The Project Gutenberg eBook of A Bayard From Bengal

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: A Bayard From Bengal

Author: F. Anstey

Illustrator: Bernard Partridge

Release date: July 11, 2011 [eBook #36703]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A BAYARD FROM BENGAL ***

A BAYARD FROM BENGAL

EXORTED HER, WITH AN ELOQUENCE THAT MOVED ALL PRESENT,

TO ABANDON HER FRIVOLITIES AND LEVITIES

Transcriber's Note:

Author's notes on illustrations have been consolidated

at the end of the text.

A BAYARD FROM BENGAL

Being some account of the Magnificent and Spanking

Career of Chunder Bindabun Bhosh, Esq., B.A., Cambridge,

by Hurry Bungsho Jabberjee, B.A., Calcutta

University, author of "Jottings and Tittlings," etc.,

etc., to which is appended the Parables and Proverbs

of Piljosh, freely translated from the Original

Styptic by Another Hand, with Introduction,

Notes and Appendix by the above Hurry Bungsho

Jabberjee, B.A.

THE WHOLE EDITED AND REVISED

BY

F. ANSTEY

AUTHOR OF "VICE VERSA," ETC. ETC.

WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS BY BERNARD PARTRIDGE

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET, W.C.

LONDON

1902

Reprinted from "Punch"

[v]

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | From Calcutta to Cambridge Oversea Route | 1 |

| II. | How Mr Bhosh Delivered a Damsel from a Demented Cow | 8 |

| III. | The Involuntary Fascinator | 16 |

| IV. | A Kick from a Friendly Foot | 24 |

| V. | The Duel to the Death | 33 |

| VI. | Lord Jolly is Satisfied | 41 |

| VII. | The Adventure of the Unwieldy Gifthorse | 48 |

| VIII. | A Rightabout Facer for Mr Bhosh | 55 |

| IX. | The Dark Horse | 63 |

| X. | Trust Her Not! She is Fooling Thee! | 70 |

| XI.[vi] | Stone Walls do not make a Cage | 78 |

| XII. | A Race against Time | 86 |

| XIII. | A Sensational Derby Struggle | 93 |

| XIV. | A Grand Finish | 102 |

| __________ | ||

| The Parables of Piljosh | 111 |

[vii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

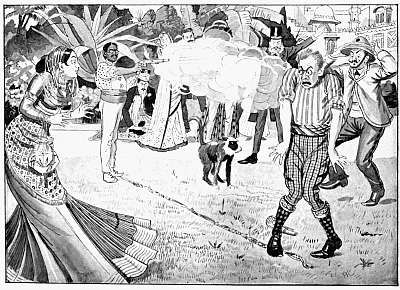

| "Exhorted her, with an Eloquence that moved all present, to abandon her Frivolities and Levities" | Frontispiece |

| "Gave the Animal into Custody as a Disturber of the Peace" | 12 |

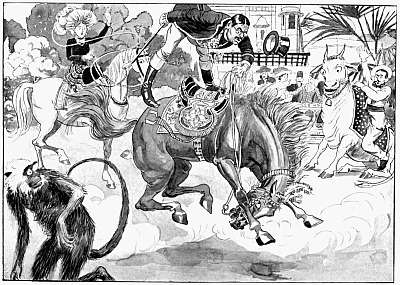

| "Dismayed the Beast by his determined and ferocious aspect" | 28 |

| "The Bullet had perforated a large circular orifice in Honble Bodger's Hat" | 42 |

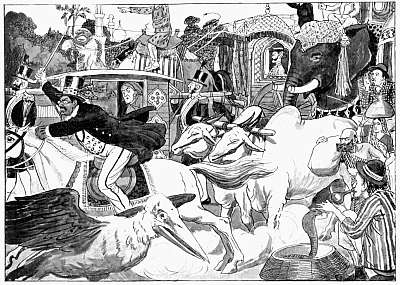

| "The Cantankerous Steed executed a Leap with Astounding Agility" | 50 |

| "'My Daughter, I foresee many Calamities which will inevitably befall Thee'" | 58 |

| "The Road was chocked full with every description of conveyance" | 88 |

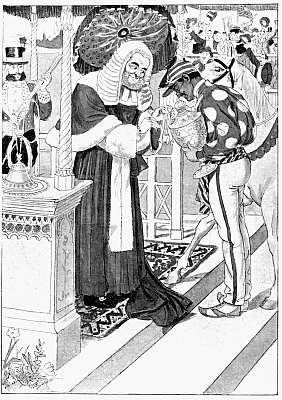

| "The Notorious Blue Ribbon was pinned by the Judge upon his proud and heaving Bosom" | 106 |

[ix]

PRELIMINARY

I have the honour humbly to inform my

readers that, after prolonged consumption

of midnight oil, I succeeded in completing this

imposing society novel, which is now, by the

indulgence of my friends and kind fathers, the

honble publishers, laid at their feet.

My inducement to this enterprise was the

spectacle of very inferior rubbish palmed off by

so-called popular novelists such as Honbles

Kipling, Joshua Barrie, Antony Weyman,

Stanley Hope, and the collaborative but

feminine authoresses of "The Red Thumb in

the Pottage," all of whom profess (very, very

incorrectly) to give accurate reliable descriptions

of Indian, English or Scotch episodes.

The pity of it, that a magnificent and gullible

British Public should be suckled like a babe on

such spoonmeat and small beer![x]

Would no one arise, inflamed by the pure

enthusiasm of his cacoethes scribendi, and write

a romance which shall secure the plerophory

of British, American, Anglo-Indian, Colonial,

and Continental readers by dint of its imaginary

power and slavish fidelity to Nature?

And since Echo answered that no one replied

to this invitation, I (like a fool, as some will

say) rushed in where angels were apprehensive

of being too bulky to be borne.

Being naturally acquainted with gentlemen

of my own nationality and education, and also,

of course, knowing London and suburban

society ab ovo usque ad mala (or, from the

new-laid egg to the stage when it is beginning

to go bad), I decided to take as my theme the

adventures of a typically splendid representative

of Young India on British soil, and I am in

earnest hopes to avoid the shocking solecisms

and exaggerations indulged in by ordinary

English novelists.

I have been compelled to take to penmanship

of this sort owing to pressure of res angusta[xi]

domi, the immoderate increase of hostages to

fortune, and proportionate falling off of emoluments

from my profession as Barrister-at-Law.

Therefore, I hope that all concerned will

smile favourably upon my new departure, and

will please kindly understand that, if my

English literary style has suffered any deterioration,

it is solely due to my being out of

practice, and such spots on the sun must be

excused as mere flies in ointment.

After forming my resolution of writing a

large novel, I confided it to my crony, Mr Ram

Ashootosh Lall, who warmly recommended

me to persevere in such a magnum opus. So

I became divinely inflated periodically every

evening from 8 to 12 P.M., disregarding all

entreaties from feminine relatives to stop and

indulge in a blow-out on ordinary eatables,

like Archimedes when Troy was captured,

who was so engrossed in writing prepositions

on the sand that he was totally unaware that

he was being barbarously slaughtered.[xii]

And at length my colossal effusion was

completed, and I had written myself out; after

which I had the indescribable joy and felicity

to read my composition to my mothers-in-law

and wives and their respective progenies and

offspring, whereupon, although they were not

acquainted with a word of English, they were

overcome by such severe admiration for my

fecundity and native eloquence that they

swooned with rapture.

I am not a superstitious, but I took the trouble

to consult a soothsayer, as to the probable

fortunes of my undertaking, and he at once

confidently predicted that my novel was to

render all readers dumb as fishes with sheer

amazement and prove a very fine feather in

my cap.

For all the above reasons, I am modestly

confident that it will be generally recognised

as a masterpiece, especially when it is remembered

that it is the work of a native Indian,

whose 'prentice hand is still a novice in wielding

the currente calamo of fiction.[xiii]

I cannot conclude without some allusion to

the drawings which are, I believe, to adorn

my work, but which I have not yet been

enabled to inspect, owing to the fact that,

having fish of more importance to fry at the

time, I commissioned a certain young English

friend (the same who furnished sundry poetic

headings for chapters) to engage a designer

for the pictorial department.

