The Project Gutenberg eBook of Mr. Spaceship

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Mr. Spaceship

Author: Philip K. Dick

Release date: May 25, 2010 [eBook #32522]

Most recently updated: January 25, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Barbara Tozier and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MR. SPACESHIP ***

This etext was produced from Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy, January 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

A human brain-controlled spacecraft would

mean mechanical perfection. This was accomplished,

and something unforeseen: a strange entity called—

Mr. Spaceship

By

Philip K. Dick

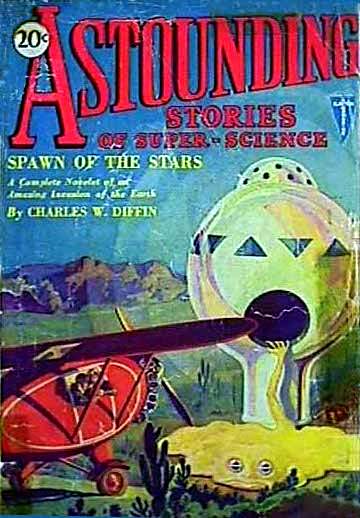

Left side image

Right side image

Kramer leaned back. “You

can see the situation. How

can we deal with a factor

like this? The perfect variable.”

“Perfect? Prediction should still

be possible. A living thing still

acts from necessity, the same as inanimate

material. But the cause-effect

chain is more subtle; there

are more factors to be considered.

The difference is quantitative, I

think. The reaction of the living

organism parallels natural causation,

but with greater complexity.”

Gross and Kramer looked up at the

board plates, suspended on the wall,

still dripping, the images hardening

into place. Kramer traced a line

with his pencil.

“See that? It’s a pseudopodium.

They’re alive, and so far, a weapon

we can’t beat. No mechanical system

can compete with that, simple

or intricate. We’ll have to scrap

the Johnson Control and find something

else.”

“Meanwhile the war continues as

it is. Stalemate. Checkmate. They

can’t get to us, and we can’t get

through their living minefield.”

Kramer nodded. “It’s a perfect

defense, for them. But there still

might be one answer.”

“What’s that?”

“Wait a minute.” Kramer turned

to his rocket expert, sitting with the

charts and files. “The heavy cruiser

that returned this week. It didn’t

actually touch, did it? It came

close but there was no contact.”

“Correct.” The expert nodded.

“The mine was twenty miles off.

The cruiser was in space-drive, moving

directly toward Proxima, line-straight,

using the Johnson Control,

of course. It had deflected a quarter

of an hour earlier for reasons unknown.

Later it resumed its

course. That was when they got

it.”

“It shifted,” Kramer said. “But

not enough. The mine was coming

along after it, trailing it. It’s the

same old story, but I wonder about

the contact.”

“Here’s our theory,” the expert

said. “We keep looking for contact,

a trigger in the pseudopodium.

But more likely we’re witnessing a

psychological phenomena, a decision

without any physical correlative.

We’re watching for something that

isn’t there. The mine decides to

blow up. It sees our ship, approaches,

and then decides.”

“Thanks.” Kramer turned to Gross.

“Well, that confirms what I’m saying.

How can a ship guided by automatic

relays escape a mine that decides

to explode? The whole theory

of mine penetration is that you

must avoid tripping the trigger. But

here the trigger is a state of mind

in a complicated, developed life-form.”

“The belt is fifty thousand miles

deep,” Gross added. “It solves another

problem for them, repair and

maintenance. The damn things reproduce,

fill up the spaces by

spawning into them. I wonder what

they feed on?”

“Probably the remains of our

first-line. The big cruisers must be

a delicacy. It’s a game of wits, between

a living creature and a ship

piloted by automatic relays. The

ship always loses.” Kramer opened a

folder. “I’ll tell you what I suggest.”

“Go on,” Gross said. “I’ve already

heard ten solutions today.

What’s yours?”

“Mine is very simple. These

creatures are superior to any mechanical

system, but only because

they’re alive. Almost any other

life-form could compete with them,

any higher life-form. If the yuks

can put out living mines to protect

their planets, we ought to be able

to harness some of our own life-forms

in a similar way. Let’s make

use of the same weapon ourselves.”

“Which life-form do you propose

to use?”

“I think the human brain is the

most agile of known living forms.

Do you know of any better?”

“But no human being can withstand

outspace travel. A human

pilot would be dead of heart failure

long before the ship got anywhere

near Proxima.”

“But we don’t need the whole

body,” Kramer said. “We need only

the brain.”

“What?”

“The problem is to find a person

of high intelligence who would contribute,

in the same manner that

eyes and arms are volunteered.”

“But a brain….”

“Technically, it could be done.

Brains have been transferred several

times, when body destruction

made it necessary. Of course, to a

spaceship, to a heavy outspace

cruiser, instead of an artificial body,

that’s new.”

The room was silent.

“It’s quite an idea,” Gross said

slowly. His heavy square face

twisted. “But even supposing it

might work, the big question is

whose brain?”

It was all very confusing, the

reasons for the war, the nature

of the enemy. The Yucconae had

been contacted on one of the outlying

planets of Proxima Centauri.

At the approach of the Terran ship,

a host of dark slim pencils had lifted

abruptly and shot off into the

distance. The first real encounter

came between three of the yuk pencils

and a single exploration ship

from Terra. No Terrans survived.

After that it was all out war, with

no holds barred.

Both sides feverishly constructed

defense rings around their systems.

Of the two, the Yucconae belt was

the better. The ring around Proxima

was a living ring, superior to

anything Terra could throw against

it. The standard equipment by

which Terran ships were guided in

outspace, the Johnson Control, was

not adequate. Something more was

needed. Automatic relays were not

good enough.

—Not good at all, Kramer

thought to himself, as he stood looking

down the hillside at the work

going on below him. A warm wind

blew along the hill, rustling the

weeds and grass. At the bottom, in

the valley, the mechanics had almost

finished; the last elements of

the reflex system had been removed

from the ship and crated

up.

All that was needed now was the

new core, the new central key that

would take the place of the mechanical

system. A human brain, the

brain of an intelligent, wary human

being. But would the human being

part with it? That was the problem.

Kramer turned. Two people were

approaching him along the road, a

man and a woman. The man was

Gross, expressionless, heavy-set,

walking with dignity. The woman

was—He stared in surprise and

growing annoyance. It was Dolores,

his wife. Since they’d separated he

had seen little of her….

“Kramer,” Gross said. “Look who

I ran into. Come back down with

us. We’re going into town.”

“Hello, Phil,” Dolores said.

“Well, aren’t you glad to see me?”

He nodded. “How have you been?

You’re looking fine.” She was still

pretty and slender in her uniform,

the blue-grey of Internal Security,

Gross’ organization.

“Thanks.” She smiled. “You seem

to be doing all right, too. Commander

Gross tells me that you’re

responsible for this project, Operation

Head, as they call it. Whose

head have you decided on?”

“That’s the problem.” Kramer lit

a cigarette. “This ship is to be

equipped with a human brain instead

of the Johnson system. We’ve

constructed special draining baths

for the brain, electronic relays to

catch the impulses and magnify

them, a continual feeding duct that

supplies the living cells with everything

they need. But—”

“But we still haven’t got the brain

itself,” Gross finished. They began

to walk back toward the car. “If

we can get that we’ll be ready for

the tests.”

