of the great

King. He threw himself upon his knees.

"Rise lad," said King Arthur kindly. "Sir Percival is indeed

fortunate to have a page, who while so young, yet is so loyal. So

shall we see you again. Kind Merlin," and the King turned to the

Wizard, "awaken you this sleeping knight whose only sin seems an

undue amount of surliness and arrogance, which his bravery and

strength more than offset."

Now Sir Pellimore rubbed his eyes. "Where am I?" he muttered

drowsily. Then as realization came, he sprang to his feet.

"Know you then, Sir Pellimore," said Merlin, "he with whom you

fought is none other than Arthur, the King."

The knight stood motionless, dumbfounded. But only for a

moment.

"If so, then am I prepared for such punishment as may come. But

be it what it may, I can say this, that none with whom I fought has

had more skill or has shown greater bravery and chivalry. And more

than that none can say."

And the knight bowed low his head, humbly and yet with a touch

of pride.

"Thou art a brave knight, Sir Pellimore. And to us it seems,

that aside from a hasty temper, thou couldst well honor us by

joining the Knights of the Round Table. What saith thou?"

"That shall I gladly do. And here and now I pledge my loyalty to

none other than Arthur, King of Britain, and to my fellow knights.

And as for you, boy, I say it now--that my harsh tongue and temper

ill became the true knight I claim to be."

"Brave words, Sir Pellimore," said the King. "So let us back to

the castle. We see that Merlin is already ill at ease."

CHAPTER TWO

Allan Goes Forth

So then the four, the good King, Sir Pellimore, Merlin the

Wizard, and Allan, page to Sir Percival, came to the great castle

of Britain's king.

Arthur led them into the great hall in which were placed many

small tables and in the center of them all was one of exceeding

size and round. Here was to be found a place for Sir Pellimore but

though the King searched long, few seats did he find which were not

bespoken. Yet finally he found one which did well for the new

arrival.

"Here then shall you find your place at the Round Table, good

knight," said the King. "And we trust that you will bring renown

and honor to your fellowship, succor to those who are in need and

that always will you show true chivalry. And we doubt not but you

will do all of these."

Sir Pellimore bowed low his head nor did he make reply because

within him surged a great feeling of gratitude.

The King turned away and Merlin followed him to the upraised

dais. So now the two seated themselves and joined in earnest

talk.

At the door, Allan had waited, for he would not depart until His

Majesty had seated himself. A strange gladness was in the boy's

heart, for had not his King fought for him? Here in this court, he

too would find adventure. Sir Percival mayhap, some day, would dub

him knight, should he prove faithful and worthy. What greater glory

could there be than to fight for such a King and with such brave

men?

"But I must be off," he suddenly bethought himself, "else Sir

Percival will not be pleased." And therewith, he made great haste

to depart.

"Aye, sire," Merlin was now speaking, "my dream is indeed

weighted with importance. But by the same taken, it cannot be known

until you call your court together so that it may be heard by

all."

"Then mean you, kind Merlin, that we must call not only those of

the Round Table but all other knights and even pages and

squires?"

"Even so, sire. And yet, since Whitsunday is but a few days

away, that should be no hard matter. For the knights of your court,

except Sir Launcelot and Sir Gawaine are here, prepared for such

tourneys and feasts fit to celebrate that day."

"So then shall it be. Even now our heralds shall announce that

we crave the attendance of all those who pledge loyalty to our

court. For I know well that they must be of no mean import, these

things we shall hear. We pray only that they shall be for our good

fortune."

The Wizard, making no reply, bent low and kissed his King's

hand. Then he departed.

Came now his herald whom the King had summoned.

"See to it that our court assembles this time tomorrow. Make far

and distant outcry so that all who are within ear may hear and so

hurry to our call. And mark you this well. We would hare Sir

Launcelot and our own nephew, Sir Gawaine, present even though they

departed this early morn for Cornwall. See you to it."

Swiftly the herald made for the door to carry out the commands

of his King. But even as he reached it, Arthur called again to

him.

"We have a fancy, good herald, we fain would have you follow.

Ask then Sir Percival to let us have the services of his page who

seems a likely youth and bid this youth go hence after the two

absent knights, Sir Gawaine and Sir Launcelot and give to them our

message, beseeching their return. Tell not the boy it is we who

have asked that he go."

"It shall be done as you will, sire," replied the herald. No

surprise did he show at the strangeness of the King's command for

long had he been in his service and well he knew the King's strange

fancies.

Sir Percival gave ready consent, when found. So when the boy had

returned from the errand forespoken, the herald announced that he

must hasten after the two knights and bid them return.

"And by my faith, lad, you have but little time and you must

speed well. For tomorrow at this time is this conclave called, and

the two knights are already many miles on their journey. Take you

this horse and hasten."

Then, as the eager youth, quick pulsed, made haste to obey, the

herald added in kindly voice: "It would be well could you succeed,

lad. For it is often true that through such missions, newcomers

prove future worthiness for knighthood."

"I thank you greatly for your kindness," replied the boy. "I can

but try to the uttermost. No rest shall I have until I meet with

the two knights."

So now Allan sought out and bespoke his own lord.

"I wish you well, Allan," said Sir Percival. "And say you to my

friends Launcelot and Gawaine should they prove reluctant that they

will favor their comrade, Sir Percival, if they would make haste

and hurry their return. Stop not to pick quarrel nor to heed any

call, urgent though it may seem. Prove my true page and

worthy."

"I shall do my very best, my lord. And, this my first

commission, shall prove successful even though to make it so, I

perish."

Swiftly now rode forth the boyish figure. Well, too, had Arthur

chosen. Came a day when, than Allan, no braver, truer knight there

was. But of that anon.

CHAPTER THREE

A Combat

"Good Launcelot, I trust that good fortune shall be with us and

that our adventures be many and the knights we meet bold and

brave."

"Of that, Gawaine, we need have no fear. For adventure ever

follows where one seeks and often enough overtakes the seeker. Let

us rather hope that we shall find Sir Tristram and Sir Dinadian,

both of Cornwall. For myself I would joust with Sir Tristram than

whom braver and bolder knight does not live."

"And as for me," spoke Gawaine, "my anxiety is to see Mark, the

king of Cornwall, and tell him to his face that I deem him a scurvy

hound since he promised protection to Beatrice of Banisar as she

passed through his lands and yet broke his promise and so holds her

for ransom."

"And there shall I help you, dear Gawaine. For bitterly shall

Mark rue his unknightly act. Shall I even wait for my event with

Sir Tristram until your business is done."

"Aye, and gladly will Sir Tristram wait, I wot, if he deems it

honor to meet with Sir Launcelot du Lake. For no knight there is

who doth not know of your prowess and repute, Sir Tristram least of

all."

"Kind words, Gawaine, for which I thank you. Yet, if I mistake

not, yonder, adventure seems to wait. And we but a little more than

two score miles from our gates."

Ahead of them and barring their way were ten knights. Launcelot

and Gawaine stopped not a moment their pace but rode boldly

forward.

"And wherefor do you, strange Knights, dispute our passage?"

asked Sir Gawaine.

