The Project Gutenberg eBook of Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 1, No. 6

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 1, No. 6

Author: Various

Release date: December 13, 2009 [eBook #30666]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Anne Storer, and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRDS, ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY, VOL. 1, NO. 6 ***

Transcriber’s Notes:

1) Cover added.

2) A couple of unusual spellings in the “ads”

have been left as printed.

BIRDS

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY

A MONTHLY SERIAL

DESIGNED TO PROMOTE

KNOWLEDGE OF BIRD-LIFE

“With cheerful hop from perch to spray,

They sport along the meads;

In social bliss together stray,

Where love or fancy leads.

Through spring’s gay scenes each happy pair

Their fluttering joys pursue;

Its various charms and produce share,

Forever kind and true.”

CHICAGO, U. S. A.

Nature Study Publishing Company, Publishers

1896

PREFACE.

T has become a universal custom to obtain and preserve the likenesses

of one’s friends. Photographs are the most popular form of these likenesses,

as they give the true exterior outlines and appearance, (except

coloring) of the subjects. But how much more popular and useful does

photography become, when it can be used as a means of securing plates from

which to print photographs in a regular printing press, and, what is more

astonishing and delightful, to produce the real colors of nature as shown in

the subject, no matter how brilliant or varied.

We quote from the December number of the Ladies’ Home Journal:

“An excellent suggestion was recently made by the Department of Agriculture

at Washington that the public schools of the country shall have a new holiday,

to be known as Bird Day. Three cities have already adopted the suggestion,

and it is likely that others will quickly follow. Of course, Bird Day will differ

from its successful predecessor, Arbor Day. We can plant trees but not birds.

It is suggested that Bird Day take the form of bird exhibitions, of bird exercises,

of bird studies—any form of entertainment, in fact, which will bring

children closer to their little brethren of the air, and in more intelligent

sympathy with their life and ways. There is a wonderful story in bird life, and

but few of our children know it. Few of our elders do, for that matter. A

whole day of a year can well and profitably be given over to the birds. Than

such study, nothing can be more interesting. The cultivation of an intimate

acquaintanceship with our feathered friends is a source of genuine pleasure.

We are under greater obligations to the birds than we dream of. Without them

the world would be more barren than we imagine. Consequently, we have

some duties which we owe them. What these duties are only a few of us

know or have ever taken the trouble to find out. Our children should not be

allowed to grow to maturity without this knowledge. The more they know of

the birds the better men and women they will be. We can hardly encourage

such studies too much.”

Of all animated nature, birds are the most beautiful in coloring, most

graceful in form and action, swiftest in motion and most perfect emblems of

freedom.

They are withal, very intelligent and have many remarkable traits,

so that their habits and characteristics make a delightful study for all lovers of

nature. In view of the facts, we feel that we are doing a useful work for the

young, and one that will be appreciated by progressive parents, in placing

within the easy possession of children in the homes these beautiful photographs

of birds.

The text is prepared with the view of giving the children as clear an idea

as possible, of haunts, habits, characteristics and such other information as will

lead them to love the birds and delight in their study and acquaintance.

NATURE STUDY PUBLISHING

[Pg 187]

BIRDS.

Illustrated by COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY.

BIRD SONG.

“I cannot love the man who doth not love,

As men love light, the song of happy birds.”

T is indeed fitting that the

great poets have ever been the

best interpreters of the songs of

birds. In many of the plays of

Shakespeare, especially where the

scene is laid in the primeval forest, his

most delicious bits of fancy are

inspired by the flitting throng.

Wordsworth and Tennyson, and many

of the minor English poets, are pervaded

with bird notes, and Shelley’s masterpiece,

The Skylark, will long survive

his greater and more ambitious poems.

Our own poet, Cranch, has left one

immortal stanza, and Bryant, and

Longfellow, and Lowell, and Whittier,

and Emerson have written enough

of poetic melody, the direct inspiration

of the feathered inhabitants of the

woods, to fill a good-sized volume. In

prose, no one has said finer things than

Thoreau, who probed nature with a

deeper ken than any of his contemporaries.

He is to be read, and read,

and read.

But just what meaning should be

attached to a bird’s notes—some of

which are “the least disagreeable of

noises”—will probably never be discovered.

They do seem to express

almost every feeling of which the

human heart is capable. We wonder

if the Mocking Bird understands what

all these notes mean. He is so fine an

imitator that it is hard to believe he is

not doing more than mimicking the

notes of other birds, but rather that

he really does mock them with a sort

of defiant sarcasm. He banters them

less, perhaps, than the Cat Bird, but

one would naturally expect all other

birds to fly at him with vengeful

purpose. But perhaps the birds are

not so sensitive as their human

brothers, who do not always look upon

imitation as the highest flattery.

A gentleman who kept a note-book,

describes one of the matinee performances

of the Mocker, which he attended

by creeping under a tent curtain. He

sat at the foot of a tree on the top of

which the bird was perched unconscious

of his presence. The Mocker

gave one of the notes of the Guinea-hen,

a fine imitation of the Cardinal,

or Red Bird, an exact reproduction of

the note of the Phoebe, and some of the

difficult notes of the Yellow-breasted

Chat. “Now I hear a young chicken

peeping. Now the Carolina Wren sings,

‘cheerily, cheerily, cheerily.’ Now a

small bird is shrilling with a fine insect

tone. A Flicker, a Wood-pewee, and a

Phoebe follow in quick succession.

Then a Tufted Titmouse squeals.

To display his versatility, he gives a

dull performance which couples the

‘go-back’ of the Guinea fowl with the

[Pg 188]

plaint of the Wood-pewee, two widely

diverse vocal sounds. With all the

performance there is such perfect self-reliance

and consciousness of superior

ability that one feels that the singer

has but to choose what bird he will

imitate next.”

Nor does the plaintive, melancholy

note of the Robin, that “pious” bird,

altogether express his character. He

has so many lovely traits, according to

his biographers, that we accept him

unhesitatingly as a truly good bird.

Didn’t he once upon a time tenderly

cover with leaves certain poor little

wanderers? Isn’t he called “The Bird

of the Morning?” And evening as

well, for you can hear his sad voice

long after the sun has himself retired.

The poet Coleridge claims the credit

of first using the Owl’s cry in poetry,

and his musical note Tu-whit, tu-who!

has made him a favorite with the

poets. Tennyson has fancifully

played upon it in his little “Songs to

the Owl,” the last stanza of which

runs:

“I would mock thy chant anew;

But I cannot mimic it,

Not a whit of thy tuhoo,

Thee to woo to thy tuwhit,

Thee to woo to thy tuwhit.

With a lengthen’d loud halloo,

Tuwhoo, tuwhit, tuwhit, tuhoo-o-o.”

But Coleridge was not correct in his

claim to precedence in the use of the

Owl’s cry, for Shakespeare preceded

him, and Tennyson’s “First Song to

the Owl” is modeled after that at the

end of “Love’s Labor Lost:”

“When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl,

Then nightly sings the staring Owl,

Tu-who;

Tu-whit, tu-who, a merry note.”

In references to birds, Tennyson is

the most felicitous of all poets and the

exquisite swallow-song in “The

Princess” is especially recommended

to the reader’s perusal.

Birds undoubtedly sing for the same

reasons that inspire to utterance all

the animated creatures in the universe.

Insects sing and bees, crickets, locusts,

and mosquitos. Frogs sing, and mice,

monkeys, and woodchucks. We have

recently heard even an English

Sparrow do something better than

chipper; some very pretty notes

escaped him, perchance, because his

heart was overflowing with love-thoughts,

and he was very merry, knowing

that his affection was reciprocated.

The elevated railway stations, about

whose eaves the ugly, hastily built

nests protrude everywhere, furnish

ample explanation of his reasons for

singing.

Birds are more musical at certain

times of the day as well as at certain

seasons of the year. During the hour

between dawn and sunrise occurs the

grand concert of the feathered folk.

There are no concerts during the

day—only individual songs. After

sunset there seems to be an effort to

renew the chorus, but it cannot be

compared to the morning concert

when they are practically undisturbed

by man.

Birds sing because they are happy.