“Will the brain remain alive?”

Dolores asked. “Is it actually going

to live as part of the ship?”

“It will be alive, but not conscious.

Very little life is actually

conscious. Animals, trees, insects

are quick in their responses, but

they aren’t conscious. In this process

of ours the individual personality,

the ego, will cease. We only

need the response ability, nothing

more.”

Dolores shuddered. “How terrible!”

“In time of war everything must

be tried,” Kramer said absently.

“If one life sacrificed will end the

war it’s worth it. This ship might

get through. A couple more like

it and there wouldn’t be any more

war.”

They got into the car. As they

drove down the road, Gross

said, “Have you thought of anyone

yet?”

Kramer shook his head. “That’s

out of my line.”

“What do you mean?”

“I’m an engineer. It’s not in my

department.”

“But all this was your idea.”

“My work ends there.”

Gross was staring at him oddly.

Kramer shifted uneasily.

“Then who is supposed to do it?”

Gross said. “I can have my organization

prepare examinations of various

kinds, to determine fitness,

that kind of thing—”

“Listen, Phil,” Dolores said suddenly.

“What?”

She turned toward him. “I have

an idea. Do you remember that

professor we had in college. Michael

Thomas?”

Kramer nodded.

“I wonder if he’s still alive.” Dolores

frowned. “If he is he must be

awfully old.”

“Why, Dolores?” Gross asked.

“Perhaps an old person who didn’t

have much time left, but whose

mind was still clear and sharp—”

“Professor Thomas.” Kramer rubbed

his jaw. “He certainly was a

wise old duck. But could he still

be alive? He must have been seventy,

then.”

“We could find that out,” Gross

said. “I could make a routine

check.”

“What do you think?” Dolores

said. “If any human mind could

outwit those creatures—”

“I don’t like the idea,” Kramer

said. In his mind an image had appeared,

the image of an old man sitting

behind a desk, his bright gentle

eyes moving about the classroom.

The old man leaning forward, a

thin hand raised—

“Keep him out of this,” Kramer

said.

“What’s wrong?” Gross looked at

him curiously.

“It’s because I suggested it,” Dolores

said.

“No.” Kramer shook his head.

“It’s not that. I didn’t expect

anything like this, somebody I knew,

a man I studied under. I remember

him very clearly. He was a very

distinct personality.”

“Good,” Gross said. “He sounds

fine.”

“We can’t do it. We’re asking

his death!”

“This is war,” Gross said, “and

war doesn’t wait on the needs of

the individual. You said that yourself.

Surely he’ll volunteer; we can

keep it on that basis.”

“He may already be dead,” Dolores

murmured.

“We’ll find that out,” Gross said

speeding up the car. They drove

the rest of the way in silence.

For a long time the two of them

stood studying the small wood

house, overgrown with ivy, set back

on the lot behind an enormous oak.

The little town was silent and

sleepy; once in awhile a car moved

slowly along the distant highway,

but that was all.

“This is the place,” Gross said to

Kramer. He folded his arms.

“Quite a quaint little house.”

Kramer said nothing. The two

Security Agents behind them were

expressionless.

Gross started toward the gate.

“Let’s go. According to the check

he’s still alive, but very sick. His

mind is agile, however. That seems

to be certain. It’s said he doesn’t

leave the house. A woman takes

care of his needs. He’s very frail.”

They went down the stone walk

and up onto the porch. Gross rang

the bell. They waited. After a

time they heard slow footsteps.

The door opened. An elderly woman

in a shapeless wrapper studied them

impassively.

“Security,” Gross said, showing

his card. “We wish to see Professor

Thomas.”

“Why?”

“Government business.” He glanced

at Kramer.

Kramer stepped forward. “I was

a pupil of the Professor’s,” he said.

“I’m sure he won’t mind seeing us.”

The woman hesitated uncertainly.

Gross stepped into the doorway.

“All right, mother. This is war

time. We can’t stand out here.”

The two Security agents followed

him, and Kramer came reluctantly

behind, closing the door. Gross

stalked down the hall until he came

to an open door. He stopped, looking

in. Kramer could see the white

corner of a bed, a wooden post and

the edge of a dresser.

He joined Gross.

In the dark room a withered old

man lay, propped up on endless pillows.

At first it seemed as if he

were asleep; there was no motion or

sign of life. But after a time Kramer

saw with a faint shock that

the old man was watching them intently,

his eyes fixed on them, unmoving,

unwinking.

“Professor Thomas?” Gross said.

“I’m Commander Gross of Security.

This man with me is perhaps known

to you—”

The faded eyes fixed on Kramer.

“I know him. Philip Kramer….

You’ve grown heavier, boy.” The

voice was feeble, the rustle of dry

ashes. “Is it true you’re married

now?”

“Yes. I married Dolores French.

You remember her.” Kramer came

toward the bed. “But we’re separated.

It didn’t work out very well.

Our careers—”

“What we came here about, Professor,”

Gross began, but Kramer

cut him off with an impatient wave.

“Let me talk. Can’t you and your

men get out of here long enough to

let me talk to him?”

Gross swallowed. “All right, Kramer.”

He nodded to the two men.

The three of them left the room,

going out into the hall and closing

the door after them.

The old man in the bed watched

Kramer silently. “I don’t think

much of him,” he said at last. “I’ve

seen his type before. What’s he

want?”

“Nothing. He just came along.

Can I sit down?” Kramer found a

stiff upright chair beside the bed.

“If I’m bothering you—”

“No. I’m glad to see you again,

Philip. After so long. I’m sorry

your marriage didn’t work out.”

“How have you been?”

“I’ve been very ill. I’m afraid

that my moment on the world’s

stage has almost ended.” The ancient

eyes studied the younger man

reflectively. “You look as if you

have been doing well. Like everyone

else I thought highly of. You’ve

gone to the top in this society.”

Kramer smiled. Then he became

serious. “Professor, there’s a project

we’re working on that I want

to talk to you about. It’s the first

ray of hope we’ve had in this whole

war. If it works, we may be able

to crack the yuk defenses, get some

ships into their system. If we can

do that the war might be brought

to an end.”

“Go on. Tell me about it, if you

wish.”

“It’s a long shot, this project.

It may not work at all, but we have

to give it a try.”

“It’s obvious that you came here

because of it,” Professor Thomas

murmured. “I’m becoming curious.

Go on.”

After Kramer finished the old

man lay back in the bed without

speaking. At last he sighed.

“I understand. A human mind,

taken out of a human body.” He

sat up a little, looking at Kramer.

“I suppose you’re thinking of me.”

Kramer said nothing.

“Before I make my decision I

want to see the papers on this, the

theory and outline of construction.

I’m not sure I like it.—For reasons

of my own, I mean. But I

want to look at the material. If

you’ll do that—”

“Certainly.” Kramer stood up

and went to the door. Gross and

the two Security Agents were standing

outside, waiting tensely. “Gross,

come inside.”

They filed into the room.

“Give the Professor the papers,”

Kramer said. “He wants to study

them before deciding.”

Gross brought the file out of his

coat pocket, a manila envelope. He

handed it to the old man on the

bed. “Here it is, Professor. You’re

welcome to examine it. Will you

give us your answer as soon as

possible? We’re very anxious to begin,

of course.”

