The Project Gutenberg eBook of An Experimental Translocation of the Eastern Timber Wolf

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: An Experimental Translocation of the Eastern Timber Wolf

Author: Thomas F. Weise

Richard A. Hook

L. David Mech

William Laughlin Robinson

Release date: January 19, 2011 [eBook #35006]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Leonard Johnson

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN EXPERIMENTAL TRANSLOCATION OF THE EASTERN TIMBER WOLF ***

FOREWORD

The Fish and Wildlife Service is proud to present this bulletin describing an experimental

attempt to re-establish an endangered species in part of its native range. Two

States, a Federal agency, a university, and two private conservation groups pooled

their resources to make the project possible. This effort exemplifies the type of

cooperation the Department of the Interior believes is imperative in beginning the

gigantic task of trying to save and restore the threatened and endangered animals

in this country today.

Our pride is bittersweet, however. The experiment was a complete success in

providing the information sought: What might happen when a pack of wolves is

transplanted to a new area where the native population has been all but exterminated

by Man? It was the answer to this question that was disappointing. Nevertheless,

experiments are for learning, no matter what the answers may be. We are

convinced that the answers provided by this project will ultimately be most helpful

in future attempts to restore endangered animals to parts of their native ranges where

they can begin again on the road to recovery.

DIRECTOR

U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Additional Copies Available from

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

REGION 3

Federal Building

Fort Snelling

Twin Cities, Minnesota 55111

AN EXPERIMENTAL TRANSLOCATION OF

THE EASTERN TIMBER WOLF

| THOMAS F. WEISE Department of Biology Northern Michigan University[1] | WILLIAM L. ROBINSON Department of Biology Northern Michigan University |

| RICHARD A. HOOK Department of Biology Northern Michigan University | L. DAVID MECH Endangered Wildlife Research Program U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service[2] |

[1] Marquette, Michigan 49855

[2] Division of Cooperative Research, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Md. 20810. Mailing address:

North Central Forest Experiment Station, Folwell Ave., St. Paul, MN. 55101.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| FOREWORD | Inside front cover | ||

| ABSTRACT | Back side of title page | ||

| INTRODUCTION | 1 | ||

| THE STUDY AREA | 2 | ||

| METHODS | 4 | ||

| RESULTS | 8 | ||

| Social Structure of the Translocated Wolves | 8 | ||

| Aerial Tracking | 10 | ||

| Movements of the Translocated Wolves | 11 | ||

| Post-Release Phase | 11 | ||

| Directional Movement Phase | 11 | ||

| Exploratory Phase | 11 | ||

| Settled Phase | 11 | ||

| Movements of the Remaining Pack Member | 11 | ||

| Movements of Wolf No. 10 | 12 | ||

| Feeding Habits | 16 | ||

| Citizen Sightings | 17 | ||

| Habitat Use | 19 | ||

| Failure of Female No. 11 to Whelp | 19 | ||

| Demise of the Translocated Wolves | 19 | ||

| DISCUSSION | 21 | ||

| Effect of Captivity and Human Contact | 21 | ||

| Movements | 22 | ||

| Environmental Influences | 22 | ||

| Possible Homing Tendencies | 22 | ||

| Distances Traveled | 23 | ||

| Home Range Size | 25 | ||

| Selection of a Territory | 25 | ||

| Vulnerability and Mortality | 25 | ||

| Food Habits and Predation | 26 | ||

| An Alternate Approach | 26 | ||

| CONCLUSIONS | 26 | ||

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | 27 | ||

| LITERATURE CITED | 27 | ||

ABSTRACT

Two male and two female eastern timber wolves

(Canis lupus lycaon), live-trapped in Minnesota

were released in March 1974 near Huron Mountain

in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Their movements

were monitored by aerial radio-telemetry.

The wolves separated into a group of three and a

single animal after release. The single, a young female,

remained in the release region in an area of 346

square miles (896 km²). The pack of three moved

generally westward for 13 days and then explored a

1,631 square-mile (4,224 km²) region but settled

after 2 months in a 246 square-mile (637 km²)

area about 55 miles (88 km) southwest of the release

site. The adult female, which mated while captive

prior to release, failed to whelp.

In early July, one male was killed by an automobile,

and the other was shot. The remaining female

from the pack then began to move over a much larger

area again. On September 20th she was trapped by

a coyote (Canis latrans) trapper and shot. Two

months later the single female was killed by a deer

(Odocoileus virginianus) hunter.

These results indicated that wolves can be transplanted

to a new region, although they may not settle

in the release area itself. The displacement of the

translocated wolves in this experiment apparently

caused an initial increase in their daily movements,

and probably increased their vulnerability, at least

during the first 2 months after release. The two females

examined post-mortem were in good physical

condition indicating that food supplies were adequate

in Michigan.

Human-caused mortality was responsible for the

failure of the wolves to establish themselves. Therefore

recommendations for a more successful re-establishment

effort include a stronger public-education

campaign, removal of the coyote bounty, and

release of a greater number of wolves.

[Pg 1]

INTRODUCTION

The eastern timber wolf (Canis lupus lycaon)

originally occurred throughout the eastern United

States and Canada but is now extinct in most of the

United States. The only substantial population left

inhabits northern Minnesota (Fig. 1). The estimated

wolf population in the Superior National Forest of

northeastern Minnesota in winter 1972–73 was about

390 (Mech 1973), and a tentative population estimate

for the entire state is 500 to 1,000 (Mech and

Rausch 1975). A well known population of about 15

to 30 wolves is also found in Isle Royale National

Park, Lake Superior, Michigan (Mech 1966; Wolfe

and Allen 1973; Peterson 1974).

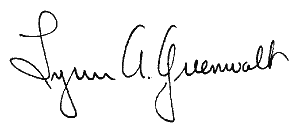

Fig. 1—Original and present range of the Easter Timber Wolf

In the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Hendrickson

et al. (1975) estimated the wolf population in 1973

at 6 to 10 animals, existing in three scattered areas:

Iron County, Northern Marquette County, and Chippewa

and Mackinac Counties (Fig. 2). Lone wolves

made up 90 per cent of verified wolf observations

there in recent years, and no more than two animals

have been found together in at least the past 13 years.

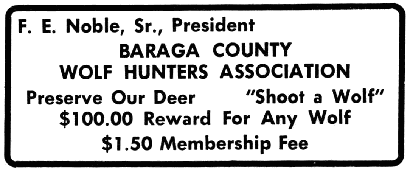

Hendrickson et al. (1975) postulated that the

current low wolf population is maintained through

possible sporadic breeding and immigration from Ontario

and Minnesota (via Wisconsin), but is suppressed

by illegal shooting and losses incidental to

coyote (Canis latrans) bounty trapping.

The eastern timber wolf was classed as an endangered

species in the conterminous United States

in 1967 under the Endangered Species Act of 1966.

There then followed widespread national and international

concern and support for preserving natural

wolf populations. Substantial scientific and ethical

arguments exist for preventing the extinction of a

species or subspecies of any plant or animal. In addition,

the presence of the wolf adds immeasurably to a

wilderness experience; its esthetic value is incalculable.

Thus in 1970, D. W. Douglass, Chief of the Wildlife

Division, Michigan Department of Natural Resources,

suggested that restoration of a viable population of

wolves in Michigan would be desirable, especially if

such efforts could be supported by private organizations.

In 1973 the Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation

and the National Audubon Society offered financial

support, and we undertook this pilot project to

obtain information necessary for a full-scale restoration

effort.

The objectives of the research project were to

determine whether (1) wild wolves could be moved

to a new location, (2) such translocated wolves

could remain in the new area, (3) they could learn

to find and procure enough food in the new area,

(4) they could tolerate and survive human activities,

and (5) they would breed and help to re-establish a

new population in Upper Michigan.

As background we had the results of three previous

attempts to transplant wolves to new areas. In 1952,

one male and three female zoo wolves were released

on Isle Royale (Mech 1966). They were attracted to

humans, became nuisances, and had to be disposed of.

Two were shot, one was captured and returned to the

mainland, and the male escaped; his fate is unknown.

The second transplant effort took place on uninhabited,

36-square-mile (92 km²) Coronation Island

in southeastern Alaska (Merriam 1964; Mech 1970).

In 1960, two male and two female, 19-month-old

captive wolves, were released there. They learned to

prey on black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus),

and multiplied to about 11 members by

1964.

In the third case, two male and three female laboratory

wolves from Barrow, Alaska were released

near Umiat in August 1972, 175 miles (282 km)

southeast of Barrow (Henshaw and Stephenson

1974). Eventually, all moved toward centers of

human habitation and three were shot within 7

months. A fourth returned to the pens where she was

reared, and was recaptured, while the fate of the fifth

wolf remains unknown. Three of the five had taken

the correct homing direction.

[Pg 2]Because results of the earlier attempts at translocating

wolves suggested that pen-reared wolves did

not fare well in the wild, we decided to use wild

wolves that were accustomed to fending for themselves

and avoiding people. They would have to be

released in the most inaccessible area we could find

and encouraged to stay there. To maximize their

chances of breeding, we would have to try to obtain

animals with already established social ties, that is,

members of the same pack. Approval was obtained

from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

to live-trap up to five wolves in Minnesota, and a

permit was granted by the Michigan Department of

Natural Resources to release up to five in Upper

Michigan.

This bulletin describes the results of the experimental

translocation.

THE STUDY AREA

The area selected for the release of the translocated

wolves was the Huron Mountain area (Fig. 2) in

northern Marquette County in the Upper Peninsula

of Michigan (47° N Latitude; 88° W Longitude).

This is one of the largest roadless tracts in Michigan,

and has one of the lowest year-around densities of

resident humans. Much of the area is owned by the

Huron Mountain Club, on which accessibility is

restricted.

