The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Woodpeckers

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Woodpeckers

Author: Fannie Hardy Eckstorm

Release date: January 25, 2011 [eBook #35062]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Steve Read and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WOODPECKERS ***

cover

[i]

[ii]

THE WOODPECKERS

BY

FANNIE HARDY ECKSTORM

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1901

[iii]

COPYRIGHT, 1900, BY FANNIE HARDY ECKSTORM

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

[iv]

To

MY FATHER

MR. MANLY HARDY

A Lifelong Naturalist

[vi]

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| Foreword: the Riddlers | 1 | |

| I. | How to know a Woodpecker | 4 |

| II. | How the Woodpecker catches a Grub | 9 |

| III. | How the Woodpecker courts his Mate | 15 |

| IV. | How the Woodpecker makes a House | 20 |

| V. | How a Flicker feeds her Young | 24 |

| VI. | Friend Downy | 28 |

| VII. | Persona non Grata. (Yellow-bellied Sapsucker) | 33 |

| VIII. | El Carpintero. (Californian Woodpecker) | 46 |

| IX. | A Red-headed Cousin. (Red-headed Woodpecker) | 55 |

| X. | A Study of Acquired Habits | 60 |

| XI. | The Woodpecker’s Tools: His Bill | 68 |

| XII. | The Woodpecker’s Tools: His Foot | 77 |

| XIII. | The Woodpecker’s Tools: His Tail | 86 |

| XIV. | The Woodpecker’s Tools: His Tongue | 99 |

| XV. | How each Woodpecker is fitted for his own Kind of Life | 104 |

| XVI. | The Argument from Design | 110 |

| APPENDIX | 113 | |

| A. | Key to the Woodpeckers of North America | 114 |

| B. | Descriptions of the Woodpeckers of North America | 117 |

[viii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Flicker (colored) | Frontispiece |

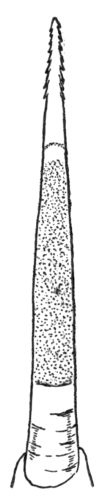

| Boring Larva | 10 |

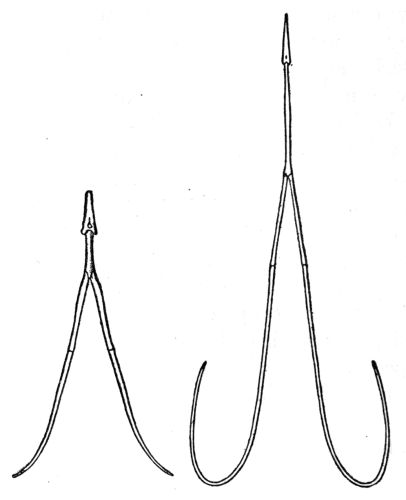

| Indian Spear | 12 |

| Solomon Islander’s Spear | 13 |

| Downy Woodpecker (colored) | facing 28 |

| Bark showing Work of Sapsucker | 34 |

| Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (colored) | facing 34 |

| Trunk of Tree showing Work of Californian Woodpecker | 47 |

| Californian Woodpecker (colored) | facing 48 |

| Red-headed Woodpecker (colored) | facing 56 |

| Head of the Lewis’s Woodpecker | 59 |

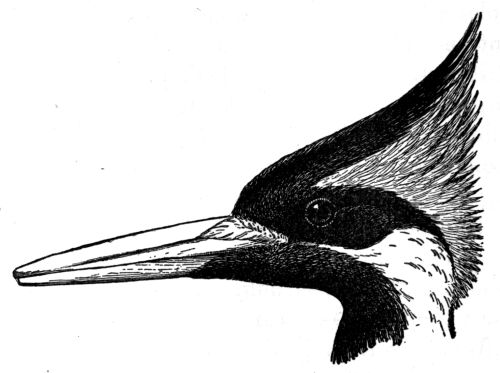

| Head of Ivory-billed Woodpecker | 70 |

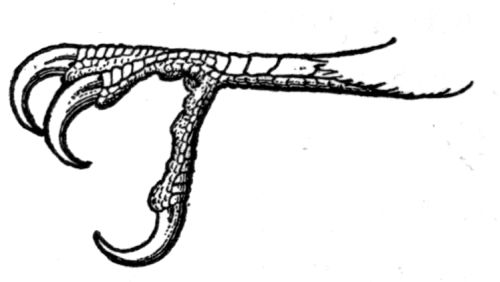

| Foot of Woodpecker | 77 |

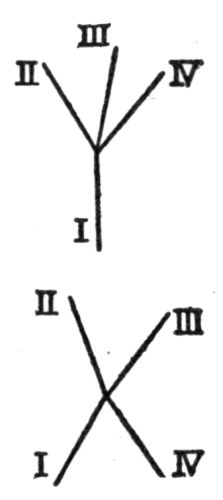

| Diagram of Right Foot | 79 |

| Foot of Three-toed Woodpecker | 80 |

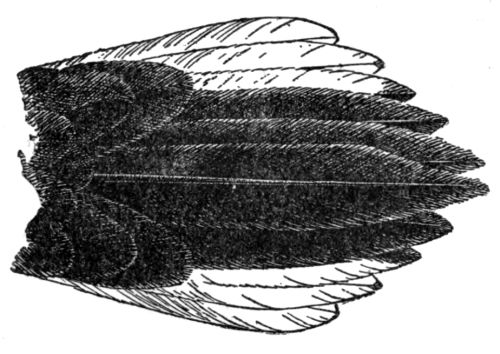

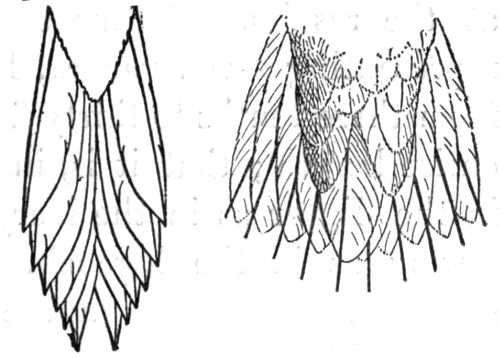

| Tail of Hairy Woodpecker | 86 |

| Tails of Brown Creeper and Chimney Swift | 87 |

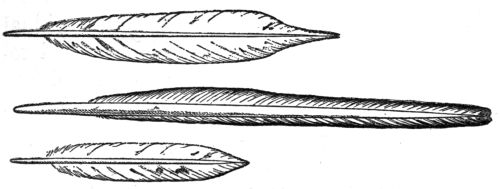

| Middle Tail Feathers of Flicker, Ivory-billed Woodpecker, and Hairy Woodpecker | 89 |

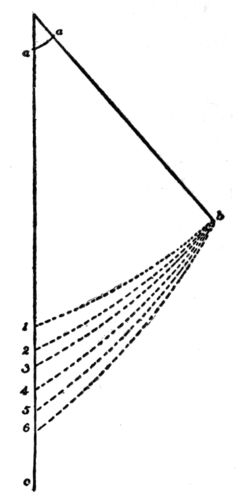

| Diagram of Curvature of Tails of Woodpeckers | 90 |

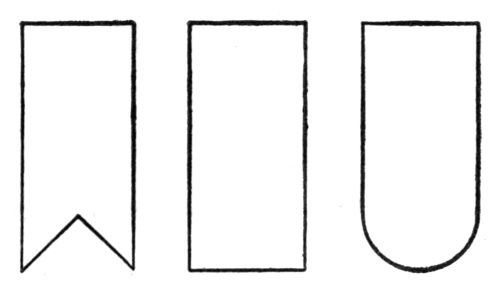

| Patterns of Tails | 91 |

| Under Side of Middle Tail Feather of Ivory-billed Woodpecker | 97 |

| Tongue of Hairy Woodpecker | 99 |

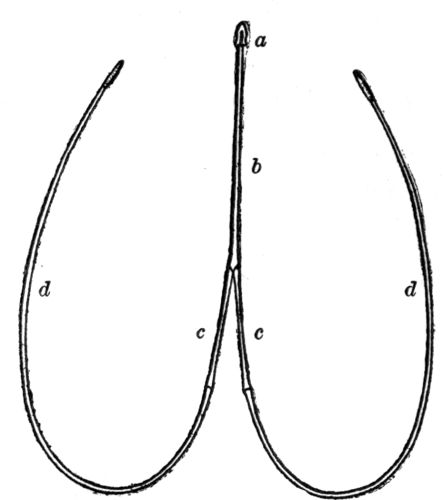

| Tongue-bones of Flicker | 100 |

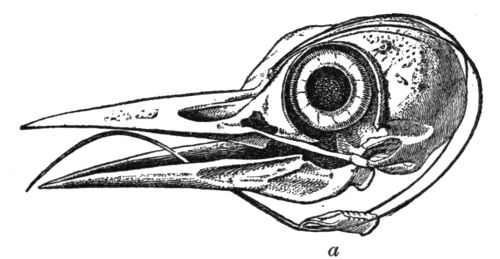

| Skull of Woodpecker, showing Bones of Tongue | 101 |

| Hyoids of Sapsucker and Golden-fronted Woodpecker | 102 |

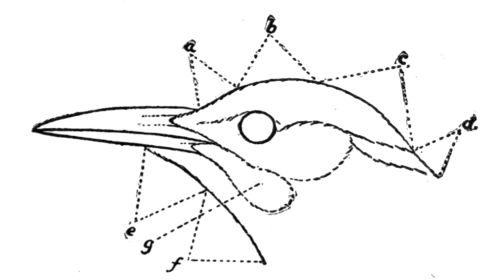

| Diagram of Head of a Flicker | 113 |

The colored illustrations are by Louis Agassiz Fuertes. The text

cuts are from drawings by John L. Ridgway.