“I’ll give you my answer when

I’ve decided.” He took the envelope

with a thin, trembling hand.

“My decision depends on what I

find out from these papers. If I

don’t like what I find, then I will

not become involved with this work

in any shape or form.” He opened

the envelope with shaking hands.

“I’m looking for one thing.”

“What is it?” Gross said.

“That’s my affair. Leave me a

number by which I can reach you

when I’ve decided.”

Silently, Gross put his card down

on the dresser. As they went out

Professor Thomas was already reading

the first of the papers, the

outline of the theory.

Kramer sat across from Dale

Winter, his second in line.

“What then?” Winter said.

“He’s going to contact us.” Kramer

scratched with a drawing pen

on some paper. “I don’t know what

to think.”

“What do you mean?” Winter’s

good-natured face was puzzled.

“Look.” Kramer stood up, pacing

back and forth, his hands in his uniform

pockets. “He was my teacher

in college. I respected him as a

man, as well as a teacher. He was

more than a voice, a talking book.

He was a person, a calm, kindly

person I could look up to. I always

wanted to be like him, someday.

Now look at me.”

“So?”

“Look at what I’m asking. I’m

asking for his life, as if he were

some kind of laboratory animal kept

around in a cage, not a man, a

teacher at all.”

“Do you think he’ll do it?”

“I don’t know.” Kramer went

to the window. He stood looking

out. “In a way, I hope not.”

“But if he doesn’t—”

“Then we’ll have to find somebody

else. I know. There would

be somebody else. Why did Dolores

have to—”

The vidphone rang. Kramer pressed

the button.

“This is Gross.” The heavy features

formed. “The old man called me.

Professor Thomas.”

“What did he say?” He knew;

he could tell already, by the sound

of Gross’ voice.

“He said he’d do it. I was a

little surprised myself, but apparently

he means it. We’ve already

made arrangements for his admission

to the hospital. His lawyer is

drawing up the statement of liability.”

Kramer only half heard. He nodded

wearily. “All right. I’m glad.

I suppose we can go ahead, then.”

“You don’t sound very glad.”

“I wonder why he decided to go

ahead with it.”

“He was very certain about it.”

Gross sounded pleased. “He called

me quite early. I was still in bed.

You know, this calls for a celebration.”

“Sure,” Kramer said. “It sure

does.”

Toward the middle of August

the project neared completion.

They stood outside in the hot autumn

heat, looking up at the sleek

metal sides of the ship.

Gross thumped the metal with

his hand. “Well, it won’t be long.

We can begin the test any time.”

“Tell us more about this,” an officer

in gold braid said. “It’s such

an unusual concept.”

“Is there really a human brain

inside the ship?” a dignitary asked,

a small man in a rumpled suit. “And

the brain is actually alive?”

“Gentlemen, this ship is guided by

a living brain instead of the usual

Johnson relay-control system. But

the brain is not conscious. It will

function by reflex only. The practical

difference between it and the

Johnson system is this: a human

brain is far more intricate than

any man-made structure, and its

ability to adapt itself to a situation,

to respond to danger, is far beyond

anything that could be artificially

built.”

Gross paused, cocking his ear.

The turbines of the ship were beginning

to rumble, shaking the

ground under them with a deep vibration.

Kramer was standing a

short distance away from the others,

his arms folded, watching silently.

At the sound of the turbines

he walked quickly around the

ship to the other side. A few workmen

were clearing away the last

of the waste, the scraps of wiring

and scaffolding. They glanced up

at him and went on hurriedly with

their work. Kramer mounted the

ramp and entered the control cabin

of the ship. Winter was sitting at

the controls with a Pilot from Space-transport.

“How’s it look?” Kramer asked.

“All right.” Winter got up. “He

tells me that it would be best to

take off manually. The robot controls—”

Winter hesitated. “I mean,

the built-in controls, can take over

later on in space.”

“That’s right,” the Pilot said.

“It’s customary with the Johnson

system, and so in this case we

should—”

“Can you tell anything yet?” Kramer

asked.

“No,” the Pilot said slowly. “I

don’t think so. I’ve been going over

everything. It seems to be in good

order. There’s only one thing I

wanted to ask you about.” He

put his hand on the control board.

“There are some changes here I

don’t understand.”

“Changes?”

“Alterations from the original design.

I wonder what the purpose

is.”

Kramer took a set of the plans

from his coat. “Let me look.” He

turned the pages over. The Pilot

watched carefully over his shoulder.

“The changes aren’t indicated on

your copy,” the Pilot said. “I

wonder—” He stopped. Commander

Gross had entered the control cabin.

“Gross, who authorized alterations?”

Kramer said. “Some of the

wiring has been changed.”

“Why, your old friend.” Gross

signaled to the field tower through

the window.

“My old friend?”

“The Professor. He took quite

an active interest.” Gross turned to

the Pilot. “Let’s get going. We

have to take this out past gravity

for the test they tell me. Well, perhaps

it’s for the best. Are you

ready?”

“Sure.” The Pilot sat down and

moved some of the controls around.

“Anytime.”

“Go ahead, then,” Gross said.

“The Professor—” Kramer began,

but at that moment there was

a tremendous roar and the ship

leaped under him. He grasped one

of the wall holds and hung on as

best he could. The cabin was filling

with a steady throbbing, the

raging of the jet turbines underneath

them.

The ship leaped. Kramer closed

his eyes and held his breath. They

were moving out into space, gaining

speed each moment.

“Well, what do you think?”

Winter said nervously.

“Is it time yet?”

“A little longer,” Kramer said.

He was sitting on the floor of the

cabin, down by the control wiring.

He had removed the metal covering-plate,

exposing the complicated

maze of relay wiring. He was studying

it, comparing it to the wiring

diagrams.

“What’s the matter?” Gross said.

“These changes. I can’t figure

out what they’re for. The only pattern

I can make out is that for

some reason—”

“Let me look,” the Pilot said. He

squatted down beside Kramer. “You

were saying?”

“See this lead here? Originally

it was switch controlled. It closed

and opened automatically, according

to temperature change. Now it’s

wired so that the central control

system operates it. The same with

the others. A lot of this was still

mechanical, worked by pressure,

temperature, stress. Now it’s under

the central master.”

“The brain?” Gross said. “You

mean it’s been altered so that the

brain manipulates it?”

Kramer nodded. “Maybe Professor

Thomas felt that no mechanical

relays could be trusted. Maybe he

thought that things would be happening

too fast. But some of these

could close in a split second. The

brake rockets could go on as quickly

as—”

“Hey,” Winter said from the control

seat. “We’re getting near the

moon stations. What’ll I do?”

They looked out the port. The

corroded surface of the moon gleamed

up at them, a corrupt and sickening

sight. They were moving

swiftly toward it.

“I’ll take it,” the Pilot said. He

eased Winter out of the way and

strapped himself in place. The ship

began to move away from the moon

as he manipulated the controls.

Down below them they could see

the observation stations dotting the

surface, and the tiny squares that

were the openings of the underground

factories and hangars. A

red blinker winked up at them and

the Pilot’s fingers moved on the

board in answer.

