The Project Gutenberg eBook of For the Sake of the School

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: For the Sake of the School

Author: Angela Brazil

Release date: March 3, 2007 [eBook #20730]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Marc Hens, Suzanne Shell, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOR THE SAKE OF THE SCHOOL ***

E-text prepared by Marc Hens, Suzanne Shell,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(https://www.pgdp.net/c/)

For the Sake of the School

BLACKIE & SON LIMITED

16/18 William IV Street, Charing Cross, London, W.C.2

17 Stanhope Street, Glasgow

BLACKIE & SON (INDIA) LIMITED

103/5 Fort Street, Bombay

BLACKIE & SON (CANADA) LIMITED

Toronto

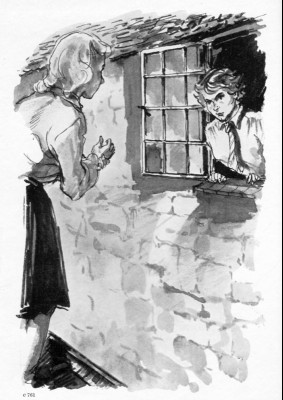

"I felt I must speak to you"

Page 234

Frontispiece

For the Sake of the

School

by

Angela Brazil

Author of "The School on the Loch"

"The School at the Turrets", &c.

With Frontispiece

BLACKIE & SON LIMITED

LONDON AND GLASGOW

Printed in Great Britain by Blackie & Son, Ltd., Glasgow

TO THE

SCHOOLGIRL READERS

WHO HAVE SENT ME

SUCH NICE LETTERS

Contents

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | The Woodlands | 11 |

| II. | A Friend from the Bush | 24 |

| III. | Round the Camp-fire | 36 |

| IV. | A Blackberry Foray | 51 |

| V. | On Sufferance | 66 |

| VI. | Quits | 77 |

| VII. | The Cuckoo's Progress | 87 |

| VIII. | The "Stunt" | 104 |

| IX. | A January Picnic | 117 |

| X. | Trespassers Beware! | 130 |

| XI. | Rona receives News | 142 |

| XII. | Sentry Duty | 156 |

| XIII. | Under Canvas | 170 |

| XIV. | Susannah Maude | 183 |

| XV. | A Point of Honour | 194 |

| XVI. | Amateur Conjuring | 208 |

| XVII. | A Storm-cloud | 221 |

| XVIII. | Light | 233 |

| XIX. | A Surprise | 249 |

[Pg 11]

FOR THE SAKE OF THE SCHOOL

CHAPTER I

The Woodlands

"Are they never going to turn up?"

"It's almost four now!"

"They'll be left till the six-thirty!"

"Oh, don't alarm yourself! The valley train

always waits for the express."

"It's coming in now!"

"Oh, good, so it is!"

"Late by twenty minutes exactly!"

"Stand back there!" yelled a porter, setting

down a box with a slam, and motioning the excited,

fluttering group of girls to a position of greater

safety than the extreme edge of the platform.

"Llangarmon Junction! Change for Glanafon

and Graigwen!"

Snorting and puffing, as if in agitated apology

for the tardiness of its arrival, the train came

steaming into the station, the drag of its brakes[Pg 12]

adding yet another item of noise to the prevailing

babel. Intending passengers clutched bags and

baskets; fathers of families gave a last eye to the

luggage; mothers grasped children firmly by the

hand; a distracted youth, seeking vainly for his

portmanteau, upset a stack of bicycles with a crash;

while above all the din and turmoil rose the strident,

rasping voice of a book-stall boy, crying his

selection of papers with ear-splitting zeal.

From the windows of the in-coming express

waved seventeen agitated pocket-handkerchiefs, and

the signal was answered by a counter-display of

cambric from the twenty girls hustled back by an

inspector in the direction of the weighing-machine.

"There's Helen!"

"And Ruth, surely!"

"Oh! where's Marjorie?"

"There! Can't you see her, with Doris?"

"That's Mamie, waving to me!"

"What's become of Kathleen?"

One moment more, and the neat school hats of

the new-comers had swelled the group of similar

school hats already collected on the platform;

ecstatic greetings were exchanged, urgent questions

asked and hasty answers given, and items

of choice information poured forth with the utmost

volubility of which the English tongue is capable.

Urged by brief directions from a mistress in charge,

the chattering crew surged towards a siding, and

made for a particular corridor carriage marked

"Reserved". Here handbags, umbrellas, wraps,

and lunch-baskets were hastily stowed away in the[Pg 13]

racks, and, Miss Moseley having assured herself

that not a single lamb of her flock was left behind,

the grinning porter slammed the doors, the green

flag waved, and the local train, long overdue,

started with a jerk for the Craigwen Valley.

Past the grey old castle that looked seawards

over the estuary, past the little white town of

Llangarmon, with its ancient walls and fortified

gates, past the quay where the fishing smacks were

lying idly at anchor and a pleasure-steamer was

unloading its human cargo, past the long stretch

of sandy common, where the white tents of the

Territorials evoked an outcry of interest, then up

alongside the broad tidal river towards where the

mountains, faint and misty, rose shouldering one

another till they merged into the white nebulous

region of the cloud-flecked sky. Those lucky ones

who had secured window seats on the river side

of the carriage were loud in their acclamations of

satisfaction as familiar objects in the landscape

came into sight.

"There's Cwm Dinas. I wish they could float

a big Union Jack on the summit."

"It would be a landmark all right."

"Oh, the flag's up at Plas Cafn!"

"We'll have one at school this term?"

"Oh, I say! Move a scrap," pleaded Ulyth

Stanton plaintively. "We only get fields and

woods on our side. I can't see anything at all

for your heads. You might move. What selfish

pigs you are! Well, I don't care; I'm going to

talk."[Pg 14]

"You have been talking already. You've never

stopped, in fact," remarked Beth Broadway, proffering

a swiftly disappearing packet of pear drops

with a generosity born of the knowledge that all

sweets would be confiscated on arrival at The

Woodlands.

"I know I have, but that was merely by the

way. It wasn't anything very particular, and I've

got something I want to tell you—something

fearfully important. Absolutely super! D'you

know, she's actually coming to school. Isn't it

great? She's to be my room-mate. I'm just

wild to see her. I hope her ship won't be stopped

by storms."

"By the Muses, whom are you talking about?"

"'She' means the cat," sniggered Gertrude

Oliver.

"Why! can't you guess? What stupids you

are! It's Rona, of course—Rona Mitchell from

New Zealand."

"You're ragging!"

"It's a fact. It is indeed!"

The incredulity on the countenances of her companions

having yielded to an expression of interest,

Ulyth continued her information with increased

zest, and a conscious though would-be nonchalant

air of importance.

"Her father wants her to go to school in England,

so he decided to send her to The Woodlands,

so that she might be with me!"

"Do you mean that girl you were so very

proud of corresponding with? I forget how the[Pg 15]

whole business began," broke in Stephanie Radford.

"Don't you remember? It was through a magazine

we take. The editor arranged for readers

of the magazine in England to exchange letters

with other readers overseas. He gave me Rona.

We've been writing to each other every month for

two years."

"I had an Australian, but she wouldn't write

regularly, so we dropped it," volunteered Beth

Broadway. "I believe Gertrude had somebody

too."

"Yes, a girl in Canada. I never got farther

than one short letter and a picture post card,

though. I do so loathe writing," sighed Gertrude.

"Ulyth's the only one who's kept the thing up."

"And do you mean to say this New Zealander's

actually coming to our school?" asked Stephanie.

"That's the joysome gist of my remarks! I

can't tell you how I'm pining and yearning to see

her. She seems like a girl out of a story. To think

of it! Rona Mitchell at school with us!"

"Suppose you don't like her?"

"Oh, I'm certain I shall! She's written me the

jolliest, loveliest, funniest letters! I feel I know

her already. We shall be the very best of friends.

Her father has a huge farm of I can't tell you

how many miles, and she has two horses of her

own, and fords rivers when she's out riding."