[1]

THE WOODPECKERS

FOREWORD: THE RIDDLERS

Long ago in Greece, the legend runs, a terrible

monster called the Sphinx used to waylay

travelers to ask them riddles: whoever could not

answer these she killed, but the man who did

answer them killed her and made an end of her

riddling.

To-day there is no Sphinx to fear, yet the

world is full of unguessed riddles. No thoughtful

man can go far afield but some bird or

flower or stone bars his way with a question

demanding an answer; and though many men

have been diligently spelling out the answers

for many years, and we for the most part must

study the answers they have proved, and must

reply in their words, yet those shrewd old riddlers,

the birds and flowers and bees, are always

ready for a new victim, putting their heads together

over some new enigma to bar the road

to knowledge till that, too, shall be answered;[2]

so that other men’s learning does not always

suffice. So much of a man’s pleasure in life, so

much of his power, depends on his ability to

silence these persistent questioners, that this little

book was written with the hope of making

clearer the kind of questions Dame Nature asks,

and the way to get correct answers.

This is purposely a little book, dealing only

with a single group of birds, treating particularly

only some of the commoner species of that

group, taking up only a few of the problems

that present themselves to the naturalist for solution,

and aiming rather to make the reader

acquainted with the birds than learned about

them.

The woodpeckers were selected in preference

to any other family because they are patient

under observation, easily identified, resident in

all parts of the country both in summer and in

winter, and because more than any other birds

they leave behind them records of their work

which may be studied after the birds have

flown. The book provides ample means for identifying

every species and subspecies of woodpecker

known in North America, though only

five of the commonest and most interesting

species have been selected for special study.

At least three of these five should be found in[3]

almost every part of the country. The Californian

woodpecker is never seen in the East, nor

the red-headed in the far West, but the downy

and the hairy are resident nearly everywhere,

and some species of the flickers and sapsuckers,

if not always the ones chosen for special notice,

are visitors in most localities.

Look for the woodpeckers in orchards and

along the edges of thickets, among tangles of

wild grapes and in patches of low, wild berries,

upon which they often feed, among dead trees

and in the track of forest fires. Wherever there

are boring larvæ, beetles, ants, grasshoppers, the

fruit of poison-ivy, dogwood, june-berry, wild

cherry or wild grapes, woodpeckers may be confidently

looked for if there are any in the neighborhood.

Be patient, persistent, wide-awake, sure

that you see what you think you see, careful to

remember what you have seen, studious to compare

your observations, and keen to hear the

questions propounded you. If you do this seven

years and a day, you will earn the name of Naturalist;

and if you travel the road of the naturalist

with curious patience, you may some day become

as famous a riddle-reader as was that OEdipus, the

king of Thebes, who slew the Sphinx.[4]

I

HOW TO KNOW A WOODPECKER

The woodpecker is the easiest of all birds to

recognize. Even if entirely new to you, you may

readily decide whether a bird is a woodpecker or

not.

The woodpecker is always striking and is

often gay in color. He is usually noisy, and his

note is clear and characteristic. His shape and

habits are peculiar, so that whenever you see a

bird clinging to the side of a tree “as if he had

been thrown at it and stuck,” you may safely

call him a woodpecker. Not that all birds which

cling to the bark of trees are woodpeckers,—for

the chickadees, the crested titmice, the nuthatches,

the brown creepers, and a few others

like the kinglets and some wrens and wood-warblers

more or less habitually climb up and down

the tree-trunks; but these do it with a pretty

grace wholly unlike the woodpecker’s awkward,

cling-fast way of holding on. As the largest of

these is smaller than the smallest woodpecker,

and as none of them (excepting only the tiny[5]

kinglets) ever shows the patch of yellow or scarlet

which always marks the head of the male

woodpecker, and which sometimes adorns his

mate, there is no danger of making mistakes.

The nuthatches are the only birds likely to

be confused with woodpeckers, and these have

the peculiar habit of traveling down a tree-trunk

with their heads pointing to the ground. A

woodpecker never does this; he may move down

the trunk of the tree he is working on, but he

will do it by hopping backward. A still surer

sign of the woodpecker is the way he sits upon

his tail, using it to brace him. No other birds

except the chimney swift and the little brown

creeper ever do this. A sure mark, also, is his

feet, which have two toes turned forward and

two turned backward. We find this arrangement

in no other North American birds except

the cuckoos and our one native parroquet. However,

there is one small group of woodpeckers

which have but three toes, and these are the only

North American land-birds that do not have four

well-developed toes.

In coloration the woodpeckers show a strong

family likeness. Except in some young birds,

the color is always brilliant and often is gaudy.

Usually it shows much clear black and white,

with dashes of scarlet or yellow about the head.[6]

Sometimes the colors are “solid,” as in the red-headed

woodpecker; sometimes they lie in close

bars, as in the red-bellied species; sometimes in

spots and stripes, as in the downy and hairy;

but there is always a contrast, never any blending

of hues. The red or yellow is laid on in

well-defined patches—square, oblong, or crescentic—upon

the crown, the nape, the jaws, or

the throat; or else in stripes or streaks down

the sides of the head and neck, as in the logcock,

or pileated woodpecker.

There is no rule about the color markings of

the sexes, as in some families of birds. Usually

the female lacks all the bright markings of the

male; sometimes, as in the logcock, she has them

but in more restricted areas; sometimes, as in

the flickers, she has all but one of the male’s

color patches; and in a few species, as the red-headed

and Lewis’s woodpeckers, the two sexes

are precisely alike in color. In the black-breasted

woodpecker, sometimes called Williamson’s

sapsucker, the male and female are so

totally different that they were long described

and named as different birds. It sometimes

happens that a young female will show the color

marks of the male, but will retain them only the

first year.

Though the woodpeckers cling to the trunks[7]

of trees, they are not exclusively climbing birds.

Some kinds, like the flickers, are quite as frequently

found on the ground, wading in the

grass like meadowlarks. Often we may frighten

them from the tangled vines of the frost grape

and the branches of wild cherry trees, or from

clumps of poison-ivy, whither they come to eat

the fruit. The red-headed woodpecker is fond

of sitting on fence posts and telegraph poles;

and both he and the flicker frequently alight on

the roofs of barns and houses and go pecking

and pattering over the shingles. The sapsuckers

and several other kinds will perch on dead limbs,

like a flycatcher, on the watch for insects; the

flickers, and more rarely other kinds, will sit

crosswise of a limb instead of crouching lengthwise

of it, as is the custom with woodpeckers.

All these points you will soon learn. You

will become familiar with the form, the flight,

and the calls of the different woodpeckers; you

will learn not only to know them by name, but

to understand their characters; they will become

your acquaintances, and later on your friends.

This heavy bird, with straight, chisel bill and

sharp-pointed tail-feathers; with his short legs

and wide, flapping wings, his unmusical but not

disagreeable voice, and his heavy, undulating,

business-like flight, is distinctly bourgeois, the[8]

type of a bird devoted to business and enjoying

it. No other bird has so much work to do all

the year round, and none performs his task with

more energy and sense. The woodpecker makes

no aristocratic pretensions, puts on none of the

coy graces and affectations of the professional

singer; even his gay clothes fit him less jauntily

than they would another bird. He is artisan to

the backbone,—a plain, hard-working, useful

citizen, spending his life in hammering holes in

anything that appears to need a hole in it. Yet

he is neither morose nor unsocial. There is a

vein of humor in him, a large reserve of mirth

and jollity. We see little of it except in the

spring, and then for a time all the laughter in

him bubbles up; he becomes uproarious in his

glee, and the melody which he cannot vent in

song he works out in the channels of his trade,

filling the woodland with loud and harmonious

rappings. Above all other birds he is the friend

of man, and deserves to have the freedom of the

fields.[9]

II

HOW THE WOODPECKER CATCHES A GRUB

Did you ever see a hairy woodpecker strolling

about a tree for what he could pick up?

