Writing the Notes.

Writing the Notes.

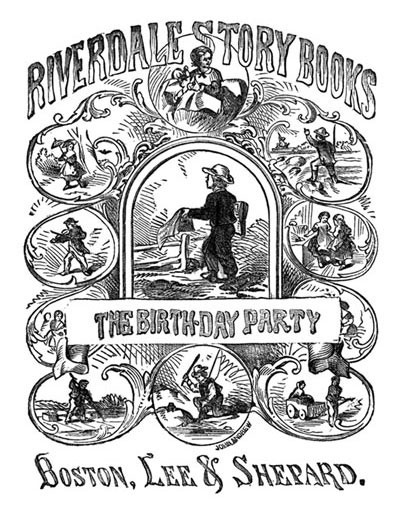

The Riverdale Books.

THE BIRTHDAY PARTY.

A STORY FOR LITTLE FOLKS.

BY

OLIVER OPTIC,

author of “the boat club,” “all aboard,” “now or never,” “try

again,” “poor and proud,” “little by little,” &c.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD,

(successors to phillips, sampson & co.)

1864.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1862, by

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

electrotyped at the

boston stereotype foundry.

[Pg 7]

THE BIRTHDAY PARTY.

I.

Flora Lee’s birthday came

in July. Her mother wished

very much to celebrate the

occasion in a proper manner.

Flora was a good girl, and her

parents were always glad to

do any thing they could to

please her, and to increase her[Pg 8]

happiness.

They were very indulgent

parents, and as they had plenty

of money, they could afford

to pay well for a “good time.”

Yet they were not weak and

silly in their indulgence. As

much as they loved their little

daughter, they did not give

her pies and cakes to eat

when they thought such articles

would hurt her.

They did not let her lie in[Pg 9]

bed till noon because they

loved her, or permit her to

do any thing that would injure

her, either in body or

mind. Flora always went to

church, and to the Sunday

school, and never cried to stay

at home. If she had cried, it

would have made no difference,

for her father and mother

meant to have her do right,

whether she liked it or not.

But Flora gave them very[Pg 10]

little trouble about such matters.

Her parents knew best

what was good for her, and

she was willing in all things

to obey them. It was for this

reason that they were so anxious

to please her, even at the

expense of a great deal of

time and money.

The birthday of Flora came

on Wednesday, and school did

not keep in the afternoon. All

the children, therefore, could[Pg 11]

attend the party which they

intended to give in honor of

the day.

About a week before the

time, Mrs. Lee told Flora she

might have the party, and

wanted her to make out a list

of all the children whom she

wished to invite.

“I want to ask all the children

in Riverdale,” said Flora,

promptly.

“Not all, I think,” replied[Pg 12]

Mrs. Lee.

“Yes, mother, all of them.”

“But you know there are a

great many bad boys in town.

Do you wish to invite them?”

“Perhaps, if we treat them

well, they will be made better

by it.”

“Would you like to have

Joe Birch come to the party?”

“I don’t know, mother,” said

Flora, musing.

“I think you had better invite[Pg 13]

only those who will enjoy

the party, and who will not be

likely to spoil the pleasure of

others. We will not invite

such boys as Joe Birch.”

“Just as you think best,

dear mother,” replied Flora.

“Shall I ask such boys as

Tommy Woggs?”

“Tommy isn’t a bad boy,”

said Mrs. Lee, with a smile.

“I don’t know that he is;[Pg 14]

but he is a very queer fellow.

You said I had better not ask

those who would be likely to

spoil the pleasure of others.”

“Do you think, my child,

Tommy Woggs will do so?”

“I am afraid he would; he

is such a queer boy.”

“But Tommy is a great

traveller, you know,” added

Mrs. Lee, laughing.

“The boys and girls don’t

like him, he pretends to be[Pg 15]

such a big man. He knows

more than all the rest of the

world put together—at least,

he thinks he does.”

“I think you had better

ask him, for he will probably

feel slighted if you don’t.”

“Very well, mother.”