"When's she to arrive?"

"Probably to-morrow. She's travelling by the

King George, and coming up straight from London[Pg 16]

to school directly she lands. I hope she's got to

England safely. She must have left home ever

such a long time ago. How fearfully exciting for

her to——"

But here Ulyth's reflections were brought to an

abrupt close, for the train was approaching Glanafon

Ferry, and her comrades, busily collecting

their various handbags, would lend no further ear

to her remarks.

The little wayside station, erstwhile the quietest

and sleepiest on the line, was soon overflowing with

girls and their belongings. Miss Moseley flitted

up and down the platform, marshalling her charges

like a faithful collie, the one porter did his slow

best, and after a few agitated returns to the compartments

for forgotten articles, everything was

successfully collected, and the train went steaming

away down the valley in the direction of Craigwen.

It seemed to take the last link of civilization with

it, and to leave only the pure, unsullied country

behind. The girls crossed the line and walked

through the white station gate with pleased anticipation

writ large on their faces. It was the cult at

The Woodlands to idolize nature and the picturesque,

and they had reached a part of their journey

which was a particular source of pride to the school.

Any admirer of scenery would have been struck

with the lovely and romantic view which burst

upon the eye as the travellers left the platform at

Glanafon and walked down the short, grassy road

that led to the ferry. To the south stretched the

wide pool of the river, blue as the heaven above[Pg 17]

where it caught the reflection of the September

sky, but dark and mysterious where it mirrored

the thick woods that shaded its banks. Near at

hand towered the tall, heather-crowned crag of

Cwm Dinas, while the rugged peaks of Penllwyd

and Penglaslyn frowned in majesty of clouds beyond.

The ferry itself was one of those delightful

survivals of mediævalism which linger here and

there in a few fortunate corners of our isles. A

large flat-bottomed boat was slung on chains which

spanned the river, and could be worked slowly

across the water by means of a small windlass.

Though it was perfectly possible, and often even

more convenient, to drive to the school direct from

Llangarmon Junction, so great was the popular

feeling in favour of arrival by the ferry that at the

autumn and spring reunions the girls were allowed

to avail themselves of the branch railway and approach

The Woodlands by way of the river.

They now hurried on to the boat as if anticipating

a pleasure-jaunt. The capacities of the flat

were designed to accommodate a flock of sheep or

a farm wagon and horses, so there was room and

to spare even for thirty-seven girls and their hand

luggage. Evan Davis, the crusty old ferryman,

greeted them with his usual inarticulate grunt, a

kind of "Oh, here you are again, are you!" form

of welcome which was more forceful than gracious.

He linked the protecting chains carefully across

the end of the boat, called out a remark in Welsh

to his son, Griffith, and, seizing the handle, began

to work the windlass. Very slowly and leisurely[Pg 18]

the flat swung out into the river. The tide was

at the full and the wide expanse of water seemed

like a lake. The clanking chains brought up

bunches of seaweed and river grass which fell with

an oozy thud upon the deck. The mountain air,

blowing straight from Penllwyd, was tinged with

ozone from the tide. The girls stood looking up

the reach of water towards the hills, and tasting

the salt on their lips with supreme gratification.

It was not every school that assembled by such a

romantic means of conveyance as an ancient flat-bottomed

ferry-boat, and they rejoiced over their

privileges.

"I'm glad the tide's full; it makes the crossing

so much wider," murmured Helen Cooper, with an

eye of admiration on the woods.

"Don't suppose Evan shares your enthusiasm,"

laughed Marjorie Earnshaw. "He's paid the same,

whatever the length of the journey."

"Old Grumps gets half a crown for his job, so

he needn't grumble," put in Doris Deane.

"Oh, trust him! He'd look sour at a pound note."

"What makes him so cross?"

"Oh, he's old and lame, I suppose, and has a

crotchety temper."

"Here we are at last!"

The boat was grating on the shore. Griffith was

unfastening the movable end, and in another moment

the girls were springing out gingerly, one

by one, on to the decidedly muddy stepping-stones

that formed a rough causeway to the bank. A cart

was waiting to convey the handbags (all boxes had[Pg 19]

been sent as "advance luggage" two days before),

so, disencumbered of their numerous possessions,

the girls started to walk the steep uphill mile that

led to The Woodlands.

Miss Bowes and Miss Teddington, the partners

who owned the school, had been exceptionally fortunate

in their choice of a house. If, as runs the

modern theory, beautiful surroundings in our early

youth are of the utmost importance in training our

perceptions and aiding the growth of our higher

selves, then surely nowhere in the British Isles

could a more suitable setting have been found for

a home of education. The long terrace commanded

a view of the whole of the Craigwen Valley, an

expanse of about sixteen miles. The river, like a

silver ribbon, wound through woods and marshland

till it widened into a broad tidal estuary as

it neared the sea. The mountains, which rose tier

after tier from the level green meadows, had their

lower slopes thickly clothed with pines and larches;

but where they towered above the level of a thousand

feet the forest growth gave way to gorse and

bracken, and their jagged summits, bare of all

vegetation save a few clumps of coarse grass,

showed a splintered, weather-worn outline against

the sky. Penllwyd, Penglaslyn, and Glyder Garmon,

those lofty peaks like three strong Welsh

giants, seemed to guard the entrance to the enchanted

valley, and to keep it a place apart, a last

fortress of nature, a sanctuary for birds and flowers,

a paradise of green shade and leaping waters, and

a breathing-space for body and soul.[Pg 20]

The house, named "The Woodlands" by Miss

Bowes in place of its older but rather unpronounceable

name of Llwyngwrydd (the green grove),

took both its Welsh and English appellations from

a beautiful glade, planted with oaks, which formed

the southern boundary of the property. Through

this park-like dell flowed a mountain stream, tumbling

in little white cascades between the big

boulders that formed its bed, and pouring in quite

a waterfall over a ledge of rock into a wide pool.

Its steady rippling murmur never stopped, and

could be heard day and night through the ever-open

windows, gentle and subdued in dry weather,

but rising to a roar when rain in the hills brought

the flood down in a turbulent torrent.

Through lessons, play, or dreams this sound of

many waters was ever present; it gave an atmosphere

to the school which, if passed unnoticed

through extreme familiarity, would have been instantly

missed if it could have stopped. To the

girls this stream was a kind of guardian deity, with

the glade for its sacred grove. They loved every

rock and stone and cataract, almost every patch of

brown moss upon its boulders. Each morning of

the summer term they bathed before breakfast in

the pool where a big oak-tree shaded the cataract.

It was so close to the house that they could run out

in mackintoshes, and so retired that it resembled

a private swimming-bath. Here they enjoyed

themselves like water-nymphs, splashing in the

shallows, plunging in the pool, swinging from the

boughs of the oak-tree, and scrambling over the[Pg 21]

lichened boulders. It was a source of deep regret

to the hardier spirits that they were not allowed to

take their morning dip in the stream all the year

round; but on that score mistresses were adamant,

and with the close of September the naiads perforce

withdrew from their favourite element till it

was warmed again by the May sunshine.

The house itself had originally been an ancient

Welsh dwelling of the days of the Tudors, but had

been largely added to in later times. The straight

front, with its rows of windows, classic doorway,

and stone-balustraded terrace, was certainly Georgian

in type, and the tower, an architectural eyesore,

was plainly Victorian. The taste of the early

nineteenth century had not been faultless, and all

the best part of the building, from an artistic point

of view, lay at the back. This mainly consisted of

kitchens and servants' quarters, but there still remained

a large hall, which was the chief glory of

the establishment. It was very lofty, for in common

with other specimens of the period it had no upper

story, the roof being timbered like that of a church.