There is a whur-r-rp of gay black and white

wings and the flash of a scarlet topknot as, with

a sharp cry, he dashes past you, strikes the

limb solidly with both feet, and instantly sidles

behind it, from which safe retreat he keeps a

sharp black eye fixed upon your motions. If

you make friends with him by keeping quiet, he

will presently forgive you for being there and

hop to your side of the limb, pursuing his ordinary

work in the usual way, turning his head

from side to side, inspecting every crevice, and

picking up whatever looks appetizing. Any

knot or little seam in the bark is twice scanned;

in such places moths and beetles lay their eggs.

Little cocoons are always dainty morsels, and

large cocoons contain a feast. The butterfly-hunter

who is hoping to hatch out some fine

cecropia moths knows well that a large proportion

of all the cocoons he discovers will be empty.[10]

The hairy woodpecker has been there before him,

and has torn the chrysalis out of its silken cradle.

For this the farmer should thank him

heartily, even if the butterfly-hunter does not,

for the cecropia caterpillar is destructive.

But sometimes, on the fair bark of a smooth

limb, the woodpecker stops, listens, taps, and begins

to drill. He works with haste and energy,

laying open a deep hole. For what? An apple-tree

borer was there cutting out the life of

the tree. The farmer

could see no sign of

him; neither could

the woodpecker, but

he could hear the strong grub down in his little

chamber gnawing to make it longer, or, frightened

by the heavy footsteps on his roof, scrambling

out of the way.

Boring larva.

It is easy to hear the borer at work in the

tree. When a pine forest has been burned and

the trees are dead but still standing, there will

be such a crunching and grinding of borers eating

the dead wood that it can be heard on all

sides many yards away. Even a single borer

can sometimes be heard distinctly by putting the

ear to the tree. Sound travels much farther

through solids than it does through air; notice

how much farther you can hear a railroad train[11]

by the click of the rails than by the noise that

comes on the air. Even our dull ears can detect

the woodworm, but we cannot locate him.

How, then, is the woodpecker to do what we

cannot do?

Doubtless experience teaches him much, but

one observer suggests that the woodpecker places

the grub by the sense of touch. He says he

has seen the red-headed woodpecker drop his

wings till they trailed along the branch, as if

to determine where the vibrations in the wood

were strongest, and thus to decide where the

grub was boring. But no one else appears to

have noticed that woodpeckers are in the habit

of trailing their wings as they drill for grubs.

It would be a capital study for one to attempt

to discover whether the woodpecker locates his

grub by feeling, or whether he does it by hearing

alone. Only one should be sure he is looking

for grubs and not for beetles’ eggs, nor for

ants, nor for caterpillars. By the energy with

which he drills, and the size of the hole left

after he has found his tidbit, one can decide

whether he was working for a borer.

But when the borer has been located, he has

yet to be captured. There are many kinds of

borers. Some channel a groove just beneath the

bark and are easily taken; but others tunnel[12]

deep into the wood. I measured such a hole

the other day, and found it was more than eight

inches long and larger than a lead-pencil, bored

through solid rock-maple wood. The woodpecker

must sink a hole at right angles to this

channel and draw the big grub out through his

small, rough-sided hole. You would be surprised,

if you tried to do the same with a pair

of nippers the size of the woodpecker’s bill, to

find how strong the borer is, how he can buckle

and twist, how he braces himself against the

walls of his house. Were your strength no

greater than the woodpecker’s, the task would

be much harder. Indeed, a large grub would

stand a good chance of getting away but for

one thing, the woodpecker spears him, and

thereby saves many a dinner for himself.

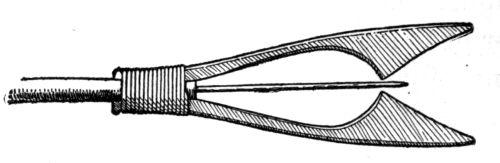

Indian spear.

Here is a primitive Indian fish-spear, such as

the Penobscots used. To the end of a long

pole two wooden jaws are tied loosely enough to

spring apart a little under pressure, and midway

between them, firmly driven into the end of the[13]

pole, is a point of iron. When a fish

was struck, the jaws sprung apart under

the force of the blow, guiding the iron

through the body of the fish, which was

held securely in the hollow above, that

just fitted around his sides, and by the

point itself.

Solomon Islander's spear.

The tool with which the woodpecker

fishes for a grub is very much the same.

His mandibles correspond to the two movable

jaws. They are knife-edged, and the

lower fits exactly inside the upper, so that

they give a very firm grip. In addition,

the upper one is movable. All birds can

move the upper mandible, because it is

hinged to the skull. (Watch a parrot

some day, if you do not believe it.) A

medium-sized woodpecker, like the Lewis’s,

can elevate his upper mandible at least a

quarter of an inch without opening his

mouth at all. This enables him to draw

his prey through a smaller hole than

would be needed if he must open his

jaws along their whole length. Between

the mandibles is the sharp-pointed

tongue, which can be thrust entirely through a

grub, holding him impaled. Unlike the Indian’s

spear-point, the woodpecker’s tongue is[14]

barbed heavily on both sides, and it is extensile.

As a tool it resembles the Solomon Islander’s

spear. A medium-sized woodpecker can dart his

tongue out two inches or more beyond the tip of

his bill. A New Bedford boy might tell us, and

very correctly, that the woodpecker harpoons

his grub, just as a whaleman harpoons a whale.

If the grub tries to back off into his burrow,

out darts the long, barbed tongue and spears

him. Then it drags him along the crooked

tunnel and into the narrow shaft picked by the

woodpecker, where the strong jaws seize and

hold him firmly.[15]

III

HOW THE WOODPECKER COURTS HIS MATE

Other birds woo their mates with songs, but

the woodpecker has no voice for singing. He cannot

pour out his soul in melody and tell his love

his devotion in music. How do songless birds

express their emotions? Some by grotesque actions

and oglings, as the horned owl, and some

by frantic dances, as the sharp-tailed grouse,

woo and win their mates; but the amorous

woodpecker, not excepting the flickers, which

also woo by gestures, whacks a piece of seasoned

timber, and rattles off interminable messages

according to the signal code set down for

woodpeckers’ love affairs. He is the only instrumental

performer among the birds; for the

ruffed grouse, though he drums, has no drum.

There is no cheerier spring sound, in our belated

Northern season, than the quick, melodious

rappings of the sapsucker from some dead ash

limb high above the meadow. It is the best

performance of its kind: he knows the capabilities

of his instrument, and gets out of it all the[16]

music there is in it. Most if not all woodpeckers

drum occasionally, but drumming is the special

accomplishment of the sapsucker. He is

easily first. In Maine, where they are abundant,

they make the woods in springtime resound

with their continual rapping. Early in

April, before the trees are green with leaf, or

the pussy-willows have lost their silky plumpness,

when the early round-leafed yellow violet

is cuddling among the brown, dead leaves, I

hear the yellow-bellied sapsucker along the

borders of the trout stream that winds down

between the mountains. The dead branch of

an elm-tree is his favorite perch, and there, elevated

high above all the lower growth, he sits

rolling forth a flood of sound like the tremolo

of a great organ. Now he plays staccato,—detached,

clear notes; and now, accelerating his

time, he dashes through a few bars of impetuous

hammerings. The woods reëcho with it;

the mountains give it faintly back. Beneath

him the ruffed grouse paces back and forth on

his favorite mossy log before he raises the palpitating

whirr of his drumming. A chickadee

digging in a rotten limb pauses to spit out

a mouthful of punky wood and the brown

Vanessa, edged with yellow, first butterfly of

the season, flutters by on rustling wings. So[17]

spring arrives in Maine, ushered in by the reveille

of the sapsucker.

So ambitious is the sapsucker of the excellence

of his performance that no instrument but

the best will satisfy him. He is always experimenting,

and will change his anvil for another

as soon as he discovers one of superior resonance.

They say he tries the tin pails of the maple-sugar

makers to see if these will not give him a

clearer note; that he drums on tin roofs and

waterspouts till he loosens the solder and they

come tumbling down. But usually he finds nothing

so near his liking as a hard-wood branch,

dead and barkless, the drier, the harder, the

thinner, the finer grained, so much the better

for his uses.