Bradford Torrey has given with much

felicity his opinion on the subject, as

follows:

“I recall a Cardinal Grosbeak, whom

I heard several years ago, on the bank

of the Potomac river. An old soldier

had taken me to visit the Great Falls,

and as we were clambering over the

rocks this Grosbeak began to sing;

and soon, without any hint from me,

and without knowing who the invisible

musician was, my companion remarked

upon the uncommon beauty of the

song. The Cardinal is always a great

singer, having a voice which, as

European writers say, is almost equal

to the Nightingale’s; but in this case

the more stirring, martial quality of

the strain had given place to an

exquisite mellowness, as if it were,

what I have no doubt it was,

A Song of Love.”

—C. C. Marble.

[to be continued.]

[Pg 189]

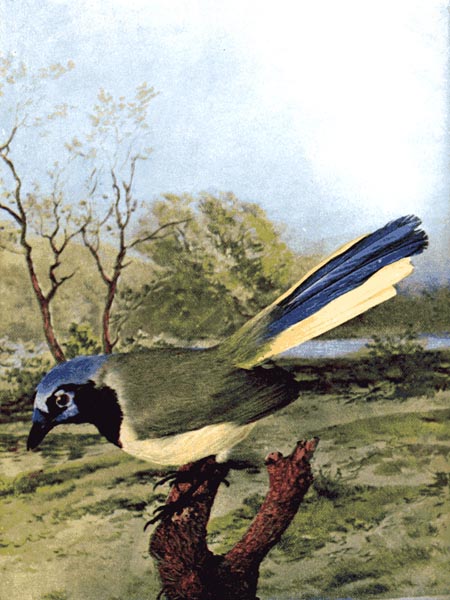

yellow-throated vireo.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

[Pg 191]

THE YELLOW-THROATED VIREO.

HE popular name of this species

of an attractive family is

Yellow Throated Greenlet,

and our young readers will

find much pleasure in watching its

pretty movements and listening to its

really delightful song whenever they

visit the places where it loves to spend

the happy hours of summer. In some

respects it is the most remarkable of

all the species of the family found in

the United States. “The Birds of

Illinois,” a book that may be profitably

studied by the young naturalist, states

that it is decidedly the finest singer,

has the loudest notes of admonition

and reproof, and is the handsomest in

plumage, and hence the more attractive

to the student.

A recognized observer says he has

found it only in the woods, and mostly

in the luxuriant forests of the bottom

lands. The writer’s experience accords

with that of Audubon and Wilson,

the best authorities in their day, but

the habits of birds vary greatly with

locality, and in other parts of the

country, notably in New England, it

is very familiar, delighting in the

companionship of man. It breeds in

eastern North America, and winters in

Florida, Cuba and Central America.

The Vireo makes a very deep nest,

suspended by its upper edge, between

the forks of a horizontal branch. The

eggs are white, generally with a few

reddish brown blotches. All authorities

agree as to the great beauty of the

nest, though they differ as to its exact

location. It is a woodland bird, loving

tall trees and running water,

“haunting the same places as the

Solitary Vireo.” During migration

the Yellow-throat is seen in orchards

and in the trees along side-walks and

lawns, mingling his golden colors with

the rich green of June leaves.

The Vireos, or Greenlets, are like

the Warblers in appearance and habits.

We have no birds, says Torrey, that

are more unsparing of their music;

they sing from morning till night,

and—some of them, at least—continue

theirs till the very end of the

season. The song of the Yellow-throat

is rather too monotonous and

persistent. It is hard sometimes not

to get out of patience with its ceasless

and noisy iteration of its simple tune;

especially if you are doing your utmost

to catch the notes of some rarer and

more refined songster. This is true

also of some other birds, whose occasional

silence would add much to their

attractiveness.

[Pg 192]

THE MOCKING BIRD.

Some bright morning this

month, you may hear a Robin’s

song from a large tree near by.

A Red Bird answers him and

then the Oriole chimes in. I can

see you looking around to find

the birds that sing so sweetly.

All this time a gay bird sits

among the green leaves and

laughs at you as you try to find

three birds when only one is

there.

It is the Mocking Bird or

Mocker, and it is he who has

been fooling you with his song.

Nature has given him lots of

music and gifted him with the

power of imitating the songs of

other birds and sounds of other

animals.

He is certainly the sweetest of

our song birds. The English

Nightingale alone is his rival.

I think, however, if our Mocker

could hear the Nightingale’s

song, he could learn it.

The Mocking Bird is another

of our Thrushes. By this time

you have surely made up your

minds that the Thrushes are

sweet singers.

The Mocker seems to take

delight in fooling people. One

gentleman while sitting on his

porch heard what he thought to

be a young bird in distress. He

went in the direction of the

sound and soon heard the same

cry behind him. He turned and

went back toward the porch,

when he heard it in another

direction. Soon he found out

that Mr. Mocking Bird had been

fooling him, and was flying

about from shrub to shrub

making that sound.

His nest is carelessly made

of almost anything he can find.

The small, bluish-green eggs

are much like the Catbird’s eggs.

Little Mocking Birds look

very much like the young of

other Thrushes, and do not

become Mockers like their parents,

until they are full grown.

Which one of the other

Thrushes that you have seen in

Birds does the Mocking Bird

resemble?

He is the only Thrush that

sings while on the wing. All

of the others sing only while

perching.

[Pg 193]

american mocking bird.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

[Pg 194]

JUNE.

Frank-hearted hostess of the field and wood,

Gipsy, whose roof is every spreading tree,

June is the pearl of our New England year,

Still a surprisal, though expected long,

Her coming startles. Long she lies in wait,

Makes many a feint, peeps forth, draws coyly back,

Then, from some southern ambush in the sky,

With one great gush of blossoms storms the world.

A week ago the Sparrow was divine;

The Bluebird, shifting his light load of song

From post to post along the cheerless fence,

Was as a rhymer ere the poet came;

But now, O rapture! sunshine winged and voiced,

Pipe blown through by the warm, wild breath of the West,

Shepherding his soft droves of fleecy cloud,

Gladness of woods, skies, waters, all in one,

The Bobolink has come, and, like the soul

Of the sweet season vocal in a bird,

Gurgles in ecstasy we know not what

Save June! Dear June! Now God be praised for June.

—Lowell.

[Pg 196]

black-crowned night heron.

From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

[Pg 197]

THE BLACK-CROWNED NIGHT HERON.

HAT a beautiful creature

this is! A mounted specimen

requires, like the

Snowy Owl, the greatest

care and a dust tight glass case to preserve

its beauty. Dr. Coues’ account

of it should be read by those who are

interested in the science of ornithology.

It is a common bird in the United

States and British Provinces, being

migratory and resident in the south.

Heronries, sometimes of vast extent, to

which they return year after year, are

their breeding places. Each nest contains

three or four eggs of a pale, sea-green

color. Observe the peculiar

plumes, sometimes two, in this case

three, which spring from the back of

the head. These usually lie close

together in one bundle, but are often

blown apart by the wind in the form

of streamers. This Heron derives its

name from its habits, as it is usually

seen flying at night, or in the early

evening, when it utters a sonorous cry

of quaw or quawk. It is often called

Quawk or Qua-Bird.

On the return of the Black-Crowned

Night Heron in April, he promptly

takes possession of his former home,

which is likely to be the most solitary

and deeply shaded part of a cedar

swamp. Groves of swamp oak in

retired and water covered places, are

also sometimes chosen, and the males

often select tall trees on the bank of

the river to roost upon during the day.

About the beginning of twilight they

direct their flight toward the marshes,

uttering in a hoarse and hollow tone,

the sound qua. At this hour all the

nurseries in the swamps are emptied

of their occupants, who disperse about

the marshes along the ditches and

river shore in search of food. Some

of these nesting places have been

occupied every spring and summer for

many years by nearly a hundred pair

of Herons. In places where the cedars

have been cut down and removed the

Herons merely move to another part

of the swamp, not seeming greatly disturbed

thereby; but when attacked and

plundered they have been known to

remove from an ancient home in a

body to some unknown place.