“We’re past the moon,” the Pilot

said, after a time. The moon had

fallen behind them; the ship was

heading into outer space. “Well,

we can go ahead with it.”

Kramer did not answer.

“Mr. Kramer, we can go ahead

any time.”

Kramer started. “Sorry. I was

thinking. All right, thanks.” He

frowned, deep in thought.

“What is it?” Gross asked.

“The wiring changes. Did you

understand the reason for them when

you gave the okay to the workmen?”

Gross flushed. “You know I

know nothing about technical material.

I’m in Security.”

“Then you should have consulted

me.”

“What does it matter?” Gross

grinned wryly. “We’re going to

have to start putting our faith in

the old man sooner or later.”

The Pilot stepped back from the

board. His face was pale and set.

“Well, it’s done,” he said. “That’s

it.”

“What’s done?” Kramer said.

“We’re on automatic. The brain.

I turned the board over to it—to

him, I mean. The Old Man.” The

Pilot lit a cigarette and puffed nervously.

“Let’s keep our fingers

crossed.”

The ship was coasting evenly, in

the hands of its invisible pilot.

Far down inside the ship, carefully

armoured and protected, a soft human

brain lay in a tank of liquid,

a thousand minute electric charges

playing over its surface. As the

charges rose they were picked up

and amplified, fed into relay systems,

advanced, carried on through

the entire ship—

Gross wiped his forehead nervously.

“So he is running it, now. I

hope he knows what he’s doing.”

Kramer nodded enigmatically. “I

think he does.”

“What do you mean?”

“Nothing.” Kramer walked to

the port. “I see we’re still moving

in a straight line.” He picked up

the microphone. “We can instruct

the brain orally, through this.” He

blew against the microphone experimentally.

“Go on,” Winter said.

“Bring the ship around half-right,”

Kramer said. “Decrease

speed.”

They waited. Time passed. Gross

looked at Kramer. “No change.

Nothing.”

“Wait.”

Slowly, the ship was beginning to

turn. The turbines missed, reducing

their steady beat. The ship was

taking up its new course, adjusting

itself. Nearby some space debris

rushed past, incinerating in the

blasts of the turbine jets.

“So far so good,” Gross said.

They began to breathe more easily.

The invisible pilot had taken

control smoothly, calmly. The ship

was in good hands. Kramer spoke

a few more words into the microphone,

and they swung again. Now

they were moving back the way

they had come, toward the moon.

“Let’s see what he does when we

enter the moon’s pull,” Kramer said.

“He was a good mathematician, the

old man. He could handle any kind

of problem.”

The ship veered, turning away

from the moon. The great eaten-away

globe fell behind them.

Gross breathed a sigh of relief.

“That’s that.”

“One more thing.” Kramer picked

up the microphone. “Return to the

moon and land the ship at the first

space field,” he said into it.

“Good Lord,” Winter murmured.

“Why are you—”

“Be quiet.” Kramer stood, listening.

The turbines gasped and

roared as the ship swung full around,

gaining speed. They were moving

back, back toward the moon again.

The ship dipped down, heading toward

the great globe below.

“We’re going a little fast,” the

Pilot said. “I don’t see how he

can put down at this velocity.”

The port filled up, as the globe

swelled rapidly. The Pilot hurried

toward the board, reaching for

the controls. All at once the ship

jerked. The nose lifted and the

ship shot out into space, away from

the moon, turning at an oblique angle.

The men were thrown to the

floor by the sudden change in

course. They got to their feet

again, speechless, staring at each

other.

The Pilot gazed down at the

board. “It wasn’t me! I didn’t

touch a thing. I didn’t even get

to it.”

The ship was gaining speed each

moment. Kramer hesitated. “Maybe

you better switch it back to manual.”

The Pilot closed the switch. He

took hold of the steering controls

and moved them experimentally.

“Nothing.” He turned around.

“Nothing. It doesn’t respond.”

No one spoke.

“You can see what has happened,”

Kramer said calmly. “The old

man won’t let go of it, now that he

has it. I was afraid of this when

I saw the wiring changes. Everything

in this ship is centrally controlled,

even the cooling system, the

hatches, the garbage release. We’re

helpless.”

“Nonsense.” Gross strode to the

board. He took hold of the wheel

and turned it. The ship continued

on its course, moving away from the

moon, leaving it behind.

“Release!” Kramer said into the

microphone. “Let go of the controls!

We’ll take it back. Release.”

“No good,” the Pilot said. “Nothing.”

He spun the useless wheel.

“It’s dead, completely dead.”

“And we’re still heading out,”

Winter said, grinning foolishly.

“We’ll be going through the first-line

defense belt in a few minutes.

If they don’t shoot us down—”

“We better radio back.” The Pilot

clicked the radio to send. “I’ll

contact the main bases, one of the

observation stations.”

“Better get the defense belt, at

the speed we’re going. We’ll be into

it in a minute.”

“And after that,” Kramer said,

“we’ll be in outer space. He’s moving

us toward outspace velocity. Is

this ship equipped with baths?”

“Baths?” Gross said.

“The sleep tanks. For space-drive.

We may need them if we

go much faster.”

“But good God, where are we going?”

Gross said. “Where—where’s

he taking us?”

The Pilot obtained contact. “This

is Dwight, on ship,” he said.

“We’re entering the defense zone

at high velocity. Don’t fire on us.”

“Turn back,” the impersonal

voice came through the speaker.

“You’re not allowed in the defense

zone.”

“We can’t. We’ve lost control.”

“Lost control?”

“This is an experimental ship.”

Gross took the radio. “This is

Commander Gross, Security. We’re

being carried into outer space.

There’s nothing we can do. Is there

any way that we can be removed

from this ship?”

A hesitation. “We have some

fast pursuit ships that could pick

you up if you wanted to jump. The

chances are good they’d find you.

Do you have space flares?”

“We do,” the Pilot said. “Let’s

try it.”

“Abandon ship?” Kramer said.

“If we leave now we’ll never see it

again.”

“What else can we do? We’re

gaining speed all the time. Do you

propose that we stay here?”

“No.” Kramer shook his head.

“Damn it, there ought to be a better

solution.”

“Could you contact him?” Winter

asked. “The Old Man? Try to

reason with him?”

“It’s worth a chance,” Gross said.

“Try it.”

“All right.” Kramer took the

microphone. He paused a moment.

“Listen! Can you hear me? This

is Phil Kramer. Can you hear me,

Professor. Can you hear me? I

want you to release the controls.”

There was silence.

“This is Kramer, Professor. Can

you hear me? Do you remember

who I am? Do you understand

who this is?”

Above the control panel the wall

speaker made a sound, a sputtering

static. They looked up.

“Can you hear me, Professor. This

is Philip Kramer. I want you to

give the ship back to us. If you

can hear me, release the controls!

Let go, Professor. Let go!”

Static. A rushing sound, like the

wind. They gazed at each other.

There was silence for a moment.

“It’s a waste of time,” Gross said.

“No—listen!”

The sputter came again. Then,

mixed with the sputter, almost lost

in it, a voice came, toneless, without

inflection, a mechanical, lifeless

voice from the metal speaker in

the wall, above their heads.

“… Is it you, Philip? I can’t

make you out. Darkness…. Who’s

there? With you….”