Deficient as they are in voice, the woodpeckers

do not lack a musical ear. Mr. Burroughs

tells us that a downy woodpecker of his acquaintance

used to change his key by tapping on a

knot an inch or two from his usual drumming

place, thereby obtaining a higher note. Alternating

between the two places, he gave to his

music the charm of greater variety. The woodpeckers

very quickly discover the superior conductivity

of metals. In parts of the country

where woodpeckers are more abundant than

good drumming trees, a tin roof proves an[18]

almost irresistible attraction. A lightning-rod

will sometimes draw them farther than it would

an electric bolt; and a telegraph pole, with its

tinkling glasses and ringing wires, gives them

great satisfaction. If men did not put their

singing poles in such public places, their music

would be much more popular with the woodpeckers;

but even now the birds often venture

on the dangerous pastime and hammer you out a

concord of sweet sounds from the mellow wood-notes,

the clear peal of the glass, and the ringing

overtones of the wires.

The flicker often telegraphs his love by tapping

either on a forest tree or on some loose

board of a barn or outhouse; but he has other

ways of courting his lady. On fine spring mornings,

late in April, I have seen them on a horizontal

bough, the lady sitting quietly while her

lover tried to win her approval by strange antics.

Quite often there are two males displaying their

charms in open rivalry, but once I saw them

when the field was clear. If fine clothes made

a gentleman, this brave wooer would have been

first in all the land: for his golden wings and

tail showed their glittering under side as he

spread them; his scarlet headdress glowed like

fire; his rump was radiantly white, not to speak

of the jetty black of his other ornaments and[19]

the beautiful ground-colors of his body. He

danced before his lady, showing her all these

beauties, and perhaps boasting a little of his own

good looks, though she was no less beautiful.

He spread his wings and tail for her inspection;

he bowed, to show his red crescent; he

bridled, he stepped forward and back and sidewise

with deep bows to his mistress, coaxing her

with the mellowest and most enticing co-wee-tucks,

which no doubt in his language meant

“Oh, promise me,” laughing now and then his

jovial wick-a-wick-a-wick-a-wick-a, either in glee

or nervousness. It was all so very silly—and

so very nice! I wonder how it all came out.

Did she promise him? Or did she find a gayer

suitor?[20]

IV

HOW THE WOODPECKER MAKES A HOUSE

All woodpeckers make their houses in the

wood of trees, either the trunk or one of the

branches. Almost the only exceptions to this

rule are those that live in the treeless countries

of the West. In the torrid deserts of Arizona

and the Southwest, some species are obliged to

build in the thorny branches of giant cacti,

which there grow to an enormous size. In the

treeless plains to the northward, a few individuals,

for lack of anything so suitable as the

cactus, dig holes in clay banks, or even lay their

eggs upon the surface of the prairie. In a country

where chimney swallows nest in deserted

houses, and sand martins burrow in the sides of

wells, who wonders at the flicker’s thinking that

the side of a haystack, the hollow of a wheel-hub,

or the cavity under an old ploughshare,

is an ideal home? But in wooded countries

the woodpeckers habitually nest in trees. The

only exceptions I know are a few flickers’ holes

in old posts, and a few instances where flickers[21]

have pecked through the weatherboarding of a

house to nest in the space between the walls.

But because a bird nests in a hole in a tree,

it is not necessarily a woodpecker. The sparrow-hawk,

the house sparrow, the tree swallow, the

bluebird, most species of wrens, and several of

the smaller species of owls nest either in natural

cavities in trees or in deserted woodpeckers’ holes.

The chickadees, the crested titmice, and the nuthatches

dig their own holes after the same pattern

as the woodpecker’s. However, the large,

round holes were all made by woodpeckers, and

of those under two inches in diameter, our friend

Downy made his full share. It is easy to tell

who made the hole, for the different birds have

different styles of housekeeping. The chickadees

and nuthatches always build a soft little

nest of grass, leaves, and feathers, while the

woodpeckers lay their eggs on a bed of chips,

and carry nothing in from outside.

Soon after they have mated in the spring, the

woodpeckers begin to talk of housekeeping.

First, a tree must be chosen. It may be sound or

partly decayed, one of a clump or solitary; but

it is usually dead or hollow-hearted, and at least

partly surrounded by other trees. Sometimes a

limb is chosen, sometimes an upright trunk, and

the nest may be from two feet to one hundred[22]

feet from the ground, though most frequently it

will be found not less than ten nor more than

thirty feet up. However odd the location finally

occupied, it is likely that it was not the first one

selected. A woodpecker will dig half a dozen

houses rather than occupy an undesirable tenement.

It is very common to find their unfinished

holes and the wider-mouthed, shallower

pockets which they dig for winter quarters; for

those that spend their winters in the cold North

make a hole to live in nights and cold and

stormy days.

The first step in building is to strike out a

circle in the bark as large as the doorway is to

be; that is, from an inch and a half to three

or four inches in diameter according to the size

of the woodpecker. It is nearly always a perfect

circle. Try, if you please, to draw freehand a

circle of dots as accurate as that which the woodpecker

strikes out hurriedly with his bill, and see

whether it is easy to do as well as he does.

If the size and shape of the doorway suit him,

the woodpecker scales off the bark inside his

circle of holes and begins his hard work. He

seems to take off his coat and work in his shirtsleeves,

so vigorously does he labor as he clings

with his stout toes, braced in position by his

pointed tail. The chips fly out past him, or if[23]

they lie in the hole, he sweeps them out with his

bill and pelts again at the same place. The

pair take turns at the work. Who knows how

long they work before resting? Do they take

turns of equal length? Does one work more

than the other? A pair of flickers will dig

about two inches in a day, the hole being nearly

two and a half inches in diameter. A week or

more is consumed in digging the nest, which,

among the flickers, is commonly from ten to

eighteen inches deep. The hole usually runs in

horizontally for a few inches and then curves

down, ending in a chamber large enough to

make a comfortable nest for the mother and her

babies.

What a good time the little ones have in their

hole! Rain and frost cannot chill them; no

enemy but the red squirrel is likely to disturb

them. There they lie in their warm, dark chamber,

looking up at the ray of light that comes in

the doorway, until at last they hear the scratching

of their mother’s feet as she alights on the

outside of the tree and clambers up to feed them.

What a piping and calling they raise inside the

hole, and how they all scramble up the walls of

their chamber and thrust out their beaks to be

fed, till the old tree looks as if it were blossoming

with little woodpeckers’ hungry mouths![24]

V

HOW A FLICKER FEEDS HER YOUNG[1]

[1] Based upon the observations of Mr. William Brewster.

As the house of the woodpecker has no windows

and the old bird very nearly fills the doorway

when she comes home, it is hard to find out

just how she feeds her little ones. But one of

our best naturalists has had the opportunity to

observe it, and has told what he saw.

A flicker had built a nest in the trunk of a

rather small dead tree which, after the eggs were

hatched, was accidentally broken off just at

the entrance hole. This left the whole cavity

exposed to the weather; but it was too late to

desert the nest, and impossible to remove the

young birds to another nest.

When first visited, the five little birds were

blind, naked, and helpless. They were motherless,

too. Some one must have killed their pretty

mother; for she never came to feed them, and

the father was taking all the care of his little

family. When disturbed the little birds hissed

like snakes, as is the habit of the callow young[25]

of woodpeckers, chickadees, and other birds nesting

habitually in holes in trees. When they were

older and their eyes were open, they made a clatter

much like the noise of a mowing-machine,

and loud enough to be heard thirty yards away.

The father came at intervals of from twenty

to sixty minutes to feed the little ones. He

was very shy, and came so quietly that he would

be first seen when he alighted close by with a

low little laugh or a subdued but anxious call

to the young. “Here I am again!” he laughed;

or “Are you all right, children?” he called to

them. “All right!” they would answer, clattering

in concert like a two-horse mower.

As soon as they heard him scratching on the

tree-trunk, up they would all clamber to the edge

of the nest and hold out their gaping mouths to

be fed. Each one was anxious to be fed first,

because there never was enough to go round.

There was always one that, like the little pig of

the nursery tale, “got none.” When he came

to the nest, the father would look around a

moment, trying to choose the one he wanted to

feed first. Did he always pick out the poor little

one that had none the time before, I wonder?

After the old bird had made his choice, he

would bend over the little bird and drive his

long bill down the youngster’s throat as if to[26]

run it through him. Then the little bird would

catch hold as tightly as he could and hang on

while his father jerked him up and down for a

second or a second and a half with great rapidity.

