The Project Gutenberg eBook of Speciation of the Wandering Shrew

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Speciation of the Wandering Shrew

Author: James S. Findley

Release date: December 20, 2011 [eBook #38356]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Tom Cosmas, Joseph Cooper and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SPECIATION OF THE WANDERING SHREW ***

after the article's text.

[Pg 1]

December 10, 1955

Speciation of the Wandering Shrew

University of Kansas

Lawrence

1955

[Pg 2]

University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, A. Byron Leonard,

Robert W. Wilson

Volume 9, No. 1, pp. 1-68, figures 1-18

Published December 10, 1955

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

PRINTED BY

FERD VOILAND, JR., STATE PRINTER

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1955

25-7903

[Pg 3]

| PAGE | |

Introduction | 4 |

Materials Methods and Acknowledgments | 4 |

Non-geographic Variation | 7 |

Characters of Taxonomic Worth | 8 |

Pelage Change | 9 |

Geographic Distribution and Variation | 9 |

| Pacific Coastal Section | 9 |

| Inland Montane Section | 11 |

| Great Basin and Columbia Plateau Section | 12 |

| Summary of Geographic Variation | 13 |

| Origin of the Sorex vagrans Rassenkreis | 16 |

Relationships With Other Species | 26 |

Conclusions | 60 |

Table of Measurements | 62 |

Literature Cited | 66 |

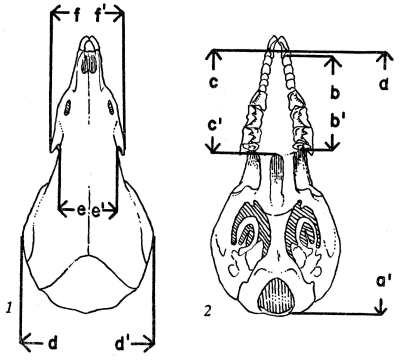

Figs. 1-2.—Cranial Measurements | 5 |

Fig. 3.—Graph Illustrating Wear of Teeth | 8 |

Fig. 4.—Graph Illustrating Heterogonic Growth of Rostrum | 10 |

| Fig. 5.—Present Geographic Distribution of Sorex vagrans | 15 |

| Fig. 6.—Skulls of Sorex vagrans | 17 |

Figs. 7-10.—Past Geographic Distribution of Shrews | 19-20-22-27 |

Figs. 11, 12.—Medial View of Lower Jaws of Two Shrews | 30 |

Figs. 13, 14.—Second Unicuspid Teeth of Shrews | 30 |

Fig. 15.—Diagram of Probable Phylogeny of Shrews | 32 |

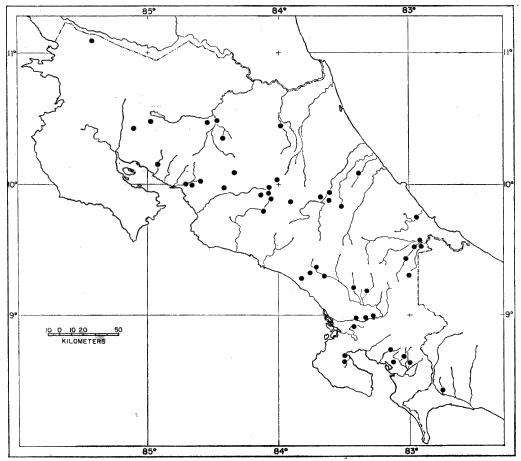

Figs. 16-18.—Geographic Distribution of Subspecies | 33-40-53 |

[Pg 4]

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this report is to make clear the biological relationships

between the shrews of the Sorex vagrans-obscurus "species

group." This group as defined by H. H. T. Jackson (1928:101)

included the species Sorex vagrans, S. obscurus, S. pacificus, S.

yaquinae, and S. durangae. The last mentioned species has been

shown (Findley, 1955:617) to belong to another species group.

Sorex milleri, also assigned to this group by Jackson (1947:131),

seems to have its affinities with the cinereus group as will be explained

beyond. The position of the vagrans group in relationship

to other members of the genus will be discussed.

Of this group, the species that was named first was Sorex vagrans

Baird, 1858. Subsequently many other names were based on members

of the group and these names were excellently organized by

Jackson in his 1928 revision of the genus. Subsequent students of

western mammals, nevertheless, have been puzzled by such problems

as the relationship of (1) Sorex vagrans monticola to Sorex

obscurus obscurus in the Rocky Mountains, (2) Sorex pacificus, S.

yaquinae, and S. obscurus to one another on the Pacific Coast, and

(3) S. o. obscurus to S. v. amoenus in California. Few studies have

been made of these relationships. Clothier (1950) studied S. v.

monticola and S. o. obscurus in western Montana and concluded that

the two supposed kinds actually were not separable in that area.

Durrant (1952:33) was able to separate the two kinds in Utah as

was Hall (1946:119, 122) in Nevada. Other mammalogists who

worked within the range of the vagrans-obscurus groups have

avoided the problems in one way or another. Recently Rudd (1953)

has examined the relationships of S. vagrans to S. ornatus.

MATERIALS METHODS AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Approximately 3,465 museum study skins and skulls were studied. Most

of these were assembled at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History,

but some were examined in other institutions.

Specimens were grouped by geographic origin, age, and sex. Studies of

the role of age and sex in variation were made. Because it was discovered

that secondary sexual variation was negligible, both males and females, if of

like age and pelage, were used in comparisons designed to reveal geographic

variation.

External measurements used were total length, length of tail, and length of

hind foot. After studying a number of cranial dimensions I chose those listed

below as the most useful in showing differences in size and proportions of the

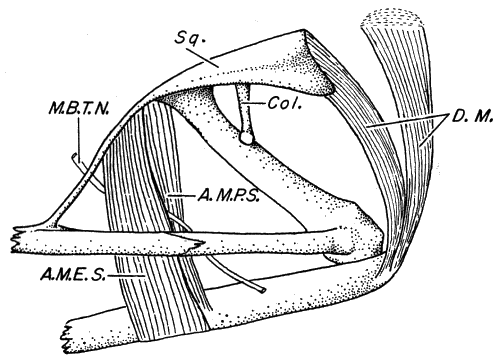

skull. Figures 1 and 2 show the points between which those measurements

were taken.

[Pg 5]

Condylobasal length.—From anteriormost projection of the premaxillae to posteriormost

projection of the occipital condyles (a to a´).

Maxillary tooth-row.—From posteriormost extension of M3 to anteriormost extension

of first unicuspid (b to b´).

Palatal length.—From anteriormost projection of premaxillae to posteriormost

part of bony palate (c to c´).

Cranial breadth.—Greatest lateral diameter of braincase (d to d´).

Least interorbital breadth.—Distance between medialmost superior edges of

orbital fossae, measured between points immediately above and behind

posterior openings of infraorbital foramina (e to e´).

Maxillary breadth.—Distance between lateral tips of maxillary processes

(f to f´).

Figs. 1 and 2. Showing where certain cranial

measurements were taken. × 3½. (Based on

Sorex vagrans obscurus, from Stonehouse Creek,

5½ mi., W junction of Stonehouse Creek and

Kelsall River, British Columbia, , 28545 KU.)

In descriptions of color, capitalized terms refer to those in Ridgway (1912).

In addition the numerical and alphabetical designations of these terms are given

since a knowledge of the arrangements of these designations enables one quickly

to evaluate differences between stated colors. Color terms which are not

capitalized do not refer to any precise standard of color nomenclature.

In the accounts of subspecies, descriptions, unless otherwise noted, are of

first year animals as herein defined. Descriptions of color are based on fresh

pelages.

[Pg 6]

Unless otherwise indicated, specimens are in the University of Kansas

Museum of Natural History. Those in other collections are identified by the

following abbreviations:

| AMNH | American Museum of Natural History |

| CM | Carnegie Museum |

| ChM | Chicago Museum of Natural History |

| CMNH | Cleveland Museum of Natural History |

| FC | Collection of James S. Findley |

| HC | Collection of Robert Holdenreid |

| SGJ | Collection of Stanley G. Jewett |

| CDS | Collection of Charles D. Snow |

| AW | Collection of Alex Walker |

| NMC | National Museum of Canada |

| OSC | Oregon State College |

| PMBC | British Columbia Provincial Museum of Natural History |

| SD | San Diego Natural History Museum |

| BS | United States Biological Surveys Collection |

| USNM | United States National Museum |

| UM | University of Michigan Museum of Zoology |

| OU | University of Oregon Museum of Natural History |

| UU | University of Utah Museum of Zoology |

| WSC | Washington State College, Charles R. Conner Museum |

In nature, the subspecies of Sorex vagrans form a cline and are distributed

geographically in a chain which is bent back upon itself. The subspecies in

the following accounts are listed in order from the southwestern end of the

chain clockwise back to the zone of overlap.

The synonymy of each subspecies includes the earliest available name and

other names in chronological order. These include the first usage of the name

combination employed by me and other name combinations that have been

applied to the subspecies concerned.

In the lists of specimens examined, localities are arranged first by state or

province. These are listed in tiers from north to south and in any given tier

from west to east. Within a given state, localities are grouped by counties,

which are listed in the same geographic sequence as were the states and

provinces (N to S and W to E). Within a given county, localities are arranged

from north to south. If two or more localities are at the same latitude the

westernmost is listed first. Marginal localities are listed in a separate paragraph

at the end of each account. The northernmost marginal locality is listed first

and the rest follow in clockwise order. Those records followed by a citation to

an authority are of specimens which I have not personally examined. Marginal

records are shown by dots on the range maps. Marginal records which cannot

be shown on the maps because of undue crowding are listed in Italic type.