“It’s me, Kramer.” His fingers

tightened against the microphone

handle. “You must release the controls,

Professor. We have to get

back to Terra. You must.”

Silence. Then the faint, faltering

voice came again, a little stronger

than before. “Kramer. Everything

so strange. I was right, though.

Consciousness result of thinking.

Necessary result. Cognito ergo sum.

Retain conceptual ability. Can you

hear me?”

“Yes, Professor—”

“I altered the wiring. Control. I

was fairly certain…. I wonder if

I can do it. Try….”

Suddenly the air-conditioning

snapped into operation. It snapped

abruptly off again. Down the corridor

a door slammed. Something

thudded. The men stood listening.

Sounds came from all sides of them,

switches shutting, opening. The

lights blinked off; they were in

darkness. The lights came back on,

and at the same time the heating

coils dimmed and faded.

“Good God!” Winter said.

Water poured down on them, the

emergency fire-fighting system.

There was a screaming rush of air.

One of the escape hatches had slid

back, and the air was roaring frantically

out into space.

The hatch banged closed. The

ship subsided into silence. The heating

coils glowed into life. As suddenly

as it had begun the weird exhibition

ceased.

“I can do—everything,” the dry,

toneless voice came from the wall

speaker. “It is all controlled.

Kramer, I wish to talk to you. I’ve

been—been thinking. I haven’t

seen you in many years. A lot to

discuss. You’ve changed, boy. We

have much to discuss. Your wife—”

The Pilot grabbed Kramer’s arm.

“There’s a ship standing off our

bow. Look.”

They ran to the port. A slender

pale craft was moving along

with them, keeping pace with them.

It was signal-blinking.

“A Terran pursuit ship,” the Pilot

said. “Let’s jump. They’ll

pick us up. Suits—”

He ran to a supply cupboard and

turned the handle. The door opened

and he pulled the suits out onto

the floor.

“Hurry,” Gross said. A panic

seized them. They dressed frantically,

pulling the heavy garments

over them. Winter staggered to

the escape hatch and stood by it,

waiting for the others. They joined

him, one by one.

“Let’s go!” Gross said. “Open

the hatch.”

Winter tugged at the hatch. “Help

me.”

They grabbed hold, tugging together.

Nothing happened. The

hatch refused to budge.

“Get a crowbar,” the Pilot said.

“Hasn’t anyone got a blaster?”

Gross looked frantically around.

“Damn it, blast it open!”

“Pull,” Kramer grated. “Pull together.”

“Are you at the hatch?” the

toneless voice came, drifting and eddying

through the corridors of the

ship. They looked up, staring around

them. “I sense something nearby,

outside. A ship? You are leaving,

all of you? Kramer, you are leaving,

too? Very unfortunate. I had hoped

we could talk. Perhaps at some

other time you might be induced to

remain.”

“Open the hatch!” Kramer said,

staring up at the impersonal walls

of the ship. “For God’s sake, open

it!”

There was silence, an endless

pause. Then, very slowly, the hatch

slid back. The air screamed out,

rushing past them into space.

One by one they leaped, one after

the other, propelled away by

the repulsive material of the suits.

A few minutes later they were being

hauled aboard the pursuit ship.

As the last one of them was lifted

through the port, their own ship

pointed itself suddenly upward and

shot off at tremendous speed. It

disappeared.

Kramer removed his helmet, gasping.

Two sailors held onto him

and began to wrap him in blankets.

Gross sipped a mug of coffee, shivering.

“It’s gone,” Kramer murmured.

“I’ll have an alarm sent out,” Gross

said.

“What’s happened to your ship?”

a sailor asked curiously. “It sure

took off in a hurry. Who’s on it?”

“We’ll have to have it destroyed,”

Gross went on, his face grim. “It’s

got to be destroyed. There’s no telling

what it—what he has in mind.”

Gross sat down weakly on a metal

bench. “What a close call for us.

We were so damn trusting.”

“What could he be planning,”

Kramer said, half to himself. “It

doesn’t make sense. I don’t get it.”

As the ship sped back toward the

moon base they sat around the

table in the dining room, sipping hot

coffee and thinking, not saying very

much.

“Look here,” Gross said at last.

“What kind of man was Professor

Thomas? What do you remember

about him?”

Kramer put his coffee mug down.

“It was ten years ago. I don’t remember

much. It’s vague.”

He let his mind run back over

the years. He and Dolores had

been at Hunt College together, in

physics and the life sciences. The

College was small and set back

away from the momentum of modern

life. He had gone there because it

was his home town, and his father

had gone there before him.

Professor Thomas had been at

the College a long time, as long as

anyone could remember. He was a

strange old man, keeping to himself

most of the time. There were

many things that he disapproved of,

but he seldom said what they were.

“Do you recall anything that

might help us?” Gross asked. “Anything

that would give us a clue as

to what he might have in mind?”

Kramer nodded slowly. “I remember

one thing….”

One day he and the Professor

had been sitting together in the

school chapel, talking leisurely.

“Well, you’ll be out of school,

soon,” the Professor had said.

“What are you going to do?”

“Do? Work at one of the Government

Research Projects, I suppose.”

“And eventually? What’s your

ultimate goal?”

Kramer had smiled. “The question

is unscientific. It presupposes

such things as ultimate ends.”

“Suppose instead along these

lines, then: What if there were no

war and no Government Research

Projects? What would you do, then?”

“I don’t know. But how can I

imagine a hypothetical situation

like that? There’s been war as

long as I can remember. We’re geared

for war. I don’t know what I’d

do. I suppose I’d adjust, get used

to it.”

The Professor had stared at him.

“Oh, you do think you’d get accustomed

to it, eh? Well, I’m glad of

that. And you think you could

find something to do?”

Gross listened intently. “What

do you infer from this, Kramer?”

“Not much. Except that he was

against war.”

“We’re all against war,” Gross

pointed out.

“True. But he was withdrawn,

set apart. He lived very simply,

cooking his own meals. His wife

died many years ago. He was born

in Europe, in Italy. He changed his

name when he came to the United

States. He used to read Dante and

Milton. He even had a Bible.”

“Very anachronistic, don’t you

think?”

“Yes, he lived quite a lot in the

past. He found an old phonograph

and records, and he listened to the

old music. You saw his house, how

old-fashioned it was.”

“Did he have a file?” Winter

asked Gross.

“With Security? No, none at all.

As far as we could tell he never engaged

in political work, never joined

anything or even seemed to have

strong political convictions.”

“No,” Kramer, agreed. “About all

he ever did was walk through the

hills. He liked nature.”

“Nature can be of great use to

a scientist,” Gross said. “There

wouldn’t be any science without it.”

“Kramer, what do you think his

plan is, taking control of the ship

and disappearing?” Winter said.

“Maybe the transfer made him

insane,” the Pilot said. “Maybe

there’s no plan, nothing rational at

all.”

“But he had the ship rewired, and

he had made sure that he would retain

consciousness and memory before

he even agreed to the operation.

He must have had something

planned from the start. But what?”

“Perhaps he just wanted to stay

alive longer,” Kramer said. “He was

old and about to die. Or—”

“Or what?”

“Nothing.” Kramer stood up. “I

think as soon as we get to the moon

base I’ll make a vidcall to earth. I

want to talk to somebody about

this.”

