The Project Gutenberg eBook of Amphibians and Reptiles of the Rainforests of Southern El Petén, Guatemala

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Amphibians and Reptiles of the Rainforests of Southern El Petén, Guatemala

Author: William Edward Duellman

Release date: December 24, 2011 [eBook #38398]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF THE RAINFORESTS OF SOUTHERN EL PETÉN, GUATEMALA ***

[205]

University of Kansas Publications

Museum of Natural History

Volume 15, No. 5, pp. 205-249, pls. 7-10, 6 figs.

October 4, 1963

October 4, 1963

Amphibians and Reptiles of the Rainforests

of Southern El Petén, Guatemala

BY

WILLIAM E. DUELLMAN

University of Kansas

Lawrence

1963

[206]

University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, Henry S. Fitch,

Theodore H. Eaton, Jr.

Vol. 15, No. 5, pp. 205-249, pls. 7-10, 6 figs.

Published October 4, 1963

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

PRINTED BY

JEAN M. NEIBARGER, STATE PRINTER

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1963

29-5935

[207]

Amphibians and Reptiles of the Rainforests

of Southern El Petén, Guatemala

BY

WILLIAM E. DUELLMAN

CONTENTS

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | 207 | |

| Acknowledgments | 208 | |

| Description of Area | 208 | |

| Physiography | 209 | |

| Climate | 209 | |

| Vegetation | 209 | |

| Gazetteer | 210 | |

| The Herpetofauna of the Rainforest | 211 | |

| Composition of the Fauna | 212 | |

| Ecology of the Herpetofauna | 212 | |

| Relationships of the Fauna | 217 | |

| Accounts of Species | 218 | |

| Hypothetical List of Species | 246 | |

| Summary | 247 | |

| Literature Cited | 247 | |

INTRODUCTION

Early in 1960 an unusual opportunity arose to carry on biological

field work in the midst of virgin rainforest in southern El Petén,

Guatemala. At that time the Ohio Oil Company of Guatemala had

an air strip and camp at Chinajá, from which place the company

was constructing a road northward through the forest. In mid-February,

1960, J. Knox Jones, Jr. and I flew into El Petén to

collect and study mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. While enjoying

the comforts of the fine field camp at Chinajá, we worked

in the surrounding forest and availed ourselves of the opportunity

to be on hand when the road crews were cutting the tall trees in

the forest, thereby bringing to the ground many interesting specimens

of the arboreal fauna. We stayed at Chinajá until late March,

with the exception of a week spent at Toocog, another camp of the

Ohio Oil Company located 15 kilometers southeast of La Libertad

and on the edge of the savanna. Thus, at Toocog we were able[208] to work both in the forest and on the savanna. In the summer of

1960, John Wellman accompanied me to El Petén for two weeks

in June and July. Most of our time was spent at Chinajá, but a

few days were spent at Toocog and other localities in south-central

El Petén.

Many areas in Guatemala have been studied intensively by

L. C. Stuart, who has published on the herpetofauna of the forested

area of northeastern El Petén (1958), the savannas of central

El Petén (1935), and the humid mountainous region to the south

of El Petén in Alta Verapaz (1948 and 1950). The area studied

by me and my companions is covered with rainforest and lies to

the north of the highlands of Alta Verapaz and to the south of the

savannas of central El Petén. A few specimens of amphibians

and reptiles were obtained in this area in 1935 by C. L. Hubbs

and Henry van der Schalie; this collection, reported on by Stuart

(1937), contained only one species, Cochranella fleischmanni, not

present in our collection of 77 species and 617 specimens.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to L. C. Stuart of the University of Michigan, who made the

initial arrangements for our work in El Petén, aided me in the identification

of certain specimens, and helped in the preparation of this report. J. Knox

Jones, Jr. and John Wellman were able field companions, who added greatly

to the number of specimens in the collection. In Guatemala, Clark M.

Shimeall and Harold Hoopman of the Ohio Oil Company of Guatemala made

available to us the facilities of the company's camps at Chinajá and Toocog.

Alberto Alcain and Luis Escaler welcomed us at Chinajá and gave us every

possible assistance. Juan Monteras and Antonio Aldaña made our stay at

Toocog enjoyable and profitable. During our visits to southern El Petén, Julio

Bolón C. worked for us as a collector, and between March and June he collected

and saved many valuable specimens; his knowledge of the forest and

its inhabitants was a great asset to our work. Jorge A. Ibarra, Director of

the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural in Guatemala assisted us in obtaining

necessary permits and extended other kindnesses. To all of these people I

am indebted for the essential parts that they played in the completion of this

study.

Field work in the winter of 1960 was made possible by funds from the

American Heart Association for the purposes of collecting mammalian hearts.

My field work in the summer of 1960 was supported by a grant from the

Graduate Research Fund of the University of Kansas.

DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA

A vast lowland region stretches northward for approximately

700 kilometers from the highlands of Guatemala to the Gulf of

Mexico. The northern two-thirds of this low plain is bordered on

three sides by seas and forms the Yucatán Peninsula. The lowlands[209] at the base of the Yucatán Peninsula make up the Departamento

El Petén of Guatemala. The area with which this report is concerned

consists of the south-central part of El Petén.

Physiography

Immediately south of Chinajá is a range of hills, the Serrania de Chinajá,

having an almost due east-west axis and a crest of about 600 meters above

sea level. South of the Serrania de Chinajá are succeedingly higher ridges

building up to the Meseta de Cobán and Sierra de Pocolha and eventually

to the main Guatemalan highlands. The northern face of the Serrania de

Chinajá is a fault scarp dropping abruptly from about 650 meters at the crest

to about 140 meters at the base. From the base of the Serrania de Chinajá

northward to the Río de la Pasión at Sayaxché the terrain is gently rolling

and has a total relief of about 50 meters. North of the Río de la Pasión is

a low dome reaching an elevation of 170 meters at La Libertad; see Stuart

(1935:12) for further discussion of the physiography of central El Petén.

The rocks in southern El Petén are predominately Miocene marine limestones;

there are occasional pockets of Pliocene deposits. There is little evidence

of subterranean solution at Chinajá, but northward in central El Petén karsting

is common. The upper few inches of soil is humus rich in organic matter;

below this is clay.

Climate

The climate of El Petén is tropical with equable temperatures throughout

the year. Temperatures at Chinajá varied between a night-time low of 65° F.

and a daytime high of 91° F. during the time of our visits. In the Köppen

system of classification the climate at Chinajá and Toocog is Af. Rain falls

throughout the year, but there is a noticeable dry season. To anyone who

has traveled from south to north in El Petén and the Yucatán Peninsula, it is

obvious from the changes in vegetation that there is a decrease in rainfall

from south to north. There is a noticeable difference between Chinajá and

Toocog. Although rainfall data are not available for Chinajá and Toocog,

there are records for nearby stations (Sapper, 1932). At Paso Caballos on

the Río San Pedro about 40 kilometers northwest of Toocog the average

annual rainfall amounts to 1620 mm.; the driest month is March (21 mm.),

and the wettest months are June (269 mm.) and September (265 mm.). At

Cubilquitz, Alta Verapaz, about 35 kilometers south-southwest of Chinajá

and at an elevation of 300 meters, the average annual rainfall is 4006 mm.;

the driest month is March (128 mm.), and the wettest months are July (488

mm.) and October (634 mm.).

During the 18 days in February and March, 1960, that we kept records on

the weather at Chinajá moderate to heavy showers occurred on seven days.

During our stay there in June and July rain fell every day, as it did in Toocog.

However, during the week spent at Toocog in March no rain fell.

Vegetation

The vegetation of northern and central El Petén has been studied by

Lundell (1937), who made only passing remarks concerning the plants of the

southern part of El Petén. No floristic studies have been made there. The[210] following remarks are necessarily brief and are intended only to give the

reader a general picture of the forest. I have included names of a few of

the commoner trees that I recognized.

Chinajá is located in a vast expanse of unbroken rainforest. In this forest

there is a noticeable stratification of the vegetation. Three strata are apparent;

in the uppermost layer the tops of the trees are from 40 to 50 meters above

the ground. The spreading crowns of the trees and the interlacing vines form

a nearly continuous canopy over the lower layers. Among the common trees

in the upper stratum are Calophyllum brasiliense, Castilla elastica, Cedrela

mexicana, Ceiba pentandra, Didalium guianense, Ficus sp., Sideroxylon lundelli, Swietenia macrophylla, and Vitex sp. (Pl. 1, fig. 1). The middle layer of

trees have crowns about 25 meters above the ground; these trees in some

places where the upper canopy is missing form the tallest trees in the forest. This

is especially true on steep hillsides. Common trees in the middle layer include Achras zapote, Bombax ellipticum, Cecropia mexicana, Orbignya cohune, and Sabal sp. The lowermost layer reaches a height of about 10 meters; in many

places in the forest this layer is absent. Common trees in the lower stratum

include Crysophila argentea, Cymbopetalum penduliflorum, Casearia sp., and Hasseltia dioica.

