The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Lighter Side of School Life

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Lighter Side of School Life

Author: Ian Hay

Illustrator: Lewis Christopher Edward Baumer

Release date: December 22, 2010 [eBook #34721]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steve Read, Suzanne Shell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIGHTER SIDE OF SCHOOL LIFE ***

cover

THE LIGHTER SIDE OF

SCHOOL LIFE

BY IAN HAY

AUTHOR OF "A SAFETY MATCH"

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS REPRODUCED

FROM PASTEL DRAWINGS BY

LEWIS BAUMER

BOSTON

LE ROY PHILLIPS

First Edition published October nineteen

hundred fourteen; reprinted May

nineteen fifteen

Printed in Scotland by

Ballantyne, Hanson, & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh

TO

THE MEMBERS

OF

THE MOST RESPONSIBLE

THE LEAST ADVERTISED

THE WORST PAID

AND

THE MOST RICHLY REWARDED

PROFESSION

IN THE WORLD

THE LIST OF CONTENTS

| I. | THE HEADMASTER | page 1 |

| II. | THE HOUSEMASTER | 35 |

| III. | SOME FORM-MASTERS | 57 |

| IV. | BOYS | 91 |

| V. | THE PURSUIT OF KNOWLEDGE | 121 |

| VI. | SCHOOL STORIES | 149 |

| VII. | "MY PEOPLE" | 175 |

| VIII. | THE FATHER OF THE MAN | 205 |

THE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

reproduced from drawings by

Lewis Baumer

| LORD'S | Frontispiece |

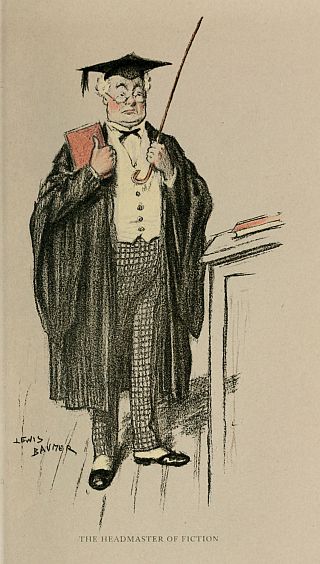

| THE HEADMASTER OF FICTION | page 16 |

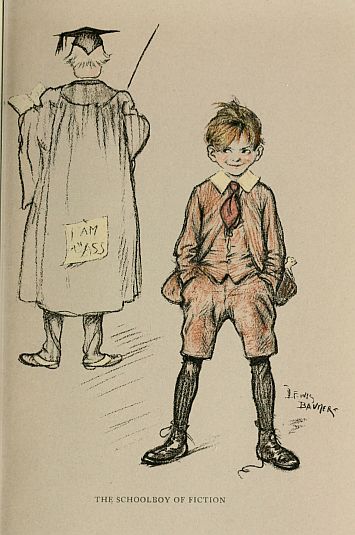

| THE SCHOOLBOY OF FICTION | 32 |

| THE DAREDEVIL | 48 |

| THE LUNCHEON INTERVAL: PORTRAIT OF | |

| A GENTLEMAN WHO HAS SCORED | |

| FIFTY RUNS | 64 |

| THE FRENCH MASTER: (I) FICTION, | |

| (II) FACT | 88 |

| THE INTELLECTUAL | 104 |

| THE NIPPER | 120 |

| THE FAG: "SIC VOS NON VOBIS" | 152 |

| THE SCHOOLGIRL'S DREAM | 176 |

| RANK AND FILE | 192 |

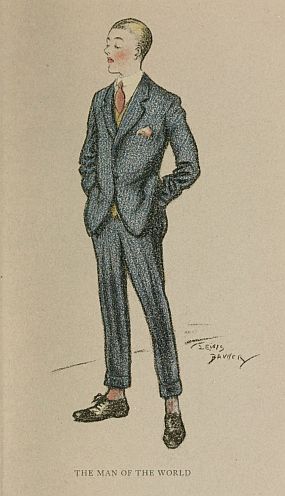

| THE MAN OF THE WORLD | 208 |

NOTE

These sketches originally appeared in "Blackwood's

Magazine," to the proprietors of which I am indebted

for permission to reproduce them in book form.

IAN HAY

[1]

CHAPTER ONE

THE HEADMASTER

[3]

First of all there is the

Headmaster of Fiction. He is invariably called

"The Doctor," and he wears cap and gown even

when birching malefactors—which he does intermittently

throughout the day—or attending

a cricket match. For all we know he wears

them in bed.

He speaks a language peculiar to himself—a

language which at once enables you to recognise

him as a Headmaster; just as you may recognise

a stage Irishman from the fact that he

says "Begorrah!", or a stage sailor from the fact

that he has to take constant precautions with

his trousers. Thus, the "Doctor" invariably addresses

his cowering pupils as "Boys!"—a

form of address which in reality only survives

nowadays in places where you are invited to

"have another with me"—and if no audience

of boys is available at the moment, he addresses

a single boy as if he were a whole audience.

To influential parents he is servile and oleaginous,

and he treats his staff with fatuous pomposity.

Such a being may have existed—may

exist—but we have never met him.[4]

What of the Headmaster of Fact? To condense

him into a type is one of the most difficult

things in the world, for this reason. Most

of us have known only one Headmaster in our

lives—if we have known more we are not likely

to say so, for obvious reasons—and it is difficult

for Man (as distinct from Woman), to argue

from the particular to the general. Moreover,

the occasions upon which we have met

the subject of our researches at close quarters

have not been favourable to dispassionate character-study.

It is difficult to form an unbiassed

or impartial judgment of a man out of material

supplied solely by a series of brief interviews

spread over a period of years—interviews at

which his contribution to the conversation has

been limited to a curt request that you will bend

over, and yours to a sequence of short sharp

ejaculations.

However, some of us have known more than

one Headmaster, and upon us devolves the solemn

duty of distilling our various experiences

into a single essence.

What are the characteristics of a great Headmaster?

Instinct at once prompts us to premise

that he must be a scholar and a gentleman. A

gentleman, undoubtedly, he must be; but nowadays[5]

scholarship—high classical scholarship—is

a hindrance rather than a help. To supervise

the instruction of modern youth a man

requires something more than profound learning:

he must possess savoir faire. If you set a

great scholar—and a great scholar has an unfortunate

habit of being nothing but a great

scholar—in charge of the multifarious interests

of a public school, you are setting a razor to cut

grindstones. As well appoint an Astronomer

Royal to command an Atlantic liner. He may

be on terms of easy familiarity with the movements

of the heavenly bodies, yet fail to understand

the right way of dealing with refractory

stokers.

A Headmaster is too busy a personage to

keep his own scholarship tuned up to concert

pitch; and if he devotes adequate time to this

object—and a scholar must practise almost as

diligently as a pianist or an acrobat if he is to

remain in the first flight—he will have little

leisure left for less intellectual but equally vital

duties. Nowadays in great public schools the

Head, although he probably takes the Sixth

for an hour or two a day, delegates most of his

work in this direction to a capable and up-to-date

young man fresh from the University, and[6]

devotes his energies to such trifling details as

the organisation of school routine, the supervision

of the cook, the administration of justice,

the diplomatic handling of the Governing

Body, and the suppression of parents.

So far then we are agreed—the great advantage

of dogmatising in print is that one can take

the agreement of the reader for granted—that

a Headmaster must be a gentleman, but not necessarily

a scholar—in the very highest sense of

the word. What other virtues must he possess?

Well, he must be a majestic figurehead. This

is not so difficult as it sounds. The dignity which

doth hedge a Headmaster is so tremendous

that the dullest and fussiest of the race can

hardly fail to be impressive and awe-inspiring

to the plastic mind of youth. More than one

King Log has left a name behind him, through

standing still in the limelight and keeping his

mouth shut. But then he was probably lucky in

his lieutenants.