Fig. 2.—Range of the wolf in Upper Michigan in 1973,

and the release point (from Hendrickson et al. 1975)

The Upper Peninsula is 16,491 square miles

(42,693 km²) in area, bounded by Lake Superior to

the north, and by Lakes Huron and Michigan to the

east and south. The Wisconsin border along the

western portion of the Upper Peninsula forms no

distinctive ecological boundary. The Upper Peninsula

is in the Canadian biotic province (Dice 1952), characterized

by a northern hardwoods climax, interspersed

with spruce-fir and pine subclimaxes. The

northwestern portion of the Upper Peninsula, including

Marquette, Baraga, Houghton, Ontonagon, and

Iron Counties, contains rugged highlands and rock

outcroppings which rise to elevations approaching

2,000 feet (610 m) in several locations.

The human population of the Upper Peninsula is

303,342, with a rural density of about 9.0 persons

per square mile or 3.5 persons per square kilometer

(Table 1). The population of the Upper Peninsula

has remained at about 300,000 for the past 50 years,

and the rural human populations of local areas have

generally declined or remained stable. During those

50 years, the wolf population has declined from several

hundred animals to near extinction, with the

population estimated by Hendrickson et al. (1975)

at 6 to 10 remaining wolves. These authors concluded

that the bounty on wolves between 1935 and 1960

was largely responsible for the demise of the species

in the Upper Peninsula. The bounty was removed in

1960, after only one wolf was taken in 1959. Legal

protection was granted by Michigan in 1965. The

Endangered Species Act of 1973 added federal protection

in 1974.

[Pg 3]

Table 1. Density of Rural Human Populations in Four Wolf Ranges

in the Great Lakes Region

| Location | Area in Square Miles (Square Kilometers) | Percent Urban[3] | Rural Population | Rural[4] Population Density Per Square Mile (Square Kilometer) |

| Ontario[5] | 412,582 | 3.3 | ||

| (1,068,125) | 80.4 | 1,364,33 | (1.27) | |

Northern[6] Minnesota | 12,627 | 6.4 | ||

| (32,690) | 68.0 | 81,246 | (2.5) | |

| Upper Michigan[7] | 16,491 | 9.0 | ||

| (42,693) | 51.4 | 147,841 | (3.5) | |

| Iron and Oneida Co. [8] Wisconsin | 1,859 | 12.3 | ||

| (4,812) | 26.0 | 22,899 | (4.7) |

[3] Towns or cities of more than 2,500 people

[4] Including towns with a population less than 2,500

[5] 1966 Census, 1970–71 Canada Yearbook

[6] Cook, Koochiching, Lake and St. Louis Counties

[7] All 15 Upper Peninsula counties

[8] Last described wolf range in Wisconsin (Thompson 1952)

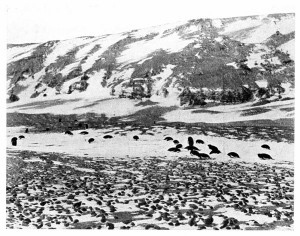

The white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus)

would be the major prey for wolves in Michigan, and

there appear to be sufficient numbers to support

wolves. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources

pellet count estimates for the spring deer population

in the Upper Peninsula in 1973 was 10 ±

21.9% deer per square mile (3.9 ± 21.9% per km²).

Deer densities of 10 to 15 per square mile (3.9 to 5.8

per km²) supported wolf densities of one wolf per 10

square miles (26 km²) in Algonquin Provincial Park,

Ontario (Pimlott 1967).

The population of deer wintering on the 14 square-mile

(36 km²) Huron Mountain deer yard in winter

1973–74 was estimated at 73.3 ± 49.5% deer per

square mile (28.3 ± 49.5% deer per km²) by the

pellet count method (Laundre 1975). Thus total wintering

population on the Huron Mountain Club, the

wolf release area, would be about 1,000 deer.

The utilization of available browse by deer in the

Huron Mountain deer yard reached 95% by March

8, 1969 and 92% by March 5, 1970 (Westover 1971).

The minimum winter deer loss (actual number

found) in 1969 was 40 animals, of which at least 12

had starved, and it was estimated that perhaps up to

33% of the deer starved in the Huron Mountain Yard

in 1968–69 (Westover 1971). The Huron Mountain

yard continues to be overbrowsed, with high deer

mortality expected in severe winters. Many other

northern deer yards of the Upper Peninsula are also

overbrowsed and are dwindling in area. Thus we

expected that numbers of vulnerable deer (Pimlott

et al. 1969; Mech and Frenzel 1971) would be available

to wolves.

Beavers (Castor canadensis) are an important food

source for wolves in many areas during summer

(Mech 1970), and they are common throughout the

Upper Peninsula. The beaver population on the 26

square-mile (67 km²) Huron Mountain Club was

estimated at 46.9, or about 1.9 beavers per square

mile (0.7 per km²) (Laundre 1975). Moose (Alces

alces) are rare on mainland Michigan.

[Pg 4]

METHODS

The general procedure for this study was to attempt

to capture an intact pack of wolves in Minnesota,

fit each animal with a radio-collar (Cochran

& Lord 1963), release them in northern Michigan,

and follow their fate through aerial and ground radio-tracking

(Kolenosky and Johnston 1967).

A pack was selected from an area near Ray, Minnesota

(Fig. 3), south of International Falls (48° N

Latitude, 93° W Longitude), where wolf hunting

and trapping were legal. Two male and two female

wolves were captured by professional trapper Robert

Himes, under contract for the project, between December

24, 1973 and January 21, 1974 (Table 2).

Three of the wolves were trapped (Fig. 4) in No. 4

or 14 steel traps (Mech 1974), and one (No. 13) was

live-snared (Nellis 1968). If these animals had not

been solicited for this study, they would have been

killed and their pelts sold, as part of the trapper's

livelihood, before the Endangered Species Act of 1973

took effect.

Fig. 3.—Capture and release points of the translocated

wolves

At capture each wolf was immobilized with a combination

of phencyclidine hydrochloride (Sernylan)

and promazine hydrochloride (Sparine) intramuscularly

(Mech 1974), with dosage recommendations

from Seal et al. (1970). They were then carried

out of the woods (Fig. 5), held in pens in Minnesota,

and fed road-killed white-tailed deer, supplemented

with beef scraps.

Fig. 4.—Wolf caught in trap (Photo by Don Breneman)

Fig. 5.—The captured wolves were drugged and

carried to an enclosure in Minnesota (USFWS

Photo by L. David Mech)

[Pg 5]

There is no certain way of ascertaining that wolves

are related or that they belong to the same pack. Thus

to maximize chances that members of the same pack

would be captured, the trapper set traps where he

suspected only one pack ranged. To try to determine

whether the individual wolves he caught were socially

related, we instructed the trapper to hold the wolves

in individual pens until we could observe their introductions

to each other. Wolves No. 10 and 11 were

placed together on January 23, 1974, and No. 13 and

14 were released into the pen with No. 10 and 11 on

February 4.

Fig. 6.—Before being transported to Michigan, each

wolf was weighed (USFWS Photo by Don Reilly)

Table 2. Background information on the translocated wolves

| Wolf Number | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| Sex | F | F | M | M |

| Estimated age[9] | 1–2 years | 6–7 years | 2–3 years | 2–3 years |

| Capture date | 12-24-73 | 1-5-74 | 1-19-74 | 1-21-74 |

| Capture Method | Trapped | Trapped | Trapped | Live-snared |

| Capture foot | Left front | Right front | Right front | |

| Capture-related damage | Two nails lost | Three nails lost | None | None |

| Weight at capture | 55 lb. | 65 lb. | 74 lb. | 75 lb. |

| (24.9 kg) | (29.4 kg) | (33.5 kg) | (33.9 kg) | |

| Weight, March 5 | 46 lb. | 58 lb. | 66 lb. | 60 lb. |

| (20.8 kg) | (26.3 kg) | (29.9 kg) | (27.2 kg) | |

| % weight loss | 16% | 11% | 11% | 20% |

| Canine length, upper | 0.83" | 0.25–0.50" | 0.93" | 0.87" |

| (21 mm) | (6–13 mm) | (24 mm) | (22 mm) | |

| Canine length, lower | 0.75" | very worn | 0.82" | 0.85" |

| (19 mm) | (21 mm) | (21 mm) | ||

| Testes[10] | —— | —— | 0.5 × 1.0" | 0.5 × 0.75" |

| (13×25 mm) | (13×19 mm) | |||

| Teats | Tiny, not apparent | Dark, evident | —— | —— |

[9] Gross subjective estimates based on tooth wear

[10] Estimated

[Pg 6]

On March 5, 1974, the wolves were again immobilized

for pre-release processing in Minnesota. An initial

dose, and several supplemental doses of phencyclidine

and promazine were administered intramuscularly

and intraperitoneally between 9:00 a.m. and

4:30 p.m. CDT. The wolves were restrained with

muzzles and their legs were bound together during

processing and transport. Two of the wolves were

blindfolded because they were too active otherwise.

The wolves were ear-tagged with both Minnesota

and Michigan Department of Natural Resources tags,

and weights and body measurements were taken (Fig.

6, 7). Their teeth were inspected and canines were

measured to try to obtain an indication of age. Each

animal was fitted with a radio transmitter (AVM

Instrument Co., Champaign, Illinois[11]) molded into

an acrylic collar (Mech, 1974).