To persons in charge of the collections listed above I am deeply indebted.

Without their generous cooperation in allowing me to examine specimens in

their care this study would not have been possible. Appreciated suggestions

in the course of the work have been received from Professors Rollin H. Baker,

A. Byron Leonard, R. C. Moore, Robert W. Wilson, and H. B. Tordoff, and

many of my fellow students. Mr. Victor Hogg gave helpful suggestions on the

preparation of the illustrations. My wife, Muriel Findley, devoted many hours

[Pg 7]

to secretarial work and typing of manuscript. Finally I am grateful to Professor

E. Raymond Hall for guidance in the study and for assistance in preparing the

manuscript. During the course of the study I received support from the

University of Kansas Endowment Association, from the Office of Naval Research,

and from the National Science Foundation.

NON-GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION

Non-geographic variation, that is to say, variation within a single

population of shrews, consists of variation owing to age and normal

individual variation. In Sorex I have detected no significant secondary

sexual differences between males and females; accordingly

the two sexes are here considered together.

Variation with age must be considered in order to assemble

comparable samples of these shrews. Increased age results in wear

on all teeth and in particularly striking changes in the size and shape

of the first incisors. Skulls of older shrews develop sagittal and

lambdoidal ridges, and further differ from skulls of young animals

in being slightly broader and shorter, and in developing thicker

bone, particularly on the rostrum which thus seems to be, but is

not always in fact, more robust. Pruitt has recently (1954) noted

these same cranial differences in specimens of Sorex cinereus of

different ages.

Several students of American shrews, notably Pearson (1945)

on Blarina, Hamilton (1940) on Sorex fumeus, and Conaway (1952)

on Sorex palustris, have shown that young are born in spring and

summer, usually reach sexual maturity the following spring, and

rarely survive through, or even to, a second winter. The result is

that collections made, as most of them are, in spring and summer,

contain two age classes, first year and second year animals. These

two age classes are readily separable on the basis of differences in

the skull as well as on the decreased pubescence of the tail and the

increased weight of second year animals. My own examination of

hundreds of museum specimens confirms this for the Sorex vagrans

group. Separation of the two age classes in an August-taken series

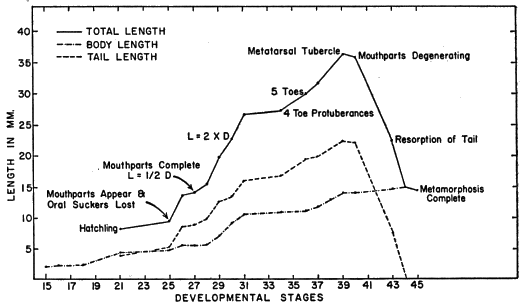

of Sorex vagrans from coastal Washington is shown in figure 3, in

which two tooth-measurements that are dependent upon wear are

plotted against one another.

First year animals are more abundant in collections than are

second year animals. Within the first year, that is to say from spring

to late fall, animals vary but little. Dental characters are best

studied in first year shews. For this reason I have used them as the

basis for the study of geographic variation, and descriptions are

based on first year animals unless otherwise noted.

[Pg 8]

CHARACTERS OF TAXONOMIC WORTH

Within the Sorex vagrans complex, the only characters of taxonomic

significance that I have detected are in size and color. It is

true that cranial proportions, such as relative size of rostrum, may

change from population to population, but these proportions seem

to me to be dependent upon actual size of the individual shrew as

I shall elsewhere point out. Of the cranial measurements here

employed, palatal length and least interorbital breadth are the most

significant and useful. Color in the S. vagrans group seems to be

in Orange and Cadmium Yellow, colors 15 and 17 of Ridgway

(1912). No specimens actually possess these pure colors, but most

colors in these shrews are seen to be derived from the two mentioned

by admixture of black and/or neutral gray. In color designations

an increase in neutral gray is indicated by an increased number of

prime signs ( ´ ), whereas increase in black is indicated by progressive

characters of the Roman alphabet (i, k, m). Thus, 17´´k is grayer

than 17´k and 17´´m is blacker than 17´´k. In subspecific diagnoses in

this report, color and size, and sometimes relative size, are the

characters usually mentioned.

Fig. 3. Two measurements (in millimeters)

reflecting tooth-wear plotted against one another. First year and second

year individuals of Sorex vagrans vagrans, all taken in August at

Willapa Bay, Washington, are completely separated. Open circles represent

teeth of second year shrews; solid circles represent teeth of first year

shrews.

[Pg 9]

PELAGE CHANGE

In general, winter pelage is darker than summer pelage in these

shrews. Winter pelage comes in first on the rump and spreads

caudad and ventrad. The growth line of incoming hair is easily

detected on the fur side of the skin. Throughout the winter the

color of the pelage changes, often becoming somewhat browner,

although no actual molt takes place. This was noted by Dalquest

(1944) who assumed that the color change resulted from molt

although he was unable to detect actual replacement of hairs.

Summer pelage usually comes in first on the back or head and moves

posteriorly and laterally. Time of molt depends on latitude and

altitude. Summer pelage may appear fairly late in the season and

may account for the anomalous midsummer molt noted by Dalquest.

Fresh pelages of summer and winter are best seen in first year

animals and are less variable than are worn pelages and hence are

used as the basis of color descriptions.

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION AND VARIATION

Pacific Coastal Section

The largest shrews of the vagrans group (large in all dimensions)

occur in the coastal forests of northern California and of Oregon.

Those shrews are reddish, large-skulled, large-toothed, and have

rostra that are large in proportion to the size of the skull as a whole.

The very largest of these shrews live along the coast of northwestern

California. To the southward they are somewhat smaller, and at successively

more northern localities, to as far as southwestern British

Columbia, they are likewise progressively smaller and also somewhat

less reddish. The relative size of the rostrum decreases with

the decrease in size of the skull; consequently smaller shrews have

relatively smaller rostra (see fig. 4). In addition the zygomatic

ridge of the squamosal decreases in relative size with decrease in

actual size of the skull. Thus, these features change in a clinal

fashion as one proceeds from, say, Humboldt County, California,

northward to Astoria, Oregon.

Turning our attention now farther inland to the Cascade Mountains

of northern Oregon, the shrews there also are smaller and less

reddish (more brownish) than in northwestern California, and the

trend to smaller and darker shrews culminates in the northern

Cascades of Washington. Shrews from there, and from the southwestern

coast of British Columbia, compared with those from

northwestern California, are much smaller and have so great a suffusion

of black that they appear brown rather than red. At places

[Pg 10]

along the coast successively farther north of southwestern British

Columbia the shrews become larger again, the largest individuals

being those from near Wrangell, Alaska. From that place northwesterly

along the coast of Alaska, size decreases again.

Fig. 4. Condylobasal length (in millimeters)

plotted against palatal index (palatal length/condylobasal length × 100)

in several subspecies of Sorex vagrans to show relative increase

in size of rostrum with actual increase in size of skull.

The shrews so far discussed inhabit forests in a region of high

rainfall and a minimum of seasonal fluctuation in temperature. Such

a habitat seems to be the optimum for shrews of the vagrans group

since the largest individuals are found there. In addition, shrews

seem to be as common, or commoner, in this coastal belt, than they

are in other places.

The large shrews of the vagrans group on the Pacific coast were

divided into three species by H. H. T. Jackson in his revision of the

North American Sorex in 1928. The large reddish shrews of the

coast of California and southern Oregon were called S. pacificus.

The somewhat smaller ones from the coast of central Oregon were

called S. yaquinae. Still smaller shrews from northwestern Oregon

and from the rest of the Pacific coast north into Alaska were called

S. obscurus. I find these kinds to intergrade continuously one with

the next in the manner described and conclude that all are of a

single species.

[Pg 11]

Inland from the coasts of British Columbia and Alaska the size

of the vagrans shrew decreases rapidly. Specimens from western

Alaska, central Alaska, and the interior of British Columbia are

uniformly smaller than coastal specimens. In addition the red of

the hair is masked more by neutral gray than by black with the

result that the pelage is grayish rather than brownish or reddish.

Shrews of this general appearance are found southward through the

Rocky Mountain chain to Colorado and New Mexico. On the more

or less isolated mountain ranges of Montana east of the continental

divide the vagrans shrew is somewhat smaller still. On the Sacramento

Mountains of southeastern New Mexico the shrew is somewhat

larger and slightly darker. Southwestward from the Colorado

Rockies this shrew becomes smaller and slightly more reddish (less

grayish).

All of these montane populations of the vagrans shrew are commonest

in hydrosere communities, that is to say, streamsides and

marshy areas where the predominant vegetation is grass, sedges,

willows, and alders. Since these animals are less common within

the montane forests, hydrosere communities, rather than the actual

forest, seem to be the positive feature important for the shrews.

The shrews of the montane region just described were regarded

by Jackson as belonging to two species: Sorex obscurus, occupying

all the Rocky Mountains south to, and including, the Sacramento

Mountains; S. vagrans, made up of small individuals from various

places in Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado, and all the shrews of

western New Mexico and all of Arizona. My study of these animals

has led me to conclude that the smaller shrews of Arizona and New

Mexico intergrade in a clinal fashion with the shrews of Colorado

and in fact represent but one species. Since some individuals from

Colorado are as small as larger individuals from this southwestern

population of small animals, I conclude that such specimens are

the basis for reports of S. vagrans from Colorado. The shrews of

the Sacramento Mountains resemble those of the Colorado Rockies

more than they do the smaller shrews of western New Mexico and

Arizona, possibly because the climate is similar in the Sacramento

Mountains and the higher Colorado Rockies. There is less precipitation

in the more western mountain ranges in New Mexico and in

Arizona in April, May, and June than in the Colorado Rockies.

