The Project Gutenberg eBook of Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances

Author: James Branch Cabell

Illustrator: Frank Cheyne Papé

Release date: March 1, 2004 [eBook #11639]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell, Project Gutenberg Beginners Projects, Sandra Brown,

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIGURES OF EARTH: A COMEDY OF APPEARANCES ***

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Figures of Earth, by James Branch Cabell,

Illustrated by Frank C. Pape

Figures of Earth

James Branch Cabell

A Comedy of Appearances

1921

Illustrated by Frank C. Papé

"Cascun se mir el jove Manuel,

Qu'era del mom lo plus valens dels pros."

List of Illustrations

"He Was Drying Out In the

Sun"

"Summons the

Stork"

Contents

AUTHOR'S NOTE

A FOREWORD

PART ONE

THE BOOK OF CREDIT

CHAPTER

I HOW MANUEL LEFT THE MIRE

II NIAFER

III ASCENT OF VRAIDEX

IV IN THE DOUBTFUL PALACE

V THE ETERNAL AMBUSCADE

VI ECONOMICS OF MATH

VII THE CROWN OF WISDOM

VIII THE HALO OF

HOLINESS

IX THE FEATHER OF LOVE

PART TWO

THE BOOK OF SPENDING

X ALIANORA

XI MAGIC OF THE APSARASAS

XII ICE AND IRON

XIII WHAT HELMAS

DIRECTED

XIV THEY DUEL ON MORVEN

XV BANDAGES FOR THE

VICTOR

PART THREE

THE BOOK OF CAST ACCOUNTS

XVI FREYDIS

XVII MAGIC OF THE

IMAGE-MAKERS

XVIII MANUEL CHOOSES

XIX THE HEAD OF MISERY

XX THE MONTH OF YEARS

XXI TOUCHING REPAYMENT

XXII RETURN OF NIAFER

XXIII MANUEL GETS HIS

DESIRE

XXIV THREE WOMEN

PART FOUR

THE BOOK OF SURCHARGE

XXV AFFAIRS IN POICTESME

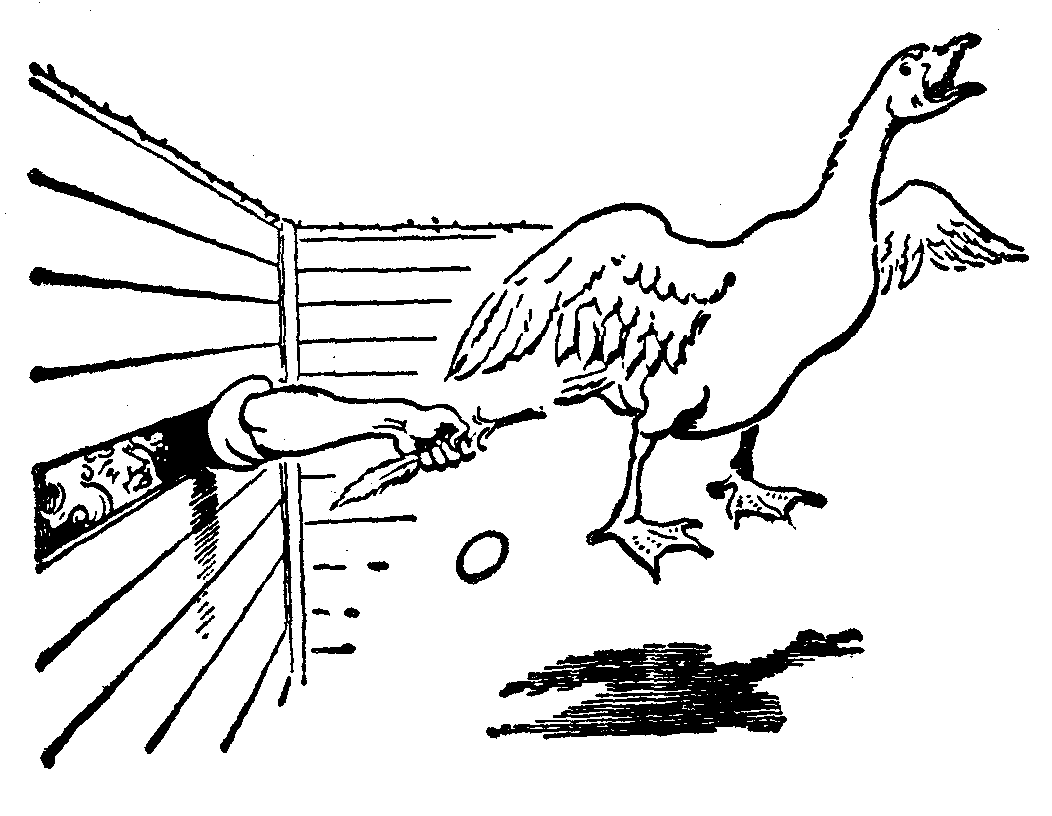

XXVI DEALS WITH THE

STORK

XXVII THEY COME TO

SARGYLL

XXVIII HOW MELICENT WAS

WELCOMED

XXIX SESPHRA OF THE

DREAMS

XXX FAREWELL TO FREYDIS

XXXI STATECRAFT

XXXII THE REDEMPTION OF

POICTESME

PART FIVE

THE BOOK OF SETTLEMENT

XXIII NOW MANUEL

PROSPERS

XXXIV FAREWELL TO

ALIANORA

XXXV THE TROUBLING

WINDOW

XXXVI EXCURSIONS FROM

CONTENT

XXXVII OPINIONS OF

HINZELMANN

XXXVIII FAREWELL TO

SUSKIND

XXXIX THE PASSING OF

MANUEL

XL COLOPHON: DA CAPO

To

SIX MOST GALLANT CHAMPIONS

Is dedicated this history of a champion: less to repay than to

acknowledge large debts to each of them, collectively at outset, as

hereafter seriatim.

Author's Note

Figures of Earth is, with some superficial air of paradox, the

one volume in the long Biography of Dom Manuel's life which deals

with Dom Manuel himself. Most of the matter strictly appropriate to

a Preface you may find, if you so elect, in the Foreword addressed

to Sinclair Lewis. And, in fact, after writing two prefaces to this

"Figures of Earth"—first, in this epistle to Lewis, and,

secondly, in the remarks 1 affixed

to the illustrated edition,—I had thought this volume could

very well continue to survive as long as its deficiencies permit,

without the confection of a third preface, until I began a little

more carefully to consider this romance, in the seventh year of its

existence.

But now, now, the deficiency which I note in chief (like the

superior officer of a disastrously wrecked crew) lies in the fact

that what I had meant to be the main "point" of "Figures of Earth,"

while explicitly enough stated in the book, remains for every

practical end indiscernible.... For I have written many books

during the last quarter of a century. Yet this is the only one of

them which began at one plainly recognizable instant with one

plainly recognizable imagining. It is the only book by me which

ever, virtually, came into being, with its goal set, and with its

theme and its contents more or less pre-determined throughout,

between two ticks of the clock.

Egotism here becomes rather unavoidable. At Dumbarton Grange the

library in which I wrote for some twelve years was lighted by three

windows set side by side and opening outward. It was in the instant

of unclosing one of these windows, on a fine afternoon in the

spring of 1919, to speak with a woman and a child who were then

returning to the house (with the day's batch of mail from the post

office), that, for no reason at all, I reflected it would be, upon

every personal ground, regrettable if, as the moving window

unclosed, that especial woman and that particular child proved to

be figures in the glass, and the window opened upon nothingness.

For that, I believed, was about to happen. There would be, I knew,

revealed beyond that moving window, when it had opened all the way,

not absolute darkness, but a gray nothingness, rather sweetly

scented.... Well! there was not. I once more enjoyed the quite

familiar experience of being mistaken. It is gratifying to record

that nothing whatever came of that panic surmise, of that

second-long nightmare—of that brief but over-tropical

flowering, for all I know, of indigestion,—save, ultimately,

the 80,000 words or so of this book.

For I was already planning, vaguely, to begin on, later in that

year, "the book about Manuel." And now I had the germ of

it,—in the instant when Dom Manuel opens the over-familiar

window, in his own home, to see his wife and child, his lands, and

all the Poictesme of which he was at once the master and the main

glory, presented as bright, shallow, very fondly loved illusions in

the protective glass of Ageus. I knew that the fantastic thing

which had not happened to me,—nor, I hope, to

anybody,—was precisely the thing, and the most important

thing, which had happened to the gray Count of Poictesme.