Fig. 7.—Standard body measurements were also

taken (USFWS Photo by Don Reilly)

Each wolf was injected with 1,200,000 units of

Bicillin (Wyeth), 2 cc of distemper-hepatitus-leptospirosis

vaccine (BioCeutic Laboratories D-Vac HL),

0.5 cc of vitamins A, D, E, (Hoffman-LaRoche[11] Injacom

100), 1 cc of vitamin C-fortified vitamin B complex

(Eli-Lilly, Betalin Complex FC), and 2 cc anti

rabies vaccine (Fromms Raboid). These injections

(Fig. 8) were given to insure that the wolves would

be as healthy as possible upon release, and would not

contract or introduce diseases in the release area.

[11] Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement

by the U. S. Government.

Some 30 to 60 cc of blood were drawn from each

wolf for analysis of its physical condition (Seal et al.

1975).

The processing of the wolves took from 8:45 a.m.

to 2:00 p.m. CDT on March 5, 1974. The animals

were then transported by truck to International Falls,

loaded on an airplane (Fig. 9), and flown for 2 hours

(Fig. 10) to the Marquette County Airport, Michigan.

They were turned on different sides each half

hour while drugged during their processing and transport

to prevent lung congestion. At the Marquette

Airport they were transferred by van to a 25 foot

by 25 foot by 12 foot (7.6 m × 7.6 m × 3.7 m) holding

pen on the Huron Mountain Club property 35 miles

(56.3 km) northwest of Marquette.

Fig. 8.—Various vitamins and vaccines were administered

to each wolf to insure their health and freedom

from common canine diseases (USFWS Photo

by Don Reilly)

The wolves were released individually into the

holding pen while each was still partly under sedation

(Fig. 11). The transmitting frequency of each wolf's

collar was rechecked on the receiver as each wolf was

released into the pen (Fig. 12). All wolves were in

the pen by 10:00 p.m. EDT, and were held there

until March 12.

Four road-killed deer carcasses, provided by the

Michigan Department of Natural Resources, had

been placed inside the pen for food (Fig. 13), and a

tub of drinking water was provided. Carcasses of five

road-killed deer and a black bear (Ursus americanus)

were placed within a half-mile (0.8 km) of the

release pen as food for the wolves after their release.

We had scheduled the release for mid-March for

several reasons which we felt would maximize chances

for success. Deer are concentrated then in the Huron

Mountain area and vulnerable to predation. Pregnancy

and subsequent whelping of the alpha female

might increase her attachment to the new area. Furthermore,

the snow is usually deepest then and

hinders travel. However, a few days before the release,

a freak rainstorm had settled the snow, and cold

temperatures had frozen it so hard that animals

could walk readily on top, making travel conditions

excellent.[Pg 7]

Fig. 9.—The anesthetized wolves were placed aboard

an aircraft in International Falls, Minnesota

(USFWS Photo by Don Reilly)

Fig. 10.—The wolves were kept lightly drugged during

the flight to Michigan (USFWS Photo by L.

David Mech)

Fig. 11.—In the Huron Mountain area of Upper

Michigan the wolves were taken to another holding

pen (Photo by Don Pavloski)

Fig. 12.—Biologists checked the signal from each

radio-collar before the wolves were released into

the holding pen (Photo by Don Pavloski)

An observation shack 120 feet (36.6 m) from the

pen was used to determine the activities and interactions

of the four wolves. Weise spent three nights

in the shack and also observed the wolves each day

of the one-week penned period, for a total of 20

hours of observation (Fig. 14).

During preliminary air and ground checks of radio

equipment, we discovered that Wolf No. 10 had a

defective collar. Thus on March 12, we subdued her

with a choker, restrained her with ropes, replaced her

collar and released her just after sunset. We then

opened the pen, and let the other wolves loose.[Pg 8]

Fig. 13.—While in captivity, the wolves were fed primarily on road-killed deer (Photo by Don Pavloski)

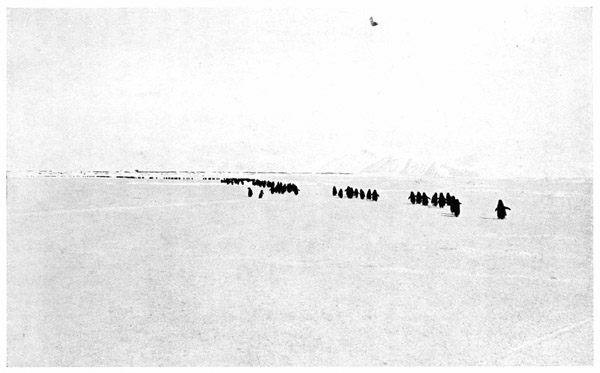

The subsequent locations of the wolves were then

checked intermittently through aerial radio-tracking

(Mech 1974), with a receiver and antenna from the

AVM Instrument Co., Champaign, Illinois, used in

a Cessna 172 and a Piper Colt. We made two flights

each day for the first 2 days after release, one each

day when weather permitted, until April 20, three

per week in May, approximately two per week from

June through September, and three per week in October

and November. A total of 194 hours were flown,

80 per cent by Weise, and the remainder by Hook.

Aerial locations were usually recorded to the nearest

40 acres (16 ha.).

We also tracked the wolves from the ground whenever

interesting or significant activities were observed

during flights or were reported by ground observers.

Carcasses of prey animals were investigated from the

ground after consumption was complete and the

wolves had left. Deer eaten by the wolves were considered

killed by them if the ground check revealed

fresh blood or flesh, or signs of a struggle. Scats were

collected along the tracks of the wolves in the snow

whenever possible.

When radio signals were received from the same

location for unusually long periods, ground checks

were made to determine the cause.

Attempts were made to verify all sightings and

track records reported by local citizens, by comparing

them with the aerially-determined locations.

RESULTS

Social Structure of the Translocated

Wolves

Wolves No. 11, 12, and 13 were captured in Minnesota

within a mile (1.6 km) of each other, and

No. 11 and 12 were taken in the same trap set 12 days

apart; Wolf No. 10 was caught approximately 7.5

miles (12.1 km) southeast of the others (Table 2).

All were judged to be thin but in good condition.

Females No. 10 and 11 were introduced into the

same pen on January 23. No. 11 was reluctant to

enter the pen containing No. 10 while several observers

were around, but entered within 15 minutes

after all but one had left. No. 11 went directly to

No. 10 which was lying in a corner as she usually did,

and pawed the fence at No. 10's back. When the

pawing became more vigorous, No. 10 snapped at No.

11, moving only her head and neck. No. 11 then

turned directly to No. 10, sniffed the top of her head

and mane, and lay down beside No. 10 with her nose

still in No. 10's mane. No. 10 remained still throughout

the whole process. The trapper reported that later

No. 11 licked the face of No. 10. Sniffing and licking

anteriorally are usually signs of intimacy between

wolves (Schenkel 1947).

[Pg 9]

The two male wolves (No. 12 and No. 13) were

allowed into the pen with the two females on February

4. No. 13 remained in the original adjoining

pen and did not move in with the females immediately,

but No. 12 did. There were no signs of aggression

among any of the four wolves. No. 11, 12, and

13 moved freely around the pen while in Minnesota,

but No. 10 most often lay in one corner by herself.

Trapper Himes first observed vaginal bleeding in

female 11 on February 7. He observed Wolves 11 and

12 mating (with normal coupling) on February 12

and 16.

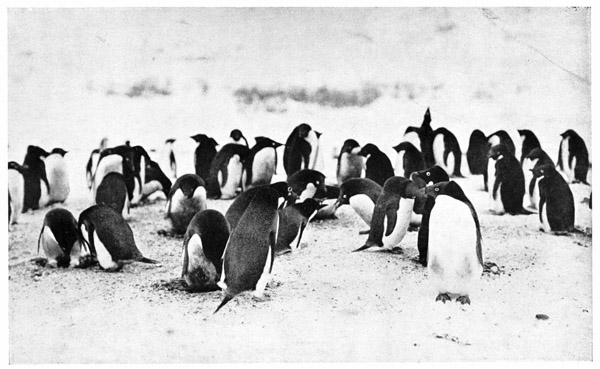

No unusual aggressive or agonistic social interactions

of consequence were observed among the wolves

while penned in Michigan, from March 5 to 12.

Animals 11, 12 and 13 would lie down and feed together

in various combinations. No. 10 was less active

than the others and often stayed inside a shelter box

within the enclosure, but would come out and mix

with the other wolves for brief periods when humans

were not in evidence. Her actions were indicative of

a low ranking, immature, distressed, or alien animal.

Male No. 12 was the only wolf that would stare

directly at a person approaching the pen. He was

bolder and more direct in his actions than any of the

other animals. This is the wolf that mated with adult

female No. 11 while penned in Minnesota, and thus

can be considered the "alpha male," or pack leader.

When approached by humans, all the wolves would

urinate and defecate; No. 11 and 12 would pace, No.

10 (when out of the shelter box) and No. 13 would

lie in the far corner of the pen and remain motionless

(Fig. 14). No. 11 limped on her right front foot

throughout the penned period, but this limp did not

appear to have a significant effect on her activities

or movements.

Blood samples taken on March 5, 1974 were analyzed

and interpreted by Dr. U. S. Seal of the Veterans

Administration Hospital in Minneapolis. The

assays performed included hematology, 16 blood

chemistries, thryoxine, and cortisol (Seal et al.,

1975), plus estrogen and progesterone. According to

Seal (personal communication), all blood values for

wolves No. 10, 12, and 13 were similar and indicative

of good health and minimal stress, as indicated by

very low levels of the enzymes LDH, CPK, and

SGOT. Such levels are typical of animals in a state

of good nutrition that have been in captivity for

several weeks and have accepted their captive circumstances.

The MCV's were normal, indicating no vitamin

deficiency, and the MCHC showed full hemoglobin

content in the red cells, indicating no lack of

iron. The white blood cell counts were much lower

than usually seen in newly trapped wolves. All the

remaining chemistry values from these three wolves

were in the normal range for the season.

