The Project Gutenberg eBook of Mike

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Mike

Author: P. G. Wodehouse

Release date: February 1, 2005 [eBook #7423]

Most recently updated: May 1, 2023

Language: English

Credits: Suzanne L. Shell, Jim Tinsley, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MIKE ***

MIKE

A PUBLIC SCHOOL STORY

BY

P. G. WODEHOUSE

AUTHOR OF “THE GOLD BAT,” “A PREFECT’S UNCLE,” ETC.

CONTAINING TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS BY

T. M. R. WHITWELL

LONDON

1909

[Dedication]

TO

ALAN DURAND

CONTENTS | |

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | MIKE |

| II. | THE JOURNEY DOWN |

| III. | MIKE FINDS A FRIENDLY NATIVE |

| IV. | AT THE NETS |

| V. | REVELRY BY NIGHT |

| VI. | IN WHICH A TIGHT CORNER IS EVADED |

| VII. | IN WHICH MIKE IS DISCUSSED |

| VIII. | A ROW WITH THE TOWN |

| IX. | BEFORE THE STORM |

| X. | THE GREAT PICNIC |

| XI. | THE CONCLUSION OF THE PICNIC |

| XII. | MIKE GETS HIS CHANCE |

| XIII. | THE M.C.C. MATCH |

| XIV. | A SLIGHT IMBROGLIO |

| XV. | MIKE CREATES A VACANCY |

| XVI. | AN EXPERT EXAMINATION |

| XVII. | ANOTHER VACANCY |

| XVIII. | BOB HAS NEWS TO IMPART |

| XIX. | MIKE GOES TO SLEEP AGAIN |

| XX. | THE TEAM IS FILLED UP |

| XXI. | MARJORY THE FRANK |

| XXII. | WYATT IS REMINDED OF AN ENGAGEMENT |

| XXIII. | A SURPRISE FOR MR. APPLEBY |

| XXIV. | CAUGHT |

| XXV. | MARCHING ORDERS |

| XXVI. | THE AFTERMATH |

| XXVII. | THE RIPTON MATCH |

| XXVIII. | MIKE WINS HOME |

| XXIX. | WYATT AGAIN |

| XXX. | MR. JACKSON MAKES UP HIS MIND |

| XXXI. | SEDLEIGH |

| XXXII. | PSMITH |

| XXXIII. | STAKING OUT A CLAIM |

| XXXIV. | GUERILLA WARFARE |

| XXXV. | UNPLEASANTNESS IN THE SMALL HOURS |

| XXXVI. | ADAIR |

| XXXVII. | MIKE FINDS OCCUPATION |

| XXXVIII. | THE FIRE BRIGADE MEETING |

| XXXIX. | ACHILLES LEAVES HIS TENT |

| XL. | THE MATCH WITH DOWNING’S |

| XLI. | THE SINGULAR BEHAVIOUR OF JELLICOE |

| XLII. | JELLICOE GOES ON THE SICK-LIST |

| XLIII. | MIKE RECEIVES A COMMISSION |

| XLIV. | AND FULFILS IT |

| XLV. | PURSUIT |

| XLVI. | THE DECORATION OF SAMMY |

| XLVII. | MR. DOWNING ON THE SCENT |

| XLVIII. | THE SLEUTH-HOUND |

| XLIX. | A CHECK |

| L. | THE DESTROYER OF EVIDENCE |

| LI. | MAINLY ABOUT BOOTS |

| LII. | ON THE TRAIL AGAIN |

| LIII. | THE KETTLE METHOD |

| LIV. | ADAIR HAS A WORD WITH MIKE |

| LV. | CLEARING THE AIR |

| LVI. | IN WHICH PEACE IS DECLARED |

| LVII. | MR. DOWNING MOVES |

| LVIII. | THE ARTIST CLAIMS HIS WORK |

| LIX. | SEDLEIGH v. WRYKYN |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

BY T. M. R. WHITWELL

* | “ARE YOU THE M. JACKSON, THEN, WHO HAD AN AVERAGE OF FIFTY-ONE POINT NOUGHT THREE LAST YEAR?” |

* | THE DARK WATERS WERE LASHED INTO A MAELSTROM |

* | “DON’T LAUGH, YOU GRINNING APE” |

* | “DO—YOU—SEE, YOU FRIGHTFUL KID?” |

* | “WHAT’S ALL THIS ABOUT JIMMY WYATT?” |

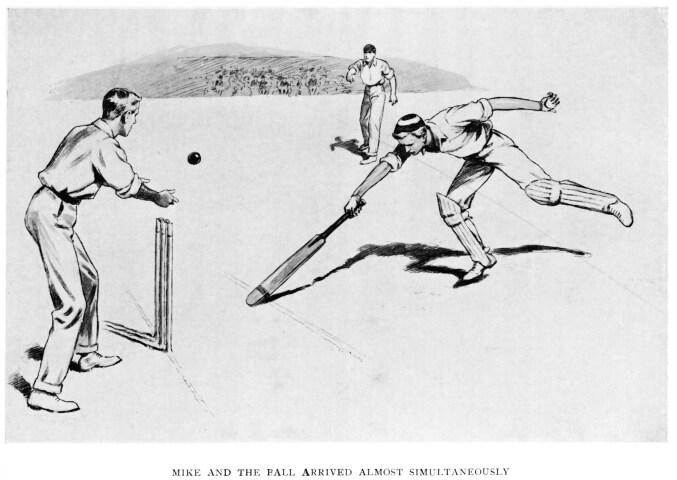

* | MIKE AND THE BALL ARRIVED ALMOST SIMULTANEOUSLY |

* | “WHAT THE DICKENS ARE YOU DOING HERE?” |

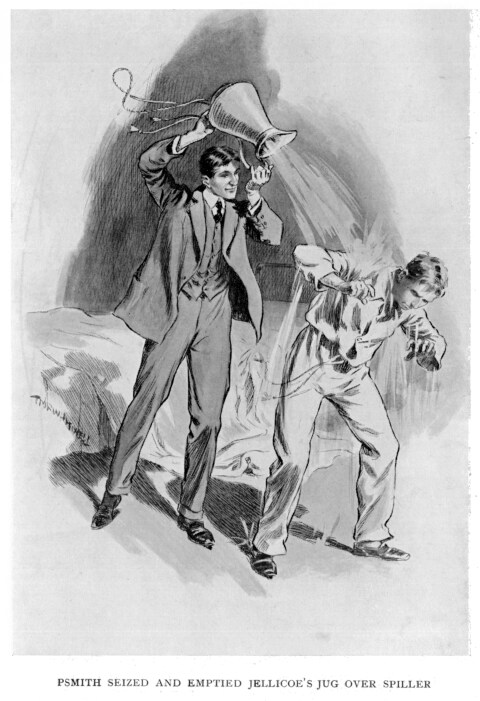

* | PSMITH SEIZED AND EMPTIED JELLICOE’S JUG OVER SPILLER |

* | “WHY DID YOU SAY YOU DIDN’T PLAY CRICKET?” HE ASKED |

* | “WHO—” HE SHOUTED, “WHO HAS DONE THIS?” |

* | “DID—YOU—PUT—THAT—BOOT—THERE, SMITH?” |

* | MIKE DROPPED THE SOOT-COVERED OBJECT IN THE FENDER |

CHAPTER I

MIKE

It was a morning in the middle of

April, and the Jackson family were consequently breakfasting

in comparative silence. The cricket season had

not begun, and except during the cricket season they

were in the habit of devoting their powerful minds

at breakfast almost exclusively to the task of victualling

against the labours of the day. In May, June,

July, and August the silence was broken. The three

grown-up Jacksons played regularly in first-class

cricket, and there was always keen competition among

their brothers and sisters for the copy of the Sportsman

which was to be found on the hall table with the letters.

Whoever got it usually gloated over it in silence till

urged wrathfully by the multitude to let them know

what had happened; when it would appear that Joe had

notched his seventh century, or that Reggie had been

run out when he was just getting set, or, as sometimes

occurred, that that ass Frank had dropped Fry or Hayward

in the slips before he had scored, with the result

that the spared expert had made a couple of hundred

and was still going strong.

In such a case the criticisms of the

family circle, particularly of the smaller Jackson

sisters, were so breezy and unrestrained that Mrs.

Jackson generally felt it necessary to apply the closure.

Indeed, Marjory Jackson, aged fourteen, had on three

several occasions been fined pudding at lunch for

her caustic comments on the batting of her brother

Reggie in important fixtures. Cricket was a tradition

in the family, and the ladies, unable to their sorrow

to play the game themselves, were resolved that it

should not be their fault if the standard was not

kept up.