“Who’s that?” Gross asked.

“Dolores. Maybe she remembers

something.”

“That’s a good idea,” Gross said.

“Where are you calling

from?” Dolores asked,

when he succeeded in reaching her.

“From the moon base.”

“All kinds of rumors are running

around. Why didn’t the ship come

back? What happened?”

“I’m afraid he ran off with it.”

“He?”

“The Old Man. Professor Thomas.”

Kramer explained what had

happened.

Dolores listened intently. “How

strange. And you think he planned

it all in advance, from the start?”

“I’m certain. He asked for the

plans of construction and the theoretical

diagrams at once.”

“But why? What for?”

“I don’t know. Look, Dolores.

What do you remember about him?

Is there anything that might give a

clue to all this?”

“Like what?”

“I don’t know. That’s the trouble.”

On the vidscreen Dolores knitted

her brow. “I remember he raised

chickens in his back yard, and once

he had a goat.” She smiled. “Do

you remember the day the goat got

loose and wandered down the main

street of town? Nobody could figure

out where it came from.”

“Anything else?”

“No.” He watched her struggling,

trying to remember. “He

wanted to have a farm, sometime, I

know.”

“All right. Thanks.” Kramer

touched the switch. “When I get

back to Terra maybe I’ll stop and

see you.”

“Let me know how it works out.”

He cut the line and the picture

dimmed and faded. He walked

slowly back to where Gross and

some officers of the Military were

sitting at a chart table, talking.

“Any luck?” Gross said, looking

up.

“No. All she remembers is that

he kept a goat.”

“Come over and look at this detail

chart.” Gross motioned him around

to his side. “Watch!”

Kramer saw the record tabs moving

furiously, the little white dots

racing back and forth.

“What’s happening?” he asked.

“A squadron outside the defense

zone has finally managed to contact

the ship. They’re maneuvering

now, for position. Watch.”

The white counters were forming

a barrel formation around a black

dot that was moving steadily across

the board, away from the central

position. As they watched, the

white dots constricted around it.

“They’re ready to open fire,” a

technician at the board said. “Commander,

what shall we tell them to

do?”

Gross hesitated. “I hate to be

the one who makes the decision.

When it comes right down to it—”

“It’s not just a ship,” Kramer

said. “It’s a man, a living person.

A human being is up there, moving

through space. I wish we knew

what—”

“But the order has to be given.

We can’t take any chances. Suppose

he went over to them, to the

yuks.”

Kramer’s jaw dropped. “My God,

he wouldn’t do that.”

“Are you sure? Do you know

what he’ll do?”

“He wouldn’t do that.”

Gross turned to the technician.

“Tell them to go ahead.”

“I’m sorry, sir, but now the ship

has gotten away. Look down at the

board.”

Gross stared down, Kramer over

his shoulder. The black dot

had slipped through the white dots

and had moved off at an abrupt angle.

The white dots were broken

up, dispersing in confusion.

“He’s an unusual strategist,” one

of the officers said. He traced the

line. “It’s an ancient maneuver, an

old Prussian device, but it worked.”

The white dots were turning back.

“Too many yuk ships out that far,”

Gross said. “Well, that’s what you

get when you don’t act quickly.” He

looked up coldly at Kramer. “We

should have done it when we had

him. Look at him go!” He jabbed

a finger at the rapidly moving black

dot. The dot came to the edge of

the board and stopped. It had

reached the limit of the chartered

area. “See?”

—Now what? Kramer thought,

watching. So the Old Man had escaped

the cruisers and gotten away.

He was alert, all right; there was

nothing wrong with his mind. Or

with his ability to control his new body.

Body—The ship was a new

body for him. He had traded in

the old dying body, withered and

frail, for this hulking frame of metal

and plastic, turbines and rocket jets.

He was strong, now. Strong and

big. The new body was more

powerful than a thousand human

bodies. But how long would it last

him? The average life of a cruiser

was only ten years. With careful

handling he might get twenty out of

it, before some essential part failed

and there was no way to replace it.

And then, what then? What

would he do, when something failed

and there was no one to fix it for

him? That would be the end. Someplace,

far out in the cold darkness

of space, the ship would slow down,

silent and lifeless, to exhaust its last

heat into the eternal timelessness of

outer space. Or perhaps it would

crash on some barren asteroid, burst

into a million fragments.

It was only a question of time.

“Your wife didn’t remember anything?”

Gross said.

“I told you. Only that he kept

a goat, once.”

“A hell of a lot of help that is.”

Kramer shrugged. “It’s not my

fault.”

“I wonder if we’ll ever see him

again.” Gross stared down at the indicator

dot, still hanging at the

edge of the board. “I wonder if

he’ll ever move back this way.”

“I wonder, too,” Kramer said.

That night Kramer lay in bed,

tossing from side to side, unable

to sleep. The moon gravity,

even artificially increased, was unfamiliar

to him and it made him

uncomfortable. A thousand thoughts

wandered loose in his head as he

lay, fully awake.

What did it all mean? What was

the Professor’s plan? Maybe they

would never know. Maybe the ship

was gone for good; the Old Man

had left forever, shooting into outer

space. They might never find out

why he had done it, what purpose—if

any—had been in his mind.

Kramer sat up in bed. He turned

on the light and lit a cigarette. His

quarters were small, a metal-lined

bunk room, part of the moon station

base.

The Old Man had wanted to talk

to him. He had wanted to discuss

things, hold a conversation, but in

the hysteria and confusion all they

had been able to think of was getting

away. The ship was rushing

off with them, carrying them into

outer space. Kramer set his jaw.

Could they be blamed for jumping?

They had no idea where they were

being taken, or why. They were

helpless, caught in their own ship,

and the pursuit ship standing by

waiting to pick them up was their

only chance. Another half hour

and it would have been too late.

But what had the Old Man wanted

to say? What had he intended

to tell him, in those first confusing

moments when the ship around them

had come alive, each metal strut and

wire suddenly animate, the body of

a living creature, a vast metal organism?

It was weird, unnerving. He could

not forget it, even now. He looked

around the small room uneasily.

What did it signify, the coming to

life of metal and plastic? All at

once they had found themselves inside

a living creature, in its stomach,

like Jonah inside the whale.

It had been alive, and it had talked

to them, talked calmly and rationally,

as it rushed them off, faster

and faster into outer space. The

wall speaker and circuit had become

the vocal cords and mouth, the

wiring the spinal cord and nerves,

the hatches and relays and circuit

breakers the muscles.

They had been helpless, completely

helpless. The ship had, in a brief

second, stolen their power away

from them and left them defenseless,

practically at its mercy. It was

not right; it made him uneasy. All

his life he had controlled machines,

bent nature and the forces of nature

to man and man’s needs. The

human race had slowly evolved until

it was in a position to operate things,

run them as it saw fit. Now all at

once it had been plunged back down

the ladder again, prostrate before a

Power against which they were children.

Kramer got out of bed. He put

on his bathrobe and began to search

for a cigarette. While he was searching,

the vidphone rang.

He snapped the vidphone on.

“Yes?”

The face of the immediate monitor

appeared. “A call from Terra,

Mr. Kramer. An emergency call.”

“Emergency call? For me? Put

it through.” Kramer came awake,

brushing his hair back out of his

eyes. Alarm plucked at him.