The ground cover is sparce; apparently only a few small herbs and ferns

live on the heavily shaded forest floor. Important herpetological habitats

include the leaf litter, rotting stumps, and rotting tree trunks on the forest

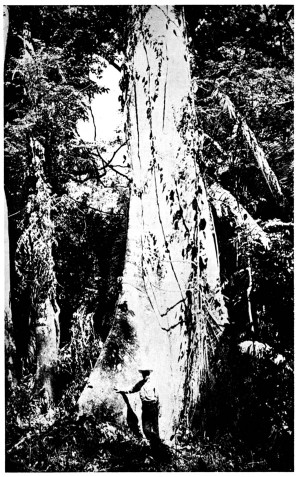

floor and the buttresses of many of the gigantic trees, especially Ceiba pentandra (Pl. 2). Epiphytes, especially various kinds of bromeliads, are common.

Most frequently these are in the trees in the upper and middle strata.

At Toocog there is sharp break between savanna and forest (Pl. 7, fig. 2).

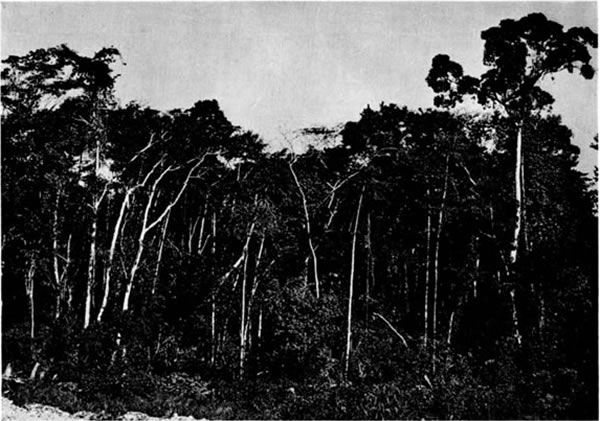

The forest is noticeably drier and more open than at Chinajá (Pl. 9). The

crowns of the trees are lower, and there is no nearly continuous canopy between

40 and 50 meters above the ground. Although Swietenia macrophylla and

other large trees occur, they are less common than at Chinajá. Especially

common at Toocog are Achras zapote, Brosimum alicastrum, and various species

of Ficus.

GAZETTEER

The localities from which specimens were obtained are cited below and

shown on the accompanying map (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Map of El Petén, Guatemala, showing localities mentioned in text.

Fig. 1. Map of El Petén, Guatemala, showing localities mentioned in text. Chinajá.—Lat. 16° 02´, long. 90° 13´, elev. 140 m. Camp of the Ohio Oil

Company of Guatemala and formerly a small settlement. On some maps

Chinajá is located just to the north of the Alta Verapaz—El Petén boundary;

recent surveys place the location just to the south of the imaginary line

through the rainforest. Field work was conducted in the immediate vicinity

of the camp, on the lower slopes of the Serrania de Chinajá, and at several

sites to the northwest and north-northwest of Chinajá, where the forest

was being cleared. The entire area supports rainforest.

La Libertad.—Lat. 16° 47´, long. 90° 07´, elev., 170 m. A town on the

savannas in central El Petén; although we collected there in the rainy season,

the specimens obtained on the savannas are not included in this report.

Paso Subín.—Lat. 16° 38´, long. 90° 12´, elev. 90 m. A small settlement on

the Río Subín, a tributary of the Río de la Pasión. Specimens were obtained

in rainforest in the immediate vicinity of the settlement.

Río de la Pasión.—A large river flowing northward through southern El Petén

and thence westward into the Río Usumacinta. Specimens were obtained

along the river between the Río Subín and Sayaxché.

[211]

Río San Román.—A river flowing northward in south-central El Petén to the

Río Salinas (Usumacinta). We collected along the river at a place about

16 kilometers north-northwest of Chinajá, approximately at Lat. 16° 10´,

long. 90° 17´, elev. 110 m. In the dry season the river was clear; it is

surrounded by rainforest.

Sayaxché.—Lat. 16° 31´, long. 90° 09´, elev. 80 m. A town on the southern

bank of the Río de la Pasión. Specimens were obtained in the rainforest

and in cleared areas in the immediate vicinity of the town.

Toocog (formerly Sojío).—Lat. 16° 41´, long. 90° 02´, elev. 140 m. A camp

of the Ohio Oil Company of Guatemala located at the rainforest-savanna

edge, 15 kilometers southeast of La Libertad. Although we collected on

the savannas as well as in the forest, especially to the east of the camp,

only species obtained in the forest are considered in this report.

THE HERPETOFAUNA OF THE RAINFOREST

In presenting an account of the herpetofauna of southern El Petén three

items need to be considered: (1) The composition of the fauna; (2) the

ecology of the fauna; (3) the relationships of the fauna. Each of these

topics is discussed briefly below. Logically a discussion of the origin of the

fauna should follow, but this is being withheld for inclusion in a report

on the herpetofauna of the entire El Petén by L. C. Stuart and the author;

at that time the above topics will be expanded to cover the herpetofauna of

the whole region.

[212]

Composition of the Fauna

Table 1.—Composition of the Herpetofauna in Southern

El Petén, Guatemala.

Group | Families | Genera | Species |

| Gymnophiona | (1)[A] | (1) | (1) |

| Caudata | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Salientia | 6 | 10 (1) | 19 (1) |

| Crocodilia | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Testudines | 4 | 7 | 8 |

| Sauria | 6 | 13 (1) | 19 (1) |

| Serpentes | 4 | 21 (7) | 29 (10) |

Total | 22 (1) | 53 (10) | 78 (13) |

[A] Numbers in parenthesis indicate the number of additional taxa that probably occur.

A total of 78 species of amphibians and reptiles has been found in the

rainforests in southern El Petén; a break down into families and genera is

given in table 1. Another 13 species probably occur in southern El Petén (see

Hypothetical List of Species). The fauna primarily is composed of typical

humid lowland forest inhabitants, such as:

| Hyla ebraccata | Eumeces sumichrasti |

| Hyla loquax | Ameiva festiva edwardsi |

| Phyllomedusa callidryas taylori | Imantodes cenchoa leucomelas |

| Smilisca phaeota cyanosticta | Leptophis ahaetulla praestans |

| Anolis biporcatus | Xenodon rabdocephalus mexicanus |

| Anolis capito | Bothrops nasutus |

| Anolis humilis uniformis | Bothrops schlegeli schlegeli |

Nevertheless, the region also provides at least a limited amount of habitat

suitable for some species that are more frequently found in open forest of

a drier nature; such species include:

| Hyla microcephala martini | Anolis sericeus sericeus |

| Hyla staufferi | Eumeces schwartzei |

| Hypopachus cuneus nigroreticulatus | Oxybelis aeneus aeneus |

Because of the absence of sufficiently open habitat or owing to the

presence of competitors, some conspicuous members of sub-humid forests are

not present in southern El Petén. Conspicuous absentees are the following:

| Rhinophrynus dorsalis | Ameiva undulata |

| Phrynohyas spilomma | Cnemidophorus angusticeps |

| Triprion petasatus | Conophis lineatus |

| Anolis tropidonotus | Masticophis mentovarius mentovarius |

| Ctenosaura similis |

PLATE 7

Fig. 1. Edge of rainforest along airstrip at Chinajá, El Petén, Guatemala.

Fig. 1. Edge of rainforest along airstrip at Chinajá, El Petén, Guatemala. Fig. 2. Rainforest at edge of savanna at Toocog, El Petén, Guatemala.

Fig. 2. Rainforest at edge of savanna at Toocog, El Petén, Guatemala. PLATE 8

Interior of rainforest at Chinajá. Notice size of buttresses on large tree (Ceiba

Interior of rainforest at Chinajá. Notice size of buttresses on large tree (Ceibapentandra).

PLATE 9

Interior of rainforest at Toocog. Notice less dense vegetation as compared

Interior of rainforest at Toocog. Notice less dense vegetation as comparedwith Pl. 8.

PLATE 10

Fig. 1. Rainforest along Río San Román, 16 kilometers north-northwest of

Fig. 1. Rainforest along Río San Román, 16 kilometers north-northwest ofChinajá.

Fig. 2. Rain pond in forest at Toocog. This was a breeding site for six species

Fig. 2. Rain pond in forest at Toocog. This was a breeding site for six speciesof frogs.