On this particular morning silence

reigned. A deep gasp from some small Jackson,

wrestling with bread-and-milk, and an occasional remark

from Mr. Jackson on the letters he was reading, alone

broke it.

“Mike’s late again,”

said Mrs. Jackson plaintively, at last.

“He’s getting up,”

said Marjory. “I went in to see what he

was doing, and he was asleep. So,” she

added with a satanic chuckle, “I squeezed a

sponge over him. He swallowed an awful lot, and

then he woke up, and tried to catch me, so he’s

certain to be down soon.”

“Marjory!”

“Well, he was on his back with

his mouth wide open. I had to. He was snoring

like anything.”

“You might have choked him.”

“I did,” said Marjory

with satisfaction. “Jam, please, Phyllis,

you pig.”

Mr. Jackson looked up.

“Mike will have to be more punctual when he

goes to Wrykyn,” he said.

“Oh, father, is Mike going to Wrykyn?”

asked Marjory. “When?”

“Next term,” said Mr.

Jackson. “I’ve just heard from Mr.

Wain,” he added across the table to Mrs. Jackson.

“The house is full, but he is turning a small

room into an extra dormitory, so he can take Mike

after all.”

The first comment on this momentous

piece of news came from Bob Jackson. Bob was

eighteen. The following term would be his last

at Wrykyn, and, having won through so far without

the infliction of a small brother, he disliked the

prospect of not being allowed to finish as he had

begun.

“I say!” he said. “What?”

“He ought to have gone before,”

said Mr. Jackson. “He’s fifteen.

Much too old for that private school. He has

had it all his own way there, and it isn’t good

for him.”

“He’s got cheek enough for ten,”

agreed Bob.

“Wrykyn will do him a world of good.”

“We aren’t in the same house. That’s

one comfort.”

Bob was in Donaldson’s.

It softened the blow to a certain extent that Mike

should be going to Wain’s. He had the same

feeling for Mike that most boys of eighteen have for

their fifteen-year-old brothers. He was fond

of him in the abstract, but preferred him at a distance.

Marjory gave tongue again. She

had rescued the jam from Phyllis, who had shown signs

of finishing it, and was now at liberty to turn her

mind to less pressing matters. Mike was her special

ally, and anything that affected his fortunes affected

her.

“Hooray! Mike’s going

to Wrykyn. I bet he gets into the first eleven

his first term.”

“Considering there are eight

old colours left,” said Bob loftily, “besides

heaps of last year’s seconds, it’s hardly

likely that a kid like Mike’ll get a look in.

He might get his third, if he sweats.”

The aspersion stung Marjory.

“I bet he gets in before you, anyway,”

she said.

Bob disdained to reply. He was

among those heaps of last year’s seconds to

whom he had referred. He was a sound bat, though

lacking the brilliance of his elder brothers, and

he fancied that his cap was a certainty this season.

Last year he had been tried once or twice. This

year it should be all right.

Mrs. Jackson intervened.

“Go on with your breakfast,

Marjory,” she said. “You mustn’t

say ‘I bet’ so much.”

Marjory bit off a section of her slice of bread-and-jam.

“Anyhow, I bet he does,” she muttered

truculently through it.

There was a sound of footsteps in

the passage outside. The door opened, and the

missing member of the family appeared. Mike Jackson

was tall for his age. His figure was thin and

wiry. His arms and legs looked a shade too long

for his body. He was evidently going to be very

tall some day. In face, he was curiously like

his brother Joe, whose appearance is familiar to every

one who takes an interest in first-class cricket.

The resemblance was even more marked on the cricket

field. Mike had Joe’s batting style to the

last detail. He was a pocket edition of his century-making

brother. “Hullo,” he said, “sorry

I’m late.”

This was mere stereo. He had

made the same remark nearly every morning since the

beginning of the holidays.

“All right, Marjory, you little

beast,” was his reference to the sponge incident.

His third remark was of a practical nature.

“I say, what’s under that dish?”

“Mike,” began Mr. Jackson—this

again was stereo—“you really must

learn to be more punctual——”

He was interrupted by a chorus.

“Mike, you’re going to Wrykyn next term,”

shouted Marjory.

“Mike, father’s just had

a letter to say you’re going to Wrykyn next

term.” From Phyllis.

“Mike, you’re going to Wrykyn.”

From Ella.

Gladys Maud Evangeline, aged three,

obliged with a solo of her own composition, in six-eight

time, as follows: “Mike Wryky. Mike

Wryky. Mike Wryke Wryke Wryke Mike Wryke Wryke

Mike Wryke Mike Wryke.”

“Oh, put a green baize cloth over that kid,

somebody,” groaned Bob.

Whereat Gladys Maud, having fixed

him with a chilly stare for some seconds, suddenly

drew a long breath, and squealed deafeningly for more

milk.

Mike looked round the table.

It was a great moment. He rose to it with the

utmost dignity.

“Good,” he said. “I say, what’s

under that dish?”

After breakfast, Mike and Marjory

went off together to the meadow at the end of the

garden. Saunders, the professional, assisted by

the gardener’s boy, was engaged in putting up

the net. Mr. Jackson believed in private coaching;

and every spring since Joe, the eldest of the family,

had been able to use a bat a man had come down from

the Oval to teach him the best way to do so.

Each of the boys in turn had passed from spectators

to active participants in the net practice in the

meadow. For several years now Saunders had been

the chosen man, and his attitude towards the Jacksons

was that of the Faithful Old Retainer in melodrama.

Mike was his special favourite. He felt that in

him he had material of the finest order to work upon.

There was nothing the matter with Bob. In Bob

he would turn out a good, sound article. Bob

would be a Blue in his third or fourth year, and probably

a creditable performer among the rank and file of a

county team later on. But he was not a cricket

genius, like Mike. Saunders would lie awake at

night sometimes thinking of the possibilities that

were in Mike. The strength could only come with

years, but the style was there already. Joe’s

style, with improvements.

Mike put on his pads; and Marjory

walked with the professional to the bowling crease.

“Mike’s going to Wrykyn

next term, Saunders,” she said. “All

the boys were there, you know. So was father,

ages ago.”

“Is he, miss? I was thinking he would be

soon.”

“Do you think he’ll get into the school

team?”

“School team, miss! Master

Mike get into a school team! He’ll be playing

for England in another eight years. That’s

what he’ll be playing for.”

“Yes, but I meant next term.

It would be a record if he did. Even Joe only

got in after he’d been at school two years.

Don’t you think he might, Saunders? He’s

awfully good, isn’t he? He’s better

than Bob, isn’t he? And Bob’s almost

certain to get in this term.”

Saunders looked a little doubtful.

“Next term!” he said. “Well, you see, miss, it’s this way. It’s all there, in a

manner of speaking, with Master Mike. He’s got as much style as Mr. Joe’s got,

every bit. The whole thing is, you see, miss, you get these young gentlemen of

eighteen, and nineteen perhaps, and it stands to reason they’re stronger.

There’s a young gentleman, perhaps, doesn’t know as much about what I call real

playing as Master Mike’s forgotten; but then he can hit ’em harder when he does

hit ’em, and that’s where the runs come in. They aren’t going to play Master

Mike because he’ll be in the England team when he leaves school. They’ll give

the cap to somebody that can make a few then and there.”

“But Mike’s jolly strong.”

“Ah, I’m not saying it

mightn’t be, miss. I was only saying don’t

count on it, so you won’t be disappointed if

it doesn’t happen. It’s quite likely

that it will, only all I say is don’t count on

it. I only hope that they won’t knock all

the style out of him before they’re done with

him. You know these school professionals, miss.”

“No, I don’t, Saunders. What are

they like?”

“Well, there’s too much

of the come-right-out-at-everything about ’em

for my taste. Seem to think playing forward the

alpha and omugger of batting. They’ll make

him pat balls back to the bowler which he’d cut

for twos and threes if he was left to himself.

Still, we’ll hope for the best, miss. Ready,

Master Mike? Play.”

As Saunders had said, it was all there.

Of Mike’s style there could be no doubt.

To-day, too, he was playing more strongly than usual.

Marjory had to run to the end of the meadow to fetch

one straight drive. “He hit that hard enough,

didn’t he, Saunders?” she asked, as she

returned the ball.

“If he could keep on doing ones

like that, miss,” said the professional, “they’d

have him in the team before you could say knife.”