These months are critical for the reproduction and growth of shrews.

[Pg 12]

As mentioned above, the shrews from east of the continental divide

in Montana are smaller than those of the other mountains of the

state, and it is upon such small animals that the name Sorex vagrans

has been based in this area. It is clear, however, that these smaller

animals intergrade with the larger shrews of the more western

mountains. The small size might be an adaptation to the lesser

precipitation and harsher continental climate east of the continental

divide in Montana.

Great Basin and Columbia Plateau Section

The vagrant shrews of the Great Basin and adjoining Columbia

Plateau and Snake River Plains are smaller than their relatives in

the Rocky Mountains and, by virtue of less gray in their pelage,

are reddish in summer and blackish rather than grayish in winter.

There is little significant geographic variation in shrews throughout

this region, although owing to their restriction to the vicinity of

water, the populations of shrews are more or less isolated from one

another and each is somewhat different from the next. Those from

nearest the Rockies are sometimes slightly larger and those from

some places in Nevada are slightly paler than the average. This small

reddish shrew is found all the way to the Pacific coast of California,

Oregon, and Washington. In these coastal areas it is somewhat

darker and sometimes a trifle larger than elsewhere. It intergrades

with a somewhat larger, grayer shrew in the Sierra Nevada of

California. Along the Wasatch front in Utah, this Great Basin shrew

intergrades with the larger, grayer shrew of the Rockies. Owing

to the abrupt change in elevation, the zone of intergradation is

rather narrow horizontally. In the latitude of Salt Lake City,

populations of intergrades occur at between 8,700 and 9,000 feet

elevation. The lowland shrew occurs in the eastern part of the Snake

River Plains, and along the valleys of the Bear and Salt rivers into

Wyoming. Along the northern edge of the Snake River Plains and

on the western edge of the mountains of central Idaho the transition

from lowland to montane habitats is abrupt and in consequence the

zone of contact between small and large shrews is narrow. In

northern Idaho and northwestern Montana the transition from lowland

to highland is more gradual. Tributaries of the Columbia

River system, especially the Clark Fork, provide a path for movement

of lowland forms into intermontane basins of western Montana.

In addition, the vegetational zones are found at lower elevations,

and there are boreal forests in the lowlands rather than only in

[Pg 13]

the mountains as is the case in Utah and Colorado. In this area,

therefore, the zone of intergradation between the smaller lowland

shrew and the larger montane shrew is more gradual and gradually

intergrading populations are found over a relatively large area.

This has been well demonstrated for northwestern Montana by

Clothier (1950). In southern British Columbia and northern Washington

this shrew in the mountains is large and in the intermontane

valleys is small. There is extensive interdigitation of valleys and

mountain ranges, and, consequently, of life-zones in this region.

In a few places, recognizably distinct populations of the vagrant

shrew occur within a few miles of one another, but in other places

there are populations of intergrades. West of the Cascades no

evidence of intergradation has been found and the two kinds occur

almost side by side and maintain their distinctness.

These Great Basin shrews dwell in hydrosere communities as do

their Rocky Mountain counterparts. In this arid region such a

habitat obviously is the only one habitable for a shrew of the vagrans

group. These shrews often maintain their predilection for such

habitats when they reach the Pacific coast, and are commonly found

in such places as coastal marshes, marshy meadows, and streamsides,

while the woodlands are inhabited by other species.

These small shrews of the Great Basin and the small vagrant

shrews of the Pacific Coast were called Sorex vagrans by Jackson.

Summary of Geographic Variation

Large reddish shrews of the coast of California and southwestern

Oregon become smaller and darker to the north. From southwestern

British Columbia they again become larger as one proceeds

northward along the coast to Wrangell, Alaska, and north of that

they again become smaller. Moving inland from the coast the

shrews become markedly smaller in Alaska and British Columbia.

The smaller inland and montane form occurs south through the

Rocky Mountains, becoming slightly smaller in central Montana,

slightly larger in southeastern New Mexico, and slightly smaller in

western New Mexico and in Arizona. This montane form intergrades

with a smaller more reddish Great Basin shrew, the zone of

intergradation roughly following the western slope of the Rocky

Mountains. The Great Basin shrew occurs westward to the Pacific

Coast; there the Great Basin shrew occurs with, although in part it

is ecologically separated from, the large reddish coastal shrews.

There seems to be an intergrading chain of subspecies of one

[Pg 14]

species, the end members of which (the small Great Basin form

and the large coastal form) are so different in size and ecological

niche that they are able to coexist without interbreeding. In southern

British Columbia the morphological differences are not so

marked as farther south along the Pacific Coast. There, in British

Columbia, reproductive isolation is not complete and occasional

populations of intergrades occur. In Montana extensive intergradation

occurs in a broad zone of transitional habitat. Along the western

edge of the Rockies from Idaho south to Utah the zone of

transition from montane to basin habitat is sharp and the zone of

intergradation, although present, is fairly narrow, perhaps because

there is little intermediate habitat which logically might be expected

to be most suitable for intergrading populations.

The oldest name applied to a shrew of the group under consideration

is Sorex vagrans Baird, 1858, the type locality of which is

Willapa Bay, Pacific County, Washington. The name applies to

the small vagrant shrew of this area, rather than to the larger forest

dweller which has been known as Sorex obscurus. The name S.

vagrans, in the specific sense, must therefore apply to all the shrews

discussed which have heretofore been known by the names S. pacificus,

S. yaquinae, S. obscurus, and S. vagrans.

A situation such as the one here described where well differentiated

end members of a chain of subspecies overlap over an extensive

geographic range throughout the year without interbreeding—thus

reacting toward one another as do full species—so far as I know

has not previously been found to exist in mammals. The overlapping

end-members of the chain of subspecies of Sorex vagrans

really do coexist; specimens of the overlapping subspecies have

been taken together at the same localities from California to British

Columbia. I have taken a specimen of S. v. vagrans and several of

S. v. setosus in the same woodlot at Fort Lewis, Pierce County,

Washington. Two subspecies of deer, Odocoileus hemionus, in the

Sierra Nevada of California, occur together over a sizeable area but

for only a part of each year that does not include the breeding

season (Cowan, 1936:156-157). In the deer mouse, Peromyscus

maniculatus, the geographic ranges of several pairs of subspecies

meet at certain places without intergradation of the two kinds. In

these instances well marked ecological differences exist between the

subspecies involved. In western Washington, for example, the

geographic range of the lowland subspecies, P. m. austerus, interdigitates

to the east and west with the range of the montane and

coniferous forest-inhabiting subspecies, P. m. oreas, and the two

kinds have not been shown to intergrade. Peromyscus maniculatus

artemesiae and P. m. osgoodi come together without interbreeding

in Glacier National Park, Montana. P. m. artemesiae is almost entirely

a forest-dwelling subspecies, whereas osgoodi is an inhabitant

of open country. The two kinds do not actually occur together

ecologically although they occur together in buildings at the edge

of the woods (A. Murie, 1933:4-5).

[Pg 15]

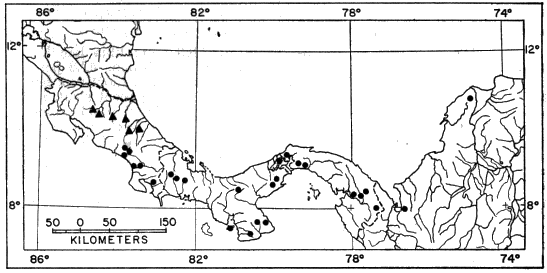

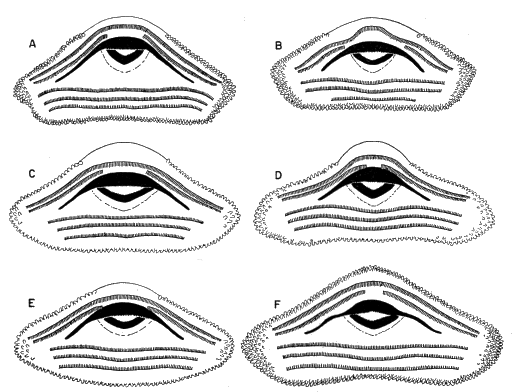

Fig. 5. Probable present geographic

distribution of Sorex vagrans. The range of S. v. vagrans

and its derivatives S. v. vancouverensis, S. v. halicoetes,

and S. v. paludivagus, is shown by lines slanting in a different

direction than those which mark the range of all the other subspecies of

S. vagrans. The region in which S. v. vagrans occurs

together with other subspecies of S. vagrans is shown by the

superposition of one pattern upon the other.

[Pg 16]

Cases of sympatric existence of two subspecies of one species are

known in birds and in reptiles. Notable examples are in the gull,

Larus argentatus (Mayr, 1940), in the Old World warbler, Phylloscopus

trochiloides (Ticehurst, 1938), and in the great titmouse,

Parus major (Rensch, 1933), of the Old World. In the first species

the two end-members, the herring gull and the lesser black-backed

gull, occur together over an extensive region from northern Europe

and the British Isles throughout Fennoscandia. Fitch (1940) described

a rassenkreis with overlapping subspecies in the garter

snake Thamnophis ordinoides.