So I made that evening a memorandum of that historical

circumstance; and for some months this book existed only in the

form of that memorandum. Then, through, as it were, this wholly

isolated window, I began to grope at "the book about

Manuel,"—of whom I had hitherto learned only, from my other

romances, who were his children, and who had been the sole witness

of Dom Manuel's death, inasmuch as I had read about that also, with

some interest, in the fourth chapter of "Jurgen"; and from the

unclosing of this window I developed "Figures of Earth," for the

most part toward, necessarily, anterior events. For it seemed to

me—as it still seems,—that the opening of this

particular magic casement, upon an outlook rather more perilous

than the bright foam of fairy seas, was alike the climax and the

main "point" of my book.

Yet this fact, I am resignedly sure, as I nowadays appraise this

seven-year-old romance, could not ever be detected by any reader of

"Figures of Earth," In consequence, it has seemed well here to

confess at some length the original conception of this volume,

without at all going into the value of that conception, nor into,

heaven knows, how this conception came so successfully to be

obscured.

So I began "the book about Manuel" that summer,—in 1919,

upon the back porch of our cottage at the Rockbridge Alum Springs,

whence, as I recall it, one could always, just as Manuel did upon

Upper Morven, regard the changing green and purple of the mountains

and the tall clouds trailing northward, and could observe that the

things one viewed were all gigantic and lovely and seemed not to be

very greatly bothering about humankind. I suppose, though, that, in

point of fact, it occasionally rained. In any case, upon that same

porch, as it happened, this book was finished in the summer of

1920.

And the notes made at this time as to "Figures of Earth" show

much that nowadays is wholly incomprehensible. There was once an

Olrun in the book; and I can recall clearly enough how her part in

the story was absorbed by two of the other characters,—by

Suskind and by Alianora. Freydis, it appears, was originally called

Hlif. Miramon at one stage of the book's being, I find with real

surprise, was married en secondes noces to Math. Othmar has

lost that prominence which once was his. And it seems, too, there

once figured in Manuel's heart affairs a Bel-Imperia, who, so near

as I can deduce from my notes, was a lady in a tapestry. Someone

unstitched her, to, I imagine, her destruction, although I suspect

that a few skeins of this quite forgotten Bel-Imperia endure in the

Radegonde of another tale.

Nor can I make anything whatever of my notes about Guivret (who

seems to have been in no way connected with Guivric the Sage), nor

about Biduz, nor about the Anti-Pope,—even though, to be

sure, one mention of this heresiarch yet survives in the present

book. I am wholly baffled to read, in my own penciling, such

proposed chapter headings as "The Jealousy of Niafer" and "How

Sclaug Loosed the Dead,"—which latter is with added

incomprehensibility annotated "(?Phorgemon)." And "The Spirit Who

Had Half of Everything" seems to have been exorcised pretty

thoroughly.... No; I find the most of my old notes as to this book

merely bewildering; and I find, too, something of pathos in these

embryons of unborn dreams which, for one cause or another, were

obliterated and have been utterly forgotten by their creator, very

much as in this book vexed Miramon Lluagor twists off the head of a

not quite satisfactory, whimpering design, and drops the valueless

fragments into his waste-basket.... But I do know that the entire

book developed, howsoever helterskelter, and after fumbling in no

matter how many blind alleys, from that first memorandum about the

troubling window of Ageus. All leads toward—and

through—that window.

The book, then, was published in the February of 1921. I need

not here deal with its semi-serial appearance in the guise of short

stories: these details are recorded elsewhere. But I confess with

appropriate humility that the reception of "Figures of Earth" by

the public was, as I have written in another place, a depressing

business. This romance, at that time, through one extraneous reason

and another, disappointed well-nigh everybody, for all that it has

since become, so near as I can judge, the best liked of my books,

especially among women. It seems, indeed, a fact sufficiently

edifying that, in appraising the two legendary heroes of Poictesme,

the sex of whom Jurgen esteemed himself a connoisseur, should,

almost unanimously, prefer Manuel.

For the rest,—since, as you may remember, this is the

third preface which I have written for this book,—I can but

repeat more or less what I have conceded elsewhere. This "Figures

of Earth" appeared immediately following, and during the temporary

sequestration of, "Jurgen." The fact was forthwith, quite

unreticently, discovered that in "Figures of Earth" I had not

succeeded in my attempt to rewrite its predecessor: and this crass

failure, so open, so flagrant, and so undeniable, caused what I can

only describe as the instant and overwhelming and universal triumph

of "Figures of Earth" to be precisely what did not occur. In 1921

Comstockery still surged, of course, in full cry against the

imprisoned pawnbroker and the crimes of his author, both literary

and personal; and the, after all, tolerably large portion of the

reading public who were not disgusted by Jurgen's lechery were now,

so near as I could gather, enraged by Manuel's lack of it.

It followed that—among the futile persons who use serious,

long words in talking about mere books,—aggrieved reproof of

my auctorial malversations, upon the one ground or the other,

became in 1921 biloquial and pandemic. Not many other volumes, I

believe, have been burlesqued and cried down in the public prints

by their own dedicatees.... But from the cicatrix of that healed

wound I turn away. I preserve a forgiving silence, comparable to

that of Hermione in the fifth act of "A Winter's Tale": I resolve

that whenever I mention the names of Louis Untermeyer and H.L.

Mencken it shall be in some connection more pleasant, and that here

I will not mention them at all.

Meanwhile the fifteen or so experiments in contrapuntal prose

were, in particular, uncharted passages from which I stayed unique

in deriving pleasure where others found bewilderment and no

tongue-tied irritation: but, in general, and above every

misdemeanor else, the book exasperated everybody by not being a

more successfully managed re-hashing of the then notorious

"Jurgen."

Since 1921, and since the rehabilitation of "Jurgen," the notion

has uprisen, gradually, among the more bold and speculative

thinkers, that perhaps I was not, after all, in this "Figures of

Earth" attempting to rewrite "Jurgen": and Manuel has made his own

friend.

James Branch Cabell

Richmond-in-Virginia

30 April 1927

Footnote 1: (return)Omitted in this edition since it was not possible to include all

of Frank C. Papé's magnificent illustrations.—THE

PUBLISHER

A FOREWORD

"Amoto quoeramus seria ludo"

To

SINCLAIR LEWIS

A Foreword

MY DEAR LEWIS:

To you (whom I take to be as familiar with the Manuelian cycle

of romance as is any person now alive) it has for some while

appeared, I know, a not uncurious circumstance that in the Key

to the Popular Tales of Poictesme there should have been

included so little directly relative to Manuel himself. No reader

of the Popular Tales (as I recall your saying at the Alum

when we talked over, among so many other matters, this monumental

book) can fail to note that always Dom Manuel looms obscurely in

the background, somewhat as do King Arthur and white-bearded

Charlemagne in their several cycles, dispensing justice and

bestowing rewards, and generally arranging the future, for the

survivors of the outcome of stories which more intimately concern

themselves with Anavalt and Coth and Holden, and with Kerin and

Ninzian and Gonfal and Donander, and with Miramon (in his

rôle of Manuel's seneschal), or even with Sclaug and

Thragnar, than with the liege-lord of Poictesme. Except in the old

sixteenth-century chapbook (unknown to you, I believe, and never

reprinted since 1822, and not ever modernized into any cognizable

spelling), there seems to have been nowhere an English rendering of

the legends in which Dom Manuel is really the main figure.

Well, this book attempts to supply that desideratum, and is, so

far as the writer is aware, the one fairly complete epitome in

modern English of the Manuelian historiography not included by

Lewistam which has yet been prepared.

It is obvious, of course, that in a single volume of this bulk

there could not be included more than a selection from the great

body of myths which, we may assume, have accumulated gradually

round the mighty though shadowy figure of Manuel the Redeemer.

Instead, my aim has been to make choice of such stories and

traditions as seemed most fit to be cast into the shape of a

connected narrative and regular sequence of events; to lend to all

that wholesome, edifying and optimistic tone which in

reading-matter is so generally preferable to mere intelligence; and

meanwhile to preserve as much of the quaint style of the gestes as

is consistent with clearness. Then, too, in the original mediaeval

romances, both in their prose and metrical form, there are

occasional allusions to natural processes which make these stories

unfit to be placed in the hands of American readers, who, as a

body, attest their respectability by insisting that their parents

were guilty of unmentionable conduct; and such passages of course

necessitate considerable editing.