Next, he must have a sense of humour. If he

cannot see the entertaining side of youthful depravity,

magisterial jealousy, and parental fussiness,

he will undoubtedly go mad. A sense of

humour, too, will prevent him from making a

fool of himself, and a Headmaster must never[7]

do that. It also engenders Tact, and Tact is the

essence of life to a man who has to deal every

day with the ignorant, and the bigoted, and the

sentimental. (These adjectives are applicable

to boys, masters, and parents, and may be applied

collectively or individually with equal

truth.) Not that all humorous people are tactful:

bitter experience of the practical joker has

taught us that. But no person can be tactful

who cannot see the ludicrous side of things.

There is a certain Headmaster of to-day, justly

celebrated as a brilliant teacher and a born organiser,

who is lacking—entirely lacking—in

that priceless gift of the gods, a sense of humour,

with which is incorporated Tact. Shortly after

he took up his present appointment, one of the

most popular boys in the school, while leading

the field in a cross-country race, was run over

and killed by an express train which emerged

from a tunnel as he ran across the line, within

measurable distance of accomplishing a record

for the course.

Next morning the order went forth that the

whole school were to assemble in the great hall.

They repaired thither, not unpleasantly thrilled.

There would be a funeral oration, and boys

are curiously partial to certain forms of emotionalism.[8]

They like to be harangued before a

football-match, for instance, in the manner of

the Greeks of old. These boys had already had

a taste of the Head's quality as a speaker, and

they felt that he would do their departed hero

justice. They reminded one another of the moving

words which the late Head had spoken

when an Old Boy had fallen in battle a few years

before under particularly splendid circumstances.

They remembered how pleased the Old

Boy's father and mother had been about it.

Their comrade, whom they had revered and

loved as recently as yesterday, would receive a

fitting farewell too; and they would all feel the

prouder of the school for the words that they

were about to hear. They did not say this aloud,

for the sentimentality of boys is of the inarticulate

kind, but the thought was uppermost in their

minds.

Presently they were all assembled, and the

Head appeared upon his rostrum. There was

a deathlike stillness: not a boy stirred.

Then the Head spoke.

"Any boy," he announced, "found trespassing

upon the railway-line in future will be expelled.

You may go."

They went. The organisation of that school[9]

is still a model of perfection, and its scholarship

list is exceptionally high. But the school has

never forgiven the Head, and never will so long

as tradition and sentiment count for anything

in this world.

So far, then, we have accumulated the following

virtues for the Headmaster. He must be a

gentleman, a picturesque figure-head, and must

possess a sense of humour.

He must also, of course, be a ruler. Now

you may rule men in two ways—either with a

rapier or a bludgeon; but a man who can gain

his ends with the latter will seldom have recourse

to the former. The Headmaster who

possesses on the top of other essential qualities

the power of being uncompromisingly and

divinely rude, is to be envied above all men.

For him life is full of short cuts. He never

argues. "L'école, c'est moi," he growls, and

no one contradicts him. Boys idolise him. In

his presence they are paralysed with fear, but

away from it they glory in his ferocity of mien

and strength of arm. Masters rave impotently

at his brusquerie and absolutism; but A says

secretly to himself: "Well, it's a treat to see

the way the old man keeps B and C up to the

collar." As for parents, they simply refuse to[10]

face him, which is the head and summit of that

which a master desires of a parent.

Such a man is Olympian, having none of the

foibles or soft moments of a human being. He

dwells apart, in an atmosphere too rarefied for

those who intrude into it. His subjects never

regard him as a man of like passions with

themselves: they would be quite shocked if such an

idea were suggested to them. I once asked a

distinguished alumnus of a great school, which

had been ruled with consummate success for

twenty-four years by such a Head as I have

described, to give me a few reminiscences of

the great man as a man—his characteristics,

his mannerisms, his vulnerable points, his

tricks of expression, his likes and dislikes, and

his hobbies.

My friend considered.

"He was a holy terror," he announced, after

profound meditation.

"Quite so. But in what way?"

My friend thought again.

"I can't remember anything particular about

him," he said, "except that he was a holy terror—and

the greatest man that ever lived!"

"But tell me something personal about him.

How did his conversation impress you?"[11]

"Conversation? Bless you, he never conversed

with anybody. He just told them what he

thought about a thing, and that settled it. Besides,

I never exchanged a word with him in

my life. But he was a great man."

"Didn't you meet him all the time you were

at school?"

"Oh yes, I met him," replied my friend with

feeling—"three or four times. And that reminds

me, I can tell you something personal

about him. The old swine was left-handed! A

great man, a great man!"

Happy the warrior who can inspire worship

on such sinister foundations as these!

The other kind has to prevail by another

method—the Machiavellian. As a successful

Headmaster of my acquaintance once brutally

but truthfully expressed it: "You simply have

to employ a certain amount of low cunning if

you are going to keep a school going at all."

And he was right. A man unendowed with the

divine gift of rudeness would, if he spent his

time answering the criticisms or meeting the

objections of colleagues or parents or even

boys, have no time for anything else. So he

seeks refuge either in finesse or flight. If a parent

rings him up on the telephone, he murmurs[12]

something courteous about a wrong number

and then leaves the receiver off the hook. If a

housemaster, swelling with some grievance or

scheme of reform, bears down upon him upon

the cricket field on a summer afternoon, he

adroitly lures him under a tree where another

housemaster is standing, and leaves them there

together. If an enthusiastic junior discharges

at his head some glorious but quite impracticable

project, such as the performance of a pastoral

play in the school grounds, or the enforcement

of a vegetarian diet upon the School for

experimental purposes, he replies: "My dear

fellow, the Governing Body will never hear of

it!" What he means is: "The Governing Body

shall never hear of it."

He has other diplomatic resources at his call.

Here is an example.

A Headmaster once called his flock together

and said:

"A very unpleasant and discreditable thing

has happened. The municipal authorities have

recently erected a pair of extremely ornate and

expensive—er—lamp-posts outside the residence

of the Mayor of the town. These lamp-posts

appear to have attracted the unfavourable

notice of the School. Last Sunday evening,[13]

between seven and eight o'clock, they were

attacked and wrecked, apparently by volleys of

stones."

There was a faint but appreciative murmur

from those members of the School to whom the

news of this outrage was now made public for

the first time. But a baleful flash from the

Head's spectacles restored instant silence.

"Several parties of boys," he continued,

"must have passed these lamp-posts on that

evening, on their way back to their respective

houses after Chapel. I wish to see all boys who

in any way participated in the outrage in my

study directly after Second School. I warn

them that I shall make a severe example of

them." His voice rose to a blare. "I will not

have the prestige and fair fame of the School

lowered in the eyes of the Town by the vulgar

barbarities of a parcel of ill-conditioned little

street-boys. You may go!"

The audience rose to their feet and began to

steal silently away. But they were puzzled.

The Old Man was no fool as a rule. Did he

really imagine that chaps would be such mugs

as to own up?

But before the first boy reached the door the

Head spoke again.[14]

"I may mention," he added very gently, "that

the attack upon the—er—lamp-posts was witnessed

by a gentleman resident in the neighbourhood,

a warm friend of the School. He

was able to identify one of the culprits, whose

name is in my possession. That is all."

And quite enough too! When the Head visited

his study after Second School, he found

seventeen malefactors meekly awaiting chastisement.

But he never divulged the name of the boy

who had been identified, or for that matter the

identity of the warm friend of the School. I

wonder!

