The Project Gutenberg eBook of Buffalo Land

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Buffalo Land

Author: W. E. Webb

Release date: May 12, 2012 [eBook #39674]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Julia Miller, Julia Neufeld and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BUFFALO LAND ***

BUFFALO LAND:

AN

Authentic Account

OF THE

Discoveries, Adventures, and Mishaps of a Scientific

and Sporting Party

IN THE WILD WEST;

WITH

GRAPHIC DESCRIPTIONS OF THE COUNTRY; THE RED MAN, SAVAGE

AND CIVILIZED; HUNTING THE BUFFALO, ANTELOPE,

ELK, AND WILD TURKEY; ETC., ETC.

REPLETE WITH INFORMATION, WIT, AND HUMOR.

The Appendix Comprising a Complete Guide for Sportsmen and Emigrants.

BY

W. E. WEBB,

OF TOPEKA, KANSAS.

Profusely Illustrated

FROM ACTUAL PHOTOGRAPHS, AND ORIGINAL DRAWINGS BY HENRY WORRALL.

CINCINNATI and CHICAGO:

E HANNAFORD & COMPANY.

SAN FRANCISCO: F. DEWING & CO.

1872.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by

E. HANNAFORD & CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

STEREOTYPED AT THE FRANKLIN TYPE FOUNDRY, CINCINNATI.

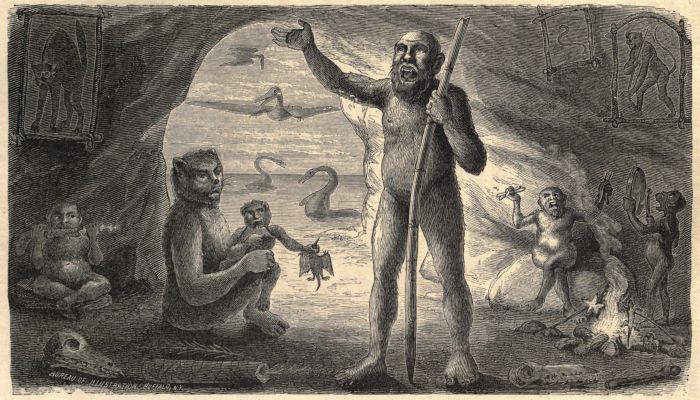

TO

The Primeval Man,

The Original Westerner, and First Buffalo Hunter,

This Work is Dedicated,

With Profound Regard,

BY THE AUTHOR.

[vii]

BUFFALO LAND.

BY OUR TAMMANY SACHEM.

There's a wonderful land far out in the West,

Well worthy a visit, my friend;

There, Puritans thought, as the sun went to rest,

Creation itself had an end.

'T is a wild, weird spot on the continent's face,

A wound which is ghastly and red,

Where the savages write the deeds of their race

In blood that they constantly shed.

The graves of the dead the fair prairies deface,

And stamp it the kingdom of dread.

The emigrant trail is a skeleton path;

You measure its miles by the bones;

There savages struck, in their merciless wrath,

And now, after sunset, the moans,

When tempests are out, fill the shuddering air,

And ghosts flit the wagons beside,

And point to the skulls lying grinning and bare

And beg of the teamsters a ride;

Sometimes 't is a father with snow on his hair,

Again, 't is a youth and his bride.

What visions of horror each valley could tell,

If Providence gave it a tongue!

How often its Eden was changed to a hell,

In which a whole train had been flung;

[viii]How death cry and battle-shout frightened the birds,

And prayers were as thick as the leaves,

And no one to catch the poor dying one's words

But Death, as he gathered his sheaves:

You see the bones bleaching among the wild herds,

In shrouds that the field spider weaves.

That era is passing—another one comes,

The era of steam and the plow,

With clangor of commerce and factory hums,

Where only the wigwam is now.

Like mist of the morning before the bright sun,

The cloud from the land disappears;

The Spirit of Murder his circle has run

And fled from the march of the years;

The click of machine drowns the click of the gun,

And day hides the night time of tears.

[ix]

PREFACE.

The purpose of this work is to make the reader

better acquainted with that wild land which he has

known from childhood, as the home of the Indian

and the buffalo. The Rocky Mountain chain, distorted

and rugged, has been aptly called the colossal

vertebræ of our continent's broad back, and from

thence, as a line, the plains, weird and wonderful,

stretch eastward through Colorado, and embrace

the entire western half of Kansas.

Fortune, not long since, threw in my way an invitation,

which I gladly accepted, to join a semi-scientific

party, since somewhat known to fame

through various articles in the newspaper press, in

a sojourn of several months on the great plains.

At a meeting held with due solemnity on the eve

of starting, the Professor (to whom the reader will

be introduced in the proper connection) was chosen

leader of the expedition, while to my lot fell the[x]

office of editor of the future record, or rather Grand

Scribe of what we were pleased to call our "Log

Book." The latter now lies before me, in all its

glory of shabby covers and dirty pages. Its soiled

face is as honorable as that of the laborer who

comes from his task in a well harvested field. Out

of the sheaves gathered during our journey, I shall

try and take such portions as may best supply the

mental cravings of the countless thousands who

hunger for the life and the lore of the far West.

I have given the mistakes as well as triumphs of

our expedition, and the members of the party will

readily recognize their familiar camp names. The

disguise will probably be pleasant, as few like to see

their failures on public parade, preferring rather to

leave these in barracks, and let their successes only

appear at review.

The plains have a face, a people, and a brute

creation, peculiarly their own, and to these our

party devoted earnest study. The expedition presented

a rare opportunity of becoming acquainted

with the game of the country; and, in writing the

present volume, my aim has been to make it so far

a text-book for amateur hunters that they may

become at once conversant with the habits of the

game, and the best manner of killing it. The time

is not far distant, when the plains and the Rocky[xi]

Mountains will be sought by thousands annually, as

a favorite field for sport and recreation.

Another and still larger class, it is hoped, will

find much of interest and value in the following

pages. From every state in the Union, people are

constantly passing westward. We found emigrant

wagons on spots from which the Indians had just

removed their wigwams. Multitudes more are now

on the way, with the earnest purpose of founding

homes and, if possible, of finding fortunes. In

order to aid this class, as well as the sportsman, I

have gathered in an appendix such additional information

as may be useful to both.

The scientific details of our trip will probably be

published in proper form and time, by the savans

interested. In regard to these, my object has been

simply to chronicle such matters as made an impression

upon my own mind, being content with

what cream might be gathered by an amateur's

skimming, while the more bulky milk should be

saved in capacious scientific buckets.

Professor Cope, the well known naturalist, of the

Academy of Sciences, Philadelphia, received for examination

and classification the most valuable

fossils we obtained, and to him I am indebted for

a large amount of most interesting and valuable[xii]

scientific matter, which will be found embodied in

chapters twenty-third and twenty-fourth.

The illustrations of men and brutes in this work

are studies from life. Whenever it was possible,

we had photographs taken.

The plains, it must be said, are a tract with

which Romance has had much more to do than

History. Red men, brave and chivalrous, and unnatural

buffalo, with the habits of lions, exist only

in imagination. In these pages, my earnest endeavor,

when dealing with actualities, has been to

"hold the mirror up to Nature," and to describe

men, manners, and things as they are in real life

upon the frontiers, and beyond, to-day.

W. E. W.

Topeka, Kansas, May, 1872.

[xiii]

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGES. | |

| THE OBJECT OF OUR EXPEDITION—A GLIMPSE OF ALASKA THROUGH CAPTAIN | |

| WALRUS' GLASS—WE ARE TEMPTED BY OUR RECENT PURCHASE—ALASKAN | |

| GAME OF "OLD SLEDGE"—THE EARLY STRUGGLES OF KANSAS—THE | |

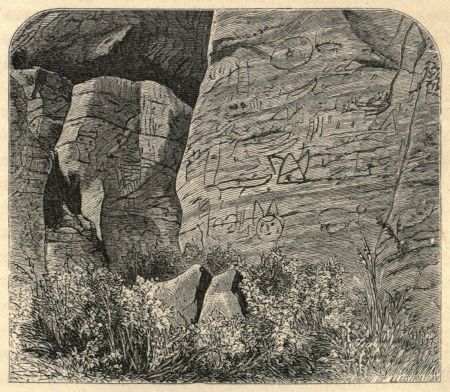

| SMOKY HILL TRAIL—INDIAN HIGH ART—THE "BORDER-RUFFIAN," | |

| PAST AND PRESENT—TOPEKA—HOW IT RECEIVED ITS | |

| NAME—WAUKARUSA AND ITS LEGEND, | 25-35 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A CHAPTER OF INTRODUCTIONS—PROFESSOR PALEOZOIC—TAMMANY SACHEM—DOCTOR | |

| PYTHAGORAS—GENUINE MUGGS—COLON AND SEMI-COLON—SHAMUS | |

| DOBEEN—TENACIOUS GRIPE—BUGS AND PHILOSOPHY—HOW | |

| GRIPE BECAME A REPUBLICAN, | 36-54 |

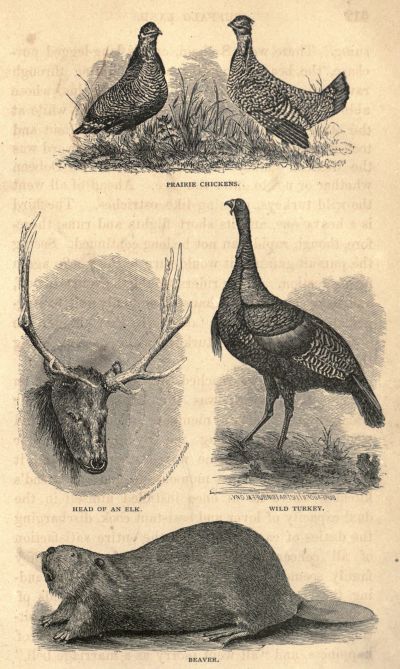

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE TOPEKA AUCTIONEER—MUGGS GETS A BARGAIN—CYNOCEPHALUS—INDIAN | |

| SUMMER IN KANSAS—HUNTING PRAIRIE CHICKENS—OUR FIRST | |

| DAY'S SPORT, | 55-63 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| CHICKEN-SHOOTING CONTINUED—A SCIENTIFIC PARTY TAKE THE BIRDS ON | |

| THE WING—EVILS OF FAST FIRING—AN OLD-FASHIONED "SLOW SHOT"—THE | |

| HABITS OF THE PRAIRIE CHICKEN—ITS PROSPECTIVE EXTINCTION—MODE | |

| OF HUNTING IT—THE GOPHER SCALP LAW, | 64-74 |

| [xiv] | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| A TRIAL BY JUDGE LYNCH—HUNG FOR CONTEMPT OF COURT—QUAIL | |

| SHOOTING—HABITS OF THE BIRDS, AND MODE OF KILLING THEM—A | |

| RING OF QUAILS—THE EFFECTS OF A SEVERE WINTER—THE SNOW | |

| GOOSE, | 75-83 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| OFF FOR BUFFALO LAND—THE NAVIGATION OF THE KAW—FORT RILEY—THE | |

| CENTER-POST OF THE UNITED STATES—OUR PURCHASE OF HORSES—"LO" | |

| AS A SAVAGE AND AS A CITIZEN—GRIPE UNFOLDS THE INDIAN | |

| QUESTION—A BALLAD BY SACHEM, PRESENTING ANOTHER VIEW, | 84-98 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| GRIPE'S VIEWS OF INDIAN CHARACTER—THE DELAWARES, THE ISHMAELITES | |

