University of Kansas Publications

Museum of Natural History

Volume 9, No. 21, pp. 539-548

January 14, 1960

Pleistocene Pocket Gophers

From San Josecito Cave,

Nuevo León, México

BY

ROBERT J. RUSSELL

University of Kansas

Lawrence

1960

University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, Henry S. Fitch,

Robert W. Wilson

Volume 9, No. 21, pp. 539-548

Published January 14, 1960

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

PRINTED IN

THE STATE PRINTING PLANT

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1960

28-1562

[Pg 541]

Pleistocene Pocket Gophers

From San Josecito Cave, Nuevo León, México

BY

ROBERT J. RUSSELL

Cueva de San Josecito in the province of Aramberri, near the

town on Aramberri, Nuevo León, México, is at an elevation of

approximately 7400 feet above sea level on the east-facing slope

of the Sierra Madre Occidental in a limestone scarp. The dominant

vegetation about the cave is the decidedly boreal forest association

of pine and live oak. Additional information concerning the cave

is provided by Miller (1943:143-144).

Animal remains recovered from San Josecito Cave are among the

most important Pleistocene finds in México, and include the most

extensive collection of Pleistocene geomyids. The vertebrate remains

are probably late Pleistocene in age; certainly they are post-Blancan,

since the genera Equus, Preptoceras, Smilodon, and Aenocyon

(all Pleistocene genera) are present. According to Miller's

(loc. cit.:145) extensive report on the avifauna, the bird remains

from the cave are a remarkable assemblage and beautifully preserved.

Most of the mammalian remains have been studied in

detail, and the results of these studies have been published in a

number of papers each treating specific groups. These reports

provide valuable information concerning the distribution of mammals

in northeastern México in the late Pleistocene, a knowledge of

which is most important to an understanding of present patterns of

distribution and evolution of Mexican mammals.

Cushing's (1945:182-185) report on his study of the rodents and

lagomorphs includes a description of an extinct pygmy species of

rabbit, Sylvilagus leonensis. He records three kinds of pocket

gophers from San Josecito; Cushing was able to separate the genus

Thomomys from two unidentified geomyids (loc. cit.:185). These

prove to belong to the genera Cratogeomys and Heterogeomys; the

materials are described below. Cushing records also larger mammals,

including the antilocaprid (Stockoceros conklingi), saber-toothed

cat (Smilodon), dire wolf (Aenocyon), a large oviboid

(Preptoceras), and deer (loc. cit.:182).

More recently Findley (1953:633-639) has written on the remains

of the family Soricidae taken from the cave, and Hooper (1952:59)[Pg 542]

has studied the bones of the genus Reithrodontomys and found them

not different from those of R. megalotis that inhabits the region of

the cave today. Handley (1955:48) has described a new species of

plecotine bat, Corynorhinus tetralophodon, from the collection.

Jones (1958:389-396) published an account of the bats of San Josecito,

and described a new vampire bat, Desmodus stocki, from the

cave. Jakway (1958:313-327) has reported on the lagomorphs and

rodents in detail, and compared this part of the cave fauna with

that of Rancho La Brea and Papago Spring Cave, Arizona. Jakway

(lit. cit.:323-324) suggests that the fauna from San Josecito is late

Pleistocene, probably contemporaneous with the remains from

Papago Spring Cave and pre-Rancholabrean.

I thank Professor E. Raymond Hall and Dr. Robert W. Wilson for their

permission to examine this material and for critical comments and advice on

the manuscript. The drawings were made by Miss Lucy Remple. The specimens

are a part of the collection of fossil vertebrates formerly belonging to the

California Institute of Technology, but now the property of the Los Angeles

County Museum. The specimens had been lent by the late Professor Chester

Stock to Professor Hall and Dr. Wilson for study and report. All measurements

herein are in millimeters.

Thomomys umbrinus (Richardson)

Material referable to Thomomys consists of a nearly complete

cranium, L.A.C.M. (C.I.T.) No. 3952, with nasals, maxillary teeth,

and lower parts of braincase missing and zygomata broken; four

rami (unnumbered), one of which is badly broken; and two isolated

molariform teeth. The skull has a sphenoidal fissure, a feature

typical of the umbrinus group of Thomomys. The fossil specimens

closely approximate in size the living subspecies Thomomys umbrinus

analogus Goldman. Thomomys is not known from the vicinity

of the cave at the present time and has not been reported

from southwestern Nuevo León, even though there has been

extensive collecting for pocket gophers there in recent years. To

my knowledge the nearest record of occurrence of modern Thomomys

is a series of Thomomys umbrinus analogus from 12 miles east

of San Antonio de las Alazanas at an elevation of 9000 feet in the

state of Coahuila (Baker, 1953:511), approximately 85 miles to the

northwest. The fossil gophers are not from the talus of the cave

floor, which is evidently of subrecent origin, but from the Pleistocene

deposits below. Close resemblance to the living subspecies T. u.

analogus, however, indicates that these remains are not so old as

some of the other geomyid fossils from the cave.