One more quality is essential to the great

Headmaster. He must possess the Sixth

Sense. He must see nothing, yet know everything

that goes on in the School. Etiquette

forbids that he should enter one of his colleague's

houses except as an invited guest; yet

he must be acquainted with all that happens inside

that house. He is debarred by the same

rigid law from entering the form-room or studying

the methods and capability of any but the

most junior form-masters; and yet he must

know whether Mr. A. in the Senior Science[15]

Set is expounding theories of inorganic chemistry

which have been obsolete for ten years, or

whether Mr. B. in the Junior Remove is accustomed

meekly to remove a pool of ink from the

seat of his chair before beginning his daily

labours. He must not mingle with the boys,

for that would be undignified; yet he must, and

usually does, know every boy in the School by

sight, and something about him. He must

never attempt to acquire information by obvious

cross-examination either of boy or master,

or he will be accused of prying and interference;

and he can never, or should never, discuss

one of his colleagues with another. And yet

he must have his hand upon the pulse of the

School in such wise as to be able to tell which

master is incompetent, which prefect is untrustworthy,

which boy is a bully, and which

House is rotten. In other words, he must

possess a Red Indian's powers of observation

and a woman's powers of intuition. He must be

able to suck in school atmosphere through his

pores. He must be able to judge of a man's

keenness or his fitness for duty by his general

attitude and conversation when off duty. He

must be able to read volumes from the demeanour

of a group in the corner of the quadrangle,[16]

from a small boy's furtive expression, or even

from the timbre of the singing in chapel. He

must notice which boy has too many friends,

and which none at all.

Such are a few of the essentials of the great

Headmaster, and to the glory of our system be

it said that there are still many in the land. But

the type is changing. The autocratic Titan of

the past has been shorn of his locks by two Delilahs—Modern

Sides and Government Interference.

First, Modern Sides.

Time was when A Sound Classical Education,

Lady Matron, and Meat for Breakfast

formed the alpha and omega of a public school

prospectus. But times have changed, at least in

so far as the Sound Classical Education is concerned.

The Headmaster of the old school, who

looks upon the classics as the foundation of all

education, and regards modern sides as a sop to

the parental Cerberus, finds himself called upon

to cope with new and strange monsters.

First of all, the members of that once despised

race, the teachers of Science. Formerly

these maintained a servile and apologetic existence,

supervising a turbulent collection of

young gentlemen whose sole appreciation of

[17]this branch of knowledge was derived from the

unrivalled opportunities which its pursuit afforded

for the creation of horrible stenches and

untimely explosions. Now they have uprisen,

and, asseverating that classical education is a

pricked bubble, ask boldly for expensive apparatus

and a larger tract of space in the time-table.

Then the parent. He has got quite out of

hand lately. In days past things were different.

Usually an old public-school boy himself, and

proudly conscious that Classics had made him

"what he was," the parent deferred entirely to

the Headmaster's judgment, and entrusted his

son to his care without question or stipulation.

But a new race of parents has arisen, men who

avow, modestly but firmly, that they have been

made not by the Classics but by themselves,

and who demand, with a great assumption of

you-can't-put-me-off-with-last-season's-goods,

that their offspring shall be taught something

up-to-date—something which will be "useful"

in an office.

Again, there is our old friend the Man in the

Street, who, through the medium of his favourite

mouthpiece, the halfpenny press, asks the

Headmaster very sternly what he means by[18]

turning out "scholars" who are incapable of

writing an invoice in commercial Spanish, and

to whom double entry is Double Dutch.

And lastly there is the boy himself, whose

utter loathing and horror of education as a

whole has not blinded him to the fact that the

cultivation of some branches thereof calls for

considerably less effort than that of others, and

who accordingly occupies the greater part of

his weekly letter home with fervent requests to

his parents to permit him to drop Classics and

take up modern languages or science.

The united agitations of this incongruous

band have called into existence the Modern Side—Delilah

Number One. Now for Number Two.

Until a few years ago the State confined its

ebullience in matters educational to the Board

Schools. But with the growth of national education

and class jealousy—the two seem to go

hand-in-hand—the working classes of this

country began to point out to the Government,

not altogether unreasonably, that what is sauce

for the goose is sauce for the gander. "Why,"

they inquired bitterly, "should we be the only

people educated? Must the poor always be oppressed,

while the rich go free? What about

these public schools of yours—the seminaries[19]

of the bloated and pampered Aristocracy? You

leave us alone for a bit, and give them a turn,

or we may get nasty!" So a pliable Government,

remembering that public-school masters

are not represented in Parliament while the

working-classes are, obeyed. They began by

publicly announcing that in future all teachers

must be trained to teach. To give effect to this

decree, they declared their intention of immediately

introducing a Bill to provide that after a

certain date no Headmaster of any school, high

or low, would be permitted to engage an assistant

who had not earned a certificate at a training

college and registered himself in a mysterious

schedule called 'Column B,' paying a guinea

for the privilege.

The prospective schoolmasters of the day—fourth-year

men at Oxford and Cambridge,

inexperienced in the ways of Government Departments—were

deeply impressed. Most of

them hurriedly borrowed a guinea and registered

in Column B. They even went further.

In the hope of forestalling the foolish virgins

of their profession, they attended lectures and

studied books which dealt with the science of

education. They became attachés at East End

Board-Schools, where, under the supervision[20]

of a capable but plebeian Master of Method,

they endeavoured to instruct classes of some

sixty or seventy babbling six-year-olds in the

elements of reading and writing, in order that

hereafter they might be better able to elucidate

Cicero and Thucydides to scholarship candidates

at a public school.

Others, however—the aforementioned foolish

virgins—whose knowledge of British politics

was greater than their interest in the Theory

of Education, decided to 'wait and see.' That is

to say, they accepted the first vacancy at a

public school which presented itself and settled

down to work upon the old lines, a year's seniority

to the good. In a just world this rashness

and improvidence would have met with its due

reward—namely, ultimate eviction (when the

Bill passed) from a comfortable berth, and a

stern command to go and learn the business of

teaching before presuming to teach. But unfortunately

the Bill never did pass: it never so

much as reached its First Reading. It lies now

in some dusty pigeon-hole in the Education

Office, forgotten by all save its credulous victims.

The British Exchequer is the richer by

several thousand guineas, contributed by a class

to whom of course a guinea is a mere bagatelle;[21]

and here and there throughout the public

schools of this country there exist men who,

when they first joined the Staff, had the mysterious

formula, "Reg. Col. B.," printed upon

their testimonials, and discoursed learnedly to

stupefied Headmasters about brain-tracks and

psychology, and the mutual stimulus of co-sexual

competition, for a month or two before

awakening to the one fundamental truth which

governs public-school education—namely, that

if you can keep boys in order you can teach

them anything; if not, all the Column B.'s

in the Education Office will avail you nothing.

That was all. The incident is ancient history

now. It was a capital practical joke, perpetrated

by a Government singularly lacking in humour

in other respects; and no one remembers it

except the people to whom the guineas belong.

But it gave the Headmasters of the country a

bad fright. It provides them with a foretaste of

the nuisance which the State can make of itself

when it chooses to be paternal. So such of the

Headmasters as were wise decided to be upon

their guard for the future against the blandishments

of the party politician. And they were

justified; for presently the Legislature stirred[22]

in its sleep and embarked upon yet another

enterprise.

Philip, king of Macedon, used to say that no

city was impregnable whose gates were wide

enough to admit a single mule-load of gold.

Similarly the Board of Education decided that

no public school, however haughty or exclusive,

could ever again call its soul its own once the

Headmaster (of his own free will, or overruled

by the Governing Body) had been asinine

enough to accept a "grant." So they approached

the public schools with fair words. They

said:—

"How would you like a subsidy, now, wherewith

to build a new science laboratory? What

about a few State-aided scholarships? Won't

you let us help you? Strict secrecy will be observed,

and advances made upon your note of

hand alone"—or words to that effect.