The Heron’s nest is plain enough,

being built of sticks. On entering

the swamp in the neighborhood of one

of the heronries the noise of the old

and young birds equals that made by

a band of Indians in conflict. The

instant an intruder is discovered, the

entire flock silently rises in the air

and removes to the tops of the trees in

another part of the woods, while sentries

of eight or ten birds make occasional

circuits of inspection.

The young Herons climb to the tops

of the highest trees, but do not attempt

to fly. While it is probable these

birds do not see well by day, they

possess an exquisite facility of hearing,

which renders it almost impossible

to approach their nesting places

without discovery. Hawks hover over

the nests, making an occasional sweep

among the young, and the Bald Eagle

has been seen to cast a hungry eye

upon them.

The male and female can hardly be

distinguished. Both have the plumes,

but there is a slight difference in size.

The food of the Night Heron, or

Qua-Bird, is chiefly fish, and his two

interesting traits are tireless watchfulness

and great appetite. He digests

his food with such rapidity that however

much he may eat, he is always

ready to eat again; hence he is little

benefited by what he does eat, and is

ever in appearance in the same half-starved

state, whether food is abundant

or scarce.

[Pg 198]

THE RING-BILLED GULL.

HE Ring-billed Gull is a common

species throughout eastern

North America, breeding

throughout the northern tier

of the United States, whose northern

border is the limit of its summer

home. As a rule in winter it is found

in Illinois and south to the Gulf of

Mexico. It is an exceedingly voracious

bird, continually skimming over

the surface of the water in search of

its finny prey, and often following

shoals of fish to great distances. The

birds congregate in large numbers at

their breeding places, which are rocky

islands or headlands in the ocean.

Most of the families of Gulls are somewhat

migratory, visiting northern

regions in summer to rear their young.

The following lines give with remarkable

fidelity the wing habits and

movements of this tireless bird:

“On nimble wing the gull

Sweeps booming by, intent to cull

Voracious, from the billows’ breast,

Marked far away, his destined feast.

Behold him now, deep plunging, dip

His sunny pinion’s sable tip

In the green wave; now highly skim

With wheeling flight the water’s brim;

Wave in blue sky his silver sail

Aloft, and frolic with the gale,

Or sink again his breast to lave,

And float upon the foaming wave.

Oft o’er his form your eyes may roam,

Nor know him from the feathery foam,

Nor ’mid the rolling waves, your ear

On yelling blast his clamor hear.”

This Gull lives principally on fish,

but also greedily devours insects. He

also picks up small animals or animal

substances with which he meets, and,

like the vulture, devours them even in a

putrid condition. He walks well and

quickly, swims bouyantly, lying in the

water like an air bubble, and dives with

facility, but to no great depth.

As the breeding time approaches

the Gulls begin to assemble in flocks,

uniting to form a numerous host.

Even upon our own shores their nesting

places are often occupied by many

hundred pairs, whilst further north

they congregate in countless multitudes.

They literally cover the rocks

on which their nests are placed, the

brooding parents pressing against each

other.

Wilson says that the Gull, when

riding bouyantly upon the waves and

weaving a sportive dance, is employed

by the poets as an emblem of purity,

or as an accessory to the horrors of a

storm, by his shrieks and wild piercing

cries. In his habits he is the vulture

of the ocean, while in grace of motion

and beauty of plumage he is one of

the most attractive of the splendid

denizens of the ocean and lakes.

The Ring-billed Gull’s nest varies

with localities. Where there is grass

and sea weed, these are carefully

heaped together, but where these fail

the nest is of scanty material. Two

to four large oval eggs of brownish

green or greenish brown, spotted with

grey and brown, are hatched in three

or four weeks, the young appearing in

a thick covering of speckled down.

If born on the ledge of a high rock,

the chicks remain there until their

wings enable them to leave it, but if

they come from the shell on the sand

of the beach they trot about like little

chickens. During the first few days

they are fed with half-digested food

from the parents’ crops, and then with

freshly caught fish.

The Gull rarely flies alone, though

occasionally one is seen far away from

the water soaring in majestic solitude

above the tall buildings of the city.

[Pg 199]

ring-billed gull.

From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

[Pg 201]

THE MOCKING BIRD.

HE Mocking Bird is regarded as

the chief of songsters, for in

addition to his remarkable

powers of imitation, he is

without a rival in variety of notes.

The Brown Thrasher is thought by

many to have a sweeter song, and one

equally vigorous, but there is a bold

brilliancy in the performance of the

Mocker that is peculiarly his own, and

which has made him par excellence

the forest extemporizer of vocal melody.

About this of course there will

always be a difference of opinion, as

in the case of the human melodists.

So well known are the habits and

characteristics of the Mocking Bird

that nearly all that could be written

about him would be but a repetition

of what has been previously said.

In Illinois, as in many other states,

its distribution is very irregular, its

absence from some localities which

seem in every way suited being very

difficult to account for. Thus, according

to “Birds of Illinois,” while one or

two pairs breed in the outskirts of

Mount Carmel nearly every season, it

is nowhere in that vicinity a common

bird. A few miles further north, however,

it has been found almost abundant.

On one occasion, during a three

mile drive from town, six males were

seen and heard singing along the roadside.

Mr. H. K. Coale says that he

saw a mocking bird in Stark county,

Indiana, sixty miles southeast of Chicago,

January 1, 1884; that Mr.

Green Smith had met with it at Kensington

Station, Illinois, and that several

have been observed in the parks

and door-yards of Chicago. In the

extreme southern portion of the state

the species is abundant, and is resident

through the year.

The Mocking Bird does not properly

belong among the birds of the middle

or eastern states, but as there are

many records of its nesting in these

latitudes it is thought to be safe to

include it. Mrs. Osgood Wright states

that individuals have often been seen

in the city parks of the east, one having

lived in Central Park, New York

city, late into the winter, throughout

a cold and extreme season. They

have reared their young as far north

as Arlington, near Boston, where they

are noted, however, as rare summer

residents. Dr. J. A. Allen, editor of The

Auk, notes that they occasionally nest

in the Connecticut Valley.

The Mocking Bird has a habit of

singing and fluttering in the middle of

the night, and in different individuals

the song varies, as is noted of many

birds, particularly canaries. The song

is a natural love song, a rich dreamy

melody. The mocking song is imitative

of the notes of all the birds of

field, forest, and garden, broken into

fragments.

The Mocker’s nest is loosely made

of leaves and grass, rags, feathers, etc.,

plain and comfortable. It is never far

from the ground. The eggs are four

to six, bluish green, spattered with

shades of brown.

Wilson’s description of the Mocking

Bird’s song will probably never be

surpassed: “With expanded wings and

tail glistening with white, and the

bouyant gayety of his action arresting

the eye, as his song does most irresistably

the ear, he sweeps around with

enthusiastic ecstasy, and mounts and

descends as his song swells or dies

away. And he often deceives the

sportsman, and sends him in search of

birds that are not perhaps within miles

of him, but whose notes he exactly

imitates.”

Very useful is he, eating large spiders

and grasshoppers, and the destructive

cottonworm.

[Pg 202]

THE LOGGERHEAD SHRIKE.

RAMBLER in the fields and

woodlands during early

spring or the latter part

of autumn is often surprised

at finding insects,

grasshoppers, dragon flies, beetles of

all kinds, and even larger game, mice,

and small birds, impaled on twigs and

thorns. This is apparently cruel

sport, he observes, if he is unacquainted

with the Butcher Bird and his

habits, and he at once attributes it to

the wanton sport of idle children who

have not been led to say,

With hearts to love, with eyes to see,

With ears to hear their minstrelsy;

Through us no harm, by deed or word,

Shall ever come to any bird.

If he will look about him, however,

the real author of this mischief will

soon be detected as he appears with

other unfortunate little creatures,

which he requires to sustain his own

life and that of his nestlings. The

offender he finds to be the Shrike of

the northern United States, most

properly named the Butcher Bird.

Like all tyrants he is fierce and brave

only in the presence of creatures

weaker than himself, and cowers and

screams with terror if he sees a falcon.

And yet, despite this cruel proceeding,

which is an implanted instinct

like that of the dog which buries

bones he never seeks again, there are

few more useful birds than the Shrike.