| OF THE PLAINS—THE TERRITORY OF THE "LONG HORNS"—TEXANS | |

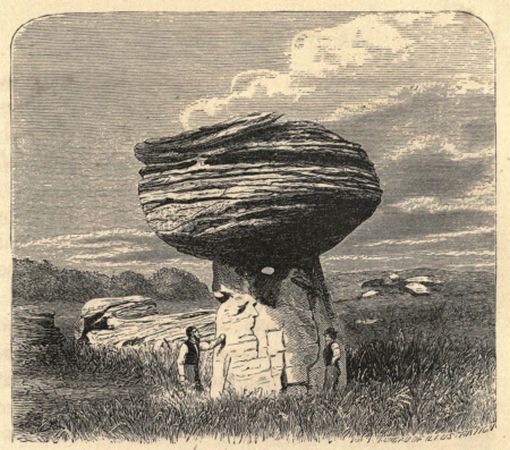

| AND THEIR CHARACTERISTICS—MUSHROOM ROCK—A VALUABLE DISCOVERY—FOOTPRINTS | |

| IN THE ROCK—THE PRIMEVAL PAUL AND | |

| VIRGINIA, | 99-111 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE "GREAT AMERICAN DESERT"—ITS FOSSIL WEALTH—AN ILLUSION DISPELLED—FIRES | |

| ACCORDING TO NOVELS AND ACCORDING TO FACT—SENSATIONAL | |

| HEROES AND HEROINES—PRAIRIE DOGS AND THEIR HABITS—HAWK | |

| AND DOG, AND HAWK AND CAT, | 112-123 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| WE SEE BUFFALO—ARRIVAL AT HAYS—GENERAL SHERIDAN AT THE FORT—INDIAN | |

| MURDERS—BLOOD-CHRISTENING OF THE PACIFIC RAILROAD—SURPRISED | |

| BY A BUFFALO HERD—A BUFFALO BULL IN A QUANDARY—GENTLE | |

| ZEPHYRS—HOW A CIRCUS WENT OFF—BOLOGNA TO LEAN ON—A | |

| CALL UPON SHERIDAN, | 124-141 |

| [xv] | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| HAYS CITY BY LAMP-LIGHT—THE SANTA FE TRADE—BULL-WHACKERS—MEXICANS—SABBATH | |

| ON THE PLAINS—THE DARK AGES—WILD BILL | |

| AND BUFFALO BILL—OFF FOR THE SALINE—DOBEEN'S GHOST-STORY—AN | |

| ADVENTURE WITH INDIANS—MEXICAN CANNONADE—A RUNAWAY, | 142-160 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| WHITE WOLF, THE CHEYENNE CHIEF—HUNGRY INDIANS—RETURN TO HAYS—A | |

| CHEYENNE WAR PARTY—THE PIPE OF PEACE—THE COUNCIL | |

| CHAMBER—WHITE WOLF'S SPEECH, AS RENDERED BY SACHEM—THE | |

| WHITE MAN'S WIGWAM, | 161-176 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| ARMS OF A WAR PARTY—A DONKEY PRESENT—EATING POWERS OF THE | |

| NOMADS—SATANTA, HIS CRIMES AND PUNISHMENT—RUNNING OFF | |

| WITH A GOVERNMENT HERD—DAUB, OUR ARTIST—ANTELOPE CHASE | |

| BY A GREYHOUND, | 177-191 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| CHARACTER OF THE PLAINS—BUFFALO BILL AND HIS HORSE BRIGHAM—THE | |

| GUIDE AND SCOUT OF ROMANCE—CAYOTE VERSUS JACKASS-RABBIT—A | |

| LAWYER-LIKE RESCUE—OUR CAMP ON SILVER CREEK—UNCLE | |

| SAM'S BUFFALO HERDS—TURKEY-SHOOTING—OUR FIRST MEAL ON THE | |

| PLAINS—A GAME SUPPER, | 192-208 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A CAMP-FIRE SCENE—VAGABONDIZING—THE BLACK PACER OF THE PLAINS—SOME | |

| ADVICE FROM BUFFALO BILL ABOUT INDIAN FIGHTING—LO'S | |

| ABHORRENCE OF LONG RANGE—HIS DREAD OF CANNON—AN IRISH | |

| GOBLIN, | 209-219 |

| [xvi] | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| A FIRE SCENE—A GLIMPSE OF THE SOUTH—'COON HUNTING IN MISSISSIPPI—VOICES | |

| IN THE SOLITUDE—FRIENDS OR FOES—A STARTLING | |

| SERENADE—PANIC IN CAMP—CAYOTES AND THEIR HABITS—WORRYING | |

| A BUFFALO BULL—THE SECOND DAY—DAUB, OUR ARTIST—HE | |

| MAKES HIS MARK, | 220-235 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| BISON MEAT—A STRANGE ARRIVAL—THE SYDNEY FAMILY—THE HOME | |

| IN THE VALLEY—THE SOLOMON MASSACRE—THE MURDER OF THE | |

| FATHER AND THE CHILD—THE SETTLERS' FLIGHT—INCIDENTS—OUR | |

| QUEEN OF THE PLAINS—THE PROFESSOR INTERESTED—IRISH MARY—DOBEEN | |

| HAPPY—THE HEROINE OF ROMANCE—SACHEM'S BATH BY | |

| MOONLIGHT—THE BEAVER COLONY, | 236-249 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| PREPARATIONS FOR THE CHASE—THE VALLEY OF THE SALINE—QUEER | |

| 'COONS—A BISON'S GAME OF BLUFF—IN PURSUIT—ALONGSIDE THE | |

| GAME—FIRING FROM THE SADDLE—A CHARGE AND A PANIC—FALSE | |

| HISTORY AGAIN—GOING FOR AMMUNITION—THE PROFESSOR'S LETTER—DISROBING | |

| THE VICTIM, | 250-263 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| STILL HUNTING—DARK OBJECTS AGAINST THE HORIZON—THE RED MAN | |

| AGAIN—RETREAT TO CAMP—PREPARATIONS FOR DEFENSE—SHAKING | |

| HANDS WITH DEATH—MR. COLON'S BUGS—THE EMBASSADORS—A NEW | |

| ALARM—MORE INDIANS—TERRIFIC BATTLE BETWEEN PAWNEES AND | |

| CHEYENNES—THEIR MODE OF FIGHTING—GOOD HORSEMANSHIP—A | |

| SCIENTIFIC PARTY AS SEXTONS—DITTO AS SURGEONS—CAMPS OF THE | |

| COMBATANTS—STEALING AWAY—AN APPARITION, | 264-279 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| STALKING THE BISON—BUFFALO AS OXEN—EXPENSIVE POWER—A BUFFALO | |

| AT A LUNATIC ASYLUM—THE GATEWAY TO THE HERDS—INFERNAL | |

| [xvii]GRAPE-SHOT—NATURE'S BOMB-SHELLS—CRAWLING BEDOUINS—"THAR | |

| THEY HUMP"—THE SLAUGHTER BEGUN—AN INEFFECTUAL | |

| CHARGE—"KETCHING THE CRITTER"—RETURN TO CAMP—CALVES' | |

| HEAD ON THE STOMACH—AN UNPLEASANT EPISODE—WOLF BAITING, | |

| AND HOW IT IS DONE, | 280-291 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| THE CAYOTES' STRYCHNINE FEAST—CAPTURING A TIMBER WOLF—A FEW | |

| CORDS OF VICTIMS—WHAT THE LAW CONSIDERS "INDIAN TAN"—"FINISHING" | |

| THE NEW YORK MARKET—A NEW YORK FARMER'S | |

| OPINION OF OUR GRAY WOLF—WESTWARD AGAIN—EPISODES IN OUR | |

| JOURNEY—THE WILD HUNTRESS OF THE PLAINS—WAS OUR GUIDE A | |

| MURDERER?—THE READER JOINS US IN A BUFFALO CHASE—THE | |

| DYING AGONIES, | 292-305 |

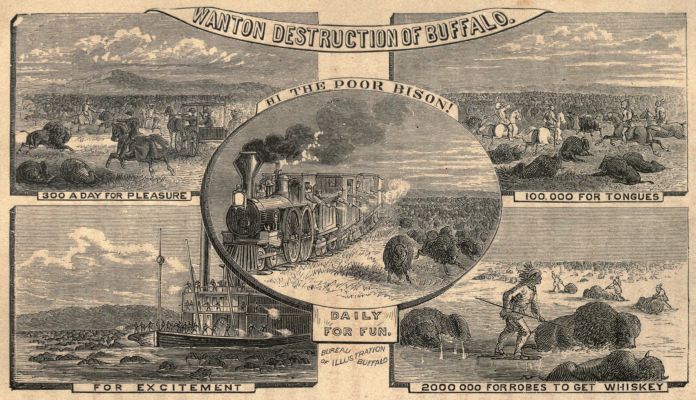

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| "CREASING" WILD HORSES—MUGGS DISAPPOINTED—A FEAT FOR FICTION—HORSE | |

| AND MONKEY—HOOF WISDOM FOR TURFMEN—PROSPECTIVE | |

| CLIMATIC CHANGES ON THE PLAINS—THE QUESTION OF | |

| SPONTANEOUS GENERATION—WANTON SLAUGHTER OF BUFFALO—AMOUNT | |

| OF ROBES AND MEAT ANNUALLY WASTED—A STRANGE | |

| HABIT OF THE BISON—NUMEROUS BILLS—THE "SNEAK THIEF" OF | |

| THE PLAINS, | 306-317 |

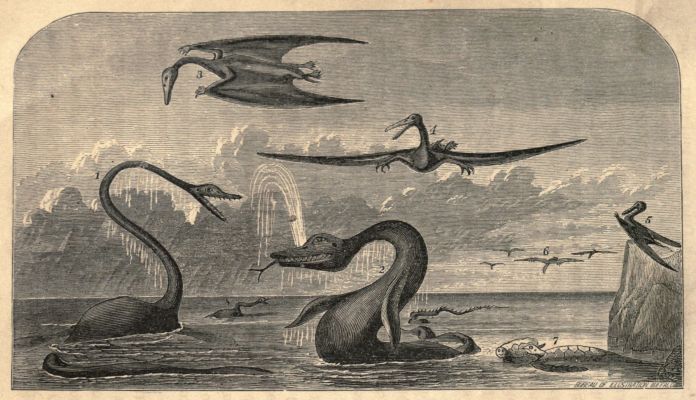

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| A LIVE TOWN AND ITS GRAVE-YARD—HONEST ROMBEAUX IN TROUBLE—JUDGE | |

| LYNCH HOLDS COURT—MARIE AND THE VINE-COVERED COTTAGE—THE | |

| TERRIBLE FLOODS—DEATH IN CAMP AND IN THE DUGOUT—WAS | |

| IT THE WATER WHICH DID IT?—DISCOVERY OF A HUGE | |

| FOSSIL—THE MOSASAURUS OF THE CRETACEOUS SEA—A GLIMPSE | |

| OF THE REPTILIAN AGE—REMINISCENCES OF ALLIGATOR-SHOOTING—THEY | |

| SUGGEST A THEORY, | 318-329 |

| [xviii] | |

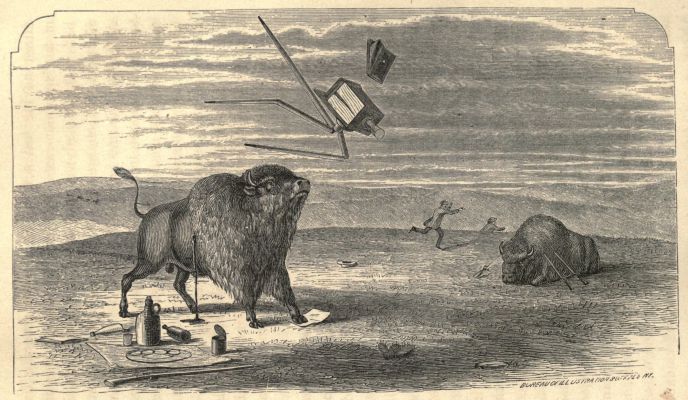

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| FROM SHERIDAN TO THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS—THE COLORADO PORTION OF | |