Ecology of the Herpetofauna

Our two visits to Chinajá and Toocog afforded the opportunity

to gather data on the ecology of the rainforests of southern El Petén

and to study the relationships between the environment and members

of the herpetofauna. Tropical rainforests present the optimum[213] conditions for life, and it is in this environment that life

reaches its greatest diversity. Here, too, biological inter-relationships

are most complex. This complexity is illustrated by the

presence of many species of some genera, all of which are found

together in the same geographic region. In the rainforests of

southern El Petén there are six species of Anolis, five of Hyla,

four of Bothrops, and three of Coniophanes. Obviously, the diversity

of ecological niches in the rainforest is sufficient to support

a variety of related species. Of the examples mentioned above,

fairly adequate ecological data were obtained for most of the

species of Anolis, which will be used to show the ecological diversity

and vertical stratification of sympatric species in the rainforests.

Of the six species of Anolis, all except A. sericeus are typically

found in humid forests. Anolis sericeus sericeus is poorly represented

in the collections from southern El Petén, where it may be

in competition with Anolis limifrons rodriguezi that resembles Anolis

s. sericeus in size, coloration, and habits. Therefore, Anolis sericeus

sericeus is excluded from the following discussion. The common

terrestrial species is Anolis humilis uniformis; sometimes

this small species perches or suns on the bases of small trees or

buttresses of some large trees. When disturbed it takes to the

ground and seeks cover in the leaf litter or beneath logs or palm

fronds. Anolis lemurinus bourgeaei is about twice the size of Anolis humilis uniformis and is usually observed on buttresses of

large trees or on the lower two meters of tree trunks. Individuals

were seen foraging on the ground along with Anolis humilis

uniformis. At no time were Anolis lemurinus bourgeaei observed

to ascend the trunks of large trees; they always took refuge near

the bases of trees. Anolis limifrons rodriguezi is found on the

stems and branches of bushes. It is a small species that sometimes

is observed on the ground but was never seen ascending large

trees. Anolis capito is about the same size as Anolis lemurinus

bourgeaei and lives on the trunks of large trees. In the tops of

the trees lives a large green species, Anolis biporcatus.

Similar segregation habitatwise can be demonstrated for other

members of the herpetofauna. The avoidance of interspecific

competition in feeding is well illustrated by three species of snakes

that probably are the primary ophidian predators on frogs. Drymobius margaritiferus margaritiferus is diurnal and terrestrial;

it feeds on frogs at the edges of breeding ponds by day. Also

during the day Leptophis mexicanus mexicanus feeds on frogs in[214] bushes and trees. At night the activities of both of these species

is replaced by those of Leptodeira septentrionalis polysticta, which

not only feeds on the frogs in the trees and bushes, but descends

to the ground and even enters the water in search of food.

From the examples discussed above, the importance of the

three dimensional aspect of the rainforest is apparent. The

presence of a large and diverse habitat above the ground is of

great significance in the rainforest, for of the non-aquatic components

of the herpetofauna in the rainforests of southern El Petén,

42 per cent of the species spend at least part of their lives in the

bushes and trees. Another important part of the forest is the

subterranean level—the rich mulch, underground tunnels, and

rotting subterranean vegetation. Of the 78 species of amphibians

and reptiles in southern El Petén, seven are primarily fossorial, and

half-a-dozen others are secondarily fossorial. Probably the fossorial

members of the fauna are the least well represented in the

collection, for such widespread species as Dermophis mexicanus

mexicanus, Rhadinaea decorata decorata and Tantilla schistosa

schistosa were expected, but not found.

In the following discussion of the ecological distribution of

amphibians and reptiles in the rainforest I have depended chiefly

on my observations made in southern El Petén, but have taken

into consideration observations made on the same species in other

regions, together with reports from other workers. The reader

should keep in mind that the evidence varies from species to species.

Of some species I have observed only one animal in the

field; of others, I have seen scores and sometimes hundreds of

individuals. For species on which I have few observations or

rather inconclusive evidence, the circumstance of inadequate

data is mentioned.

In analyzing the ecological distribution within the forest, it is

convenient to recognize five subdivisions (habitats); each is

treated below as a unit.

1. Aquatic.—This habitat includes permanent streams and rivers

(Pl. 10, fig. 1), some of which are clear and others muddy. In

the rainy season temporary ponds form in depressions on the forest

floor (Pl. 10, fig. 2); these are important as breeding sites for

many species of amphibians. Aquatic members of the herpetofauna

are here considered to be those species that either spend

the greatest part of their lives in the water or usually retreat to

water for shelter. Seven species of turtles and one crocodilian are[215] aquatic. Of these, Dermatemys mawi, Staurotypus triporcatus,

and Pseudemys scripta ornata inhabit clear water, whereas Chelydra

rossignoni, Claudius angustatus, Kinosternon acutum, and K. leucostomum inhabit muddy water. Crocodylus moreleti apparently

inhabits both clear and muddy water, for in the dry season it

lives along the clear rivers, but in the rainy season inhabits flooded

areas in the forest as well.

2. Aquatic Margin.—Extensive marshes were lacking in the

part of southern El Petén that I visited; consequently, the aquatic

margin habitat is there limited to the edges of rivers and borders

of temporary ponds. Bufo marinus, Rana palmipes, and Rana

pipiens are characteristic inhabitants of the aquatic margin,

although in the rainy reason Bufo marinus often is found away

from water. Observations indicate that Tretanorhinus nigroluteus

lateralis inhabits the margins of ponds and streams and actually

spends considerable time in the water. Although Iguana iguana

rhinolopha is arboreal, it lives in trees along rivers, into which it

plunges upon being disturbed. Species included in this category

are those that customarily spend most of their lives at the edge

of permanent water. Frogs and toads that migrate to the water

for breeding and the snakes that prey on the frogs at that time

are not assigned to the aquatic-margin habitat.

3. Fossorial.—Characteristic inhabitants of the mulch on the

forest floor are Bolitoglossa moreleti mulleri, Lepidophyma flavimaculatum

flavimaculatum, Scincella cherriei cherriei, Ninia sebae

sebae, Pliocercus euryzonus aequalis, and Micrurus affinis apiatus.

Other species of snakes that spend most of their lives above ground

often forage in the mulch layer; among these are Coniophanes

bipunctatus biserialis, Coniophanes fissidens fissidens, Coniophanes

imperialis clavatus, Lampropeltis doliata polyzona, and Stenorrhina

degenhardti. Among the amphibians, at least Hypopachus cuneus

nigroreticulatus, Eleutherodactylus rostralis, and Syrrhophus leprus are known to seek shelter in the mulch.

4. Terrestrial.—One turtle, Geoemyda areolata, is primarily

terrestrial. Among the lizards, conspicuous terrestrial species are Anolis humilis uniformis and Ameiva festiva edwardsi; Anolis

lemurinus bourgeaei and Basiliscus vittatus spend part of their

lives on the ground, but also live on trees and in bushes. Eumeces

schwartzei and E. sumichrasti apparently are terrestrial. The only

terrestrial lizard that is nocturnal is Coleonyx elegans elegans, which[216] by day hides in the leaf litter or below ground. Nocturnal amphibians

that are terrestrial include Bufo marinus, Bufo valliceps

valliceps, Eleutherodactylus rugulosus rugulosus, Syrrhophus leprus,

and Hypopachus cuneus nigroreticulatus. A large number of active

diurnal snakes are terrestrial; these include Boa constrictor imperator, Clelia clelia clelia, Dryadophis melanolomus laevis, Drymarchon

corais melanurus, Drymobius margaritiferus margaritiferus, Pseustes poecilonotus poecilonotus, and Spilotes pullatus mexicanus.

Nocturnal terrestrial snakes include three kinds of Bothrops (B.

atrox asper, B. nasutus, and B. nummifer nummifer), all of which

seem to be equally active by day.

5. Arboreal.—In this habitat the third dimension (height) of

the rainforest probably is the most complex insofar as the inter-relationships

of species and ecological niches are concerned. I

have attempted to categorize species as to microhabitats within

the arboreal habitat; in so doing, I recognize four subdivisions—bushes,

tree trunks, tree tops, and epiphytes.

Bush inhabitants include several species of lizards and snakes,

all of which have rather elongate, slender bodies, and long tails.

Common bush-inhabitants in southern El Petén are Anolis limifrons

rodriguezi, Basiliscus vittatus, Laemanctus deborrei, Leptophis

mexicanus mexicanus, and Oxybelis aeneus aeneus. All of these

are diurnal, and all but Laemanctus have been observed sleeping

on bushes at night.

Tree-trunk inhabitants include five species of lizards. Thecadactylus

rapicaudus lives on the trunks of large trees; Sphaerodactylus

lineolatus lives beneath the bark on dead trees and on

corozo palms. Anolis lemurinus bourgeaei lives on the bases and

buttresses of large trees, from which it often descends to the ground. Corythophanes cristatus and Anolis capito were found only on tree

trunks and large vines.

The least information is available for the species living in the

tree tops. The following species were obtained from tops of trees

when they were felled, or have been observed living in the tree

tops: Anolis biporcatus, Iguana iguana rhinolopha, Celestus rozellae, Leptodeira septentrionalis polysticta, Leptophis ahaetulla

praestans, Sibon dimidiata dimidiata, and Sibon nebulata nebulata.