"Safely may you both pass unless you be gentlemen of King

Arthur's court," quote the leader who stepped forward to

answer.

"And what if we be, Sir Knight?" replied Sir Launcelot

mildly.

"And if you be then must you battle to the uttermost. For we owe

loyalty to King Ryence who is enemy of King Arthur. Therefore, are

we his enemies too, and enemies also of all of King Arthur's

subjects. And thus, we flaunt our enmity. We here and now call King

Arthur an upstart and if you be of his court you cannot do aught

else but fight with us."

"Keep you your words," said Sir Gawaine, "until we have ceased

our quarrel. Then if you will you may call Arthur any names.

Prepare you."

Boldly Sir Launcelot and Sir Gawaine charged upon the foe. Nor

did the knights who met them know who these two were, else milder

were their tone. Such was the valor of the two and such their

strength that four men were thrown from their horses in that first

attack and of these two were grievously wounded.

Together and well they fought. Easily did they withstand the men

of King Ryence. Four men were slain by their might, through

wondrous and fearful strokes, and four were sorely wounded. There

lay the four against an oaken tree where they had been placed in a

moment's lull. But two knights were left to oppose Launcelot and

Gawaine but these two were gallant men and worthy, the very best of

all the ten.

So they fought again each with a single foe. Hard pressed were

the two men of King Ryence, yet stubbornly they would not give way.

And as each side gave blow for blow, so each called "for Arthur" or

"for Ryence," whichever the case might be. Many hours they fought

until at last Sir Launcelot by a powerful blow crashed both foe and

foe's horse to the ground.

And as the other would further combat, though exceedingly weak,

Sir Launcelot, upraised lance in hand by a swift stroke smote sword

from out of his weakened grasp.

"Thou art a brave knight, friend. And having fought so well, I

ask no further penance but this, that you do now declare King

Arthur no upstart. I care not for your enmity but I will abide no

slander."

"So must I then declare, since you have proven better man than

I," declared the conquered knight. "And for your leniency I owe you

thanks. Wherefore then to whom am I grateful? I pray your

name?"

"That I shall not tell until I hear your own," replied

Launcelot.

"I am known as Ronald de Lile," the other replied in subdued

tone.

"Truly and well have I heard of you as a brave knight," was the

reply, "and now I know it to be so. I am Sir Launcelot du

Lake."

"Then indeed is honor mine and glory, too. For honor it is to

succumb to Sir Launcelot."

But now both heard the voice of Gawaine. Weak had he grown, but

weaker still his foe. Gawaine had brought the other to earth at

last with swift and mighty blow and such was the force of his

stroke the fallen man could not rise although he made great ado so

to do.

"So must I yield," this knight declared. "Now will I admit

Arthur no upstart, but though I die for it I do declare no greater

king than Ryence ever lived."

"By my faith, your words are but such as any knight must hold of

his own sovereign prince. I cannot take offense at brave words, Sir

Knight. Now, give me your name, for you are strong and worthy."

"I am Marvin, brother of him who fought with your comrade. And

never have we met bolder and greater knights."

"I am Gawaine and he who fought your brother is none other than

Launcelot."

"Then truly have we met no mean foes," replied the other.

Conquered and conquerers now turned to make the wounded as

comfortable as they well could be. After which, our two knights

debated going on their journey or tarrying where they were until

the morn.

"Let us wend our way until we find fit place for food and rest.

There can we tarry." So spoke Launcelot and the other agreed.

Then they took leave of Sir Marvin and Sir Ronald and so on

their way. Not many miles did they go however before they found

suitable place. Late was the hour and weary and much in need of

rest were the two knights. So they slept while, half his journey

covered, Allan sped onward, making fast time because he was but

light of weight and his horse exceeding swift.

CHAPTER FOUR

Allan Meets the Knights

From the first day when Allan began to understand the tales of

chivalry and knightly deeds, he fancied and longed for the day when

he would grow into manhood and by the same token into knighthood.

Then would he go unto King Arthur on some Pentecost and crave the

boon of serving him. Mayhap, too, he would through brave and worthy

deeds gain seat among those of the Round Table. So he would dream,

this youth with eager eyes, and his father, Sir Gaunt, soon came to

know of his son's fancies and was overly proud and pleased with

them. For he himself had, in his days, been a great and worthy

knight, of many adventures and victor of many an onslaught. It

pleased him that son of his would follow in his footsteps.

When Allan was fourteen, Sir Gaunt proceeded to Sir Percival who

was great friend of his and bespoke for his son the place of page.

And so to please Sir Gaunt and for friendship's sake, Sir Percival

gave ready consent. Therewith, he found the youth pleasing to the

eye and of a great willingness to serve.

So must we return to Allan who is now on his way for many an

hour. As he made his way, he marveled that he should have had

notice brought upon himself, for he was young and diffident and

should by every token have escaped attention in these his first

days at court. How would his heart have grown tumultuous had he

known that none other than Arthur himself had made him choice. But

that he was not to know for many a year.

Night came on and the boy traveled far. Yet gave he no thought

to rest for he knew that he could ill afford to tarry and that only

with the best of fortune could he overtake the two knights in time

to make early return. About him the woods were dark and mysterious.

Owls hooted now and then and other sounds of the night there were,

yet was the boy so filled with urge of his mission that he found

not time to think of ghosts nor black magic.

Then, as he turned the road he saw the dim shadow of a horse.

Ghostly it seemed, until through closer view it proved flesh and

blood. Lying close by was a knight who seemed exceeding weak and

sorely wounded.

Quick from his horse came Allan and so made the strange knight

be of greater comfort.

Now the knight spoke weakly.

"Grievously have I been dealt with by an outlaw band. This day

was I to meet my two brothers Sir Ronald and Sir Marvin yet cannot

proceed for very weakness. Which way do you go, lad?"

"I keep on my way to Cornwall," replied Allan.

"From yonder do my brothers journey and should you meet with

them bid them hasten here so that together we can go forth to find

this outlaw band and it chastise."

"That shall I do. Sir Knight. It grieves me that I may not stay

and give you such aid as I may but so must I hasten that I cannot.

Yet shall I stop at first abode and commission them to hurry here

to you."

"For that I thank you, lad. And should time ever come when you

my aid require, know then to call on Philip of Gile."

So Allan pressed forward. At early dawn he came upon Sir Ronald

and Sir Marvin who had found rest along the wayside. And when he

found that these were the two knights he gave them their brother's

message.

"Then must we hasten thence, Ronald. And thank you, lad, for

bringing us this message. Choose you and you can rest awhile and

partake of such food that we have."

"Of food I will have, Sir Knights, for hunger calls most

urgently. But tarry I cannot for I must find Sir Launcelot and Sir

Gawaine. Mayhap you have met with them?"

"Of a truth can we say that we have met with them and suffered

thereby. Yet do we hold proof as to their knightly valor and skill.

They have gone but a little way, for it was their purpose to find

rest nearby. We doubt not you will find them at the first fair

abode. In the meantime must we hasten to our brother's aid and

leave our wounded comrades to such care as they may get."