| THE PLAINS—THE GIANT PINES—ATTEMPT TO PHOTOGRAPH A BUFFALO—THINGS | |

| GET MIXED—THE LEVIATHAN AT HOME—A CHAT | |

| WITH PROFESSOR COPE—TWENTY-SIX-INCH OYSTERS—REPTILES AND | |

| FISHES OF THE CRETACEOUS SEA, | 330-350 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| CONTINUED BY COPE—THE GIANTS OF THE SEAS—TAKING OUT FOSSILS | |

| IN A GALE—INTERESTING DISCOVERIES—THE GEOLOGY OF THE | |

| PLAINS, | 351-365 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| A SAVAGE OUTBREAK—THE BATTLE OF THE FORTY SCOUTS—THE SURPRISE—PACK-MULES | |

| STAMPEDED—DEATH ON THE ARICKEREE—THE | |

| MEDICINE MAN—A DISMAL NIGHT—MESSENGERS SENT TO WALLACE—MORNING | |

| ATTACK—WHOSE FUNERAL?—RELIEF AT LAST—THE OLD | |

| SCOUT'S DEVOTION TO THE BLUE, | 366-376 |

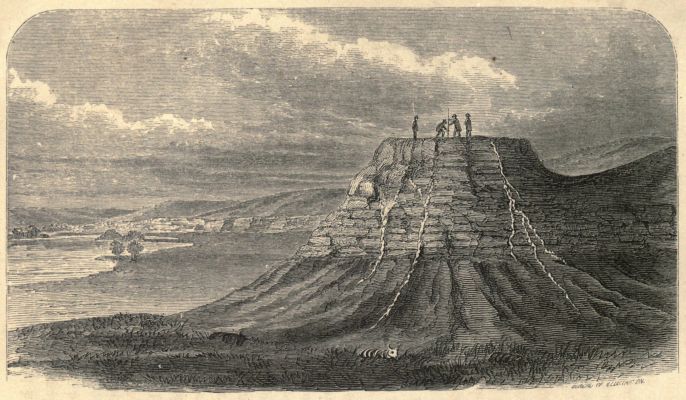

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| THE STAGE DRIVERS OF THE PLAINS—"OLD BOB"—JAMAICA AND GINGER—AN | |

| OLD ACQUAINTANCE—BEADS OF THE PAST—ROBBING THE | |

| DEAD—A LEAP FROM THE LOST HISTORY OF THE MOUND BUILDERS—INDIAN | |

| TRADITIONS—SPECULATIONS—ADOBE HOUSES IN A RAIN—CHEAP | |

| LIVING—WATCH TOWERS, | 377-386 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| OUR PROGRAMME CONCLUDED—FROM SHERIDAN TO THE SOLOMON—FIERCE | |

| WINDS—A TERRIFIC STORM—SHAMUS' BLOODY APPARITION AND | |

| INDIAN WITCH—A RECONNOISSANCE—AN INDIAN BURIAL GROVE—A | |

| CONTRACTOR'S DARING AND ITS PENALTY—MORE VAGABONDIZING—JOSE | |

| [xix]AT THE LONG BOW—THE "WILD HUNTRESS'" COUNTERPART—SHAMUS | |

| TREATS US TO "CHILE"—THE RESULT, | 387-395 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| THE BLOCK-HOUSE ON THE SOLOMON—HOW THE OLD MAN DIED—WACONDA | |

| DA—LEGEND OF WA-BOG-AHA AND HEWGAW—SABBATH MORNING—SACHEM'S | |

| POETICAL EPITAPH—AN ALARM—BATTLE BETWEEN AN | |

| EMIGRANT AND THE INDIANS—WAS IT THE SYDNEYS?—TO THE | |

| RESCUE—AN ELK HUNT—ROCKY MOUNTAIN SHEEP—NOVEL MODE | |

| OF HUNTING TURKEYS—IN CAMP ON THE SOLOMON—A WARM WELCOME, | 396-415 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| OUR LAST NIGHT TOGETHER—THE REMARKABLE SHED-TAIL DOG—HE | |

| RESCUES HIS MISTRESS, AND BREAKS UP A MEETING—A SKETCH OF | |

| TERRITORIAL TIMES BY GRIPE—MONTGOMERY'S EXPEDITION FOR THE | |

| RESCUE OF JOHN BROWN'S COMPANIONS—SCALPED, AND CARVING HIS | |

| OWN EPITAPH—AN IRISH JACOB—"SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST"—SACHEM'S | |

| POETICAL LETTER—POPPING THE QUESTION ON THE RUN—THE | |

| PROFESSOR'S LETTER, | 416-428 |

[xx]

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX.

| PAGES. | |

| PRELIMINARY TO THE APPENDIX, | 431, 432 |

| CHAPTER FIRST. | |

| COME TO THE GREAT WEST—SHOULD THERE NOT BE COMPULSORY EMIGRATION—"GET | |

| A GOOD READY"—HOMESTEAD LAWS AND REGULATIONS—THE | |

| STATE OF KANSAS—THE COST OF A FARM—A FEW MORE | |

| PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS, | 433-450 |

| CHAPTER SECOND. | |

| HUNTING THE BUFFALO—ANTELOPE HUNTING—ELK HUNTING—TURKEY | |

| HUNTING—GENERAL REMARKS—WHAT TO DO IF LOST ON THE PLAINS—THE | |

| NEW FIELD FOR SPORTSMEN, | 451-463 |

| CHAPTER THIRD. | |

| "BY THE MOUTH OF TWO OR THREE WITNESSES"—THE GREAT WEST—FALL | |

| OF THE RIVERS—THE PRINCIPAL RIVERS AND VALLEYS OF | |

| BUFFALO LAND—THE VALLEY OF THE PLATTE—THE SOLOMON AND | |

| SMOKY HILL RIVERS—THE ARKANSAS RIVER AND ITS TRIBUTARIES—STOCK | |

| RAISING IN THE GREAT WEST—THE CATTLE HIVE OF NORTH | |

| AMERICA—THE CLIMATE OF THE PLAINS—CLIMATIC CHANGES ON THE | |

| PLAINS—THE TREES AND FUTURE FORESTS OF THE PLAINS—THE | |

| SUPPLY OF FUEL—DISTRICTS CONTIGUOUS TO THE PLAINS—THE VALLEYS | |

| OF THE WHITE EARTH AND NIOBRARA—NEW MEXICO: ITS | |

| SOIL, CLIMATE, RESOURCES, ETC.—THE DISAPPEARING BISON—THE | |

| FISH WITH LEGS—THE MOUNTAIN SUPPLY OF LUMBER FOR THE | |

| PLAINS, | 465-503 |

[xxi]

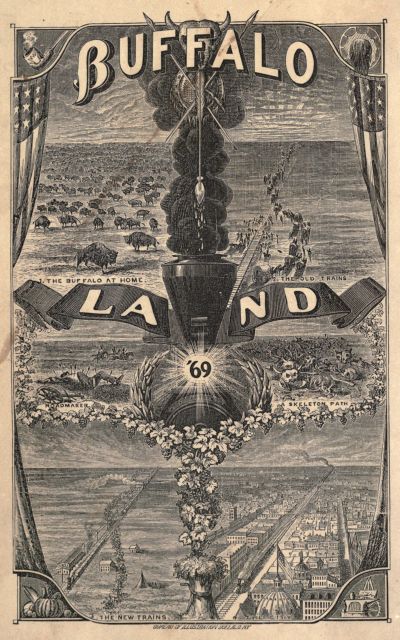

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

From Original Drawings by Henry Worrall, and Actual Photographs.

The Engraving by the Bureau of Illustration, Buffalo, N. Y.