“Now, Flora, I will take a

pencil and paper and write

down the names of all the

boys and girls with whom

you are acquainted; and you[Pg 16]

must be careful not to forget

any. Here comes Frank; he

will help you.”

Frank was told about the

party, and he was quite as

much pleased with the idea

as his sister had been; and

both of them began to repeat

the names of all the boys and

girls they could remember.

For half an hour they were

employed in this manner, and

then the list was read over to[Pg 17]

them, so as to be sure that no

names had been omitted.

Flora and Frank now went

through all the streets of Riverdale,

in imagination, thinking

who lived in each house;

and when they had completed

their journey in fancy, they

felt sure they had omitted

none.

“But we must invite cousins

Sarah and Henry,” said Flora.

“O, I hope they will come![Pg 18]

Henry is so funny; we can’t

do without them.”

“Perhaps they will come;

at any rate we will send them

invitations,” replied Mrs. Lee.

The next day, when the

children had gone to school,

Mrs. Lee went to the office of

the Riverdale Gazette, which

was the village newspaper, and

had the invitations printed on

nice gilt-edged paper.

By the following day Mrs.[Pg 19]

Lee had written in the names

of the children invited, enclosed

the notes in envelopes, and directed

them. I will give you

a copy of one of them, that

you may know how to write

them when you have a birthday

party, though I dare say

it would do just as well if you

go to your friends and ask

them to attend. If you change

the names and dates, this note

will answer for any party.

Miss Flora Lee presents her compliments[Pg 20]

to Miss Nellie Green, and

requests the pleasure of her company on

Wednesday afternoon, July 20.

Riverdale, July 15.

“Those are very fine indeed,”

said Flora: “shall I put

on my bonnet, and carry out

some of them to-day?”

“No, my child; it is not

quite the thing for you to

carry your own invitations. I[Pg 21]

will tell you what you may do.

You may hire David White

to deliver them for you. You

must pay him for it; give him

half a dollar, which will be a

good thing for him.”

This plan was adopted, and

Frank was sent with the notes

and the money over to the

poor widow’s cottage.

“Don’t you think it is very

wicked, mother, for rich folks

to have parties, when the

money they cost will do so[Pg 22]

much good to the poor?”

asked Flora.

“I do not think so, my dear

child.”

“Well, I think so, mother,”

added Flora, warmly.

“Perhaps you do not fully

understand it.”

“I think I do.”

“Why should it be wicked

for you to enjoy yourself?”

“I don’t think it is wicked

to enjoy myself, but only to[Pg 23]

spend money for such things.

You said you were going to

have the Riverdale Band, and

that the music would cost

more than twenty dollars.”

“I did, and the supper will

cost at least twenty more;

for I have spoken to the confectioner

to supply us with ice

cream, cake, jellies, and other

luxuries. We shall have a

supply of strawberries and[Pg 24]

cream, and all the nice things

of the season. We must also

erect a tent in the garden, in

which we shall have the supper;

but after tea I will tell

you all about it.”

[Pg 25]

[Pg 26]

Flora and her Father.

Flora and her Father.[Pg 27]

II.

Flora could not help thinking

how much good the forty

dollars, which her father would

have to pay for the birthday

party, would do if given to

the poor.

It seemed to her just like

spending the money for a few

hours’ pleasure; and even if

they had a fine time, which she[Pg 28]

was quite sure they would

have, it would be soon over,

and not do any real good.

Forty dollars was a great

deal of money. It would pay

Mrs. White’s rent for a whole

year; it would clothe her family,

and feed them nearly all

the next winter. It appeared

to her like a shameful waste;

and these thoughts promised

to take away a great deal from

the pleasure of the occasion.

“I think, mother, I had just[Pg 29]

as lief not have the band, and

only have a supper of bread

and butter and seed cakes.”

“Why, Flora, what has got

into you?” said her father.

Mrs. Lee laughed at the

troubled looks of Flora, and

explained to her father the

nature of her scruples in regard

to the party.

“Where did the child get

this foolish idea?” asked her[Pg 30]

father, who thought her notions

were too old and too

severe for a little girl.