The walls were panelled with oak to a height of

about eight feet, and above that were decorated

with elaborate designs in plaster relief, representing

lions, wild boars, stags, unicorns, and other

heraldic devices from the coat-of-arms of the original

owner of the estate. A narrow winding staircase

led to a minstrels' gallery, from which was suspended

a wooden shield emblazoned with the Welsh

dragon and the national motto, "Cymru am byth"

("Wales for ever").[Pg 22]

If the hall was the main picturesque asset of the

building, it must be admitted that the unromantic

front portion was highly convenient, and had been

most readily adaptable for a school. The large

light rooms of the ground floor made excellent

classrooms, and the upper story was so lavishly

provided with windows that it had been possible,

by means of wooden partitions, to turn the great

bedrooms into rows of small dormitories, each

capable of accommodating two girls.

The bright airy house, the terrace with its glorious

view of the valley, the large old-fashioned garden,

and, above all, the stream and the glade made a

very pleasant setting for the school life of the forty-eight

pupils at The Woodlands. The two principals

worked together in perfect harmony. Each had

her own department. Miss Bowes, who was short,

stout, grey-haired, and motherly, looked after the

housekeeping, the hygiene, and the business side.

She wrote letters to parents, kept the accounts,

interviewed tradespeople, superintended the mending,

and was the final referee in all matters pertaining

to health and general conduct. "Dear Old

Rainbow", as the girls nicknamed her, was frankly

popular, for she was sympathetic and usually disposed

to listen, in reason, to the various plaints

which were brought to the sanctum of her private

sitting-room. Her authority alone could excuse

preparation, order breakfast in bed, remit practising,

dispense jujubes, allow special festivities, and

grant half-holidays. It was rumoured that she

thought of retiring and leaving the school to her[Pg 23]

partner, and such a report always drew from parents

the opinion that she would be greatly missed.

Miss Teddington, younger by many years, took

a more active part in the teaching, and superintended

the games and outdoor sports. She was

tall and athletic, a good mathematician, and interested

in archæology and nature study. She led

the walks and rambles, taught the Sixth Form, and

represented the more scholastic and modern element.

Her enterprise initiated all fresh undertakings, and

her enthusiasm carried them forward with success.

"Hard-as-nails" the girls sometimes called her, for

she coddled nobody and expected the utmost from

each one's capacity. If she was rather uncompromising,

however, she was just, and a strong

vein of humour toned down much of the severity

of her remarks. To be chided by a person whose

eye is capable of twinkling takes part of the sting

from the reprimand, and the general verdict of the

school was to the effect that "Teddie was a keen

old watch-dog, but her bark was worse than her

bite."

Of the other mistresses and girls we will say more

anon. Having introduced my readers to The Woodlands,

it is time for the story to begin.

[Pg 24]

CHAPTER II

A Friend from the Bush

Ulyth Stanton was a decided personality in the

Lower Fifth. If not exactly pretty, she was a dainty

little damsel, and knew how to make the best of herself.

Her fair hair was glossy and waved in the most

becoming fashion, her clothes were well cut, her

gloves and shoes immaculate. She had an artistic

temperament, and loved to be surrounded by pretty

things. She was rather a favourite at The Woodlands,

for she had few sharp angles and possessed

a fair share of tact. If the girls laughed sometimes

at what they called her "high-falutin' notions"

they nevertheless respected her opinions and admired

her more than they always chose to admit.

It was an accepted fact that Ulyth stuck to her word

and generally carried through anything that she once

undertook. She alone of six members of her form

who had begun to correspond with girls abroad, at

the instigation of the magazine editor, had written

regularly, and had cultivated the overseas friendship

with enthusiasm. The element of romance

about the affair had appealed to Ulyth. It was

so strange to receive letters from someone you had

never seen. To be sure, Rona had only given a

somewhat bald account of her home and her doings,[Pg 25]

but even this outline was so different from English

life that Ulyth's imagination filled the gaps, and

pictured her unknown correspondent among scenes

of unrivalled interest and excitement. Ulyth had

once seen a most wonderful film entitled "Rose

of the Wilderness", and though the scenes depicted

were supposed to be in the region of the Wild

West, she decided that they would equally well

represent the backwoods of New Zealand, and

that the beautiful, dashing, daring heroine, so

aptly called "the Prairie Flower", was probably

a speaking likeness of Rona Mitchell. When she

learnt that owing to her letters Rona's father had

determined to send his daughter to school at The

Woodlands, her excitement was immense. She

had at once petitioned Miss Bowes to have her as a

room-mate, and was now awaiting her advent with

the very keenest anticipation.

There was a little uncertainty about the time of

the new girl's arrival, for it depended upon the

punctuality of the ocean liner, a doubtful matter if

there were a storm; and the feeling that she might

be expected any hour between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m.

made havoc of Ulyth's day. It was impossible to

attend to lessons when she was listening for the

sound of a taxi on the drive, and even the attractions

of tennis could not decoy her out of sight of the

front door.

"I must be the very first to welcome her," she

persisted. "Of course it's not the same to all the

rest of you—I understand that. She's to be my

special property, my Prairie Rose!"[Pg 26]

"All serene! If you care to waste your time

lounging about the steps you can. We're not in

such a frantic state to see your paragon," laughed

the girls as they ran down the garden to the courts.

After all, the waiting was in vain. Tea-time came

without a sign of the new-comer. It was unlikely

that she would turn up now until the evening train,

and Ulyth resigned herself to the inevitable. But

when the school was almost half-way through its

bread and butter and gooseberry jam, a sudden

commotion occurred in the hall. There was a noise

such as nobody ever remembered to have heard at

The Woodlands before.

"Thank goodness gracious I've got meself here

at last!" cried a loud nasal voice. "Where'll I

stick these things? Oh yes, there's heaps more

inside that automobile! Travelling's no joke, I

can tell you; I'm tired to death. Any tea about?

I could drink the sea. My gracious, I've had a

time of it coming here!"

At the first word Miss Bowes had glided from

the room, and the voice died away as the door of

her private study closed. Sounds suggestive of the

carrying upstairs of luggage followed, and a hinnying

laugh echoed once down the stairs. The girls

looked at one another; there was a shadow in

Ulyth's eyes. She did not share in the general

smile that passed round the table, and she finished

her tea in dead silence.

"Going to sample your new property?" whispered

Mary Acton as the girls pushed back their

chairs.[Pg 27]

"What's the formula for swearing an undying

friendship?" giggled Addie Knighton.

"Was it Rose of Sharon you called her?"

twinkled Christine Crosswood. "Or Lily of the

Valley?"

Ulyth did not reply. She walked upstairs very

slowly. The nasal twang of that high-pitched

voice in the hall had wiped the bloom off her

anticipation. The small double dormitory in which

she slept was No. 3, Room 5. The door was half-open,

so she entered without knocking. Both beds,

the chairs, and most of the floor was strewn with an

assortment of miscellaneous articles. On the dressing-table

was a tray with the remains of tea. Over

a large cabin trunk bent a girl of fourteen. She

straightened herself as she heard footsteps.

Alas! alas! for Ulyth's illusions. The enchanting

vision of the prairie flower faded, and Rona

Mitchell stood before her in solid fact. Solid was

the word for it—no fascinating cinema heroine this,

but an ordinary, well-grown, decidedly plump

damsel with brown elf locks, a ruddy sunburnt

complexion, and a freckled nose.

Where, oh, where, were the delicate features,

the fairy-like figure, and the long rich clustering

curls of Rose of the Wilderness? Ulyth stood for

a moment gazing as one dazed; then, with an effort,

she remembered her manners and introduced herself.

"Proud to meet you at last," replied the new-comer

heartily. "You and I've had a friendship

switched on for us ready-made, so to speak. I[Pg 28]

liked your letters awfully. Glad they've put us in

together."

"Did—did you have a nice journey?" stammered

Ulyth.

It was a most conventional enquiry, but the only

thing she could think of to say.

"Beastly! It was rough or hot all the time, and

we didn't get much fun on board. Wasn't it a sell?

Too disappointing for words! Mrs. Perkins, the

lady who had charge of me coming over, was just

a Tartar. Nothing I did seemed to suit her somehow.

I bet she was glad to see the last of me.