The geographic distribution of the species Sorex vagrans is shown

in figure 5. The geographic range of the Great Basin subspecies

is shown by a different pattern of lines than the other subspecies of

S. vagrans. In the region in which the geographic range of the

Great Basin subspecies overlaps those of the subspecies of the

Pacific Coast, the pattern of shading for the Great Basin subspecies

is superimposed on the patterns for the other subspecies.

ORIGIN OF THE SOREX VAGRANS RASSENKREIS

The distribution of the species Sorex vagrans and that of its immediate

ancestors obviously has not always been the same; during

glacial ages much of the present range of the species in Canada and

in some of the higher mountains of the United States was covered

with ice and not available to the shrew. Furthermore, large areas

that are now too hot and dry to permit the existence of S. vagrans

were at one time habitable. If we are to speculate on the manner

in which the Sorex vagrans rassenkreis originated we must inquire

into the nature and extent of these climatic changes.

The most recent epoch of geological time, the Pleistocene, is

known to have been divided into a series of alternating glacial and

interglacial ages. During the glacial ages continental and montane

glaciers are judged to have covered much of Canada and the northern

United States. Concurrently the major storm tracks of the west

probably were shifted southward; in any event much of the now

arid intermontane west was much better watered than it is today.

[Pg 17]

The increased precipitation, and probably glacial meltwater, formed

large lakes in the closed basins of the Great Basin. There were

boreal forests at lower elevations than there are today in comparable

latitudes and continuous boreal habitat probably connected many

of the isolated mountain ranges of the southwest. That probability

is supported by the presence of boreal animals and plants on many

[Pg 18]

of these isolated ranges today. A boreal tree squirrel, such as

Tamiasciurus, could hardly be suspected of crossing a treeless, intermontane

desert valley, miles wide.

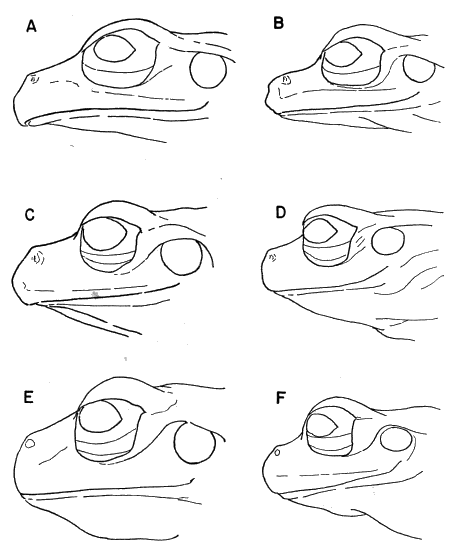

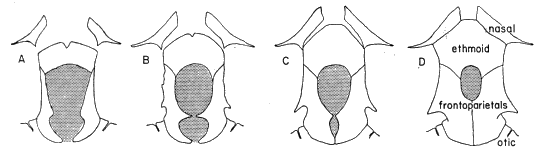

Figs. 6a-6f. Fig. 6a.

Sorex vagrans pacificus, 1 mi. N Trinidad, Humboldt Co.,

California, FC 1442. Fig. 6b. S. v. yaquinae, Newport,

Lincoln Co., Oregon, AW 707. Fig. 6c. S. v. yaquinae

(near bairdi), McKenzie Bridge, Lane Co., Oregon, AW 82.

Fig. 6d. S. v. setosus, Reflection Lake, Jefferson Co.,

Washington, CMNH 4275. Fig. 6e. S. v. obscurus, 10 mi. SSW

Leadore, Lemhi Co., Idaho, FC 1499. Fig. 6f. S. v. vagrans,

Baker Creek, White Pine Co., Nevada, 88042 (after Hall, 1946:113).

Interglacial ages were characterized by warmth and aridity as

compared to the glacial ages. Glaciers retreated or disappeared,

boreal forests became montane in much of the United States, and

the lakes in the Great Basin were reduced or disappeared. One can

envision that during such times boreal mammals were isolated,

their geographic ranges were restricted, and Sonoran mammals expanded

their ranges.

Evidence is more extensive concerning the number and extent of

glacial ages in the eastern than in the western part of North America.

This evidence suggests a division of the Pleistocene into four glacial

ages and four interglacial ages, the fourth interglacial age corresponding

to the present time. More information is available about

the Wisconsinan, or last, glacial age, than about the earlier ones,

because the last glaciation in many montane areas destroyed evidence

of earlier glaciations. The names of currently recognized

glacial and interglacial ages of the Pleistocene are listed below. The

names of interglacial ages are in Italic type.

Wisconsinan

Sangamonian

Illinoian

Yarmouthian

Kansan

Aftonian

Nebraskan

We may think of these ages as an alternating series of cool moist

and warm dry periods during which boreal mammals, and other

organisms, alternately moved southward (disappearing in the glaciated

regions) and northward into previously glaciated areas (while

disappearing from southern areas except on isolated mountain

ranges). Sorex vagrans probably followed this pattern of movement

and now is restricted to forested or well-watered places.

One possible series of events culminating in the formation of the

Sorex vagrans rassenkreis may be thought of as having begun during

the Illinoian age. With much of Canada, and perhaps also many

areas in the Rockies, Cascades, and the Sierra Nevada covered with

glacial ice, the shrew-stock ancestral to Sorex vagrans may well have

occupied a more or less continuous range over the Colorado Plateau,

the Columbian Plateau, the Great Basin, and in the forests of the

Pacific Coast (as well as over part of eastern United States, as will

[Pg 19]

be explained beyond; see fig. 7). At that time the species probably

was a continuously interbreeding unit.

Fig. 7. Possible distribution in Illinoian

(inset) and Sangamonian times of the ancestor of the Sorex

vagrans-ornatus-longirostris-veraepacis complex. Approximate

southern boundary of Illinoian glaciation marked by heavy line.

In the ensuing Sangamonian interglacial age all glaciers retreated

or disappeared thereby opening up extensive areas in the north and

in the higher mountains which were occupied by a boreal fauna,

including S. vagrans. Concurrently the Great Basin, and probably

also much of the Columbian Plateau, became dry, and desert conditions

developed, perhaps much as they are today. Increasing

aridity eliminated shrew habitat in most places between the Rocky

Mountains and the Sierra Nevada-Cascade mountain chain with the

result that the geographic range of the species resembled an inverted

"U", one arm lying along the Rocky Mountains and the other along

the Cascade-Sierra Nevada axis; the connection between the two

arms was in British Columbia (see fig. 7). At present Sorex vagrans

[Pg 20]

does occur in isolated places in the Great Basin, but its existence

there is tenuous and seemingly dependent upon the occurrence of

permanent water such as Ruby Lake and Reese River. With such

an arrangement as this it can readily be seen that gene flow between

the eastern and western arms of the "U" would be greatly reduced

by distance; consequently differentiation between the two might

be expected.

Fig. 8. Possible distribution of Sorex

vagrans at two different times in the Wisconsinan Age. Left, early

Wisconsinan; right, mid-Wisconsinan.

Wisconsinan glaciation again rendered Canada uninhabitable,

and it is quite possible that extensive areas in the Rocky Mountains,

the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada were heavily glaciated. With

the elimination of the northern part of the "U", the eastern and

[Pg 21]

western arms became isolated, if not by the width of the Columbian

Plateau at least by the glaciated Cascade Mountains. At the same

time extensive areas on the Colorado Plateau and much of the area

south to the Mexican highlands were again occupied by the species.

Finally the Great Basin, again being well-watered, provided suitable

habitat for, and was reoccupied by, Sorex vagrans (see fig. 8).

This reoccupation of the Great Basin took place probably from

the Colorado Plateau and mountains of Arizona and Utah, since the

present day shrews of the species S. vagrans in the Great Basin

closely resemble Rocky Mountain shrews but differ markedly from

the large endemic subspecies of the Pacific Coast.

Finally, with the waning of Wisconsinan ice, the species again

was able to occupy northern and montane areas as it had during

Sangamonian times. Again dessication of the Great Basin caused

drastic restriction of shrew habitat. The small, marsh-dwelling kind

of wandering shrew which had developed there around the lakes

of Wisconsinan time occupied suitable habitat all the way to the

Pacific coast where its range came into contact with that of the western

arm of the Sangamonian "U."-pattern of shrew distribution (see

fig. 9). The animals of this western segment and the new arrivals

from the east were by this time so different from one another that

the two kinds lived in the same areas without interbreeding. The

descendants of the original western arm now are known as Sorex

vagrans sonomae, S. v. pacificus, S. v. yaquinae, and S. v. bairdi. The

newcomers from the east are known as S. v. vagrans, S. v. halicoetes,

S. v. paludivagus and S. v. vancouverensis.

In addition to occupying the Pacific Coast from San Francisco

Bay north to the Fraser Delta, the Great Basin subspecies populated

the Columbia Plateau and the western foothills of the central and

northern Rockies. By so doing that subspecies came into secondary

contact with its own parent stock with which it was still in reproductive

continuity in Utah. In some places in British Columbia differentiation

between the two kinds had proceeded to such an extent

that some reproductive isolation was effected, but in many other

places the two interbred. The Rocky Mountain form spread north

and west and occupied the Cascades and coastal lowlands in southwestern

British Columbia and in Washington. Here the differentiation

between the Rocky Mountain subspecies and the Great Basin

subspecies was great enough to cause complete reproductive isolation.