“Didn’t I see last winter

how much good only a little

money would do?” replied

Flora.

“Don’t you think it is wicked

for me to live in this great

house, keep five or six horses,

and nine or ten servants, when

I could live in a little house, like

Mrs. White?” laughed Mr. Lee.

“All the money you spend[Pg 31]

would take care of a dozen

families of poor folks,” said

Flora.

“That is very true. Suppose

I should turn away all

the men and women that work

for me,—those, I mean, who

work about the house and

garden,—and give the money

I spend in luxuries to the

poor.”

“But what would John and[Pg 32]

Peter, Hannah and Bridget do

then? They would lose their

places, and not be able to earn

any thing. Why, no, father;

Peter has a family; he has got

three children, and he must

take care of them.”

“Ah, you begin to see it—do

you?” said Mr. Lee, with

a smile. “All that I spend

upon luxury goes into the

pockets of the farmer, mechanic,

and laborer.”

“I see that, father,” replied[Pg 33]

Flora, looking as bright as

sunshine again; “but all the

money spent on my party will

be wasted—won’t it?”

“Not a cent of it; my child.

If I were a miser, and kept

my money in an iron safe,

and lived like a poor man, I

should waste it then.”

“But twenty dollars for the

Riverdale Band is a great deal

to give for a few hours’ service.[Pg 34]

It don’t do any good,

I think.”

“Yes, it does; music improves

our minds and hearts.

It makes us happy. I have

engaged six men to play.

They are musicians only at

such times as they can get a

job. They are shoemakers,

also, and poor men; and the

money which I shall pay them

will help support their families

and educate them.”

“What a fool I was, father!”[Pg 35]

exclaimed Flora.

“O, no; not so bad as that;

for a great many older and

wiser persons than yourself

have thought just what you

think.”

“But the supper, father,—the

ice cream, the cake, and

the lemonade,—won’t all the

money spent for these things

be wasted?”

“No more than the money[Pg 36]

spent for the music. The confectioner

and those whom he

employs depend upon their

work for the means of supporting

themselves and their

families.”

“So they do, father. And

when you have a party, you

are really doing good to the

poor.”

“That depends upon circumstances,”

replied Mr. Lee.

“I don’t think it would be[Pg 37]

an act of charity for a person

who could not afford it to give

a party. I only mean to say

that when we spend money

for that which does not injure

us or any body else, what we

spend goes into the pockets

of those who need it.

“A party—a proper party,

I mean, such a one as you will

have—is a good thing in itself.

Innocent amusement is just as

necessary as food and drink.

“God has given me wealth,[Pg 38]

Flora, and he expects me to

do all the good I can with it.

I hold it as his steward. Now,

when I pay one of these musicians

three or four dollars

for an afternoon’s work, I do

him a favor as well as you

and those whom you invite to

your party.

“And I hope the party

will make you love one another

more than ever before.[Pg 39]

I hope the music will warm

your hearts, and that the supper

will make you happy, and

render you thankful to the

Giver of all things for his constant

bounty.”

“How funny that I should

make such a blunder!” exclaimed

Flora. “I am sure

I shall enjoy my party a great

deal more now that I understand

these things.”

“I hope you won’t understand[Pg 40]

too much, Flora. Suppose

you had only a dollar,

and that it had been given

you to purchase a story book.

Then, suppose Mrs. White and

her children were suffering

from want of fuel and clothing.

What would you do with

your dollar?”

“I would——”

“Wait a minute, Flora,”

interposed her father. “When

you buy the book, you pay[Pg 41]

the printer, the paper maker,

the bookseller, the type founder,

the miner who dug the

lead and the iron from the

earth, the machinist who made

the press, and a great many

other persons whose labor enters

into the making of a book—you

pay all these men for

their labor; you give them

money to help take care of

their wives and children, their

fathers and mothers. You

help all these men when you[Pg 42]

buy a book. Now, what would

you do with your dollar?”

“I would give it to poor

Mrs. White,” promptly replied

Flora.

“I think you would do

right, for your money would

do more good in her hands.