From the speaker a strange voice

came. “Philip Kramer? Is this

Kramer?”

“Yes. Go on.”

“This is General Hospital, New

York City, Terra. Mr. Kramer, your

wife is here. She has been critically

injured in an accident. Your

name was given to us to call. Is it

possible for you to—”

“How badly?” Kramer gripped

the vidphone stand. “Is it serious?”

“Yes, it’s serious, Mr. Kramer.

Are you able to come here? The

quicker you can come the better.”

“Yes.” Kramer nodded. “I’ll

come. Thanks.”

The screen died as the connection

was broken. Kramer

waited a moment. Then he tapped

the button. The screen relit again.

“Yes, sir,” the monitor said.

“Can I get a ship to Terra at

once? It’s an emergency. My wife—”

“There’s no ship leaving the moon

for eight hours. You’ll have to

wait until the next period.”

“Isn’t there anything I can do?”

“We can broadcast a general request

to all ships passing through

this area. Sometimes cruisers pass

by here returning to Terra for repairs.”

“Will you broadcast that for me?

I’ll come down to the field.”

“Yes sir. But there may be no

ship in the area for awhile. It’s a

gamble.” The screen died.

Kramer dressed quickly. He put

on his coat and hurried to the lift.

A moment later he was running

across the general receiving lobby,

past the rows of vacant desks and

conference tables. At the door the

sentries stepped aside and he went

outside, onto the great concrete

steps.

The face of the moon was in

shadow. Below him the field

stretched out in total darkness, a

black void, endless, without form.

He made his way carefully down the

steps and along the ramp along the

side of the field, to the control

tower. A faint row of red lights

showed him the way.

Two soldiers challenged him at

the foot of the tower, standing in

the shadows, their guns ready.

“Kramer?”

“Yes.” A light was flashed in

his face.

“Your call has been sent out already.”

“Any luck?” Kramer asked.

“There’s a cruiser nearby that

has made contact with us. It has

an injured jet and is moving slowly

back toward Terra, away from

the line.”

“Good.” Kramer nodded, a flood

of relief rushing through him. He

lit a cigarette and gave one to each

of the soldiers. The soldiers lit up.

“Sir,” one of them asked, “is it

true about the experimental ship?”

“What do you mean?”

“It came to life and ran off?”

“No, not exactly,” Kramer said.

“It had a new type of control system

instead of the Johnson units. It

wasn’t properly tested.”

“But sir, one of the cruisers that

was there got up close to it, and a

buddy of mine says this ship acted

funny. He never saw anything like

it. It was like when he was fishing

once on Terra, in Washington State,

fishing for bass. The fish were

smart, going this way and that—”

“Here’s your cruiser,” the other

soldier said. “Look!”

An enormous vague shape was setting

slowly down onto the field.

They could make nothing out but

its row of tiny green blinkers. Kramer

stared at the shape.

“Better hurry, sir,” the soldiers

said. “They don’t stick around

here very long.”

“Thanks.” Kramer loped across

the field, toward the black shape

that rose up above him, extended

across the width of the field. The

ramp was down from the side of the

cruiser and he caught hold of it.

The ramp rose, and a moment later

Kramer was inside the hold of the

ship. The hatch slid shut behind

him.

As he made his way up the stairs

to the main deck the turbines roared

up from the moon, out into space.

Kramer opened the door to the

main deck. He stopped suddenly,

staring around him in surprise.

There was nobody in sight. The

ship was deserted.

“Good God,” he said. Realization

swept over him, numbing him. He

sat down on a bench, his head swimming.

“Good God.”

The ship roared out into space

leaving the moon and Terra farther

behind each moment.

And there was nothing he could

do.

“So it was you who put the call

through,” he said at last. “It

was you who called me on the vidphone,

not any hospital on Terra.

It was all part of the plan.” He

looked up and around him. “And

Dolores is really—”

“Your wife is fine,” the wall

speaker above him said tonelessly.

“It was a fraud. I am sorry to

trick you that way, Philip, but it

was all I could think of. Another

day and you would have been back

on Terra. I don’t want to remain

in this area any longer than necessary.

They have been so certain

of finding me out in deep space that

I have been able to stay here without

too much danger. But even

the purloined letter was found eventually.”

Kramer smoked his cigarette nervously.

“What are you going to

do? Where are we going?”

“First, I want to talk to you. I

have many things to discuss. I

was very disappointed when you left

me, along with the others. I had

hoped that you would remain.” The

dry voice chuckled. “Remember

how we used to talk in the old days,

you and I? That was a long time

ago.”

The ship was gaining speed. It

plunged through space at tremendous

speed, rushing through the

last of the defense zone and out beyond.

A rush of nausea made Kramer

bend over for a moment.

When he straightened up the

voice from the wall went on, “I’m

sorry to step it up so quickly, but

we are still in danger. Another few

moments and we’ll be free.”

“How about yuk ships? Aren’t

they out here?”

“I’ve already slipped away from

several of them. They’re quite

curious about me.”

“Curious?”

“They sense that I’m different,

more like their own organic mines.

They don’t like it. I believe they will

begin to withdraw from this area,

soon. Apparently they don’t want

to get involved with me. They’re

an odd race, Philip. I would have

liked to study them closely, try to

learn something about them. I’m

of the opinion that they use no inert

material. All their equipment

and instruments are alive, in some

form or other. They don’t construct

or build at all. The idea of

making is foreign to them. They

utilize existing forms. Even their

ships—”

“Where are we going?” Kramer

said. “I want to know where you

are taking me.”

“Frankly, I’m not certain.”

“You’re not certain?”

“I haven’t worked some details

out. There are a few vague spots in

my program, still. But I think that

in a short while I’ll have them

ironed out.”

“What is your program?” Kramer

said.

“It’s really very simple. But don’t

you want to come into the control

room and sit? The seats are much

more comfortable than that metal

bench.”

Kramer went into the control

room and sat down at the control

board. Looking at the useless apparatus

made him feel strange.

“What’s the matter?” the speaker

above the board rasped.

Kramer gestured helplessly.

“I’m—powerless. I can’t do

anything. And I don’t like it. Do

you blame me?”

“No. No, I don’t blame you.

But you’ll get your control back,

soon. Don’t worry. This is only

a temporary expedient, taking you

off this way. It was something I

didn’t contemplate. I forgot that

orders would be given out to shoot

me on sight.”

“It was Gross’ idea.”

“I don’t doubt that. My conception,

my plan, came to me as

soon as you began to describe your

project, that day at my house. I

saw at once that you were wrong;

you people have no understanding

of the mind at all. I realized that

the transfer of a human brain from

an organic body to a complex artificial

space ship would not involve

the loss of the intellectualization faculty

of the mind. When a man

thinks, he is.

“When I realized that, I saw

the possibility of an age-old dream

becoming real. I was quite elderly

when I first met you, Philip. Even

then my life-span had come pretty

much to its end. I could look ahead

to nothing but death, and with it

the extinction of all my ideas. I

had made no mark on the world,

none at all. My students, one by

one, passed from me into the world,

to take up jobs in the great Research

Project, the search for better

and bigger weapons of war.