What was he doing? He was pumping

food from his own stomach into the little one’s.

Many birds feed their young in this way. They

do not hold the food in their own mouths, but

swallow and perhaps partially digest it, so that it

shall be fit for the tender little stomachs.

While the woodpecker was pumping in this

manner his motions were much the same as when

he drummed, but his tail twitched as rapidly as

his head and his wings quivered. The motion

seemed to shake his whole body.

In two weeks from the time when the little

birds were blind, naked, helpless nestlings they

became fully feathered and full grown, able to

climb up to the top of the nest, from which

they looked out with curiosity and interest.

At any noise they would slip silently back. A

day or two later they left the old nest and began

their journeys.

No naturalist has been able to tell us whether

other woodpeckers than the golden-winged flicker

feed their young in this way; and little is known

of the number of kinds of birds that use this

method, but it is suspected that it is far more[27]

common than has ever been determined. If an

old bird is seen to put her bill down a young one’s

throat and keep it there even so short a time as

a second, it is probable that she is feeding the

little one by regurgitation, that is, by pumping

up food from her own stomach. Any bird seen

doing this should be carefully watched. It has

long been known that the domestic pigeon does

this, and the same has been observed a number

of times of the ruby-throated hummingbird. A

California lady has taken some remarkable photographs

of the Anna’s hummingbird in the act,

showing just how it is done.[28]

VI

FRIEND DOWNY

No better little bird comes to our orchards

than our friend the downy woodpecker. He is

the smallest and one of the most sociable of our

woodpeckers,—a little, spotted, black-and-white

fellow, precisely like his larger cousin the hairy,

except in having the outer tail-feathers barred

instead of plain. Nearly everything that can be

said of one is equally true of the other on a

smaller scale. They look alike, they act alike,

and their nests and eggs are alike in everything

but size.

Downy is the most industrious of birds. He

is seldom idle and never in mischief. As he

does not fear men, but likes to live in orchards

and in the neighborhood of fields, he is a good

friend to us. On the farm he installs himself

as Inspector of Apple-trees. It is an old and an

honorable profession among birds. The pay is

small, consisting only of what can be picked up,

but, as cultivated trees are so infested with insects

that food is always plentiful, and as they have

[29]usually a dead branch suitable to nest in, Downy

asks no more. Summer and winter he works on

our orchards. At sunrise he begins, and he

patrols the branches till sunset. He taps on the

trunks to see whether he can hear any rascally

borers inside. He inspects every tree carefully

in a thorough and systematic way, beginning low

down and following up with a peek into every

crevice and a tap upon every spot that looks suspicious.

If he sees anything which ought not to

be there, he removes it at once.

A moth had laid her eggs in a crack in the

bark, expecting to hatch out a fine brood of

caterpillars: but Downy ate them all, thus saving

a whole branch from being overrun with caterpillars

and left fruitless, leafless, and dying. A

beetle had just deposited her eggs here. Downy

saw her, and took not only the eggs but the beetle

herself. Those eggs would have hatched into

boring larvæ, which would have girdled and killed

some of the branches, or have burrowed under

the bark, causing it to fall off, or have bored

into the wood and, perhaps, have killed the tree.

Nor is the full-grown borer exempt. Downy

hears him, pecks a few strokes, and harpoons

him with unerring aim. When Downy has

made an arrest in this way, the prisoner does

not escape from the police. Here is a colony[30]

of ants, running up the tree in one line and

down in another, touching each other with their

feelers as they pass. A feast for our friend!

He takes both columns, and leaves none to tell

the tale. This is a good deed, too, since ants

are of no benefit to fruit-trees and are very fond

of the dead-ripe fruit.

And Downy is never too busy to listen for

borers. They are fine plump morsels much to

his taste, not so sour as ants, nor so hard-shelled

as beetles, nor so insipid as insects’ eggs. A

good borer is his preferred dainty. The work he

does in catching borers is of incalculable benefit,

for no other bird can take his place. The warblers,

the vireos, and some other birds in summer,

the chickadees and nuthatches all the year

round, are helping to eat up the eggs and

insects that lie near the surface, but the only

birds equipped for digging deep under the bark

and dragging forth the refractory grubs are the

woodpeckers.

So Downy works at his self-appointed task in

our orchards summer and winter, as regular as a

policeman on his beat. But he is much more

than a policeman, for he acts as judge, jury,

jailer, and jail. All the evidence he asks against

any insect is to find him loafing about the premises.

“I swallow him first and find out afterwards[31]

whether he was guilty,” says Downy with

a wink and a nod.

Most birds do not stay all the year, in the

North, at least, and most, in return for their

labors in the spring, demand some portion of

the fruit or grain of midsummer and autumn.

Not so Downy. His services are entirely gratuitous;

he works twice as long as most others.

He spends the year with us, no winter ever

too severe for him, no summer too hot; and

he never taxes the orchard, nor takes tribute

from the berry patch. Only a quarter of his

food is vegetable, the rest being made up of

injurious insects; and the vegetable portion

consists entirely of wild fruits and weed-seeds,

nothing that man eats or uses. Downy feeds

on the wild dogwood berries, a few pokeberries,

the fruit of the woodbine, and the seeds of the

poison-ivy,—whatever scanty and rather inferior

fare is to be had at Nature’s fall and winter

table. If in the cold winter weather we will take

pains to hang out a bone with some meat on it,

raw or cooked, or a piece of suet, taking care

that it is not salted,—for few wild birds except

the crossbills can eat salted food,—we may see

how he appreciates our thoughtfulness. Shall we

grudge him a bone from our own abundance, or

neglect to fasten it firmly out of reach of the cat[32]

and dog? If his cousin the hairy and his neighbor

the chickadee come and eat with him, bid

them a hearty welcome. The feast is spread for

all the birds that help men, and friend Downy

shall be their host.[33]

VII

PERSONA NON GRATA

We shall not attempt to deny that Downy

has an unprincipled relative. While it is no discredit,

it is a great misfortune to Downy, who is

often murdered merely because he looks a little,

a very little, like this disreputable cousin of his.

The real offender is the sapsucker, that musical

genius of whom we have already spoken.

The popular belief is that every woodpecker is

a sapsucker, and that every hole he digs in a

tree is an injury to the tree. We have seen that

every hole Downy digs is a benefit, and now we

wish to learn why it is that the sapsucker’s work

is any more injurious than other woodpeckers’

holes; how we are to recognize the sapsucker’s

work; and how much damage he does. We will

do what the scientists often do,—examine the

bird’s work and make it tell us the story. There

is no danger of hurting the sapsucker’s reputation.

The farmer could have no worse opinion

of him; and, though the case has been appealed

to the higher courts of science more than once,[34]

where the sapsucker’s cause has been eloquently

and ably defended, the verdict has gone against

him. Scientists now do not deny that the sapsucker

does harm. But his worst injury is less

in the damage he does to the trees than in the ill-will

and suspicion he creates against woodpeckers

which do no harm at all. If you will study the

picture and the descriptions in the Key to the

Woodpeckers, you will be able

to recognize the sapsucker and

his nearest relatives, whether in

the East or in the West. But

all sapsuckers may be known by

their pale yellowish under parts,

and by the work they leave behind.

As the yellow-bellied sapsucker

is the only one found east

of the Rocky Mountains, we shall

speak only of him and his work.

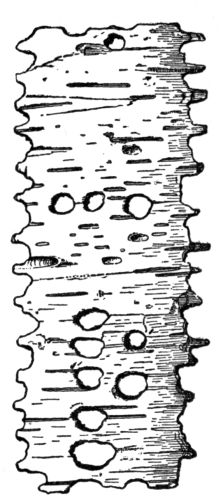

Work of Sapsucker.

Here is a specimen of the

yellow-bellied sapsucker’s work

which I picked up under the

tree from which it had fallen.

We do not need to inquire whether the tree

was injured by its falling, for we know that

the loss of sound and healthy bark is always a

damage. Was this sound bark? Yes, because

it is still firm and new. The sap in it dried

[35]quickly, showing that neither disease nor worms

caused it to fall; it is clean and hard on the

back, showing that it came from a live tree, not

from a dead, rotting log.

How do I know that a bird caused it to fall?

The marks are precisely such as are always left

by a woodpecker’s bill. How do I know that

it was a sapsucker’s work? Because no other

woodpecker has the habit which characterizes

the sapsucker, of sinking holes in straight lines.