The self-denial on your part

would do you good. I only

wanted you to understand that,

when you bought a book,—even

a book which was only[Pg 43]

to amuse you,—the money is

not thrown away.

“Riches are given to men

for a good purpose; and they

ought to use their wealth for

the benefit of others, as well

as for their own pleasure. If

they spend money, even for

things that are of no real use

to them, it helps the poor, for

it feeds and clothes them.”

Flora was much interested[Pg 44]

in this conversation, and perhaps

some of my young friends

will think she was an old head

to care for such things; but I

think they can all understand

what was said as well as she

did.

[Pg 45]

[Pg 46]

On the Lawn.

On the Lawn.[Pg 47]

III.

The great day at length

arrived, and every thing was

ready for the party. On the

lawn, by the side of the house,

a large tent had been put up,

in which the children were to

have the feast.

Under a large maple tree,

near the tent, a stage for the

musicians had been erected.

Two swings had been put up;[Pg 48]

and there was no good reason

why the children should

not enjoy themselves to their

hearts’ content.

I think the teachers in the

Riverdale school found it hard

work to secure the attention

of their scholars on the forenoon

of that day, for all the

boys and girls in the neighborhood

were thinking about

the party.

As early as one o’clock in[Pg 49]

the afternoon the children began

to collect at the house

of Mr. Lee, and at the end

of an hour all who had received

invitations were present.

The band had arrived,

and at a signal from Mr. Lee

the music commenced.

“Now, father, we are all

here. What shall we do?”

asked Flora, who was so excited

she did not know which[Pg 50]

way to turn, or how to proceed

to entertain the party.

“Wait a few minutes, and

let the children listen to the

music. They seem to enjoy it

very well.”

“But we want to play something,

father.”

“Very soon, my child, we

will play something.”

“What shall we play, father?”

“There are plenty of plays.[Pg 51]

Wouldn’t you like to march

a little while to the music?”

“March?”

“Yes, march to the tune of

‘Hail, Columbia.’ I will show

you how to do it.”

“I don’t know what you

mean, father.”

“Well, I will show you in a

few minutes.”

When the band had played

a little while longer, Mr. Lee

assembled the children in the[Pg 52]

middle of the lawn, and asked

them if they would like to

march.

They were pleased with the

idea, though some of them

thought it would be rather

tame amusement for such an

exciting occasion.

“You want two leaders, and

I think you had better choose

them yourselves. It would

be the most proper to select

two boys.”

Mr. Lee thought the choice[Pg 53]

of the leaders would amuse

them; so he proposed that

they should vote for them.

“How shall we vote, father?”

asked Frank.

“Three of the children must

retire, and pick out four persons;

and the two of these

four who get the most votes

shall be the leaders.”

Mr. Lee appointed two girls

and one boy to be on this[Pg 54]

committee; but while he was

doing so, Tommy Woggs said

he did not think this was a

good play.

“I don’t think they will

choose the best leaders,” said

Tommy.

“Don’t you, Mr. Woggs?”

asked Mr. Lee, laughing.

“No, sir, I do not. What

do any of these boys know

about such things!” said Tommy,

with a sneer. “I have[Pg 55]

been to New York, and have

seen a great many parades.”

“Have you, indeed?”

“Yes, sir, I have.”

“And you think you would

make a better leader than any

of the others?”

“I think so, sir.”

All the children laughed

heartily at Master Woggs,

who was so very modest!

“None of these boys and

girls have ever been to New

York,”[Pg 56] added Tommy, his vanity

increasing every moment.

“That is very true; and perhaps

the children will select

you as their leader.”

“They can do as they like.

If they want me, I should be

very willing to be their leader,”

replied Tommy.

It was very clear that Master

Woggs had a very good

opinion of himself. He seemed

to think that the fact of his[Pg 57]

having been to New York

made a hero of him, and that

all the boys ought to take off

their caps to him.

But it is quite as certain

that the Riverdale children

did not think Master Woggs

was a very great man. He

thought so much of himself,

that there was no room for

others to think much of him.