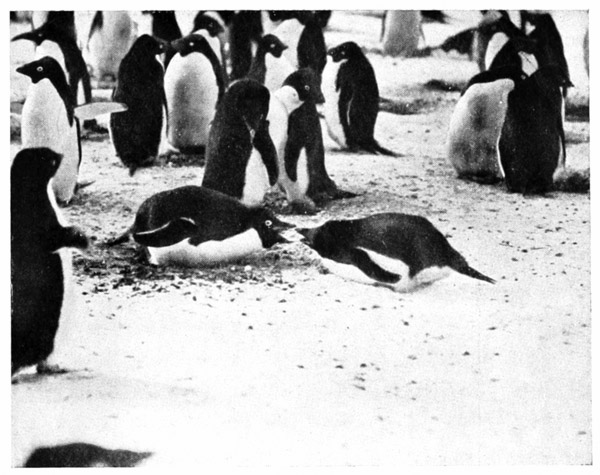

Fig. 14.—The Minnesota wolves in their Michigan pen (Photo by Tom Weise)

[Pg 10]

Wolf No. 11, however, differed in that she had a

much higher hemoglobin level, higher blood glucose

and white cell count, and higher levels of LDH, CPK,

and SGOT, indicating that she was significantly

stressed. This is corroborated by a low thyroxine level

of 0.6 micrograms percent, which is hypothyroid for

wolves.

The fibrinogen levels of all four animals were normal,

indicating that there was no acute or chronic

inflammation in progress.

The wolves ate well in captivity but still lost from

11% to 20% of their capture weight (Table 2).

Himes estimated that they consumed an average of

8 lb. (3.6 kg) of food per wolf per day, while penned

in Minnesota. In Michigan the wolves consumed

about a deer and a half, or an estimated 5.5 lb. (2.5

kg) per wolf per day. These estimates fall within the

range of food consumption figures estimated for

wolves in the wild (Mech and Frenzel 1971). After

the wolves began feeding on the first carcass, they

completely consumed it before starting a second one,

even though four carcasses were available; they ate

nothing from the other two carcasses.

We released the wolves at dusk on March 12, 1974.

Having just restrained Wolf No. 10 without drugs,

to replace her collar, we untied her and let her free;

she bounded off northwestward. We then opened the

pen, and No. 12, whom we had judged to be the

alpha male, left in less than 5 minutes and trotted off

steadily toward the west-southwest. The remaining

two animals paced around the pen for about 5 minutes

and then lay down. Because we felt that they

might become too widely separated from the others,

three of us approached the pen opposite the door to

encourage the wolves to find the open gate. Five

minutes later No. 13 left the pen running southwestward,

and No. 11 left less than 5 minutes later. Upon

exiting, No. 11 appeared to smell the track of No. 12

and slowly trotted in his direction.

Aerial Tracking

Our success in locating the translocated wolves by

aerial radio-tracking was 95% (Table 3), similar to

that of Mech and Frenzel (1971) working with

wolves in their native range in Minnesota.

During the part of the study in which extensive

snow cover was present (March 13 to April 20)

wolves No. 11, 12, and 13 were observed 14 times

from the aircraft. The first time they were seen, near

Laws Lake, they appeared alarmed and moved into

heavy cover. The next day, however, and on all subsequent

observations, the aircraft appeared to have

little effect on their behavior, although they sometimes

looked up at it. No. 10 was seen only once by a

passenger in the tracking aircraft, and she immediately

hid from view. It seems likely that she avoided

the aircraft. After the snow melted and leaves appeared,

we no longer saw the wolves.

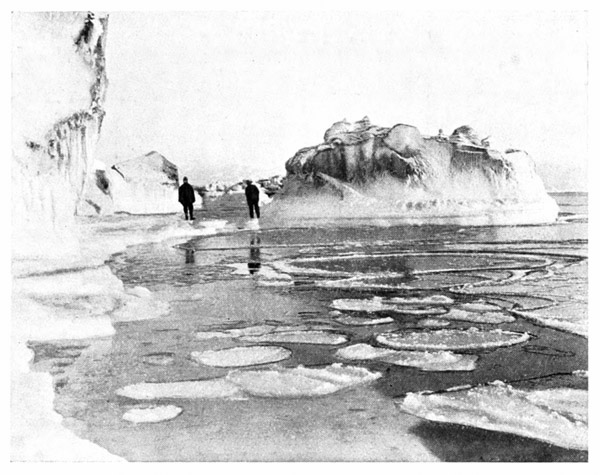

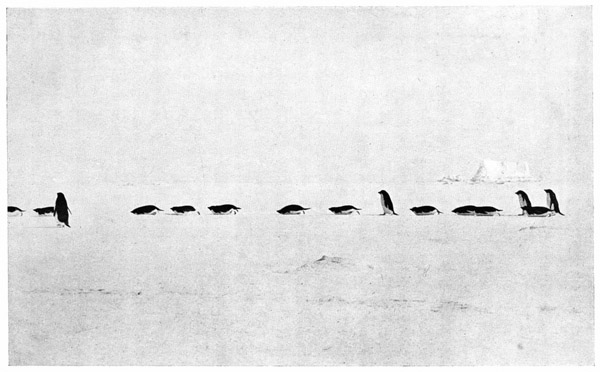

The activities of the three wolves during the 14

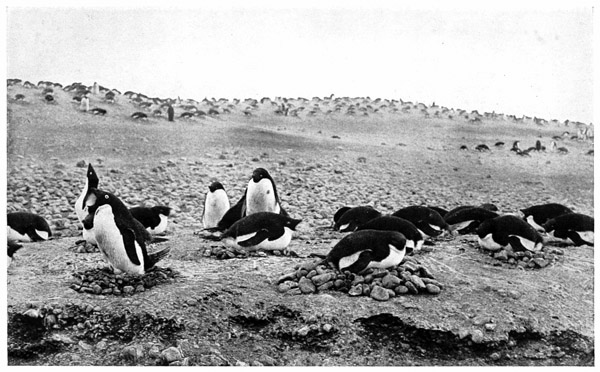

aerial observations were as follows: traveling 4 (Fig.

15), feeding and scavenging 5 (Fig. 16), resting 4,

and sleeping 1.

Table 3. Success in locating wolves by aerial tracking

| Wolf Number | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| Number of tracking attempts | 113 | 65 | 59 | 67 |

| Number of times located | 105 | 62 | 59 | 61 |

| Percent located | 93% | 95% | 100% | 91% |

| Number of times observed | 1 | 14(Pack) | ||

| Last date tracked | Nov. 17 | Sept. 19 | July 10 | July 27 |

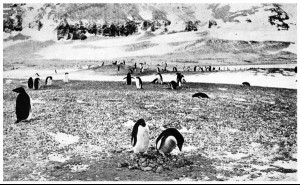

Fig. 15.—The wolves often used woods roads for

traveling (Photo by James Havemen)

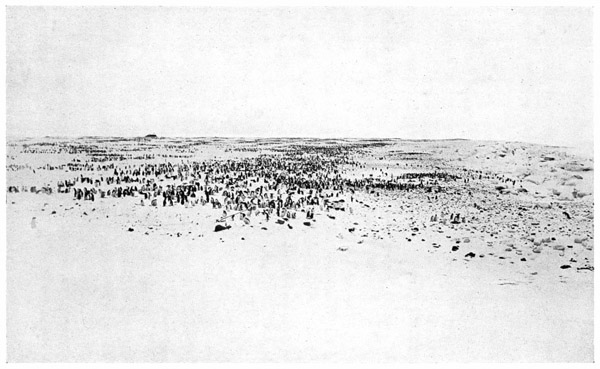

Fig. 16.—The released wolves were sometimes observed

from the aircraft feeding on deer they had

killed (Photo by Richard P. Smith)

[Pg 11]

Movements of the Translocated Wolves

Wolf No. 10 never joined any of the other radioed

wolves after their release, whereas the others generally

remained as a pack. Thus the movements of the

pack will be described separately from those of lone

wolf No. 10.

Four phases were seen in the movements of the

pack: (1) Post-Release Phase, March 12 to 14; (2)

Directional Movement Phase, March 15 to 24; (3)

Exploratory Phase, March 25 to May 7, and (4) Settled

Phase, May 7 to July 6.

Post-Release Phase

This first phase of the wolves' movements, including

the first 2 days after release, seemed to be characterized

by confusion and indecision. On March 13, the

morning after the release, the three wolves were

separated, but all remained within 2.0 miles (3.2 km)

south to west of the release site, the general direction

in which they had headed upon release (Fig. 17). No.

11 and 13 were about a half-mile (0.8 km) apart in

the morning, and by late afternoon, No. 13 apparently

had joined No. 11. No. 12 remained about 2

miles away from the others all day, although he did

move about a half-mile during the day. By the 14th,

No. 11 and 13 had moved 2 miles southwestward,

but were separated by a half-mile; No. 12 had moved

only a half-mile west.

Directional Movement Phase

During this phase, all three wolves left the immediate

vicinity of the release point and headed southwestward.

Early in this phase, wolves No. 11 and 13

rejoined (by March 15) and traveled 9 miles (14.5

km) west-southwest of their previous day's location,

while No. 12 took a more northerly route. Nevertheless,

by March 19, No. 12 had joined the other two

wolves near Skanee, some 14 miles (22.5 km) west-southwest

of the release point (Fig. 17). For the next

several weeks these wolves all remained together and

travelled a straight-line distance of about 40 miles

(64.1 km) to a point just north of Prickett Dam

about 11 miles (17.6 km) west-southwest of L'Anse,

arriving there on March 24 (Fig. 17).