The knights spoke truly, for Allan found upon inquiry that the

two he sought were lodged close by. Boldly the boy called, now for

Sir Launcelot, now for Sir Gawaine, but both were overtired and of

a great weariness and it took many minutes before at last Sir

Launcelot opened wide his eyes.

"And who are you, boy?" for he knew him not.

"My name is Allan and I am page to Sir Percival."

"Come you with a message from Sir Percival? Does he need our

help?"

"Nay, sir. Rather do I come with a message from the court--the

herald of which sent me urging you and Sir Gawaine to return before

sundown for a great conclave is to gather which the King himself

has called."

"Awaken then, thou sleepy knight," Sir Launcelot called to his

comrade who had not stirred. "It were pity that all this must be

told to you again."

Sir Gawaine now arose rubbing eyes still filled with sleep. To

him Allan repeated his message.

"What say you, Gawaine? Shall we return?"

"As for me," replied Sir Gawaine, "I would say no. What matter

if we are or are not present. Already we are late for our present

journey's purpose. So say I, let us not return but rather ask this

youth to bespeak for us the king's clemency."

"And I, too, am of the same mind, Gawaine. So lad," Sir

Launcelot turned to the boy and spoke kindly, "return you to court

and give them our message. This errand on which we are at present

bound holds urgent need, else would we return at our King's

behest."

Rueful and with a great gloom Allan saw his errand fail.

"Kind sirs, Sir Percival bid me bespeak for him as well, and ask

you, as true comrades, to make certain to return. Furthermore, my

knights, this, my first mission would be unfortunate if it did not

terminate successfully. So I pray you that you return."

Loud and long Sir Launcelot laughed and yet not unkindly while

Sir Gawaine placed hand upon the boy's shoulder approvingly.

"By my faith, Launcelot, we can do no more than return. That

Percival speaks counts for much, but this youth's honor is also at

stake." The light of laughter played in the speaker's eyes.

"Yes," said Sir Launcelot, "let us return. It would be pity to

send this lad back after his long journey, without success. So then

to our horses and let us make haste. The hours are few and the

miles many."

CHAPTER FIVE

Merlin's Message

Now as the sun, a flaming golden ball about which played the

wondrous softer colors of filmy clouds, began sinking in the

western horizon, the heralds announced everywhere that the time for

assemblage had come. Of those few who were not present, chiefest

were Sir Launcelot and Sir Gawaine. And for these two the herald of

King Arthur was searching the road in vain.

"Think you, Sir Percival, these two will come?" the herald,

anxious of tone, inquired. "Our King would have them present and I

fancy not the making of excuse for their not appearing."

"It is hard telling, Sir Herald. Far had the page to go and he

is young. Then too, it is a question whether should he meet with

them, these two have a mind to appear. For I know that their

journey to Cornwall is urgent."

Now the knights entered and found place. Then followed the

pages, squires and after them such yeoman and varlets as could find

room. After each had found his place, came King Arthur leading his

queen. And as they entered, up rose the knights, their vassals, all

that were within the hall and raised a mighty shout.

"St. George and Merrie England. Long live King Arthur. Long live

Queen Guenever."

Then turned the King toward his loyal subjects and though his

lips were seen to move, none heard him for the clamor. So King

Arthur turned to seat his queen and then he himself sat down upon

his throne, high on the dais.

Then soon after even as bell tolled the hour, Arthur arose. No

sign had yet come of Launcelot and Gawaine. So now the herald

slipped to the door to cast again a hurried glance for perchance

that they might be within vision. And as he went noiselessly, so,

too, a quiet fell that the King's words might be heard. But now

disturbing this quiet came a great clattering. Arthur turned his

eyes, frowning, at the sudden noise. Yet came a greater turmoil,

approaching horse's hoofs were heard and then into the great hall

thundered the steeds carrying the noble figures of Launcelot and

Gawaine, followed but a pace behind by Allan the page.

Straight to the dais they came, the two knights. Allan, however,

turned, made hasty exit because he felt himself abashed to be

observed by so many eyes. On foot he entered once again and found

place far in the rear where few could observe him.

The two knights now dismounted and knelt before their King.

"We pray your pardon for the lateness of our coming. Yet did we

hasten and could not have come the sooner."

"That we feel is so, Sir Knights, for we know you well enough.

Nor are we wroth, since come you did. But where, pray, is the

message bearer? Truly his speed was great to have reached you in

time for your return. And if I mistake not," added the King with

great shrewdness, "neither you, Gawaine, nor you Launcelot, were

any too ready to return. How then, did the lad urge you?"

"You speak truly, sire," replied Gawaine. "For our errand had

need of urgent haste and we were both to give it up. Yet did the

boy urge us and chiefest urge of all to us was where he claimed his

own honor demanded the success of his mission. Those were fine

words, so did we therefore return."

"Fine words, indeed. Where then is this page? Will you, Sir

Herald, bring him forth?"

So Allan came forward, red of face and hating such womanness

that would let him blush before all these great men. Knelt he

before his King.

"Thou art a good lad and will bear watching. Go thy way and

remember that the road ahead for those who wish to be knights of

high nobility is steep and arduous but well worth the trials.

Remember too, that this day, Britain's King, said that some day

thou wilt prove a worthy and brave knight."

And as Allan with flaming cheeks and glorious pride went to his

place far in the rear of the hall the King turned to the

assemblage.

"Merlin is here but departs from us tomorrow for many a day. He

has had a great dream which affects this court and us and which

must be told to all of you. So he has asked us to call you and this

we have done. Stand up now Merlin, wisest of men and truest of

counselors. Speak."

Up rose Merlin and for wonder as to what his dream might be all

held their breath.

"But the other night came Joseph of Armathea to me while I

slept. And he chided me that in all Britain so few of all the true

and brave knights had thought to seek the wondrous Holy Grail which

once was pride of all England.

"And me thought I heard him say, 'Truly do I misdoubt the valor

of these knights who seek adventure and glory.'

"'Yet.' said I, 'doubt not their valor for can I give surety for

it. For Holy Grail, every varlet, let alone those of true blood,

would give his life and count it more than worthy.'

"'So shall it be!' replied Sir Joseph. 'For the Holy Grail will

be found. Whether knight or varlet shall the finder be, I will not

say. But this I tell you now. He who finds it shall be pure of

heart and noble beyond all men. From whence he cometh, who he is, I

will not say. Remember this, Merlin, brave and noble knights there

are now in England, brave knights shall come, and some shall come

as strangely as shall the Grail. Many deeds will be done that will

bring truest of glory to England's name. And never again shall more

noble or more worthy knights hold Britain's banner so high. For

they who seek the Holy Grail must be worthy even of the search.'

"'Let your King beware that he listens well to all who come to

his court on every Pentecost. And though they who search may not be

overstrong, yet while they seek it they will find in themselves

many men's strength.'

"And then he left me. But even after he was gone I dreamt on.

And I say to you, oh men of England, go you forth and seek this

Holy Grail, if within you, you know that you are pure of heart and

noble. If you are not, go then and seek to be purified for that is

possible. Only one of you will find the Holy Grail, yet is there

great glory in the search. May he who finds it and all the rest who

search for it bring greater fame and worthiness to this our land

and to him who is our King."