The larger and better-endowed public

schools, conscious of a fat bank-balance and a

long waiting list of prospective pupils, merely

winked their rheumy eyes and shook their

heavy heads.

"Timeo Danaos," they growled—"et dona

ferentes."

When this observation was translated to the[23]

Minister for Education, he smiled enigmatically,

and bided his time. But some of the

smaller schools, hard pressed by modern competition,

gobbled the bait at once. The mule-load

of gold arrived promptly, and close in its

train came Retribution. Inspectors swooped

down—clerkly young men who in their time

had passed an incredible number of Standards,

and were now receiving what was to them a

princely salary for indulging in the easiest and

most congenial of all human recreations—that

of criticising the efforts of others. There arrived,

too, precocious prize-pupils from the

Board Schools, winners of County Council

scholarships which entitled them to a few years'

"polish" at a public school—a polish but slowly

attained, despite constant friction with their new

and loving playmates.

But the great strongholds still held out. So

other methods were adopted. The examination

screw was applied.

As most of us remember to our cost, we used

periodically in our youth at school to suffer from

an "examination week," during which a mysterious

power from outside was permitted to

inflict upon us examination papers upon every

subject upon earth, under the title of Oxford[24]

and Cambridge Locals—the High, the Middle,

and the Low—or, in Scotland, the Leaving

Certificate. These papers were set and corrected

by persons unknown, residing in London;

and we were supervised as we answered

them not by our own preceptors—they stampeded

joyously away to play golf—but by strange

creatures who took charge of the examination-room

with an air of uneasy assurance, suggestive

of a man travelling first-class with a third-class

ticket. In due course the results were

declared; and the small school which gained a

large percentage of Honourable Mentions was

able to underline the fact heavily in its prospectus.

These examinations were, if not organised,

at least recognised by the State; and once they

had pierced the battlements of a school an Inspector

invariably crawled through the breach

after them. Henceforth that school was subject

to periodical visitations and reports.

Naturally the Headmasters of the great public

schools clanged their gates and dropped

their portcullises against such an infraction of

the law that a Headmaster's school is his castle.

But, as already mentioned, the screw was applied.

The certificates awarded to successful

candidates in these examinations were made[25]

the key to higher things. Three Higher Grade

Certificates, for instance, were accepted in lieu

of certain subjects in Oxford Smalls and Cambridge

Little-go. The State pounced upon this

principle and extended it. The acquisition of a

sufficient number of these certificates now paved

the way to various State services. Extra marks

or special favours were awarded to young gentlemen

who presented themselves for Sandhurst

or Woolwich or the Civil Service bringing

their sheaves with them in the form of

Certificates. Roughly speaking, the more Certificates

a candidate produced the more enthusiastically

he was excused from the necessity of

learning the elements of his trade.

The governing bodies of various professions

took up the idea. For instance, if you produced

four Higher Certificates—say for Geography,

Botany, Electro-Dynamics, and Practical

Cookery—you were excused the preliminary

examination of the Society of Chartered Accountants.

(We need not pin ourselves down to

the absolute accuracy of these details: they are

merely for purposes of illustration.) Anyhow, it

was a beautiful idea. A Headmaster of my acquaintance

once assured me that he believed

that the possession of a complete set of Higher[26]

Grade Certificates for all the Local Examinations

of a single year would entitle the holder

to a seat in the reformed House of Lords.

In other words, it was still possible to get into

the Universities and Services without Certificates,

but it was very much easier to get in with

them.

So the great Headmasters climbed down.

But they made terms. They would accept the

Local Examinations, and they would admit Inspectors

within their fastnesses; but they respectfully

but firmly insisted upon having some

sort of say in the choice of the Inspector.

The Government met them more than half-way.

In fact, they fell in with the plan with

suspicious heartiness.

"Certainly, my dear sir," they said: "you

shall choose your own Inspector; and what is

more, you shall pay him! Think of that! The

man will be a mere tool in your hands—a hired

servant—and you can do what you like with

him."

It was an ingenious and comforting way of

putting things, and may be commended to the

notice of persons writhing in a dentist's chair;

for it forms an exact parallel: the description

applies to dentist and inspector equally. However,[27]

the Headmasters agreed to it; and now

all our great schools receive inspectorial visitations

of some kind. That is to say, upon an appointed

date a gentleman comes down from

London, spends the day as the guest of the

Headmaster; and after being conducted about

the premises from dawn till dusk, departs in the

gloaming with his brain in a fog and some sixteen

guineas in his pocket.

He is a variegated type, this Super-Inspector.

Frequently he is a clever man who has

failed as a schoolmaster and now earns a comfortable

living because he remembered in time

the truth of the saying: La critique est aisé,

l'art difficile. More often he is a superannuated

University professor, with a penchant for irrelevant

anecdote and a disastrous sense of humour.

Sometimes he is aggressive and dictatorial,

but more often (humbly remembering

where he is and who is going to pay for all this)

apprehensive, deferential, and quite inarticulate.

Sometimes he is a scholar and a gentleman,

with a real appreciation of the atmosphere

of a public school and a sound knowledge of the

principles of education. But not always. And

whoever he is and whatever he is, the Head

loathes him impartially and dispassionately.[28]

Such are some of the thorns with which the

pillow of a modern Headmaster is stuffed. His

greatest stumbling-block is Tradition—the

hoary edifices of convention and precedent,

built up and jealously guarded by Old Boys and

senior Housemasters. Of Parents we will treat

in another place.

What is he like, the Headmaster of to-day?

Firstly and essentially, he is no longer a despot.

He is a constitutional sovereign, like all

other modern monarchs; and perhaps it is better

so. Though a Head still exercises enormous

personal power, for good or ill, a school no

longer stands or falls by its Headmaster, as in

the old days, any more than a country stands or

falls by its King, as in the days of the Stuarts.

Public opinion, Housemasters, the prefectorial

system—these have combined to modify his

absolutism. But though a bad Headmaster

may not be able to wreck a good school, it is

certain that no school can ever become great,

or remain great, without a great man at the

head of it.

Time has wrought other changes. Twenty

years ago no man could ever hope to reach the

summit of the scholastic universe who was not

in Orders and the possessor of a First Class[29]

Classical degree. Now the layman, the modern-side

man, above all the man of affairs, are raising

their heads.

Under these new conditions, what manner of

man is the great Head of to-day?

He is essentially a man of business. A clear

brain and a sense of proportion enable him to

devise schemes of education in which the old

idealism and the new materialism are judiciously

blended. He knows how to draw up a

school time-table—almost as difficult and complicated

a document as Bradshaw—making

provision, hour by hour, day by day, for the

teaching of a very large number of subjects by

a limited number of men to some hundreds of

boys all at different stages of progress, in such

a way that no boy shall be left idle for a single

hour and no master be called upon to be in two

places at once.

He understands school finance and educational

politics, which are even more peculiar

than British party politics. He combines the

art of being able to rule upon his own initiative

for months at a time, and yet render a satisfactory

account of his stewardship to an ignorant

and inquisitive Governing Body which meets

twice a year.[30]

He is, as ever, an imposing figure-head; and

if he is, or has been, an athlete, so much the

easier for him in his dealings with the boys. He

possesses the art of managing men to an extent

sufficient to maintain his Housemasters in

some sort of line, and to keep his junior staff

punctual and enthusiastic without fussing or

herding them. He is a good speaker, and though

not invariably in Orders, he appreciates the

enormous influence that a powerful sermon in

Chapel may exercise at a time of crisis; and he

supplies that sermon himself.