Marjory sat down again beside the

net, and watched more hopefully.

CHAPTER II

THE JOURNEY DOWN

The seeing off of Mike on the last

day of the holidays was an imposing spectacle, a sort

of pageant. Going to a public school, especially

at the beginning of the summer term, is no great hardship,

more particularly when the departing hero has a brother

on the verge of the school eleven and three other

brothers playing for counties; and Mike seemed in

no way disturbed by the prospect. Mothers, however,

to the end of time will foster a secret fear that

their sons will be bullied at a big school, and Mrs.

Jackson’s anxious look lent a fine solemnity

to the proceedings.

And as Marjory, Phyllis, and Ella

invariably broke down when the time of separation

arrived, and made no exception to their rule on the

present occasion, a suitable gloom was the keynote

of the gathering. Mr. Jackson seemed to bear

the parting with fortitude, as did Mike’s Uncle

John (providentially roped in at the eleventh hour

on his way to Scotland, in time to come down with

a handsome tip). To their coarse-fibred minds

there was nothing pathetic or tragic about the affair

at all. (At the very moment when the train began to

glide out of the station Uncle John was heard to remark

that, in his opinion, these Bocks weren’t a

patch on the old shaped Larranaga.) Among others present

might have been noticed Saunders, practising late cuts

rather coyly with a walking-stick in the background;

the village idiot, who had rolled up on the chance

of a dole; Gladys Maud Evangeline’s nurse, smiling

vaguely; and Gladys Maud Evangeline herself, frankly

bored with the whole business.

The train gathered speed. The

air was full of last messages. Uncle John said

on second thoughts he wasn’t sure these Bocks

weren’t half a bad smoke after all. Gladys

Maud cried, because she had taken a sudden dislike

to the village idiot; and Mike settled himself in the

corner and opened a magazine.

He was alone in the carriage.

Bob, who had been spending the last week of the holidays

with an aunt further down the line, was to board the

train at East Wobsley, and the brothers were to make

a state entry into Wrykyn together. Meanwhile,

Mike was left to his milk chocolate, his magazines,

and his reflections.

The latter were not numerous, nor

profound. He was excited. He had been petitioning

the home authorities for the past year to be allowed

to leave his private school and go to Wrykyn, and now

the thing had come about. He wondered what sort

of a house Wain’s was, and whether they had

any chance of the cricket cup. According to Bob

they had no earthly; but then Bob only recognised

one house, Donaldson’s. He wondered if

Bob would get his first eleven cap this year, and if

he himself were likely to do anything at cricket.

Marjory had faithfully reported every word Saunders

had said on the subject, but Bob had been so careful

to point out his insignificance when compared with

the humblest Wrykynian that the professional’s

glowing prophecies had not had much effect. It

might be true that some day he would play for England,

but just at present he felt he would exchange his place

in the team for one in the Wrykyn third eleven.

A sort of mist enveloped everything Wrykynian.

It seemed almost hopeless to try and compete with

these unknown experts. On the other hand, there

was Bob. Bob, by all accounts, was on the verge

of the first eleven, and he was nothing special.

While he was engaged on these reflections,

the train drew up at a small station. Opposite

the door of Mike’s compartment was standing a

boy of about Mike’s size, though evidently some

years older. He had a sharp face, with rather

a prominent nose; and a pair of pince-nez gave him

a supercilious look. He wore a bowler hat, and

carried a small portmanteau.

He opened the door, and took the seat

opposite to Mike, whom he scrutinised for a moment

rather after the fashion of a naturalist examining

some new and unpleasant variety of beetle. He

seemed about to make some remark, but, instead, got

up and looked through the open window.

“Where’s that porter?” Mike heard

him say.

The porter came skimming down the platform at that

moment.

“Porter.”

“Sir?”

“Are those frightful boxes of mine in all right?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Because, you know, there’ll

be a frightful row if any of them get lost.”

“No chance of that, sir.”

“Here you are, then.”

“Thank you, sir.”

The youth drew his head and shoulders

in, stared at Mike again, and finally sat down.

Mike noticed that he had nothing to read, and wondered

if he wanted anything; but he did not feel equal to

offering him one of his magazines. He did not

like the looks of him particularly. Judging by

appearances, he seemed to carry enough side for three.

If he wanted a magazine, thought Mike, let him ask

for it.

The other made no overtures, and at

the next stop got out. That explained his magazineless

condition. He was only travelling a short way.

“Good business,” said

Mike to himself. He had all the Englishman’s

love of a carriage to himself.

The train was just moving out of the

station when his eye was suddenly caught by the stranger’s

bag, lying snugly in the rack.

And here, I regret to say, Mike acted

from the best motives, which is always fatal.

He realised in an instant what had

happened. The fellow had forgotten his bag.

Mike had not been greatly fascinated

by the stranger’s looks; but, after all, the

most supercilious person on earth has a right to his

own property. Besides, he might have been quite

a nice fellow when you got to know him. Anyhow,

the bag had better be returned at once. The train

was already moving quite fast, and Mike’s compartment

was nearing the end of the platform.

He snatched the bag from the rack

and hurled it out of the window. (Porter Robinson,

who happened to be in the line of fire, escaped with

a flesh wound.) Then he sat down again with the inward

glow of satisfaction which comes to one when one has

risen successfully to a sudden emergency.

The glow lasted till the next stoppage,

which did not occur for a good many miles. Then

it ceased abruptly, for the train had scarcely come

to a standstill when the opening above the door was

darkened by a head and shoulders. The head was

surmounted by a bowler, and a pair of pince-nez gleamed

from the shadow.

“Hullo, I say,” said the

stranger. “Have you changed carriages, or

what?”

“No,” said Mike.

“Then, dash it, where’s my frightful bag?”

Life teems with embarrassing situations. This

was one of them.

“The fact is,” said Mike, “I chucked

it out.”

“Chucked it out! what do you mean? When?”

“At the last station.”

The guard blew his whistle, and the other jumped into

the carriage.

“I thought you’d got out

there for good,” explained Mike. “I’m

awfully sorry.”

“Where is the bag?”

“On the platform at the last station. It

hit a porter.”

Against his will, for he wished to

treat the matter with fitting solemnity, Mike grinned

at the recollection. The look on Porter Robinson’s

face as the bag took him in the small of the back had

been funny, though not intentionally so.

The bereaved owner disapproved of this levity; and

said as much.

“Don’t grin, you

little beast,” he shouted. “There’s

nothing to laugh at. You go chucking bags that

don’t belong to you out of the window, and then

you have the frightful cheek to grin about it.”

“It wasn’t that,”

said Mike hurriedly. “Only the porter looked

awfully funny when it hit him.”

“Dash the porter! What’s

going to happen about my bag? I can’t get

out for half a second to buy a magazine without your

flinging my things about the platform. What you

want is a frightful kicking.”

The situation was becoming difficult.

But fortunately at this moment the train stopped once

again; and, looking out of the window, Mike saw a

board with East Wobsley upon it in large letters.

A moment later Bob’s head appeared in the doorway.

“Hullo, there you are,” said Bob.

His eye fell upon Mike’s companion.

“Hullo, Gazeka!” he exclaimed.

“Where did you spring from? Do you know

my brother? He’s coming to Wrykyn this term.

By the way, rather lucky you’ve met. He’s

in your house. Firby-Smith’s head of Wain’s,

Mike.”

Mike gathered that Gazeka and Firby-Smith

were one and the same person. He grinned again.

Firby-Smith continued to look ruffled, though not

aggressive.

“Oh, are you in Wain’s?” he said.

“I say, Bob,” said Mike, “I’ve

made rather an ass of myself.”

“Naturally.”

“I mean, what happened was this.

I chucked Firby-Smith’s portmanteau out of the

window, thinking he’d got out, only he hadn’t

really, and it’s at a station miles back.”

“You’re a bit of a rotter,

aren’t you? Had it got your name and address

on it, Gazeka?”

“Yes.”

“Oh, then it’s certain

to be all right. It’s bound to turn up some

time. They’ll send it on by the next train,

and you’ll get it either to-night or to-morrow.”

“Frightful nuisance, all the

same. Lots of things in it I wanted.”

“Oh, never mind, it’s

all right. I say, what have you been doing in

the holidays? I didn’t know you lived on

this line at all.”

From this point onwards Mike was out

of the conversation altogether. Bob and Firby-Smith

talked of Wrykyn, discussing events of the previous

term of which Mike had never heard. Names came

into their conversation which were entirely new to

him. He realised that school politics were being

talked, and that contributions from him to the dialogue

were not required. He took up his magazine again,

listening the while. They were discussing Wain’s

now. The name Wyatt cropped up with some frequency.