| PAGE | |

| Frontispiece, | Facing Title Page |

| Alaskan Lovers—Sealing the Contract, | 27 |

| Alaskan Game of Old Sledge, | 27 |

| "Waukarusa," | 33 |

| "Toasts his Moccasined Feet by the Fire," | 33 |

| The Professor—a Remarkable Stone, | 39 |

| Tammany Sachem—Prospective and Retrospective, | 39 |

| Colon and Semi-colon, | 43 |

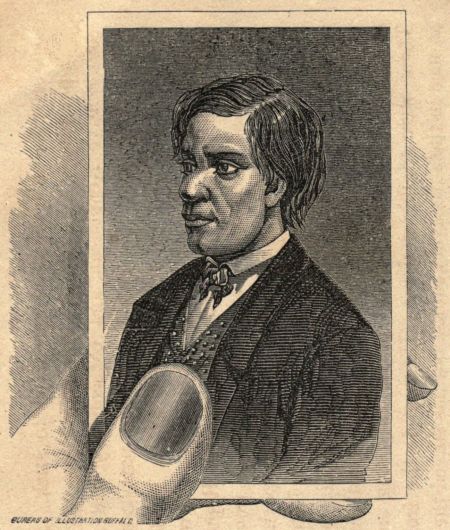

| David Pythagoras, M. D., | 43 |

| One of the Muggses, | 47 |

| Shamus Dobeen—His Card, | 53 |

| Hon. T. Gripe (Beatified), | 53 |

| "Sperit, Gentlemen!" | 57 |

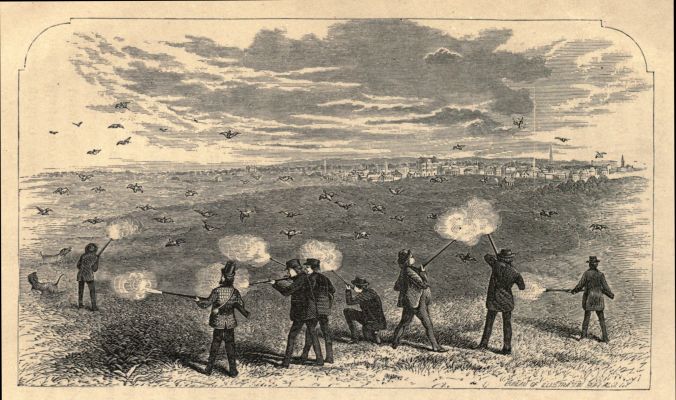

| Our First Bird-Shooting, | 67 |

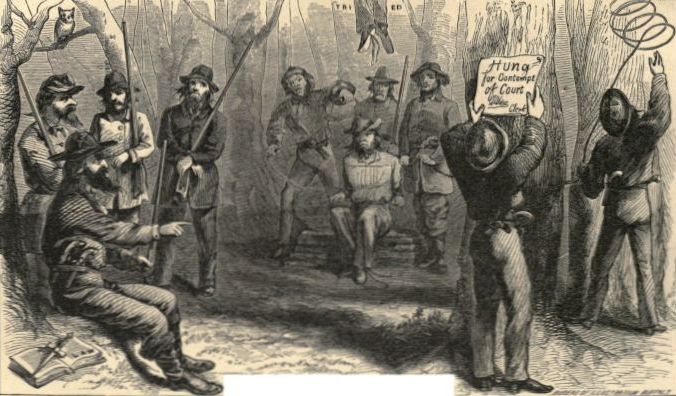

| Judge Lynch—His Court, | 77 |

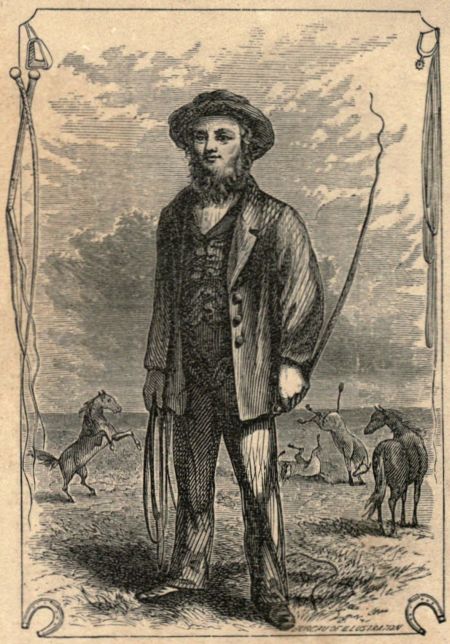

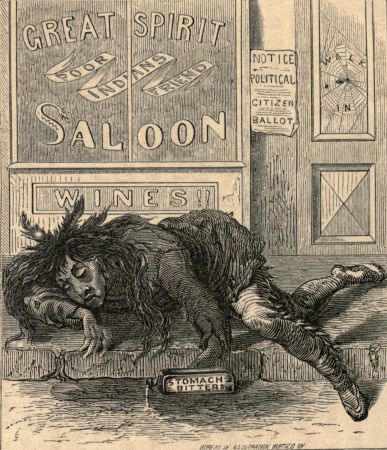

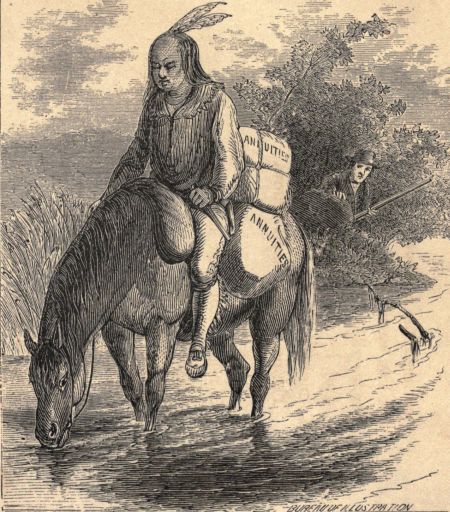

| Unnaturalized, | 91 |

| Naturalized, | 91 |

| [xxii]"You've Riled That Brook"—An Old Fable Modernized, | 96 |

| Dog Town—The Happy Family, | 96 |

| Indian Rock—From a Photograph, | 105 |

| Mushroom Rock—From a Photograph, | 105 |

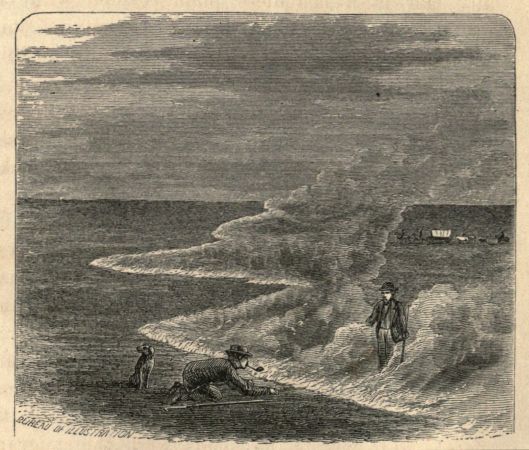

| Fire on the Plains, according to Novels, | 115 |

| Fire on the Plains, as it is, | 115 |

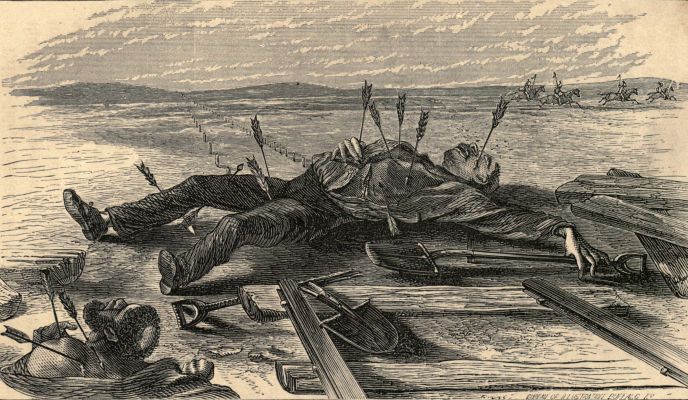

| "And Erin's Son Christens those Far-off Points of the Pacific Railroad with his Blood," | 127 |

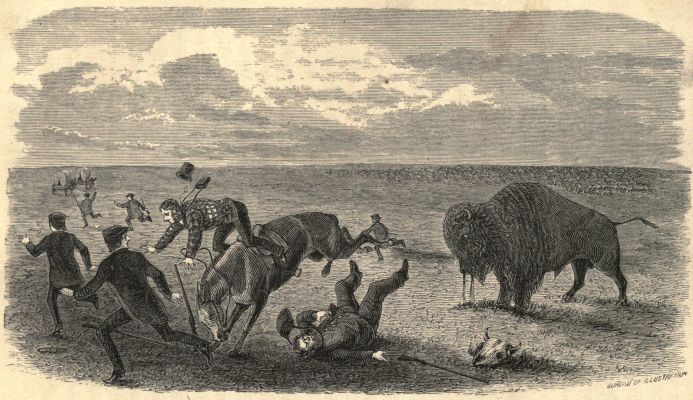

| Gentle Zephyrs—Going off without a Drawback, | 133 |

| "Looked like the End of a Tail," | 137 |

| The Rare Old Plainsman of the Novels, | 137 |

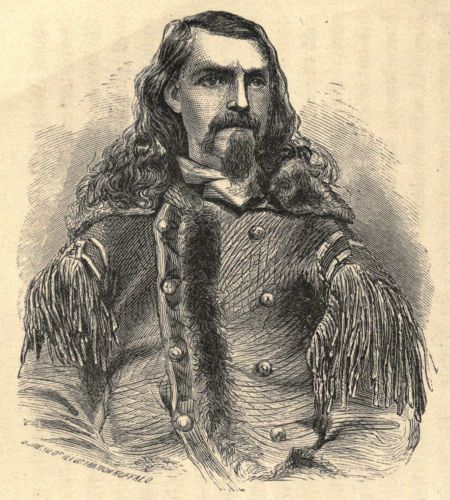

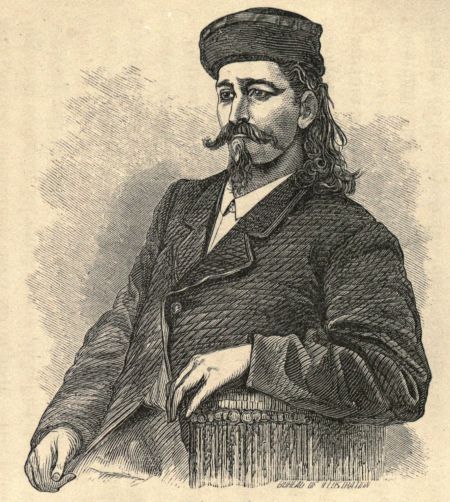

| Wild Bill—From a Photograph, | 147 |

| Buffalo Bill—From a Photograph, | 147 |

| Our Horses Run Away with Us, | 157 |

| The Pipe of Peace—The Professor's Dilemma, | 167 |

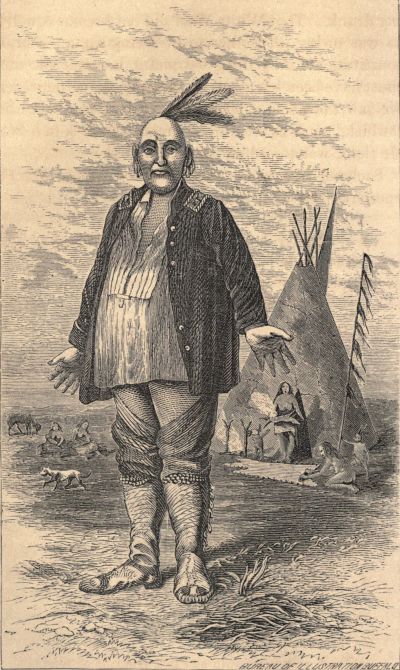

| White Wolf at Home, | 172 |

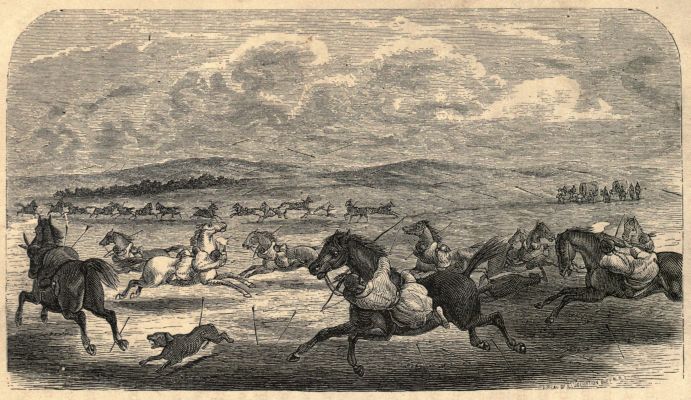

| The Wild Denizens of the Plains, | 197 |

| Smashing a Cheyenne Black-Kettle, | 219 |

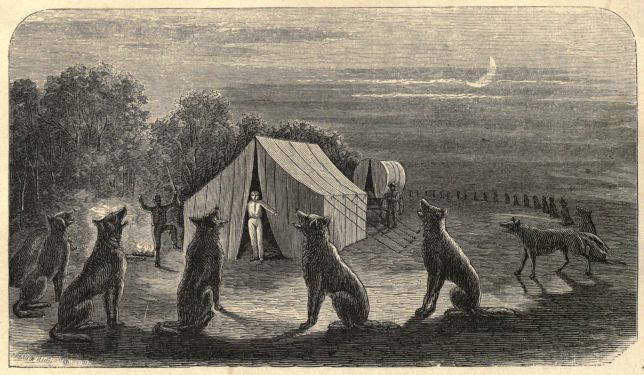

| Midnight Serenade on the Plains, | 227 |

| Going after Ammunition, | 259 |

| Battle between Cheyennes and Pawnees, | 271 |

| One of our Specimens—Photographed by J. Lee Knight, Topeka, | 301 |

| Wanton Destruction of Buffalo, Embracing: | |

| Daily, for Fun, | 315 |

| 300 a Day for Pleasure, | 315 |

| For Excitement, | 315 |

| 100,000 for Tongues, | 315 |

| 2,000,000 for Robes, to get Whisky, | 315 |

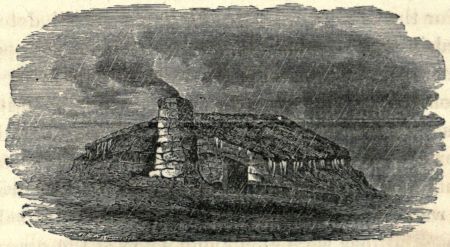

| Dug Out, | 329 |

| Taking and Being Taken, | 335 |

| Developing—One of the First Families, | 348 |

| The Sea which once Covered the Plains, | 357 |

| Waconda Da—Great Spirit Salt Spring, | 399 |

| [xxiii] | |

| More of our Specimens (Photographed by J. Lee Knight), Embracing: | |

| Prairie Chickens, | 413 |

| Head of an Elk, | 413 |

| Wild Turkey, | 413 |

| Beaver, | 413 |

[25]

BUFFALO LAND.

CHAPTER I.

THE OBJECT OF OUR EXPEDITION—A GLIMPSE OF ALASKA THROUGH CAPTAIN WALRUS'

GLASS—WE ARE TEMPTED BY OUR RECENT PURCHASE—ALASKAN GAME OF "OLD

SLEDGE"—THE EARLY STRUGGLES OF KANSAS—THE SMOKY HILL TRAIL—INDIAN

HIGH ART—THE "BORDER-RUFFIAN," PAST AND PRESENT—TOPEKA—HOW IT RECEIVED

ITS NAME—WAUKARUSA AND ITS LEGEND.

The great plains—the region of country in which

our expedition sojourned for so many months—is

wilder, and by far more interesting, than those solitudes

over which the Egyptian Sphynx looks out.

The latter are barren and desolate, while the former

teem with their savage races and scarcely more savage

beasts. The very soil which these tread is written all

over with a history of the past, even its surface giving

to science wonderful and countless fossils of those ages

when the world was young and man not yet born.