Needless to say, I intended that he was to

award the apple only to some Royal Academician

of distinguished talents—yet at the

eleventh hour, when too late to make other

arrangements, I am informed that the job has

been entrusted to a certain Birnadhur Pahtridhji,

whose name (though probably incorrectly

transcribed) certainly denotes a draughtsman

of native Indian origin!

Whether he is fully competent for such a

task I cannot at present say. But, unless he

is qualified, like myself, by actual residence

in Great Britain, I fear that he may not possess

sufficient familiarity with the customs and[xiv]

solecisms of English society to avoid at least

a few ludicrous and even lamentable mistakes.

To guard against such contingencies I shall

insert a note or comment opposite each picture

as it is submitted to me, pointing out in what

respects (if any) the artist has failed to represent

the author's intentions.

I sincerely hope that I may now and then

be able to pat the aforesaid Mr P. on the back

instead of acting as a Rhadamanthus to rap

his knuckles.[1]

A BAYARD FROM BENGAL

CHAPTER I

FROM CALCUTTA TO CAMBRIDGE OVERSEA ROUTE

At sea the stoutest stomach jerks,

Far, far away from native soil,

When Ocean's heaving waterworks

Burst out in Brobdingnagian boil!

Stanza written at Sea, by H. B. J.

(unpublished).

THE waves of Neptune erected their

seething and angry crests to incredible

altitudes; overhead in fuliginous storm-clouds

the thunder rumbled its terrific bellows, and

from time to time the ghastly flare of lightning

illuminated the entire neighbourhood.

The tempest howled like a lost dog through

the cordage of the good ship Rohilkund

(Captain O. Williams), which lurched through

the vasty deep as though overtaken by the

drop too much.[2]

At one moment her poop was pointed towards

celestial regions; at another it aimed

itself at the recesses of Davey Jones's locker;

and such was the fury of the gale that only a

paucity of the ship's passengers remained perpendicular,

and Mr Chunder Bindabun Bhosh

was recumbent on his beam end, prostrated by

severe sickishness, and hourly expecting to

become initiated in the Great Secret.

Bitterly did he lament his hard lines in

venturing upon the Black Water, to be snipped

off in the flower of his adolescence, and never

again to behold the beloved visages of his

relations!

So heartrending were his tears and groans

that they moved all on board, and Honble

Mr Commissioner Copsey, who was returning

on leave, kindly came to inquire the cause of

such vociferous lachrymation.

"What is the matter, Baboo?" began the

Commissioner in paternal tones. "Why are

you kicking up the shindy of such a deuce's

own hullabaloo?"[3]

"Because, honble Sir," responded Mr

Bhosh, "I am in lively expectation that

waters will rush in and extinguish my vital

spark."

"Pooh!" said Mr Commissioner, genially.

"This is only the moiety of a gale, and there

is not the slightest danger."

Having received this assurance, Mr Bhosh's

natural courage revived, and, coming up on

deck, he braved the tempest with the cool

composure of a cucumber, admonishing all

his fellow-passengers that they were not to

give way to panic, seeing that Death was

the common lot of all, and, though everyone

must die once, it was an experience that

could not be repeated, with much philosophy of

a similar kind which astonished many who had

falsely supposed him to be a pusillanimous.

The remainder of the voyage was uneventful,

and, soon after setting his feet on

British territory, Mr Bhosh became an alumnus

and undergraduate of the Alma Mater

of Cambridge.[4]

I shall not attempt to relate at any great

length the history of his collegiate career,

because, being myself a graduate of Calcutta

University, I am not, of course, proficient in

the customs and etiquettes of any rival seminaries,

and should probably make one or

two trivial slips which would instantly be

pounced upon and held up for derision by

carping critics.

So I shall content myself with mentioning

a few leading facts and incidents. Mr

Bhosh very soon wormed himself into the

good graces of his fellow college boys, and

his principal friend and fidus Achates was a

young high-spirited aristocrat entitled Lord

Jack Jolly, the only son of an earl who

had lately been promoted to the dignity of a

baronetcy.

Lord Jolly and Mr Bhosh were soon as

inseparable as a Dæmon and Pythoness, and,

though no nabob to wallow in filthy lucre,

Mr Bhosh gave frequent entertainments to

his friends, who were hugely delighted by[5]

the elegance of his hospitality and the garrulity

of his conversation.

Unfortunately the fame of these Barmecide

feasts soon penetrated the ears of the College

gurus, and Mr Bhosh's Moolovee sent for him

and severely reprimanded him for neglecting

to study for his Littlego degree, and squandering

his immense abilities and talents on mere

guzzling.

Whereupon Mr Bhosh shed tears of contrition,

embracing the feet of his senile tutor,

and promising that, if only he was restored

to favour he would become more diligent in

future.

And honourably did he fulfil this nudum

pactum, for he became a most exemplary bookworm,

burning his midnight candle at both

ends in the endeavour to cram his mind with

belles lettres.

But he was assailed by a temptation which

I cannot forbear to chronicle. One evening

as he was poring over his learned tomes, who

should arrive but a deputation of prominent[6]

Cambridge boatmen and athletics, to entreat him

to accept a stroke oar of the University eight

in the forthcoming race with Oxford College!

This, as all aquatics will agree, was no small

compliment—particularly to one who was so

totally unversed in wielding the flashing oar.

But the authorities had beheld him propelling

a punt boat with marvellous dexterity by dint

of a paddle, and, taking the length of his foot

on that occasion, they had divined a Hercules

and ardently desired him as a confederate.

Mr Bhosh was profoundly moved: "College

misters and friends," he said, "I welcome this

invitation with a joyful and thankful heart, as

an honour—not to this poor self, but to Young

India. Nevertheless, I am compelled by Dira

Necessitas to return the polite negative. Gladly

I would help you to inflict crushing defeat

upon our presumptuous foe, but 'I see a hand

you cannot see that beckons me away; I

hear a voice you cannot hear that wheezes

"Not to-day!"' In other words, gentlemen,

I am now actively engaged in the Titanic[7]

struggle to floor Littlego. It is glorious to

obtain a victory over Oxonian rivals, but,

misters, there is an enemy it is still more

glorious to pulverize, and that enemy is—one's

self!"

The deputation then withdrew with falling

crests, though unable to refrain from admiring

the firmness and fortitude which a mere Native

student had nilled an invitation which to most

European youths would have proved an irresistible

attraction.

Nor did they cherish any resentment against

Mr Bhosh, even when, in the famous inter-collegiate

race of that year from Hammersmith to

Putney, Cambridge was ingloriously bumped,

and Oxford won in a common canter.[8]

CHAPTER II

HOW MR BHOSH DELIVERED A DAMSEL FROM A DEMENTED COW

O Cow! in hours of mental ease

Thou chewest cuds beneath the trees;

But ah! when madness racks thy brow,

An awkward customer art thou!

Nature Poem furnished (to order) by young English Friend.

MR Bhosh's diligence at his books

was rewarded by getting through his

Little-go with such éclat that he was admitted

to become a baccalaureate, and further presented

with the greatest distinction the Vice-Chancellor

could bestow upon him, viz., the

title of a Wooden Spoon!

But here I must not omit to narrate a

somewhat startling catastrophe in which Mr

Bhosh figured as the god out of machinery.

It was on an afternoon before he went up[9]

to pass his Little-go exam, and, since all

work and no play is apt to render any Jack

a dull, he was recreating himself by a solitary

promenade in some fields in the vicinity of

Cambridge, when suddenly his startled ears

were dumbfounded to perceive the blood-curdling

sound of loud female vociferations!

On looking up from his reverie, he was

horrified by the spectacle of a young and

beauteous maiden being vehemently pursued

by an irate cow, whose reasoning faculties

were too obviously, in the words of Ophelia,

"like sweet bells bangled," or, in other words,

non compos mentis, and having rats in her

upper story!

The young lady, possessing the start and

also the advantage of superior juvenility, had

the precedence of the cow by several yards,

and attained the umbrageous shelter of a tree

stem, behind which she tremulously awaited

the arrival of her blood-thirsty antagonist.