Wyatt was apparently something of a character.

Mention was made of rows in which he had played a part

in the past.

“It must be pretty rotten for

him,” said Bob. “He and Wain never

get on very well, and yet they have to be together,

holidays as well as term. Pretty bad having a

step-father at all—I shouldn’t care

to—and when your house-master and your

step-father are the same man, it’s a bit thick.”

“Frightful,” agreed Firby-Smith.

“I swear, if I were in Wyatt’s

place, I should rot about like anything. It isn’t

as if he’d anything to look forward to when he

leaves. He told me last term that Wain had got

a nomination for him in some beastly bank, and that

he was going into it directly after the end of this

term. Rather rough on a chap like Wyatt.

Good cricketer and footballer, I mean, and all that

sort of thing. It’s just the sort of life

he’ll hate most. Hullo, here we are.”

Mike looked out of the window. It was Wrykyn

at last.

CHAPTER III

MIKE FINDS A FRIENDLY NATIVE

Mike was surprised to find, on alighting,

that the platform was entirely free from Wrykynians.

In all the stories he had read the whole school came

back by the same train, and, having smashed in one

another’s hats and chaffed the porters, made

their way to the school buildings in a solid column.

But here they were alone.

A remark of Bob’s to Firby-Smith

explained this. “Can’t make out why

none of the fellows came back by this train,”

he said. “Heaps of them must come by this

line, and it’s the only Christian train they

run,”

“Don’t want to get here

before the last minute they can possibly manage.

Silly idea. I suppose they think there’d

be nothing to do.”

“What shall we do?”

said Bob. “Come and have some tea at Cook’s?”

“All right.”

Bob looked at Mike. There was

no disguising the fact that he would be in the way;

but how convey this fact delicately to him?

“Look here, Mike,” he

said, with a happy inspiration, “Firby-Smith

and I are just going to get some tea. I think

you’d better nip up to the school. Probably

Wain will want to see you, and tell you all about

things, which is your dorm. and so on. See you

later,” he concluded airily. “Any

one’ll tell you the way to the school. Go

straight on. They’ll send your luggage

on later. So long.” And his sole prop

in this world of strangers departed, leaving him to

find his way for himself.

There is no subject on which opinions

differ so widely as this matter of finding the way

to a place. To the man who knows, it is simplicity

itself. Probably he really does imagine that he

goes straight on, ignoring the fact that for him the

choice of three roads, all more or less straight,

has no perplexities. The man who does not know

feels as if he were in a maze.

Mike started out boldly, and lost

his way. Go in which direction he would, he always

seemed to arrive at a square with a fountain and an

equestrian statue in its centre. On the fourth

repetition of this feat he stopped in a disheartened

way, and looked about him. He was beginning to

feel bitter towards Bob. The man might at least

have shown him where to get some tea.

At this moment a ray of hope shone

through the gloom. Crossing the square was a

short, thick-set figure clad in grey flannel trousers,

a blue blazer, and a straw hat with a coloured band.

Plainly a Wrykynian. Mike made for him.

“Can you tell me the way to

the school, please,” he said.

“Oh, you’re going to the

school,” said the other. He had a pleasant,

square-jawed face, reminiscent of a good-tempered bull-dog,

and a pair of very deep-set grey eyes which somehow

put Mike at his ease. There was something singularly

cool and genial about them. He felt that they

saw the humour in things, and that their owner was

a person who liked most people and whom most people

liked.

“You look rather lost,”

said the stranger. “Been hunting for it

long?”

“Yes,” said Mike.

“Which house do you want?”

“Wain’s.”

“Wain’s? Then you’ve

come to the right man this time. What I don’t

know about Wain’s isn’t worth knowing.”

“Are you there, too?”

“Am I not! Term and holidays.

There’s no close season for me.”

“Oh, are you Wyatt, then?” asked Mike.

“Hullo, this is fame. How

did you know my name, as the ass in the detective

story always says to the detective, who’s seen

it in the lining of his hat? Who’s been

talking about me?”

“I heard my brother saying something about you

in the train.”

“Who’s your brother?”

“Jackson. He’s in Donaldson’s.”

“I know. A stout fellow.

So you’re the newest make of Jackson, latest

model, with all the modern improvements? Are there

any more of you?”

“Not brothers,” said Mike.

“Pity. You can’t

quite raise a team, then? Are you a sort of young

Tyldesley, too?”

“I played a bit at my last school.

Only a private school, you know,” added Mike

modestly.

“Make any runs? What was your best score?”

“Hundred and twenty-three,”

said Mike awkwardly. “It was only against

kids, you know.” He was in terror lest he

should seem to be bragging.

“That’s pretty useful. Any more centuries?”

“Yes,” said Mike, shuffling.

“How many?”

“Seven altogether. You

know, it was really awfully rotten bowling. And

I was a good bit bigger than most of the chaps there.

And my pater always has a pro. down in the Easter

holidays, which gave me a bit of an advantage.”

“All the same, seven centuries

isn’t so dusty against any bowling. We

shall want some batting in the house this term.

Look here, I was just going to have some tea.

You come along, too.”

“Oh, thanks awfully,”

said Mike. “My brother and Firby-Smith have

gone to a place called Cook’s.”

“The old Gazeka? I didn’t

know he lived in your part of the world. He’s

head of Wain’s.”

“Yes, I know,” said Mike.

“Why is he called Gazeka?” he asked after

a pause.

“Don’t you think he looks

like one? What did you think of him?”

“I didn’t speak to him

much,” said Mike cautiously. It is always

delicate work answering a question like this unless

one has some sort of an inkling as to the views of

the questioner.

“He’s all right,”

said Wyatt, answering for himself. “He’s

got a habit of talking to one as if he were a prince

of the blood dropping a gracious word to one of the

three Small-Heads at the Hippodrome, but that’s

his misfortune. We all have our troubles.

That’s his. Let’s go in here.

It’s too far to sweat to Cook’s.”

It was about a mile from the tea-shop

to the school. Mike’s first impression

on arriving at the school grounds was of his smallness

and insignificance. Everything looked so big—the

buildings, the grounds, everything. He felt out

of the picture. He was glad that he had met Wyatt.

To make his entrance into this strange land alone would

have been more of an ordeal than he would have cared

to face.

“That’s Wain’s,”

said Wyatt, pointing to one of half a dozen large

houses which lined the road on the south side of the

cricket field. Mike followed his finger, and

took in the size of his new home.

“I say, it’s jolly big,”

he said. “How many fellows are there in

it?”

“Thirty-one this term, I believe.”

“That’s more than there were at King-Hall’s.”

“What’s King-Hall’s?”

“The private school I was at. At Emsworth.”

Emsworth seemed very remote and unreal to him as he

spoke.

They skirted the cricket field, walking

along the path that divided the two terraces.

The Wrykyn playing-fields were formed of a series of

huge steps, cut out of the hill. At the top of

the hill came the school. On the first terrace

was a sort of informal practice ground, where, though

no games were played on it, there was a good deal of

punting and drop-kicking in the winter and fielding-practice

in the summer. The next terrace was the biggest

of all, and formed the first eleven cricket ground,

a beautiful piece of turf, a shade too narrow for

its length, bounded on the terrace side by a sharply

sloping bank, some fifteen feet deep, and on the other

by the precipice leading to the next terrace.

At the far end of the ground stood the pavilion, and

beside it a little ivy-covered rabbit-hutch for the

scorers. Old Wrykynians always claimed that it

was the prettiest school ground in England. It

certainly had the finest view. From the verandah

of the pavilion you could look over three counties.

Wain’s house wore an empty and

desolate appearance. There were signs of activity,

however, inside; and a smell of soap and warm water

told of preparations recently completed.

Wyatt took Mike into the matron’s

room, a small room opening out of the main passage.

“This is Jackson,” he

said. “Which dormitory is he in, Miss Payne?”

The matron consulted a paper.

“He’s in yours, Wyatt.”

“Good business. Who’s

in the other bed? There are going to be three

of us, aren’t there?”

“Fereira was to have slept there,

but we have just heard that he is not coming back

this term. He has had to go on a sea-voyage for

his health.”

“Seems queer any one actually

taking the trouble to keep Fereira in the world,”

said Wyatt. “I’ve often thought of

giving him Rough On Rats myself. Come along,

Jackson, and I’ll show you the room.”