[Pg 22]

Fig. 9. Probable changes in the distribution

of Sorex vagrans concurrent with and following the dissipation

of Wisconsinan ice. Dark arrows in Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and

California, shows S. v. vagrans.

[Pg 23]

Deglaciation of the Sierra Nevada opened it up for reoccupation

from the east by Sorex vagranss of the Great Basin. In response to

the montane environment the subspecies obscuroides, resembling

the subspecies obscurus of the Rockies, developed.

Desiccation of the intermontane parts of New Mexico, Arizona,

and Chihuahua, left "marooned" populations of Sorex vagrans on

suitable mountain ranges. In this way Sorex vagrans orizabae may

have been isolated in southern Mexico. The isolated populations

of Arizona and New Mexico differentiated in situ into the subspecies

monticola and neomexicanus.

Western Canada and Alaska were populated by shrews which

originated in the habitable parts of the Rocky Mountains and

Colorado Plateau during Wisconsinan time (as opposed to shrews

originating, as subspecies, in the Great Basin or on the Pacific

Coast). These shrews differentiated into the currently recognized

subspecies of the west coast and coastal islands of British Columbia

and Alaska in response to the different environments in these places,

many of which were isolated; the subspecies isolatus, mixtus, setosus,

longicauda, elassodon, prevostensis, malitiosus, and alaskensis are

thought to have originated in this fashion after the areas now occupied

by them were freed of Wisconsinan ice.

This group of shrews from the Rocky Mountains probably came

into contact with the Pacific coastal segment of the species somewhere

in northwestern Oregon. The clinal decrease in size from

S. v. pacificus to S. v. setosus seems steepest in this area. Upon the

establishment of this contact reproductive continuity was resumed,

probably because the temporal separation of the two stocks involved

was not so great as, say, that between S. v. vagrans and S. v.

pacificus, and in addition the morphological differentiation was not

so great.

On the eastern side of the Rockies the montane stock moved

northeastward, occupying suitable territory opened up by the dissolution

of the Laurentide ice sheet. Still later changes in the

character of the northern plains owing to desiccation divided the

range of the species and isolated S. v. soperi in Manitoba and central

Saskatchewan and a population of S. v. obscurus, in the Cypress

Hills. A number of semi-isolated stocks in central Montana became

differentiated as a recognizable subspecies there.

A number of other boreal mammals have geographic ranges

which resemble that of Sorex vagrans, except that the geographic

ranges of subspecies do not overlap. Because of the general similarities

[Pg 24]

of these geographic ranges, it is pertinent to examine the

reasons suggested by students to account for the present geographic

distributions of some of these other boreal species.

The red squirrel genus, Tamiasciurus, has a Rocky Mountain (and

northern coniferous forest) species, T. hudsonicus, that occurs all

along the Rocky Mountain chain and northward into Alaska. In the

Cascade Mountains of Washington and British Columbia this

species meets the range of a well marked western species, T. douglasii,

with no evidence of intergradation. Dalquest (1948:86)

attributes the divergence of the two species to separation in a

glacial age but feels that the degree of difference between the two

is too great to have all taken place during the Wisconsinan. Perhaps

he has overemphasized the importance of the differences between

the two, but, be that as it may, it seems that the two kinds differentiated

during a glacial age when they were isolated, perhaps by ice

on the Cascades into a coastal population and an inland population.

One difference between the distribution of the red squirrels and

vagrant shrew is that the squirrel of the Sierra Nevada is the species

of the Pacific Coast, whereas the vagrant shrew of the Sierra Nevada

was derived from the Great Basin population, which in turn was

derived from the Rocky Mountain kind. Red squirrels do not occur

on any of the boreal montane "islands" of Nevada. During the

pluvial periods when hydrosere-loving shrews populated the Great

Basin, that region may have been a treeless grassland. Vagrant

shrews, then as now, probably depended on hydrosere communities,

while red squirrels required trees. Therefore the shrews were able

to traverse the Great Basin, while the Sierran red squirrels were of

necessity derived from the coastal population.

The ecological requirements of jumping mice, genus Zapus, and

the subspecies of Sorex vagrans that dwell in hydroseres are essentially

similar. The species Zapus princeps lives in the Rocky

Mountains, the Great Basin, the Sierra Nevada, and north to Yukon

(Krutzsch, 1954:395). Its geographic range is similar to that of

the montane and basin segments of S. vagrans. The species Z. trinotatus

occurs along the Pacific coast and in the Cascades north to

southwestern British Columbia. Its distribution thus coincides in

general with that of the large red coastal subspecies of S. vagrans.

Krutzsch (1954:368-369) thought that these two kinds of jumping

mice were first separated by the formation of the Cascade Mountains

and the Sierra Nevada and finally by Pleistocene glaciation.

The Sierran jumping mouse (Zapus princeps), as is the Sierran

vagrant shrew, is more closely related to the jumping mouse of the

[Pg 25]

Great Basin and of the Rocky Mountains than it is to the jumping

mouse (Z. trinotatus) of the Pacific Coast, just as the Sierran vagrant

shrew is related to the shrew of the Great Basin and Rocky Mountains.

The jumping mouse also is limited in its distribution by

hydrosere communities, not by forests.

In western North America there are two species of water or marsh

shrews: Sorex palustris and S. bendiri. They have been placed in

separate subgenera, but, as pointed out beyond, are closely related

and here are placed in the same subgenus. The species palustris

is found throughout the Rocky Mountains, north into Alaska, across

the Great Basin into the Sierra Nevada, and west to the Pacific

coast in Washington. The species bendiri is found from northwestern

California north along the Pacific coast to southwestern British

Columbia and east to the Cascades. Where the ranges of the two

species overlap in western Washington they do not interbreed so far

as is known, and are somewhat different in their ecology, bendiri

being a lowland, and palustris being a montane, species. The two

species probably were separated in a glacial period as seems to have

been the case with the wandering shrews. Also, the water shrew of

the Sierra Nevada is derived from that of the Great Basin and Rocky

Mountains. Sorex palustris is tied closely in its distribution to hydrosere

communities and is not dependent upon the presence of forests.

Red-backed mice, genus Clethrionomys, occur throughout the

Rocky Mountains and west to the Cascades in Washington as the

species C. gapperi. The species C. californicus is found along the

Pacific Coast from California north to the Olympic Peninsula. Where

the ranges of the two species meet in Washington they seem not to

intergrade. In some glacial interval these two species may have

evolved in the same manner as has been described for the species of

Zapus and those of Tamiasciurus. No Clethrionomys are found in

the Sierra Nevada, nor are red-backed mice found in the boreal

islands of the Great Basin. It is not known why Clethrionomys

californicus does not occur in the Sierra Nevada. Some boreal birds

have distributional patterns similar to those of the mammalian

examples cited above. One kind of sapsucker, Sphyrapicus varius

nuchalis, occurs in the Rocky Mountains north into British Columbia

and west to the Cascades and Sierra Nevada. A related kind, S.

varius ruber, occurs along the Pacific Coast from California north

into British Columbia. Recently Howell (1952) has shown that

some intergradation takes place between ruber and nuchalis in

Washington and British Columbia, although they do not intergrade

[Pg 26]

freely. Previously the two kinds were thought not to intergrade

and were regarded as two species. The two kinds intergrade also

in northeastern California, although in that state S. v. daggeti, rather

than S. v. ruber, is involved in the intergradation. Howell considered

the two kinds to be conspecific with one another as well as with the

eastern S. varius. He attributed a measure of the distinctness of

nuchalis and ruber to their separation during a glacial period, but

felt that the separation was much older than Wisconsinan. Whatever

the time of separation, the pattern seems clear: nuchalis and

ruber (as well as varius) were separated into montane, coastal, and

eastern segments respectively, probably by glaciation (it seems to

me in the Pleistocene), and have since re-established contact with

one another.

The grouse genus Dendrogapus is divided into a Great Basin

species, D. obscurus, which extends northward into British Columbia,

and a Rocky Mountain species, D. fuliginosus, that is found

in the Sierra Nevada and northward along the coast and Cascades

into British Columbia. Although the two kinds have at times been

considered conspecific, they differ in voice, hooting mechanism,

and characters of the downy young, and so far no actual

intergradation between the two has been shown (Grinnell and

Miller, 1944:113). These grouse thus seem to offer additional evidence

for a Pleistocene, possibly Wisconsinan, separation of the

boreal fauna into a Rocky Mountain and a Pacific coastal segment.

A notable sidelight on these data is the frequency with which

species in the Sierra Nevada have their closest relatives in the Rocky

Mountains, rather than in the geographically nearer Cascades or

coastal areas. This similarity in fauna of the Sierra Nevada and the

Rockies was noted long ago by Merriam (1899:86).

RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHER SPECIES

During the Sangamonian interval, isolated segments of the once

widespread ancestral Sorex vagrans quite possibly persisted in such

places as the Sierra Nevada, coastal southern California, the mountains

of Arizona, New Mexico, and southern Mexico, and in the

Black Hills (see fig. 6). One might expect that by Wisconsinan

time these populations would have become reproductively isolated

from their parent stock. They would therefore have remained

specifically distinct when Wisconsinan Sorex vagrans, reoccupied

these outlying areas, and may still be found isolated in places

peripheral to the range of the ancestral species.

[Pg 27]

Fig. 10. Probable distribution of S.

veraepacis, S. longirostris, and the S. ornatus group

(stipple) and of their Wisconsinan ancestors (lines). Heavy line

indicates limits of Wisconsinan glaciation.