He keeps a watchful eye upon an army of

servants, and does not shrink from the drudgery

of going through kitchen-accounts or laundry

estimates. He investigates complaints personally,

whether they have to do with a House's

morals or a butler's perquisites.

He keeps abreast of the educational needs

of the time. He is a persona grata at the Universities,

and usually knows at which University

and at which College thereof one of his boys

will be most likely to win a scholarship. In the interests

of the Army Class he maintains friendly

relations with the War Office, because, in

these days of the chronic reform of that institution,

to be in touch with the "permanent" military[31]

mind is to save endless trouble over examinations

which are going to be dropped or

schedules which are about to be abandoned

before they come into operation. He cultivates

the acquaintance of those in high places, not for

his own advancement, but because it is good for

the School to be able to bring down an occasional

celebrity, to present prizes or open a new

wing. For the same reason he dines out a good

deal—often when he has been on his feet since

seven o'clock in the morning—and entertains

in return, so far as he can afford it, people who

are likely to be able to do the School a good

turn. For with him it is the School, the School,

the School, all the time.

If he possesses private means of his own, so

much the better; for the man with a little spare

money in his pocket possesses powers of leverage

denied to the man who has none. I know of

a Headmaster who once shamed his Governing

Body into raising the salaries of the Junior Staff

to a decent standard by supplementing those

salaries out of his own slender resources for

something like five years.

And above all, he has sympathy and insight.

When a master or boy comes to him with a

grievance he knows whether he is dealing with[32]

a chronic grumbler or a wronged man. The

grumbler can be pacified by a word or chastened

by a rebuke; but a man burning under

a sense of real injustice and wrong will never be

efficient again until his injuries are redressed.

If a colleague, again, comes to him with a

scheme of work, or organisation, or even play,

he is quick to see how far the scheme is valuable

and practicable, and how far it is mere fuss and

officiousness. He is enormously patient over

this sort of thing, for he knows that an untimely

snub may kill the enthusiasm of a real worker,

and that a little encouragement may do wonders

for a diffident beginner. He knows how to

stimulate the slacker, be he boy or master; and

he keeps a sharp look-out to see that the willing

horse does not overwork himself. (This

latter, strange as it may seem, is the harder task

of the two.) And he can read the soul of that

most illegible of books—save to the understanding

eye—the boy, through and through. He

can tell if a boy is lying brazenly, or lying because

he is frightened, or lying to screen a

friend, or speaking the truth. He knows when

to be terrible in anger, and when to be indescribably

gentle.

Usually he is slightly unpopular. But he

[33]does not allow this to trouble him overmuch,

for he is a man who is content to wait for his

reward. He remembers the historic verdict of

"A beast, but a just beast," and chuckles.

Such a man is an Atlas, holding up a little

world. He is always tired, for he can never

rest. His so-called hours of ease are clogged by

correspondence, most of it quite superfluous,

and the telephone has added a new terror to his

life. But he is always cheerful, even when alone;

and he loves his work. If he did not, it would

kill him.

A Headmaster no longer regards his office

as a stepping-stone to a Bishopric. In the near

future, as ecclesiastical and classical traditions

fade, that office is more likely to be regarded as

a qualification for a place at the head of a Department

of State, or a seat in the Cabinet. A

man who can run a great public school can run

an Empire.[35]

CHAPTER TWO

THE HOUSEMASTER

[37]

To the boy, all masters (as

distinct from The Head) consist of one class—namely,

masters. The fact that masters are

divisible into grades, or indulge in acrimonious

diversities of opinion, or are subject to the

ordinary weaknesses of the flesh (apart from

chronic shortness of temper) has never occurred

to him.

This is not so surprising as it sounds. A

schoolmaster's life is one long pose. His perpetual

demeanour is that of a blameless enthusiast.

A boy never hears a master swear—at

least, not if the master can help it; he seldom

sees him smoke or drink; he never hears him

converse upon any but regulation topics, and

then only from the point of view of a rather

bigoted archangel. The idea that a master in

his private capacity may go to a music-hall, or

back a horse, or be casual in his habits, or be

totally lacking in religious belief, would be quite

a shock to a boy.

It is true that when half-a-dozen ribald spirits

are gathered round the Lower Study fire

after tea, libellous tongues are unloosed. The

humorist of the party draws joyous pictures of[38]

his Housemaster staggering home to bed after

a riotous evening with an Archdeacon, or being

thrown out of the Empire in the holidays. But

no one in his heart takes these legends seriously—least

of all their originator. They are

merely audacious irreverences.

All day and every day the boy sees the master,

impeccably respectable in cap and gown,

rebuking the mildest vices, extolling the dullest

virtues, singing the praises of industry and

application, and attending Chapel morning and

evening. A boy has little or no intuition: he

judges almost entirely by externals. To him a

master is not as other men are: he is a special

type of humanity endowed with a permanent

bias towards energetic respectability, and grotesquely

ignorant of the seamy side of life. The

latter belief in particular appears to be quite ineradicable.

But in truth the scholastic hierarchy is a most

complicated fabric. At the summit of the Universe

stands the Head. After him come the

senior masters—or, as they prefer somewhat

invidiously to describe themselves, the permanent

staff—then the junior masters. The whole

body are divided and subdivided again into little

groups—classical men, mathematical men,[39]

science men, and modern-language men—each

group with its own particular axe to grind and

its own tender spots. Then follow various specialists,

not always resident; men whose life is

one long and usually ineffectual struggle to convince

the School—including the Head—that

music, drawing, and the arts generally are subjects

which ought to be taken seriously, even

under the British educational system.

As already noted, after the Head—quite literally—come

the Housemasters. They are always

after him: one or other of the troop is perpetually

on his trail; and unless the great man

displays the ferocity of the tiger or the wisdom

of the serpent, they harry him exceedingly.

Behold him undergoing his daily penance—in

audience in his study after breakfast. To him

enter severally:

A., a patronising person, with a few helpful

suggestions upon the general management of

the School. He usually begins: "In the old

Head's day, we never, under any circumstances——"

B., whose speciality is to discover motes in

the eyes of other Housemasters. He announces

that yesterday afternoon he detected a member

of the Eleven fielding in a Panama hat. "Are[40]

Panama hats permitted by the statutes of the

School? I need hardly say that the boy was not

a member of my House."

C., a wobbler, who seeks advice as to whether

an infraction of one of the rules of his House

can best be met by a hundred lines of Vergil or

public expulsion.

D., a Housemaster pure and simple, urging

the postponement of the Final House-Match,

D.'s best bowler having contracted an ingrowing

toe-nail.

E., another, insisting that the date be adhered

to—for precisely the same reason.

(He receives no visit from F., who holds that

a Housemaster's House is his castle, and would

as soon think of coming to the fountain-head

for advice as he would of following the advice

if it were offered.)

G., an alarmist, who has heard a rumour that

smallpox has broken out in the adjacent village,

and recommends that the entire school be vaccinated

forthwith.

H., a golfer, suggesting a half-holiday, to

celebrate some suddenly unearthed anniversary

in the annals of Country or School.

Lastly, on the telephone, I., a valetudinarian,

to announce that he is suffering from double[41]

pneumonia, and will be unable to come into

School until after luncheon.

To be quite just, I. is the rarest bird of all.

The average schoolmaster has a perfect passion

for sticking to his work when utterly unfit

for it. In this respect he differs materially from

his pupil, who lies in bed in the dawning hours,

cudgelling his sleepy but fertile brain for a disease

which

(1) Has not been used before.

(2) Will incapacitate him for work all morning.

(3) Will not prevent him playing football in

the afternoon.