They went along the passage, and up a flight of stairs.

“Here you are,” said Wyatt.

It was a fair-sized room. The

window, heavily barred, looked out over a large garden.

“I used to sleep here alone

last term,” said Wyatt, “but the house

is so full now they’ve turned it into a dormitory.”

“I say, I wish these bars weren’t

here. It would be rather a rag to get out of

the window on to that wall at night, and hop down into

the garden and explore,” said Mike.

Wyatt looked at him curiously, and moved to the window.

“I’m not going to let

you do it, of course,” he said, “because

you’d go getting caught, and dropped on, which

isn’t good for one in one’s first term;

but just to amuse you——”

He jerked at the middle bar, and the

next moment he was standing with it in his hand, and

the way to the garden was clear.

“By Jove!” said Mike.

“That’s simply an object-lesson,

you know,” said Wyatt, replacing the bar, and

pushing the screws back into their putty. “I

get out at night myself because I think my health

needs it. Besides, it’s my last term, anyhow,

so it doesn’t matter what I do. But if I

find you trying to cut out in the small hours, there’ll

be trouble. See?”

“All right,” said Mike,

reluctantly. “But I wish you’d let

me.”

“Not if I know it. Promise you won’t

try it on.”

“All right. But, I say, what do you do

out there?”

“I shoot at cats with an air-pistol,

the beauty of which is that even if you hit them it

doesn’t hurt—simply keeps them bright

and interested in life; and if you miss you’ve

had all the fun anyhow. Have you ever shot at

a rocketing cat? Finest mark you can have.

Society’s latest craze. Buy a pistol and

see life.”

“I wish you’d let me come.”

“I daresay you do. Not

much, however. Now, if you like, I’ll take

you over the rest of the school. You’ll

have to see it sooner or later, so you may as well

get it over at once.”

CHAPTER IV

AT THE NETS

There are few better things in life

than a public school summer term. The winter

term is good, especially towards the end, and there

are points, though not many, about the Easter term:

but it is in the summer that one really appreciates

public school life. The freedom of it, after

the restrictions of even the most easy-going private

school, is intoxicating. The change is almost

as great as that from public school to ’Varsity.

For Mike the path was made particularly

easy. The only drawback to going to a big school

for the first time is the fact that one is made to

feel so very small and inconspicuous. New boys

who have been leading lights at their private schools

feel it acutely for the first week. At one time

it was the custom, if we may believe writers of a

generation or so back, for boys to take quite an embarrassing

interest in the newcomer. He was asked a rain

of questions, and was, generally, in the very centre

of the stage. Nowadays an absolute lack of interest

is the fashion. A new boy arrives, and there he

is, one of a crowd.

Mike was saved this salutary treatment

to a large extent, at first by virtue of the greatness

of his family, and, later, by his own performances

on the cricket field. His three elder brothers

were objects of veneration to most Wrykynians, and

Mike got a certain amount of reflected glory from

them. The brother of first-class cricketers has

a dignity of his own. Then Bob was a help.

He was on the verge of the cricket team and had been

the school full-back for two seasons. Mike found

that people came up and spoke to him, anxious to know

if he were Jackson’s brother; and became friendly

when he replied in the affirmative. Influential

relations are a help in every stage of life.

It was Wyatt who gave him his first

chance at cricket. There were nets on the first

afternoon of term for all old colours of the three

teams and a dozen or so of those most likely to fill

the vacant places. Wyatt was there, of course.

He had got his first eleven cap in the previous season

as a mighty hitter and a fair slow bowler. Mike

met him crossing the field with his cricket bag.

“Hullo, where are you off to?”

asked Wyatt. “Coming to watch the nets?”

Mike had no particular programme for

the afternoon. Junior cricket had not begun,

and it was a little difficult to know how to fill in

the time.

“I tell you what,” said

Wyatt, “nip into the house and shove on some

things, and I’ll try and get Burgess to let you

have a knock later on.”

This suited Mike admirably. A

quarter of an hour later he was sitting at the back

of the first eleven net, watching the practice.

Burgess, the captain of the Wrykyn

team, made no pretence of being a bat. He was

the school fast bowler and concentrated his energies

on that department of the game. He sometimes

took ten minutes at the wicket after everybody else

had had an innings, but it was to bowl that he came

to the nets.

He was bowling now to one of the old

colours whose name Mike did not know. Wyatt and

one of the professionals were the other two bowlers.

Two nets away Firby-Smith, who had changed his pince-nez

for a pair of huge spectacles, was performing rather

ineffectively against some very bad bowling.

Mike fixed his attention on the first eleven man.

He was evidently a good bat.

There was style and power in his batting. He

had a way of gliding Burgess’s fastest to leg

which Mike admired greatly. He was succeeded

at the end of a quarter of an hour by another eleven

man, and then Bob appeared.

It was soon made evident that this

was not Bob’s day. Nobody is at his best

on the first day of term; but Bob was worse than he

had any right to be. He scratched forward at

nearly everything, and when Burgess, who had been

resting, took up the ball again, he had each stump

uprooted in a regular series in seven balls. Once

he skied one of Wyatt’s slows over the net behind

the wicket; and Mike, jumping up, caught him neatly.

“Thanks,” said Bob austerely,

as Mike returned the ball to him. He seemed depressed.

Towards the end of the afternoon,

Wyatt went up to Burgess.

“Burgess,” he said, “see

that kid sitting behind the net?”

“With the naked eye,” said Burgess.

“Why?”

“He’s just come to Wain’s.

He’s Bob Jackson’s brother, and I’ve

a sort of idea that he’s a bit of a bat.

I told him I’d ask you if he could have a knock.

Why not send him in at the end net? There’s

nobody there now.”

Burgess’s amiability off the

field equalled his ruthlessness when bowling.

“All right,” he said.

“Only if you think that I’m going to sweat

to bowl to him, you’re making a fatal error.”

“You needn’t do a thing.

Just sit and watch. I rather fancy this kid’s

something special.”

Mike put on Wyatt’s pads and

gloves, borrowed his bat, and walked round into the

net.

“Not in a funk, are you?” asked Wyatt,

as he passed.

Mike grinned. The fact was that

he had far too good an opinion of himself to be nervous.

An entirely modest person seldom makes a good batsman.

Batting is one of those things which demand first and

foremost a thorough belief in oneself. It need

not be aggressive, but it must be there.

Wyatt and the professional were the

bowlers. Mike had seen enough of Wyatt’s

bowling to know that it was merely ordinary “slow

tosh,” and the professional did not look as

difficult as Saunders. The first half-dozen balls

he played carefully. He was on trial, and he meant

to take no risks. Then the professional over-pitched

one slightly on the off. Mike jumped out, and

got the full face of the bat on to it. The ball

hit one of the ropes of the net, and nearly broke it.

“How’s that?” said

Wyatt, with the smile of an impresario on the first

night of a successful piece.

“Not bad,” admitted Burgess.

A few moments later he was still more

complimentary. He got up and took a ball himself.

Mike braced himself up as Burgess

began his run. This time he was more than a trifle

nervous. The bowling he had had so far had been

tame. This would be the real ordeal.

As the ball left Burgess’s hand

he began instinctively to shape for a forward stroke.

Then suddenly he realised that the thing was going

to be a yorker, and banged his bat down in the block

just as the ball arrived. An unpleasant sensation

as of having been struck by a thunderbolt was succeeded

by a feeling of relief that he had kept the ball out

of his wicket. There are easier things in the

world than stopping a fast yorker.

“Well played,” said Burgess.

Mike felt like a successful general

receiving the thanks of the nation.

The fact that Burgess’s next

ball knocked middle and off stumps out of the ground

saddened him somewhat; but this was the last tragedy

that occurred. He could not do much with the

bowling beyond stopping it and feeling repetitions

of the thunderbolt experience, but he kept up his

end; and a short conversation which he had with Burgess

at the end of his innings was full of encouragement

to one skilled in reading between the lines.

“Thanks awfully,” said

Mike, referring to the square manner in which the

captain had behaved in letting him bat.

“What school were you at before

you came here?” asked Burgess.

“A private school in Hampshire,”

said Mike. “King-Hall’s. At a

place called Emsworth.”

“Get much cricket there?”

“Yes, a good lot. One of

the masters, a chap called Westbrook, was an awfully

good slow bowler.”

Burgess nodded.

“You don’t run away, which is something,”

he said.