Epiphytes, especially the bromeliads, provide refuge for a variety

of tree frogs and small snakes. Of the tree frogs, Hyla picta, Hyla

staufferi, Phyllomedusa callidryas taylori, Similisca baudini, and Similisca phaeota cyanosticta have been found in bromeliads; other[217] species probably occur there. Among the snakes, Imantodes

cenchoa leucomelas, Leptodeira frenata malleisi, Leptodeira

septentrionalis polysticta, Sibon dimidiata dimidiata, and Sibon

nebulata nebulata are frequent inhabitants of bromeliads; all of

these snakes are nocturnal.

Relationships of the Fauna

Most of the 78 species of amphibians and reptiles definitely

known from the rainforest in southern El Petén have extensive

ranges in the Atlantic lowlands of southern México and Central

America; many extend into South America. Sixty-two (80%) of the

species belong to this group having extensive ranges in Middle

America. Three species (Syrrhophus leprus, Leptodeira frenata,

and Kinosternon acutum) are at the southern limits of their distributions

in southern El Petén and northern Alta Verapaz, whereas Eleutherodactylus rostralis and Thecadactylus rapicaudus are at

the northern and western limits of their distributions in El Petén.

Nine (11%) species have the center of their distributions in El

Petén and the Yucatán Peninsula; representatives of this group

include Claudius angustatus, Dermatemys mawi, Laemanctus

deborrei, and Eumeces schwartzei.

In determining a measure of faunal resemblance, I have departed

from the formulae discussed by Simpson (1960) and have analyzed

the degree of resemblance by the following formula used to calculate

an index of faunal relationships:

C (2) / (N1 + N2) = R, where

C = species common to both faunas.

N1 = number of species in the first fauna.

N2 = number of species in the second fauna.

R = degree of relationships (when R = 1.00, the faunas are identical; when R = 0, the faunas are completely different).

The herpetofauna of southern El Petén has been compared with

that in the Tikal-Uaxactún area (Stuart, 1958), that in the humid

lowlands of Alta Verapaz (Stuart, 1950, plus additional data), and

that in the Mexican state of Yucatán (Smith and Taylor, 1945,

1948, and 1950). The herpetofaunas of lowland Alta Verapaz and

Yucatán are the largest, having respectively 94 and 91 species,

where as there are 78 species known from southern El Petén and

64 from the Tikal-Uaxactún area. An analysis of faunal relationships

(Table 2) shows that the faunas of the rainforests of southern

El Petén and lowland Alta Verapaz are closely related. The relationships

between these two areas and the Tikal-Uaxactún area[218] in northern El Petén is notably less. Apparently the biggest faunal

changes take place between southern El Petén and the Tikal-Uaxactún

area, and between the latter and Yucatán. As stated

by Stuart (1958:7) the Tikal-Uaxactún is transitional between the

humid rainforests to the south and the dry outer end of the Yucatán

Peninsula. The transitional nature of the environment is exemplified

by a rather depauperate herpetofauna consisting of some

species of both dry and humid environments and lacking a large

fauna typical of either. Contrariwise, the continuity of the environment

from southern El Petén to the lowlands of Alta Verapaz

is reflected in degree of resemblance of the herpetofaunas.

Table 2.—Index of Faunal Relationships Between Southern El Petén

and Other Regions.

| Lowland Alta Verapaz | Southern El Petén | Tikal- Uaxactún Area | Yucatán | |

| Lowland Alta Verapaz | .85 | .61 | .43 | |

| Southern El Petén | .85 | .64 | .41 | |

| Tikal-Uaxactún Area | .61 | .64 | .63 | |

| Yucatán | .43 | .41 | .63 |

Most of the species of amphibians and reptiles found in southern

El Petén are found in humid tropical forests from the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec southeastward on the Atlantic lowlands well into

Central America.

ACCOUNTS OF SPECIES

In the following pages various aspects of the occurrence, life

histories, ecology, and variation of the species of amphibians and

reptiles known from southern El Petén are discussed. Only Cochranella

fleischmanni reported by Stuart (1937) from Río Subín

at Santa Teresa was not collected by us and is excluded. Because

more worthwhile information was gathered for some species than

others, the length and completeness of the accounts vary. All

specimens listed are in the Museum of Natural History at the

University of Kansas, to which institution all catalog numbers refer.

Preceding the discussion of each species is an alphabetical list of[219] localities from which specimens were obtained; numbers after a

locality indicate the number of specimens obtained at each locality.

Bolitoglossa dofleini (Werner)

Chinajá, 1.

An adult female having minute ovarian eggs has a snout-vent

length of 81 mm., a tail length of 59 mm., 13 costal grooves, two

intercostal spaces between adpressed toes, 38-35 vomerine teeth

in irregular rows forming a broad arch from a point posterolaterad

to the internal nares to a point near the anterior edge of the

parasphenoid teeth, and 43-44 maxilliary-premaxillary teeth. In

life the dorsum was rusty brown with irregular black and orange

spots and streaks. The flanks were bluish gray with black in the

costal grooves and creamy tan flecks along the ventral edge of

the flank. The belly and underside of the tail were yellowish tan

with dark brown spots laterally. The limbs were orange proximally

and black distally; the pads of the feet were bluish black. The

dorsal and lateral surfaces of the tail were yellowish orange with

black spots. The iris was grayish yellow.

Stuart (1943:17) reported this species from Finca Volcán, Alta

Verapaz. He diagnosed his specimens as having 13 costal grooves

and two or three intercostal spaces between adpressed toes. He

stated that the vomerine teeth were about 12 in number and that

in life the dorsum was mottled gray and black, the sides gray and

brown, and the undersurfaces uniformly dark gray. These specimens

differ noticeably from the individual from Chinajá in the

number of vomerine teeth and in coloration.

In August, 1961, I obtained a specimen of Bolitoglossa dofleini at Finca Los Alpes, Alta Verapaz, approximately 13 kilometers

airline south-southwest of Finca Volcán and at approximately the

same elevation. Although the salamander was dead when found,

it obviously was more heavily pigmented than the individual from

Chinajá. The belly was bluish gray with black spots laterally;

the dorsum was dull brownish gray with some brownish red streaks.

The specimen is a female having small ovarian eggs, a snout-vent

length of 90 mm., 13 costal grooves, and two intercostal spaces

between adpressed limbs. There are 28-29 vomerine teeth, more

than twice as many as in specimens from Finca Volcán (Stuart,

1943:17), but noticeably fewer than in the specimen from Chinajá.

The presence of this species at Chinajá lends support to the idea

that the specimen from the Río de la Pasión listed by Brocchi[220] (1882:116) also is Bolitoglossa dofleini. Furthermore, the confirmed

presence of this species in the lowlands of El Petén suggests

that there may be genetic connection between B. dofleini in the

Alta Verapaz and B. yucatana in the Yucatán Peninsula. Bolitoglossa

yucatana differs from B. dofleini in having five intercostal

spaces between adpressed toes and in having a different color

pattern. Both are robust species having no close relationships to

other species of Bolitoglossa in northern Central America.

The specimen from Chinajá was found in water in the axil of

a large elephant-ear plant (Xanthosoma) by day in March. Its

stomach contained fragments of beetles and a large roach. The

natives did not know salamanders and had no name for them.

Bolitoglossa moreleti mulleri (Brocchi)

Chinajá, 2; Río San Román, 1.

One specimen is a female having a snout-vent length of 80 mm.,

a tail length of 82 mm., and a total length of 162 mm. It contains

63 large eggs, the largest of which has a diameter of about three

millimeters. This specimen has 13 costal grooves, four intercostal

spaces between adpressed toes, and 12-13 vomerine teeth. A

juvenile having a snout-vent length of 39 mm. and a tail length

of 33 mm. has 12 costal grooves, three intercostal spaces between

adpressed toes, and 8-8 vomerine teeth. In life these salamanders

were uniformly dull brownish black above with a dull creamy

yellow irregular dorsal stripe beginning on the occiput and continuing

onto the tail. There are no yellow or orange streaks or

flecks on the head or limbs. The specimen from the Río San Román

was taken from the stomach of a Pliocercus euryzonus aequalis and has not been studied in detail, because of its poor condition.

The present specimens show no tendency for the development

of a broad irregular dorsal band that encloses black spots or forms

irregular dorsolateral stripes, as is characteristic of B. moreleti

mexicanus, a subspecies that has been reported from La Libertad

(Stuart, 1935:35) and Piedras Negras (Taylor and Smith, 1945:545)

in El Petén, and from Xunantunich, British Honduras (Neill and

Allen, 1959:20).