At first, it was rather unsettled which way the

steps of our party would turn; between unexplored

territory and that newly acquired, there were several

fields open which promised much of interest. Originally,

our company numbered a dozen; but Alaska

tempted a portion of our savans, and to the fishy and

frigid maiden they yielded, drawn by a strange predilection

for train-oil and seal meat toward the land of[26]

furs. For the remainder of our party, however, life

under the Alaskan's tent-pole had no charms. Our

decision may have been influenced somewhat by the

seafaring man with whom our friends were to sail.

The real name of this son of Neptune was Samuels,

but our party called him, as it savored more of salt

water, Captain Walrus, of the bark Harpoon. This

worthy, according to his own statement, had been

born on a whaler, weaned among the Esquimeaux,

and, moreover, had frozen off eight toes "trying to

winter it at our recent purchase." He evidently disliked

to have scientific men aboard, intent on studying

eclipses and seals. "A heathenish and strange people

are the Alaskans," Walrus was wont to say. "What

is not Indian is Russian, and a compound of the latter

and aboriginal is a mixture most villainous. One portion

of the partnership anatomy takes to brandy, while

the other absorbs train-oil, and so a half-breed Alaskan

heathen is always prepared for spontaneous combustion,

and if rubbed the wrong way, flames up instantly.

He is always hot for murder, and if you throw cold

water on his designs, his oily nature sheds it."

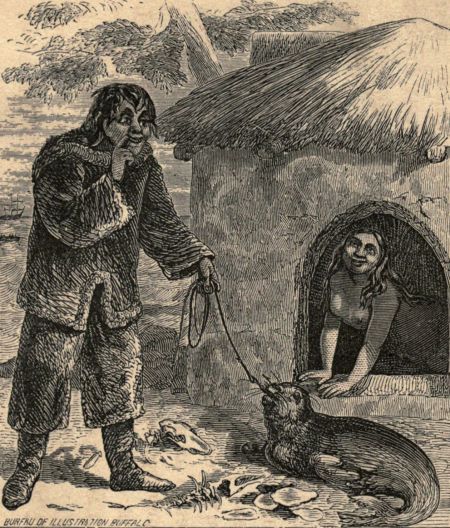

And many a yarn did the captain spin concerning

their strange customs. Sealing a marriage contract

consisted in the warrior leaving a fat seal at the hole

of the hut, where his intended crawled in to her

home privileges of smoke and fish. Their favorite

game was "old sledge," played with prisoners to

shorten their captivity.

ALASKAN LOVERS—SEALING THE CONTRACT.

ALASKAN GAME OF OLD SLEDGE.

All this, and much more, probably equally true, we

had picked up of Alaskan history, and at one time

our chests had been packed for a voyage on the Harpoon;

but at the final council the west carried it[29]

against the north, and our steps were directed toward

the setting sun, instead of the polar star.

The expedition afforded unexcelled facilities for

seeing Buffalo Land. It was composed of good material,

and pursued its chosen path successfully,

though under difficulties which would have turned

back a less determined party.

None of our company, I trust, will consider it an

unwarrantable license which recounts to others the

personal peculiarities and mistakes about which we

joked so freely while in camp. It was generally understood,

before we parted, that the adventures should

be common stock for our children and children's

children. Why should not the great public share in

it also?

Let the reader place before him a checker-board,

and allow it to represent Kansas, whose shape and

outline it much resembles; the half nearest him will

stand for the eastern or settled portion of the State,

of which the other half is embraced in Buffalo Land

proper. It is with the latter that we have first to do,

as with it we first became acquainted.

Our party entered the State at Kansas City, and

took the cars for Topeka, its capital. During our

morning ride through the valley of the Kaw, memory

went backward to the years when "Bleeding Kansas"

was the signal-cry of emancipation. When gray

old Time, a decade and a half ago, was writing the history

of those bright children of Freedom, the united

sisterhood, a virgin arm reached over his shoulder,

and a fair young hand, stained with its own life-blood,[30]

wrote on the page toward which all the world

was gazing, "I am Kansas, latest-born of America.

I would be free, yet they would make me a slave.

Save me, my sisters!" The great heart of our nation

was sorely distressed. Conscience pointed to one

path—Policy, that rank hypocrite, to another.

And so it was that the young queen, with her

grand domain in the West, struggled forward to lay

her fealty at the feet of our great mother, Liberty.

She made a body-guard of her own sons, and their

number was quickly swelled by brave hearts from the

north, east, and west. The new territory, begging

admission as a State, became a battle-ground.

Slavery had reached forth its hand to grasp the new

State and fresh soil, but the mutilated member was

drawn back with wounds which soon reached, corrupted

and destroyed the body. In this land of the

Far West a nation of young giants had been suddenly

developed, and Kansas was forever won for freedom.

But there was yet another enemy and another danger.

Westward, toward Colorado, the savage's tomahawk

and knife glittered, and struck among the

affrighted settlements. Ad Astra per Aspera, "to the

stars through difficulties," the State exclaims on the

seal, and to the stars, through blood, its course has

been.

Those old pages of history are too bloody to be

brought to light in the bright present, and we purpose

turning them only enough to gather what will be

now of practical use. Kansas suffered cruelly, and

brooded over her wrongs, but she has long since struck

hands with her bitterer foe. Most of the "Border[31]

Ruffians" ripened on gallows trees, or fell by the

sword, years ago. A few, however, are yet spared,

to cheer their old age by riding around in desolate

woods at midnight, wrapped in damp nightgowns,

and masked in grinning death-heads. Although the

mists of shadow-land are chilling their hearts, yet

those organs, at the cry of blood, beat quick again,

like regimental drums, for action.

The Kaw or the Kansas River, the valley of which

we were traversing, is the principal stream of the

State—in length to the mouth of the Republican one

hundred and fifty miles, and above that, under the

name of Smoky Hill, three hundred miles more.

The "Smoky Hill trail" is a familiar name in

many an American home. It was the great California

path, and many a time the demons of the plain

gloated over fair hair, yet fresh from a mother's touch

and blessing. And many a faint and thirsty traveler

has flung himself with a burst of gratitude on

the sandy bed of the desolate river, and thanked the

Great Giver of all good for the concealed life found

under the sand, and with the strength thus sucked

from the bosom of our much-abused mother, he has

pushed onward until at length the grand mountains

and great parks of Colorado burst upon his delighted

vision.

About noon we arrived at Topeka, the capital,

well situated on the south bank of the river, having

a comfortable, well-to-do air, which suggests the quiet

satisfaction of an honest burgher after a morning of

toil. The slavery billow of agitation rolled even thus

far from beyond the border of the state. Armed men[32]

rode over the beautiful prairies, some east, some

west—one band to transplant slavery from the tainted

soil of Missouri, another to pluck it up.

A small party of Free State men settled upon this

beautiful prairie. South flowed the Waukarusa,

south and east the Shunganunga, and west and north

the Kaw or Kansas. Here thrived a bulbous root,

much loved by the red man, and here lazy Pottawatomies

gathered in the fall to dig it. In size and

somewhat in shape, it resembled a goose egg, and had

a hard, reddish brown shell, and an interior like

damaged dough. The Indian gourmands ate it

greedily and called it "Topeka." From the two or

three families of refugee Free State men the town

grew up, and from the Indian root it took its

name. Its christening took place in the first cabin

erected, and it is reported that a now prominent

banker of the town stood sponsor, with his back

against the door, refusing any egress until the name

of his choice was accepted. It is even affirmed that

one opposing city founder was pulled back by his

coat-tail from an attempted escape up the wide

chimney.

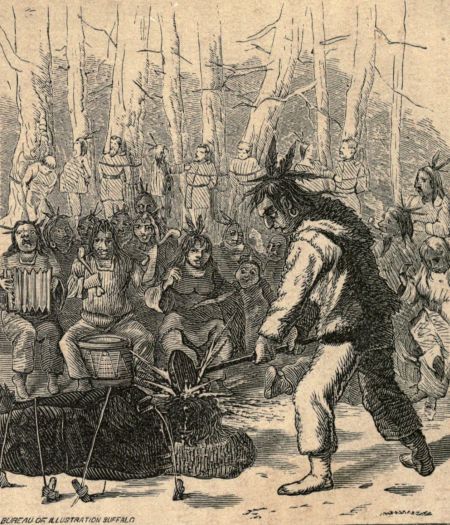

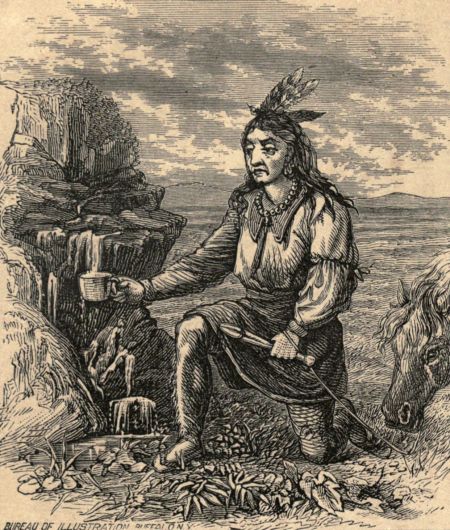

"WAUKARUSA."

"TOASTS HIS MOCCASINED FEET BY THE FIRE."

The old Indian love of commemorating events by

significant names is well illustrated in Kansas. One

example may be given here. Waukarusa once opposed

its swollen tide to an exploring band of red

men. Now, from time beyond ken, the noble savage

has been illustrious for the ingenuity with which he

lays all disagreeable duties upon the shoulders of the

patient squaw. He may ride to their death, in free

wild sport, the bison multitudes; but their skins[35]

must be converted into marketable robes, and the

flesh into jerked meat, by the ugly and over-worked

partner of his bosom. While she pins the raw hide

to earth, and bends patiently over, fleshing it with

horn hatchet for weary hours, the stronger vessel, his

abdominal recesses wadded with buffalo meat, toasts

his moccasined feet by the fire, fills his lungs with

smoke from villainous killikinick, and muses soothingly

of white scalps and happy hunting grounds.

Ox-like maiden, happy "big injun!" you both belong

to an age and a history well nigh past, and let us

rejoice that it is so.

But to return to the band long since gathered into

aboriginal dust whom we left pausing on the banks

of the Waukarusa. "Deep water, bad bottom!"

grunted the braves, and, nothing doubting it, one loving

warrior pushed his wife and her pony over the

bank to test the matter. From the middle of the

tide the squaw called back, "Waukarusa" (thigh

deep), and soon had gained the opposite bank in

safety. Then and there the creek received its name,

"Waukarusa."

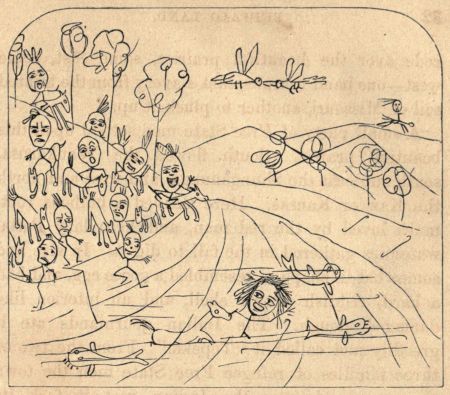

We procured a remarkable sketch, in the well

known Indian style of high art, commemorative of

this event. It has always struck us that the savage

order of drawing resembles very much that of the

ancient Egyptian—except in the matter of drawing

at sight, with bow or rifle, on the white man.

[36]

CHAPTER II.

A CHAPTER OF INTRODUCTIONS—PROFESSOR PALEOZOIC—TAMMANY SACHEM—DOCTOR

PYTHAGORAS—GENUINE MUGGS—COLON AND SEMI-COLON—SHAMUS DOBEEN—TENACIOUS

GRIPE—BUGS AND PHILOSOPHY—HOW GRIPE BECAME A REPUBLICAN.