II

No schoolboy (and far less the scholastic chronicler of those

last final upshots for whose furtherance "Hannibal invaded Rome and

Erasmus wrote in Oxford cloisters") needs nowadays to be told that

the Manuel of these legends is to all intents a fictitious person.

That in the earlier half of the thirteenth century there was ruling

over the Poictoumois a powerful chieftain named Manuel, nobody has

of late disputed seriously. But the events of the actual human

existence of this Lord of Poictesme—very much as the Emperor

Frederick Barbarossa has been identified with the wood-demon

Barbatos, and the prophet Elijah, "caught up into the chariot of

the Vedic Vayu," has become one with the Slavonic Perun,—have

been inextricably blended with the legends of the Dirghic

Manu-Elul, Lord of August.

Thus, even the irregularity in Manuel's eyes is taken by

Vanderhoffen, in his Tudor Tales, to be a myth connecting

Manuel with the Vedic Rudra and the Russian Magarko and the Servian

Vii,—"and every beneficent storm-god represented with his eye

perpetually winking (like sheet lightning), lest his concentrated

look (the thunderbolt) should reduce the universe to ashes.... His

watery parentage, and the storm-god's relationship with a

swan-maiden of the Apsarasas (typifying the mists and clouds), and

with Freydis the fire queen, are equally obvious: whereas Niafer is

plainly a variant of Nephthys, Lady of the House, whose personality

Dr. Budge sums up as 'the goddess of the death which is not

eternal,' or Nerthus, the Subterranean Earth, which the warm

rainstorm quickens to life and fertility."

All this seems dull enough to be plausible. Yet no less an

authority than Charles Garnier has replied, in rather indignant

rebuttal: "Qu'ont étè en réalité Manuel

et Siegfried, Achille et Rustem? Par quels exploits ont-ils

mérité l'éternelle admiration que leur ont

vouée les hommes de leur race? Nul ne répondra jamais

à ces questions.... Mais Poictesme croit à la

réalité de cette figure que ses romans ont faite si

belle, car le pays n'a pas d'autre histoire. Cette figure du Comte

Manuel est réelle d'ailleurs, car elle est l'image

purifiée de la race qui l'a produite, et, si on peut

s'exprimer ainsi, l'incarnation de son génie."

—Which is quite just, and, when you come to think it over,

proves Dom Manuel to be nowadays, for practical purposes, at least

as real as Dr. Paul Vanderhoffen.

III

Between the two main epic cycles of Poictesme, as embodied in

Les Gestes de Manuel and La Haulte Histoire de

Jurgen, more or less comparison is inevitable. And Codman, I

believe, has put the gist of the matter succinctly enough.

Says Codman: "The Gestes are mundane stories, the History is a

cosmic affair, in that, where Manuel faces the world, Jurgen

considers the universe.... Dom Manuel is the Achilles of Poictesme,

as Jurgen is its Ulysses."

And, roughly, the distinction serves. Yet minute consideration

discovers, I think, in these two sets of legends a more profound,

if subtler, difference, in the handling of the protagonist: with

Jurgen all of the physical and mental man is rendered as a matter

of course; whereas in dealing with Manuel there is, always, I

believe, a certain perceptible and strange, if not inexplicable,

aloofness. Manuel did thus and thus, Manuel said so and so, these

legends recount: yes, but never anywhere have I detected any firm

assertion as to Manuel's thoughts and emotions, nor any peep into

the workings of this hero's mind. He is "done" from the outside,

always at arm's length. It is not merely that Manuel's nature is

tinctured with the cool unhumanness of his father the water-demon:

rather, these old poets of Poictesme would seem, whether of

intention or no, to have dealt with their national hero as a

person, howsoever admirable in many of his exploits, whom they have

never been able altogether to love, or entirely to sympathize with,

or to view quite without distrust.

There are several ways of accounting for this

fact,—ranging from the hurtful as well as beneficent aspect

of the storm-god, to the natural inability of a poet to understand

a man who succeeds in everything: but the fact is, after all, of no

present importance save that it may well have prompted Lewistam to

scamp his dealings with this always somewhat ambiguous Manuel, and

so to omit the hereinafter included legends, as unsuited to the

clearer and sunnier atmosphere of the Popular Tales.

For my part, I am quite content, in this Comedy of Appearances,

to follow the old romancers' lead. "Such and such things were said

and done by our great Manuel," they say to us, in effect: "such and

such were the appearances, and do you make what you can of

them."

I say that, too, with the addition that in real life, also, such

is the fashion in which we are compelled to deal with all

happenings and with all our fellows, whether they wear or lack the

gaudy name of heroism.

Dumbarton Grange

October, 1920

PART ONE

THE BOOK OF CREDIT

TO

WILSON FOLLETT

Then answered the Magician dredefully: Manuel, Manuel, now I

shall shewe unto thee many bokes of Nygromancy, and howe

thou shalt cum by it lyghtly and knowe the practyse therein. And,

moreouer, I shall shewe and informe you so that thou shall have thy

Desyre, whereby my thynke it is a great Gyfte for so lytyll a

doynge.

I

How Manuel Left the Mire

They of Poictesme narrate that in the old days when miracles

were as common as fruit pies, young Manuel was a swineherd, living

modestly in attendance upon the miller's pigs. They tell also that

Manuel was content enough: he knew not of the fate which was

reserved for him.

Meanwhile in all the environs of Rathgor, and in the thatched

villages of Lower Targamon, he was well liked: and when the young

people gathered in the evening to drink brandy and eat nuts and

gingerbread, nobody danced more merrily than Squinting Manuel. He

had a quiet way with the girls, and with the men a way of solemn,

blinking simplicity which caused the more hasty in judgment to

consider him a fool. Then, too, young Manuel was very often

detected smiling sleepily over nothing, and his gravest care in

life appeared to be that figure which Manuel had made out of marsh

clay from the pool of Haranton.

This figure he was continually reshaping and realtering. The

figure stood upon the margin of the pool; and near by were two

stones overgrown with moss, and supporting a cross of old

worm-eaten wood, which commemorated what had been done there.

One day, toward autumn, as Manuel was sitting in this place, and

looking into the deep still water, a stranger came, and he wore a

fierce long sword that interfered deplorably with his walking.

"Now I wonder what it is you find in that dark pool to keep you

staring so?" the stranger asked, first of all.

"I do not very certainly know," replied Manuel "but mistily I

seem to see drowned there the loves and the desires and the

adventures I had when I wore another body than this. For the water

of Haranton, I must tell you, is not like the water of other

fountains, and curious dreams engender in this pool."

"I speak no ill against oneirologya, although broad noon is

hardly the best time for its practise," declared the snub-nosed

stranger. "But what is that thing?" he asked, pointing.

"It is the figure of a man, which I have modeled and re-modeled,

sir, but cannot seem to get exactly to my liking. So it is

necessary that I keep laboring at it until the figure is to my

thinking and my desire."

"But, Manuel, what need is there for you to model it at

all?"

"Because my mother, sir, was always very anxious for me to make

a figure in the world, and when she lay a-dying I promised her that

I would do so, and then she put a geas upon me to do it."

"Ah, to be sure! but are you certain it was this kind of figure

she meant?"

"Yes, for I have often heard her say that, when I grew up, she

wanted me to make myself a splendid and admirable young man in

every respect. So it is necessary that I make the figure of a young

man, for my mother was not of these parts, but a woman of Ath

Cliath, and so she put a geas upon me—"

"Yes, yes, you had mentioned this geas, and I am wondering what

sort of a something is this geas."

"It is what you might call a bond or an obligation, sir, only it

is of the particularly strong and unreasonable and affirmative and

secret sort which the Virbolg use."

The stranger now looked from the figure to Manuel, and the

stranger deliberated the question (which later was to puzzle so

many people) if any human being could be as simple as Manuel

appeared. Manuel at twenty was not yet the burly giant he became.

But already he was a gigantic and florid person, so tall that the

heads of few men reached to his shoulder; a person of handsome

exterior, high featured and blond, having a narrow small head, and

vivid light blue eyes, and the chest of a stallion; a person whose

left eyebrow had an odd oblique droop, so that the stupendous boy

at his simplest appeared to be winking the information that he was

in jest.