Now Merlin turned to seat himself. But yet before he found his

place every man within the hall stood up prepared to make oath then

and there to begin the search. Only two kept still, nor did they

move. One was Sir Launcelot, the other the youth Allan.

But quick as they who upstood, Merlin spoke again. And though

his voice was low, yet was it heard throughout the hall.

"Pledge not yourself today, nor yet tomorrow. Go you hence,

first. In your innermost heart find answer to this question. Am I

pure, am I worthy for the search? For that you must be before any

pledge suffices."

Silent and thoughtful the men found each his seat. And when all

had been seated, Arthur, King, arose.

"Wouldst that I felt myself worthy. Yet from this day shall I

strive to the uttermost for the time when I shall feel that I

am."

And throughout the hall came answering vows: "So shall we all."

Within his heart, Allan, the youth, felt a strange radiancy, as he

too made this vow, "So shall I."

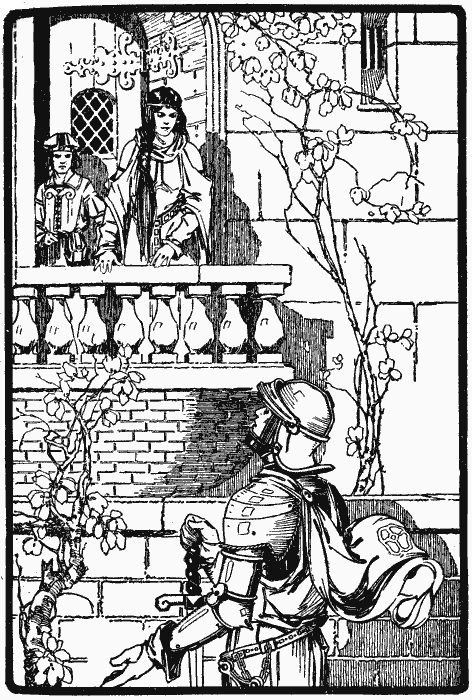

CHAPTER SIX

Yosalinde

Now came Pentecost and brought with it to King Arthur's

Tournament brave knights from everywhere. Distant Normandy, the far

shores of Ireland, sent each the flower of its knighthood.

Scotland's king was there, the brave Cadoris, to answer the

challenge of the King of Northgalis who was also present. Ban, King

of Northumberland, had come. Sir Palomides came too, and it was he

who was declared, by many to be the bravest and the most skillful

of all of Britain's knights. Yet there were equal number and more

who held the same for both Sir Launcelot and for Sir Tristram. Sir

Lauvecor, leading a hundred knights, came late, with the blessing

of his father, who was none other than King of Ireland.

A brave show they all made, these many knights seeking

adventure, and each, as he so easily bestrode his steed, found it

hard matter to find comrade and friend, for the many who were

there. Gay were the colors each knight wore and on some fortune had

smiled, for these carried token of some fair lady. Of fair ladies

there were many to watch the deeds of skill and bravery and most

beautiful of them all, was Arthur's queen, Guenever.

Sir Launcelot and Sir Gawaine had found no need to journey to

Cornwall. For word had come that Sir Tristram had had a bitter

quarrel with King Mark and had left his court carrying that wicked

King's curse. Tristram had made final demand on the traitorous King

to release the maiden Beatrice whom he was holding for ransom and

this the King had had no mind to do. Then had the bold knight

himself made for the door of the great dungeon and with hilt of

sword knocked long and loud to summon the keeper. And when the door

was opened this same keeper could not withstay him, nor would he.

Then had Tristram carried the maiden to point of safety and so

earned her gratitude. Nor would any knight of King Mark take issue

with him for none felt the King's deed to be knightly. And though

the King made pretense of bearing no ill will, yet did Sir Tristram

leave Cornwall that same day.

And Sir Gawaine knew not whether to be pleased or otherwise at

the news.

"I would have fancied making rescue of the Lady Beatrice myself.

And fancied even more to have told King Mark the scurvy knave I

deem him; yet I doubt not Sir Tristram did the deed well and since

it leaves me free to stay and have part in the jousting, I am not

displeased."

"And methinks," added Sir Launcelot, "Sir Tristram will make his

way hither, for tournament such as this holds all alluring

call."

King Arthur, together with Ban of Northumberland, and Sir

Percival were declared the judges for all but the last of the three

days.

Now then Sir Percival, finding a moment's brief respite,

followed by his page rode to the palace where sat his mother and

two sisters. There he found Sir Uwaine already in deep converse

with Helene, who was the older of the two maidens and whose knight

he was.

"See you, son, there do be knights who find time to pay respect

to us, even though our own are slower footed." So spoke the Lady

Olande yet did it jestingly and with no intent to hurt for she had

great love for her son.

"And I doubt not, Uwaine does make up for any seeming lack of

mine," replied Sir Percival. "If, mother mine, I were not made a

judge, my time would be more my own.

"But here, I must have lost what manners I have been taught.

Mother, this is Allan who is my page, and these, Allan, are my

sisters Helene and Yosalinde. Allan is son of Sir Gaunt, whom you

all know. Forgive my not making you known before this, lad."

Pleasantly did the ladies greet him and so well that he found no

embarrassment therewith. And so now Sir Percival turned and spoke

in low tones to his mother. Sir Uwaine and his lady walked away,

claiming that they must give greeting to certain high ladies. And

therewith left Allan, the boy, and Yosalinde, who was even younger

than he, to themselves.

Allan strove to speak but found he could not and so sat on horse

waiting. The girl calmly watched him from her place, yet was there

mischief in her eyes.

"If you would, you may dismount from your horse and find place

hither. There is room, as you see," she suggested.

The lad looked uncertain. Yet Sir Percival had already found

place next to his mother and was now in earnest converse. So he

found he could not do otherwise.

Now Yosalinde laughed at what showed so plainly his

unwillingness to sit beside her.

"I shall not bite you. See how harmless I am? No witch, I hope,

you think I am. For shame that youth, who would be brave knight,

should fear a lady and in especial one so young as I."

"I fear you not," replied Allan hotly.

"Then perhaps you dislike me?" the minx questioned

innocently.

"Certes, no. How could I?" the guileless youth replied.

"Then you do like me? Although I doubt I find any pride in that

since I must need force the words from you."

At a loss now the lad could not answer. For the girl had better

of him because of her quick tongue and he found she twisted his

words and meaning to suit her taste. Yet finally, she turned the

talk and so Allan found himself telling her of his high hopes. So

simply too, without boasting, he told her of the fine words of

Arthur to him. And last, because it had made its deep impress upon

him, he spoke of Merlin's dream. And of this Yosalinde, now serious

and wide eyed, questioned him closely, and soon knew all that he

did.

So now Percival uprose and made ready to return to his duties.

So therefore, too, did Allan, and found he now felt more at ease

and without constraint of the girl.

"I like you, Allan, and I say it though I

should make it harder for you to know, than it was for me. I give

you my friendship and if it help you, take this ring and wear it.

May it serve you in time of stress. And at all times consider it

token of your lady."

And then once again the laughing, teasing minx, she, added:

"Yet, after all, you are but a boy and I am no less a girl. Yet,

let us make-believe, you a bold knight and I your lady. Mayhap it

may be true some day."