In the summer he lives on insects,

ninety-eight per cent. of his food for

July and August consisting of insects,

mainly grasshoppers; and in winter,

when insects are scarce, mice form a

very large proportion of his food.

The Butcher Bird has a very agreeable

song, which is soft and musical,

and he often shows cleverness as a

mocker of other birds. He has been

taught to whistle parts of tunes, and

is as readily tamed as any of our

domestic songsters.

The nest is usually found on the

outer limbs of trees, often from fifteen

to thirty feet from the ground. It is

made of long strips of the inner bark

of bass-wood, strengthened on the

sides with a few dry twigs, stems, and

roots, and lined with fine grasses. The

eggs are often six in number, of a

yellowish or clayey-white, blotched

and marbled with dashes of purple,

light brown, and purplish gray.

Pretty eggs to study.

Readers of Birds who are interested

in eggs do not need to disturb the

mothers on their nests in order to see

and study them. In all the great

museums specimens of the eggs of

nearly all birds are displayed in cases,

and accurately colored plates have

been made and published by the

Smithsonian Institution and others.

The Chicago Academy of Sciences has

a fine collection of eggs. Many

persons imagine that these institutions

engage in cruel slaughter of birds in

order to collect eggs and nests. This,

of course, is not true, only the fewest

number being taken, and with the

exclusive object of placing before the

people, not for their amusement but

rather for their instruction, specimens

of birds and animals which shall serve

for their identification in forest and

field.

The Loggerhead Shrike and nest

shown in this number were taken under

the direction of Mr. F. M. Woodruff, at

Worth, Ill., about fourteen miles from

Chicago. The nest was in a corner of

an old hedge of Osage Orange, and

about eight feet from the ground. He

says in the Osprey that it took considerable

time and patience to build

up a platform of fence boards and old

boxes to enable the photographer to

do his work. The half-eaten body of

a young garter snake was found about

midway between the upper surface of

the nest and the limb above, where it

had been hung up for future use.

[Pg 203]

loggerhead shrike.

From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

[Pg 205]

THE BALTIMORE ORIOLE.

ALTIMORE Orioles are inhabitants

of the whole of

North America, from Canada

to Mexico. They

enter Louisiana as soon as

spring commences there. The name

of Baltimore Oriole has been given it,

because its colors of black and orange

are those of the family arms of Lord

Baltimore, to whom Maryland formerly

belonged. Tradition has it that

George Calvert, the first Baron Baltimore,

worn out and discouraged by

the various trials and rigours of temperature

experienced in his Newfoundland

colony in 1628, visited the Virginia

settlement. He explored the

waters of the Chesapeake, and found

the woods and shores teeming with

birds, among them great flocks of

Orioles, which so cheered him by their

beauty of song and splendor of plumage,

that he took them as good omens

and adopted their colors for his

own.

When the Orioles first arrive the

males are in the majority; they sit in

the spruces calling by the hour, with

lonely querulous notes. In a few days

however, the females appear, and then

the martial music begins, the birds’

golden trumpeting often turning to a

desperate clashing of cymbals when

two males engage in combat, for “the

Oriole has a temper to match his flaming

plumage and fights with a will.”

This Oriole is remarkably familiar,

and fearless of man, hanging its beautiful

nest upon the garden trees, and

even venturing into the street wherever

a green tree nourishes. The

materials of which its nest is made are

flax, various kinds of vegetable fibers,

wool, and hair, matted together so as

to resemble felt in consistency. A

number of long horse-hairs are passed

completely through the fibers, sewing

it firmly together with large and irregular,

but strong and judiciously placed

stitching. In one of these nests an

observer found that several of the hairs

used for this purpose measured two

feet in length. The nest is in the

form of a long purse, six or seven

inches in depth, three or four inches

in diameter; at the bottom is arranged

a heap of soft material in which the

eggs find a warm resting place. The

female seems to be the chief architect,

receiving a constant supply of materials

from her mate, occasionally rejecting

the fibers or hairs which he may

bring, and sending him off for another

load more to her taste.

Like human builders, the bird improves

in nest building by practice,

the best specimens of architecture

being the work of the oldest birds,

though some observers deny this.

The eggs are five in number, and

their general color is whitish-pink,

dotted at the larger end with purplish

spots, and covered at the smaller end

with a great number of fine intersecting

lines of the same hue.

In spring the Oriole’s food seems to

be almost entirely of an animal nature,

consisting of caterpillars, beetles, and

other insects, which it seldom pursues

on the wing, but seeks with great

activity among the leaves and branches.

It also eats ripe fruit. The males

of this elegant species of Oriole acquire

the full beauty of their plumage the

first winter after birth.

The Baltimore Oriole is one of the

most interesting features of country

landscape, his movements, as he runs

among the branches of trees, differing

from those of almost all other birds.

Watch him clinging by the feet to

reach an insect so far away as to

require the full extension of the neck,

body, and legs without letting go his

hold. He glides, as it were, along a

small twig, and at other times moves

sidewise for a few steps. His motions

are elegant and stately.

[Pg 206]

THE BALTIMORE ORIOLE.

About the middle of May,

when the leaves are all coming

out to see the bright sunshine,

you may sometimes see, among

the boughs, a bird of beautiful

black and orange plumage.

He looks like the Orchard

Oriole, whose picture you saw

in May “Birds.” It is the Baltimore

Oriole. He has other

names, such as “Golden Robin,”

“Fire Bird,” “Hang-nest.” I

could tell you how he came to

be called Baltimore Oriole, but

would rather you’d ask your

teacher about it. She can tell

you all about it, and an interesting

story it is, I assure you.

You see from the picture why

he is called “Hang-nest.”

Maybe you can tell why he

builds his nest that way.

The Orioles usually select for

their nest the longest and slenderest

twigs, way out on the

highest branches of a large tree.

They like the elm best. From

this they hang their bag-like

nest.

It must be interesting to watch

them build the nest, and it

requires lots of patience, too,

for it usually takes a week or

ten days to build it.

They fasten both ends of a

string to the twigs between

which the nest is to hang. After

fastening many strings like this,

so as to cross one another,

they weave in other strings

crosswise, and this makes a sort

of bag or pouch. Then they put

in the lining.

Of course, it swings and rocks

when the wind blows, and what

a nice cradle it must be for the

baby Orioles?

Orioles like to visit orchards

and eat the bugs, beetles and

caterpillars that injure the trees

and fruit.

There are few birds who do

more good in this way than

Orioles.

Sometimes they eat grapes

from the vines and peck at fruit

on the trees. It is usually because

they want a drink that

they do this.

One good man who had a

large orchard and vineyard

placed pans of water in different

places. Not only the

Orioles, but other birds, would

go to the pan for a drink, instead

of pecking at the fruit. Let us

think of this, and when we have

a chance, give the birds a drink

of water. They will repay us

with their sweetest songs.

[Pg 207]

baltimore oriole.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

[Pg 209]

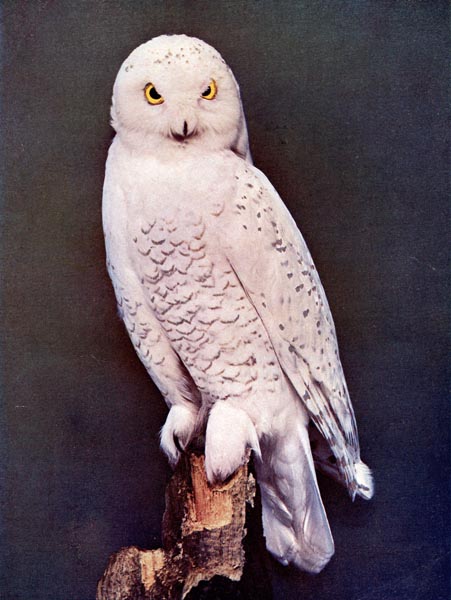

THE SNOWY OWL.