All in all, the stranger found this young swineherd ambiguous;

and there was another curious thing too which the stranger noticed

about Manuel.

"Is it on account of this geas," asked the stranger, "that a

great lock has been sheared away from your yellow hair?"

In an instant Manuel's face became dark and wary. "No," he said,

"that has nothing to do with my geas, and we must not talk about

that"

"Now you are a queer lad to be having such an obligation upon

your head, and to be having well-nigh half the hair cut away from

your head, and to be having inside your head such notions. And

while small harm has ever come from humoring one's mother, yet I

wonder at you, Manuel, that you should sit here sleeping in the

sunlight among your pigs, and be giving your young time to

improbable sculpture and stagnant water, when there is such a fine

adventure awaiting you, and when the Norns are foretelling such

high things about you as they spin the thread of your living."

"Hah, glory be to God, friend, but what is this adventure?"

"The adventure is that the Count of Arnaye's daughter yonder has

been carried off by a magician, and that the high Count Demetrios

offers much wealth and broad lands, and his daughter's hand in

marriage, too, to the lad that will fetch back this lovely

girl."

"I have heard talk of this in the kitchen of Arnaye, where I

sometimes sell them a pig. But what are such matters to a

swineherd?"

"My lad, you are to-day a swineherd drowsing in the sun, as

yesterday you were a baby squalling in the cradle, but to-morrow

you will be neither of these if there by any truth whatever in the

talking of the Norns as they gossip at the foot of their ash-tree

beside the door of the Sylan's House."

Manuel appeared to accept the inevitable. He bowed his brightly

colored high head, saying gravely: "All honor be to Urdhr and

Verdandi and Skuld! If I am decreed to be the champion that is to

rescue the Count of Arnaye's daughter, it is ill arguing with the

Norns. Come, tell me now, how do you call this doomed magician, and

how does one get to him to sever his wicked head from his foul

body?"

"Men speak of him as Miramon Lluagor, lord of the nine kinds of

sleep and prince of the seven madnesses. He lives in mythic

splendor at the top of the gray mountain called Vraidex, where he

contrives all manner of illusions, and, in particular, designs the

dreams of men."

"Yes, in the kitchen of Arnaye, also, such was the report

concerning this Miramon: and not a person in the kitchen denied

that this Miramon is an ugly customer."

"He is the most subtle of magicians. None can withstand him, and

nobody can pass the terrible serpentine designs which Miramon has

set to guard the gray scarps of Vraidex, unless one carries the

more terrible sword Flamberge, which I have here in its blue

scabbard."

"Why, then, it is you who must rescue the Count's daughter."

"No, that would not do at all: for there is in the life of a

champion too much of turmoil and of buffetings and murderings to

suit me, who am a peace-loving person. Besides, to the champion who

rescues the Lady Gisèle will be given her hand in marriage,

and as I have a wife, I know that to have two wives would lead to

twice too much dissension to suit me, who am a peace-loving person.

So I think it is you who had better take the sword and the

adventure."

"Well," Manuel said, "much wealth and broad lands and a lovely

wife are finer things to ward than a parcel of pigs."

So Manuel girded on the charmed scabbard, and with the charmed

sword he sadly demolished the clay figure he could not get quite

right. Then Manuel sheathed Flamberge, and Manuel cried farewell to

the pigs.

"I shall not ever return to you, my pigs, because, at worst, to

die valorously is better than to sleep out one's youth in the sun.

A man has but one life. It is his all. Therefore I now depart from

you, my pigs, to win me a fine wife and much wealth and leisure

wherein to discharge my geas. And when my geas is lifted I shall

not come back to you, my pigs, but I shall travel everywhither, and

into the last limits of earth, so that I may see the ends of this

world and may judge them while my life endures. For after that,

they say, I judge not, but am judged: and a man whose life has gone

out of him, my pigs, is not even good bacon."

"So much rhetoric for the pigs," says the stranger, "is well

enough, and likely to please them. But come, is there not some girl

or another to whom you should be saying good-bye with other things

than words?"

"No, at first I thought I would also bid farewell to Suskind,

who is sometimes friendly with me in the twilight wood, but upon

reflection it seems better not to. For Suskind would probably weep,

and exact promises of eternal fidelity, and otherwise dampen the

ardor with which I look toward to-morrow and the winning of the

wealthy Count of Arnaye's lovely daughter."

"Now, to be sure, you are a queer cool candid fellow, you young

Manuel, who will go far, whether for good or evil!"

"I do not know about good or evil. But I am Manuel, and I shall

follow after my own thinking and my own desires."

"And certainly it is no less queer you should be saying that:

for, as everybody knows, that used to be the favorite byword of

your namesake the famous Count Manuel who is so newly dead in

Poictesme yonder."

At that the young swineherd nodded, gravely. "I must accept the

omen, sir. For, as I interpret it, my great namesake has

courteously made way for me, in order that I may go far beyond

him."

Then Manuel cried farewell and thanks to the mild-mannered,

snub-nosed stranger, and Manuel left the miller's pigs to their own

devices by the pool of Haranton, and Manuel marched away in his

rags to meet a fate that was long talked about.

II

Niafer

The first thing of all that Manuel did, was to fill a knapsack

with simple and nutritious food, and then he went to the gray

mountain called Vraidex, upon the remote and cloud-wrapped summit

of which dread Miramon Lluagor dwelt, in a doubtful palace wherein

the lord of the nine sleeps contrived illusions and designed the

dreams of men. When Manuel had passed under some very old

maple-trees, and was beginning the ascent, he found a smallish,

flat-faced, dark-haired boy going up before him.

"Hail, snip," says Manuel, "and whatever are you doing in this

perilous place?"

"Why, I am going," the dark-haired boy replied, "to find out how

the Lady Gisèle d'Arnaye is faring on the tall top of this

mountain."

"Oho, then we will undertake this adventure together, for that

is my errand too. And when the adventure is fulfilled, we will

fight together, and the survivor will have the wealth and broad

lands and the Count's daughter to sit on his knee. What do they

call you, friend?"

"I am called Niafer. But I believe that the Lady Gisèle

is already married, to Miramon Lluagor. At least, I sincerely hope

she is married to this great magician, for otherwise it would not

be respectable for her to be living with him at the top of this

gray mountain."

"Fluff and puff! what does that matter?" says Manuel. "There is

no law against a widow's remarrying forthwith: and widows are

quickly made by any champion about whom the wise Norns are already

talking. But I must not tell you about that, Niafer, because I do

not wish to appear boastful. So I must simply say to you, Niafer,

that I am called Manuel, and have no other title as yet, being not

yet even a baron."

"Come now," says Niafer, "but you are rather sure of yourself

for a young boy!"

"Why, of what may I be sure in this shifting world if not of

myself?"

"Our elders, Manuel, declare that such self-conceit is a fault,

and our elders, they say, are wiser than we."

"Our elders, Niafer, have long had the management of this

world's affairs, and you can see for yourself what they have made

of these affairs. What sort of a world is it, I ask you, in which

time peculates the gold from hair and the crimson from all lips,

and the north wind carries away the glow and glory and contentment

of October, and a driveling old magician steals a lovely girl? Why,

such maraudings are out of reason, and show plainly that our elders

have no notion how to manage things."

"Eh, Manuel, and will you re-model the world?"

"Who knows?" says Manuel, in the high pride of his youth. "At

all events, I do not mean to leave it unaltered."

Then Niafer, a more prosaic person, gave him a long look

compounded equally of admiration and pity, but Niafer did not

dispute the matter. Instead, these two pledged constant fealty

until they should have rescued Madame Gisèle.

"Then we will fight for her," says Manuel, again.

"First, Manuel, let me see her face, and then let me see her

state of mind, and afterward I will see about fighting you.

Meanwhile, this is a very tall mountain, and the climbing of it

will require all the breath which we are wasting here."

So the two began the ascent of Vraidex, by the winding road upon

which the dreams traveled when they were sent down to men by the

lord of the seven madnesses. All gray rock was the way at first.

But they soon reached the gnawed bones of those who had ascended

before them, scattered about a small plain that was overgrown with

ironweed: and through and over the tall purple blossoms came to

destroy the boys the Serpent of the East, a very dreadful design

with which Miramon afflicted the sleep of Lithuanians and Tartars.

The snake rode on a black horse, a black falcon perched on his

head, and a black hound followed him. The horse stumbled, the

falcon clamored, the hound howled.