Exploratory Phase

In the Exploratory Phase of their movements, from

March 25 to May 7, wolves No. 11, 12, and 13 covered

a 1,631-square-mile (4,224 km²) area from the

town of Atlantic Mine on the Keweenaw Peninsula

to the north to a point about 64 miles (103.0 km)

south, near Gibbs City (Fig. 18). In the opposite

dimension, they ranged from Keweenaw Bay on the

east to 9 miles (14.5 km) south of Ontonagon, 42

miles (67.6 km) west of there. This phase was characterized

by long movements, considerable zigzagging,

and revisiting of certain general regions such as the

base of the Keweenaw Peninsula and areas east and

north of Kenton (Fig. 18).

An interesting social change also occurred during

this phase: No. 13 split from the pack sometime after

April 26 when the pack had reached its westernmost

location, south of Ontonagon. Whereas No. 11 and

12 returned east-northeastward toward Otter Lake,

where they had been in late March, No. 13 headed

west-northwestward to the Porcupine Mountains, 18

miles (30.0 km) west of where the pack had last been

located together (Fig. 18). Thus on May 2, Wolf No.

13 was 51 miles (82.0 km) west of No. 11 and No. 12.

Nevertheless, 5 days later all the wolves were found

near Gibbs City, 62 miles (99.8 km) southwest of the

Porcupine Mountains, and 45 miles (72.4 km) south

of Otter Lake; No. 13 was only 6 miles (9.7 km) from

his packmates. The next time an attempt could be

made to locate the wolves, on May 16, they had

reunited.

Settled Phase

This last phase of the wolves' movements includes

the period when the animals had settled into an area

similar to the size of home ranges reported for other

wolves in the Great Lakes Region (Mech 1970).

From May 7 to July 6, this pack lived in a 246-square

mile (637 km²) area with its center north of Gibbs

City (Fig. 18). On July 10, wolf No. 12 was found

dead. Presumably he had died by July 6, for he had

not moved since then.

Wolf No. 13 had again split from his associates

between June 14 and 19 and begun to travel alone.

On July 20, his remains were discovered 24 miles

(38.6 km) southeast of where the pack had settled.

These deaths will be discussed in detail later.

Movements of the Remaining

Pack Member

After the death of her mate (No. 12), Wolf No. 11

left the 246-square-mile area in which the pack had

settled (Fig. 19). By July 15, she had traveled 28

miles (45.0 km) northwest of this area and by the

20th, was back by Otter Lake, 40 miles (64.4 km)

north. She returned south of Gibbs City on July 27,

and was found about 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the

Wisconsin border on August 2, near Lac Vieux

Desert about a half mile (0.8 km) north of the Wisconsin

border on August 6, and near Bruce Crossing

on August 9.

On August 13, Wolf No. 11 was located 1½ miles

(2.4 km) southeast of Ewen on the western edge of

her previous locations. She was not located again until

August 28. By then she had moved a straight-line

distance of almost 60 miles (96.5 km) to an area in[Pg 12]

Marquette County just south of Squaw Lake, in the

Witch Lake area. In doing so, she probably had

passed through the area previously explored just north

of the Iron County region where the pack had spent

so much of its time. These widespread movements

are characteristic of lone wolves even in their native

range (Mech and Frenzel 1971).

Fig. 17.—Movements during the Post-release and Directional Movement Phases of Wolves No. 11, 12, and 13

No. 11 was still in the Witch Lake area on September

2. Due to poor flying conditions we did not locate

her again until September 19. At that time she was

on the Floodwood Plains a quarter mile (0.4 km)

north of the Floodwood Lakes. She was caught in a

coyote trap during the night of September 19 and shot

about 10 a.m. on September 20.

Movements of Wolf No. 10

The movements of female wolf No. 10 during the

post-release phase were markedly different from those

of the pack. In fact, this wolf apparently skipped the

relatively sedentary post-release phase of movements

that the pack displayed, and immediately dispersed

(Fig. 20).

By the morning after release, No. 10 was 10 miles

(16.0 km) southeast of the release point and by late

afternoon was an additional 5.5 miles (8.8 km) southeast

(March 13). On the night of March 15 this wolf

crossed four-lane Highway 41, and on the 16th was

found 1¼ miles (2.0 km) south of the Marquette

County Airport, approximately 32 miles (51.5 km)

from the release site; she had traveled a minimum of

36 miles (57.9 km) to get there. However by March

20 she had returned to within 4 miles (6.4 km) of

the release point, and by the 24th was within a quarter

mile of the site.

The other three wolves had already dispersed westward

and were near Prickett Dam, some 40 miles

(64.0 km) away. It is not known whether No. 10 tried

to locate them. Her locations indicate that she did

not, although she may not have been able to find or

follow their route. From April 2 to 15, No. 10 made

a second exploration southward, again returning to

the Huron Mountain area. She also made a third such

trip on June 14 to 22, even crossing Highway 41

again.[Pg 13]

Fig. 18.—Exploratory and Settled Phases in the movements

of Wolves No. 11, 12, and 13

[Pg 14]

Fig. 19.—Movements of No. 11 after

the death of No. 12 and 13

From the time of release until the first week in

September, there seemed to be a pattern to the movements

of Wolf No. 10. She made nine trips of about

40 miles (64.0 km) each, starting near Huron Mountain,

extending southeasterly about 20 miles (32.0

km), and then returning northwesterly to the Huron

Mountain area (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20.—Movements of Wolf No. 10

During March, April, and the first week of May

Wolf No. 10 made three of these trips roughly paralleling

the Lake Superior shore, and she remained in

the Huron Mountain area for several days between

trips. From late May until mid-July she made four

such trips but did not remain long anywhere. During

that time she gradually moved westerly to near the[Pg 15]

Dead River Basin. In late July she made another trip

to the Dead River Basin area after a stay near the Big

Bay dump. These trips enlarged No. 10's range considerably.

Early in July, Wolf No. 10 moved almost directly

south from the Huron Mountain area to the Silver

Lake area, again expanding her range to the west.

From September 5 until October 10 she remained in

the Silver Lake area, and there was no apparent pattern

to her movements then. After the wolf was located

on September 15 near a bait that bear hunters

had put out on the west edge of the Mulligan Plains,

a ground check was made. No evidence of the wolf

was found at the bear bait, consisting mostly of fish,

and no signal was heard there. A signal was picked up

in the southwest corner of the Mulligan Plains, and

the wolf was flushed from her bed about 80 yards

(75 m) away.

On October 10, this wolf began a westward move,

and on October 22 she was found south of Herman,

25 miles (40.2 km) west of Silver Lake. On October

24 she was located 6.5 miles (10.4 km) to the northeast,

near Dirkman Lake. By October 26 she had

moved 12 miles (19.3 km) southeast to within a mile

of the town of Michigamme. From there she gradually

moved northeastward. She was shot near Van

Riper Lake during deer hunting season, probably on

the morning of November 16.

During the westward move, this wolf had increased

the size of her range by 87 square miles (222.7 km²),

about a 30% increase. She seemed to be heading back

to the Silver Lake area when she was killed.

[Pg 16]

Feeding Habits

What little information we could obtain on the

wolves' feeding habits indicated considerable variation

(Table 4).

In the Skanee area, which the pack of three first

visited after leaving the release area, deer were abundant,

and 7 to 10 were seen within a quarter mile

(0.4 km) of the pack on March 20. It is possible

that the wolves killed a deer there, for they remained

in the area for a few days. They did scavenge deer

feet and head remains on the 22nd at Laws Lake,

12 miles (19.3 km) southwest of Skanee. Deer were

also sighted within a quarter mile of the wolves on

March 25, April 15, April 16, May 7, June 8, and

June 14.

The first confirmed deer kill was made east of

Otter Lake about April 1. The deer was a 4½-year-old

doe with a partly healed broken left front leg

(radius) and fat-depleted bone marrow (1%); a bullet

was found in the skin of the right front leg.

The pack also fed on a discarded deer carcass near

Nisula, and then killed a 5½-year-old doe near

Kenton on April 15 (Fig. 21); this animal also had

bone marrow with a low fat content (6%).

The next day, lone Wolf No. 10, back in the Huron

Mountain area, killed a 4–5-year-old doe with fat-depleted

marrow (5.6%).

No doubt not all of the deer killed or fed upon by

the translocated wolves were found, even when snow

was present. However, it is clear from the observations

we did make, and from the fact that all 26 scats

we analyzed from this pack contained deer hair, that

the wolves did adapt to killing deer in their new environment

and that it was their primary food.

Near Atlantic Mine the wolves scavenged on garbage

from loggers, and then near Otter Lake they

spent several days also feeding on garbage. A discarded

cow (Bos taurus) head was scavenged, and at

least one red-backed vole (Clethrionomys gapperi)

was consumed. Lone Wolf No. 10 was found near the

Big Bay dump nine times, or 29% of the times she

was located during tourist season (May through

August).