As he noted her jewel-like eyes, profuse

hair, and panting bosom, Mr Bhosh's triangle[10]

of flesh[A] was instantaneously ignited by love

at first sight (the intelligent reader will

please understand that the foregoing refers

to the maiden and not at all to the cow,

which was of no excessive pulchritude—but

I am not to be responsible for the ambiguities

of the English language).

[A] Videlicet: his heart.

There was not a moment to be squandered;

Mr Bhosh had just time to recommend her

earnestly to remain in statu quo, before setting

off to run ventre à terre in the direction

whence he had come. The distracted animal,

abandoning the female in distress, immediately

commenced to hue-and-cry after our hero,

who was compelled to cast behind him his

collegiate cap, like tub to a whale.

The savage cow ruthlessly impaled the cap

on one of its horns, and then resumed the

chase.

Mr Bhosh scampered for his full value,

but, with all his incredible activity, he had

the misery of feeling his alternate heels

[11]scorched by the fiery snorts of the maniacal

quadruped.

Then he stripped from his shoulders his

student's robe, relinquishing it to the tender

mercies of his ruthless persecutress while he

nimbly surmounted a gate. The cow only

delayed sufficiently to rend the garment into

innumerable fragments, after which it cleared

the gate with a single hop, and renewed the

chase after Mr Bhosh's stern, till he was

forced to discard his ivory-headed umbrella

to the animal's destroying fury.

This enabled him to gain the walls of the

town and reach the bazaar, where the whole

population was in consternation at witnessing

such a shuddering race for life, and made

themselves conspicuous by their absence in

back streets.

Mr Bhosh, however, ran on undauntedly,

until, perceiving that the delirious creature

was irrevocably bent on running him to

earth, he took the flying leap into the

shop of a cheese merchant, where he cleverly[12]

entrenched himself behind the receipt of

custom.

With the headlong impetuosity of a distraught

the cow followed, and charged the

barrier with such insensate fury that her

horns and appertaining head were inextricably

imbedded in a large tub of margarine

butter.

At this our hero, judging that the wings

of his formidable foe were at last clipped,

sallied boldly forth, and, summoning a police-officer,

gave the animal into custody as a

disturber of the peace.

By such coolness and savoir faire in a

distressing emergency he acquired great kudos

in the eyes of all his fellow-students, who

regarded him as the conquering hero.

Alas and alack! when he repaired to the

field to receive the thanks and praises of the

maiden he had so fortunately delivered, he

had the mortification to discover that she had

vanished, and left not a wreck behind her!

Nor with all his endeavours could he so much

[13]as learn her name, condition, or whereabouts,

but the remembrance of her manifold charms

rendered him moonstruck with the tender

passion, and notwithstanding his success in

flooring the most difficult exams, his bosom's

lord sat tightly on its throne, and was not to

jump until he should again (if ever) confront

his mysterious fascinator.

GAVE THE ANIMAL INTO CUSTODY AS A DISTURBER OF THE PEACE

Having emerged from the shell of his statu

pupillari under the fostering warmth of his

Alma Mater, Mr Bhosh next proceeded as a

full-fledged B.A. to the Metropolis, and became

a candidate for forensic honours at one of the

legal temples, lodging under the elegant roof

of a matron who regarded him as her beloved

son for Rs. 21 per week, and attending lectures

with such assiduity that he soon acquired a

nodding acquaintance with every branch of

jurisprudence.

And when he went up for Bar Exam., he

displayed his phenomenal proficiency to such

an extent that the Lord Chancellor begged

him to accept one of the best seats on the[14]

Judges' bench, an honour which, to the best

of this deponent's knowledge and belief, has

seldom before been offered to a raw tyro, and

never, certainly, to a young Indian student.

However, with rare modesty Mr Bhosh

declined the offer, not considering himself

sufficiently ripe as yet to lay down laws, and

also desirous of gathering roses while he

might, and mixing himself in first-class English

societies.

I am painfully aware that such incidents

as the above will seem very mediocre and

humdrum to most readers, but I shall request

them to remember that no hero can achieve

anything very striking while he is still a

hobbardehoy, and that I cannot—like some

popular novelists—insult their intelligences

by concocting cock-and-bull occurrences which

the smallest exercise of ordinary commonsense

must show to be totally incredible.

By and bye, when I come to deal with Mr

Bhosh's experiences in the upper tenth of

London society, with which I may claim to[15]

have rather a profound familiarity, I will boldly

undertake that there shall be no lack of

excitement.

Therefore, have a little patience, indulgent

Misters![16]

CHAPTER III

THE INVOLUNTARY FASCINATOR

Please do not pester me with unwelcome attentions,

Since to respond I have no intentions!

Your Charms are deserving of honourable mentions—

But previous attachment compels these abstentions!

An unwilling Wooed to his Wooer."

Original unpublished Poem by H. B. J.

MR Bhosh was very soon enabled to

make his debût as a pleader, for the

Mooktears sent him briefs as thick as an

Autumn leaf in Vallambrosa, and, having on

one occasion to prosecute a youth who had

embezzled an elderly matron, Mr Bhosh's

eloquence and pathos melted the jury into a

flood of tears which procured the triumphant

acquittal of the prisoner.

But the bow of Achilles (which, as Poet

Homer informs us, was his only vulnerable[17]

point) must be untied occasionally, and accordingly

Mr Bhosh occasionally figured as

the gay dog in upper-class societies, and

was not long in winning a reputation in smart

circles as a champion bounder.

For he did greet those he met with a

pleasant, obsequious affability and familiarity,

which easily endeared him to all hearts. In

his appearance he would—but for a somewhat

mediocre stature and tendency to a precocious

obesity—have strikingly resembled the well-known

statuary of the Apollo Bellevue, and

he was in consequence inordinately admired

by aristocratic feminines, who were enthralled

by the fluency of his small talk, and competed

desperately for the honour of his company at

their "Afternoon-At-Home-Teas."

It was at one of these exclusive festivities

that he first met the Duchess Dickinson,

and (as we shall see hereafter) that meeting

took place in an evil-ominous hour for our

hero. As it happened, the honourable highborn

hostess proposed a certain cardgame[18]

known as "Penny Napkin," and fate decreed

that Mr Bhosh should sit contiguous to the

Duchess's Grace, who by lucky speculations

was the winner of incalculable riches.

But, hoity toity! what were his dismay

and horror, when he detected that by her

legerdemain in double-dealing she habitually

contrived to assign herself five pictured cards

of leading importance!

How to act in such an unprecedented

dilemma? As a chivalrous, it was repugnant to

him to accuse a Duchess of sharping at cards,

and yet at the same time he could not stake

his fortune against such a foregone conclusion!

So he very tactfully contrived by engaging

the Duchess's attention to substitute his card-hand

for hers, and thus effect the exchange

which is no robbery, and she, finally observing

his finesse, and struck by the delicacy with

which he had so unostentatiously rebuked her

duplicity, earnestly desired his further acquaintance.

For a time Mr Bhosh, doubtless obeying[19]

one of those supernatural and presentimental

monitions which were undreamt of in the

Horatian philosophy, resisted all her advances—but

alas! the hour arrived in which he

became as Simpson with Delilah.

It was at the very summit of the Season,

during a brilliantly fashionable ball at the

Ladbroke Hall, Archer Street, Bayswater,

whither all the élites of tiptop London Society

had congregated.

Mr Bhosh was present, but standing apart,

overcome with bashfulness at the paucity of

upper feminine apparel and designing to take

his premature hook, when the beauteous

Duchess in passing surreptitiously flung over

him a dainty nosehandkerchief deliciously

perfumed with extract of cherry blossoms.

With native penetration into feminine coquetries

he interpreted this as an intimation

that she desired to dance with him, and,

though not proficient in such exercises, he

made one or two revolutions round the room

with her co-operation, after which they retired[20]

to an alcove and ate raspberry ices and drank

lemonade. Mr Bhosh's sparkling tittle-tattle

completely achieved the Duchess's conquest,

for he possessed that magical gift of the gab

which inspired the tender passion without any

connivance on his own part.

And, although the Duchess was no longer

the chicken, having attained her thirtieth lustre,

she was splendidly well preserved; with huge

flashing eyes like searchlights in a face resembling

the full moon; of tall stature and

proportionate plumpness; most young men

would have been puffed out by pride at

obtaining such a tiptop admirer.