So she was gone now to her mother leaving Allan with stirred

feelings and somewhat in a dream, too. For Sir Percival had to call

twice to him before he mounted his own horse. And even as they both

made their way, he turned his head back to see if he could perceive

aught of this strange girl. And thought he saw a waving hand but

was not sure.

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Tournament

On the first of the three days of the tournament there were

great feats of wrestling and trials of archery. So too did yeomen

prove their skill with mace and clubs. Foot races were many. And

constant flow of ale and food so that none among the yeomen and

even of the varlets found aught to want. Many fools there were too

and these pleased all mightily.

But as the day advanced of all the yeomen but a half dozen

remained for the wrestling. And for each of these but one, there

was high acclaim from those other yeomen who were there and from

such knights as owed fealty to selfsame banner. And of the archers

too, but very few remained for last tests of skill.

For the one yeoman, who wore green tunic and red cap, there was

none to cheer. A stranger, he kept silent and yet was equally

skillful with the best. He had entered himself for the archery

prize and for the wrestling.

"Dost know this knave?" asked King Arthur of Sir Percival.

"Only that he belongs not to any of us of the Round Table,"

replied Percival.

"Is he forsooth one of your men, worthy Ban?"

"I would he were, Arthur, yet is he not."

Now Sir Percival rode forward and divided these last six

wrestlers into teams. Yet did this man prove victor for he had a

wondrous hold which none of the others knew. And when he had won,

so turned he to watch and join in the archery. And as he watched

came there knaves to him and mocked him.

"Faith though you wrestle well," one spoke, "it doth not make

you an archer. For here you find true archery than which none can

do better."

"And I carry a club I would fain try on your thick skull," said

another who was even less gentle spoken.

"Of a good time, my friend, and you may," replied the lone

knave.

"No such time befits the same as now," replied the first

knave.

"If they will wait for my trial with bow and arrow I would be

the last to keep you waiting." So spoke the stranger.

So then one of the knaves hurried away and received

permission.

"Then furnish me a club," said the stranger.

"Here then is mine," offered the third knave.

Yet, forsooth, the club was but a sorry one and so the unknown

would not use it.

"Then show you a coward's heart," replied he who would strive

with him. And then the three rushed upon the stranger and would do

him hurt.

So now came bearing down on the three none other than Allan who

had overheard the parley.

"For shame, knaves. No true men would treat stranger so. He asks

nothing more than is fair. Give him a club of his choosing."

"Of a faith, young master, this quarrel is none of yours, and

warrants no interference. Leave this fellow to us, and we shall

give him clubbing of his choosing." And the man who addressed the

boy, though he looked not straight at him, growled surlily.

"I shall give you a thrashing, fool, unless you do my bidding,"

replied the boy, hotly.

But the three surly brutes moved uneasily. And then came Sir

Percival forward.

"What have we here?" he asked.

So Allan waited for the men to say. But they, now frightened,

made no spoken word.

"These knaves would play foul tricks on this strange fellow.

This one, would strive with him and yet would not offer other club

than this. And when the stranger asked to have one of his choice

they called him coward and would beat him."

"And I doubt not, fools, this club you offer will not stand one

blow." So Sir Percival brought it down on the first knave's head,

and, lo, though the blow was not a hard one, yet did the club break

in two.

"So methought. Now go you Allan and get club that will do. And

then will you, stranger, give this villain a sound trouncing." And

Sir Percival stayed so that the troublemakers did not depart.

So Allan brought a club which suited the stranger.

Now did the two battle long and well. Both the stranger and he

who fought with him were of great strength and each was exceeding

quick.

As wood struck wood and each tried to get full blow upon the

other, so turned all eyes upon the two. And except for glancing

blows neither could bring the other down. And though the sparks

flew, yet each held his club and was hardly hurt. So now they

rested for a few moments.

And while they waited, the stranger turned to Allan and

spoke.

"I thank you for your brave upstanding of me, young master. And

I hope some day I may serve you equally well."

"You are a worthy man. Serve me now by trouncing the knave who

battles with you."

"I can but try, yet right skillful is the fellow."

So they turned to again. Yet this time the stranger fought the

better. Soon the other was forced back, foot by foot. And even as

the stranger seemed to have all the best of it, his foot seeming

slipped, and he went to his knees.

Fiercely the other came upon him. Yet as he came closer the

stranger's club moved swiftly. From out the seeming victor's hand

flew his mighty club and next second found him clubbed to the

ground, senseless.

Now the stranger sat himself down for he needed rest sorely. But

only for a little while and thereafter he turned to try his skill

with bow and arrow. And though he had shown skill in all of the

other feats he proved his mastery here. For he was wondrous expert

in his archery.

"Here you, is fair target," he finally suggested after many

trials. And went to distant tree and removed from bough upon it,

all its leaves but one.

"Shoot you all at this. And if you bring it down I will call you

skillful."

But only one would try for it. And he came close but missed.

Now did the stranger raise his own bow. Nor did he seem to take

aim but let the arrow fly. And the arrow carried the twig and leaf

with it to the ground.

"Of a truth," said King Arthur, "a right worthy knave is that

and I would speak to him."

So they brought the stranger before the king.

"Thou hast done exceeding well, this day, fellow. Tell us then

the banner that you serve."

"That I cannot do. For, sire, such are my master's commands. Yet

may I say no knight is more true and worthy."

"Then must we wait for your master's coming. Go thou hence and

tell your master he can be proud of thee. And take you this bag of

gold besides such other prizes as are yours." So as the knave stood

there, the King turned to Sir Dagonet, his jester, who was making

himself heard.

"A fool speaks, sire. Yet claim I, like master like man. So then

must this fellow's master be right skillful to hold him. And since

this master is not you, nor Sir Launcelot, then I pick him to be

Sir Tristram."

"Fool's reasoning, yet hath it much sense," said the King.

Now the stranger left. But ere departing, he turned to

Allan.

"I trust, young master, I shall see you again. As to who I am,

know you for your own keeping--fools ofttimes reason best of

all."

The yeoman rode far into the forest. Then when he came to a lone

habitation he dismounted. A knight seated near the small window at

the further wall greeted him as he entered.

"How did the day turn out? No doubt they trounced you well."

"No, master, no trouncing did I get. Instead, the good King

spoke pleasantly unto me, gave me this bag of gold, and commended

me to my master. Furthermore, see you these prizes that are

mine?"

"Aye," the yeoman continued, not a bit grieved at the knight's

banter, "I even heard the King's fool remark that since the man was

so good, the master need must be. And then and there he hazarded a

shrewd guess that if this master were not the King, nor Sir

Launcelot, then it must need be you."

"Then truly am I in good company. Now then tell me what news is

there of tomorrow?"

"The King of Northgalis desires your aid. That I heard him say.

Sir Launcelot is to joust for Cadoris as is Sir Palomides, and

these two, of a truth, make it one-sided."

"Worthy Gouvernail, prove again my faith in you. Procure for me

a shield, one that holds no insignia, so that I may enter the lists

unbeknownst to any. I would not have them know I am Tristram, so

that it may be my good fortune to joust with many knights who know

me not."