The sapsuckers drill lines of holes sometimes

around and sometimes up and down the tree-trunk,

but almost always in rings or belts about

the trunk or branches. A girdle may be but a

single line of holes, or it may consist of four or

five, or more, lines. Sometimes a band will be

two feet wide; and as many as eight hundred

holes have been counted on the trunk of a single

tree. Such extensive peckings, however, are to

be expected only on large forest trees. Most

fruit and ornamental trees are girdled a few

times about the trunk, and about the principal

branches just below the nodes, or forks.

Why did the bird dig these holes? There are

three things that he might have obtained,—sap,

the inner bark, and boring larvæ. Some

naturalists have suggested a fourth as possible,—the

insects that would be attracted by the sap.[36]

We will see what the piece of bark tells us.

It is four and a half inches long, by an inch and

a half wide, and its area of six and three fourths

square inches has forty-four punctures. Does

this look as if the bird were digging grubs?

Do borers live in such straight little streets?

The number and arrangement of the holes show

that he was not seeking borers, while the naturalists

tell us that he never eats a borer unless

by accident. What did he get? Undoubtedly

he pecked away some of the inner bark. All

these holes are much larger on the back side of

the specimen than on the outer surface. While

the damp inner bark would shrink a little on

exposure to the air, we know that it could not

shrink as much as this; and investigation has

shown that the sapsucker feeds largely on just

such food, for it has been found in his stomach.

Two other possible food-substances remain,—sap

and insects. We know that the sapsucker

eats many insects, but it is impossible to prove

that he intended these holes for insect lures.

Sap he might have gotten from them, if he

wished it. We know that the white birch is full

of excellent sap, from which can be made a birch

candy, somewhat bitter, but nearly as good as

horehound candy. The rock and red maples

and the white canoe birch are the only trees in[37]

our Northern forests from which we make candy.

A strong probability that our bird wanted sap

is indicated by the arrangement of the holes.

Usually he drills his holes in rings around the

tree-trunk, but in this instance his longest lines

of holes are vertical. If our sapsucker was

drilling for sap, he arranged his holes so that it

would almost run into his mouth, lazy bird!

Our piece of bark has taught us:—

That the sapsucker injured this tree.

That he was not after grubs.

That he got, and undoubtedly ate, the soft

inner bark of the tree.

That he got, and may have drunk, the sap.

We could not infer any more from a single

instance, but the naturalists assure us that the

bird is in the habit of injuring trees, that he

never eats grubs intentionally, and that he eats

too much bark for it to be regarded as taken

accidentally with other food. About the sap

they cannot be so sure, as it digests very quickly.

There remain two points to prove: whether the

sapsucker drills his holes for the sake of the

sap, or for insects attracted by the sap, provided

that he eats anything but the inner bark.

Our little specimen can tell us no more, but

two mountain ash trees which were intimate

acquaintances of mine from childhood can go on[38]

with the story. Do not be surprised that I

speak of them as friends; the naturalist who

does not make friends of the creatures and

plants about will hear few stories from them.

These trees would not tell this tale to any one

but an intimate acquaintance. Let us hear what

they have to say about the sapsucker.

There are in the garden of my old home two

mountain ash trees, thirty-six years of age, each

having grown from a sprout that sprang up beside

an older tree cut down in 1863. They stand

not more than two rods apart; have the same

soil, the same amount of sun and rain, the same

exposure to wind, and equal care. During all

the years of my childhood one was a perfectly

healthy tree, full of fruit in its season, while the

other bore only scanty crops, and was always

troubled with cracked and scaling bark. To-day

the unhealthy tree is more vigorous than

ever before, while its formerly stalwart brother

stands a mere wreck of its former life and beauty.

What should be the cause of such a remarkable

change when all conditions of growth have remained

the same?

I admit that there is some internal difference

in the trees, for all the birds tell me of it. One

has always borne larger and more abundant fruit

than the other, but this is no reason why the[39]

birds should strip all the berries from that tree

before eating any from the other. When we

know that the favorite tree stands directly in

front of the windows of a much-used room and

overhangs a frequented garden path, the preference

becomes more marked. But robins, grosbeaks,

purple finches, and the whole berry-eating

tribe agree to choose one and neglect the other,

and even the spring migrants will leave the gay

red tassels of fruit still swinging on one tree, to

scratch over the leaves and eat the fallen berries

that lie beneath the other. My own taste is not

keen in choosing between bitter berries, but the

birds all agree that there is a decided difference

in these trees,—did agree, I should say, for their

favorite is the tree that is dying. Evidently

this is a question of taste. It is interesting to

observe that the sapsucker, which was never

seen to touch the fruit of the trees, agrees with

the fruit-eating birds. Nearly all his punctures

were in the tree now dying. Is there a difference

in the taste of the sap? Does the taste of

the sap affect the taste of the fruit? Or is it

merely a question of quantity? If he comes for

sap, he prefers one tree to the other on the score

either of better quality or greater quantity.

We will discuss later whether it is sap that he

wishes: all that now concerns us is to note[40]

that the internal difference, whatever it is, is in

favor of the tree that is dying; while the only

external difference appears to be the marks left

by the sapsucker. While one tree is sparingly

marked by him, the other is tattooed with his

punctures, placed in single rings and in belts

around trunk and branches beneath every fork.

It is a law of reasoning that, when every condition

but one is the same and the effects are different,

the one exceptional condition is the cause

of the difference. If these trees are alike in

everything except the work of the sapsucker (the

only internal difference apparently offsetting his

work in part), what inference do we draw as to

the effect of his work?

We presume that he is killing the tree, without

as yet knowing how he does it. What is

his object? Good observers have stated that

he draws a little sap in order to attract flies and

wasps; that the sap is not drawn for its own

sake, but as a bait for insects. Is this theory

true?

The first objection is that it is improbable.

The sapsucker is a retiring, woodland bird that

would hesitate to come into a town garden a

mile away from the nearest woods unless to get

something he could not find in the woods. Had

he wanted insects, he would have tapped a tree[41]

in the woods, or else he would have caught them

in his usual flycatching fashion. There must

have been something about the mountain ash tree

that he craved. As it is a very rare tree in the

vicinity of my home, the sapsucker’s only chance

to satisfy his longing was by coming to some

town garden like our own.

Not only is the theory improbable, but it fails

to explain the sapsucker’s actions in this instance.

In twenty years he was never seen to

catch an insect that was attracted by the sap he

drew. This does not deny that he may have

caught insects now and then, but it does deny

that he set the sap running for a lure. As he

was never far away, and was sometimes only

four and a half feet by measure from a chamber

window, all that he did could be seen. He

did not catch insects at his holes. He drank

sap and ate bark.

Finally, the theory is not only improbable and

inadequate, but in this instance it is impossible.

I do not remember seeing a sapsucker in the tree

in the spring; if he came in the summer, it must

have been at rare intervals; but he was always

there in the fall, when the leaves were dropping.

At that season the insect hordes had been dispersed

by the autumnal frosts, so that we know

he did not come for insects.[42]

In the many years during which I watched

the sapsuckers—for there were undoubtedly a

number of different birds that came, although

never more than one at a time—there was such

a curious similarity in their actions that it is

entirely proper to speak as if the same bird

returned year after year. His visits, as I have

said, were usually made at the same season. He

would come silently and early, with the evident

intention of making this an all-day excursion.

By eight o’clock he would be seen clinging to

a branch and curiously observant of the dining-room

window, which at that hour probably excited

both his interest and his alarm. Early in

the day he showed considerable activity, flitting

from limb to limb and sinking a few holes, three

or four in a row, usually above the previous

upper girdle of the limbs he selected to work

upon. After he had tapped several limbs he

would sit waiting patiently for the sap to flow,

lapping it up quickly when the drop was large

enough. At first he would be nervous, taking

alarm at noises and wheeling away on his broad

wings till his fright was over, when he would

steal quietly back to his sap-holes. When not

alarmed, his only movement was from one row

of holes to another, and he tended them with

considerable regularity. As the day wore on[43]

he became less excitable, and clung cloddishly to

his tree-trunk with ever increasing torpidity, until

finally he hung motionless as if intoxicated, tippling

in sap, a disheveled, smutty, silent bird,

stupefied with drink, with none of that brilliancy

of plumage and light-hearted gayety which made

him the noisiest and most conspicuous bird of our

April woods.

Our mountain ash trees have told us several

facts about the sapsucker:—

That he did not come to eat insects.

That he did come to drink sap, and that he

probably ate the inner bark also.

That he drank the sap because he liked it,

not for some secondary object, as insects.

That he could detect difference in the quality

or quantity of the sap, which caused him to

prefer a particular tree.