In fact, we do find species closely related to Sorex vagrans in just

such places today (fig. 10). Probably Sorex ornatus, including

members of the ornatus group such as S. trigonirostris, S. sinuosus,

S. willeti, S. tenellus, and S. nanus, and also S. veraepacis, arose by

separation from the ancestral vagrans stock in Sangamonian time.

Probably the eastern S. longirostris arose in a like manner. The

ancestor of S. ornatus may have been isolated in southwestern California

during Sangamonian time, spread north and south during the

Wisconsinan age, and afterward given rise to S. trigonirostris and

the modern S. ornatus complex of California and Baja California.

In at least one place reproductive isolation between ornatus and the

invading S. vagrans has broken down (Rudd, 1953); the place is a

salt marsh along San Pablo Bay, where a hybrid population between

S. vagrans and S. sinuosus, an ornatus derivative, has formed. Sorex

tenellus may have been isolated in the Sierra Nevada in the Sangamonian

[Pg 28]

interval, moved into the valleys east of the mountains during

the Wisconsinan age, and become restricted to its present range

since the retreat of the last ice. Sorex nanus may have occurred in

the Black Hills and isolated mountains of Arizona and New Mexico

during the Sangamonian interval and remained in these general

areas during the Wisconsinan age. Its present range is peripheral

to the main body of the Rockies and the Colorado Plateau.

The eastern species Sorex longirostris has many similarities with

shrews of the ornatus-vagrans stock. S. l. longirostris is close in

many ways to S. nanus. Indeed, the differences between the species

S. nanus, S. ornatus, and S. longirostris seem to me to be of the

same magnitude and indicate a similar period of differentiation from

a common ancestor. The ancestor of S. longirostris may have gained

access to the eastern United States in the Illinoian Age via the northern

Great Plains south of the glacial boundary (fig. 7). The ancestor

of Sorex veraepacis of southern Mexico probably reached that

area in Illinoian time as part of the ancestral vagrans stock and probably

attained its differentiation during the Sangamonian interval.

All the kinds of shrews so far discussed, including the S. vagrans

complex, might thus be thought of as having had a common ancestor

in the Illinoian Age. This entire group of shrews has the third unicuspid

smaller than the fourth, a pigmented ridge from the apex to

the cingulum of each upper unicuspid, and, in most individuals,

lacks a post-mandibular foramen in the lower jaw (Findley, 1953:636-637).

The pigment is not always prominent in S. longirostris.

Two other species of North American shrews, Sorex palustris, the

water shrew, and Sorex bendiri, the marsh shrew, show these three

characters to a greater or lesser degree, and it seems that these two

species and the vagrans-ornatus-veraepacis group had a common

ancestor, probably before Illinoian time for reasons stated beyond.

I judge, however, that far from being subgenerically distinct as they

have been considered to be, S. palustris and S. bendiri are actually

closely related species of the same subgenus and may have differentiated

from one another because of separation into eastern (palustris)

and western (bendiri) segments in the Sangamonian interval,

much as has been postulated concerning the eastern and western

stocks of Sorex vagrans. Indeed, Jackson (1928:192) has noted that

in the Pacific northwest the characters of the two kinds approach

one another and become differences of degree only.

The widespread species Sorex cinereus resembles all the foregoing

species in the ridges on the unicuspid teeth and in the lack of a

post-mandibular foramen, but differs from those other species in

[Pg 29]

having the third upper unicuspid larger than the fourth. The subspecies

S. cinereus ohionensis, however, often has the sizes of these teeth

reversed. With S. cinereus I include S. preblei (eastern Oregon) and

S. lyelli (Sierra Nevada), both obviously closely related to

cinereus as Jackson (1928:37) recognized when he included them in the

cinereus group. Sorex milleri (Coahuila and central western Nuevo

Leon) seems to me to resemble S. cinereus more than it does other

species of North American Sorex, and I judge that it also belongs to

the cinereus group. Sorex cinereus and its close relatives seem more

closely related to the species which have thus far been discussed than

they do to such other North American species as S. arcticus, S.

fumeus, S. trowbridgii, S. merriami, and the members of the S.

saussurei group; most of these five species last mentioned possess a

post-mandibular foramen, lack pigmented unicuspid ridges, and have the

third unicuspid larger than the fourth. Because of the morphological

resemblances mentioned above, it seems likely to me that S. cinereus

and the vagrans-ornatus-veraepacis-palustris complex had a common

ancestor in early Pleistocene time. Sorex cinereus has recently been

considered to be conspecific with the Old World S. caecutiens Laxmann

(Van den Brink, 1953) which name, being the older, would apply to the

circumpolar species.

Hibbard (1944:719) recovered S. cinereus and a species of

Neosorex (a name formerly applied to the water shrew) from the

Pleistocene (late Kansan) Cudahy Fauna. This indicates that the

ancestors of the modern S. cinereus and of the water shrew had

diverged from one another before that time. Brown (1908:172)

recorded S. cinereus and S. obscurus from the Conard Fissure in

Arkansas. These materials were deposited probably at a later

time than was the Cudahy Fauna. The S. obscurus from Conard

Fissure probably represents the ancestral S. vagrans stock which I

think reached eastern United States in Illinoian time and gave rise

to S. longirostris. The Conard Fissure material was deposited at a

time (Illinoian?) when northern faunas extended farther south than

they do today.

All of the species mentioned as having structural characters in

common with S. vagrans seem to have arisen from a common ancestor

which had already differentiated from the ancestor of such

species as S. arcticus, S. saussurei, and others. Consequently all

are here included in a single subgenus. The oldest generic name

applied to a shrew of this group, other than the name Sorex, is

Otisorex DeKay, 1842, type species Otisorex platyrhinus DeKay, a

[Pg 30]

synonym of Sorex cinereus. The subgenus can be characterized as

follows.

and pl. 5, fig. 1. Type, Otisorex platyrhinus DeKay (= Sorex

cinereus Kerr).

Third unicuspid usually smaller than fourth; upper unicuspids

usually with pigmented ridge extending from apices medially to

cingula, uninterrupted by antero-posterior groove; post-mandibular

foramen usually absent. Includes the species S. cinereus,

S. longirostris, S. vagrans, S. ornatus, S.

tenellus, S. trigonirostris, S. nanus, S. juncensis,

S. willeti, S. sinuosus, S. veraepacis, S.

palustris, S. bendiri, S. alaskanus, and S.

pribilofensis.

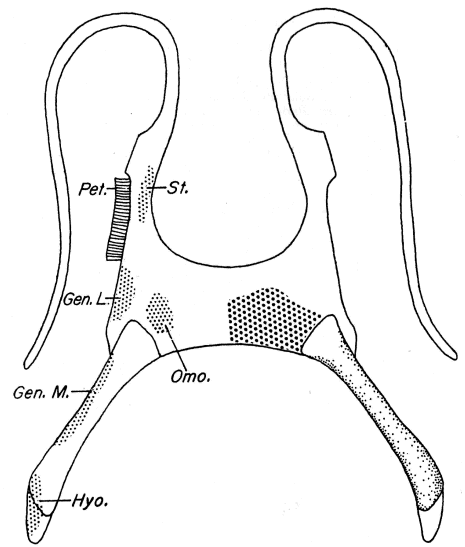

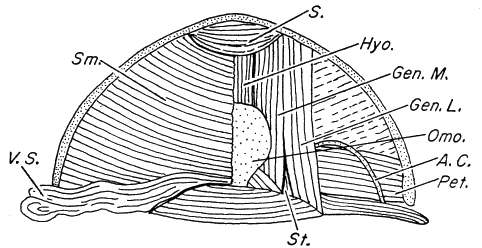

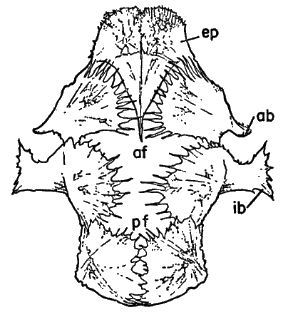

| Figs. 11-14. | Characters of the subgenera Sorex and Otisorex. |

| Fig. 11. | Medial view of right ramus of Sorex (Otisorex) vagrans. × 14. |

| Fig. 12. | Medial view of right ramus of Sorex (Sorex) arcticus. × 14. |

| Fig. 13. | Anterior view of left second upper unicuspid of Sorex (Otisorex) vagrans. × 45. |

| Fig. 14. | Anterior view of left second upper unicuspid of Sorex (Sorex) arcticus. × 45. |

[Pg 31]

Other species of Sorex now occurring in North America differ from

Otisorex in having the 3rd unicuspid usually larger than 4th, in lacking

a pigmented ridge from the apices to the cingula of the upper

unicuspids, and in usually possessing a well-developed post-mandibular

foramen. Exceptions to the last mentioned character are

S. fumeus and S. dispar. The subgenus Sorex in North America

should include only the following species: S. jacksoni, S. tundrensis,

S. arcticus, S. gaspensis, S. dispar, S. fumeus, S. trowbridgii, S.

merriami, and all the members of the Mexican S. saussurei group.

The subgenera Otisorex and Sorex probably separated in early

Pleistocene or late Pliocene. Sorex is unknown in North America

earlier than the late Pliocene (Simpson, 1945:51).