EW of all the groups of birds

have such decided markings,

such characteristic distinctions,

as the Owl. There is a singular

resemblance between the face of an

Owl and that of a cat, which is the

more notable, as both of these creatures

have much the same habits, live

on the same prey, and are evidently

representatives of the same idea in

their different classes. The Owl, in

fact, is a winged cat, just as the cat is

a furred owl.

The Snowy Owl is one of the handsomest

of this group, not so much on

account of its size, which is considerable,

as by reason of the beautiful

white mantle which it wears, and the

large orange eyeballs that shine with

the lustre of a topaz set among the

snowy plumage.

It is a native of the north of Europe

and America, but is also found in the

more northern parts of England, being

seen, though rather a scarce bird, in

the Shetland and Orkney Islands,

where it builds its nest and rears its

young. One will be more likely to

find this owl near the shore, along the

line of salt marshes and woody stubble,

than further inland. The marshes do

not freeze so easily or deep as the iron

bound uplands, and field-mice are more

plentiful in them. It is so fleet of

wing that if its appetite is whetted, it

can follow and capture a Snow Bunting

or a Junco in its most rapid flight.

Like the Hawk Owl, it is a day-flying

bird, and is a terrible foe to the

smaller mammalia, and to various

birds. Mr. Yarrell in his “History of

the British Birds,” states that one

wounded on the Isle of Balta disgorged

a young rabbit whole, and that a young

Sandpiper, with its plumage entire,

was found in the stomach of another.

In proportion to its size the Snowy

Owl is a mighty hunter, having been

detected chasing the American hare,

and carrying off wounded Grouse

before the sportsman could secure his

prey. It is also a good fisherman,

posting itself on some convenient spot

overhanging the water, and securing

its finny prey with a lightning-like

grasp of the claw as it passes beneath

the white clad fisher. Sometimes it

will sail over the surface of a stream,

and snatch the fish as they rise for

food. It is also a great lover of lemmings,

and in the destruction of these

quadruped pests does infinite service

to the agriculturist.

The large round eyes of this owl are

very beautiful. Even by daylight

they are remarkable for their gem-like

sheen, but in the evening they are

even more attractive, glowing like

balls of living fire.

From sheer fatigue these birds often

seek a temporary resting place on

passing ships. A solitary owl, after a

long journey, settled on the rigging of

a ship one night. A sailor who was

ordered aloft, terrified by the two glowing

eyes that suddenly opened upon

his own, descended hurriedly to the

deck, declaring to the crew that he

had seen “Davy Jones a-sitting up

there on the main yard.”

[Pg 210]

THE SNOWY OWL.

What do you think of this bird

with his round, puffy head? You

of course know it is an Owl. I

want you to know him as the

Snowy Owl.

Don’t you think his face is

some like that of your cat?

This fellow is not full grown,

but only a child. If he were full

grown he would be pure white.

The dark color you see is only

the tips of the feathers. You

can’t see his beak very well for

the soft feathers almost cover it.

His large soft eyes look very

pretty out of the white feathers.

What color would you call them?

Most owls are quiet during the

day and very busy all night.

The Snowy Owl is not so quiet

day times. He flies about considerably

and gets most of his

food in daylight.

A hunter who was resting

under a tree, on the bank of a

river, tells this of him:

“A Snowy Owl was perched on

the branch of a dead tree that

had fallen into the river. He

sat there looking into the water

and blinking his large eyes.

Suddenly he reached out and

before I could see how he did it,

a fish was in his claws.”

This certainly shows that he

can see well in the day time. He

can see best, however, in the

twilight, in cloudy weather or

moonlight. That is the way

with your cat.

The wing feathers of the owl

are different from those of most

birds. They are as soft as down.

This is why you cannot hear him

when he flies. Owls while perching

are almost always found in

quiet places where they will not

be disturbed.

Did you ever hear the voice of

an owl in the night? If you

never have, you cannot imagine

how dreary it sounds. He surely

is “The Bird of the Night.”

[Pg 211]

snowy owl.

From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

[Pg 213]

BIRDS AND FARMERS.

From the Forest and Stream.

HE advocates of protection for

our small birds present two

sets of reasons for preventing

their killing; the one sentimental,

and the other economic.

The sentimental reasons are the

ones most often urged; they are also

of a kind to appeal with especial force

to those whose responsibility for the

destruction of the birds is greatest.

The women and girls, for whose adornment

birds’ plumage is chiefly used,

think little and know less about the

services which birds perform for agriculture,

and indeed it may be doubted

whether the sight of a bunch of feathers

or a stuffed bird’s skin suggests to

them any thought of the life that

those feathers once represented. But

when the wearers are reminded that

there was such a life; that it was

cheery and beautiful, and that it was

cut short merely that their apparel

might be adorned, they are quick to

recognize that bird destruction involves

a wrong, and are ready to do their part

toward ending it by refusing to wear

plumage.

The small boy who pursues little

birds from the standpoint of the hunter

in quest of his game, feels only the ardor

of pursuit. His whole mind is concentrated

on that and the hunter’s

selfishness, the desire of possession, fills

his heart. Ignorance and thoughtlessness

destroy the birds.

Every one knows in a general way

that birds render most valuable service

to the farmer, but although these

services have long been recognized in

the laws standing on the statute books

of the various states, it is only within

a few years that any systematic

investigations have been undertaken to

determine just what such services are,

to measure them with some approach to

accuracy, to weigh in the case of each

species the good and the evil done, and

so to strike a balance in favor of the

bird or against it. The inquiries

carried on by the Agricultural Department

on a large scale and those made

by various local experiment stations

and by individual observers have given

results which are very striking and

which can no longer be ignored.

It is a difficult matter for any one to

balance the good things that he reads

and believes about any animal against

the bad things that he actually sees.

The man who witnesses the theft of

his cherries by robin or catbird, or the

killing of a quail by a marsh hawk,

feels that here he has ocular proof of

harm done by the birds, while as to

the insects or the field mice destroyed,

and the crops saved, he has only the

testimony of some unknown and distant

witness. It is only natural that

the observer should trust the evidence

of his senses, and yet his eyes tell him

only a small part of the truth, and that

small part a misleading one.

It is certain that without the services

of these feathered laborers, whose

work is unseen, though it lasts from

daylight till dark through every day

in the year, agriculture in this country

would come to an immediate standstill,

and if in the brief season of fruit

each one of these workers levies on

the farmer the tribute of a few berries,

the price is surely a small one to pay

for the great good done. Superficial

persons imagine that the birds are

here only during the summer, but this

is a great mistake. It is true that in

warm weather, when insect life is

most abundant, birds are also most

abundant. They wage an effective

and unceasing war against the adult

insects and their larvae, and check

their active depredations; but in

winter the birds carry on a campaign

which is hardly less important in its

results.

[Pg 214]

THE SCARLET TANAGER.

NE of the most brilliant and

striking of all American

birds is the Scarlet Tanager.

From its black wings resembling

pockets, it is frequently

called the “Pocket Bird.”

The French call it the “Cardinal.”

The female is plain olive-green, and

when seen together the pair present a

curious example of the prodigality

with which mother nature pours out

her favors of beauty in the adornment

of some of her creatures and seems

niggardly in her treatment of others.

Still it is only by contrast that we are

enabled to appreciate the quality of

beauty, which in this case is of the

rarest sort. In the January number

of Birds we presented the Red Rumped

Tanager, a Costa Rica bird, which,

however, is inferior in brilliancy to

the Scarlet, whose range extends from

eastern United States, north to southern

Canada, west to the great plains,

and south in winter to northern South

America. It inhabits woodlands and

swampy places. The nesting season

begins in the latter part of May, the

nest being built in low thick woods or

on the skirting of tangled thickets;

very often also, in an orchard, on the

horizontal limb of a low tree or sapling.

It is very flat and loosely made

of twigs and fine bark strips and lined

with rootlets and fibers of inner bark.

The eggs are from three to five in

number, and of a greenish blue,

speckled and blotted with brown,

chiefly at the larger end.

The disposition of the Scarlet Tanager

is retiring, in which respect he

differs greatly from the Summer Tanager,

which frequents open groves,

and often visits towns and cities. A

few may be seen in our parks, and

now and then children have picked up

the bright dead form from the green

grass, and wondered what might be its

name. Compare it with the Redbird,

with which it is often confounded, and

the contrast will be striking.