Then I was sea-sick, and when we got into the

hot zone—my, how bad I was! My face was just

skinned with sunburn, and the salt air made it

worse. I'd not go to sea again for pleasure, I can

tell you. I say, I'll be glad to get my things fixed

up here."

"This is your bed and your side of the room,"

returned Ulyth hastily, collecting some of the articles

which had been flung anywhere, and hanging them

in Rona's wardrobe; "Miss Moseley makes us be

very tidy. She'll be coming round this evening to

inspect."

Rona whistled.

"Guess she'll drop on me pretty often then!

No one's ever called neatness my strong point.

Are those photos on the mantelpiece your home

folks? I'm going to look at them. What a lot of

things you've got: books, and albums, and goodness

knows what! I'll enjoy turning them over

when I've time."[Pg 29]

At half-past eight that night a few members of

the Lower Fifth, putting away books in their classroom,

stopped to compare notes.

"Well, what do you think of your adorable one,

Ulyth?" asked Stephanie Radford, a little spitefully.

"You're welcome to her company so far as

I'm concerned."

"Rose of the Wilderness, indeed!" mocked

Merle Denham.

"Your prairie rose is nothing but a dandelion!"

remarked Christine Crosswood.

"I never heard anyone with such an awful laugh,"

said Lizzie Lonsdale.

"Don't!" implored Ulyth tragically. "I've had

the shock of my life. She's—oh, she's too terrible

for words! Her voice makes me cringe. And she

pawed all my things. She snatched up my photos,

and turned over my books with sticky fingers; she

even opened my drawers and peeped inside."

"What cheek!"

"Oh, she hasn't the slightest idea of how to behave

herself! She asked me a whole string of the

most impertinent questions: what I'd paid for my

clothes, and how long they'd have to last me. She's

unbearable. Yes, absolutely impossible. Ugh!

and I've got to sleep in the same room with her

to-night."

"Poor martyr, it's hard luck," sympathized

Lizzie. "Why did you write and ask the Rainbow

to put you together? It was rather buying a

pig in a poke, wasn't it?"

"I never dreamt she'd be like this. It sounded[Pg 30]

so romantic, you see, living on a huge farm, and

having two horses to ride. I shall go to Miss

Bowes, first thing to-morrow morning, and ask to

have her moved out of my room. I only wish there

was time to do it this evening. Oh, why did I

ever write to her and make her want to come to this

school?"

"Poor old Ulyth! You've certainly let yourself

in for more than you bargained for," laughed the

girls, half sorry for her and half amused.

Next morning, after breakfast, the very instant

that Miss Bowes was installed in her study, a "rap-tap-tap"

sounded on her door.

"Come in!" she called, and sighed as Ulyth

entered, for she had a shrewd suspicion of what she

was about to hear.

"Please, Miss Bowes, I'm sorry to have to ask

a favour, but may Rona be changed into another

dormitory?"

"Why, Ulyth, you wrote to me specially and

asked if you might have her for a room-mate!"

"Yes, I did; but I hadn't seen her then. I

thought she'd be so different."

"Isn't it a little too soon to judge? You haven't

known her twenty-four hours yet."

"I know as much of her as I ever want to. Oh,

Miss Bowes, she's dreadful! I'll never like her.

I can't have her in my room—I simply can't!"

There was a shake, suggestive of tears, in Ulyth's

voice. Her eyes looked heavy, as if she had not

slept. Miss Bowes sighed again.

"Rona mayn't be exactly what you imagined,[Pg 31]

but you must remember in what different circumstances

she has been brought up. I think she has

many good qualities, and that she'll soon improve.

Now let us look at the matter from her point of

view. You have been writing to her constantly for

two years. She has come here specially to be near

you. You are her only friend in a new and strange

country where she is many thousand miles away

from her own home. You gave her a cordial invitation

to England, and now, because she does not

happen to realize your quite unfounded expectations,

you want to back out of all your obligations to her.

I thought you were a girl, Ulyth, who kept her

promises."

Ulyth fingered the corner of the tablecloth nervously

for a moment, then she burst out:

"I can't, Miss Bowes, I simply can't. If you

knew how she grates upon me! Oh, it's too much!

I'd rather have a bear cub or a monkey for a room-mate!

Please, please don't make us stop together!

If you won't move her, move me! I'd sleep in an

attic if I could have it to myself."

"You must stay where you are until the end of

the week. You owe that to Rona, at any rate.

Afterwards I shall not force you, but leave it to

your own good feeling. I want you to think over

what I have been saying. You can come on

Sunday morning and tell me your decision."

"I know what the answer will be," murmured

Ulyth, as she went from the room.

She was very angry with Miss Bowes, with

Rona, and with herself for her own folly.[Pg 32]

"It's ridiculous to expect me to take up this

savage," she argued. "And too bad of Miss

Bowes to make out that I'm breaking my word.

Oh dear! what am I to write home to Mother?

How can I tell her? I believe I'll just send her a

picture post card, and only say Rona has come, and

no more. Miss Bowes has no right to coerce me.

I'll make my own friends. No, I've quite made up

my mind she shan't cram Rona down my throat.

To have that awful girl eternally in my bedroom—I

should die!"

After all her heroics it was a terrible come-down

for poor Ulyth now the actual had taken the place

of the sentimental. Her class-mates could not forbear

teasing her a little. It was too bad of them;

but then they had resented her entire pre-appropriation

of the new-comer, and, moreover, had one or

two old scores from last term to pay off. Ulyth

began to detest the very name of "the Prairie

Flower". She wondered how she could ever have

been so silly.

"I ought to have been warned," she thought,

trying to throw the blame on to somebody else.

"No one ever suggested she'd be like this. The

editor of the magazine really shouldn't have persuaded

us to write. It's all his fault in the beginning."

Though the rest of the girls were scarcely impressed

with Rona's personality, they were not

utterly repelled.

"She's rather pretty," ventured Lizzie Lonsdale.

"Her eyes are the bluest I've ever seen."[Pg 33]

"And her teeth are so white and even," added

Beth Broadway. "She looks jolly when she

smiles."

"Perhaps she'll smarten up soon," suggested

Addie Knighton. "That blue dress suits her; it

just matches her eyes."

To Ulyth's fastidious taste Rona's clothes looked

hopelessly ill-cut and colonial, especially as her

room-mate put them on anyhow, and seemed to

have no regard at all for appearances. A girl

who did not mind whether she looked really trim,

spruce and smart, must indeed have spent her life

in the backwoods.

"Didn't you even have a governess in New Zealand?"

she ventured one day. She did not encourage

Rona to talk, but for once her curiosity

overcame her dislike of the high-pitched voice.

"Couldn't get one to stop up-country, where we

were. Mrs. Barker, our cowman's wife, looked

after me ever since Mother died. She was the only

woman about the place. One of our farm helps

taught me lessons. He was a B.A. of Oxford, but

down on his luck. Dad said I'd seem queer to

English girls. I don't know that I care."

Though Rona might not be possessed of the

most delicate perceptions, she nevertheless had

common sense enough to realize that Ulyth did

not receive her with enthusiasm.

"I suppose you're disappointed in me?" she

queried. "Dad said you would be, but I laughed

at him. Pity if our ready-made friendship turned

out a misfit! I think you're no end! Dad said I'd[Pg 34]

got to copy you; it'll take me all my time, I expect.

Things are so different here from home."

Was there a suspicion of a choke in the words?

Ulyth had a sudden pang of compunction. Unwelcome

as her companion was to her, she did not

wish to be brutal.

"You mustn't get home-sick," she said hastily.

"You'll shake down here in time. Everyone finds

things strange at school just at first. I did myself."

"I guess you were never as much a fish out of

water as me, though," returned Rona, and went

whistling down the passage.

Ulyth tried to dismiss her from her thoughts.

She did not intend to worry over Rona more than

she could possibly help. Fortunately they were

not together in class, for Rona's entrance-examination

papers had not reached the standard of the

Lower Fifth, and she had been placed in IV b.

Ulyth was interested in her school-work. She

stood well with her teachers, and was an acknowledged

force in her form. She came from a very

refined and cultured home, where intellectual interests

were cultivated both by father and mother.