Mike turned purple with pleasure at

this stately compliment. Then, having waited

for further remarks, but gathering from the captain’s

silence that the audience was at an end, he proceeded

to unbuckle his pads. Wyatt overtook him on his

way to the house.

“Well played,” he said.

“I’d no idea you were such hot stuff.

You’re a regular pro.”

“I say,” said Mike gratefully,

“it was most awfully decent of you getting Burgess

to let me go in. It was simply ripping of you.”

“Oh, that’s all right.

If you don’t get pushed a bit here you stay for

ages in the hundredth game with the cripples and the

kids. Now you’ve shown them what you can

do you ought to get into the Under Sixteen team straight

away. Probably into the third, too.”

“By Jove, that would be all right.”

“I asked Burgess afterwards

what he thought of your batting, and he said, ‘Not

bad.’ But he says that about everything.

It’s his highest form of praise. He says

it when he wants to let himself go and simply butter

up a thing. If you took him to see N. A. Knox

bowl, he’d say he wasn’t bad. What

he meant was that he was jolly struck with your batting,

and is going to play you for the Under Sixteen.”

“I hope so,” said Mike.

The prophecy was fulfilled. On

the following Wednesday there was a match between

the Under Sixteen and a scratch side. Mike’s

name was among the Under Sixteen. And on the

Saturday he was playing for the third eleven in a

trial game.

“This place is ripping,”

he said to himself, as he saw his name on the list.

“Thought I should like it.”

And that night he wrote a letter to

his father, notifying him of the fact.

CHAPTER V

REVELRY BY NIGHT

A succession of events combined to

upset Mike during his first fortnight at school.

He was far more successful than he had any right to

be at his age. There is nothing more heady than

success, and if it comes before we are prepared for

it, it is apt to throw us off our balance. As

a rule, at school, years of wholesome obscurity make

us ready for any small triumphs we may achieve at

the end of our time there. Mike had skipped these

years. He was older than the average new boy,

and his batting was undeniable. He knew quite

well that he was regarded as a find by the cricket

authorities; and the knowledge was not particularly

good for him. It did not make him conceited, for

his was not a nature at all addicted to conceit.

The effect it had on him was to make him excessively

pleased with life. And when Mike was pleased

with life he always found a difficulty in obeying Authority

and its rules. His state of mind was not improved

by an interview with Bob.

Some evil genius put it into Bob’s

mind that it was his duty to be, if only for one performance,

the Heavy Elder Brother to Mike; to give him good

advice. It is never the smallest use for an elder

brother to attempt to do anything for the good of

a younger brother at school, for the latter rebels

automatically against such interference in his concerns;

but Bob did not know this. He only knew that he

had received a letter from home, in which his mother

had assumed without evidence that he was leading Mike

by the hand round the pitfalls of life at Wrykyn;

and his conscience smote him. Beyond asking him

occasionally, when they met, how he was getting on

(a question to which Mike invariably replied, “Oh,

all right”), he was not aware of having done anything

brotherly towards the youngster. So he asked Mike

to tea in his study one afternoon before going to

the nets.

Mike arrived, sidling into the study

in the half-sheepish, half-defiant manner peculiar

to small brothers in the presence of their elders,

and stared in silence at the photographs on the walls.

Bob was changing into his cricket things. The

atmosphere was one of constraint and awkwardness.

The arrival of tea was the cue for conversation.

“Well, how are you getting on?” asked

Bob.

“Oh, all right,” said Mike.

Silence.

“Sugar?” asked Bob.

“Thanks,” said Mike.

“How many lumps?”

“Two, please.”

“Cake?”

“Thanks.”

Silence.

Bob pulled himself together.

“Like Wain’s?”

“Ripping.”

“I asked Firby-Smith to keep an eye on you,”

said Bob.

“What!” said Mike.

The mere idea of a worm like the Gazeka

being told to keep an eye on him was degrading.

“He said he’d look after you,” added

Bob, making things worse.

Look after him! Him!! M. Jackson, of the

third eleven!!!

Mike helped himself to another chunk of cake, and

spoke crushingly.

“He needn’t trouble,”

he said. “I can look after myself all right,

thanks.”

Bob saw an opening for the entry of the Heavy Elder

Brother.

“Look here, Mike,” he said, “I’m

only saying it for your good——”

I should like to state here that it

was not Bob’s habit to go about the world telling

people things solely for their good. He was only

doing it now to ease his conscience.

“Yes?” said Mike coldly.

“It’s only this.

You know, I should keep an eye on myself if I were

you. There’s nothing that gets a chap so

barred here as side.”

“What do you mean?” said Mike, outraged.

“Oh, I’m not saying anything

against you so far,” said Bob. “You’ve

been all right up to now. What I mean to say is,

you’ve got on so well at cricket, in the third

and so on, there’s just a chance you might start

to side about a bit soon, if you don’t watch

yourself. I’m not saying a word against

you so far, of course. Only you see what I mean.”

Mike’s feelings were too deep

for words. In sombre silence he reached out for

the jam; while Bob, satisfied that he had delivered

his message in a pleasant and tactful manner, filled

his cup, and cast about him for further words of wisdom.

“Seen you about with Wyatt a

good deal,” he said at length.

“Yes,” said Mike.

“Like him?”

“Yes,” said Mike cautiously.

“You know,” said Bob,

“I shouldn’t—I mean, I should

take care what you’re doing with Wyatt.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, he’s an awfully good chap, of course,

but still——”

“Still what?”

“Well, I mean, he’s the

sort of chap who’ll probably get into some thundering

row before he leaves. He doesn’t care a

hang what he does. He’s that sort of chap.

He’s never been dropped on yet, but if you go

on breaking rules you’re bound to be sooner or

later. Thing is, it doesn’t matter much

for him, because he’s leaving at the end of the

term. But don’t let him drag you into anything.

Not that he would try to. But you might think

it was the blood thing to do to imitate him, and the

first thing you knew you’d be dropped on by Wain

or somebody. See what I mean?”

Bob was well-intentioned, but tact

did not enter greatly into his composition.

“What rot!” said Mike.

“All right. But don’t

you go doing it. I’m going over to the nets.

I see Burgess has shoved you down for them. You’d

better be going and changing. Stick on here a

bit, though, if you want any more tea. I’ve

got to be off myself.”

Mike changed for net-practice in a

ferment of spiritual injury. It was maddening

to be treated as an infant who had to be looked after.

He felt very sore against Bob.

A good innings at the third eleven

net, followed by some strenuous fielding in the deep,

soothed his ruffled feelings to a large extent; and

all might have been well but for the intervention of

Firby-Smith.

That youth, all spectacles and front

teeth, met Mike at the door of Wain’s.

“Ah, I wanted to see you, young

man,” he said. (Mike disliked being called “young

man.”) “Come up to my study.”

Mike followed him in silence to his

study, and preserved his silence till Firby-Smith,

having deposited his cricket-bag in a corner of the

room and examined himself carefully in a looking-glass

that hung over the mantelpiece, spoke again.

“I’ve been hearing all

about you, young man.” Mike shuffled.

“You’re a frightful character

from all accounts.” Mike could not think

of anything to say that was not rude, so said nothing.

“Your brother has asked me to keep an eye on

you.”

Mike’s soul began to tie itself

into knots again. He was just at the age when

one is most sensitive to patronage and most resentful

of it.

“I promised I would,”

said the Gazeka, turning round and examining himself

in the mirror again. “You’ll get on

all right if you behave yourself. Don’t

make a frightful row in the house. Don’t

cheek your elders and betters. Wash. That’s

all. Cut along.”

Mike had a vague idea of sacrificing

his career to the momentary pleasure of flinging a

chair at the head of the house. Overcoming this

feeling, he walked out of the room, and up to his dormitory

to change.

In the dormitory that night the feeling

of revolt, of wanting to do something actively illegal,

increased. Like Eric, he burned, not with shame

and remorse, but with rage and all that sort of thing.

He dropped off to sleep full of half-formed plans for

asserting himself. He was awakened from a dream

in which he was batting against Firby-Smith’s

bowling, and hitting it into space every time, by a

slight sound. He opened his eyes, and saw a dark

figure silhouetted against the light of the window.

He sat up in bed.

“Hullo,” he said. “Is that

you, Wyatt?”

“Are you awake?” said

Wyatt. “Sorry if I’ve spoiled your

beauty sleep.”

“Are you going out?”

“I am,” said Wyatt.

“The cats are particularly strong on the wing

just now. Mustn’t miss a chance like this.

Specially as there’s a good moon, too.

I shall be deadly.”