"That, good master, is not hard. I know a place where I can

obtain a black shield, one that holds no other remembrance upon it.

It should serve your purpose well."

"By my faith, did ever better knave serve master? Right proud of

you am I, Gouvernail. And would that I too had bags of gold I could

give you for your loyal service."

"Nay, master, such service as I give I measure not by aught that

you can pay."

"That do I know full well, else had you left me long since, for

little have I paid," Sir Tristram answered, soft spoken and with

great affection.

CHAPTER EIGHT

Sir Tristram's Prowess

So the next day Sir Tristram, carrying the black shield, went

forth to enter the lists. And none knew him. The great conflict had

already begun when he arrived. He found himself a place among those

knights who jousted for Northgalis. And very soon all perceived

that this knight with the black shield was skillful and strong.

Well and lustily did he battle and none could withstand him. Yet

did he not meet with Sir Launcelot nor with Sir Palomides, on this

first day. Nor did any know him, but all marveled at his worth and

bravery.

So, as the day was done, this Unknown and his servant,

Gouvernail, rode back into the forest. And none followed him for he

was a brave knight and all respected him and his desire to stay

unknown. Yet did the judges declare the side of Northgalis victor

and as for single knight, the most worthy was the Unknown. And he

was called "the Knight of the Black Shield."

Now as the judges' duties were done, King Arthur showed how

wroth he was that strange knight had carried off such great

honors.

"Yet do we hope tomorrow shall show other reckoning than this.

For good Launcelot shall be there and so shall we."

On the morn the heralds called forth the brave knights once

again. And with the call came the "Knight of the Black Shield."

Sir Palomides was await for him, eager and alert, to be the

first to joust. And so they, like great hounds, went at each other.

And truly, Sir Tristram found his foe a worthy one. Long did they

joust without either besting the other until he of the black shield

by great skill and fine force brought down a mighty blow and did

smite Sir Palomides over his horse's croup. But now as the knight

fell King Arthur was there and he rode straight at the unknown

knight shouting, "Make thee ready for me!" Then the brave

sovereign, with eager heart, rode straight at him and as he came,

his horse reared high. And such was the King's strength he unhorsed

Sir Tristram.

Now, while the latter was on foot, rode full tilt upon him, Sir

Palomides, and would have borne him down but that Sir Tristram was

aware of his coming, and so lightly stepping aside, he grasped the

arm of the rider and pulled him from his horse. The two dashed

against each other on foot and with their swords battled so well

that kings and queens and knights and their ladies stood and beheld

them. But finally the Unknown smote his foe three mighty blows so

that he fell upon the earth groveling. Then did they all truly

wonder at his skill for Sir Palomides was thought by many to be the

most skillful knight in Britain.

A knight now brought horse for Sir Tristram, for now, all knew

that it must be he. So too was horse brought for Sir Palomides.

Great was the latter's ire and he came at Sir Tristram again. Full

force, he bore his lance at the other. And so anew they fought. Yet

Sir Tristram was the better of the two and soon with great strength

he got Sir Palomides by the neck with both hands and so pulled him

clean out of his saddle. Then in the presence of them all, and well

they marveled at his deed, he rode ten paces carrying the other in

this manner and let him fall as he might.

Sir Tristram turned now again and saw King Arthur with naked

sword ready for him. The former halted not, but rode straight at

the King with his lance. But as he came, the King by wondrous blow

sent his weapon flying and for a moment Sir Tristram was stunned.

And as he sat there upon his horse the King rained blows upon him

and yet did the latter draw forth his sword and assail the King so

hard that he need must give ground. Then were these two divided by

the great throng. But Sir Tristram, lion hearted, rode here and

there and battled with all who would. And of the knights who

opposed him he was victor of eleven. And all present marveled at

him, at his strength and at his great deeds.

Yet had he not met Sir Launcelot, who elsewhere was meeting with

all who would strive with him. Not many, however, would joust with

him for he was known as the very bravest and most skillful. So as

he sat there all at ease, there came the great acclaim for the

Knight of the Black Shield. Nor did Sir Launcelot know him to be

Sir Tristram. But he got his great lance and rushed toward the cry.

When he saw this strange knight he called to him, "Knight of the

Black Shield, prepare for me."

And then came such jousting as had never been seen. For each

knight bowed low his head and came at the other like the wind. When

they met it was very like thunder. Flashed lance on shields and

armor so that sparks flew. And each would not give to the other one

step but by great skill with shield did avoid the best of each

other's blows.

Then did Sir Tristram's lance break in two, and Sir Launcelot,

through further ill fortune, wounded Sir Tristram in his left side.

But notwithstanding, the wounded knight brought forth his sword and

rushed daringly at the other with a force that Sir Launcelot could

not withstand, and gave him a fearful blow. Low in his saddle

sagged Sir Launcelot, exceeding weak for many moments. Now Sir

Tristram left him so and rode into the forest. And after him

followed Gouvernail, his servant.

Sore wounded was Sir Tristram yet made he light of it. Sir

Launcelot on his part recovered soon and turned back to the

tourney, and thereafter did wondrous deeds and stood off many

knights, together and singly.

Now again was the day done and the tournament, too. And to Sir

Launcelot was given full honor as victor of the field. But naught

would Sir Launcelot have of this. He rode forthwith to his

King.

"Sire, it is not I but this knight with the Black Shield who has

shown most marvelous skill of all. And so I will not have these

prizes for they do not belong to me."

"Well spoken, Sir Launcelot and like thy true self," replied the

King. "So since this knight is gone, will you go forth with us

within the fortnight in search for him. And unless we are in great

error we shall find this Knight of the Black Shield no more, no

less, than Sir Tristram."

CHAPTER NINE

The Kitchen Boy

Among all those who came to the court of King Arthur at this

Pentecost seeking hospitality, were two strangers in especial, who

because of being meanly garbed and of a seeming awkwardness brought

forth the mockery and jest of Sir Kay the Seneschal. Nor did Sir

Kay mean harm thereby, for he was knight who held no villainy. Yet

was his tongue overly sharp and too oft disposed to sting and

mock.

Too, the manner of their coming was strange. One was a youth of

handsome mien. Despite his ill garb, he seemed of right good

worship. Him, our young page Allan found fallen in a swoon, very

weak and near unto death, asprawl on the green about a mile from

the castle. Thinking that the man was but a villain, he would fain

have called one of the men-at-arms to give him aid, but that

something drew him to closer view. And then the boy felt certain

that this was no villain born for his face bespoke gentle breeding.

So he himself hastened for water and by much use of it the man soon

opened his eyes and found himself. So he studied the lad as he

helped him to greater ease but either through his great weakness or

no desire he did not speak.

"Stranger," said Allan to the man, "if there is aught that I can

do for you or if I can help you in any way I give you offer of

service. Mayhap of the many knights who are here, there is one

whose aid you may justly claim."

The stranger held answer for many moments, then he spoke.

"There are those here, lad, whose service I may well accept for

they hold ties of blood to me. But I would not. Rather, if your

patience will bear with me, I would fain have your help so that I

can appear in the presence of the King this day. For so it is

ordained and by appearing there I shall find some part of my row

accomplished. On this holy day, I have boon to ask from your

King."