[Pg 543]

Cratogeomys castanops (Baird)

Seven rami pertain to the genus Cratogeomys. All except three,

L.A.C.M. (C.I.T.) Nos. 2974, 2978, and 3954, lack cheek teeth

and the posterior processes are missing on most of the mandibles.

No. 2974 is smaller than the other specimens, and probably is from

a young individual. No. 3954 may have been fossilized at an earlier

date than the other six jaws; however, it is comparable to them in

size and morphology. Also present in the deposits are three limb

bones of Cratogeomys castanops. One, a right humerus bearing

L.A.C.M. (C.I.T.) No. 2982, is slightly larger than that of the

pocket gophers living in the area now. Two tibias, L.A.C.M.

(C.I.T.) Nos. 2983 and 2984, complete the material referable to

this species.

Cratogeomys castanops planifrons (see Russell and Baker, 1955:607)

occurs in the immediate vicinity of San Josecito today. None

of the rami from the cave differs appreciably from those of the

subnubilus group of Cratogeomys castanops, a group of small subspecies

including planifrons, subnubilus, rubellus and peridoneus.

All are small in external measurements and skull and differ markedly

in this respect from the group of large subspecies (the subsimus

group) that occurs farther northward in Coahuila and Nuevo León.

Cratogeomys sp.

A rostral part of a skull, L.A.C.M. (C.I.T.) No. 2927, is referable

to the genus Cratogeomys. This fragment consists of the

anterior part of the skull, including a portion of the frontals, the

premaxillae, a small part of the left maxilla, and the anterior parts

of the palatines. The nasals are missing, but both incisors are in

place including most of the roots. The single median sulcus on the

anterior face of each incisor is typical of the genus Cratogeomys.

The rostrum is long (25.8), as great in length as in the largest

subspecies of the subsimus group of Cratogeomys castanops (see

previous account for explanation) and as long as the rostrum of

Cratogeomys perotensis which is now known only from Veracruz,

México. The length of the rostrum was measured from the most

anterior median projection of the premaxillary to the most posterior

dorsal projection of the same bone. Actually, and especially in

relation to its length, the rostrum of the fossil is remarkably narrow.

The breadth of the rostrum measures 10.4, which is comparable to

that in the subnubilus group of small subspecies, and less than that[Pg 544]

(11.4 in the smaller adult females to 13.7 in the larger adult males)

in the subsimus group of large subspecies. The breadth of rostrum

in the fossil is 40.3 per cent of the length of the rostrum. In living

Cratogeomys castanops (both the large and small subspecies groups,

and including both females and males) the breadth of rostrum

amounts to between 44.0 and 51.4 per cent of its length. The

rostrum in Cratogeomys perotensis (and in other species of the

merriami group) is relatively much broader than in Cratogeomys

castanops. Even though the rostrum of the fossil is narrower than

in Recent species of Cratogeomys, the ventral border in the area of

the palatine slits is more heavily constructed than in any of the

living species, and it is nearly parallel-sided rather than tapered

toward the midline anteriorly. At the lateral edge of the enamel

plate of the incisors there is a distinct shelf, a characteristic of the

merriami group of species and a feature not well developed in

Cratogeomys castanops.

I hestitate to refer this fragment to any of the living species,

although I would judge it to represent a form closer to the species

castanops than to the merriami group (C. perotensis). The rostrum

may represent, and probably does, an undescribed and extinct

species of Cratogeomys, but in my opinion it should not be given

formal taxonomic status until more adequate material is available.

If the fossil is actually Cratogeomys castanops, and if the fragment

is from an earlier deposit in the cave than is the material here

assigned to Cratogeomys castanops, the fossil stock could be ancestral

to the group of small subspecies provided there had been

a trend in evolution toward smaller size. Another possibility is

that a shift in geographic range of the kinds of Cratogeomys that

lived in the vicinity of the cave has occurred, and that the fossil

represents an evolutionary line with no close relationship to Recent

species and now is extinct. Additional material is needed before

the history of these species can be reconstructed with validity.