When permission was given me to draw upon

the journal of our trip for such material as I

might desire, it was stipulated that the camp-names

should be adhered to. A company on the plains is

no respecter of persons, and titles which might have

caused offense before starting were received in good

part, and worn gracefully thenceforward.

Our leader, Professor Paleozoic, ordinarily existed

in a sort of transition state between the primary

and tertiary formations. He could tell cheese from

chalk under the microscope, and show that one was

full of the fossil and the other of the living evidences

of animal life. A worthy man, vastly more troubled

with rocks on the brain than "rocks" in the pocket.

Learning had once come near making him mad,

but from this sad fate he was happily saved by a

somewhat Pickwickian blunder. While in Kansas,

some years since, he penetrated a remote portion of

the wilderness, where, as he was happy in believing,

none but the native savage, or, possibly, the primeval

man, could ever have tarried long enough to leave

any sign behind. Imagine his astonishment and[37]

delight, therefore, when from the tangled grass he

drew an upright stone, with lines chiseled on three

sides and on the fourth a rude figure resembling

more than any thing else one of those odd fictions

which geologists call restored specimens. On a ledge

near were huge depressions like foot-prints. They

were foot-prints of birds, no doubt, and quite as perfect

as those found in more favored localities, and

from which whole skeletons had been constructed by

learned men.

Both specimens were forwarded to, and at the

expense of, noted savans of the East. Our professor

called the pillar from the tangled grass an altar

raised by early races to the winds. The short lines,

he suggested, designated the different points of the

compass, while the rude figure was intended for

Boreas. Our scientists toward the rising sun met

the boxes at the depot, paid charges, and careful

draymen bore them to the expectant museum.

One hour after, seven wise men might have been

seen wending their way sorrowfully homeward, with

hands crossed meditatively under their coat-tails, and

pocket vacuums where lately were modern coins.

Government clearly had a case against our professor.

Science decided that he had removed a stone telling

in surveyors' signs just what section and township

it was on. The figure which he had imagined a

heathen idea of Boreas was the fancy of some surveyor's

idle moment—a shocking sketch of an impossible

buffalo. Whether the bird-tracks had a

common origin, or were hewn by the hatchets of the

red man, is a point still under discussion.

[38]A worthy man, as before remarked, was the professor,

full of knowledge, genial in camp, and, having

rubbed his eye-tooth on a section stone, geological

authority of the highest order. When the professor

said a particular rock belonged to the cretaceous formation,

one might safely conclude that no modern

influences had been at work either on that rock or

in that vicinity. That question was settled.

Next came Tammany Sachem, our heavy weight

and our mystery. Before joining our party, he had

been a New York alderman, noted for prowess in

annual aldermanic clam-bakes at Coney Island. He

was wont to exhibit a medal, the prize of such a

tournament, on which several immense clams were

racing to the griddle, for the honor of being devoured

by the city fathers.

A green-ribbed hunting coat traversed his rotundity,

which had the generous swell of a puncheon.

His face was reddish, and his nose like a beacon-light

against a sunset sky. When you thought him

awake, he was half asleep; when you thought him

asleep, he was wide awake. A look of extreme

happiness always beamed on his face when misfortunes

impended. Per contra, successes made him

suspicious and morose. New York aldermen have

always been a puzzle to the nation at large. Perhaps

our friend's facial contradictions, put on originally

as one of the tricks of the trade, had become

chronic from long usage. We have since learned

that the sachems of Tammany laugh the loudest

and joke the most freely when under affliction.

THE PROFESSOR—A REMARKABLE STONE.

TAMMANY SACHEM—PROSPECTIVE AND RETROSPECTIVE.

When I was appointed editor, the Sachem volunteered[41]

as local reporter. Many of the items he

gathered are entered in our log-book in rhyme, and

to these pages some of them are transferred verbatim.

In wooing the muses, our alderman certainly

acted out of character. The ideal poet is thin instead

of obese, and he is a reckless innovator who

lays claim to any measure of the divine afflatus

without possessing either a pale face, thin form, or

a garret.

As to what drove a New York alderman to the

society of buffaloes, we had but one explanation,

and that was Sachem's own. We knew that he disliked

women in every form, Sorosis and Anti-Sorosis,

bitter and sweet alike. According to his statement,

made to us in good faith, and which I chronicle in

the same, Cupid had once essayed to drive a dart

into Sachem's heart, but, in doing so, the barb also

struck and wounded his liver. As his love increased,

his health failed. His liver became affected in the

same ratio as his heart. This was touching our

alderman in a tender spot. Imagine a New York

city father without digestion; what a subject of scorn

he would become to his constituency! Our alderman

fled from Cupid, clams, and his beloved Gotham, and

sought health and buffalo on the plains of Kansas.

As he remarked to us pathetically: "A good liver

makes a good husband. Indigestion frightens connubial

bliss out of the window. Pills, my boy, pills

is the quietus of love. If you wish Cupid to leave,

give him a dose of 'em. The liver, instead of the

heart, is at the bottom of half the suicides."

Doctor Pythagoras in years was fifty, and in stature[42]

short. His favorite theory was "development," and

this he carried to depths which would have astonished

Darwin himself. How humble he used to make us

feel by digging at the roots of the family tree until its

uttermost fiber lay between an oyster and a sponge!

(Rumor charged him with waiting so long for diseases

to develop, that his patients developed into spirits.)

While he indorsed Darwin, however, he also admired

Pythagoras. The latter's doctrine of metempsychosis

he Darwinized. In their transmigration from one

body to another, souls developed, taking a higher order

of being with each change, until finally fitted to

enter the land of spirits. The soul of a jack-of-all-trades

was one which developed slowly, and picked

up a new craft with each new body. Like Pythagoras,

he remembered several previous bodies which

his soul had animated, among others that of the original

Rarey, who existed in Egypt some centuries before

the modern usurper was born. If souls proved

entirely unworthy during the probationary or human

period, they were cast back into the brute creation to

try it over again. To this class belonged prize-fighters,

Congressmen, and the like. With them the past

was a blank—an unsuccessful problem washed from

the slate. The doctor had a hobby that a vicious

horse was only a vicious man entered into a lower order

of being. To demonstrate this he had traveled,

and still persisted in traveling, on eccentric horses,

for the purpose of reasoning with them. But his

Egyptian lore had been lost in transmission, and his

falls, kicks, and bites became as many as the moons

which had passed over his head.

COLON AND SEMI-COLON.

DAVID PYTHAGORAS, M. D.

[45]Genuine Muggs was an Englishman. The antipodes

of Tammany Sachem, who would not believe

any thing, Muggs swallowed every thing. He had

already absorbed so much in this way that he knew

all about the United States before visiting it. Given

half a chance, he would undoubtedly have told the

savage more about the latter's habits than the aborigine

himself knew. It was positively impossible

for him to learn any thing. His round British body

was so full of indisputable facts that another one

would have burst it. In the Presidential alphabet,

from Alpha Washington to Omega Grant, he knew

all of our rulers' tricks and trades, and understood

better the crooked ways of the White House than our

own talented Jenkins.

British phlegm incased his soul, and British

leather his feet. From heel to crown he was completely

a Briton. His mutton-chop whiskers came

just so far, and the h's dropped in and out of his utterings

in a perfectly natural way. In the Briton's

alphabet, Sachem used to remark, the I is so big that

it is no wonder the H is often crowded out.

Muggs was a fair representative of the average

Englishman who has traveled somewhat. The eye-teeth

of these persons are generally cut with a slash,

and they are forever after sore-mouthed. For a

maiden effort they never suck knowledge gently in,

but attempt a gulp which strangles. The consequence

of this hasty acquiring is a bloated condition.

The partly-traveled Briton seems, at first acquaintance,

full and swollen with knowledge; but should[46]

the student of learning apply the prick, the result obtained

will generally prove to be—gas.

Over our great country, some of the family of

Muggs meet one at every turn. Often they scurry

along solitarily, but occasionally in groups. In the

former case they are unsocial to every body—in the

latter to every body except their own party. The

bliss which comes from ignorance must be of a thoroughly

enjoyable nature, for the Muggses certainly

do enjoy themselves. They will pass through a country,

remaining completely uncommunicative and self-wrapped,

and know less of it after six months' traveling

than an American in two. The professor says he has

met them in the lonely parks of the Rocky Mountains

and in the fishing and hunting solitudes of the

Canadas. If they have been an unusually long time

without seeing a human being, they may possibly

catch at an eye-glass and fling themselves abruptly

into a few remarks. But it is in a tone which says,

plainer than words, "No use in your going any

further, man; I have absorbed all the beauties and

knowledge of this locality."

ONE OF THE MUGGSES.

It is a rare treat to see a coach delivered of Muggs

at a country inn. "Hi, porter, look hout for my luggage,

you know. Tell the publican some chops, rare,

and lively now, and a mug of hale, and, if I can 'ave

it, a room to myself." If the latter request is

granted, and you are inquisitive enough to take a

peep, you may see Muggs sturdily surveying himself

in the glass, and giving certain satisfied pats to his

cravat and waistcoat, as if to satisfy them that they

covered a Briton. Could the mirror which reflects[49]

his face also reflect his thoughts, they would read

about as follows: "Muggs, you are a Briton, and this

hotel must be made aware of the fact. Whatever

you do, be guilty of no un-English act while in this

outlandish land. Your skin is now full of knowledge,

and let not other travelers, like so many mosquitoes,

suck it from you. Your forefathers blessed

their eyes and dropped their h's, and so must you."

And perhaps by this time, if the chops have arrived,

he dines in seclusion and, by so doing, loses a fund of

information which his fellow-travelers have obtained

by common exchange.

Again on the way, Muggs nestles in a corner of

the coach and acts strictly on the defensive, indignantly

withdrawing his square-toed, thick-soled English

shoes, should neighboring feet attempt to hobnob

with them. On a trip through Buffalo Land,

however, it is difficult for one of her Britannic Majesty's

subjects to maintain the national dignity. But

this fact Genuine Muggs—our Muggs—evidently did

not know. Had he known it, he would never have

gone with us in the world.

Another of our party rejoiced in the appellation of

"Colon." He obtained this title because his eccentric

specialities of character several times came very

near putting if not a full stop, at least the next thing

to it, upon the particular page of history which our

party was making. Longitudinally, Mr. Colon was

all of five feet eleven; in circumference, perhaps a

score or so of inches. He possessed a fair share of

oddities, and what is better an equally fair one of dollars.

The hemispheres of his philanthropic brain[50]

seemed equally pre-empted by philosophy and bugs.

Engaging in some immense work for the amelioration

of mankind, he would pursue it with ardor, dwell

upon it with unction, and then suddenly leave it, half

finished, to capture a rare spider. Philosophy and

Entomology had constant combat for Colon, and victory

tarried with neither long enough for the seat

of war to be cultivated and blossom with any luxuriance.

At the time he joined our party one of his

grandest charitable projects had lately died in a very

early period of infancy, entirely supplanted in his

affections for the time being by the prospect of a

chase after Brazilian insects. During our journey it

was no uncommon thing for us to see his thin form

all covered with bugs and reptiles, which had crawled

out of the collecting boxes carried in his pockets.

If this meets our friend's eye, let him bear no malice,

but reflect, in the language of his own invariable

answer to our remonstrances, "It can't be helped."

Should the public parade of his faults be disagreeable,

he can suffer no more from them now than we did

in the past, and may perhaps call them into closer

quarters for the future.

Mr. Colon's son, of two years less than a score, we

dubbed Semi-colon, as being a smaller edition, or to

be exact, precisely one-half of what the senior Colon

was. So perfect was the concord of the two that the

junior had fallen into a chronic and to us amusing

habit of answering "Ditto" to the senior's expressions

of opinion. Divide the father's conversation by two,

add an assent to every thing, and the result, socially

considered, would be the son. It may readily be seen,[51]

therefore, why the professor for short should call him,

as he nearly always did, "Semi."