"So shall I and right gladly lead you there. Good sir, my name

is Allan. I am page to Sir Percival, and I would bespeak your

name."

"I beg of thee, Allan, think not that I am churlish and yet must

I withhold my name. For it is part of the vow I have made. Nor,

forsooth, am I therefore the less grateful."

"No offense take I, friend. So when you feel disposed I shall

guide your steps for audience with our good King."

The stranger, weak and spent, leaning mightily on his young

friend made his way to the great hall. And as we have recounted,

though all were struck by oddness and meanness of the stranger's

clothes, yet only Sir Kay made point to taunt him. Yet did he make

no answer to these taunts but waited with a great meekness for his

turn before the King. And that he should wait with such meekness

was strange for he seemed to be a high born knight.

There were many who sought audience with the King and it was

long before the stranger's turn came. Weak he still was, but he

made no complaint, and when others would crowd before him so that

they could speak the sooner to King Arthur, he did not chide them

but permitted it. At last Sir Launcelot came forward, for he had

observed this and made each of them find the place which was first

theirs, so that the stranger's turn came as it should. Weak though

he was he walked with a great firmness to the dais, and none there

saw his poor clothes for the fineness of him. The King turned to

him and he nodded kindly.

"Speak, friend. In what way can we be of service to thee?"

"Sire," said the stranger, "I come to ask of thee three boons.

One I ask this day and on this day one year I shall come before you

and crave your favor for the other two."

"If the boon you ask, stranger, is aught we can grant, we shall

do so cheerfully, for on this day we heed all prayers."

"I ask very little, sire. This and no more do I wish--that you

give me food and drink for one year and that on this day a year

hence I shall make my other two prayers."

"It is indeed little you ask. Food and drink we refuse none. It

is here. Yet while your petition might well beseem a knave, thou

seemeth of right good worship, a likely youth, too, none fairer,

and we would fain your prayer had been for horse and armor. Yet may

you have your wish. Sir Kay," and the King turned to his Seneschal,

"see you to it that this stranger finds his wish satisfied."

So the King turned to others present, for of those who sought

audience there were many. And so forgot all of the fair youth for

many a day.

Sir Kay laughed mockingly at the unknown.

"Of a truth this is villain born. For only such would ask for

food and drink of the King. So therefore he shall find place in our

kitchen. He shall help there, he shall have fat broth to satisfy

himself and in a year no hog shall be fatter. And we shall know him

as the Kitchen Boy."

"Sir Kay," frowned Sir Launcelot, "I pray you cease your

mocking. It is not seemly. This stranger, whosoever he may be, has

right to make whatsoever request he wishes."

"Nay, Sir Launcelot, of a truth, as he is, so has he asked."

"Yet I like not your mocking," said Sir Launcelot as he looked

frowningly at Sir Kay, while next to him stood Sir Gawaine and Sir

Percival, neither of whom could scarce contain himself.

"It is well, we know you, Sir Kay. Or, by our guardian saints we

would make you answer for your bitter tongue. But that we know it

belies a heart of kindness we would long since have found quarrel

with you." So spoke Sir Percival and Sir Gawaine nodded in

assent.

"Stay not any quarrel for any seeming knowledge of me, kind

friends," frowned back Sir Kay.

But the two knights moved away. Sir Kay was of great shame. And

so to cover it he turned to the stranger in great fury. "Come then

to your kennel, dog," he said.

Out flashed the sword of Sir Gawaine. Yet did Sir Launcelot

withhold him.

"Sir, I beg you to do me honor of feasting with us this

day?"

"I thank you Sir Launcelot. Yet must I go with Sir Kay and do

his bidding. There do be knights well worth their places at the

Round Table. And I note right well that they set high example to

those who are still but lads and who are to become knights in good

time. So to you all I give my thanks."

Then followed the stranger after Sir Kay while the three knights

and Allan watched him go and marveled at his meekness.

CHAPTER TEN

Pentecost

And so in turn came the second stranger before King Arthur.

Poorly clothed, too, yet had his coat once been rich cloth of gold.

Now it sat most crookedly upon him and was cut in many places so

that it but barely hung upon his shoulders.

"Sire," said the stranger, "you are known everywhere as the

noblest King in the world. And for that reason I come to you to be

made knight."

"Knights, good friend," replied the King, "are not so easily

made. Such knights as we do appoint must first prove their worth.

We know thee not, stranger, and know not the meaning of thy strange

garb. For truly, thou art a strange sight."

"I am Breunor le Noire and soon you will know that I am of good

kin. This coat I wear is token of vow made for vengeance. So, I

found it on my slain father and I seek his slayer. This day, oh

King, I go forth content, if you make promise that should I perform

knightly deed you will dub me knight of yours."

"Go thou forth, then. We doubt not that thou wilt prove thy true

valor and be worthy of knighthood. Yet proof must be there."

On this selfsame day, Breunor le Noire departed.

Next morn, the King together with Sir Launcelot, Sir Percival,

Sir Gawaine, Sir Pellimore, Sir Gilbert, Sir Neil and Sir Dagonet,

indeed a right goodly party, prepared to depart. Nor did they

purpose to return until they met with Sir Tristram, for King Arthur

was of great desire to have this good knight as one of the Round

Table.

Now as these, the flower of King Arthur's court, were waiting

for Sir Dagonet who was to be with them and who had delayed, Sir

Launcelot saw Allan the boy watching them from the side. Saw too,

the great wish in the lad's eyes. Nor did Allan see himself

observed for Sir Launcelot was not then with the others.

A thought came to this fine spirited knight and it brought great

and smiling good humor to his lips. He rode to Sir Percival's side

and the two whispered for many moments. Then did the two speak to

the King and he laughed, but did not turn to gaze at the boy. Sir

Gawaine now joined in the whispering. Then did all four laugh with

great merriment. So Sir Pellimore and the other knights inquired

the cause for the merriment and, being told, laughed too. Kindly

was the laughter, strong men these who could yet be gentle. Sir

Launcelot now turned and rode hard at the boy.

"And wherefore, lad," and dark was his frown and greatly wroth

he seemed, "do you stand here watching? Rude staring yours and no

fit homage to pay your betters. Perchance, we may all be

displeased, the King, Sir Percival, and all of us."

Now the lad's eyes clouded. To have displeased these knights,

the greatest men in all the world, for so he thought them. Then and

there he wished he could die. Woe had the knight's words brought to

him.

"Indeed, and I meant no disrespect, Sir Launcelot. Indeed--" and

said no more for he knew he would weep if he spoke further. So he

saw not the dancing laughter in the knight's eye, nor the wide

grins on the faces of the others.

"Yet we must punish thee, lad. So then prepare you to accompany

us. Get your horse at once. Nor will we listen to any prayer you

may make for not going because of your youth."

Agape, Allan turned to look at him. For he knew he could not

have heard aright. But now, as he looked, he saw that Sir Launcelot

was laughing and then as he turned wondering, he saw his own lord

and the King and the other knights watching him with great

glee.