Schmidt (1936:151) and Stuart (1943:13) found B. moreleti

mulleri in bromeliads at Finca Samac, Alta Verapaz. Taylor and

Smith's (1945:545) and Neill and Allen's (1959:20) specimens of B. moreleti mexicanus were obtained from bromeliads, but Neill

and Allen (loc. cit.) stated that the natives in British Honduras[221] said that they had found salamanders beneath rubbish on the forest

floor. My specimens were obtained from beneath logs on the

forest floor in the rainy season. Possibly in drier environments the

species characteristically inhabits bromeliads, at least in the dry

season.

Bufo marinus (Linnaeus)

Chinajá, 3; 10 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1; 11 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

During both visits to Chinajá this large toad was breeding in

a small permanent pond in the camp. During the day the toads

took refuge in crevices beneath the buildings or beneath large

boulders by the pond. At dusk from four to ten males congregated

at the pond and called. Tadpoles of this species were in the pond

in March and in July. One juvenile was found beneath a rock in

the forest, and another was on the forest floor by day.

The natives' name for this species and the following one is sapo.

Bufo valliceps valliceps Wiegmann

Chinajá, 52; Río San Román, 8; Sayaxché, 2; Toocog, 1.

This is one of the most abundant, or at least conspicuous,

amphibians inhabiting the forest. Breeding congregations were

found on February 24, March 2, March 11, and June 27. At these

times the toads were congregated at temporary ponds in the forest

or along small sluggish streams. Throughout the duration of both

visits to Chinajá individual males called almost nightly at the

permanent pond at the camp.

The variation in snout-vent length of 20 males selected at

random is 56.7 to 72.5 mm. (average, 64.8 mm.). Two adult females

have snout-vent lengths of 80.4 and 87.6 mm. In all specimens

the parotid glands are somewhat elongated and not rounded as in Bufo valliceps wilsoni (see Baylor and Stuart, 1961:199). My

observations on the condition of the cranial crests of the toads in

El Petén agree with the findings of Baylor and Stuart (op. cit.:198) in

that hypertrophied crests are usual in large females. In the shape

of the parotids and nature of the cranial crests the specimens from

El Petén are like those from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in

México. As I pointed out (1960:53), the validity of the subspecies Bufo valliceps macrocristatus, described from northern Chiapas by

Firschein and Smith (1957:219) and supposedly characterized by

hypertrophied cranial crests, is highly doubtful.

In the toads from El Petén the greatest variation is in coloration.

The dorsal ground-color varies from orange and rusty tan to

brown, yellowish tan, and pale gray. In some individuals the[222] flanks and dorsum are one continuous color, whereas in others a

distinct dorsolateral pale colored band separates the dorsal color

from dark brown flanks. In some individuals the venter is

uniform cream color, in others it bears a few scattered black spots,

and in still others there are many spots, some of which are fused

to form a black blotch on the chest. In breeding males the vocal

sac is orange tan. All specimens have a coppery red iris.

Aside from the breeding congregations, active toads were found

on the forest floor at night; a few were there by day. Some

individuals were beneath logs during the day.

Eleutherodactylus rostralis (Werner)

Chinajá, 10.

Because of the multiplicity of names and the variation in coloration,

the small terrestrial Eleutherodactylus in southern México and

northern Central America are in a state of taxonomic confusion.

Stuart (1934:7, 1935:37, and 1958:17) referred specimens from El

Petén to Eleutherodactylus rhodopis (Cope). Stuart (1941b:197)

described Eleutherodactylus anzuetoi from Alta Verapaz and El

Quiché, Guatemala, suggested that the new species was an upland

relative of Eleutherodactylus rostralis (Werner), and used that

name for the frogs that he earlier had referred to Eleutherodactylus

rhodopis. Dunn and Emlen (1932:24) placed E. rostralis in the

synonymy of E. gollmeri (Peters). Examination of series of these

frogs from southern México, Guatemala, and Costa Rica causes me

to think that there are four species; these can be distinguished as

follows:

E. rhodopis.—No web between toes; one tarsal tubercle; tibiotarsal articulation

reaches to nostril; iris bronze in life.

E. anzuetoi.—No web between toes; a row of tarsal tubercles; tibiotarsal

articulation reaches to tip of snout; color of iris unknown.

E. rostralis.—A vestige of web between toes; no tarsal tubercles; tibiotarsal

articulation reaches snout or slightly beyond; iris coppery red in life.

E. gollmeri.—A vestige of web between toes; no tarsal tubercles; tibiotarsal

articulation reaches well beyond snout; iris coppery red in life.

The presence of webbing between the toes, the absence of tarsal

tubercles, and the coppery red iris distinguish E. rostralis and E.

gollmeri from the other species. Probably E. rostralis and E. gollmeri are conspecific, but additional specimens are needed from Nicaragua

and Honduras to prove conspecificity. On the other hand, the characters

of the frogs from Chinajá clearly show that they are related

to E. gollmeri to the south and not to E. rhodopis to the north in

México.

At Chinajá, Eleutherodactylus rostralis was more abundant than[223] the few specimens indicate, for upon being approached the frogs

moved quickly and erratically, soon disappearing in the leaf litter

on the forest floor. Most of the specimens were seen actively moving

on the forest floor in the daytime; one was found beneath a rock,

and one was on the forest floor at night.

Eleutherodactylus rugulosus rugulosus (Cope)

Chinajá, 2; 15 km. NW of Chinajá, 4.

These frogs were found on the forest floor by day. With the exception

of one female having a snout-vent length of 69.5 mm., all are

juveniles. The apparent rarity of this species at Chinajá may be

due to the absence of rocky streams, a favorite habitat of this frog.

The local name for this frog is sapito, meaning little toad.

Leptodactylus labialis (Cope)

Toocog, 1.

One juvenile having a snout-vent length of 16.4 mm. was found

at night beside a pond in the forest. The scarcity of the species

of Leptodactylus in the southern part of El Petén probably is due

to the lack of permanent marshy ponds.

Leptodactylus melanonotus (Hallowell)

Sayaxché, 1.

One individual was found beneath a rock beside a stream in

the forest. The local name is ranita, meaning little frog.

Syrrhophus leprus Cope

Chinajá, 2; 15 km NW of Chinajá, 1.

An adult female having a snout-vent length of 27.5 mm. was

found on the forest floor by day. Two juveniles having snout-vent

lengths of 15.5 and 19.0 mm. were beneath rocks on the forest floor.

The specimens are typical of the species as defined by Duellman

(1958:8).

Hyla ebraccata Cope

Toocog, 66.

This small tree frog congregated in large numbers at a forest

pond at Toocog. Between June 30 and July 2 we collected specimens

and observed the breeding habits of this and other species

at the pond. Calling males were distributed around the pond, where

they called from low herbaceous vegetation at the edge of the pond

or from plants rising above the water. Calling commenced at dusk[224] and continued at least into the early hours of the morning. On one

occasion a female was observed at a distance of about 50 centimeters

away from a calling male sitting on a blade of grass. The

female climbed another blade of grass until she was about eight

centimeters away from the male, at which time he saw her, stopped

calling, jumped to the blade of grass on which she was sitting and

clasped her. Clasping pairs were observed on blades of grass and

leaves of plants above the water; most pairs were less than 50

centimeters above the surface of the pond.

The eggs are deposited on the dorsal surfaces of leaves above

the water. All eggs are in one plane (a single layer) on the leaf. External

membranes are barely visible, as the eggs consist of a single

coherent mass. Eggs in the yolk plug stage have diameters of 1.2

to 1.4 mm. Seventeen eggs masses were found; these contained from

24 to 76 (average 44) eggs. The jelly is extremely viscous and tacky

to the touch. At time of hatching the jelly becomes less viscous;

the tadpoles wriggle until they reach the edge of the leaf and drop

into the water.

Eleven tadpoles were preserved as they hatched; these have total

lengths of 4.5 to 5.0 (average 4.77) mm. Hatchling tadpoles are

active swimmers and have only a small amount of yolk. The largest

tadpoles preserved have total lengths of 13.0 and 13.5 mm. At

this size distinctive sword-tail and bright coloration have developed.

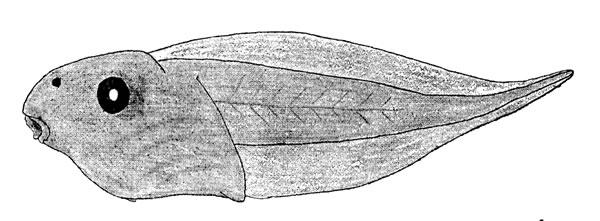

Fig. 2. Tadpole of Hyla ebraccata (KU 59986) from

Fig. 2. Tadpole of Hyla ebraccata (KU 59986) fromToocog, El Petén, Guatemala.

Description of fully developed tadpole (KU 59986): Total

length, 13.5 mm.; tail-length, 8.4 mm., 62 per cent of total length.