His call is a warble, broken by a

pensive call note, sounding like the

syllables chip-churr, and he is regarded

as a superior musician.

“Passing through an orchard, and

seeing one of these young birds that

had but lately left the nest, I carried

it with me for about half a mile to

show it to a friend, and having procured

a cage,” says Wilson, “hung it

upon one of the large pine trees in the

Botanic Garden, within a few feet of

the nest of an Orchard Oriole, which

also contained young, hoping that the

charity and kindness of the Orioles

would induce them to supply the cravings

of the stranger. But charity with

them as with too many of the human

race, began and ended at home. The

poor orphan was altogether neglected,

and as it refused to be fed by me, I

was about to return it to the place

where I had found it, when, toward

the afternoon, a Scarlet Tanager, no

doubt its own parent, was seen fluttering

around the cage, endeavoring to

get in. Finding he could not, he flew

off, and soon returned with food in

his bill, and continued to feed it until

after sunset, taking up his lodgings on

the higher branches of the same tree.

In the morning, as soon as day broke,

he was again seen most actively engaged

in the same manner, and, notwithstanding

the insolence of the

Orioles, he continued his benevolent

offices the whole day, roosting at night

as before. On the third or fourth day

he seemed extremely solicitous for the

liberation of his charge, using every

expression of distressful anxiety, and

every call and invitation that nature

had put in his power, for him to come

out. This was too much for the feelings

of my friend. He procured a ladder,

and mounting to the spot where the

bird was suspended, opened the cage,

took out his prisoner, and restored him

to liberty and to his parent, who, with

notes of great exultation, accompanied

his flight to the woods.”

[Pg 216]

scarlet tanager.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

[Pg 217]

THE SCARLET TANAGER.

What could be more beautiful

to see than this bird among the

green leaves of a tree? It almost

seems as though he would kindle

the dry limb upon which he

perches. This is his holiday

dress. He wears it during the

nesting season. After the young

are reared and the summer

months gone, he changes his

coat. We then find him dressed

in a dull yellowish green—the

color of his mate the whole year.

Do you remember another bird

family in which the father bird

changes his dress each spring

and autumn?

The Scarlet Tanager is a solitary

bird. He likes the deep

woods, and seeks the topmost

branches. He likes, too, the

thick evergreens. Here he sings

through the summer days. We

often pass him by for he is hidden

by the green leaves above us.

He is sometimes called our

“Bird of Paradise.”

Tanagers feed upon winged

insects, caterpillars, seeds, and

berries. To get these they do

not need to be on the ground.

For this reason it is seldom we

see them there.

Both birds work in building

the nest, and both share in caring

for the little ones. The

nest is not a very pretty one—not

pretty enough for so beautiful

a bird, I think. It is woven

so loosely that if you were standing

under it, you could see light

through it.

Notice his strong, short beak.

Now turn to the picture of the

Rose-Breasted Grosbeaks in

April Birds. Do you see how

much alike they are? They are

near relatives.

I hope that you may all have

a chance to see a Scarlet Tanager

dressed in his richest scarlet

and most jetty black.

[Pg 218]

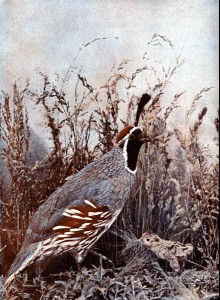

THE RUFFED GROUSE.

HE Ruffed Grouse, which is

called Partridge in New England

and Pheasant in the

Middle and Southern States,

is the true Grouse, while Bob White

is the real Partridge. It is unfortunate

that they continue to be confounded.

The fine picture of his

grouseship, however, which we here

present should go far to make clear

the difference between them.

The range of the Ruffed Grouse is

eastern United States, south to North

Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and

Arkansas. They hatch in April, the

young immediately leaving the nest

with the mother. When they hear

the mother’s warning note the little

ones dive under leaves and bushes,

while she leads the pursuer off in an

opposite direction. Building the nest

and sitting upon the eggs constitute

the duties of the female, the males

during this interesting season keeping

separate, not rejoining their mates

until the young are hatched, when

they begin to roam as a family.

Like the Turkey, the Ruffed Grouse

has a habit of pluming and strutting,

and also makes the drumming noise

which has caused so much discussion.

This noise “is a hollow vibrating

sound, beginning softly and increasing

as if a small rubber ball were dropped

slowly and then rapidly bounced on a

drum.” While drumming the bird

contrives to make himself invisible,

and if seen it is difficult to get the

slightest clue to the manner in which

the sound is produced. And observers

say that it beats with its wings on a

log, that it raises its wings and strikes

their edges above its back, that it claps

them against its sides like a crowing

rooster, and that it beats the air. The

writer has seen a grouse drum, appearing

to strike its wings together over

its back. But there is much difference

of opinion on the subject, and young

observers may settle the question for

themselves. When preparing to drum

he seems fidgety and nervous and his

sides are inflated. Letting his wings

droop, he flaps them so fast that they

make one continuous humming sound.

In this peculiar way he calls his mate,

and while he is still drumming, the

hen bird may appear, coming slyly

from the leaves.

The nest is on the ground, made by

the female of dry leaves and a few

feathers plucked from her own breast.

In this slight structure she lays ten or

twelve cream-colored eggs, specked

with brown.

The eyes of the Grouse are of great

depth and softness, with deep expanding

pupils and golden brown iris.

Coming suddenly upon a young

brood squatted with their mother near

a roadside in the woods, an observer

first knew of their presence by the old

bird flying directly in his face, and

then tumbling about at his feet with

frantic signs of distress and lameness.

In the meantime the little ones scattered

in every direction and were not

to be found. As soon as the parent

was satisfied of their safety, she flew a

short distance and he soon heard her

clucking call to them to come to her

again. It was surprising how quickly

they reached her side, seeming to pop

up as from holes in the ground.

[Pg 220]

ruffed grouse.

From col. F. M. Woodruff.

[Pg 221]

THE RUFFED GROUSE.

At first sight most of you will

think this is a turkey. Well, it

does look very much like one.

He spreads his tail feathers,

puffs himself up, and struts about

like a turkey. You know by

this time what his name is and I

think you can easily see why he

is called Ruffed.

This proud bird and his mate

live with us during the whole

year. They are found usually in

grassy lands and in woods.

Here they build their rude

nest of dried grass, weeds and

the like. You will generally

find it at the foot of a tree, or

along side of an old stump in or

near swampy lands.

The Ruffed Grouse has a

queer way of calling his mate.

He stands on a log or stump,

puffed up like a turkey—just as

you see him in the picture. Then

he struts about for a time just

as you have seen a turkey gobbler

do. Soon he begins to work

his wings—slowly at first, but

faster and faster, until it sounds

like the beating of a drum.

His mate usually answers his

call by coming. They set up

housekeeping and build their

rude nest which holds from eight

to fourteen eggs. As soon as

the young are hatched they can

run about and find their own

food. So you see they are not

much bother to their parents.

When they are a week old they

can fly. The young usually stay

with their parents until next

Spring. Then they start out and

find mates for themselves.

I said at the first that the

Ruffed Grouse stay with us all

the year. In the winter, when

it is very cold, they burrow into

a snowdrift to pass the night.

During the summer they always

roost all night.

[Pg 222]

THE BLACK AND WHITE CREEPING WARBLER.

HIS sprightly little bird is met

with in various sections of the

country. It occurs in all parts

of New England and New

York, and has been found in the interior

as far north as Fort Simpson. It

is common in the Bahamas and most

of the West India Islands, generally as

a migrant; in Texas, in the Indian

Territory, in Mexico, and throughout

eastern America.

Dr. Coues states that this warbler is

a very common summer resident near

Washington, the greater number going

farther north to breed. They arrive

there during the first week in April

and are exceedingly numerous until

May.

In its habits this bird seems to be

more of a creeper than a Warbler. It

is an expert and nimble climber, and

rarely, if ever, perches on the branch

of a tree or shrub. In the manner of

the smaller Woodpecker, the Creepers,

Nuthatches, and Titmice, it moves

rapidly around the trunks and larger

limbs of the trees of the forest in search

of small insects and their larvae. It

is graceful and rapid in movement,

and is often so intent upon its hunt as

to be unmindful of the near presence

of man.