Not so our hero, whose manly heart was

totally monopolised by the image of the fair

unknown whom he had rescued at Cambridge

from the savage clutches of a horned cow, and

although, after receiving from the Duchess a

musk-scented postal card, requesting his company

on a certain evening, he decided to keep

the appointed tryst, it was only against his

will and after heaving many sighs.[21]

On reaching the Duchess's palace, which

was situated in Pembridge Square, Bayswater,

he had the mortification to perceive that he

was by no means the only guest, since the

reception halls were thickly populated by

gilded worldlings. But the Duchess advanced

to greet him in a very kind, effusive manner,

and, intimating that it was impossible to converse

with comfort in such a crowd, she led

him to a small side-room, where she seated

him on a couch by her side and invited him to

discourse.

Mr Bhosh discoursed accordingly, paying

her several high-flown compliments by which

she appeared immoderately pleased, and discoursed

in her turn of instinctive sympathies,

until our hero was wriggling like an eel with

embarrassment at what she was to say next,

and at this point Duke Dickinson suddenly

entered and reminded his spouse in rather

abrupt fashion that she was neglecting her

remaining guests.

After the Duchess's departure, Mr Bhosh,[22]

with the feelings of an innate gentleman, felt

constrained to make his sincere apologies to

his ducal entertainer for having so engrossed

his better half, frankly explaining that she had

exhibited such a marked preference for his

society that he had been deprived of all

option in the matter, further assuring his

dukeship that he by no means reciprocated

the lady's sentiments, and delicately recommending

that he was to keep a rather more

lynxlike eye in future upon her proceedings.

To which the Duke, greatly agitated, replied

that he was unspeakably obliged for the caution,

and requested Mr Bhosh to depart at once and

remain an absentee for the future. Which our

friend cheerfully undertook to perform, and, in

taking leave of the Duchess, exhorted her, with

an eloquence that moved all present, to abandon

her frivolities and levities and adopt a deportment

more becoming to her matronly exterior.

The reader would naturally imagine that she

would have been grateful for so friendly and

well-meant a hint—but oh, dear! it was quite[23]

the reverse, for from a loving friend she was

transformed into a bitter and most unscrupulous

enemy, as we shall find in forthcoming chapters.

Truly it is not possible to fathom the perversities

of the feminine disposition![24]

CHAPTER IV

A KICK FROM A FRIENDLY FOOT

She is a radiant damsel with features fair and fine;

But since betrothed to Bosom's friend she never can be mine!

Original Poem by H. B. J. (unpublished).

MR Bhosh's bosom-friend, the Lord

Jack Jolly, had kindly undertaken to

officiate as his Palinurus and steer him safely

from the Scylla to the Charybdis of the

London Season, and one day Lord Jolly

arrived at our hero's apartments as the bearer

of an invite from his honble parent the Baronet,

to partake of tiffin at their ancestral abode in

Chepstow Villas, which Bindabun gratefully

accepted.

Arrived at the Jollies' sumptuous interior, a

numerous retinue of pampered menials and

gilded flunkies divested Mr Bhosh of his hat[25]

and umbrella and ushered him into the hall of

audience.

"Bhosh, my dear old pal," said Lord Jack,

"I have news for you. I am engaged as a

Benedict, and am shortly to celebrate matrimony

with a young goodlooking female—the

Princess Petunia Jones."

"My lord," replied Mr Bhosh, "suffer me

to hang around your patrician neck the floral

garland of my humble congratulations."

"My dear Bhosh," responded the youthful

peer of the realm, "I regard you as more than

a brother, and am confident that when my

betrothed beholds your countenance, she will

conceive for you a similar lively affection. But

hush! here she comes to answer for herself....

Princess, permit me to present to you the

best and finest friend I possess, Mr Bindabun

Bhosh."

Mr Bhosh modestly lowered his optics as

he salaamed with inimitable grace, and it was

not until he had resumed his perpendicular that

he recognised in the Princess Jones the charming[26]

unknown whom he had last beheld engaged

in repelling the assault of a distracted cow!

Their eyes were no sooner crossed than he

knew that she regarded him as her deliverer,

and was consumed by the most ardent affection

for him. But Mr Bhosh repressed himself with

heroic magnanimity, for he reflected that she

was the affianced of his dearest friend and that

it was contrary to bon ton to poach another's

jam.

So he merely said; "How do you do? It

is a very fine day. I am delighted to make

your acquaintance," and turning on his heels

with a profound curtsey, he left her flabbergasted

with mortification.

But those only who have compressed their

souls in the shoe of self-sacrifice know how

devilishly it pinches, and Mr Bhosh's grief

was so acute that he rolled incessantly on his

couch while the radiant image of his divinity

danced tantalisingly before his bloodshot

vision.

Eventually he became calmer, and after[27]

plunging his fervid body into a foot-bath, he

showed himself once more in society, assuming

an air of meretricious waggishness to conceal

the worm that was busily cankering his

internals, and so successful was he that Lord

Jack was entirely deceived by his vis comica,

and invited him to spend the Autumn up the

country with his respectable parents.

Mr Bhosh accepted—but when he knew

that Princess Petunia was also to be one of the

amis de la maison, he was greatly concerned at

the prospect of infallibly reviving her love by

his propinquity, and thereby inflicting the cup

of calamity on his best friend. Willingly

would he have imparted the whole truth to his

Lordship and counselled him to postpone the

Princess's visit until he, himself, should have

departed—but, ah me! with all his virtue he

was not a Roman Palladium that he should

resist the delight of philandery with the

radiant queen of his soul. So he kept his

tongue in his cheek.

However, when they met in the ancient and[28]

rural castle he constrained himself, in conversing

with her, to enlarge enthusiastically upon the

excellences of Lord Jack. "What a good,

ripping, gentlemanly fellow he was, and how

certain to make a best quality husband!"

Princess Jones listened to these encomiums with

tender sighing, while her soft large orbs rested

on Mr Bhosh with ever-increasing admiration.

No one noticed how, after these elephantine

efforts at self-denial, he would silently slip

away and weep salt and bitter tears as he

weltered dolefully on a doormat; nor was it

perceived that the Princess herself was become

thin as a weasel with disappointed love.

Being the ardent sportsman, Mr Bhosh

sought to drown his sorrow with pleasures of

the chase.

He would sally forth alone, with no other

armament than a breechloading rifle, and

endeavour to slay the wild rabbits which

infested the Baronet's domains, and sometimes

he had the good fortune to slaughter one or

two. Or he would take a Rod and hooks and a

few worms, and angle for salmons; or else he

would stalk partridges, and once he even

assisted in a foxhunt, when he easily outstripped

all the dogs and singly confronted

Master Reynard, who had turned to bay

savagely at his nose. But Bindabun undauntedly

descended from his horse, and,

drawing his hunting dagger, so dismayed the

beast by his determined and ferocious aspect

that it turned its tail and fled into some other

part of the country, which earned him the

heartfelt thanks from his fellow Nimrods.

DISMAYED THE BEAST BY HIS DETERMINED AND FEROCIOUS ASPECT

Naturally, such feats of arms as these only

served to inflame the ardour of the Princess,

to whom it was a constant wonderment that

Mr Bhosh did never, even in the most roundabout

style, allude to the fact that he had

saved her life from perishing miserably on the

pointed horn of an enraged cow.

She could not understand that the Native

temperament is too sheepishly modest to flaunt

its deeds of heroism.

Those who are au fait in knowledge of the

world are aware that when there are combustibles

concealed in any domestic interior, there

is always a person sooner or later who will

contrive to blow them off; and here, too, the

Serpent of Mischief was waiting to step in with

cloven hoof and play the very deuce.

It so happened that the Duchess occupied

the adjacent bungalow to that of Baronet Jolly

and his lady, with whom she was hail-fellow-well-met,

and this perfidious female set herself

to ensnare the confidence of the young and

innocent Princess by discreetly lauding the

praises of Mr Bhosh.

"What an admirable Indian Crichton!