Snout, in dorsal view, bluntly rounded; in lateral view less bluntly

rounded; body depressed; head flattened; mouth terminal; eye large,

its diameter 25 per cent of length of body; nostrils near tip of

snout and directed anteriorly; spiracle sinistral and situated postero-ventrad

to eye; cloaca median. Tail-fin thrice depth of tail-musculature,

which extends beyond posterior end of tail-fin giving

sword-tail appearance (Fig. 2). In life, black stripe on each side

of body and on top of head; black band on anterior part of tail[225] and another on the posterior part; body and anterior part of tail

creamy yellow; dark red band between black bands on tail. Mouth

terminal, small, its width about one-fifth width of body; fleshy ridge

dorsally and ventrally; row of small papillae on ventral lip; no lateral

indentations of lips; upper beak massive, convex, and finely serrate;

lower beak small and mostly concealed behind upper; no teeth

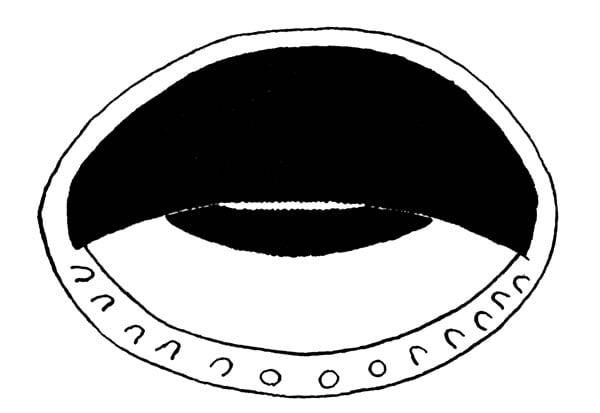

(Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Mouthparts of larval Hyla ebraccata (KU

Fig. 3. Mouthparts of larval Hyla ebraccata (KU59986) from Toocog, El Petén, Guatemala.

Hyla loquax Gaige and Stuart

Toocog, 14.

These specimens were found at night when they were calling from

low vegetation in a forest pond. Most of the frogs were several

meters away from the edge of the pond. Although two clasping

pairs were found, we obtained no eggs or tadpoles referable to

this species.

Hyla microcephala martini Smith

Chinajá, 1; Toocog, 21.

The specimen from Chinajá was calling from a small bush at the

edge of a temporary grassy pond in a clearing in the forest. At

Toocog this species was closely associated with Hyla ebraccata;

males were calling from herbaceous vegetation in and around the

forest pond. These frogs were not so abundant in the forest at

Toocog as they were around ponds on the savanna at La Libertad.

[226]

Hyla picta (Günther)

Toocog, 8.

This small tree frog was calling from herbs in a pond in the

forest on June 30 and July 2. The voice is weak; probably greater

numbers of males were present than are indicated by the few

specimens collected, for the din from the more vociferous species

made it impossible to hear Hyla picta unless one was calling

close by.

Hyla staufferi Cope

Chinajá, 1.

This individual was calling from a low bush in the clearing at

Chinajá. None was found in the pond in the forest at Toocog.

Stuart (1935:38) and Duellman (1960:63) noted that Hyla staufferi breeds early in the rainy season. Nevertheless, I think early breeding

habits do not account for the near absence of this species in

our collections from southern El Petén. In early July, 1960, a few

individuals were heard at a pond on the savanna at La Libertad. In

mid-July of the same year they were calling sporadically from

temporary ponds in the lower Motagua Valley. Possibly the individual

collected at Chinajá was accidentally transported there in

cargo from Toocog, from which camp at the edge of the savanna

planes fly to Chinajá weekly. My observations on this species

throughout its range in México and Central America indicate that it

inhabits savannas and semi-arid forests and usually is absent

from heavy rainforest. Stuart (1948:34) obtained this species at

Cubilquitz in the lowlands of Alta Verapaz.

Phyllomedusa callidryas taylori Funkhouser

Toocog, 25.

Between June 30 and July 2 this species was abundant at a pond

in the forest at Toocog. Calling males were as high as five meters

in bushes and trees around the pond. At dusk males were observed

descending a vine-covered tree at the edge of the pond; this

strongly suggests that the frogs retreat to this tree and others like

it for diurnal seclusion. Clasping pairs were found on branches

and leaves above the water. The eggs are deposited in clumps

usually on vertical leaves, but sometimes on horizontal leaves or

on branches, vines, and aerial roots above the water. Twenty-six

clutches of eggs contained from 14 to 44 (average 29) eggs. In

a clutch in which the eggs are in yolk plug stage the average

diameter of the embryos is 2.3 mm. and that of the vitelline[227] membranes, 3.4 mm. Most of the eggs are in the external part

of the gelatinous mass; the jelly is clear. The yolk is pale green,

and the animal pole is brown. As development ensues, the yolk

becomes yellow and the embryo first dark brown and then pale

grayish tan. Upon hatching the tadpoles wriggle free of the

jelly and drop into the water. One clutch of 19 eggs was observed

to hatch in three minutes. Apparently, on dropping into the

water the hatchling tadpoles go to the bottom of the pond, for one

or two minutes pass from the time they enter the water until they

reappear near the surface. The average total length of seven

hatchling tadpoles is 7.4 mm. There is a moderate amount of

yolk, but this does not form a large ventral bulge. Large tadpoles

congregate in the sunny parts of the pond, where they were observed

just beneath the surface. Many had their mouths at the

surface. Except for constant fluttering of the tip of the tail, they

lie quietly with the axis of the body at an angle of about 45 degrees

with the surface of the water.

Description of tadpole (KU 60006): total length, 24.5 mm.; tail-length,

15.4 mm.; body broader than deep; head moderately flattened;

snout viewed from above blunt; nostrils close to snout and

directed dorsally; eyes of moderate size and directed laterally; mouth

directed anteroventrally; anus median; spiracle ventral, its opening

just to left of midline slightly more than one-half distance from tip

of snout to vent. Tail-fin slightly more than twice as deep as tail

musculature, which curves upward posteriorly; tail-fin narrowly

extending to tip of tail (Fig. 4). Color in life pale gray; in preservative

white with scattered melanophores; tail-fin transparent.

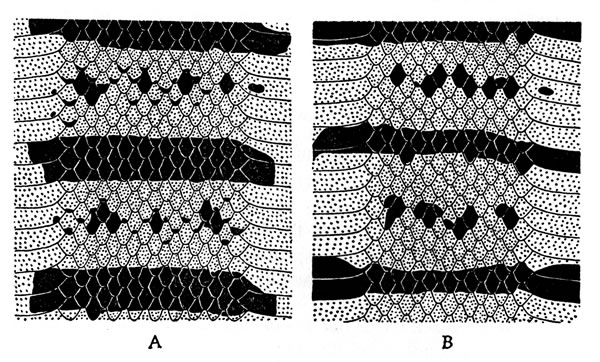

Fig. 4. Tadpole of Phyllomedusa callidryas taylori (KU 60006) from

Fig. 4. Tadpole of Phyllomedusa callidryas taylori (KU 60006) fromToocog, El Petén, Guatemala.

Upper lip having single row of papillae laterally, but none

medially; lower lip having single row of papillae; no lateral

indentation of lips; two or more rows of papillae at lateral corners

of lips; tooth-rows 2/3; second upper tooth row as long as first,

interrupted medially; inner lower tooth-row as long as upper rows,[228] interrupted medially; second and third lower rows decreasingly

shorter; upper beak moderate in size and having long lateral projections;

lower beak moderate in size; both beaks finely serrate

(Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Mouthparts of larval Phyllomedusa callidryas taylori (KU

Fig. 5. Mouthparts of larval Phyllomedusa callidryas taylori (KU60006) from Toocog, El Petén, Guatemala.

Smilisca baudini (Duméril and Bibron)

Chinajá, 9; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 42; Río de la Pasión, 1; Río San

Román, 5; Sayaxché; Toocog, 2.

Individuals of this species were found at night sitting on bushes

and small trees in the forest in February and March and again in

June and July. One was in the axil of a leaf of a Xanthosoma. In

June and July males were heard nearly every night. The series of

specimens from 20 kilometers north-northwest of Chinajá was taken

from a breeding congregation in a shallow muddy pool in the

forest. Tadpoles of this species were in small, often muddy pools

in the forest. To my knowledge Smilisca baudini is the only hylid

to breed in these pools at Chinajá, although perhaps Smilisca

phaeota also utilizes them. The only other amphibian at Chinajá

known to breed in the pools is Bufo valliceps valliceps. Although

two specimens were on bushes at night at Toocog, Smilisca

baudini was not present at the pond where five other species of

hylids were breeding. Nevertheless, Smilisca baudini was calling

from two ponds on the savannas near La Libertad. All of the

specimens from southern El Petén have yellow or yellowish white

flanks and ventrolateral surfaces.