Table 4. Analysis of scats collected from released wolves

| Date | No. Scats | Wolf No. | Location and items found |

| March 22 | 5 | Pack | Laws Lake, deer hair |

| March 29 | 1 | Pack | Otter Lake area, deer hair, red-backed vole hair, grass, refuse (including coffee grounds) |

| April 3 | 2 | Pack | Otter Lake deer kill, scats soft and dark, some deer hair |

| April 8 | 3 | Pack | Nisula, deer hair |

| April 17 | 5 | Pack | Kenton deer kill, scats soft and dark, deer hair |

| June 28 | 3 | Pack | Gibbs city area, summer and winter deer hair |

| Total (Pack) | 19 | ||

| March 27 | 2 | No. 10 | Conway Lake, deer hair |

| April 18 | 2 | No. 10 | Pine Lake, deer hair |

| June 1 | 1 | No. 10 | Huron Mountain Club, fawn deer hair and hoof |

| Total No. 10 | 5 | ||

| Sept. 20 | 1 | No. 11 | Floodwood Plains 3.1 miles (5.0 km) south of Witch Lake, deer hair, and ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) bones and nails |

| July 1 | 1 | No. 12 | Collected from under dead No. 12, 1.9 miles (3.0 km) north of Amasa, deer hair |

| Total | 26 | All |

[Pg 17]

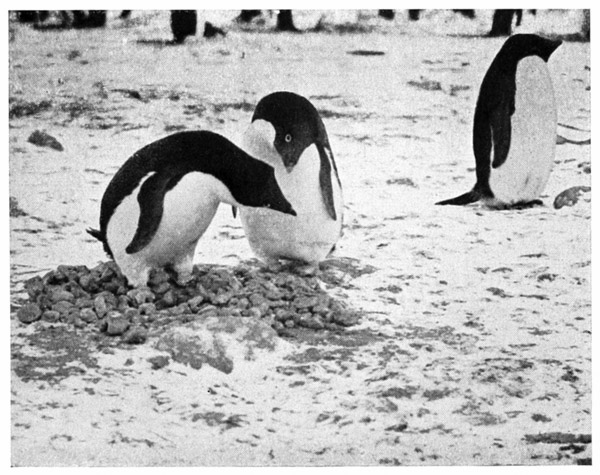

Fig. 21.—Each deer killed by the translocated wolves

was examined from the ground (Photo by Richard

P. Smith)

The three wolves were located near beaver lodges

or dams on April 10, April 15, May 7, June 8, and

June 12. No beavers were known to have been killed

by them, however, and no beaver remains were found

in their scats (Table 4).

Citizen Sightings

The wolves were seen by many citizens early after

their release (Table 5 and 6), no doubt because of

the wolves' confusion, their extensive movements,

and their lack of familiarity with the region. They

often traveled near populated areas and probably

moved more during the day than they would have in

their native territory. They were known to have made

14 daytime moves (from citizen reports) in addition

to those observed from the aircraft. In at least five

of the citizen reports, the wolves were observed sitting

alongside the road, or otherwise making little

attempt to move away immediately. However, after

April 13 the group of three wolves was reported by

citizens only twice, and Wolf No. 10, three times.

Table 5. Significant events in history of Wolf No. 10

| Date | Event |

| March 12 | Wolves released in Huron Mountain area (T52N-R28W-Sec 20) |

| March 13 | No. 10 separated from the other three wolves and never reunited |

| March 15 | Sighted from tracking car crossing County Road 492 south of Marquette County Airport, 6:35 p.m. (EDT) (T47N-R26W-Sec 33) |

| March 15 | Crossed a four-lane highway between Marquette and Negaunee about 4:00 p.m. (EDT) (T49N-R26W-Sec 29) |

| March 24 | Located from the air less than 0.5 miles (0.8 km) from release pen (T52N-R28W-Sec 20) |

| March 27 | Reported seen by Huron Mountain Club guard on edge of First Pine Lake, 6:30 p.m. (EDT) (T52N-R28W-Sec 29) |

| April 18 | Visited bear carcass 100 feet (30.5 m) from release pen, had also visited 3 nearby deer carcasses (T52N-R28N-Sec 20) |

| April 18 | Confirmed deer kill by No. 10 near Pine Lake, Huron Mountain Club (T52N-R28W-Sec 20) |

| June 6 | Reported seen by gate guard, Huron Mountain Club (T51N-R27W-Sec 6) |

| June 3 | Reported seen north of Saux Head Lake on Lake Superior beach (T50N-R26W-Sec 17) |

| June 20 | Reported seen crossing four-lane highway headed north about 5 miles (8.0 km) west of Marquette (T50N-R26W-Sec 24) |

| May 22 May 23 June 5 July 15 July 20 July 31 Aug. 6 Aug. 13 | Located near Big Bay dump, probably scavenging. Bears are baited at the dump by local citizens and tourists (T51N-R27W-Sec 16) |

| Aug. 16 | Back in Huron Mountain area between Conway and Ives Lakes. 5:35 p.m. (EDT) (T52N-R28W-Sec 35) |

| Aug. 27 | Returned to Big Bay dump, 11:10 a.m. (EDT) (T51N-R27W-Sec 16) |

| Aug. 30 | Huron Mountain area, 8:45 a.m. (EDT) (T49N-R28W-Sec 9) |

| Sept. 2 | Left Huron Mountain area for last time. Located on Yellow Dog Plains, 8:45 a.m. (EDT) (T50N-R28W-Sec 13) |

| Sept. 5 | Near Silver Lake, 8:45 a.m. (EDT). Begins rambling move westward out of established range (T49N-R28W-Sec 17) |

| Sept. 15 | Tracked on ground on Mulligan Plains, 4:45 p.m. (EDT) (T49N-R28W-Sec 9) |

| Oct. 22 | Farthest west, 22 miles (35.4 km) west of Silver Lake. Begins rambling return east. |

| Nov. 16 | Killed ½ mile (0.8 km) south of Van Riper Lake, 5.4 miles (8.4 km) north of Champion (T49N-R30W-Sec 36) |

[Pg 18]

Table 6. Significant events in history of Wolves

No. 11, 12 and 13

| Date | Event |

| March 12 | Wolves released in Huron Mountain area (T52N-R28W-Sec 20) |

| March 18 | Two wolves reported seen near Ravine River, Skanee area, the smaller one limping (T51N-R31W-Sec 2) |

| March 19 | First aerial fix of the three wolves in the same location (T52N-R31W-Sec 36) |

| March 20 | Wolves reported howling about 2 miles (3.2 km) east of Arvon Tower, 10 miles (16 km) south of Skanee (T50N-R31W-Sec 4) |

| March 22 | Wolves dug up five discarded doe and fawn heads and 27 deer legs near Laws Lake (T50N-R32W-Sec 18) |

| March 22 | Wolves reported crossing highway north of Herman, 4 miles (6.4 km) southeast of L'Anse, 8:30 a.m. (EDT) (T50N-R33W) |

| March 25 | Wolves reported in Pelkie area 6 miles (9.6 km) east of Baraga by DNR officer, 8:30 a.m. (EDT) (T51N-R34W-Sec 27SW) |

| March 25 | Wolves crossed road 2.5 miles (4 km) north of Pelkie near Otter River 11:00 a.m. (EDT) 5 miles (8 km) southwest of Otter Lake (T51N-R34W-Sec 5) |

| March 25 | Wolves reported seen crossing Highway M26, 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Twin Lakes 7:30 a.m. (EDT) (T52N-R38W-Sec 12) |

| March 26 | Wolves reported seen by logger during most of morning 9:00–11:00 a.m. (EDT), 4 miles (6.4 km) south of Houghton, (T54N-R35W-Sec 14) |

| March 26 | Wolves crossed Highway M26 south of Atlantic, 4:30 p.m. (EDT), (T54N-R34W-Sec 16) |

| March 26 | Wolves sighted from aircraft, eating garbage from cutting crew, 4:20 p.m. (EDT) (T54N-R34W-Sec 9NE) |

| March 29 | Wolves reported being chased away from house by dog, had been feeding on discarded cow head 150 feet (45.7 m) from house near Otter Lake (T52N-R33W-Sec 5) |

| March 31 | Wolves sighted in Otter Lake area (T52N-R33W-Sec 5) |

| April 2 | First confirmed wolf-killed deer, Arnheim area about 10 miles (16 km) north of Baraga (T52N-R33W-Sec 11) |

| April 5 | Wolves reported seen at 9:00 a.m. (EDT) on county road 5 miles (8 km) southwest of Otter Lake, small wolf reported as appearing fat (T53N-R35W-Sec 36) |

| April 8 | Wolves dug up old deer carcass about 150 feet (45.7 m) from house near Nisula (T50N-R36W-Sec 4) |

| April 10 | Wolves reported seen by logger in Nisula area (T50N-R36W-Sec 5) |

| April 13 | One wolf sighted crossing Highway M28 in morning between Kenton and Sidnaw |

| April 15 | Wolves killed deer near Kenton (T47N-R36W-Sec 8) |

| April 18 | Observed the three wolves from the tracking aircraft swim the East Branch of Ontonagon River, southeast of Kenton (T47N-R37W-Sec 7) |

| May 2 | No. 13 split from other two wolves; found in northwest Ontonagon County (T51N-R32W-Sec 21) |

| May 7 | All wolves back in Iron County for the second time, not known to leave until July 15 |

| May 7 | Forest service crew reported seeing the wolves and tracking aircraft north of Gibbs City near old deer carcass (T45N-R35W-Sec 26) |

| May 15 | Loggers reported six wolves (one with collar) (T54N-R37W-Sec 33)—Probably saw the collared wolves twice |

| May 16 | Confirmation from aerial location that the three wolves had reunited south of Mallard Lake after May 2 split |

| June 19 | No. 13 again separated from No. 11 and 12 |

| July 11 | Wolf No. 12 found dead, killed by automobile just before July 6, north of Amasa (T45N-R33W-Sec 17) |

| July 15 | Wolf No. 11 moved out of Iron County for the first time since May 7, found north of Kenton (T49N-R38W-Sec 31) |

| July 20 | Wolf No. 13 found dead from gunshot, south of Sagola, last previous location (June 27) at same location where No. 12 killed by automobile (T52N-R30W-Sec 5) |

| Aug. 6 | Wolf No. 11 located near Wisconsin border, ¾ miles (1.2 km) east of Lac Vieux Desert, 10:15 a.m. (EDT) (T43N-R38W-Sec 9) |

| Aug. 13 | Wolf No. 11 located 1.5 miles (2.4 km) southeast of Ewen 25 miles (40.5 km) north of Lac Vieux Desert, 10:10 a.m. (EDT) (T46N-R40W-Sec 36) |

| Aug. 28 | No locations since Aug. 13. Wolf No. 11 back in Marquette County .25 miles (0.4 km) south of Squaw Lake, a 60-mile (96.5 km) move eastward (T45N-R30W-Sec 21) |

| Sept. 20 | No. 11 trapped and shot on Floodwood Plaine 3.1 miles (5.0 km) south of Witch Lake (T44N-R24W-Sec 11) |

[Pg 19]

Habitat Use

The relative percentages of various habitats in

which the translocated wolves were found during

aerial locations (Table 7) did not indicate a preference

for any particular habitat type. Evidently the

animals chose their travel routes and ranges on some

basis other than forest habitat, or at least habitat was

not of any overriding importance in their movements.