But if a master sprains his ankle, he hobbles

about his form-room on a crutch. If he contracts

influenza, he swallows a jorum of ammoniated

quinine, puts on three waistcoats, and totters

into school, where he proceeds to disseminate

germs among his not ungrateful charges. Even

if he is rendered speechless by tonsillitis, he

takes his form as usual, merely substituting

written invective (chalked up on the blackboard),

for the torrent of verbal abuse which he

usually employs as a medium of instruction.

It is all part—perhaps an unconscious part—of

his permanent pose as an apostle of what is[42]

strenuous and praiseworthy. It is also due to a

profound conviction that whoever of his colleagues

is told off to take his form for him will

indubitably undo the work of many years within

a few hours.

Besides harrying the head and expostulating

with one another, the Housemasters wage unceasing

war with the teaching staff.

The bone of contention in every case is a

boy, and the combat always follows certain

well-defined lines.

A form-master overtakes a Housemaster

hurrying to morning chapel, and inquires carelessly:

"By the way, isn't Binks tertius your boy?"

The Housemaster guardedly admits that

this is so.

"Well, do you mind if I flog him?"

"Oh, come, I say, isn't that rather drastic?

What has he done?"

"Nothing—not a hand's-turn—for six

weeks."

"Um!" The Housemaster endeavours to

look severely judicial. "Young Binks is rather

an exceptional boy," he observes. (Young Binks

always is.) "Are you quite sure you know him?"

The form-master, who has endured Master[43]

Binks' society for nearly two years, and knows

him only too well, laughs caustically.

"Yes," he says, "I do know him: and I quite

agree with you that he is rather an exceptional

boy."

"Ah!" says the Housemaster, falling into the

snare. "Then——"

"An exceptional young swab," explains the

form-master.

By this time they have entered the Chapel,

where they revert to their daily task of setting

an example by howling one another down in

the Psalms.

After Chapel the Housemaster takes the

form-master aside and confides to him the intelligence

that he has been a Housemaster for

twenty-five years. The form-master, suppressing

an obvious retort, endeavours to return to

the question of Binks; but is compelled instead

to listen to a brief homily upon the management

of boys in general. As neither gentleman has

breakfasted, the betting as to which will lose

his temper first is almost even, with odds slightly

in favour of the form-master, being the younger

and hungrier man. However, it is quite certain

that one of them will—probably both. The

light of reason being thus temporarily obscured,[44]

they part, to meditate further repartees and

complain bitterly of one another to their colleagues.

But it is very seldom that Master Binks profits

by such Olympian differences as these. Possibly

the Housemaster may decline to give the

form-master permission to flog Binks, but in

nine cases out of ten, being nothing if not conscientious,

he flogs Binks himself, carefully explaining

to the form-master afterwards, by implication

only, that he has done so not from

conviction, but from an earnest desire to bolster

up the authority of an inexperienced and incompetent

colleague. But these quibbles, as already

observed, do not help the writhing Binks

at all.

However, a Housemaster contra mundum,

and a Housemaster in his own House, are very

different beings. We have already seen that

a bad Headmaster cannot always prevent a

School from being good. But a House stands or

falls entirely by its Housemaster. If he is a

good Housemaster it is a good House: if not,

nothing can save it. And therefore the responsibility

of a Housemaster far exceeds that of a

Head.

Consider. He is in loco parentis—with[45]

apologies to Stalky!—to some forty or fifty of

the shyest and most reserved animals in the

world; one and all animated by a single desire—namely,

to prevent any fellow-creature from

ascertaining what is at the back of their minds.

Schoolgirls, we are given to understand, are

prone to open their hearts to one another, or to

some favourite teacher, with luxurious abandonment.

Not so boys. Up to a point they are

frankness itself: beyond that point lie depths

which can only be plumbed by instinct and

intuition—qualities whose possession is the only

test of a born Housemaster. All his flock must

be an open book to him: he must understand

both its collective and its individual tendencies.

If a boy is inert and listless, the Housemaster

must know whether his condition is due

to natural sloth or some secret trouble, such as

bullying or evil companionship. If a boy appears

dour and dogged, the Housemaster has to decide

whether he is shy or merely insolent.

Private tastes and pet hobbies must also be

borne in mind. The complete confidence of a

hitherto unresponsive subject can often be won

by a tactful reference to music or photography.

The Housemaster must be able, too, to distinguish

between brains and mere precocity, and[46]

to separate the fundamentally stupid boy from

the lazy boy who is pretending to be stupid—an

extremely common type. He must cultivate

a keen nose for the malingerer, and at the same

time keep a sharp look-out for fear lest the conscientious

plodder should plod himself silly. He

must discriminate between the whole-hearted

enthusiast and the pretentious humbug who

simulates keenness in order to curry favour.

And above all, he must make allowances for

heredity and home influence. Many a Housemaster

has been able to adjust his perspective

with regard to a boy by remembering that the

boy has a drunken father, or a neurotic mother,

or no parents at all.

He must keep a light hand on House politics,

knowing everything, yet doing little, and saying

almost nothing at all. If a Housemaster

be blatantly autocratic; if he deputes power to

no one; if he prides himself upon his iron discipline;

if he quells mere noise with savage

ferocity and screws down the safety-valve implacably

upon healthy ragging, he will reap his

reward. He will render his House quiet, obedient—and

furtive. Under such circumstances

prefects are a positive danger. Possessing special

privileges, but no sense of responsibility,[47]

they regard their office merely as a convenient

and exclusive avenue to misdemeanour.

On the other hand, a Housemaster must not

allow his prefects unlimited authority, or he

will cease to be master in his own House. In

other words, he must strike an even balance

between sovereign and deputed power—an

undertaking which has sent dynasties toppling

before now.

In addition to all this, he must be an Admirable

Crichton. Whatever his own particular

teaching subject may be, he will be expected,

within the course of a single evening's "prep,"

to be able to unravel a knotty passage in Æschylus,

"unseen," solve a quadratic equation on

sight, compose a chemical formula, or complete

an elegiac couplet. He must also be prepared

at any hour of the day or night to explain how

leg-breaks are manufactured, recommend a list

of novels for the House library, set a broken

collar-bone, solve a jig-saw puzzle in the Sick-room,

assist an Old Boy in the choice of a

career, or prepare a candidate for Confirmation.

And the marvel is that he always does it—in

addition to his ordinary day's work in school.

And what is his remuneration? One of the

rarest and most precious privileges that can be[48]

granted to an Englishman—the privilege of

keeping a public house!

Let me explain. For the first twenty years

of his professional career a schoolmaster works

as a mere instructor of youth. By day he teaches

his own particular subject; by night he looks

over proses or corrects algebra papers. In his

spare time he imparts private instruction to

backward boys or scholarship candidates. Probably

he bears a certain part in the supervision

of the School games. He is possibly treasurer

of one or two of the boys' own organisations—the

Fives Club or the Debating Society—and

as a rule he is permitted to fill up odd moments

by sub-editing the School magazine or organising

sing-songs. He cannot as a rule afford to

marry; so he lives the best years of his life in

two rooms, looking forward to the time, in the

dim and hypothetical future, when he will possess

what the ordinary artisan usually acquires

on passing out of his teens—a home of his own.

At length, after many days, provided that a

sufficient number of colleagues die or get superannuated,

comes his reward, and he enters upon

the realisation of his dreams. He is now a

Housemaster, with every opportunity (and full

permission) to work himself to death.

[49]

Still, you say, the labourer is worthy of his

hire. A man occupying a position so onerous

and responsible as this will be well remunerated.

What is his actual salary?