Then said the snake: "My steed, why do you stumble? my hound,

why do you howl? and, my falcon, why do you clamor? For these three

doings foresay some ill to me."

"Oh, a great ill!" replies Manuel, with his charmed sword

already half out of the scabbard.

But Niafer cried: "An endless ill is foresaid by these doings.

For I have been to the Island of the Oaks: and under the twelfth

oak was a copper casket, and in the casket was a purple duck, and

in the duck was an egg: and in the egg, O Norka, was and is your

death."

"It is true that my death is in such an egg," said the Serpent

of the East, "but nobody will ever find that egg, and therefore I

am resistless and immortal."

"To the contrary, the egg, as you can perceive, is in my hand;

and when I break this egg you will die, and it is smaller worms

than you that will be thanking me for their supper this night."

The serpent looked at the poised egg, and he trembled and

writhed so that his black scales scattered everywhither

scintillations of reflected sunlight. He cried, "Give me the egg,

and I will permit you two to ascend unmolested, to a more terrible

destruction."

Niafer was not eager to do this, but Manuel thought it best, and

so at last Niafer consented to the bargain, for the sake of the

serpent's children. Then the two lads went upward, while the

serpent bandaged the eyes of his horse and of his hound, and hooded

his falcon, and crept gingerly away to hide the egg in an

unmentionable place.

"But how in the devil," says Manuel, "did you manage to come by

that invaluable egg?"

"It is a quite ordinary duck egg, Manuel. But the Serpent of the

East has no way of discovering the fact unless he breaks the egg:

and that is the one thing the serpent will never do, because he

thinks it is the magic egg which contains his death."

"Come, Niafer, you are not handsome to look at, but you are far

cleverer than I thought you!"

Now, as Manuel clapped Niafer on the shoulder, the forest beside

the roadway was agitated, and the underbrush crackled, and the tall

beech-trees crashed and snapped and tumbled helter-skelter. The

crust of the earth was thus broken through by the Serpent of the

North. Only the head and throat of this design of Miramon's was

lifted from the jumbled trees, for it was requisite of course that

the serpent's lower coils should never loose their grip upon the

foundations of Norroway. All of the design that showed was

overgrown with seaweed and barnacles.

"It is the will of Miramon Lluagor that I forthwith demolish you

both," says this serpent, yawning with a mouth like a fanged

cave.

Once more young Manuel had reached for his charmed sword

Flamberge, but it was Niafer who spoke.

"No, for before you can destroy me," says Niafer, "I shall have

cast this bridle over your head."

"What sort of bridle is that?" inquired the great snake

scornfully.

"And are those goggling flaming eyes not big enough and bright

enough to see that this is the soft bridle called Gleipnir, which

is made of the breath of fish and of the spittle of birds and of

the footfall of a cat?"

"Now, although certainly such a bridle was foretold," the snake

conceded, a little uneasily, "how can I make sure that you speak

the truth when you say this particular bridle is Gleipnir?"

"Why, in this way: I will cast the bridle over your head, and

then you will see for yourself that the old prophecy will be

fulfilled, and that all power and all life will go out of you, and

that the Northmen will dream no more."

"No, do you keep that thing away from me, you little fool! No,

no: we will not test your truthfulness in that way. Instead, do you

two continue your ascent, to a more terrible destruction, and to

face barbaric dooms coming from the West. And do you give me the

bridle to demolish in place of you. And then, if I live forever I

shall know that this is indeed Gleipnir, and that you have spoken

the truth."

So Niafer consented to this testing of his veracity, rather than

permit this snake to die, and the foundations of Norroway (in which

kingdom, Niafer confessed, he had an aunt then living) thus to be

dissolved by the loosening of the dying serpent's grip upon

Middlegarth. The bridle was yielded, and Niafer and Manuel went

upward.

Manuel asked, "Snip, was that in truth the bridle called

Gleipnir?"

"No, Manuel, it is an ordinary bridle. But this Serpent of the

North has no way of discovering this fact except by fitting the

bridle over his head: and this one thing the serpent will never do,

because he knows that then, if my bridle proved to be Gleipnir, all

power and all life would go out of him."

"O subtle, ugly little snip!" says Manuel: and again he patted

Niafer on the shoulder. Then Manuel spoke very highly in praise of

cleverness, and said that, for one, he had never objected to it in

its place.

III

Ascent of Vraidex

Now it was evening, and the two sought shelter in a queer

windmill by the roadside, finding there a small wrinkled old man in

a patched coat. He gave them lodgings for the night, and honest

bread and cheese, but for his own supper he took frogs out of his

bosom, and roasted these in the coals.

Then the two boys sat in the doorway, and watched that night's

dreams going down from Vraidex to their allotted work in the world

of visionary men, to whom these dreams were passing in the form of

incredible white vapors. Sitting thus, the lads fell to talking of

this and the other, and Manuel found that Niafer was a pagan of the

old faith: and this, said Manuel, was an excellent thing.

"For, when we have achieved our adventure," says Manuel, "and

must fight against each other for the Count's daughter, I shall

certainly kill you, dear Niafer. Now if you were a Christian, and

died thus unholily in trying to murder me, you would have to go

thereafter to the unquenchable flames of purgatory or to even

hotter flames: but among the pagans all that die valiantly in

battle go straight to the pagan paradise. Yes, yes, your abominable

religion is a great comfort to me."

"It is a comfort to me also, Manuel. But, as a Christian, you

ought not ever to have any kind words for heathenry."

"Ah, but," says Manuel, "while my mother Dorothy of the White

Arms was the most zealous sort of Christian, my father, you must

know, was not a communicant."

"Who was your father, Manuel?"

"No less a person than the Swimmer, Oriander, who is in turn the

son of Mimir."

"Ah, to be sure! and who is Mimir?"

"Well, Niafer, that is a thing not very generally known, but he

is famed for his wise head."

"And, Manuel, who, while we speak of it, is Oriander?"

Said Manuel:

"Oh, out of the void and the darkness that is peopled by Mimir's

brood, from the ultimate silent fastness of the desolate deep-sea

gloom, and the peace of that ageless gloom, blind Oriander came,

from Mimir, to be at war with the sea and to jeer at the sea's

desire. When tempests are seething and roaring from the Aesir's

inverted bowl all seamen have heard his shouting and the cry that

his mirth sends up: when the rim of the sea tilts up, and the

world's roof wavers down, his face gleams white where distraught

waves smite the Swimmer they may not tire. No eyes were allotted

this Swimmer, but in blindness, with ceaseless jeers, he battles

till time be done with, and the love-songs of earth be sung, and

the very last dirge be sung, and a baffled and outworn sea

begrudgingly own Oriander alone may mock at the might of its

ire."

"Truly, Manuel, that sounds like a parent to be proud of, and

not at all like a church-going parent, and of course his blindness

would account for that squint of yours. Yes, certainly it would. So

do you tell me about this blind Oriander, and how he came to meet

your mother Dorothy of the White Arms, as I suppose he did

somewhere or other."

"Oh, no," says Manuel, "for Oriander never leaves off swimming,

and so he must stay always in the water. So he never actually met

my mother, and she married Emmerick, who was my nominal father. But

such and such things happened."

Then Manuel told Niafer all about the circumstances of Manuel's

birth in a cave, and about the circumstances of Manuel's upbringing

in and near Rathgor and the two boys talked on and on, while the

unborn dreams went drifting by outside; and within the small

wrinkled old man sat listening with a very doubtful smile, and

saying never a word.

"And why is your hair cut so queerly, Manuel?"

"That, Niafer, we need not talk about, in part because it is not

going to be cut that way any longer, and in part because it is time

for bed."

The next morning Manuel and Niafer paid the ancient price which

their host required. They left him cobbling shoes, and, still

ascending, encountered no more bones, for nobody else had climbed

so high. They presently came to a bridge whereon were eight spears,

and the bridge was guarded by the Serpent of the West. This snake

was striped with blue and gold, and wore on his head a great cap of

humming-birds' feathers.

Manuel half drew his sword to attack this serpentine design,

with which Miramon Lluagor made sleeping terrible for the red

tribes that hunt and fish behind the Hesperides. But Manuel looked

at Niafer.

And Niafer displayed a drolly marked small turtle, saying,

"Maskanako, do you not recognize Tulapin, the turtle that never

lies?"