Table 7. Habitat types in which the released wolves

were located

| Habitat | No. of Locations | Percent of Total | Percent Available[12] |

| Northern Hardwoods | 43 | 48.3 | 40.9 |

| Northern Hardwoods-Coniferous[13] | (57) | ...[13] | ...[13] |

| Spruce-fir | 19 | 21.3 | 17.0 |

| Aspen-hardwoods | 11 | 12.4 | 20.5 |

| Elm-ash-maple | 1 | 1.1 | 4.5 |

| Pine | 2 | 2.2 | 5.5 |

| Oak | 0 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| Non-commercial forests | 0 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| Other (near towns, farms, dumps) | 13 | 14.6(8.9)[13] | 7.6 |

| __ | ______ | _____ | |

| Totals | 89(146) | 100.00 | 100.0 |

[12] Spencer and Pfeifer 1966.

[13] This forest type was not distinguished separately

by Spencer and Pfeifer (1966), so they did not

provide availability figures for it. Thus in this

comparison, we did not include the 57 wolf locations

that fell in the type. However in calculating

percentage figures for non-forest areas (towns,

farms, dumps), these 57 fixes could validly be

used as representing forest locations.

Failure of Female No. 11 to Whelp

There was no sign that adult female No. 11

whelped or attempted to locate or construct a den.

The usual gestation period for wolves is about 63 days

(Brown 1936). Because No. 11 was seen coupled in

copulation on February 12 and 16, she should have

whelped between April 13 and April 21, if she had

conceived. Probably she would have moved little during

the preceding 2 or 3 weeks (Mech 1970). However

no such changes in this animal's movements

were noticed. The three wolves stayed near Kenton

between April 15 and April 18 but also killed a deer

during that time. They moved extensively from April

19 to May 7. The only indirect evidence that the

female may have been pregnant was an observation

made by a local citizen on April 5 (Table 6) who saw

the three wolves and stated that the small wolf looked

"fat." This would probably have been No. 11, but a

full stomach could easily have been mistaken for

pregnancy.

Unfortunately, neither the reproductive tract collected

from No. 11 in September nor the blood sample

taken in early March shed any light on the cause for

the wolf's failure to produce pups. The ovaries did

contain corpora albicantia, indicating that at some

time the wolf had ovulated, but it could not be stated

with certainty just when (R. D. Barnes, personal communication).

The blood progesterone levels were

more helpful. No. 11 had 3,560 picograms of progesterone

per milliliter, compared to 56 picograms per

milliliter for Wolf No. 10, whose reproductive tract

appeared immature. This high progesterone level of

No. 11 indicated that the animal had recently ovulated,

but it was impossible to tell whether she was

carrying any fetuses at the time the sample was taken

(U. S. Seal, personal communication).

Demise of the Translocated Wolves

All four translocated wolves were killed by humans

(Table 8). The alpha male (No. 12) was the first

victim. He was found from the air in the same location

on July 6 and 10. A ground check on July 11

showed him already decomposed. He lay about 60

feet (18.3 m) from paved highway US 141 north of

Amasa (Fig. 22). The articular processes on the right

side of his fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae were

broken and inverted. Part of the process of the sixth

cervical vertebra was lodged in the neural canal

between the fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae and

would have exerted pressure on his spinal cord. His[Pg 20]

acrylic radio collar was also cracked on the right side

in three places. We concluded that he had been struck

and killed by an automobile. A scat found beneath

the remains contained deer hair, so apparently the

animal had been feeding not long before his death.

Fig. 22.—The remains of Wolf No. 12 were found

near a highway, and broken bones indicated he had

been hit by a vehicle (Photo by Richard P. Smith)

Wolf No. 13 was killed next. He had been located

south of Sagola in Dickinson County on July 20, the

first time he was found since June 27. He was still

there on July 27, so a ground check was made. It

revealed that the wolf had been dead for perhaps 2

or 3 weeks. His flesh had decomposed, and only hair,

bones and the transmitting collar remained (Fig. 23).

His leg bones and ribs were mostly disarticulated, his

skull was separated from the vertebral column, and

his mandible had separated. A small caliber bullet

had passed through the ramus of the left mandible

and had entered the base of the cranium. The hole

through the mandible was 0.26 inch × 0.34 inch (6.6

mm. × 8.6 mm.) and that through the cranium was

0.34 inch × 1.30 inch (8.6 mm. × 33.0 mm.). Three

small lead fragments were removed from the cranium.

Fig. 23.—Wolf No. 13 had been shot, as the hole in

the jawbone indicates (Photo by Tom Weise)

The remains of Wolf No. 13 were sent to the

Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife

Research Center at Rose Lake and examined by staff

pathologists Dr. L. D. Fay and Mr. John Stuht. No

fractures or other signs were found that might indicate

that he had been trapped. However, some of the

smaller foot bones were missing and a complete examination

was not possible. Notches were found in both

shoulder blades, and one rib was broken, suggesting

that the animal had been shot twice by a small caliber

firearm in addition to the head shot. The hole in the

left scapula indicated a deep penetrating wound. The

notch in the right scapula indicated a bullet traveling

more parallel to the body.

Table 8. Details of Deaths of Translocated Wolves

| Wolf No. | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Last date tracked | Nov. 17 | Sept. 19 | July 10 | July 27 |

| Date killed | Nov. 16[14] | Sept. 20 | June 28 to July 4 | Early July[14] |

| Date found | Nov. 18 | Sept. 20 | July 11 | July 28 |

| Manner of death | Gunshot in head and right foreleg | Gunshot in, head, after being trapped | Struck by automobile | Gunshot in head and chest |

| Location of death | Van Riper Lake 5.4 miles (8.7 km) north of Champion (T49N-R30W-Sec 36) | Floodwood Plain 3.1 miles (5.0 km) south of Witch Lake (T44N-R24W-Sec 11) | 1.9 miles (3.0 km) north of Amasa (T45N-R33W-Sec 17) | 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Sagola (T42N-R30W-Sec 5) |

| Weight | 52 lb. | 56.5 lb. | ||

| (23.6 kg) | (25.6 kg) | Unknown[15] | Unknown[15] | |

| Condition | Excellent | Good | Unknown[15] | Unknown[15] |

[14] Estimate

[15] Decomposed

[Pg 21]

Wolf No. 11 was caught the night of September 19,

1974 in a coyote trap set by a trapper from Channing.

The next morning the trapper came upon the trapped

wolf by surprise at a range of 12 feet (3.6 m). She

growled and lunged toward him, and thinking he was

in danger, the trapper shot the wolf in the head. The

.22 caliber bullet entered below the right eye and

lodged in the skull. The trapper immediately took

the animal to the Michigan Department of Natural

Resources office in Crystal Falls and reported the

incident.

The wolf weighed 56.5 lb. (25.6 kg), 1.5 lb. (0.68

kg) less than when she was brought to Michigan. Her

general condition was good, with some omental fat,

but no subcutaneous fat. She did harbor ten tapeworms

(Taenia pisiformis) about 40–50 cm long and

a few hookworms (Uncinaria stenocephala), as determined

by Mr. John Wenstrom (personal communication),

Biology Department, Northern Michigan University.

Both are common tapeworms of wolves (Mech

1970).

Wolf No. 10 was shot by a deer hunter, probably on

the morning of November 16, the second day of firearms

deer season. On November 17 her signal was

heard from near a cabin on the south shore of Van

Riper Lake. The hunters occupying the cabin later

said they had removed the collar from the wolf, which

they had found dead on the afternoon of November

16. Before we had learned this, the carcass of Wolf

No. 10 was discovered without the collar by another

hunter, about a half mile (0.8 km) south of Van

Riper Lake. It had been shot through the right leg,

shattering the radius and ulna, and through the head,

the bullet entering the left frontal bone and exiting

below the right eye. In addition the radio collar had

been shattered by a bullet and was missing, and one

ear had been cut off. We identified the wolf from

the tag in the other ear.

The wolf had gained 6 lb. (2.7 kg) since she had

been brought to Michigan, and had heavy internal

and subcutaneous fat. She had light infections of two

species of tapeworms (Echinococcus granulosus and

Taenia pisiformis), and of one species of hookworm

(Uncinaria stenocephala), as determined by John

Wenstrom. Echinococcus granulosus is not uncommon

in wolves (Mech 1970). The other two species were

discussed above.

DISCUSSION

Wolves No. 11, 12, and 13 undoubtedly were members

of the same pack. This conclusion is based on the

fact that they did not fight when placed together in

captivity, that they freely intermixed while penned,

that No. 11 and No. 12 copulated, and that all three

wolves generally traveled as a unit after their release.

No. 11 and No. 12 were always located together from

a few days after their release until the death of No.

12. Temporary splitting, as with No. 13 is a normal

occurrence in wild wolf packs (Mech 1966).