Her temperament was naturally artistic; she was

an omnivorous reader, and could devour anything

in the shape of literature that came her way. The

bookcase in her dormitory was filled with beautiful

volumes, mostly Christmas and birthday gifts.

She rejoiced in their soft leather bindings or fine

illustrations with a true book-lover's enthusiasm.

It was her pride to keep them in daintiest condition.

Dog-ears or thumb-marks were in her[Pg 35]

opinion the depths of degradation. Ulyth had

ambitions also, ambitions which she would not

reveal to anybody. Some day she planned to write

a book of her own. She had not yet fixed on a

subject, but she had decided just what the cover

was to be like, with her name on it in gilt letters.

Perhaps she might even illustrate it herself, for her

love of art almost equalled her love of literature;

but that was still in the clouds, and must wait till

she had chosen her plot. In the interim she wrote

verses and short stories for the school magazine,

and her essays for Miss Teddington were generally

returned marked "highly creditable".

This term Ulyth intended to study hard. It was

a promotion to be in the Upper School; she was

beginning several new subjects, and her interest in

many things was aroused. It would be a delightful

autumn as soon as she had got rid of this dreadful

problem, at present the one serious obstacle to her

comfort. But in the meantime it was only Friday,

and till at least the following Monday she would be

obliged to endure her uncongenial presence in her

bedroom.

[Pg 36]

CHAPTER III

Round the Camp-fire

It was the first Saturday of the term. So far the

girls had been kept busily occupied settling down

to work in their fresh forms, and trying to grow

accustomed to Miss Teddington's new time-tables.

Now, however, they were free to relax and enjoy

themselves in any way they chose. Some were

playing tennis, some had gone for a walk with

Miss Moseley, a few were squatting frog-like on

boulders in the midst of the stream, and others

strolled under the trees in the grove.

"Thank goodness the weather's behaving itself!"

said Mary Acton, who, with a few other members

of the Lower Fifth, was sitting on the trunk of a

fallen oak. "Do you remember last council? It

simply poured. The thing's no fun if one can't

have a real fire."

"It'll burn first-rate to-night," returned Lizzie

Lonsdale. "There's a little wind, and the wood'll

be dry."

"That reminds me I haven't found my faggot

yet," said Beth Broadway easily.

"Girl alive! Then you'd better go and look for

one, or you'll be all in a scramble at the last!"

"Bother! I'm too comfy to move."[Pg 37]

"Nice Wood-gatherer you'll look if you come

empty-handed!"

"I'd appropriate half your lot first, Lizzikins!"

"Would you, indeed? I'd denounce you, and

you'd lose your rank and be degraded to a candidate

again."

"Oh, you mean, stingy miser!"

"Not at all. It's the wise and foolish virgins

over again. I shan't have enough for myself and

you. I've a lovely little stack—just enough for

one—reposing—no, I'd better not tell you where.

Don't look so hopeful. You're not to be trusted."

"What are you talking about?" asked Rona

Mitchell, who had wandered up to the group.

"Why are some of you picking up sticks? I saw

a girl over there with quite a bundle just now.

You might tell me."

So far Rona had not been well received in her

own form, IV b. She was older than her class-mates,

and they, instead of attempting to initiate

her into the ways of the Woodlands girls on this

holiday afternoon, had scuttled off and left her to

fend for herself. She looked such an odd, wistful,

lonely figure that Lizzie Lonsdale's kind heart smote

her. She pushed the other girls farther along the

tree-trunk till they made a grudging space for the

new-comer.

"I'm a good hand at camp-fires, if you want

any help," continued Rona, seating herself with

alacrity. "I've made 'em by the dozen at home,

and cooked by them too. Just let me know where

you want it, and I'll set to work."[Pg 38]

"You wouldn't be allowed," said Beth bluntly.

"This fire is a very special thing. Only Wood-gatherers

may bring the fuel. No one else is

eligible."

"Why on earth not?"

"Oh, I can't bother to explain now! It would

take too long. You'll find out to-night. Girls,

I'm going in!"

"Turn up here at dusk if you want to know, and

bring a cup with you," suggested Lizzie, with a

half-ashamed effort at friendliness, as she followed

her chums.

"You bet I'll turn up! Rather!"

That evening, just after sunset, little groups of

girls began to collect round an open green space

in the glade. They came quietly and with a certain

sense of discipline. A stranger would have noticed

that if any loud tone or undue hilarity made itself

heard, it was instantly and firmly repressed by one

or two who seemed in authority. That the meeting

was more in the nature of a convention than a

mere pleasure-gathering was evident both from

the demeanour of the assemblage and from the

various badges pinned on the girls' coats. No

teacher was present, but there was an air of general

expectancy, as if the coming of somebody were

awaited. To the pupils at The Woodlands this

night's ceremony was a very special occasion, for

it was the autumn reunion of the Camp-fire

League, an organization which, originally of

American birth, had been introduced at the instigation

of Miss Teddington, and had taken great[Pg 39]

root in the school. Any girl was eligible as a

candidate, but before she could gain admission to

even the initial rank she had to prove herself

worthy of the honour of membership, and pass

successfully through her novitiate.

The organizer and leader of the branch which

to-night was to celebrate its third anniversary was

a certain Mrs. Arnold, a charming young American

lady who lived in the neighbourhood. She

had been an enthusiastic supporter of the League

in Pennsylvania before her marriage, and was delighted

to pass on its traditions to British schoolgirls.

Her winsome personality made her a prime

favourite at The Woodlands, where her influence

was stronger even than she imagined. Miss Teddington,

though it was she who had asked Mrs.

Arnold to institute and take charge of the meetings,

had the discretion to keep out of the League herself,

realizing that the presence of teachers might

be a restraint, and that the management was better

left in the hands of a trustworthy outsider.

To become an authorized Camp-fire member was

an ambition with most of the girls, and spurred

many on to greater efforts than they would otherwise

have attempted. All looked forward to the

meetings, and there could be no greater punishment

for certain offences than a temporary withdrawal

of League privileges.

This September, after the long summer holiday,

the reunion seemed of even more than ordinary

importance.

The sun had set, the last gleam of the afterglow[Pg 40]

had faded, and the glade had grown full of dim

shadows by the time everybody was present in

the grove. The gentle rustle of the leafy boughs

overhead, and the persistent tumbling rush of the

stream, seemed like a faint orchestral accompaniment

of Nature for the ceremonial.

"Is it a Quakers' Meeting or a Freemasons'

Lodge? You're all very mum," asked Rona, whom

curiosity had led out with the others.

"Sh-sh! We're waiting for our 'Guardian of

the Fire'," returned Ulyth, trying to suppress the

loudness of the high-pitched voice. "Mrs. Arnold's

generally very punctual. Oh, there! I believe I

hear her ringing her bicycle bell now. I'm going

down the field to meet her."

Ulyth regarded Mrs. Arnold with that intense

adoration which a girl of fifteen often bestows on

a woman older than herself. She ran now through

the wood, hoping she might be in time to catch

her idol on the drive and have just a few precious

moments with her before she was joined by the

others. There were many things she wanted to

pour into her friend's ready ears, but she knew it

would be impossible to monopolize her as soon as

the rest of the girls knew of her arrival. She fled

as on wings, therefore, and had the supreme satisfaction

of being the first in the field. Mrs. Arnold,

young, very fair, graceful, and golden-haired,

looked a picture in her blue cycling costume as

she leaned her machine against a tree and greeted

her enthusiastic admirer.

"Oh, you darling! I've such heaps to tell you!"[Pg 41]

began Ulyth, clasping her tightly by the arm.

"Rona Mitchell has come, and she's the most

awful creature! I never was so disappointed in

my life. Don't you sympathize with me, when I

expected her to be so ripping? She's absolute

backwoods!"

"Yes, I've heard all about her. Poor child!

She must have had a strange training. It's time

indeed she began to learn something."

"She's not learned anything in New Zealand.