In many cases he receives no salary, as a

Housemaster, at all. Instead, he is accorded

the privilege of running his new home as a combined

lodging-house and restaurant. His spare

time (which the reader will have gathered is

more than considerable) is now pleasantly occupied

in purchasing beef and mutton and selling

them to Binks tertius. As his tenure of the

House seldom exceeds ten or fifteen years, he

has to exercise considerable commercial enterprise

in order to make a sufficient "pile" to retire

upon—as Binks tertius sometimes discovers

to his cost. In other words, a scholar and

gentleman's reward for a life of unremitting

labour in one of the most exacting yet altruistic

fields in the world is a licence to enrich himself

for a period of years by "cornering" the daily

bread of the pupils in his charge. And yet we

feel surprised, and hurt, and indignant, when

foreigners suggest that we are a nation of shopkeepers.

The life of a Housemaster is a living example

of the lengths to which the British passion[50]

for undertaking heavy responsibilities and

thankless tasks can be carried. Daily, hourly,

he finds himself in contact (and occasional collision)

with boys—boys for whose moral and

physical welfare he is responsible; who in theory

at least will regard him as their natural enemy;

and who occupy the greater part of their leisure

time in criticising and condemning him and

everything that is his—his appearance, his

character, his voice, his wife; the food that he

provides and the raiment that he wears. He is

harried by measles, mumps, servants, tradesmen,

and parents. He feels constrained to invite

every boy in his House to a meal at least

once a term, which means that he is almost

daily deprived of the true-born Briton's birthright

of being uncommunicative at breakfast.

His life is one long round of colourless routine,

tempered by hair-bleaching emergencies.

But he loves it all. He maintains, and ultimately

comes to believe, that his House is the

only House in the School in which both justice

and liberty prevail, and his boys the only boys

in the world who know the meaning of hard

work, good food, and esprit de corps. He pities

all other Housemasters, and tells them so at

frequent intervals; and he expostulates paternally[51]

and sorrowfully with form-masters who

vilify the members of his cherished flock in half-term

reports.

And his task is not altogether thankless. Just

as the sun never sets upon the British Empire,

so it never sets upon all the Old Boys of a great

public school at once. They are gone out into

all lands: they are upholding the honour of the

School all the world over. And wherever they

are—London, Simla, Johannesburg, Nairobi,

or Little Pedlington Vicarage—they never lose

touch with their old Housemaster. His correspondence

is enormous; it weighs him down: but

he would not relinquish a single picture postcard

of it. He knows that wherever two or three

of his Old Boys are gathered together, be it in

Bangalore or Buluwayo, the talk will always

drift round in time to the old School and the

old House. They will refer to him by his nickname—"Towser,"

or "Potbelly," or "Swivel-Eye,"—and

reminiscences will flow.

"Do you remember the old man's daily gibe

when he found us chucking bread at dinner?

'Hah! There will be a bread pudding tomorrow!'"

"Do you remember the jaw he gave us when

the news came about Macpherson's V.C.?"[52]

"Do you remember his Sunday trousers?

Oh, Lord!"

"Do you remember how he tanned Goat

Hicks for calling The Frog a cochon? Fourteen,

wasn't it?"

"Do you remember the grub he gave the

whole House the time we won the House-match

by one wicket, with Old Mike away?"

"Do you remember how he broke down at

prayers the night little Martin died?"

"Do you remember his apologising to that

young swine Sowerby before the whole House

for losing his temper and clouting him over the

head? That must have taken some doing. We

rooted Sowerby afterwards for grinning."

"I always remember the time," interpolates

one of the group, "when he scored me off for

roller-skating on Sunday."

"How was that?"

"Well, it was this way. I had got leave of

morning Chapel on some excuse or other, and

was skating up and down the Long Corridor,

having a grand time. The old man came out of

his study—I thought he was in Chapel—and

growled, looking at me over his spectacles—you

remember the way?——"

"Yes, rather. Go on!"[53]

"He growled:—'Boy, do you consider roller-skating

a Sunday pastime?' I, of course, looked

a fool, and said, 'No, sir.' 'Well,' chuckled the

old bird, 'I do: but I always make a point of

respecting a man's religious scruples. I will

therefore confiscate your skates.' And he did!

He gave them back to me next day, though."

"I always remember him," says another, "the

time I nearly got sacked. By rights I ought to

have been, but I believe he got me off at the last

moment. Anyhow, he called me into his study

and told me I wasn't to go after all. He didn't

jaw me, but said I could take an hour off school

and go and telegraph home that things were all

right. My people had been having a pretty bad

time over it, I knew, and so did he. I was pretty

near blubbing, but I held out. Then, just as I

got to the door, he called me back. I turned

round, rather in a funk that the jaw was coming

after all. But he growled out:—

"'It's a bit late in the term. The exchequer

may be low. Here is sixpence for the telegram.'

"This time I did blub. Not one man in a

million would have thought of the sixpence.

As a matter of fact, fourpence-halfpenny was

all I had in the world."[54]

And so on. His ears—especially his right

ear—must be burning all day long.

Of course all Housemasters are not like this.

If you want to hear about the other sort, take

up The Lanchester Tradition, by Mr. G. F.

Bradby, and make the acquaintance of Mr.

Chowdler—an individual example of a great

type run to seed. And there is Dirty Dick, in

The Hill.

When he has fulfilled his allotted span as a

Housemaster, our friend retires—not from

school-mastering, but from the provision trade.

With his hardly-won gains he builds himself a

house in the neighbourhood of the school, and

lives there in a state of otium cum dignitate. He

still takes his form: he continues to do so until

old age descends upon him, or a new broom at

the head of affairs makes a clean sweep of the

"permanent" staff.

He is mellower now. He no longer washes

his hands of all responsibility for the methods

of his colleagues, or thanks God that his boys

are not as other masters' boys are. He does not

altogether enjoy his work in school: he is getting

a little deaf, and is inclined to be testy. But[55]

teaching is his meat and his drink and his father

and his mother. He sticks to it because it holds

him to life.

Though elderly now, he enjoys many of the

pleasures of middle age. For instance, he has

usually married late, so his children are still

young; and he is therefore spared the pain,

which most parents have to suffer, of seeing the

brood disperse just when it begins to be needed

most. Or perhaps he has been too devoted to

his world-wide family of boys to marry at all. In

that case he lives alone; but you may be sure

that his spare bedroom is seldom empty. No

Old Boy ever comes home from abroad without

paying a visit to his former Housemaster. Rich,

poor, distinguished, or obscure—they all come.

They tell him of their adventures; they recall

old days; they deplore the present condition of

the School and the degeneracy of the Eleven;

they fight their own battles over again. They

confide in him. They tell him things they would

never tell their fathers or their wives. They

bring him their ambitions, and their failures—not

their successes; those are for others to speak

of—even their love-affairs. And he listens to

them all, and advises them all, this very tender

and very wise old Ulysses. To him they are[56]

but boys still, and he would not have them otherwise.

"The heart of a Boy in the body of a Man,"

he says—"that is a combination which can never

go wrong. If I have succeeded in effecting

that combination in a single instance, then I

have not run in vain, neither laboured in vain.

[57]

CHAPTER THREE

SOME FORM-MASTERS

[59]

NUMBER ONE THE NOVICE

Arthur Robinson, B.A., late exhibitioner

of St. Crispin's College, Cambridge,

having obtained a First Class, Division Three,

in the Classical Tripos, came down from the

University at the end of his third year and decided

to devote his life to the instruction of

youth.

In order to gratify this ambition as speedily

as possible, he applied to a scholastic agency

for an appointment. He was immediately furnished

with type-written notices of some thirty

or forty. Almost one and all, they were for

schools which he had never heard of; but the

post in every case was one which the Agency

could unreservedly recommend. At the foot of

each notice was typed a strongly worded appeal

to him to write (at once) to the Headmaster,

explaining first and foremost that he had heard

of this vacancy through our Agency. After that

he was to state his degree (if any); if a member

of the Church of England; if willing to participate

in School games; if musical; and so on.