[229]

Smilisca phaeota cyanosticta (Smith)

Chinajá, 4; 10 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

All specimens were found in February and March. Those from

Chinajá were obtained from Xanthosoma and bromeliads; the

individual from 10 kilometers north-northwest of Chinajá is an

adult male that was calling from a puddle in a fallen tree on

March 13. A juvenile having a snout-vent length of 34.7 mm. lacks

the pale blue spots on the thighs; instead, the anterior and posterior

surfaces of the thighs are bright red.

Hypopachus cuneus nigroreticulatus Taylor

Toocog, 1.

An adult male having a snout-vent length of 41.7 mm. was found

at night on the forest floor at the edge of a temporary pond. In

life the dorsum was dark brown with chocolate brown markings;

the stripe on the side of the head was white; the middorsal stripe

was pale orange; the belly was black and white, and the iris was

a bronze color.

Characteristically this species inhabits savannas and open forest;

thus, its occurrence in the rainforest at Toocog is surprising. This is

the southernmost record for the species in El Petén; to the south in

the highlands it is replaced by the smaller Hypopachus inguinalis,

having rounded, instead of compressed, metatarsal tubercles.

Rana palmipes Spix

Chinajá, 11; 15 km. NW of Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

With the exception of one recently metamorphosed juvenile having

a snout-vent length of 30.7 mm. that was found on the forest floor

by day on June 24, and one that was found beside a pool in a cave,

all individuals were found at temporary woodland pools or along

sluggish streams at night. The largest specimen is a female having

a snout-vent length of 107 mm.

Rana pipiens Schreber

Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1; Río San Román, 1; Toocog, 1.

All specimens were found near water at night. The largest individual

is a female having a snout-vent length of 112.5 mm.

Crocodylus moreleti Duméril and Duméril

Chinajá, 1; Río San Román, 1.

One specimen was obtained from a quiet pool in the Río San[230] Román at night; another was found in a small sluggish stream at

Chinajá. Two large individuals were seen in tributaries to the Río

San Román. On the savannas at Toocog two small individuals were

obtained in the dry season, at which time the crocodiles apparently

were migrating to water. The local name for this species is lagarto.

Chelydra rossignoni (Bocourt)

Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

The paucity of specimens of Chelydra from Central America has

resulted in rather inadequate diagnoses of various populations. The

present specimens have carapace lengths of 250 and 238 mm. and

plastral lengths of 185 and 176 mm. The length of carapace/bridge

ratio is 6.0 and 6.1 per cent. Each individual has four barbels, the

median pair of which are extremely long. In KU 55977 the lateral

pair of barbels is forked at the base. The relative length of the

plastral bridge in these specimens compares favorable with the

ratio (.06-.08) given by Schmidt (1946:4) for five specimens from

Honduras. Chelydra serpentina, which may occur sympatrically

with C. rossignoni in some parts of Central America, has a narrower

plastral bridge and only two barbels beneath the chin. Furthermore, C. rossignoni and C. osceola in Florida have long, flat tubercles

on the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the neck, whereas C.

serpentina has short, round tubercles.

The specimen from Chinajá was found in a small sluggish stream;

the other individual was in a muddy pool in the forest. The local

name is sambodanga.

Claudius angustatus Cope

20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

One specimen was unearthed from the bank of a small muddy

stream by a bulldozer. This individual represents the second

record for the species in Guatemala; the first was provided by

specimens, likewise found in muddy waters, at Tikal (Stuart,

1958:19). The local name is caiman.

Kinosternon acutum Gray

20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 4; 30 km. NNW of Chinajá, 2.

These turtles were found on the forest floor, in small sluggish

streams, and in pools in the forest. One adult male had, in life,

the top of the head yellow with black spots; the stripes on the

head and neck were red. Specimens were obtained both in the dry[231] and rainy seasons. The local name for both species of Kinosternon is pochitoque.

Kinosternon leucostomum Duméril and Bibron

Chinajá, 3; 15 km. NW of Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 2.

Individuals of this turtle were found on the forest floor and in

small sluggish streams. In life most specimens had a tan or

pale brown head with pinkish tan stripes on the head and neck.

All individuals were obtained in February and March. No ecological

differences between this species and K. acutum were evident.

Staurotypus triporcatus (Wiegmann)

Paso Subín, 1.

This species is represented in the collection by one complete

shell found on the bank of the Río Subín. The carapace has a

length of 292 mm. The local name is Guao. Natives stated that

this turtle was not uncommon in clear rivers and lakes, a habitat

suggested for the species by Stuart (1958:19).

Dermatemys mawi Gray

Chinajá, 1; Río San Román, 4.

The record from Chinajá is based on a carapace found in a

chiclero camp, where the turtle evidently had been brought for

food. The four specimens from the Río San Román were obtained

from edges of deep pools in clear water. In adult males the top

of the head was reddish orange in life. One of the specimens from

the Río San Román currently is living in the Philadelphia Zoological

Gardens. The local name for this turtle is tortuga blanca; it is

sought for its meat.

Geoemyda areolata (Duméril and Bibron)

Chinajá, 2.

Two specimens were obtained from dense forest at Chinajá.

The local name is mojina.

Pseudemys scripta ornata (Gray)

Paso Subín, 1.

One subadult was obtained from clear water in the Río Subín.

The stripes on the head and neck were yellow; there was no red

"ear" on the side of the head. The stripes on the forelimbs were

orange, and the ocelli on the carapace were red. The local name

is jicotea.

[232]

Coleonyx elegans elegans Gray

Toocog, 1.

One adult male having a snout-vent length of 89 mm. was found

beneath a log in the forest. Locally this gecko is known as escorpión; the natives believe it to be deadly poisonous. The use

of the name escorpión seems to be restricted to lizards thought to

be venomous. Nearly everywhere in México and Central America

some species of lizard carries this appellation. In El Petén I heard

the name used only for Coleonyx elegans and Thecadactylus rapicaudus;

in the lowlands of Guerrero, México, the name is applied

to geckos of the genus Phyllodactylus. The venomous lizards of

the genus Heloderma in the lowlands of western México are called escorpiónes. In the mountains of southern México various skinks

of the genus Eumeces, as well as lizards of the genus Xenosaurus,

carry the same appellation. Abronia in the mountains of México

and Gerrhonontus throughout México and Central America likewise

are called escorpiónes. Although many people in various parts of

Middle America consider most lizards poisonous, there is a unanimity

of opinion concerning the venomous qualities of the various

kinds of escorpiónes. I know of only two other lizards in Middle

America that are so uniformly regarded in native beliefs; these

are Enyaliosaurus clarki in the Tepalcatepec Valley in Michoacán,

called nopiche, and Phrynosoma asio in western México, called cameleón.

Sphaerodactylus lineolatus Lichtenstein

15 km. NW of Chinajá, 1; Toocog, 1.

These small geckos were much more abundant than the few specimens

indicate. They frequently were seen on the trunks of corozo

palms, where they quickly took refuge in crevices at the bases of

the fronds. The specimen obtained at Toocog was under the bark

of a standing dead tree. In life the ventral surface of the tail was

orange. The individual from Chinajá was in the leaf litter on the

ground at the base of a dead tree.

Thecadactylus rapicaudus (Houttuyn)

15 km. NW of Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 2.

Two specimens were found beneath the bark of standing dead

trees; another was found in the crack in the trunk of a mahogany

tree about 13 meters above the ground. In life the dorsum was[233] yellowish tan with dark brown markings; the venter was yellowish

tan with brown flecks, and the iris was olive-tan. The largest specimen

is a male having a snout-vent length of 95 mm.; all specimens

have regenerated tails. Individuals when caught twisted their

bodies and attempted to bite; upon grabbing a finger they held

on with great tenacity.

Anolis biporcatus (Wiegmann)

14 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1; 17 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of

Chinajá, 3; 30 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1; Sayaxché, 1.

All specimens of this large anole were obtained from trees.

Some individuals were found in the tops of trees immediately after

they were felled. My limited observations on this anole suggest

that it is an inhabitant of the upper levels of the forest. In life an

adult male from 20 kilometers north-northwest of Chinajá was

brilliant green above; the eyelids were bright yellow; the belly was

white. The outer part of the dewlap was pale orange, and the

median part was pinkish blue. A juvenile having a snout-vent length

of 47 mm. and a tail length of 86 mm. was pale grayish green with

pale gray flecks on the dorsum. The largest male has a snout-vent

length of 98 mm. and a tail length of 217 mm.; the same measurements

of the largest female are 89 and 213 mm. This species, together

with all other anoles, is known locally as toloque.

Anolis capito Peters

Chinajá, 2; 14 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1; Río de la Pasión, 1.

All individuals were observed on trunks of trees between heights

of three and ten meters above the ground. The largest male has a

snout-vent length of 81 mm. and a tail length of 155 mm.; the same

measurements of the largest female are 87 and 150 mm. The

streaked brown dorsum, combined with the lizards' habit of pressing

the body against the trunks of trees, make this anole especially difficult

to see.

Anolis humilis uniformis Cope

Chinajá, 24; 15 km. NW of Chinajá, 22; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 6;

Sayaxché, 1.