The serpent howled, as though a thousand dogs had been kicked

simultaneously, and the serpent fled.

"Why, snip, did he do that?" asked Manuel, smiling sleepily and

gravely, as for the third time he found that his charmed sword

Flamberge was unneeded.

"Truly, Manuel, nobody knows why this serpent dreads the turtle:

but our concern is less with the cause than with the effect.

Meanwhile, those eight spears are not to be touched on any

account."

"Is what you have a quite ordinary turtle?" asked Manuel,

meekly.

Niafer said: "Of course it is. Where would I be getting

extraordinary turtles?"

"I had not previously considered that problem," replied Manuel,

"but the question is certainly unanswerable."

They then sat down to lunch, and found the bread and cheese they

had purchased from the little old man that morning was turned to

lumps of silver and virgin gold in Manuel's knapsack. "This is very

disgusting," said Manuel, "and I do not wonder my back was near

breaking." He flung away the treasure, and they lunched frugally on

blackberries.

From among the entangled blackberry bushes came the glowing

Serpent of the South, who was the smallest and loveliest and most

poisonous of Miramon's designs. With this snake Niafer dealt

curiously. Niafer employed three articles in the transaction: two

of these things are not to be talked about, but the third was a

little figure carved in hazel-wood.

"Certainly you are very clever," said Manuel, when they had

passed this serpent. "Still, your employment of those first two

articles was unprecedented, and your disposal of the carved figure

absolutely embarrassed me."

"Before such danger as confronted us, Manuel, it does not pay to

be squeamish," replied Niafer, "and my exorcism was good

Dirgham."

And many other adventures and perils they encountered, such as

if all were told would make a long and most improbable history. But

they had clear favorable weather, and they won through each pinch,

by one or another fraud which Niafer evolved the instant that

gullery was needed. Manuel was loud in his praises of the

surprising cleverness of his flat-faced dark comrade, and protested

that hourly he loved Niafer more and more: and Manuel said too that

he was beginning to think more and more distastefully of the time

when Niafer and Manuel would have to fight for the Count of

Arnaye's daughter until one of them had killed the other.

Meanwhile the sword Flamberge stayed in its curious blue

scabbard.

IV

In the Doubtful Palace

So Manuel and Niafer came unhurt to the top of the gray mountain

called Vraidex, and to the doubtful palace of Miramon Lluagor.

Gongs, slowly struck, were sounding as if in languid dispute among

themselves, when the two lads came across a small level plain where

grass was interspersed with white clover. Here and there stood

wicked looking dwarf trees with violet and yellow foliage. The

doubtful palace before the circumspectly advancing boys appeared to

be constructed of black and gold lacquer, and it was decorated with

the figures of butterflies and tortoises and swans.

This day being a Thursday, Manuel and Niafer entered

unchallenged through gates of horn and ivory; and came into a red

corridor in which five gray beasts, like large hairless cats, were

casting dice. These animals grinned, and licked their lips, as the

boys passed deeper into the doubtful palace.

In the centre of the palace Miramon had set like a tower one of

the tusks of Behemoth: the tusk was hollowed out into five large

rooms, and in the inmost room, under a canopy with green tassels,

they found the magician.

"Come forth, and die now, Miramon Lluagor!" shouts Manuel,

brandishing his sword, for which, at last, employment was promised

here.

The magician drew closer about him his old threadbare

dressing-gown, and he desisted from his enchantments, and he put

aside a small unfinished design, which scuttled into the fireplace,

whimpering. And Manuel perceived that the dreadful prince of the

seven madnesses had the appearance of the mild-mannered stranger

who had given Manuel the charmed sword.

"Ah, yes, it was good of you to come so soon," says Miramon

Lluagor, rearing back his head, and narrowing his gentle and sombre

eyes, as the magician looked at them down the sides of what little

nose he had. "Yes, and your young friend, too, is very welcome. But

you boys must be quite worn out, after toiling up this mountain, so

do you sit down and have a cup of wine before I surrender my dear

wife."

Says Manuel, sternly, "But what is the meaning of all this?"

"The meaning and the upshot, clearly," replied the magician, "is

that, since you have the charmed sword Flamberge, and since the

wearer of Flamberge is irresistible, it would be nonsense for me to

oppose you."

"But, Miramon, it was you who gave me the sword!"

Miramon rubbed his droll little nose for a while, before

speaking. "And how else was I to get conquered? For, I must tell

you, Manuel, it is a law of the Léshy that a magician cannot

surrender his prey unless the magician be conquered. I must tell

you, too, that when I carried off Gisèle I acted, as I by

and by discovered, rather injudiciously."

"Now, by holy Paul and Pollux! I do not understand this at all,

Miramon."

"Why, Manuel, you must know she was a very charming girl, and in

appearance just the type that I had always fancied for a wife. But

perhaps it is not wise to be guided entirely by appearances. For I

find now that she has a strong will in her white bosom, and a

tireless tongue in her glittering head, and I do not equally admire

all four of these possessions."

"Still, Miramon, if only a few months back your love was so

great as to lead you into abducting her—"

The prince of the seven madnesses said gravely:

"Love, as I think, is an instant's fusing of shadow and

substance. They that aspire to possess love utterly, fall into

folly. This is forbidden: you cannot. The lover, beholding that

fusing move as a golden-hued goddess, accessible, kindly and

priceless, wooes and ill-fatedly wins all the substance. The

golden-hued shadow dims in the dawn of his married life, dulled

with content, and the shadow vanishes. So there remains, for the

puzzled husband's embracing, flesh which is fair and dear, no

doubt, yet is flesh such as his; and talking and talking and

talking; and kisses in all ways desirable. Love, of a sort, too

remains, but hardly the love that was yesterday's."

Now the unfinished design came out of the fireplace, and climbed

up Miramon's leg, still faintly whimpering. He looked at it

meditatively, then twisted off the creature's head and dropped the

fragments into his waste-basket.

Miramon sighed. He said:

"This is the cry of all husbands that now are or may be

hereafter,—'What has become of the girl that I married? and

how should I rightly deal with this woman whom somehow time has

involved in my doings? Love, of a sort, now I have for her, but not

the love that was yesterday's—'"

While Miramon spoke thus, the two lads were looking at each

other blankly: for they were young, and their understanding of this

matter was as yet withheld.

Then said Miramon:

"Yes, he is wiser that shelters his longing from any such

surfeit. Yes, he is wiser that knows the shadow makes lovely the

substance, wisely regarding the ways of that irresponsible shadow

which, if you grasp at it, flees, and, when you avoid it, will

follow, gilding all life with its glory, and keeping always one

woman young and most fair and most wise, and unwon; and keeping you

always never contented, but armed with a self-respect that no

husband manages quite to retain in the face of being contented. No,

for love is an instant's fusing of shadow and substance, fused for

that instant only, whereafter the lover may harvest pleasure from

either alone, but hardly from these two united."

"Well," Manuel conceded, "all this may be true; but I never

quite understood hexameters, and so I could not ever see the good

of talking in them."

"I always do that, Manuel, when I am deeply affected. It is, I

suppose, the poetry in my nature welling to the surface the moment

that inhibitions are removed, for when I think about the impending

severance from my dear wife I more or less lose control of

myself—You see, she takes an active interest in my work, and

that does not do with a creative artist in any line. Oh, dear me,

no, not for a moment!" says Miramon, forlornly.

"But how can that be?" Niafer asked him.

"As all persons know, I design the dreams of men. Now

Gisèle asserts that people have enough trouble in real life,

without having to go to sleep to look for it—"

"Certainly that is true," says Niafer.

"So she permits me only to design bright optimistic dreams and

edifying dreams and glad dreams. She says you must give tired

persons what they most need; and is emphatic about the importance

of everybody's sleeping in a wholesome atmosphere. So I have not

been permitted to design a fine nightmare or a creditable

terror—nothing morbid or blood-freezing, no sea-serpents or

krakens or hippogriffs, nor anything that gives me a really free

hand,—for months and months: and my art suffers. Then, as for

other dreams, of a more roguish nature—"

"What sort of dreams can you be talking about, I wonder,

Miramon?"

The magician described what he meant. "Such dreams also she has

quite forbidden," he added, with a sigh.

"I see," said Manuel: "and now I think of it, it is true that I

have not had a dream of that sort for quite a while."