In the genus Microsorex the characters of the subgenus Otisorex

are carried to an extreme; the unicuspid ridges are prominent and

end in distinct cusplets, and the 3rd unicuspid is not merely smaller

than the 4th, but is reduced almost to the vanishing point. In addition,

the post-mandibular foramen is absent. Although it is closer

structurally to Otisorex than to Sorex, the recognition of Microsorex

as a distinct genus seems warranted.

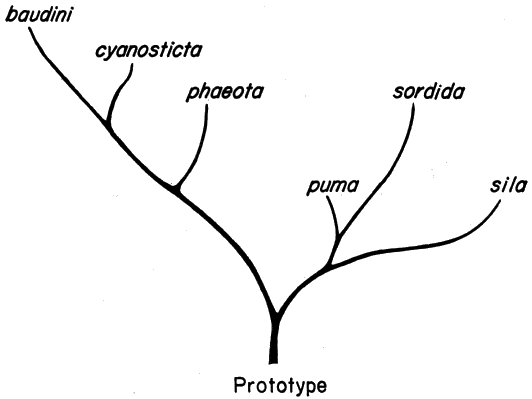

Figure 15 is intended to represent graphically some of the relationships

discussed above. It must be re-emphasized that much of

it is purely speculative, especially as regards actual time when

various separations took place. It will be noted that I have indicated

most separations as having taken place in interglacial ages.

They are generally regarded as periods of warmth and aridity and,

therefore, probably are times of segmentation of the ranges of boreal

mammals and hence times exceptionally favorable to the process of

speciation. Glacial ages, characterized by extensive and continuous

areas of boreal habitat, probably were times of relatively unrestricted

gene flow between many populations of boreal mammals

and hence not favorable to rapid speciation.

The size of the wandering shrew varies from small in the subspecies

monticola and vagrans to large in the subspecies pacificus. The tail

makes up from a little more than a third to almost half of the total

length. The color pattern ranges from tricolored through bicolored

to almost monocolored. Color ranges from reddish (Sayal or Snuff

Brown) to grayish in summer pelage and from black to light gray

in winter. Diagnostic dental characters include: 3rd upper unicuspid

smaller than 4th, and unicuspids, except 5th, with a pigmented ridge

extending from near apex of each tooth medially to cingulum and

sometimes ending as internal cusplet. S. vagrans differs from members

[Pg 32]

of the ornatus group in less flattened skull, and in more ventrally

situated foramen magnum that encroaches more on the basioccipital

and less on the supraoccipital. The wandering shrew differs

from S. trowbridgii and S. saussurei in the dental characters

mentioned above. These dental characters also serve to distinguish

S. vagrans readily from S. cinereus, S. merriami, and S. arcticus

which may occur with vagrans. The large marsh shrew and water

shrew, S. palustris and S. bendiri, can be distinguished at a glance

from S. vagrans by larger size and darker color.

Fig. 15. Diagrammatic representation of the

probable phylogeny of Sorex vagrans and its near relatives.

In the following treatment of the 29 subspecies of Sorex vagrans,

the subspecies are arranged in geographic sequence, beginning with

the southernmost large subspecies on the California coast and proceeding

clockwise, north, east, south, and then west back to the

starting point.

Type.—Adult female, skin and skull; No. 19658, Mus. Vert. Zool.; obtained

on July 2, 1913, by Alfred C. Shelton, from Gualala, on the Sonoma County

side of the Gualala River, Sonoma Co., California.

Range.—Coastal California from Point Reyes north to Point Arena.

Diagnosis.—Size large; average and extreme measurements of 3 topotypes

are: total length, 141.7 (141-143); tail, 59 (54-63); hind foot, 17 (17-17).

Color reddish in summer, somewhat grayer in winter.

[Pg 33]

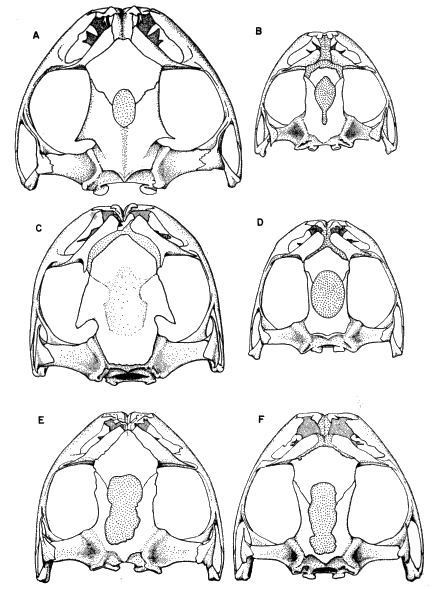

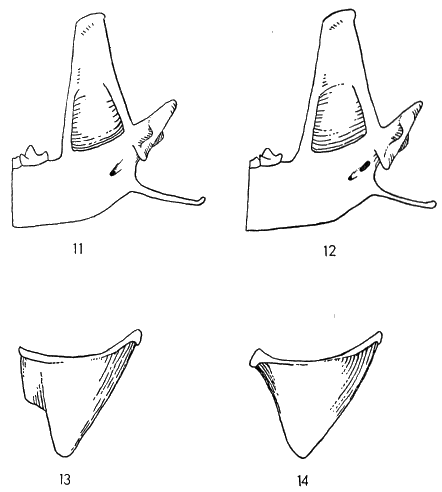

Fig. 16. Probable geographic ranges of 16

subspecies of Sorex vagrans.

| Guide to subspecies 1. S. v. shumaginensis 2. S. v. obscurus 3. S. v. alascensis 4. S. v. soperi 5. S. v. isolatus | 6. S. v. setosus 7. S. v. bairdi 8. S. v. permiliensis 9. S. v. yaquinae 10. S. v. pacificus 11. S. v. sonomae | 12. S. v. longiquus 13. S. v. parvidens 14. S. v. monticola 15. S. v. neomexicanus 16. S. v. orizabae |

[Pg 34]

Comparisons.—Differs from S. v. pacificus, with which it intergrades to the

north, in average smaller size and somewhat darker color; differs from the

sympatric S. v. vagrans in much larger size and more reddish color in both

summer and winter.

Remarks.—This subspecies inhabits the Transition Life-zone below 300 feet,

and occurs on moist ground in forests and beneath dense vegetation.

Marginal records.—California: Point Arena (Grinnell, 1933:82); Monte

Rio (Jackson, 1928:144); Inverness (Grinnell, 1933:82).

May 15, 1877.

Type.—Adult, sex unknown, skin and skull; No. 3266 U. S. Nat. Mus.; date

of capture unknown; received from E. P. Vollum and catalogued on March 8,

1858; obtained at Ft. Umpqua, mouth of Umpqua River, Douglas Co., Oregon.

Range.—Coast of California and Oregon from Mendocino north to Gardiner.

Diagnosis.—Size large, largest of the species; average and extreme measurements

of 8 specimens from Orick, Humboldt Co., California, are: total length,

143.1 (134-154); tail, 65.5 (59-72); hind foot, 17.5 (16-19). Color reddish

in summer, browner or grayer in winter.

Comparisons.—See account of S. v. sonomae for comparison with that subspecies;

averaging larger in all dimensions than S. v. yaquinae with which it

intergrades to the north; much larger and has more reddish than the sympatric

S. v. vagrans.

Remarks.—This subspecies occurs in the Canadian and Transition life-zones

below 1500 ft. where there is found moist ground in or adjacent to heavy

forests.

Specimens examined.—Total number, 76.

Oregon: Douglas Co.: Umpqua, 1 BS. Coos Co.: Marshfield, 1 BS;

Myrtle Point, 1 BS. Josephine Co.: Bolan Lake, 1 SGJ.

California: Del Norte Co.: Smith River, 2 BS; Gasquet, 4 BS; Crescent

City, 17 BS. Humboldt Co.: Orick, 13 BS; 1 mi. N Trinidad, 18 FC; Trinidad

Head, 1 BS; Carson's Camp, Mad River, Humboldt Bay, 5 BS; Arcata, 3 BS;

Cape Mendocino, 2 BS; 5 mi. S Dyerville, 1 BS. Mendocino Co.: Mendocino,

6 BS.

Marginal Records.—Oregon: Marshfield; Umpqua. California: Gasquet;

5 mi. S Dyerville; Mendocino, thence up coast to point of beginning.

29, 1918.

1936.

Type.—Adult female, skin and skull; No. 73051 U. S. Biol. Surv. Coll.,

obtained on July 18, 1895, by B. J. Bretherton, from Yaquina Bay, Lincoln Co.,

Oregon.

Diagnosis.—Size large for the species; average and extreme external measurements

[Pg 35]

of 11 specimens from Oakridge, Lane Co., Oregon, are: total length,

125.3 (11-136); tail, 55.1 (49-61); hind foot, 14.9 (14-16). Color reddish in

summer, browner or grayer in winter.

Comparisons.—See account of S. v. pacificus for comparison with that

subspecies. Larger and more reddish than S. v. bairdi with which it intergrades

to the north and east. Much larger and more reddish than the sympatric

S. v. vagrans.

Remarks.—The name yaquinae actually applies to a population of intergrades

between pacificus and bairdi. There is much variation over the range

of the subspecies, and individuals from the western and southern parts are

larger than those from the west slope of the Cascades. Specimens from Vida

and McKenzie Bridge are smaller than those from Mapleton, Mercer, and the

type locality but still seem closer to yaquinae than to topotypes of bairdi.