The committee of three returned

in a few minutes, and[Pg 58]

reported the names of four

boys to be voted for as the

leaders. They were Henry

Vernon, Charley Green, David

White, and Tommy Woggs.

The important little gentleman

who had been to New

York, was delighted with the

action of the committee. He

thought all the children could

see what a very fine leader he

would make, and that all of

them would vote for him.

“What shall we do for votes,[Pg 59]

father?” asked Frank.

“We can easily manage that,

Frank,” replied Mr. Lee.

“We have no paper here.”

“Listen to me a moment,

children,” continued Mr. Lee.

“There are four boys to be

voted for; and we will choose

one leader first, and then the

other.

“Those who want Henry

Vernon for a leader will put[Pg 60]

a blade of grass in the hat

which will be the ballot box;

those who want Charley Green

will put in a clover blossom;

those who want David White

will put in a maple leaf; and

those who want to vote for

Tommy Woggs will put in a—let

me see—put in a dandelion

flower.”

The children laughed, for

they thought the dandelion

was just the thing for Master[Pg 61]

Woggs, who had been to New

York.

One of the boys carried

round Mr. Lee’s hat, and it

was found that Henry Vernon

had the most votes; so he was

declared to be the first leader.

“Humph!” said Tommy

Woggs. “What does Henry

Vernon know? He has never

been to New York.”

“But he lives in Boston,”

added Charley Green.

“Boston is nothing side of[Pg 62]

New York.”

“I think Boston is a great

place,” replied Charley.

“That’s because you have

never been to New York,”

said Master Woggs. “They

will, of course, all vote for me

next time. If they do, I will

show them how things are

done in New York.”

“Pooh!” exclaimed Charley,

as he left the vain little man.

While all the children were[Pg 63]

wondering who would be the

other leader, Flora was electioneering

among them for her

favorite candidate; that is, she

was asking her friends to vote

for the one she wanted. Who

do you suppose it was? Master

Woggs? No. It was David

White.

The hat was passed round

again, and when the votes

were counted, there was only[Pg 64]

one single dandelion blossom

found in the hat.

Tommy Woggs was mad,

for he felt that his companions

had slighted him; but it was

only because he was so vain

and silly. People do not often

think much of those who think

a great deal of themselves.

There was a great demand

for maple leaves, and David

White was chosen the second

leader, and had nearly all the[Pg 65]

votes. The boys then gave

three cheers for the leaders,

and the lines were formed.

Mr. Lee told Henry and David

just how they were to

march, and the band at once

began to play “Hail Columbia.”

The children first marched,

two by two, round the lawn,

and then down the centre.

When they reached the end,

one leader turned off to the[Pg 66]

right, and the other to the

left, each followed by a single

line of the children.

Passing round the lawn,

they came together again on

the other side. Then they

formed a great circle, a circle

within a circle, and concluded

the march with the

“grand basket.”

This was certainly a very

simple play, but the children

enjoyed it ever so much[Pg 67]—I

mean all but vain Master

Woggs, who was so greatly

displeased because he was

not chosen one of the leaders,

that he said there was

no fun at all in the whole

thing.

About half an hour was

spent in marching, and then

Mr. Lee proposed a second

game. The children wanted

to march a little longer; but

there were a great number[Pg 68]

of things to be done before

night, and so it was thought

best, on the whole, to try a

new game.

[Pg 69]

[Pg 70]

The Old Fiddler.

The Old Fiddler.[Pg 71]

IV.

When the children had done

marching, Mrs. Lee took charge

of the games. Several new

plays, which none of them had

heard of before, were introduced.

The boys and girls

all liked them very well, and

the time passed away most

rapidly.

Just before they were going[Pg 72]

to supper, an old man,

with a fiddle in his hand, tottered

into the garden, and

down the lawn. He was a

very queer-looking old man.

He had long white hair, and

a long white beard.

He was dressed in old,

worn-out, soldier clothes, in

part, and had a sailor’s hat

upon his head, so that they

could not tell whether he was

a soldier or a sailor.