The identity of Wolf No. 10 remains unknown. She

was captured 7.5 miles (12.1 km) away from the

other three, and in captivity she behaved differently

from them, remaining more to herself but intermingling

with the others occasionally, with no signs of

aggression. The face licking of No. 10 by No. 11 could

be interpreted as a sign of patronizing intimacy as an

adult might treat a subordinate offspring. The teeth

of Wolf No. 10 had very little wear, indicating that

she probably was less than 3-years old, whereas the

teeth of No. 11 were blunt from wear. The tendency

for No. 10 to withdraw from the others and from

human beings indicated that she probably was a low-ranking

or subordinate animal, a peripheral member

of the pack (Woolpy 1968), or even a lone wolf

currently dispersing from the pack (Mech 1973).

The separation of No. 10 from the others upon

release does not necessarily mean that she was not a

member of the pack. No. 10's radio collar was replaced

just before she was released. The handling

without sedation could have frightened her enough

that she ran some distance before the others were

even released. The fact that No. 10 returned to within

a half mile (0.8 km) of the release pen on March

20 and to within less than 100 feet (30.5 m) on April

18 may indicate she was seeking the other wolves.

However, she may also just have used the release pen

as a reference point in a generally unfamiliar area, or

may have been attracted by the remains of carcasses

left there.

Effect of Captivity and Human Contact

The necessary capture, captivity, translocation and

contact of the experimental wolves with humans had

an unknown effect on the wolves. They had been

exposed to humans for over 2 months while in captivity.

No attempts were made to tame them, and

they never passed the escape stage of socialization as

described by Woolpy and Ginsburg (1967). The

dominant wolves (No. 11 and No. 12) were more

relaxed when approached than were No. 10 and No.

13, however.

The failure of female No. 11 to bear young probably

can be attributed to her captivity and handling.

The fact that two couplings were observed over a

5-day period indicates normal estrus in the female,

and a normal response in the male. Conception would[Pg 22]

have been expected from such a mating. In wild

wolves, it is known that there is only a small loss between

number of ova shed, number of embryos implanting,

and number of fetuses being carried (Rausch

1967). Thus it seems unlikely that, if No. 11 conceived,

she lost her fetuses in utero. Rather, she probably

did not conceive, or perhaps the embryos never

implanted. This wolf lost about 11% of her capture

weight during captivity, despite an adequate food

supply. This fact, plus the results of her blood tests

indicate a high degree of stress, which probably explains

why she never produced pups.

The possible interference of the drugs used can be

ruled out, for they were chosen because of their

known lack of effect on pregnancy (Seal et al. 1970).

The radio collars placed on the wolves had no

noticeable effect on the animals. Radioed wolves are

regularly accepted back into their packs in Minnesota,

where they also reproduce and function normally

(Mech and Frenzel 1971; Mech 1973, 1974).

Movements

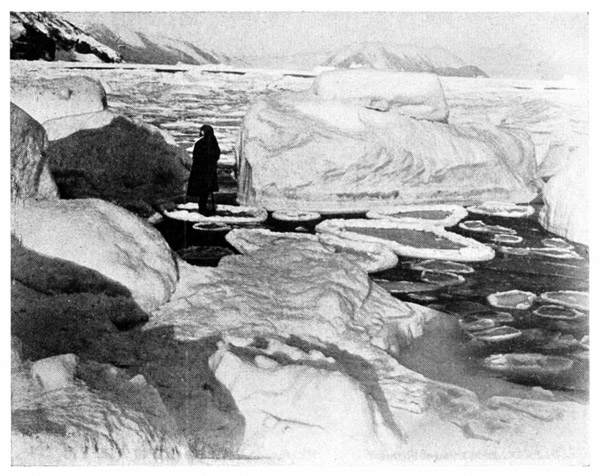

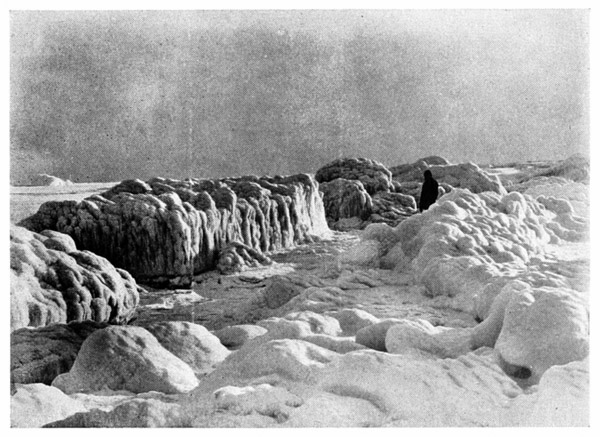

Environmental Influences

Lake Superior was a barrier to the northward and

eastward movements of the wolves. Apparently it also

directed wolves No. 11, 12, and 13 southward around

Keweenaw Bay, and possibly it prevented their eastward

movement on April 2 when they approached

Keweenaw Bay from the western side. The Bay is

approximately 6-miles (9.6 km) wide there, and was

frozen until late April.

One to two miles (3.2 km) south of the release site,

the Huron Mountains, with an elevation of 1,500

feet (457.5 m) might have prevented the southward

movement of the wolves. Along the lakeshore, the

land is relatively flat, which may have facilitated east-west

movement. Wolves No. 11 and 13 were found at

an elevation of 1,300 feet (490 m) the day after

release but had returned to the flat shore areas (600

to 700 feet, or 200 to 230 meters above sea level) by

the next day. Topography likely had effects in other

areas but the actual travel routes, in most instances,

are unknown. The pack did travel along an abandoned

railroad grade near Gibbs City and for 2 miles

(3.2 km) on a muddy road north of Kenton. Wolf

No. 10 used a railroad bridge to cross a river in mid-March.

It is well known that wolves generally choose

the easiest routes of travel (DeVos 1950, Stenlund

1955, Mech 1966).

Possible Homing Tendencies

Some of the movements of the wolves during the

Directional Movements Phase could in part have

resulted from a tendency for the animals to home,

that is to return to their home territory. Packs have

been observed to travel 45 miles (72 km) in 24 hours

in Minnesota (Stenlund 1955), Alaska (Burkholder

1959) and on Isle Royale (Mech 1966). In Minnesota,

a radioed wolf was tracked a straight-line distance

of 129 miles (208 km) over a 2-month period

before being lost by researchers (Mech and Frenzel

1971), and annual migratory movements of over 200

miles (320 km) have been reported for Canadian

wolves (Kuyt 1972). Therefore it seems within the

capabilities of the released wolves to return the 270-mile

(434 km) straight-line distance, or the 340-mile

(547 km) travel distance around Lake Superior to

Ray, Minnesota, if the orientation ability and inclination

were present.

Homing tendencies have been reported in wolves

and other carnivores. One of five laboratory-reared

wolves returned to her Barrow, Alaska homesite within

about 4 months after a 175-mile (282 km) displacement

(Henshaw and Stephenson 1974). An

adult female red fox (Vulpes vulpes) returned to her

homesite within 12 days after being displaced 35 miles

(56.3 km) (Phillips and Mech 1970). For black bears

there are many records of apparent homing. Harger

(1970) displaced 107 adult black bears from 10.0 to

168.5 miles (16.1 to 270.3 km) with an average displacement

of 62.5 miles (100.6 km). Thirty-seven of

them homed and 11 others moved long distances

toward home. The longest distance homed was 142.5

miles (229.4 km). The return travel routes seemed

direct, with little evidence of wandering or circling.

Harger (1970) concluded that bears could navigate

by some means, as yet undetermined.

There is some indication that the pack of three

wolves may have attempted to return home to Minnesota,

although it is possible that exploration itself

also may have produced the movement pattern

observed.

If the translocated wolves were to try homing

directly toward their previous territory, they would

have had to travel west-northwestward. However,

within a few miles they would have encountered Lake

Superior. The next closest choice would have been to

head westward, and this is what the pack did (Fig.

17). The next possible barrier to their homeward

movements would have been Huron Bay, which

would have forced them southwestward, at least temporarily.

Again this is what actually happened. The

pack maintained its southwestward movement beyond

Huron Bay until reaching a point southeast of the[Pg 23]

next possible barrier, Keweenaw Bay. They then continued

westward south of Keweenaw Bay to the Prickett

Dam area, and veered northwestward to Twin

Lakes on March 25.

By this time, the wolves had traveled for 13 days

and covered a minimum distance of 59 miles (94.9

km), and they were 42 miles (67.6 km), closer to

home (16% of the straight-line distance between

home and release site). The directions of the movements

of the wolves were consistent with what they

would have to be if the wolves were to return home.

However, after March 25, the directionality in the

movements of the pack ended (Fig. 17), and the

animals began what we consider the Exploratory

Phase of their movements. If the wolves actually were

homing, perhaps the tendency diminished as they

failed to encounter familiar terrain, or perhaps they

met too many obstacles, or became confused after

encountering too much human activity. Or possibly

these factors or the need to find food and security

overcame the homing tendency. As discussed earlier

in relation to the unusual number of times the wolves

were observed, it is clear that they were not moving

normally during this period.

The lone wolf, No. 10, dispersed from the release

site in as much of an opposite direction as it could

from the pack (Fig. 20). Thus there is no evidence

that this animal was trying to home. However, it is

of interest to note that the first 32 miles (51.5 km)

of her travel was directional rather than random.

Furthermore, when the animal encountered what

probably was a psychological barrier, a high concentration

of human activity along Highway 41, she

reversed her movements but still maintained a directionality

by returning to the release area. In fact a

striking pattern of southeast-northwest movements

characterized this wolf's travels for several months

after her release, with a gradual westward drift developing

in the southeast-northwest movements (Fig.

20).

Mech and Frenzel (1971) found that a wolf dispersing