It is found chiefly in thickets, where

its food is most easily obtained, and

has been known to breed in the immediate

vicinity of a dwelling.

The song of this Warbler is sweet

and pleasing. It begins to sing from

its first appearance in May and continues

to repeat its brief refrain at

intervals almost until its departure in

August and September. At first it is

a monotonous ditty, says Nuttall,

uttered in a strong but shrill and filing

tone. These notes, as the season advances,

become more mellow and warbling.

The Warbler’s movements in search

of food are very interesting to the

observer. Keeping the feet together

they move in a succession of short,

rapid hops up the trunks of trees and

along the limbs, passing again to the

bottom by longer flights than in the

ascent. They make but short flight

from tree to tree, but are capable of

flying far when they choose.

They build on the ground. One

nest containing young about a week

old was found on the surface of shelving

rock. It was made of coarse strips

of bark, soft decayed leaves, and dry

grasses, and lined with a thin layer of

black hair. The parents fed their

young in the presence of the observer

with affectionate attention, and showed

no uneasiness, creeping head downward

about the trunks of the neighboring

trees, and carrying large smooth

caterpillars to their young.

They search the crevices in the

bark of the tree trunks and branches,

look among the undergrowth, and

hunt along the fences for bunches of

eggs, the buried larvae of the insects,

which when undisturbed, hatch out

millions of creeping, crawling, and

flying things that devastate garden

and orchard and every crop of the field.

[Pg 224]

black and white creeping warbler.

From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

Chicago Colortype Co.

[Pg 225]

VOLUME 1. JANUARY TO JUNE, 1897.

INDEX.

| Birds, The Return of the | pages | 101 |

| Bird Song | “ | 187-8 |

| Bird Day in the Schools | “ | 129-138 |

| Birds and Farmers | “ | 213 |

| Black Bird, Red-winged, Agelaeus Phœniceus | “ | 64-68-70-71 |

| Blue Bird, Sialia Sialis | “ | 75-76-78 |

| Bobolink, Dolichonyx Gryzivorus | “ | 92-3-4 |

| Bunting, Indigo, Passerina Cyanea | “ | 172-3 |

| Catbird, Galeoscoptes Carolinensis | “ | 183-4-6 |

| Chickadee, Black-capped, Parus Atricopillus | “ | 164-5-7 |

| Cock of the Rock | “ | 19-21 |

| Crossbill, American, Loxia Curvirostra | “ | 126-7 |

| Crow, American, Corvus Americanus | “ | 97-8-100 |

| Duck, Mandarin, A. Galericulata | “ | 8-9-11 |

| Flicker, Colaptes Auratus | “ | 89-90 |

| Fly-catcher, Scissor-tailed, Milvulus Forficatus | “ | 161-3 |

| Gallinule, Purple, Ionoruis Martinica | “ | 120-1 |

| Grebe, Pied-billed, Podilymbus Podiceps | “ | 134-5-7 |

| Grosbeak, Rose-breasted, Habia Ludoviciana | “ | 113-115 |

| Grouse, Ruffed, Bonasa Umbellus | “ | 218-220-221 |

| Gull, Ring-billed, Larus Delawarensis | “ | 198-199 |

| Halo, The | “ | 150 |

| Hawk, Marsh, Circus Hudsonius | “ | 158-159 |

| Hawk, Night, Chordeiles Virginianus | “ | 175-6-8 |

| Heron, Black-crowned, Nycticorax Nycticorax Naevius | “ | 196-7 |

| Jay, American Blue, Cyanocitta Cristata | “ | 39-41 |

| Jay, Arizona Green, Xanthoura Luxuosa | “ | 146-148 |

| Jay, Canada, Perisoreus Canadensis | “ | 116-17-19 |

| Kingfisher, American, Ceryle Alcyon | “ | 60-61-63 |

| Lark, Meadow, Sturnella Magna | “ | 105-7-8 |

| Longspur, Smith’s, Calcarius PictusLongspur, Smith’s, Calcarius Pictus | “ | 123-5 |

| Lory, Blue Mountain | “ | 66-67 |

| Mocking Bird, American, Mimus Polyglottos | “ | 192-193-201 |

| Mot Mot, Mexican | “ | 49-57 |

| Nesting Time | “ | 149-150 |

| Nonpareil, Passerina Ciris | “ | 1-3-15 |

| Oriole, Baltimore, Icterus Galbula | “ | 205-6-7 |

| Oriole, Golden, Icterus Icterus | “ | 34-36 |

| Oriole, Orchard, Icterus Spurius | “ | 154-5 |

| Owl, Long-eared, Asio Wilsonianus | “ | 109-111-112 |

| Owl, Screech, Megascops Asio | “ | 151-3-7 |

| Owl, Snowy, Nyctea Nivea | “ | 209-210-211 |

| Paradise, Red Bird of, Paradisea Rubra | “ | 22-23-25 |

| Parrakeet, Australian | “ | 16-18 |

| Parrot, King | “ | 50-51 |

| Pheasant, Golden, P. Pictus | “ | 12-13 |

| Pheasant, Japan | “ | 86-88 |

| Red Bird, American, Cardinalis Cardinalis | “ | 72-74 |

| Robin, American, Merula Migratoria | “ | 53-4-5-9 |

| Roller, Swallow-tailed, Indian | “ | 42-43 |

| Shrike, Loggerhead, Lanius Ludovicianus | “ | 202-203 |

| Swallow, Barn, Chelidon Erythrogaster | “ | 79-80 |

| Tanager, Red-rumped, Tanagridæ | “ | 30-31-33 |

| Tanager, Scarlet, Piranga Erythromelas | “ | 214-216-217 |

| Tern, Black, Hydrochelidon Ingra Surinamensis | “ | 103-104 |

| Thrush, Brown, Harporhynchus Rufus | “ | 82-83-84 |

| Thrush, Wood, Turdus Mustelinus | “ | 179-180-183 |

| Toucan, Yellow-throated, Ramphastos | “ | 26-27-29 |

| Trogon, Resplendent, Trogonidæ | “ | 4-7 |

| Vireo, Yellow-throated, Vireo Flavifrons | “ | 189-191 |

| Warbler, Black-and-white Creeping, Mniotilta Varia | “ | 222-224 |

| Warbler, Prothonotary, Protonotaria Citrea | “ | 168-169-171 |

| Wax Wing, Bohemian, Ampelis Garrulus | “ | 140-141 |

| Woodpecker, California, Melanerpes Formicivorus Bairdi | “ | 130-131-133 |

| Woodpecker, Red-headed, Melanerpes Erythrocephalus | “ | 45-46-47 |

| Wren, Long-billed Marsh, Cistothorus Palustris | “ | 142-144-145 |

elkhart lake.

Summer Excursion

Tickets to the resorts

of Wisconsin, Minnesota,

Michigan, Colorado, California,

Montana, Washington,

Oregon, and British

Columbia; also to Alaska,

Japan, China, and all Trans-Pacific

Points, are now on

sale by the CHICAGO,

MILWAUKEE & ST.

PAUL RAILWAY. Full

and reliable information

can be had by applying to

Mr. C. N. SOUTHER,

Ticket Agent, 95 Adams

Street, Chicago.

Please mention “BIRDS” when you write to advertisers.

Please mention “BIRDS” when you write to advertisers.

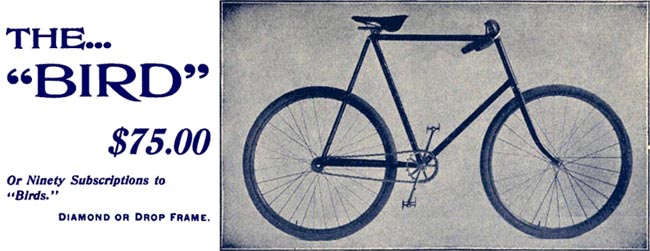

This wheel is made especially for the Nature Study Publishing Co., to be used as a premium. It is unique in

design, of material the best, of workmanship unexcelled. No other wheel on the market can compare favorably

with it for less than $100.00.