Oh, her voice will just grate on you! And her

manners! She's hopeless! Everything she does

and says is wrong. And to think she's been

foisted on to me, of all people!"

"Poor child!" repeated Mrs. Arnold. ("Which

of us does she mean?" thought Ulyth.) "She's

evidently raw material. Every diamond needs

polishing. What an opportunity for a Torch-bearer!"

Ulyth dropped her friend's arm suddenly. It

was not at all the answer she had expected. Moreover,

at least a dozen girls had come running up

and were claiming their chief's attention. In a

species of triumphant procession Mrs. Arnold was

escorted into the glade and installed on her throne

of state, a seat made of logs and decorated with

ferns. Everyone clustered round to welcome her,

and for the moment she was the centre of an enthusiastic

crowd. Ulyth followed more slowly. She

was feeling disturbed and put out. What did Mrs.

Arnold mean? Surely not——? A sudden thought

had flashed into her mind but she thrust it away[Pg 42]

indignantly. Oh no, that was quite impossible!

It was outrageous of anybody to make the suggestion.

And yet—and yet—the uneasy voice that

had been haunting her for the last four days began

to speak with even more vehemence. With a sigh

of relief she heard the signal given for "Attention",

and cast the matter away from her for the

moment. Every eye was fixed on their leader.

The ceremony was about to begin.

Mrs. Arnold rose, and in her clear, sweet voice

proclaimed:

"The Guardian of the Fire calls on the Wood-gatherers

to bring their fuel."

At once a dozen girls came forward, each dragging

a tolerably large bundle of brushwood. They

deposited these in a circle, saluted, and retired.

"Fire-makers, do your work!" commanded the

leader.

Eight girls responded, Ulyth among the number,

and seizing the brushwood, they built it deftly into

a pile. All stood round, waiting in silence while

their chief struck a match and applied a light to

some dried leaves and bracken that had been placed

beneath. The flame rose up like a scarlet ribbon,

and in a few moments the dry fuel was ablaze and

crackling. The gleam lighting up the glade displayed

a picturesque scene. The boles of the trees

might have been the pillars in some ancient temple,

with the branches for roof. Close by the cascade

of the stream leapt white against a background of

dim darkness. The harvest moon, full and golden,

was rising behind the crest of Cwm Dinas. An owl[Pg 43]

flew hooting from the wood higher up the glen.

Mrs. Arnold stood waiting until the bonfire was

well alight, then she turned to the expectant girls.

"I've no need to tell most of you why we have

met here to-night; but for the benefit of a few who

are new-comers to The Woodlands I should like

briefly to explain the objects of the Camp-fire

League. The purpose of the organization is to

show that the common things of daily life are the

chief means of beauty, romance, and adventure, to

cultivate the outdoor habit, and to help girls to

serve the community—the larger home—as well as

the individual home. In these ultra-modern times

we must especially devote ourselves to the service

of the country, and try by every means in our

power to make our League of some national use.

First let us repeat together the rules of the Camp-fire

League:

"'1. Seek beauty.

2. Give service.

3. Pursue knowledge.

4. Be trustworthy.

5. Hold on to health.

6. Glorify work.

7. Be happy.'

"Seeking beauty includes more than looking for

superficial adornment. Beauty is in all life, in

Nature, in people, in the love of one's heart, in

virtue and a radiant disposition. The value of

service depends largely upon the attitude of mind

of the one rendering it. Joy in the performance of

some needed service in behalf of parent, teacher,[Pg 44]

friend, or country constitutes a part of the very

essence of goodness, and multiplies the good

already abiding in the heart. This is the third

anniversary of the founding of a branch of the

League at The Woodlands. So far the work has

been very encouraging, and I am glad to say that

to-night we have candidates eligible for all three

ranks. It shall now be the business of the meeting

formally to admit them. Candidates for Wood-gatherers,

present yourselves!"

Six of the younger girls came forward and

saluted.

"Can you repeat, and will you promise to obey,

the seven rules of the Camp-fire law?"

Each responded audibly in the affirmative.

"Then you are admitted to the initial rank of

Wood-gatherers, you are awarded the white badge

of service, and may sign your names as accepted

members of the League."

The six retired to make way for a higher grade,

and eight other girls stepped into the firelight.

"Candidates for Fire-makers, you have passed

three months with good characters as Wood-gatherers,

and you have proved your ability to

render first aid, keep accounts, tie knots, and prepare

and serve a simple meal; you have each committed

to memory some good poem, and have

acquainted yourself with the career of some able,

public-spirited woman. Having thus shown your

wish to serve the community, repeat the Fire-maker's

desire."

And all together the eight girls chanted:[Pg 45]

"As fuel is brought to the fire

So I purpose to bring

My strength,

My ambition,

My heart's desire,

My joy,

And my sorrow

To the fire

Of human kind.

For I will tend

As my fathers have tended

And my fathers' fathers

Since time began,

The fire that is called

The love of man for man,

The love of man for God."

Mrs. Arnold said a few kind words to each as

she pinned on their red badges. Only novices

who had stood the various tests with credit were

raised to the honour of the second rank. Those

who had failed must perforce continue as Wood-gatherers

for another period of three months.

There remained one further and higher rank,

only attainable after six months' ardent and trustworthy

service as Fire-makers. To-night three

girls were to be admitted to its privileges, and

Helen Cooper, Doris Deane, and Ulyth Stanton

presented themselves. With grave faces they repeated

the Torch-bearer's desire:

"That light which has been given to me I desire to pass

undimmed to others."

Ulyth kissed Mrs. Arnold's pretty hand as the

long-coveted yellow badge was fastened on to her

dress, side by side with the Union Jack. She[Pg 46]

was so glad to be a Torch-bearer at last. She had

become a candidate when the League was first

founded three years ago, and all that time she had

been slowly working towards the desired end of

the third rank. One or two slips had hindered

her progress, but last term she had made a very

special effort, and it was sweet to meet with her

reward. Torch-bearers were mostly to be found

among the Sixth and Upper Fifth; she was the

only girl in V b who had won so high a place.

She touched the yellow ribbon tenderly. It meant

so much to her.

Now that the serious business of the meeting

was over, the fun was about to begin. The big

camp-kettle was produced and filled at the stream,

and then set to boil upon the embers. Cups and

spoons made their appearance. Cocoa and biscuits

were to be the order of the evening, followed by as

many songs, dances, and games as time permitted.

Squatting on the grass, the girls made a circle

round their council-fire. Marjorie Earnshaw, one

of the Sixth, had brought her guitar, and struck

the strings every now and then as an earnest of

the music she intended to bring from it later on.

Everybody was in a jolly mood, and inclined to

laugh at any pun, however feeble. Mrs. Arnold,

always bright and animated, surpassed herself,

and waxed so amusing that the circle grew almost

hysterical. The Wood-gatherers, whose office it

was to mix the cocoa, supplied cup after cup, and

refilled the kettle so often that they ventured to

air the time-honoured joke that the stream would[Pg 47]

run dry, for which ancient chestnut they were

pelted with pebbles.

When at last nobody could even pretend to be

thirsty any longer, the cups were rinsed in the

pool and stacked under a tree, and the concert

commenced. Part-songs and catches sounded delightful

in the open air, and solos, sung to the

accompaniment of Marjorie's guitar, were equally

effective. The girls roared the choruses to popular

national ditties, and special favourites were repeated

again and again. Several step-dances were executed,

and had a weird effect in the unsteady light

of the waning fire. Mrs. Arnold, who was a splendid

elocutionist, gave a recitation on an incident

in the American War, and was enthusiastically

encored. The moon had risen high in the sky,

and was peeping through the tree-tops as if curious

to see who had invaded so sylvan a spot as the

glade. The silver beams caught the ripples of

the stream and made the shadows seem all the

darker.

It was a glorious beginning for the new term, as

everybody agreed, and an earnest of the fun that

was in store later on.

"We shan't be able to camp out next meeting,

but we'll have high jinks in the hall," purred Beth

Broadway.