How many rabbits and salmons had he laid

low that week? Truly, she regarded him as

a favourite son, and marvelled that any youthful

feminine could prefer an ordinary peer like

Lord Jolly to a Native paragon who was not

only a university B.A., but had successfully

passed Bar Exam!" and so forth and so on.

The princess readily fell into this insidious

booby-trap, and confessed the violence of her

attachment, and how she had striven to acquaint

Mr Bhosh with her sentiments but was rendered

inarticulate by maidenly bashfulness.

"Can you not then slip a love-letter into his

hand?" inquired the Duchess.

"Cui bono?" responded the Princess, sadly.

"Seeing that he never approaches near enough

to me to receive such a missive, and I dare

not entrust it to one of my maidens!"

"Why not to Me?" said the Duchess. "He

will not refuse it coming from myself; moreover,

I have influence over him and will soften

his heart towards thee."

Accordingly the Princess indicted a rather

impassioned love-letter, in which she assured

Mr Bhosh that she had divined his secret

passion and fully reciprocated it, also that she

was the total indifferent to Lord Jack, with

much other similar matters.

Having obtained possession of this litera

scripta, what does the unscrupulous Duchess

next but deliver it impromptu into the hands

of Lord Jack, who, after perusing it, was

overcome by uncontrollable wrath and instantaneously

summoned our hero to his presence.

Here was the pretty kettle of fish—but

I must reserve the sequel for the next

chapter.

[29]

CHAPTER V

THE DUEL TO THE DEATH

The ordinary valour only works

At those rare intervals when peril lurks;

There is a courage, scarcer far, and stranger,

Which nothing can intimidate but danger.

Original Stanza by H. B. J.

NO sooner had Mr Bhosh obeyed the

summons of Lord Jack, than the latter

not only violently reproached him for having

embezzled the heart of his chosen bride, but

inflicted upon him sundry severe kicks from

behind, barbarously threatening to encore the

proceeding unless Chunder instantaneously

agreed to meet him in a mortal combat.

Our hero, though grievously hurt, did not

abandon his presence of mind in his tight

fix. Seating himself upon a divan, so as to

obviate any repetition of such treatment, he[34]

thus addressed his former friend: "My dear

Jack, Plato observes that anger is an abbreviated

form of insanity. Do not let us fall

out about so mere a trifle, since one friend is

the equivalent of many females. Is it my

fault that feminines overwhelm me with unsought

affections? Let us both remember

that we are men of the world, and if you on

your side will overlook the fact that I have unwittingly

fascinated your fiancée, I, on mine,

am ready to forget my unmerciful kickings."

But Lord Jolly violently rejected such a

give-and-take compromise, and again declared

that if Mr Bhosh declined to fight he was to

receive further kicks. Upon this Chunder

demanded time for reflection; he was no

bellicose, but he reasoned thus with his soul:

"It is not certain that a bullet will hit—whereas,

it is impossible for a kick to miss

its mark."

So, weeping to find himself between a deep

sea and the devil of a kicking, he accepted

the challenge, feeling like Imperial Cæsar,[35]

when he found himself compelled to climb

up a rubicon after having burnt his boots!

Being naturally reluctant to kick his brimming

bucket of life while still a lusty juvenile,

Mr Bhosh was occupied in lamenting the injudiciousness

of Providence when he was most

unexpectedly relieved by the entrance of his

lady-love, the Princess Jones, who, having

heard that her letter had fallen into Lord

Jack's hands, and that a sanguinary encounter

would shortly transpire, had cast off every

rag of maidenly propriety, and sought a clandestine

interview.

She brought Bindabun the gratifying intelligence

that she was a persona grata with

his lordship's seconder, Mr Bodgers, who was

to load the deadly weapons, and who, at her

request, had promised to do so with cartridges

from which the bullets had previously been

bereft.

Such a piece of good news so enlivened

Mr Bhosh, that he immediately recovered his

usual serenity, and astounded all by his perfect[36]

nonchalance. It was arranged that the tragical

affair should come off in the back garden of

Baronet Jolly's castle, immediately after breakfast,

in the presence of a few select friends

and neighbours, among whom—needless to say—was

Princess Petunia, whose lamp-like optics

beamed encouragement to her Indian champion,

and the Duchess of Dickinson, who was

now the freehold tenement of those fiendish

Siamese twins—Malice and Jealousy. At

breakfast, Mr Bhosh partook freely of all

the dishes, and rallied his antagonist for

declining another fowl-egg, rather wittily suggesting

that he was becoming a chicken-hearted.

The company then adjourned to

the garden, and all who were non-combatants

took up positions as far outside the zone of

fire as possible.

Mr Bhosh was rejoiced to receive from

the above-mentioned Mr Bodgers a secret

intimation that it was the put-up job, and

little piece of allright, which emboldened

him to make the rather spirited proposal[37]

to his lordship, that they were to fire—not

at the distance of one hundred paces, as

originally suggested—but across the more

restricted space of a nosekerchief. This

dare-devilish proposal occasioned a universal

outcry of horror and admiration; Mr Bhosh's

seconder, a young poor-hearted chap, entreated

him to renounce his plan of campaign, while

Lord Jack and Mr Bodgers protested that

it was downright tomfolly.

Chunder, however, remained game to his

backbone. "If," he ironically said, "my

honble friend prefers to admit that he is inferior

in physical courage to a native Indian

who is commonly accredited with a funky

heart, let him apologise. Otherwise, as a

challenged, I am the Master of the Ceremonies.

I do not insist upon the exchange

of more than one shoot—but it is the sine

quâ non that such shoot is to take place

across a nosewipe."

Upon which his lordship became green as

grass with apprehensiveness, being unaware[38]

that the cartridges had been carefully sterilised,

but glueing his courage to the sticky point,

he said, "Be it so, you bloodthirsty little

beggar—and may your gore be on your own

knob!"

"It is always barely possible," retorted Mr

Bhosh, "that we may both miss the target!"

And he made a secret motion to Mr Bodgers

with his superior eyeshutter, intimating that

he was to remember to omit the bullets.

But lackadaisy! as Poet Burns sings, the

best-laid schemes both of men and in the

mouse department are liable to gang aft—and

so it was in the present instance, for

Duchess Dickinson intercepted Chunder Bindabun's

wink and, with the diabolical intuition

of a feminine, divined the presence of a rather

suspicious rat. Accordingly, on the diaphanous

pretext that Mr Bodgers was looking

faintish and callow, she insisted on applying

a very large smelling-jar to his nasal organ.

Whether the vessel was charged with salts

of superhuman potency, or some narcotic drug,[39]

I am not to inquire—but the result was that,

after a period of prolonged sternutation, Mr

Bodgers became impercipient on a bed of

geraniums.

Thereupon Chunder, perceiving that he had

lost his friend in court, magnanimously said:

"I cannot fight an antagonist who is unprovided

with a seconder, and will wait until

Mr Bodgers is recuperated." But the honourable

and diabolical duchess nipped this arrangement

in the bud. "It would be a pity,"

said she, "that Mr Bhosh's fiery ardour should

be cooled by delay. I am capable to load a

firearm, and will act as Lord Jolly's seconder."

Our hero took the objection that, as a feminine

was not legally qualified to act as seconder

in mortal combats, the duel would be rendered

null and void, and appealed to his own seconder

to confirm this obiter dictum.

Unluckily the latter was a poor beetlehead

who was in excessive fear of offending the

Duchess, and gave it as his opinion that sex

was no disqualification, and that the Duchess[40]

of Dickinson was fully competent to load the

lethal weapons, provided that she knew how.

Whereupon she, regarding Mr Bhosh with

the malignant simper of a fiend, did not only

deliberately fill each pistol-barrel with a bullet

from her own reticule bag, but also had the

additional diablerie to extract a miniature laced

mouchoir exquisitely perfumed with cherry-blossoms,

and to say, "Please fire across this.

I am confident that it will bring you good

luck."

And Mr Bhosh recognised with emotions

that baffle description the very counterpart

of the nose-handkerchief which she had flung

at him months previously at the aforesaid

fashionable Bayswater Ball! Now was our

poor miserable hero indeed up the tree of

embarrassment—and there I must leave him

till the next chapter.[41]

CHAPTER VI

LORD JOLLY IS SATISFIED

Ah, why should two, who once were bosom's friends,

Present at one another pistol ends?