SPECIFICATIONS FOR 1897 “BIRD” BICYCLE.

Frame.—Diamond pattern; cold-drawn seamless steel tubing;

11⁄8 inch

tubing in the quadrangle with the exception of the head, which is

11⁄4inch. Height, 23, 24, 25 and 26 inches.

Rear triangle 3⁄4 inch tubing in

the lower and upright bars. Frame Parts.—Steel drop forgings,

strongly reinforced connections. Forks.—Seamless steel fork sides,

gracefully curved and mechanically reinforced. Steering Head.—9, 11

and 13 inches long, 11⁄4

inches diameter. Handle Bar.—Cold-drawn,

weldless steel tubing, 7⁄8 inch in diameter, ram’s horn, upright or

reversible, adapted to two positions. Handles.—Cork or corkaline;

black, maroon or bright tips. Wheels.—28 inch, front and rear. Wheel

Base.—43 inches. Rims.—Olds or Plymouth. Tires.—Morgan & Wright,

Vim, or Hartford. Spokes.—Swaged, Excelsior Needle Co.’s best

quality; 28 in front and 32 in rear wheel. Cranks.—Special steel,

round and tapered; 61⁄2

inch throw. Pedals.—Brandenburg; others on

order. Chain.—1⁄4 inch, solid link, with hardened rivet steel

centers. Saddle.—Black, attractive and comfortable; our own make.

Saddle Post.—Adjustable, style “T.” Tread.

—47⁄8 inches. Sprocket

Wheels.—Steel drop forgings, hardened. Gear.—68 regular; other

gears furnished if so desired. Bearings.—Made of the best selected

high-grade tool steel, carefully ground to a finish after tempering, and

thoroughly dust-proof. All cups are screwed into hubs and crank hangers.

Hubs.—Large tubular hubs, made from a solid bar of steel.

Furnishing.—Tool-bag, wrench, oiler, pump and repair kit. Tool

Bags.—In black or tan leather, as may be preferred. Handle bar, hubs,

sprocket wheels, cranks, pedals, seat post, spokes, screws, nuts and

washers, nickel plated over copper; remainder enameled. Weight.—22

and 24 pounds.

Send for Specifications for Diamond Frame.

NATURE STUDY PUBLISHING CO.

Agents Wanted in every Town and City to represent "BIRDS."

CHICAGO.

Please mention “BIRDS” when you write to advertisers.

We give below a list of publications, especially fine, to be read in

connection with our new magazine, and shall be glad to supply them at

the price indicated, or as premiums for subscriptions for “Birds.”

| “Birds Through an Opera Glass” | 75c. | or | 2 | subscriptions. | ||||

| “Bird Ways” | 60c. | “ | 2 | “ | ||||

| “In Nesting Time” | $1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “A Bird Lover of the West” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Upon the Tree Tops” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Wake Robin” | 1.00 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Birds in the Bush” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “A-Birding on a Bronco” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Land Birds and Game Birds of New England” | 3.50 | “ | 8 | “ | ||||

| “Birds and Poets” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Bird Craft” | 3.00 | “ | 7 | “ | ||||

| “The Story of the Birds” | .65 | “ | 2 | “ | ||||

| “Hand Book of Birds of Eastern North America” | 3.00 | “ | 7 | “ |

See our notice on another page concerning Bicycles. Our “Bird” Wheel is

one of the best on the market—as neat and attractive as “Birds.”

We shall be glad to quote a special price for teachers or clubs.

We can furnish any article or book as premium for subscriptions for

“Birds.”

Address,

Nature Study Publishing Co. Chicago, Ill.

Nature Study Publishing Company.

HE Nature Study Publishing Company is a corporation of educators and

business men organized to furnish correct reproductions of the colors

and forms of nature to families, schools, and scientists. Having secured

the services of artists who have succeeded in photographing and

reproducing objects in their natural colors, by a process whose

principles are well known but in which many of the details are held

secret, we obtained a charter from the Secretary of State in November,

1896, and began at once the preparation of photographic color plates for

a series of pictures of birds.

The first product was the January number of “BIRDS,” a monthly magazine,

containing ten plates with descriptions in popular language, avoiding as

far as possible scientific and technical terms. Knowing the interest

children have in our work, we have included in each number a few pages

of easy text pertaining to the illustrations. These are usually set

facing the plates to heighten the pleasure of the little folks as they

read.

Casually noticed, the magazine may appear to be a children’s publication

because of the placing of this juvenile text. But such is not the case.

Those scientists who cherish with delight the famous handiwork of

Audubon are no less enthusiastic over these beautiful pictures which are

painted by the delicate and scientifically accurate fingers of Light

itself. These reproductions are true. There is no imagination in them

nor conventionalism. In the presence of their absolute truth any written

description or work of human hands shrinks into insignificance. The

scientific value of these photographs can not be estimated.

To establish a great magazine with a world-wide circulation is no light

undertaking. We have been steadily and successfully working towards that

end. Delays have been unavoidable. What was effective for the production

of a limited number of copies was inadequate as our orders increased.

The very success of the enterprise has sometimes impeded our progress.

Ten hundred teachers in Chicago paid subscriptions in ten days. Boards

of Education are subscribing in hundred lots. Improvements in the

process have been made in almost every number, and we are now assured of

a brilliant and useful future.

When “BIRDS” has won its proper place in public favor we shall be

prepared to issue a similar serial on other natural objects, and look

for an equally cordial reception for it.

PREMIUMS.

To teachers we give duplicates of all the pictures on separate sheets

for use in teaching or for decoration.

To other subscribers we give a color photograph of one of the most

gorgeous birds, the Golden Pheasant.

Subscriptions, $1.50 a year including one premium. Those wishing both

premiums may receive them and a year’s subscription for $2.00.

We have just completed an edition of 50,000 back numbers to accommodate

those who wish their subscriptions to date back to January, 1897, the

first number.

We will furnish the first volume, January to June inclusive, well bound

in cloth, postage paid, for $1.25. In Morocco, $2.25.

AGENTS.

10,000 agents are wanted to travel or solicit at home.

We have prepared a fine list of desirable premiums for clubs which any

popular adult or child can easily form. Your friends will thank you for

showing them the magazine and offering to send their money. The work of

getting subscribers among acquaintances is easy and delightful. Agents

can do well selling the bound volume. Vol. 1 is the best possible

present for a young person or for anyone specially interested in nature.

Teachers and others meeting them at institutes do well as our agents.

The magazine sells to teachers better than any other publication because

they can use the extra plates for decoration, language work, nature

study, and individual occupation.

NATURE STUDY PUBLISHING COMPANY,

277 Dearborn Street, Chicago.

Featured Books

The Eight Strokes of the Clock

Maurice Leblanc

ed."Well, I had a great argument with my uncle and aunt last night. Theyabsolutely refuse to sign th...

The Tadpoles of Bufo cognatus Say

Hobart M. Smith

unty State Park,Kansas, and the other lacks data. The second lot contains numeroussizes of tadpoles ...

Natural History of the Bell Vireo, Vireo bellii Audubon

Jon C. Barlow

ntenance of Territory260 Aggressive Behavior of the Female264 Interspecific Relationships2...

Ayesha, the Return of She

H. Rider Haggard

alive. As it was promised in the Caves of Kôr She has returned again. To you therefo...

Forest and Frontiers; Or, Adventures Among the Indians

low my camp, and disappear over the river's bank, at afavorite drinking place. These mighty monarchs...

M. P.'s in Session: From Mr. Punch's Parliamentary Portrait Gallery

Harry Furniss

g 20][Pg 21][Pg 22][Pg 23]THE ROYAL WESTMINSTER ACADEMY.(Splendid Collection of Parliamentary Portra...

The Idiot

John Kendrick Bangs

H TO CHOOSE HIS OWN FACE""JANITORS HAVE TO BE SEEN TO""MY ELOQUENCE FLOATED UP THE AIR-SHAFT"THE IDI...

The Confessions of a Caricaturist, Vol. 1

Harry Furniss