"You mean then, that I--I--may go with all of you!"

And then so that there would be no chance of its being

otherwise, he rushed in mad haste to get his horse. Joy was the

wings which made his feet fly. He came back in quick time, a bit

uncertain, riding forward slowly, diffidently, and stopped a little

way from them, awaiting word. Then did Sir Launcelot ride to him

and place kindly arm about the youth and bring him among them

all.

Now Sir Dagonet was with them and they rode forth.

With the equipage came the hounds, for the first day of their

journey was to be given over to hunting. There came also the master

of the hounds who was to return with them at the close of the

hunt.

None other than the great Launcelot rode with Allan and none sat

straighter and more at ease in his saddle than the boy as they

passed the Queen, the Lady Olande, her two daughters and many other

ladies of the realm. Nor did the boy see any other than the minx

Yosalinde. But she--she did not seem to find him among the knights,

yet he wondered how she could help but see him. He would have liked

to call to her, "See, here am I among all these brave knights."

Instead he rode past very erect. If she would not see him, what

matter, since, he was there, one of the company.

Then, of a sudden, she smiled straight at him. So that for him

was the full glory of the world. And we doubt not, for that smile

he would have fought the bravest knight in all the world and found

man's strength therein.

Now the company found itself in the woods and many hours journey

away. So they rode hard for they liked not to tarry on the

road.

Long after midday, King Arthur and his men spread out for the

hunt. The forest in which they now found themselves held game and

wild animals in plenty. Soon thereafter did the hounds give tongue

for they had found the scent. No mean prey had they found though,

for the quarry gave them a long race. Close behind the hounds came

King Arthur and almost as close, Sir Percival and Sir

Launcelot.

Now, at last, the stag, a noble animal with wondrous horns,

lithe body and beautifully shaped limbs was at bay. Straight and

true, at its throat, flew the leader of the pack, and sank its

teeth deep into it, while above the King blew loud and long the

death note of the chase. No need for other hounds nor for weapons

of the men.

Dark had stolen over the forest when the men with huge appetites

came to sup. Juicy venison steak was there, so was the wild duck

and the pheasant in plenty. To the full they ate as did the few men

at arms that were with them.

Yet none stayed awake long thereafter. It had been an arduous

day. Allan alone was wide-awake; his eyes would not close. And he

knew of a certainty that he was the most fortunate lad in all the

world. When he should become a man, he would be--well, he was not

certain whether he would be like unto the King, Sir Percival or Sir

Launcelot. Yes, he did know, he would be like them all. Now there

came mixed thoughts of a maid who waved her hand and smiled at him.

And he felt of a precious ring upon his finger.

So now his eyes closed; he found himself seeking the Holy Grail.

And during all of the night dreamed that he had found it.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Allan Meets a Stranger

The noble cortege, after the first day's hunt, continued on its

journey.

It had reached Leek, in Stafford on the morn of the fifth day

ere word came of Sir Tristram. Here, was heard from some, Sir

Tristram was then on way to Scotland, and from still others, that

he was bound for Kinkenadon in Wales.

"By my faith," spoke Sir Gawaine, "there are none that are more

ready to testify to Sir Tristram's greatness and ability, too. Yet

still, have I many doubts as to his being both on way to Scotland

and to Wales as well."

"If it were left to me," said Sir Dagonet, "I would hie me to

Ireland. A likely spot to find him, say I. For there are none who

have said that they know of the good knight's journey

thitherward."

"We, for ourselves, think it best," the king interrupted, "to

tarry here this day. Our comrade, Pellimore, expresses great desire

to have us partake of his hospitality and we are fain, so to do.

What say you?"

"It were wisdom to do so, methinks," agreed Sir Percival.

"Tomorrow we may find here some further news of Sir Tristram's

way."

"Aye, sir knights," added Sir Launcelot, "for we need must know

whether we continue our travel north or west from this point."

So all of them were housed within the castle walls. And Sir

Pellimore spread bounteous feast before his guests at midday for he

held it high honor to be host to such as these.

Now, as the repast had been completed, Allan grew restless. He

was of a mind to ride forth and so craved permission from Sir

Percival who gave ready consent.

Forth he went and rode for many an hour. And then, since the day

had great heat, he found himself turn drowsy. Thereupon finding a

pleasant, shaded spot, he quickly made a couch of cedar boughs and

soon was fast asleep.

It seemed to the boy he had slept but few moments when his eyes

opened wide with the certainty that other eyes were directed upon

him. Nor was this mere fancy nor dream. Near him sat a monk, and

from under the black hood the face that peered forth at him was

gaunt, cadaverous, with eyes that seemed to burn straight through

the lad. But for the eyes, this figure could well have been carven,

so still and immovable did it sit there and gaze at the youth. Nor

did the monk speak far many minutes even though he must have known

that the boy was awake and watching him.

The sun now hung low in the sky. Allan knew that he must have

been asleep for at least two hours. He knew, too, that he should

rise and return to the castle, since the hour was already late and

his time overspent. Yet did the monk's eyes hold him to the spot.

Nor was the thing that held him there fear; rather could it be

described as the feeling one has before a devout, sacred and holy

presence. Despite the holy man's unworthy aspect he inspired no

fear in the lad.

"Allan, boy," and the lad wondered that the monk knew him by

name, "two things I know have been chief in your thoughts these

days." Kindly was the monk's tone. "What then are these two

things?"

No thought had the boy of the oddness of the monk's words, nor

of his questions. Nor of the fact that the monk seemed to be there

present. Somehow, the whole of it took on some great purport. Allan

stopped not to wonder, which the two things the monk mentioned were

uppermost in his mind but straightway made reply.

"Strange monk, I think and dream of the Holy Grail. And think

too of Yosalinde, sister to my Lord Percival. And of naught else so

much. But pray you, holy father, who are you?

"Truth, lad. As to who I am or as to where I come, know you

this. I come to you from that same place as do all dreams.

"Aye lad. Dreaming and fancying shall ever be yours. These son,

shall bring you the visions of tomorrow and many another day.

"I have come to tell you this, lad. But two years or more and

you shall start in earnest on your search for the Grail. And

whether you find the same, I shall not and cannot say, for the

finding depends on you. The way shall be hard, youth of many

dreams, though you will have help and guidance, too. But the great

inspiration for it all shall come to you from the second of these,

your two big thoughts.

"I sought you many a day, lad. Merlin has sounded the message

for me to all the knights of Britain. Once before, years ago, I

came to find the likely seeker for the Grail and thought that I had

found him. Yet did the crucible's test find some alloy and so I had

need to come again.

"Then," said Allan but barely comprehending, "you are none other

than Sir Joseph of Armathea."

"Lad, it matters not as to who and what I am. It is of you, we

are now concerned. Dear, dear, lad, they shall name you again and

the name which shall be yours shall ever after be symbolic with the

very best that manhood holds."

"Go your way, now. For I must speak with many more this day ere

I return. A knight comes but now, with whom I must hold counsel.

And I would fain speak to him, alone."

"True, father, I had best go. For Sir Percival will think me

thoughtless, if not worse. As to what you have said, I can do but

that best which is in me and ever seek to make that best better.