Till one pops off to dwell in Death's Abode—

All on account of Honour's so-called code!

Thoughts on Duelling, by H. B. J.

MANY a more hackneyed duellist than

our unfortunate friend Bhosh might

well have been frightened from his propriety

at the prospect of fighting with genuine bullets

across so undersized a nosekerchief as that

which the Duchess had furnished for the fray.

But Mr Bhosh preserved his head in perfect

coolness: "It is indisputably true," he said,

"that I proposed to shoot across a pocketkerchief—but

I am not an effeminate female

that I should employ such a lacelike and flimsy

concern as this! As a challenged, I claim my[42]

constitutional right under Magna Charta to

provide my own nosewipe."

And, as even my Lord Jack admitted that

this was legally correct, Mr Bhosh produced

a very large handsome nosekerchief in parti-coloured

silks.

This he tore into narrow strips, the ends of

which he tied together in such a manner that

the whole was elongated to an incredible length.

Then, tossing one extremity to his lordship,

and retaining the other in his own hand, he

said: "We will fight, if you please, across this—or

not at all!"

Which caused a working majority of the

company, and even Lord Jack Jolly himself,

to burst into enthusiastic plaudits of the ingenuity

and dexterity with which Mr Bhosh

had contrived to extricate himself from the

prongs of his Caudine fork.

The Duchess, however, was knitting her

brows into the baleful pattern of a scowl—for

she knew as well as Chunder Bindabun

himself that no human pistol was capable

[43]to achieve such a distance! The duel commenced.

His lordship and Mr Bhosh each

removed their upper clothings, bared their

arms, and, taking up a weapon, awaited the

momentous command to fire.

THE BULLET HAD PERFORATED A LARGE CIRCULAR ORIFICE IN HONBLE BODGER'S HAT

It was pronounced, and Lord Jolly's pistol

was the first to ring the ambient welkin with

its horrid bang. The deadly missile, whistling

as it went for want of thought, entered the

door of a neighbouring pigeon's house and

fluttered the dovecot confoundedly.

Mr Bhosh reserved his fire for the duration

of two or three harrowing seconds. Then he,

too, pulled off his trigger, and after the

explosion there was a loud cry of dismay.

The bullet had perforated a large circular

orifice in Honble Bodger's hat, who, by this

time, had returned to self-consciousness!

"I could not bring myself to snuff the candle

of your honble lordship's existence," said Mr

Bhosh, bowing, "but I wished to convince all

present that I am not incompetent to hit a

mark."[44]

And he proceeded to assure Mr Bodger that

he was to receive full compensation for any

moral and intellectual damage done to his said

hat.

As for his lordship, he was so overcome by

Mr Bhosh's unprecedented magnanimity that

he shed copious tears, and, warmly embracing

his former friend, entreated his forgiveness,

vowing that in future their affection should

never again be endangered by so paltry and

trivial a cause as the ficklety of a feminine.

Moreover, he bestowed upon Bindabun the

blushing hand of Princess Jones, and very

heartily wished him joy of her.

Now the Princess was the solitary brat of a

very wealthy merchant prince, Honble Sir

Monarch Jones, whose proud and palatial

storehouses were situated in the most fashionable

part of Camden Town.

Sir Jones, in spite of Lord Jack's resignation,

did not at first regard Mr Bhosh with the

paternal eye of approval, but rather advanced

the objection that the colour of his money was[45]

practically invisible. "My daughter," he said

haughtily, "is to have a lakh of rupees on her

nuptials. Have you a lakh of rupees?"

Bindabun was tempted to make the rather

facetious reply that he had, indeed, a lack of

rupees at the present moment.

Sir Monarch, however, like too many English

gentlemen, was totally incapable of comprehending

the simplest Indian jeu des mots, and

merely replied. "Unless you can show me

your lakh of rupees, you cannot become my

beloved son-in-law."

So, as Mr Bhosh was a confirmed impecunious,

he departed in severe despondency.

However, fortune favoured him, as always, for

he made the acquaintance of a certain Jewish-Scotch,

whose cognomen was Alexander

Wallace McAlpine, and who kindly undertook

to lend him a lakh of rupees for two days at

interest which was the mere bite of a flea.

Having thus acquired the root of all evil,

Bindabun took it in a four-wheeled cab and

triumphantly exhibited his hard cash to Sir[46]

Jones, who, being unaware that it was borrowed

plumage, readily consented that he should

marry his daughter. After which Mr Bhosh

honourably restored the lakh to the accommodating

Scotch minus the interest, which he

found it inconvenient to pay just then.

I am under great apprehensions that my

gentle readers, on reading thus far and no

further, will remark: "Oho! then we are

already at the finis, seeing that when a hero

and heroine are once booked for connubial

bliss, their further proceedings are of very

mediocre interest!"

Let me venture upon the respectful caution

that every cup possesses a proverbially slippery

lip, and that they are by no means to take it as

granted that Mr Bhosh is so soon married and

done for.

Remember that he still possesses a rather

formidable enemy in Duchess Dickinson, who

is irrevocably determined to insert a spike in

his wheel of fortune. For a woman is so

constituted that she can never forgive an[47]

individual who has once treated her advances

with contempt, no matter how good-humoured

such contempt may have been. No, misters,

if you offend a feminine you must look out for

her squalls.

Readers are humbly requested not to toss

this fine story aside under the impression that

they have exhausted the cream in its cocoanut.

There are many many incidents to come of

highly startling and sensational character.[48]

CHAPTER VII

THE ADVENTURE OF THE UNWIELDY GIFTHORSE

When dormant lightning is pent in the polished hoofs of a colt,

And his neck is clothed with thunder,—then, horseman, beware of the bolt!

From the Persian, by H. B. J.

IN accordance with English usages, Mr

Bhosh, being now officially engaged to

the fair Princess Jones, did dance daily

attendance in her company, and, she being

passionately fond of equitation, he was compelled

himself to become the Centaur and

act as her cavalier servant on a nag which

was furnished throughout by a West End

livery jobber. Fortunately, he displayed such

marvellous dexterity and skill as an equestrian

that he did not once sustain a single reverse!

Truly, it was a glorious and noble sight to[49]

behold Bindabun clinging with imperturbable

calmness to the saddle of his steed, as it

ambled and gamboled in so spirited a manner

that all the fashionables made sure that he

was inevitably to slide over its tail quarters!

But invariably he returned, having suffered

no further inconvenience than the bereavement

of his tall hat, and the heart of Princess

Petunia was uplifted with pride when she

saw that her betrothed, in addition to being

a B.A. and barrister-at-law, was also such a

rough rider.

It is de rigueur in all civilised societies to

encourage matrimony by bestowing rewards

upon those who are about to come up to the

scratch of such holy estate, and consequently

splendid gifts of carriage, timepieces, tea-caddies,

slices of fish, jewels, blotter-cases,

biscuit-caskets, cigar-lights, and pin-cushions

were poured forth upon Mr Bhosh and his

partner, as if from the inexhaustibly bountiful

horn of a Pharmacopœia.

Last, but not least, one morning appeared[50]

a saice leading an unwieldy steed of the complexion

of a chestnut, and bearing an anonymously-signed

paper, stating that said horse

was a connubial gift to Mr Bhosh from a

perfervid admirer.

Our friend Bindabun was like to throw his

bonnet over the mills with excessive joy, and

could not be persuaded to rest until he had

made a trial trip on his gifted horse, while

the amiable Princess readily consented to

become his companion.

So, on a balmy and luscious afternoon in

Spring, when the mellifluous blackbirds,

sparrows, and other fowls of that ilk were

engaged in billing and cooing on the foliage

of innumerable trees and bushes, and the

blooming flowers were blowing proudly on

their polychromatic beds, Mr Bhosh made the

ascension of his gift-horse, and titupped by

the side of his betrothed into the Row, the

observed of all the observing masculine and

feminine smarties.

But, hoity-toity! he had not titupped very

[51]many yards when the unwieldy steed came

prematurely to a halt and adopted an unruly

deportment. Mr Bhosh inflicted corporal

punishment upon its loins with a golden-headed

whip, at which the rebellious beast

erected itself upon its hinder legs until it

was practically a biped.