That this difference apparently was in the

taste of the sap, and that the effects of a day’s

drinking of mountain ash sap seemed to indicate

some intoxicant or narcotic quality in the

sap of that particular tree.

That the effect of his work upon the tree

was apparently injurious, as it is the only cause

assigned of a healthy tree’s dying before a less

healthy one of the same age and species, subject

all its life to the same conditions.[44]

So much we have learned about this sapsucker’s

habits, and now we should like to know why

his work is harmful, and why that of the other

woodpeckers is not. It is not because he drinks

the sap. All the sap he could eat or waste

would not harm the tree, if allowed to run out

of a few holes. Think how many gallons the

sugar-makers drain out of a single tree without

killing the tree. But the sugar-maker takes the

sap in the spring, when the crude sap is mounting

up in the tree, while the sapsucker does not

begin his work till midsummer or autumn, when

the tree is sending down its elaborated sap to

feed the trunk and make it grow. This accounts

for the woodpecker’s digging his pits

above the lines of the holes already in the tree.

The loss of this elaborated sap is a greater injury

than the waste of a far larger quantity of

crude sap, so that on the season of the year

when the sapsucker digs his holes depends in

large measure the amount of damage he does.

The injury that he does to the wood itself is

trivial. He is not a woodpecker except at time

of nesting, and most woodpeckers prefer to build

in a dead or dying branch, where their work

does no hurt. But we know very well that a

tree may be a wreck, riven from top to bottom

by lightning, split open to the heart by the tempest,[45]

entirely hollow the whole length of its

trunk, and yet may flourish and bear fruit.

The tree lives in its outer layers. It may be

crippled in almost any way, if the bark is left

uninjured; but if an inch of bark is cut out

entirely around the tree, it will die, for the sap

can no longer run up and down to nourish it.

This is the sapsucker’s crime: he girdles the

tree,—not at his first coming, nor yet at his

second, not with one row of holes, nor yet

with two; but finally, after years perhaps, when

row after row of punctures, each checking a

little the flow of sap, have overlapped and offset

each other and narrowed the channels through

which it could mount and descend, until the flow

is stopped. Then the tree dies. It is not the

holes he makes, nor the sap he draws, but the

way he places his holes that makes the sapsucker

an unwelcome visitor. For an unacceptable

individual he is to the farmer,—persona

non grata, as kings say of ambassadors who do

not please their majesties. What shall we do

with him, the only black sheep in all the woodpecker

flock? Let him alone, unless we are positively

sure that we know him from every other

kind of woodpecker. The damage he does is

trifling compared with what we should do if we

made war upon other woodpeckers for some supposed

wrong-doing of the sapsucker.[46]

VIII

EL CARPINTERO

In California and along the southwestern

boundary of the United States lives a woodpecker

known among the Mexicans as El Carpintero,

the Carpenter.

Carpentering is both his profession and his

pastime, and he seems really to enjoy the work.

When there is nothing more pressing to be done,

he spends his time tinkering around, fitting

acorns into holes in such great numbers and in

so workmanlike a fashion that we do not know

which is more remarkable, his patience or his

skill. Every acorn is fitted into a separate hole

made purposely for it, every one is placed butt

end out and is driven in flush with the surface,

so that a much frequented tree often appears as

if studded with ornamental nails. “What an

industrious bird!” we exclaim; but still it takes

some time to appreciate how enormous is the

labor of the Carpenter. Whole trees will sometimes

be covered with his work, until a single

tree has thousands of acorns bedded into its bark[47]

so neatly and tightly that no other creature can

remove them.

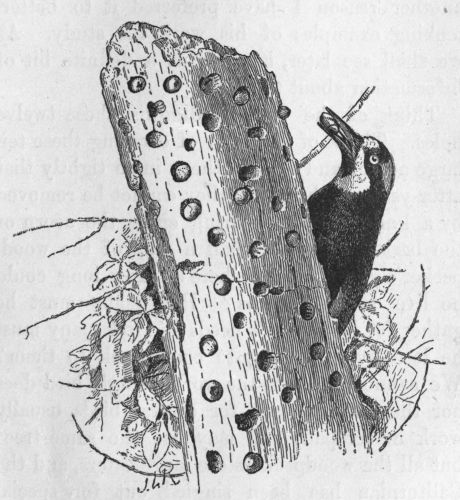

Work of Californian Woodpecker.

We may take for examination, from specimens

of the Carpenter’s work, a piece of spruce bark

seven inches long by six wide, containing ten

acorns and two empty holes. As spruce bark

is so much harder and rougher than the pine[48]

bark in which he usually stores his nuts,[1] this

specimen looks rough and unfinished, and even

shows some acorns driven in sidewise; but for

another reason I have preferred it to better-looking

examples of his work for study. As

we shall see later, it gives us a definite bit of

information about the bird.

[1] They often use white-oak bark, fence-posts, telegraph poles,

even the stalks of century-plants, when trees are not convenient.

(Merriam, Auk, viii. 117.)

Think of the work of digging these twelve

holes. Think of the labor of carrying these ten

large acorns and driving them in so tightly that

after years of shrinking they cannot be removed

by a knife without injuring either the acorn or

the bark. Yet how small a part of the woodpecker’s

year’s work is here! How long could

he live on ten acorns? How many must he

gather for his winter’s needs? How many must

he lose by forgetting to come back to them?

We cannot calculate the work a single bird does

nor the nuts he eats, for several birds usually

work in company and may use the same tree;

but all the woodpeckers are large eaters, and the

Californian has been singled out for special

mention.

Can we estimate the amount of work required

to lay up one day’s food? Judging by the[49]

amount of nuts some other birds will eat, I

should think that all ten acorns contained in this

piece of bark could be eaten in one day without

surfeit. The estimate seems to me well inside

of his probable appetite. I have experimented

on this piece of bark, using a woodpecker’s bill

for a tool, and it takes me twenty minutes to

dig a hole as large but not as neat as these.

Doubtless it would not take the woodpecker as

long; but at my rate of working, four hours

were spent in digging these twelve holes. Then

each acorn had to be hunted up and brought to

the hole prepared for it. This entailed a journey,

it may have been only from one tree to

another, or it may have been, and very likely was,

a considerable flight. For these acorns grew on

oak-trees, and we find them driven into the bark

of pines and spruces.

This it is which gives our specimen its particular

interest. While oaks and pines may be intermingled,

though they naturally prefer different

soils and situations, and in the Rocky Mountains

the pine-belt lies above the oak region, spruce

and oak trees do not grow in the same soil.

The spruce-belt stands higher up than the pine.

As these nuts are stored in the bark of a spruce-tree,

we have clear evidence that the bird must

have carried them some distance. For every[50]

nut he made the whole journey back and forth,

since he could carry but one at a time,—ten

long trips back and forth, certainly consuming

several minutes each.

Then each acorn had to be fitted to its hole.

We have already spoken of the accuracy with

which this is done, so that the Carpenter’s work

is a standing taunt to the hungry jays and

squirrels which would gladly eat his nuts if

they could get them. A careful observer tells

us that when the hole is too small, the woodpecker

takes the acorn out and makes the hole

a little larger, working so cautiously, however,

that he sometimes makes several trials before the

acorn can be fitted and driven in flush with the

bark. Some of these acorns show cracks down

the sides, as if they had been split either in

forcibly pulling them out of a hole not deep

enough for them, or in driving them when

green and soft into a hole too small for them.

Of course after each trial the acorn must be

hunted up where it lies on the ground and

driven in again, and this takes considerable

time.

As nearly as we can estimate it, not less than

half a day must have been spent in putting

these acorns where we find them. With smaller

acorns, stored in pine bark, less time would have[51]

been required; but weeks, if not months, of

work are spent in laying up the winter’s stores.

How the woodpecker’s back and jaws must

have ached! Surely he is human enough to get

tired with his work, and it is not play to do what

this bird has done. Some of the acorns measure

seven tenths of an inch in diameter by nine

tenths in length, and the bird that carried them

is smaller than a robin. How he must have

hurried to reach his tree when the acorn was

extra large! Yet he took time to drive every

one in point foremost. Even those that lie

upon their sides must have been forced into

position by tapping the butt. He knows very

well which end of an acorn is which, does our

Carpenter.

But what is the use of all this work? Why,

if he wants acorns, does he not eat them as they

lie scattered under the oaks, instead of taking

pains to carry them away and put them into

holes for the fun of eating them out of the

holes afterward? The absurdity of this has

led some people to surmise that the Carpenter

chooses none but weevilly acorns, and stores

them that the grub inside may grow large and

fat and delicious. This would be very interesting,

if it were true. There must of course be

more weevilly acorns on the ground than he[52]

picks up, so that he could get as many grubs

without taking all this trouble, and there is no

reason why they should not be as large and

good as those hatched out in holes in trees.