“I say, can’t I come too?”

A moonlight prowl, with or without

an air-pistol, would just have suited Mike’s

mood.

“No, you can’t,”

said Wyatt. “When I’m caught, as I’m

morally certain to be some day, or night rather, they’re

bound to ask if you’ve ever been out as well

as me. Then you’ll be able to put your hand

on your little heart and do a big George Washington

act. You’ll find that useful when the time

comes.”

“Do you think you will be caught?”

“Shouldn’t be surprised.

Anyhow, you stay where you are. Go to sleep and

dream that you’re playing for the school against

Ripton. So long.”

And Wyatt, laying the bar he had extracted

on the window-sill, wriggled out. Mike saw him

disappearing along the wall.

It was all very well for Wyatt to

tell him to go to sleep, but it was not so easy to

do it. The room was almost light; and Mike always

found it difficult to sleep unless it was dark.

He turned over on his side and shut his eyes, but

he had never felt wider awake. Twice he heard

the quarters chime from the school clock; and the second

time he gave up the struggle. He got out of bed

and went to the window. It was a lovely night,

just the sort of night on which, if he had been at

home, he would have been out after moths with a lantern.

A sharp yowl from an unseen cat told

of Wyatt’s presence somewhere in the big garden.

He would have given much to be with him, but he realised

that he was on parole. He had promised not to

leave the house, and there was an end of it.

He turned away from the window and

sat down on his bed. Then a beautiful, consoling

thought came to him. He had given his word that

he would not go into the garden, but nothing had been

said about exploring inside the house. It was

quite late now. Everybody would be in bed.

It would be quite safe. And there must be all

sorts of things to interest the visitor in Wain’s

part of the house. Food, perhaps. Mike felt

that he could just do with a biscuit. And there

were bound to be biscuits on the sideboard in Wain’s

dining-room.

He crept quietly out of the dormitory.

He had been long enough in the house

to know the way, in spite of the fact that all was

darkness. Down the stairs, along the passage to

the left, and up a few more stairs at the end. The

beauty of the position was that the dining-room had

two doors, one leading into Wain’s part of the

house, the other into the boys’ section.

Any interruption that there might be would come from

the further door.

To make himself more secure he locked

that door; then, turning up the incandescent light,

he proceeded to look about him.

Mr. Wain’s dining-room repaid

inspection. There were the remains of supper

on the table. Mike cut himself some cheese and

took some biscuits from the box, feeling that he was

doing himself well. This was Life. There

was a little soda-water in the syphon. He finished

it. As it swished into the glass, it made a noise

that seemed to him like three hundred Niagaras; but

nobody else in the house appeared to have noticed

it.

He took some more biscuits, and an apple.

After which, feeling a new man, he examined the room.

And this was where the trouble began.

On a table in one corner stood a small

gramophone. And gramophones happened to be Mike’s

particular craze.

All thought of risk left him.

The soda-water may have got into his head, or he may

have been in a particularly reckless mood, as indeed

he was. The fact remains that he inserted

the first record that came to hand, wound the machine

up, and set it going.

The next moment, very loud and nasal,

a voice from the machine announced that Mr. Godfrey

Field would sing “The Quaint Old Bird.”

And, after a few preliminary chords, Mr. Field actually

did so.

“Auntie went to Aldershot in a Paris pom-pom hat.”

Mike stood and drained it in.

“... Good gracious (sang

Mr. Field), what was that?”

It was a rattling at the handle of

the door. A rattling that turned almost immediately

into a spirited banging. A voice accompanied the

banging. “Who is there?” inquired

the voice. Mike recognised it as Mr. Wain’s.

He was not alarmed. The man who holds the ace

of trumps has no need to be alarmed. His position

was impregnable. The enemy was held in check

by the locked door, while the other door offered an

admirable and instantaneous way of escape.

Mike crept across the room on tip-toe

and opened the window. It had occurred to him,

just in time, that if Mr. Wain, on entering the room,

found that the occupant had retired by way of the boys’

part of the house, he might possibly obtain a clue

to his identity. If, on the other hand, he opened

the window, suspicion would be diverted. Mike

had not read his “Raffles” for nothing.

The handle-rattling was resumed.

This was good. So long as the frontal attack

was kept up, there was no chance of his being taken

in the rear—his only danger.

He stopped the gramophone, which had

been pegging away patiently at “The Quaint Old

Bird” all the time, and reflected. It seemed

a pity to evacuate the position and ring down the

curtain on what was, to date, the most exciting episode

of his life; but he must not overdo the thing, and

get caught. At any moment the noise might bring

reinforcements to the besieging force, though it was

not likely, for the dining-room was a long way from

the dormitories; and it might flash upon their minds

that there were two entrances to the room. Or

the same bright thought might come to Wain himself.

“Now what,” pondered Mike,

“would A. J. Raffles have done in a case like

this? Suppose he’d been after somebody’s

jewels, and found that they were after him, and he’d

locked one door, and could get away by the other.”

The answer was simple.

“He’d clear out,” thought Mike.

Two minutes later he was in bed.

He lay there, tingling all over with

the consciousness of having played a masterly game,

when suddenly a gruesome idea came to him, and he

sat up, breathless. Suppose Wain took it into

his head to make a tour of the dormitories, to see

that all was well! Wyatt was still in the garden

somewhere, blissfully unconscious of what was going

on indoors. He would be caught for a certainty!

CHAPTER VI

IN WHICH A TIGHT CORNER IS EVADED

For a moment the situation paralysed

Mike. Then he began to be equal to it. In

times of excitement one thinks rapidly and clearly.

The main point, the kernel of the whole thing, was

that he must get into the garden somehow, and warn

Wyatt. And at the same time, he must keep Mr.

Wain from coming to the dormitory. He jumped out

of bed, and dashed down the dark stairs.

He had taken care to close the dining-room

door after him. It was open now, and he could

hear somebody moving inside the room. Evidently

his retreat had been made just in time.

He knocked at the door, and went in.

Mr. Wain was standing at the window,

looking out. He spun round at the knock, and

stared in astonishment at Mike’s pyjama-clad

figure. Mike, in spite of his anxiety, could

barely check a laugh. Mr. Wain was a tall, thin

man, with a serious face partially obscured by a grizzled

beard. He wore spectacles, through which he peered

owlishly at Mike. His body was wrapped in a brown

dressing-gown. His hair was ruffled. He

looked like some weird bird.

“Please, sir, I thought I heard a noise,”

said Mike.

Mr. Wain continued to stare.

“What are you doing here?” said he at

last.

“Thought I heard a noise, please, sir.”

“A noise?”

“Please, sir, a row.”

“You thought you heard——!”

The thing seemed to be worrying Mr. Wain.

“So I came down, sir,” said Mike.

The house-master’s giant brain

still appeared to be somewhat clouded. He looked

about him, and, catching sight of the gramophone, drew

inspiration from it.

“Did you turn on the gramophone?” he asked.

“Me, sir!” said

Mike, with the air of a bishop accused of contributing

to the Police News.

“Of course not, of course not,”

said Mr. Wain hurriedly. “Of course not.

I don’t know why I asked. All this is very

unsettling. What are you doing here?”

“Thought I heard a noise, please, sir.”

“A noise?”

“A row, sir.”

If it was Mr. Wain’s wish that

he should spend the night playing Massa Tambo to his

Massa Bones, it was not for him to baulk the house-master’s

innocent pleasure. He was prepared to continue

the snappy dialogue till breakfast time.

“I think there must have been a burglar in here,

Jackson.”

“Looks like it, sir.”

“I found the window open.”

“He’s probably in the garden, sir.”

Mr. Wain looked out into the garden

with an annoyed expression, as if its behaviour in

letting burglars be in it struck him as unworthy of

a respectable garden.

“He might be still in the house,” said

Mr. Wain, ruminatively.

“Not likely, sir.”

“You think not?”

“Wouldn’t be such a fool, sir. I

mean, such an ass, sir.”

“Perhaps you are right, Jackson.”

“I shouldn’t wonder if he was hiding in

the shrubbery, sir.”

Mr. Wain looked at the shrubbery,

as who should say, “Et tu, Brute!”

“By Jove! I think I see

him,” cried Mike. He ran to the window,

and vaulted through it on to the lawn. An inarticulate

protest from Mr. Wain, rendered speechless by this

move just as he had been beginning to recover his

faculties, and he was running across the lawn into

the shrubbery. He felt that all was well.

There might be a bit of a row on his return, but he

could always plead overwhelming excitement.