He was advised, if he thought it desirable, to

enclose a photograph of himself.[60]

A further sheaf of such notices reached him

every morning for about two months; but as

none of them offered him more than a hundred-and-twenty

pounds a year, and most of them

a good deal less, Arthur Robinson, who was a

sensible young man, resisted the temptation,

overpowering to most of us, of seizing the very

first opportunity of earning a salary, however

small, simply because he had never earned anything

before, and allowed the notices to accumulate

upon one end of his mantelpiece.

Finally he had recourse to his old College

tutor, who advised him of a vacancy at Eaglescliffe,

a great public school in the west of England,

and by a timely private note to the Headmaster

secured his appointment.

Next morning Arthur Robinson received

from the directorate of the scholastic agency—the

existence of which he had almost forgotten—a

rapturous letter of congratulation, reminding

him that the Agency had sent him notice

of the vacancy upon a specified date, and delicately

intimating that their commission of five

per cent. upon the first year's salary was payable

on appointment. Arthur, who had long

since given up the task of breasting the Agency's

morning tide of desirable vacancies, mournfully[61]

investigated the heap upon the mantelpiece,

and found that the facts were as stated.

There lay the notice, sandwiched between a

document relating to the advantages to be derived

from joining the staff of a private school

in North Wales, where material prosperity was

guaranteed by a salary of eighty pounds per

annum, and social success by the prospect of

meat-tea with the Principal and his family; and

another, in which a clergyman (retired) required

a thoughtful and energetic assistant (one hundred

pounds a year, non-resident) to aid him in

the management of a small but select seminary

for backward and epileptic boys.

Arthur laid the matter before his tutor, who

informed him that he must pay up, and be a

little less casual in his habits in future. He

therefore wrote a reluctant cheque for ten

pounds, and having thus painfully imbibed the

first lesson that a schoolmaster must learn—namely,

the importance of attending to details—departed

to take up his appointment at

Eaglescliffe.

He arrived the day before term began, to

find that lodgings had been apportioned to him

at a house in the village, half a mile from the

School. His first evening was spent in making[62]

the place habitable. That is to say, he removed

a number of portraits of his landlady's relatives

from the walls and mantelpiece, and stored

them, together with a collection of Early Victorian

heirlooms—wool-mats and prism-laden

glass vases—in a cupboard under the window-seat.

In their place he set up fresh gods; innumerable

signed photographs of young men,

some in frames, some in rows along convenient

ledges, others bunched together in a sort of

wire entanglement much in vogue among the

undergraduates of that time. Some of these

photographs were mounted upon light-blue

mounts, and these were placed in the most conspicuous

position. Upon the walls he hung a

collection of framed groups of more young

men, with bare knees and severe expressions,

in some of which Arthur Robinson himself

figured.

After that, having written to his mother and

a girl in South Kensington, he walked up the

hill in the darkness to the Schoolhouse, where

he was to be received in audience by the Head.

The great man was sitting at ease before his

study fire, and exhibited unmistakable signs of

recent slumber.

"I want you to take Remove B, Robinson,"[63]

he said. "They are a mixed lot. About a quarter

of them are infant prodigies—Foundation

Scholars—who make this form their starting-point

for higher things; and the remainder are

centenarians, who regard Remove B as a sort

of scholastic Chelsea Hospital, and are fully

prepared to end their days there. Stir 'em up,

and don't let them intimidate the small boys into

a low standard of work. Their subjects this

term will be Cicero de Senectute and the Alcestis,

without choruses. Have you any theories

about the teaching of boys?"

"None whatever," replied Arthur Robinson

frankly.

"Good! There is only one way to teach

boys. Keep them in order: don't let them play

the fool or go to sleep; and they will be so

bored that they will work like niggers merely

to pass the time. That's education in a nutshell.

Good night!"

Next morning Arthur Robinson invested

himself in an extremely new B.A. gown, which

seemed very long and voluminous after the

tattered and attenuated garment which he had

worn at Cambridge—usually twisted into a

muffler round his neck—and walked up to[64]

School. (It was the last time he ever walked:

thereafter, for many years, he left five minutes

later, and ran.) Timidly he entered the Common

Room. It was full of masters, some twenty

or thirty of them, old, young, and middle-aged.

As many as possible were grouped round the

fire—not in the orderly, elegant fashion of

grown-up persons; but packed together right

inside the fender, with their backs against the

mantelpiece. Nearly everyone was talking,

and hardly anyone was listening to anyone

else. Two or three—portentously solemn elderly

men—were conferring darkly together

in a corner. Others were sitting upon the table

or arms of chairs, reading newspapers, mostly

aloud. No one took the slightest notice of Arthur

Robinson, who accordingly sidled into an

unoccupied corner and embarked upon a self-conscious

study of last term's time-table.

"I hear they have finished the new Squash

Courts," announced a big man who was almost

sitting upon the fire. "Take you on this afternoon,

Jacker?"

"Have you got a court?" inquired the gentleman

addressed.

"Not yet, but I will. Who is head of Games

this term?"

[65]

"Etherington major, I think."

"Good Lord! He can hardly read or write,

much less manage anything. I wonder why

boys always make a point of electing congenital

idiots to their responsible offices. Warwick,

isn't old Etherington in your House?"

"He is," replied Warwick, looking up from

a newspaper.

"Just tell him I want a Squash Court this

afternoon, will you?"

"I am not a District Messenger Boy," replied

Mr. Warwick coldly. Then he turned upon

a colleague who was attempting to read his

newspaper over his shoulder.

"Andrews," he said, "if you wish to read this

newspaper I shall be happy to hand it over to

you. If not, I shall be grateful if you will refrain

from masticating your surplus breakfast in my

right ear."

Mr. Andrews, scarlet with indignation, moved

huffily away, and the conversation continued.

"I doubt if you will get a court, Dumaresq,"

said another voice—a mild one. "I asked for

one after breakfast, and Etherington said they

were all bagged."

"Well, I call that the limit!" bellowed that

single-minded egotist, Mr. Dumaresq.[66]

"After all," drawled a supercilious man

sprawling across a chair, "the courts were built

for the boys, weren't they?"

"They may have been built for the boys,"

retorted Dumaresq with heat, "but they were

more than half paid for by the masters. So put

that in your pipe, friend Wellings, and——"

"Your trousers are beginning to smoke," interpolated

Wellings calmly. "You had better

come out of the fender for a bit and let me

in."

So the babble went on. To Arthur Robinson,

still nervously perusing the time-table, it all

sounded like an echo of the talk which had prevailed

in the Pupil Room at his own school

barely five years ago.

Presently a fresh-faced elderly man crossed

the room and tapped him on the shoulder.

"You must be Robinson," he said. "My

name is Pollard, also of St. Crispin's. Come and

dine with me to-night, and tell me how the old

College is getting on."

The ice broken, the grateful Arthur was introduced

to some of his colleagues, including

the Olympian Dumaresq, the sarcastic Wellings,

and the peppery Warwick. Next moment

a bell began to ring upon the other side of the[67]

quadrangle, as there was a general move for the

door.

Outside, Arthur Robinson encountered the

Head.

"Good morning, Mr. Robinson!" (It was a

little affectation of the Head's to address his

colleagues as 'Mr.' when in cap and gown: at

other times his key-note was informal bonhomie).

"Have you your form-room key?"

"Yes, I have."

"In that case I will introduce you to your

flock."

At the end of the Cloisters, outside the locked

door of Remove B, lounged some thirty young