"Yes; Mrs. Arnold says she has a lovely programme

for the winter, and we're to have candles

instead of fuel," agreed Lizzie Lonsdale, who

had been raised that evening to the rank of Fire-maker.[Pg 48]

"Trust Mrs. Arnold to find something new for

us to do!" murmured Ulyth, looking fondly in the

direction of her ideal.

"My gracious, I call this meeting no end!"

piped a cheerful voice in her ear; and Rona,

smiling with all-too-obtrusive friendliness, plumped

down by her side. "You've good times here, and

no mistake! I think I'll be a candidate myself

next, if that's the game to play. You're a high-and-mighty

one, aren't you? Let's have a look at

your badge!"

"If you dare to touch it!" flared Ulyth, putting

up her hand to guard her cherished token.

"Why, I wouldn't do it any harm, I promise

you; I wouldn't finger it! It means something,

doesn't it? I didn't quite catch what it was. You

might tell me. How'm I ever to get to know if you

won't?"

Rona's clear blue eyes, unconsciously wistful,

looked straight into Ulyth's. The latter sprang

to her feet without a word. The force of her own

motto seemed suddenly to be revealed to her. She

rushed away into the shadow of the trees to think

it over for herself.

"That light which has been given to me I desire to pass

undimmed to others."

Those were the words she had repeated so

earnestly less than an hour ago. And she was

already about to make them a mockery! Yes, that

was what Mrs. Arnold had meant. She had known

it all the time, but she would not acknowledge it[Pg 49]

even to her innermost heart. Was this what was

required from a Torch-bearer—to pass on her own

refinement and culture to a girl whose crudities

offended every particle of her fastidious taste?

Ulyth sat down on a stone and wept hot, bitter,

rebellious tears. She understood only too well

why she had been so miserable for the last three

days. She had disliked Miss Bowes for hinting

that she was not keeping her word, and had told

herself that she was a much-tried and ill-used

person.

"I must do it, I must, or fail at the very

beginning!" she sobbed. "I know what Mother

would say. It's got to be; if for nothing else, for

the sake of the school. A Torch-bearer mustn't

shirk and break her pledge. Oh, how I shall loathe

it, hate it! Ulyth Stanton, do you realize what

you're undertaking? Your whole term's going to

be spoilt."

The big bell in the tower was clanging its summons

to return, with short, impatient strokes.

Everybody joined hands in a circle round the

ashes of the camp-fire, to sing in a low chant

the good-night song of the League and "God

Save the Queen". Mr. Arnold, who had come to

fetch his wife, was sounding his hooter as a signal

on the drive. The evening's fun was over. Regretfully

the girls collected cups, spoons, and kettle,

and made their way back to the house.

On Sunday morning Ulyth, with a very red face,

marched into the study, and announced:

"Miss Bowes, I've been having a tussle. One-[Pg 50]half

of me said: 'Don't have Rona in your room

at any price!' and the other half said: 'Let her

stop!' I've decided to keep her."

"I knew you would, when you'd thought it

over," beamed Miss Bowes.

"Are all New Zealanders the same?" asked

Ulyth. "I've not met one before."

"Certainly not. Most of them are quite as

cultured and up-to-date as ourselves. There are

splendid schools in New Zealand, and excellent

opportunities for study of every kind. Poor Rona,

unfortunately, has had to live on a farm far away

from civilization, and her education and welfare in

every respect seem to have been utterly neglected.

Don't take her as a type of New Zealand! But

she'll soon improve if we're all prepared to help

her. I'm glad you're ready to be her real friend."

"I'll try my best!" sighed Ulyth.

[Pg 51]

CHAPTER IV

A Blackberry Foray

Having made up her mind to accept the responsibility

which fate, through the agency of the

magazine editor, had thrust upon her, Ulyth,

metaphorically speaking, set her teeth, and began

to take Rona seriously in hand. Being ten months

older than her protégée, in a higher form, and,

moreover, armed with full authority from Miss

Bowes, she assumed command of the bedroom,

and tried to regulate the chaos that reigned on

her comrade's side of it. Rona submitted with

an air of amused good nature to have her clothes

arranged in order in her drawers, her shoes put

away in the cupboard, and her toilet articles allotted

places on her washstand and dressing-table. She

even consented to give some thought to her personal

appearance, and borrowed Ulyth's new

manicure set.

"You're mighty particular," she objected.

"What does it all matter? Miss Bowes gave me

such a talking-to, and said I'd got to do exactly

what you told me; and before I came, Dad rubbed

it into me to copy you for all I was worth, so I[Pg 52]

suppose I'll have to try. I guess you'll find it a

job to civilize me though." And her eyes twinkled.

Ulyth thought, with a mental sigh, that she probably

would find it "a job".

"No one bothered about it at home," Rona continued

cheerfully. "Dad did say sometimes I was

growing up a savage, but Mrs. Barker never cared.

She let me do what I liked, so long as I didn't

trouble her. She was no lady! We couldn't get

a lady to stay at our out-of-the-way block. Dad

used to be a swell in England once, but that was

before I was born."

Ulyth began to understand, and her disgust

changed to a profound pity. A motherless girl

who had run wild in the backwoods, her father

probably out all day, her only female guide a

woman of the backwoods, whose manners were

presumably of the roughest—this had been Rona's

training. No wonder she lacked polish!

"When I compare her home with my home and

my lovely mother," thought Ulyth, "yes—there's

certainly a vast amount to be passed on."

The other girls, who had never expected her to

keep Rona in her bedroom, were inclined to poke

fun at the proceeding.

"Your bear cub will need training before you

teach her to dance," said Stephanie Radford tauntingly.

"She has no parlour tricks at present," sniggered

Addie Knighton.

"Are you posing as Valentine and Orson?"

laughed Gertie Oliver. Gertrude had been Ulyth's[Pg 53]

room-mate last term, and felt aggrieved to be

superseded.

"I call her the cuckoo," said Mary Acton. "Do

you remember the young one we found last spring,

sprawling all over the nest, and opening its huge,

gaping beak?"

In spite of her ignorance and angularities there

was a certain charm about the new-comer. When

the sunburn caused by her sea-voyage had yielded

to a course of treatment, it left her with a complexion

which put even that of Stephanie Radford,

the acknowledged school beauty, in the shade.

The coral tinge in Rona's cheeks was, as Doris

Deane enviously remarked, "almost too good to

look natural", and her blue eyes with the big

pupils and the little dark rims round the iris shone

like twinkling stars when she laughed. That

ninnying laugh, to be sure, was still somewhat

offensive, but she was trying to moderate it, and

only when she forgot did it break out to scandalize

the refined atmosphere of The Woodlands; the

small white even teeth which it displayed, and two

conspicuous dimples, almost atoned for it. The

brown hair was brushed and waved and its consequent

state of new glossiness was a very distinct

improvement on the former elf locks. In the sunshine

it took tones of warm burnt sienna, like the

hair of the Madonna in certain of Titian's great pictures.

Lessons, alack! were uphill work. Rona was

naturally bright, but some subjects she had never

touched before, and in others she was hopelessly

backward. The general feeling in the school was[Pg 54]

that "The Cuckoo", as they nicknamed her, was

an experiment, and no one could guess exactly

what she would grow into.

"She's like one of those queer beasties we dug

up under the yew-tree last autumn," suggested

Merle Denham. "Those wriggling transparent

things, I mean. Don't you remember? We kept

them in a box, and didn't know whether they'd

turn out moths, or butterflies, or earwigs, or woodlice!"

"They turned into cockchafer beetles, as a matter

of fact," said Ulyth drily.

"Well, they were horrid enough in all conscience.

I don't like Nature study when it means

hoarding up creepy-crawlies."

"You're not obliged to take it."

"I don't this year. I've got Harmony down on

my time-table instead."

"You'll miss the rambles with Teddie."

"I don't care. I'll play basket-ball instead."

"How about the blackberry foray?"

"Oh, I'm not going to be left out of that! It's

not specially Nature study. I've put my name

down with Miss Moseley's party."