Wyatt was round at the back somewhere,

and the problem was how to get back without being

seen from the dining-room window. Fortunately

a belt of evergreens ran along the path right up to

the house. Mike worked his way cautiously through

these till he was out of sight, then tore for the

regions at the back.

The moon had gone behind the clouds,

and it was not easy to find a way through the bushes.

Twice branches sprang out from nowhere, and hit Mike

smartly over the shins, eliciting sharp howls of pain.

On the second of these occasions a

low voice spoke from somewhere on his right.

“Who on earth’s that?” it said.

Mike stopped.

“Is that you, Wyatt? I say——”

“Jackson!”

The moon came out again, and Mike

saw Wyatt clearly. His knees were covered with

mould. He had evidently been crouching in the

bushes on all fours.

“You young ass,” said

Wyatt. “You promised me that you wouldn’t

get out.”

“Yes, I know, but——”

“I heard you crashing through

the shrubbery like a hundred elephants. If you

must get out at night and chance being sacked,

you might at least have the sense to walk quietly.”

“Yes, but you don’t understand.”

And Mike rapidly explained the situation.

“But how the dickens did he

hear you, if you were in the dining-room?” asked

Wyatt. “It’s miles from his bedroom.

You must tread like a policeman.”

“It wasn’t that.

The thing was, you see, it was rather a rotten thing

to do, I suppose, but I turned on the gramophone.”

“You—what?”

“The gramophone. It started

playing ‘The Quaint Old Bird.’ Ripping

it was, till Wain came along.”

Wyatt doubled up with noiseless laughter.

“You’re a genius,”

he said. “I never saw such a man. Well,

what’s the game now? What’s the idea?”

“I think you’d better

nip back along the wall and in through the window,

and I’ll go back to the dining-room. Then

it’ll be all right if Wain comes and looks into

the dorm. Or, if you like, you might come down

too, as if you’d just woke up and thought you’d

heard a row.”

“That’s not a bad idea.

All right. You dash along then. I’ll

get back.”

Mr. Wain was still in the dining-room,

drinking in the beauties of the summer night through

the open window. He gibbered slightly when Mike

reappeared.

“Jackson! What do you mean

by running about outside the house in this way!

I shall punish you very heavily. I shall certainly

report the matter to the headmaster. I will not

have boys rushing about the garden in their pyjamas.

You will catch an exceedingly bad cold. You will

do me two hundred lines, Latin and English. Exceedingly

so. I will not have it. Did you not hear

me call to you?”

“Please, sir, so excited,”

said Mike, standing outside with his hands on the

sill.

“You have no business to be

excited. I will not have it. It is exceedingly

impertinent of you.”

“Please, sir, may I come in?”

“Come in! Of course, come

in. Have you no sense, boy? You are laying

the seeds of a bad cold. Come in at once.”

Mike clambered through the window.

“I couldn’t find him, sir. He must

have got out of the garden.”

“Undoubtedly,” said Mr.

Wain. “Undoubtedly so. It was very

wrong of you to search for him. You have been

seriously injured. Exceedingly so.”

He was about to say more on the subject

when Wyatt strolled into the room. Wyatt wore

the rather dazed expression of one who has been aroused

from deep sleep. He yawned before he spoke.

“I thought I heard a noise, sir,” he said.

He called Mr. Wain “father”

in private, “sir” in public. The presence

of Mike made this a public occasion.

“Has there been a burglary?”

“Yes,” said Mike, “only he has got

away.”

“Shall I go out into the garden,

and have a look round, sir?” asked Wyatt helpfully.

The question stung Mr. Wain into active eruption once

more.

“Under no circumstances whatever,”

he said excitedly. “Stay where you are,

James. I will not have boys running about my garden

at night. It is preposterous. Inordinately

so. Both of you go to bed immediately. I

shall not speak to you again on this subject.

I must be obeyed instantly. You hear me, Jackson?

James, you understand me? To bed at once.

And, if I find you outside your dormitory again to-night,

you will both be punished with extreme severity.

I will not have this lax and reckless behaviour.”

“But the burglar, sir?” said Wyatt.

“We might catch him, sir,” said Mike.

Mr. Wain’s manner changed to

a slow and stately sarcasm, in much the same way as

a motor-car changes from the top speed to its first.

“I was under the impression,”

he said, in the heavy way almost invariably affected

by weak masters in their dealings with the obstreperous,

“I was distinctly under the impression that I

had ordered you to retire immediately to your dormitory.

It is possible that you mistook my meaning. In

that case I shall be happy to repeat what I said.

It is also in my mind that I threatened to punish you

with the utmost severity if you did not retire at once.

In these circumstances, James—and you,

Jackson—you will doubtless see the necessity

of complying with my wishes.”

They made it so.

CHAPTER VII

IN WHICH MIKE IS DISCUSSED

Trevor and Clowes, of Donaldson’s,

were sitting in their study a week after the gramophone

incident, preparatory to going on the river. At

least Trevor was in the study, getting tea ready.

Clowes was on the window-sill, one leg in the room,

the other outside, hanging over space. He loved

to sit in this attitude, watching some one else work,

and giving his views on life to whoever would listen

to them. Clowes was tall, and looked sad, which

he was not. Trevor was shorter, and very much

in earnest over all that he did. On the present

occasion he was measuring out tea with a concentration

worthy of a general planning a campaign.

“One for the pot,” said Clowes.

“All right,” breathed Trevor. “Come

and help, you slacker.”

“Too busy.”

“You aren’t doing a stroke.”

“My lad, I’m thinking

of Life. That’s a thing you couldn’t

do. I often say to people, ‘Good chap,

Trevor, but can’t think of Life. Give him

a tea-pot and half a pound of butter to mess about

with,’ I say, ‘and he’s all right.

But when it comes to deep thought, where is he?

Among the also-rans.’ That’s what

I say.”

“Silly ass,” said Trevor,

slicing bread. “What particular rot were

you thinking about just then? What fun it was

sitting back and watching other fellows work, I should

think.”

“My mind at the moment,”

said Clowes, “was tensely occupied with the

problem of brothers at school. Have you got any

brothers, Trevor?”

“One. Couple of years younger

than me. I say, we shall want some more jam to-morrow.

Better order it to-day.”

“See it done, Tigellinus, as

our old pal Nero used to remark. Where is he?

Your brother, I mean.”

“Marlborough.”

“That shows your sense.

I have always had a high opinion of your sense, Trevor.

If you’d been a silly ass, you’d have let

your people send him here.”

“Why not? Shouldn’t have minded.”

“I withdraw what I said about your sense. Consider it unsaid. I have a brother

myself. Aged fifteen. Not a bad chap in his way. Like the heroes of the school

stories. ‘Big blue eyes literally bubbling over with fun.’ At least, I suppose

it’s fun to him. Cheek’s what I call it. My people wanted to send him here. I

lodged a protest. I said, ‘One Clowes is ample for any public school.’”

“You were right there,” said Trevor.

“I said, ‘One Clowes is

luxury, two excess.’ I pointed out that

I was just on the verge of becoming rather a blood

at Wrykyn, and that I didn’t want the work of

years spoiled by a brother who would think it a rag

to tell fellows who respected and admired me——”

“Such as who?”

“——Anecdotes

of a chequered infancy. There are stories about

me which only my brother knows. Did I want them

spread about the school? No, laddie, I did not.

Hence, we see my brother two terms ago, packing up

his little box, and tooling off to Rugby. And

here am I at Wrykyn, with an unstained reputation,

loved by all who know me, revered by all who don’t;

courted by boys, fawned upon by masters. People’s

faces brighten when I throw them a nod. If I

frown——”

“Oh, come on,” said Trevor.

Bread and jam and cake monopolised

Clowes’s attention for the next quarter of an

hour. At the end of that period, however, he returned

to his subject.

“After the serious business

of the meal was concluded, and a simple hymn had been

sung by those present,” he said, “Mr. Clowes

resumed his very interesting remarks. We were

on the subject of brothers at school. Now, take

the melancholy case of Jackson Brothers. My heart

bleeds for Bob.”

“Jackson’s all right.

What’s wrong with him? Besides, naturally,

young Jackson came to Wrykyn when all his brothers

had been here.”

“What a rotten argument.

It’s just the one used by chaps’ people,

too. They think how nice it will be for all the

sons to have been at the same school. It may

be all right after they’re left, but while they’re

there, it’s the limit. You say Jackson’s

all right. At present, perhaps, he is. But

the term’s hardly started yet.”

“Well?”