Heterogeomys onerosus new species

Holotype.—Los Angeles County Museum (C.I.T.) No. 2384, an incomplete

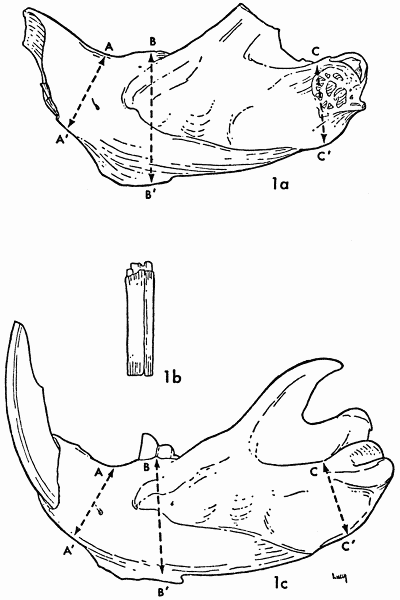

left ramus, bearing incisor and p4; the alveolus of m1-m3 is present (Fig. 1a).

Paratypes: Two isolated and unnumbered right upper incisors, one isolated

premolar, and five additional rami, Nos. 2385, 2386, 2388, and two with no

number.

Horizon and type locality.—Upper Pleistocene, Cueva de San Josecito,

province of Aramberri, near the town of Aramberri, Nuevo León, México;

California Institute of Technology, Vertebrate Paleontology Locality 192.

[Pg 545]

Description of Holotype.—Differs from any known living species

of Heterogeomys, by the significantly heavier and deeper ramus

(see Table 1 and Fig. 1). The holotype is compared with the

largest adult male of Heterogeomys hispidus (H. torridus is smaller

than hispidus) available to me in Table 1. Relative to the length

of the ramus (measured from the anterior mental foramen to the

posterior margin of the capsule that surrounds the root of the lower

incisor), the depth of the ramus anterior to the molariform tooth-row

is 33.0 per cent in H. onerosus compared with 27.3 per cent in

H. hispidus. If the fossil ramus is that of a female (females are

significantly smaller than males in Heterogeomys) then the differences

would be greater than recorded.

Table 1. Depth of Mandibular Ramus

|

Least depth in front of premolar

(See A to A′ on Fig. 1c) |

Depth of ramus opposite re-entrant angle of p4

(B to B′ on Fig. 1c) |

Depth from a point in front of capsule for incisor

(See C to C′ on Fig. 1c) |

| H. onerosus holotype |

11.0 |

17.4 |

11.7 |

| H. h. hispidus ad., 23979 KU |

9.1 |

15.2 |

10.5 |

The angle between the anterior border of the coronoid process

and the dorsal border of the ramus of the mandible is more acute,

and the posteroventral margin of the ramus is more nearly straight,

in onerosus than in hispidus. The molariform tooth-row in onerosus

is only slightly longer (13.9 in contrast to 13.5) than in hispidus

and torridus. The ventral border of the massenteric ridge is weakly

developed in onerosus and hardly discernable whereas in the living

species of Heterogeomys the massenteric ridge is strongly developed

posteriorly forming a noticeable prominence.

Description of Paratypes.—The fossils are referable to the genus

Heterogeomys on the basis of the short lateral angular processes of

the lower jaw and on the basis of the associated upper incisors,

which have a single distinct sulcus that lies toward the inner margin

of each tooth. The isolated lower premolar that is referred to the

new species is as large as that of the holotype and has the enamel

pattern of Heterogeomys.[Pg 546]

Figs. 1a-1c. × 1½

Fig. 1a. Heterogeomys onerosus, lateral view

of left lower jaw of holotype.

Fig. 1b. Heterogeomys onerosus, front view of right,

upper incisor.

Fig. 1c. Heterogeomys hispidus, lateral view of left

lower jaw, No. 23979, adult, from 3 km. E

San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz.

One jaw fragment, L.A.C.M. (C.I.T.) No. 2368, is smaller

than the others and probably is from a young individual. Two

others L.A.C.M. (C.I.T.) No. 2384 and one unnumbered, are

smaller than the holotype, and possibly are the remains of females;

however, they have the same characteristic shape as the holotype.

Nevertheless, the two rami mentioned above are significantly larger

than in adult males of modern Heterogeomys and are especially

larger than in females. Another jaw fragment, L.A.C.M. (C.I.T.)[Pg 547]

No. 2385, is seemingly as large as, or perhaps larger than, the holotype,

although the posterior part of the ramus behind the alveolus

of m2 is missing. An additional unnumbered ramus is of somewhat

lighter construction than the holotype, but is important since it

bears not only the incisor and p4 but also the first two lower molars.