“The world has been fighting for

a long time, first with itself, then

with the Martians, then with these

beings from Proxima Centauri,

whom we know nothing about. The

human society has evolved war as

a cultural institution, like the science

of astronomy, or mathematics.

War is a part of our lives, a career,

a respected vocation. Bright, alert

young men and women move into

it, putting their shoulders to the

wheel as they did in the time of

Nebuchadnezzar. It has always

been so.

“But is it innate in mankind? I

don’t think so. No social custom

is innate. There were many human

groups that did not go to war;

the Eskimos never grasped the idea

at all, and the American Indians

never took to it well.

“But these dissenters were wiped

out, and a cultural pattern was established

that became the standard

for the whole planet. Now it

has become ingrained in us.

“But if someplace along the line

some other way of settling problems

had arisen and taken hold, something

different than the massing of

men and material to—”

“What’s your plan?” Kramer said.

“I know the theory. It was part

of one of your lectures.”

“Yes, buried in a lecture on plant

selection, as I recall. When you

came to me with this proposition I

realized that perhaps my conception

could be brought to life, after all.

If my theory were right that war

is only a habit, not an instinct, a

society built up apart from Terra

with a minimum of cultural roots

might develop differently. If it

failed to absorb our outlook, if it

could start out on another foot, it

might not arrive at the same point

to which we have come: a dead end,

with nothing but greater and greater

wars in sight, until nothing is left

but ruin and destruction everywhere.

“Of course, there would have to

be a Watcher to guide the experiment,

at first. A crisis would undoubtedly

come very quickly, probably

in the second generation. Cain

would arise almost at once.

“You see, Kramer, I estimate that

if I remain at rest most of the time,

on some small planet or moon, I

may be able to keep functioning for

almost a hundred years. That would

be time enough, sufficient to see

the direction of the new colony. After

that—Well, after that it would

be up to the colony itself.

“Which is just as well, of course.

Man must take control eventually,

on his own. One hundred years,

and after that they will have control

of their own destiny. Perhaps

I am wrong, perhaps war is more

than a habit. Perhaps it is a law

of the universe, that things can only

survive as groups by group violence.

“But I’m going ahead and taking

the chance that it is only a habit,

that I’m right, that war is something

we’re so accustomed to that

we don’t realize it is a very unnatural

thing. Now as to the place!

I’m still a little vague about that.

We must find the place, still.

“That’s what we’re doing now.

You and I are going to inspect a few

systems off the beaten path, planets

where the trading prospects are low

enough to keep Terran ships away.

I know of one planet that might be

a good place. It was reported by

the Fairchild Expedition in their

original manual. We may look into

that, for a start.”

The ship was silent.

Kramer sat for a time, staring

down at the metal floor under

him. The floor throbbed dully

with the motion of the turbines. At

last he looked up.

“You might be right. Maybe our

outlook is only a habit.” Kramer

got to his feet. “But I wonder if

something has occurred to you?”

“What is that?”

“If it’s such a deeply ingrained

habit, going back thousands of

years, how are you going to get

your colonists to make the break,

leave Terra and Terran customs?

How about this generation, the first

ones, the people who found the colony?

I think you’re right that the

next generation would be free of all

this, if there were an—” He grinned.

“—An Old Man Above to

teach them something else instead.”

Kramer looked up at the wall

speaker. “How are you going to

get the people to leave Terra and

come with you, if by your own theory,

this generation can’t be saved,

it all has to start with the next?”

The wall speaker was silent. Then

it made a sound, the faint dry

chuckle.

“I’m surprised at you, Philip.

Settlers can be found. We won’t

need many, just a few.” The speaker

chuckled again. “I’ll acquaint

you with my solution.”

At the far end of the corridor

a door slid open. There was sound,

a hesitant sound. Kramer turned.

“Dolores!”

Dolores Kramer stood uncertainly,

looking into the control room. She

blinked in amazement. “Phil! What

are you doing here? What’s going

on?”

They stared at each other.

“What’s happening?” Dolores

said. “I received a vidcall that you

had been hurt in a lunar explosion—”

The wall speaker rasped into life.

“You see, Philip, that problem is already

solved. We don’t really need

so many people; even a single couple

might do.”

Kramer nodded slowly. “I see,”

he murmured thickly. “Just one

couple. One man and woman.”

“They might make it all right, if

there were someone to watch and

see that things went as they should.

There will be quite a few things I

can help you with, Philip. Quite a

few. We’ll get along very well, I

think.”

Kramer grinned wryly. “You

could even help us name the animals,”

he said. “I understand that’s

the first step.”

“I’ll be glad to,” the toneless,

impersonal voice said. “As I recall,

my part will be to bring them

to you, one by one. Then you can

do the actual naming.”

“I don’t understand,” Dolores

faltered. “What does he mean,

Phil? Naming animals. What kind

of animals? Where are we going?”

Kramer walked slowly over to the

port and stood staring silently out,

his arms folded. Beyond the ship

a myriad fragments of light gleamed,

countless coals glowing in the dark

void. Stars, suns, systems. Endless,

without number. A universe of

worlds. An infinity of planets,

waiting for them, gleaming and

winking from the darkness.

He turned back, away from the

port. “Where are we going?” He

smiled at his wife, standing nervous

and frightened, her large eyes full

of alarm. “I don’t know where we

are going,” he said. “But somehow

that doesn’t seem too important

right now…. I’m beginning to see

the Professor’s point, it’s the result

that counts.”

And for the first time in many

months he put his arm around Dolores.

At first she stiffened, the

fright and nervousness still in her

eyes. But then suddenly she relaxed

against him and there were tears

wetting her cheeks.

“Phil … do you really think we

can start over again—you and I?”

He kissed her tenderly, then passionately.

And the spaceship shot swiftly

through the endless, trackless eternity

of the void….

Featured Books

Bees from British Guiana

Theodore D. A. Cockerell

arked K. occur at Kalacoon.The body, or some part of it, brilliant greenNo part of the body brillian...

Mammals of Northwestern South Dakota

J. Knox Jones and Kenneth W. Andersen

g County has an area of approximately 2700 square miles (Fig. 1).The county first was organized in 1...

Mr. Standfast

John Buchan

of the window of a first-classcarriage, the next in a local motor-car following the course of a tro...

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

G. A. Henty

gnificant minority of the Commons, backed by thestrength of the army—in the establishment of the m...

Four Young Explorers; Or, Sight-Seeing in the Tropics

Oliver Optic

Volume of Third Series Four Young ExplorersORSIGHT-SEEING IN THE TROPICSBYOLIVER OPTICAUTHOR OF"THE...

Mr. Punch in the Hunting Field

ONAL BOOK CO. LTD.[Pg 4]THE PUNCH LIBRARY OF HUMOURTwenty-five volumes, crown 8vo. 192 pagesfully il...

Five Thousand Miles Underground; Or, the Mystery of the Centre of the Earth

Roy Rockwood

EARTHXIVMANY MILES BELOWXVIN THE STRANGE DRAUGHTXVITHE NEW LANDXVIIA STRANGE COUNTRYXVIIICAUGHT BY ...

The Metal Monster

Abraham Merritt

XXVI. THE VENGEANCE OF NORHALA CHAPTER XXVII. "THE DRUMS OF DESTINY” CHAPTER XX...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "Mr. Spaceship" :