As he approached the children,[Pg 73]

they began to laugh with

all their might; and he certainly

was a very funny old

man. His long beard and

hair, his tattered finery, and

his hobbling walk, would have

made almost any one laugh—much

more a company of children

as full of fun as those

who were attending the birthday

party.

“Children,” said the old[Pg 74]

man, as he took off his hat

and made a low bow, “I heard

there was a party here, and I

came to play the fiddle for

you. All the boys and girls

like a fiddle, because it is so

merry.”

“O mother! what did send

that old man here?” cried

Flora.

“He came of himself, I

suppose,” replied Mrs. Lee,

laughing.

“I think it is too bad to[Pg 75]

laugh at an old man like

him,” added Flora.

“It would be, if he were in

distress; but don’t you see he

is as merry as any of the children?”

“Play us some tunes,” said

the children.

“I will, my little dears;”

and the old man raised the fiddle.

“Let’s see—I will play

‘Napoleon’s Grand March.’”

The fiddler played, but he[Pg 76]

behaved so queerly that the

children laughed so loud they

could hardly hear the music.

“Why, that’s ‘Yankee Doodle,’”

said Henry Vernon; and

they all shouted at the idea

of calling that tune “Napoleon’s

Grand March.”

“Now I will play you the

solo to the opera of ‘La Sonnambula,’”

said the old man.

“Whew!” said Henry.

The old man fiddled again,[Pg 77]

with the same funny movements

as before.

“Why, that’s ‘Yankee Doodle’

too!” exclaimed Henry.

“I guess he don’t know

any other tune.”

“You like that tune so well,

I will play you ‘Washington’s

March;’” and the funny old

fiddler, with a great flourish,

began to play again; but still

it was “Yankee Doodle.”

And so he went on saying[Pg 78]

he would play many different

tunes, but he played nothing

but “Yankee Doodle.”

“Can’t you tell us a story

now?” asked Charley Green.

“O, yes, my little man, I can

tell you a story. What shall

it be?”

“Are you a soldier or a

sailor?”

“Neither, my boy.”

“The story! the story!”[Pg 79]

shouted the boys, very much

excited.

“Some years ago I was in

New York,” the old man commenced.

“Did you see me there?”

demanded Tommy Woggs.

“Well, my little man, I don’t

remember that I saw you.”

“O, I was there;” and Tommy

thrust his hands down to

the bottom of his pockets, and

strutted up the space between[Pg 80]

the children and the comical

old fiddler.

“I did see a very nice-looking

little gentleman——”

“That was me,” pompously

added Tommy.

“He was stalking up Broadway.

He thought every body

was looking at and admiring

him; but such was not the

case. He looked just like—just

like——”

“Like me?” asked Tommy.

“Like a sick monkey,” replied[Pg 81]

the fiddler.

“Go on with your story.”

“I will, children. Several

years ago I was in New York.

It is a great city; if you don’t

believe it, ask Master Tommy

Woggs.”

“You tell the truth, Mr.

Fiddler. It is a great city,

and I have been all over it,

and can speak from observation,”

replied Master Woggs.

“The story!” shouted the[Pg 82]

children.

“I was walking up Broadway.

This street is always

crowded with people, as well

as with carts and carriages.”

“I have seen that street,”

said Tommy.

“Now you keep still a few

minutes, Tommy, if you can,”

interposed Mrs. Lee.

“At the corner of Wall

Street——”

“I know where that is,” exclaimed[Pg 83]

Tommy.

“At the corner of Wall

Street there was a man with

a kind of cart, loaded with

apples and candy, which he

was selling to the passers-by.

Suddenly there came a stage

down the street, and ran into

the apple cart.”

“I saw the very same thing

done,” added Tommy, with his

usual self-important air.

“Keep still, Tom Woggs,”[Pg 84]

said Charley Green.

“The apples were scattered

all over the sidewalk; yet the

man picked up all but one of

them, though he was very angry

with the driver of the

stage for running against his

cart.”

“Why didn’t he pick up the

other apple?” asked Henry.