The only other material referable to Heterogeomys onerosus is a

fragmentary and isolated lower molar tooth that has a single posterior

enamel blade, a feature characteristic of a number of Recent

genera of pocket gophers, and some limb bones which are slightly

larger than corresponding elements in Recent species of Heterogeomys.

Remarks.—Pocket gophers do not inhabit caves; therefore gophers

were brought into the cavern probably by birds of prey, the remains

of which were common in the deposits (Miller, 1943:152-156), or

conceivably by carnivorous mammals. Since most of the raptorial

predators that would prey on pocket gophers do not have a wide

hunting territory, it is likely that the gophers were taken within

a short distance of the cave. The presence of the genus Heterogeomys

in the deposits strongly suggests a tropical situation in the

vicinity of the cave when these gophers were taken, because the

distribution of this genus today is entirely within the Tropical

Life-zone.

Since the presumably early time when tropical conditions, or more

nearly tropical conditions, prevailed at San Josecito Cave, climatic

shifts account for a humid boreal environment there and its associated

fauna. Findley (lit. cit.:635-636) reports from San Josecito

the remains of the boreal shrew Sorex cinereus that today occurs no

nearer than 800 miles to the northward in the mountains of north-central

New Mexico. As he points out, that species requires hydric

communities of cool climates, and in the Wisconsin Glacial age such

climates probably prevailed in the high mountainous region where

San Josecito is located. Since the time when a more mesic boreal

environment occurred at San Josecito, climatic shifts have favored

more xeric conditions as are found in the vicinity of the cave today.

The more arid environments would support the occurrence of Cratogeomys

and Thomomys; however the ecological affinities of the

fragment here referred to Cratogeomys sp. are unknown.

The more nearly tropical environment there could have occurred

either during a Wisconsin interglacial period or during the Sangamon

Interglacial age. Heterogeomys onerosus perhaps lived near

the cave during an interglacial period; since then it became extinct[Pg 548]

or evolved into the Recent species Heterogeomys hispidus. Heterogeomys

has not previously been recorded from Pleistocene or

earlier deposits.

LITERATURE CITED

Baker, R. H.

1953. The pocket gophers (genus Thomomys) of Coahuila, México.

Univ. Kansas Publ., Mus. Nat. Hist., 5:499-514, 1 fig. in text,

June 1.

Cushing, J. E., Jr.

1945. Quaternary rodents and lagomorphs of San Josecito Cave, Nuevo

León, México. Jour. Mamm., 26:182-185, July 19.

Findley, J. S.

1953. Pleistocene Soricidae from San Josecito Cave, Nuevo León, México.

Univ. Kansas Publ., Mus. Nat. Hist., 5:633-639, December 1.

Handley, C. O., Jr.

1955. A new Pleistocene bat (Corynorhinus) from México. Jour. Washington

Acad. Sci., 45:48-49, March 14.

Hooper, E. T.

1952. A systematic review of the harvest mice (genus Reithrodontomys)

of Latin America. Miscl. Publ. Mus. Zool., Univ. Michigan, 77:1-255,

9 pls., 24 figs., 12 maps, January 16.

Jakway, G. E.

1958. Pleistocene Lagomorpha and Rodentia from the San Josecito Cave,

Nuevo León, México. Trans. Kansas Acad. Sci., 61:313-327, November 21.

Jones, J. K., Jr.

1958. Pleistocene bats from San Josecito Cave, Nuevo León, México.

Univ. Kansas Publ., Mus. Nat. Hist., 9:389-396, 4 figs., December 19.

Miller, L.

1943. The Pleistocene birds of San Josecito Cavern, México. Univ. California

Publ. Zool., 47:143-168, April 20.

Russell, R. J., and Baker, R. H.

1955. Geographic variation in the pocket gopher, Cratogeomys cantanops,

in Coahuila, México. Univ. Kansas Publ., Mus. Nat. Hist., 7:591-608,

1 fig., March 15.

Transmitted October 28, 1959.

◻

28-1562

Transcriber's Note

The proportion

( × 1½) in the figure caption is taken from the original

text; actual size may be larger or smaller, depending on your

monitor.

The following errors are noted, but left as printed:

Page 541, "the town on Aramberri" should be "the town of Aramberri"

Page 544, "I hestitate to refer" should be "I hesitate to refer"

Comments on "Pleistocene Pocket Gophers From San Josecito Cave, Nuevo Leon, Mexico" :