Shamus Dobeen, our cook and body-servant, according

to his own account, was the child of an impoverished

but noble Irish family. Indeed, we doubt if

any Irishman was ever promoted from shovel laborer

to body-servant without suddenly remembering that

he was "descinded" from a line of kings. At the

time Shamus was added to the population of Ireland,

the patrimonial estate had dwindled down to a peat

bog. As this soon "petered out," Shamus went

from the exhausted moor into the cold world. He

had been by turns expelled patriot, dirt disturber on

new railroads, gunner on a Confederate cruiser, and

high private in a Union regiment. The position of

gunner he lost by touching off a piece before the

muzzle had been run out, in consequence of which

part of the vessel's side went off suddenly with the

gun. Captured, he readily became a Union soldier,

and could, without doubt, have transformed himself

into a Cheyenne, or a Patagonian, had occasion for

either ever required.

While in Topeka, our party made the acquaintance

of Tenacious Gripe, a well-known Kansas politician,

and who attached himself to us for the trip. Every

person in the State knew him, had known him in

territorial times, and would know him until either

the State or he ceased to be.

Flung headlong from somewhere into Kansas during

the "border ruffian" period, he would probably

have passed as rapidly out of it had he been allowed

to do so peaceably. But as the slavery party endeavored[52]

to push him, he concluded to stick. At

that particular time, he was a moderate Democrat or

conservative Republican, and consequently had no

particular principles. But the slavery party supposed

he had, and to them accordingly he became

an object of suspicion. They assumed the aggressive,

and he at once resolved into a staunch Republican.

Had the latter first struck him, he would

have been as staunch a Democrat. And Gripe has

never known how near he came to being the latter.

The Republicans had just decided to order him out

of the state as a border ruffian spy, when the Democrats

took action and did so for his not being one.

Those were troublous times. He went to the front

at once in the antislavery ranks, and has stayed there

ever since. Sore-headed men are apt to become

famous. There were those in our late war who were

kicked by adversity into the very arms of Fame.

Our friend had been in both the upper and lower

houses of the State Legislature, and had rolled Congressional

logs, moreover, until he was hardly happy

without having his hands on one.

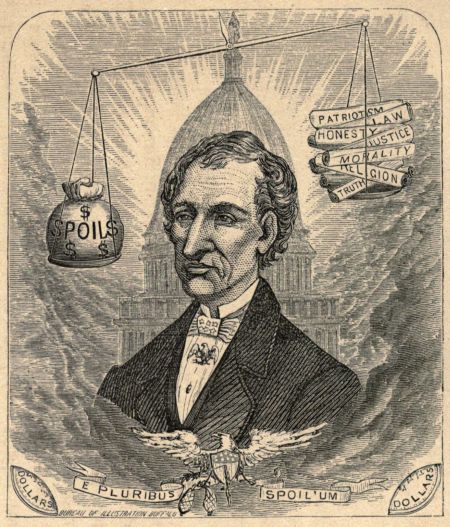

SHAMUS DOBEEN—HIS CARD.

HON. T. GRIPE (BEATIFIED).

[55]

CHAPTER III.

THE TOPEKA AUCTIONEER—MUGGS GETS A BARGAIN—CYNOCEPHALUS—INDIAN SUMMER

IN KANSAS—HUNTING PRAIRIE CHICKENS—OUR FIRST DAY'S SPORT.

We had three or four days to spend in Topeka,

as it was there that we were to purchase our

outfit for the buffalo region. With the latter purpose

in view, we were wandering along Kansas Avenue

the next morning, when a horseman came furiously

down the street, shouting, at the top of his

lungs, "Sell um as he wars har!" Semi hastily retreated

behind Mr. Colon, thinking it might be a

Jayhawker, while the professor adjusted his glasses.

Muggs said the individual reminded him of the

famous charge at Balaklava. Muggs had never seen

Balaklava, but other Englishmen had, which answered

the same purpose.

The equestrian proved to be a well-known auctioneer

of Topeka, who may be discovered at almost

any time tearing through the streets on some spavined

or bow-legged old cob, auctioneering it off as he goes.

His favorite expression is, "I'll sell um as he wars

har." What particular selling charm lies concealed

in this announcement even Gripe could not tell.

Sachem thought that possibly he had been brought

up at some exposed frontier post, where, on account

of Indian prejudices, wearing hair is a rare luxury.[56]

To say there that a man was still able to comb his

own scalp-lock denoted an extraordinary state of

physical perfection. Expressions of praise for humans

are often applied to horses, and so, perhaps,

the one in question. "I have heard," quoth our

alderman, in support of this assertion, "Fitz say of

a belle, at a charity ball, what a 'bootiful cweature;'

and I have heard him, the day after, in his stable,

say the same thing of his horse."

That horse-auction was a sight worth seeing. The

crowd collected most thickly on the corner of Kansas

Avenue and Sixth Street, and before it the cob came

to a stand. And it was a stand—as stiff and painful

as that of a retired veteran put on dress parade.

The limbs would have had full duty to perform in

supporting the carcass alone, which had evidently

been in light marching order for years past. The

additional weight of the auctioneer must certainly

have proved altogether too much, had not the

horse heard, for the first time, of the wonderful

qualities with which he was still endowed.

Seeing a whole corner, with gaping mouths, swallowing

the statement that he was only six years old,

reduced by hard work, and could, after three months

grass, pull a ton of coal, he would have been a thankless

horse indeed, which could not strain a point, or

all his points, for such a rider.

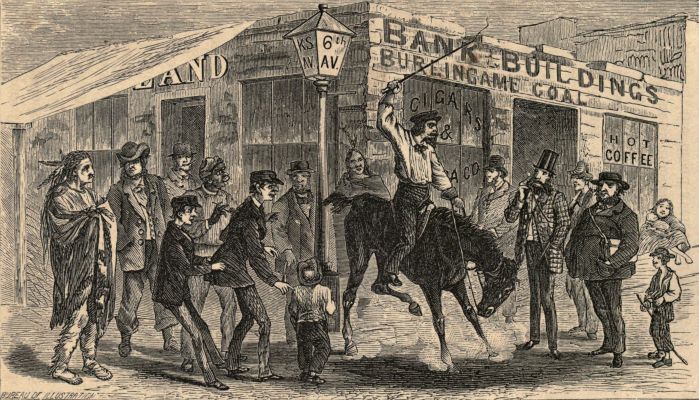

"SPERIT, GENTLEMEN!"

And so, when the spurs suddenly rattled against

his ribs, the old skin full of bones gave a snort of

pain, which the auctioneer called "Sperit, gentlemen!"

and away up the broad avenue he rolled, at a speed

which threatened to break the rider's neck, and his[59]

own legs as well. His tail having been cut short in

youth, and retrimmed in old age, the outfit made but

a sorry figure going up the street. The Professor

said it suggested the idea of some fossil vertabra, with

a paint brush attached to its end, running away with

a geological student.

After the return and cries for more bids, Muggs

must have winked at the auctioneer—possibly, to

slyly telegraph him the fact that in "Hengland"

they were up to such games. At least the auctioneer

so declared, and advancing the price one dollar in

accordance therewith, finally knocked the brute down

to him. Then the British wrath bubbled and boiled.

The auctioneer was inexorable. Muggs had winked,

and that was an advanced bid, according to commercial

custom the land over. Articles were often

sold simply by the vibration of an eyelash, and not

a word uttered.

The Professor remarked that in law winks would

doubtless be accepted as evidence. It was a recognized

principle of the statutes that he who winked at

a matter acquiesced in it, and indeed such signals

were often more expressive than words. Sachem

sustained this point, and added further that he had

known many a man's head broken on account of an

injudicious wink.

The crowd, with almost unanimous voice, pronounced

the auctioneer right and Muggs wrong.

"Me take the brute!" exclaimed the indignant

Briton; "why he can 'ardly stand up long enough to

be knocked down. Except in France, he could be

put to no earthly use whatever. 'Is knees knock together[60]

in an ague quartette, and 'is tail—look at it!

It's hincapable of knocking a fly off; looks more like

flying off hitself!" Muggs further declared the sale

was an attempt on the owner's part to evade the

health officer, who would have been around, in a

couple of days, to have the carcass removed.

The auctioneer waxed belligerent, the crowd noisy,

and Muggs, like a true Englishman, secured peace

at the price of British gold. The horse was on his

hands, having barely escaped being on the town,

and an enthusiastic crowd of urchins escorted the

purchase to a livery stable. Muggs christened the

animal Cynocephalus, and soon afterward sold him to

Mr. Colon, who was of an economical turn, for the

use of his son Semi.

"I have heard," said the thoughtful father, "that

the buffalo grass of the plains is very nourishing.

All that the poor steed needs is care and fat pastures.

Semi can give him the former, and over the latter

our future journey lies. I have also learned that

what is especially needed in a hunting horse is

steadiness, and this quality the animal certainly

possesses."

From some months' acquaintance with the purchase,

we can say that Cynocephalus was steady to a

remarkable degree. We are firmly persuaded that a

heavy battery might have fired a salute over his back

without moving him, unless, possibly, the concussion

knocked him down.

Our first hunting morning, the second day preceding

our hegira westward, came to us with a clear

sky, the sun shedding a mellow warmth, and the air[61]

full of those exhilarating qualities which our lungs

afterward drank in so freely on the plains. Indian

summer, delightful anywhere, is especially so in

Kansas.

From the advance guard of the winter king not a

single chilling zephyr steals forward among the tarrying

ones of summer. Soothing and gentle as when

laden with spicy fragrance south, they here shower

the whole land with sunbeams. Earth no longer

seems a heavy, inert mass, but floats in that smoky,

fleecy atmosphere with which artists delight so much

to wrap their angels. It is as if the warmer, lighter

clouds of sunny weather were nestling close to earth,

frightened from the skies, like a flock of white swans,

at the October howls of winter. But I never could

agree with those writers who call this season dreamy.

If such it be, it is surely a dream of motion. All nature

appears quickened. The inhabitants of the air

have commenced their southern pilgrimage, and the

oldest and leading ganders may be heard croaking,

day-time and night-time, to their wedge-shaped flocks

their narrative of summer experiences at the Arctic

circle, and their commands for the present journey.

Sachem, I find, has recorded as a discovery in natural

history that geese form their flocks in wedge

shape that they may easier "make a split" for the

south when Nature, with her north pole, stirs up

their feeding and breeding-grounds in November

gales, and changes their fields of operation into fields

of ice. Sachem was sadly addicted to slang phrases.

All game, I may remark, is wilder at this season

of the year than earlier. If the earth is dreaming,[62]

its wild inhabitants certainly are not. Men, too, have

thrown off the summer lethargy, and shave their

neighbors as closely as ever. If any one thinks it a

dreamy season of the year, let him test the matter

practically by being a day or two behindhand with a

payment.

In reply to a question, the professor told us that

the smoky condition of the atmosphere was probably

caused by the exhalation of phosphorus from decaying

vegetation. Sachem remarked that out of twenty

different objects which he had submitted for examination,

and as many questions that he had asked,

nine-tenths of the results contained phosphorus in

some shape. It was becoming monotonous and dangerous.

While the party thus mused and speculated, we had

come out into the open country, south-west of town,

and were now approaching Webster's Mound, a cone-shaped

hill from which we afterward obtained some

excellent views. For the trip we had been supplied

with two dogs, one a setter, belonging to the private

secretary of the Governor, and the other a pointer,

the property of a real estate dealer. The former was

an ancient and venerable animal. The rheumatism

was seized of his backbone and held high revel upon

the juices which should have lubricated the joints.

Even his tail wagged with a jerk, inclining the body

to whichever side it had last swung. He was so full

of rheumatism that whenever he scented a chicken

the pain evoked by the excitement caused him to

howl with anguish. The pointer, per contra, was

hale and swift, but had lost one eye; and a shot from[63]

the same charge which destroyed that organ, rattled

also on his left ear-drum, and that membrane no

longer responded to the shouts of the hunter. On

one side he could see, and not hear—on the other,

hear, but not see. Nevertheless, with gestures for

the left view, and shouts on the right, fair work

might still be obtained. Both dogs rejoiced in the

uncommon name of Rover, and both possessed that

most excellent of all points in such animals, a steady

point.