“A well-dressed man, with

big black whiskers, picked that[Pg 85]

up. ‘Give it to me,’ said the

apple man. ‘I will not,’ replied

the man with whiskers.

The apple merchant was as

mad as he could be; and then

the man with black whiskers

put his hand in his pocket and

drew out a knife. The blade

was six inches long.”

“O, dear me!” exclaimed

Flora.

“Raising the knife, he at

once moved towards the angry[Pg 86]

apple merchant, and—and——”

“Well, what?” asked several,

eagerly.

“And cut a piece out of

the apple, and put it in his

mouth.”

The children all laughed

heartily, for they were sure

the man with the whiskers

was going to stab the apple

merchant.

“He then took two cents[Pg 87]

from his pocket, paid for the

apple, and went his way,” continued

the old man. “Now,

there is one thing more I can

do. I want to run a race with

these boys.”

“Pooh! You run a race!”

sneered Charley.

“I can beat you.”

“Try it, and see.”

The old man and Charley

took places, and were to start

at the word from Henry. But[Pg 88]

when it was given, the fiddler

hobbled off, leaving Charley

to follow at his leisure.

When the old man had got

half way round the lawn, Charley

started, sure he could catch

him long before he reached

the goal. But just as the boy

was coming up with the man,

the latter began to run, and

poor Charley found, much to

his surprise, that he ran very

fast. He was unable to overtake[Pg 89]

him, and consequently

lost the race.

The children were much

astonished when they saw the

old man run so fast. He appeared

to have grown young

all at once. But he offered

to race with any of the boys

again; and half a dozen of

them agreed to run with him.

“I guess I will take my

coat off this time,” said the

fiddler.

As he threw away the coat,[Pg 90]

he slipped off the wig and

false beard he wore; and the

children found, to their surprise,

that the old man was

Mr. Lee, who had dressed

himself up in this disguise to

please them.

The supper was now ready,

and all the children were invited

to the tent. They had

played so hard that all of

them had excellent appetites,[Pg 91]

and the supper was just as

nice as a supper could be.

It was now nearly dark,

and the children had to go

home; but all of them declared

the birthday party of

Flora was the best they ever

attended.

“Only to think,” said Flora,

when she went to bed that

night, “the old fiddler was my

father!”

[Pg 92]

LIZZIE.

Mother, what ails our Lizzie dear,

So cold and still she lies?

She does not speak a word to-day,

And closed her soft blue eyes.

Why won’t she look at me again,

And laugh and play once more?

I cannot make her look at me

As she used to look before.

Her face and neck as marble white,[Pg 93]

And, O, so very cold!

Why don’t you warm her, mother dear,

Your cloak around her fold?

Her little hand is cold as ice,

Upon her waveless breast,—

So pure, I thought I could see through

The little hand I pressed.

Your darling sister’s dead, my child;

She cannot see you now;

The damps of death are gath’ring there

Upon her marble brow.

She cannot speak to you again,[Pg 94]

Her lips are sealed in death;

That little hand will never move,

Nor come that fleeting breath.

All robed in white, and decked with flowers,

We’ll lay her in the tomb;

The flower that bloomed so sweetly here,

No more on earth will bloom;

But in our hearts we’ll lay her up,

And love her all the more,

Because she died in life’s spring time,

Ere earth had won her o’er.

Nay, nay, my child, she is not dead,[Pg 95]

Although she slumbers there,

And cold and still her marble brow,

And free from pain and care.

She slept, and passed from earth to heaven,

And won her early crown:

An angel now she dwells above,

And looks in triumph down.

She is not dead, for Jesus died

That she might live again.

“Forbid them not,” the Saviour said,

And blessed dear sister then.

Her little lamp this morn went out[Pg 96]

On earth’s time-bounded shore;

But angels bright in heaven this morn

Relighted it once more.

Some time we, too, shall fall asleep,

To wake in heaven above,

And meet our angel Lizzie there

In realms of endless love.

We’ll bear sweet sister in our hearts,

And then there’ll ever be

An angel there to keep our souls

From sin and sorrow free.

Comments on "The Birthday Party: A Story for Little Folks" :