Between Marshfield and Umpqua on the one hand, and the Columbia River

and the Cascade Mountains on the other, the size of Sorex vagrans decreases

quite rapidly from the large pacificus to the smaller permiliensis. Size decreases

less rapidly northward along the coast than it does eastward toward the mountains;

consequently, at any given latitude, coastal shrews are larger than

mountain shrews. In this area of rapid change in size it is difficult to draw

subspecific boundaries between pacificus, yaquinae, and bairdi, and this must

be done somewhat arbitrarily.

Jackson (1928:141) remarked upon the possibility that intergradation

between pacificus and yaquinae took place. He noted also the close resemblance

between yaquinae and bairdi, and stated (loc. cit.) that specific affinity between

the two might be demonstrated with more specimens. He had a series

of eight specimens from Vida, Oregon, seven of which he assigned to S. o. bairdi

and one to yaquinae. I have examined these specimens and find no more

variation between the largest and the smallest than would be expected in any

normally variable series of shrews. Vernon Bailey (1936:364) arranged

yaquinae as a subspecies of pacificus without giving his reasons for so doing.

Specimens examined.—Total number, 65. Oregon: Lincoln Co.: type locality,

2 AW. Benton Co.: Philomath, 2 BS. Lane Co.: Mable, 1 OU; Vida,

4 BS, 1 OSC, 3 OU; McKenzie Bridge, 8 OSC, 3 AW, 17 OU, 2 SGJ; Mercer,

1 OSC, 1 OU; Mapleton, 3 BS; Oakridge, 11 OU. Douglas Co.: Gardiner,

2 BS; Elkhead, 1 BS. Klamath Co.: Crescent Lake, 3 OU.

Marginal Records.—Oregon: Yaquina Bay; Philomath; McKenzie Bridge;

Prospect (Jackson, 1928:140); Crescent Lake; Gardiner.

29, 1918.

Type.—Adult female, skin and skull; No. 17414/24318, U. S. Biol. Surv.

Coll.; obtained on August 2, 1889, by T. S. Palmer, from Astoria, Clatsop Co.,

Oregon.

Range.—Northwestern Oregon, south to Otis and east to Portland.

Diagnosis.—Size medium for the species; average and extreme external

measurements of 6 specimens from the type locality are: total length, 126.3

(124-130); tail, 55.0 (52-57); hind foot, 15.0 (14-15). Color Fuscous to Sepia

in summer, darker in winter, underparts buffy.

[Pg 36]

Comparisons.—For comparisons with yaquinae see account of that subspecies.

More reddish and larger than permiliensis with which bairdi intergrades to the

east; specimens from Portland show evidence of such intergradation. Some

specimens from southern Tillamook County show an approach to yaquinae.

Remarks.—S. v. bairdi lives primarily in forests as do yaquinae and pacificus.

Specimens examined.—Total number, 39. Oregon: Clatsop Co.: type locality,

12 BS; Seaside, 3 BS. Tillamook Co.: Netarts, 1 OU; Tillamook, 2 OSC;

Blaine, 1 AW; Hebo Lake, 1 SGJ; 5 mi. SW Cloverdale, 1 AW. Multnomah

Co.: Portland, 6 USNM. Lincoln Co.: Otis, 7 USNM; Delake, 1 KU. Lane

Co.: north slope Three Sisters, 6000 ft., 4 BS.

Marginal Records.—Oregon: type locality; Portland; north slope Three

Sisters; Taft (Macnab and Dirks, 1941:178).

November 29, 1918.

Type.—Adult male, skin and skull; No. 91048, U. S. Biol. Surv. Coll.;

obtained on October 2, 1897, by J. A. Loring from Permilia Lake, W base Mt.

Jefferson, Cascade Range, Marion Co., Oregon.

Range.—The Cascade Mountains of Oregon from Mt. Jefferson north to the

Columbia River.

Diagnosis.—Size medium for the species; average and extreme measurements

of 14 specimens from the type locality are: total length, 117.7 (110-124);

tail, 51.9 (45-58); hind foot, 14.0 (14-15). Pale reddish in summer, darker

and brownish in winter.

Comparisons.—For comparison with S. v. bairdi see account of that subspecies.

Larger than S. v. setosus except tail relatively shorter. More reddish

in summer pelage than setosus.

Remarks.—S. v. bairdi is larger in the southern part of its range than elsewhere.

Specimens from McKenzie Bridge, herein referred to yaquinae, are

intermediate in character between yaquinae and bairdi or between yaquinae

and permiliensis. The transition between yaquinae and bairdi is much more

gradual than between yaquinae and permiliensis.

Specimens examined.—Total number, 21. Oregon: Hood River Co.: Mt.

Hood, 2 BS. Wasco Co.: Camas Prairie, E base Cascade Mts., SE Mt. Hood,

1 BS. Marion Co.: Detroit, 1 BS; type locality, 17 BS.

Marginal Records.—Oregon: Mt. Hood; type locality; Detroit.

19, 1899.

29, 1918.

Type.—Adult male, skin and skull; No. 6213/238, Chicago Nat. Hist. Mus.;

obtained on August 18, 1898, by D. G. Elliott from Happy Lake, Olympic

Mts., Clallam Co., Washington.

Range.—Washington from the Cascades west; southwestern British Columbia

west of 120° W Longitude north to Lund.

Diagnosis.—Size medium for the species; average and extreme measurements

of 20 specimens from the Olympic Mountains, Washington, are: total length,

[Pg 37]

117.3 (107-125); tail, 49.8 (41-54); hind foot, 13.4 (12-14). Color dark in

both summer and winter.

Comparisons.—For comparison with permiliensis see account of that subspecies.

Darker, longer-tailed, and somewhat larger cranially than S. v. obscurus

with which it intergrades in southwestern British Columbia. Smaller in

all dimensions, but much the same color as S. v. longicauda with which it

intergrades along the British Columbian coast north of Lund. Larger, darker,

less reddish, and longer-tailed than the sympatric S. v. vagrans.

Remarks.—S. v. setosus lives mostly in forests. According to Dalquest

(1948:139) it is commonest at high altitudes in western Washington. In the

Hudsonian Life-zone where shrew habitat is more restricted and marginal than

it is at lower altitudes in the humid part of Washington, setosus might be expected

to compete with S. v. vagrans and to supplant it. Records of occurrence

in the Olympic Mountains suggest a degree of such separation there.

Specimens examined.—Total number, 135.

British Columbia: Lund, Malaspina Inlet, 4 BS; Gibson's Landing, 10 BS;

Port Moody, 19 BS; Langley, 2 BS; Chilliwack, 1 BS; Manning Park, 2 PMBC.

Washington: Whatcom Co.: Mt. Baker, 6 WSC; Barron, 1 BS. Chelan

Co.: Clovay Pass, 1 WSC; Stehekin, 6 (4 WSC, 2 BS); Cascade Tunnel,

1 WSC. King Co.: Scenic, 1 WSC. Kittitas Co.: Lake Kachess, 1 WSC;

Easton, 10 BS. Clallam Co.: 8 mi. W Sekin River, 1 WSC; mouth of Sekin

River, 1 WSC; Clallam Bay, 1 CMNH; 7 mi. W Port Angeles, 1 WSC; Ozette

Lake, 1 CMNH; 12 mi. S Port Angeles, 4 WSC; Forks, 1 CMNH; Deer Lake,

7 CMNH; Hoh Lake, 1 CMNH; Bogachiel Peak, 1 CMNH; Sol Duc Hot

Springs, 3 CMNH; Sol Duc Park, 1 CMNH; Canyon Creek, 1 WSC; Sol Duc

Divide, 2 WSC; Cat Creek, 2 WSC. Jefferson Co.: Jackson Ranger Station,

1 CMNH; Mt. Kimta, 2 CMNH; Reflection Lake, 6 CMNH; Blue Glacier,

3 CMNH. Gray's Harbor Co.: Westport, 1 WSC. Pierce Co.: Fort Lewis,

1 FC; Mt. Rainier, 19 (16 BS, 3 WSC). Pacific Co.: Tokeland, 2 BS. Yakima

Co.: Gotchen Creek, 3 WSC; Mt. Adams, 1 WSC. Skamania Co.: Mt. St.

Helens, 1.

Oregon: Hood River Co.: 2 mi. W Parkdale, 2 BS.

Marginal Records.—British Columbia: Rivers Inlet (Anderson, 1947:20);

Agassiz (Jackson, 1928:136); Chilliwack Lake. Washington: Barron; Lyman

Lake (Jackson, 1928:137); Mt. Stuart (Dalquest, 1948:141); Mt. Adams.

Oregon: 2 mi. W Parkdale. Washington: Ilwaco (Jackson, 1928:137);

Lund, Malaspina Inlet.

31, 1895.

Type.—Adult male, skin and skull; No. 74711, U. S. Biol. Surv. Coll.; obtained

on September 9, 1895 by C. P. Streator, from Wrangell, Alaska.

Range.—The British Columbian and Alaskan coasts from Rivers Inlet north

to near Juneau and also certain islands including Etolin, Gravina, Revillagigedo,

Sergeif, and Wrangell.

Diagnosis.—Size medium for the species, tail relatively long; average and

extreme measurements of 17 specimens from the type locality are: total length,

128.4 (122-138); tail, 57.8 (53-66); hind foot, 15.1 (14-16). Color dark in

summer and winter.

Comparisons.—For comparison with S. v. setosus see account of that subspecies.

Larger and darker than S. v. obscurus with which it intergrades east

of the humid coastal region; larger and darker than S. v. alascensis with which

[Pg 38]

it intergrades in the Lynn Canal area; larger and darker than S. v. calvertensis