THE CANTANKEROUS STEED EXECUTED A LEAP WITH ASTOUNDING AGILITY

Bindabun, although at the extremity of his

wits to preserve his saddle by his firm hold

on the bridle-rein, undauntedly aimed a swishing

blow at the head and front of the offending

animal, which instantaneously returned its

forelegs to terra firma, but elevated its latter

end to such a degree that our hero very

narrowly escaped sliding over its neck by

cleverly clutching the saddleback.

Next, the cantankerous steed executed a

leap with astounding agility, arching its back

like a bow, and propelling our poor friend

into the air like the arrow, though by providential

luck and management on his part

he descended safely into his seat after every

repetition of this dangerous manœuvre.[52]

All things, however, must come to an end

at some time, and the unwieldy quadruped at

last became weary of leaping and, securing

the complete control of his bit, did a bolt

from the blue.

Willy nilly was Mr Bhosh compelled to

accompany it upon its mad, unbridled career,

while all witnesses freely hazarded the conjecture

that his abduction would be rather

speedily terminated by his being left behind,

and I will presume to maintain that a less

practical horseman would long before have

become an ordinary pedestrian.

But Bindabun, although both stirrupholes

were untenanted, and he was compelled to

hold on to his steed's mane by his teeth and

nails, nevertheless remained triumphantly in

the ascendant.

On, on he rushed, making the entire circumference

of the Park in his wild, delirious

canter, and when the galloping horse once

more reappeared, and Mr Bhosh was perceived

to be still snug on his saddle, the[53]

spectators were unable to refrain from heartfelt

joy.

A second time the incorrigible courser

careered round the Park on his thundering

great hoofs, and still our heroic friend preserved

his equilibrium—but, heigh-ho! I

have to sorrowfully relate that, on his third

circuit, it was the different pair of shoes—for

the headstrong animal, abstaining from

motion in a rather too abrupt manner, propelled

Mr Bhosh over its head with excessive

velocity into the elegant interior of a victoria-carriage.

He alighted upon a great dame who had

maliciously been enjoying the spectacle of his

predicament, but who now was forced to

experience the crushing repartee of his tu

quoque, for such a forcible collision with his

person caused her not only two blackened

optics but irremediable damage to the leather

of her nose.

The pristine beauty of her features was

irrecoverably dismantled, while Mr Bhosh[54]—thanks

to his landing on such soft and yielding

material—remained intact and able to return

to his domicile in a fourwheeled cab.

Beloved reader, however sceptical thou

mayest be, thou wilt infallibly admire with

me the inscrutable workings of Nemesis, when

thou learnest that the aforesaid great lady

was no other than the Duchess of Dickinson,

and (what is still more wonderful) that it was

she who had insidiously presented him with

such a fearful gift of the Danaides as an

obstreperous and unwieldy steed!

Truly, as poet Shakespeare sagaciously

observes, there is a divinity that rough-hews

our ends, however we may endeavour to

preserve their shapeliness![55]

CHAPTER VIII

A RIGHTABOUT FACER FOR MR BHOSH

Halloo! at a sudden your love warfare is changed!

Your dress is changed! Your address is changed!

Your express is changed! Your mistress is changed!

Halloo! at a sudden your funny fair is changed!

A song sung by Messengeress Binda before Krishnagee

Dr. Ram Kinoo Dutt (of Chittagong).

THOSE who are au faits in the tortoise

involutions of the feminine disposition

will hear without astonishment that Duchess

Dickinson—so far from being chastened and

softened by the circumstance that the curse

she had launched at Mr Bhosh's head had

returned, like an illominous raven, to roost

upon her own nose and irreparably destroy

its contour—was only the more bitterly

incensed against him.[56]

Instead of interring the hatchet that had

flown back, as if it were that fabulous volatile

the boomerang, she was in a greater stew than

ever, and resolved to leave no stone unturned

to trip him up. But what trick to play, seeing

that all the honours were in Mr Bhosh's hands?

She could not officiate as Marplot to discredit

him in the affections of his ladylove,

since the Princess was too severely enamoured

to give the loan of her ear to any sibillations

from a snake in grass.

How else, then, to hinder his match? At

this she was seized with an idea worthy of

Maccaroni himself. She paid a complimentary

visit to the Princess, arrayed in the sheepish

garb of a friend, and contrived to lure the

conversation on to the vexed question of

prying into futurity.

Surely, she artfully suggested, the Princess

at such a momentous epoch of her existence

had, of course, not neglected the sensible

precaution of consulting some competent

soothsayer respecting the most propitious day[57]

for her nuptials with the accomplished Mr

Bhosh?...

What, had she omitted to pop so important

a question? How incredibly harebrained!

Fortunately, there was yet time to do the

needful, and she herself would gladly volunteer

to accompany the Princess on such an

errand.

Princess Petunia fell a ready victim into the

jaws of this diabolical booby-trap and inquired

the address and name of the cleverest necromancer,

for it is matter of notoriety that

London ladies are quite as superstitious and

addicted to working the oracle as their native

Indian sisters.

The Duchess replied that the Astrologer-Royal

was a facile princeps at uttering a

prediction, and accordingly on the very next

day she and the Princess, after disguising

themselves, set forth on the summit of a

tramway 'bus to the Observatory Temple of

Greenwich, where, after first propitiating the

prophet by offerings, they were ushered into a[58]

darkened inner chamber. Although they were

strictly pseudo, he at once informed them of

their genuine cognomens, and also told them

much concerning their past of which they had

hitherto been ignorant.

And to the Princess he said, stroking the

long and silvery hairs of his beard, "My

daughter, I foresee many calamities which will

inevitably befall thee shouldest thou marry

before the day on which the bridegroom wins

a certain contest called the Derby with a horse

of his own."

The gentle Petunia departed melancholy as

a gib cat, since Mr Bhosh was not the happy

possessor of so much as a single racing-horse

of any description, and it was therefore not

feasible that he should become entitled to wear

the cordon bleu of the turf in his buttonhole on

his wedding day!

With many sighs and tears she imparted her

piece of news to the horror-stricken ears of our

hero, who earnestly assured her that it was

contrary to commonsense and bonos mores, to

[59]attach any importance to the mere ipse dixit of

so antiquated a charlatan as the Astrologer-Royal,

who was utterly incapable—except at

very long intervals—to bring about even such

a simple affair as an eclipse which was visible

from his own Observatory!

'MY DAUGHTER, I FORESEE MANY CALAMITIES WHICH WILL INEVITABLY BEFALL THEE'

However, the Princess, being a feminine,

was naturally more prone to puerile credulities,

and very solemnly declared that nothing would

induce her to kneel by Mr Bhosh's side at the

torch of Hymen until he should first have

distinguished himself as a Derby winner.

Whereat Mr Bhosh, perceiving that the date

of his nuptial ceremony was become a dies non

in a Grecian calendar, did wring his hands in

a bath of tears.

Alas! he was totally unaware that it was his

implacable enemy, the Duchess Dickinson, who

had thus upset his apple-cart of felicity—but so

it was, for by a clandestine bribe, she had

corrupted the Astrologer-Royal—a poor, weak,

very avaricious old chap—to trump out such a

disastrous prediction.[60]

Some heroes in this hard plight would have

thrown up the leek, but Mr Bhosh was stuffed

with sterner materials. He swore a very long

oath by all the gods that he had ceased to

believe in, that sooner or later, by crook or

hook, he would win the Derby race, though

entirely destitute of horseflesh and very ill

able to afford to purchase the most mediocre

quadruped.

Here some sporting readers will probably

object! Why could he not enlist his unwieldy

gifthorse among Derby candidates and so

hoist the Duchess on the pinnacle of her own

petard?

To which I reply: Too clever by halves,

Misters! Imprimis, the steed in question was

of far too ferocious a temperament (though

undeniably swift-footed) ever to become a

favourite with Derby judges; secondly, after

dismounting Mr Bhosh, it had again taken to

its heels and departed into the Unknown, nor

had Mr Bhosh troubled himself to ascertain its

private address.[61]

But fortune favours the brave. It happened

that Mr Bhosh was one day promenading down

the Bayswater Road when he was passed by a

white horse drawing a milk chariot with unparalleled

velocity, outstripping omnibuses,

waggons, and even butcher-carts in its wind-like

progress, which was unguided by any

restraining hand, for the milk-charioteer himself

was pursuing on foot.