"No man anywhere is allowed to have that sort of dream in these

degenerate nights, no man anywhere in the whole world. And here

again my art suffers, for my designs in this line were always

especially vivid and effective, and pleased the most rigid. Then,

too, Gisèle is always doing and telling me things for my own

good—In fine, my lads, my wife takes such a flattering

interest in all my concerns that the one way out for any

peace-loving magician was to contrive her rescue from my clutches,"

said Miramon, fretfully.

"It is difficult to explain to you, Manuel, just now, but after

you have been married to Gisèle for a while you will

comprehend without any explaining."

"Now, Miramon, I marvel to see a great magician controlled by a

woman who is in his power, and who can, after all, do nothing but

talk."

Miramon for some while considered Manuel, rather helplessly.

"Unmarried men do wonder about that," said Miramon. "At all events,

I will summon her, and you can explain how you have conquered me,

and then you can take her away and marry her yourself, and Heaven

help you!"

"But shall I explain that it was you who gave me the resistless

sword?"

"No, Manuel: no, you should be candid within more rational

limits. For you are now a famous champion, that has crowned with

victory a righteous cause for which many stalwart knights and

gallant gentlemen have made the supreme sacrifice, because they

knew that in the end the right must conquer. Your success thus

represents the working out of a great moral principle, and to

explain the practical minutiae of these august processes is not

always quite respectable. Besides, if Gisèle thought I

wished to get rid of her she would most certainly resort to

comments of which I prefer not to think."

But now into the room came the magician's wife,

Gisèle.

"She is, certainly, rather pretty," said Niafer, to Manuel.

Said Manuel, rapturously: "She is the finest and loveliest

creature that I have ever seen. Beholding her unequalled beauty, I

know that here are all the dreams of yesterday fulfilled. I

recollect, too, my songs of yesterday, which I was used to sing to

my pigs, about my love for a far princess who was 'white as a lily,

more red than roses, and resplendent as rubies of the Orient,' for

here I find my old songs to be applicable, if rather inadequate.

And by this shabby villain's failure to appreciate the unequalled

beauty of his victim I am amazed."

"As to that, I have my suspicions," Niafer replied. "And now she

is about to speak I believe she will justify these suspicions, for

Madame Gisèle is in no placid frame of mind."

"What is this nonsense," says the proud shining lady, to Miramon

Lluagor, "that I hear about your having been conquered?"

"Alas, my love, it is perfectly true. This champion has, in some

inexplicable way, come by the magic weapon Flamberge which is the

one weapon wherewith I can be conquered. So I have yielded to him,

and he is about, I think, to sever my head from my body."

The beautiful girl was indignant, because she had recognized

that, magician or no, there is small difference in husbands after

the first month or two; and with Miramon tolerably well trained,

she had no intention of changing him for another husband. Therefore

Gisèle inquired, "And what about me?" in a tone that

foreboded turmoil.

The magician rubbed his hands, uncomfortably. "My dear, I am of

course quite powerless before Flamberge. Inasmuch as your rescue

appears to have been effected in accordance with every rule in

these matters, and the victorious champion is resolute to requite

my evil-doing and to restore you to your grieving parents, I am

afraid there is nothing I can well do about it."

"Do you look me in the eye, Miramon Lluagor!" says the Lady

Gisèle. The dreadful prince of the seven madnesses obeyed

her, with a placating smile. "Yes, you have been up to something,"

she said, "And Heaven only knows what, though of course it does not

really matter."

Madame Gisèle then looked at Manuel "So you are the

champion that has come to rescue me!" she said, unhastily, as her

big sapphire eyes appraised him over her great fan of gaily colored

feathers, and as Manuel somehow began to fidget.

Gisèle looked last of all at Niafer. "I must say you have

been long enough in coming," observed Gisèle.

"It took me two days, madame, to find and catch a turtle,"

Niafer replied, "and that delayed me."

"Oh, you have always some tale or other, trust you for that, but

it is better late than never. Come, Niafer, and do you know

anything about this gawky, ragtag, yellow-haired young

champion?"

"Yes, madame, he formerly lived in attendance upon the miller's

pigs, down Rathgor way, and I have seen him hanging about the

kitchen at Arnaye."

Gisèle turned now toward the magician, with her thin gold

chains and the innumerable brilliancies of her jewels flashing no

more brightly than flashed the sapphire of her eyes. "There!" she

said, terribly: "and you were going to surrender me to a swineherd,

with half the hair chopped from his head, and with the shirt

sticking out of both his ragged elbows!"

"My dearest, irrespective of tonsorial tastes, and disregarding

all sartorial niceties, and swineherd or not, he holds the magic

sword Flamberge, before which all my powers are nothing."

"But that is easily settled. Have men no sense whatever! Boy, do

you give me that sword, before you hurt yourself fiddling with it,

and let us have an end of this nonsense."

Thus the proud lady spoke, and for a while the victorious

champion regarded her with very youthful looking, hurt eyes. But he

was not routed.

"Madame Gisèle," replied Manuel, "gawky and poorly clad

and young as I may be, so long as I retain this sword I am master

of you all and of the future too. Yielding it, I yield everything

my elders have taught me to prize, for my grave elders have taught

me that much wealth and broad lands and a lovely wife are finer

things to ward than a parcel of pigs. So, if I yield at all, I must

first bargain and get my price for yielding."

He turned now from Gisèle to Niafer. "Dear snip," said

Manuel, "you too must have your say in my bargaining, because from

the first it has been your cleverness that has saved us, and has

brought us two so high. For see, at last I have drawn Flamberge,

and I stand at last at the doubtful summit of Vraidex, and I am

master of the hour and of the future. I have but to sever the

wicked head of this doomed magician from his foul body, and that

will be the end of him—"

"No, no," says Miramon, soothingly, "I shall merely be turned

into something else, which perhaps we had better not discuss. But

it will not inconvenience me in the least, so do you not hold back

out of mistaken kindness to me, but instead do you smite, and take

your well-earned reward."

"Either way," submitted Manuel, "I have but to strike, and I

acquire much wealth and sleek farming-lands and a lovely wife, and

the swineherd becomes a great nobleman. But it is you, Niafer, who

have won all these things for me with your cleverness, and to me it

seems that these wonderful rewards are less wonderful than my dear

comrade."

"But you too are very wonderful," said Niafer, loyally.

Says Manuel, smiling sadly: "I am not so wonderful but that in

the hour of my triumph I am frightened by my own littleness. Look

you, Niafer, I had thought I would be changed when I had become a

famous champion, but for all that I stand posturing here with this

long sword, and am master of the hour and of the future, I remain

the boy that last Thursday was tending pigs. I was not afraid of

the terrors which beset me on my way to rescue the Count's

daughter, but of the Count's daughter herself I am horribly afraid.

Not for worlds would I be left alone with her. No, such fine and

terrific ladies are not for swineherds, and it is another sort of

wife that I desire."

"Whom then do you desire for a wife," says Niafer, "if not the

loveliest and the wealthiest lady in all Rathgor and Lower

Targamon?"

"Why, I desire the cleverest and dearest and most wonderful

creature in all the world," says Manuel,—"whom I recollect

seeing some six weeks ago when I was in the kitchen at Arnaye."

"Ah, ah! it might be arranged, then. But who is this marvelous

woman?"

Manuel said, "You are that woman, Niafer."

Niafer replied nothing, but Niafer smiled. Niafer raised one

shoulder a little, rubbing it against Manuel's broad chest, but

Niafer still kept silence. So the two young people regarded each

other for a while, not speaking, and to every appearance not

valuing Miramon Lluagor and his encompassing enchantments at a

straw's worth, nor valuing anything save each other.

"All things are changed for me," says Manuel, presently, in a

hushed voice, "and for the rest of time I live in a world wherein

Niafer differs from all other persons."

"My dearest," Niafer replied, "there is no sparkling queen nor

polished princess anywhere but the woman's heart in her would be

jumping with joy to have you looking at her twice, and I am only a

servant girl!"

"But certainly," said the rasping voice of Gisèle,

"Niafer is my suitably disguised heathen waiting-woman, to whom my

husband sent a dream some while ago, with instructions to join me

here, so that I might have somebody to look after my things. So,

Niafer, since you were fetched to wait on me, do you stop pawing at

that young pig-tender, and tell me what is this I hear about your

remarkable cleverness!"