The inmates of The Woodlands were fond of jam.

It was supplied to them liberally, and they consumed

large quantities of it at tea-time. To help to

meet this demand, blackberrying expeditions were

organized during the last weeks of September, and

the whole school turned out in relays to pick fruit.

A dozen girls and a mistress generally composed

a party, which was not confined to any particular[Pg 55]

form, but might include any whose arrangements

for practising or special lessons allowed them to

go. Dates and particulars of the various rambles

planned, with the names of the mistresses who were

to be leaders, were pinned up on the notice-board,

and the girls might put their names to them as they

liked, so long as each list did not exceed twelve.

On Saturday afternoon Miss Moseley headed a

foray in the direction of Porth Powys Falls, and

Merle, Ulyth, Rona, Addie, and Stephanie were

members of her flock.

"I'm glad I managed to get into this party,"

announced Merle, "because I always like Porth

Powys better than Pontvoelas or Aberceiriog. It's

a jollier walk, and the blackberries are bigger and

better. I was the very last on the list, so I'd luck.

Alice had to go under Teddie's wing. I'd rather

have Mosie than Teddie!"

"So would I," agreed Ulyth. "I scribbled my

name the very first of all. Just got a chance to do

it as I was going to my music-lesson, before everyone

else made a rush for the board. Porth Powys

will be looking no end to-day."

Swinging their baskets, the girls began to climb

a narrow path which ran alongside the stream up

the glen. Some of them were tempted to linger,

and began to gather what blackberries could be

found; but Miss Moseley had different plans.

"Come along! It's ridiculous to waste our labour

here," she exclaimed. "All these bushes have

been well picked over already. We'll walk straight

on till we come to the lane near the ruined cottage,[Pg 56]

then we shall get a harvest and fill our baskets in

a third of the time. Quick march!"

There was sense in her remarks, so Merle

abandoned several half-ripe specimens for which

she had been reaching and joined the file that was

winding, Indian fashion, up the path through the

wood. Over a high, ladder-like stile they climbed,

then dropped down into the gorge to where a small

wooden bridge spanned the stream. They loved to

stand here looking at the brown rushing water that

swirled below. The thick trees made a green parlour,

and the continual moisture had carpeted the

woods with beautiful verdant moss which grew in

close sheets over the rocks. Up again, by an even

steeper and craggier track, they climbed the farther

bank of the gorge, and came out at last on to the

broad hill-side that overlooked the Craigwen Valley.

Here was scope for a leader; the track was so

overgrown as to be almost indistinguishable, and

ran across boggy land, where it was only too easy

to plunge over one's boot-tops in oozy peat. Miss

Moseley found the way like a pioneer; she had often

been there before and remembered just what places

were treacherous and just where it was possible to

use a swinging bough for a help. By following in

her footsteps the party got safely over without serious

wettings, and sat down to take breath for a few

minutes on some smooth, glacier-ground rocks that

topped the ridge they had been scaling. They were

now at some height above the valley, and the prospect

was magnificent. For at least ten miles they

could trace the windings of the river, and taller[Pg 57]

and more distant mountain peaks had come into

view.

"Some people say that Craigwen Valley's very

like the Rhine," volunteered Ulyth. "It hasn't

any castles, of course, except at Llangarmon, but

the scenery's just as lovely."

"Nice to think it's British then," rejoiced Merle.

"Wales can hold its own in the way of mountains

and lakes. People have no need to go abroad for

them. What's New Zealand like, Rona?"

"We've ripping rivers there," replied the Cuckoo,

"bigger than this by lots, and with tree-ferns up in

the bush. This isn't bad, though, as far as it goes.

What's that place over across on the opposite

hill?"

"Where the light's shining? Oh, that's Llanfairgwyn!

There's a village and a church. We've

only been once. It's rather a long way, because

you have to cross the ferry at Glanafon before you

can get to the other side of the river."

"And what's that big white house in the trees,

with the flag?"

"That's Plas Cafn. It's the place in the neighbourhood,

you know," said Stephanie, fondly fingering

her necklace.

"I don't know. How should I?"

"Well, you know it now, at any rate."

"Does it belong to toffs?"

"It belongs to Lord and Lady Glyncraig. They

live there for part of the year."

"Oh!" said Rona. She put her chin on her

hand and surveyed the distant mansion for several[Pg 58]

moments in silence. "I reckon they're stuck up,"

she remarked at last.

"I believe they're considered nice. I've never

spoken to them," replied Ulyth.

"I have," put in Stephanie complacently. "I

went to tea once at Plas Cafn. It was when Father

was Member for Rotherford. Lord Glyncraig knew

him in Parliament, of course, and he happened to

meet Father and me just when we were walking

past the gate at Plas Cafn, and asked us in to tea."

Merle, Addie, and Ulyth smiled. This visit,

paid four years ago, was the standing triumph of

Stephanie's life. She never forgot, nor allowed any

of her schoolfellows to forget, that she had been

entertained by the great people of the neighbourhood.

"He wasn't Lord Glyncraig then; he was only

Sir John Mitchell, Baronet. He's been raised to

a peerage since," said Merle, willing to qualify

some of the glory of Stephanie's reminiscences.

"We don't grow peers in Waitoto, or baronets

either, for the matter of that," observed Rona. "I

don't guess they're wanted out with us. We'd

have no place in the bush for a Lord Glyncraig."

"You'd better claim acquaintance with him, as

your name's Mitchell too. How proud he'd be of

the honour!" teased Addie.

Coral flooded the whole of the Cuckoo's face.

She had begun to understand the difference between

her rough upbringing and the refined homes of the

other girls, and she resented the sneers that were

often made at her expense.[Pg 59]

"Our butcher at home is Joseph Mitchell,"

hinnied Merle.

"Mitchell's a common enough name," said Ulyth.

"I know two families in Scotland and some people

at Plymouth all called Mitchell. They're none of

them related to each other, and probably not to

Merle's butcher or to Lord Glyncraig."

"Nor to me," said Rona. "I'm a democrat, and

I glory in it. Stephanie's welcome to her grand

friends if she likes them."

"I do like them," sighed Stephanie plaintively.

"I love aristocratic people and nice houses and

things. Why shouldn't I? You needn't grin,

Addie Knighton; you'd know them yourself if you

could. When I come out I'd like to be presented

at Court, and go to a ball where the people are all

dukes and duchesses and earls and countesses. It

would be worth while dancing with a duke, especially

if he wore the Order of the Garter!"

"Until that glorious day comes you'll have to

dance with poor little me for a partner," giggled

Merle.

"Aren't you all rested? We shall get no blackberries

if we don't hurry on," called Miss Moseley

from the other end of the rock.

Everybody scrambled up immediately and set out

again over the bracken-covered hill-side. Another

half-mile and they had reached the bourne of their

expedition. The narrow track through the gorse

and fern widened suddenly into a lane, a lane with

very high, unmortared walls, over which grew a

variety of bramble with a particularly luscious fruit.[Pg 60]

Every connoisseur of blackberries knows what a

difference there is between the little hard seedy ones

that commonly flourish in the hedges and the big

juicy ones with the larger leaves. Nature had been

prodigal here, and a bounteous harvest hung within

easy reach.

"They are as big as mulberries—and oh, such

heaps and heaps!" exclaimed Addie ecstatically.

"No, Merle, you wretch, this is my branch! Don't

poach, you wretch! Go farther on, can't you!"

"I wish we could send the jam to the hospital

when it's made," sighed Merle.

The party spread itself out; some of the girls

climbed to the top of the wall, so that they could

reach what grew on the sunnier side, and a few

skirted round over a gate into a field, where a

ruined cottage was also covered with brambles.

They worked down the lane by slow degrees, picking

hard as they went. At the end a sudden rushing

roar struck upon the ear, and without even

waiting for a signal from Miss Moseley the girls

with one accord hopped over a fence, and ran up a

slight incline. The voice of the waterfall was calling,

and the impulse to obey was irresistible. At