His natural puissance in equine affairs

enabled Mr Bhosh to infer that the steed

which could cut such a record when handicapped

with a cumbrous dairy chariot would

exhibit even greater speed if in puris naturalibus,

and that it might even not improbably

carry off first prize in the Derby race.

So, as the milk-charioteer ran up, overblown

with anxiety, to learn the result of his horse's

escapade, Mr Bhosh stopped him to inquire

what he would take for such an animal.

The dairy-vendor, rather foolishly taking it

for granted that horse and cart were gone

concerns, thought he was making the good[62]

stroke of business in offering the lot for a

twenty-pound note.

"I have done with you!" cried Mr Bhosh

sharply, handing over the purchase-money,

which he very fortunately chanced to have

about him, and galloping off to inspect his

bargain, which was like buying a pig after

once poking it in the ribs.

In what condition he found it I must leave

you to learn, my dear readers, in an ensuing

chapter.[63]

CHAPTER IX

THE DARK HORSE

Full many a mare with coat of milkiest sheen,

Is dyed in dark unfathomed coal mines drab;

Full many a flyer's born to blush unseen,

And waste her swiftness on a hansom cab.

Lines to order by a young English friend, who swears they

are original. But I regard them as an unconscious

plagiarism from Poet Young's "Eulogy of a Country

Cemetery." H. B. J.

It is a gain, a precious, let me gain! let me gain!

Oh, Potentate! Oh, Potentate!

The shower of thine secret shoe-dust

Oh, Potentate! Oh, Potentate!

Dr. Ram Kinoo Dutt (of Chittagong).

WE left Mr Bhosh in full pursuit of

the runaway horse and milk-chariot

which he had so spiritedly purchased while

still en route. After running a mile or two,

he was unspeakably rejoiced to find that the

equipage had automatically come to a standstill[64]

and was still in prime condition—with

the exception of the lacteal fluid, which had

made its escape from the pails.

Bindabun, however, was not disposed to

weep for long over spilt milk, and had the

excessive magnanimity to restore the chariot

and pails to the dairy merchant, who was

beside himself with gratitude.

Then, Mr Bhosh, with a joyful heart,

having detached his purchase from the shafts,

conducted it in triumph to his domicile. It

turned out to be a mare, white as snow and

of marvellous amiability; and, partly because

of her origin, and partly from her complexion,

he christened her by the appellation of

Milky Way.

Although perforce a complete ignoramus

in the art of educating a horse to win any

equine contest, Mr Bhosh's nude commonsense

told him that the first step was to

fatten his rather too filamentous pupil with

corn and similar seeds, and after a prolonged

course of beanfeasts he had the gratification[65]

to behold his mare filling out as plump as a

dumpling.

As he desired her to remain the dark

horse as long as possible, he concealed her

in a small toolshed at the end of the garden,

ministering to her wants with his own hands,

and conducting her for daily nocturnal constitutionals

several times round the central

grass-patch.

For some time he refrained from mounting—"fain

would he climb but that he feared to

fall," as Poet Bunyan once scratched with a

diamond on Queen Anne's window; but at

length, reflecting that if nothing ventures

nothing is certain to win, he purchased a

padded saddle with appendages, and surmounted

Milky Way, who, far from regarding

him as an interloper, appeared gratified

by his arrival, and did her utmost to make

him feel thoroughly at home.

The next step was, of course, to obtain

permission from the pundits who rule the

roast of the Jockey Club, that Milky Way[66]

might be allowed to compete in the approaching

Derby.

Now this was a more delicately ticklish

matter than might be supposed, owing to the

circumstance that the said pundits are such

warm men, and so well endowed with this

world's riches that they are practically non-corruptible.

Fortunately, Mr Bhosh, as a dabster in

English composition, was a pastmaster in

drawing a petition, and, sitting down, he

constructed the following:—

To Those Most Worshipful Bigheads In control of Jockeys Club.

Benign Personages!

This Petition humbly sheweth:

- That your Petitioner is a native Indian Cambridge B.A., a

Barrister-at-law, and a most loyal and devoted subject of Her

Majesty the Queen-Empress. - That it is of excessive importance to him, for private[67]

reasons, that he should win a Derby Race. - That such a famous victory would be eminently popular with all

classes of Indian natives, and inordinately increase their affection

for British rule. - That for some time past your Petitioner has been diligently

training a quadruped which he fondly hopes may gain a victory. - That said quadruped is a member of the fair sex.

- That she is a female horse of very docile disposition, but,

being only recently extracted from shafts of dairy chariot, is a

total neophyte in Derby racing. - That your lordships may direct that she is to be kindly

permitted to try her luck in this world-famous competition. - That it would greatly encourage her to exhibit topmost speed if

[68]she could be allowed to start running a few minutes previously to

older stagers. - That if this is unfortunately contrary to regulations, then the

Judge should receive secret instructions to look with a favourable

eye upon the said female horse (whose name is Milky Way) and award

her first prize, even if by any chance she may not prove quite so

fast a runner as more professional hacks:And your Petitioner will ever pray on bended knees that so truly

magnificent an institution as the Epsom Derby Course may never be

suppressed on grounds of encouraging national vice of gambling and

so forth. Signed, &c.

The wording of the above proved Mr

Bhosh's profound acquaintance with the human

heart, for it instantaneously attained the desired

end.

The Honble Stewards returned a very kind[69]

answer, readily consenting to receive Milky

Way as a candidate for Derby honours, but

regretting that it was ultra vires to concede

her a few minutes' start, and intimating that

she must start with a scratch in company with

all the other horses.

Bindabun was not in the least degree cast

down or depressed by this refusal of a start,

since he had not entertained any sanguine

hope that it would be granted, and had only

inserted it to make insurance doubly sure, for

he was every day more confident that Milky

Way was to win, even though obliged to step

off with the rank and file.[70]

CHAPTER X

TRUST HER NOT! SHE IS FOOLING THEE!

As the Sunset flames most fiery when snuffed out by sudden night;

As the Swan reserves its twitter till about to hop the twig;

As the Cobra's head swells biggest just before he does his bite;

So a feminine smiles her sweetest ere she gives her nastiest dig.

Satirical Stanza (unpublished) by H. B. J.

Now that our hero had obtained that

the name of Milky Way was to be

inscribed on the Golden Book of Derby candidates,

his next proceeding was to hire a

practical jockey to assume supreme command

of her.

And this was no simple matter, since practical

jockeys are usually hired many weeks

beforehand, and demand handsome wages for

taking their seats. But at last, after protracted

advertisements, Mr Bhosh had the

good fortune to pitch upon a perfect treasure,[71]

whose name was Cadwallader Perkin,

and who, for his riding in some race or other,

had been awarded a whole year's holiday by

the stewards who had observed the paramountcy

of his horsemanship.

No sooner had Perkin inspected Milky

Way than he was quite in love with his

stable companion, and assured his employer

that, with more regular out-of-door exercise,

she would be easily competent to win the

Derby on her head, whereupon Mr Bhosh

consented that she should be galloped after

dark round the inner circle of Regent's Park,

which is chiefly populated at such a time by

male and female bicyclists.

But in order to pay Perkins charges, and

also provide a silken jockey tunic and cap

of his own racing colours (which were cream

and sky-blue), Mr Bhosh was compelled to

borrow more money from Mr McAlpine, who,

as a Jewish Scotch, exacted the rather exorbitant

interest of sixty per centum.

It leaked out in some manner that Milky[72]

Way was a coming Derby favourite, and the

property of a Native young Indian sportsman,

whose entire fortunes depended on her

success, and soon immense multitudes congregated

in Regent's Park to witness her

trials of speed, and cheered enthusiastically

to behold the fiery sparks scintillating from

the stones as she circumvented the inner

circle in seven-leagued boots.

Mr Bhosh of course asseverated that she

was a very mediocre sort of mare, and that

he did not at all expect that she would prove