This small dull brown anole is a characteristic inhabitant of the

forest floor, where the lizards move about in a series of quick,

short hops and thus easily evade capture. Three individuals were

found on small bushes, and four were on the bases of trees; otherwise,

all were observed on the ground. Observations indicate that[234] this species is active throughout the day, except during and immediately

after heavy rains. The males have a deep red dewlap

with a dark blue median spot.

Anolis lemurinus bourgeaei Bocourt

Chinajá, 11; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 4; 30 km. NNW of Chinajá, 2;

Río de la Pasión, 1; Río San Román, 1; Sayaxché, 8; Toocog, 6.

This moderate-sized anole characteristically inhabits the low

bushes and bases of trees in the forest. Individuals were most

readily observed on the buttresses of some of the gigantic mahogany

and ceiba trees. When approached the lizards usually ran around

the tree or ducked to the other side of the buttress; if the observer

moved closer, they jumped to the ground and ran off. None was

observed to ascend large trees. Some individuals were observed

foraging on the forest floor; these took shelter on the bases of

trees. One individual was sleeping on a palm frond at night. The

adult males have a uniformly orange-red dewlap.

Anolis limifrons rodriguezi Bocourt

15 km. NW of Chinajá, 2; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

In dry forests and more open situations than occur at Chinajá

this little anole is abundant, but in the wet forests of southern El

Petén, only three specimens were found. Two were on palm

fronds about two meters above the ground; the other was on a low

bush. I suspect that ecologically this species overlaps A. humilis

uniformis and A. lemurinus bourgeaei, but too few observations are

recorded to justify a definite statement at this time.

Anolis sericeus sericeus Hallowell

Chinajá, 2; Sayaxché, 1; Toocog, 1.

This small anole is common and widespread in the Atlantic

lowlands of southern México and northern Central America; usually

it inhabits sub-humid regions. Consequently, its presence in the

wet forests of southern El Petén was unexpected. The specimens

from Chinajá were sleeping on low bushes at night, whereas the

others were found on bushes by day.

Basiliscus vittatus Wiegmann

Chinajá, 6; Río de la Pasión, 1; Río San Román, 1; Sayaxché, 3; Toocog, 1.

Individuals of this abundant species were most frequently seen in

dense bushes along the margins of rivers or small streams. None

was observed far from water. These lizards, like the anoles, are

known locally as toloque.

[235]

Corythophanes cristatus (Merrem)

Chinajá, 3; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

Three individuals were found on tree trunks; the fourth was on

a thick vine about one meter above the ground. The two largest

males have snout-vent lengths of 121 and 115 mm. and tail lengths

of 265 and 243 mm. The largest female (KU 59603), obtained on

June 28, has a snout-vent length of 125 mm. and a tail length of

247 mm. This individual contained eight ova varying in greatest

diameter from 10.6 to 12.2 (average 11.1) mm. Also present are

numerous ovarian eggs having diameters up to about 3.5 mm.

One of the large males displayed a defensive behavior prior to

capture. When first observed the lizard was clinging to a tree

trunk about one and one-half meters above the ground. When I

approached, the lizard turned its flanks towards me; then it flattened

the body laterally, extended the dewlap, opened its mouth, and

made short rushing motions. When touched it bit viciously. On

the ground these lizards have a rather awkward bipedal gait that

is much slower than in Basiliscus vittatus.

In life an adult male (KU 55804) was reddish brown dorsally

with dark chocolate brown markings; the venter was creamy white,

and the iris was dark red. The natives call this lizard piende jente.

Iguana iguana rhinolopha Wiegmann

Río San Román, 2.

The iguana, as this lizard is called locally, seems to be uncommon

in the forested areas of southern El Petén. Possibly this is due to

the fact that the flesh of this lizard is relished as food by the natives.

My two specimens were in large trees at the edge of the river.

Laemanctus deborrei Boulenger

Chinajá, 1; Toocog, 5.

On June 26 a female having a snout-vent length of 129 mm.

and a tail length of 502 mm. was found on a bush in the forest.

The lizard, when approached, faced the collector and opened its

mouth. In life the dorsum was bright green; the lateral stripe

was white, and the iris was yellowish brown. This specimen contained

four ova having lengths of 13.4 to 14.2 (average 13.9) mm.

On June 30 at Toocog five white-shelled eggs were found in a

rotting log. Measurements of the eggs are—length, 23.5 to 25.0

(average 24.2) mm.; width, 15.0 to 15.5 (average 15.4) mm. These

eggs hatched on August 30. The five young had snout-vent lengths[236] of 43 to 45 (average 44) mm., and tail lengths of 137 to 140 (average

138) mm. In life the hatchlings had a dull dark green dorsum,

pale bright green venter and stripes on head, and reddish brown

iris. In preservative the hatchlings are creamy tan above with

five or six square dark brown blotches middorsally.

The natives consider this lizard to be one of the anoles; consequently,

it is known as toloque.

Lepidophyma flavimaculatum flavimaculatum Duméril

Chinajá, 8; 15 km. NW of Chinajá, 2.

Individuals were found beneath logs on the forest floor or moving

about in the litter on the forest floor. One was observed crawling

across a trail during a heavy rain. In some adults the tan dorsal

spots are large and distinct; in others the spots are small and indistinct.

Two juveniles, apparently recent hatchlings, were found

on June 28 and July 5. These specimens have snout-vent lengths

of 29 mm. and tail lengths of 38 and 41 mm.

Eumeces schwartzei Fischer

Chinajá, 1.

One specimen (KU 59551) was found on the forest floor at midday;

it is an adult female having a snout-vent length of 125 mm.

and a tail length of 210 mm. This specimen is larger than those recorded

by Taylor (1936:99) and extends the known range of the

species south of Ramate, approximately 125 kilometers south-south-westward

to Chinajá.

Eumeces sumichrasti (Cope)

20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

One adult male having a snout-vent length of 82 mm. was found

beneath a palm frond on the forest floor. In life the dorsum was

dull brown; the chin was cream; the belly was yellow, and the underside

of the tail was orange. A juvenile having a black body, yellow

dorsal stripes, and a bright blue tail was observed on the forest floor.

Scincella cherriei cherriei (Cope)

Chinajá, 2; 30 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1; Toocog, 1.

All individuals of this lizard were found in the leaf litter on the

forest floor; many escaped capture. In life the tail is dull bluish

gray. The number of dorsal scales varies from 59 to 61 (average[237] 60); thus, these specimens fall within the range of variation of S.

cherriei cherriei, and thereby differ from S. cherriei stuarti to the

west and S. cherriei ixbaac to the north.

Ameiva festiva edwardsi Bocourt

Chinajá, 16; 15 km. NW of Chinajá, 10; Sayaché, 4; Toocog, 1.

This abundant terrestrial lizard, locally called lagartijo, is found

throughout the forest. A juvenile obtained on March 14 at Sayaxché

has a snout-vent length of 42 mm. and a prominent umbilical scar.

Other juveniles were observed at Chinajá in February and March,

thereby indicating that the young probably hatch in the early part

of the year. Juveniles have bright blue tails.

Celestus rozellae Smith

20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 2.

Two specimens were obtained from trees by workmen in

February. These lizards have snout-vent lengths of 70 and 83 mm.

and tail lengths of 133 and 135 mm. There are 21 and 23 lamellae

beneath the fourth toe; each has 31 longitudinal rows of scales

around the body.

Boa constrictor imperator Daudin

15 km. NW of Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 2; Toocog, 1.

All specimens were found on the forest floor. One individual

was found in combat with a large Drymarchon corais melanurus.

Apparently, the Drymarchon was attempting to devour the Boa,

which had a total length of 1683 mm. Locally this snake is called masacuata; it is one of the few snakes believed by the local inhabitants

to be non-poisonous.

Clelia clelia clelia Daudin

15 km. NW of Chinajá, 1; 20 km. NNW of Chinajá, 1.

One specimen is represented only by the head; the snake was

killed on the forest floor by workmen. Another individual was

found in a pool of water at the base of a limestone outcropping in

the forest; this specimen (KU 58167) is a female having a body

length of 2220 mm. and a total length of 2634 mm. This snake

contained 22 ova averaging 56 × 23 mm. Both specimens were

uniform shiny black above and cream-color below. The local name

is sumbadora.

[238]

Coniophanes bipunctatus bipunctatus (Günther)

Chinajá, 1.

This snake was found on the forest floor by day; it is a male

having 130 ventrals, an incomplete tail; cream-colored belly, and a

pair of large brown spots on each ventral scute.

Coniophanes fissidens fissidens (Günther)

Toocog, 1.

This male specimen was found beneath a rock in a sink hole.

It has 122 ventrals and 77 caudals. A narrow temporal stripe

extends along the upper edge of the anterior temporal and the

lower edge of the upper secondary temporal. The belly is ashy