If any of my readers are fond of field-sports, and

have not yet shot prairie-chickens over a dog, let

them take their guns and hie to the West, and taste

for themselves of this rare sport. With the wide

prairie around him, keeping the bird in full view during

its passage through the air, one can choose his

distance for firing and witness the full effect of his

shot. I think the brief instant when the flight of the

bird is checked and it drops head-foremost to earth, is

the sweetest moment of all to the hunter.

[64]

CHAPTER IV.

CHICKEN-SHOOTING CONTINUED—A SCIENTIFIC PARTY TAKE THE BIRDS ON THE

WING—EVILS OF FAST FIRING—AN OLD-FASHIONED "SLOW SHOT"—THE

HABITS OF THE PRAIRIE-CHICKEN—ITS PROSPECTIVE EXTINCTION—MODE OF

HUNTING IT—THE GOPHER SCALP LAW.

We had left the road and were now driving over

the fine prairie skirting Webster's Mound, the

grass being about a foot high and affording excellent

cover. Taking advantage of its being matted so

closely from the early frosts, the old cocks hid under

the thick tufts and called for close work on the part

of our dogs.

Back and forth across our path these intelligent

animals ranged, the one fifty yards or so to our right,

the other as many to our left, crossing and re-crossing,

with open mouths drinking in eagerly the tainted

breeze. This latter was in our favor, and both dogs

suddenly joined company and worked up into it, with

outstretched noses pointing to game that was evidently

close ahead.

The pointer crawled cautiously, like a tiger, his

spotted belly sweeping the earth, and his tail, which

had been lashing rapidly an instant before, gradually

stiffening. He would open his mouth suddenly,

drink in a quick, deep draught of air, and, closing

the jaws again, hold it until obliged to take another[65]

respiration. He seemed as loath to let the scent of

the chicken pass from his nostrils as a hungry newsboy

is to quit the savory precincts of Delmonico's

kitchen window. The setter's old bones appeared to

renew their youth under the excitement, and he was

as active as a retired war-horse suddenly plunged

into battle.

Both dogs came simultaneously to a point—tails

curved up and rigid, each body motionless as if cut

in marble and one forepaw lifted. No wonder so

many men are wild with a passion for hunting. Kind

Providence smiles upon the legitimate sport from

conception to close, and gives us a posé to start with

fascinating to any lover of the beautiful, whether

hunter or not. But one must not pause to moralize

while dogs are on the point, or he will have more

philosophy than chickens.

All the party had got safely to ground and were

behind the dogs, with guns ready and eyes eagerly

fastened on the thick grass which concealed its treasure

as completely as if it had been a thousand miles

below its roots, or on the opposite side of this mundane

sphere in China. Not a thing was visible within

fifty yards of our noses save two dogs standing motionless,

with stiffened tails and eyes fixed on, and

nozzles pointed toward, a spot in the sea of brown,

withered grass, not ten feet away.

The Professor took out his lens, Mr. Colon let

down the hammers of his gun and cocked them again,

to be sure all was right, while Sachem wore a puzzled

expression as if undecided whether the attitude of

the dogs indicated any thing particular or not. The[66]

grass nodded and rustled in the light wind, but

not a blade moved to indicate the presence of any

living thing beneath it, while the dogs remained as

if petrified.

The Professor said it was very remarkable, and

wondered what had better be done next. Mr. Colon

thought that the dogs were tired, and we might as

well get into the wagon. Another suggested at random

that we should set the dogs on, and Muggs,

who had probably heard the expression somewhere,

cried, "Hi, boys, on bloods!" At the words the

dogs made a few quick steps forward, and on the

instant the grass seemed alive with feathered forms,

popping into air like bobs in shuttlecock. Such a

fluttering and flying I have never seen since, when

a boy, I ventured into a dove cote, and was knocked

over by the rush of the alarmed inmates. From under

our very feet, almost brushing our faces, the

beautiful pinnated grouse of the prairies left their

cover, and us also.

Every gun had gone off on the instant, and we

doubt if one was raised an inch higher than it happened

to be when the covey started. The Professor

afterward extracted some stray shot from the legs of

his boots, and the setter, which was next to Muggs, gave

a cry of pain for which there was evidently other

cause than rheumatism, as was demonstrated by his

retirement to the rear, from which he refused to

budge until we all got into the wagon, and to which

he invariably retreated whenever we got out.

OUR FIRST BIRD-SHOOTING.

From the midst of the birds which were soaring

away, one was seen to rise suddenly a few feet above[69]

his comrades, and then fall straight as a plummet,

and head first, to earth. It had caught some stray

shot from the bombardment—Muggs claimed from

his gun, but this statement the setter, could he have

spoken, would certainly have disputed.

Semi-Colon brought in the game, which proved to

be a fine male, with whiskers and full plumage, which

must have made sad havoc among the hearts of the

hens, when the old fellow was on annual dress parade

in the spring. At that season of the year the

cocks seek some knoll of the prairie, where the grass

has been burnt or cut off, and strut up and down with

ruffled feathers, uttering meanwhile a booming sound,

which can be heard in a clear morning for miles.

The flabby pink skin that at other seasons hangs in

loose folds on his neck is then distended like a bagpipe,

and he is a very different bird from the same

individual in his Quaker gray and respectable summer

and fall habits.

Ensconced again in the wagon, our party moved

forward, the dogs, as before, examining the prairie.

The professor was comparing the birds of the present

and the past ages, when Muggs suddenly blasted his

eyes and declared the beasts were at it again. And

so they were, the setter making a good stand at some

game in the grass, and the other dog, a short distance

off, pointing his companion. During the remainder

of the day we found many large flocks of birds, and

fired away until two or three swelled noses testified

how dirty our guns were.

"Fast shooting," said the professor, as we were on

our way home, "is as bad as that too slow. Although[70]

I am no sportsman from practice, I love and

have studied the principles of it. In my father's day

the rule was, when a bird rose, for a hunter to take

out his snuff-box, take snuff, replace the box, aim, and

fire. You may find the advice yet in some works.

The shot then has distance in which to spread. With

close shooting they are all together, and you might as

well fire a bullet. When you have given the bird

time, act quickly. The first sight is the best.

Again, the first moment of flight, with most birds, is

very irregular, as it is upward, instead of from you."

Dobeen begged leave to inform our "honors" that

in Ireland, after a bird rose, the rule was, instead of

taking snuff, to take off the boots before firing. The

professor thought that such a habit related to outrunning

the gamekeeper, and was intended to procure

distance for the poacher rather than the bird.

Sachem stated that he had known a slow hunter

once. He was a revolutionary veteran, used a revolutionary

musket, and believed in revolutionary powder.

He refused to do any thing different from what

his fathers did, and abhorred double-barreled shotguns

and percussion-caps as inventions of the devil.

It was constantly, "General Washington did this,"

and "Our army did that," and his old head shook

sadly at the innovations Young America was making.

His ghost, with the revolutionary musket on its

shoulder, had since been known to chase hunters,

with breech-loaders, who were caught on his favorite

ground after dark. "Old 1776" was great on wing-shooting,

and could be seen at almost any time hobbling

over the moor, firing away at snipe and water-fowl.[71]

He was one of those slow, deliberate cases, always

taking snuff after the bird rose. There would

be a glitter of fluttering wings as the game shot into

air. Down would come the long musket, out would

come the snuff-box, and the old soldier would go

through the present, make ready, take snuff, take

aim, and fire, all as coolly as if on parade. The old

musket often hung fire from five to ten seconds, and

the premonitory flash could be seen as the shaky

flint clattered down on the pan. The veteran always

patiently covered the bird until the charge got out.

The recoil was tremendous, and the old man often

went down before the bird; but such positions, he asserted,

were taken voluntarily, as ones of rest. Some

said that the gun had been known to kick him again

after he was down.

Sachem's narration was here cut short by the dogs

again pointing. This was followed by the usual bombardment,

which over, the bag showed the magnificent

aggregate of two chickens for the entire

day's sport.

The prairie-chicken is now extinct in many of the

Western States where it was once well known.

Usually, during the first few years of settlement, it

increases rapidly, and is often a nuisance to pioneer

farmers. Perhaps, when the latter first settle in a

country, a few covies may be seen; under the favorable

influences of wheat and corn-fields, the dozens increase

to thousands and cover the land. But with

denser settlement come more guns, and, what is a far

more destructive agent, trained dogs also. Under

the first order of things, the farmer, with his musket,[72]

might kill enough for the home table. With double-barreled

gun and keen-scented pointer, the sportsman

and pot-hunter think nothing of fifty or sixty birds

for a day's work. It seems almost impossible, under

such a combination, for a covey to escape total annihilation.

We may suppose a couple of fair shots hunting

over a dog in August, when the chickens lie close,

and the year's broods are in their most delicate condition

for the table. The pointer makes a stand before

a fine covey hidden in the thick grass before him.

The ready guns ask no delay, and, at the word, he

flushes the chickens immediately under his nose.

Each hunter takes those which rise before him, or on

his side, and if four or less left cover at the first

alarm, that number of gray-speckled forms the next

moment are down in the grass, not to leave it again.

If more rose, they are "marked," which means that

their place of alighting is carefully noted, and, as the

chicken has but a short flight, this task is easy.

Meanwhile, the guns have been reloaded, the dog

flushes others of the hiding birds, and so the sport

goes on. The birds that get away are "marked

down," and again found and flushed by the dog.

Without this useful animal the chickens would multiply,

despite any number of hunters. I have often

seen covies go down in the grass but a few hundred

yards away, yet have tramped through the spot dozens

of times without raising a single bird. In

twenty years this delicious game will probably be as

much a thing of the past as is the Dodo of the Isle

de France. At the period of our visit they were[73]

already gathering into their fall flocks, which sometimes

number a hundred or more. In these they

remain until St. Valentine recommends a separation.

During the colder weather of winter they seek the

protection of the timber, and may be seen of mornings

on the trees and fences. They never roost there,

however, but pass the night hidden in the adjacent

grass.

The prairie-chicken's admirers are numerous, other

animals beside man being willing to dine on its plump

breast. We had an illustration of this in our first

day's shooting. Sometimes when we fired, the report

would attract to our vicinity wandering hawks, and

we found that either instinct or previous experience

teaches these fierce hunters of the air that in the

vicinity of their fellow-hunter, man, wounded birds

may be found. One wounded chicken, which fell

near us, was seized by a hawk immediately.

As we passed one or two fields, indications of

gophers appeared, their small mounds of earth covering

the ground. In some counties these animals

formerly destroyed crops to such an extent that the

celebrated "Gopher Act" was passed. This gave a

bounty of two dollars for each scalp, and under it

many farms yielded more to the acre than ever before

or since. One of these animals which we secured resembled

in size and shape the Norway rat, and, in the

softness and color of its coat, was not unlike a mole.

The oddest thing was its earth-pouches—two open

sacks, one on either side of its head, and capable of

containing each a tablespoonful or more. These the

gopher employs, in his subterranean researches, for[74]

the same purpose that his enemy, man, does a wheelbarrow.

Packing them with dirt, the little fellow

trudges gayly to the surface, and there cleverly

dumps his load.

We reached town again, well pleased with our

day's ride, and over our evening pipes discussed the

results. Muggs thought our shot were too small.

Sachem thought the birds were.

Colon was delighted with the new State, but believed

that wing-shooting was not his forte. He

would be more apt to hit a bird on the wing if he

could only catch it roosting somewhere.

Gripe, at the other end of the room, was piling Republican

doctrines upon a bearded Democratic heathen

from the Western border.

[75]

CHAPTER V.