When I wish to keep nuts sweet, I spread them

out on the attic floor in the sun and air, keeping

them where they will not touch each other.

The Carpenter does practically the same thing.

Is it probable that he tries to raise a fine crop

of grubs in this way? If so, one or the other

of us is doing just the wrong thing. But if weevils

are what the Carpenter wants, then the nuts

in the bark should be wormy; yet only two of

them show any sign of a weevil, and of these one

appears from its dull color and weather-beaten

look to be a nut deposited several years before

the others by some other woodpecker. Every

other acorn is as hard, shining, and bright colored

as when it fell from the tree. Evidently the

bird picked these nuts up while they were fresh

and good; perhaps he chose them because they

were good and fresh. The possibility becomes

almost a certainty when we observe that naturalists

agree that the Carpenter uses no acorns

but the sweet-tasting species. Now there are

likely to be as many grubs in one kind of an

acorn as in another, and he would scarcely refuse

any kind that contained them, if grubs[53]

were what he wanted. The fact that he takes

sweet acorns, and those only, shows that it is the

meat of the nut that he wants. And all good

naturalists agree that it is the kernel itself that

he eats.

Why he stores them is not hard to decide

when we remember that the Californian woodpecker,

over a large part of his range, is a

mountain bird. Though we think of California

as the land of sunshine, it is not universal summer

there. The mountain ranges have a winter

as severe as that of New England, with a heavy

snowfall. When the snow lies several feet deep

among the pines and spruces of the uplands, the

Carpenter is not distressed for food: his pantry

is always above the level of the snow; he need

neither scratch a meagre living from the edges

of the snow-banks, nor go fasting. His fall’s

work has provided him not only with the necessities,

but with the luxuries of life.

But why does he spend so much time in making

holes? He might tuck his nuts into some

natural crevice in the oak bark, or drop them

into cavities which all birds know so well where

to find. And leave them where any pilfering

jay would be able to pick them out at his ease?

Or put them in the track of every wandering

squirrel? Jays and squirrels are never too honest[54]

to refuse to steal, but they find it harder

to get the woodpecker’s stores out of his pine-tree

pantry than to pick up honest acorns of

their own. So, like the woodpecker, they lay

up their own stores of nuts, and feed on them

in winter, or go hungry.

We have had very little aid from anything

except the piece of bark we were studying,

yet we have learned that the Californian woodpecker

is a good carpenter; that he works hard

at his trade; that he shows remarkable foresight

in collecting his food, much ingenuity in

housing it, good judgment in putting it where

his enemies cannot get it, and wisdom in the

plan he has adopted to give him a good supply

of fresh nuts at a season when the autumn’s

crop is buried under the deep snow.

If I were a Californian boy, I think I should

spend my time in trying to find out more about

this wise woodpecker, concerning which much

remains to be discovered.[55]

IX

A RED-HEADED COUSIN

Besides his half-brothers, the narrow-fronted

and ant-eating woodpeckers, the Carpenter has

a numerous family of cousins,—the red-headed,

the red-bellied, the golden-fronted, the Gila,[1]

and the Lewis’s woodpeckers. These all belong

to one genus, and are much alike in structure,

though totally different in color. Most of them

are Western or Southwestern birds, but one is

found in nearly all parts of the United States

lying between the Hudson River and the Rocky

Mountains, and is the most abundant woodpecker

of the middle West. This well-known cousin is

the red-headed woodpecker, the tricolored beauty

that sits on fence-posts and telegraph poles, and

sallies out, a blaze of white, steel-blue, and scarlet,

a gorgeous spectacle, whenever an insect

flits by. He is the one that raps so merrily on

your tin roofs when he feels musical.

[1] So named from being found along the Gila River.

In many ways the red-head, as he is familiarly

called, is like his carpenter cousin. Both[56]

indulge in long-continued drumming; both catch

flies expertly on the wing; and both have the

curious habit of laying up stores of food for

future use. The Californian woodpecker not

only stores acorns, but insect food as well. But

though the Carpenter’s habits have long been

known, it is a comparatively short time since

the red-head was first detected laying up winter

supplies.

The first to report this habit of the red-head

was a gentleman in South Dakota, who one

spring noticed that they were eating young

grasshoppers. At that season he supposed that

all the insects of the year previous would be

dead or torpid, and certainly full-grown, while

those of the coming summer would be still in

the egg. Where could the bird find half-grown

grasshoppers? Being interested to explain this,

he watched the red-heads until he saw that one

went frequently to a post, and appeared to get

something out of a crevice in its side. In that

post he found nearly a hundred grasshoppers,

still alive, but wedged in so tightly they could

not escape. He also found other hiding-places

all full of grasshoppers, and discovered that the

woodpeckers lived upon these stores nearly all

winter.

But it is not grasshoppers only that the red-head

[57]hoards, though he is very fond of them.

In some parts of the country it is easier to find

nuts than to find grasshoppers, and they are

much less perishable food. The red-head is

very fond of both acorns and beechnuts. Probably

he eats chestnuts also. Who knows how

many kinds of nuts the red-head eats? You

might easily determine not only what he will

eat, but what he prefers, if a red-headed woodpecker

lives near you. Lay out different kinds

of nuts on different days, putting them on a

shed roof, or in some place where squirrels and

blue jays would not be likely to dare to steal

them, and see whether he takes all the kinds

you offer. Then lay out mixed nuts and notice

which ones he carries off first. If he takes all

of one kind before he takes any of the others, we

may be sure that he has discovered his favorite

nut. Such little experiments furnish just the

information which scientific men are glad to get.

It is well known that the red-head is very

fond of beechnuts. Every other year we expect

a full crop of nuts, and close observation shows

that the red-heads come to the North in much

larger numbers and stay much later on these

years of plenty than on the years of scanty

crops. Lately it has been discovered that they

not only eat beechnuts all the fall, but store[58]

them up for winter use. This time the observation

was made in Indiana. There, when the nuts

were abundant, the red-heads were seen busily

carrying them off. Their accumulations were

found in all sorts of places: cavities in old tree-trunks

contained nuts by the handful; knot-holes,

cracks, crevices, seams in the barns were

filled full of nuts. Nuts were tucked into the

cracks in fence-posts; they were driven into

railroad ties; they were pounded in between

the shingles on the roofs; if a board was sprung

out, the space behind it was filled with nuts,

and bark or wood was often brought to cover

over the gathered store. No doubt children

often found these hiding-places and ate the nuts,

thinking they were robbing some squirrel’s

hoard.

In the South, where the beech-tree is replaced

by the oak, the red-heads eat acorns. I

should like to know whether they store acorns

as they do beechnuts. Are chestnuts ever laid

up for winter? How far south is the habit kept

up? Is it observed beyond the limits of a regular

and considerable snowfall? That is, do the

birds lay up their nuts in order to keep them

out of the snow, or for some other reason?

It remains to be discovered if other woodpeckers

have hoarding-places. We know that[59]

the sapsucker eats beechnuts, and the downy

and the hairy woodpeckers also; that the red-bellied

woodpecker and the golden-winged flicker

eat acorns; and I have seen the downy woodpecker

eating chestnuts, or the grubs in them,

hanging head downward at the very tip of the

branches like a chickadee. It may be possible

that some of these lay up winter stores.

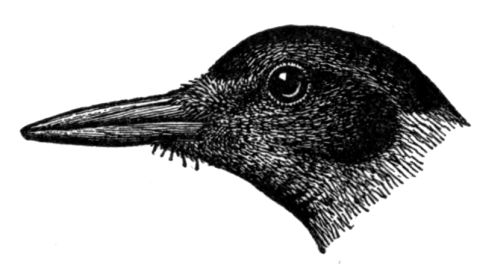

Head of the Lewis's Woodpecker.

It is known that the Lewis’s woodpecker occasionally

shows signs of a hoarding instinct. It

was recently noted that in the San Bernardino

Mountains of California the Lewis’s woodpecker,

after driving away the smaller Californian woodpeckers,

tried to put acorns into the holes the

Carpenter had made, but, being unused to the

work, did it very clumsily.

Soon after this observation

was published,

a boy friend living near

Denver told me that a

short time before he had

seen a woodpecker that had a large quantity

of acorns shelled and broken into quarters, on

which he was feeding. This woodpecker was

identified beyond a doubt as the Lewis’s woodpecker.

So we begin to suspect that the habit