Instead, it was Manuel who proudly told of the shrewd devices

through which Niafer had passed the serpents and the other terrors

of sleep. And the while that the tall boy was boasting, Miramon

Lluagor smiled, and Gisèle looked very hard at Niafer: for

Miramon and his wife both knew that the cleverness of Niafer was as

far to seek as her good looks, and that the dream which Miramon had

sent had carefully instructed Niafer as to these devices.

"Therefore, Madame Gisèle," says Manuel, in conclusion,

"I will give you Flamberge, and Miramon and Vraidex, and all the

rest of earth to boot, in exchange for the most wonderful and

clever woman in the world."

And with a flourish, Manuel handed over the charmed sword

Flamberge to the Count's lovely daughter, and he took the hand of

the swart, flat-faced servant girl.

"Come now," says Miramon, in a sad flurry, "this is an imposing

performance. I need not say it arouses in me the most delightful

sort of surprise and all other appropriate emotions. But as touches

your own interests, Manuel, do you think your behavior is quite

sensible?"

Tall Manuel looked down upon him with a sort of scornful pity.

"Yes, Miramon: for I am Manuel, and I follow after my own thinking

and my own desire. Of course it is very fine of me to be renouncing

so much wealth and power for the sake of my wonderful dear Niafer:

but she is worth the sacrifice, and, besides, she is witnessing all

this magnanimity, and cannot well fail to be impressed."

Niafer was of course reflecting: "This is very foolish and dear

of him, and I shall be compelled, in mere decency, to pretend to

corresponding lunacies for the first month or so of our marriage.

After that, I hope, we will settle down to some more reasonable way

of living."

Meanwhile she regarded Manuel fondly, and quite as though she

considered him to be displaying unusual intelligence.

But Gisèle and Miramon were looking at each other, and

wondering: "What can the long-legged boy see in this stupid and

plain-featured girl who is years older than he? or she in the young

swaggering ragged fool? And how much wiser and happier is our

marriage than, in any event, the average marriage!"

And Miramon, for one, was so deeply moved by the staggering

thought which holds together so many couples in the teeth of human

nature that he patted his wife's hand. Then he sighed. "Love has

conquered my designs," said Miramon, oracularly, "and the secret of

a contented marriage, after all, is to pay particular attention to

the wives of everybody else."

Gisèle exhorted him not to be a fool, but she spoke

without acerbity, and, speaking, she squeezed his hand. She

understood this potent magician better than she intended ever to

permit him to suspect.

Whereafter Miramon wiped the heavenly bodies from the firmament,

and set a miraculous rainbow there, and under its arch was enacted

for the swineherd and the servant girl such a betrothal masque of

fantasies and illusions as gave full scope to the art of Miramon,

and delighted everybody, but delighted Miramon in particular. The

dragon that guards hidden treasure made sport for them, the naiads

danced, and cherubim fluttered about singing very sweetly and

asking droll conundrums. Then they feasted, with unearthly

servitors to attend them, and did all else appropriate to an

affiancing of deities. And when these junketings were over, Manuel

said that, since it seemed he was not to be a wealthy nobleman

after all, he and Niafer must be getting, first to the nearest

priest's and then back to the pigs.

"I am not so sure that you can manage it," said Miramon, "for,

while the ascent of Vraidex is incommoded by serpents, the quitting

of Vraidex is very apt to be hindered by death and fate. For I must

tell you I have a rather arbitrary half-brother, who is one of

those dreadful Realists, without a scrap of aesthetic feeling, and

there is no controlling him."

"Well," Manuel considered, "one cannot live forever among

dreams, and death and fate must be encountered by all men. So we

can but try."

Now for a while the sombre eyes of Miramon Lluagor appraised

them. He, who was lord of the nine sleeps and prince of the seven

madnesses, now gave a little sigh; for he knew that these young

people were enviable and, in the outcome, were unimportant.

So Miramon said, "Then do you go your way, and if you do not

encounter the author and destroyer of us all it will be well for

you, and if you do encounter him that too will be well in that it

is his wish."

"I neither seek nor avoid him," Manuel replied. "I only know

that I must follow after my own thinking, and after a desire which

is not to be satisfied with dreams, even though they be"—the

boy appeared to search for a comparison, then, smiling,

said,—"as resplendent as rubies of the Orient."

Thereafter Manuel bid farewell to Miramon and Miramon's fine

wife, and Manuel descended from marvelous Vraidex with his

plain-featured Niafer, quite contentedly. For happiness went with

them, if for no great way.

V

The Eternal Ambuscade

Manuel and Niafer came down from Vraidex without hindrance.

There was no happier nor more devoted lover anywhere than young

Manuel.

"For we will be married out of hand, dear snip," he says, "and

you will help me to discharge my geas, and afterward we will travel

everywhither and into the last limits of earth, so that we may see

the ends of this world and may judge them."

"Perhaps we had better wait until next spring, when the roads

will be better, Manuel, but certainly we will be married out of

hand."

In earnest of this, Niafer permitted Manuel to kiss her again,

and young Manuel said, for the twenty-second time, "There is

nowhere any happiness like my happiness, nor any love like my

love."

Thus speaking, and thus disporting themselves, they came

leisurely to the base of the gray mountain and to the old

maple-trees, under which they found two persons waiting. One was a

tall man mounted on a white horse, and leading a riderless black

horse. His hat was pulled down about his head so that his face

could not be clearly seen.

Now the companion that was with him had the appearance of a

bare-headed youngster, with dark red hair, and his face too was

hidden as he sat by the roadway trimming his long finger-nails with

a small green-handled knife.

"Hail, friends," said Manuel, "and for whom are you waiting

here?"

"I wait for one to ride on this black horse of mine," replied

the mounted stranger. "It was decreed that the first person who

passed this way must be his rider, but you two come abreast. So do

you choose between you which one rides."

"Well, but it is a fine steed surely," Manuel said, "and a steed

fit for Charlemagne or Hector or any of the famous champions of the

old time."

"Each one of them has ridden upon this black horse of mine,"

replied the stranger.

Niafer said, "I am frightened." And above them a furtive wind

began to rustle in the torn, discolored maple-leaves.

"—For it is a fine steed and an old steed," the stranger

went on, "and a tireless steed that bears all away. It has the

fault, some say, that its riders do not return, but there is no

pleasing everybody."

"Friend," Manuel said, in a changed voice, "who are you, and

what is your name?"

"I am half-brother to Miramon Lluagor, lord of the nine sleeps,

but I am lord of another kind of sleeping; and as for my name, it

is the name that is in your thoughts and the name which most

troubles you, and the name which you think about most often."

There was silence. Manuel worked his lips foolishly. "I wish we

had not walked abreast," he said. "I wish we had remained among the

bright dreams."

"All persons voice some regret or another at meeting me. And it

does not ever matter."

"But if there were no choosing in the affair, I could make shift

to endure it, either way. Now one of us, you tell me, must depart

with you. If I say, 'Let Niafer be that one,' I must always recall

that saying with self-loathing."

"But I too say it!" Niafer was petting him and trembling.

"Besides," observed the rider of the white horse, "you have a

choice of sayings."

"The other saying," Manuel replied, "I cannot utter. Yet I wish

I were not forced to confess this. It sounds badly. At all events,

I love Niafer better than I love any other person, but I do not

value Niafer's life more highly than I value my own life, and it

would be nonsense to say so. No; my life is very necessary to me,

and there is a geas upon me to make a figure in this world before I

leave it."

"My dearest," says Niafer, "you have chosen wisely."

The veiled horseman said nothing at all. But he took off his

hat, and the beholders shuddered. The kinship to Miramon was

apparent, you could see the resemblance, but they had never seen in

Miramon Lluagor's face what they saw here.

Then Niafer bade farewell to Manuel with pitiable whispered

words. They kissed. For an instant Manuel stood motionless. He

queerly moved his mouth, as though it were stiff and he were trying

to make it more supple. Thereafter Manuel, very sick and desperate

looking, did what was requisite. So Niafer went away with

Grandfather Death, in Manuel's stead.

"My heart cracks in me now," says Manuel, forlornly considering

his hands, "but better she than I. Still, this is a poor beginning

in life, for yesterday great wealth and to-day great love was

within my reach, and now I have lost both."

"But you did not go the right way about to win success in

anything," says the remaining stranger.

And now this other stranger arose from the trimming of his long

fingernails; and you could see this was a tall, lean youngster

(though not so tall as Manuel, and nothing like so stalwart), with